Abstract

Background

Two potential targets for preventing chronic lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in older men are obesity and physical activity.

Objective

To examine associations of adiposity and physical activity with incident LUTS in community-dwelling older men.

Design, setting, and participants

The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS) is a prospective cohort of men ≥65 yr of age. MrOS participants without LUTS and a history of LUTS treatment at baseline were included in this analysis.

Measurements

Adiposity was measured with body mass index (BMI), physical activity with the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) and self-report of daily walking, and LUTS with the American Urological Association Symptom Index.

Results and limitations

The mean age (standard deviation [SD]) of the 1695 participants was 72 (5) yr at baseline. At a mean (SD) follow-up of 4.6 (0.5) yr, 524 (31%) of men reported incident LUTS. In multivariate analyses, compared with men of normal weight at baseline (BMI <25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI: 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2) men were 29% (adjusted odds ratio [ORadj]: 1.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00–1.68) and 41% (ORadj: 1.41; 95% CI, 1.03–1.93) more likely to develop LUTS, respectively. Men in the highest quartile of physical activity were 29% (ORadj: 0.71; 95% CI, 0.53–0.97) and those who walked daily 20% (ORadj: 0.80; 95% CI, 0.65–0.98) less likely than their sedentary peers to develop LUTS, adjusting for BMI. The homogeneous composition of MrOS potentially diminishes the external validity of these results.

Conclusions

In older men, obesity and higher physical activity are associated with increased and decreased risks of incident LUTS, respectively. Prevention of chronic urinary symptoms represents another potential health benefit of exercise in elderly men.

Keywords: LUTS, Epidemiology, BPH, Benign prostatic hyperplasia, Obesity, Exercise, Physical activity, Prostate, IPSS

1. Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) occur among 15–80% of men >40 yr of age [1–4] and exert a substantial, and often underappreciated, negative effect on public health. LUTS are independently associated with increased mortality, an increased risk of falls, a substantially diminished quality of life, and depression [5–7]. The costs associated with diagnosis and treatment exceed $6 billion each year in the United States [1,8].

Relatively little research, however, has focused on prevention. Emerging data intimate that metabolic disturbances, and the lifestyle factors that modulate these disturbances, potentially contribute substantially to LUTS onset and progression. These observations are clinically important because they suggest the existence of modifiable pathways that might provide novel targets for LUTS prevention.

Two modifiable factors possibly involved with LUTS development are obesity and physical activity. Obesity has been associated with increased likelihood; conversely, increased physical activity has been associated with decreased likelihood [9–11]. Observations, however, are inconsistent [12–15]. These data are based predominantly on cross-sectional studies that did not explore the effects of obesity and exercise on the natural history of LUTS onset in asymptomatic men, investigate potential links between these two highly interrelated variables, or include detailed assessments of related metabolic factors that could confound or modify these associations. Longitudinal analyses of obesity and exercise with incident LUTS, incorporating comprehensive evaluation of prevalent demographic and health conditions, would provide valuable insight by identifying at-risk individuals and elucidating behavior-related prevention strategies. Therefore, we examined the associations of adiposity and physical activity with incident LUTS in a large cohort of community-dwelling older men.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and design

The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS) is an institutional review board approved, prospective cohort study of community-dwelling older men designed to identify risk factors for falls, fractures, and other important conditions of aging. The MrOS study protocol includes a prospective collection of extensive information on prostate disease and LUTS [16].

2.2. Demographic, lifestyle, and medical factors

Participants provided information regarding age, race/ethnicity (white, black/African American, Asian, Hispanic, other), education level, marital status, socioeconomic status, self-reported health status, lifestyle measures (cigarette smoking and current alcohol consumption), medical history, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) diagnosed by a doctor or other health care provider, and BPH treatment [16,17].

2.3. Medication and supplement use

Based on the information recorded at the baseline visit, participants were classified as currently using herbal supplements for urinary symptoms if they reported using saw palmetto, South African star grass, stinging nettle, rye grass pollen, pumpkin seed, African plum, or any other herb or supplement. Participants were classified as currently taking prescription urologic medications if they reported use of finasteride or if they had a prescription for 5α-reductase inhibitors (finasteride or dutasteride; dutasteride was included under medications at follow-up but was not available at baseline), α-blockers, or urinary-specific antispasmodics.

