Abstract

Although hepatic fibrosis typically follows chronic inflammation, fibrosis will often regress after cessation of liver injury. Here we examined whether liver dendritic cells (DC) play a role in liver fibrosis regression using carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) to induce liver injury. We examined DC dynamics during fibrosis regression and their capacity to modulate liver fibrosis regression upon cessation of injury. We show that conditional DC depletion soon after discontinuation of the liver insult leads to delayed fibrosis regression and reduced clearance of activated hepatic stellate cells, the key fibrogenic cell in liver. Conversely, DC expansion induced either by Flt3L (Fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand) or adoptive transfer of purified DC accelerates liver fibrosis regression. DC modulation of fibrosis was partially dependent on MMP-9, as MMP-9 inhibition abolished Flt3L-mediated effect and the ability of transferred DC to accelerate fibrosis regression. In contrast, transfer of DC from MMP-9 deficient mice failed to improve fibrosis regression.

Conclusion

Altogether, these results suggest that DC increase fibrosis regression, and that the effect is correlated with their production of MMP-9. These results also suggest that Flt3L treatment during fibrosis resolution merits evaluation to accelerate regression of advanced liver fibrosis.

Keywords: Flt3L, NK cells, MMP-9, collagen, hepatic stellate cells

Introduction

Hepatic fibrosis represents a wound healing response to liver injury from a range of chronic insults, including viruses, drugs, and metabolic diseases. Fibrosis reflects an imbalance between the production of collagen by matrix producing cells, primarily activated hepatic stellate cells (HSC), and matrix degradation by matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) (for reviews see (1,2). Whereas the signals driving activation of HSC during fibrogenesis are increasingly clarified (1), far less is known about the mechanisms that control the regression of fibrosis. Nonetheless, improved disease-specific therapies, for example, clearance of hepatitis C virus or suppression of hepatitis B through antiviral treatments, can bring about remarkable regression of hepatic fibrosis, restoration of normal liver architecture and improvement in clinical features (3,4). Despite attenuated hepatocyte injury in these settings, many patients still harbor significant risk from persistent fibrosis, especially of hepatocellular carcinoma (5–7). Moreover, the presence of advanced liver fibrosis increases the mortality (8) and morbidity (9) of surgical interventions, making reversal toward normal histology an ongoing goal for these patients.

In humans, however, fibrosis regression is a slow process, and thus a better understanding of the mechanisms governing matrix remodeling after the etiologic agent has been stopped is vital in order to reduce complications resulting from advanced fibrosis. In mice, regression of liver fibrosis is more rapid, and begins immediately after the etiologic agent is removed (10). The release of MMPs by macrophages (11,12) and neutrophils (13) is thought to control matrix degradation, and the absence of ongoing hepatocyte damage in this setting is followed by the clearance of the fibrogenic cells through either apoptosis (14,15) or cellular senescence (16).

The past two decades have witnessed remarkable progress in uncovering the cellular sources of matrix and the identification of major fibrogenic, contractile and proliferative cytokines (1,17). Only recently, however, has the contribution of different immune subsets generated interest, including macrophages (11,12), NK cells (18), T cells (19), B cells (20) and NKT (21) cells. Most recently, DC have also been implicated in regulating the hepatic inflammatory milieu in a mouse model of liver fibrosis (22). However, it is unknown whether DC modulate liver fibrosis, extracellular matrix production and degradation, MMP kinetics and/or turnover of fibrogenic cells. In addition, studies have focused exclusively on inflammation associated with fibrosis progression, yet very little is known about their role in fibrosis regression.

Among immune cells, DC play a unique role in tissue immunity through their ability to modulate both innate (23–25) and adaptive immune responses (26). Two main DC subsets have been identified in mice and humans, classical DC (cDC) and plasmacytoid DC (pDC) (27). pDC secrete interferon alpha in response to viral stimuli (28). cDC capture, process, and present tissue antigens to T lymphocytes in draining lymph nodes (29). DC secrete numerous cytokines that contribute to the recruitment and activation of various immune effector cells including NK cells (23), NKT cells (24), and neutrophils (25). Murine and human DC also secrete several MMPs that could participate in the modulation of liver fibrosis (30,31).

Results from a recent study suggest that liver DC promote fibrosis through the secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) (22). However the phenotypic markers used to define DC in this study strongly implicate the participation of other myeloid cells (e.g, macrophages) in the inflammatory response. Consistent with this possibility, macrophages are known to play a dual role in liver fibrosis wherein they amplify liver fibrosis progression, whereas they accelerate fibrosis regression once the liver insult is removed (11).

In order to address the specific impact of DC on extracellular matrix homeostasis rather than inflammation, we have examined whether DC play a role in the modulation of liver fibrosis once the causative agent of liver injury has been removed and inflammation is attenuating. To do so, we have used an experimental model in which mice develop severe but reversible liver fibrosis upon repetitive intra-peritoneal injections of CCl4. This approach provides a clinically relevant model to uncover mechanisms that could lead to therapeutic fibrosis regression in humans. We demonstrate here that DC expansion regulate the regression of liver fibrosis in an MMP-9 dependent manner in CCl4-treated mice.

Methods

Animals

Six week-old female C57BL/6 were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD) and CD11c-DTR-Gfp transgenic mice from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor). NKp46-DTR-eGfp transgenic mice were generated as described (32). All procedures were in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Protocols.

Materials

All reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich unless stated otherwise. MMP-9 inhibitor I was purchased from Calbiochem (Categ.444278); the dose of 0.3 µg/g weight was calculated in order to provide a circulating concentration four times greater than the IC50 in the extracellular water; the dose was repeated every 48 hours since the first day of fibrosis resolution.

Flow cytometry and DC gating strategy

The entire intrahepatic leukocyte population was isolated using the protocol published by Wintermeyer et al (33). Multi-parameter analyses of stained cell suspensions were performed on an LSR II (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar). Detailed information regarding the staining antibodies and gating strategy was provided in supplementary material and Supporting Fig.1A.

Hepatic fibrosis model

CCl4-induced fibrosis was generated by intraperitoneal injections of 0.5 µl CCl4/g body weight in corn oil (10%), three times per week for 8–12 weeks. For evaluation of intrahepatic cells populations dynamic, mice were sacrificed at 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 15, 21 days after last dose of CCl4(Supporting Fig.2A).

DC expansion using Flt3L

Flt3-secreting B16 melanoma cells (B16-Flt3L) (34) were kindly provided by Dr. Gregory Stephen (Brown University). For short-term expansion of DC, mice were injected with 5×105 B16-Flt3L cells subcutaneously in the flank two days before the final CCl4 dose (Supporting Fig.2C). In order to achieved long-term Flt3L-induced DC expansion without the risk of metastasis of melanoma cells, B16 wild type and B16-Flt3L mice were irradiated with 1500 rads and injected every 4 days in a dose of 5×106 cells in the flank, starting two days before the last dose of CCl4 (Supporting Fig.2D).

