Abstract

Bacterial lipoproteins play a crucial role in virulence in some Gram-positive bacteria. However, the role of lipoprotein biosynthesis in Bacillus anthracis is unknown. We created a B. anthracis mutant strain altered in lipoproteins by deleting the lgt gene encoding the enzyme prolipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase, which attaches the lipid anchor to prolipoproteins. 14C-palmitate labeling confirmed that the mutant strain lacked lipoproteins, and hydrocarbon partitioning showed it to have decreased surface hydrophobicity. The anthrax toxin proteins were secreted from the mutant strain at nearly the same levels as from the wild-type strain. The TLR2-dependent TNF-α response of macrophages to heat-killed lgt mutant bacteria was reduced. Spores of the lgt mutant germinated inefficiently in vitro and in mouse skin. As a result, in a murine subcutaneous infection model, lgt mutant spores had markedly attenuated virulence. In contrast, vegetative cells of the lgt mutant were as virulent as those of the wild-type strain. Thus, lipoprotein biosynthesis in B. anthracis is required for full virulence in a murine infection model.

Keywords: bacterial lipoprotein, prolipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase, anthrax, Bacillus anthracis, spores, germination, Toll-like receptor 2, lgt

Introduction

Bacillus anthracis is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium and the causative agent of anthrax. B. anthracis undergoes a developmental life cycle, alternating between two distinct forms, spores and vegetative cells. Spores are metabolically dormant and can survive for long periods under harsh conditions. However, once they gain access to an animal host, the spores germinate and grow out as vegetative bacteria (Setlow, 2003). Vegetative cells secrete several virulence factors, most prominently the anthrax toxins, which are composed of the three proteins, protective antigen (PA), lethal factor (LF), and edema factor (EF). These proteins combine to form lethal toxin (LT, the combination of PA and LF) and edema toxin (ET, the combination of PA and EF) (Leppla, 2006; Young and Collier, 2007). The toxins individually and cooperatively attenuate the host innate immune system, allowing massive bacteremia and a resulting toxemia that rapidly kills the host (for reviews see (Moayeri and Leppla, 2009; Moayeri and Leppla, 2011)).

Microbial lipoproteins are expressed on the bacterial cell surface and have important functions in the growth and survival of bacteria. These include substrate binding for ABC transport systems, processing of exported proteins, sporulation, and germination (Kontinen and Sarvas, 1993; Khandavilli et al., 2008; Igarashi et al., 2004; Deka et al., 2006; Dartois et al., 1997; Hutchings et al., 2009), as recently reviewed (Kovacs-Simon et al., 2011). Microbial lipoproteins are synthesized as precursors carrying a conserved sequence termed a “lipobox” at the C-terminus of the signal peptide. A diacylglyceryl moiety is transferred to the cysteine residue within the lipobox by lipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase (Lgt), and the signal peptide of the prolipoprotein is then cleaved by the signal peptidase (Tokunaga et al., 1982; Hayashi et al., 1985). In Gram-negative bacteria, lipoproteins are further modified by N-acyltransferase (Lnt), which transfers an N-acyl group to the diacyl-glyceryl cysteine, yielding mature triacylated lipoproteins, which are then often transferred to the outer membrane (Robichon et al., 2005). Although an equivalent enzyme has not been found in Gram-positive bacteria, some N-acylation of lipoproteins was reported to occur in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus (Hayashi et al., 1985; Navarre et al., 1996). The lipoprotein biosynthetic pathway is essential for growth of Gram-negative bacteria, but is dispensable for growth of Gram-positive bacteria such as B. subtilis, S. aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae (Stoll et al., 2005; Petit et al., 2001; Leskela et al., 1999).

In an infected animal host, microbial lipoproteins are recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which play a central role in the innate immune system by sensing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (Akira et al., 2006). MyD88 is a crucial adaptor protein in TLR signal transduction except that occurring through TLR3. MyD88-deficient mice have increased susceptibility to B. anthracis (Okugawa et al., 2011). TLR2, one of the TLR family proteins, is the primary receptor recognizing diacylated and triacylated lipoproteins and leading to induction of cytokine and chemokine synthesis (Takeuchi et al., 2002; Takeuchi et al., 2001). Inactivation of lgt eliminates lipoproteins and allows bacteria to escape from TLR recognition. As a result Lgt deficiency in bacteria such as S. aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae produces a hypervirulent phenotype in mouse infection models (Henneke et al., 2008; Bubeck Wardenburg et al., 2006). In contrast, Lgt-deficient mutants of Listeria monocytogenes and S. pneumoniae are attenuated in virulence (Petit et al., 2001; Baumgartner et al., 2007). Thus, microbial lipoproteins appear to have species-specific roles in virulence.

In this study, we investigated the role of lipoproteins in B. anthracis. We constructed a B. anthracis lgt mutant that was unable to carry out lipid modification of prelipoproteins and used this to investigate the role of lipoprotein biosynthesis in B. anthracis.

Results

Identification of candidate lipoproteins in B. anthracis

The programs ScanProsite and G+LPPv2 identified 145 candidate lipoproteins in the genome of the B. anthracis Ames 35 strain. Because the Ames strain sequence does not include the B. anthracis pXO1 and pXO2 plasmid sequences, these sequences were analyzed from the B. anthracis Ames Ancestor strain. Three proteins encoded on each of the two plasmids were identified as putative lipoproteins, making a total of 151 candidates. The program LipoP scored 138 of the 151 candidates as lipoproteins (Table S1). Forty-one proteins could confidently be assigned a name and function, with most of the rest identified only as putative lipoproteins or ABC transporters.

The construction and complementation of lgt-deficient B. anthracis

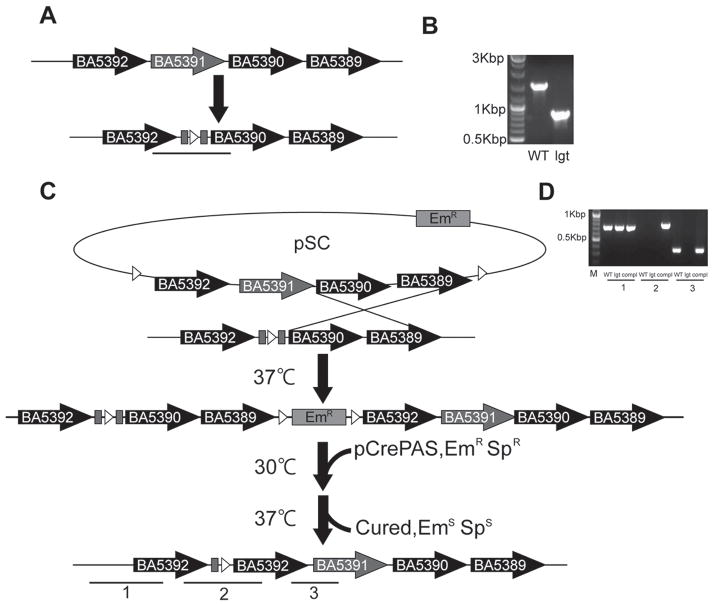

To determine the role of lipoproteins in B. anthracis, we constructed an lgt-deficient mutant. The lgt gene (BA5391 in the Ames strain) was disrupted without polar effects using the Cre-loxP system (Pomerantsev et al., 2006) as shown in Fig. 1A. We confirmed by PCR and sequencing that the lgt gene was deleted (Fig. 1B). We complemented the lgt gene in two ways. The first (“in situ”) method placed an intact gene back into the chromosome. This was accomplished with the single crossover plasmid pSC, into which the DNA region encompassing BA5389, BA5390, BA5391, and BA5392 was cloned at the multi-cloning site between the loxP sites, allowing the insertion of lgt (and neighboring genes) into the chromosome (Fig. 1C). Because the region containing BA5389 to BA5392 was reported to be operonic (Passalacqua et al., 2009), we inserted the lgt gene along with the putative co-operonic genes to avoid any disruption of transcription of the adjacent genes. After the single-crossover, Cre recombinase treatment was performed to remove the erythromycin resistance gene along with the pSC backbone and duplicated genes. Although we anticipated that a single-crossover would spontaneously remove the second copy of BA5392, it was still duplicated after several passages as was shown by PCR and sequencing (Fig. 1C and D). To exclude the possibility that the duplicated BA5392 affected the phenotype in these in situ complemented strains, we also complemented the lgt mutation with the plasmid pSW4-lgt in which lgt transcription is driven by the pagA promoter of B. anthracis. For each phenotype examined below, the in situ complemented strain displayed properties like those of the original wild-type strain.

