Abstract

FungiDB (http://FungiDB.org) is a functional genomic resource for pan-fungal genomes that was developed in partnership with the Eukaryotic Pathogen Bioinformatic resource center (http://EuPathDB.org). FungiDB uses the same infrastructure and user interface as EuPathDB, which allows for sophisticated and integrated searches to be performed using an intuitive graphical system. The current release of FungiDB contains genome sequence and annotation from 18 species spanning several fungal classes, including the Ascomycota classes, Eurotiomycetes, Sordariomycetes, Saccharomycetes and the Basidiomycota orders, Pucciniomycetes and Tremellomycetes, and the basal ‘Zygomycete’ lineage Mucormycotina. Additionally, FungiDB contains cell cycle microarray data, hyphal growth RNA-sequence data and yeast two hybrid interaction data. The underlying genomic sequence and annotation combined with functional data, additional data from the FungiDB standard analysis pipeline and the ability to leverage orthology provides a powerful resource for in silico experimentation.

INTRODUCTION

The recent dramatic increase in the number and scale of genome sequence and functional genomic data (i.e. proteomic, microarray, RNA-sequence, ChIP–ChIP, etc.) has made it increasingly challenging for scientists to navigate through the milieu of data. Importantly, it has become essential to be able to interrogate data sets from multiple genomes in an integrated fashion. To this end, FungiDB (http://fungidb.org) was developed as a resource for genomic and functional genomic data across the fungal kingdom.

FungiDB was developed in partnership with the NIAID-funded Eukaryotic Pathogen Bioinformatic Resource Center (http://eupathdb.org) (1). As such this resource uses the same database structural framework and employs the graphical strategies Web Development Kit (WDK) search interface (2). Current genomes in FungiDB are primarily obtained via the Broad Institute (http://broadinstitute.org) and the dedicated Aspergillus, Candida and Saccharomyces Genome resources (3–5).

FungiDB provides a data-mining interface to the comparative and functional genomic data of multiple species of fungi that differs from the species-focused resources of SGD, CGD and AspGD and provides an integrated query system as part of the WDK and GUS database structure. FungiDB differs from other resources such as Ensembl Fungi (6), the Joint Genome Institute's Mycocosm (http://jgi.doe.gov/fungi) and IMG tools (7) or Microbes Online (8), which provide complementary data query or visualization tools but do not have the data mining capabilities and broad cross-species comparisons that are possible with the WDK search interface.

Data are currently obtained directly from providers at sequencing centers, GenBank and associated functional data repositories (GEO or SRA), or the key model organism databases SGD, CGD and AspGD. The initial 1.0-β release focused on sets of genomes of a cluster of Aspergillus species, and key species available from the Basidiomycota primarily provided by the Broad Institute or the Joint Genome Institute.

GENOMES AND DATA IN THE CURRENT RELEASE OF FUNGIDB

The current release of FungiDB contains genome sequence and annotation from 17 annotated fungal genomes (Aspergillus clavatus, A. flavus, A. fumigatus, A. nidulans, A. niger, A. terreus, Candida albicans, Coccidioides immitis (strain RS), Cryptococcus neoformans, Fusarium graminearum, F. oxysporum, Fusarium verticillioides (Gibberella moniliformis), Magnaporthe oryzae, Neurospora crassa, Puccinia graminis, Rhizopus oryzae and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and one unannotated strain (H538.4) of C. immitis, providing 650 Mb of sequence and 207 111 genes. Specific details about these genomes are available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Species in the current release of FungiDB

| Phylum | (sub)Class | Species | Strain | Genome size (Mbs) | No. of genes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota | Eurotiomycetes | Aspergillus clavatus | NRRL1 | 27.86 | 9413 | (9) |

| Aspergillus flavus | NRRL3357 | 36.79 | 12730 | NA | ||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Af293 | 29.39 | 10067 | (10) | ||

