Abstract

The inward rectifier family of potassium (KCNJ) channels regulate vital cellular processes including cell volume, electrical excitability, and insulin secretion. Dysfunction of different isoforms have been linked to numerous diseases including Bartter’s, Andersen-Tawil, Smith-Magenis Syndromes, Type II diabetes mellitus, and epilepsy, making them important targets for therapeutic intervention. Using a family-based approach, we succeeded in expressing 10 of 11 human KCNJ channels tested in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. GFP-fusion proteins showed that these channels traffic correctly to the plasma-membrane suggesting that the protein is functional. A 2-step purification process can be used to purify the KCNJ channels to >95% purity in a mono-dispersed form. After incorporation into liposomes, 86Rb+ flux assays confirm the functionality of the purified proteins as inward rectifier potassium channels.

Keywords: KCNJ, Inward rectifier, Expression, Purification, Ion channels, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Introduction

Inward rectifier K+ channel proteins (variously classified as “Kir”, “IRK” or “KCNJ” proteins) generate ion channels that act as bio-diodes in cell membranes, conducting large K+ currents at membrane potentials more negative than the reversal potential for potassium (EK) while the outward flux of ions more positive to EK is reduced. The inwardly rectifying properties of these channels are the result of block by intracellular Mg2+ and polyamines [12,13]. Gating (opening and closing) of KCNJ channels is voltage-independent, however, channel activity is often directly regulated by extracellular or intracellular second messengers. For example, Kir3.x (KCNJ3, KCNJ5, KCNJ6 and KCNJ9) channels are directly activated by the Gβγ subunits of G-proteins [18], whereas Kir6.1 (KCNJ8) and Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) channels are coupled to sulfonylurea receptors, and are closed by ATP [7]. Over 15 mammalian KCNJ channel proteins have been cloned, classified into seven subfamilies [5].

Inward rectifier channels play numerous key physiological roles, particularly in stabilizing the resting membrane potential, regulating K+ ion flux across cellular membranes, and regulation of cellular excitability. These channels are expressed in a wide variety of cells including skeletal, cardiac, and vascular myocytes, neurons, and pancreatic β-cells. Mutations in KCNJ channels, or defects in their regulation, have been linked to a wide variety of disorders, including Bartter’s Syndrome (KCNJ1), epilepsy (KCNJ10), the rare genetic cardiac disorders Andersen-Tawil Syndrome (KCNJ2) and Smith-Magenis Syndrome (KCNJ12), and Type II Diabetes (KCNJ11). Thus, the KCNJ channel family presents an attractive target for the development of novel therapeutic agents for numerous diseases.

Structural and functional studies, as well as testing of novel chemical probes and drug scaffolds, can be greatly assisted by the use of highly purified functional protein. While the bacterial homologues KirBac1.1 [9], KirBac3.1 (Gulbis et al., unpublished), and KirBac1.3 in a chimeric form [16], as well as the mouse Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) [14,15] and chicken Kir2.2 (KCNJ12) [23] have been recombinantly expressed and purified previously, to date there are no published examples of human inward rectifiers that have been recombinantly expressed and purified in a functional form to sufficient levels for further structural studies. In this study, we utilized the eukaryotic budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to successfully express 10 of 11 KCNJ channels tested. A 2-step purification process for two of these, which shows that these proteins can be purified to >95% purity in a mono-dispersed tetrameric form, is described. Furthermore, sub-cellular localization and 86Rb+ flux assays on reconstituted protein indicate that they are functional as channels and can therefore be utilized for structural and functional studies. Thus, S. cerevisiae can be a cost effective system for the expression and purification of functional human inward rectifier potassium channels.

Materials and methods

Construction of pND-CTFH Vector

The pDDGFP-2 vector is modified from the p424GAL1 vector as previously described [3] and was a gift from Dr. So Iwata (Imperial College, London, UK). The pND-CTFH vector was generated by replacing the yEGFP in pDDGFP-2 with a FLAG-motif (DYKDDDDK) using enzyme-free cloning [22]. Two parallel PCR reactions were performed using Herculase DNA polymerase (Stratagene, TX) and two sets of primers: pND-CTFH_Fwd_Long (GATTACAAGGATGACGACGATAAGCACCACCACCATCATCATCATCATTAACTGCAGG) and pND-CTFH_Rev_Short (AAATTGACCTTGAAAATATAAATTTTCCCC) or pND-CTFH_Fwd_Short (CACCACCACCATCATCATCATCATTAACTGCAGG) and pND-CTFH_Rev_Long (CTTATCGTCGTCATCCTTGTAATCAAATTGACCTTGAAAATATAAATTTTCCCC). PCR fragments were DpnI treated, and 5 μL of each were mixed together and incubated at 97 °C for 15 min. The mixture was then cooled down to 15 °C and used to transform 50 μL of MACH1 competent cells and resultant plasmids were sequenced to ensure fidelity.

