Abstract

To facilitate the study of interactions between proteins and chemicals, we have created STITCH, an aggregated database of interactions connecting over 300 000 chemicals and 2.6 million proteins from 1133 organisms. Compared to the previous version, the number of chemicals with interactions and the number of high-confidence interactions both increase 4-fold. The database can be accessed interactively through a web interface, displaying interactions in an integrated network view. It is also available for computational studies through downloadable files and an API. As an extension in the current version, we offer the option to switch between two levels of detail, namely whether stereoisomers of a given compound are shown as a merged entity or as separate entities. Separate display of stereoisomers is necessary, for example, for carbohydrates and chiral drugs. Combining the isomers increases the coverage, as interaction databases and publications found through text mining will often refer to compounds without specifying the stereoisomer. The database is accessible at http://stitch.embl.de/.

INTRODUCTION

The part of chemical space that has been charted is ever increasing, and a large fraction of the determined protein–chemical interactions are becoming available for public research. Most notably, the ChEMBL database with currently over 400 000 Ki, IC50 and EC50 values became available in 2010 (1). Nonetheless, the information on protein–chemical interactions is spread over a great variety of databases and the literature, making it difficult to get an overview of the known interactions of any given chemical of interest. To ameliorate this problem, we have developed STITCH (2,3), a combined repository of data that captures as much as possible of the publicly available knowledge on protein–chemical associations. STITCH (‘search tool for interacting chemicals’) allows for easy and intuitive interactive access, for large-scale analysis via download files, and for automated access on a small to medium scale through an API. STITCH has been used, for example, to study the conservation of protein–chemical interactions between yeast species (4) and to benchmark predicted drug–target interactions (5,6).

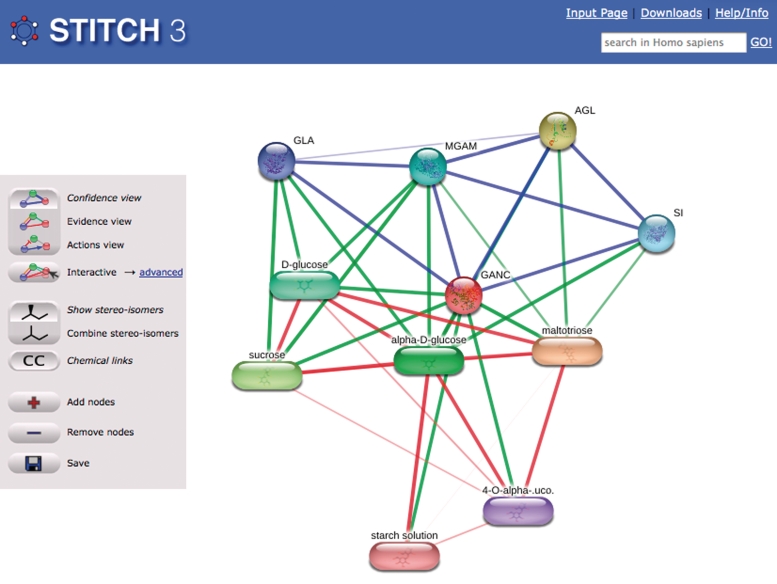

STITCH enables the user to query the database for chemical or protein names, for InChIKeys and for SMILES strings. If a chemical is entered and no target species for the interacting proteins has been selected, the species with the most confident interactions is chosen automatically. The user is presented with a network view in which nodes and edges can be clicked to retrieve more information (Figure 1). For proteins and chemicals, the structure, annotation and links to source databases are shown. For edges, the available scores are shown with links to pages with more details and, importantly, links to source databases so that the user can ascertain the providence of the underlying evidence. An interactive view allows for re-arrangement and ad hoc clustering of nodes, and three modes provide different views on the network. In the confidence view, single edges connect the items with thickness proportional to the confidence. In evidence and actions view, multiple edges can connect a pair of items, each edge representing a given type of evidence (e.g. text mining or experimental evidence) or action (e.g. activation or binding), respectively.

Figure 1.

The interaction network of neutral alpha-glucosidase C. The example screenshot shows the STITCH interface, with buttons to change the network view on the left side. With the top three buttons, views can be selected to different types of information on the edges: in confidence view (shown), the thickness corresponds to the confidence of the interaction. In evidence and actions view, multiple lines are shown representing the types of supporting evidence or types of interactions. Note that ‘show stereo-isomers’ is selected in the next set of buttons, to distinguish the different isomeric carbohydrates.

