Abstract

A choriocarcinoma component with a malignant tumor is relatively rare. We present a case of an 85-year-old woman with mixed carcinoma, which was endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation, choriocarcinoma and a disseminated peritoneal nodule, which was papillary serous adenocarcinoma. The patient received surgery and conservative treatment. Twenty weeks after surgery, a recurring tumor appeared at the Douglas pouch. Histology showed that the recurring tumor was poorly differentiated carcinoma that was very different from the primary tumor. This case represents an unusual uterine corpus cancer with high-grade transformation with serous and choriocarcinomatous differentiation. This case also demonstrates the capacity of tumor cells to differentiate into divergent elements.

Keywords: hCG, choriocarcinoma, endometrial cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, trophoblastic tumor.

Introduction

Most cases of choriocarcinoma occur in the uterine body and arise from chorionic villi following a normal or abnormal gestation. Non-gestational choriocarcinoma is relatively rare. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus with another histological type is usually squamous cell carcinoma, serous or clear cell adenocarcinoma and sarcoma, and there have been a few reports of choriocarcinoma 1-3. We report a patient who had mixed cancer with three distinct histological types: endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation, choriocarcinoma in the uterine body and a disseminated peritoneal nodule showing papillary serous adenocarcinoma.

Case report

An 85-year old woman, gravida 5, parity 2 with menopausal status for 27 years presented with postmenopausal bleeding. A physical examination revealed a bulky uterus with pyometra. A subsequent transvaginal ultrasound showed an endometrial mass, measuring approximately 1.8 cm in diameter. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a mass in the uterine cavity with myometrial invasion, which is consistent with the ultrasound findings.

Using [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) / computed tomography (CT), we observed a uterine tumor with increased uptake and intense uptake in the left paracolic region indicating peritoneal dissemination, without signs of distant metastases.

Serum hCG-β subunit, CA19-9 and CEA levels were elevated to 8.0 ng/ml (normal, < 0.1 ng/ml), 127.6 U/ml (normal, < 37 U/ml), and 8.1 U/ml (normal, < 5 ng/ml), respectively. Serum CA-125 levels were within the normal range.

In an endometrial biopsy specimen, the tumor was diagnosed as serous or endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Under the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and multiple biopsies were performed. During laparotomy, the uterine fundus and body appeared mildly bulky. The surface of the sigmoid colon was disseminated with several subcentimetric tumor foci.

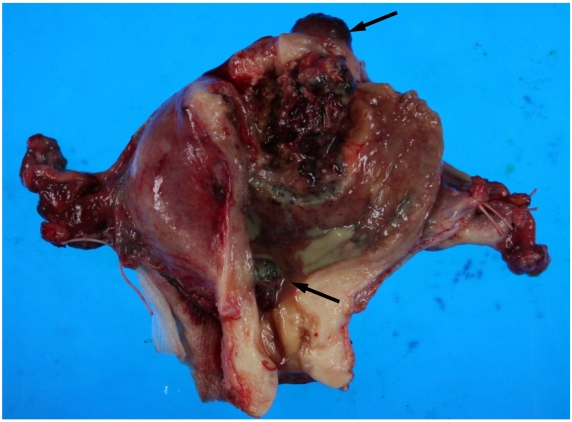

On macroscopic examination of the uterine specimen, a huge ulceroinfiltrative necrotic mass was located on the posterior wall, and a hemorrhagic nodule was located in the serosa of the uterine fundus and internal cervical os (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gross findings of the uterus. A huge ulceroinfiltrative necrotic mass measuring 40 × 40 mm is located on the posterior wall and a diffuse dark reddish hemorrhagic nodule (arrows) is located in the serosa of the uterine fundus and internal cervical os.