Transformation and expression

Forward primers were designed to include a 5′-ACCCCGGATTCTAGAACTAGTGGATCCCCC-3′ overhang sequence immediately preceding the ATG start codon. Reverse primers included 5′-AAATTGACCTTGAAAATATAAATTTTCCCC-3′ prior to the final codon of the KCNJ gene to allow for homologous recombination. KCNJ genes were amplified by PCR with Pfx Platinum DNA polymerase using a hot-start protocol. PCR products were added to SmaI digested pND-CTFH vector and transformed into the FGY217 strain of S. cerevisiae (MATa, ura3-52, lys2Δ201, pep4Δ) using a standard Li-acetate/SS carrier DNA (Sigma–Aldrich, UK) protocol. Transformants were plated onto SC-Ura plates and grown for 3 days for colonies to appear. To ensure successful transformations, colony PCR was performed on streak purified colonies by resuspending cells in 1 μL of water and extending the hot-start time to 5 min.

Ten millilitres of small scale expression tests were performed by culturing colonies in SC-Ura media supplemented with 2% glucose at 250 rpm and 30 °C. After 24 h (OD600 = 1), 1 mL of cells were used to inoculate 10 mL of SC-Ura supplemented with 2% Galactose for GAL1 induction. After 24 h of induction (OD600 = 1), cells were isolated by a 4000g spin for 5 min in a desktop centrifuge. Cells were resuspended in 200 μL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA, 0.6 mM sorbitol, complete-EDTA free protease inhibitor) and broken using acid-washed glass beads with 10 cycles of 30 s on/30 s off. Crude membranes were isolated by a 1 h 21,000g centrifugation of the supernatant at 4 °C.

Confocal microscopy

In order to determine sub-cellular localization of KCNJ proteins, yEGFP-tagged fusion proteins were expressed in 10 mL cultures as above, spun down for 5 min at 4000g, and resuspended in SC-Ura + 70% glycerol to reduce cellular mobility for better image capture. Cells were imaged using an Axioskop optical microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Germany) fitted with a Radiance 2000 laser unit (Bio-Rad) by detecting yEGFP fluorescence at 512 nm following Argon laser excitation at 488 nm. Images were captured using LaserSharp 2000 software (Bio-Rad).

Purification of human KCNJ channels

Fifteen millilitres of started cultures were grown in 50 mL falcon tubes overnight at 250 rpm and 30 °C in SC-Ura media supplemented with 2% Glucose. Starter cultures were then added to 3 L (4 × 750 mL) SC-Ura + 2% glucose in Ultrayield shaker flasks and shaken for 24 h (OD600 ~ 1.5). Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 4000g, and resuspended in 12 L of SC-Ura supplemented with 2% galactose for induction (OD600 ~ 0.2) and grown for ~ 48 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 4000g, washed once in TBS buffer, resuspended in lysis buffer, and stored at −80 °C directly, or used fresh.

Cells were ruptured by four increasing steps of high pressure (25, 30, 35, 40 kPSI) using a Constant System Cell Disrupter. Cell debris was removed by a 5 min centrifugation at 500g, followed by a 25 min centrifugation at 4000g. The supernatant was collected and centrifugated for 1 h at 120,000g to collect crude membranes. Membranes were washed in high salt buffer (50 mM Tris 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 500 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, complete-EDTA free protease inhibitor) to remove peripheral membrane proteins and re-centrifugated for 1 h at 120,000g. Washed membranes were once again resuspended in high salt buffer to ~3.5 mg/mL total protein and solubilized by the addition of 1% Fos-choline 14 (Anatrace) for 3 h at 4 °C. Solubilized membranes were clarified by centrifugation at 56,500g. One millilitre of M2 anti-Flag resin (Sigma–Aldrich, UK) was added to the supernatant and spun slowly on a blood-wheel overnight at 4 °C. The resin was washed in batch in the presence of 0.5% Fos-choline 14, packed into a drip-column and further washed, and then eluted with the addition of 0.2 mg/mL 3xFLAG peptide (Sigma–Aldrich, UK) to the wash buffer. Second and third elution fractions were combined and concentrated to 1 mL using a 100,000 MWCO concentrator (Vivaspin) and separated by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare, UK) pre-equilibrated in 20 mM Tris 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, and 0.02% Fos-choline 14.

