Abstract

Objectives

To survey knowledge and attitudes about intrauterine contraception (IUC) among reproductive-aged women in the Saint Louis, Missouri, area.

Methods

We mailed an eight-page written survey to 12,500 randomly selected households in the St. Louis area, asking English-literate, reproductive-aged, adult women to respond. The survey asked about obstetric and contraceptive history, effectiveness of contraceptive methods, and appropriate candidates for, side effects of, and perceived risks of IUC. The results from 1,665 (13.3%) returned surveys were weighted for the analysis, which included descriptive statistics and polynomial logistic regression.

Results

Almost 8% of respondents were currently using or had previously used IUC and use was higher in women who reported discussing the method with their health care provider (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 13.4, 95% CI 6.5–27.8). Sixty-one percent of respondents underestimated the effectiveness of IUC and up to one-half of survey respondents were unable to correctly answer knowledge questions about IUC use and safety. An additional 11–36% of respondents indicated concern that IUC is associated with complications such as infection, infertility, and cancer. Current and past IUC users were more likely to be knowledgeable about IUC. Women who were currently using IUC were more likely to correctly estimate the effectiveness of IUC (adjusted OR 7.6, 95% CI 3.2–18.0).

Conclusion

Reproductive-aged women’s specific knowledge of the benefits and risks of IUC is limited. More educational interventions are needed to increase women’s knowledge about the effectiveness and benefits of IUC.

Introduction

Unintended pregnancy remains epidemic in the United States, encompassing nearly half of the six-million annual pregnancies and disproportionately affecting young, lower income and minority women.1 The National Survey for Family Growth (NSFG) reports the majority of women using reversible contraception choose oral contraceptive pills (OCP) and condoms.2 These methods have higher failure and discontinuation rates than long-acting reversible contraception, and require significant patient compliance.3 The NSFG reported an increase in the use of intrauterine contraception (IUC) from 2% in 2002 to 5.5% in the 2006-8 cycle. However, IUC use remains low when compared to use of less-effective reversible methods. 2

Multiple studies have shown that women value safety, effectiveness and ease of use in a birth control method,4, 5 characteristics inherent to IUC. Low utilization in the United States is likely due to a variety of factors, including patients’ misconceptions 4, 5 and providers’ reluctance to encourage use.6, 7 Prior studies of women’s knowledge about IUC indicate significant discrepancies between the respondents’ perception of IUC and actual IUC characteristics.5, 8 A large, previous study of women’s knowledge about IUC focused on women’s attitudes about the copper IUC only, as this research was performed before the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) was available in the United States.5 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the LNG-IUS in 2000.

In this study, we sought to improve our understanding of women’s knowledge, attitudes, specific beliefs, and misperceptions about IUC using a mail survey administered to a random sample of a large, diverse population of reproductive aged women in the Saint Louis area.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a postal survey of St. Louis area women’s knowledge of intrauterine contraception. From February to May 2008, we sent surveys to 12,500 randomly selected households in the St. Louis City and County using the United States Postal Service. We developed the survey instrument at our institution and piloted it among 700 women participating in a separate contraceptive study. This study was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Human Research Protections Office prior to administering the survey. Participant consent was implied by return of the completed survey. The postal survey was administered by the University of Wisconsin Survey Center.

Using the eight-page instrument, we obtained demographic information, including age, race/ethnicity, highest education level, type of insurance (private, Medicaid, Medicare or disability, or military), average income and receipt of government assistance such as welfare, unemployment and food stamps, obstetric history, and past and current use of contraceptive methods. An additional 27 questions focused on respondent’s knowledge of IUC, including respondent’s awareness of effectiveness, safety, and misperceptions about IUC, such as an association between IUC and infection or infertility. Questions about contraceptive knowledge and use did not differentiate between types of IUC, or assess timing or duration of use of a contraceptive method. Knowledge about the effectiveness of all contraceptive methods was assessed by asking about estimated failure rates with one year of typical use. Respondents were asked to choose the most appropriate category of the number of women out of 100 (or percentage) to become pregnant within one year of typical use (<1%, 1–5%, 6–10%, and greater then 10%) for each method. Typical use failure rates as described by Trussell et al3 were used to define “correct” answers.

