Abstract

Targeting cancer stem cells is of paramount importance in successfully preventing cancer relapse. Recently, in silico screening of public gene-expression datasets identified cyclooxygenase-derived cyclopentenone prostaglandins (CyPGs) as likely agents to target malignant stem cells. We show here that Δ12-PGJ3, a novel and naturally produced CyPG from the dietary fish-oil ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5) alleviates the development of leukemia in 2 well-studied murine models of leukemia. IP administration of Δ12-PGJ3 to mice infected with Friend erythroleukemia virus or those expressing the chronic myelogenous leukemia oncoprotein BCR-ABL in the hematopoietic stem cell pool completely restored normal hematologic parameters, splenic histology, and enhanced survival. More importantly, Δ12-PGJ3 selectively targeted leukemia stem cells (LSCs) for apoptosis in the spleen and BM. This treatment completely eradicated LSCs in vivo, as demonstrated by the inability of donor cells from treated mice to cause leukemia in secondary transplantations. Given the potency of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid–derived CyPGs and the well-known refractoriness of LSCs to currently used clinical agents, Δ12-PGJ3 may represent a new chemotherapeutic for leukemia that targets LSCs.

Introduction

In addition to its well-known anti-inflammatory benefits, particularly in cardiovascular and other inflammatory diseases,1–4 eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), a long-chain ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (n-3 PUFA) of marine origin, is associated with cancer prevention. Studies have demonstrated that cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), but not COX-1, either preferentially metabolizes EPA to a novel set of autocoids called resolvins5 or it forms prostaglandin H3 (PGH3).6 PGH3, much like its n-6 counterpart, arachidonic acid (ARA)–derived PGH2, is metabolized to the “3-series” PG end products PGD3, PGE3, PGF3α, PGI3, and TxA3 by specific PG synthases.6 However, unlike the 2-series PGs, the 3-series PGs reportedly have anti-inflammatory properties even though they exhibit comparable affinity toward the cell-surface PG receptors DP, EP1-3, and FP as their 2-series counterparts.6 Studies by Wada et al6 also suggest that the health benefits of 3-series prostanoids possibly arise not from its ability to compete with the 2-series PGs, but most likely from their metabolites. In this context, the metabolism of EPA-derived cyclopentenone PGs (CyPGs) in the form of PGJ3, Δ12-PGJ3, and 15d-PGJ3 (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) is thus far unknown. We speculate that the metabolism of EPA to PGD3-derived CyPGs may follow an identical pathway of metabolism, as in the case of ARA-derived PGD2 by hematopoietic-PGD synthase (H-PGDS) or lipocalin-PGD synthase (L-PGDS) PGD3.7 As demonstrated earlier by Fitzpatrick et al with PGD2,8,9 it is very likely that EPA-derived PGD3 undergoes nonenzymatic dehydration to form PGJ3, followed by an isomerization to Δ12-PGJ3 and a second dehydration to 15d-PGJ3 in an aqueous environment.

15d-Prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) inhibits anti-apoptotic NF-κB, while activating NF-E2–related factor 2 (Nrf-2) and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ) to mediate apoptosis and anti-inflammation.10–12 The proapoptotic activity of 15d-PGJ2 has been suggested to potentially lead to the eradication of acute myelogenous leukemia and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) stem cells based on an in silico study using cDNA microarray gene-expression profiles available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database.13 The cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a small dormant population, whereas the “bulk” cancer cells that exhibit limited proliferative potential are targeted by current cancer therapeutics. Such refractory CSCs begin to self-renew and differentiate into malignant cells causing a recurrence of the disease.14 Therefore, selective targeting of CSCs is potentially a highly effective treatment for cancer. To this end, we have investigated the endogenous formation of Δ12-PGJ3 from EPA and further examined the ability of this novel n-3 PUFA metabolite to target leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in 2 well-studied models of leukemia, Friend virus (FV)–induced erythroleukemia,15 and a well-established model for inducing CML in mice, which uses BCR-ABL–IRES-GFP retrovirus,16–19 where transplantation of transduced hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) into mice results in pathology similar to the chronic phase of CML. FV induces leukemia by activating the bone morphogenetic protein-4 (BMP4)–dependent stress erythropoiesis pathway, which leads to a rapid amplification of target cells and acute disease.20 Recent studies have shown that stress erythropoiesis uses a self-renewing population of stress erythroid progenitors.21 Infection of this population with FV led to the development of LSCs (S.H. and R.F.P., unpublished data). The FV LSCs are not Lin− because they express low levels of Ter119 in addition to Kit, Sca1, and CD71, similar to what was observed for self-renewing stress erythroid progenitors.21 We demonstrate that Δ12-PGJ3 administration (at doses as low as 0.6 μg/mouse/d) to FV-infected and BCR-ABL+–transduced HSC (hereafter referred to as BCR-ABL+ LSC)–transplanted mice completely ablates leukemia, restores hematologic parameters, and eradicates LSCs via the activation of Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)/p53 pathway of apoptosis in these cells.

Methods

Cell culture

Murine erythroleukemia (MEL) cells (a gift from Dr Ross Hardison, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA) were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. To examine the production of 3-series PGs, BALB/c-derived RAW264.7 macrophage-like cells (from the ATCC) were cultured in DMEM containing 5% FBS, 250nM sodium selenite, and 50μM EPA (as BSA conjugate) for 72 hours, followed by stimulation with Escherichia coli endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS; serotype 0111B4; 50 ng/mL) for 30 minutes. The cells were then cultured in fresh DMEM for an additional 24-144 hours. Cells cultured with cell culture–grade fatty acid–free BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) served as controls. Culture medium was withdrawn at various times and analyzed for 3-series PGs, as described in “Preparation, isolation, and spectroscopic characterization of PGD3 metabolites.” Total RNA was isolated from cells or tissues using TRIzol reagent as per the instructions of the supplier (Invitrogen) and cDNA was prepared using a high-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase kit (Applied Biosystems). Semiquantitative RT-PCR for p53 and β-actin was performed with primers as described in supplemental Methods. Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extracts of LSCs were prepared using methods described previously.22

Preparation, isolation, and spectroscopic characterization of PGD3 metabolites

PGD3 (Cayman Chemicals) was incubated with 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.9% NaCl at a final concentration of 100 μg/mL with shaking at 37°C for various periods (24-144 hours). The reaction products and those from the cell-culture medium supernatants were purified by HPLC and analyzed by UV and MS as described in supplemental Methods.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis of LSCs was performed using annexin V as described in supplemental Methods.

Isolation and identification of LSCs

LSCs were isolated by FACS. For the FV model, spleen cells were labeled with anti-Kit, Sca1 (BioLegend) and M34 Abs. M34 is an mAb that recognizes the envelope protein of SFFV23 and was used as described previously.20 Similarly, in the BCR-ABL model, BM cells from C57BL/6 mice pretreated with 5-fluorouracil (150 mg/kg) were harvested and infected with mouse stem cell virus–green fluorescent protein (MSCV-GFP) control retrovirus or MSCV-IRES-GFP-retrovirus (MIGR)–BCR-ABL retrovirus overnight in IMDM containing 5% FCS and supplemented with 2.5 ng/mL of IL-3 and 15 ng/mL of SCF (R&D Systems). Transduced cells (0.5 × 106) were transplanted by retro-orbital injection into C57BL/6 recipient mice that were preconditioned with 950 rads of irradiation. To increase the number of CML and control mice, 17 days after transplantation, GFP+ spleen cells were isolated by FACS using Kit+Sca1+Lin−GFP+ cells from the BM or spleen and used for all of the ex vivo studies.