| Aspergillus nidulans | FGSC A4 | 30.5 | 10865 | (11) | ||

| Aspergillus niger | ATCC 1015 | 37.20 | 6679 | (12) | ||

| Aspergillus terreus | NIH 2624 | 29.33 | 10564 | NA | ||

| Coccidioides immitis | H538.4 | 27.73 | 10640 | (13) | ||

| Coccidioides immitis | RS | 28.95 | 9878 | (14) | ||

| Sordariomycetes | Fusarium graminearum | PH-1 (NRRL 31084) | 36.45 | 13605 | (15) | |

| Fusarium oxysporum | f.sp.4287 | 61.4 | 17466 | (16) | ||

| Fusarium verticillioides (Gibberella moniliformis) | 7600 | 41.78 | 14457 | (16) | ||

| Magnaporthe oryzae (Magnaporthe grisea) | 70-15 | 41.70 | 11385 | (17) | ||

| Neurospora crassa | OR74A | 41.04 | 10154 | (18) | ||

| Saccharomycetes | Candida albicans | SC5314 | 14.32 | 6444 | (19) | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | S288c | 12.16 | 6926 | (20) | ||

| Basidiomycota | Pucciniomycetes | Puccinia graminis f.sp. tritici | CRL 75-36-700-3 | 88.65 | 21065 | (21) |

| Tremellomycetes | Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii | H99 | 18.88 | 7121 | NA | |

| Mucormycotina (Zygomycota) | Rhizopus oryzae (Rhizopus delemar) | RA 99-880 | 46.09 | 17652 | (22) |

All genomes were downloaded from their sources in January 2011. Additional information is available at http://s.fungidb.org/GenomeDataTypes.

FungiDB also contains several functional genomic data sets: (i) EST data obtained from dbEST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbEST/) (23) for A. flavus, A. terreus, A. niger and G. moniliformis; (ii) cell cycle microarray data for S. scerevisiae based on different synchronization methods (24, 25); (iii) RNA-sequence data from R. oryzae during hyphal growth (Stajich, J.E., Sain, D., Abramyan, J., unpublished data); and (iv) yeast two hybrid data from S. cerevisiae (5).

Genomes and annotation in FungiDB are processed through the same analysis pipeline, which provides additional data, including InterPro domains (26), gene ontology term association (27), signal peptide predictions (28), transmembrane domain predictions, open reading frame predictions, BLAST against the non-redundant genome database at the National Center for Bioinformatics (NCBI), orthology prediction based on OrthoMCL (29) and synteny prediction. Pipeline details are available at http://s.fungidb.org/pipeline_methods.

