Abstract

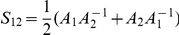

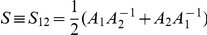

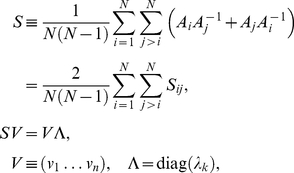

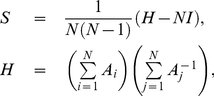

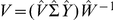

The number of high-dimensional datasets recording multiple aspects of a single phenomenon is increasing in many areas of science, accompanied by a need for mathematical frameworks that can compare multiple large-scale matrices with different row dimensions. The only such framework to date, the generalized singular value decomposition (GSVD), is limited to two matrices. We mathematically define a higher-order GSVD (HO GSVD) for N≥2 matrices  , each with full column rank. Each matrix is exactly factored as Di = UiΣiVT, where V, identical in all factorizations, is obtained from the eigensystem SV = VΛ of the arithmetic mean S of all pairwise quotients

, each with full column rank. Each matrix is exactly factored as Di = UiΣiVT, where V, identical in all factorizations, is obtained from the eigensystem SV = VΛ of the arithmetic mean S of all pairwise quotients  of the matrices

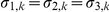

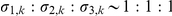

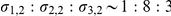

of the matrices  , i≠j. We prove that this decomposition extends to higher orders almost all of the mathematical properties of the GSVD. The matrix S is nondefective with V and Λ real. Its eigenvalues satisfy λk≥1. Equality holds if and only if the corresponding eigenvector vk is a right basis vector of equal significance in all matrices Di and Dj, that is σi,k/σj,k = 1 for all i and j, and the corresponding left basis vector ui,k is orthogonal to all other vectors in Ui for all i. The eigenvalues λk = 1, therefore, define the “common HO GSVD subspace.” We illustrate the HO GSVD with a comparison of genome-scale cell-cycle mRNA expression from S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human. Unlike existing algorithms, a mapping among the genes of these disparate organisms is not required. We find that the approximately common HO GSVD subspace represents the cell-cycle mRNA expression oscillations, which are similar among the datasets. Simultaneous reconstruction in the common subspace, therefore, removes the experimental artifacts, which are dissimilar, from the datasets. In the simultaneous sequence-independent classification of the genes of the three organisms in this common subspace, genes of highly conserved sequences but significantly different cell-cycle peak times are correctly classified.

, i≠j. We prove that this decomposition extends to higher orders almost all of the mathematical properties of the GSVD. The matrix S is nondefective with V and Λ real. Its eigenvalues satisfy λk≥1. Equality holds if and only if the corresponding eigenvector vk is a right basis vector of equal significance in all matrices Di and Dj, that is σi,k/σj,k = 1 for all i and j, and the corresponding left basis vector ui,k is orthogonal to all other vectors in Ui for all i. The eigenvalues λk = 1, therefore, define the “common HO GSVD subspace.” We illustrate the HO GSVD with a comparison of genome-scale cell-cycle mRNA expression from S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human. Unlike existing algorithms, a mapping among the genes of these disparate organisms is not required. We find that the approximately common HO GSVD subspace represents the cell-cycle mRNA expression oscillations, which are similar among the datasets. Simultaneous reconstruction in the common subspace, therefore, removes the experimental artifacts, which are dissimilar, from the datasets. In the simultaneous sequence-independent classification of the genes of the three organisms in this common subspace, genes of highly conserved sequences but significantly different cell-cycle peak times are correctly classified.

Introduction

In many areas of science, especially in biotechnology, the number of high-dimensional datasets recording multiple aspects of a single phenomenon is increasing. This is accompanied by a fundamental need for mathematical frameworks that can compare multiple large-scale matrices with different row dimensions. For example, comparative analyses of global mRNA expression from multiple model organisms promise to enhance fundamental understanding of the universality and specialization of molecular biological mechanisms, and may prove useful in medical diagnosis, treatment and drug design [1]. Existing algorithms limit analyses to subsets of homologous genes among the different organisms, effectively introducing into the analysis the assumption that sequence and functional similarities are equivalent (e.g., [2]). However, it is well known that this assumption does not always hold, for example, in cases of nonorthologous gene displacement, when nonorthologous proteins in different organisms fulfill the same function [3]. For sequence-independent comparisons, mathematical frameworks are required that can distinguish and separate the similar from the dissimilar among multiple large-scale datasets tabulated as matrices with different row dimensions, corresponding to the different sets of genes of the different organisms. The only such framework to date, the generalized singular value decomposition (GSVD) [4]–[7], is limited to two matrices.

It was shown that the GSVD provides a mathematical framework for sequence-independent comparative modeling of DNA microarray data from two organisms, where the mathematical variables and operations represent biological reality [7], [8]. The variables, significant subspaces that are common to both or exclusive to either one of the datasets, correlate with cellular programs that are conserved in both or unique to either one of the organisms, respectively. The operation of reconstruction in the subspaces common to both datasets outlines the biological similarity in the regulation of the cellular programs that are conserved across the species. Reconstruction in the common and exclusive subspaces of either dataset outlines the differential regulation of the conserved relative to the unique programs in the corresponding organism. Recent experimental results [9] verify a computationally predicted genome-wide mode of regulation that correlates DNA replication origin activity with mRNA expression [10], [11], demonstrating that GSVD modeling of DNA microarray data can be used to correctly predict previously unknown cellular mechanisms.

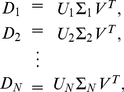

We now define a higher-order GSVD (HO GSVD) for the comparison of  datasets. The datasets are tabulated as

datasets. The datasets are tabulated as  real matrices

real matrices  , each with full column rank, with different row dimensions and the same column dimension, where there exists a one-to-one mapping among the columns of the matrices. Like the GSVD, the HO GSVD is an exact decomposition, i.e., each matrix is exactly factored as

, each with full column rank, with different row dimensions and the same column dimension, where there exists a one-to-one mapping among the columns of the matrices. Like the GSVD, the HO GSVD is an exact decomposition, i.e., each matrix is exactly factored as  , where the columns of

, where the columns of  and

and  have unit length and are the left and right basis vectors respectively, and each

have unit length and are the left and right basis vectors respectively, and each  is diagonal and positive definite. Like the GSVD, the matrix

is diagonal and positive definite. Like the GSVD, the matrix  is identical in all factorizations. In our HO GSVD, the matrix

is identical in all factorizations. In our HO GSVD, the matrix  is obtained from the eigensystem

is obtained from the eigensystem  of the arithmetic mean

of the arithmetic mean  of all pairwise quotients

of all pairwise quotients  of the matrices

of the matrices  , or equivalently of all

, or equivalently of all  ,

,  .

.

To clarify our choice of  , we note that in the GSVD, defined by Van Loan [5], the matrix

, we note that in the GSVD, defined by Van Loan [5], the matrix  can be formed from the eigenvectors of the unbalanced quotient

can be formed from the eigenvectors of the unbalanced quotient  (Section 1 in Appendix S1). We observe that this

(Section 1 in Appendix S1). We observe that this  can also be formed from the eigenvectors of the balanced arithmetic mean

can also be formed from the eigenvectors of the balanced arithmetic mean  . We prove that in the case of

. We prove that in the case of  , our definition of

, our definition of  by using the eigensystem of

by using the eigensystem of  leads algebraically to the GSVD (Theorems S1–S5 in Appendix S1), and therefore, as Paige and Saunders showed [6], can be computed in a stable way. We also note that in the GSVD, the matrix

leads algebraically to the GSVD (Theorems S1–S5 in Appendix S1), and therefore, as Paige and Saunders showed [6], can be computed in a stable way. We also note that in the GSVD, the matrix  does not depend upon the ordering of the matrices

does not depend upon the ordering of the matrices  and

and  . Therefore, we define our HO GSVD for

. Therefore, we define our HO GSVD for  matrices by using the balanced arithmetic mean

matrices by using the balanced arithmetic mean  of all pairwise arithmetic means

of all pairwise arithmetic means  , each of which defines the GSVD of the corresponding pair of matrices

, each of which defines the GSVD of the corresponding pair of matrices  and

and  , noting that

, noting that  does not depend upon the ordering of the matrices

does not depend upon the ordering of the matrices  and

and  .

