Abstract

The protein PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) is a key regulator of low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) levels and cardiovascular health. We have determined the crystal structure of LDLR bound to PCSK9 at neutral pH. The structure shows LDLR in a new extended conformation. The PCSK9 C-terminal domain is solvent exposed, enabling cofactor binding, whereas the catalytic domain and prodomain interact with LDLR epidermal growth factor(A) and β-propeller domains, respectively. Thus, PCSK9 seems to hold LDLR in an extended conformation and to interfere with conformational rearrangements required for LDLR recycling.

Keywords: PCSK9, LDL, receptor, hypercholesterolaemia, structure

Introduction

High levels of circulating low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol are linked to cardiovascular disease (NCEP-Panel, 2002), the leading cause of death worldwide. The LDL receptor (LDLR) has emerged as a key regulator of cellular LDL uptake and plasma cholesterol levels. The LDLR binds to circulating LDL, and the complex is internalized by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. At low pH in the endosomes, the LDLR/LDL complex dissociates allowing receptor recycling and lysosomal degradation of LDL (Brown & Goldstein, 1986). Interestingly, LDLR mutations blocking LDL release prevent receptor recycling, leading to LDLR degradation (Davis et al, 1987). The importance of the LDLR for human health is highlighted by the many (>1,000) LDLR missense mutations that are associated with familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH; Leigh et al, 2008).

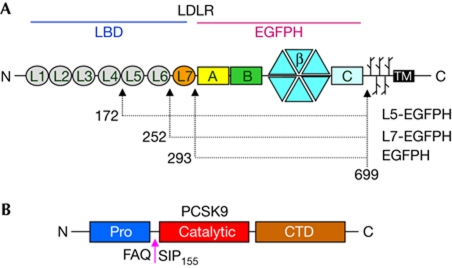

The LDLR ectodomain has two main regions: the ligand-binding domain (LBD, with repeats L1–L7, each of about 40 residues) and the epidermal growth factor (EGF) precursor homology domain (EGFPH, with EGF(A), EGF(B), β-propeller and EGF(C) domains; Fig 1). The EGFPH region is required for acid-dependent ligand release (Davis et al, 1987; Beglova et al, 2004) and contributes to LDL binding together with the LBD (Esser et al, 1988; Russell et al, 1989; Huang et al, 2010; Ren et al, 2010).

Figure 1.

Domain organizations of LDLR and PCSK9. (A) The low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) ectodomain has seven repeats (L1–L7) in the ligand-binding domain (LBD), each comprising about 40 residues and each stabilized by three disulphide bonds and one Ca2+ ion; an epidermal growth factor precursor homology domain; and O-linked sugar regions. (B) Mature proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) is formed after auto-cleavage at the site indicated. CTD, C-terminal histidine-rich domain.

Many studies have been conducted on the LDLR to understand the mechanism of pH-dependent LDL release. A low-resolution cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) study of vesicle-reconstituted LDLR at neutral pH showed predominantly elongated stick-like structures (Jeon & Shipley, 2000), whereas a crystal structure of the LDLR determined at acidic pH showed the receptor in a closed conformation, with intramolecular contacts between repeats L4–L5 of the LBD and the β-propeller (Rudenko et al, 2002). Formation of these interactions at low pH in the endosomes is proposed to drive LDL dissociation, either through direct competition or allosterically (Rudenko et al, 2002; Zhao & Michaely, 2008). In addition, decreased Ca2+-binding affinity of the L5 repeat has been observed at low pH (Arias-Moreno et al, 2008), which might also contribute to LDLR/LDL complex disassembly through local unfolding of the receptor. Despite several studies supporting various aspects of these models and the identification of various amino acids that contribute to LDL release (Zhang et al, 2008; Zhao & Michaely, 2008; Huang et al, 2010), the molecular and structural determinants for the pH-driven conformational change of the receptor remain only partly characterized.