2.4. Assessment of urinary symptoms

LUTS were measured at two study time points, baseline and a follow-up visit, using the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI).

2.5. Assessments of adiposity and physical activity

During the baseline study visit, participants were measured for height (centimeters) and weight (kilograms). Body mass index (BMI; kilograms per square meter) was calculated from the height and weight measures and categorized as normal (<25.0 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), or obese (≥30 kg/m2) [18]. Adipose tissue distribution in the whole body and the trunk was obtained with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) [19,20]. Percentage total body fat, percentage trunk fat, and the ratio of total trunk fat to total arm and leg fat were assessed; for the analysis each was scored by quartiles of the sample population.

Physical activity at baseline was self-reported using two assessments. First, participants provided a detailed assessment of their household, leisure, and occupational activities in the past 7 d on the 12-item Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) [21]. Second, participants were asked, “Do you take walks for exercise, daily or almost every day? (yes or no).”

2.6. Insulin and glucose

At the baseline visit, blood was drawn while the subject was in a fasting state. For insulin, we stratified by quartiles. For fasting glucose, we stratified by quartiles and also by the American Diabetic Association guidelines as follows: normal, <100 mg/dl (<5.6 mmol/l); prediabetes, 100–125 mg/dl (5.6–6.9 mmol/l); and diabetes, ≥126 mg/dl (≥7 mmol/l). We combined insulin and glucose measures using the homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), calculated as fasting serum insulin (mU/l) × fasting serum glucose (mmol/l)/22.5. Using this approach, insulin resistance is defined as having a HOMA-IR value ≥3.0 [7,22].

2.7. Analytic cohort and primary outcome

We restricted the analytic cohort to men with an AUA-SI of 0–7 at baseline and who reported no history of any treatment for BPH, no current use of herbal supplements for prostate symptoms, and no current prescription urologic medication. To avoid including symptoms associated with incident prostate cancer, we further excluded adjudicated incident prostate cancer cases occurring between baseline and the second clinic visit.

We defined onset of LUTS as any of the following at the follow-up clinic visit: an AUA-SI ≥8; documented current use of prescription medications including α-adrenergic blockers, urinary antispasmodics, and 5α-reductase inhibitors for urinary symptoms; or self-report of past use of prescription medications or noncancer surgery of the prostate.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were coded into sample quartiles or categorized using previously published cut points. For categorical variables, categories were sometimes combined to have sufficient sample sizes within each group. Baseline variables were tested for univariate association with incident LUTS using the Pearson chi-square test. For the primary variables of interest measuring physical activity levels, body composition (BMI, percentage body fat) and insulin and glucose metabolism, univariate association with incident LUTS was also assessed using the Cochran-Armitage test of trend across increasing categories [23]. Variables significant at the 10% level were carried forward for assessment in the final multivariate logistic regression models. Because PASE score and self-reported walking are two instruments that assess the same underlying construct (level of physical activity), in the final logistic regression models each was included in a separate model. Variables with p values <0.05 were retained in the model. Analyses were performed with SAS statistical software v.9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study population

