Abstract

Identification and quantification of analytes in complex solution-state mixtures are critical procedures in many areas of Chemistry, Biology, and molecular Medicine. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a unique tool for this purpose providing a wealth of atomic-detail information without requiring extensive fractionation of the samples. We present three new multidimensional-NMR based approaches that are geared toward the analysis of mixtures with high complexity at natural 13C abundance, including ones encountered in metabolomics. Common to all three approaches is the concept of the extraction of 1D consensus spectral traces or 2D consensus planes followed by clustering, which significantly improves the capability to identify mixture components that are affected by strong spectral overlap. The methods are demonstrated for covariance 1H-1H TOCSY and 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectra and triple-rank correlation spectra constructed from pairs of 13C-1H HSQC and 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectra. All methods are first demonstrated for an 8 compound metabolite model mixture before being applied to an extract from E. coli cell lysate.

1. Introduction

Analysis of complex mixtures plays an important role in many areas of Chemistry, Biology, and molecular Medicine. Studies of natural and synthetic products, food and fuel analysis, chemical characterization of environmental samples, monitoring of reaction kinetics and many biochemical studies, including metabolomics and metabonomics, focus on the identification of individual compounds in complex mixtures.1–4 NMR offers a broad range of tools for this task. In some procedures 1D and 2D NMR spectra of multiple samples are analyzed at a time to identify spin systems by statistical correlation and difference mapping,5–8 while others study single samples and identify individual compounds based on the characteristic translational diffusion constants or NMR relaxation rates of their peaks.9–11 Another strategy uses intramolecular magnetization transfer especially via scalar J-couplings to identify individual spin systems that can be assigned to the various mixture components. For example, J-correlations between protons that are separated by typically no more than three covalent bonds can be established from a 2D 1H-1H COSY spectrum.12 When combined with 13C-1H HSQC information they can serve de novo chemical structure characterization of molecules in complex mixtures.13 Alternatively, correlation information of individual spin systems can be obtained from frequency-selective 1D TOCSY14,15 or 2D TOCSY16 in combination with clustering methods, such as DemixC.17 A disadvantage of 1H-NMR based approaches is the common occurrence of relatively broad multiplets of 1H peaks due to the presence of homonuclear 1H-1H J-couplings, which lead to increased peak overlaps.

At natural 13C abundance, the heteronuclear J-coupling-based 13C-1H HSQC18 spectrum displays large chemical shift dispersion with very narrow lines along the proton-decoupled 13C-dimension ω1, which makes cross-peak overlap rare. These favorable properties stand out against the sensitivity loss compared to homonuclear spectra. A major downside of HSQC-type spectra compared to TOCSY and COSY is the lack of complete spin system information as each cross-peak is independent of all others. On the other hand, the HSQC spectra of individual analytes represent useful fingerprints providing the number of C-H spin pairs of the molecule together with the 13C and 1H chemical shifts, which report on the nature of the chemical groups they belong to. 2D HSQC spectroscopy has been applied recently to identify and quantify chemical components in complex mixtures.19–22

The merging of HSQC with TOCSY in the form of the 3D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY experiment23 combines many of the advantages of homo- and heteronuclear 2D NMR for unambiguous metabolite identification.24 However, besides its relatively low sensitivity, high resolution along the indirect 13C dimension requires protracted NMR measurement times. Recently, we introduced the triple-rank (3R) correlation method, which combines pairs of standard 2D FT spectra that share a common frequency dimension.25 A similar strategy has been proposed for proteins.26 For example, from high-resolution 2D 13C-1H HSQC and 2D 1H-1H TOCSY spectra, sharing the proton dimension, a triple-rank correlation spectrum can be constructed with ultrahigh spectral resolution along all dimensions. It spreads out 1D TOCSY traces of individual spin systems along the 13C dimension according to the chemical shifts of the 13C spins directly attached to the protons. While in the absence of spectral overlap the triple-rank spectrum is equivalent to the corresponding experimental 3D FT spectrum, the occurrence of cross-peak overlaps leads to false peaks. To minimize such effects, we developed a spectral filtering method, which identifies mismatches between the first and second moments of cross-peak profiles and thereby suppresses false correlations.25

