Abstract

Cell therapies, which include bioartificial liver support and hepatocyte transplantation, have emerged as potential treatments for a variety of liver diseases. Acute liver failure (ALF), acute-on-chronic liver failure, and inherited metabolic liver diseases are examples of liver diseases that have been successfully treated with cell therapies at centers around the world. Cell therapies also have the potential for wide application in other liver diseases, including non-inherited liver diseases and liver cancer, and in improving the success of liver transplantation. Here we briefly summarize current concepts of cell therapy for liver diseases.

Overview

Cell therapies can be categorized by the cell organization and the route of therapy as summarized in Table 1. Extracorporeal or ex vivo therapies, such as the bioartificial liver, are intended for short-term intermittent support of patients in liver failure, while implantable or in vivo therapies, such as cell transplantation, may be used for either short-term, long-term, or permanent liver replacement. Both ex vivo and in vivo forms of cell therapy can be further classified by the cell organization utilized for therapy, which include individually isolated cells, cellular aggregates, synthetically-engineered liver tissue constructs, and naturally occurring liver organs. Synthetic liver tissue, also referred to as cellular scaffold or liver tissue construct, may be vascularized or avascular and supported by diffusion. Liver organs may be used as intact whole organs or divided along well defined lobar and segmental planes. The current review will address each category and subcategory based on features including cell sources (primary hepatocytes, cell lines, stem cells, other progenitor cells, and other non-parenchymal cells types) and liver diseases that may be appropriate for each cell therapy as summarized in Table 2. Sections of this review will summarize historic, current and future forms of these cell therapies with an emphasis on clinical therapies and emerging therapies currently under evaluation in animal models.

Table 1.

Status of Cell Therapies for Liver Disease

| Treatment Options | Ex Vivo (Bioartificial Liver) | In Vivo (Transplantation) |

|---|---|---|

| Cells, individual | 3 | 2 |

| Cells, aggregates (i. e. spheroids) | 2, 4 | 4 |

| Cellular Scaffolds | ||

| avascular | 3, 4 | 3, 4 |

| vascular | 4 | 4 |

| Partial/Split Liver | - | 1 |

| Whole Liver | 3, 4 | 1, 4 |

Status: 1 - Clinically established

Clinically experimental: 2 - current studies, 3 - historic 4 - Preclinical animal studies: rodent or large animal or primate

Table 2.

Organizational Considerations for Review

| Cell Sources | Primary hepatocytes | human adult livers (liver not transplantable, liver resections) human fetal livers healthy donor animals |

| Cell lines | tumor derived (C3A, HepG2) immortalized normal hepatocytes |

|

| Progenitor cells | Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS cells) embryonic stem cells fetal stem cells adult stem cells (oval, mesenchymal stem cells, other) |

|

| Hepatocyte-like | matured in vitro matured in vivo |

|

| Other | lymphocytes, etc. | |

|

| ||

| Liver Abnormality | Acute liver failure Inherited metabolic liver disease Hepatitis (alcoholic, viral) Cirrhosis (cholestatic, other) Liver cancer (hepatocellular, cholangiocarcinoma) Recurrent disease after transplantation Rejection after transplantation |

|

Need for Liver Support Therapies

Tens of millions of patients are affected by liver disease worldwide. Many of these patients can be treated or their disease phenotype can be prevented with therapy involving biologically active living cells. Liver transplantation, the ultimate cell therapy, is presently the only proven treatment for many medically refractory liver diseases including end-stage liver disease and many inherited liver diseases. However, there is a profound shortage of transplantable donor livers. This shortage leads to approximately 40% of listed patients per year not receiving a liver transplant with a significant number of these patients either dying or becoming too sick to transplant (www.unos.org). Therefore, new therapies are needed to supplement whole-organ liver transplantation and reduce the waiting list mortality rate. Furthermore, a number of innovative cell-based therapies and animal model studies of human liver disorders highlight the remarkable regenerative capacity of hepatocytes in vivo. These studies indicate the feasibility of cell therapies as a means of replacing lost or diseased hepatic tissue (1, 2).

Historic Overview

The story of ex vivo cell therapy and in vivo cell transplantation for the treatment of liver disease has many parallels. Treatment of liver failure with an ex vivo device composed of living liver tissue was first reported by Eiseman in 1965 (3). Mata’s et al first performed hepatocyte transplantation in a rodent model in 1976 (4), nine years after the first human solid organ liver transplant was performed by Starzl (5). Many other forms of liver support therapy and artificial liver support were also evaluated over the past 50 years (6). A partial list of these techniques included hemodialysis (7), hepatodialysis (8), extracorporeal heterologous (9) and homologous (10) liver perfusion, cross circulation (11), activated charcoal hemoperfusion (12, 13), simple exchange transfusion (14), and plasmapheresis with plasma exchange (15). At least two positive observations were made from these early clinical trials. First, neurological status or the extent of hepatic encephalopathy often improved, temporarily; however, long-term survival was not significantly impacted in comparison with historical controls (16). As expected, underlying liver disease did influence survival, with noncirrhotic patients having improved survival over cirrhotic patients in the days prior to liver transplantation. Second, toxin removal correlated with recovery from hepatic encephalopathy. In fact, many of these early therapies appeared to have benefit in case reports and small series, but none stood the test of a randomized prospective trial (17). Charcoal hemoperfusion is a good example of an artificial support therapy that appeared hopeful in small series but it could not stand the test of a randomized prospective trial (18).

The limitations of early liver support therapies fell into the categories of safety, immune response, reproducibility, functionality, cell dose and duration of therapy. For example, the reproducibility of heterologous and homologous liver perfusion was highly variable due to the inconsistent quality of organs and the lack of modern preservation techniques. To overcome the safety problems of cross-circulation, in which the patient’s blood was directly exchanged with the blood of another human, a membrane was introduced as a barrier to prevent transmission of infection and to block immune mediated responses. Lessons learned from those early clinical treatments have helped select better and safer membranes for new BAL devices (19–21). As a result, modern BAL devices employ a membrane to avoid the need for immunosuppression yet prevent the harmful immune response of direct contact of blood or plasma with its hepatocytes.

The term bioartificial liver was first coined by Matsumura in 1987 when he perfused a suspension of porcine hepatocytes in an extracorporeal suspension bioreactor (22). Treatment duration of this first BAL device was limited to a few hours due to the death of anchorage dependent hepatocytes in suspension culture. Limitations of suspension culture have been addressed by using spherical aggregates of cells, called hepatocyte spheroids, which will be detailed later in the review. Spheroids allow for greater dose of cells and higher functionality. Spheroid cell aggregates also allow for longer duration of therapy and obviate the need for frozen storage of isolated cells prior to extracorporeal use.

The first successful clinical hepatocyte transplantation was reported by Fox et al in a child with Crigler-Najjar disease (23) nine years after the first BAL report. Since these pioneering studies, many novel clinical applications of both in vivo and ex vivo therapies have been reported in the treatment of ALF, chronic and end-stage liver diseases, and metabolic liver disorders. Moreover, current cell sources are vast in variety. Modern cell sources include primary hepatocytes, immortalized cell lines, and an array of stem cells, including liver stem cells, bone marrow stem cells, embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells.