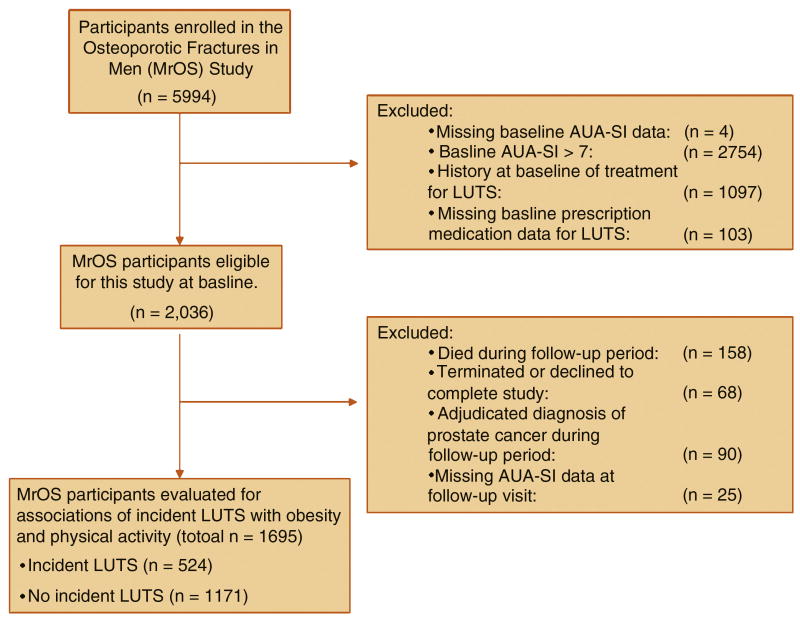

Of the 5994 men enrolled in MrOS, 1695 (28%) reported a baseline AUA-SI <8, did not have a history of LUTS or treatment for LUTS, were not taking urologic medications at baseline, were not diagnosed with prostate cancer during follow-up, and had complete baseline and follow-up visit data (Fig. 1). The baseline mean age (standard deviation [SD]; range) of this analytic cohort was 72 (5; 65–91) yr. Mean (SD; range) follow-up time in the analytic cohort was 4.6 (0.5; 3.7–6.0) yr between baseline and the follow-up clinic visit.

Fig. 1. Study population.

3.2. Demographic, health, and lifestyle characteristics at baseline

At the follow-up clinic visit, 524 (31%) of the participants who were asymptomatic at baseline reported new-onset LUTS (175 treatment with surgery or medications and 349 with an AUA-SI ≥8). These men at baseline older, more likely to report at least one chronic medical condition, had lower PASE scores, and were less likely to walk daily than the men who did not report LUTS onset. There was no association of LUTS onset with race, educational attainment, socioeconomic status, diabetes, smoking status, or level of alcohol consumption (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline demographic characteristics of the study population and onset of lower urinary tract symptoms at the second study visit (mean: 4.6 yr of follow-up).

| No. | Percentage with LUTS (n = 524), % | Percentage without LUTS (n = 1171), % | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 0.02 | |||

| 65–69 | 675 | 29.0 | 71.0 | |

| 70–79 | 852 | 30.5 | 69.5 | |

| ≥80 | 168 | 40.5 | 59.5 | |

| Race | 0.47 | |||

| White | 1502 | 30.6 | 69.4 | |

| Nonwhite | 193 | 33.2 | 66.8 | |

| Education | 0.13 | |||

| High school or less | 398 | 33.9 | 66.1 | |

| Some college or college degree | 706 | 31.6 | 68.4 | |

| Some graduate school or graduate degree | 591 | 28.1 | 71.9 | |

| SES (compared with United States)* | 0.60 | |||

| Below median | 829 | 30.3 | 69.7 | |

| Median and above | 854 | 31.5 | 68.5 | |

| Diabetes | 0.23 | |||

| No diabetes | 1523 | 30.5 | 69.5 | |

| Diabetes | 172 | 34.9 | 65.1 | |

| Chronic medical conditions† | 0.01 | |||

| Reported none | 765 | 27.8 | 72.2 | |

| Reported at least one | 930 | 33.4 | 66.6 | |

| Smoking status** | 0.73 | |||

| Never | 672 | 30.2 | 69.8 | |

| Former | 948 | 31.7 | 68.4 | |

| Current | 74 | 28.4 | 71.6 | |

| Alcohol consumption‡ | 0.82 | |||

| Nondrinker | 549 | 31.7 | 68.3 | |

| Average <1 drink per day | 680 | 30.3 | 69.7 | |

| Average 1 to <2 drinks per day | 242 | 29.3 | 70.7 | |

| Average ≥2 drinks per day | 223 | 32.7 | 67.3 | |

| PASE*** score, quartile | 0.06 | |||

| <111.5 | 423 | 34.8 | 65.1 | |

| 111.5–150.9 | 422 | 29.9 | 70.1 | |

| 151.0–196.6 | 422 | 32.5 | 67.5 | |

| >196.6 | 427 | 26.5 | 73.5 | |

| Walking | 0.02 | |||

| Do not walk daily for exercise | 839 | 33.6 | 66.4 | |

| Walk daily for exercise | 856 | 28.3 | 71.7 |

LUTS = lower urinary tract symptoms; SES = socioeconomic status; PASE = Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.