Figure 1.

Deletion of the lgt gene and in situ complementation. (A) lgt was removed by Cre-loxP system. Underlined region was amplified by PCR to confirm deletion as shown in (B). (B) Ethidium bromide stained agarose gel showing PCR analysis of lgt depletion. Primers were designed to amplify the internal portion between BA5392 and BA5390. W: wild-type B. anthracis, lgt: lgt mutant. (C) For in site complementation, the pSC plasmid containing BA5392-BA5389 was introduced into the lgt knockout mutant, which was then grown at the restrictive temperature. The single-crossover insertion event was selected by the EmR phenotype. Removal of the EmR along with the pSC backbone from the chromosome was achieved by Cre-mediated recombination following transformation with pCrePAS. Growth at 37°C eliminated the pSC and pCrePAS plasmids, resulting in the (re)insertion of BA5391 (lgt gene). Underlined regions were amplified by PCR to analyze the resulting strain as shown in (D). (D) Ethidium bromide stained agarose gel showing PCR analysis of the complementation of lgt gene (BA5391) and the duplication of BA5392. W: wild-type B. anthracis, lgt: lgt mutant, compl: in situ complemented mutant.

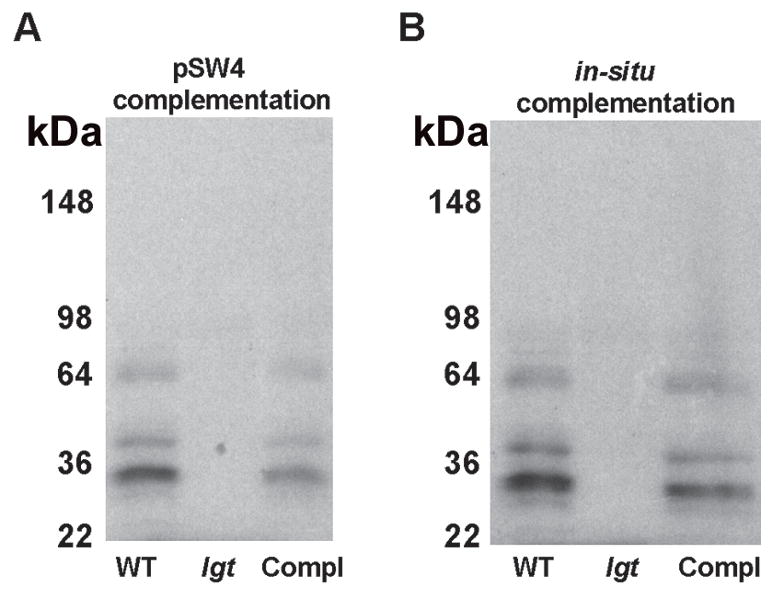

Lgt is required for lipid modification of prelipoproteins

To determine whether lgt performs the expected protein lipidation in B. anthracis, we carried out metabolic labeling experiments with [14C]-palmitic acid. Autoradiography of lipoprotein extracts separated by SDS-PAGE revealed several[14C]-labeled protein bands in the samples of the wild-type strain and the lgt mutant complemented with either the pSW4-lgt plasmid or by in situ gene replacement (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, no labeled proteins were detected in the lgt mutant (Fig. 2A and B). The strains having the mutation complemented in either of the two ways showed the same [14C]-labeled proteins as the wild-type strain, suggesting that the duplicated BA5392 gene in the in situ complemented mutant did not affect lipoprotein processing. These results demonstrated that lgt is required for the lipid modification of prolipoproteins in B. anthracis.

Figure 2.

Lack of lipidation in lgt mutant. Cells were cultivated in BHI medium with shaking for 4 h at 37°C. Lipoproteins were labeled with [14C]-palmitic acid and detected by autoradiography. (A) Wild-type strain with empty vector pSW4, lgt mutant with empty vector pSW4, and the complemented mutant with pSW4-lgt. (B) Wild-type strain, lgt mutant, and the in situ complemented mutant.

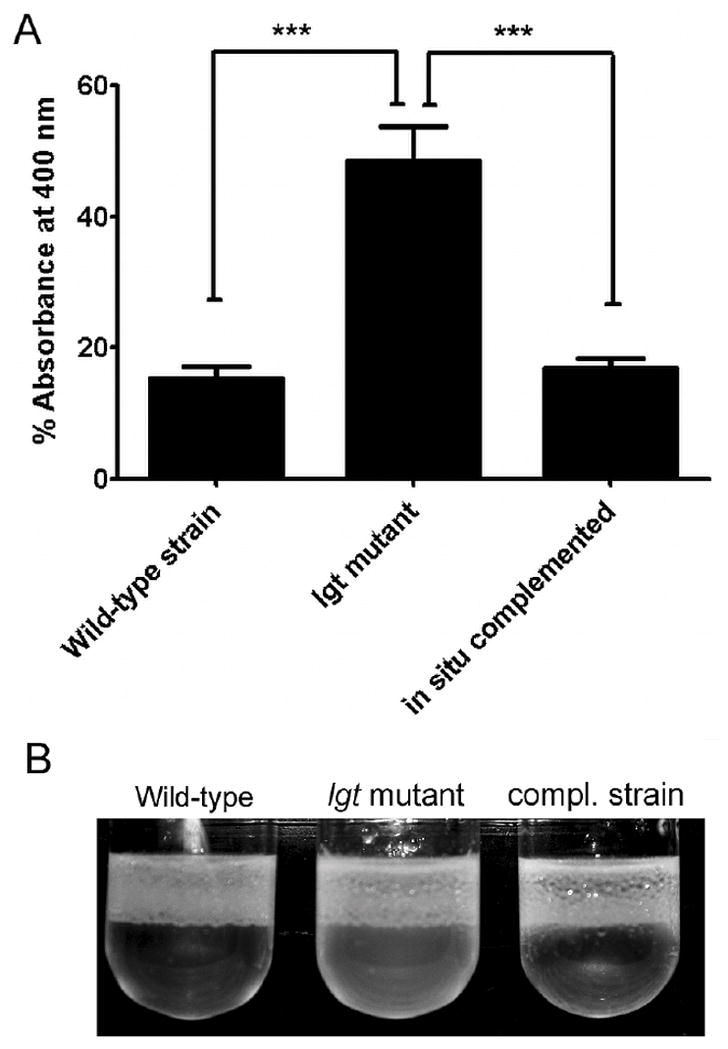

Deletion of lgt alters bacterial surface hydrophobicity

Bacterial surfaces are composed of hydrophobic and hydrophilic components, and many of them are proteins (Doyle, 2000). We considered whether the loss of surface-associated lipoproteins in the lgt mutant would alter bacterial surface hydrophobicity. Thus, to determine surface hydrophobicity for the wild-type, lgt mutant, and in situ complemented strains, we employed the Microbial Adhesion to Hydrocarbons (MATH) test. This test is based on the adhesion of bacteria to hexadecane in a buffer with high ionic strength that minimizes electrostatic effects (Rosenberg, 1981). As shown in Fig. 3, wild-type and in situ complemented B. anthracis exhibited higher surface hydrophobicity and readily adhered to hexadecane, evidenced by the lower optical density of the (lower) aqueous phase. In contrast, the lgt mutant strain was preferentially located in the aqueous phase. When the assay was performed with spores instead of vegetative bacteria, no differences in surface hydrophobicity was found (data not shown), indicating that the hydrophobicity of the spore surface was not altered. Taken together, these results show that the surface of vegetative bacteria of the lgt mutant is more hydrophilic than that of the wild-type or in situ complemented strains.

Figure 3.

Lipoproteins of B. anthracis influence bacterial surface hydrophobicity. Bacteria were cultured in BHI medium to an A600 of 4.0 and the washed bacterial suspensions were tested for adherence to hexadecane, which results in reduced optical density in the lower aqueous phase. Significant differences (p < 0.0001) between the lgt mutant, wild-type strain, and in situ complemented strain were determined by ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison post-test and are indicated by asterisks.