Adoptive DC transfer

Mice were injected with B16-Flt3L and the spleens were harvested ten days later. Total splenocytes were incubated with anti-NK1.1, anti-CD19 and anti-CD3 biotinylated antibodies, followed by streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech) to negatively deplete lymphocytes. The lineage cell negative fraction was subsequently incubated with CD11c-conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech), and DCs were positively selected. The purity of the DC preparation was confirmed by flow cytometry, cells were then resuspended in PBS and injected systemically through the retro-orbital vein (Supporting Fig.2E).

DC and NK cell depletion

Depletion of cDC was induced in CD11c-DTR-Gfp mice mice as previously reported (35). Briefly, 100 ng (4 ng/g) of DT (List Biological Laboratories Inc.) was administered intraperitoneally one day after the last dose of CCl4. Three days later, the mice were sacrificed and livers were harvested (Supporting Fig.2B).

NK cells depletion using anti-asialo-GM1 antibody (Wako Chemicals) and NKp46-DTR-eGFP mice were performed as published (32,36)(Supporting Fig.2F-G).

Quantitative assessment of fibrosis

Paraffin-embedded liver sections were stained with picrosirius red to measure collagen content as described previously (19), using the Bioquant computerized morphometry program (Supplementary Materials). To stain for α-SMA, paraffin-embedded liver sections were stained with rabbit anti- α-SMA primary antibody (Abcam, dilution 1/50) and visualized with anti-rabbit Envision Plus System HRP (DAKO). Confirmation of collagen staining was obtained by birefringence microscopy using an Axioplan2 microscope (Mount Sinai Imaging Core Facility) and also by immunohistochemistry for collagen using anti-mouse collagen I (Rockland, Dilution 1/50), anti-mouse collagen III (Abcam. Dilution 1/100) and visualization with Histostain Plus kit (Invitrogen).

Quantification of liver fibrosis by an expert liver pathologist (I.F.) was performed using a fibrosis scale from 0–4 as follow: 0-no fibrosis; 1-minimal portal fibrosis; 2-portal fibrosis with septa formation; 3-localized bridging fibrosis; 4-extensive bridging fibrosis. Each staging of fibrosis was assessed in 10 fields at 100× magnification and the average was calculated for each mouse.

Immunofluorescence studies

Six µm frozen liver sections were fixed in cold acetone and stained with rat anti-mouse DEC-205 1/10 (Serotec), CD11c 1/25 (eBioscience) or MHCII 1/25 (eBioscience) and followed by Cy3 conjugated donkey anti-rat antibody 1/500 (Immunoresearch). Images were obtained using an Axioplan2 microscope (Mount Sinai Imaging Core Facility).

For MMP-9/CD11c double staining frozen sections were fixed in acetone, stained with rat anti-mouse CD11c 1/20 (eBioscience) and goat anti-mouse MMP-9 1/25 (Santa Cruz) antibodies, followed by PE conjugated donkey anti-goat 1/400 (Santa Cruz) and AF488 conjugated chicken anti-rat 1/400 (Invitrogen).

MMP-9 Immunofluorescence, Western blot and zymography

For immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of MMP-9 protein levels, frozen sections were fixed in cold acetone, and stained with goat anti-mouse MMP-9 primary antibody (Santa Cruz, dilution1/25) and followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (Santa Cruz, 1/400). Images were obtained using a Leica DM 6000 microscope from Mount Sinai Imaging Core Facility. Western blot for MMPs and zymography were performed as a standard protocol and detailed as supporting information.

In vivo MMP-9 inhibition

In order to inhibit the MMP-9 activity during fibrosis regression, 0.3 µg/g MMP-9 inhibitor I (Calbiochem, Categ.444278) was administered intravenous during fibrosis regression every other day starting at the time of DC expansion by Flt3L-B16 cell placement or DC transfer until the time of sacrifice (total of 3 doses) (Supporting Fig.2H-2I).

Toll Like Receptor (TLR) stimulation

In order to evaluate the up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules and CCR7 after TLR stimulation, whole liver leukocytes were cultured for 8 hours with 20 µg/ml poly IC (Sigma) followed by staining and polychromatic flow cytometry for CD40, CD80, CD86 and CCR7 on DC and macrophages populations.

Stimulation of MMP-9 production from purified DC was performed as reported (30). Briefly, purified DC were cultured with or without LPS (1 µg/ml), and MMP9 levels were quantified in the cell pellets and supernatants 12, 24 and 36 h later.

Statistical analysis

Error bars represent mean+/−SD and were analyzed by Student’s t test, Mann-Whiney U test or ANOVA analysis, as appropriate, with Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Values of P <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Phenotypic identification of liver myeloid cells populations

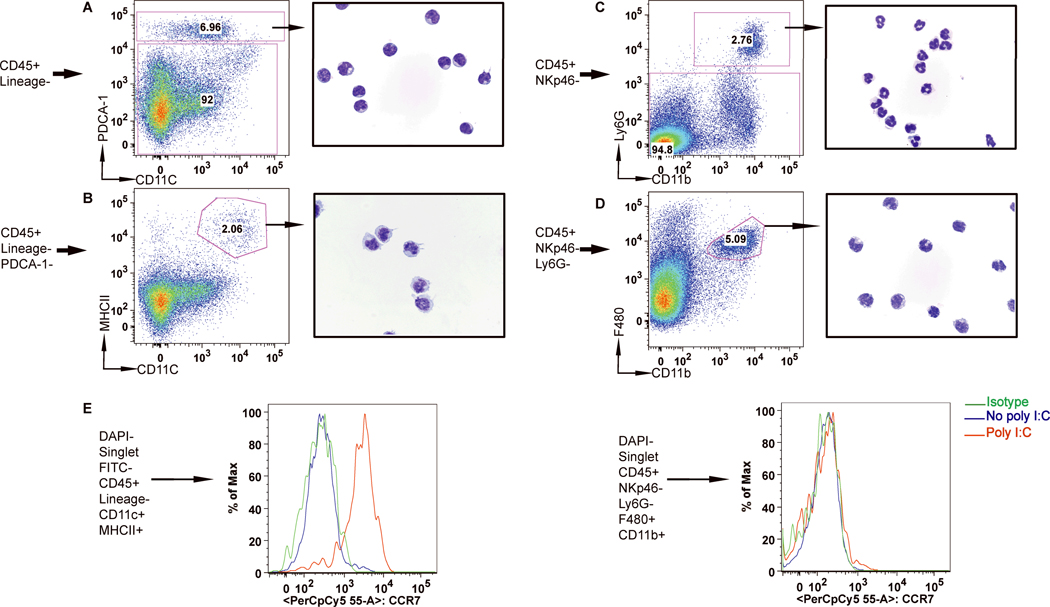

To characterize the resident DC subsets that populate the normal liver, we performed polychromatic flow cytometry sorting and Giemsa stains of purified populations.