SDS/PAGE and Western blotting

Standard techniques were used for protein electrophoresis on 4–12% pre-cast XT-Criterion SDS/PAGE gel in XT-MES buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules). Gels were stained with Instant Blue Coomassie reagent (Expedeon, UK). For Western blots, 1 μg purified protein were run on an SDS/PAGE gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with TBST + 2% BSA, and blotted with an anti-HIS antibody (Qiagen, MD) (1:750) in TBST + 2% BSA. Secondary antirabbit antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP)1 (Bio-Rad, Italy) were used at a 1:5000 dilution and the bands visualized by incubation in ECL Western blotting detection reagents (Pierce, IL).

Calculation of Stokes radius

Partition coefficients (KD) for standard proteins and KCNJ channel proteins were calculated using the equation:

| (1) |

where V0, Ve, and Vt, are the void, elution, and total volumes, respectively. The Stokes radius for each protein was estimated by a linear calibration plot of (−log KD)1/2 vs. RS as described [20].

Estimation of protein concentration

Expression levels were calculated from resuspended crude membranes using GFP fluorescence, as we found this to be more reliable than whole-cell methods described previously [3]. Briefly, crude membranes from 10 mL preparations were resuspended in 200 μL of lysis buffer and transferred into a COSTAR 3615 96-well plate. GFP fluorescence was measured at 520 nm following excitation at 485 nm using a POLARstar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech, Germany) and compared to a yEGFP standard of known concentration. The quantity of our target proteins could then be calculated by multiplying our GFP estimates by the ratio of the KCNJ:GFP expected molecular masses as previously described [3].

Purified protein quantities from FLAG-tagged constructs were determined by absorbance at 280 nm, and the formula:

| (2) |

86Rb+ flux assay

POPE (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-3-phosphatidylethanolamine) and POPG (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-3-phosphatidylglycerol; Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.) were solubilized in buffer A (450 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM NMG, pH 7.5) with 35 mM CHAPS at 10 mg/mL, mixed at a 3:1 mass ratio, and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Polystyrene columns (Pierce Chemical Co.) were packed with Sephadex G-50 beads, presoaked overnight in buffer A, and spun on a Beckman TJ6 centrifuge until reaching 3000 rpm. For each sample, 6 μg of protein was added to 100 μL of lipid (1 mg) and incubated for 20 min. Liposomes were formed by adding the protein/lipid sample to the partially-dehydrated columns and spinning to 2500 rpm. The extraliposomal solution was exchanged by spinning the sample to 2500 rpm in partially-dehydrated columns, now containing beads soaked in buffer B (400 mM sorbitol, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM NMG, pH 7.5). 86Rb+ uptake was initiated by adding 400 μL of buffer B containing 86Rb+, and 1 μM spermine when indicated. At various time points, aliquots of the liposome uptake reaction were flowed through 0.5 mL Dowex cation exchange columns in the NMGH+ form to remove extraliposomal 86Rb+. These aliquots were then mixed with scintillation fluid and counted in a liquid scintillation counter. Valinomycin was used to measure maximal 86Rb+ uptake. Data were subtracted from uptake counts measured at each time point from protein-free liposomes, and plotted relative to valinomycin-induced uptake counts.