An important contribution to the regulation of hepatic LDLR and consequently of plasma LDL levels was made by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9; Abifadel et al, 2009). The association of PCSK9 with cardiovascular disease was made after the discovery of PCSK9 mutations linked with hyper- or hypocholesterolaemia. For instance, remarkable degrees of protection against coronary heart disease were observed in humans with the single PCSK9 point mutations Y142X, C679X and R46L (Cohen et al, 2006). Moreover, a perfectly healthy compound heterozygote (Y142X and ΔR97) was identified with extremely low levels of plasma LDL and no detectable circulating PCSK9 (Zhao et al, 2006).

PCSK9 has a prodomain, a catalytic domain and a C-terminal histidine-rich domain (CTD; Fig 1). After auto-cleavage, the prodomain remains tightly associated with the catalytic domain. PCSK9 reduces LDLR levels not through proteolytic activity but rather by binding and targeting the receptor for lysosomal degradation (Horton et al, 2009). The neutral-pH structure of the complex between PCSK9 and a small LDLR EGF(A)–EGF(B) fragment showed how EGF(A) contacts only the PCSK9 catalytic domain. The same complex at low pH showed that the EGF(A) H306 side chain forms an extra salt bridge with PCSK9 D374, thus increasing binding affinity three- to fourfold (Kwon et al, 2008; Bottomley et al, 2009). Although at present it is unclear how the PCSK9/LDLR interaction leads to receptor degradation, PCSK9 loss-of-function mutations result in increased LDLR levels and hypocholesterolaemia, whereas PCSK9 gain-of-function mutations are associated with increased LDLR degradation and hypercholesterolaemia (Abifadel et al, 2009).

Results And Discussion

We crystallized various complexes of full-length PCSK9 and LDLR ectodomain proteins (supplementary information online). The complex of PCSK9 and the LDLR EGFPH fragment yielded crystals at neutral pH and allowed structure determination and refinement to 3.3 Å resolution (Rw=27.0%, Rf=29.9%; supplementary Table S1 online and supplementary Fig S1 online). A second structure of PCSK9 bound to the entire LDLR ectodomain was refined to 4.2 Å resolution but showed PCSK9 bound only to the L7-EGFPH region of the receptor (supplementary Table S1 online). Mass spectrometry, SDS–PAGE analysis and N-terminal sequencing of washed crystals indicated that adventitious proteolysis of the LDLR had occurred during crystallization between repeats L4 and L5 (G171↓D172), for about 50% of receptor molecules, such that the crystals contained a mixture of full-length receptor and a shorter form lacking L1 to L4. Thus, the L6 and L5, and presumably also L1 to L4, are probably flexible in the crystals. Purification and crystallization in the presence of protease inhibitors was sufficient to prevent receptor degradation, but the resulting crystals did not show improved diffraction. Although the structures of PCSK9 bound to the full-length LDLR or the shorter construct (L7-EGFPH) were determined from crystals obtained under different conditions and with completely different crystal packing arrangements, the resulting PCSK9/LDLR structures were essentially identical.

The most striking feature of the complex was that the LDLR showed an extended conformation, with the L7-EGF(A)–EGF(B) region appearing as a stick-like protrusion from the β-propeller (Fig 2), with dimensions remarkably similar to those of lipid-reconstituted LDLR observed at neutral pH by cryoEM (Jeon & Shipley, 2000) and contrasting with the closed ring-like structure observed at low pH (Rudenko et al, 2002). Conversely, PCSK9 adopted the same structure previously seen at various pHs (Cunningham et al, 2007; Hampton et al, 2007; Piper et al, 2007).

Figure 2.

