Abstract

Hemorrhagic fever viruses (HFVs) are a diverse set of over 80 viral species, found in 10 different genera comprising five different families: arena-, bunya-, flavi-, filo- and togaviridae. All these viruses are highly variable and evolve rapidly, making them elusive targets for the immune system and for vaccine and drug design. About 55 000 HFV sequences exist in the public domain today. A central website that provides annotated sequences and analysis tools will be helpful to HFV researchers worldwide. The HFV sequence database collects and stores sequence data and provides a user-friendly search interface and a large number of sequence analysis tools, following the model of the highly regarded and widely used Los Alamos HIV database [Kuiken, C., B. Korber, and R.W. Shafer, HIV sequence databases. AIDS Rev, 2003. 5: p. 52–61]. The database uses an algorithm that aligns each sequence to a species-wide reference sequence. The NCBI RefSeq database [Sayers et al. (2011) Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res., 39, D38–D51.] is used for this; if a reference sequence is not available, a Blast search finds the best candidate. Using this method, sequences in each genus can be retrieved pre-aligned. The HFV website can be accessed via http://hfv.lanl.gov.

INTRODUCTION

The hemorrhagic fever viruses (HFVs) are defined by their pathogenicity rather than by any taxonomical relationships. The group contains viruses from 6 viral families and 10 genera: arena-, hanta-, orthobunya-, nairo,-, phlebo-, flavi-, ebola-, marburg-, henipa- and alphaviruses. (1) All these viruses have relatively small RNA genomes (<20 Kb) and are extraordinarily variable, leading to quasispecies formation (2). This variability necessitates different approaches for sequence analysis. Historically, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been the subject of most quasispecies research, and consequently a large and still growing tool set has been developed. Many of these have been developed by, and made publicly available through, a high-traffic website maintained by the HIV Database and Analysis Project in Los Alamos (http://hiv.lanl.gov). Our new HFV site makes many of these computational tools and techniques available for the study of HFV.

The web-accessible site offers access to a database containing genetic sequences taken from GenBank, and subjected to automated quality control and curation procedures. The associated search interfaces allows easy retrieval and profile-based alignment of genomes and individual genes across species (up to the genus level), as well as geographical analysis. In addition to the stored sequences, a number of unique and versatile analysis tools are available, most developed with an emphasis on quasispecies analysis. Many of the tools rely upon reference sequence-based annotation information about the viral genus or species to facilitate analyses that would require manual curation otherwise.

The HFV database is built on the same framework as the HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (3) databases, and many of the tools are similar, with modifications to accommodate differences in the analysis targets. Scientists who are familiar with the HCV or HIV sites will find it easy to navigate the HFV site. The database offers access to sequences using a flexible, user-friendly search interface that can retrieve aligned sequences, based on (among many others) the genus, genomic region, clade, gene name and location and reference information.

METHODS

The purpose and design of the database

The HFV database aims to be a resource for scientists working on HFV genetics, evolution, variability and vaccine and drug design. The database is managed by biologists with extensive experience in sequence analysis, assisted by bioinformaticians and computer scientists. The backbone of the database is formed by the HFV sequences deposited in GenBank. New sequences are downloaded weekly, and the available ancillary information is extracted from the GenBank records. This information is gleaned not only from designated fields but also from text mining, and may include country, sampling year, isolate names, host species, etc.

Many of the site's capabilities and tools are supported by reference sequences (one per species). These are mostly obtained from NCBI's RefSeq database (4), but in cases where RefSeq does not contain a good reference sequence (e.g. a new or unclassified virus), an automated Blast search selects an optimal reference sequence. Reference sequences and their annotation are used to direct the location of genes and coding regions, to standardize numbering of regions and epitopes and form the basis of all alignment models and frame corrections. The database also contains (synthetic) reference sequences for each genus; these are used for on-the-fly alignments, which are done on a per-genus (and segment) basis.