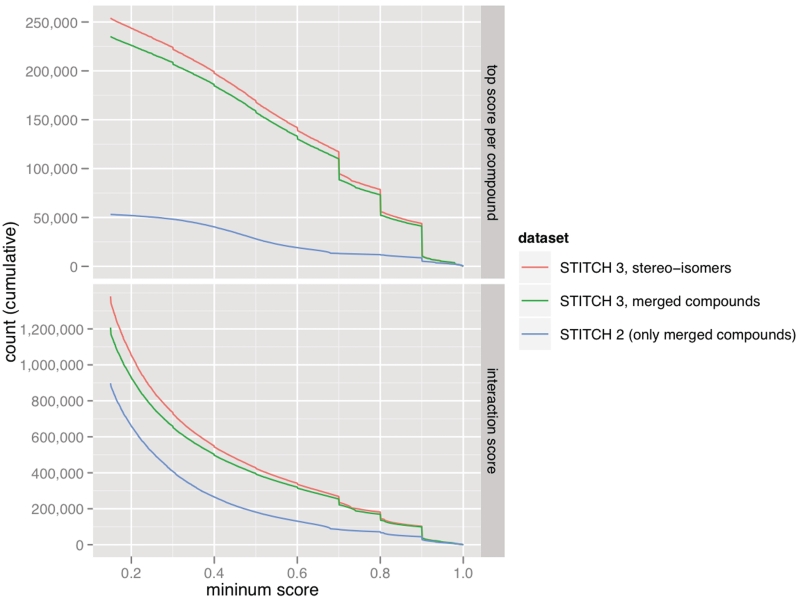

Here, we present the third release of the STITCH database, which can be accessed at http://stitch.embl.de. In this release, we have added import of interaction data from three databases: ChEMBL, TTD and DIPS (1,7,8). Compared to the previous version, STITCH 2 (2), the number of chemicals with interactions increases from 74 000 to 312 000. In human, interactions for 235 000 chemicals are available (Figure 2). We assign confidence scores to the interactions to reflect the level of significance and certainty of an interaction. 110 000 chemicals have high-confidence interactions with human proteins (i.e. a confidence score of at least 0.7), compared with 13 000 in the previous version. The human protein–chemical interaction network contains 254 000 high-confidence edges, compared to 85 000 in the previous version (Figure 2). The number of available organisms increases from 630 to 1133. Across all species, chemicals are associated with 2.6 million out of 5.2 million proteins. (As a simplification, only one gene product per gene is considered.) We further increased the resolution of the chemical network: it is now possible to ‘zoom in’ on compounds to see the stereoisomers of each compound and which interactions have been assigned to specific stereoisomers.

Figure 2.

Cumulative distribution of scores. For each confidence score cutoff, the number of chemicals (top) and protein–chemical interactions (bottom) that have at least this confidence score in the human protein–chemical network. For example, there are 110 000 chemicals with a high-confidence interaction (score at least 0.7). Note that interactions with confidence scores below 0.15 are not stored in STITCH. Steps in the data correspond to large numbers of compounds that have a maximum score in manually curated databases or the ChEMBL database (with different confidence levels).

SOURCES OF INTERACTIONS

The available information on protein–chemical interactions can be divided into four groups: First, repositories of experimental information: ChEMBL (1), PDSP Ki Database (9), BindingDB (10) and PDB (11). Second, manually curated sources of drug targets: DrugBank (12), GLIDA (13), Matador (14), TTD (15) and CTD (16). Third, manually curated pathway databases: KEGG (17), NCI/Nature Pathway Interaction Database (http://pid.nci.nih.gov), Reactome (18) and BioCyc (19). Fourth, interaction information that we extract from the literature through co-occurrence text mining and Natural Language Processing (20,21).

The STITCH database also provides relations between chemicals. Pathway databases link substrate and products of metabolic reactions. Similar mechanisms of action can be predicted from the NCI60 cell line panel (3) and from the Connectivity Map using the DIPS method (8), which tests for similarities between compounds in changes of gene expression upon treatment. The MeSH database has annotated pharmacological actions that also hint at shared targets. Using these sources, we link compounds that are predicted to have a common mechanism of action. Thus, if a compound has little available information, the user might be able to find better studied compounds with similar activities. To provide crucial context for the aggregated protein–chemical interactions, protein–protein interactions from the STRING 9.0 database (22) are incorporated into a seamless network view. Parts of the source databases, like pathways from KEGG or many kinds of curated data in ChEMBL cannot be mapped to the STITCH network. For this reason, we include links to the following databases in the chemical pop-up window: PubChem (23,24), ChEMBL (1), DrugBank (12), KEGG (17) and the SIDER database of drug side effects (25). We also provide links to search Google and ChemSpider with the InChIKey of the chemical compound.