In this work, we present new strategies for the deconvolution of mixtures from 2D and 3R NMR spectra, which are specifically geared toward application to highly complex mixtures exemplified here by an E. coli cell lysate. The first approach extends the application range of the DemixC method,17 which requires that each component in the mixture has at least one resonance that is not affected by overlap. Because for highly complex mixtures this requirement becomes increasingly stringent, we replace it here by a method that is based on the more tolerant requirement that each component has at least one TOCSY cross-peak that is resolved. Extraction of 1D TOCSY traces that correspond to individual spin systems is based on a consensus approach that compares for each covariance TOCSY cross-peak cross sections (traces) along ω1 and ω2 for common peaks followed by trace clustering. This approach is subsequently adopted to 13C-1H 2D HSQC-TOCSY spectra taking advantage of the high resolution attainable along the indirect 13C dimension. The 3rd approach introduced here applies triple-rank (3R) correlation spectroscopy by combining 2D 13C-1H HSQC with 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY to construct a 3R HSQC-TOCSY spectrum. The approach is used to extract pure 2D 13C-1H HSQC spectra of the individual mixture components using a 2D version of the consensus algorithm described in the following section.

2. Computational Methods

Consensus peak pattern inferencing and clustering

Deconvolution of a 2D 1H-1H TOCSY or a 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectrum, represented by a N1 × N2 matrices T, of a complex mixture is performed as follows. We first apply direct covariance processing to T,27,28 C = (TT · T)1/2 with regularization,29 in the case of TOCSY and indirect covariance processing,30 C = (T · TT)1/2, in the case of HSQC-TOCSY. Peak picking of the cross-peaks of matrix C yields a list (k,k′) where k and k′ denote the position of a certain cross-peak along the two frequency axes. Next, for each cross-peak entry (k,k′) the consensus trace q(kk′) is determined as follows: in the case of covariance TOCSY C, the kth row and k′th row are processed as

| (1a) |

whereas in the case of HSQC-TOCSY T

| (1b) |

where index j goes over all N2 columns. The complete set of consensus traces q(kk′) is subsequently subjected to clustering for the identification of those traces that represent 1D 1H spectra of individual spin systems. For this purpose, 1D 1H consensus traces of Eqs. (1a,b) are quantitatively compared to each other via the inner product

| (2) |

where the L2-norm of a consensus trace is given by

| (3) |

A similarity measure between pairs of traces is then given by 1 – using the agglomerative hierarchical cluster algorithm as implemented in the subroutine ‘linkage’ in the Matlab software package. The clustering result can be displayed as a dendrogram. We refer to this approach as Demixing by Consensus Deconvolution and Clustering or DeCoDeC.

Consensus plane inferencing and clustering of triple-rank correlation spectrum

A triple-rank spectrum R is constructed from a 2D 13C-1H HSQC spectrum, represented by the N1 × N2 matrix H, and a 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectrum, represented by the N1 × N2 matrix T, where N2 is the number of points along the direct 1H dimension and N1 is the number of points along the indirect 13C dimension25

| (4) |

R can be considered as a collection of 2D 13C-1H HSQC spectra (with indices k,i for their 13C and 1H dimensions, respectively) along the additional proton dimension j of the 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectrum. A detailed description of consensus plane extraction and clustering, referred to as 3R DeCoDeC, is provided in the Supporting Information.

3. Experimental Section

An extract from E. coli BL21(DE3) strain prepared as described in the Supporting Information. A model mixture was prepared in D2O solution with 8 components where carnitine, alanine, isoleucine, ornithine, arginine, lysine, and shikimate are 10 mM each and glutamate is 1 mM (to introduce a 10-fold dynamic range). 2D 1H-1H TOCSY, 2D 13C-1H HSQC, and 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY data sets were collected for both samples as described in the Supporting Information.