.

We prove that  is nondefective (it has

is nondefective (it has  independent eigenvectors), and that its eigensystem is real (Theorem 1). We prove that the eigenvalues of

independent eigenvectors), and that its eigensystem is real (Theorem 1). We prove that the eigenvalues of  satisfy

satisfy  (Theorem 2). As in our GSVD comparison of two matrices [7], we interpret the

(Theorem 2). As in our GSVD comparison of two matrices [7], we interpret the  th diagonal of

th diagonal of  in the factorization of the

in the factorization of the  th matrix

th matrix  as indicating the significance of the

as indicating the significance of the  th right basis vector

th right basis vector  in

in  in terms of the overall information that

in terms of the overall information that  captures in

captures in  . The ratio

. The ratio  indicates the significance of

indicates the significance of  in

in  relative to its significance in

relative to its significance in  . We prove that an eigenvalue of

. We prove that an eigenvalue of  satisfies

satisfies  if and only if the corresponding eigenvector

if and only if the corresponding eigenvector  is a right basis vector of equal significance in all

is a right basis vector of equal significance in all  and

and  , that is,

, that is,  for all

for all  and

and  , and the corresponding left basis vector

, and the corresponding left basis vector  is orthonormal to all other vectors in

is orthonormal to all other vectors in  for all

for all  . We therefore mathematically define, in analogy with the GSVD, the “common HO GSVD subspace” of the

. We therefore mathematically define, in analogy with the GSVD, the “common HO GSVD subspace” of the  matrices to be the subspace spanned by the right basis vectors

matrices to be the subspace spanned by the right basis vectors  that correspond to the

that correspond to the  eigenvalues of

eigenvalues of  (Theorem 3). We also show that each of the right basis vectors

(Theorem 3). We also show that each of the right basis vectors  that span the common HO GSVD subspace is a generalized singular vector of all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices

that span the common HO GSVD subspace is a generalized singular vector of all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices  and

and  with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all

with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all  and

and  (Corollary 1).

(Corollary 1).

Recent research showed that several higher-order generalizations are possible for a given matrix decomposition, each preserving some but not all of the properties of the matrix decomposition [12]–[14] (see also Theorem S6 and Conjecture S1 in Appendix S1). Our new HO GSVD extends to higher orders all of the mathematical properties of the GSVD except for complete column-wise orthogonality of the left basis vectors that form the matrix  for all

for all  , i.e., in each factorization.

, i.e., in each factorization.

We illustrate the HO GSVD with a comparison of cell-cycle mRNA expression from S. pombe [15], [16], S. cerevisiae [17] and human [18]. Unlike existing algorithms, a mapping among the genes of these disparate organisms is not required (Section 2 in Appendix S1). We find that the common HO GSVD subspace represents the cell-cycle mRNA expression oscillations, which are similar among the datasets. Simultaneous reconstruction in this common subspace, therefore, removes the experimental artifacts, which are dissimilar, from the datasets. Simultaneous sequence-independent classification of the genes of the three organisms in the common subspace is in agreement with previous classifications into cell-cycle phases [19]. Notably, genes of highly conserved sequences across the three organisms [20], [21] but significantly different cell-cycle peak times, such as genes from the ABC transporter superfamily [22]–[28], phospholipase B-encoding genes [29], [30] and even the B cyclin-encoding genes [31], [32], are correctly classified.

Methods

HO GSVD Construction

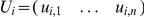

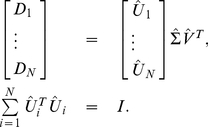

Suppose we have a set of  real matrices

real matrices  each with full column rank. We define a HO GSVD of these

each with full column rank. We define a HO GSVD of these  matrices as

matrices as

|

(1) |

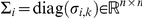

where each  is composed of normalized left basis vectors, each

is composed of normalized left basis vectors, each  is diagonal with

is diagonal with  , and

, and  , identical in all matrix factorizations, is composed of normalized right basis vectors. As in the GSVD comparison of global mRNA expression from two organisms [7], in the HO GSVD comparison of global mRNA expression from

, identical in all matrix factorizations, is composed of normalized right basis vectors. As in the GSVD comparison of global mRNA expression from two organisms [7], in the HO GSVD comparison of global mRNA expression from  organisms, the shared right basis vectors

organisms, the shared right basis vectors  of Equation (1) are the “genelets” and the

of Equation (1) are the “genelets” and the  sets of left basis vectors

sets of left basis vectors  are the

are the  sets of “arraylets” (Figure 1 and Section 2 in Appendix S1). We obtain

sets of “arraylets” (Figure 1 and Section 2 in Appendix S1). We obtain  from the eigensystem of

from the eigensystem of  , the arithmetic mean of all pairwise quotients

, the arithmetic mean of all pairwise quotients  of the matrices

of the matrices  , or equivalently of all

, or equivalently of all  ,

,  :

:

|

(2) |

with  . We prove that

. We prove that  is nondefective, i.e.,

is nondefective, i.e.,  has

has  independent eigenvectors, and that its eigenvectors

independent eigenvectors, and that its eigenvectors  and eigenvalues

and eigenvalues  are real (Theorem 1). We prove that the eigenvalues of

are real (Theorem 1). We prove that the eigenvalues of  satisfy

satisfy  (Theorem 2).

(Theorem 2).

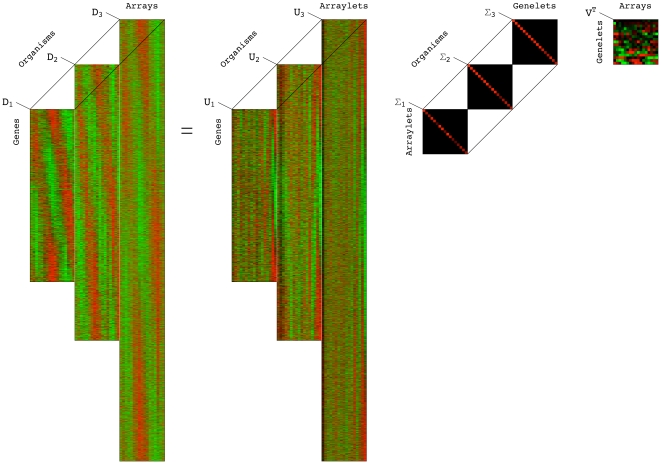

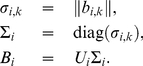

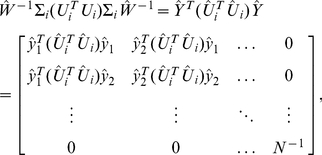

Figure 1. Higher-order generalized singular value decomposition (HO GSVD).

In this raster display of Equation (1) with overexpression (red), no change in expression (black), and underexpression (green) centered at gene- and array-invariant expression, the S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human global mRNA expression datasets are tabulated as organism-specific genes 17-arrays matrices

17-arrays matrices  ,

,  and

and  . The underlying assumption is that there exists a one-to-one mapping among the 17 columns of the three matrices but not necessarily among their rows. These matrices are transformed to the reduced diagonalized matrices

. The underlying assumption is that there exists a one-to-one mapping among the 17 columns of the three matrices but not necessarily among their rows. These matrices are transformed to the reduced diagonalized matrices  ,

,  and

and  , each of 17-“arraylets,” i.e., left basis vectors

, each of 17-“arraylets,” i.e., left basis vectors 17-“genelets,” i.e., right basis vectors, by using the organism-specific genes

17-“genelets,” i.e., right basis vectors, by using the organism-specific genes 17-arraylets transformation matrices

17-arraylets transformation matrices  ,

,  and

and  and the shared 17-genelets

and the shared 17-genelets 17-arrays transformation matrix

17-arrays transformation matrix  . We prove that with our particular

. We prove that with our particular  of Equations (2)–(4), this decomposition extends to higher orders all of the mathematical properties of the GSVD except for complete column-wise orthogonality of the arraylets, i.e., left basis vectors that form the matrices

of Equations (2)–(4), this decomposition extends to higher orders all of the mathematical properties of the GSVD except for complete column-wise orthogonality of the arraylets, i.e., left basis vectors that form the matrices  ,

