Abstract

Introduction

Experimental models of intestinal ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury are invariably performed in mice harboring their normal commensal flora, even though multiple intestinal IR events occur in humans during prolonged intensive care confinement when they are colonized by a highly pathogenic hospital flora. The aims of this study were to determine if the presence of the human pathogen P. aeruginosa in the distal intestine potentiates the lethality of mice exposed to intestinal IR and to determine what role if any in vivo virulence activation plays in the observed mortality.

Methods

7-9 week old C57/BL6 mice were exposed to 15 minutes of superior mesenteric artery occlusion (SMAO) followed by direct intestinal inoculation of 1.0 × 106 CFU of P. aeruginosa PAO1 into the ileum and observed for mortality. Reiterative studies were performed in separate groups of mice to evaluate both the migration/dissemination pattern and in vivo virulence activation of intestinally inoculated strains using live photon camera imaging of both a constitutive bioluminescent P. aeruginosa PAO1 derivative XEN41 and an inducible reporter derivative of PAO1, the PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE that conditionally expresses the quorum sensing dependent epithelial disrupting virulence protein PA-IL.

Results

Mice exposed to 15 minutes of SMAO and reperfusion with intestinal inoculation of P. aeruginosa had a significantly increased mortality rate (p<0.001) of 100% compared to <10% for sham operated mice intestinally inoculated with P. aeruginosa without SMAO and intestinal IR alone (<50%). Migration/dissemination patterns of P. aeruginosa in mice subjected to intestinal IR demonstrated proximal migration of distally injected strains and translocation to mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney. A key role for in vivo virulence expression of the barrier disrupting adhesin PA-IL during intestinal IR was established since its expression was enhanced during IR and mutant strains lacking PA-IL displayed attenuated mortality.

Conclusions

The presence of intestinal P. aeruginosa potentiates the lethal effect of intestinal IR in mice in part due to in vivo virulence activation of its epithelial barrier disrupting protein PA-IL.

Introduction

It is now well established that following severe catabolic injury or exposure to extreme physiologic stress, the human intestinal tract can become colonized by hospital associated pathogens that replace the normal commensal flora1. Some microbiologists studying these organisms have named them “accidental pathogens” because unlike the commensal flora, they have not co-evolved with the immune systems of their hosts and as such may behave in a short sighted manner by expressing enhanced virulence when exposed to local activating “cues2.” From an evolutionary standpoint, such behavior represents a fundamental tradeoff for a colonizing pathogen given that it will have to expend energy and resources to contend with a retaliatory immune system. Yet for some wily hospital pathogens, dynamic virulence expression can result in a paradoxical toxic offensive against the host leading to systemic inflammation and lethal sepsis as these pathogens devise clever tactics to survive in the hostile environment of the intestinal tract of a critically ill patient. Depending on the virulence strategy and degree of subversion needed to survive, many accidental pathogens may completely elude clinical detection when they initiate and sustain the process of enteric driven inflammation (i.e. gut-derived sepsis)3.

Such appears to be the case with the human opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa is present in the stool of up to 50% of critically ill patients and is associated with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) where its mere presence in the gut has been shown to be an independent predictor of sepsis associated mortality4. Although clinically it has been difficult to establish causality between sepsis syndrome and a single defined intestinal pathogen, of all pathogens presumed to be causative agents in this process (i.e. Candida albicans, Enterococcus, etc.), P. aeruginosa continues to be widely regarded as one of the most common microbes associated with lethal gut-derived sepsis. In one of the most cited publications describing the microbiology of the gut during surgical critical illness, P. aeruginosa was among the top 3 pathogens present in patients with sepsis syndrome and the only pathogen independently associated with a statistically significant increase in mortality3. This was recently confirmed in critically ill trauma patients ill where those whose feces cultured positive for P. aeruginosa had a high probability of developing SIRS5. Attributable mortality in humans due to intestinal P. aeruginosa has been more difficult to prove however it has been recently suggested by two studies in which the etiology of infection- related mortality was determined by autopsy. In the first study involving soldiers from “Iraqi Freedom,” of 65 patients that died of sepsis linked to altered gut function, P. aeruginosa ranked first alongside K. pneumoniae as the most commonly identified organism6. In the second study of autopsies from 334 burn patients who died of sepsis, P. aeruginosa was identified to be the most common causative agent and was hypothesized to be gut- derived based on its culture positivity in the spleen, a common site of extraintestinal dissemination7. Molecular detection techniques have confirmed that P. aeruginosa infections among the critically ill are most often gut-derived8,9.