Cell Sources for liver diseases therapy

Primary Hepatocytes

Isolated hepatocytes have been utilized as the cell source for both extracorporeal and injectable cell transplantation procedures. As an anchorage-dependant epithelial cell type, primary hepatocytes must attach to an extracellular support matrix to avoid programmed cell death, termed anoikis (24). Suspension-based bioartificial liver systems were the first to be tested because of their simplicity and convenience, but these therapies were of limited duration due to the short viability of hepatocytes in suspension even under ideal conditions. In contrast, transplantation of individual hepatocytes allows rapid attachment of transplanted cells to existing extracellular matrix in vivo. Hepatocyte transplantation is a promising alternative to liver transplantation for the treatment of some liver diseases. Primary hepatocytes can be isolated from non-transplantable human livers, human liver resections, human fetal livers, and healthy donor animals such as the pig. Non-transplantable whole human livers are the most common source of primary hepatocytes for cell therapy. But the quality and metabolic/functional activity of the isolated primary hepatocytes is variable. Bhogal et al. reported that the time delay between hepatectomy and beginning of liver perfusion is the most important factor in determining the likelihood of success of the procedure and the shortest possible digestion time is desirable (25). The overall success rate for attempted human hepatocyte isolation from different liver sources was 54% (25). Their data further highlighted that tissue from patients with biliary cirrhosis provides high yields of hepatocytes (success rate 71%), so these cirrhotic livers could be also a valuable source of human hepatocytes for experimental use. Isolated hepatocytes can also be cryopreserved and stored in hepatocyte banks, allowing for scheduled or emergency transplantation. But hepatocytes are highly susceptible to the freeze-thaw process, and the functionality after frozen cryopreservation is significantly reduced compared to freshly isolated hepatocytes. It has been suggested that cryopreservation is a further stimulus for apoptosis of freshly isolated hepatocytes (26). Several cryopreservation methods for hepatocyte have been reported (27–30), but hepatocyte functional activities after thawing are still unsatisfactory and an optimal cryopreservation technique requires further research.

Tumor Cell Lines

A critical barrier to success of hepatocyte transplantation and the bioartificial liver is the limited supply of high-quality human hepatocytes. Conventional methods of obtaining hepatocytes cannot meet clinical demand because of the shortage of livers from which high quality hepatocytes can be isolated, and hepatocytes are not easily maintained in culture for extended periods of time. The demand for human hepatocytes, therefore, heavily outweighs their availability. Hence, some investigators have made immortalized human hepatocytes via spontaneous transformation; telomerase constructs introduction, or retroviral transfection. To date the C3A line, a subclone of the HepG2 hepatoblastoma cell line, is the only human-based cell line that has been tested clinically in a bioartificial liver device named ELAD™ (31–33). These clinical studies have suggested safety as no evidence of C3A cell transmission has ever been reported. Of some concern, C3A cells demonstrate reduced levels of ammonia detoxification and urea cycle activity, P450 activity, and amino acid metabolism when compared to adult porcine hepatocytes (34). Reduced ammonia removal by immortalized C3A hepatocytes appears to be due to reduced expression of its urea cycle genes (35). To enhance their ammonia detoxification activity, the glutamine synthetase gene was transfected into C3A cells and transfected cells showed higher ammonia removal activity in a bioreactor (36). Because of the potential for tumor transmission, the clinical use of immortalized cell lines such as C3A have been limited to extracorporeal devices which possess a membrane to block cell spread to the patient. Of note, a pivotal randomized trial of the ELAD device is ongoing at the time of publication of this review.

Immortalized Hepatocyte Lines from Normal Human Hepatocytes

In an attempt to bypass the limitations associated with tumor cells derived from immortalized human hepatocytes, researchers have tried to immortalize hepatocytes from non-tumor derived hepatocytes. Chen et al transplanted immortalized human fetal hepatocytes (HepCL cells) to prevent ALF in 90% hepatectomized mice. They demonstrated that HepCL cells functioned similar to primary human fetal hepatocytes and showed no tumorigenicity; suggested superiority of HepCL to HepG2 cells with regard to metabolic support during ALF (37). The immortalized human hepatocytes from non-tumor derived hepatocytes may also be useful as a potential source of liver support in bioartificial liver systems.

Xenotransplantation with Primary Pig Hepatocytes

Due to the shortage of human hepatocytes for cell therapies, xenogeneic cells have also been considered as a potential cell source for bioartificial liver systems and for treating liver disease. Primary porcine hepatocytes have been used in several liver support devices undergoing pre-clinical and clinical evaluation. Unlike immortalized cell lines, porcine hepatocytes maintain hepatocyte-specific metabolic function including ammonia detoxification (38). However, concerns of porcine hepatocyte usage are the risk of humoral and cellular immunologic response (39) and potential function mismatch between porcine hepatocyte-released proteins and their human counterparts. Transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus from pig cell to human patient is a potential risk during pig cell therapy. However, no such transmission was identified in a extensive examination of human tissues from pig cell therapies (40).

Stem Cells

Recent advances in cell biology have led to the concept of regenerative medicine, based on the therapeutic potential of stem cells. Stem cells, which are hallmarked by their ability to self-renew and differentiate into a wide variety of cell types, have been proposed as an ideal cell source to generate unlimited numbers of hepatocytes as illustrated in Figure 1. Different types of stem cells are theoretically eligible for liver cell replacement.

Figure 1. Possible sources of cells in the liver.

A variety of cell types can be induced to form the parenchymal cells in the liver. Hepatocytes can divide to produce daughter hepatocytes; bone marrow cells can add genetic material by fusing with hepatocytes. Oval cells are resident precursor cells for cholangiocytes and hepatocytes. Stem cells can produce all cells in the liver. Fetal liver cells are an experimental source for hepatocytes and choloangiocytes. (by permission from John Wiley and Sons (98))

Liver Stem Cells

A large number of studies have utilized liver-derived stem cells including fetal liver stem cells and adult liver stem cells to generate primary hepatocytes (41, 42). Fetal liver stem cells, also named “hepatoblasts”, appear upon differentiation of the hepatic endoderm and growth of the liver bud. Hepatoblasts are bipotent, being able to give rise to both hepatocytes and bile duct cells. Murine hepatoblast cell lines have been established by various research groups, and their capacity to repopulate the liver upon transplantation is well studied in animal models (41). Weber et al reported that human fetal liver cells can be isolated and cultured (43). These cells also engraft and differentiate into mature hepatocytes in situ after transplantation into immunodeficient mice.

The adult liver has a particularly extensive regenerative potential in response to injury and parenchymal loss, mainly granted by mature hepatocytes. However, whenever the replication ability of hepatocytes is experimentally inhibited or impaired by advanced chronic injury, liver regeneration can still be accomplished by the activation, expansion, and differentiation of the so-called “hepatic progenitor/stem cells”. Oval cells represent the majority of these hepatic progenitor cells. Like hepatoblasts, oval cells are also bipotent (42).

Although there have been great advances in liver stem cell biology, these cells are rare within liver tissue as hepatoblasts only comprise about 0.1% of fetal liver mass, and oval cells comprise 0.3% – 0.7% of adult liver mass making isolation of both difficult and expansion unfavorable for large-scale applications (44, 45).