Searching the database

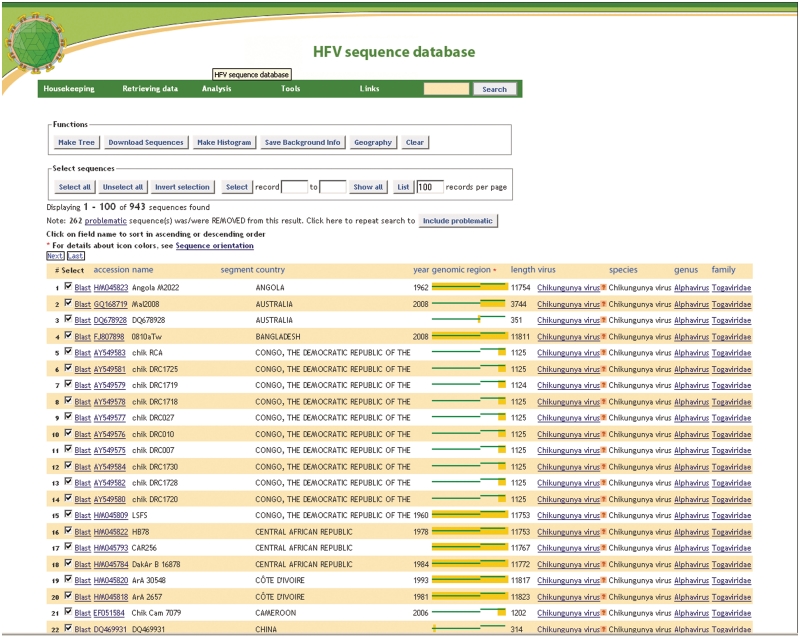

The information in the database can be accessed via two search interfaces. One is a versatile but user-friendly search interface that allows searches on some 30 different fields, and lets the user automatically exclude bad-quality sequences. The search results can be sorted and selected in various ways, and include an icon for each sequence that shows at a glance how long each sequence is and where in the genome it is located (Figure 1). This interface also offers access to a number of analysis and visualization methods.

Figure 1.

Tabular results page from the regular search interface, including functions available for the search results (phylogenetic tree, geographical information, etc.), ancillary information about sample background, genome coverage and taxonomic relations of the viral species.

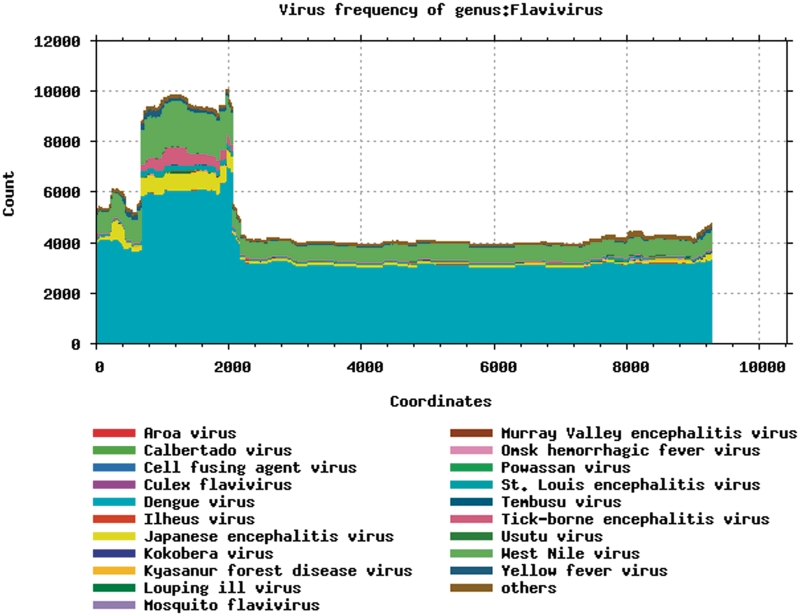

A graphical overview showing which regions and which species are included in the entire set of retrieved sequences can be generated (Figure 2). An important feature is the ability to search by genomic region. It allows the user to locate all sequences in the database that span a region, and opt to include or exclude sequences that are located in that region but do not cover it completely. Retrieved sequences and the associated annotation can be downloaded as an alignment which will usually be codon-aligned, so that it can be translated immediately; or alternatively, search results can also be downloaded as translated amino acids in any reading frame. The retrieved background information can also be downloaded as a tab-delimited file.