We estimated that 1,200 completed surveys would provide a diverse sample of women in St. Louis City and County, with an estimated maximum margin of error plus or minus four percent around the percentages of contraceptive use. Potential participant households were randomly sampled from a list of United States Postal Service residential addresses purchased from Genesys Sampling Systems (Fort Washington, PA). The sample comprised 12,500 addresses, half from St. Louis City and half from St. Louis County. Twenty-four percent of households were estimated to have a resident female of reproductive age. Given an expected response rate of 40% from eligible households, a total of 12,500 area households were sampled to obtain our goal of 1,200 completed surveys. Over sampling of the city was performed in an attempt to increase response rates from underserved populations. Women eligible to participate were aged 18 – 45 years, literate in English, and willing to return the survey. One woman from each household was invited to participate.

The initial mailing contained an introductory letter, the survey instrument, a postage-paid return envelope, a $2 cash incentive, and a postcard for return by non-eligible households. A reminder postcard followed the first mailing. The second and third mailings were sent to non-responding addresses only, which excluded non-deliverable addresses and non-eligible households The second and third mailings contained a modified introductory letter, survey and envelope, and non-eligibility postcard. Return of the postcard indicating a household without an eligible participant prompted removal of this address from future mailings, and the household was documented as successfully screened. Each mailed survey contained a unique identifier so that subsequent mailings would not be sent to a household that had already responded. This identifier was not attached to any of the information returned in the survey. Returned surveys contained no identifying information about respondents.

The survey was weighted for non-response using weighting cell adjustments based on geographic regions within strata as well as mode/method of contact. Weights were trimmed prior to post-stratification. Weight trimming is a part of the weighting process to ensure that the impact of the sampling weights are not centered on one particular case and also to limit the variability of estimates that could have otherwise been inflated with untrimmed weights. We created a total of 36 post-stratification cells by crossing two strata (city versus county), three age groups, two race groups (black versus other race), and three levels of education. An iterative proportional fitting algorithm was applied to the weights in order to calibrate them to Saint Louis area control totals, which came from U.S. census data. The estimated number of women in the target population for the county was 179,009 and for the city, 69,628.

Descriptive analyses included demographic characteristics, past and current contraceptive use and satisfaction, and knowledge of intrauterine contraceptives. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression was used to assess likelihood of accurate knowledge of contraceptive effectiveness by previous method use, and to determine if the number of previously used contraceptive methods affected accuracy of knowledge of method effectiveness. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 10.0 (StataCorp, release 10.0, College Station TX).

Results

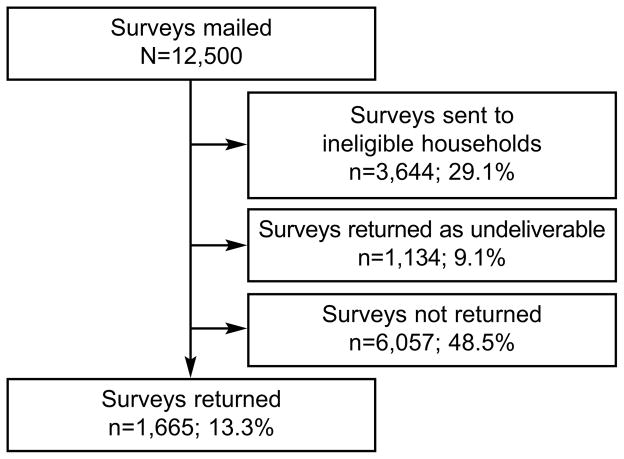

Figure 1 shows the outcomes of the 12,500 mailed surveys; 1,665 (13.3%) completed surveys were returned, 3644 (29.1%) surveys were mailed to an ineligible household confirmed by return of the non-eligibility postcard, and an additional 1134 surveys (9.1%) were returned as having an undeliverable address. This provided a 46.9% contact rate for the survey mailing. The percent of returned surveys in each mailing was 9.2%, 3.6%, and 3.0% for the first, second, and third mailings respectively. Reported IUC use and user satisfaction with IUC did not differ between mailing (p=0.99 for trend). Seventy-eight percent of the total surveys received were returned after the first mailing.

Figure 1.