Deletion of lgt impairs germination

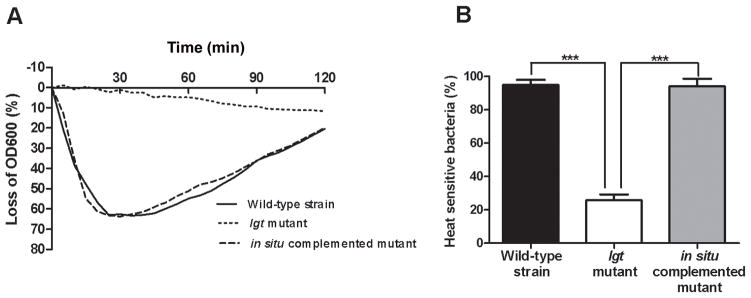

It was previously reported that inactivation of lgt impairs germination in B. subtilis (Igarashi et al., 2004). To test whether the same is true for B. anthracis, we assessed germination by measuring optical density at 600 nm and the loss of heat resistance. The lgt mutant showed significantly decreased germination efficiency in both assays (Fig. 4A and B), when compared to the fully germination-proficient in situ complemented mutant and wild-type strains. These data show that lipoproteins are needed for efficient spore germination in B. anthracis. Once germination occurred, both the lgt mutant and the complemented strain grew as well as the wild-type strain in BHI medium and modified G medium (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Lgt deficiency attenuates germination. (A) Germination of wild-type strain, lgt mutant, and in situ complemented mutant as monitored by the decrease in A600 of spore suspensions during incubation in BHI medium. Results are mean values of three independent experiments. Standard deviations are < 10% of the mean. The A600 curve of lgt mutant spores differed with statistical significance from the curves of the wild-type and in situ complemented strain spores. (B) Spores of wild-type strain, lgt mutant, and complemented mutant were incubated at in (A) at 37°C for 30 min. At 30 min, samples were heat-treated at 65°C for 30 min. Before and after heat treatment, samples were plated on BHI agar. Plates were incubated overnight and colonies were counted. The fraction of total CFU that were heat sensitive (i.e., germinated) was calculated and are plotted as the mean values ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Significant differences using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (p < 0.001) are indicated by three asterisks (***).

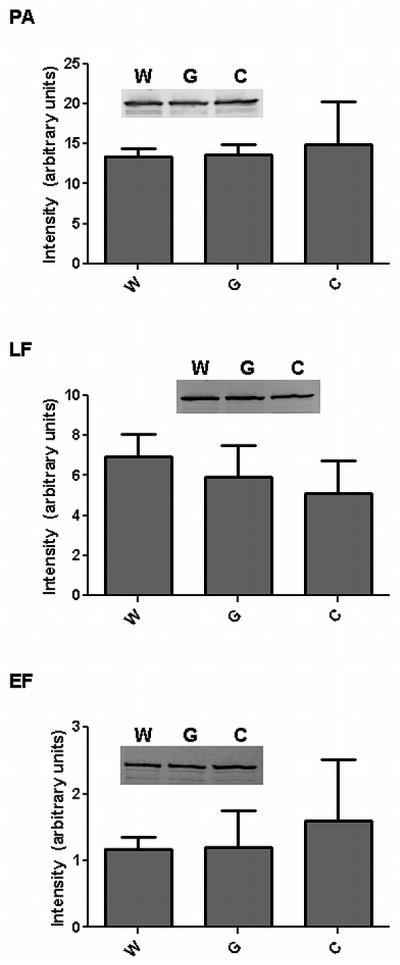

Anthrax toxin secretion is not prevented in the lgt mutant

The anthrax toxins play a crucial role in virulence toward animal hosts (Moayeri and Leppla, 2011). Because lgt mutants of B. subtilis were reported to be impaired in protein secretion due to decreased levels of the PrsA lipoprotein chaperone/foldase (Leskela et al., 1999; Kontinen and Sarvas, 1993), we considered the possibility that the lack of lgt in B. anthracis would prevent anthrax toxin secretion. We found that PA, LF, and EF were secreted from the wild-type, lgt−, and in situ complemented strains grown in BHI medium in air (data not shown) or in NBY medium supplemented with 0.9% Na2HCO3 in 9% CO2 (Fig. 5). (NBY medium was used because it appears to mimic the induction of toxin secretion by Na2HCO3/CO2 that occurs in a host which is infected with B. anthracis (Bartkus and Leppla, 1989; Chitlaru et al., 2006).) Quantitation of the band intensities showed no significant differences in the amounts of PA, EF, and LF in supernatants derived from the lgt mutant compared to the parental and complemented strains (Fig. 5). Thus, lgt deficiency appears not to effect anthrax toxin secretion or stability in B. anthracis in vitro.

Figure 5.

Anthrax toxin protein secretion from wild-type strain, lgt mutant, and in situ complemented mutant. Wild-type strain (W), lgt mutant (G), and in situ complemented mutants (C) were cultivated in NBY medium in air, or NBY supplemented with 0.9% sodium bicarbonate and 9% CO2 until A600 reached 2.0. Supernatants were separated by SDS-PAGE on 4–20% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and blotted with antibody to protective antigen (PA), lethal factor (LF), or edema factor (EF). Intensities of bands were measured with the Odyssey software. Results shown in graph represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments, and statistical analyses using one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s post-test for pairwise comparisons revealed no significant differences.

B. anthracis lacking lgt is a less potent activator of the macrophage inflammatory response

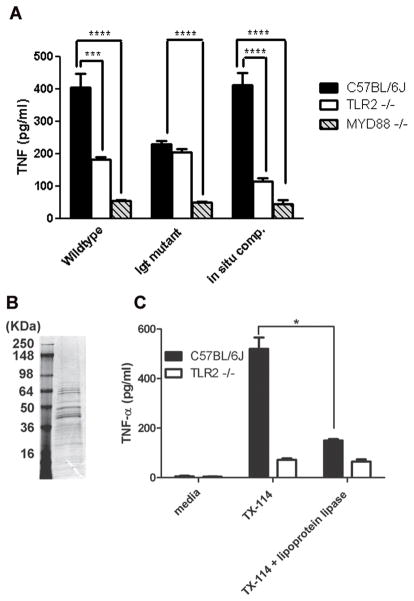

The lack of lgt in several Gram-positive pathogens was reported to attenuate host immune responses (Bubeck Wardenburg et al., 2006; Henneke et al., 2008). To determine whether lgt deficiency in B. anthracis affects immune responses, we measured TNF-α production in macrophages exposed to heat-killed bacteria of the wild-type, lgt mutant, and in situ complemented strains. We compared the cytokine responses of macrophages from wild-type C57BL/6J, TLR2, and MyD88-deficient mice (Fig. 6A). The Lgt-deficient bacteria caused significantly less TNF-α induction in the macrophages from C57BL/6J strains than did wild-type or complemented bacteria. A significant portion of the TNF-α response induced by wild-type and in situ complemented bacteria was mediated by TLR2. Other signaling pathways also contributed to the TNF-α response, as the lower cytokine response induced by the lgt mutant was not TLR2 dependent (Fig. 6A). As expected, none of the bacterial strains induced a cytokine response in macrophages from MyD88-deficient mice (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Induction of TNF-α secretion from macrophages by heat-killed B. anthracis and lipoprotein extracts. (A) Bone marrow-derived macrophages from the three types of mice indicated were exposed to heat-killed wild-type strain, lgt mutant, or complemented mutant at 100 μg ml−1. Macrophages were incubated for 18 h and supernatants were analyzed for TNF-α by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are plotted as the mean values ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Significant differences where p < 0.001 are indicated by three asterisks (***) and where p < 0.0001, indicated by four asterisks (****). (B) Coomassie blue staining of proteins in TX-114 fraction of B. anthracis (second lane). First lane contains molecular weight markers. (C) C57BL/6J bone marrow-derived macrophages from the two types of mice indicated were incubated with medium, TX-114 fraction, or lipoprotein lipase digested TX114 fraction for 18 h and supernatants were analyzed for TNF-α by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are plotted as the mean values ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Significant difference (p < 0.05) between lipoprotein lipase treatment and no treatment is indicated by an asterisk (*). All statistical tests used the unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Next, we asked whether lipoproteins of B. anthracis induce a TNF-α response through TLR2-mediated immune activation, as occurs with lipoproteins of other Gram-positive bacteria such as S. aureus and S. pneumoniae. We isolated lipoprotein-enriched fractions from the wild-type strain using Triton X-114 (TX-114) detergent extraction and partition procedures, as described in Experimental Procedures. Coomassie blue-stained gels showed several bands in the TX-114 fraction (Fig. 6B). The lipoprotein samples strongly activated TNF-α production from C57BL/6J macrophages, but had little effect on macrophages from TLR2-deficient mice. To address the concern that the TX-114 fraction may contain other bacterial components such as DNA and peptidoglycan that may activate macrophages, the TX-114 fraction was treated with lipoprotein lipase to inactivate the lipoproteins. Lipoprotein lipase was reported to eliminate the ability of lipoproteins samples to activate via TLR2 (Shimizu et al., 2005). This treatment significantly reduced the TNF-α response of the wild-type macrophages but did not affect the response of the TLR2-deficient macrophages (Fig. 6C). We confirmed that the decrease in cytokine production was not due to macrophage cell death by measuring viability (data not shown). These results indicate that lipoproteins of B. anthracis play a role in inducing inflammatory cytokines, acting at least in part through TLR2.