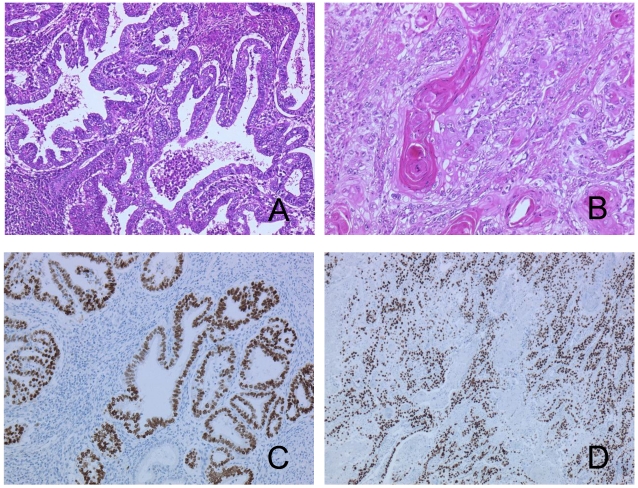

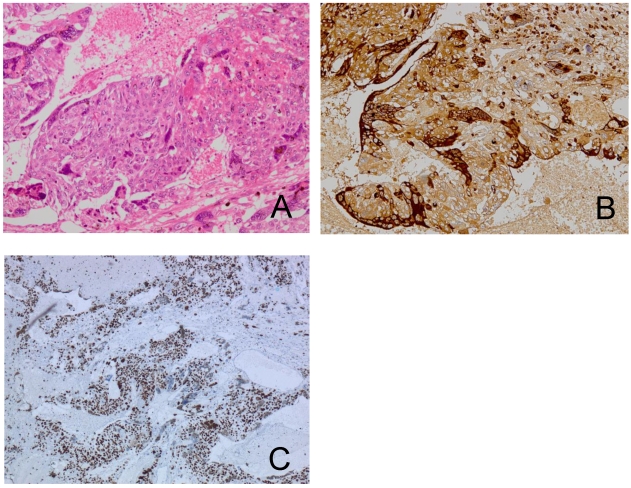

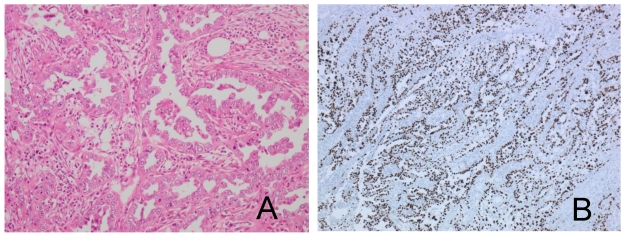

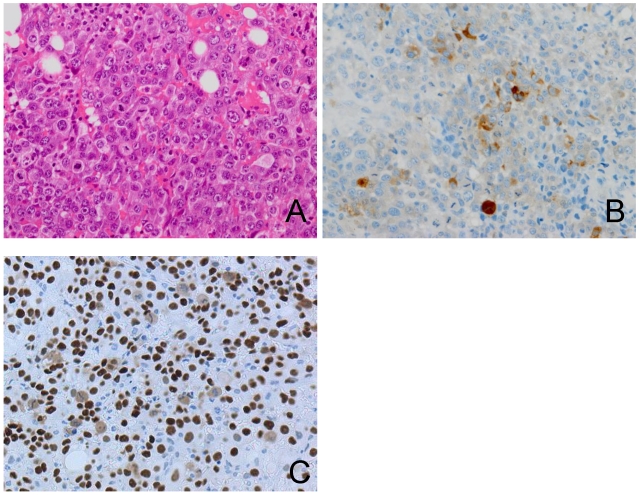

A pathological examination revealed three distinct histological types. Approximately half of the tumor showed an endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation (Figure 2A, 2B). The hemorrhagic nodule showed a choriocarcinoma component with a two-cell pattern that had syncytiotrophoblast-like and cytotrophoblast-like elements (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemical staining for hCG-β subunit was positive, especially in the syncytiotrophoblast-like element (Figure 3B). This component was indicative of choriocarcinoma. Other pathological elements did not reveal any hCG-β subunit-producing cells. The biopsy specimen derived from peritoneal dissemination of the sigmoid colon showed a serous papillary adenocarcinoma (Figure 4A). Positive immunohistochemical nuclear staining of p53 was detected in three distinct histological types (Figure 2C, 2D, 3C and 4B).

Figure 2.

The tumor shows endometrioid adenocarcinoma (A) with squamous differentiation (B). The same components in p53 stained sections (C, D).

Figure 3.

The choriocarcinoma component is composed of syncytiotrophoblast-like cells and cytotrophoblast-like cells (A). Immunohistochemical staining for hCG-β subunit of the choriocarcinoma component shows a positive reaction in syncytiotrophoblast-like cells (B). The same components in p53-stained sections (C).

Figure 4.

Peritoneal dissemination of the sigmoid colon shows papillary serous adenocarcinoma (A) and p53 positivity (B).

Considering the advanced age of the patient, adjuvant therapy was avoided. Twenty weeks later, serum hCG-β subunit was elevated to 55 ng/ml. Transvaginal ultrasound showed a 5.2 × 5.3 cm-sized cul-de-sac mass. Five months after surgery, the cul-de-sac mass was enlarged to 14.4 × 8.0 cm and caused rectosigmoid colonic obstruction. The patient underwent diverting colostomy to relieve the obstruction. A surgical biopsy showed poorly differentiated carcinoma with mononuclear cells (Figure 5A) without any primary pathological features, although immunohistochemical staining for hCG-β subunitand p53 was positive in part of the mononuclear cells, suggested cytotrophoblastic differentiation (Figure 5B and 5C).