HOW TO USE FUNGIDB

The home page

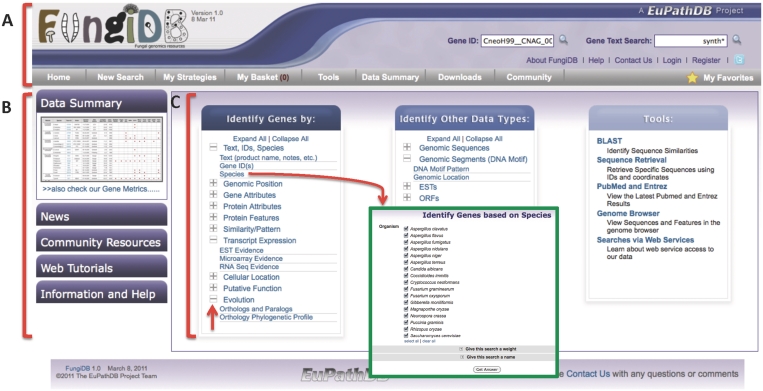

The FungiDB web interface is designed to provide the user with convenient and straightforward access to the underlying data (Figure 1). The home page is divided into three main sections, the banner (Figure 1A), information and help menus (Figure 1B) and searches and tools (Figure 1C). The banner section appears on all FungiDB pages providing users with quick access to GeneID and text searches, ‘contact us’ form, registration/login and information from any page on the site. Creating an account and logging in allows search strategies to be saved and shared, gene lists to be saved, and to create gene associated annotation comments that are attributed to the author. The gray tool bar section of the banner consists of a series of mouse-over menus that link to all tools and searches in this resource. The expandable information and help menus on the left-hand side of the home page (Figure 1B) provide access to a data summary table of all data in FungiDB, a news section, community resources (including useful links and upcoming events), web tutorials and additional help and information. The central section contains links to all searches and tools in FungiDB, and clicking on the plus symbols (arrow in Figure 1C) expands the various categories to reveal the underlying searches (Figure 1C). These include searches that return sets of genes (left column of Figure 1C), searches that return other data types such as expressed sequence tags (ESTs), open reading frames (ORFs), genomic segments (these include DNA motifs) and genomic sequences (i.e. scaffolds and chromosomes) (central column of Figure 1C) and tools in the right-hand column of Figure 1C, including access to the GMOD genome browser (30), BLAST (31), the sequence retrieval tool, access to web services searches and a list of fungal-related literature (based on PubMed searches).

Figure 1.

Screen shot of the FungiDB home page. (A) The banner section present on all FungiDB webpages provides links to registration, login, and contact us forms, ID and text searches, information and help, and all available searches and tools. (B) The side bar provides expandable tabs with information such as a data summary table, community events, news, tutorials and help links. (C) The central portion of the home page contains three sections, the left column contains searches that return genes, the middle column contains searches that return other entities such as genomic sequence, ESTs, DNA motifs and the third (right column) section contains tools such as BLAST, sequence retrieval and web services. The plus symbols can be expanded to reveal specific searches (upward pointing red arrow). Green insert is an example search page following selection of a ‘genes by species’ search.

Performing a search in FungiDB

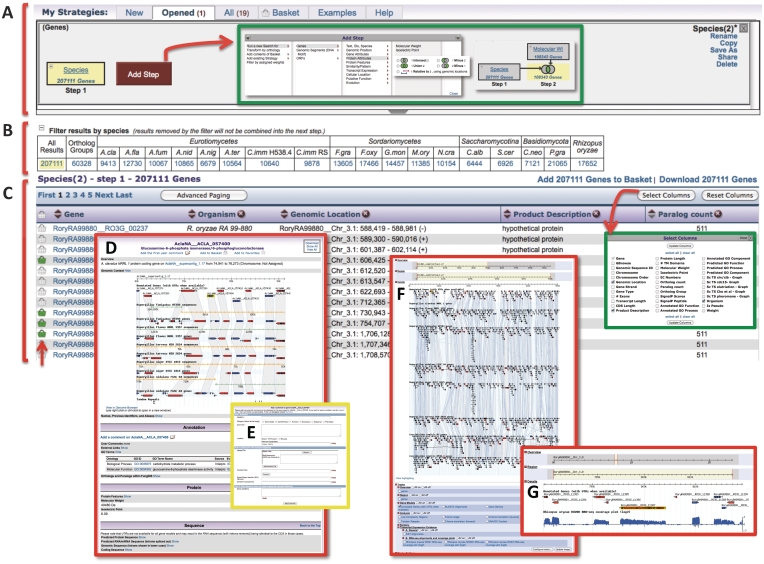

A search in FungiDB is initiated by selecting a search type, which opens a new page with additional parameters that can be set. For example, selecting a ‘genes by species search’ opens a new page where a user can select which organisms to include in the search (Figure 1C insert, green box). Once a search is executed, results are displayed as the first step in a search strategy (see building a search strategy below). In the example shown in Figure 2, a search for all genes in all species in FungiDB returns 207 111 genes (note the number of genes is displayed in the first step of the strategy, yellow box Figure 2A). The distribution of the gene results from step 1 among the various species in FungiDB is displayed in a filter table below the strategy (Figure 2B). A user can toggle between the various species-specific results by selecting the number in the desired cell. The actual results list of what is selected (yellow highlighted step and cell) is displayed in a dynamic table below the filter table (Figure 2C). Users may navigate through the results by selecting specific page numbers, clicking on next/previous (or first/last), and choosing the number of results to display/page by selecting ‘advanced paging’. In addition, columns may be added to the results table by clicking on ‘select columns’ and choosing which columns to display (green insert, Figure 2C). The columns in the results table may be removed (click on the ‘x’ to the right of a column title), moved (drag and drop) or sorted (clicking on the up/down arrows to the left of a column title). Individual items in the results table may be added to the basket (see below) by clicking on the basket icon (arrow, Figure 2C). Also, individual records (for example gene pages) may be accessed by clicking on the item ID in the first column of each result list (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

