Abstract

A new isolate of Alternanthera mosaic virus (AltMV-MU) was purified from Portulaca grandiflora plants. It has been shown that the AltMV-MU coat protein (CP) can be efficiently reassembled in vitro under different conditions into helical RNA-free virus-like particles (VLPs) antigenically related to native virus. The AltMV-MU and VLPs were examined by atomic force and transmission electron microscopies. The encapsidated AltMV-MU RNA is nontranslatable in vitro. However, it can be translationally activated by CP phosphorylation or by binding to the TGB1protein from the virus-coded movement triple gene block.

Keywords: Alternanthera mosaic virus, coat protein, potexviruses, translation activation, triple gene block protein 1, virus-like particles.

Flexible filamentous virions of Alternanthera mosaic virus (AltMV) are typical for the family Flexiviridae (genus Potexvirus) [1]. AltMV was purified from Alternanthera pungenes (Amaranthaceae) in Australia by Geering and Thomas [2] who showed that AltMV was closely related to Papaya mosaic virus (PapMV). A potexvirus from symptomless portulaca plants (AltMV-Po) has been also isolated and characterized in Italy [3]. Furthermore, the AltMV isolates from phlox (AltMV-PA) and portulaca were identified in the United States [4]. Recently, the complete nucleotide sequence of the genome of another AltMV isolate (AltMV-MU) has been determined by our group and deposited in GenBank (accession number FJ822136) [5]. The RNA sequence analysis allowed to characterize AltMV-MU as a separate strain with a new genotype. In the present work some properties of the virions and the coat protein (CP) of AltMV-MU that caused symptomless infection in Portulaca grandiflora plants were investigated.

TRANSMISSION ELECTRONIC AND ATOMIC FORCE MICROSCOPY OF VIRIONS AND VIRUS-LIKE PARTICLES FORMED BY ALTMV-MU COAT PROTEIN

The AltMV-MU has been propagated in P. grandiflora and purified from systemically infected leaves by the method developed for potato virus X (PVX) purification [6] using a modified (50mM Tris-HCl, 10mM EDTA pH 8.0) extraction buffer. Virus concentration was estimated using an average extinction coefficient of 2.84 for potexviruses [2]. Purified virus had an A260/A280 ratio of 1.44 and yield was of 0.34 mg/g of leaves harvested at 21-25 days after inoculation.

Viral RNA was isolated from the purified viral particles by phenol deproteinization. The method of salt deproteinization with 2M LiCl described for PVX CP [7] was used to obtain the AltMV CP preparation. The extinction coefficient of 0.7 for AltMV CP was calculated (http://us.expasy.org/tools/protparam.html).

A single protein band with apparent size of 22 kDa was observed when dissociated virions and purified CP preparations were analyzed by 8-20% SDS-PAGE and Western blot (Fig. 1). The Mr of the protein deduced from the amino acid sequence was 22, 1 x 103 which was close to the value determined by SDS-PAGE.

Fig. (1).

1 µg of purified AltMV-MU virions and CP preparation were analysed in 8-20% SDS-PAGE. Lane M shows molecular weight markers (Fermentas). Gel was stained with Coomassie G-250. Western blot (WB): proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane and incubated with mouse AS to AltMV-MU virions (dilution 1:10000) and anti-mouse antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Promega); the reaction was visualized by the ECL system (Amersham Biosciences).

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) on copper grids [8], the purified viral particles (60 µg/ml) and CP aggregates (60 µg/ml) were negatively stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate. Particles lengths were measured manually from digital prints by Image J program. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurement was carried out using a NanoScope IIIa multimode-scanning probe microscope (Digital Instruments) in tapping mode in air, as described previously [8, 9].

According to the TEM data, the mean length and diameter of AltMV-MU virion were 570 nm and 13 nm, respectively (Fig. 2a). Based on AFM images, the virions average height was 6-8 nm (Fig. 2b).

Fig. (2).

TEM and AFM images of AltMV-MU virions and VLPs assembled from AltMV-MU CP at different pH-conditions: AltMV-MU virions at pH 8.0 (a, b); AltMV-MU CP at pH 4.0 (c, d); AltMV-MU CP at pH 8.0 (e, f). TEM images - (a, c, e); AFM images - (b, d, f). Scale bars represent 500 nm (a, c, e).

