Abstract

Knowledge and investigation of therapeutic targets (responsible for drug efficacy) and the targeted drugs facilitate target and drug discovery and validation. Therapeutic Target Database (TTD, http://bidd.nus.edu.sg/group/ttd/ttd.asp) has been developed to provide comprehensive information about efficacy targets and the corresponding approved, clinical trial and investigative drugs. Since its last update, major improvements and updates have been made to TTD. In addition to the significant increase of data content (from 1894 targets and 5028 drugs to 2025 targets and 17 816 drugs), we added target validation information (drug potency against target, effect against disease models and effect of target knockout, knockdown or genetic variations) for 932 targets, and 841 quantitative structure activity relationship models for active compounds of 228 chemical types against 121 targets. Moreover, we added the data from our previous drug studies including 3681 multi-target agents against 108 target pairs, 116 drug combinations with their synergistic, additive, antagonistic, potentiative or reductive mechanisms, 1427 natural product-derived approved, clinical trial and pre-clinical drugs and cross-links to the clinical trial information page in the ClinicalTrials.gov database for 770 clinical trial drugs. These updates are useful for facilitating target discovery and validation, drug lead discovery and optimization, and the development of multi-target drugs and drug combinations.

INTRODUCTION

Modern drug discovery is primarily focused on the search or design of drug-like molecules, which selectively interact and modulate the activity of one or a few selected therapeutic targets (1–3). One challenge in drug development is to choose and explore promising targets from a growing number of potential targets (4). Target selection and validation are important not only for achieving therapeutic efficacy but also for increasing drug development odds, given that few innovative targets have made it to the approved list each year [12 innovative targets in 1994–2005 (5) and 10 new human targets in 2006–2010 (6) for small molecule drugs]. Apart from target selection and validation, drug discovery efforts can be facilitated by enhanced knowledge of bioactive molecular scaffolds (7,8), structure–activity relationships (9), multi-target agents (10,11) and synergistic drug combinations (12) against selected target or multiple targets, and information about the sources of drug leads such as the species origins of natural product-derived drugs (13).

Internet resources such as Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (14,15) and DrugBank (16) provide comprehensive information about the targets and drugs in different development and clinical stages, which are highly useful for facilitating focused drug discovery efforts and pharmaceutical investigations against the most relevant and proven targets (17–19). In addition to the update of these databases by expanded target and drug data contents, the usefulness of these databases for facilitating drug discovery efforts can be further enhanced by adding additional information and knowledge derived from the target and drug discovery processes. Therefore, we updated TTD by both significantly expanding the target and drug data and adding new information about target validation, quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models of a variety of molecular scaffolds active against selected targets and specific types of drugs (multi-target drugs and natural product-derived drugs) and drug combinations (synergistic, additive, antagonistic, potentiative and reductive combinations).

The significantly expanded target and drug data cover 364 successful, 286 clinical trial, 44 discontinued clinical trial and 1331 research targets, and 1540 approved, 1423 clinical trial, 345 discontinued clinical trial, 165 pre-clinical and 14 853 experimental drugs linked to their primary targets (14 170 small molecule and 652 antisense drugs with available structure and sequence data) (Table 1). These are compared to 348 successful, 249 clinical trial, 43 discontinued clinical trial and 1254 research targets, and 1514 approved, 1212 clinical trial and 2302 experimental drugs in our last update (15). To facilitate the access of clinical trial information of the clinical trial drugs, cross-links to the relevant page in ClinicalTrials.gov database are provided for 770 clinical trial drugs. The newly added target validation data includes the experimentally measured potency of 11 810 drugs against 915 targets, the observed potency or effects of 497 drugs against disease models (cell lines, ex vivo, in vivo models) linked to 393 targets, and the observed effects of target knockout, knockdown or genetic variations for 307 targets (Table 2). The QSAR data consists of 841 QSAR models for active compounds of 228 chemical types against 121 targets (Table 2).

Table 1.