FV-induced erythroleukemia and production of FV-LSCs

BALB/c mice were infected with FV as described previously.20,21 On day 14 after infection, spleens were isolated and a single cell suspension of spleen cells was generated. The cells were filtered through a 70-μm sterile filter and flow-through cells were resuspended in RBC lysis buffer and then centrifuged. As indicated above, LSCs (M34+Kit+Sca1+) were cultured in Methocult medium M3334 (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 200 ng/mL of Sonic Hedgehog (Shh), 15 ng/mL of bone morphogenetic protein-4 (BMP4; both from R&D Systems), and 50 ng/mL of stem cell factor (SCF; Peprotech). For CFU-FV assays, cells were plated in methylcellulose medium containing FCS, but lacking added growth factors as described previously.24

Transplantation of FV-LSCs into BALB/c-Stk−/− mice

FV-LSCs were generated as described in “Isolation and identification of LSCs.” FV-LSCs (2.5 × 105) were transplanted into BALB/c-Stk−/− mice by retro-orbital injection. Six weeks after transplantation the mice were treated with CyPGs or vehicle control.

Induction of CML using MIGR–BCR-ABL retrovirus

MIGR–BCR-ABL and control MSCV-GFP retroviruses were a gift from Dr Warren Pear (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). Viral stocks were generated in HEK293 cells as described previously.25 C57BL/6 mice were treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; 150 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) to enrich for cycling HSCs. On day 4 after treatment, BM cells were infected, followed by transplantation of GFP+ cells into recipient mice. Two weeks after transplantation, mice were treated as indicated with CyPGs and vehicle control. For ex vivo experiments, Kit+Sca1+Lin−GFP+ cells were isolated from the BM or spleens of transplanted mice by FACS. The sorted cells were cultured in Methocult medium M3334 (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with Shh, SCF, and BMP4, and treated with the indicated CyPGs and vehicle controls for the indicated time periods. To demonstrate the effect of Δ12-PGJ3 on normal hematopoietic progenitors, HSCs isolated from the BM of C57BL/6 mice were cultured in methylcellulose medium (1 × 106 cells/mL/well) containing erythropoietin (3 U/mL), SCF, IL-3, and BMP4 in the presence or absence of Δ12-PGJ3 (25nM). The hematopoietic colonies (measured in colony-forming cells in culture [CFCs]) were scored.

Secondary transplantations to test for residual LSCs after treatment with Δ12-PGJ3

For CML, B6.SJLPtprca Pep3b/BoyJ (CD45.1+) mice were treated with 5-FU and BM cells enriched in cycling HSCs were isolated and then infected with MIGR–BCR-ABL virus or control MSCV-GFP virus. The cells were transplanted into C57BL/6 (CD45.2) recipient mice, and the mice were treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. Two weeks after treatment, spleen cells were isolated and transplanted into irradiated secondary C57BL/6 (CD45.2) recipients. Two weeks after secondary transplantation, mice were analyzed for WBC counts, splenomegaly, and the presence of GFP+ or CD45.1 donor cells in the BM and spleen by flow cytometry. Secondary transplantations were also done with FV-infected mice treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. BALB/c mice were infected with FV. The mice were treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. Two weeks after treatment, spleen cells were isolated from FV-infected mice and transplanted into BALB/c-Stk−/− recipient mice (1 × 105 cells per mouse). Five weeks after transplantation, the mice with secondary transplantations were tested for WBC counts, splenomegaly, and presence of M34+Kit+Sca1+ FV-LSCs by flow cytometry.

Treatment of mice with PGs

Mice with FV-induced erythroleukemia or MIGR–BCR-ABL–induced CML were treated with CyPGs as follows. Mice were treated with a daily IP injection of Δ12-PGJ3 (0.01-0.1 mg/kg), 15d-PGJ2 (0.1 mg/kg), or 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 (0.1 mg/kg) for 7 days. All 3 compounds were formulated with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (30% wt/vol; Sigma-Aldrich). All experiments using mice were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of The Pennsylvania State University.

Inhibition of ATM kinase in LSCs

LSCs isolated from FV-infected mice or BCR-ABL+LSCs–transplanted mice were treated with either the ATM-specific inhibitor 2-morpholin-4-yl-6-thianthren-1-yl-pyran-4-one ((MTPO; KU55933; 50nM; Calbiochem) or the ATM/ATR–specific inhibitor (CGK-733; 1μM; Calbiochem), followed by treatment with CyPGs.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as means ± SEM and the differences between groups were analyzed using the Student t test and Prism Version 4 software (GraphPad). The criterion for statistical significance was P < .05.

Results

Endogenous metabolites of EPA

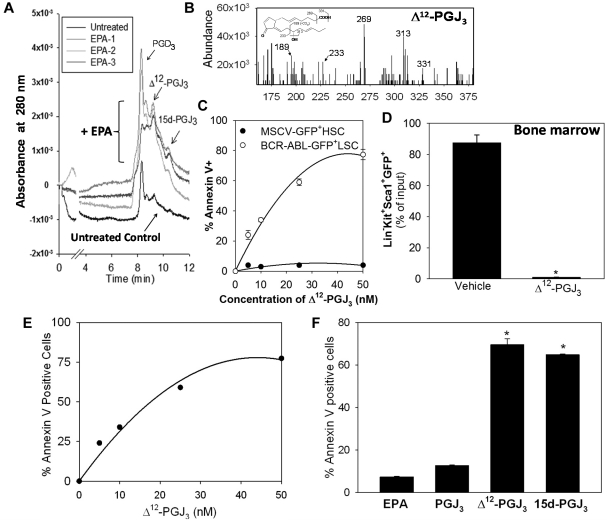

To relate the potent antileukemic effects of EPA-derived CyPGs to their endogenous production, we examined the cellular biosynthesis of PGD3, Δ12-PGJ3 and 15d-PGJ3 in murine macrophage-like cells (RAW264.7) cultured with EPA (50μM). RAW264.7 cells, which express H-PGDS,26 were stimulated with the bacterial endotoxin LPS (50 ng/mL) to induce expression of COX-2. Treated cells produced detectable amounts of PGD3 and its metabolites at 48 hours after LPS treatment. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of culture medium supernatants confirmed the increased production of PGD3, Δ12-PGJ3, and 15d-PGJ3 (Figure 1A and supplemental Figure 1) only in cells treated with EPA. Based on the LC-retention times and mass fragmentation patterns, the cellular metabolites were identified as PGD3 (m/z 349; supplemental Figure 1A), Δ12-PGJ3 (m/z 331.45; Figure 1B), and 15d-PGJ3 (m/z 313.45; supplemental Figure 1A). These metabolites were not seen in cells cultured without exogenous EPA (Figure 1A). We estimated that treatment of macrophages with 50μM EPA produced ∼ 0.15μM Δ12-PGJ3/106 cells in 48 hours. Nonenzymatic dehydration of PGD3 in PBS produced PGJ3, Δ12-PGJ3, and 15d-PGJ3 in vitro. Incubation of PGD3 (100 μg/mL; Cayman Chemicals) in a serum-free environment for 24-48 hours at 37°C led to the formation of Δ12-PGJ3, Δ13-PGJ3 (PGJ3), and 15d-PGJ3, all of which were well resolved on a reversed-phase LC (C18) column with retention times of 9.63, 9.97, and 11.02 minutes, respectively (supplemental Figure 1B-C). Prolonged incubation of PGD3 up to 144 hours at 37°C also produced these metabolites, with Δ12-PGJ3 predominating over the others (supplemental Figure 1D). The presence of serum (10%) did not affect the conversion of PGD3 (supplemental Figure 1E). UV-spectroscopic analysis of the purified Δ12-PGJ3 confirmed the presence of a conjugated diene-like structure with a λmax of 242nM, whereas PGJ3 and 15d-PGJ3 showed a distinct peak at ∼ 300nM, which is characteristic of the cyclopentenone structure (supplemental Figure 2). These data confirm the endogenous production of PGD3 metabolites and the enhanced stability of Δ12-PGJ3 in an aqueous environment.