Structure of the PCSK9/LDLR complex. Colour scheme: PCSK9 prodomain (Pro, blue), catalytic (Cat, red) and C-terminal (CTD, brown) domains; LDLR domains are L7 (beige), EGF(A) (yellow), EGF(B) (green) and β-propeller/EGF(C) (cyan). Spheres indicate Ca2+ ions. PCSK9 residues 212–222 form a disordered loop (red dashes) harbouring the furin cleavage site (RFHR218). Box: details of the β-propeller/prodomain interface; side-chain sticks for S127, D129, R385, N404 and N407 show the close proximity of residues associated with familial hypercholesterolaemia; side-chain labels are colour coded: PCSK9, red; LDLR, grey. CTD, C-terminal histidine-rich domain; EGF, epidermal growth factor; LDLR, low-density lipoprotein receptor; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Most of the contacts between PCSK9 and LDLR occurred between the PCSK9 catalytic domain and the LDLR EGF(A) domain, resulting in a roughly 1,000 Å2 interface, as described in previous reports of the PCSK9/EGF(A)–EGF(B) structure (Kwon et al, 2008; Bottomley et al, 2009). In addition, the PCSK9 prodomain made van der Waals contacts with the LDLR β-propeller, creating a second, albeit minor, interface of about 70 Å2 involving L626 (LDLR β-propeller) and L108 (PCSK9 prodomain; Fig 2). Notably, the PCSK9 S127R gain-of-function mutation (Abifadel et al, 2009) maps to this region (Fig 2), suggesting that extra contacts with the β-propeller might underlie this phenotype.

The structure of the PCSK9/LDLR complex also showed a well-ordered EGF(B), in contrast to previous structures of an LDLR EGF(B)–β-propeller–EGF(C) fragment (Jeon et al, 2001) and PCSK9/EGF(A)–EGF(B) complexes in which this domain was disordered (Kwon et al, 2008; Bottomley et al, 2009). In the position observed here, the EGF(B) domain is expected to prevent access of furin protease to the RFHR218 target site within the PCSK9 catalytic domain (Benjannet et al, 2006; Essalmani et al, 2011; Fig 2). Indeed, we observed that furin cleavage activity on PCSK9 in solution is prevented by LDLR (supplementary Fig S2 online). Finally, the structure showed that the PCSK9 CTD does not contact the LDLR and is solvent exposed, consistent both with studies showing that CTD deletion does not affect PCSK9/LDLR binding at neutral pH (Bottomley et al, 2009) and with its proposed role in binding to a cell surface co-receptor (Hampton et al, 2007; Ni et al, 2010).

The extended conformation of the LDLR reported here differs greatly from the closed structure seen at acidic pH (Fig 3A,B). In particular, superposition of the β-propeller–EGF(C) region from the PCSK9/LDLR complex and the low-pH LDLR structure (Rudenko et al, 2002) shows the EGF(B) domain in two entirely different positions (Fig 3C). The difference between the closed and extended receptor conformations is essentially a rotation around residue S376, a hinge in the short linker (A373VGSIA378) connecting EGF(B) to the β-propeller (Fig 3C). In the complex, the linker establishes several intramolecular hydrogen bonds with EGF(B) and β-propeller. Notably, linker residue G375 formed a hydrogen bond with β-propeller residue H635, which functions as a ‘staple’ and therefore contributes to the structure and positioning of the linker (Fig 3D; supplementary Fig S1 online). Moreover, a hydrophobic patch on the β-propeller that is exposed at low pH becomes buried by EGF(B) residues in the complex, further stabilizing the extended receptor conformation (Fig 3D).

Figure 3.