Hepatocyte-like Cells from Bone Marrow-derived Stem Cells

In the last decade, a series of studies suggested that cells derived from the bone marrow could originate hepatocytes. At least four different bone marrow-derived cell populations have been described: hematopoietic stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells, multipotent adult progenitor cells and very small embryonic-like cells. Transplantation of non-liver stem cells, such as bone marrow-derived stem cells, has also demonstrated the feasibility of generating functioning hepatocytes. Hong Li et al demonstrated that adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells can be transduced by recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors, engrafted into recipient livers, contribute to liver regeneration, and serve as a platform for transgene expression without eliciting an immune response (46). Mesenchymal stem cells are rare multipotent residents of the bone marrow and other tissues, such as adipose tissue, that can rapidly expand in culture and are able to develop into several tissue types. Mesenchymal stem cells might become a more suitable source for stem cell-based therapies than hematopoietic stem cells because of their favorable immunological properties, ease of access, and their potential for trans-differentiation.

Hepatocyte-like cells from Annex Stem Cells

Another promising source of human stem cells may be human placental tissues, which contain cells of higher proliferation and differentiation potential than adult stem cells and do not seem to form teratomas or teratocarcinomas in humans. Several studies indicated that umbilical cord and umbilical cord blood, placenta and amniotic fluid are an easily accessible source of pluripotent stem cells, which may be readily available for transplantation, or for further expansion and manipulation prior to cell therapies. Using flow cytometry, histology, immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR for human hepatic markers to monitor human cell engraftment into animals, Piscaglia demonstrated that human umbilical cord blood stem cells could colonize the liver and differentiate into hepatocytes after acute toxic liver damage in NOD/SCID mice and in immunocompetent rats (47, 48).

Hepatocyte-like cells from Embryonic Stem Cells

Other studies have induced embryonic stem cells to differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells. So far, many promising studies have shown the therapeutic potential of differentiated derivatives of embryonic stem cells in ameliorating a range of disease in animal models. These derivatives are able to colonize the injured liver and function as mature hepatocytes (41).

Hepatocyte-like Cells from iPS Cells

Human iPS cells could prove to be an unlimited source of hepatocytes. For clinical application, the all-autologous setting seems to be the most promising approach. Because iPS cells can bypass the ethical concerns of embryo destruction related to the derivation of embryonic stem cells and potential issues of allogenic rejection, iPS cells may represent a more ideal source to produce patient-specific and disease-specific adult cells for future clinical applications.

Hepatocyte-like cells generated from iPS cells have been shown to secrete human albumin, synthesize urea, and express human cytochrome P450 enzymes, which could represent a very promising cell population for future therapeutic transplantation (49).

Differentiated cell types produced from a patient’s iPS cells have many potential therapeutic applications, including their use in tissue replacement and gene therapy. Investigators have recently reported that iPS cells can treat type 1 diabetes and several inherited liver diseases (50). Transplantation of hepatocytes derived from human iPS cells could represent an alternative either to liver transplantation in ALF, or for the correction of genetic disorders resulting in metabolically deficient states.

Hepatocyte-like Cells from Other Sources

Several efforts have been made to generate hepatocyte-like cells from other sources, such as monocyte-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Ehnert et al demonstrated that transplantation of hepatocyte-like cells derived from peripheral blood monocyte may represent a possible therapy for patients suffering from acute or acute-on-chronic liver disease bridging the time for whole organ transplantation or supporting the regeneration of the liver (51).

Expansion Options of Primary Hepatocyte

Although other cell types have shown promise as alternatives to primary hepatocytes, primary hepatocytes continue as the dominant source of cells for liver cell therapy. Unfortunately, isolated primary hepatocytes show little proliferation capacity ex vivo no matter which architectural configuration is employed, and the most significant problem with cultured hepatocytes is that they rapidly lose their differentiated structures and liver-specific functions following isolation. Therefore, research into the most effective culture method for primary hepatocytes continues.

Small Scale: in vitro Primary Hepatocyte Culture Techniques

The most common primary hepatocyte culture technique is to seed the cells as a single layer on collagen gel-coated dishes in conditioned medium. When primary hepatocytes are cultured on a single collagen layer, they produce albumin and urea, and show cytochrome P450 activity, but their liver-specific functions steadily decline within the first week of culture. To mimic the matrix surrounding the hepatocytes in the sinusoid, a second layer of collagen was added on top of the cultured hepatocytes, termed a collagen “sandwich” configuration. This scheme maintains hepatocyte function, polarity and induces distinct apical and lateral membrane formation (52). In an effort to recreate the interactions between parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells, several liver non-parenchymal cells such as fibroblasts, stellate cells, Kupffer cells, and endothelial cells have been co-cultured with hepatocytes and showed remarkable liver-like structure and function (53). Morin et al have shown that parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells self-organize in roller bottles to form simple epithelial structures consisting of an outer layer of biliary epithelial cells, a middle layer of hepatocytes and connective tissue, and an inner layer of endothelial cells (54).

Large Scale: Bioreactor Options for Cell Culture

Generating a system for culturing large numbers of hepatocytes may be required for clinical applications such as the development of a bioartificial liver or hepatic tissue engineering. The bioartificial liver is designed for use either prior to liver transplantation, until recovery of the native liver, or as a chronic supportive therapy. The bioartificial liver functions outside of the patient’s body similar to hemodialysis in the treatment of kidney failure, but is unique in that it contains metabolically active liver cells (i. e., hepatocytes) that provide liver functions to the patient. Hepatocytes are the functional component of bioartificial liver. BAL design configurations include flat-plate membrane, the hollow fiber cartridge, encapsulation technology, and cell aggregates, such as spheroids, either attached to a support or in suspension culture (55).

Flat Membrane Culture Systems

The use of a flat membrane bioreactor allows for control of the internal flow distribution and perfusion of all hepatocytes under a stable oxygen and hormone gradient in vitro. Hepatocytes cultured using this technique demonstrated specific in vivo zonal differentiation characteristics such as the expressions of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in the upstream oxygen-rich region, and cyp2B in the downstream oxygen-poor region. Recently, this system was applied to study the effects of acetaminophen toxicity on metabolically zonated hepatocytes (56).

Hollow Fiber System

Most bioartificial liver devices tested clinically employ hollow fiber cartridges containing either porcine or human hepatocytes. The hollow fiber cartridge provides a large surface area for mass transfer of waste molecules from the patient to hepatocytes in the bioartificial liver. The hollow fibers also serve as a semipermeable barrier to separate cells in these devices from cytotoxic proteins and cells in the patient’s blood. Most cell-based ex vivo devices require an oxygenator membrane in the flow circuit to meet the cell’s large demand for oxygen. Nyberg et al. utilized a device where hepatocytes in a supporting matrix are seeded in the intrafiber space of hollow fibers allowing for oxygenated plasma to flow over the outer surface of the fibers (57). This technology is being used to culture other cell types, including mesenchymal stem cells, embryonic stem cells, and also stem cells in various stages of hepatic differentiation (58).

Encapsulation Technology

Hepatocyte microencapsulation techniques within synthetic semipermeable membranes have been developed to provide physical separation and protection of xenogeneic cells from the recipient’s immune system within a support system. In theory, the biomaterial excludes high molecular weight components of the immune system while allowing free passage of low molecular weight nutrients and oxygen across the semipermeable membranes (59, 60).

Spherical Aggregate Culture Systems

Hepatocyte spheroids, spherical multi-cellular aggregates of hepatocytes measuring greater than 50μm in diameter, provide a useful 3-dimensional tissue construct for cell transplantation and for use in a BAL. Several methods are employed for spheroid formation from mammalian hepatocytes, such as culturing hepatocytes on non-adherent plastic surfaces for self assembly (61), or rotational culture via spinner flasks (62). More recently, Nyberg et al reported preliminary observations that hepatocytes form spheroids spontaneously when rocked in suspension culture (63). Hepatic spheroids as well as encapsulated hepatocyte aggregates can be maintained in suspension culture at high cell density under oxygenated bioreactor conditions. Suspension culture systems can be easily scaled up to cell mass levels appropriate to sustain the patient’s life.