Self-reported; 12 with missing data.

Dizziness, diabetes, heart attack, stroke, or high blood pressure.

One with missing data.

One with missing data.

PASE; one with missing data.

3.3. Metabolic characteristics

Men who reported incident LUTS had higher BMI than those who did not (Cochran-Armitage test for trend; p = 0.02). There were no associations of LUTS onset with body fat distribution as measured by DXA scanning or multiple measures of glucose homeostasis including fasting glucose, fasting insulin, or HOMA-IR (Table 2).

Table 2. Baseline metabolic characteristics of the study population and onset of lower urinary tract symptoms at the second study visit (mean: 4.6 yr of follow-up).

| No. | Percentage with LUTS (n = 524), % | Percentage without LUTS (n = 1171), % | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.06 | |||

| <25 | 439 | 26.7 | 73.3 | |

| 25–29.9 | 884 | 31.7 | 68.3 | |

| ≥30 | 372 | 34.1 | 65.9 | |

| Percentage total body fat, quartile | 0.11 | |||

| <22.7 | 421 | 31.1 | 68.9 | |

| 22.7–26.2 | 422 | 26.8 | 73.2 | |

| 26.3–29.9 | 421 | 33.7 | 66.3 | |

| >29.9 | 422 | 31.5 | 68.5 | |

| Missing | 9 | 55.6 | 44.4 | |

| Percentage trunk fat, quartile | ||||

| <24.8 | 421 | 31.4 | 68.6 | 0.17 |

| 24.8–29.1 | 422 | 27.3 | 72.7 | |

| 29.2–33.3 | 421 | 33.3 | 66.7 | |

| >33.3 | 422 | 31.3 | 68.7 | |

| Missing | 9 | 55.6 | 44.4 | |

| Fasting glucose, quartile, mg/dl | 0.31 | |||

| <93 | 355 | 31.3 | 68.7 | |

| 93–99 | 390 | 28.2 | 71.8 | |

| 100–109 | 389 | 30.9 | 69.2 | |

| >109 | 408 | 34.6 | 65.4 | |

| Missing | 153 | 27.5 | 72.5 | |

| Fasting glucose, cut points, mg/dl | 0.44 | |||

| Normal | 745 | 29.7 | 70.3 | |

| Prediabetic | 617 | 32.9 | 67.1 | |

| Diabetic | 180 | 32.2 | 67.8 | |

| Missing | 153 | 27.5 | 72.5 | |

| Fasting insulin, quartile, μIU/ml | 0.72 | |||

| <5.56 | 385 | 32.7 | 67.3 | |

| 5.6–8.2 | 385 | 30.4 | 69.6 | |

| 8.3–12.1 | 385 | 32.2 | 67.8 | |

| >12.1 | 387 | 29.7 | 70.3 | |

| Missing | 153 | 27.5 | 72.5 | |

| HOMA-IR, quartile | 0.85 | |||

| <1.34 | 385 | 31.9 | 68.1 | |

| 1.34–2.06 | 386 | 32.1 | 67.9 | |

| 2.07–3.25 | 385 | 30.6 | 69.4 | |

| >3.26 | 386 | 30.3 | 69.7 | |

| Missing | 153 | 27.5 | 72.5 | |

| HOMA-IR, cut points | 0.42 | |||

| Normal (<3) | 1093 | 31.9 | 68.1 | |

| Insulin resistant (≥3) | 449 | 29.6 | 70.4 | |

| Missing | 153 | 27.5 | 72.5 |

LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; BMI = body mass index; HOMA-IR = Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance.