Flowchart to show the outcome of the mailed surveys.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of respondents by experience with IUC. Overall, the mean age was 31.9 years, the majority had pursued education past high school, and 81.6% had some type of health insurance at the time of survey participation. A total of 129 (7.7%) respondents were currently using or had previously used IUC, and 78.7% of respondents had heard of an IUC. Past and current contraceptive use patterns of the respondents are presented in Table 2. Women who were current or previous users of IUC were slightly older, with a mean age of 32.4 years, and were more likely to be parous or to be receiving government assistance than respondents who had never used IUC. Only 28% of respondents reported that they had spoken with their health care provider about IUC. Women who reported discussing IUC with their healthcare provider were more likely to report current or past use (ORadj 13.4, 95% CI 6.5–27.8), after controlling for age, race, gravidity, education, insurance and receipt of government assistance. However, 49% of women who had spoken with a healthcare provider about IUC had not used the method. Fifty-four percent of past IUC users and 61% of current IUC users reported being satisfied with this method of birth control (Table 2). Among respondents who had used an intrauterine contraceptive and were not satisfied with the method, common reasons for dissatisfaction included change in menstrual bleeding (32% past users, 37% current users) and discomfort with device (19% previous users, 12% current users). Of prior IUC users who reported dissatisfaction with the method, 17% reported that it was due to concerns about an adverse outcome related to IUC effect such as infection or pelvic pain.

Table 1.

Demographic and reproductive characteristics of total respondents and current and past IUC users with weighted percentages

| Total | Current IUC Use | Past IUC Use | Never IUC Use | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted N | 1,665 | 78 | 51 | 1536 | |

|

| |||||

| Age (mean years) (SE) | 31.9(0.3) | 31.3(1.24) | 34.1(1.81) | 31.9(0.35) | 0.42 |

|

| |||||

| Weighted % | Weighted % | Weighted % | Weighted % | ||

|

| |||||

| Age | 0.15 | ||||

| 18–25 years | 28.6 | 21.6 | 17.1 | 29.5 | |

| 26–35 years | 32 | 50.2 | 34.8 | 30.8 | |

| >35 years | 39.4 | 28.2 | 48.1 | 39.6 | |

|

| |||||

| Race | 0.01 | ||||

| White | 56.9 | 55.1 | 41.8 | 57.8 | |

| Black | 34.4 | 40.7 | 56.9 | 32.9 | |

| Other | 8.7 | 4.3 | 1.3 | 9.3 | |

|

| |||||

| Hispanic | 0.94 | ||||

| Yes | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.5 | |

| No | 97.6 | 98.1 | 97.9 | 97.5 | |

|

| |||||

| Gravidity | <0.01 | ||||

| 0 | 30.6 | 5.1 | 8.6 | 33.3 | |

| 1–2 | 36.3 | 48.7 | 17 | 36.7 | |

| 3+ | 33 | 46.2 | 74.4 | 30 | |

|

| |||||

| Live births | <0.01 | ||||

| 0 | 40 | 23 | 11.7 | 42.5 | |

| 1–2 | 41.4 | 53.2 | 48.8 | 40.3 | |

| 3+ | 18.6 | 23.8 | 39.5 | 17.2 | |

|

| |||||

| Prior abortion | 18.4 | 25.9 | 27 | 17.5 | 0.17 |

|

| |||||

| Current insurance | |||||

| None | 18.4 | 8.5 | 20 | 18.9 | 0.23 |

|

| |||||

| Insurance type | <0.01 | ||||

| Private | 82.9 | 63.5 | 65 | 85.1 | |

| Government | 17.1 | 36.5 | 35 | 14.9 | |

|

| |||||

| Current goverment assistance | 19.2 | 49.4 | 25.7 | 17.1 | <0.01 |

|

| |||||

| Mean monthly household income per person (SE) | 1121 (34.2) | 840 (144.8) | 836 (92.9) | 1152(36.2) | <0.01 |

|

| |||||

| Education | <0.01 | ||||

| Some high school | 8.1 | 14.2 | 6 | 7.8 | |

| Completed high school | 22.4 | 21.4 | 52.7 | 20.8 | |

| Some college | 37.6 | 40.8 | 27.7 | 37.9 | |

| Completed college | 32 | 23.6 | 13.7 | 33.5 | |

= non-Hispanic

IUC = Intrauterine contraception

Table 2.