Figure 2.

Distribution of genomic sequence information over the flavivirus model genome, by viral species. For dengue, approximately 3500 complete genomes are available; the most densely sequenced region is nucleotides 800–2000, roughly corresponding to the envelope protein.

The ‘advanced search interface’ dynamically reads the schema of the database and generates a graphical overview of the tables and fields. This overview can be used to generate a custom-made search interface containing user-selected fields. This interface offers read access to the entire database, but some of the ‘overhead’ that the regular interface performs automatically, such as including the proper foreign key fields, must be done by hand in the advanced interface.

Internal workings

All sequences are downloaded from GenBank as XML files, which are parsed and searched for additional information. The basis for further processing is currently the NCBI taxonomical classification. For each genus or sub-genus and each segment, an initial alignment was created based on all sequences in that category that were available in the NCBI RefSeq database. These alignments were used to create a model using HMMer2.0 (5). The resulting model was then used to align all sequences in that category.

The resulting aligned sequences are stored in the database, using a storage algorithm described previously (6) that keeps track of both the gaps inserted into the sequence relative to the model, and into the model relative to the sequence. By combining these two sets of gaps, the original aligned sequence can be reconstructed. This procedure is repeated for all sequences that the user wants to download. Finally, columns containing only gaps are removed, and the resulting alignment can be used for further analysis. A similar process is used to align a user sequence set to the provided reference alignments, for example to use in making phylogenetic trees and graphical SNP displays.

The database still contains some 5000 sequences (10% of the total) that are not classified and do not have a reference sequences. These sequences are stored and annotated as far as possible, and they can still be retrieved, but much of the additional functionality is not available.

Sequence orientation and alignment

The method used to internally align the sequences to a genus-level central alignment profile is based on each sequence's taxonomical classification. However, in the use of the database we found that many sequences are not classified, or classified only to the family level. Those sequences are now provisionally assigned a reference sequence based on a simple Blast search that identifies the closest profile. A consequence of the method used is that only sequences in, or resembling, the same genus can be aligned. However, aligning viral sequences at the genus level without a good model is not trivial, and this alignment is a big improvement.

Quite a few viral sequences in GenBank are in reverse-complement orientation, and in some cases the ‘correct’ orientation is not easy to determine from the sequence itself. They are stored as-is, but the correct orientation of all sequences is automatically determined relative to the alignment model, and re-reversed upon download when needed, so they will be in the same orientation. The search output displays the location as well as the orientation of each sequence relative to the species reference sequence. However, some adjustments were to be made for the reference sequences, which can also be in the reverse orientation. The database deals with these sequences separately, and the orientation of both the sequence relative to the reference sequence, and of the reference sequence relative to the alignment profile is displayed.

Quality control and annotation

Sequence annotation plays an increasingly important role in the analysis of the data. The HFV database has designed and implemented several methods to better handle the available annotation and allow it to be re-used for annotation of new sequences.

To harvest the annotation from existing reference sequences, a script has been developed that retrieves the features and values of each reference sequence for each ontological category, such as gene, coding sequence (CDS), mature peptide, etc. This annotation includes the start and stop location for each element. This information is used for many different tools, including Genome Mapper and HFVAlign. It will also be applied in a new tool that was recently made available, that allows users to submit sequences to GenBank and annotate them using similarity to existing sequences and their annotation. In most cases, sequences and annotation are matched based on their taxonomical relationships, but in cases where taxonomical links are not available, a simple Blast search is used to find a matching reference sequence, if one exists.

Several forms of quality control and error checking are included in the database setup. The genomic location of each sequence is recorded upon storage, and sequences in reverse-complement orientation are flagged; they are re-reversed for use when appropriate. Sequences that are not assigned to a species and are too divergent to be aligned will be excluded from downloaded alignments. Patent and synthetic sequences, as well as those with >10% N’s, are also excluded by default, although users can choose to include them.