Previous work from our laboratory suggests that among the many contributory mechanisms by which intestinal P. aeruginosa may be a particular threat to the critically ill and injured is its ability to become “in vivo expressed” in response to activating cues released by host tissues during stress that shift its behavior to a more virulent and barrier disrupting phenotype10. For example, we have previously demonstrated in vitro that soluble products released by hypoxic intestinal epithelial cells, such as adenosine and dynorphin, directly activate the quorum sensing circuitry of P. aeruginosa, resulting in virulence expression and an enhanced ability to alter intestinal epithelial tight junctional permeability11,12. Yet whether virulence activation of intestinal P. aeruginosa develops in vivo during intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in association with mortality remains unknown.

In order to shed insight into the process by which P. aeruginosa develops a virulent phenotype when present in the gut during ischemia, we subjected mice to intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury (i.e. 15 minutes of superior mesenteric artery occlusion) followed by intestinal inoculation of P. aeruginosa into the distal intestinal tract, its primary site of colonization. The purpose of the present study was to determine the behavior of P. aeruginosa in the distal intestinal tract (ileum, cecum) following ischemia/reperfusion injury imposed by a period of superior mesenteric artery occlusion. Specifically we sought to determine the lethality of P. aeruginosa in this model and to define its distribution pattern along both the longitudinal axis of the GI tract as well as extra-intestinally following intestinal IR using photon camera imaging of inoculated bioluminescent strains. We also tested whether host intestinal IR can activate intestinal P. aeruginosa to express enhanced virulence by examining an inducible, quorum sensing dependent virulence protein the PA-IL lectin, a virulence determinant we have previously established to have a barrier disrupting and a pro-adherence effect on the epithelium. Finally, we determined, what role if any, the PA-IL lectin played on mortality when P. aeruginosa is present in the intestinal tract during ischemia and reperfusion injury.

Methods

Surgical procedure

All experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Chicago Institute for Animal Care and Use Committee. Intestinal ischemia reperfusion: 6-8 week old C57/Bl6 mice were housed with access to standard food and sterile tap water ad libitum under 12 hour light/dark cycles and allowed to acclimate for at least 72 hours prior to surgery. Mice were anesthetized with a combination of 90mg/kg of ketamine and 5mg/kg of xylazine via intraperitoneal injection. Once anesthetized, mice were restrained supine, sterilely draped and maintained in a warming blanket at steady normothermia. The abdomen was aseptically prepped and a midline laparotomy was made. Using sterile cotton swabs the bowel was eviscerated to the mouse’s left side, exposing the root of the mesentery allowing identification of the portal vein and superior mesenteric artery (SMA). A removable metal clip was placed across the SMA as close to the aorta as possible, noting the time the clamp was placed. Immediately following clamp placement, the cecum and terminal ileum were identified. Using a 0.5 cc syringe and 29 or 31 gauge needle, 200 μL of a live bacterial suspension or vehicle was injected into the lumen of the terminal ileum filling the cecum while gently occluding the ileum immediately proximal to the injection site to prevent retrograde (proximal) flow of the bacterial inoculum. The intestines were then returned into the abdominal cavity to prevent excessive fluid losses and the edges of the laparotomy loosely approximated. After the designated period of ischemia, the intestines were re-eviscerated using sterile cotton swabs and the clip was removed. After observing the intestine for 30-60 seconds to grade the hyperemic response (see below) the intestines were again returned to the abdominal cavity. 500 μL of warm sterile 0.9% saline was administered intraperitoneally and the abdominal wall was closed in 2 layers. Mice were re-housed in individual cages with free access to food (standard mouse chow) and water and observed every 6 to 8 hours for mortality.

Grading ischemia

The ischemia time and the intestines were re-eviscerated and inspected for pallor and edema prior to removing the vascular clip. The clip was removed and the level of ischemic insult subjectively graded based on the pallor observed while the clamp was on and the speed/depth (color) of the hyperemic response seen once the clip was removed and SMA flow was re-established.