Liver pDC (Fig.1A) were identified based on the expression of the pan-hematopoietic cells marker (CD45), absence of lineage markers for T, B, NK, and NKT cells, presence of PDCA-1 and intermediate CD11c levels (Fig 1A and Supporting Fig.1A). Giemsa stain of this purified population identified typical pDC morphology (Fig.1A). Liver cDC were identified as CD45+ Lineage negative PDCA-1– MHCIIhigh CD11chigh cells (Fig.1B and Supporting Fig.1A) and had typical DC morphology on Giemsa stain (Fig.1B).

Figure 1. Identification of liver DC using multicolor FACS and validation of DC morphology.

Fresh intrahepatic leukocytes were analyzed by multicolor flow cytometry and two major populations of cells were identified in the Lineage negative cells: 1. one express high levels of PDCA-1 and CD11cint (A) that corresponds morphologically to pDC after cytospin of the purified sorted cells; 2. Second population is PDCA-1 negative, and expressed high levels of CD11c and MHCII and has characteristic DC appearance (B). Neutrophils are identified as CD11b+Ly6G+ cells (C) while macrophages as Ly6G-CD11b+F480+ cells (D). All cytospin images are obtained at ×1000 magnification. (E). The CD11chighMHCIIhigh population significantly up-regulates CCR7 after poly I:C stimulation. After poly I:C stimulation only Lin negative CD11chighMHCIIhigh cells are able to up-regulate expression of lymph node homing receptor CCR7.

Liver neutrophils were identified as CD45+Ly6G+CD11b+ cells (Fig. 1C and Supporting Fig.1B). Liver macrophages were identified as a CD45+NK1.1-Ly6G-CD11+F480+ population (Supporting Fig.1B). Giemsa stain of this purified population reveal a monocytoid morphology with a vacuolar cytoplasm that is typical of macrophages (Fig.1D).

DC consistently upregulated the lymph node homing chemokine receptor CCR7 and the co-stimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, CD86) after poly I:C stimulation, whereas F480+CD11b+ cells did not (Fig.1E and Supporting Fig.3B).

Hepatic fibrosis regression is associated with increased infiltrating DC following the cessation of the liver insult

We have focused on the mechanisms that control hepatic fibrosis regression as a means to developing new therapeutic approaches relevant to human disease. In order to induce liver fibrosis we used a reproducible and well-validated model of CCl4-induced injury. Administration of CCl4 leads to inflammation and bridging fibrosis, which improves rapidly during the first week after discontinuation (10–11,37), with 50% of liver collagen disappearing during this interval (Fig.2A-B). To assess the factors regulating fibrosis resolution, we first examined immune cell dynamics in the liver in the first three weeks following CCl4 discontinuation (Supporting Fig.2A). The number of CD45+ cells and macrophages have a similar dynamic with a rapid decline during the first week (Fig.2C and Supporting Fig.4A). In contrast, immunoflorescence staining of hepatic CD11c+ cells in the first week of regression identified persistence of this population during initial 5 days and lower numbers of CD11c+ cells by day 7 (Fig.2D). To assess CD11c+ cell subsets more quantitatively, flow cytometry was used, which indicated that the total number of cDC, pDC (as defined in Supporting Fig.1) and NK cells peaked between days 2 and 4 after CCl4 cessation (Fig. 2C and Supporting Fig.4B). Infiltrating neutrophils accumulated later, during days 7–8 after the last dose of CCl4 consistent with previous report in a rat bile duct ligation liver fibrosis model (13)(Supporting Fig.4C-D).

Figure 2. Liver fibrosis regression is associated with increased number of hepatic cDC, pDC and NK cells.

Mice were treated with CCl4 as described in the Materials and Methods. (A-B) Accelerated fibrosis regression occurs during the first week following discontinuation of the liver injury. Fibrosis regression was assessed by Sirius Red morphometry (A) and histological staging (B). (C) Early fibrosis regression is associated with increased number of cDC and pDC in the liver while the overall inflammatory infiltrate (CD45+ cells) decreases. Graphs show the absolute number of CD45+ cells, cDC (Lineage negative, MHCIIhighCD11chigh) and pDC (Lineage negative, PDCA-1+) in the liver during fibrosis regression (in black). The number of steady state liver CD45, cDC, pDC were presented in red triangles (C). Increased in the number of CD11c+ cells by immunofluorescence (white arrows) was confirmed during days 1 and 5 of fibrosis regression (D). The flow cytometry density plots display the relative number of cDC during fibrosis regression (E).

DC depletion delays regression and clearance of activated HSC during the early stage of fibrosis resolution

To examine the contribution of liver DC to the outcome of hepatic fibrosis, we used a conditional DC depletion mouse model in which transgenic mice expressing the diphtheria toxin receptor under the control of the CD11c promoter (CD11c-DTR) CD11c-DTR mice were treated with CCl4, as described (35). Administration of 100 ng of DT in steady state or within one day after the last CCl4 dose led to transient depletion of cDC (Fig.3A and Supporting Fig.5A), without affecting plasmacytoid DC, NK cells or F480+CD11b+ populations (Supporting Fig.5B-D). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that DT administration led to the specific depletion of CD11chighMHCIIhigh cells, and failed to affect CD11cint/low cells (Supporting Fig. 6E-6F). Strikingly, cDC depletion was associated with delayed fibrosis regression as measured by histological scoring and collagen morphometry (Fig.3B-D). Increased collagen was also seen in DC-depleted mice by assessing birefringence properties of collagen (Fig.3E). DC depletion was associated with more collagens I and III by immunohistochemistry (Fig.3F-G), and reduced clearance of HSC (Fig.3H-I). These data suggest that DC accumulation in the fibrotic liver shortly after the cessation of liver injury may direct the outcome of fibrosis.

Figure 3. DC depletion early after CCl4 discontinuation delays fibrosis regression.

CD11c-DTR transgenic mice treated with CCl4 were injected one day after the last CCl4 dose with DT (4 ng/g). (A-G) DT administration to CCl4-treated mice strongly reduces the liver DC pool. (A) Bar graph demonstrates the absolute number of DAPI-CD45+autofluorescence-Lineage negative MHCIIhighCD11chigh DC at different intervals with or without DT administration (* p<0.05) during fibrosis regression. (B) Graphs show the percentage of liver area positive for Sirius red. (C) Histological staging of liver fibrosis. Data are presented as mean +/− SD; each group included four mice and each was replicated three times. (D) Sirius Red staining of paraffin-embedded liver sections reveals thicker bands of collagen upon DC depletion in comparison with untreated mice. (E) Similar data were obtained by birefringence microscopic evaluation, and (F-G) immunohistochemistry for collagens I and III (magnification, ×100). (H-I) DC depletion delays clearance of activated HSC. Graph shows the percentage of liver area positive for α-smooth muscle actin HSC cells (H) in mice that received DT compared to mice that did not receive DT (I) (magnification, ×200).