Figure 1.

Endogenous production and proapoptotic properties of Δ12-PGJ3. (A) Endogenous formation of PGD3, Δ12-PGJ3, and 15d-PGJ3 in RAW264.7 macrophages (LC-UV trace; n = 3 for EPA-treated cells). (B) Representative LC-MS of Δ12-PGJ3 containing eluates with characteristic fragmentation pattern. (C) Dose-response demonstrating the effect of Δ12-PGJ3 on BCR-ABL+ LSCs compared with normal HSCs (MSCV-GFP+ HSCs). Cells were treated ex vivo with Δ12-PGJ3 for 36 hours. Apoptosis was measured by annexin V staining. (D) Kit+Sca-1+Lin−BCR-ABL–GFP+ cells sorted from the BM and cultured ex vivo in medium containing Δ12-PGJ3 (25nM) or vehicle control for 36 hours followed by flow cytometric analysis of GFP+ cells (n = 3). Means ± SEM are shown. * P < .005. Data are expressed as a percentage of input GFP+ cells. (E) Dose response of LSCs isolated from FV mice with indicated concentrations of Δ12-PGJ3 at the end of 36 hours of incubation. Apoptosis of LSCs was examined by annexin V staining followed by flow cytometry. (F) FV-LSCs were cultured ex vivo with 25nM concentrations of each compound for 36 hours (n = 3). Means ± SEM shown. *P < .0001 compared with PGJ3.

Δ12-PGJ3 induces apoptosis of LSCs

Previous studies have demonstrated that 15d-PGJ2 induces apoptosis of several cancer cell lines, and that this effect was mediated in part by the inhibition of NF-κB and/or by activation of PPARγ.27 In the present study, we examined the proapoptotic properties of PGD3 metabolites in the 2 well-studied murine models of leukemia. Mice were transplanted with HSCs transduced with a BCR-ABL–expressing retrovirus (hereafter referred to as BCR-ABL mice). Incubation of Kit+Sca1+Lin−GFP+ LSCs isolated from the spleens of BCR-ABL mice with low doses of Δ12-PGJ3 significantly increased apoptosis of these cells with an IC50 of ∼ 12nM, but did not affect the normal HSCs, which are represented by Kit+Sca1+Lin−GFP+ cells isolated from mice transplanted with HSCs transduced with a MSCV-GFP control virus (hereafter referred to as MSCV-control mice; Figure 1C). Similar effects were also observed when BCR-ABL LSCs (Kit+Sca1+Lin−GFP+) isolated from the BM were treated ex vivo with Δ12-PGJ3 (Figure 1D). An identical effect was also observed with FV-LSCs (Figure 1E). Incubation of FV-LSCs with EPA had no effect, whereas PGJ3 displayed only a 2-fold increase in apoptosis and Δ12-PGJ3 and 15d-PGJ3 treatment at 25nM led to a significant increase (∼ 75%) in apoptosis (Figure 1F). We also tested the effects of ARA-derived PGJ2, Δ12-PGJ2, and 15d-PGJ2 on FV-LSCs and LSCs derived from BCR-ABL mice. We observed responses similar to Δ12-PGJ3 with Δ12-PGJ2 and 15d-PGJ2, whereas PGJ2 was largely ineffective (supplemental Figure 3A). In contrast, there was no apoptosis of FV-LSCs treated with 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2, a 15d-PGJ2 derivative that lacks an unsaturation at carbon 9 (supplemental Figure 3B). Ex vivo treatment of Sca1+GFP+Kit+BCR-ABL+ LSCs sorted from the spleens of transplanted mice with 25-1000nM Δ12-PGJ3 or 15d-PGJ2 significantly increased their apoptosis; whereas 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 was ineffective even at high concentrations up to 1μM (supplemental Figure 3C). Whereas all of these studies clearly demonstrated the proapoptotic ability of Δ12-PGJ3, we next examined if Δ12-PGJ3 modulated NF-κB or PPARγ, which has been shown to be the mechanism by which 15d-PGJ2 induces apoptosis.11,12 Δ12-PGJ3 did not affect the NF-κB pathway, as seen by gel-shift analysis at concentrations in high-nanomolar range in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (supplemental Figure 4A). Furthermore, analysis of the NF-κB activation in sorted BCR-ABL+LSCs treated with Δ12-PGJ3 by EMSA and Western blotting of nuclear extracts also demonstrated lack of activation of NF-κB (supplemental Figure 4B). In addition, Δ12-PGJ3 was unable to activate PPARγ in reporter assays at nanomolar concentrations that caused apoptosis of LSCs (supplemental Figure 4C). Similarly, treatment of FV-LSCs with rosiglitazone, a synthetic agonist of PPARγ,28 did not affect proliferation of LSCs, indicating that the apoptotic pathway did not involve PPARγ (supplemental Figure 3B inset). Our data indicate that an alkylidenecyclopentenone structure in CyPGs is absolutely essential to effectively inducing apoptosis of LSCs from 2 murine models of leukemia by a mechanism that does not involve PPARγ or NF-κB.