Reported contraceptive experience and satisfaction with the contraceptive methods, weighted percents (N=1665)

| Method | Unweighted N | Method Use Weighted % | Satisfied with Method Weighted %* |

|---|---|---|---|

| IUC | |||

| Current | 78 | 5.10% | 61.32% |

| Past | 51 | 4.80% | 53.78% |

|

| |||

| Implant | |||

| Current | 13 | 0.80% | 58.56% |

| Past | 47 | 3.80% | 40.45% |

|

| |||

| OCP | |||

| Current | 451 | 24.91% | 88.76% |

| Past | 1005 | 60.95% | 61.17% |

|

| |||

| Patch | |||

| Current | 21 | 2.09% | 62.61% |

| Past | 172 | 11.45% | 45.43% |

|

| |||

| Ring | |||

| Current | 51 | 3.23% | 83.57% |

| Past | 118 | 6.60% | 49.67% |

|

| |||

| DMPA | |||

| Current | 44 | 3.88% | 72.27% |

| Past | 288 | 21.63% | 46.31% |

|

| |||

| Condoms | |||

| Current | 470 | 29.98% | 72.97% |

| Past | 1053 | 60.83% | 52.78% |

satisfaction among those answered the satisfaction questions

Respondent’s knowledge about IUC was modest. Most respondents (79%) had heard of IUC, were aware IUC is used to prevent pregnancy (85%), and indicated that IUC does not prevent acquisition of a sexually transmitted infection (98%). The most commonly cited reasons to use IUC included prevention of pregnancy (59%), convenience (36%), and favorable side effect profile (28%). Additional questions focused on respondent’s specific knowledge about IUC safety, side effects and identification of appropriate candidates for IUC use. Respondents could indicate if they were unsure of the answer to each question. Never users were more likely than past and current IUC users to answer “don’t know” to each of the knowledge questions. Forty-nine percent of respondents agreed that IUC is safe, only 8% indicated this statement was incorrect, but an additional 43% were unsure. Common misperceptions about IUC included concerns that IUC increases the risk of developing an ectopic pregnancy, cancer, or a sexually transmitted infection (Table 3). Thirty-eight percent of respondents believed tampons cannot be used with IUC. At least 40% of women were uncertain who was an appropriate candidate for IUC; only 46% thought that nulliparous women could receive IUC and less than 30% of respondents believed that women with a new partner (27%), a history of an STI (28%), or adolescents (23%) would be candidates for IUC. Specific knowledge about the safety and expected side effects of intrauterine contraception was limited and was higher in current or past users of IUC (see Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Respondents’ knowledge of IUC side effects and complications, weighted percents

| IUC Use | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Past | Current | ||

| Unweighted N | 1536 | 51 | 78 | |

|

| ||||

| Weighted % | Weighted % | Weighted % | ||

|

| ||||

| IUC increases risk of STI | < 0.01 | |||

| Agree | 10.0 | 12.4 | 21.9 | |

| Disagree | 3.7 | 1.8 | 2.9 | |

| No effect | 49.8 | 66.2 | 62.6 | |

| Unsure | 36.5 | 19.6 | 12.6 | |

|

| ||||

| IUC increase risk of infertility | <0.01 | |||

| Agree | 30.7 | 33.6 | 20.9 | |

| Disagree | 7.8 | 19.9 | 18.6 | |

| No effect | 21.2 | 14.3 | 40.1 | |

| Unsure | 40.3 | 32.2 | 20.4 | |

|

| ||||

| IUC increases risk of ectopic pregnancy | < 0.01 | |||

| Agree | 24.0 | 35.2 | 31.8 | |

| Disagree | 4.4 | 13.9 | 5.2 | |

| No effect | 11.5 | 20.8 | 28.0 | |

| Unsure | 60.1 | 30.1 | 35.0 | |

|

| ||||

| IUC increases risk of cancer | <0.01 | |||

| Agree | 15.1 | 23.0 | 9.2 | |

| Disagree | 2.6 | 1.0 | 3.1 | |

| No effect | 21.4 | 32.6 | 50.0 | |

| Unsure | 60.8 | 43.3 | 37.7 | |

|

| ||||

| IUC increases pelvic pain | <0.01 | |||

| Agree | 33.8 | 42.6 | 43.0 | |

| Disagree | 2.1 | 1.4 | 2.1 | |

| No effect | 10.1 | 26.2 | 38.7 | |

| Unsure | 54.0 | 29.8 | 16.3 | |

IUC – intrauterine contraception; STI – sexually transmitted infection

Table 4.