In vivo Incubators: humanized animal liver

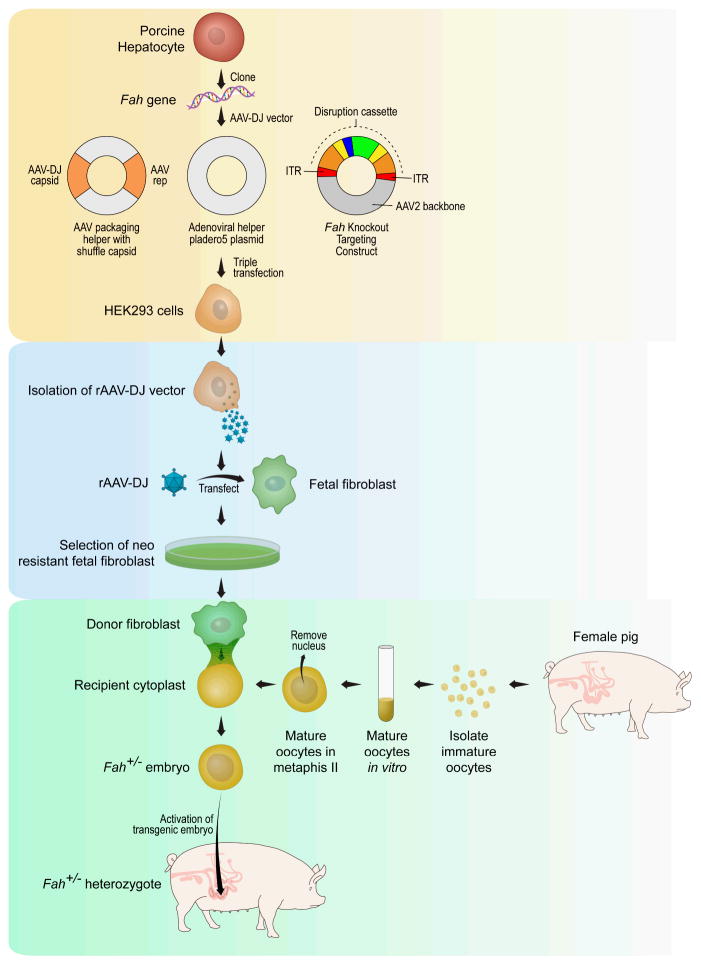

As stated earlier, a large demand exists for an abundant, routinely available, high quality source of human hepatocytes for therapeutic and diagnostic applications. To meet this demand, in vivo (i.e., animal) models were proposed for expanding primary human hepatocytes. However, engraftment of human hepatocytes after transplantation into animals was very low, only corresponding to about 0.5% of the recipient liver mass under normal conditions. Various approaches have been employed to improve engraftment of human hepatocyte in animal models. Repeated hepatocyte transplantation has been shown to increase the number of engrafted cells above 5%, a level sufficient to correct some metabolic defects. Primary adult hepatocytes lose function and viability following isolation and culture, and have limited proliferation potential in vitro. Yet hepatocytes have a remarkable regenerative capacity in vivo. Based on the in vivo properties of hepatocytes, animal models have been developed with the specific intent of selective expansion of transplanted human hepatocytes. One such model is the immunodeficient urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) transgenic mouse (64), in which an Alb promoter directs high-level toxic expression of uPA. The hepatotoxicity in this model creates a permissive environment for the expansion of transplanted hepatocytes, which undergo greater than 12 cell divisions on average. Azuma et al introduced another method whereby primary human hepatocytes were efficiently expanded to near complete (>90%) hepatocyte replacement in livers of mice triply mutant for fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase (Fah), Rag2, and the common γ-chain of the interleukin receptor. In the absence of the protective drug 2- (2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione (NTBC) (65), the native mouse hepatocytes die while transplanted human hepatocytes expand. The unique capacity of expansion of primary human hepatocytes in this model is based on two essential features: extensive and continuous liver injury, and a strong selective advantage for the transplanted cells to survive as compared to the host cells. However, a limitation in the repopulated of FAH-deficient mouse is related to the absolute number of primary human hepatocytes that can be obtained. Thus, an alternative to mice for large-scale expansion of primary human hepatocytes would be a FAH-deficient pig (66). Pigs offer a 1000-fold scale-up in the potential for expansion of primary human hepatocytes. The strategy that we have used for cloning and herd development of heterozygote and homozygote Fah-null pigs is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Schematic of the AAV directed gene targeting and somatic cell nuclear transfer for production of heterozygote Fah-null pigs.

The process of cloning genetic knock-out pigs involves three steps: 1) create the targeting construct with the disruption cassette with production in HEK293 cells (shaded yellow), 2) Select for clones of porcine fetal fibroblasts that have been successfully transfected with the targeting construct (shaded light blue), 3) Produce genetically engineered piglets by somatic cell nuclear transfer – fusion of a targeted porcine fetal fibroblast with an enucleated pig embryo (shaded aqua blue).

Perfusion of Decellularized Liver Matrix and Hepatocytes

Recent progress in hepatic tissue engineering has been hampered by low initial hepatocyte engraftment and insufficient blood supply in vivo. Uygun et al (67) demonstrated a novel approach to generate transplantable liver grafts using decellularized liver matrix. The decellularization process preserves the structural and functional characteristics of the native microvascular network, allowing efficient recellularization of the liver matrix with adult hepatocytes. The recellularized graft supports liver-specific function including albumin secretion, urea synthesis and cytochrome P450 expression at comparable levels to normal liver in vitro. Recellularized liver grafts have been perfused with minimal ischemic damage after transplantation into rats (68). Bao et al developed an intact 3D scaffold of an extracellular matrix derived from a decellularized liver lobe, repopulated with hepatocytes and successfully implanted this tissue construct into the portal system. The tissue-engineered liver provided sufficient volume for transplantation of cell numbers representing up to 10% of whole-liver equivalents. Treatment of extended hepatectomized rats with a tissue-engineered liver improved liver function and prolonged survival. These results provide a proof of principle for the generation of a transplantable liver graft as a potential treatment for liver disease.

Cell Therapies for Liver Failure

The potential indications for cell-based therapies are ALF, acute on chronic liver failure, and acute decompensation after liver resection. Acute on chronic liver failure is defined as an acute deterioration of a chronic liver disease. Pareja et al have demonstrated that hepatocyte transplantation may decrease the mortality rate among patients with end-stage liver disease awaiting liver transplantation, or possibly even avoid it among cases of ALF (69). So far, a total of more than thirty cases of hepatocyte transplantation in children and adults have been reported. In addition to hepatocyte transplantation for ALF treatment, Jin et al have suggested that bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation combined with HGF administration also exhibits a synergistic beneficial effect on improving both functional and histological liver recovery in a mouse model of ALF (70). Moreover, stem cells including mesenchymal stem cells show promising roles in attenuating ALF. Parekkadan et al provide the first experimental evidence of the medicinal use of mesenchymal stem cells-derived molecules in the treatment of an inflammatory condition and support the role of chemokines and altered leukocyte migration as a novel therapeutic modality for ALF (71). Shi et al demonstrated that encapsulation of hepatocytes and mesenchymal stem cells improved hepatocyte-specific functions in vitro and in vivo and that transplantation of such cells might be a promising strategy for cell-based therapy for acute liver diseases (72).