,  and

and  . We therefore mathematically define, in analogy with the GSVD, the “common HO GSVD subspace” of the

. We therefore mathematically define, in analogy with the GSVD, the “common HO GSVD subspace” of the  matrices to be the subspace spanned by the genelets, i.e., right basis vectors

matrices to be the subspace spanned by the genelets, i.e., right basis vectors  that correspond to higher-order generalized singular values that are equal,

that correspond to higher-order generalized singular values that are equal,  , where, as we prove, the corresponding arraylets, i.e., the left basis vectors

, where, as we prove, the corresponding arraylets, i.e., the left basis vectors  ,

,  and

and  , are orthonormal to all other arraylets in

, are orthonormal to all other arraylets in  ,

,  and

and  . We show that like the GSVD for two organisms [7], the HO GSVD provides a sequence-independent comparative mathematical framework for datasets from more than two organisms, where the mathematical variables and operations represent biological reality: Genelets of common significance in the multiple datasets, and the corresponding arraylets, represent cell-cycle checkpoints or transitions from one phase to the next, common to S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human. Simultaneous reconstruction and classification of the three datasets in the common subspace that these patterns span outline the biological similarity in the regulation of their cell-cycle programs. Notably, genes of significantly different cell-cycle peak times [19] but highly conserved sequences [20], [21] are correctly classified.

. We show that like the GSVD for two organisms [7], the HO GSVD provides a sequence-independent comparative mathematical framework for datasets from more than two organisms, where the mathematical variables and operations represent biological reality: Genelets of common significance in the multiple datasets, and the corresponding arraylets, represent cell-cycle checkpoints or transitions from one phase to the next, common to S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human. Simultaneous reconstruction and classification of the three datasets in the common subspace that these patterns span outline the biological similarity in the regulation of their cell-cycle programs. Notably, genes of significantly different cell-cycle peak times [19] but highly conserved sequences [20], [21] are correctly classified.

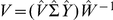

Given  , we compute matrices

, we compute matrices  by solving

by solving  linear systems:

linear systems:

| (3) |

and we construct  and

and  by normalizing the columns of

by normalizing the columns of  :

:

|

(4) |

HO GSVD Interpretation

In this construction, the rows of each of the  matrices

matrices  are superpositions of the same right basis vectors, the columns of

are superpositions of the same right basis vectors, the columns of  (Figures S1 and S2 and Section 1 in Appendix S1). As in our GSVD comparison of two matrices, we interpret the

(Figures S1 and S2 and Section 1 in Appendix S1). As in our GSVD comparison of two matrices, we interpret the  th diagonals of

th diagonals of  , the “higher-order generalized singular value set”

, the “higher-order generalized singular value set”  , as indicating the significance of the

, as indicating the significance of the  th right basis vector

th right basis vector  in the matrices

in the matrices  , and reflecting the overall information that

, and reflecting the overall information that  captures in each

captures in each  respectively. The ratio

respectively. The ratio  indicates the significance of

indicates the significance of  in

in  relative to its significance in

relative to its significance in  . A ratio of

. A ratio of  for all

for all  and

and  corresponds to a right basis vector

corresponds to a right basis vector  of equal significance in all

of equal significance in all  matrices

matrices  . GSVD comparisons of two matrices showed that right basis vectors of approximately equal significance in the two matrices reflect themes that are common to both matrices under comparison [7]. A ratio of

. GSVD comparisons of two matrices showed that right basis vectors of approximately equal significance in the two matrices reflect themes that are common to both matrices under comparison [7]. A ratio of  indicates a basis vector

indicates a basis vector  of almost negligible significance in

of almost negligible significance in  relative to its significance in

relative to its significance in  . GSVD comparisons of two matrices showed that right basis vectors of negligible significance in one matrix reflect themes that are exclusive to the other matrix.

. GSVD comparisons of two matrices showed that right basis vectors of negligible significance in one matrix reflect themes that are exclusive to the other matrix.

We prove that an eigenvalue of  satisfies

satisfies  if and only if the corresponding eigenvector

if and only if the corresponding eigenvector  is a right basis vector of equal significance in all

is a right basis vector of equal significance in all  and

and  , that is,

, that is,  for all

for all  and

and  , and the corresponding left basis vector

, and the corresponding left basis vector  is orthonormal to all other vectors in

is orthonormal to all other vectors in  for all

for all  . We therefore mathematically define, in analogy with the GSVD, the “common HO GSVD subspace” of the

. We therefore mathematically define, in analogy with the GSVD, the “common HO GSVD subspace” of the  matrices to be the subspace spanned by the right basis vectors

matrices to be the subspace spanned by the right basis vectors  corresponding to the eigenvalues of

corresponding to the eigenvalues of  that satisfy

that satisfy  (Theorem 3).

(Theorem 3).

It follows that each of the right basis vectors  that span the common HO GSVD subspace is a generalized singular vector of all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices

that span the common HO GSVD subspace is a generalized singular vector of all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices  and

and  with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all

with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all  and

and  (Corollary 1). Since the GSVD can be computed in a stable way [6], we note that the common HO GSVD subspace can also be computed in a stable way by computing all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices

(Corollary 1). Since the GSVD can be computed in a stable way [6], we note that the common HO GSVD subspace can also be computed in a stable way by computing all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices  and

and  . This also suggests that it may be possible to formulate the HO GSVD as a solution to an optimization problem, in analogy with existing variational formulations of the GSVD [33]. Such a formulation may lead to a stable numerical algorithm for computing the HO GSVD, and possibly also to a higher-order general Gauss-Markov linear statistical model [34]–[36].

. This also suggests that it may be possible to formulate the HO GSVD as a solution to an optimization problem, in analogy with existing variational formulations of the GSVD [33]. Such a formulation may lead to a stable numerical algorithm for computing the HO GSVD, and possibly also to a higher-order general Gauss-Markov linear statistical model [34]–[36].

We show, in a comparison of  matrices, that the approximately common HO GSVD subspace of these three matrices reflects a theme that is common to the three matrices under comparison (Section 2).

matrices, that the approximately common HO GSVD subspace of these three matrices reflects a theme that is common to the three matrices under comparison (Section 2).

HO GSVD Mathematical Properties

Theorem 1

is nondefective (it has

is nondefective (it has

independent eigenvectors) and its eigensystem is real.

independent eigenvectors) and its eigensystem is real.

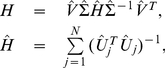

Proof. From Equation (2) it follows that

|

(5) |

and the eigenvectors of  equal the eigenvectors of

equal the eigenvectors of  .

.

Let the SVD of the matrices  appended along the

appended along the  -columns axis be

-columns axis be

|

(6) |

Since the matrices  are real and with full column rank, it follows from the SVD of

are real and with full column rank, it follows from the SVD of  that the symmetric matrices

that the symmetric matrices  are real and positive definite, and their inverses exist. It then follows from Equations (5) and (6) that

are real and positive definite, and their inverses exist. It then follows from Equations (5) and (6) that  is similar to

is similar to  ,

,

|

(7) |

and the eigenvalues of  equal the eigenvalues of

equal the eigenvalues of  .

.

A sum of real, symmetric and positive definite matrices,  is also real, symmetric and positive definite; therefore, its eigensystem

is also real, symmetric and positive definite; therefore, its eigensystem

| (8) |

is real with  orthogonal and

orthogonal and  . Without loss of generality let

. Without loss of generality let  be orthonormal, such that

be orthonormal, such that  . It follows from the similarity of

. It follows from the similarity of  with

with  that the eigensystem of

that the eigensystem of  can be written as

can be written as  , with the real and nonsingular

, with the real and nonsingular  , where

, where  and

and  such that

such that  for all

for all  .

.

Thus, from Equation (5),  is nondefective with real eigenvectors

is nondefective with real eigenvectors  . Also, the eigenvalues of

. Also, the eigenvalues of  satisfy

satisfy

| (9) |

where  are the eigenvalues of

are the eigenvalues of  and

and  . Thus, the eigenvalues of

. Thus, the eigenvalues of  are real. □

are real. □

Theorem 2

The eigenvalues of

satisfy

satisfy

.