3.4. Multivariate models of body mass index, Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly score, and walking

The baseline measures indicating study site, age, presence of at least one medical condition, BMI, PASE, and self-reported walking were carried forward to the multivariate logistic regression models. In addition, because of significant differences between sites in educational levels, we retained educational level in the final models. Because PASE score and self-reported walking are two instruments that assess the same underlying construct (level of physical activity), we included each in a separate model (Table 3). Whether using PASE score or self-reported daily walking, overweight and obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) participants were significantly more likely to report LUTS onset than normal (BMI <25 kg/m2) participants (Table 3). Compared with those in the lowest quartile, participants in the highest quartile of physical activity as measured by PASE score were 29% less likely to report LUTS onset. Similarly, those who walked were 20% less likely to report LUTS symptoms compared with those who did not walk.

Table 3. Multivariable-adjusted odds ratios for lower urinary tract symptoms progression by physical activity as measured by the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly score and daily walking.

| Model 1: Physical activity | Model 2: Walking | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |||

| Age, yr | |||||||||

| 65–69 | Ref | – | – | – | Ref | – | – | – | |

| 70–79 | 1.03 | 0.82 | 1.29 | 0.80 | 1.05 | 0.84 | 1.31 | 0.68 | |

| ≥80 | 1.53 | 1.06 | 2.21 | 0.02 | 1.65 | 1.15 | 2.38 | 0.007 | |

| Education | |||||||||

| High school or less | Ref | – | – | – | Ref | – | – | – | |

| Some college or college degree | 0.98 | 0.74 | 1.29 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 1.31 | 0.96 | |

| Some graduate school or graduate degree | 0.86 | 0.64 | 1.16 | 0.33 | 0.87 | 0.65 | 1.18 | 0.38 | |

| Chronic medical conditions† | |||||||||

| No medical condition | Ref | – | – | – | Ref | – | – | – | |

| Any medical condition | 1.20 | 0.97 | 1.49 | 0.09 | 1.22 | 0.98 | 1.51 | 0.07 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||||||||

| <25 | Ref | – | – | – | Ref | – | – | – | |

| 25–29.9 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 1.68 | 0.05 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 1.68 | 0.05 | |

| >30 | 1.41 | 1.03 | 1.93 | 0.03 | 1.40 | 1.02 | 1.91 | 0.04 | |

| PASE score | |||||||||

| <111.5 | Ref | – | – | – | – | ||||

| 111.5–150.9 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 1.08 | 0.15 | – | – | – | – | |

| 151.0–196.6 | 0.95 | 0.71 | 1.27 | 0.72 | – | – | – | – | |

| >196.6 | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.97 | 0.03 | – | – | – | – | |

| Walking | |||||||||

| No daily walking | – | – | – | – | Ref | – | – | – | |

| Daily walking | – | – | – | – | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.98 | 0.03 | |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; BMI = body mass index; PASE = Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.

Models are controlled for study site in addition to all the variables listed in the body of the table.

Including diabetes, heart attack, stroke, high blood pressure, or trouble with dizziness.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to investigate the associations of obesity and physical activity with incident urinary symptoms in a cohort of community-dwelling elderly men. In this cohort, compared with men of normal BMI, men who were overweight or obese had 29% (ORadj: 1.29) and 41% (ORadj: 1.41) higher odds, respectively, of developing LUTS over the approximate 5-yr study period. In contrast, compared with men in the lowest quartile of physical activity as assessed by PASE score, men in the highest quartile were 29% less likely to develop LUTS (ORadj: 0.71). The apparent protective association with increased physical activity remained significant in a model adjusted for BMI, suggesting that increased physical activity may have significantly diminished the probability of symptom onset even among overweight and obese men. Additionally, those who walked daily for exercise were 20% less likely to report LUTS compared with those who did not walk daily (ORadj: 0.80).

Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that excess body weight may promote and exercise may protect against the onset of LUTS in older men. LUTS prevention thus represents another potential health benefit of exercise in elderly men. Because more than one in three men in the entire cohort developed LUTS within 5 yr, our data represent substantial, clinically relevant variations in risk with potentially important applications to medical practice.