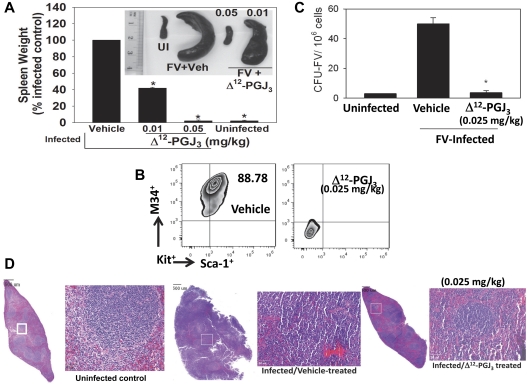

Δ12-PGJ3 eradicates leukemia and alleviates splenomegaly in FV-infected mice

Given the potent proapoptotic potential of Δ12-PGJ3 on LSCs in vitro, we tested the ability of Δ12-PGJ3 to ablate LSCs in FV-infected leukemic mice. Seven days after infection with FV, the mice were treated with Δ12-PGJ3 at 0.01and 0.05 mg/kg/d for an additional week and then euthanized on day 14. Compared with the vehicle-treated mice, FV-infected mice treated with Δ12-PGJ3 at 0.05 mg/kg (Figure 2A) and 0.1 mg/kg (data not shown) showed no signs of splenomegaly. Although 0.01 mg/kg treatment did not completely ablate splenomegaly, there was a significant reduction (∼ 50%; Figure 2A). A similar trend was seen with 15d-PGJ2 (supplemental Figure 5B); whereas 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 did not have any effect on the amelioration of splenomegaly (supplemental Figure 5B). Flow cytometric analysis clearly demonstrated that Δ12-PGJ3 (0.025 mg/kg) completely eradicated the Sca1+Kit+M34+Ter119lo cells in the spleen (Figure 2B), which represents the LSC population (S.H., P.H., and R.F.P., unpublished data). Identical results were obtained with 15d-PGJ2, whereas 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 treatment was ineffective (supplemental Figures 5 and 6). In agreement with the absence of splenomegaly and complete ablation of LSCs, total leukocyte and reticulocyte counts were decreased to normal levels in Δ12-PGJ3–treated (supplemental Figure 5A) and 15d-PGJ2–treated mice (supplemental Figure 5C). Previous studies showed that transformed leukemia cells form FV-CFUs that exhibit factor-independent growth that can be measured by plating infected spleen cells in methylcellulose medium without growth factors.24 FV-CFU in the Δ12-PGJ3–treated mice was completely reduced to background levels, similar to those in the uninfected mice (Figure 2C). Histological examination of vehicle-treated, FV-infected spleens showed complete effacement of splenic architecture as a result of infiltration of leukemic blasts, with erythroid progenitor expansion replacing the sinusoids (Figure 2D). Consistent with the results of decreased splenomegaly, treatment of FV-infected mice with Δ12-PGJ3 led to the better demarcation of periarteriolar lymphoid tissue (Figure 2D). The erythroid progenitor cells were substantially lower, and a few giant cells were seen accompanied by an increase in the number of apoptotic bodies with increased individual tumor cell necrosis in the CyPG-treated group compared with the vehicle-treated, FV-infected group (Figure 2D). CyPG treatment of FV-infected mice restored the splenic architecture, with well-defined red and white pulp regions, as in the uninfected mice.

Figure 2.

IP administration of Δ12-PGJ3 eradicates FV-leukemia in mice. (A) Spleen weights of FV-infected mice treated with various doses of Δ12-PGJ3 (mg/kg body weight). n = 10 per treatment group. Δ12-PGJ3 treatment at the indicated dosage was started at 1 week after infection for a period of 7 days. *P < .05. Inset: representative spleens from each treatment group. UI indicates uninfected mice. (B) Analysis of LSCs (M34+Kit+Sca1+) in the spleens of FV-infected mice treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle (Veh) control. (C) FV-CFU formation in Δ12-PGJ3– and vehicle control–treated mice. *P < .001. (D) H&E staining of spleen sections from uninfected (left), FV-infected–vehicle treated (middle), and FV-infected– Δ12-PGJ3–treated mice (right) on day 14 after infection. Small box indicated on each section on the left is magnified on the right side. Scale bars indicate 500 μm.

Δ12-PGJ3 inhibits the expansion of LSCs but not the viral replication

To rule out the possibility that Δ12-PGJ3 blocks FV-induced leukemia by inhibiting viral replication, a second model of FV-induced leukemia was used in which the FV-LSCs were transplanted into Stk−/− mice. Short-form Stk (Sf-Stk), a naturally occurring truncated form of Stk/Ron receptor tyrosine kinase, is encoded by the FV-susceptibility locus 2 (Fv2).29 Fv2-resistant mice express low levels of Sf-Stk, which fails to support the proliferation of infected cells.25,29,30 Therefore, transplantation of FV-LSCs into Stk−/− mice results in leukemia caused by the expansion of donor cells and not by the spread of viral infection. LSCs generated from wild-type mice were transplanted into syngeneic Stk−/− mice. Treatment with Δ12-PGJ3 (at 0.025 and 0.05 mg/kg) led to significantly decreased splenomegaly with a concomitant decrease in leukocyte counts (Figure 3A-C). Flow cytometric analysis of LSCs in the spleens of transplanted Stk−/− mice indicated complete ablation of M34+Sca1+Kit+ cells upon treatment with Δ12-PGJ3 (Figure 3D), whereas LSCs from Stk−/− mice treated with 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 or vehicle did not have any effect on their viability and did not alleviate splenomegaly (supplemental Figure 7). Treatment of FV-induced leukemia with Δ12-PGJ3 or 15d-PGJ2 significantly decreased the hematocrit, WBC counts, and reticulocyte counts, which are all hallmarks of leukemia, whereas 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 had no effect on any parameter tested (Figure 3C and supplemental Figure 5C).

Figure 3.

Effect of Δ12-PGJ3 treatment on leukemia induced by transplanting FV-induced LSCs expanded in vitro into FV-resistant Stk−/− mice. (A) Photograph of spleens from Stk−/− mice 7 weeks after transplantation with FV-LSCs followed by treatment with vehicle, 0.05 mg/kg, or 0.025 mg/kg Δ12-PGJ3 for 1 week. (B) Spleen weights are shown for the conditions in panel A. n = 5 per group, *P < .05 compared with the vehicle-treated group. (C) WBC counts in LSC-transplanted Stk−/− mice treated with indicated amounts of Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. n = 5 per group. *P < .05 compared with vehicle-treated group. (D) M34+Kit+Sca1+ cells in Stk−/− mice transplanted with LSCs. Spleen cells that were isolated and gated on Kit+, expression of M34 and Sca1 is shown. n = 5 per group.

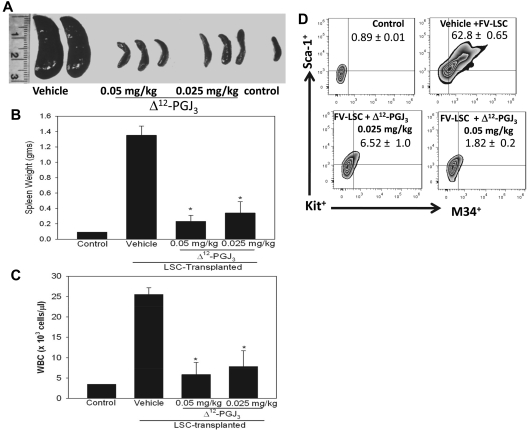

Δ12-PGJ3 alleviates leukemia caused by transplantation of BCR-ABL+ LSCs

Our in vitro studies (Figure 1) showed that Δ12-PGJ3 treatment caused apoptosis of BCR-ABL+LSCs but not the normal HSCs (MSCV-GFP+ HSCs). We also examined the antileukemic activity of Δ12-PGJ3 in BCR-ABL mice, which is a model for the chronic phase of CML.17 As shown in Figure 4, treatment of mice transplanted with BCR-ABL+ LSCs with 0.05 mg/kg of Δ12-PGJ3 for 1 week completely alleviated splenomegaly with spleen weights close to those transplanted with the MSCV-GFP+ HSCs (Figure 4A). Furthermore, Δ12-PGJ3 treatment also significantly decreased the leukocyte counts in the peripheral blood (Figure 4B), decreased Kit+Sca1+ GFP+ LSCs in the spleen (Figure 4C), and eradicated Kit+Sca1+Lin−GFP+ LSCs in the BM of the BCR-ABL+ LSC–transplanted mice (Figure 4D). More importantly, treatment of BCR-ABL+ LSC–transplanted mice with Δ12-PGJ3 rescued all of the mice, whereas those treated with vehicle died 2 weeks after transplantation of LSCs (Figure 4E). In contrast, treatment of mice transplanted with MSCV-GFP+ HSC with Δ12-PGJ3 had no effect on WBC counts, other hematologic parameters, or survival, suggesting that Δ12-PGJ3 does not affect steady-state hematopoiesis (Figure 4E). To further demonstrate that Δ12-PGJ3 does not affect normal hematopoietic differentiation, we next tested whether Δ12-PGJ3 treatment had an adverse effect on hematopoietic progenitors by testing its effect on colony-forming ability in CFC assays. BM from 5-FU–treated mice was plated in methylcellulose medium containing multiple cytokines in the absence or presence of 25nM Δ12-PGJ3. There was no difference in the number of CFCs in Δ12-PGJ3–treated compared with control (PBS)–treated cells (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