4. Results

The cell lysate results are discussed first, followed by the results of the model mixture. Due to space limitations the figures of the model mixture, which provide a detailed illustration of the methods introduced in this work, are given in the Supporting Information.

Analysis of E. Coli BL21(DE3) Cell Extract

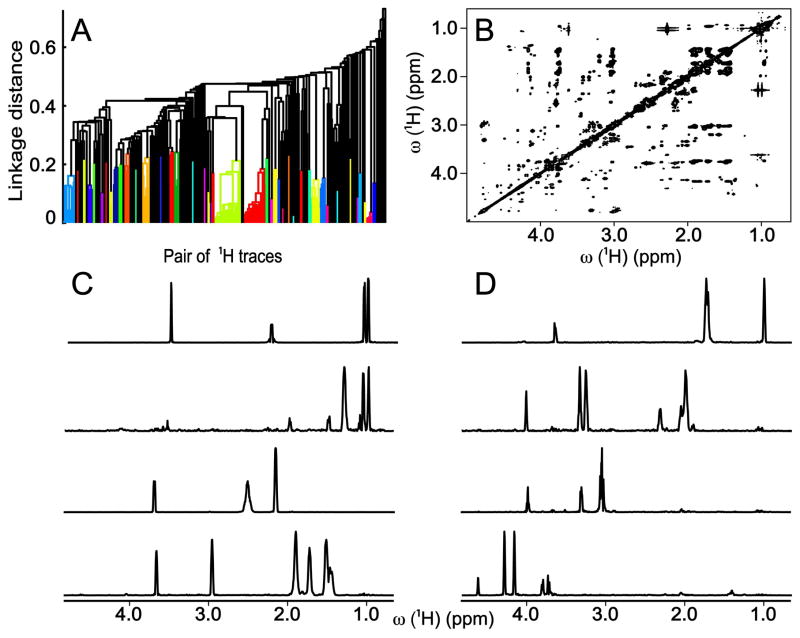

As a real-life application, we applied the DeCoDeC methods to an E. coli cell lysate eluted from a solid phase extraction cation-exchange column to partially remove saccharides and saccharide-containing compounds. These compounds would result in severe spectral congestion between 3 and 4 ppm in the 1H dimension and 70 and 80 ppm in the 13C dimension. Figure 1B displays the covariance processed 2D 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum of the cell lysate sample. Individual 1D spectra of valine, isoleucine, glutamine, lysine, leucine, proline, cystine, and ribose of adenosine are obtained by DeCoDeC as shown in Figure 1C,D.

Figure 1.

(A) Dendrogram of cluster analysis based on similarity of pairs of 1H traces calculated by 2D DeCoDeC approach applied to (B) covariance 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum of cell lysate. (C,D) Representative examples of NMR 1D spectra constructed by 2D DeCoDeC from 2D TOCSY of Panel B. From top to bottom: (C) valine, isoleucine, glutamine, lysine; (D) leucine, proline, cystine, ribose ring of adenosine.