Flt3L accelerates fibrosis regression in CCl4-induced hepatic fibrosis

Administration of the growth factor fms like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) leads to dramatic expansion of classical and plasmacytoid DC in mice and humans (38,39), and injection of cell lines transduced with Flt3L gene are commonly used in mice to deliver the Flt3L protein in vivo (34). Consistent with previous studies, injection genetically modified B16-Flt3L cells induced significant expansion of liver DC within four days after cell implantation (Supporting Fig.6).

Flt3L treatment led to significant DC expansion during fibrosis regression (Supporting Fig.2C), as measured by flow cytometry (Fig.4A-B). Accumulation of DC along the fibrotic portal tracts was confirmed by immunofluorescence (Fig.4C).

Figure 4. Flt3L expands classical and plasmacytoid DC in murine liver during fibrosis regression.

Groups of mice were treated with as described in material and methods. Two days before the last CCl4 injection, mice were injected with 5×105 B16 melanoma cells or with 5×105 B16-Flt3L cells, or left untreated. Mice were sacrificed seven days after the last CCl4 injection and analyzed for extent of fibrosis regression. Dot plots show the relative number (A), while bar graphs the absolute number (B) of liver MHCIIhighCD11chigh classical DC (cDC) and PDCA-1+plasmacytoid DC (pDC) seven days after last CCl4 injection. Data are presented as mean +/− SD; each group included five mice and each was replicated three times (* p<0.05) (C) staining of frozen liver sections with anti-DEC205 antibody in CCl4-treated mice, either with or without B16-Flt3L injection, or in control mice treated with B16-Flt3L that did not receive CCl4.

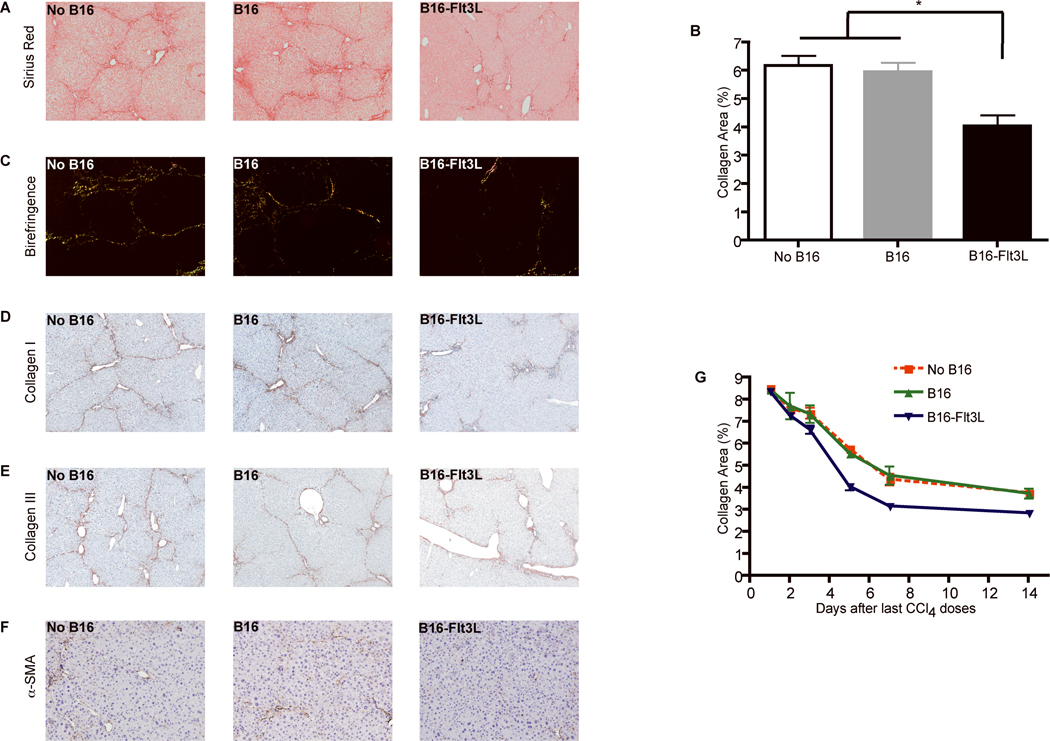

Flt3L treatment improved fibrosis outcome as measured by (i) reduced collagen content as assesses by morphometry and birefringence (Fig.5A-C); (ii) immunohistochemistry of collagens I & III (Fig.5D-E); and (iii) increased clearance of activated HSC (Fig.5F). Following long-term Flt3L DC expansion protocol (Supporting Fig.2D), we detected improved fibrosis regression as early as four days after the last CCl4 dose, which persisted for more than 14 days post treatment (Fig.5G).

Figure 5. Flt3L treatment improves fibrosis resolution after CCl4 discontinuation.

Mice were treated as in Figure 4 and fibrosis regression was assessed one week after cessation of CCl4. Paraffin embedded liver sections stained with Sirius red (A) reveal reduced fibrosis in mice injected with B16-Flt3L compared to control mice (magnification, ×100). (B) Bar graph shows the percentage of liver area positive for Sirius red staining measured by computerized morphometry in mice injected with either B16-Flt3L or B16 wild type cells. Data are presented as mean +/− SD; each group included five mice and each was replicated three times (* p<0.05). Less fibrosis in the group of Flt3L-treated mice was confirmed by birefringence microscopy (C) and immunohistochemistry for collagen I, III and α-smooth muscle actin (D-F). (G) Graph shows the accelerated fibrosis regression measured by Sirius red morphometry after repeated irradiated B16-Flt3L administration during first two weeks following CCl4 discontinuation.