IP administration of Δ12-PGJ3 eradicates LSCs and prolongs survival in a murine CML model. (A) Analysis of the effect of Δ12-PGJ3 treatment on the development of splenomegaly in mice transplanted with BCR-ABL-GFP+ LSCs. Representative photographs of spleens from control and BCR-ABL–transplanted mice treated with Δ12-PGJ3 (0.025 mg/kg) or vehicle control with corresponding spleen weights. n = 10 per treatment group. *P < .05. (B) Analysis of WBC counts of BCR-ABL+ LSC- or MSCV-HSC–transplanted mice treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. *P < .0001. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of Sca-1+Kit+GFP+ cells in the spleens of mice transplanted with BCR-ABL+ LSCs or MSCV+ HSCs treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. n = 5 per group. *P < .001. (D) Analysis of LSCs (Kit+Sca-1+Lin−GFP+) in the BM of BCR-ABL+ LSC-transplanted and Δ12-PGJ3–treated mice after 5 weeks of last dose of Δ12-PGJ3 (0.025 mg/kg). As a control, BCR-ABL+ LSC–transplanted mice treated with vehicle for 1 week were used for comparison. (E) Survival curves of mice transplanted with BCR-ABL+ LSCs or MSCV-GFP+ HSCs on treatment with Δ12-PGJ3 (0.025 mg/kg) or vehicle. n = 8 per treatment group. (F). HSCs were isolated from the BM of C57BL/6 mice and plated in methylcellulose (1 × 106 cells/mL/well; erythropoietin, SCF, IL-3, and BMP4) with PBS or Δ12-PGJ3 (25nM) and cultured for 1 week and then hematopoietic CFCs were scored. Data shown are representative of triplicate experiments.

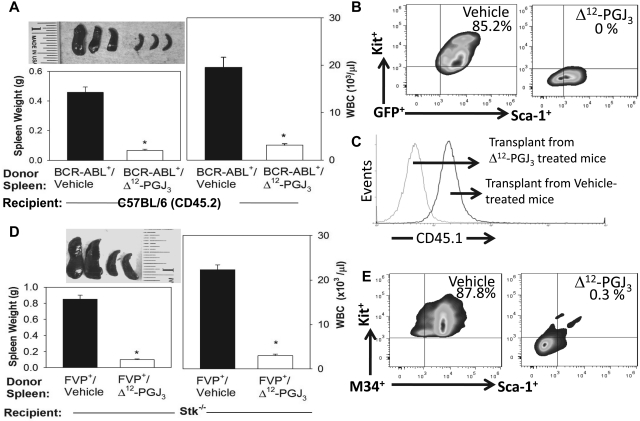

To confirm that Δ12-PGJ3 had eradicated LSCs, we performed secondary transplantations using splenocytes from Δ12-PGJ3– or vehicle-treated BCR-ABL mice. The original donor MIGR–BCR-ABL–transduced BM cells were marked with CD45.1+, whereas the primary and secondary recipients were CD45.2+. Secondary transplantations that received donor cells from vehicle-treated mice rapidly developed splenomegaly and high WBC counts, which are indicative of leukemia. In contrast, second recipients of donor cells from Δ12-PGJ3–treated mice failed to develop splenomegaly or high WBC counts (Figure 5A). Further analysis of spleens for LSCs showed that recipients of donor cells from Δ12-PGJ3–treated mice lacked Kit+Sca1+GFP+ cells. In addition, analysis of CD45.1 expression also showed that CD45.1+ donor cells were not present in the spleen (Figure 5C). Secondary recipients of donor cells from vehicle-treated mice exhibited large numbers of donor-derived Kit+Sca1+GFP+ and CD45.1+ donor cells in their spleens (Figure 5B-C). We performed similar secondary transplantation experiments with donor spleen cells isolated from FV-LSC–transplanted BALB/c-Stk−/− mice treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle. Similar to the BCR-ABL secondary transplantations, mice receiving donor cells from Δ12-PGJ3–treated mice failed to develop splenomegaly or high WBC counts and lacked LSCs in their spleens (Figure 5D-E). These data clearly demonstrate the ability of Δ12-PGJ3 to eradicate LSCs in 2 diverse murine models of myeloid leukemia.

Figure 5.

Secondary transplantation of spleen cells from Δ12-PGJ3–treated recipients showing the absence of leukemia. Panels A through C represent secondary transplantation of CD45.1+ BCR-ABL mice treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control transplanted into CD45.2 recipient mice. Panels D and E represent FV-LSCs from Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control–treated mice transplanted into secondary BALB/c-Stk−/− recipients. (A) Spleen morphology (top left), spleen weight (bottom left), and WBC counts of mice after secondary transplantation that received donor cells from vehicle-treated or Δ12-PGJ3–treated donor cells (right). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of spleen cells from secondary transplantations. Cells were gated on GFP+ and the expression of Kit and Sca1 are shown. (C) Analysis of donor CD45.1 expression in spleen cells. (D) Spleen morphology (top left), spleen weight (bottom left), and WBC counts of mice after secondary transplantation that received donor cells from vehicle-treated or Δ12-PGJ3–treated donor cells (right). (E) Flow cytometric analysis of spleen cells from secondary transplantations. Cells are gated on M34+ and the expression of Kit and Sca1 is shown.