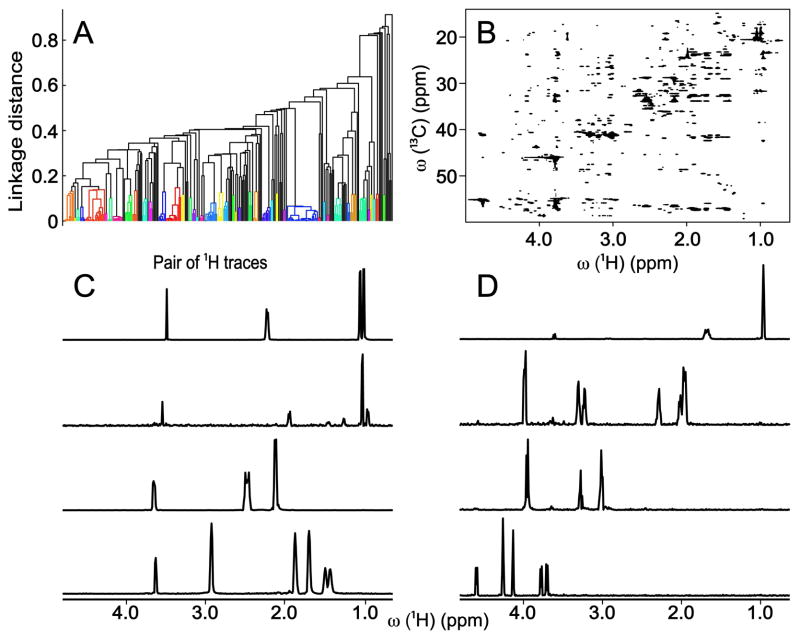

The deconvolution performance of DeCoDeC for the cell lysate based on the 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectrum can be assessed from Figure 2. Overall, there are no missing peaks in any of the spectra in Figure 1C,D and 2C,D, except for adenosine whose 1D 1H spectrum in the BMRB has two additional peaks, which are not obtained by DeCoDeC, because these peaks are part of the nucleic acid and not of the ribose ring of adenosine. Since there is no detectable magnetization transfer between these molecular parts during TOCSY mixing, the proton signals coming from ribose protons and nucleic acid protons cannot be seen in the same 1D 1H DeCoDeC trace. The ribose ring of adenosine shows one extra peak in the spectral regions of Figures 1 and 2 (for the full 1D 1H spectra of ribose ring obtained by DeCoDeC see Figure S-6B,D). For a detailed comparison, 1D 1H reference spectra taken from the BMRB of 8 compounds of the cell lysate are given in Figure S-5.

Figure 2.

(A) Dendrogram of cluster analysis based on similarity of the pairs of 1H traces calculated by 2D DeCoDeC approach applied to (B) 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectrum of cell lysate. (C,D) Representative examples of 1D NMR spectra constructed by 2D DeCoDeC from 2D HSQC-TOCSY of Panel B from top to bottom. From top to bottom: (C) valine, isoleucine, glutamine, lysine; (D) leucine, proline, cystine, ribose ring of adenosine.

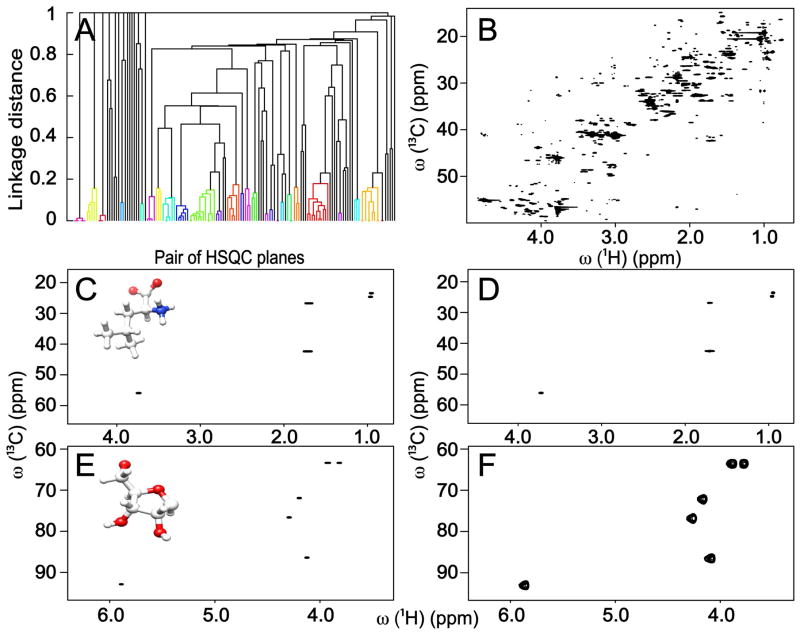

The result of the triple-rank approach for the cell lysate is illustrated in Figure 3. Representative HSQC spectra for the following compounds are taken from the BMRB31 or HMDB34 databases: cystine, valine, isoleucine, leucine, proline, glutamine, lysine, glutathione, cytosine, and 4 ribose rings corresponding to different nucleic acid forms. The 2D 1H-1H TOCSY16 spectrum is used to confirm the identified and unidentified compounds in the cell lysate. Leucine and the ribose ring of cytidine are depicted as examples in Figure 3C,E. Six HSQC planes, which could not be identified neither in the BMRB nor the HMDB database, were confirmed by 1H-1H TOCSY. The unidentified compounds are either not available in these databases or they belong to isolated spin systems of larger metabolites; therefore, HSQC spectra extracted by 3R DeCoDeC only reflect a portion of these molecules.