Conformational differences in LDLR at neutral versus acidic pH. (A) A surface display of the neutral-pH PCSK9/LDLR structure (modelled L2–L6 repeats are added in white); arrows indicate flexibility. (B) Low-pH LDLR structure (Rudenko et al, 2002) redrawn from PDB entry 1N7D with the β-propeller–EGF(C) region oriented as in (A). This structure showed that at low pH LDLR is held in a closed conformation by contacts between the β-propeller and the L4–L5 repeats. (C) A structural superposition of the LDLRs (showing only the EGF(B) to EGF(C) regions) from the neutral-pH LDLR/PCSK9 structure (this work) and the low-pH LDLR structure (Rudenko et al, 2002), prepared by alignment of the β-propeller/EGF(C) region. The superposed β-propeller/EGF(C) regions are shown as a surface representation. The EGF(B) domain from the neutral-pH LDLR structure is shown as a green ribbon and the region that it contacts on the β-propeller surface is shown as a green patch. In contrast, the EGF(B) domain from the low-pH LDLR structure is shown as a light blue ribbon, and the region that it contacts on the β-propeller surface is shown as a blue patch. The β-propeller H635 is shown in red. (D) The neutral-pH LDLR structure shows several interdomain bonds between EGF(B) (light green), the linker (dark green) and the β-propeller (surface plot). The β-propeller surface is pink where LDLR mutations are linked with FH; for example, T392M, L393R, D394H/G, E397K, V415A, L435H, H635N/Q. Additional proximal FH-associated mutations map to EGF(B) and linker regions (L364R, C371R, K372N, G375S, S376T, A378T/D). CTD, C-terminal histidine-rich domain; EGF, epidermal growth factor; FH, familial hypercholesterolaemia; LDLR, low-density lipoprotein receptor; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Another difference between the closed and extended LDLR conformations was that the β-propeller surface buried by L4–L5 at acidic pH is exposed in the complex with PCSK9, wherein L4 and L5 are too far away to establish the same interactions observed at acidic pH (compare Fig 3A,B). Thus, by holding the receptor in the extended conformation, PCSK9 interferes with the formation of intramolecular interactions between L4–L5 and the β-propeller. It has recently been proposed that the PCSK9 CTD interacts with the LDLR LBD as a secondary step enhancing complex formation at acidic pH on transport to the endosomes (Yamamoto et al, 2011). Molecular modelling performed in light of the structure of the PCSK9/LDLR complex reported here showed that such contacts could form after a simple rotation of the L1–L6 region pivoting in the flexible loop connecting L6 and L7. The rather elongated L2–L6 region spans about 100 Å (Rudenko et al, 2002), more than sufficient to reach from L7 to the PCSK9 CTD, a distance of only about 80 Å in the structure of the complex (Fig 2).

We used surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to show that at neutral pH PCSK9 bound to the LDLR ectodomain or L7-EGFPH with a high nanomolar dissociation constant (Kd=750 nM for ectodomain, 880 nM for L7-EGFPH), confirming that repeats L1–L6 are not critical for the initial interaction occurring at the cell surface (Table 1; supplementary methods online and supplementary Fig S3 online). The Kd values determined herein are similar to those that we (Fisher et al, 2007) and others (Piper et al, 2007) have previously reported (Kd=625 and 840 nM, respectively), but are somewhat greater than those reported by Cunningham et al (2007) (Kd=170 nM), a variation that can be attributed to the differences in running buffers—we and Piper et al (2007) included small amounts of BSA and detergent to reduce nonspecific interactions.

Table 1. Binding data from surface plasmon resonance experiments at neutral and acidic pH.

| Ligand* | Kd (nM) at pH 7.5 | Kd (nM) at pH 5.5 |

|---|---|---|

| FL LDLR | 750±80 | 8±1 (10±1†) |

| FL LDLR Leu-626-Ala | 1,020±140 | ND |

| FL LDLR Leu-626-Arg | 970±110 | ND |

| FL LDLR Leu-626-Glu | 1,250±140 | 15±1† |

| FL LDLR His-635-Asn | 2,960±595 | 45±8 |

| L7-EGFPH | 880±140 | 20±1 |

| L7-EGFPH§ | 820±90 | 100±10 |

| L7-EGFPH (GS-PP) | 1,940±300 | 28±5 |

| *Adopting the conventional notation, ‘ligand’ refers to the protein immobilized on the sensor chip. †These values were determined by kinetic analysis; all other values were determined by steady-state analysis (see supplementary methods online for details). §The analyte injected in all cases was full-length PCSK9, except for this penultimate row, where the analyte was PCSK9ΔC (that is, PCSK9 lacking the C-terminal histidine-rich domain). | ||

| EGFPH, epidermal growth factor precursor homology domain; LDLR, low-density lipoprotein receptor; ND, not determined; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9. | ||