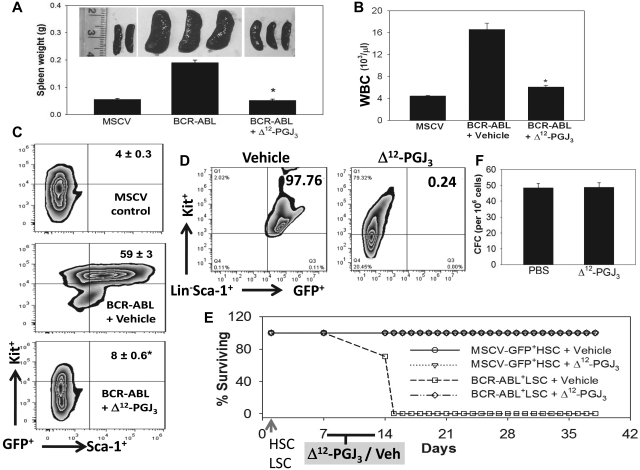

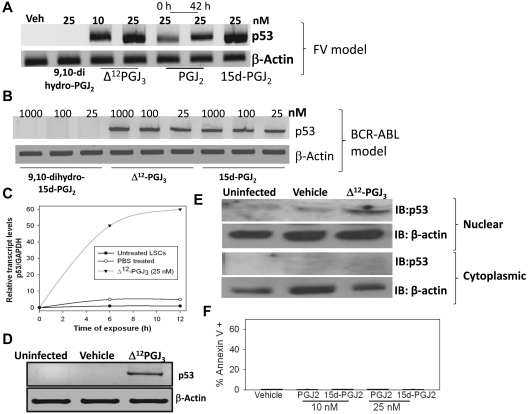

EPA metabolites selectively activate p53 in LSCs

Ex vivo treatment of sorted LSCs from FV-infected mice with 10 or 25nM Δ12-PGJ3 for 12 hours led to significant up-regulation of p53 expression at the transcript level (Figure 6A). Treatment of LSCs with 15d-PGJ2 also showed a similar trend, whereas 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 was ineffective (Figure 6A). Interestingly, PGJ2 treatment up-regulated the expression of p53 to only a minor degree, not to the extent observed with other CyPGs. However, preincubation of PGJ2 with medium (at 37°C) for 42 hours before the addition of LSCs led to increased expression of p53, which suggests a time-dependent isomerization event that possibly converts PGJ2 (Δ13-PGJ2) to Δ12-PGJ2 or 15d-PGJ2 and PGJ3 (Δ13-PGJ3) to Δ12-PGJ3 or 15d-PGJ3, which makes the latter metabolites more potent than the precursor (Figure 1E). Treatment of BCR-ABL+ LSCs ex vivo with Δ12-PGJ3 or 15d-PGJ2 (25nM) also led to a similar increase in p53 mRNA, whereas 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 treatment was ineffective (Figure 6B). Time-course analysis showed that p53 transcript levels rapidly increased after treatment of FV-LSCs ex vivo with Δ12-PGJ3 such that by 12 hours, maximal p53 expression was observed (Figure 6C). Analysis of p53 expression in total spleens of uninfected and vehicle-treated, FV-infected mice clearly showed no increase; however, Δ12-PGJ3–treated mice (treated for 1 week) showed a significant expression of p53 in the spleen (Figure 6D). Similarly, we observed an increase in the nuclear levels of p53 protein in sorted LSCs treated with Δ12-PGJ3 for 12 hours, but not in the untreated or vehicle-treated cells (Figure 6E). To confirm the role of p53 as a critical mediator of Δ12-PGJ3–dependent LSC apoptosis, we examined the proapoptotic role of CyPGs in MEL cells that lack functional p53. MEL cells are derived from FV-CFUs that have been expanded into a cell line. Treatment of MEL cells with Δ12-PGJ3 failed to initiate apoptosis (Figure 6F). MEL cells exhibited sensitivity to treatment with antileukemic drugs such as daunorubicin, mitoxantrone, and cytarabine (supplemental Figure 8), but not to nutlin, a small-molecule inhibitor of the MDM2-p53 interaction that causes reactivation of p53. These studies confirm the role of Δ12-PGJ3–dependent activation of the p53 pathway in apoptosis of LSCs.

Figure 6.

Treatment of LSCs in vitro with Δ12-PGJ3 increases p53 mRNA expression. Dose response of p53 mRNA expression in LSCs sorted from FV-infected (A) or BCR-ABL+ HSC–transplanted spleens (B). (C) Real-time PCR analysis of the time course of p53 expression in FV-LSCs treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. (D) Analysis of p53 mRNA expression in the spleens of FV-infected mice after treatment with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. (E) Analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic p53 protein localization in FV-LSCs treated with Δ12-PGJ3 (25nM) or vehicle control. (F) Analysis of apoptosis of MEL cells treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. All data are representative 3 experiments.

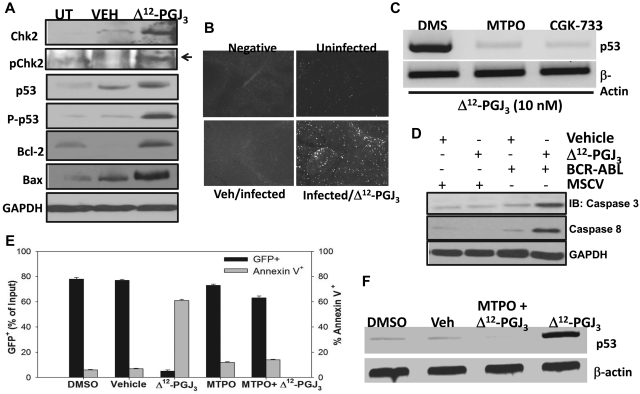

The activation of p53 activity is known to be regulated by an ATM-dependent signaling pathway.31–33 We next examined whether ATM played a critical role in the proapoptotic activity of Δ12-PGJ3. In addition to increased phosphorylated-p53 protein, we observed an increase in the levels of pChk2 only in the total spleen extracts from the Δ12-PGJ3–treated mice transplanted with FV-LSCs (Figure 7A). TUNEL staining of splenic sections from FV-infected mice showed increased apoptosis only in the Δ12-PGJ3–treated group (Figure 7B). In agreement with the TUNEL staining results, we observed activation of Bax, a downstream mediator of apoptosis in the spleens of Δ12-PGJ3–treated, FV-infected mice, but not in vehicle-treated, FV-infected mice (Figure 7A). These experiments suggested the involvement of the ATM-p53 signaling axis in promoting Δ12-PGJ3–dependent apoptosis. To further confirm the involvement of ATM, we used 2 well-characterized inhibitors of ATM. Preincubation of sorted FV-LSCs ex vivo with a high-affinity inhibitor of ATM (MTPO), as well as a dual inhibitor of ATM and the related ATR kinase (CGK-733), followed by treatment with Δ12-PGJ3 blocked the CyPG-dependent expression of p53, which indicated that ATM served as a critical mediator of apoptosis by Δ12-PGJ3 (Figure 7C). Similar to what we observed with FV, treatment of BCR-ABL+ LSCs (Kit+Sca1+Lin−GFP+) with 25nM Δ12-PGJ3 led to a significant increase in apoptosis, as seen by increased annexin V staining and Western blot analysis of caspase 3 and caspase 8 activation (Figure 7D). Δ12-PGJ3 treatment led to an increase in p53 transcription, whereas there was a concomitant decrease in GFP+ cells (Figure 7E). Similar to what we observed in FV-LSCs, pretreatment of these cells with MTPO blocked the effect of Δ12-PGJ3 on apoptosis and the induction of p53 expression (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

Activation of the ATM pathway is pivotal for the antileukemic effect of Δ12-PGJ3. (A) Western blot analysis of FV-LSCs treated with Δ12-PGJ3 or vehicle control. Cell lysates were probed with indicated Abs. (B) TUNEL assay of spleen sections from Δ12-PGJ3- or vehicle-treated, FV-infected mice. (C) Analysis of p53 transcript levels in FV-LSCs treated with Δ12-PGJ3 (25nM) or in combination with the ATM inhibitor MTPO (50nM), CGK-733 (1μM), or DMSO control. Representative results of 3 experiments are shown. (D) Western blot analysis of caspase-3 and caspase-8 activation. Whole cell lysates from spleens of mice transplanted with MSCV-GFP or BCR-ABL+ LSCs that were treated with vehicle or Δ12-PGJ3 (0.025 mg/kg) were probed with the indicated Abs. Lanes 1 through 4 represent MSCV-GFP+ HSC + vehicle, MSCV-GFP+ HSCs + Δ12-PGJ3, BCR-ABL+LSC + vehicle, and BCR-ABL+LSC + Δ12-PGJ3, respectively. Results shown are representative of n = 3 mice per group. (E) Analysis of the role of ATM in the Δ12-PGJ3–dependent apoptosis of BCR-ABL–GFP+ LSCs. LSCs were pretreated with MTPO (50nM) or vehicle followed by the addition of Δ12-PGJ3 (25nM). GFP+ and annexin V+ cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (n = 3). Shown are means ± SEM. (F) Analysis of p53 mRNA expression in BCR-ABL+ cells sorted from the spleens of mice transplanted with BCR-ABL+ LSCs followed by treatment with Δ12-PGJ3 (25nM) alone or in combination with the ATM inhibitor MTPO (50nM). Representative results of 3 experiments are shown.