Another cell-based therapy for ALF is the bioartificial liver. The bioartificial liver system removes toxins by filtration or adsorption (artificial liver) while performing biotransformation and synthetic functions of biochemically active hepatocytes. Several bioartificial liver modalities have been tested in the clinical arena (73–75), and other improved configurations are under development (76, 77).

Cell Therapies for Inherent Liver Diseases

A major indication for hepatocyte transplantation is inherited metabolic liver diseases in children. Hepatocyte transplantation has been performed as a treatment for inherent liver diseases, either for bridging to whole organ transplantation or for long-term correction of the underlying metabolic deficiency (23). Some genetic diseases that have been treated by hepatocyte transplantation include familial hypercholesterolemia, Crigler–Najjar syndrome type I, glycogen storage disease type 1a, urea cycle defects and congenital deficiency of coagulation factor VII. Dhawan and Waelzlein have observed that the most encouraging outcomes of hepatocyte transplantation have been in patients with inborn errors of metabolism (78). Research regarding hepatocyte transplantation for inherent liver diseases is actively being pursued. In a thorough review, Flohr et al summarize the animal experiments using hepatocyte transplantation to treat inherent liver diseases (79).

Development of iPS cells from adult somatic tissues may provide a unique approach to create patient and disease-specific treatment for inherent liver diseases. iPS-based cell therapies have been applied in several animal models of liver-based metabolic disorders, with encouraging results (80). An example of how to potentially individualize the treatment of inherited liver disease using iPS cell technologies is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary schematic of approaches to hepatocyte transplantation for treatment of inherited metabolic disease. The standard procedure under clinical evaluation uses cryopreserved human hepatocytes from donor human liver (shaded green). Alternative procedures to produce transplantable hepatocyte-like cells from human stem cells are also under development. Also under development are individualized approaches to the treatment of inherited metabolic disease by ex vivo gene therapy and in vivo cell transplantation. The individualized approach would involve production of hepatocytes from the patients own cells and thereby avoid the need for immunosuppression. Patient derived hepatocytes may be produced in vitro or expanded in vivo in genetically engineered animals such as the FAH-deficient pig. Patient derived hepatocytes could also be utilized in an extracorporeal bioartificial liver.

Cell Therapies for Non-inherent Liver Diseases

Cell therapy for Hepatitis

Fernandez-Ruiz et al reported that genetic engineering of endothelial progenitor cells to overexpress cytokine cardiotrophin-1 enhances the hepatoprotective properties of endothelial progenitor cells and constitutes a therapy that deserves consideration for fulminant hepatitis (81). Longhi and Protzer used autoantigen-specific regulatory T cells (Tregs) and engineered “designer” T cells, respectively, as a potential tool for immune-tolerance reconstitution in type-2 autoimmune hepatitis and chronic hepatitis B (82). Farag et al demonstrated that vaccination with ex vivo activated dendritic cells may be a promising tool for therapeutic or prophylactic approaches against the Hepatitis B virus (83).

Cell Therapy for Liver Cirrhosis

Chronic liver disease is usually accompanied by progressive fibrosis. Paradoxically, the intravenous injection of bone marrow cells, particularly mesenchymal stem cells appears to be therapeutically useful to animals with ongoing hepatic damage. Phase I trials involving the injection of autologous bone marrow cells to cirrhotic patients have reported modest improvements in clinical scores (84). Terai et al reported an improvement in Child-Pugh score and albumin levels in 9 patients with cirrhosis, who received portal vein infusion of unsorted autologous mesenchymal stem cells (85). Also, a significant increase of liver function post liver resection has been documented in patients with cirrhosis pre-treated with autologous mesenchymal stem cells transplantation (86). Transplanted mesenchymal stem cells have been shown to improve insulin resistance thereby contributing to glucose homeostasis and amelioration of liver cirrhosis in rodent models of CCl4-induced liver disease (87). Autologous peripheral bone marrow cells transplantation has also been shown to be a novel and potentially beneficial treatment for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis (88).

Cell Therapy for Liver Cancer

The possible therapeutic interest of bone marrow stem cells in liver cancer was first investigated in 2005 when autologous CD133+ bone marrow stem cells were transplanted via the portal vein in patients with liver cancer prior to undergoing portal venous embolization. Following embolization, these patients underwent extensive liver resection that caused a subsequent degree of clinical improvement (89). Fürst et al concluded that a combination of portal vein embolization and CD133+ bone marrow stem cells administration increased the degree of hepatic regeneration in comparison with embolization alone in patients with malignant liver lesions (90). Similarly, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma first receiving autologous bone marrow stem cells experience a significant increase of liver function post liver resection (86). Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells transplantation produces a graft-versus-tumor effect in patients with solid tumors. The most optimal graft-versus-tumor effect was demonstrated in patients with advanced primary liver cancer who had previously undergone liver transplantation. Suppression of the tumor and its progression may be undertaken before and after stem cell transplantation combined with adjuvant cell therapies, as donor-derived immune cells allow the allogeneic graft-versus-tumor effect (91). There is no survival data currently. More clinical trials are needed to evaluate such issues in the future.

Cell Therapy for Inducing Immunity Tolerance after liver transplantation

Liver transplantation has evolved over the past four decades into the most effective method to treat end-stage liver failure. Despite this advancing evolution, liver transplantation has numerous limitations, including rejection. Although immunosuppressive drugs are highly effective in protecting allografts from acute rejection, the current immunosuppression targets all arms of the immune system. In addition to the high cost, immunosuppression has side effects that can worsen patient morbidity and mortality. Therefore, it is important to induce tolerance special to the donor antigen allowing for the avoidance of immunosuppression. A couple of alternatives to pharmacologic immunosuppression are described in the following paragraphs.

1. Regulatory T cels (Tregs)

Compelling evidence from animal transplant models and clinic data show that manipulating the balance between regulatory and responder T cells is a potentially effective strategy to control immune responsiveness after transplantation as Tregs play a critical role in promoting immunologic unresponsiveness to allogeneic organ transplants. CD4+CD25+ Tregs represent a subset of T cells without specific antigen stimulation that can suppress immune responses through a mechanism of cell-to-cell contact. Thus, CD4+CD25+ Tregs may have effects on both induction and maintenance of tolerance. Such studies could help to clarify whether the enhancement of Tregs also correlates with the immunologic features associated with clinical transplant tolerance (92).

2. Mesenchymal stem cells

Mesenchymal stem cells exert strong immunosuppressive effects including the suppression of B, T, and NK cell activity, the complement pathway, and the differentiation and maturation of dendritic cells - the most important antigen-processing cells. Mesenchymal stem cells also exert a profound inhibitory effect on T-cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, a major breakthrough recently was the discovery that mesenchymal stem cells induce the generation of Tregs both in vivo and in vitro (93–95).