Statistics of drug targets, drugs and structure and sequence data in TTD database

| Data Category | 2012 update | 2010 update |

|---|---|---|

| Statistics of drug targets | ||

| Number of all targets | 2025 | 1894 |

| Number of successful targets | 364 | 348 |

| Number of clinical trial targets | 286 | 249 |

| Number of discontinued targets | 44 | 43 |

| Number of research targets | 1331 | 1254 |

| Statistics of drugs | ||

| Number of all drugs | 17 816 | 5028 |

| Number of approved drugs | 1540 | 1514 |

| Number of clinical trial drugs | 1423 | 1212 |

| Number of discontinued drugs | 345 | 274 |

| Number of pre-clinical drugs | 165 | 142 |

| Number of experimental drugs | 14 853 | 2302 |

| Statistics of drugs with available structure or sequence data | ||

| Number of small molecular drugs with available structure | 14 170 | 3382 |

| Number of antisense drugs with available sequence data | 652 | 649 |

Table 2.

Summary and statistics of newly added data in 2012 version of TTD

| Data Category | Number of Information |

|---|---|

| Target validation data | |

| Experimentally measured potency of drugs against targets | |

| Number of drugs | 11 810 |

| Number of targets | 915 |

| Drug potency against disease model (cell-lines, ex vivo, in vivo models) | |

| Number of drugs | 497 |

| Number of targets | 393 |

| The observed effects of target knockout, knockdown or genetic variations | |

| Number of targets | 307 |

| QSAR models | |

| Number of QSAR models | 841 |

| Number of Chemical types | 228 |

| Number of targets | 121 |

| Structure and potency information of multi-target agents against target pairs | |

| Number of multi-target agents | 3681 |

| Number of target pairs | 108 |

| Drug combination data | |

| Pharmacodynamically synergistic drug combinations | |

| Number of drug combinations due to anti-counteractive actions | 22 |

| Number of drug combinations due to complementary actions | 30 |

| Number of drug combinations due to facilitating actions | 20 |

| Number of pharmacodynamically additive drug combinations | 14 |

| Number of pharmacodynamically antagonistic drug combinations | 4 |

| Number of pharmacokinetically potentiative drug combinations | 19 |

| Number of pharmacokinetically reductive drug combinations | 7 |

| Natural product-derived drugs and their species origins | |

| Number of natural product-derived approved drugs | 939 |

| Number of natural product-derived clinical trial drugs | 369 |

| Number of natural product-derived pre-clinical drugs | 119 |

Moreover, we added the data partly derived from our previous studies of multi-target drugs (20,21), drug combinations (12) and natural product derived drugs (13) (Table 2). The multi-target drug data is composed of 3681 multi-target agents active against 108 target pairs together with their potencies against the target pairs. The drug combination data includes 72, 14 and 4 pharmacodynamically synergistic, additive and antagonist combinations, and 19 and 7 pharmacokinetically potentiative and reductive combinations together with their mode of actions and combination mechanisms. The natural product-derived drug data includes the drug names and their species origins and species families for 939 approved, 369 clinical-trial and 119 pre-clinical drugs.

NEW TARGET AND DRUG DATA COLLECTION

Additional target and drug data, including the approved, clinical trial and experimental drugs and their primary targets, were collected by using the same methods described in our previous publications (14,15). In particular, all TTD targets are primary targets (i.e. efficacy targets) directly responsible for the claimed therapeutic efficacies (in drug approval, clinical trial or investigations) of the corresponding drugs as confirmed by biochemical assay and strong cell based and/or in vivo evidence linking the target to drug (15,17,22). The status of approved drugs and clinical trial drugs is up-to-date as of December 2010. The discontinued clinical trial drugs are based on the report from US National Institutes of Health (NIH, http://clinicaltrials.gov/). The discontinued clinical trial targets are those clinical trial targets that no longer have an active clinical trial drug at the end of 2010. Pre-clinical drugs are drug candidates that have passed discovery stages and started such pre-clinical studies as safety, PK/ADME, active pharmaceutical ingredient preparation and formulation (23). The newly added experimental drugs were selected based on a potency cut-off value of ≤20 µM against their targets.