.

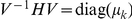

Proof. Following Equation (9), asserting that the eigenvalues of  satisfy

satisfy  is equivalent to asserting that the eigenvalues of

is equivalent to asserting that the eigenvalues of  satisfy

satisfy  .

.

From Equations (6) and (7), the eigenvalues of  satisfy

satisfy

| (10) |

under the constraint that

| (11) |

where  is a real unit vector, and where it follows from the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality [37] (see also [4], [34], [38]) for the real nonzero vectors

is a real unit vector, and where it follows from the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality [37] (see also [4], [34], [38]) for the real nonzero vectors  and

and  that for all

that for all

| (12) |

With the constraint of Equation (11), which requires the sum of the  positive numbers

positive numbers  to equal one, the lower bound on the eigenvalues of

to equal one, the lower bound on the eigenvalues of  in Equation (10) is at its minimum when the sum of the inverses of these numbers is at its minimum, that is, when the numbers equal

in Equation (10) is at its minimum when the sum of the inverses of these numbers is at its minimum, that is, when the numbers equal

| (13) |

for all  and

and  . Thus, the eigenvalues of

. Thus, the eigenvalues of  satisfy

satisfy  . □

. □

Theorem 3

The common HO GSVD subspace.

An eigenvalue of

satisfies

satisfies

if and only if the corresponding eigenvector

if and only if the corresponding eigenvector

is a right basis vector of equal significance in all

is a right basis vector of equal significance in all

and

and

, that is,

, that is,

for all

for all

and

and

, and the corresponding left basis vector

, and the corresponding left basis vector

is orthonormal to all other vectors in

is orthonormal to all other vectors in

for all

for all

. The “common HO GSVD subspace” of the

. The “common HO GSVD subspace” of the

matrices is, therefore, the subspace spanned by the right basis vectors

matrices is, therefore, the subspace spanned by the right basis vectors

corresponding to the eigenvalues of

corresponding to the eigenvalues of

that satisfy

that satisfy

.

.

Proof. Without loss of generality, let  . From Equation (12) and the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, an eigenvalue of

. From Equation (12) and the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, an eigenvalue of  equals its minimum lower bound

equals its minimum lower bound  if and only if the corresponding eigenvector

if and only if the corresponding eigenvector  is also an eigenvector of

is also an eigenvector of  for all

for all  [37], where, from Equation (13), the corresponding eigenvalue equals

[37], where, from Equation (13), the corresponding eigenvalue equals  ,

,

| (14) |

Given the eigenvectors  of

of  , we solve Equation (3) for each

, we solve Equation (3) for each  of Equation (6), and obtain

of Equation (6), and obtain

| (15) |

Following Equations (14) and (15), where  corresponds to a minimum eigenvalue

corresponds to a minimum eigenvalue  , and since

, and since  is orthonormal, we obtain

is orthonormal, we obtain

|

(16) |

with zeroes in the  th row and the

th row and the  th column of the matrix above everywhere except for the diagonal element. Thus, an eigenvalue of

th column of the matrix above everywhere except for the diagonal element. Thus, an eigenvalue of  satisfies

satisfies  if and only if the corresponding left basis vectors

if and only if the corresponding left basis vectors  are orthonormal to all other vectors in

are orthonormal to all other vectors in  .

.

The corresponding higher-order generalized singular values are  . Thus

. Thus  for all

for all  and

and  , and the corresponding right basis vector

, and the corresponding right basis vector  is of equal significance in all matrices

is of equal significance in all matrices  and

and  . □

. □

Corollary 1

An eigenvalue of

satisfies

satisfies

if and only if the corresponding right basis vector

if and only if the corresponding right basis vector

is a generalized singular vector of all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices

is a generalized singular vector of all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices

and

and

with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all

with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all

and

and

.

.

Proof. From Equations (12) and (13), and since the pairwise quotients  are similar to

are similar to  with the similarity transformation of

with the similarity transformation of  for all

for all  and

and  , it follows that an eigenvalue of

, it follows that an eigenvalue of  satisfies

satisfies  if and only if the corresponding right basis vector

if and only if the corresponding right basis vector  is also an eigenvector of each of the pairwise quotients

is also an eigenvector of each of the pairwise quotients  of the matrices

of the matrices  with equal corresponding eigenvalues, or equivalently of all

with equal corresponding eigenvalues, or equivalently of all  with all eigenvalues at their minimum of one,

with all eigenvalues at their minimum of one,

| (17) |

We prove (Theorems S1–S5 in Appendix S1) that in the case of  matrices our definition of

matrices our definition of  by using the eigensystem of

by using the eigensystem of  leads algebraically to the GSVD, where an eigenvalue of

leads algebraically to the GSVD, where an eigenvalue of  equals its minimum of one if and only if the two corresponding generalized singular values are equal, such that the corresponding generalized singular vector

equals its minimum of one if and only if the two corresponding generalized singular values are equal, such that the corresponding generalized singular vector  is of equal significance in both matrices

is of equal significance in both matrices  and

and  . Thus, it follows that each of the right basis vectors

. Thus, it follows that each of the right basis vectors  that span the common HO GSVD subspace is a generalized singular vector of all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices

that span the common HO GSVD subspace is a generalized singular vector of all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices  and

and  with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all

with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all  and

and  . □

. □

Note that since the GSVD can be computed in a stable way [6], the common HO GSVD subspace we define (Theorem 3) can also be computed in a stable way by computing all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices  and

and  (Corollary 1). It may also be possible to formulate the HO GSVD as a solution to an optimization problem, in analogy with existing variational formulations of the GSVD [33]. Such a formulation may lead to a stable numerical algorithm for computing the HO GSVD, and possibly also to a higher-order general Gauss-Markov linear statistical model [34]–[36].

(Corollary 1). It may also be possible to formulate the HO GSVD as a solution to an optimization problem, in analogy with existing variational formulations of the GSVD [33]. Such a formulation may lead to a stable numerical algorithm for computing the HO GSVD, and possibly also to a higher-order general Gauss-Markov linear statistical model [34]–[36].

Results

HO GSVD Comparison of Global mRNA Expression from Three Organisms

Consider now the HO GSVD comparative analysis of global mRNA expression datasets from the  organisms S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human (Section 2.1 in Appendix S1, Mathematica Notebooks S1 and S2, and Datasets S1, S2 and S3). The datasets are tabulated as matrices of

organisms S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human (Section 2.1 in Appendix S1, Mathematica Notebooks S1 and S2, and Datasets S1, S2 and S3). The datasets are tabulated as matrices of  columns each, corresponding to DNA microarray-measured mRNA expression from each organism at

columns each, corresponding to DNA microarray-measured mRNA expression from each organism at  time points equally spaced during approximately two cell-cycle periods. The underlying assumption is that there exists a one-to-one mapping among the 17 columns of the three matrices but not necessarily among their rows, which correspond to either

time points equally spaced during approximately two cell-cycle periods. The underlying assumption is that there exists a one-to-one mapping among the 17 columns of the three matrices but not necessarily among their rows, which correspond to either  -S. pombe genes,

-S. pombe genes,  -S. cerevisiae genes or

-S. cerevisiae genes or  -human genes. The HO GSVD of Equation (1) transforms the datasets from the organism-specific genes

-human genes. The HO GSVD of Equation (1) transforms the datasets from the organism-specific genes

-arrays spaces to the reduced spaces of the 17-“arraylets,” i.e., left basis vactors

-arrays spaces to the reduced spaces of the 17-“arraylets,” i.e., left basis vactors 17-“genelets,” i.e., right basis vectors, where the datasets

17-“genelets,” i.e., right basis vectors, where the datasets  are represented by the diagonal nonnegative matrices

are represented by the diagonal nonnegative matrices  , by using the organism-specific genes

, by using the organism-specific genes 17-arraylets transformation matrices

17-arraylets transformation matrices  and the one shared 17-genelets

and the one shared 17-genelets 17-arrays transformation matrix

17-arrays transformation matrix  (Figure 1).

(Figure 1).

