Abstract

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) is an infrequent cardiac syndrome characterized by acute onset chest pain with apical ballooning on echocardiography. It is often triggered by severe emotional or physical stress, and in contrast to acute myocardial infarction (AMI), the regional wall motion abnormality returns to normal within days. Here, we describe a 62-year-old female who presented with acute onset chest pain during treatment for a liver abscess. We presumed a diagnosis of AMI because of ST segment elevation on electrocardiography and elevated cardiac enzyme levels. However, the patient's coronary arteries were normal on angiography, and apical ballooning was seen on echocardiography. A diagnosis of TTC was made, and the patient was managed with intensive cardiopulmonary support using vasopressors in our hospital's medical intensive care unit. The patient's symptoms improved, but persistent severe left ventricular dysfunction was detected on follow-up echocardiography. After 5 weeks, a new apical mural thrombus appeared, and anticoagulation therapy was started. The apical ballooning persisted 3 months later, although the patient's overall ejection fraction was slightly improved. The apical thrombus was completely resolved without any embolic event. Non-adrenergic inotropics can be recommended in TTC with shock, and clinicians should keep in mind the potential risk of thrombus formation and cardioembolism.

Keywords: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, Persistent apical ballooning, Thrombus

INTRODUCTION

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) is a novel heart syndrome involving transient left ventricular (LV) dysfunction with symptoms and signs similar to acute coronary syndrome. This disorder is usually triggered by emotional or physical stress, and is believed to be associated with sympathetic stimulation mediated by excessive plasma catecholamine levels [1]. In general, patients with TTC have a favorable prognosis because the wall motion abnormality returns to normal within days, and certainly within the first month, without complications [2]. Here we describe a case of TTC with persistent LV dysfunction accompanied by an apical thrombus.

CASE REPORT

A 62-year-old female was referred to the emergency department at Asan Medical Center for management of alleged acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Six days before, the patient had been admitted to a local hospital with fever and abdominal pain. An abdominal computed tomography scan showed a large (9 × 8 cm) multi-septated abscess in segment VIII of the liver, with adjacent hepatic venous thrombosis (Fig. 1A). Empirical antibiotics for the liver abscess were started, and pus was drained with an 8.5 Fr pigtail catheter. Klebsiella oxytoca was isolated from the pus and blood samples. During supportive care, acute onset of chest pain and dyspnea occurred. Electrocardiography (ECG) revealed an ST elevation in leads V3-V6, with poor R progression (Fig. 2). Additionally, the patient's troponin I level was elevated (4.10 ng/mL, normal < 1.5). The patient was subsequently transferred with a diagnosis of ST segment elevation AMI.

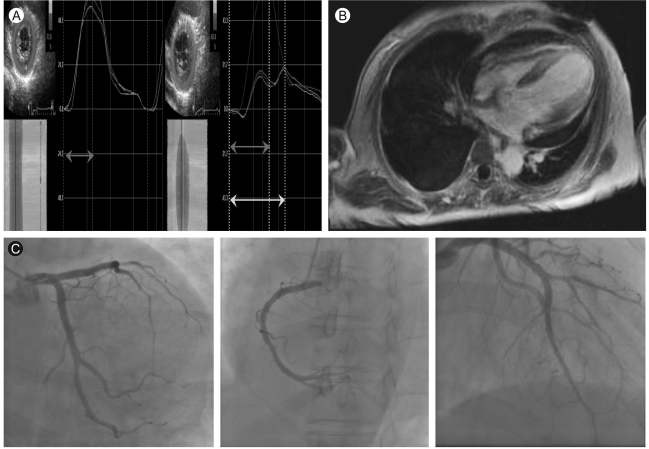

Figure 1.

(A) Abdominal computed tomography scan showing a large (9 × 8 cm) clustered cystic looking mass in segment VIII of the liver indicating an abscess. (B) Four-chamber view cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (T1WI). Note the absence of delayed hyperenhancement in the affected myocardium. (C) Normal coronary angiographic findings.