Lipoprotein biogenesis is required for efficient germination and virulence in vivo

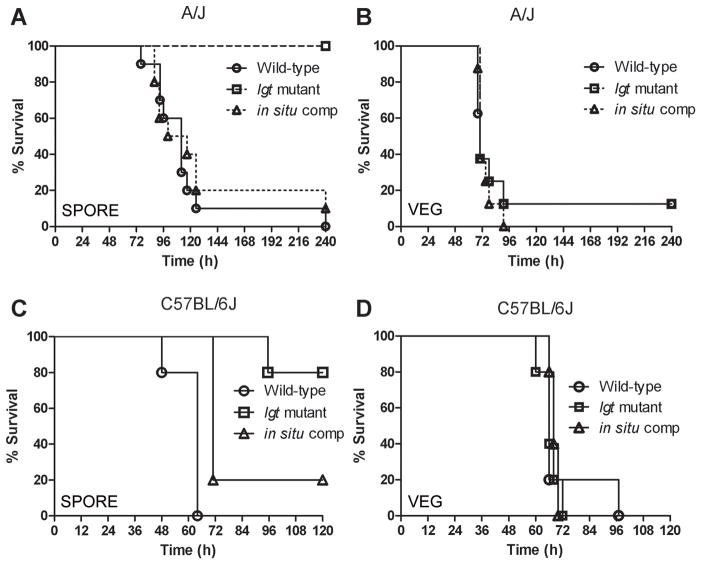

To investigate the contribution of lipoproteins to B. anthracis virulence, we challenged two strains of mice. Complement-deficient A/J mice are highly susceptible to non-encapsulated toxigenic B. anthracis (Loving et al., 2007), whereas complement-sufficient C57BL/6J mice require much higher doses of bacteria or spores for infection (Moayeri et al., 2010). Mice were infected with wild-type, lgt−, and in situ complemented strain spores or vegetative cells at 1 × LD100 doses for the particular mouse strain. Both A/J and C57BL/6J mice infected with the lgt mutant spores had significantly decreased mortality compared to mice infected with the wild-type strain (Fig. 7A and C). In contrast, no differences between strains were seen when vegetative bacteria were used (Fig. 7B and D). Complementation with the lgt gene restored virulence (Fig. 7A–7D). These results suggested that the reduced virulence of the lgt mutant strains results from their impaired germination.

Figure 7.

Survival curves of mice challenged subcutaneously (SC) with spores or vegetative bacteria. A/J mice (A, B) or C57BL/6J (C, D) mice were injected SC with 2 × 103 spores (A, n=10), 20 vegetative cells (B, n=8), 2 × 107 spores (C, n=5) or 1 × 105 vegetative cells (D, n=5). The survival curves following lgt mutant spore challenge differed with statistical significance (by the logrank test) from curves of the wild-type and complemented strains for both A/J challenges (p < 0.0001), as well as C57BL/6J challenges (p< 0.05), while no significant differences were found in vegetative challenges.

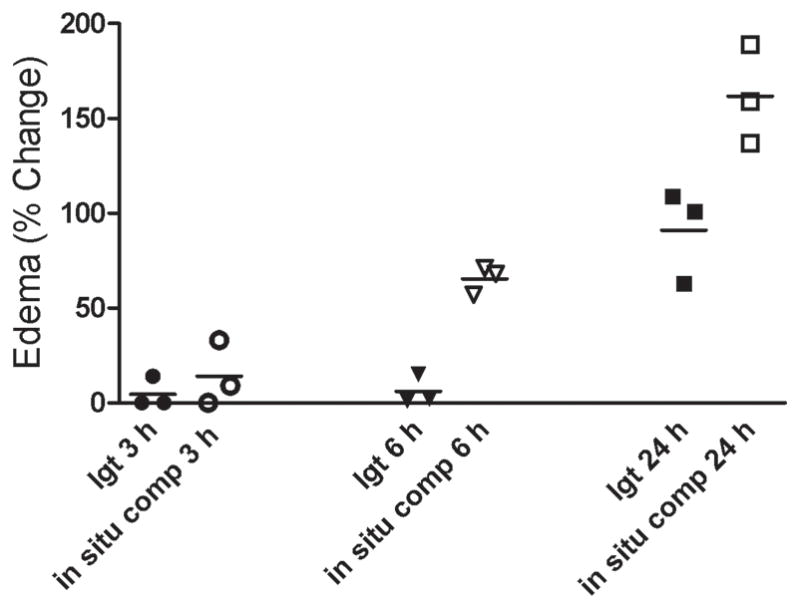

To address in another animal model the question of whether the lgt mutant is impaired for germination in vivo, we measured edema at early times after spore injection, which we previously showed was representative of the outgrowth of vegetative bacteria (Moayeri et al., 2010). A/J mice were infected with equal numbers of lgt mutant or in situ complemented spores in the foreleg in a small volume (50 μl). ET-mediated local edema was quantitated by measuring anterior to posterior and sagittal dorsal/ventral dimensions at various times post-infection. Even at the earliest (3-h) measurement, the lgt mutant induced significantly less edema than the complemented strain (Fig. 8). This difference persisted through the 6- and 24-h measurements (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Edema in mouse forelegs following infection with lgt mutant or in situ complemented strain. Groups of three A/J mice were injected with lgt mutant or complemented mutant (5 × 107 spores, 50 μl, SC). Percent increases in foot edema dorsal/ventral measurements relative to pre-infection measurements are shown at 3, 6, and 24 h following infection. Each symbol represents measurements of an individual mouse. P-values comparing lgt mutant to in situ complemented strain at 6 and 24 h are < 0.02 by unpaired two-tailed t-test.

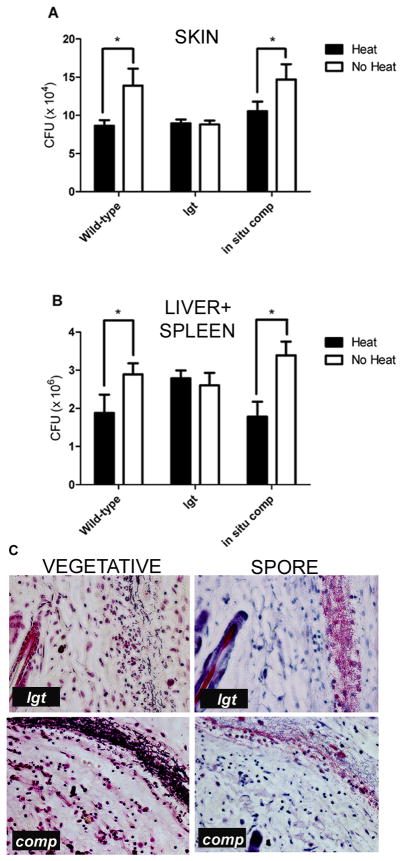

For a more direct quantification of the lgt mutant’s germination ability, we assessed bacterial growth and survival (as colony forming units (CFU)) in mouse skin and internal organs. Skin was homogenized in a germination-prohibitive buffer 6 h after subcutaneous (SC) injection of spores. Plating of the homogenates before and after heat treatment (to kill vegetative bacteria) allowed enumeration of ungerminated spores and vegetative bacteria. In parallel, intravenous (IV) injection of spores provided an alternative in vivo environment for germination and rapid delivery to organ sites. Spleens and livers from mice were pooled and processed together to quantify vegetative bacteria vs. total bacteria (ungerminated spores + vegetative bacteria). Results from these studies are presented in Fig. 9A (skin) and Fig. 9B (liver + spleen). While the wild-type and complemented strain bacteria were present as vegetative bacteria and spores in both skin and the internal organs, the lgt mutant appeared to be present only as spores, reflecting little to no germination. Interestingly, the total number of bacteria isolated from the skin of mice injected with the lgt mutant was consistently lower than from those injected with the wild-type and the complemented mutant by 6 h (Fig. 9A). This could be due in part to a more efficient ingestion and killing of the lgt- vegetative bacteria, present in smaller numbers due to slower spore germination, and their subsequent inability to produce sufficient anthrax toxins to inactivate immune cells. This explanation is consistent with our recent demonstration that germination and the resultant production of anthrax toxin is required for effective evasion of myeloid cell-mediated killing of B. anthracis (Liu et al., 2010).