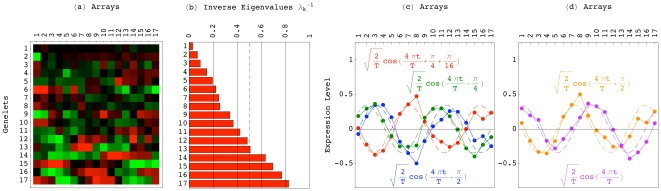

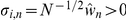

Following Theorem 3, the approximately common HO GSVD subspace of the three datasets is spanned by the five genelets  that correspond to

that correspond to  . We find that these five genelets are approximately equally significant with

. We find that these five genelets are approximately equally significant with  in the S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human datasets, respectively (Figure 2 a and b

). The five corresponding arraylets in each dataset are

in the S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human datasets, respectively (Figure 2 a and b

). The five corresponding arraylets in each dataset are  -orthonormal to all other arraylets (Figure S3 in Appendix S1).

-orthonormal to all other arraylets (Figure S3 in Appendix S1).

Figure 2. Genelets or right basis vectors.

(a) Raster display of the expression of the 17 genelets, i.e., HO GSVD patterns of expression variation across time, with overexpression (red), no change in expression (black) and underexpression (green) around the array-, i.e., time-invariant expression. (b) Bar chart of the corresponding inverse eigenvalues  , showing that the 13th through the 17th genelets correspond to

, showing that the 13th through the 17th genelets correspond to  . (c) Line-joined graphs of the 13th (red), 14th (blue) and 15th (green) genelets in the two-dimensional subspace that approximates the five-dimensional HO GSVD subspace (Figure S4 and Section 2.4), normalized to zero average and unit variance. (d) Line-joined graphs of the projected 16th (orange) and 17th (violet) genelets in the two-dimensional subspace. The five genelets describe expression oscillations of two periods in the three time courses.

. (c) Line-joined graphs of the 13th (red), 14th (blue) and 15th (green) genelets in the two-dimensional subspace that approximates the five-dimensional HO GSVD subspace (Figure S4 and Section 2.4), normalized to zero average and unit variance. (d) Line-joined graphs of the projected 16th (orange) and 17th (violet) genelets in the two-dimensional subspace. The five genelets describe expression oscillations of two periods in the three time courses.

Common HO GSVD Subspace Represents Similar Cell-Cycle Oscillations

The expression variations across time of the five genelets that span the approximately common HO GSVD subspace fit normalized cosine functions of two periods, superimposed on time-invariant expression (Figure 2 c and d

). Consistently, the corresponding organism-specific arraylets are enriched [39] in overexpressed or underexpressed organism-specific cell cycle-regulated genes, with 24 of the 30 P-values  (Table 1 and Section 2.2 in Appendix S1). For example, the three 17th arraylets, which correspond to the 0-phase 17th genelet, are enriched in overexpressed G2 S. pombe genes, G2/M and M/G1 S. cerevisiae genes and S and G2 human genes, respectively, representing the cell-cycle checkpoints in which the three cultures are initially synchronized.

(Table 1 and Section 2.2 in Appendix S1). For example, the three 17th arraylets, which correspond to the 0-phase 17th genelet, are enriched in overexpressed G2 S. pombe genes, G2/M and M/G1 S. cerevisiae genes and S and G2 human genes, respectively, representing the cell-cycle checkpoints in which the three cultures are initially synchronized.

Table 1. Arraylets or left basis vectors.

| Overexpression | Underexpression | ||||

| Dataset | Arraylet | Annotation | P-value | Annotation | P-value |

| S. pombe | 13 | G2 |

|

G1 |

|

| 14 | M |

|

G2 |

|

|

| 15 | M |

|

S |

|

|

| 16 | G2 |

|

G1 |

|

|

| 17 | G2 |

|

S |

|

|

| S. cerevisiae | 13 | S/G2 |

|

M/G1 |

|

| 14 | M/G1 |

|

G2/M |

|

|

| 15 | G1 |

|

S |

|

|

| 16 | G2/M |

|

G1 |

|

|

| 17 | G2/M |

|

G1 |

|

|

| Human | 13 | G1/S |

|

G2 |

|

| 14 | M/G1 |

|

G2 |

|

|

| 15 | G2 |

|

None |

|

|

| 16 | G1/S |

|

G2 |

|

|

| 17 | G2 |

|

M/G1 |

|

|

Probabilistic significance of the enrichment of the arraylets, i.e., HO GSVD patterns of expression variation across the S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human genes, that span the common HO GSVD subspace in each dataset, in over- or underexpressed cell cycle-regulated genes. The P-value of each enrichment is calculated as described [39] (Section 2.2 in Appendix S1) assuming hypergeometric distribution of the annotations (Datasets S1, S2, S3) among the genes, including the  = 100 genes most over- or underexpressed in each arraylet.

= 100 genes most over- or underexpressed in each arraylet.

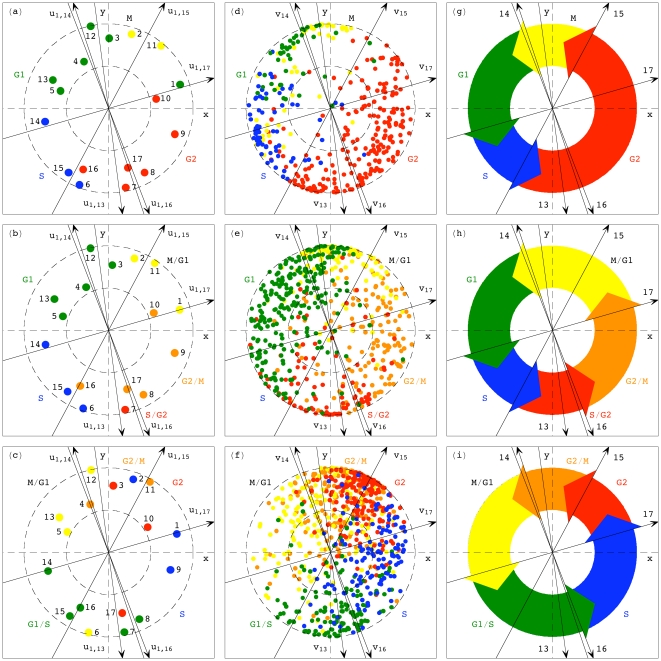

Simultaneous sequence-independent reconstruction and classification of the three datasets in the common subspace outline cell-cycle progression in time and across the genes in the three organisms (Sections 2.3 and 2.4 in Appendix S1). Projecting the expression of the 17 arrays of either organism from the corresponding five-dimensional arraylets subspace onto the two-dimensional subspace that approximates it (Figure S4 in Appendix S1),  of the contributions of the arraylets add up, rather than cancel out (Figure 3 a–c

). In these two-dimensional subspaces, the angular order of the arrays of either organism describes cell-cycle progression in time through approximately two cell-cycle periods, from the initial cell-cycle phase and back to that initial phase twice. Projecting the expression of the genes,

of the contributions of the arraylets add up, rather than cancel out (Figure 3 a–c

). In these two-dimensional subspaces, the angular order of the arrays of either organism describes cell-cycle progression in time through approximately two cell-cycle periods, from the initial cell-cycle phase and back to that initial phase twice. Projecting the expression of the genes,  of the contributions of the five genelets add up in the overall expression of 343 of the 380 S. pombe genes classified as cell cycle-regulated, 554 of the 641 S. cerevisiae cell-cycle genes, and 632 of the 787 human cell-cycle genes (Figure 3 d–f

). Simultaneous classification of the genes of either organism into cell-cycle phases according to their angular order in these two-dimensional subspaces is consistent with the classification of the arrays, and is in good agreement with the previous classifications of the genes (Figure 3 g–i

). With all 3167 S. pombe, 4772 S. cerevisiae and 13,068 human genes sorted, the expression variations of the five arraylets from each organism approximately fit one-period cosines, with the initial phase of each arraylet (Figures S5, S6, S7 in Appendix S1) similar to that of its corresponding genelet (Figure 2). The global mRNA expression of each organism, reconstructed in the common HO GSVD subspace, approximately fits a traveling wave, oscillating across time and across the genes.

of the contributions of the five genelets add up in the overall expression of 343 of the 380 S. pombe genes classified as cell cycle-regulated, 554 of the 641 S. cerevisiae cell-cycle genes, and 632 of the 787 human cell-cycle genes (Figure 3 d–f

). Simultaneous classification of the genes of either organism into cell-cycle phases according to their angular order in these two-dimensional subspaces is consistent with the classification of the arrays, and is in good agreement with the previous classifications of the genes (Figure 3 g–i

). With all 3167 S. pombe, 4772 S. cerevisiae and 13,068 human genes sorted, the expression variations of the five arraylets from each organism approximately fit one-period cosines, with the initial phase of each arraylet (Figures S5, S6, S7 in Appendix S1) similar to that of its corresponding genelet (Figure 2). The global mRNA expression of each organism, reconstructed in the common HO GSVD subspace, approximately fits a traveling wave, oscillating across time and across the genes.