(A) Screen shot of a search strategy with the first step being the results of running the search shown in Figure 1C (inset). Engaging the ‘Add Step’ button reveals a popup with all available searches in FungiDB. Set operations (intersect, union and minus) are used to combine searches with each other in a search strategy (green box). (B) The filter table appears below the search strategy and shows results across all species in FungiDB. Selecting any of the cells will filter the results and show them in the results table shown in C. (C) The results of any search are displayed in a dynamic table that allows removing (click on the ‘x’ next to the column name), adding (green box) and moving (drag and drop) columns, downloading results and adding results to the basket (red upward pointing arrow). (D) Selecting any of the record IDs in the first column opens a record page (the gene page is shown in D). The gene page includes sections including the gene ID and gene product name, genomic context showing synteny with related species in FungiDB, annotation with links to the ‘User Comment’ form (shown in E), protein information (i.e. interpro domains, hydropathy plots, signal peptide prediction, etc.), expression data (where available) and the sequence. (E) The user comment form allows comments by the community including free text, PubMed IDs, GenBank accession numbers, attaching images and files, and linking comments to multiple records. (F) A genome browser view in FungiDB accessible from the genomic context view in the gene page or the tools section. Tracks can be loaded in the genome browser such as synteny as shown in F and RNA sequence coverage plots as seen in (G).

BUILDING A SEARCH STRATEGY IN FUNGIDB

The search strategy system implemented in FungiDB (1) is designed to encourage users to run in silico experiments. After running the initial search, the search strategy may be expanded by clicking on add step (red button, Figure 2A). Once the add step button is engaged, a popup (Figure 2A, green box) of all searches in FungiDB is revealed and the results of any chosen search may be combined with the results of the previous search using a set operation (intersect, union or minus). Steps in a strategy may be viewed, revised, renamed and developed further by nesting or deleted. Furthermore, entire search strategies may be renamed, copied, saved and shared with a unique strategy URL or deleted.

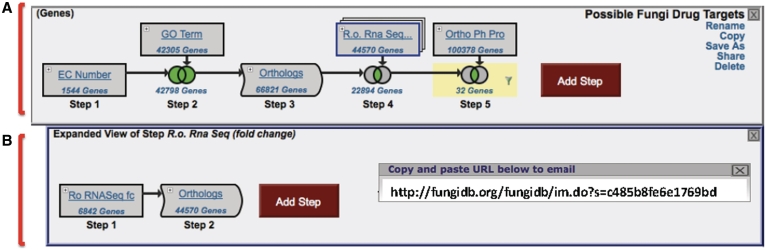

The multi-step search strategy in Figure 3 defines potential drug targets in C. neoformans by identifying enzymes that may be associated with growth using cross-species comparisons. Step 1 of the strategy identifies all genes with an enzyme commission (EC) number (available data in FungiDB is from S. cerevisiae) to start with a set of known enzymes. Step 2 combines the results of Step 1 with all genes in FungiDB that have an associated metabolic process gene ontology (GO) term (automatically assigned to all genomes in FungiDB as part of the standard analysis pipeline) using a union operation to identify additional potential enzymes with this GO annotations. Step 3 transforms the results from Step 2 into their orthologs in all fungal organisms in FungiDB into C. neoformans genes. In Step 4, the results are intersected with genes that are upregulated during hyphal growth in R. oryzae [note that this step is actually a nested strategy (Figure 3B) where the R. oryzae results are transformed into their FungiDB orthologs] to find genes that are likely involved during active growth of the fungus and its cell wall. Since an actively growing RNA-Seq data set was not available for C. neoformans, one can use the R. oryzae set to filter the genes. Step 5 is a result of intersecting Step 4 with all genes in FungiDB that do not have orthologs in bacteria, archeae and non-fungal eukaryotes (based on OrthoMCL results) in order to find genes which are unique to Fungi. The final list of results is then filtered on C. neoformans using the filter table as described above to reveal 32 genes. While clearly a hypothetical list of potential drug targets, it is intriguing to note that several known drug targets appear in the list including, the glucan 1,3 β-glucosidase gene (S. cerevisiae FKS1 homolog), which is the target of echinocandins, and an oxysterol-binding protein involved in ergosterol synthesis (target of amphotericin B). This strategy maybe viewed and shared using the following URL: http://fungidb.org/fungidb/im.do?s=c485b8fe6e1769bd.