TARGET VALIDATION DATA

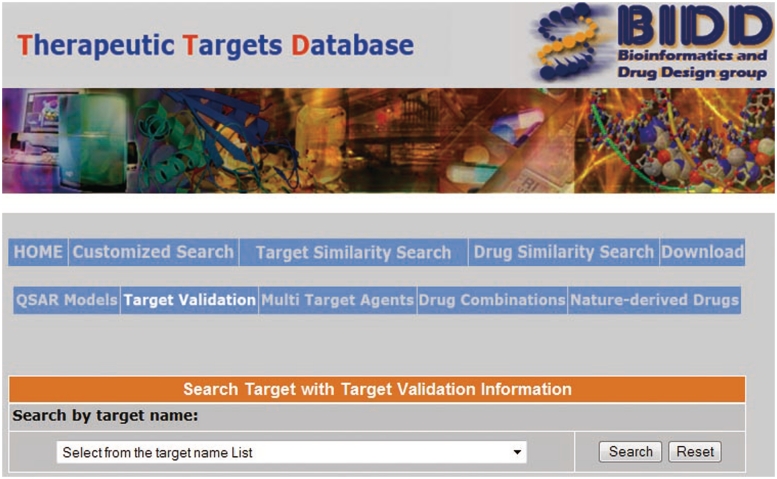

Target validation has been routinely performed to demonstrate the functional role of the potential target in disease phenotype and the ability of drug-like molecules to modulate the activities of the target to achieve therapeutic efficacies (24,25). Target validation normally requires the determination that the target is expressed in the disease-relevant cells/tissues, it can be directly modulated by a drug or drug-like molecule with adequate potency in biochemical assay, and that target modulation in cell and/or animal models ameliorates the relevant disease phenotype (24,26). In vivo target validation has been conducted mostly in knockout mice, transgenetic in vivo models, and also in RNA interference, antibody and antisense treated in vivo models (26,27). We therefore searched the PubMed database (28) to collect from literature three types of target validation data: experimentally determined potency of drugs against their primary target or targets, observed potency or effects of drugs against disease models (cell lines, ex vivo, in vivo models) linked to their primary target or targets, and the observed effects of target knockout, knockdown, transgenetic, RNA interference, antibody or antisense-treated in vivo models. Target validation data can be retrieved by clicking the ‘Target Validation’ field in the TTD home page, which lead to the TTD target validation information page wherein a user can select the relevant data for a particular target from the target name list (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The target validation information page of TTD.