Results

Sub-cloning, expression and sub-cellular localization of human KCNJ channels

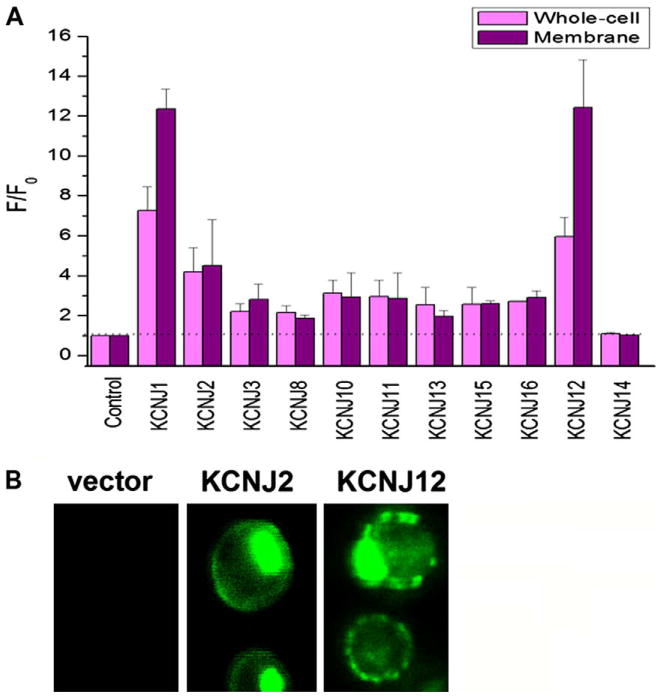

The cDNAs of 11 KCNJ channels were amplified using PCR and individually transformed into the FGY217 strain of S. cerevisiae with SmaI linearized pDDGFP-2 vector to generate a GFP-fusion protein under the control of the strong inducible GAL1 promoter. Following homologous recombination, colonies could be observed within 48–72 h. Rapid screening for expression was achieved by measuring fluorescence from whole-cells and isolated crude membranes from 10 mL cultures grown in selective SC-Ura media (Fig. 1A). Out of 11 human KCNJ channels screened, we found 10 that could be expressed in S. cerevisiae to levels between 40 and 400 μg/L. Additionally, KCNJ channels appear to traffic normally to the plasma membrane as indicated by confocal microscopy of GFP-fusion in whole-cells (Fig. 1B). Similar expression patterns were observed for all KCNJ channels we expressed (data not shown). Since S. cerevisiae have extensive quality control systems for ER exit (ERAD) [4], this implies that these channels are likely to be properly folded and functional. Vector only controls showed no fluorescence as expected since there is no start codon in the vector prior to the GFP tag.

Fig. 1.

KCNJ expression and sub-cellular localization. (A) GFP-fusion proteins were used to detect expression by whole-cell (blue) and crude membrane (red) fluorescence emission at 520 nm following excitation at 485 nm. Fluorescence from crude membranes indicated that 10 of 11 KCNJ channels tested were expressed in S. cerevisiae at 40– 400 μg/L (n = 3 for each construct). (B) Confocal microscopy indicates that KCNJ channels are trafficked to the plasma membrane of S. cerevisiae, which suggests properly folded protein. No fluorescence could be observed from control cells transformed with only the pDDGFP-2 vector, which lacks a start codon before the yEGFP.

KCNJ channels were then re-cloned into the pND-CTFH vector, which contains C-terminal FLAG and octa-histidine tags for purification steps.