Figure 5.

The recurring tumor shows poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with numerous mitoses (A). Immunohistochemical staining for hCG-β subunit and p53 shows a positive reaction in part of the mononuclear cells (B, C).

Discussion

The combination of choriocarcinoma and other histological types has been reported in association with some human cancers, predominantly with the female genital tract 1-3 and rarely with carcinomas of the esophagus 4, bladder or renal pelvis 5, 6, stomach 7, rectum 8, lung 9, and breast 10. In gynecological cases, an endometrioid adenocarcinoma with a choriocarcinoma component is a rare event with a highly aggressive clinical course 2, 3.

In our case, because no pre-existing endometrium and endometrial hyperplasia localized with squamous and choriocarcinoma lesion, we considered this case showed the primary tumor which had three components: endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous and choriocarcinomatous differentiation and papillary serous adenocarcinoma. Interestingly, the recurring tumor was poorly differentiated carcinoma with mononuclear cells that were different from primary pathological features.

For the mechanism of development of a mixed tumor including a component of a choriocarcinoma, three hypotheses have been postulated: 1) de-differentiation of epithelial cells into choriocarcinomas 1, 7, 11; 2) germ cells that fail to complete their migration to the gonads 11; and 3) multidirectional tumor differentiation from a common stem cell 1. Some researchers have suggested that some cancers may originate from cancer stem cells. Recently, a small population of endometrial epithelial stem/progenitor cells was identified in normal human endometrium 12, 13. Several studies have found that the endometrioid adenocarcinoma cell line contains a subpopulation of tumor initiating cells with stem-like properties. It is likely that the bulk of cells within a tumor consist of stem/progenitor cells and more differentiated cells 3, 14, 15.

Our case presented with unique characteristics. The primary tumor showed three distinct histological types and the recurring tumor was poorly differentiated carcinoma with mononuclear cells that were different from the primary pathological features. Metastases usually reflect the histology of the primary tumor. These alterations suggest that multidirectional tumor was probably derived from aberrant differentiation of the somatic epitherial cells of the endometrioid adenocarcinoma, or might occur from a common stem cell. However, further studies on the pathogenesis of mixed tumors are required to determine this issue.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Ushio and Kinoshita for their excellent technical assistances.

References

- 1.Yamada T, Mori H, Kanemura M. et al. Endometrial carcinoma with choriocarcinomatous differentiation: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113(2):291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akbulut M, Tosun H, Soysal ME, Oztekin O. Endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium with choriocarcinomatous differentiation: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278(1):79–84. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0526-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horn LC, Hanel C, Bartholdt E, Dietel J. Serous carcinoma of the endometrium with choriocarcinomatous differentiation: a case report and review of the literature indicate the existence of 2 prognostically relevant tumor types. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25(3):247–251. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000215294.45738.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patil S, Ramakrishna KA, Rao SG. et al. Choriocarcinoma - a rare association with squamous cell carcinoma of esophagus. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25(1):42–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis PM, Turner AG. Primary choriocarcinoma of the bladder evolving from a transitional cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37(5):503–505. doi: 10.1136/jcp.37.5.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grammatico D, Grignon DJ, Eberwein P. et al. Transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis with choriocarcinomatous differentiation. Immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic assessment of human chorionic gonadotropin production by transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Cancer. 1993;71(5):1835–1841. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930301)71:5<1835::aid-cncr2820710519>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon JH, Kim MS, Kook EH. et al. Primary gastric choriocarcinoma: two case reports and review of the literatures. Cancer Res Treat. 2008;40(3):145–150. doi: 10.4143/crt.2008.40.3.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbeek W, Schulten HJ, Sperling M. et al. Rectal adenocarcinoma with choriocarcinomatous differentiation: clinical and genetic aspects. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(11):1427–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen F, Tatsumi A, Numoto S. Combined choriocarcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the lung occurring in a man: case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 2001;91(1):123–129. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<123::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erhan Y, Ozdemir N, Zekioglu O. et al. Breast carcinomas with choriocarcinomatous features: case reports and review of the literature. Breast J. 2002;8(4):244–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maesta I, Michelin OC, Traiman P. et al. Primary non-gestational choriocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;98(1):146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwab KE, Chan RW, Gargett CE. Putative stem cell activity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells during the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(Suppl 2):1124–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan RW, Schwab KE, Gargett CE. Clonogenicity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70(6):1738–1750. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubbard SA, Gargett CE. A cancer stem cell origin for human endometrial carcinoma? Reproduction. 2010;140(1):23–32. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutella S, Bonanno G, Procoli A. et al. Cells with characteristics of cancer stem/progenitor cells express the CD133 antigen in human endometrial tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(13):4299–4311. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]