QUANTITATIVE STRUCTURE–ACTIVITY RELATIONSHIP MODELS AGAINST SPECIFIC TARGET

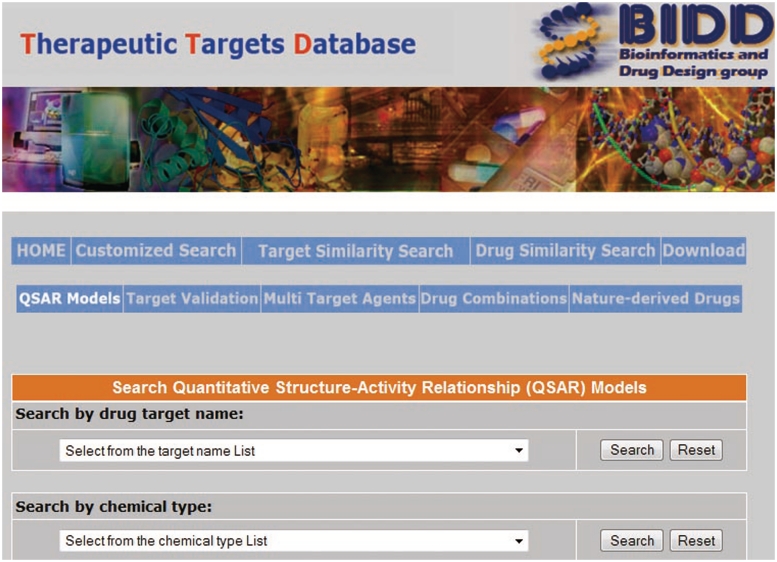

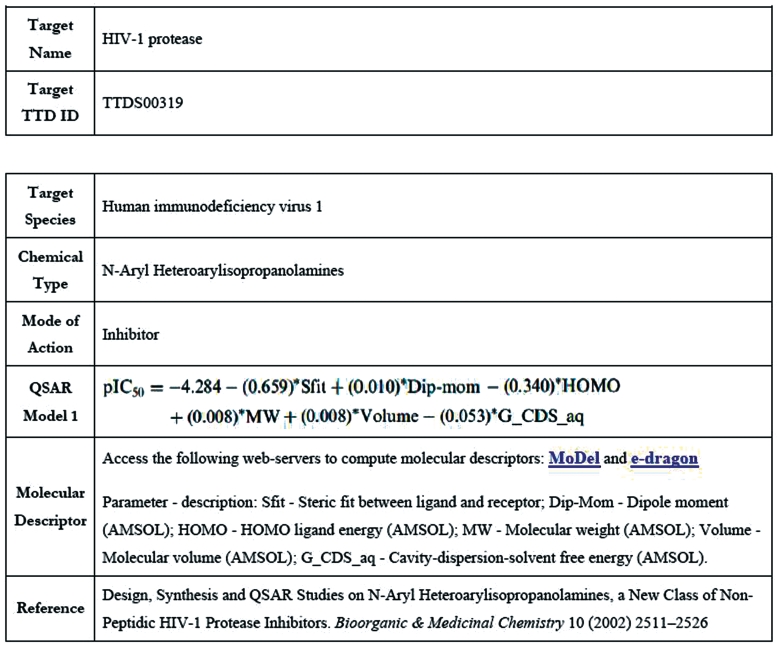

QSAR models for active compounds against many different targets have been developed and explored for drug lead discovery and optimization (9,29). These models elucidate the chemical characteristics favorable to the modulation of the activity of specific target at sufficient potency by establishing quantitative correlations between molecular properties and biological activities (e.g. 50% inhibition concentration or binding affinities) (30). In drug lead optimization projects, QSAR models against specific target can be recursively developed and used for guiding the design or search of more potent compounds or compounds with more desired drug-like properties as the new activity or drug-like property data from newly synthesized compounds become available (9,29). Therefore, knowledge of developed QSAR models for different molecular scaffolds active against different targets is highly useful for facilitating further drug development and lead optimization efforts. In addition to the QSAR models, we have collected in our previous analysis of QSAR models of bioactive compounds (31), we searched PubMed database (28) to collect 309 papers that describe 841 ligand-based QSAR models for active compounds of 228 chemical types against 121 targets. While there are also a high number of papers describing receptor-based QSAR models, these models were not included in TTD because they are not easily displayed in explicit form in a database setting without obtaining copyrights from the relevant journals. The included QSAR models can be accessed by clicking the ‘QSAR Models’ field in the TTD home page, which lead to the TTD QSAR model page wherein a user can select the relevant model for a particular chemical class against a specific target either from the target name list or the chemical type list (Figure 2). The retrieved QSAR model page (Figure 3) contains the information about target and ID, target species, chemical type, compound mode of action, QSAR models, the molecular descriptors in the QSAR models, references and hyperlinks to the molecular descriptor computation web servers MoDeL (32) and e-dragon (33).

Figure 2.

QSAR model page of TTD.

Figure 3.

The page of the QSAR models for a particular chemical class against a specific target in TTD.