To evaluate the contribution of the newly observed interface (involving L626 (β-propeller) and L108 (PCSK9)) to the overall affinity of the PCSK9/LDLR interaction, we tested binding of the LDLR mutants L626A/R/E to PCSK9 (supplementary Figs S3 and S4 online). Compared with the wild type, the L626 mutants showed only slightly reduced affinities for PCSK9 (Kd=970–1,250 nM; see Table 1), suggesting that the newly identified interface makes a marginal contribution to the interaction. Nevertheless, by bridging between the LDLR EGF(A) domain and the β-propeller, PCSK9 seems to stabilize the receptor in the extended conformation.

We also used SPR to evaluate mutations that might interfere with the formation of the extended conformation of the receptor and potentially with the formation of the interface between EGF(B) and β-propeller (Fig 3; supplementary Fig S1 online). We observed that the LDLR mutations Gly375Ser376 → Pro-Pro and His635 → Asn resulted in two- to fourfold weaker binding of PCSK9 at neutral pH (Kd=1,940 and 2,960 nM, respectively; see Table 1). The weaker binding of these mutants points to a role of the EGF(B)–β-propeller linker in the optimal binding and relative positioning of PCSK9 and LDLR in the complex.

Interestingly, the EGF(B)/β-propeller interface features an hydrogen bond between H635 and G375 (Fig 3; supplementary Fig S1 online). The G375S and H635Q/N mutations are associated with FH, suggesting that these and other proximal FH mutations (Fig 3) might function by interfering with the transition of the receptor from an extended conformation to a closed conformation, ultimately inhibiting LDL release and receptor recycling. Notably, G375 and H635 are strictly conserved in close members of the LDLR family, including VLDLR and ApoER2, suggesting a conserved function in this receptor family.

The interaction between PCSK9 and LDLR (wild type and mutants) was also assessed by SPR at acidic pH. In agreement with previous reports (Cunningham et al, 2007; Fisher et al, 2007; Piper et al, 2007), at low pH, the binding affinity was enhanced 50- to 100-fold (Kd=8 nM for LDLR wild type; see Table 1). Moreover, at acidic pH, PCSK9 bound to wild-type LDLR and most of the mutant receptors with similar affinities (10–20 nM, see Table 1). A slightly decreased binding to PCSK9 was observed for the LDLR H635N protein (Kd=45 nM, compared with 8–10 nM for wild-type LDLR; Table 1), possibly due to a minor shift in the equilibrium towards the extended LDLR conformation. Finally, we tested a form of PCSK9 lacking the histidine-rich CTD for binding to the L7-EGFPH and observed a further 5- to 10-fold decrease in binding affinity (Kd=100 nM), probably due to the absence of the many CTD histidines, the protonation of which at low pH might enhance electrostatic attractions in the complex. Thus several factors, including the CTD, contribute to the increased LDLR/PCSK9-binding affinity at low pH.