Figure 3.

(A) Dendrogram of cluster analysis based on similarity of pairs of HSQC planes from 3R spectrum constructed from a 2D 13C-1H HSQC and a 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectrum of cell lysate. (C) Comparison of 3R HSQC plane of leucine with (D) corresponding HSQC in the BMRB. (E) Comparison of 3R HSQC plane of ribose ring of cytidine with (F) corresponding HSQC spectrum in the BMRB.

Analysis of Model Mixture

Figure S-1 illustrates the performance of the DeCoDeC approach on the 8-compound model mixture based on a single covariance processed 2D 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum. The spectrum exhibits several regions with spectral congestions due to similar chemical structures of arginine, lysine, and ornithine giving rise to peak overlaps across the spectrum. In addition, alanine, isoleucine, and lysine have overlapping peaks around 1.3 ppm. Application of the DeCoDeC procedure results in remarkably clean, overlap free 1D spectra for each compound in this mixture. Carnitine and lysine are chosen here to illustrate the DeCoDeC algorithm. Cross-peak picking generates a peak list with pairs of indices that define the chemical shifts of resonances that potentially belong to the same compound. Two cross-peaks (a,b) and (c,d) are chosen with the corresponding traces a,b,c,d indicated by arrows in Panel S-1B. In the case of carnitine, the 2 traces c and d are not affected by overlaps and DeCoDeC produces their consensus trace (c,d) as a clean 1D spectrum of carnitine (for comparison, a 1D reference spectrum of carnitine taken from the BMRB31 is displayed in Figure S-4). Lysine is more challenging, since trace (a) overlaps with alanine and isoleucine and trace (b) overlaps with ornithine and arginine. Nonetheless, DeCoDeC produces a consensus 1D trace (a,b) with peaks that solely belong to lysine as shown in Figure S-1C. The dendrogram of Figure S-1A shows that partitioning of the consensus traces into clusters is robust allowing the selection of representative cluster traces as 1D spectra. For comparison, the DemixC method applied to the same TOCSY spectrum via COLMAR32,33 correctly captures the 1D spectra of 6 out of 8 compounds (see Figure S-7).

DeCoDeC can be applied in a similar manner for the analysis of the 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectrum of the model mixture (Figure S-2). Because the spectrum exhibits sharp peaks and a large chemical shift dispersion along the 13C dimension, DeCoDeC performs with 100% accuracy with the consensus traces having even slightly better appearance (Figure S-2C,D) than in the case of 2D 1H-1H TOCSY.

Overall, there are no missing peaks in any of the DeCoDeC spectra in Figures S-1C,D and S-2C,D except for the (CH3)3 peak of carnitine (because it is not J-coupled to the rest of the molecule and hence does not exchange magnetization with other resonances during TOCSY mixing). Shikimate has one extra peak outside the spectral regions shown in Figures S-1 and S-2 (for the full 1D 1H spectra of shikimate obtained by DeCoDeC see Figures S-6A,C).

Application of 3R DeCoDeC to the same model mixture combines the 2D 13C-1H HSQC spectrum of Figure S-3B with the 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectrum of Figure S-2B to extract 2D 13C-1H HSQC spectra of the individual compounds using Eq. (4). The representative HSQC spectrum for every compound is validated with the corresponding HSQC spectrum in the BMRB.31 For the model mixture, the HSQC spectra of all 8 components are successfully extracted, which is illustrated for lysine and isoleucine in Figure S-3.