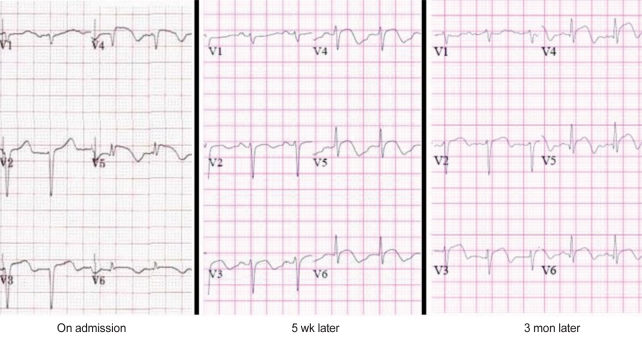

Figure 2.

Electrocardiographic time course showing persistent ST segment elevation and improved R progression.

A clinical examination revealed an anxious patient in acute respiratory distress. The patient's vital signs included blood pressure of 91/62 mmHg, temperature of 37.7℃, respiratory rate of 28 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 88% on room air. Decreased breath sounds at the base of the right lung and diffuse crackles in the lower two-thirds of both lung fields were found by lung auscultation. Cardiac examination showed a regular rhythm with no gallops or murmurs. The electrocardiographic findings were similar to those at the other hospital, with a ventricular response rate of 120 bpm (Fig. 2). Laboratory findings included a B-type natriuretic peptide level of 1,512 pg/mL, white blood cell count of 18,600/mm3 with predominant neutrophils, and C-reactive protein level of 14.44 mg/dL. Troponin I was normalized. ECG revealed severely impaired LV function, with an ejection fraction of 30% and akinesia in the mid- to distal portion of the LV chamber (Fig. 3A and 3B). TTC was suspected given the presence of a stressful physical condition along with the typical appearance of apical ballooning on echocardiography. We confirmed the diagnosis by coronary angiography, which showed normal epicardial coronary vessels (Fig. 1C).

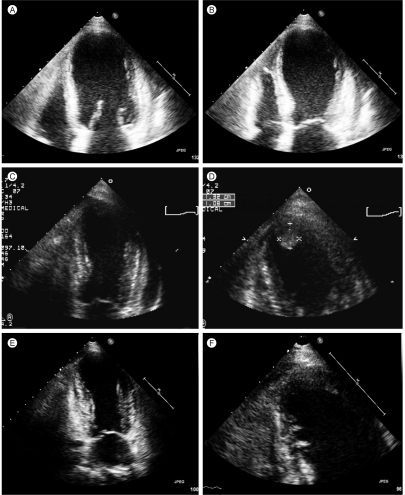

Figure 3.

(A, B) Initial echocardiograph showing apical ballooning in the systolic phase. (C, D) Follow-up echocardiograph showing a newly developed round echogenic mass in the left ventricular (LV) apex 5 weeks later. The akinesia of the mid-to-distal portion of the LV chamber is persistent but slightly improved. (E, F) Follow-up echocardiograph 3 months later showing persistent apical ballooning but improved LV function. The thrombus is completely resolved.

Soon after, the patient's systolic blood pressure dropped to 70 mmHg. Hypotension persisted even after appropriate fluid resuscitation. The patient was transferred to the medical intensive care unit (ICU) and given vasopressors, dobutamine, and diuretic support. After 5 days in the ICU, the patient became hemodynamically stable, with improved symptoms and chest radiographic findings. Seven days after admission, follow-up echocardiography revealed persistent apical ballooning, with an ejection fraction of 18%. On the other hand, the patient's general condition in terms of her liver abscess and bacteremia was improving.

Medical treatment for heart failure with a beta-blocker, nitrate, diuretics, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor was continued. Persistent LV dysfunction was noted on serial echocardiography 3 weeks later; thus, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed to rule out other causes of the LV dysfunction. There were no signs of tissue hyperenhancement in the dysfunctional apical regions, indicating the absence of scarred myocardial tissue (Fig. 1B). Other conditions such as infiltrating diseases could be ruled out.

Five weeks after admission, the patient's LV dysfunction was slightly improved, with an ejection fraction of 36% on follow-up echocardiography; however, a newly developed apical thrombus was noted (Fig. 3C and 3D). Full-dose heparin was administered followed by oral anticoagulation therapy with warfarin. There was no embolic event throughout the patient's hospital stay.

Three months later, follow-up echocardiography showed persistent akinesia of the LV apex with slightly improved contractility of the mid-ventricular wall segment (Fig. 3E). The measured ejection fraction was 40%, and the apical thrombus was completely resolved (Fig. 3F).