Cell Therapy for Liver Regeneration

Living donor liver transplantation has been developed to increase the number of donor livers. However, living donor liver transplantation makes use of small-for-size liver transplantation. Thus, small-for-size liver transplantation makes use of size mismatched grafts that may not compensate for the recipient’s required level of liver function. The size of the graft in small-for-size liver transplantation has an inverse relationship to the degree of non-function. Poorly functioning grafts show delayed and impaired regeneration, which frequently leads to liver failure. Therefore, immediate regeneration of the mismatched graft is required in living donor liver transplantation. Current work has established the feasibility of using iPS cells generated in a clinically acceptable fashion for rapid and stable liver regeneration (96). Similarly, mesenchymal stem cell-based therapies may provide a novel approach for hepatic regeneration and hepatocyte differentiation and thereby support hepatic function in diseased individuals (97).

Conclusions

Despite notable achievements of hepatocyte transplantation and bioartificial liver therapy in treating various liver diseases, either as a bridge to transplantation or to allow recovery without transplantation, the limited supply of primary human hepatocytes remains a major barrier to successful expansion of liver cell therapies. Stem cells are promising tools for the treatment of many liver diseases and to the service of regenerative medicine. However, the in vivo functionality of stem cells-derived hepatocyte-like cells is largely unknown. Normal differentiation of iPS cells to hepatocyte-like cells and on to mature hepatocytes has yet to be reported. It is likely that normal and complete differentiation of liver progenitor cells to mature hepatocytes requires an in vivo milieu. Moreover, critical aspects need to be addressed including the long-term safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of engraftment of primary hepatocytes and stem cells in diseased human livers. Efficacy of novel cell-based treatments must be established in clinical practice. Clinical trials are needed to evaluate unresolved issues of liver cell therapies. These hurdles are likely to be overcome and will be associated with wider application of cell-based therapy in the treatment of liver diseases. Meanwhile, parallel strategies of increasing organ donation are also required in conjunction with advances in cell therapies to combat liver disease, such strategies include living donor and split liver transplantation, and the tissue engineered transplantable liver.

Acknowledgments

Research Support Provided By: Marriott Foundation, Coulter Foundation, NIH-R01-DK56733