Figure 9.

Spore germination following subcutaneous (SC) and intravenous (IV) infection. (A) A/J mice (n=3/group) were injected SC in the foreleg with 5 × 107 spores in 50 μl, and (B) C57BL/6J mice (n=2/group) were injected IV with 1 × 106 spores in 200 μl. Skin and underlying tissues were obtained at 6 h from the A/J mice and spleen and liver were obtained at 90 min from the C57BL/6J mice. Tissues were processed as described in Experimental Procedures and total CFUs determined before and after heat treatment. Values plotted are the number of spores (solid bars, “Heat”) and the sum of spores + germinated bacteria (open bars, “No Heat”). Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) by 2-way ANOVA test. (C) Representative histology images showing staining of vegetative bacteria (left panels) and spores (right panels) in foreleg skin sections harvested 6 h post-infection from A/J mice injected SC with 1 × 108 spores. Upper panels show lgt mutant and lower panels show complemented strain. The upper and lower pairs of images were prepared from proximal but independent sections.

Alternatively, the lower total number of bacteria may be due to inefficient germination of the lgt mutant spores retrieved from the animals. However it is clear that almost all the bacteria retrieved from mice injected with the mutant were spores, and analyses of skin sections from mice injected with spores also showed a higher number of ungerminated lgt mutant spores compared to the complemented strain spores (Fig. 9C). Altogether, these data verify that lgt deficiency leads to an attenuation of virulence primarily through impaired in vivo germination, with a possible consequence of higher efficiency of killing by the innate immune response.

Discussion

B. anthracis, like other Gram-positive bacteria, is predicted from genomic sequence analysis to have a large number of cell surface-associated lipoproteins (Hutchings et al., 2009), but these have not been studied as a group. In fact, no putative B. anthracis lipoproteins appear to have experimentally been localized to the cell or spore membranes through a lipid anchor. Several proteins that are expected to be anchored in the cell wall by lipid modifications are implicated as playing important roles in normal physiology and/or pathogenesis. Examples include the manganese ABC transporter MntA (BA3189) (Gat et al., 2005), the polyglutamic capsule anchoring protein CapD (pXO2 BA0063) (Richter et al., 2009), the InhA protease (BA0672) (Chung et al., 2009), and the three PrsA chaperone/foldases (BA1041, 1169, and 2336) (Kontinen and Sarvas, 1993). (See also Table S1 and comments below.)

To further understand the role of lipoproteins in B. anthracis, we began by screening databases using bioinformatic tools. We used ScanProsite with the improved G+Lppv2 motif, followed by LipoP. G+LPPv2 was reported to have 100% sensitivity to 90 experimentally verified Gram-positive bacterial lipoproteins whereas LipoP has a higher specificity and ability to discriminate against false positives than G+LPPv2 (Rahman et al., 2010). This analysis identified 138 proteins as putative lipoproteins (Table S1), indicating that lipoproteins represent about 2.5% of the proteome. This percentage is similar to that in the proteomes of other Gram-positive bacteria (Sutcliffe and Harrington, 2002; Babu et al., 2006). The largest group of the candidate lipoproteins in B. anthracis consists of substrate-binding proteins of ABC transporter uptake systems. The next largest group comprises proteins involved in sensing germinants and triggering germination. This analysis helped to suggest possible phenotypic changes that might be observed in bacteria deficient in lipoprotein biosynthesis.

We disrupted the lgt gene using the previously reported Cre-loxP system (Pomerantsev et al., 2009). To verify that the phenotypes described here are due to the lgt mutation, it was essential to complement the mutation. The in situ complementation method used here took advantage of the residual loxP site generated during gene deletion (Fig. 1A). This method also allowed complementation to be done without having to maintain a plasmid under selective pressure. The strain complemented in this way retained two copies of the gene adjacent to lgt, BA5392 (annotated as a bifunctional histidine-containing protein kinase/phosphatase), but this had no detectable effect on any of the phenotypes of B. anthracis studied here. The strain complemented with a plasmid expressing lgt also behaved in every regard like the wild-type strain.

While lgt is essential for the survival of Gram-negative bacteria, it is dispensable in Gram-positive bacteria, as shown for S. aureus and S. pneumoniae (Stoll et al., 2005; Petit et al., 2001). In B. anthracis, the lgt mutant grows as well as the wild-type strain in either nutrient-rich medium (BHI medium) or poor-nutrient medium (e.g., modified G medium) (data not shown). This is somewhat surprising given the large number of ABC transporters that are lipoproteins. ABC transporters mediate the uptake of many nutrients, such as peptides, amino acids, metals, and vitamins (Davidson et al., 2008), and the uptake of these materials could promote growth in nutrient-poor media. However, B. anthracis can apparently satisfy its essential requirements through de novo synthesis, or by using other uptake mechanisms that do not involve lipoproteins.

Although B. subtilis lacking lgt shows impairment of protein secretion (Kontinen and Sarvas, 1993), there were no significant changes in anthrax toxin secretion in the B. anthracis lgt mutant under the conditions used here. A secretion defect might have been expected since the three similar putative B. anthracis PrsA secretion chaperone/foldases are predicted to be involved in protein secretion and all are lipoproteins (Table S1). In fact, these three B. anthracis genes supported modest increases in production of recombinant PA when expressed in B. subtilis (Williams et al., 2003).

The largest phenotypic changes we found in the lgt mutant involved spore germination. Spore germination plays a crucial role in anthrax disease initiation (Carr et al., 2009) and the ability to germinate efficiently may be viewed as a key virulence factor. In our infection model we found that the lgt mutant has reduced virulence, likely caused by its impaired germination. Genomic and genetic analyses have identified five distinct germination operons in B. anthracis, GerH, GerK, GerL, GerS, and GerX (Fisher and Hanna, 2005; Carr et al., 2009). Each operon contains three genes, denoted A, B, and C (e.g., gerHA, gerHB, gerHC, etc.), of which the C gene in each operon encodes a lipoprotein (Table S1). The three proteins encoded by each operon associate to form a receptor that recognizes the specific small molecule germinants such as amino acids and purine nucleosides that initiate germination. In addition, two less well-characterized genes that affect germination, gerD (Pelczar et al., 2007) and gerM (Rigden and Galperin, 2008), are also predicted to encode lipoproteins (Table S1). The GerD protein is believed to co-localize with the germinant receptor proteins and accelerate their signaling to downstream effectors. Mutation of the cysteine in the lipobox of GerD leads to spores lacking the protein and having a severe germination defect like that of a complete gerD deletion (Pelczar et al., 2007; Mongkolthanaruk et al., 2009). Both types of gerD mutations therefore accurately phenocopy the lgt mutation described here. Although we did not directly demonstrate that specific germinant proteins and pathways are impaired in the lgt mutant strain, the key roles that lipoproteins play in the germinant sensing pathways appear sufficient to account for the impairment of germination. It is interesting to note that the first identification of lgt in B. subtilis came from a search for germination mutants, and the gene was first designated gerF (Igarashi et al., 2004), prior to its biochemical role in lipoprotein biosynthesis being recognized.

While lipoproteins were found to be essential in a spore-initiated infection, they were dispensable when vegetative bacteria were inoculated into mice. This retention of virulence was surprising given that up to 150 proteins probably depend on a lipid anchor for correct localization and function, and that lgt is an essential gene in Gram-negative bacteria. A possible decrease in protein secretion (affecting proteinaceous virulence factors) might have been expected to decrease virulence (Leskela et al., 1999), but appears to be of little significance in the infection model used here. Furthermore, the apparent ability to dispense with a large number of ABC transporters during growth in animals suggests that this is a rich environment where nutrient acquisition is not limiting.

It should be noted, in considering explanations for the restricted impact of the lgt mutation, that the precise effect of Lgt deficiency on the anchoring of specific lipoproteins may vary. The prolipoproteins will be secreted onto the surface of the mutant bacteria, or into the matrix of the peptidoglycan cell wall, and will initially be anchored there by their signal peptides. In the absence of the Lgt enzyme, the prolipoproteins may remain cell surface associated and retain some function. For certain lipoproteins, this residual function may approach that of the normal, fully-lipidated protein that would be produced in a wild-type bacterium (Hutchings et al., 2009). This may reconcile our finding that the lgt mutant retains virulence (Fig. 7) with the report that the deletion of the manganese ABC transporter and lipoprotein MntA (BA3189) severely impairs virulence (Gat et al., 2005). Some insights into this question could come from a comparison of the “surfaceomes” (Desvaux et al., 2006) of the lgt− and wild-type strains, as might be achieved by mass spectrometry of protease-released peptides.