Figure 3.

Screen shot of a multi-step search strategy in FungiDB. (A) The main body of the search strategy—Step 1 asks for all genes in FungiDB annotated with an EC number, Step 2 uses a union operation to combine results from Step 1 with all genes with ‘metabolic process’ genome ontology association, Step 3 transforms the results from Step 2 into their orthologs in all species in FungiDB, Step 4 intersects results from Step 3 with a substrategy (B), Step 5 intersects the results of Step 4 with results from an orthology phylogenetic pattern search that asks for all genes in FungiDB that do not have orthologs in mammals. A filter is applied (see Figure 2B) to the results in Step 5 to reveal only C. neoformans genes. (B) An expanded view of the substrategy that was combined with Step 3 in A, which defines all orthologs of genes in R. oryzae that are upregulated in hyphae based on RNA sequence data. Saved strategies may be shared with others using a unique strategy URL shown in the inset (http://fungidb.org/fungidb/im.do?s=c485b8fe6e1769bd).

ADDITIONAL FEATURES IN FUNGIDB

Favorites

The favorites tool allows users of FungiDB to bookmark their favorite genes for quick future access. Adding or removing a gene to the favorites can be done by clicking on the favorites icon (star) on gene pages (Figure 2D). Accessing the favorites page is achieved via the favorites link in the gray tool bar (Figure 1A). Genes in the favorites page can be assigned to user-defined projects and free text can be added to each gene.

Basket

The basket tool allows a user to cherry pick individual results (i.e. genes, ESTs and genomic sequences) and place them in the basket for further analysis. Adding items to the basket can be achieved by clicking on the basket icon in a list of results (Figure 2C) or at the top of a record page (Figure 2D). Once a desired set of items have been added to the basket, a user may add the basket contents to a search strategy and analyze the results by combining with other data in FungiDB.

Weighted searches

Weighting allows a user to add arbitrary weights to steps in a strategy. As the strategy grows, the results are sorted by the sum of their weights. For this feature to function properly, steps need to be combined using the union operation. The benefit of using this feature is that items that do not meet all the criteria in a strategy are not lost but rather appear in the final result list, albeit ranked lower down the list. As an example, the strategy described in Figure 3A was weighted (each step was weighted on a scale from 1 to 10): details are available at http://fungidb.org/fungidb/im.do?s=3921e20d384bd503.

Although the final result list expands dramatically (as expected since the union operation was used to combine steps), it is returned as a ranked list. Additional high-interest genes that appear as top hits in the weighted search include sulfite reductase.

Genomic colocation

This tool enables users to identify genomic features based on their relative location to each other on the genome. For example, a user can identify a DNA motif in their favorite fungal genome and then find genes that have one of these motifs within 1000 bp of their 5′-end. One can then ask questions about this list of motif containing genes such as when they are expressed or what GO terms are associated with them.

User comments

Comments by users may be added to record pages (such as gene pages) in FungiDB by clicking on the add comment link (Figure 2D and E). The comment form provides a user with a quick and straightforward mechanism to enhance FungiDB with their information, which may include free text, references (by entering PubMed or digital object IDs), NCBI accession numbers, images and documents, and genomic location coordinates. Moreover, a comment may be linked to multiple records in the database using their IDs. Once a user submits a comment it appears immediately for all users on the record page and becomes searchable via the text search functionality.