The ability of PapMV CP to assemble VLPs in vitro at pH 4.0 in the absence of genomic RNA is known since seventies [10]. By contrast, assembly of PapMV CP at pH 8.0 was limited by production of “small 13-33S aggregates” [10]. Here, we examined the ability of RNA-free CP AltMV-MU to form VLPs under those conditions.

We found that similarly to PapMV CP, AltMV-MU CP could be assembled in vitro into VLPs at pH 4.0 and low ionic strength. In 0.01M citrate buffer, pH 4.0 a considerable part of AltMV-MU VLPs stuck together producing long bundles (Fig. 2c, d). However, in contrast to PapMV, TEM and AFM analyses showed that AltMV-MU CP formed filamentous VLPs at pH 8.0 as well (Fig. 2e, f). In 0.01M Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.0, AltMV-MU CP formed VLPs, comparable in size to virus particles under the same condition (0.01M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0) or even exceeding them in length (Fig. 2a, b, e, f). In agreement with the AFM data the length of VLPs formed by AltMV-MU CP at pH 8.0 ranged from 60 nm to 2000 nm, the height was of 6-7 nm and the width of about 20 nm (Fig. 2f).

Apparently, the assembly of AltMV-MU CP into VLPs was less dependent on pH than that of PapMV. Therefore, the conditions of assembly and the size of the products formed from AltMV-MU and PapMV CPs were considerably different [10].

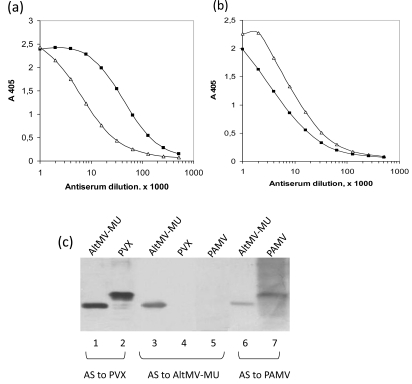

IMMUNOLOGICAL PROPERTIES OF VIRIONS AND VIRUS-LIKE PARTICLES

Antigenic specificity of AltMV-MU virions was compared with that of RNA-free VLPs assembled from AltMV-MU CP at pH 4.0. Antisera against AltMV-MU virions and VLPs have been obtained using a purified native virus preparation and a preparation of VLPs assembled at the pH 4.0 as antigens. Antigenic properties of AltMV-MU and VLPs were compared by indirect ELISA [11]. Purified preparations of native AltMV-MU and VLPs, both diluted with PBS pH 7.4 up to the concentration of 5 µg/ml, were applied to the wells of MaxiSorp microplate (Nunc) and adsorbed at 4°C overnight. Mouse antisera to AltMV-MU and VLPs as well as non-immune mouse serum used as a negative control were titrated against each antigen. Horseradish peroxidase-labelled anti-mouse IgG W402 (Promega) was used as detection antibodies.

Mouse antiserum to native AltMV-MU recognized the homologous antigen and some VLPs antigenic determinants which presumably are common for both structures but differently exposed on the VLPs and the native virus (Fig. 3a). Similarly, mouse antiserum to VLPs strongly reacted with VLPs and also with native AltMV-MU even though the reaction with the virus was clearly weaker (Fig. 3b). These data indicate that native AltMV-MU and VLPs are antigenically related, but not identical. This was not surprisingly because native virus particles (Fig. 2b) and VLPs assembled at the pH 4.0 in the absence of genomic RNA (Fig. 2d) looked quite different morphologically suggesting some differences in their antigenic properties. In particular, some CP epitopes exposed at the surface of native virus particle, could be found hidden or disrupted at the VLPs assembly. On the other side, the neotope appearance cannot be ruled out at the VLPs formation.

Fig. (3).

Antigenic comparison of native AltMV-MU and VLPs by indirect ELISA. Mouse antisera to AltMV-MU (a) and to VLP (b) were titrated on AltMV-MU (—■—) or VLP (—Δ—) adsorbed on microplate. (c) Western blot analysis of purified virions of AltMV-MU (lanes 1, 3 and 6), PVX (lanes 2 and 4), PAMV (lanes 5 and 7). Horizontal brackets indicate reactions of PVX antiserum (AS to PVX), AltMV-MU antiserum (AS to AltMV-MU) and PAMV antiserum (AS to PAMV) to AltMV-MU, PVX, PAMV virions.