DISCUSSION

This case involves an unusual form of TTC with persistent apical ballooning lasting longer than 3 months and complicated by a thrombus at the LV apex. TTC, or "stress-induced cardiomyopathy," is characterized by resting chest pain, electrocardiographic changes mimicking AMI, and minimal myocardial enzyme release without obstructive coronary artery stenosis. The hallmark of TTC on echocardiography is akinesis or dyskinesis of the LV apical and mid-ventricular segments accompanied by normal to hyperkinetic basal segments, which cannot be explained by the occlusion of a single vascular territory [3].

Since its original description in Japanese studies, several case series have been published, and clinical features have been identified [4]. Most patients are postmenopausal women, and the event is often triggered by emotional or physical stress. In the present case, septic conditions associated with a liver abscess or the drainage procedure itself could have been the precipitating physical stress. Although the initial presentation of TTC is acute and appears to be severe, the overall prognosis is excellent, with an in-hospital mortality rate below 2% [5]. With symptomatic management, the wall motion abnormality usually returns to normal within days, and certainly within the first month [2]. This is why TTC is also called "transient" apical ballooning syndrome. From this point of view, our case can be distinguished from those described previously.

Although the patient's ejection fraction improved slightly over the follow-up course, the finding of apical ballooning persisted 3 months after admission. The precise reason is unclear, but vasopressors, which were used to maintain adequate blood pressure in the ICU, could be the cause. There seems to be no dispute that the syndrome is due to a sudden surge in catecholamines, but the mechanism underlying the association between sympathetic stimulation and myocardial stunning is unknown. Catecholamine-induced direct myocyte injury or microvascular spasm is a possible mechanism [1]. Norepinephrine was administered to our patient, and this drug could have had an additional effect on the heart, perpetuating the syndrome. This case report supports the use of non-adrenergic inotropics when TTC-related serious hemodynamic compromise occurs.

Another interesting finding was the appearance of the apical thrombus. Rare complications associated with TTC have been reported recently, including cardiogenic shock, ventricular arrhythmias, mitral valve dysfunction, LV rupture, and LV mural thrombus [6,7]. The clinical impact is that the thrombus is a potential source of embolic events. In fact, reported cases of cardioembolic stroke and renal infarction support this idea [8-10]. As low blood flow in the LV apex during apical ballooning akinesis is the presumed cause of thrombus formation, a subclinical thrombus can exist in TTC, and the true incidence may be much higher than predicted. Although the role of prophylactic anticoagulants in TTC should be examined further, clinicians should recognize the possibility of thrombus formation and consider the use of anticoagulation therapy in practice.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of persistent LV dysfunction complicated by a LV mural thrombus associated with TTC in Korea.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdulla I, Ward MR. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy: how stress can mimic acute coronary occlusion. Med J Aust. 2007;187:357–360. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:858–865. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dote K, Sato H, Tateishi H, Uchida T, Ishihara M. Myocardial stunning due to simultaneous multivessel coronary spasms: a review of 5 cases. J Cardiol. 1991;21:203–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osherov A, Matetzky S, Beinart R, Hod H. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning (Tako-tsubo): the syndrome that mimics acute myocardial infarction. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004;6:550–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuchihashi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T, et al. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: a novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Angina Pectoris-Myocardial Infarction Investigations in Japan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JH, Kang SJ, Song JK, et al. Left ventricular apical ballooning due to severe physical stress in patients admitted to the medical ICU. Chest. 2005;128:296–302. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasaki N, Kinugawa T, Yamawaki M, et al. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning in a patient with bicuspid aortic valve created a left ventricular thrombus leading to acute renal infarction. Circ J. 2004;68:1081–1083. doi: 10.1253/circj.68.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sánchez Flores M, Marcos Martin M, Cruz Gonzalez I, Martin Herrero F. Intraventricular thrombus associated with Tako-Tsubo syndrome in a patient with previous transient ischemic stroke. Med Clin (Barc) 2005;125:237. doi: 10.1157/13077382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuoka K, Nakayama S, Okubo S, Fujii E, Uchida F, Nakano T. Transient cerebral ischemic attack induced by transient left ventricular apical ballooning. Eur J Intern Med. 2004;15:393–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]