DATA DOWNLOAD AND SEQUENCE RETRIEVAL

Data in FungiDB are conveniently available for bulk download from the ‘Data Files’ section accessible from the ‘Downloads’ menu item in the gray tool bar (Figure 1A). Data files are in folders organized by database release version number and species. Within each species-specific directory, data may be downloaded in FASTA, text or GFF formats.

The sequence retrieval tool, accessible from the tools section (Figure 1C) allows users to specify exact coordinates to be downloaded. Additionally, results of searches maybe downloaded in bulk and in a defined manner. For example, one may choose to download 300-nt upstream of the translation start site of a set of genes in a search strategy to allow dumping of promoter sequences for the genes that resulted from a query.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

FungiDB is expected to dramatically expand over the next few years to include >100 genome sequences and annotation. This will fill more phylogenetic diversity and cover additional plant and animal pathogenic fungi to allow for comparisons of common genomic traits among related and independent origins of pathogenecity. Importantly, the functional data portion is expected to accumulate multiple data sets from high-throughput proteomics (32), transcriptomics and metabolomics (33) studies to enable data mining and querying within a species data that can connect genes to function. The housing of many sets of functional genomics information will allow data to be applied to those organisms with less experimental data through comparative analyses thus assisting informing potential gene function in less tractable study organisms.

The work underway to further develop FungiDB is focused on enabling a ‘franchise model’ of the EuPathDB system where the site runs entirely independently from the present core EuPathDB system. This will greatly simplify the efforts needed to deploy instances of EuPathDB for groups of species as independent instances of the database and website since the tools are general purpose and the WDK search interfaces useful to a variety of groups of organisms. This will provide more generic installation of the software that runs EuPathDB to support clade-specific databases and websites such as FungiDB. Future work will also provide standalone installation documentation to instruct on best practices to deploy, configure and load data into the system.