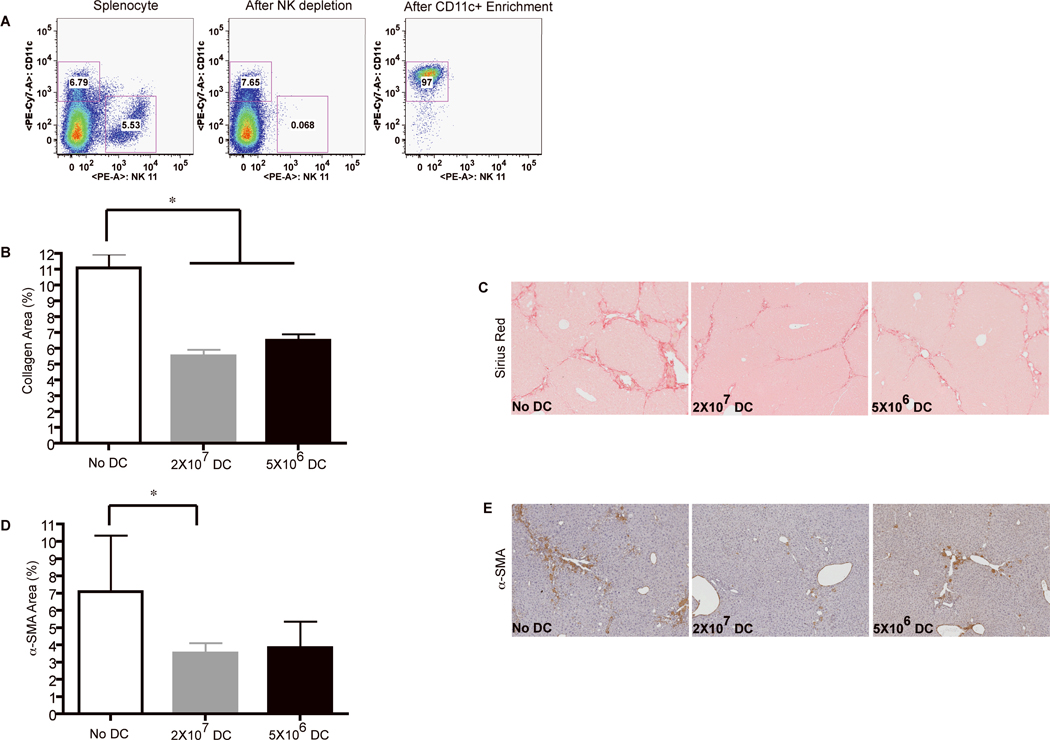

Adoptive transfer of purified DC improves fibrosis resolution and increases the clearance of activated HSC

Flt3L not only expands DC, but also expands monocytes, granulocytes and NK cells (40). Because each of these cell types can potentially modulate liver fibrosis regression, we sought to examine whether adoptive transfer of purified DC accelerates regression of liver fibrosis in CCl4-treated mice. To this end, splenic DC were enriched to 97% purity of cells expressing high levels of CD11c and MHCII (Fig.6A). Upon adoptive transfer, CFSE labeled cDC and pDC populations were able to home to the liver (Supporting Fig.7A-B). Similar to Flt3L-treated mice, injection of purified DC reduced liver collagen content (Fig.6B-C) and increased HSC clearance (Fig.6D-E). Altogether, these data suggest that accumulation of DC at the liver site accelerates fibrosis regression upon cessation of CCl4 treatment, and increases the clearance of activated HSC.

Figure 6. Adoptive transfer of purified DC accelerates fibrosis resolution.

Groups of mice were injected two days after the last CCl4 dose with 2×107 DC or 5×106 purified DC, or left untreated. Five days after the last CCl4 injection the mice were sacrificed. (A) Purity of DC preparation. Dot plots show the percentage of DC and NK cells after DC purification. (B-E) Adoptive transfer of DC accelerates liver fibrosis regression. Graphs show the percentage of liver area positive for Sirius red (B) and α-smooth muscle actin (D) staining measured by morphometry analysis five days after DC injection, compared to untreated mice (* P<0.05). Data are presented as mean with SD of three separate experiments (n=4) (* P<0.05). (C) Paraffin embedded liver sections stained with Sirius red reveal reduced collagen deposition in mice that received DC. (E) Paraffin embedded liver sections stained with anti-α-smooth muscle actin antibody reveal reduced numbers of activated hepatic stellate cells in mice that received high dose DC.

Depletion of NK cells during Flt3L DC expansion has no impact on fibrosis resolution

NK cells are critical to enhance the clearance of activated HSC during fibrosis progression (18). Since DC can activate NK cells, it is possible that acceleration of hepatic fibrosis regression observed both in Flt3L-treated mice and following DC adoptive transfer is mediated by activated NK cells. Thus, we examined whether NK depletion affected DC-induced fibrosis resolution. To do so, we used two separate models to deplete NK cells during DC expansion (Supporting Fig.2F-G). NK depletion using asialo-GM-1 antibody or chimeric NKp46-DTR mice (Supporting Fig. 8A-B) does not impact DC effect on fibrosis resolution (Supporting Fig.8C-D).

Up-regulation of MMP-9 is critical for fibrosis resolution upon DC expansion

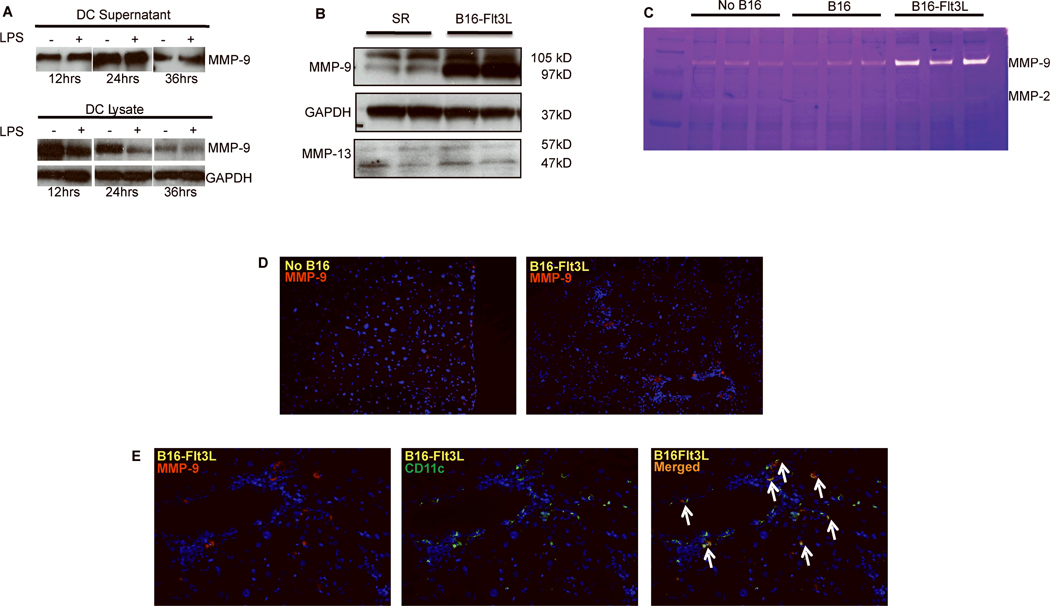

The finding that DC expansion accelerates fibrosis regression independent of NK cells prompted us to investigate other mechanisms by which DC modulates extracellular matrix homeostasis. Among these, regulation of MMP secretion was most likely, given the ability of several inflammatory cells to produce these molecules.

First, we examined whether liver DC secrete MMP-9. Purified DC cultured in medium with or without LPS secrete MMP-9 into the cell supernatant, as assessed by Western blot analysis, whereas the intracellular content of MMP-9 decreased (Fig.7A). Among the MMPs, production and activity of MMP-9 was the most strongly induced in the liver of Flt3L-treated animals (Fig.7B). In contrast, expression of MMP-13, the main collagenolytic murine MMP, was not up-regulated by Flt3L treatment (Fig.7B). MMP-9 was significantly increased by immunofluorescence in Flt3L treated mice (Fig.7D), which was reflected in the increased MMP-9 activity based on zymography (Fig.7C). Moreover, by immunofluorescence, MMP-9 co-localized with CD11c in Flt3L treated mice (Fig.7E). Although CD11c do not exclusively represent the DC population, our data support DC as a source of whole liver MMP-9 in Flt3L treated mice, especially when correlated with MMP-9 expression in purified DC, whole liver lysates and MMP-9 activity.