RESULTS

Data retrieval

The following types of data are available:

Published sequences, with enhanced annotation and quality control.

Manually curated codon alignments for each genus and segment; closely related sequences are removed.

Reference alignments, which contain only the reference sequences for each species, and can be used as background sequences in phylogenetic trees.

Background information (e.g. sampling year, publication information, sampling country and region).

The output of the standard search interface provides a wealth of information about each sequence in table format, including its location and orientation relative to the reference sequence (Figure 1). It also provides cumulative information about the retrieved set, such as its geographical distribution and the coverage of the genera by sequences in each. Sequences and background information can be downloaded in different formats, with standard or user-defined sequence labels.

Data analysis and visualization

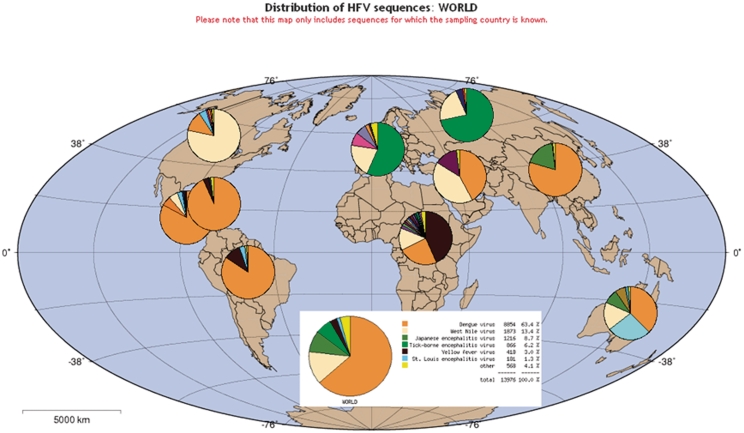

Figure 3 shows output from the ‘Geography tool’, which can be used to plot frequencies of the different species stored in the database as a function of their geographical origin. This tool can be very useful to get a general idea of which viruses have been found in which countries, as well as the density of sampling in different regions of the world.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of all sequences with geographical origin information in the Flavivirus genus in the HFV database.

‘Sequence Locator’ is a program that finds the coordinates of an input sequence relative to the reference strain. This program can be used as a means to standardize primer and epitope numbering, and quickly shows the user the location of an unknown HFV sequence fragment. It provides the amino acid translation in the correct frame if a nucleotide sequence was submitted, and aligns the amino acid sequence against the reference nucleotide sequence if the input is an amino acid sequence. Sequence locator can also be used for reverse-complement sequences.

The database contains many other tools for data analysis, and new ones are still being added, frequently developed for the analysis of HIV and HCV, which are both also quasispecies-forming viruses. We briefly mention a few:

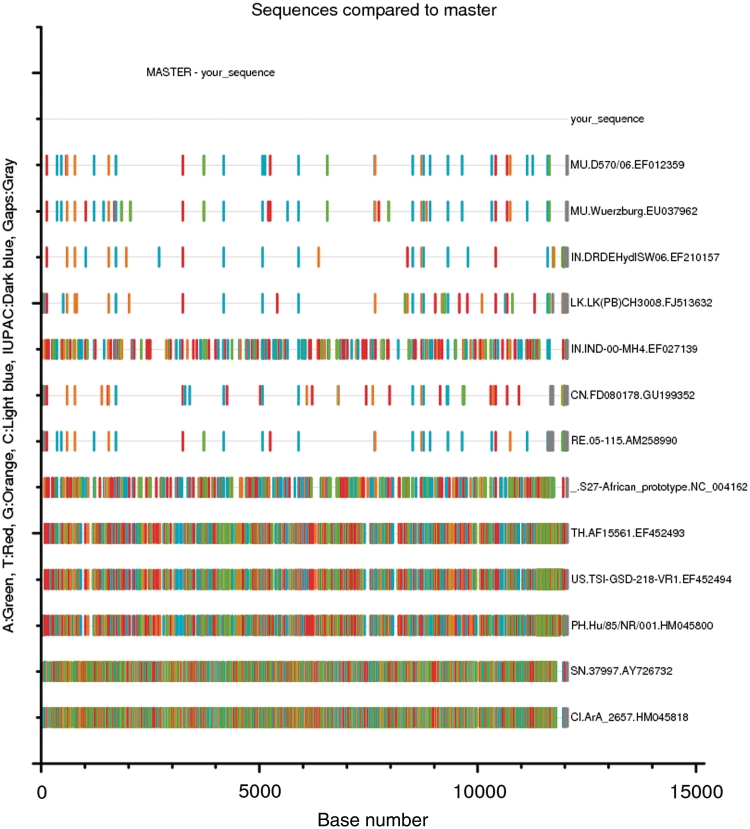

‘Highlighter’ (Figure 4) shows all mutations (SNPs) in a sequence alignment relative to a reference sequence, automatically scales the image to the size of the alignment. It can handle nucleotides and amino acids, silent/non-silent changes, and transitions/transversions.

‘Entropy’ displays the entropy of a sequence alignment, or the difference in entropy between two alignments; statistical tests are available.

‘Findmodel’ is a web implementation of Modeltest (7), a program that determines the best evolutionary model for an alignment.

‘HFValign’ will find the best reference sequence for a submitted sequence or alignment, align it to the input, and use it to clip out aligned coding sequences. CDSs can be translated using different IUPAC code treatments.

‘Phyloplace’, a classification tool, takes a user input sequence and background alignment, and uses two algorithms to determine if the user sequence falls within or outside a defined clade (8).

‘Protein Feature Accent’, a protein viewer that can highlight variable regions in the protein based on submitted alignment.

Figure 4.

Output from Highlighter tool, showing mutations Single Nuleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) relative to a reference or ‘master’ sequence; in this case, a user input sequence of the species Chikungunya.

Future enhancements

The first tool to be added will probably be a GenBank sequence submission tool, which uses reference sequence annotation to find and number coding sequences, mature proteins and functional regions. Other tools that are being developed are:

a tool to store, manipulate and analyze ultra-deep sequencing data;

a workflow management system;

better integration of genome browsing and GFF3 format;

pattern searching and alignment in protein space; and

integrated gene and protein labeling, so a search for ‘RDRP’ will retrieve the RDRP from all viruses, regardless of its location.

For several of these functions, the HFV database staff is collaborating closely with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), the International Committee for the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) (9), the National Center for Biomedical Ontology (NBCO) and the Viral Pathogen Research (ViPR) database (http://www.viprbrc.org).

Work is also currently underway to create a more refined de novo annotation system that is based on a self-referential set of alignments. Very briefly, all database sequences are searched for highly similar sequence sets. These sequences are aligned and converted into profiles, which then are used to expand the sets. Genes, coding regions and other functional domains in these self-expanding profiles can be manually annotated, and then used to automatically find the same regions in new sequences. Results from this work will be made available later in 2012.

FUNDING

Transformational Medical Technologies Initiative (TMTI) under Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) [contract #HDTRA B084498I]. Funding for open access charge: DTRA.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Bette Korber and our colleagues at the HIV databases for their generous help and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seligman SJ. Constancy and diversity in the flavivirus fusion peptide. Virol. J. 2008;5:27. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gowen BB, Holbrook MR. Animal models of highly pathogenic RNA viral infections: hemorrhagic fever viruses. Antiviral Res. 2008;78:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuiken C, Hraber P, Thurmond J, Yusim K. The hepatitis C sequence database in Los Alamos. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D512–D516. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, DiCuccio M, Edgar R, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D38–D51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eddy SR. Multiple alignment using hidden Markov models. ISMB. 1995;3:114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaschen B, Kuiken C, Korber B, Foley B. Retrieval and on-the-fly alignment of sequence fragments from the HIV database. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:415–418. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.5.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hraber P, Kuiken C, Waugh M, Geer S, Bruno WJ, Leitner T. Classification of hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus-1 sequences with the branching index. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:2098–2107. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83657-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carstens EB. Working virologists and the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) Arch. Virol. 2001;146:2493–2495. doi: 10.1007/s007050170019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]