FUNDING

The Burroughs Wellcome Fund (BWF) to build a Pan-Fungal genome database and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (to J.E.S.) to support creation of a data analysis core (MoBeDAC) for microbial community analyses of the Built Indoor Environment to support the curation and deployment of data in FungiDB for metagenomic applications. Funding for open access charge: Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The decision to launch this project emerged from a BWF sponsored meeting in February 2010 to build a community resource to provide better access to the fungal genome resources available.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Fischer S, Gajria B, Gao X, et al. EuPathDB: a portal to eukaryotic pathogen databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D415–D419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer S, Aurrecoechea C, Brunk BP, Gao X, Harb OS, Kraemer ET, et al. The strategies WDK: a graphical search interface and web development kit for functional genomics databases. Database. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1093/database/bar027. bar027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnaud MB, Chibucos MC, Costanzo MC, Crabtree J, Inglis DO, Lotia A, et al. The Aspergillus Genome Database, a curated comparative genomics resource for gene, protein and sequence information for the Aspergillus research community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D420–D427. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skrzypek MS, Arnaud MB, Costanzo MC, Inglis DO, Shah P, Binkley G, et al. New tools at the Candida Genome Database: biochemical pathways and full-text literature search. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D428–D432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engel SR, Balakrishnan R, Binkley G, Christie KR, Costanzo MC, Dwight SS, et al. Saccharomyces Genome Database provides mutant phenotype data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D433–D436. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kersey PJ, Lawson D, Birney E, Derwent PS, Haimel M, Herrero J, et al. Ensembl Genomes: extending Ensembl across the taxonomic space. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D563–D569. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markowitz VM, Chen I-MA, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Szeto E, Grechkin Y, et al. The integrated microbial genomes system: an expanding comparative analysis resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D382–D390. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dehal PS, Joachimiak MP, Price MN, Bates JT, Baumohl JK, Chivian D, et al. MicrobesOnline: an integrated portal for comparative and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D396–D400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedorova ND, Khaldi N, Joardar VS, Maiti R, Amedeo P, Anderson MJ, et al. Genomic islands in the pathogenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nierman WC, Pain A, Anderson MJ, Wortman JR, Kim HS, Arroyo J, et al. Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature. 2005;438:1151–1156. doi: 10.1038/nature04332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galagan JE, Calvo SE, Cuomo C, Ma L-J, Wortman JR, Batzoglou S, et al. Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae. Nature. 2005;438:1105–1115. doi: 10.1038/nature04341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen MR, Salazar MP, Schaap PJ, van de Vondervoort PJI, Culley D, Thykaer J, et al. Comparative genomics of citric-acid-producing Aspergillus niger ATCC 1015 versus enzyme-producing CBS 513.88. Genome Res. 2011;21:885–897. doi: 10.1101/gr.112169.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neafsey DE, Barker BM, Sharpton TJ, Stajich JE, Park DJ, Whiston E, et al. Population genomic sequencing of Coccidioides fungi reveals recent hybridization and transposon control. Genome Res. 2010;20:938–946. doi: 10.1101/gr.103911.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharpton TJ, Stajich JE, Rounsley SD, Gardner MJ, Wortman JR, Jordar VS, et al. Comparative genomic analyses of the human fungal pathogens Coccidioides and their relatives. Genome Res. 2009;19:1722–1731. doi: 10.1101/gr.087551.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuomo CA, Güldener U, Xu J-R, Trail F, Turgeon BG, Di Pietro A, et al. The Fusarium graminearum genome reveals a link between localized polymorphism and pathogen specialization. Science. 2007;317:1400–1402. doi: 10.1126/science.1143708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma L-J, van der Does HC, Borkovich KA, Coleman JJ, Daboussi M-J, Di Pietro A, et al. Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium. Nature. 2010;464:367–373. doi: 10.1038/nature08850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dean RA, Talbot NJ, Ebbole DJ, Farman ML, Mitchell TK, Orbach MJ, et al. The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature. 2005;434:980–986. doi: 10.1038/nature03449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galagan JE, Calvo SE, Borkovich KA, Selker EU, Read ND, Jaffe D, et al. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature. 2003;422:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nature01554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones T, Federspiel NA, Chibana H, Dungan J, Kalman S, Magee BB, et al. The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7329–7334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401648101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mewes HW, Albermann K, Bähr M, Frishman D, Gleissner A, Hani J, et al. Overview of the yeast genome. Nature. 1997;387(Suppl. 6632):7–65. doi: 10.1038/42755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duplessis S, Cuomo CA, Lin Y-C, Aerts A, Tisserant E, Veneault-Fourrey C, et al. Obligate biotrophy features unraveled by the genomic analysis of rust fungi. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:9166–9171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019315108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma L-J, Ibrahim AS, Skory C, Grabherr MG, Burger G, Butler M, et al. Genomic analysis of the basal lineage fungus Rhizopus oryzae reveals a whole-genome duplication. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boguski MS, Lowe TM, Tolstoshev CM. dbEST–database for “expressed sequence tags”. Nat. Genet. 1993;4:332–333. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho RJ, Campbell MJ, Winzeler EA, Steinmetz L, Conway A, Wodicka L, et al. A genome-wide transcriptional analysis of the mitotic cell cycle. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spellman PT, Sherlock G, Zhang MQ, Iyer VR, Anders K, Eisen MB, et al. Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:3273–3297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W116–W120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gene Ontology Consortium (2009) The Gene Ontology in 2010: extensions and refinements. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:D331–D335. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein LD, Mungall C, Shu S, Caudy M, Mangone M, Day A, et al. The generic genome browser: a building block for a model organism system database. Genome Res. 2002;12:1599–1610. doi: 10.1101/gr.403602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim Y, Nandakumar MP, Marten MR. Proteomics of filamentous fungi. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JD, Kaiser K, Larive CK, Borkovich KA. Use of 1H nuclear magnetic resonance to measure intracellular metabolite levels during growth and asexual sporulation in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryotic Cell. 2011;10:820–831. doi: 10.1128/EC.00231-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]