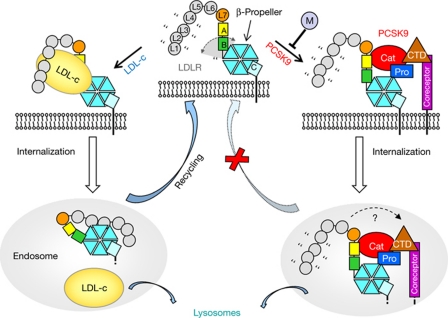

Together, these data indicate a plausible mechanism for LDLR downregulation by PCSK9 (Fig 4). We propose that at neutral pH plasma PCSK9 binds to cell surface LDLR and holds the receptor L7-EGFPH region in an extended conformation. Although the equilibrium dissociation constant of this interaction (Kd ∼750 nM) is relatively low compared with typical amounts of circulating PCSK9 (1–10 nM; Lagace et al, 2006), the half-life of the complex dictated by the dissociation rate constant (koff=1.2 × 10−3 s−1) is about 10 min, which is comparable with the duration of a ‘round trip’ of LDLR internalization and recycling to the cell surface (Goldstein et al, 1976). Moreover, the interaction avidity might be modulated by a cofactor binding to the PCSK9 CTD (Nassoury et al, 2007; Mayer et al, 2008; Ni et al, 2010; Mousavi et al, 2011). Once in the endosomal low-pH milieu, the increased affinity of the PCSK9/LDLR interaction reduces complex dissociation (Fisher et al, 2007; Piper et al, 2007), and more contacts might form between the LDLR LBD and the PCSK9 CTD (Yamamoto et al, 2011). More importantly, by simultaneously contacting EGF(A) and β-propeller domains, and possibly a cell surface co-receptor, PCSK9 constrains the LDLR structure and interferes with the rearrangement of EGF(B) required for the receptor to adopt the low-pH conformation. A role for PCSK9 in preventing the acid-dependent structural transition is also supported by size-exclusion chromatography data (Zhang et al, 2008). Mutations that prevent LDLR/LDL from dissociating at low pH also preclude receptor recycling and lead to degradation (Davis et al, 1987). We postulate that PCSK9 might function similarly, by locking the LDLR in an extended conformation and inhibiting the transition to the closed conformation, and perhaps also by preventing binding to more proteins involved in LDLR recycling (Zhang et al, 2008).

Figure 4.

Proposed mechanism for PCSK9-mediated LDLR downregulation. Top centre and left: on the cell surface at neutral pH, the LDLR L7–EGFPH region can adopt an open extended form and binds to LDL predominantly via LBD repeats (small grey circles). Quotation marks and the arrowed grey arch indicate flexibility. Bottom left: at low endosomal pH, LDLR adopts the closed form, accompanied by LDL release and receptor recycling. Top centre and right: circulating PCSK9 binds to LDLR and restrains flexibility at the EGF(B)/β-propeller interface. Additional co-receptor(s) or PCSK9 modulator(s) (‘M’) might promote or inhibit the interaction. Bottom right: the low pH of the endosomes enhances PCSK9/LDLR affinity, preventing complex dissociation and conformational changes associated with recycling, ultimately leading to lysosomal LDLR degradation. A possible movement of the LDLR LBD and formation of contacts with the PCSK9 CTD at endosomal pH are indicated by the dashed arrow. CTD, C-terminal histidine-rich domain; EGFPH, epidermal growth factor precursor homology domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDLR, low-density lipoprotein receptor; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Finally, the structure indicates new strategies for PCSK9 inhibition as an approach for treating hypercholesterolaemia; for example, prodomain-binding antibodies that sterically interfere with the PCSK9/LDLR interaction. Similarly, small molecules binding the prodomain and disrupting contacts with the β-propeller might partly inhibit PCSK9. Along these lines, a short prodomain peptide (including L108, which we observed in contact with LDLR) was reported to inhibit PCSK9-mediated LDLR lowering (Palmer-Smith & Basak, 2010).

In summary, our structure shows the molecular basis of the interaction between PCSK9 and LDLR at the cell surface and provides a new structural framework to facilitate the search for inhibitors of PCSK9 activity.

Methods

Protein production. Molecular cloning, protein expression and protein purification of the human PCSK9 and LDLR proteins were essentially as described previously (Fisher et al, 2007; Bottomley et al, 2009); full details are given in the supplementary information online.

Crystallization of PCSK9/LDLR complexes. All protein complexes were crystallized by the vapour diffusion method at 18°C. Details of the crystallization experiments are reported in the supplementary information online.