Purification of two human KCNJ channels from S. cerevisiae

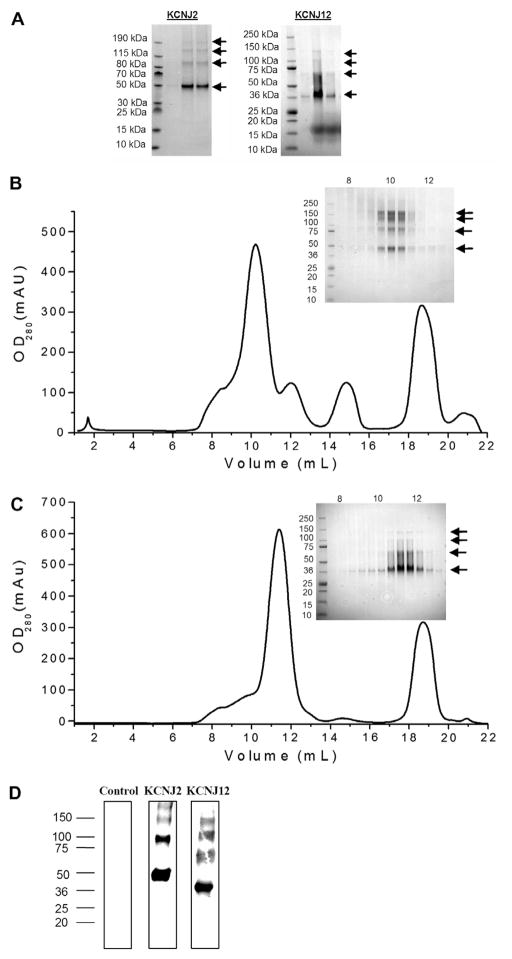

KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 channels were selected for large scale purifications. Crude membranes were isolated by ultracentrifugation and solubilized with 1% Fos-choline 14. We found Fos-choline 14 solubilized these two proteins with greater efficiency than the maltopyranoside or glucopyranosides detergents we screened, whereas Fos-choline 12 induced protein aggregation during later concentration steps. While the octahistidine tag to be effective for the purification of some other human membrane proteins using our system, we found the purity was unsatisfactory for the purification of KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 channels. Thus, M2 anti-FLAG resin (Sigma–Aldrich) was applied to solubilized crude membranes, and eluted after 3 h at 4 °C with 3xFLAG peptide. Noticeably, we observed 4 predominant bands in the elution fractions (Fig. 2A). Monomers of our KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 constructs are expected to be approximately 51.1 kDa and 41.1 kDa, respectively, and migrated slightly faster on SDS/PAGE as is commonly observed for membrane proteins. A MASCOT ion search (Matrix Science) from LC–MS/MS data following in-gel tryptic digest of each carefully dissected band confirmed that all four bands were KCNJ2 or KCNJ12 channels, respectively (data not shown). This was further confirmed by Western blot against the His-tag of purified KCNJ channels (Fig. 2D). Thus, at this stage, KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 channels could be purified to approximately 90% as determined by Coomassie stained SDS/PAGE (Fig. 2A). We estimate approximately 75% recovery using the anti-FLAG M2 resin. A ~17 kDa protein is sometimes seen in KCNJ12 elution fractions following affinity chromatography steps (Fig. 2A). When present, it is typically removed during protein concentration through a 100,000 MWCO concentrator and is not seen in any of the peak fractions following gel filtration.

Fig. 2.

Large scale purification of two human KCNJ channels. (A) SDS/PAGE analysis of two human KCNJ channels expressed in the pND-CTFH vector and purified in one step using M2 anti-FLAG resin (Sigma–Aldrich). The arrows indicate monomer, dimer, trimer and tetramer bands, all of which have been identified by LC–MS/MS. (B and C) KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 samples, respectively, were concentrated to 1 mL and further purified using a Superdex 200 10/30 GL column (GE Healthcare) at 0.2 mL/min and eluted in 0.5 mL fractions. (Inset) Coomassie stained SDS/PAGE analysis of fractions from between 8 and 13 mL, suggest that our protein is tetrameric in solution. (D) Western blot detection of purified KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 constructs using anti-HIS antibodies (Qiagen). Solubilized membranes from uninduced cells were used as controls.

A size exclusion chromatography step was included to determine whether the purified KCNJ channels were mono-dispersed in solution. Additionally, we observed that this stage was useful in removing excess detergent, as well as any unbound 3xFLAG peptide that may co-elute with our proteins. Fig. 2B and C indicates that the purified KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 channels are mono-disperse with all four bands of KCNJ2 or KCNJ12 peaking in the same fraction on the SDS/PAGE gels (insets). These data suggest that the majority of purified KCNJ channels exist in a single oligomeric species in solution. The four bands observed correspond to SDS-resistant break down species in the gel from the tetrameric state in solution. Such anomalous migration on SDS/PAGE gels has been extensively observed previously for other potassium channels from both eukaryotic and prokaryotic species [6,15,19]. These likely reflect strong SDS-resistant protein–protein interactions and the fourfold symmetry of these channels [15] that have been observed in crystal structures of various potassium channels [2,8,9,11,16].