The dendrograms in Figures S-1A, S-2A and S-3A illustrate the clustering results for the model mixture by applying DeCoDeC to the 2D 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum, DeCoDeC to the 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectrum, and 3R DeCoDeC to the 3R spectrum constructed from the 2D 13C-1H HSQC and 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectral pair, respectively. In Figure S-1A, the locations of selected lysine (a,b) and carnitine (c,d) traces are labeled by arrows illustrating the DeCoDeC approach. The dendrogram is useful for visual inspection and validation of the clustering result and for selecting or verifying a suitable representative trace for each cluster.

5. Discussion

The automated analysis of complex mixtures by NMR has made significant progress over the recent past. Existing deconvolution approaches based on J-coupling mediated magnetization transfer can be divided into two groups. The first group focuses on matching the cross-peaks of a HSQC-type spectrum of the mixture with the cross-peaks of individual compounds compiled in a database.19,35,36 Optionally, the candidate compounds obtained from the database can be confirmed by using higher-dimensional experiments, such as 3D HCCH-COSY37 by taking advantage of the higher resolution along the additional 13C dimension and the 1H-1H connectivity information. The disadvantage of this approach is that the compounds that can be extracted are limited to the ones stored in the databases preventing the discovery of novel compounds. The second group of methods directly focuses on the connectivity information in 2D experiments, often from 1H-1H TOCSY.17 Since chemical shift dispersion in the proton dimension may not be sufficient for the analysis of very complex mixtures, depending upon the cross-peak density in the TOCSY spectrum, TOCSY has been substituted by the 2D HSQC-TOCSY38 experiment to make use of the chemical shift dispersion along the 13C dimension with narrow 13C line widths, which tends to be less prone to overlap. Both types of spectra are then subjected to automated analysis based on an algorithm that searches for the ‘clean’ 1D cross sections in 2D spectrum to represent 1D spectra of individual compounds. Depending on the NMR properties of the components, this strategy generally works well for mixtures of moderate complexity. However, in mixtures of higher complexity, such as a crude cell extract, the cross-peak overlap problem can become so severe that no single cross section can be found that represents a clean 1D trace. Instead of searching for one clean cross section, the DeCoDeC algorithms extracts common peak patterns from pairs of cross sections, which can have different overlaps in the proton dimension. The resulting consensus traces or planes are more likely to represent clean 1D or 2D spectra of individual components identified through subsequent clustering. It should be noted that there is no consensus trace for 1-spin systems. Therefore, information on such systems is not tracked. Consensus trace determination can be generalized to trace triplets or even larger numbers of traces. For example, in the case of trace triplets any 3-spin system will yield only a single consensus trace, which after clustering will show up as an ‘orphan’ trace in the dendrogram, while 1-spin and 2-spin systems will be lost.

Although more NMR-time consuming than the 2D methods, the 3R DeCoDeC approach introduced here directly generates HSQC spectra of individual compounds in mixtures, which has several advantages. First, an HSQC is more specific than a 1D trace as spectral information is spread out in multiple dimensions. This makes database querying of HSQC planes more accurate than querying of 1D spectral traces. At the same time, one retains the option to project the HSQC plane onto the proton or carbon dimension and apply a 1D query. Secondly, clustering of HSQC planes enhances the separation of the cluster centers, which helps visual inspection of the dendrogram for the extraction of a representative HSQC plane for every cluster.

HSQC planes reconstructed by the new method carry their original intensities from the input HSQC spectrum H, therefore they can be used for the quantification of compound concentrations. Moreover, it has been pointed out22 that the concentration measurement for an individual metabolite can be improved by averaging the intensities of multiple, non-overlapping cross-peaks assigned to that metabolite. Since HSQC is deficient in connectivity information across complete spin systems, it is not known which peaks can be averaged to accurately quantify concentration of an individual compound in a complex mixture. Since 3R produces individual HSQC planes for each compound, one can average the peaks in the same HSQC plane to measure its concentration more accurately.