Figure 7. MMP-9 is secreted by liver DC and increased in Flt3L-treated mice.

(A) Liver DC secretes MMP-9 Purified DC obtained as described in Figure 6 were cultured for 36 hours with or without LPS, and DC lysates and supernatants were assessed for MMP-9 by Western blot at 12, 24 and 36 hours. (B-C) Flt3L treatment increases MMP-9 levels and activity during fibrosis regression. Whole liver protein lysates were obtained from the mice with or without Flt3L-B16 treatment after CCl4 was discontinued, and assessed for MMP-9 and MMP-13 protein levels by Western blot and for MMP activity by gelatinase zymography. (D) Increased MMP-9 in liver tissue was confirmed by immunofluorescence (magnification ×200). (E) Co-localization of CD11c and MMP-9 by immunostaining after B16-Flt3L treatment during fibrosis regression (magnification ×200).

We next examined whether the capacity of DC to accelerate fibrosis regression was mediated by their ability to increased MMP-9 locally. For this purpose, mice with CCl4-induced fibrosis were treated either Flt3L alone or with Flt3L in the presence of a specific MMP-9 inhibitor (Supporting Fig.2H). Strikingly, co-administration of an MMP-9 inhibitor abolished Flt3L’s ability to accelerate hepatic fibrosis regression (Fig.8A-B).

Figure 8. DC improve liver fibrosis partly through MMP-9 secretion.

(A-D) MMP-9 inhibition blunts the impact of Flt3L treatment and DC expansion on fibrosis regression. Graphs show the percentage of liver area positive for Sirius red staining measured by morphometry analysis seven days after the last CCl4 injection in mice injected with B16-Flt3L (A) or purified DC (C) alone or in addition to a specific MMP-9 inhibitor. Data are presented as mean with SD (n=4) (* P<0.05). Sirius red staining of paraffin embedded liver sections for mice that received or not MMP-9 inhibitor after B16-Flt3L melanoma cells placement (B) or DC transfer (D). (E-F) Absence of MMP-9 in transferred DC abolishes their beneficial effect on fibrosis regression. CCl4-treated mice were injected with 107 DC isolated from wild type C57BL6 mice or MMP-9 KO mice. (E) Bar graphs show the percentage of liver area positive for Sirius red morphometry analysis seven days after last CCl4 dose. Data are presented as mean with SD (n=4) (* P<0.05) and replicated twice. (F) Images show Sirius red staining of paraffin embedded liver sections in mice that received MMP-9 KO DC, wild type DC, or no DC.

To further confirm that the MMP-9 inhibitor specifically attenuated the ability of DC to accelerate fibrosis resolution, we also administrated the MMP-9 inhibitor to mice that had received purified DC by adoptive transfer (Supporting Fig.2I). Consistent with the results in Flt3L-treated mice, the MMP-9 inhibitor also abolished the ability of adoptively transferred purified DC to accelerate fibrosis resolution in CCl4-treated mice (Fig.8C-D).

DC improve liver fibrosis resolution in part through the secretion of MMP-9

These results established that accumulation of DC in the liver shortly after cessation of liver injury is critical to improving the outcome of hepatic fibrosis, and that depletion of DC leads to persistence of fibrosis. Our results also suggested that up-regulation of MMP-9 during the first days that follows cessation of the liver injury improved liver fibrosis after cessation of CCl4. To examine whether DC-mediated liver fibrosis was dependent on their ability to secrete MMP-9, we adoptively transferred either wild type DC or MMP-9-deficient DC (Supporting Fig.2J). Transfer of DC does not induce an increase inflammation, reflected in the number of the total leukocytes, macrophages and neutrophils (Supporting Fig.9A-C).

Strikingly, transfer of purified DC isolated from MMP-9 deficient animals failed to improve fibrosis, whereas wild type DC improved liver fibrosis (Fig.8E-F). These results suggest that DC accelerated fibrosis resolution at least in part through their ability to secrete MMP-9.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the key role of hepatic DC in the modulation of liver fibrosis using three experimental models. First, conditional DC depletion following CCl4 cessation delayed liver fibrosis regression. Second, increased in vivo availability of DC growth factor, Flt3L, accelerated liver fibrosis regression, and third, adoptive transfer of purified DC also accelerated regression.

The rapidity of liver fibrosis regression upon DC expansion suggests that increased collagen degradation, rather than decreased production, is the main determinant of regression. Consistent with this hypothesis, Flt3L treatment was associated with increased MMP-9 protein levels in whole liver tissue by two different assays, which was associated with increased MMP-9 activity. Moreover, MMP-9 displays significant direct interstitial collagenase activity on native forms of collagen I and III (41), and previous reports have also linked MMP-9 activity to reduced fibrogenesis in models of lung fibrosis (42). These studies identified IGF/IGFBP as the intermediate pathway affected by MMP-9 during fibrogenesis. In addition, MMP-9 activates chemokines known to induce the recruitment of innate immune cells (e.g., macrophages and neutrophils) (43) that secrete other enzymes (MMP-13, MMP-8) capable of degrading interstitial collagens characteristic of hepatic fibrosis.

MMP-13, which is the main murine MMP with collagenase activity, was not affected by Flt3L expansion in spite of the fact MMP13 mRNA is up-regulated during activation of DC (data not shown). Rather, our findings clearly identify that MMP-9 released from DC is critical for the beneficial effect of DC expansion during fibrosis resolution. Our data do not distinguish whether increased MMP-9 activity in the whole liver entirely reflects direct secretion from expanded DC, or also results from the stimulation of MMP-9 secretion by other infiltrating or resident cell types including macrophages, neutrophils or HSC. Nonetheless, direct secretion of MMP-9 by DC is likely to be vital, since adoptive transfer of DC purified from MMP-9 deficient mice does not improve fibrosis resolution. Interestingly, one of the major cytokines involved in neutrophil recruitment, LIX, is activated by MMP-9 (44), and future studies could assess the effect of MMP-9 on LIX activation during fibrosis regression.

DC accelerated fibrosis regression very quickly once the insult was withdrawn. This finding is consistent with previous data indicating that administration of another myeloid growth factor, granulocyte colony stimulation factor (G-CSF), improves fibrosis within five days following the last CCl4 dose (45). G-CSF improvement of liver fibrosis is likely mediated by its ability to increase number of circulating neutrophils, known to represent a major source of MMP-8 in the liver during fibrosis regression (13,46).

Our results are also consistent with previous reports that bone marrow-derived cells control liver fibrosis regression in an MMP-9 dependent manner (45). However, in this earlier study the phenotype of the anti-fibrogenic cell was not characterized. Our results further imply that DC could account for the reported therapeutic benefit of bone marrow infusion (47).