Hydrodynamic properties of two human KCNJ channels from S. cerevisiae

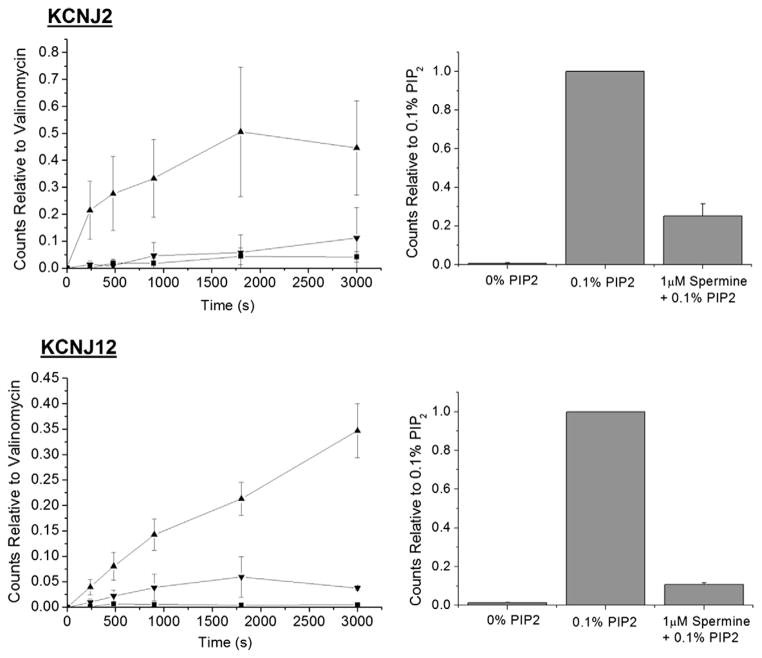

The Stokes radii (Rs) for KCNJ2 or KCNJ12 channels were determined by gel filtration. Calibration standards and purified KCNJ channels were applied to a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column equilibrated in 0.02% Fos-choline 14 buffer. The partition coefficient (KD) for each calibration protein was determined by Eq. (1) and used to determine the linear parameters of a (−log KD) vs. Rs plot (Fig. 3). KD values for KCNJ2 (0.14) and KCNJ12 (0.21) channels were then determined according to Eq. (1) and found to correspond to a Stokes radii of 62.3 ± 0.1 Å (n = 3) and 54.5 ± 0.1 Å (n = 4), respectively (Fig. 3). These values are within 4.7 Å of the previously published tetrameric KCNJ12 channels purified from native rat cortex tissue using CHAPS detergent [17]. This small discrepancy likely arises from differences in protein constructs and the purification detergent properties that are forming the protein–detergent complex. Thus, our estimation of Stokes radii provides further evidence that the purified KCNJ channels are tetrameric in solution.

Fig. 3.

Determination of Stokes radii. (A) The partition coefficient (KD) was determined for KCNJ2 (0.14) and KCNJ12 (0.21) channels as well as protein standards according to Eq. (1) following elution from a Superdex 200 10/30 GL size exclusion column. These KD correspond to a Stokes radius of 62.3 ± 0.1 Å (n = 3) and 54.5 ± 0.1 Å (n = 4), respectively.

Assessing protein function

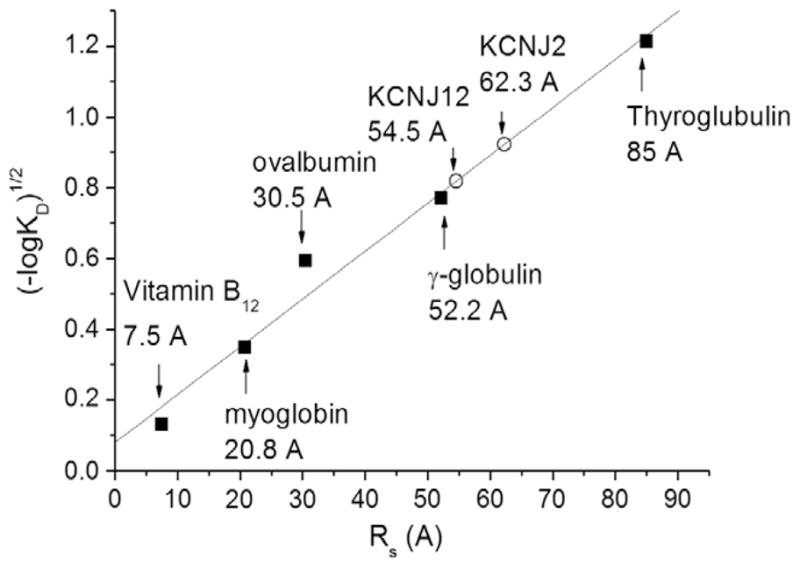

To test whether our purified KCNJ channels were functional, purified proteins were reconstituted into proteoliposomes and activity was measured using a well established 86Rb+ flux assay. In the absence of PIP(4,5)2, KCNJ channels show virtually no activity (Fig. 4), which is consistent with observed rundown of IRK currents in heterologous expression systems. However, in the presence of 0.1% PIP(4,5)2, KCNJ2 or KCNJ12 channels are active and readily allow for 86Rb+ flux which can in turn be blocked by the application of 1 μM spermine (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Functional analysis of purified KCNJ channels. 86Rb+ efflux measurements from reconstituted KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 proteins. Proteins (n = 4 for each condition) in the absence of PIP(4,5)2 (■) show little activity. However, in the presence of PIP(4,5)2 (▲), KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 proteins are active, and can in turn be blocked by the application of 1 μM spermine (▼).