High resolution along the indirect 13C dimension is critical for the performance of the 3R DeCoDeC method. Recently, non-uniform sampling schemes have been introduced to shorten the total acquisition time for 2D HSQC(-TOCSY) by reducing the number of increments along the indirect dimension while maintaining a high digital resolution.39 These methods can be used to shorten the total NMR measurement time, while keeping the spectral resolution sufficiently high. Finally, the 3R DeCoDeC method can be implemented for other pairs of 2D spectra, such as HMBC and HSQC, TOCSY and HSQC or even 2D HSQC-TOCSY and HMBC to obtain HMBC planes of individual compounds in complex mixtures.

6. Conclusion

New 2D and 3R NMR strategies have been described for the analysis of complex chemical mixtures to obtain information about the components in a reliable, efficient, and automatable fashion. The 2D DeCoDeC approach permits the determination of 1D 1H spectra of individual components while the 3R DeCoDeC method extracts 2D 13C-1H HSQCs of individual components, which serve as useful fingerprints for database queries and as entry points to chemical structure determination. The 2D TOCSY, 2D HSQC-TOCSY, and 3R HSQC-TOCSY spectra require increasing amounts of measurement times, but they provide increasingly good deconvolution performance when applied to mixtures of higher complexity. Together these new tools open up the prospect to enable routine yet accurate analysis of an increasingly complex and diverse range of molecular solutions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lei Bruschweiler-Li for expert help in the preparation of the NMR samples. Drs. Fengli Zhang and Lei Bruschweiler-Li are acknowledged for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 GM066041).