The antifibrogenic role of DC during fibrosis regression in our study contrasts with a recent report suggesting that DC promote liver fibrosis progression in mice (22). One potential explanation for the discrepancy is the rigor of DC characterization. In the prior report, DC were defined and isolated primarily based on their expression of CD11c. However, the sole use of CD11c, especially in an inflamed tissue, would lead to substantial inclusion of monocytes, macrophages (48) and NK cells (49), which likely accounts for the high number of liver DC reported in this study. Indeed, although the relative number of DC among liver leukocytes in a fibrotic liver never exceeded 7% in our study, more than 25% leukocytes were defined as DC in this recent work (22). Moreover, monocytes and macrophages have previously been shown to promote hepatic fibrosis, and the less rigorous definition of DC may reflect the significant contribution of monocytes and macrophages to the reported results. Indeed, there remains considerable debate on the optimal methods to distinguish DC from macrophages in vivo (50,51). In our study, cells were defined as DC based on side-scatter forward-scatter, the expression of the CD45+ hematopoietic cell marker, the absence of B, T, NK markers, and high expression of MHC II and CD11c. This gating strategy identifies a population of cells that up-regulates CCR7 expression, a key molecule that drives DC migration to draining lymph nodes. Expression of CD11c alone is controversial as an exclusive marker of DC, but this feature, in combination with other markers, support the identification of these cells as DC in our experiments.

An additional explanation for our divergent results is that DC may, like macrophages (11), play a dual role in liver fibrosis, exhibiting a profibrogenic activity during progression of liver injury and an anti-fibrotic one after liver injury has been discontinued. Thus, in future studies it will be critical to distinguish between activity of DC and related cells when injury is ongoing, compared to studies where the injury has already ceased.

In this study we did not explore the role of DC on fibrosis progression, since this would require persistent DC expansion during ongoing liver injury for at least one month. However, our preliminary studies demonstrated that short-term expansion of DC affected fibrosis progression in a dose-dependent manner that was dependent on the type of primary injury (hepatocyte versus cholestatic injury).

Our results are particularly relevant to the clinical development of anti-fibrotic therapy for patients with advanced liver disease, especially where the primary disease has been controlled, since Flt3L has been extensively evaluated in clinical trials intended to augment anti-tumor immunity. Similar to mice, administration of Flt3L in humans dramatically expands DC (39,52). Importantly, administration of Flt3L has proven to be safe in normal human volunteers (52) and in cancer patients (53).

In conclusion, our results suggest that DC have the potential to promote the remodeling of hepatic extracellular matrix and hepatic fibrosis regression following cessation of liver injury. These results create an opportunity for novel clinical strategies to reverse liver fibrosis in patients, specifically in those in which the etiologic agent is no longer present yet the fibrosis is persistent, for example following successful clearance of hepatitis C or suppression of hepatitis B infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by funds from the Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the AASLD Liver Scholar Award (to CA), NIH DK56621 and 1K05AA018408-01 (to SLF); CA112100 and HL086899 (to MM).

List of abbreviations

- CCl4

carbon tetrachloride

- DAPI

4',6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole

- DC

dendritic cells

- DTR

diphtheria toxin receptor

- Flt3L

fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand

- G-CSF

granulocyte colony stimulation factor

- HSC

hepatic stellate cells

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- IGF

insulin like-growth factor

- IGFBP

insulin-like growth factor binding protein

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented in abstract form at the 2008 American Assn for the Study of Liver Diseases Annual meeting.