MULTI-TARGET AGENTS

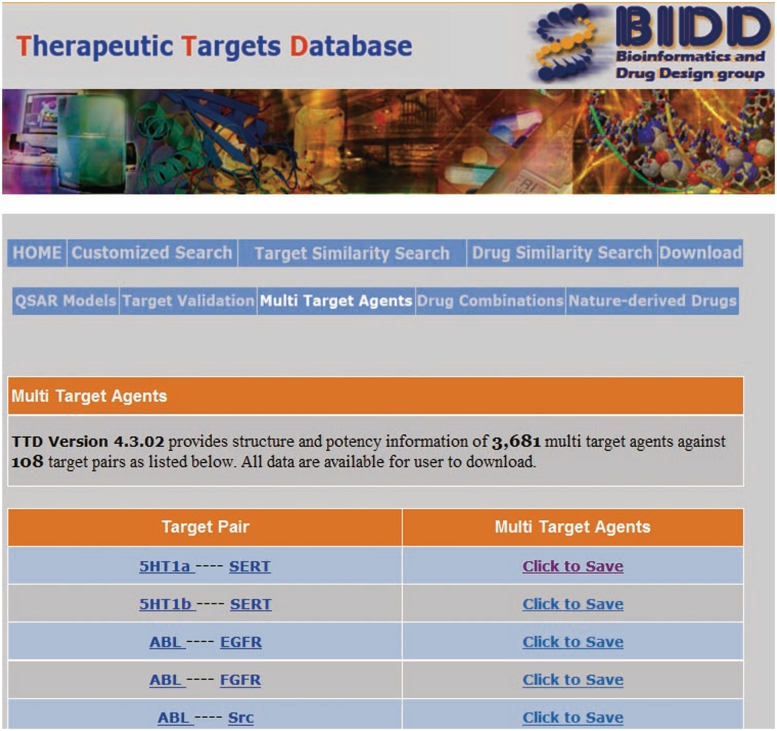

Therapeutic agents directed at an individual target frequently show reduced efficacies, undesired safety profiles and drug resistances due to network robustness, redundancy, cross-talk, compensatory and neutralizing actions, anti-target and counter-target activities (34–36). Multi-target agents directed at selected multiple targets have been increasingly explored for enhanced therapeutic efficacies, improved safety profiles and reduced resistance activities by simultaneously modulating the activity of a primary target and the counteractive elements (3,37,38). In addition to the multi-target agents we have collected in our previous studies of multi-target drugs (20,21), we further searched PubMed (28) using such keywords as ‘multi-target’, ‘dual target’ and ‘dual inhibitor’. Multi-target agent against a target pair refers to a compound active against both targets at potency values of ≤20 µM regardless of their possible activities against other targets. The 3D structures of these multi-target agents were generated by using CORINA (39) from the 2D structures manually drawn based on the literature provided structures or the structures found in such chemical databases as BindingDB (40), ChEMBL (41) and PubChem (28). These multi-target agents can be retrieved by clicking the ‘Multi-Target Agents’ field in the TTD home page, which lead to the TTD multi-target agents page wherein a user can download the multi-target agents against a specific target pair from the target pair list (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Multi-target agents page of TTD.

DRUG COMBINATIONS

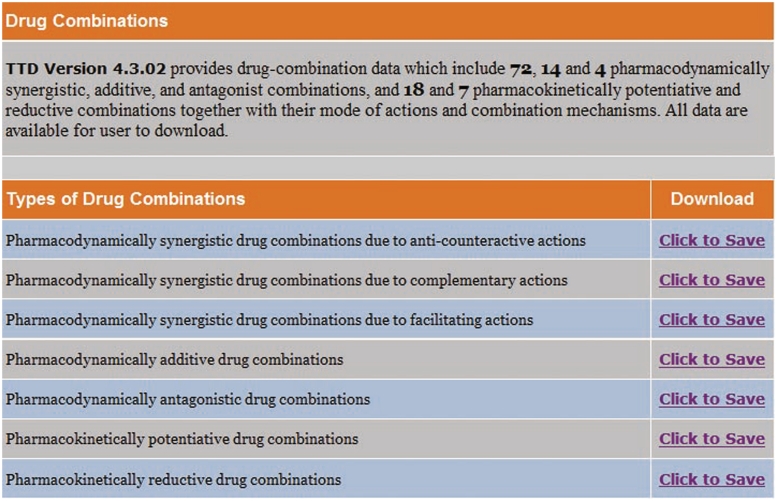

Apart from multi-target agents, drug combinations have also been extensively explored for enhanced therapeutic efficacies, improved safety profiles and reduced resistance activities (12,38,42). When two drugs produce the same broad therapeutic effect, their combination collectively produces the same effects of various magnitudes in contrast to the summed response of the individual drugs. A drug combination is pharmacodynamically synergistic, additive or antagonistic if the effect is greater than, equal to or less than the summed response of the individual drugs (43). Drug combinations may also produce pharmacokinetically potentiative or reductive effects such that the therapeutic activity of one drug is enhanced or reduced by another drug via regulation of the first drug's ADME (43). In our earlier studies of drug combinations (12), we have searched PubMed (28) to select those literature-reported drug combinations evaluated by rigorous combination analysis methods and with known molecular mechanism of combination retrievable from PubMed by using combinations of the keywords ‘drug combination’, ‘drug interaction’, ‘multi-drug’, ‘additive’, ‘antagonism’, ‘antagonistic’, ‘infra-additive’, ‘potentiated’, ‘potentiative’, ‘potentiation’, ‘reductive’, ‘supra-additive’, ‘synergism’, ‘synergistic’ and ‘synergy’.

All major classes of drug combinations can be further divided into groups of specific action types (12). Pharmacodynamically synergistic drug combinations can be divided into three groups: each one with anti-counteractive, complementary and facilitating actions, respectively. Anti-counteractive actions reduce network's counteractive activities against a drug's therapeutic effect. Complementary actions positively regulate a target or process by interactions with multiple target/pathway sites, different target subtypes and states, and competing mechanisms (3). Facilitating actions are secondary actions of one drug in enhancing the activity or level of another drug. Pharmacodynamically additive drug combinations can be divided into two groups, one with equivalent or overlapping actions, and the other with independent actions of the drugs involved. Pharmacodynamically antagonistic drug combinations can also be divided into two groups, one with mutually interfering actions at the same target, another with mutually counter-active actions at different targets of related pathways that regulate the same target. Pharmacokinetically potentiative drug combinations can be divided into three groups, each one with positive modulation of drug transport or permeation, drug distribution or localization and drug metabolism, respectively. Pharmacokinetically reductive drug combinations can be divided into three groups, each one with negative modulation of drug transport or permeation, drug distribution or localization and drug metabolism, respectively. These drug combinations and their combination mechanisms can be accessed by clicking the ‘Drug Combinations’ field in the TTD home page, which lead to the TTD drug combinations page wherein a user can download the relevant drug combination data from the drug combination type list (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Drug combination page of TTD.