The creation of the lgt mutant strain also allowed us to examine the role of lipoproteins in host innate immune responses. It was reported that heat-killed B. anthracis are recognized by TLR2 (Hughes et al., 2005), but it was not determined which bacterial components induce TLR2 activation. Here we showed that lipoproteins of B. anthracis induce TNF-α production in macrophages primarily through the TLR2 pathway. We considered that TLR2 may play a protective role against B. anthracis infection because of its recognition of B. anthracis. However we found no difference in susceptibility of TLR2-deficient and wild type mice to subcutaneous B. anthracis infection (data not shown). This finding was similar previous findings in an inhalational anthrax mouse model (Hughes et al., 2005). Thus, while TLR2 contributes to cytokine responses induced by B. anthracis, a protective or detrimental role for the TLR2-dependent innate immune response is not observed in mice.

In conclusion, lipoproteins synthesized and anchored to membranes through the action of the Lgt enzyme are essential for full virulence of B. anthracis in spore-induced infections, apparently due to the role of lipoproteins in sensing germinants present in host tissues. Lipoproteins in B. anthracis are recognized by TLR2; however, TLR2 activation does not play a crucial role in a mouse infection model. These results expand our understanding the pathogenesis of B. anthracis and could aid in developing new therapeutic approaches.

Experimental procedures

Bioinformatic analyses

We used two tools, ScanProsite with G+Lppv2 pattern and LipoP (Rahman 2008). First, protein sequence databases (UniprotKB; Taxonomy identifier 1392 B. anthracis) were screened using ScanProsite and the G+LPPv2 pattern ([MV]-X(0,13)-[RK]-[DERK](6,20)-[LIVMFESTAGPC]-[LVIAMFTG]-[IVMSTAGCP]-[AGS]-C). Second, proteins identified by G+LPPv2 were validated by the Hidden-Markov-Model-based tool LipoP that screens for type II signal peptidase sequences. LipoP can eliminate potential false-positives. Sequences selected by LipoP were considered as putative lipoproteins. Finally, the genes of the Ames strain which we used in this study were selected, because both Ames and Sterne strain data exist in the protein sequence database. For the screening of the pXO1 and pXO2 plasmids, B. anthracis Ames Ancestor strain protein sequence databases were used, because B. anthracis Ames strain databases does not include plasmid sequences.

Bacterial strains, growth condition and spore preparation

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2. E. coli was grown at 37°C with 225 rpm shaking in Luria Burtani broth. B. anthracis was grown at 37°C with shaking at 225 rpm in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth (Difco). SOC medium (Quality Biologicals) was used for outgrowth of transformation mixtures prior to plating on selective medium to isolate transformants. When required, media were supplemented with antibiotics as follows: 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin, 20 μg ml−1 erythromycin, 20 μg ml−1 kanamycin, and 150 μg ml−1 spectinomycin.

Spores for germination assay and murine challenges were prepared by a previously reported method with some modifications (Hu et al., 2006). Briefly, bacteria were grown at 30°C for 1 day and at room temperature for 2 days on Schaeffer’s sporulation agar, and spores were collected with ice-cold distilled water. Residual vegetative cells were killed by heat at 65°C for 30 min. To remove vegetative cell debris, the spores were washed multiple times with ice-cold distilled water. Spore purity was assessed under a phase contrast microscope and was greater than 99%. Spore quantification was performed using a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber. Vegetative cells for murine challenge were grown at 37°C overnight in BHI broth, diluted 100-fold in fresh broth, and incubated with shaking at 37°C until A600 of 0.4–0.6 (early log phase). Cells were washed and diluted with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Cell quantification was performed using a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber and confirmed by colony forming count on BHI agar.

DNA isolation and manipulation

Preparation of plasmid DNA from E. coli, transformation of E.coli, and recombinant DNA techniques were carried out by standard procedures (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). Recombinant plasmid construction was carried out in E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen). Chromosomal DNA from B. anthracis was isolated with the Wizard genomic purification kit (Promega) in accordance with the protocol for isolation of genomic DNA from Gram-positive bacteria. B. anthracis was electroporated with unmethylated plasmid DNA isolated from E.coli SCS110 (dam− dcm−, Stratagene). Electroporation-competent B. anthracis cells were prepared and transformed as previously described (Park and Leppla, 2000).

Deletion of the lgt gene

The primers used in this study are listed in Table S2. The Cre-loxP-generated deletion method was previously described (Pomerantsev et al., 2009). Briefly, to delete the lgt gene, we amplified an upstream fragment of the lgt gene using the forward primer LLF containing an EcoRI site and the reverse primer LLR containing a SpeI site. The downstream fragment was amplified with the forward primer LRF containing an EcoRI site and the reverse primer LRR containing a SpeI site. These fragments were separately cloned into the temperature-sensitive pSC plasmid between loxP sites. pSC containing the upstream fragment was transformed into B. anthracis Ames 35, which was then grown at the restrictive temperature. Cre-mediated recombination was achieved by the transforming the strain with pCrePAS. The same process was repeated for the downstream fragment. After Cre-loxP-generated deletion, 774 bp of the 813-bp lgt gene were removed. Deletion of lgt was confirmed by PCR using forward primer BA5391genoF and reverse primer BA5391genoR, and also by sequence analysis.

Complementation of the lgt gene

For plasmid-based complementation of the lgt mutant, the lgt gene was cloned into plasmid pSW4 behind the pagA promoter. The lgt gene was amplified from B. anthracis Ames 35 strain genomic DNA by PCR using the forward primers BA5391F containing an NdeI site and the reverse primer BA5391R containing a BamHI site. Plasmid pSW4-lgt was identified by restriction analysis and sequencing and was transformed into the lgt mutant by electroporation, with selection for kanamycin resistance. For in situ complementation of the lgt gene in the genome of the lgt-deficient mutant, a 3413-bp fragment including BA5389 to BA5392 was amplified by PCR using the forward primer BA5389–5392F containing a PstI site and the reverse primer BA5389–5392R containing a BamHI site. The PCR product was cut with PstI and BamHI (New England Biolabs) and the fragment ligated into pSC with T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen). Erythromycin-resistant colonies obtained by transformation with this pSC plasmid and grown at 37°C were presumed to have undergone a single crossover. The erythromycin resistance gene along with the pSC backbone and duplicated genes between the loxP sites were removed by Cre-mediated recombination after transforming the strain with pCrePAS at 30°C. Both pCrePAS and pSC were eliminated by growth at 37°C. Complementation of genes was confirmed by PCR using the forward primer BA5392-BA5392F and the reverse primer BA5392-BA5392R for the junction between BA5392 and BA5392, the forward primer BA5393-BA5392F and the reverse primer BA5392-BA5392R for the junction between BA5393 and BA5392, and the forward primer BA5392-BA5391F and the reverse primer BA5392-BA5391R for the junction between BA5392 and BA5391.

Metabolic labeling of lipoproteins with [14C] palmitic acid

[14C] palmitic acid (MP Biomedicals) was dried under a nitrogen stream and redissolved in 0.2% Tween 80. To an exponential phase culture in BHI medium, 4 μCi [14C] palmitic acid ml−1 was added. The bacteria were cultivated with shaking for 4 h at 37°C. The cells were disrupted by 0.1 mm diameter glass beads (Next Advance, Averill Park, NY). Lysed suspensions were centrifuged and wereseparated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresison a 4 to 20% Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen) under denaturing conditions. Gels were dried and autoradiographed for 2 weeks.

Measurement of cell surface hydrophobicity

Bacteria were grown in BHI broth at 37°C and 225 rpm to late logarithmic growth phase (A600 nm of 4.0). Bacteria were centrifuged and washed twice in PUM buffer (17 g l−1 K2HPO4, 7.3 g l−1 KH2PO4, 1.8 g l−1 urea, 0.2 g l−1 MgSO4×7H2O, pH 7.1) and resuspended in PUM to 2× the original volume. Bacteria (2 ml) were transferred to glass tubes and overlaid with 1 ml of hexadecane (Sigma-Aldrich), incubated for 10 min at 30°C, and vortexed rigorously for 2 min. The aqueous and hydrocarbon phases were allowed to separate at room temperature for 15 min before the aqueous (lower) phase was carefully removed, and its optical density determined at 400 nm.