Discussion

Previous animal and human studies have documented an important role of n-3 PUFAs in their ability to affect cancer cell growth, slow histopathological progression, and increase survival.34 Recent studies have shown that metabolites of n-3 PUFAs, such as resolvins, are capable of promoting resolution of inflammation by limiting leukocyte infiltration while coordinating inflammatory cell efflux.35 In the present study, we demonstrate the metabolism of EPA-derived PGD3 to cyclopentenone PGJ3, Δ12-PGJ3, and 15d-PGJ3 in macrophages. Of these stable metabolites that were detected in the macrophage culture medium, only Δ12-PGJ3, and 15d-PGJ3 targeted LSCs for apoptosis in an FV-induced leukemia and a BCR-ABL+ retrovirus-based murine model of CML. In contrast, EPA and PGJ3 were ineffective. These data suggest a structure-function relationship in the form of an alkylidenecyclopentenone structure with an unsaturation at carbon 12 as a critical requirement for the apoptotic activity of CyPGs.

Our data demonstrating the endogenous production of PGD3 and Δ12-PGJ3 in EPA-treated macrophages and the in vitro conversion of PGD3 to Δ12-PGJ3 in the presence of serum (Figure 1 and supplemental Figure 1E) are consistent with previous reports of the metabolism of EPA to PGD3 in the uvea and serum of human subjects consuming fish oil supplements.36–38 These observations stress the important question of whether sufficient quantities of Δ12-PGJ3 are formed in vivo to exert any biologic activity, such as the apoptosis of LSCs. Indeed, based on LC-MS/MS studies, a sufficient quantity of Δ12-PGJ3 (∼ 0.15μM/106 macrophages) was produced by macrophages, which was well within the concentration required to cause apoptosis of LSCs (IC50 = 7nM). Despite its proapoptotic effects on LSCs, Δ12-PGJ3 had no adverse effects on HSCs or downstream progenitors. Interestingly, previous studies have demonstrated that many immune cells, including macrophages and T cells, express the 2 major enzymes, COX-2 and H-PGDS,26 which are critical for the production of Δ12-PGJ3. In fact, the inability of EPA to cause any apoptosis of LSCs in vitro suggests that LSCs may not be the main source of Δ12-PGJ3. Alternatively, splenic tissue, which is rich in monocytes and T cells, also expresses high amounts of H-PGDS39 that may aid in the metabolism of dietary EPA to Δ12-PGJ3 to activate proapoptotic pathways in LSCs in a paracrine mechanism.

Our studies indicate that LSCs exhibit increased sensitivity to Δ12-PGJ3 and other related CyPGs in a stereoselective manner. The induction of apoptosis in LSCs by these endogenous metabolites requires the ATM/p53–signaling axis, which causes complete ablation of leukemia in vivo, as seen in 2 different mouse models of leukemia. Our data show that CyPG treatment eliminates LSCs to such an extent that no LSC activity is observed on secondary transplantation. There have been several reports on the induction of apoptosis by 15d-PGJ2 treatment in immortalized leukemic cell lines, in which the increased production of reactive oxygen species is implicated.40 However, at the concentrations of Δ12-PGJ3 used in this investigation, which are several orders of magnitude less than those known to cause oxidative stress, we did not observe any induction of reactive oxygen species in the primary LSCs (data not shown). Moreover, the observed differences in the proapoptotic potential of PGJ3 and Δ12-PGJ3 (15d-PGJ3), which are both electrophiles capable of interacting with cellular thiol-containing nucleophiles, also invoke other mechanisms. We have also considered the likelihood of a high-affinity CyPG-target protein specifically expressed in LSCs that mediates their selective apoptosis; this is currently being investigated and the results will be reported in the future. It is also possible that CyPG could activate ATM in a DNA damage–independent mechanism by covalently interacting with the Cys thiols present in the dimer interface of ATM. Such an interaction could activate the intrinsic kinase activity, leading to autophosphorylation and dissociation of the dimeric ATM molecule and to the phosphorylation of other downstream substrates such as Chk2 and p53. Increased phosphorylated p53, formed as a result of increased ATM activity, then activates transcription of p53 in a feed-forward loop to increase total p53 levels, which is in contrast to the ability of 15d-PGJ2 to stabilize and functionally inactivate p53 by covalent modification of specific cysteine thiols in human MCF-7 breast cancer cells, albeit at high concentrations.41 Previous studies by Kobayashi et al10 have shown that the covalent modification of ATM by CyPG activated the enzyme; however, key residues involved in the interaction have not been identified and further work may shed more light on the mechanism of its activation by low concentrations of Δ12-PGJ3 and other related CyPGs. Therefore, our studies support the role of ATM as an important mediator of the electrophilic “stress” response pathway in LSCs.

In summary, we demonstrate the ability of macrophages to produce endogenous Δ12-PGJ3 that displays potent proapoptotic activity toward LSCs in 2 murine models of leukemia by activating the ATM-p53 pathway of apoptosis. IP administration of Δ12-PGJ3 eradicated LSCs in a BCR-ABL retroviral model of CML, with no relapse noted 5 weeks after administration of the last dose of Δ12-PGJ3. In contrast, vehicle-treated mice transplanted with LSCs failed to survive past day 16 after transplantation (Figure 4F). Current anticancer therapies are ineffective against LSCs; therefore, the ability of a stable endogenous metabolite to ablate LSCs identifies it as a potential therapy. In addition, these results indicate that Δ12-PGJ3, derived from dietary n-3 PUFAs, has the potential to serve as a chemopreventive agent in the treatment of leukemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Charanjeet Singh (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis-St Paul, MN) for help with histological evaluation; Robert Murphy (University of Colorado, Denver, CO) for suggestions on the spectroscopic characterization of CyPGs; Thomas Loughran (Pennsylvania State University Cancer Institute, Hershey, PA) for the gift of daunorubicin, mitoxantrone, and cytarabine; Ross Hardison (The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA) for the gift of MEL cells; and Warren Pear (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) for the MIGR–BCR-ABL and control MSCV-GFP retroviruses.

These studies were funded in part by US Public Health Service grants (R01-DK077152 and R21-AT004350 to K.S.P., R01-DK080040 to R.F.P., and R01-HL66471 to P.H.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.H., N.K., C.C., R.F.P., J.P.v.d.H., and K.S.P. designed the research; S.H., N.K., C.C., K.C.R., K.T.H., U.H.G., and J.T.T. performed the research; S.H., N.K., C.C., K.C.R., M.J.K., P.H., R.F.P., J.T.T., J.P.v.d.H., and K.S.P. analyzed the data; and R.F.P. and K.S.P. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert F. Paulson or K. Sandeep Prabhu, 115 Henning Bldg, Dept of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; e-mail: rfp5@psu.edu or ksprabhu@psu.edu.