The AltMV-MU, PVX and Potato aucuba mosaic virus (PAMV), members of Potexvirus group were analyzed by Western blotting. Blots were developed with polyclonal antisera against PVX diluted 1:20000, AltMV-MU - 1:10000 and PAMV - 1:3000 (Fig. 3c). Both antisera to PVX and PAMV have been found to react with the AltMV-MU (Fig. 3c, lanes 1, 6). At the same time, the antiserum to AltMV-MU reacted neither with PVX nor with PAMV (Fig. 3c, lanes 4, 5). Phylogenetic analysis of 26 coat protein sequences from genus Potexvirus was performed previously [5]. It shows that all three proteins are distanly located from each other within the appropriate tree that might explain the absence of cross-reactivity in case of antiserum to AltMV-MU.

TRANSLATIONAL ACTIVATION OF ALTMV-MU VIRIONS BY TGB1 PROTEIN

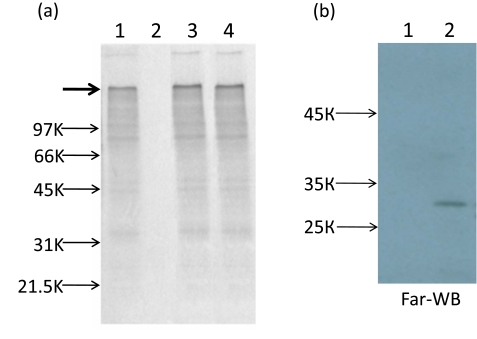

Recently we have shown that, contrary to Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) and some other viruses, encapsidated PVX RNA was completely nontranslatable in vitro. The translational activation of PVX virions may be reached by two ways: either phosphorylation of PVX CP or TGB1 (triple gene block 1) protein binding to terminal subunits of the polar PVX helix, TGB1 is one of three PVX movement proteins [6, 12]. It is believed that binding of TGB1 to one end of PVX particles induces a structural transition (remodeling) of the PVX CP into a metastable form. As a result of this transition, the 5' end of viral RNA becomes accessible for ribosomes [13]. Here, we report that similarly to virion PVX RNA, AltMV-MU encapsidated RNA was also untranslatable in vitro (Fig. 4b, lane 2) but could be activated by CP phosphorylation of the AltMV-MU virions by protein kinase C (PKC) (Fig. 4a, lane 3).

Fig. (4).

(a) Translational activation of encapsidated AltMV-MU RNA in vitro. SDS-PAGE in 8-20% polyacrylamide gel of 35S-labeled translation products in the wheat germ extract. Gel was dried and autoradiographed. Translation of purified AltMV-MU RNA (lane 1); AltMV-MU virions (lane 2); AltMV-MU virions after phosphorylation with PKC (lane 3), AltMV-MU preparations incubated with AltMV-MU TGB1 (lane 4). AltMV-MU RNA concentration in the translation sample was 40 µg/ml. Arrows indicate the positions of molecular weight markers and the bold arrow indicates the position of the protein encoded by the 5'- proximal AltMV-MU replicase gene (174 kDa). (b) Far-western blot (Far-WB) analysis of interaction of different TGB1 proteins with CP AltMV-MU at pH 8.0. Purified TGB1 PAMV (1 µg, lane 1, negative control) and TGB1 AltMV-MU (1 µg, lane 2) proteins were separated by 8-20% SDS-PAGE. TGB1s were transferred to PVDF membrane, incubated with CP AltMV-MU (5µg/ml), mouse AS to CP AltMV-MU (dilution 1:10000) and anti-mouse antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Promega); reaction was visualized by the ECL system (Amersham Biosciences).