Discussion

KCNJ channels are expressed in a wide variety of cells including skeletal, cardiac, and vascular myocytes, neurons, and pancreatic β-cell and play numerous key physiological roles, particularly in stabilizing the resting membrane potential, regulating K+ ion flux across cellular membranes, and regulation of cellular excitability. Mutations in KCNJ channels, or defects in their regulation, have been linked to a wide variety of disorders making this family an attractive target for the development of novel therapeutic agents for numerous diseases. In this vein, structural and functional studies, as well as testing of novel chemical probes and drug scaffolds can be greatly assisted by the use of highly purified functional protein.

Previously, bacterial and mouse homologues of KCNJ channels have been recombinantly expressed and purified [9,14–16]; [23]. However, to date we are unaware of any published examples of human inward rectifiers that have been recombinantly expressed and purified in a functional form to sufficient levels for structural or in vitro functional studies. In this study, we utilized the eukaryotic budding yeast S. cerevisiae and a family-based approach to successfully express 10 of 11 human KCNJ channels tested. The advantage of the family-based approach is that it maintains focus on human targets, it can reveal suitable candidates for further analysis, highlight individual biochemical and functional differences and allow the application of common protocols and procedures [21,24]. Using a 2-step purification process, we show that two of these channels are expressed on the plasma membrane, and can be purified to >95% purity in a mono-dispersed tetrameric form in solution. Our estimates of the KCNJ channel Stokes radii from hydrodynamic analysis for these constructs are within 4.7 Å of the previously published KCNJ12 channels purified from native rat cortex tissue that were also found to be tetrameric in solution [17] and the protein used for crystallization of the KirBac1.1 and KirBac3.1 channels (unpublished data). This small discrepancy likely arises from differences in protein constructs and the purification detergent properties that are forming the protein–detergent complex. Thus, taken together, these data indicate that these purified KCNJ proteins are tetrameric in solution, as expected for functional channels.

Due to an extensive quality control system for ER exit (ERAD) [4], appropriate sub-cellular localization is often indicative of the expression of correctly folded and functional proteins in S. cerevisiae. We observe that human KCNJ–GFP-fusion proteins traffic to the plasma membrane, and confirm the functionality of these as inward rectifier potassium channels using 86Rb+ flux assays on purified proteins reconstituted into proteoliposomes. In the absence of PIP(4,5)2, KCNJ channels show little activity, which is consistent with observed rundown of IRK currents in heterologous expression systems. However, in the presence of 0.1% PIP(4,5)2, an activator of all mammalian KCNJ channels [10], KCNJ2 and KCNJ12 channels are active and readily allow for 86Rb+ flux. This PIP(4,5)2 dependent flux can in turn be blocked by the application of 1 μM spermine as is expected for inward rectifiers. Thus, the functional behaviour of our purified KCNJ channels reflects the physiological behaviour of these channels in their natural lipid environment.

It is difficult to speculate on the basis for differences in expression levels we observed for the various channel isoforms; however, such differences have been observed for other channels and transporters [1]. We can only suppose that differences in plasmid copy number, codon usage, mRNA stability, energetics of membrane insertion, signalling or retention sequences, and/or the requirement or availability of particular chaperone proteins or binding partners for each isoform may account for the variation in channel expression.

Our data indicate that the expression and purification of monodispersed, tetrameric and functional human KCNJ channels can be achieved using S. cerevisiae as a heterologous expression system. This system provides sufficient material to allow for future detailed biochemical and structural analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant HL54171 (to CGN) and the Structural Genomics Consortium. The Structural Genomics Consortium is a registered charity (No. 1097737) funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute, GlaxoSmithKline, Karolinska Institutet, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Ontario Innovation Trust, the Ontario Ministry for Research and Innovation, Merck and Co., Inc., the Novartis Research Foundation, the Swedish Agency for Innovation Systems, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research and the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: HRP, horseradish peroxidase; POPE, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-3- phosphatidylethanolamine; POPG, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-3-phosphatidylglycerol.