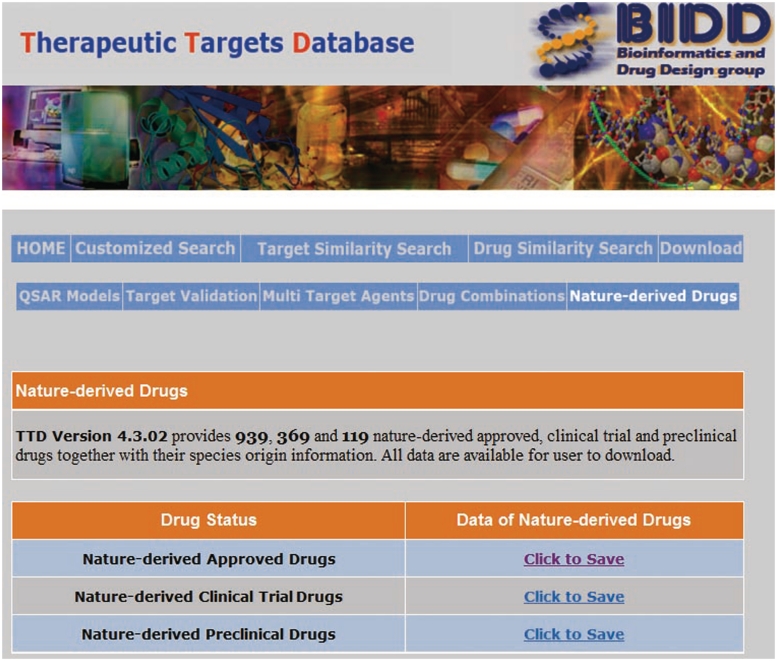

NATURAL PRODUCT-DERIVED DRUGS

Many of the approved and clinical trial drugs are derived from natural products (44,45). Although drug discovery focus has been shifted from natural products to synthetic chemicals, natural product-derived drugs still constitute a substantial percentage of recently approved drugs (26% of the 46 FDA approved new molecular entities in 2009–2010 are natural product derived) (13). There is a renewed interest in natural products as sources for drug discovery (46). Knowledge of the natural sources of drugs, the species origins of the natural product-derived approved, clinical trial and pre-clinical drugs, are highly useful for facilitating the search and development of new drug leads. In our earlier analysis of the species origins of natural product-derived drugs, we have collected the species origins and species families of natural product-derived approved, clinical trial and pre-clinical drugs (13).

The species-origins of these drugs have been identified as follows. First the literature-reported approved drugs (44), clinical trial (45,47) and pre-clinical (13) drugs of natural origin were evaluated with respect to the drugs in our TTD database (15) to check their current approval or clinical trial status. Then the species-origin of every drug was searched from books, review and regular articles by using combinations of such keywords as drug name and alternative names, species, natural product and nature. The species-origin of a drug is confirmed if it is specifically mentioned that it ‘originates from’, ‘derived from’, ‘isolated from’ or ‘comes from’ a species or species-group (e.g. genus or family). For drugs of semi-synthetic derivatives, mimics and peptidomimetics, their parent natural product leads were first searched followed by the search of host species as described above. The corresponding species-families of the host-species of these drugs as well as all the known species-families in the nature are from the NCBI taxonomy database (28). These natural product-derived drugs and their species origins and families can be retrieved by clicking the ‘Nature-Derived Drugs’ field in the TTD home page, which lead to the TTD natural product-derived drugs page wherein a user can download the relevant data from the drug status list (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Natural product-derived drugs page of TTD.