Since the inception of the STITCH database, the quality of the annotations of chemical space has improved. PubChem has become a stable resource, and many of STITCH’s source databases (e.g. ChEMBL and BindingDB) now deposit their chemical entities into PubChem, thus making it easier to link between the chemical space as defined by PubChem and the activity space described in the source databases.

EXPANDING COMPOUNDS INTO STEREO-ISOMERS

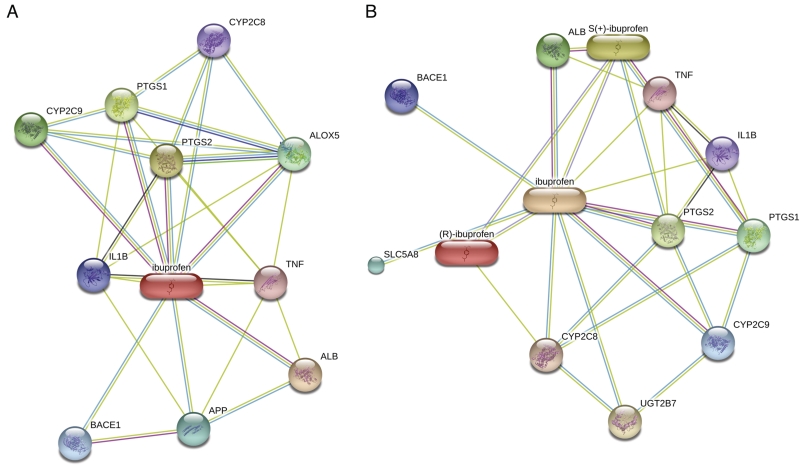

When preparing the first release of STITCH in 2007 (3), we decided to merge different salt forms and stereoisomers of active molecules to combine as much information as possible (Figure 3A). In the meantime, the amount of available information has increased drastically. We therefore now offer the option to ‘zoom in’ on the stereoisomers of a compound (Figure 3B). When a user searches for a compound, it is checked whether the name refers to a compound with or without assigned stereochemistry. For example, searching for ‘thalidomide’ will show a network with merged stereoisomers. However, searching for ‘D-thalidomide’ will show this specific stereoisomer in the stereo-specific zoom level. From the network view, the user can toggle whether stereoisomers should be merged or not (Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Stereo-specific interactions of S(+)-ibuprofen. (A) The interaction network of ibuprofen with merged stereoisomers. (B) When isomers are not merged, most interactions still connect to the form without assigned stereochemistry (labeled ibuprofen). There is also interaction evidence for the active isomer, S(+)-ibuprofen, while R(-)-ibuprofen has almost no high-confidence edges.

The set of compounds displayed in STITCH is generated from PubChem (23,24). We first merge salt forms of compounds into the record of the main compound, generating a set of compounds that include stereochemistry. Second, compounds that are designated by PubChem as having the same connectivity are merged. This merges stereoisomers, but also isotopic isomers, which usually have no associated interactions in STITCH. When a user zooms in on a compound, only those isomers with associations (in any species) are shown. For example, thalidomide has 47 isomers in the database, but only three of those have interactions: thalidomide (without assigned stereochemistry), R-(+)-thalidomide, and S-(−)-thalidomide.

Names are assigned in a two-step process: For a given name, all compound identifiers are first mapped to their main identifier (i.e. merging salt forms and isomers, as described above). Second, after the name has been assigned without considering its stereochemistry, it is assigned to a specific isomer of the chosen main identifier. For example, the name ‘rapamycin’ is associated with 15 PubChem compound identifiers, with conflicts between important sources like KEGG, DrugBank, ChEBI and ChEMBL. However, all but two of them correspond to the same scaffold, i.e. are merged by the isomer-merging step. To assign a name to the correct isomer, we have developed heuristics that prioritize PubChem’s source databases. (Compounds in PubChem are deposited by many source databases, but there is no further data annotation.) Based on a small set of benchmark chemicals, we have assigned the highest priority to ChEMBL, KEGG and LeadScope. Next come ChEBI and xPharm, then all other sources. Names from the sources MMDB and ChemIDPlus receive the lowest priority. For each name, the compound with the sources of highest priority is chosen. In case of ties, the name is discarded. Nonetheless, if a name is supplied by only one depositing database, it is not possible to check if it is correct. As names without stereochemistry can be sourced from more databases, the assignment between chemical names and scaffolds will usually be more reliable than the assignment between names and compounds with full stereochemistry. In particular, there are compound names that hint at chirality, but are associated with compounds that do not have assigned stereochemistry.