Abbreviations

- AAV

- ALF

- iPS

- FAH

- NTBC

References

- 1.Kobayashi N, Noguchi H, Fujiwara T, Westerman KA, Leboulch P, Tanaka N. Establishment of a highly differentiated immortalized adult human hepatocyte cell line by retroviral gene transfer. Transplantation proceedings. 2000;32(7):2368–9. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)01702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han B, Lu Y, Meng B, Qu B. Cellular loss after allogenic hepatocyte transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87:2009. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181919212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eiseman B, Liem DS, Raffucci F. Heterologous liver perfusion in treatment of hepatic failure. Ann Surg. 1965;162:329–45. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196509000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matas AJ, Sutherland DE, Steffes MW, Mauer SM, Sowe A, Simmons RL, et al. Hepatocellular transplantation for metabolic deficiencies: decrease of plasms bilirubin in Gunn rats. Science. 1976;192(4242):892–4. doi: 10.1126/science.818706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starzl TE, Marchioro TL, Porter KA, Brettschneider L. Homotransplantation of the liver. Transplantation. 1967;5(4 Suppl):790–803. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196707001-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyberg SL, Shatford RA, Hu W-S, Payne WD, Cerra FB. Hepatocyte culture systems for artificial liver support: Implications for critical care medicine (bioartificial liver support) Critical Care Medicine. 1992;20(8):1157–68. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiley JE, Pender JC, Welch HF, Welch CS. Ammonia intoxication treated by hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 1958;259(24):1156–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195812112592403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimoto S. The artificial liver experiments and clinical application. ASAIO J. 1959;5:102–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abouna GM, Serrou B, Boehmig HG, Amemiya H, Martineau G. Long-term hepatic support by intermittent multi- species liver perfusions. Lancet. 1970;2(1):391–96. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sen P, Bhalerao R, Parulkar G, Samsi A, Shah B, Kinare S. Use of isolated perfused cadaveric liver in the management of hepatic failure. Surgery. 1966;59:774–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnell JM, Dawborn JK, Epstein RB, Gutman RA, Leinbach GE, Thomas ED, et al. Acute hepatic coma treated by cross-circulation or exchange transfusion. N Engl J Med. 1967;276(17):935–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196704272761701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang T. Haemoperfusions over microencapsulated adsorbent in a patient with hepatic coma. Lancet. 1972;2:1371–72. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92821-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gazzard B, Weston M, Murray-Lyon I, Flax H, Record C, Portmann B, et al. Charcoal haemoperfusion in the treatment of fulminant hepatic failure. Lancet. 1974;i:1301–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90678-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trey M, Burns D, Saunders S. Treatment of hepatic coma in cirrhosis by exchange blood transfusion. N Engl J Med. 1966;274:473–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196603032740901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabin S, Merritt J. Treatment of hepatic coma in cirrhosis by plasmapheresis and plasma infusion. Ann Intern Med. 1968;68:1–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-68-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakela J, Lange S, Ludwig J, Baldus W. Fulminant hepatitis: Mayo Clinic experience with 34 cases. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1985;60:289–92. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyberg SL, Peshwa MV, Payne WD, Hu WS, Cerra FB. Evolution of the bioartificial liver: the need for randomized clinical trials. American journal of surgery. 1993;166(5):512–21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Grady J, Gimson A, O’Brien C, Pucknell A, Hughes R, Williams R. Controlled trials of charcoal hemoperfusion and prognostic factors in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1186–92. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyberg SL, Platt JL, Shirabe K, Payne WD, Hu WS, Cerra FB. Immunoprotection of xenocytes in a hollow fiber bioartificial liver. ASAIO journal. 1992;38(3):M463–7. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199207000-00077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyberg S, Hibbs J, Hardin J, Germer J, Persing D. Transfer of porcine endogenous retrovirus across hollow fiber membranes: significance to a bioartificial liver. Transplantation. 1999;67:1251–55. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199905150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyberg SL, Yagi T, Matsushita T, Hardin J, Grande JP, Gibson LE, et al. Membrane barrier of a porcine hepatocyte bioartificial liver. Liver transplantation: official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society. 2003;9(3):298–305. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumura K, Guevara G, Huston H, Hamilton W, Rikimaru M, Yamasaki G, et al. Hybrid bioartificial liver in hepatic failure: preliminary clinical report. Surgery. 1987;101:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox IJ, Chowdhury JR, Kaufman SS, Goertzen TC, Chowdhury NR, Warkentin PI, et al. Treatment of the Crigler-Najjar syndrome type I with hepatocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(20):1422–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805143382004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frisch SM, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1994;124(4):619–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhogal RH, Hodson J, Bartlett DC, Weston CJ, Curbishley SM, Haughton E, et al. Isolation of primary human hepatocytes from normal and diseased liver tissue: a one hundred liver experience. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e18222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yagi T, Hardin JA, Valenzuela YM, Miyoshi H, Gores GJ, Nyberg SL. Caspase inhibition reduces apoptotic death of cryopreserved porcine hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2001;33(6):1432–40. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd TD, Orr S, Berry DP, Dennison AR. Development of a protocol for cryopreservation of hepatocytes for use in bioartificial liver systems. Annals of clinical and laboratory science. 2004;34(2):165–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephenne X, Najimi M, Smets F, Reding R, de Ville de Goyet J, Sokal EM. Cryopreserved liver cell transplantation controls ornithine transcarbamylase deficient patient while awaiting liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(8):2058–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katenz E, Vondran R, Schwartlander R, Pless G, Gong X, Cheng X, et al. Cryopreservation of primary human hepatocytes: the benefit of trehalose as an additional cryoprotective agent. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:38–45. doi: 10.1002/lt.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grondin M, Hamel F, Averill-Bates DA, Sarhan F. Wheat proteins enhance stability and function of adhesion molecules in cryopreserved hepatocytes. Cell Transplant. 2009;18(1):79–88. doi: 10.3727/096368909788237104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duan Z, Zhang J, Xin S, Chen J, He D, Brotherton J, et al. Interim Results of Randomized Controlled Trial of ELAD™ in Acute on Chronic Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2007;46(4 Suppl 1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellis AJ, Hughes RD, Wendon JA, Dunne J, Langley PG, Kelly JH, et al. Pilot-controlled trial of the extracorporeal liver assist device in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 1996;24(6):1446–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Millis JM, Cronin DC, Johnson R, Conjeevaram H, Conlin C, Trevino S, et al. Initial experience with the modified extracorporeal liver-assist device for patients with fulminant hepatic failure: system modifications and clinical impact. Transplantation. 2002;74(12):1735–46. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200212270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Sun J, Li L, Mears D, Horvat M, Sheil AG. Comparison of porcine hepatocytes with human hepatoma (C3A) cells for use in a bioartificial liver support system. Cell Transplant. 1998;7(5):459–68. doi: 10.1177/096368979800700505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mavri-Damelin D, Damelin LH, Eaton S, Rees M, Selden C, Hodgson HJ. Cells for bioartificial liver devices: the human hepatoma-derived cell line C3A produces urea but does not detoxify ammonia. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;99(3):644–51. doi: 10.1002/bit.21599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enosawa S, Miyashita T, Fujita Y, Suzuki S, Amemiya H, Omasa T, et al. In vivo estimation of bioartificial liver with recombinant HepG2 cells using pigs with ischemic liver failure. Cell transplantation. 2001;10(4–5):429–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, Li J, Liu X, Zhao W, Wang Y, Wang X. Transplantation of immortalized human fetal hepatocytes prevents acute liver failure in 90% hepatectomized mice. Transplantation proceedings. 2010;42(5):1907–14. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonavita AG, Quaresma K, Cotta-de-Almeida V, Pinto MA, Saraiva RM, Alves LA. Hepatocyte xenotransplantation for treating liver disease. Xenotransplantation. 2010;17(3):181–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baquerizo A, Mhoya A, Kearns-Jonker M, Arnaout W, Shackleton C, Busuttil R, et al. Characterization of human xenoreactive antibodies in liver failure patients exposed to pig hepatocytes after bioartificial liver treatment. Transplantation. 1999;67:5–18. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199901150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paradis K, Langjord G, Long Z, Heneine W, Sandstrom P, Switzer W, et al. Search for cross-species transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus in patients treated with living pig tissue. Science. 1999;285:1236–41. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zaret KS, Grompe M. Generation and regeneration of cells of the liver and pancreas. Science. 2008;322(5907):1490–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1161431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazaro C, Rhim J, Yamada Y, Fausto N. Generation of hepatocytes from oval cell precursors in culture. Cancer Research. 1998;58:5514–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weber A, Touboul T, Mainot S, Branger J, Mahieu-Caputo D. Human foetal hepatocytes: isolation, characterization, and transplantation. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;640:41–55. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-688-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmelzer E, Wauthier E, Reid LM. The phenotypes of pluripotent human hepatic progenitors. Stem Cells. 2006;24(8):1852–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haridass D, Yuan Q, Becker PD, Cantz T, Iken M, Rothe M, et al. Repopulation efficiencies of adult hepatocytes, fetal liver progenitor cells, and embryonic stem cell-derived hepatic cells in albumin-promoter-enhancer urokinase-type plasminogen activator mice. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(4):1483–92. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H, Zhang B, Lu Y, Jorgensen M, Petersen B, Song S. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell-based liver gene delivery. J Hepatol. 2011;54(5):930–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piscaglia AC, Campanale M, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G. Stem cell-based therapies for liver diseases: state of the art and new perspectives. Stem Cells Int. 2010;2010:259461. doi: 10.4061/2010/259461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di Campli C, Piscaglia AC, Pierelli L, Rutella S, Bonanno G, Alison MR, et al. A human umbilical cord stem cell rescue therapy in a murine model of toxic liver injury. Digestive and liver disease: official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2004;36(9):603–13. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Si-Tayeb K, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, Li J, Battle MA, Duris C, et al. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):297–305. doi: 10.1002/hep.