REMARKS

A goal in updating TTD is to make it into a more useful target and drug discovery resource in complement to other related databases. Continuous efforts will be made to provide the latest and comprehensive information about the primary (efficacy) targets of approved, clinical trial, pre-clinical and experimental drugs and other relevant data for these drugs. Intensive efforts in drug and target discovery have led to and will continue to enable the generation of new information, knowledge and models from existing targets (18), drugs (9,29,48,49), multi-target drugs (20) and drug combinations (12,38,42). Drug discovery efforts have benefited and are continuing to be benefited from the exploration of multiple lead sources including synthetic chemicals (1–3), biologics (50–53) and natural products (13,44,45). Inclusion of these information, knowledge and models into TTD and other databases will further enable these databases to better serve the drug discovery and research communities in their efforts for discovering new targets and new drugs from different sources.

FUNDING

Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China and the Singapore Academic Research Fund R-148-000-141-750 and R-148-000-141-646. Funding for open access charge: Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ohlstein EH, Ruffolo RR, Jr, Elliott JD. Drug discovery in the next millennium. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000;40:177–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zambrowicz BP, Sands AT. Knockouts model the 100 best-selling drugs–will they model the next 100? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:38–51. doi: 10.1038/nrd987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keith CT, Borisy AA, Stockwell BR. Multicomponent therapeutics for networked systems. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrd1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewitt DJ, Hargreaves RJ, Curtis SP, Michelson D. Challenges in analgesic drug development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;86:447–450. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng C, Han L, Yap CW, Xie B, Chen Y. Progress and problems in the exploration of therapeutic targets. Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11:412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rask-Andersen M, Almen MS, Schioth HB. Trends in the exploitation of novel drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:579–590. doi: 10.1038/nrd3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duarte CD, Barreiro EJ, Fraga CA. Privileged structures: a useful concept for the rational design of new lead drug candidates. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2007;7:1108–1119. doi: 10.2174/138955707782331722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao H. Scaffold selection and scaffold hopping in lead generation: a medicinal chemistry perspective. Drug Discov. Today. 2007;12:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sprous DG, Palmer RK, Swanson JT, Lawless M. QSAR in the pharmaceutical research setting: QSAR models for broad, large problems. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010;10:619–637. doi: 10.2174/156802610791111506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youdim MB, Buccafusco JJ. Multi-functional drugs for various CNS targets in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;26:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilanges B, Torbett N, Vanhaesebroeck B. Killing two kinase families with one stone. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:648–649. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1108-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia J, Zhu F, Ma X, Cao Z, Li Y, Chen YZ. Mechanisms of drug combinations: interaction and network perspectives. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8:111–128. doi: 10.1038/nrd2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu F, Qin C, Tao L, Liu X, Shi Z, Ma X, Jia J, Tan Y, Cui C, Lin J, et al. Clustered patterns of species origins of nature-derived drugs and clues for future bioprospecting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:12943–12948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107336108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Ji ZL, Chen YZ. TTD: therapeutic target database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:412–415. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu F, Han B, Kumar P, Liu X, Ma X, Wei X, Huang L, Guo Y, Han L, Zheng C, et al. Update of TTD: therapeutic target database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D787–D791. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knox C, Law V, Jewison T, Liu P, Ly S, Frolkis A, Pon A, Banco K, Mak C, Neveu V, et al. DrugBank 3.0: a comprehensive resource for 'omics' research on drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D1035–D1041. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng CJ, Han LY, Yap CW, Ji ZL, Cao ZW, Chen YZ. Therapeutic targets: progress of their exploration and investigation of their characteristics. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:259–279. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu F, Han L, Zheng C, Xie B, Tammi MT, Yang S, Wei Y, Chen Y. What are next generation innovative therapeutic targets? Clues from genetic, structural, physicochemical, and systems profiles of successful targets. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;330:304–315. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.149955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knowles J, Gromo G. A guide to drug discovery: target selection in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:63–69. doi: 10.1038/nrd986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma XH, Shi Z, Tan C, Jiang Y, Go ML, Low BC, Chen YZ. In-silico approaches to multi-target drug discovery: computer aided multi-target drug design, multi-target virtual screening. Pharm. Res. 2010;27:739–749. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma XH, Wang R, Tan CY, Jiang YY, Lu T, Rao HB, Li XY, Go ML, Low BC, Chen YZ. Virtual screening of selective multitarget kinase inhibitors by combinatorial support vector machines. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7:1545–1560. doi: 10.1021/mp100179t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. How many drug targets are there? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:993–996. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinmetz KL, Spack EG. The basics of preclinical drug development for neurodegenerative disease indications. BMC Neurol. 2009;9(Suppl. 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindsay MA. Target discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nrd1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Tumour microenvironment opinion: validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:227–239. doi: 10.1038/nrc1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vidalin O, Muslmani M, Estienne C, Echchakir H, Abina AM. In vivo target validation using gene invalidation, RNA interference and protein functional knockout models: it is the time to combine. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2009;9:669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stumpf WE. Memo to the FDA and ICH: appeal for in vivo drug target identification and target pharmacokinetics Recommendations for improved procedures and requirements. Drug Discov. Today. 2007;12:594–598. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bolton E, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, DiCuccio M, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D38–D51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mittal RR, McKinnon RA, Sorich MJ. Comparison data sets for benchmarking QSAR methodologies in lead optimization. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009;49:1810–1820. doi: 10.1021/ci900117m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dudek AZ, Arodz T, Galvez J. Computational methods in developing quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR): a review. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2006;9:213–228. doi: 10.2174/138620706776055539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yap CW, Li H, Ji ZL, Chen YZ. Regression methods for developing QSAR and QSPR models to predict compounds of specific pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic and toxicological properties. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2007;7:1097–1107. doi: 10.2174/138955707782331696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li ZR, Han LY, Xue Y, Yap CW, Li H, Jiang L, Chen YZ. MODEL-molecular descriptor lab: a web-based server for computing structural and physicochemical features of compounds. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007;97:389–396. doi: 10.1002/bit.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tetko IV, Gasteiger J, Todeschini R, Mauri A, Livingstone D, Ertl P, Palyulin VA, Radchenko EV, Zefirov NS, Makarenko AS, et al. Virtual computational chemistry laboratory–design and description. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2005;19:453–463. doi: 10.1007/s10822-005-8694-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pilpel Y, Sudarsanam P, Church GM. Identifying regulatory networks by combinatorial analysis of promoter elements. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:153–159. doi: 10.1038/ng724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sergina NV, Rausch M, Wang D, Blair J, Hann B, Shokat KM, Moasser MM. Escape from HER-family tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy by the kinase-inactive HER3. Nature. 2007;445:437–441. doi: 10.1038/nature05474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:227–239. doi: 10.1038/nrc1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smalley KS, Haass NK, Brafford PA, Lioni M, Flaherty KT, Herlyn M. Multiple signaling pathways must be targeted to overcome drug resistance in cell lines derived from melanoma metastases. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1136–1144. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larder BA, Kemp SD, Harrigan PR. Potential mechanism for sustained antiretroviral efficacy of AZT-3TC combination therapy. Science. 1995;269:696–699. doi: 10.1126/science.7542804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadowski J, Gasteiger J, Klebe G. Comparison of automatic three-dimensional model builders using 639 x-ray structures. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1994;34:1000–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu T, Lin Y, Wen X, Jorissen RN, Gilson MK. BindingDB: a web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D198–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Overington J. ChEMBL. An interview with John Overington, team leader, chemogenomics at the european bioinformatics institute outstation of the european molecular biology laboratory (EMBL-EBI). Interview by Wendy A. Warr. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2009;23:195–198. doi: 10.1007/s10822-009-9260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zimmermann GR, Lehar J, Keith CT. Multi-target therapeutics: when the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Drug Discov. Today. 2007;12:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:621–681. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butler MS. Natural products to drugs: natural product-derived compounds in clinical trials. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008;25:475–516. doi: 10.1039/b514294f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li JW, Vederas JC. Drug discovery and natural products: end of an era or an endless frontier? Science. 2009;325:161–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1168243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saklani A, Kutty SK. Plant-derived compounds in clinical trials. Drug Discov. Today. 2008;13:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vistoli G, Pedretti A, Testa B. Assessing drug-likeness–what are we missing? Drug Discov. Today. 2008;13:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saladin PM, Zhang BD, Reichert JM. Current trends in the clinical development of peptide therapeutics. IDrugs. 2009;12:779–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woodcock J, Griffin J, Behrman R, Cherney B, Crescenzi T, Fraser B, Hixon D, Joneckis C, Kozlowski S, Rosenberg A, et al. The FDA's assessment of follow-on protein products: a historical perspective. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:437–442. doi: 10.1038/nrd2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nelson AL, Dhimolea E, Reichert JM. Development trends for human monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:767–774. doi: 10.1038/nrd3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melnikova I. RNA-based therapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:863–864. doi: 10.1038/nrd2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]