Respondent’s estimates of contraceptive effectiveness, weighted percents

| Unweighted N | Estimation of Effectiveness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | Underestimate | Overestimate | |||

| IUC | 1611 | 39% | 61% | n/a | |

|

| |||||

| Implant | 1626 | 45% | 55% | n/a | |

|

| |||||

| OCP | 1635 | 16% | 13% | 71% | |

|

| |||||

| Patch | 1632 | 22% | 8% | 70% | |

|

| |||||

| Vaginal Ring | 1617 | 20% | 9% | 71% | |

|

| |||||

| DMPA | 1626 | 39% | 18% | 44% | |

|

| |||||

| Condoms | 1631 | 37% | n/a | 64% | |

|

| |||||

| Sterilization | 1626 | 74% | 26% | n/a | |

IUC – intrauterine contraception; Implant – subdermal contraceptive implant; OCP – oral contraceptive pills; Patch – contraceptive patch; Ring – vaginal contraceptive ring; DMPA – depomedroxyprogesterone acetate contraceptive injection.

Overall, knowledge of contraceptive effectiveness was poor; 55–84% of respondents reported incorrect answers for the likelihood of pregnancy in one year with typical use of reversible methods of contraception. The majority of respondents (61%) underestimated the effectiveness of intrauterine contraception, and most overestimated the effectiveness of combined hormonal contraceptive methods and barrier contraception (Table 3). Current intrauterine contraception use was associated with increased knowledge about IUC effectiveness; after controlling for age, race, gravidity and history of abortion, current IUC users were more than 7 times more likely to accurately identify IUC effectiveness (OR7.6, 95% CI 3.2–18.0) when compared with those respondents who had not used IUC. Experience with other contraceptive methods such as condoms, oral contraceptive pills, the contraceptive patch, and DMPA did not improve knowledge about IUC effectiveness. However, current implant users and ever users of the contraceptive vaginal ring were more likely to accurately identify IUC effectiveness (OR 4.9, 95% CI 1.1–23.0 and OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.6–4.1 respectively).

Discussion

In this study we attempted to gain greater understanding of reproductive-aged women’s knowledge about IUC. We found that most respondents are aware of IUC and more than half believe IUC to be safe. However, specific knowledge of IUC is limited, even among IUC users. Nevertheless, efforts to dispel myths and promote the safety and efficacy of IUC appear to be having a positive impact on IUC use. In the 1980’s, the combination of concerns about the Dalkon Shield 9 and research studies reporting an increase in the risks of infertility and infection 10 caused a reduction in the use of IUC in the United States from almost 10% of reproductive-aged women11 to less than 1%.2 Subsequent studies have disproved the association between IUC and infection and infertility.12, 13 The most recent NSFG data shows that 5.5% of reproductive-aged women using reversible contraception chose IUC.2 Attitudes about IUC safety are also shifting to reflect greater favorability; a 1996 study by Forrest reported only 21% of respondents believed IUC to be safe, while our findings show 49% of respondents believed IUC to be safe and only 8% thought IUC was not safe.5 In addition, our study revealed at least half of respondents did not believe IUC increase risk of an STI, and only one-third felt an IUC increases the risk of infertility.

Our findings and the existing literature indicate a need for further education of both providers and patients. Obstetrician-gynecologists are reluctant to place IUC in young, nulliparous, unmarried women6, 7, 14 despite current recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.15–17 The persistent deficits in provider knowledge impacts patient counseling and subsequent provision of IUC, however younger healthcare providers and those with greater experience with IUC placement during residency training are more likely to insert IUC once in practice.7 Additionally, lack of knowledge about IUC may contribute to low utilization of this method by patients. Whitaker et al evaluated the effect of a brief educational video on adolescent women’s knowledge of and attitude towards IUC, and found improved attitude towards IUC after this intervention.18 Additionally, a recent study from Secura et al showed that among women entering a prospective cohort study on contraception, those who are provided with education about IUC and implants and provided with no-cost contraception, are more likely to choose IUC and implants.19