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rashid ST, Corbineau S, Hannan N, Marciniak SJ, Miranda E, Alexander G, et al. Modeling inherited metabolic disorders of the liver using human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(9):3127–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI43122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ehnert S, Seeliger C, Vester H, Schmitt A, Saidy-Rad S, Lin J, et al. Autologous Serum improves Yield and Metabolic Capacity of Monocyte-derived Hepatocyte-like Cells: Possible Implication for Cell Transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.3727/096368910X550224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taguchi K, Matsushita M, Takahashi M, Uchino J. Development of a bioartificial liver with sandwiched-cultured hepatocytes between two collagen gel layers. Artif Organs. 1996;20(2):178–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1996.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kan P, Miyoshi H, Ohshima N. Perfusion of medium with supplemented growth factors changes metabolic activities and cell morphology of hepatocyte-nonparenchymal cell coculture. Tissue Eng. 2004;10(9–10):1297–307. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michalopoulos GK, Bowen WC, Mule K, Stolz DB. Histological organization in hepatocyte organoid cultures. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(5):1877–87. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63034-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diekmann S, Bader A, Schmitmeier S. Present and Future Developments in Hepatic Tissue Engineering for Liver Support Systems: State of the art and future developments of hepatic cell culture techniques for the use in liver support systems. Cytotechnology. 2006;50(1–3):163–79. doi: 10.1007/s10616-006-6336-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nahmias Y, Berthiaume F, Yarmush ML. Integration of technologies for hepatic tissue engineering. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2007;103:309–29. doi: 10.1007/10_029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nyberg SL, Shatford RA, Peshwa MV, White JG, Cerra FB, Hu WS. Evaluation of a hepatocyte-entrapment hollow fiber bioreactor: a potential bioartificial liver. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1993;41(2):194–203. doi: 10.1002/bit.260410205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miki T, Ring A, Gerlach J. Hepatic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells is promoted by three-dimensional dynamic perfusion culture conditions. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2011;17(5):557–68. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2010.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Orive G, Hernandez RM, Gascon AR, Igartua M, Pedraz JL. Development and optimisation of alginate-PMCG-alginate microcapsules for cell immobilisation. Int J Pharm. 2003;259(1–2):57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weber A, Groyer-Picard MT, Franco D, Dagher I. Hepatocyte transplantation in animal models. Liver Transpl. 2009;15(1):7–14. doi: 10.1002/lt.21670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Landry J, Bernier D, Ouellet C, Goyette R, Marceau N. Spheroidal aggregate culture of rat liver cells: histotypic reorganization, biomatrix deposition, and maintenance of functional activities. J Cell Biol. 1985;101(3):914–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sakai Y, Naruse K, Nagashima I, Muto T, Suzuki M. Large-scale preparation and function of porcine hepatocyte spheroids. The International journal of artificial organs. 1996;19(5):294–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nyberg SL, Hardin J, Amiot B, Argikar UA, Remmel RP, Rinaldo P. Rapid, large-scale formation of porcine hepatocyte spheroids in a novel spheroid reservoir bioartificial liver. Liver Transpl. 2005;11(8):901–10. doi: 10.1002/lt.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meuleman P, Libbrecht L, De Vos R, de Hemptinne B, Gevaert K, Vandekerckhove J, et al. Morphological and biochemical characterization of a human liver in a uPA-SCID mouse chimera. Hepatology. 2005;41(4):847–56. doi: 10.1002/hep.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Azuma H, Paulk N, Ranade A, Dorrell C, Al-Dhalimy M, Ellis E, et al. Robust expansion of human hepatocytes in Fah-/-/Rag2-/-/Il2rg-/- mice. Nature biotechnology. 2007;25(8):903–10. doi: 10.1038/nbt1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hickey R, Lillegard J, Fisher J, McKenzie T, Hofherr S, Finegold M, et al. Efficient production of Fah-null heterozygote pigs by chimeric adeno-associated virus-mediated gene knockout and somatic cell nuclear transfer. Hepatology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hep.24490. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uygun BE, Soto-Gutierrez A, Yagi H, Izamis ML, Guzzardi MA, Shulman C, et al. Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularized liver graft using decellularized liver matrix. Nat Med. 2010;16(7):814–20. doi: 10.1038/nm.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bao J, Shi Y, Sun H, Yin X, Yang R, Li L, et al. Construction of a Portal Implantable Functional Tissue Engineered Liver using Perfusion-decellularized Matrix and Hepatocytes in Rats. Cell transplantation. 2010 doi: 10.3727/096368910X536572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pareja E, Cortes M, Bonora A, Fuset P, Orbis F, Lopez R, et al. New alternatives to the treatment of acute liver failure. Transplantation proceedings. 2010;42(8):2959–61. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jin SZ, Meng XW, Sun X, Han MZ, Liu BR, Wang XH, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor promotes liver regeneration induced by transfusion of bone marrow mononuclear cells in a murine acute liver failure model. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parekkadan B, van Poll D, Suganuma K, Carter EA, Berthiaume F, Tilles AW, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules reverse fulminant hepatic failure. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(9):e941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shi XL, Zhang Y, Gu JY, Ding YT. Coencapsulation of hepatocytes with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells improves hepatocyte-specific functions. Transplantation. 2009;88(10):1178–85. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181bc288b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nyberg S, Misra S. Hepatocyte liver-assist systems - clinical update. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1998;73:765–71. doi: 10.4065/73.8.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Demetriou AA, Brown RS, Jr, Busuttil RW, Fair J, McGuire BM, Rosenthal P, et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter, controlled trial of a bioartificial liver in treating acute liver failure. Ann Surg. 2004;239(5):660–7. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124298.74199.e5. discussion 7–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McKenzie TJ, Lillegard JB, Nyberg SL. Artificial and bioartificial liver support. Seminars in liver disease. 2008;28(2):210–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1073120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee WM, Squires RH, Jr, Nyberg SL, Doo E, Hoofnagle JH. Acute liver failure: Summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2008;47(4):1401–15. doi: 10.1002/hep.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sussman NL, McGuire BM, Kelly JH. Hepatic assist devices: will they ever be successful? Current gastroenterology reports. 2009;11(1):64–8. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dhawan A, Puppi J, Hughes R, Mitry R. Human hepatocyte transplantation: current experience and future challenges. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology Hepatology. 2010;7:288–98. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Flohr TR, Bonatti H, Jr, Brayman KL, Pruett TL. The use of stem cells in liver disease. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(1):64–71. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328320fd7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chun YS, Chaudhari P, Jang YY. Applications of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells; focused on disease modeling, drug screening and therapeutic potentials for liver disease. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6(7):796–805. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fernandez-Ruiz V, Kawa M, Berasain C, Iniguez M, Schmitz V, Martinez-Anso E, et al. Treatment of murine fulminant hepatitis with genetically engineered endothelial progenitor cells. J Hepatol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Longhi MS, Hussain MJ, Kwok WW, Mieli-Vergani G, Ma Y, Vergani D. Autoantigen-specific regulatory T cells, a potential tool for immune-tolerance reconstitution in type-2 autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;53(2):536–47. doi: 10.1002/hep.24039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Farag MM, Hoyler B, Encke J, Stremmel W, Weigand K. Dendritic cells can effectively be pulsed by HBVsvp and induce specific immune reactions in mice. Vaccine. 2010;29(2):200–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alison MR, Choong C, Lim S. Application of liver stem cells for cell therapy. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18(6):819–26. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Terai S, Ishikawa T, Omori K, Aoyama K, Marumoto Y, Urata Y, et al. Improved liver function in patients with liver cirrhosis after autologous bone marrow cell infusion therapy. Stem Cells. 2006;24(10):2292–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ismail A, Fouad O, Abdelnasser A, Chowdhury A, Selim A. Stem cell therapy improves the outcome of liver resection in cirrhotics. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41(1):17–23. doi: 10.1007/s12029-009-9092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jung KH, Uhm YK, Lim YJ, Yim SV. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve glucose homeostasis in rats with liver cirrhosis. Int J Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Han Y, Yan L, Han G, Zhou X, Hong L, Yin Z, et al. Controlled trials in hepatitis B virus-related decompensate liver cirrhosis: peripheral blood monocyte transplant versus granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor mobilization therapy. Cytotherapy. 2008;10(4):390–6. doi: 10.1080/14653240802129901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.am Esch JS, 2nd, Knoefel WT, Klein M, Ghodsizad A, Fuerst G, Poll LW, et al. Portal application of autologous CD133+ bone marrow cells to the liver: a novel concept to support hepatic regeneration. Stem Cells. 2005;23(4):463–70. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Furst G, Schulte am Esch J, Poll LW, Hosch SB, Fritz LB, Klein M, et al. Portal vein embolization and autologous CD133+ bone marrow stem cells for liver regeneration: initial experience. Radiology. 2007;243(1):171–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431060625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Conrad R, Remberger M, Cederlund K, Ringden O, Barkholt L. A comparison between low intensity and reduced intensity conditioning in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for solid tumors. Haematologica. 2008;93(2):265–72. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martinez-Llordella M, Lozano JJ, Puig-Pey I, Orlando G, Tisone G, Lerut J, et al. Using transcriptional profiling to develop a diagnostic test of operational tolerance in liver transplant recipients. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(8):2845–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI35342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhou Y, Yuan J, Zhou B, Lee AJ, Ghawji M, Jr, Yoo TJ. The therapeutic efficacy of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells on experimental autoimmune hearing loss in mice. Immunology. 2011;133(1):133–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03421.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shi M, Liu ZW, Wang FS. Immunomodulatory properties and therapeutic application of mesenchymal stem cells. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2011;164(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ghannam S, Pene J, Torcy-Moquet G, Jorgensen C, Yssel H. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit human Th17 cell differentiation and function and induce a T regulatory cell phenotype. Journal of immunology. 2010;185(1):302–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Espejel S, Roll GR, McLaughlin KJ, Lee AY, Zhang JY, Laird DJ, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes have the functional and proliferative capabilities needed for liver regeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(9):3120–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI43267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ishikawa T, Banas A, Hagiwara K, Iwaguro H, Ochiya T. Stem cells for hepatic regeneration: the role of adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010;5(2):182–9. doi: 10.2174/157488810791268636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karp S. Clinical implications of advances in the basic science of liver repair and regeneration. Am J Transpl. 2009;9:1973–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]