Figure 3. Common HO GSVD subspace represents similar cell-cycle oscillations.

(a–c) S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human array expression, projected from the five-dimensional common HO GSVD subspace onto the two-dimensional subspace that approximates it (Sections 2.3 and 2.4 in Appendix S1). The arrays are color-coded according to their previous cell-cycle classification [15]–[18]. The arrows describe the projections of the  arraylets of each dataset. The dashed unit and half-unit circles outline 100% and 50% of added-up (rather than canceled-out) contributions of these five arraylets to the overall projected expression. (d–f) Expression of 380, 641 and 787 cell cycle-regulated genes of S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human, respectively, color-coded according to previous classifications. (g–i) The HO GSVD pictures of the S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human cell-cycle programs. The arrows describe the projections of the

arraylets of each dataset. The dashed unit and half-unit circles outline 100% and 50% of added-up (rather than canceled-out) contributions of these five arraylets to the overall projected expression. (d–f) Expression of 380, 641 and 787 cell cycle-regulated genes of S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human, respectively, color-coded according to previous classifications. (g–i) The HO GSVD pictures of the S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human cell-cycle programs. The arrows describe the projections of the  shared genelets and organism-specific arraylets that span the common HO GSVD subspace and represent cell-cycle checkpoints or transitions from one phase to the next.

shared genelets and organism-specific arraylets that span the common HO GSVD subspace and represent cell-cycle checkpoints or transitions from one phase to the next.

Note also that simultaneous reconstruction in the common HO GSVD subspace removes the experimental artifacts and batch effects, which are dissimilar, from the three datasets. Consider, for example, the second genelet. With  in the S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human datasets, respectively, this genelet is almost exclusive to the S. cerevisiae dataset. This genelet is anticorrelated with a time decaying pattern of expression (Figure 2a

). Consistently, the corresponding S. cerevisiae-specific arraylet is enriched in underexpressed S. cerevisiae genes that were classified as up-regulated by the S. cerevisiae synchronizing agent, the

in the S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human datasets, respectively, this genelet is almost exclusive to the S. cerevisiae dataset. This genelet is anticorrelated with a time decaying pattern of expression (Figure 2a

). Consistently, the corresponding S. cerevisiae-specific arraylet is enriched in underexpressed S. cerevisiae genes that were classified as up-regulated by the S. cerevisiae synchronizing agent, the  -factor pheromone, with the P-value

-factor pheromone, with the P-value  . Reconstruction in the common subspace effectively removes this S. cerevisiae-approximately exclusive pattern of expression variation from the three datasets.

. Reconstruction in the common subspace effectively removes this S. cerevisiae-approximately exclusive pattern of expression variation from the three datasets.

Simultaneous HO GSVD Classification of Homologous Genes of Different Cell-Cycle Peak Times

Notably, in the simultaneous sequence-independent classification of the genes of the three organisms in the common subspace, genes of significantly different cell-cycle peak times [19] but highly conserved sequences [20], [21] are correctly classified (Section 2.5 in Appendix S1).

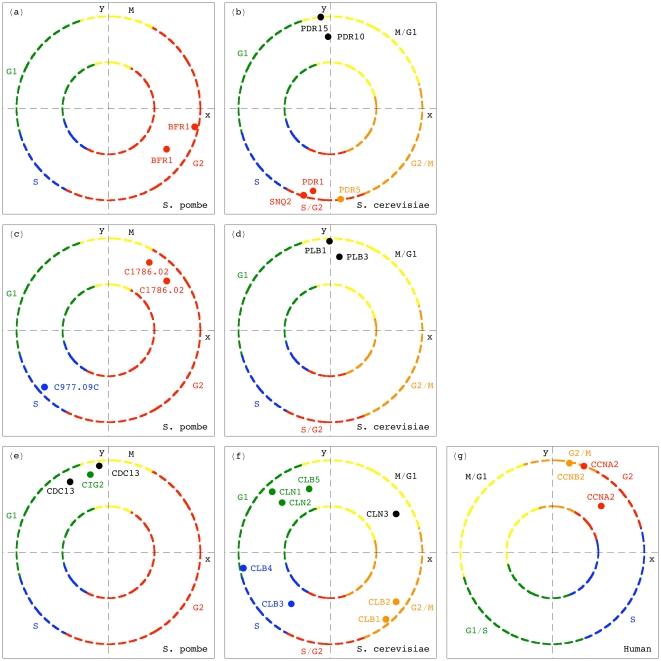

For example, consider the G2 S. pombe gene BFR1 (Figure 4a ), which belongs to the evolutionarily highly conserved ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily [22]. The closest homologs of BFR1 in our S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human datasets are the S. cerevisiae genes SNQ2, PDR5, PDR15 and PDR10 (Table S1a in Appendix S1). The expression of SNQ2 and PDR5 is known to peak at the S/G2 and G2/M cell-cycle phases, respectively [17]. However, sequence similarity does not imply similar cell-cycle peak times, and PDR15 and PDR10, the closest homologs of PDR5, are induced during stationary phase [23], which has been hypothesized to occur in G1, before the Cdc28-defined cell-cycle arrest [24]. Consistently, we find PDR15 and PDR10 at the M/G1 to G1 transition, antipodal to (i.e., half a cell-cycle period apart from) SNQ2 and PDR5, which are projected onto S/G2 and G2/M, respectively (Figure 4b ). We also find the transcription factor PDR1 at S/G2, its known cell-cycle peak time, adjacent to SNQ2 and PDR5, which it positively regulates and might be regulated by, and antipodal to PDR15, which it negatively regulates [25]–[28].

Figure 4. Simultaneous HO GSVD classification of homologous genes of different cell-cycle peak times.

(a) The S. pombe gene BFR1, and (b) its closest S. cerevisiae homologs. (c) The S. pombe and (d) S. cerevisiae closest homologs of the S. cerevisiae gene PLB1. (e) The S. pombe cyclin-encoding gene CIG2 and its closest S. pombe, (f) S. cerevisiae and (g) human homologs.

Another example is the S. cerevisiae phospholipase B-encoding gene PLB1 [29], which peaks at the cell-cycle phase M/G1 [30]. Its closest homolog in our S. cerevisiae dataset, PLB3, also peaks at M/G1 [17] (Figure 4d ). However, among the closest S. pombe and human homologs of PLB1 (Table S1b in Appendix S1), we find the S. pombe genes SPAC977.09c and SPAC1786.02, which expressions peak at the almost antipodal S. pombe cell-cycle phases S and G2, respectively [19] (Figure 4c ).

As a third example, consider the S. pombe G1 B-type cyclin-encoding gene CIG2 [31], [32] (Table S1c in Appendix S1). Its closest S. pombe homolog, CDC13, peaks at M [19] (Figure 4e ). The closest human homologs of CIG2, the cyclins CCNA2 and CCNB2, peak at G2 and G2/M, respectively (Figure 4g ). However, while periodicity in mRNA abundance levels through the cell cycle is highly conserved among members of the cyclin family, the cell-cycle peak times are not necessarily conserved [1]: The closest homologs of CIG2 in our S. cerevisiae dataset, are the G2/M promoter-encoding genes CLB1,2 and CLB3,4, which expressions peak at G2/M and S respectively, and CLB5, which encodes a DNA synthesis promoter, and peaks at G1 (Figure 4f ).