A similar effect could be reached as a result of interaction of virions with AltMV-MU TGB1. The AltMV-MU TGB1 with N-terminal thioredoxin (Trx-tag), S-tag and His-tag was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain using the pET 32(a)+ vector according to a Novagen protocol (Novagen pET System Manual, 11th Edition). The fusion protein with His-tag was purified using Ni-NTA affinity resin (Qiagen) and then specifically digested with enterokinase (Novagen, Tag-off rEK Cleavage/Capture Kit) to remove the Trx-tag, S-tag and His-tag. The data presented at Fig. (4a) lane 4 showed that putative TGB1-CP AltMV-MU interaction resulted in translation of encapsidated genome RNA in vitro. This interaction was confirmed by Far-western blot analysis (Fig. 4b). It could be presumed that two ways of translational activation of encapsidated RNA are peculiar features of some other members of genus Potexvirus.

It is known that the PapMV VLPs have been used successfully as an epitope presentation system. Moreover, PapMV VLP platforms have the advantage of triggering both arms of the immune responses, namely, the humoral and CTL responses, a characteristic that is unique for vaccine platforms [14, 15]. As mentioned above, AltMV-MU is closely related to papaya mosaic virus (PapMV) [5]. We believe that AltMV-MU VLPs can be regarded as good candidates for presentation of foreign epitopes as well.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Stephan Winter (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig) for providing the initial portulaca isolate and Dr Sergey Saunin and Mikhail Savvateev (AIST-NT Company) for Atomic force microscopy assays. This work was funded in part by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Grant No. 10-04-000-89-a) and the Federal Agency of Science and Innovation (FASI) (contracts No 16.512.11.2184).

REFERENCES

- 1.Martelli GP, Adams MJ, Kreuze JF, Dolja VV. Family Flexiviridae: A case study in virion and genome plasticity. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2007;45:73–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.45.062806.094401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geering AD, Thomas JE. Characterisation of a virus from Australia that is closely related to papaya mosaic potexvirus. Arch Virol. 1999;144:577–92. doi: 10.1007/s007050050526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciuffo M, Turina M. A potexvirus related to Papaya mosaic virus isolated from moss rose (Portulaca grandiflora) in Italy. Plant Pathol. 2004;53:515. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammond J, Reinsel MD, Maroon-Lango CJ. Identification and full sequence of an isolate of Alternanthera mosaic potexvirus infecting Phlox stolonifera. Arch Virol. 2006;151:477–93. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0646-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivanov PA, Mukhamedzhanova AA, Smirnov AA, Rodionova NP, Karpova OV, Atabekov JG. The complete nucleotide sequence of Alternanthera mosaic virus infecting Portulaca grandi?ora represents a new strain distinct from phlox isolates. Virus Genes. 2011;42:268–71. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0556-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atabekov JG, Rodionova NP, Karpova OV, Kozlovsky SV, Novikov VK, Arkhipenko MV. Translational activation of encapsidated potato virus X RNA by coat protein phosphorylation. Virology. 2001;286:466–74. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homer RB, Goodman RM. Circular dichroism and fluorescence studies on potato virus X and its structural components. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;378:296–304. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(75)90117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karpova OV, Zayakina OV, Arkhipenko MV, et al. Potato virus X RNA-mediated assembly of single tailed ternary “coat protein-RNA-movement protein” complexes. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2731–40. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81993-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiselyova OI, Yaminsky IV, Karpova OV, et al. AFM study of potato virus X disassembly induced by movement protein. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:321–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00835-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erickson JW, Bancroft JB, Horne RW. The assembly of papaya mosaic virus protein. Virology. 1976;72:514–7. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark MF, Adams AN. Characteristics of the microplate method of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of plant viruses. J Gen Virol. 1977;34:475–83. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-34-3-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atabekov JG, Rodionova NP, Karpova OV, Kozlovsky SV, Poljakov VY. The movement protein-triggered in situ conversion of potato virus X virion RNA from a nontranslatable into a translatable form. Virology. 2000;271:259–63. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodionova NP, Karpova OV, Kozlovsky SV, Zayakina OV, Arkhipenko MV, Atabekov JG. Linear remodeling of helical virus by movement protein binding. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:565–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denis J, Majeau N, Acosta-Ramirez E, et al. Immunogenicity of papaya mosaic virus-like particles fused to a hepatitis C virus epitope: evidence for the critical function of multimerization. Virology. 2007;363:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leclerc D, Beauseigle D, Denis J, et al. Proteasome-independent major histocompatibility complex class I cross-presentation mediated by papaya mosaic virus-like particles leads to expansion of specific human T cells. J Virol. 2007;81:1319–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01720-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]