Toxin production

B. anthracis was cultured in NBY medium with or without 0.9% Na2HCO3 in either air or air supplemented with 9% CO2 (Chitlaru et al., 2007; Sastalla et al., 2009). Cultures were grown at 37°Cwith shaking at 225 rpm until A600 of 2.0 (mid-log phase) and then centrifuged for 10 min at 15000 g and filtered using 0.22 μm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) filter units (Millipore). The supernatants were denatured by the addition of 1/5 volume of 6 × sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (10% SDS, 500 mM Tris, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 0.6 M dithiothreitol, 30% glycerol, pH 7.5). The samples were boiled for 5 min and equal volumes were resolved using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (4 to 20% Tris-glycine gel, Invitrogen) and blotted to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen). The membranes were probed for the presence of protective antigen (PA), edema factor (EF), and lethal factor (LF) using anti-PA serum (#5308 at a dilution of 1:5000), anti-EF serum (#5900 at a dilution of 1:1000), and anti-LF goat polyclonal antibodies (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA, at 0.5 μg ml−1), respectively. Primary antibodies were detected using IR-dye-conjugated secondary antibodies (Licor Biosciences, 1:5000) and signals were imaged and quantified with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Licor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

In vitro germination assay

Spores were activated by incubation at 70°C for 20 min in distilled water. Subsequently, spores were washed with distilled water and resuspended in BHI medium to an A600 of ≈0.3 (≈2.0 × 107 spores ml−1) and the germination processwas monitored by A600. The A600 of the samples were measured every5 min for 120 min. Spores were routinely observed for germination by phase contrast microscopy. To evaluate the loss of heat resistance, spores incubated in BHI medium for 30 min were heated at 65°C for 30 min to kill germinated cells. Samples taken before and after heat treatment were plated on BHI agar. One hundred percent sensitive to a heat treatment was considered 100% germinated.

Preparation of heat-killed bacteria for TNF-α assays

To generate heat-killed bacteria, vegetative cells were grown at 37°C overnight in BHI broth, diluted 100-fold in fresh broth, and incubated with shaking at 37°C until A600 was 0.65 (early-log phase). Thebacterial suspension was washed three times with PBS, resuspended in PBS, and A600 for different strains normalized to each other prior to heat inactivation (70°C for 70 min). After a final spin and removal of PBS, the bacterial cell pellet was lyophilized. Lyophilized heat-killed bacteria were weighed and resuspended in PBS prior to addition to bone-marrow-derived macrophages. To confirm that bacteria were killed, heat-killed bacteria were plated on BHI agar and incubated overnight at 37°C.

Extraction of lipoproteins

To extract a fraction containing lipoproteins, exponential phase B. anthracis cells at A600 of 1.0 were subjected to Triton X-114 (TX-114) phase partitioning (Thakran et al., 2008). Briefly, the cell pellets were resuspended in PBS supplemented with 350 mM NaCl, 2% v/v TX-114 (Sigma-Aldrich), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete mini, Roche Diagnostics) and incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Samples were centrifuged at 10000 g at 4°C for 30 min and the supernatant was incubated at 37°C for 10 min to induce detergent phase separation. The upper aqueous phase was discarded and replaced with a similar volume of PBS supplemented with 350 mM NaCl. The procedure of phase separation was repeated twice and the final detergent phase was retained.. To remove the detergent, the crude lipoprotein fraction was precipitated at −20°C overnight by addition of 2.5 volumes of methanol. After centrifugation at 10000 g and 4°C for 30 min, the pellet was washed with methanol, air-dried, and resuspended in PBS. Protein concentration of the suspension was measured with BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific Pierce). To digest lipoproteins, 10 μg ml−1 lipoprotein lipase from Pseudomonas sp. (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to crude lipoproteins and then incubated for 18 h at 37°C. Lipoprotein lipase was inactivated by heating at 72°C for 20 min.

TNF-α assays

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were isolated from C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), TLR2-deficient mice (knockouts on C57BL/6J background, kindly provided by Alan Sher, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) or MyD88-deficient mice (gift from Shizuko Akira, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan; received via Tod J. Merkel, Food and Drug Administration, Bethesda, MD). Cells were cultured in differentiation medium consisting of 30% L929 cell-conditioned medium in Dulbecco-modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin (all obtained from Invitrogen) as previously described (Newman et al., 2009). On day 7, cells were plated in 96-well plates (1 × 105 cells well−1). On day 8 cells were treated with 100 μg ml−1 heat-killed bacteria for 20 min and expression levels of TNF-α were measured with a TNF-α ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Mouse infection studies

A/J or C57BL/6J mice (8- to 12-weeks, female) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. In survival studies, mice were injected subcutaneously (SC, 200 μl) with spores or vegetative cells (see figure legends for doses), and observed for up to 10 days. For indirect assessment of germination by measurement of edema toxin activity, 5 × 107 spores in 50 μl PBS were injected SC into the foreleg of A/J mice and edema quantified as previously described (Moayeri et al., 2010). Direct measurements of in vivo germination were made by completely removing skin and underlying foreleg tissue 6 h after injection of A/J mice (5 × 107 spores, SC). Tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 7.5 ml of a germination inhibitory buffer (PBS + 150 μM D-alanine, 200 μM 6-thioguanosine, both from Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Dilution plating of homogenates to assess differential vegetative and spore-based colony forming units (CFUs) was performed both before and after heat treatment (70°C, 70 min). In separate experiments, C57BL/6J mice were injected with spores (1 × 106)by the intravenous (IV) route and spleen and liver from individual mice were harvested, pooled and processed for vegetative and spore-based CFU quantification as described above. For histology, A/J mouse forelegs were injected (1 × 108 spores, 50 μl, SC) and skin and underlying tissue sections were harvested 90 min and 6 h after infection, fixed overnight in 10% formalin followed by repeated 70% ethanol washes. Section preparation, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Brown and Hopps tissue Gram stain (for vegetative bacteria), and a modified carboxyl fuchsin stain/malachite green counterstain (for spores) were performed on adjacent serial sections by Histoserv, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD). For the spore stain, the Accustain Acid Fast Kit (Sigma) was used according to manufacturer’s protocol, with a 1-h staining period in heated (steaming) carbol fuchsin solution (0.85% pararosaniline dye, 2.5% phenol, 5% glycerol, 5% DMSO, in deionized water) prior to counterstaining with malachite green (1.5% malachite green oxalate, 10% acetic acid, 17% glycerol in deionized water) for 2 min at room temperature. All protocols using mice were approved by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism 5 (Graph Pad System, Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical tests used for each experiment are listed in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan Sher for kindly providing TLR2-deficient mice and Drs. Akira and Merkel for MYD88 knockout mice. We also thank Mini Varughese for editing the manuscript. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