References

- 1.Chloupková M, Pikert A, et al. Expression of 25 human ABC transporters in yeast Pichia pastoris and characterization of the purified ABCC3 ATPase activity. Biochemistry. 2007;46(27):7992–8003. doi: 10.1021/bi700020m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle DA, Morais-Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, et al. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280(5360):69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drew D, Newstead S, et al. GFP-based optimization scheme for the overexpression and purification of eukaryotic membrane proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(5):784–798. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellgaard L, Helenius A. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(3):181–191. doi: 10.1038/nrm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutman GA, Chandy KG, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XLI. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55(4):583–586. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heginbotham L, Odessey E, et al. Tetrameric stoichiometry of a prokaryotic K+ channel. Biochemistry. 1997;36(33):10335–10342. doi: 10.1021/bi970988i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement JP, 4th, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science. 1995;270:1166–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Cadene M, Chait BT, et al. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 2002;417(6888):515–522. doi: 10.1038/417515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo A, Gulbis JM, et al. Crystal structure of the potassium channel KirBac1.1 in the closed state. Science. 2003;300(5627):1922–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.1085028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Logothetis DE, Jin T, et al. Phosphoinositide-mediated gating of inwardly rectifying K(+) channels. Pflugers Arch. 2007;455(1):83–95. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long SB, Campbell EB, Mackinnon R. Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science. 2005;309(5736):897–903. doi: 10.1126/science.1116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopatin AN, Makhina EN, Nichols CG. Potassium channel block by cytoplasmic polyamines as the mechanism of intrinsic rectification. Nature. 1994;372:366–369. doi: 10.1038/372366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuda H, Saigusa A, Irisawa H. Ohmic conductance through the inwardly rectifying K channel and blocking by internal Mg2+ Nature. 1987;325(7000):156–159. doi: 10.1038/325156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikhailov MV, Campbell JD, et al. 3-D structural and functional characterization of the purified KATP channel complex Kir6.2-SUR1. EMBO J. 2005;24(23):4166–4175. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikhailov MV, Proks P, et al. Expression of functionally active ATP-sensitive K-channels in insect cells using baculovirus. FEBS Lett. 1998;429(3):390–394. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00640-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishida M, Cadene M, et al. Crystal structure of a Kir3.1-prokaryotic Kir channel chimera. EMBO J. 2007;26(17):4005–4015. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raab-Graham KF, Vandenberg CA. Tetrameric subunit structure of the native brain inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir 2.2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(31):19699–19707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reuveny E, Slesinger PA, et al. Activation of the cloned muscarinic potassium channel by G protein beta gamma subunits. Nature. 1994;370(6485):143–146. doi: 10.1038/370143a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwalbe RA, Wang Z, et al. Potassium channel structure and function as reported by a single glycosylation sequon. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(25):15336–15340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegel LM, Monty KJ. Determination of molecular weights and frictional ratios of proteins in impure systems by use of gel filtration and density gradient centrifugation. Application to crude preparations of sulfite and hydroxylamine reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;112(2):346–362. doi: 10.1016/0926-6585(66)90333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soundararajan M, Willard FS, Kimple AJ, Turnbull AP, Ball LJ, Schoch GA, Gileadi C, Fedorov OY, Dowler EF, Higman VA, Hutsell SQ, Sundström M, Doyle DA, Siderovski DP. Structural diversity in the RGS domain and its interaction with heterotrimeric G protein alpha-subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(17):6457–6462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801508105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tillett D, Neilan BA. Enzyme-free cloning: a rapid method to clone PCR products independent of vector restriction enzyme sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(19):e26. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tao X, Avalos JL, Chen J, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic strong inward-rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2 at 3.1 A resolution. Science. 2009;326(5960):1668–1674. doi: 10.1126/science.1180310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang X, Lee WH, Sobott F, Papagrigoriou E, Robinson CV, Grossmann JG, Sundström M, Doyle DA, Elkins JM. Structural basis for protein–protein interactions in the 14-3-3 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(46):17237–17242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605779103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]