References

- 1.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(5):349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serhan CN, Yacoubian S, Yang R. Anti-inflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:279–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terry P, Lichtenstein P, Feychting M, Ahlbom A, Wolk A. Fatty fish consumption and risk of prostate cancer. Lancet. 2001;357(9270):1764–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanamala J, Glagolenko A, Yang P, et al. Dietary fish oil and pectin enhance colonocyte apoptosis in part through suppression of PPARdelta/PGE2 and elevation of PGE3. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(4):790–796. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serhan CN, Chiang N. Endogenous pro-resolving and anti-inflammatory lipid mediators: a new pharmacologic genus. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(suppl 1):S200–S215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wada M, DeLong CJ, Hong YH, et al. Enzymes and receptors of prostaglandin pathways with arachidonic acid-derived versus eicosapentaenoic acid-derived substrates and products. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(31):22254–22266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Prostaglandin D synthase: structure and function. Vitam Horm. 2000;58:89–120. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(00)58022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzpatrick FA, Wynalda MA. Albumin-catalyzed metabolism of prostaglandin D2. Identification of products formed in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1983;258(19):11713–11718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibata T, Kondo M, Osawa T, Shibata N, Kobayashi M, Uchida K. 15-deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2. A prostaglandin D2 metabolite generated during inflammatory processes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(12):10459–10466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi M, Ono H, Mihara K, et al. ATM activation by a sulfhydryl-reactive inflammatory cyclopentenone prostaglandin. Genes Cells. 2006;11(7):779–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossi A, Kapahi P, Natoli G, et al. Anti-inflammatory cyclopentenone prostaglandins are direct inhibitors of IkappaB kinase. Nature. 2000;403(6765):103–108. doi: 10.1038/47520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 15-Deoxy-delta 12, 14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR gamma. Cell. 1995;83(5):803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassane DC, Guzman ML, Corbett C, et al. Discovery of agents that eradicate leukemia stem cells using an in silico screen of public gene expression data. Blood. 2008;111(12):5654–5662. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen JM, Jordan CT. The increasing complexity of the cancer stem cell paradigm. Science. 2009;324(5935):1670–1673. doi: 10.1126/science.1171837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-David Y, Bernstein A. Friend virus induced erythroleukemia and the multistage nature of cancer. Cell. 1991;66:831–834. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schemionek M, Elling C, Steidl U, et al. BCR-ABL enhances differentiation of long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010;115(16):3185–3195. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pear WS, Miller JP, Xu L, et al. Efficient and rapid induction of a chronic myelogenous leukemia-like myeloproliferative disease in mice receiving P210 bcr/abl-transduced bone marrow. Blood. 1998;92(10):3780–3792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Y, Swerdlow S, Duffy TM, Weinmann R, Lee FY, Li S. Targeting multiple kinase pathways in leukemic progenitors and stem cells is essential for improved treatment of Ph+ leukemia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(45):16870–16875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606509103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao C, Chen A, Jamieson CH, et al. Hedgehog signalling is essential for maintenance of cancer stem cells in myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2009;458(7239):776–779. doi: 10.1038/nature07737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian A, Hegde S, Porayette P, Yon M, Hankey P, Paulson RF. Friend virus utilizes the BMP4-dependent stress erythropoiesis pathway to induce erythroleukemia. J Virol. 2008;82(1):382–393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02487-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harandi OF, Hedge S, Wu DC, McKeone D, Paulson RF. Murine erythroid short-term radioprotection requires a BMP4-dependent, self-renewing population of stress erythroid progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(12):4507–4519. doi: 10.1172/JCI41291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vunta H, Davis F, Palempalli UD, et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of selenium are mediated through 15-deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(25):17964–17973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Cloyd M, et al. Characterization of mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for Friend murine leukemia virus-induced erythroleukemia cells: friend-specific and FMR-specific antigens. Virology. 1981;112(1):131–144. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90619-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mager DL, Mak TW, Bernstein A. Quantitative colony method for tumorigenic cells transformed by two distinct strains of Friend leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(3):1703–1707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finkelstein L, Ney P, Liu Q, Paulson R, Correll P. Sf-Stk kinase activity and the Grb2 binding site are required for Epo-independent growth of primary erythroblasts infected with Friend virus. Oncogene. 2002;21:3562–3570. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldon SE, O'Loughlin CW, Ray DM, Landskroner-Eiger S, Seweryniak KE, Phipps RP. Activated human T lymphocytes express cyclooxygenase-2 and produce proadipogenic prostaglandins that drive human orbital fibroblast differentiation to adipocytes. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(4):1183–1193. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Na HK, Surh YJ. Transcriptional regulation via cysteine thiol modification: a novel molecular strategy for chemoprevention and cytoprotection. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45(6):368–380. doi: 10.1002/mc.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nolte RT, Wisely GB, Westin S, et al. Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Nature. 1998;395(6698):137–143. doi: 10.1038/25931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Persons DA, Paulson RF, Loyd MR, et al. Fv2 encodes a truncated form of the Stk receptor tyrosine kinase. Nat Genet. 1999;23(2):159–165. doi: 10.1038/13787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subramanian A, Teal HE, Correll PH, Paulson RF. Resistance to friend virus-induced erythroleukemia in W/W(v) mice is caused by a spleen-specific defect which results in a severe reduction in target cells and a lack of Sf-Stk expression. J Virol. 2005;79(23):14586–14594. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14586-14594.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421(6922):499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giaccia AJ, Kastan MB. The complexity of p53 modulation: emerging patterns from divergent signals. Genes Dev. 1998;12(19):2973–2983. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavin MF, Kozlov S. ATM activation and DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(8):931–942. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.8.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wall R, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. Fatty acids from fish: the anti-inflammatory potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. Nutr Rev. 2010;68(5):280–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norling LV, Serhan CN. Profiling in resolving inflammatory exudates identifies novel anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving mediators and signals for termination. J Intern Med. 2010;268(1):15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kulkarni PS, Srinivasan BD. The effect of intravitreal and topical prostaglandins on intraocular inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1982;23(3):383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kulkarni PS, Srinivasan BD. Eicosapentaenoic acid metabolism in human and rabbit anterior uvea. Prostaglandins. 1986;31(6):1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(86)90217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kulkarni PS, Srinivasan BD. Cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways in anterior uvea and conjunctiva. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;312:39–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujimori K, Kanaoka Y, Sakaguchi Y, Urade Y. Transcriptional activation of the human hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase gene in megakaryoblastic cells. Roles of the oct-1 element in the 5′-flanking region and the AP-2 element in the untranslated exon 1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(51):40511–40516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007688200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin SW, Seo CY, Han H, et al. 15d-PGJ2 induces apoptosis by reactive oxygen species-mediated inactivation of Akt in leukemia and colorectal cancer cells and shows in vivo antitumor activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(17):5414–5425. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim DH, Kim EH, Na HK, Sun Y, Surh YJ. 15-Deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2) stabilizes, but functionally inactivates p53 by binding to the cysteine 277 residue. Oncogene. 2010;29(17):2560–2576. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.