Our study offers a contemporary evaluation of reproductive-aged women’s knowledge about IUC, including specific beliefs and misperceptions regarding safety and side effects, and provides potential avenues for targeted education. Our findings reveal need for improvement in knowledge for all women, regardless of contraceptive history. Strengths of this study include a random sampling strategy and a large, diverse sample of reproductive-aged women. Potential limitations of the study include the collection of self-reported data, which is subject to recall and social desirability bias. Only 18% of respondents reported a history of abortion, which is lower than expected given national estimates, suggesting participants may have been unwilling to divulge certain information. However, the 5.1% of respondents who reported current IUC use is similar to 5.5% reported from the most recent NSFG data, leading us to believe underreporting of IUC use is unlikely in this study. We did not assess timing or duration of contraceptive method use, or differentiate between types of IUC, which may affect reported satisfaction or side effects. There is also the possibility of a response bias, as women who had used IUC may have been more likely to complete the survey. This could potentially result in an overestimation of knowledge about IUC, which would strengthen our findings. Response bias may also account for the low satisfaction rates noted for past and current IUC users, as dissatisfied users may have been more likely to respond. As we only surveyed a single geographic region, our results may not be generalizable to other areas in the United States. However, given the diversity of our study population, we believe the results are likely generalizable to other urban, racially diverse areas.

Our data indicates that women’s attitudes towards IUC have improved in comparison to prior studies. However, persistent efforts to improve both provider and patient education are strongly needed. Educational interventions should include all reproductive-aged women, regardless of past contraceptive experience.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by: an anonymous foundation; a Midcareer Investigator Award in Women’s Health Research (K24 HD01298); Clinical and Translational Science Awards (UL1RR024992); award number K12HD001459 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD); and award Numbers KL2RR024994 and K3054628 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NICHD, NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented as a poster at the 2009 Reproductive Health Meeting in Los Angeles, CA., September 30-October 3, 2009.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–6. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008: data from the National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 2010;29:1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trussell J. Estimates of contraceptive failure from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception. 2008;78:85. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanwood NL, Bradley KA. Young pregnant women’s knowledge of modern intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1417–22. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000245447.56585.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forrest JD. U.S. women’s perceptions of and attitudes about the IUD. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51:S30–4. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199612000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanwood NL, Garrett JM, Konrad TR. Obstetrician-gynecologists and the intrauterine device: a survey of attitudes and practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:275–80. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madden T, Allsworth JE, Hladky KJ, Secura GM, Peipert JF. Intrauterine contraception in Saint Louis: a survey of obstetrician and gynecologists’ knowledge and attitudes. Contraception. 81:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schrager S, Hoffmann S. Women’s knowledge of commonly used contraceptive methods. WMJ. 2008;107:327–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivin I. Another look at the Dalkon Shield: meta-analysis underscores its problems. Contraception. 1993;48:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(93)90060-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cramer DW, Schiff I, Schoenbaum SC, et al. Tubal infertility and the intrauterine device. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:941–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198504113121502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darney PD. Time to pardon the IUD? N Engl J Med. 2001;345:608–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108233450810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kronmal RA, Whitney CW, Mumford SD. The intrauterine device and pelvic inflammatory disease: the Women’s Health Study reanalyzed. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:109–22. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90259-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubacher D, Lara-Ricalde R, Taylor DJ, Guerra-Infante F, Guzman-Rodriguez R. Use of copper intrauterine devices and the risk of tubal infertility among nulligravid women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:561–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espey E, Ogburn T, Espey D, Etsitty V. IUD-related knowledge, attitudes and practices among Navajo Area Indian Health Service providers. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35:169–73. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.169.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 392, December 2007. Intrauterine device and adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1493–5. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000291575.93944.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 59, January 2005. Intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:223–32. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200501000-00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farr S, Folger SG, Paulen M, et al. MMWR Recomm Rep. 4. Vol. 59. U S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010: adapted from the World Health Organization Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use; pp. 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitaker AK, Terplan M, Gold MA, Johnson LM, Creinin MD, Harwood B. Effect of a brief educational intervention on the attitudes of young women toward the intrauterine device. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;23:116–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:115, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]