Disclosures: There are no conflicts of interest to disclose for all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramachandran P, Iredale JP. Reversibility of liver fibrosis. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886–893. doi: 10.1002/hep.23785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mallet V, Gilgenkrantz H, Serpaggi J, Verkarre V, Vallet-Pichard A, Fontaine H, Pol S. Brief communication: the relationship of regression of cirrhosis to outcome in chronic hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:399–403. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-6-200809160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan TR, Ghany MG, Kim HY, Snow KK, Shiffman ML, De Santo JL, Lee WM, et al. Outcome of sustained virological responders with histologically advanced chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;52:833–844. doi: 10.1002/hep.23744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirakawa M, Ikeda K, Arase Y, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Hosaka T, Sezaki H, et al. Hepatocarcinogenesis following HCV RNA eradication by interferon in chronic hepatitis patients. Intern Med. 2008;47:1637–1643. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Fong DY, Fung J, Wong DK, Yuen JC, But DY, et al. Independent risk factors and predictive score for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teh SH, Nagorney DM, Stevens SR, Offord KP, Therneau TM, Plevak DJ, Talwalkar JA, et al. Risk factors for mortality after surgery in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1261–1269. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bingener J, Cox D, Michalek J, Mejia A. Can the MELD score predict perioperative morbidity for patients with liver cirrhosis undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Am Surg. 2008;74:156–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HS, Huang GT, Miau LH, Chiou LL, Chen CH, Sheu JC. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases in spontaneous regression of liver fibrosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1114–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, Clay S, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, Wu S, et al. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fallowfield JA, Mizuno M, Kendall TJ, Constandinou CM, Benyon RC, Duffield JS, Iredale JP. Scar-associated macrophages are a major source of hepatic matrix metalloproteinase-13 and facilitate the resolution of murine hepatic fibrosis. J Immunol. 2007;178:5288–5295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harty MW, Huddleston HM, Papa EF, Puthawala T, Tracy AP, Ramm GA, Gehring S, et al. Repair after cholestatic liver injury correlates with neutrophil infiltration and matrix metalloproteinase 8 activity. Surgery. 2005;138:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iredale JP, Benyon RC, Pickering J, McCullen M, Northrop M, Pawley S, Hovell C, et al. Mechanisms of spontaneous resolution of rat liver fibrosis. Hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and reduced hepatic expression of metalloproteinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:538–549. doi: 10.1172/JCI1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Issa R, Williams E, Trim N, Kendall T, Arthur MJ, Reichen J, Benyon RC, et al. Apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells: involvement in resolution of biliary fibrosis and regulation by soluble growth factors. Gut. 2001;48:548–557. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, Hearn S, Simon J, Miething C, Yee H, et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell. 2008;134:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt AP, Salmon M, Buckley CD, Adams DH. Immune interactions in hepatic fibrosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:861–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2008.07.002. x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radaeva S, Sun R, Jaruga B, Nguyen VT, Tian Z, Gao B. Natural killer cells ameliorate liver fibrosis by killing activated stellate cells in NKG2D-dependent and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-dependent manners. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:435–452. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safadi R, Ohta M, Alvarez CE, Fiel MI, Bansal M, Mehal WZ, Friedman SL. Immune stimulation of hepatic fibrogenesis by CD8 cells and attenuation by transgenic interleukin-10 from hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:870–882. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novobrantseva TI, Majeau GR, Amatucci A, Kogan S, Brenner I, Casola S, Shlomchik MJ, et al. Attenuated liver fibrosis in the absence of B cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3072–3082. doi: 10.1172/JCI24798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park O, Jeong WI, Wang L, Wang H, Lian ZX, Gershwin ME, Gao B. Diverse roles of invariant natural killer T cells in liver injury and fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride. Hepatology. 2009;49:1683–1694. doi: 10.1002/hep.22813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connolly MK, Bedrosian AS, Mallen-St Clair J, Mitchell AP, Ibrahim J, Stroud A, Pachter HL, et al. In liver fibrosis, dendritic cells govern hepatic inflammation in mice via TNF-alpha. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3213–3225. doi: 10.1172/JCI37581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucas M, Schachterle W, Oberle K, Aichele P, Diefenbach A. Dendritic cells prime natural killer cells by trans-presenting interleukin 15. Immunity. 2007;26:503–517. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiethe C, Debus A, Mohrs M, Steinkasserer A, Lutz M, Gessner A. Dendritic cell differentiation state and their interaction with NKT cells determine Th1/Th2 differentiation in the murine model of Leishmania major infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:4371–4381. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morel C, Badell E, Abadie V, Robledo M, Setterblad N, Gluckman JC, Gicquel B, et al. Mycobacterium bovis BCG-infected neutrophils and dendritic cells cooperate to induce specific T cell responses in humans and mice. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:437–447. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449:419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shortman K, Liu YJ. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:151–161. doi: 10.1038/nri746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asselin-Paturel C, Boonstra A, Dalod M, Durand I, Yessaad N, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Vicari A, et al. Mouse type I IFN-producing cells are immature APCs with plasmacytoid morphology. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/ni736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helft J, Ginhoux F, Bogunovic M, Merad M. Origin and functional heterogeneity of non-lymphoid tissue dendritic cells in mice. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:55–75. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yen JH, Khayrullina T, Ganea D. PGE2-induced metalloproteinase-9 is essential for dendritic cell migration. Blood. 2008;111:260–270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kouwenhoven M, Ozenci V, Tjernlund A, Pashenkov M, Homman M, Press R, Link H. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells express and secrete matrix-degrading metalloproteinases and their inhibitors and are imbalanced in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;126:161–171. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walzer T, Blery M, Chaix J, Fuseri N, Chasson L, Robbins SH, Jaeger S, et al. Identification, activation, and selective in vivo ablation of mouse NK cells via NKp46. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3384–3389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609692104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wintermeyer P, Cheng CW, Gehring S, Hoffman BL, Holub M, Brossay L, Gregory SH. Invariant natural killer T cells suppress the neutrophil inflammatory response in a mouse model of cholestatic liver damage. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1048–1059. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mach N, Gillessen S, Wilson SB, Sheehan C, Mihm M, Dranoff G. Differences in dendritic cells stimulated in vivo by tumors engineered to secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor or Flt3-ligand. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3239–3246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Probst HC, Tschannen K, Odermatt B, Schwendener R, Zinkernagel RM, Van Den Broek M. Histological analysis of CD11c-DTR/GFP mice after in vivo depletion of dendritic cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141:398–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02868.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okano F, Merad M, Furumoto K, Engleman EG. In vivo manipulation of dendritic cells overcomes tolerance to unmodified tumor-associated self antigens and induces potent antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2005;174:2645–2652. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinn PS, Higginson J. Reversible and Irreversible Changes in Experimental Cirrhosis. Am J Pathol. 1965;47:353–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maraskovsky E, Brasel K, Teepe M, Roux ER, Lyman SD, Shortman K, McKenna HJ. Dramatic increase in the numbers of functionally mature dendritic cells in Flt3 ligand-treated mice: multiple dendritic cell subpopulations identified. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1953–1962. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pulendran B, Banchereau J, Burkeholder S, Kraus E, Guinet E, Chalouni C, Caron D, et al. Flt3-ligand and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilize distinct human dendritic cell subsets in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165:566–572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karsunky H, Merad M, Cozzio A, Weissman IL, Manz MG. Flt3 ligand regulates dendritic cell development from Flt3+ lymphoid and myeloid-committed progenitors to Flt3+ dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003;198:305–313. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bigg HF, Rowan AD, Barker MD, Cawston TE. Activity of matrix metalloproteinase-9 against native collagen types I and III. FEBS J. 2007;274:1246–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cabrera S, Gaxiola M, Arreola JL, Ramirez R, Jara P, D'Armiento J, Richards T, et al. Overexpression of MMP9 in macrophages attenuates pulmonary fibrosis induced by bleomycin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:2324–2338. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D'Haese A, Wuyts A, Dillen C, Dubois B, Billiau A, Heremans H, Van Damme J, et al. In vivo neutrophil recruitment by granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 is assisted by gelatinase B/MMP-9 in the mouse. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:667–674. doi: 10.1089/107999000414853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van den Steen PE, Proost P, Wuyts A, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. Neutrophil gelatinase B potentiates interleukin-8 tenfold by aminoterminal processing, whereas it degrades CTAP-III, PF-4, and GRO-alpha and leaves RANTES and MCP-2 intact. Blood. 2000;96:2673–2681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higashiyama R, Inagaki Y, Hong YY, Kushida M, Nakao S, Niioka M, Watanabe T, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells express matrix metalloproteinases and contribute to regression of liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2007;45:213–222. doi: 10.1002/hep.21477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harty MW, Papa EF, Huddleston HM, Young E, Nazareth S, Riley CA, Ramm GA, et al. Hepatic macrophages promote the neutrophil-dependent resolution of fibrosis in repairing cholestatic rat livers. Surgery. 2008;143:667–678. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakaida I. Autologous bone marrow cell infusion therapy for liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1349–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu H, Gower RM, Wang H, Perrard XY, Ma R, Bullard DC, Burns AR, et al. Functional role of CD11c+ monocytes in atherogenesis associated with hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2009;119:2708–2717. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.823740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burt BM, Plitas G, Stableford JA, Nguyen HM, Bamboat ZM, Pillarisetty VG, DeMatteo RP. CD11c identifies a subset of murine liver natural killer cells that responds to adenoviral hepatitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:1039–1046. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0408256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geissmann F, Gordon S, Hume DA, Mowat AM, Randolph GJ. Unravelling mononuclear phagocyte heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:453–460. doi: 10.1038/nri2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, Dalod M, Grau V, Hart DN, Leenen PJ, et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116:e74–e80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maraskovsky E, Daro E, Roux E, Teepe M, Maliszewski CR, Hoek J, Caron D, et al. In vivo generation of human dendritic cell subsets by Flt3 ligand. Blood. 2000;96:878–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Freedman RS, Vadhan-Raj S, Butts C, Savary C, Melichar B, Verschraegen C, Kavanagh JJ, et al. Pilot study of Flt3 ligand comparing intraperitoneal with subcutaneous routes on hematologic and immunologic responses in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis and mesotheliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5228–5237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.