Discussion

We mathematically defined a higher-order GSVD (HO GSVD) for two or more large-scale matrices with different row dimensions and the same column dimension. We proved that our new HO GSVD extends to higher orders almost all of the mathematical properties of the GSVD: The eigenvalues of  are always greater than or equal to one, and an eigenvalue of one corresponds to a right basis vector of equal significance in all matrices, and to a left basis vector in each matrix factorization that is orthogonal to all other left basis vectors in that factorization. We therefore mathematically defined, in analogy with the GSVD, the common HO GSVD subspace of the

are always greater than or equal to one, and an eigenvalue of one corresponds to a right basis vector of equal significance in all matrices, and to a left basis vector in each matrix factorization that is orthogonal to all other left basis vectors in that factorization. We therefore mathematically defined, in analogy with the GSVD, the common HO GSVD subspace of the  matrices to be the subspace spanned by the right basis vectors that correspond to the eigenvalues of

matrices to be the subspace spanned by the right basis vectors that correspond to the eigenvalues of  that equal one.

that equal one.

The only property that does not extend to higher orders in general is the complete column-wise orthogonality of the normalized left basis vectors in each factorization. Recent research showed that several higher-order generalizations are possible for a given matrix decomposition, each preserving some but not all of the properties of the matrix decomposition [12]–[14]. The HO GSVD has the interesting property of preserving the exactness and diagonality of the matrix GSVD and, in special cases, also partial or even complete column-wise orthogonality. That is, all  matrix factorizations in Equation (1) are exact, all

matrix factorizations in Equation (1) are exact, all  matrices

matrices  are diagonal, and when one or more of the eigenvalues of

are diagonal, and when one or more of the eigenvalues of  equal one, the corresponding left basis vectors in each factorization are orthogonal to all other left basis vectors in that factorization.

equal one, the corresponding left basis vectors in each factorization are orthogonal to all other left basis vectors in that factorization.

The complete column-wise orthogonality of the matrix GSVD [5] enables its stable computation [6]. We showed that each of the right basis vectors that span the common HO GSVD subspace is a generalized singular vector of all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices  and

and  with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all

with equal corresponding generalized singular values for all  and

and  . Since the GSVD can be computed in a stable way, the common HO GSVD subspace can also be computed in a stable way by computing all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices

. Since the GSVD can be computed in a stable way, the common HO GSVD subspace can also be computed in a stable way by computing all pairwise GSVD factorizations of the matrices  and

and  . That is, the common HO GSVD subspace exists also for

. That is, the common HO GSVD subspace exists also for  matrices

matrices  that are not all of full column rank. This also means that the common HO GSVD subspace can be formulated as a solution to an optimization problem, in analogy with existing variational formulations of the GSVD [33].

that are not all of full column rank. This also means that the common HO GSVD subspace can be formulated as a solution to an optimization problem, in analogy with existing variational formulations of the GSVD [33].

It would be ideal if our procedure reduced to the stable computation of the matrix GSVD when  . To achieve this ideal, we would need to find a procedure that allows a computation of the HO GSVD, not just the common HO GSVD subspace, for

. To achieve this ideal, we would need to find a procedure that allows a computation of the HO GSVD, not just the common HO GSVD subspace, for  matrices

matrices  that are not all of full column rank. A formulation of the HO GSVD, not just the common HO GSVD subspace, as a solution to an optimization problem may lead to a stable numerical algorithm for computing the HO GSVD. Such a formulation may also lead to a higher-order general Gauss-Markov linear statistical model [34]–[36].

that are not all of full column rank. A formulation of the HO GSVD, not just the common HO GSVD subspace, as a solution to an optimization problem may lead to a stable numerical algorithm for computing the HO GSVD. Such a formulation may also lead to a higher-order general Gauss-Markov linear statistical model [34]–[36].

It was shown that the GSVD provides a mathematical framework for sequence-independent comparative modeling of DNA microarray data from two organisms, where the mathematical variables and operations represent experimental or biological reality [7], [8]. The variables, subspaces of significant patterns that are common to both or exclusive to either one of the datasets, correlate with cellular programs that are conserved in both or unique to either one of the organisms, respectively. The operation of reconstruction in the subspaces common to both datasets outlines the biological similarity in the regulation of the cellular programs that are conserved across the species. Reconstruction in the common and exclusive subspaces of either dataset outlines the differential regulation of the conserved relative to the unique programs in the corresponding organism. Recent experimental results [9] verify a computationally predicted genome-wide mode of regulation [10], [11], and demonstrate that GSVD modeling of DNA microarray data can be used to correctly predict previously unknown cellular mechanisms.

Here we showed, comparing global cell-cycle mRNA expression from the three disparate organisms S. pombe, S. cerevisiae and human, that the HO GSVD provides a sequence-independent comparative framework for two or more genomic datasets, where the variables and operations represent biological reality. The approximately common HO GSVD subspace represents the cell-cycle mRNA expression oscillations, which are similar among the datasets. Simultaneous reconstruction in the common subspace removes the experimental artifacts, which are dissimilar, from the datasets. In the simultaneous sequence-independent classification of the genes of the three organisms in this common subspace, genes of highly conserved sequences but significantly different cell-cycle peak times are correctly classified.

Additional possible applications of our HO GSVD in biotechnology include comparison of multiple genomic datasets, each corresponding to (i) the same experiment repeated multiple times using different experimental protocols, to separate the biological signal that is similar in all datasets from the dissimilar experimental artifacts; (ii) one of multiple types of genomic information, such as DNA copy number, DNA methylation and mRNA expression, collected from the same set of samples, e.g., tumor samples, to elucidate the molecular composition of the overall biological signal in these samples; (iii) one of multiple chromosomes of the same organism, to illustrate the relation, if any, between these chromosomes in terms of their, e.g., mRNA expression in a given set of samples; and (iv) one of multiple interacting organisms, e.g., in an ecosystem, to illuminate the exchange of biological information in these interactions.

Supporting Information

A PDF format file, readable by Adobe Acrobat Reader.

(PDF)

Higher-order generalized singular value decomposition (HO GSVD) of global mRNA expression datasets from three different organisms. A Mathematica 5.2 code file, executable by Mathematica 5.2 and readable by Mathematica Player, freely available at http://www.wolfram.com/products/player/.

(NB)

HO GSVD of global mRNA expression datasets from three different organisms. A PDF format file, readable by Adobe Acrobat Reader.

(PDF)

S. pombe

global mRNA expression. A tab-delimited text format file, readable by both Mathematica and Microsoft Excel, reproducing the relative mRNA expression levels of  = 3167 S. pombe gene clones at

= 3167 S. pombe gene clones at  = 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods from Rustici et al.

[15] with the cell-cycle classifications of Rustici et al. or Oliva et al.

[16].

= 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods from Rustici et al.

[15] with the cell-cycle classifications of Rustici et al. or Oliva et al.

[16].

(TXT)

S. cerevisiae

global mRNA expression. A tab-delimited text format file, readable by both Mathematica and Microsoft Excel, reproducing the relative mRNA expression levels of  = 4772 S. cerevisiae open reading frames (ORFs), or genes, at

= 4772 S. cerevisiae open reading frames (ORFs), or genes, at  = 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods, including cell-cycle classifications, from Spellman et al.

[17].

= 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods, including cell-cycle classifications, from Spellman et al.

[17].

(TXT)

Human global mRNA expression. A tab-delimited text format file, readable by both Mathematica and Microsoft Excel, reproducing the relative mRNA expression levels of  = 13,068 human genes at

= 13,068 human genes at  = 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods, including cell-cycle classifications, from Whitfield et al.

[18].

= 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods, including cell-cycle classifications, from Whitfield et al.

[18].