These data are consistent with prior studies of LUTS, obesity, and physical activity. In prior cross-sectional analyses, obesity was associated with increased prevalence of LUTS [7,9] and related outcomes including BPH surgery [7,9] and prostate enlargement [11]. In the only previous prospective study, obese men (as determined by BMI at study entry) were up to 30% more likely to be diagnosed subsequently with BPH [14]. Conversely, exercise and increased physical activity have been linked, in many of the same study populations, with a decreased likelihood of LUTS [24]. A meta-analysis of eight cross-sectional studies indicated that moderate to vigorous physical activity reduced the prevalence of BPH or LUTS by up to 25% relative to a sedentary lifestyle [25]. The one prospective analysis of exercise observed no associations with incident BPH [14]. Other, smaller studies have noted equivocal [26] or null cross-sectional associations of obesity with LUTS and related outcomes. It is possible that the same potential mechanisms by which obesity increases LUTS risk, including inflammatory pathways and alterations in endogenous sex steroid hormone levels, may be counterbalanced by exercise [25].

A preponderance of the existing literature supports a positive association of LUTS-related outcomes with prevalent diabetes and blood markers of disruptions in glucose homeostasis, including elevated fasting glucose, elevated insulin, and HOMA [27]. We did not observe a higher risk of incident LUTS with any of these variables.

LUTS affect millions of older men and generate substantial medical and economic costs. Both the prevalence and incidence of LUTS and BPH in the United States are steadily increasing (http://www.UDAonline.net) [28]. Prior clinical research has focused almost exclusively on treatment with surgery or medication. Walking once daily is simple, straightforward, and beneficial to global health. Indeed, walking is the most common form of exercise among older adults [29]. Thus, in counseling older men about the favorable outcomes of walking and other forms of physical exercise, clinicians should consider including LUTS prevention as part of the discussion. Our study has several strengths that distinguish it from prior investigations. First, it explored the natural history of urinary symptom onset in initially asymptomatic men. Second, it examined effects of adiposity and physical activity in the same analytical models. Third, it incorporated a comprehensive array of demographic and metabolic variables not included in previous analyses. DXA scanning allowed us to examine the association of adipose tissue distribution, particularly in the abdomen, with LUTS, a novel and important study characteristic, given the biologic relation of adipose tissue distribution to insulin and glucose [30]. Finally, our study is the first to use the PASE questionnaire to assess quantitatively the effect of physical activity on urinary symptoms. The merit of the validated PASE instrument is that it assesses the types of activities commonly engaged in by elderly adults [21].

A potential limitation of this analysis is that the homogeneous composition of MrOS—predominantly healthy, white, well-educated volunteers–potentially diminishes the external validity of the results. Another possible limitation is the absence of urinary bother, storage, and voiding symptom analyses. Finally, our models were not able to take into account the following variables that may potentially affect LUTS: sexual health, hormones, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor and diuretic therapy, incident neurologic disease, renal function, sleep apnea, fluid intake, prostate volume measures, prostate-specific antigen, or urodynamics.

5. Conclusions

In older men, modest amounts of physical activity and walking appear to be associated with a reduction in the 5-yr incidence of LUTS. Although randomized trials may be needed to establish definitively the efficacy of exercise and other forms of increased physical activity for LUTS prevention and control, there are no drawbacks to discussing the potential urinary health benefits of exercise with older male patients. Given the high prevalence of LUTS among older men, exercise has the potential to substantially reduce the burden of urinary disease in older men.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study is supported by the National Institutes of Health. The following institutes provide support: the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research under the following grant numbers: U01 AR45580, U01 AR45614, U01 AR45632, U01 AR45647, U01 AR45654, U01 AR45583, U01 AG18197, U01-AG027810, and UL1 RR024140. Funding was also provided by the Urologic Diseases of America Project (N01-DK-7-0003) and NIDDK R21DK083675. NIAMS, NIA, NCRR, and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research provided support for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, and interpretation of the data; and approval of the manuscript. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases provided support for the design and statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J. Kellogg Parsons had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Parsons, Marshall.

Acquisition of data: Marshall.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Parsons, Marshall, White, Messer.

Drafting of the manuscript: Parsons.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Messer, Barrett-Connor, Bauer, Marshall.

Statistical analysis: Messer, White, Marshall.

Obtaining funding: Parsons, Marshall.

Administrative, technical, or material support: White.