Data collection, structure determination and refinement. All X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K on ID14 beamlines at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France). The structures were determined by the molecular replacement method; full details of the protocols used are provided in the supplementary information online. Atomic coordinates have been deposited in the RCSB PDB with accession codes 3P5B and 3P5C.

Surface plasmon resonance. All SPR experiments were conducted using Biacore instruments at 25°C, essentially as described previously (Fisher et al, 2007). LDLR proteins were immobilized on the sensor surface and PCSK9 or PCSK9ΔC (a construct lacking the CTD) was injected in optimized running buffer. Full details of the titration series, sensorgram plots and data analysis methods are presented in the supplementary information online.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Orsatti, M. Pomeranz and M. Biancucci for technical support, and P. Dormitzer for critically reviewing the manuscript.

Author contributions: P.L.S., M.J.B., E.C.S., A. Calzetta and A. Cirillo performed the research. S.P., Y.G.N., B.H. and A.S. contributed tools and reagents. A. Carfi conceived the research. P.L.S., M.J.B., E.C.S. and A. Carfi analysed the data. P.L.S., M.J.B. and A. Carfi designed the research and wrote the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abifadel M, Rabes JP, Devillers M, Munnich A, Erlich D, Junien C, Varret M, Boileau C (2009) Mutations and polymorphisms in the proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9 (PCSK9) gene in cholesterol metabolism and disease. Hum Mutat 30: 520–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Moreno X, Velazquez-Campoy A, Rodriguez JC, Pocovi M, Sancho J (2008) Mechanism of low density lipoprotein (LDL) release in the endosome: implications of the stability and Ca2+ affinity of the fifth binding module of the LDL receptor. J Biol Chem 283: 22670–22679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beglova N, Jeon H, Fisher C, Blacklow SC (2004) Cooperation between fixed and low pH-inducible interfaces controls lipoprotein release by the LDL receptor. Mol Cell 16: 281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjannet S, Rhainds D, Hamelin J, Nassoury N, Seidah NG (2006) The proprotein convertase (PC) PCSK9 is inactivated by furin and/or PC5/6A: functional consequences of natural mutations and post-translational modifications. J Biol Chem 281: 30561–30572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottomley MJ et al. (2009) Structural and biochemical characterization of the wild type PCSK9-EGF(AB) complex and natural familial hypercholesterolemia mutants. J Biol Chem 284: 1313–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Goldstein JL (1986) A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science 232: 34–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH Jr, Hobbs HH (2006) Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 354: 1264–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham D et al. (2007) Structural and biophysical studies of PCSK9 and its mutants linked to familial hypercholesterolemia. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14: 413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CG, Goldstein JL, Sudhof TC, Anderson RG, Russell DW, Brown MS (1987) Acid-dependent ligand dissociation and recycling of LDL receptor mediated by growth factor homology region. Nature 326: 760–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essalmani R, Susan-Resiga D, Chamberland A, Abifadel M, Creemers JW, Boileau C, Seidah NG, Prat A (2011) In vivo evidence that furin from hepatocytes inactivates PCSK9. J Biol Chem 286: 4257–4263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser V, Limbird LE, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Russell DW (1988) Mutational analysis of the ligand binding domain of the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem 263: 13282–13290 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher TS et al. (2007) PCSK9-dependent LDL receptor regulation: effects of pH and LDL. J Biol Chem 282: 20502–20512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, Basu SK, Brunschede GY, Brown MS (1976) Release of low density lipoprotein from its cell surface receptor by sulfated glycosaminoglycans. Cell 7: 85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton EN, Knuth MW, Li J, Harris JL, Lesley SA, Spraggon G (2007) The self-inhibited structure of full-length PCSK9 at 1.9 A reveals structural homology with resistin within the C-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 14604–14609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH (2009) PCSK9: a convertase that coordinates LDL catabolism. J Lipid Res 50 (Suppl): S172–S177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Henry