USE CASES

Most users will access the STITCH database via its web interface to interactively query for networks (Figures 1 and 3). Networks can be exported in different formats, including high-resolution images. Via the download files, which are available under Creative Commons licenses (with separate commercial licensing for a subset), STITCH can also be used for large-scale computational studies. Kapitzky, Beltrão et al. screened for protein–chemical interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (4). Using the STITCH confidence score, they defined a set of high-confidence interactions between compounds and protein modules (i.e. complexes or proteins with shared Gene Ontology annotations), which they then used to benchmark their screening results. Kalinina et al. developed a method to predict drug–target interactions from 3D structures (5), which they then tested for the overlap with interactions in STITCH 2 (2), DrugBank (26), BindingDB (10) and ChEMBL (1). STITCH 2 has also been used as part of the validation in the prediction of drug–target relations by Meslamani and Rognan (6).

FUNDING

Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Protein Research (partial). Funding for open access charge: European Molecular Biology Laboratory.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaulton A, Bellis LJ, Bento AP, Chambers J, Davies M, Hersey A, Light Y, McGlinchey S, Michalovich D, Al-Lazikani B, et al. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1100–D1107. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhn M, Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Campillos M, Mering von,C, Jensen LJ, Beyer A, Bork P. STITCH 2: an interaction network database for small molecules and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D552–D556. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhn M, Mering von,C, Campillos M, Jensen LJ, Bork P. STITCH: interaction networks of chemicals and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D684–D688. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapitzky L, Beltrao P, Berens TJ, Gassner N, Zhou C, Wüster A, Wu J, Babu MM, Elledge SJ, Toczyski D, et al. Cross-species chemogenomic profiling reveals evolutionarily conserved drug mode of action. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010;6:451. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalinina OV, Wichmann O, Apic G, Russell RB. Combinations of protein-chemical complex structures reveal new targets for established drugs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1002043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meslamani J, Rognan D. Enhancing the accuracy of chemogenomic models with a three-dimensional binding site kernel. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:1593–1603. doi: 10.1021/ci200166t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu F, Han B, Kumar P, Liu X, Ma X, Wei X, Huang L, Guo Y, Han L, Zheng C, et al. Update of TTD: Therapeutic Target Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D787–D791. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iskar M, Campillos M, Kuhn M, Jensen LJ, van Noort V, Bork P. Drug-induced regulation of target expression. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth BL, Lopez E, Patel S, Kroeze W. The multiplicity of serotonin receptors: uselessly diverse molecules or an embarrassment of riches? Neuroscientist. 2000;6:252–262. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu T, Lin Y, Wen X, Jorissen RN, Gilson MK. BindingDB: a web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D198–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knox C, Law V, Jewison T, Liu P, Ly S, Frolkis A, Pon A, Banco K, Mak C, Neveu V, et al. DrugBank 3.0: a comprehensive resource for ‘omics’ research on drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D1035–D1041. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okuno Y, Yang J, Taneishi K, Yabuuchi H, Tsujimoto G. GLIDA: GPCR-ligand database for chemical genomic drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D673–D677. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Günther S, Kuhn M, Dunkel M, Campillos M, Senger C, Petsalaki E, Ahmed J, Urdiales EG, Gewiess A, Jensen LJ, et al. SuperTarget and Matador: resources for exploring drug-target relationships. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D919–D922. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Ji ZL, Chen YZ. TTD: Therapeutic Target Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:412–415. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis AP, Murphy CG, Saraceni-Richards CA, Rosenstein MC, Wiegers TC, Mattingly CJ. Comparative Toxicogenomics Database: a knowledgebase and discovery tool for chemical-gene-disease networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D786–D792. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Hirakawa M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2010;38:D355–D360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Croft D, O’Kelly G, Wu G, Haw R, Gillespie M, Matthews L, Caudy M, Garapati P, Gopinath G, Jassal B, et al. Reactome: a database of reactions, pathways and biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D691–D697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caspi R, Altman T, Dale JM, Dreher K, Fulcher CA, Gilham F, Kaipa P, Karthikeyan AS, Kothari A, Krummenacker M, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D473–D479. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saric J, Jensen LJ, Ouzounova R, Rojas I, Bork P. Extraction of regulatory gene/protein networks from Medline. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:645–650. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen LJ, Saric J, Bork P. Literature mining for the biologist: from information retrieval to biological discovery. Nature Rev. Genet. 2006;7:119–129. doi: 10.1038/nrg1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, Doerks T, Stark M, Muller J, Bork P, et al. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Xiao J, Suzek TO, Zhang J, Wang J, Bryant SH. PubChem: a public information system for analyzing bioactivities of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W623–W633. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bolton E, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, DiCuccio M, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D38–D51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhn M, Campillos M, Letunic I, Jensen LJ, Bork P. A side effect resource to capture phenotypic effects of drugs. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010;6:343. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, Cheng D, Shrivastava S, Tzur D, Gautam B, Hassanali M. DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D901–D906. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]