Supervision: None.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: I certify that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wei JT, Calhoun E, Jacobsen SJ. Urologic diseases in America project: benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2005;173:1256–61. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000155709.37840.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen R, Altwein J, Boyle P, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms and male sexual dysfunction: the multinational survey of the aging male (MSAM-7) Eur Urol. 2003;44:637–49. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kupelian V, Wei JT, O'Leary MP, et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and effect on quality of life in a racially and ethnically diverse random sample: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2381–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parsons JK, Bergstrom J, Silberstein J, Barrett-Connor E. Prevalence and characteristics of lower urinary tract symptoms in men aged > or = 80 years. Urology. 2008;72:318–21. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engstrom G, Henningsohn L, Walker-Engstrom ML, Leppert J. Impact on quality of life of different lower urinary tract symptoms in men measured by means of the SF 36 questionnaire. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006;40:485–94. doi: 10.1080/00365590600830862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons JK, Mougey J, Lambert L, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms increase the risk of falls in older men. BJU Int. 2009;104:63–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupelian V, Fitzgerald MP, Kaplan SA, Norgaard JP, Chiu GR, Rosen RC. Association of nocturia and mortality: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2011;185:571–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saigal CS, Joyce G. Economic costs of benign prostatic hyperplasia in the private sector. J Urol. 2005;173:1309–13. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152318.79184.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Chute CG, et al. Obesity and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:989–1002. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seim A, Hoyo C, Ostbye T, Vatten L. The prevalence and correlates of urinary tract symptoms in Norwegian men: the HUNT study. BJU Int. 2005;96:88–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons JK, Carter HB, Partin AW, et al. Metabolic factors associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2562–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke JP, Rhodes T, Jacobson DJ, et al. Association of anthropometric measures with the presence and progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:41–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritschi L, Tabrizi J, Leavy J, Ambrosini G, Timperio A. Risk factors for surgically treated benign prostatic hyperplasia in Western Australia. Public Health. 2007;121:781–9. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristal AR, Arnold KB, Schenk JM, et al. Race/ethnicity, obesity, health related behaviors and the risk of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. J Urol. 2007;177:1395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.065. quiz 1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsons JK, Sarma AV, McVary K, Wei JT. Obesity and benign prostatic hyperplasia: clinical connections, emerging etiological paradigms and future directions. J Urol. 2009;182(Suppl):S27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orwoll E, Blank JB, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study—a large observational study of the determinants of fracture in older men. Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26:569–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor BC, Wilt TJ, Fink HA, et al. Prevalence, severity, and health correlates of lower urinary tract symptoms among older men: the MrOS study. Urology. 2006;68:804–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991–1998. JAMA. 1999;282:1519–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Visser M, Fuerst T, Lang T, Salamone L, Harris TB. Validity of fan-beam dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for measuring fat-free mass and leg muscle mass. Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study—Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry and Body Composition Working Group. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1513–20. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.4.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salamone LM, Fuerst T, Visser M, et al. Measurement of fat mass using DEXA: a validation study in elderly adults. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:345–52. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–62. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stern SE, Williams K, Ferrannini E, DeFronzo RA, Bogardus C, Stern MP. Identification of individuals with insulin resistance using routine clinical measurements. Diabetes. 2005;54:333–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsons JK. Lifestyle factors, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and lower urinary tract symptoms. Current Opin Urol. 2011;21:1–4. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32834100c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsons JK, Kashefi C. Physical activity, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol. 2008;53:1228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zucchetto A, Tavani A, Dal Maso L, et al. History of weight and obesity through life and risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:798–803. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarma AV, Parsons JK, McVary K, Wei JT. Diabetes and benign prostatic hyperplasia/lower urinary tract symptoms—what do we know? J Urol. 2009;182(Suppl):S32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroup SP, Palazzi-Churas K, Kopp RP, Parsons JK. U.S. trends in hospitalizations for benign prostatic hyperplasia, 1998—2008. BJU Int. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10250.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eyler AA, Brownson RC, Bacak SJ, Housemann RA. The epidemiology of walking for physical activity in the United States. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1529–36. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000084622.39122.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grundy SM. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2595–600. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]