L, Ho YK, Pownall HJ, Rudenko G (2010) Mechanism of LDL binding and release probed by structure-based mutagenesis of the LDL receptor. J Lipid Res 51: 297–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon H, Shipley GG (2000) Vesicle-reconstituted low density lipoprotein receptor. Visualization by cryoelectron microscopy. J Biol Chem 275: 30458–30464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon H, Meng W, Takagi J, Eck MJ, Springer TA, Blacklow SC (2001) Implications for familial hypercholesterolemia from the structure of the LDL receptor YWTD-EGF domain pair. Nat Struct Biol 8: 499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HJ, Lagace TA, McNutt MC, Horton JD, Deisenhofer J (2008) Molecular basis for LDL receptor recognition by PCSK9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 1820–1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagace TA, Curtis DE, Garuti R, McNutt MC, Park SW, Prather HB, Anderson NN, Ho YK, Hammer RE, Horton JD (2006) Secreted PCSK9 decreases the number of LDL receptors in hepatocytes and in livers of parabiotic mice. J Clin Invest 116: 2995–3005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh SE, Foster AH, Whittall RA, Hubbart CS, Humphries SE (2008) Update and analysis of the University College London low density lipoprotein receptor familial hypercholesterolemia database. Ann Hum Genet 72: 485–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer G, Poirier S, Seidah NG (2008) Annexin A2 is a C-terminal PCSK9-binding protein that regulates endogenous low density lipoprotein receptor levels. J Biol Chem 283: 31791–31801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi SA, Berge KE, Berg T, Leren TP (2011) Affinity and kinetics of PCSK9 binding to LDL receptors on HepG2 cells. FEBS J 278: 2938–2950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassoury N, Blasiole DA, Tebon Oler A, Benjannet S, Hamelin J, Poupon V, McPherson PS, Attie AD, Prat A, Seidah NG (2007) The cellular trafficking of the secretory proprotein convertase PCSK9 and its dependence on the LDLR. Traffic 8: 718–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCEP-Panel (2002) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 106: 3143–3421 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni YG et al. (2010) A proprotein convertase subtilisin-like/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) C-terminal domain antibody antigen-binding fragment inhibits PCSK9 internalization and restores LDL-uptake. J Biol Chem 285: 12882–12891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer-Smith H, Basak A (2010) Regulatory effects of peptides from the pro and catalytic domains of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) on low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R). Curr Med Chem 17: 2168–2182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper DE, Jackson S, Liu Q, Romanow WG, Shetterly S, Thibault ST, Shan B, Walker NP (2007) The crystal structure of PCSK9: a regulator of plasma LDL-cholesterol. Structure 15: 545–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Rudenko G, Ludtke SJ, Deisenhofer J, Chiu W, Pownall HJ (2010) Model of human low-density lipoprotein and bound receptor based on cryoEM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 1059–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudenko G, Henry L, Henderson K, Ichtchenko K, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Deisenhofer J (2002) Structure of the LDL receptor extracellular domain at endosomal pH. Science 298: 2353–2358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW, Brown MS, Goldstein JL (1989) Different combinations of cysteine-rich repeats mediate binding of low density lipoprotein receptor to two different proteins. J Biol Chem 264: 21682–21688 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Lu C, Ryan RO (2011) A two-step binding model of PCSK9 interaction with the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem 286: 5464–5470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DW, Garuti R, Tang WJ, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH (2008) Structural requirements for PCSK9-mediated degradation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 13045–13050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Michaely P (2008) The epidermal growth factor homology domain of the LDL receptor drives lipoprotein release through an allosteric mechanism involving H190, H562, and H586. J Biol Chem 283: 26528–26537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Tuakli-Wosornu Y, Lagace TA, Kinch L, Grishin NV, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH (2006) Molecular characterization of loss-of-function mutations in PCSK9 and identification of a compound heterozygote. Am J Hum Genet 79: 514–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.