Supporting Information Available: 3 figures illustrating application of DeCoDeC to covariance 1H-1H TOCSY and 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY, and 3R DeCoDeC to the triple-rank spectrum constructed from the 2D 13C-1H HSQC and 2D 13C-1H HSQC-TOCSY spectra of the model mixture. 2 figures with 1D reference 1H spectra from the BMRB for compounds mentioned in the main text. Figure of the full 1H 1D spectra of shikimate and ribose ring of adenosine obtained by 2D DeCoDeC. Two figures with DemixC results of the model mixture and the cell lysate covariance 2D 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum. Figure with 1D 1H NMR spectrum of cell lysate. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Nicholson JK, Wilson ID. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2003;2:668–676. doi: 10.1038/nrd1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Greef J, Stroobant P, van der Heijden R. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang F, Dossey AT, Zachariah C, Edison AS, Brüschweiler R. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7748–7752. doi: 10.1021/ac0711586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forseth RR, Schroeder FC. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cloarec O, Dumas ME, Craig A, Barton RH, Trygg J, Hudson J, Blancher C, Gauguier D, Lindon JC, Holmes E, Nicholson J. Anal Chem. 2005;77:1282–1289. doi: 10.1021/ac048630x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeder FC, Gibson DM, Churchill ACL, Sojikul P, Wursthorn EJ, Krasnoff SB, Clardy J. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:901–904. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pungaliya C, Srinivasan J, Fox BW, Malik RU, Ludewig AH, Sternberg PW, Schroeder FC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7708–7713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811918106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinette SL, Ajredini R, Rasheed H, Zeinomar A, Schroeder FC, Dossey AT, Edison AS. Anal Chem. 2011;83:1649–1657. doi: 10.1021/ac102724x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson CS. Progress in Nucl Mag Reson Spectrosc. 1999;34:203–256. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nilsson M, Botana A, Morris GA. Anal Chem. 2009;81:8119–8125. doi: 10.1021/ac901321w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novoa-Carballal R, Fernandez-Megia E, Jimenez C, Riguera R. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28:78–98. doi: 10.1039/c005320c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rance M, Sorensen OW, Bodenhausen G, Wagner G, Ernst RR, Wuthrich K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;117:479–485. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang F, Bruschweiler-Li L, Brüschweiler R. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:16922–16927. doi: 10.1021/ja106781r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandusky P, Raftery D. Anal Chem. 2005;77:2455–2463. doi: 10.1021/ac0484979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandusky P, Raftery D. Anal Chem. 2005;77:7717–7723. doi: 10.1021/ac0510890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braunschweiler L, Ernst RR. J Magn Reson. 1983;53:521–528. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang FL, Brüschweiler R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2639–2642. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodenhausen G, Ruben DG. Chem Phys Lett. 1980;69:185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis IA, Schommer SC, Hodis B, Robb KA, Tonelli M, Westler WM, Sussman MR, Markley JL. Anal Chem. 2007;79:9385–9390. doi: 10.1021/ac071583z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rai RK, Tripathi P, Sinha N. Anal Chem. 2009;81:10232–10238. doi: 10.1021/ac902405z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gowda GA, Tayyari F, Ye T, Suryani Y, Wei S, Shanaiah N, Raftery D. Anal Chem. 2010;82:8983–8990. doi: 10.1021/ac101938w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu K, Westler WM, Markley JL. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1662–1665. doi: 10.1021/ja1095304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bax A, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. J Magn Reson. 1990;88:425–431. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pontoizeau C, Herrmann T, Toulhoat P, Elena-Herrmann B, Emsley L. Magn Reson Chem. 2010;48:727–733. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bingol K, Salinas RK, Brüschweiler R. J Phys Chem Lett. 2010;1:1086–1089. doi: 10.1021/jz100264g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen K, Delaglio F, Tjandra N. J Magn Reson. 2010;203:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brüschweiler R, Zhang FL. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:5253–5260. doi: 10.1063/1.1647054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trbovic N, Smirnov S, Zhang F, Brüschweiler R. J Magn Reson. 2004;171:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen YB, Zhang FL, Snyder D, Gan ZH, Bruschweiler-Li L, Brüschweiler R. J Biomol NMR. 2007;38:73–77. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang F, Brüschweiler R. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13180–13181. doi: 10.1021/ja047241h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulrich EL, Akutsu H, Doreleijers JF, Harano Y, Ioannidis YE, Lin J, Livny M, Mading S, Maziuk D, Miller Z, Nakatani E, Schulte CF, Tolmie DE, Kent Wenger R, Yao H, Markley JL. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D402–408. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinette SL, Zhang F, Bruschweiler-Li L, Brüschweiler R. Anal Chem. 2008;80:3606–3611. doi: 10.1021/ac702530t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang F, Robinette SL, Bruschweiler-Li L, Brüschweiler R. Magn Reson Chem. 2009;47:S118–122. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wishart DS, Tzur D, Knox C, Eisner R, Guo AC, Young N, Cheng D, Jewell K, Arndt D, Sawhney S, Fung C, Nikolai L, Lewis M, Coutouly MA, Forsythe I, Tang P, Shrivastava S, Jeroncic K, Stothard P, Amegbey G, Block D, Hau DD, Wagner J, Miniaci J, Clements M, Gebremedhin M, Guo N, Zhang Y, Duggan GE, Macinnis GD, Weljie AM, Dowlatabadi R, Bamforth F, Clive D, Greiner R, Li L, Marrie T, Sykes BD, Vogel HJ, Querengesser L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D521–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui Q, Lewis IA, Hegeman AD, Anderson ME, Li J, Schulte CF, Westler WM, Eghbalnia HR, Sussman MR, Markley JL. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:162–164. doi: 10.1038/nbt0208-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chikayama E, Sekiyama Y, Okamoto M, Nakanishi Y, Tsuboi Y, Akiyama K, Saito K, Shinozaki K, Kikuchi J. Anal Chem. 2010;82:1653–1658. doi: 10.1021/ac9022023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sekiyama Y, Chikayama E, Kikuchi J. Anal Chem. 2011;83:719–726. doi: 10.1021/ac102097u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang F, Bruschweiler-Li L, Robinette SL, Brüschweiler R. Anal Chem. 2008;80:7549–7553. doi: 10.1021/ac801116u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hyberts SG, Heffron GJ, Tarragona NG, Solanky K, Edmonds KA, Luithardt H, Fejzo J, Chorev M, Aktas H, Colson K, Falchuk KH, Halperin JA, Wagner G. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5108–5116. doi: 10.1021/ja068541x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.