(TXT)

Acknowledgments

We thank G. H. Golub for introducing us to matrix and tensor computations, and the American Institute of Mathematics in Palo Alto and Stanford University for hosting the 2004 Workshop on Tensor Decompositions and the 2006 Workshop on Algorithms for Modern Massive Data Sets, respectively, where some of this work was done. We also thank C. H. Lee for technical assistance, R. A. Horn for helpful discussions of matrix analysis and careful reading of the manuscript, and L. De Lathauwer and A. Goffeau for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This research was supported by Office of Naval Research Grant N00014-02-1-0076 (to MAS), National Science Foundation Grant DMS-1016284 (to CFVL), as well as the Utah Science Technology and Research (USTAR) Initiative, National Human Genome Research Institute R01 Grant HG-004302 and National Science Foundation CAREER Award DMS-0847173 (to OA). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jensen LJ, Jensen TS, de Lichtenberg U, Brunak S, Bork P. Co-evolution of transcriptional and post-translational cell-cycle regulation. Nature. 2006;443:594–597. doi: 10.1038/nature05186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu Y, Huggins P, Bar-Joseph Z. Cross species analysis of microarray expression data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1476–1483. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mushegian AR, Koonin EV. A minimal gene set for cellular life derived by comparison of complete bacterial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10268–10273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golub GH, Van Loan CF. Matrix Computations. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, third edition; 1996. 694 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Loan CF. Generalizing the singular value decomposition. SIAM J Numer Anal. 1976;13:76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paige CC, Saunders MA. Towards a generalized singular value decomposition. SIAM J Numer Anal. 1981;18:398–405. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alter O, Brown PO, Botstein D. Generalized singular value decomposition for comparative analysis of genome-scale expression data sets of two different organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3351–3356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530258100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alter O. Discovery of principles of nature from mathematical modeling of DNA microarray data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16063–16064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607650103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omberg L, Meyerson JR, Kobayashi K, Drury LS, Diffley JF, et al. Global effects of DNA replication and DNA replication origin activity on eukaryotic gene expression. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:312. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alter O, Golub GH. Integrative analysis of genome-scale data by using pseudoinverse projection predicts novel correlation between DNA replication and RNA transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16577–16582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406767101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omberg L, Golub GH, Alter O. A tensor higher-order singular value decomposition for integrative analysis of DNA microarray data from different studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18371–18376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709146104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Lathauwer L, De Moor B, Vandewalle J. A multilinear singular value decomposition. SIAM J Matrix Anal Appl. 2000;21:1253–1278. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandewalle J, De Lathauwer L, Comon P. The generalized higher order singular value decomposition and the oriented signal-to-signal ratios of pairs of signal tensors and their use in signal processing. Proc ECCTD'03 - European Conf on Circuit Theory and Design. 2003. pp. I-389–I-392.

- 14.Alter O, Golub GH. Reconstructing the pathways of a cellular system from genome-scale signals using matrix and tensor computations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17559–17564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509033102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rustici G, Mata J, Kivinen K, Lió P, Penkett CJ, et al. Periodic gene expression program of the fission yeast cell cycle. Nat Genet. 2004;36:809–817. doi: 10.1038/ng1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliva A, Rosebrock A, Ferrezuelo F, Pyne S, Chen H, et al. The cell cycle-regulated genes of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spellman PT, Sherlock G, Zhang MQ, Iyer VR, Anders K, et al. Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3273–3297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitfield ML, Sherlock G, Saldanha A, Murray JI, Ball CA, et al. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1977–2000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0030.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauthier NP, Larsen ME, Wernersson R, Brunak S, Jensen TS. Cyclebase.org: version 2.0, an updated comprehensive, multi-species repository of cell cycle experiments and derived analysis results. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D699–D702. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated nonredundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D61–D65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Decottignies A, Goffeau A. Complete inventory of the yeast ABC proteins. Nat Genet. 1997;15:137–145. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mamnun YM, Schüller C, Kuchler K. Expression regulation of the yeast PDR5 ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter suggests a role in cellular detoxification during the exponential growth phase. FEBS Lett. 2004;559:111–117. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werner-Washburne M, Braun E, Johnston GC, Singer RA. Stationary phase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:383–401. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.383-401.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers S, Schauer W, Balzi E, Wagner M, Goffeau A, et al. Interaction of the yeast pleiotropic drug resistance genes PDR1 and PDR5. Curr Genet. 1992;21:431–436. doi: 10.1007/BF00351651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahé Y, Parle-McDermott A, Nourani A, Delahodde A, Lamprecht A, et al. The ATP-binding cassette multidrug transporter Snq2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a novel target for the transcription factors Pdr1 and Pdr3. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:109–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfger H, Mahé Y, Parle-McDermott A, Delahodde A, Kuchler K. The yeast ATP binding cassette (ABC) protein genes PDR10 and PDR15 are novel targets for the Pdr1 and Pdr3 transcriptional regulators. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hlaváček O, Kučerová H, Harant K, Palková Z, Váchová L. Putative role for ABC multidrug exporters in yeast quorum sensing. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1107–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KS, Patton JL, Fido M, Hines LK, Kohlwein SD, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae PLB1 gene encodes a protein required for lysophospholipase and phospholipase B activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19725–19730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho RJ, Campbell MJ, Winzeler EA, Steinmetz L, Conway A, et al. A genome-wide transcriptional analysis of the mitotic cell cycle. Mol Cell. 1998;2:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin-Castellanos C, Labib K, Moreno S. B-type cyclins regulate G1 progression in fission yeast in opposition to the p25rum1 cdk inhibitor. EMBO J. 1996;15:839–849. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher DL, Nurse P. A single fission yeast mitotic cyclin B p34cdc2 kinase promotes both S-phase and mitosis in the absence of G1 cyclins. EMBO J. 1996;15:850–860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chu MT, Funderlic RE, Golub GH. On a variational formulation of the generalized singular value decomposition. SIAM J Matrix Anal Appl. 1997;18:1082–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao CR. Linear Statistical Inference and Its Applications. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, second edition; 1973. 656 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rao CR. Optimization of functions of matrices with applications to statistical problems. In: Rao PSRS, Sedransk J, editors. W.G. Cochran's Impact on Statistics. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1984. pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paige CC. The general linear model and the generalized singular value decomposition. Linear Algebra Appl. 1985;70:269–284. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall AW, Olkin L. Matrix versions of the Cauchy and Kantorovich inequalities. Aequationes Mathematicae. 1990;40:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horn RA, Johnson CR. Matrix Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1985. 575 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tavazoie S, Hughes JD, Campbell MJ, Cho RJ, Church GM. Systematic determination of genetic network architecture. Nat Genet. 1999;22:281–285. doi: 10.1038/10343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A PDF format file, readable by Adobe Acrobat Reader.

(PDF)

Higher-order generalized singular value decomposition (HO GSVD) of global mRNA expression datasets from three different organisms. A Mathematica 5.2 code file, executable by Mathematica 5.2 and readable by Mathematica Player, freely available at http://www.wolfram.com/products/player/.

(NB)

HO GSVD of global mRNA expression datasets from three different organisms. A PDF format file, readable by Adobe Acrobat Reader.

(PDF)

S. pombe

global mRNA expression. A tab-delimited text format file, readable by both Mathematica and Microsoft Excel, reproducing the relative mRNA expression levels of  = 3167 S. pombe gene clones at

= 3167 S. pombe gene clones at  = 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods from Rustici et al.

[15] with the cell-cycle classifications of Rustici et al. or Oliva et al.

[16].

= 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods from Rustici et al.

[15] with the cell-cycle classifications of Rustici et al. or Oliva et al.

[16].

(TXT)

S. cerevisiae

global mRNA expression. A tab-delimited text format file, readable by both Mathematica and Microsoft Excel, reproducing the relative mRNA expression levels of  = 4772 S. cerevisiae open reading frames (ORFs), or genes, at

= 4772 S. cerevisiae open reading frames (ORFs), or genes, at  = 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods, including cell-cycle classifications, from Spellman et al.

[17].

= 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods, including cell-cycle classifications, from Spellman et al.

[17].

(TXT)

Human global mRNA expression. A tab-delimited text format file, readable by both Mathematica and Microsoft Excel, reproducing the relative mRNA expression levels of  = 13,068 human genes at

= 13,068 human genes at  = 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods, including cell-cycle classifications, from Whitfield et al.

[18].

= 17 time points during about two cell-cycle periods, including cell-cycle classifications, from Whitfield et al.

[18].

(TXT)