References

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu MM, Priya ML, Selvan AT, Madera M, Gough J, Aravind L, Sankaran K. A database of bacterial lipoproteins (DOLOP) with functional assignments to predicted lipoproteins. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2761–2773. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.2761-2773.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkus JM, Leppla SH. Transcriptional regulation of the protective antigen gene of Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2295–2300. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2295-2300.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner M, Karst U, Gerstel B, Loessner M, Wehland J, Jansch L. Inactivation of Lgt allows systematic characterization of lipoproteins from Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:313–324. doi: 10.1128/JB.00976-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubeck Wardenburg J, Williams WA, Missiakas D. Host defenses against Staphylococcus aureus infection require recognition of bacterial lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13831–13836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603072103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr KA, Lybarger SR, Anderson EC, Janes BK, Hanna PC. The role of Bacillus anthracis germinant receptors in germination and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2009;75:365–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitlaru T, Gat O, Gozlan Y, Ariel N, Shafferman A. Differential proteomic analysis of the Bacillus anthracis secretome: distinct plasmid and chromosome CO2-dependent cross talk mechanisms modulate extracellular proteolytic activities. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3551–3571. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3551-3571.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitlaru T, Gat O, Grosfeld H, Inbar I, Gozlan Y, Shafferman A. Identification of in-vivo expressed Iimunogenic proteins by serological proteome analysis of Bacillus anthracis secretome. Infect Immun. 2007 doi: 10.1128/IAI.02029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MC, Jorgensen SC, Popova TG, Tonry JH, Bailey CL, Popov SG. Activation of plasminogen activator inhibitor implicates protease InhA in the acute-phase response to Bacillus anthracis infection. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:737–744. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.007427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartois V, Djavakhishvili T, Hoch JA. KapB is a lipoprotein required for KinB signal transduction and activation of the phosphorelay to sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:1097–1108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6542024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AL, Dassa E, Orelle C, Chen J. Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:317–64. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00031-07. table. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deka RK, Brautigam CA, Yang XF, Blevins JS, Machius M, Tomchick DR, Norgard MV. The PnrA (Tp0319; TmpC) lipoprotein represents a new family of bacterial purine nucleoside receptor encoded within an ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-like operon in Treponema pallidum. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8072–8081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvaux M, Dumas E, Chafsey I, Hebraud M. Protein cell surface display in Gram-positive bacteria: from single protein to macromolecular protein structure. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;256:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle RJ. Contribution of the hydrophobic effect to microbial infection. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:391–400. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher N, Hanna P. Characterization of Bacillus anthracis germinant receptors in vitro. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:8055–8062. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.23.8055-8062.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gat O, Mendelson I, Chitlaru T, Ariel N, Altboum Z, Levy H, et al. The solute-binding component of a putative Mn(II) ABC transporter (MntA) is a novel Bacillus anthracis virulence determinant. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:533–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Chang SY, Chang S, Giam CZ, Wu HC. Modification and processing of internalized signal sequences of prolipoprotein in Escherichia coli and in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:5753–5759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneke P, Dramsi S, Mancuso G, Chraibi K, Pellegrini E, Theilacker C, et al. Lipoproteins are critical TLR2 activating toxins in group B streptococcal sepsis. J Immunol. 2008;180:6149–6158. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Sa Q, Koehler TM, Aronson AI, Zhou D. Inactivation of Bacillus anthracis spores in murine primary macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1634–1642. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MA, Green CS, Lowchyj L, Lee GM, Grippe VK, Smith MF, Jr, et al. MyD88-dependent signaling contributes to protection following Bacillus anthracis spore challenge of mice: implications for Toll-Like receptor signaling. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7535–7540. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7535-7540.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings MI, Palmer T, Harrington DJ, Sutcliffe IC. Lipoprotein biogenesis in Gram-positive bacteria: knowing when to hold ‘em, knowing when to fold ‘em. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi T, Setlow B, Paidhungat M, Setlow P. Effects of a gerF (lgt) mutation on the germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2984–2991. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.2984-2991.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandavilli S, Homer KA, Yuste J, Basavanna S, Mitchell T, Brown JS. Maturation of Streptococcus pneumoniae lipoproteins by a type II signal peptidase is required for ABC transporter function and full virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:541–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontinen VP, Sarvas M. The PrsA lipoprotein is essential for protein secretion in Bacillus subtilis and sets a limit for high-level secretion. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:727–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs-Simon A, Titball RW, Michell SL. Lipoproteins of bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun. 2011;79:548–561. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00682-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppla SH. Bacillus anthracis toxins. In: Alouf JE, Popoff MR, editors. The Comprehensive Sourcebook of Bacterial Protein Toxins. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 323–347. [Google Scholar]

- Leskela S, Wahlstrom E, Kontinen VP, Sarvas M. Lipid modification of prelipoproteins is dispensable for growth but essential for efficient protein secretion in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of the Lgt gene. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1075–1085. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Miller-Randolph S, Crown D, Moayeri M, Sastalla I, Okugawa S, Leppla SH. Anthrax toxin targeting of myeloid cells through the CMG2 receptor Is essential for establishment of Bacillus anthracis infections in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loving CL, Kennett M, Lee GM, Grippe VK, Merkel TJ. A murine aerosol challenge model of anthrax. Infect Immun. 2007 doi: 10.1128/IAI.01875-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moayeri M, Crown D, Newman ZL, Okugawa S, Eckhaus M, Cataisson C, et al. Inflammasome sensor Nlrp1b-dependent resistance to anthrax Is mediated by caspase-1, IL-1 signaling and neutrophil recruitment. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001222. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moayeri M, Leppla SH. Cellular and systemic effects of anthrax lethal toxin and edema toxin. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:439–455. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moayeri M, Leppla SH. Anthrax toxins. In: Bergman NH, editor. Bacillus anthracis and anthrax. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2011. pp. 121–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mongkolthanaruk W, Robinson C, Moir A. Localization of the GerD spore germination protein in the Bacillus subtilis spore. Microbiology. 2009;155:1146–1151. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.023853-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre WW, Daefler S, Schneewind O. Cell wall sorting of lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:441–446. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.441-446.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman ZL, Leppla SH, Moayeri M. CA-074Me protection against anthrax lethal toxin. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4327–4336. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00730-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okugawa S, Moayeri M, Eckhaus MA, Crown D, Miller-Randolph S, Liu S, et al. MyD88-dependent signaling protects against anthrax lethal toxin-induced impairment of intestinal barrier function. Infect Immun. 2011;79:118–124. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00963-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Leppla SH. Optimized production and purification of Bacillus anthracis lethal factor. Protein Expr Purif. 2000;18:293–302. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passalacqua KD, Varadarajan A, Ondov BD, Okou DT, Zwick ME, Bergman NH. The structure and complexity of a bacterial transcriptome. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3203–3211. doi: 10.1128/JB.00122-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelczar PL, Igarashi T, Setlow B, Setlow P. Role of GerD in germination of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1090–1098. doi: 10.1128/JB.01606-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit CM, Brown JR, Ingraham K, Bryant AP, Holmes DJ. Lipid modification of prelipoproteins is dispensable for growth in vitro but essential for virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;200:229–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantsev AP, Camp A, Leppla SH. A new minimal replicon of Bacillus anthracis plasmid pXO1. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5134–5146. doi: 10.1128/JB.00422-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantsev AP, Sitaraman R, Galloway CR, Kivovich V, Leppla SH. Genome engineering in Bacillus anthracis using Cre recombinase. Infect Immun. 2006;74:682–693. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.682-693.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman O, Cummings SP, Harrington DJ, Sutcliffe IC. Methods for the bioinformatic identification of bacterial lipoproteins encoded in the genomes of Gram-positive bacteria. World J Microb Biotech. 2010;24:2377–2382. [Google Scholar]

- Richter S, Anderson VJ, Garufi G, Lu L, Budzik JM, Joachimiak A, et al. Capsule anchoring in Bacillus anthracis occurs by a transpeptidation reaction that is inhibited by capsidin. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:404–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigden DJ, Galperin MY. Sequence analysis of GerM and SpoVS, uncharacterized bacterial ‘sporulation’ proteins with widespread phylogenetic distribution. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1793–1797. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robichon C, Vidal-Ingigliardi D, Pugsley AP. Depletion of apolipoprotein N-acyltransferase causes mislocalization of outer membrane lipoproteins in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:974–983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Bacterial adherence to polystyrene: a replica method of screening for bacterial hydrophobicity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;42:375–377. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.2.375-377.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. A Laboratory Manual Cold Spring Harbor. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. Molecular Cloning. [Google Scholar]

- Sastalla I, Chim K, Cheung GY, Pomerantsev AP, Leppla SH. Codon-optimized fluorescent proteins designed for expression in low GC Gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:2099–2110. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02066-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. Spore germination. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Kida Y, Kuwano K. A dipalmitoylated lipoprotein from Mycoplasma pneumoniae activates NF-kappa B through TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6. J Immunol. 2005;175:4641–4646. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll H, Dengjel J, Nerz C, Gotz F. Staphylococcus aureus deficient in lipidation of prelipoproteins is attenuated in growth and immune activation. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2411–2423. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2411-2423.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe IC, Harrington DJ. Pattern searches for the identification of putative lipoprotein genes in Gram-positive bacterial genomes. Microbiology. 2002;148:2065–2077. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-7-2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Muhlradt PF, Morr M, Radolf JD, Zychlinsky A, et al. Discrimination of bacterial lipoproteins by Toll-like receptor 6. Int Immunol. 2001;13:933–940. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Sato S, Horiuchi T, Hoshino K, Takeda K, Dong Z, et al. Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 1 in mediating immune response to microbial lipoproteins. J Immunol. 2002;169:10–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakran S, Li H, Lavine CL, Miller MA, Bina JE, Bina XR, Re F. Identification of Francisella tularensis lipoproteins that stimulate the toll-like receptor (TLR) 2/TLR1 heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3751–3760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga M, Tokunaga H, Wu HC. Post-translational modification and processing of Escherichia coli prolipoprotein in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:2255–2259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.7.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RC, Rees ML, Jacobs MF, Pragai Z, Thwaite JE, Baillie LW, et al. Production of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen is dependent on the extracellular chaperone, PrsA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18056–18062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JA, Collier RJ. Anthrax toxin: receptor-binding, internalization, pore formation, and translocation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:243–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.