Bacterial strains

A well characterized strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 used in previous studies was grown overnight on TSB agar. A single colony was selected and suspended in liquid TSB media overnight (12-14 hours). 200μL of the bacterial suspension was centrifuged at 5,000 RPM for 5 minutes, the excess TSB removed, and the remaining pellet suspended in sterile 10% glycerol to a final optical density at 600 nm of 0.10, corresponding to 1×106 CFU/ml. This suspension was immediately placed on ice; bacteria were used within 2 hours of preparation. Viable bacterial density was tested using both optical density and plating serial dilutions with no significant differences noted after 3 hours of storage on ice (data not shown). Bioluminscent strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa were prepared in identical fashion. Strain XEN41 (Calpier, Inc) is a constitutively luminescent derivative of PAO1 that has the luxCDABE cassette inserted in a constitutively expressing manner. Strain PA01/lecA∷luxCDABE is a strain of PA01 that has had the luxCDABE cassette inserted downstream of the lecA promoter; this strain is a “reporter strain” that luminesces when the lecA gene is expressed13. The relative bacterial density (CFU per ml for identical optical densities at 600 nm) was compared between the PA01, XEN41, and PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE strains and showed no significant differences. Similarly, the viabilities of XEN41 and PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE were tested both immediately after suspension and after 3 hours of storage on ice with no significant difference (data not shown).

Use of in vivo bioluminescent (photon camera) imaging to quantify spatial distribution of bacteria and spatial distribution of PA-IL lectin (lecA) expression

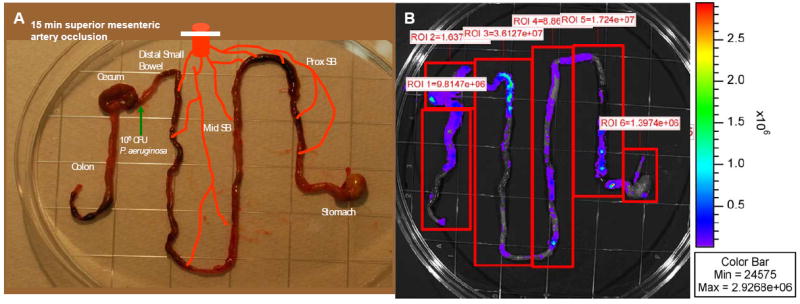

At 6 and 18 hours post-surgery mice were anesthetized with sevofluorane and sacrificed. Organs were immediately harvested, placed in Petri dishes, and then placed on ice. Organs were imaged ex-vivo within 30 minutes of harvest using the Xenogen photon camera using a 30 second exposure time. Using the “Living Image” software images were analyzed by defining the following “regions of interest (ROI)” (see figure 1). The total number of photons from each region of interest (ROI) was calculated using the Living Image software and was used as a proxy for either region specific bacterial counts (in experiments using the constitutively luminescent XEN41 strain) or as a proxy for region specific PA-IL lectin virulence expression (in experiments using the PAO1/lecA∷lux CDABE strain. In select cases organs were re-imaged 1 hour after harvest to determine if there was any variation in luminescent signal strength related to the length of time from harvest to imaging; signal strength was within 10%. (data not shown). Mouse organs from mice subjected to both sham surgery and 15 minutes of IIR with injection of vehicle (10% glycerol) without bacteria were imaged to confirm the absence of any background luminescence in the absence of bacteria (data not shown). Selected random cultures confirmed the presence of live P. aeruginosa at zones of high luminescence via culture on Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA) and no P. aeruginosa when there was no luminescence (data not shown). The technique of imaging of live bacteria has been validated and confirmed by others14. The experimental protocol is outlined in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Photon Camera imaging of ex vivo mouse intestine following intestinal ischemia reperfusion injury (IIR).

A. Image demonstrating ex vivo whole intestinal tract preparations for photon imaging, experimental protocol demonstrating site of P. aeruginosa injection, and designated regional segments. B. Arbitrary compartmentalization of “regions of interest (ROI)” for photon imaging of ex vivo segments. Color bar on right indicates photon intensity. ROI 1 refers to distal colon region, ROI 2 – to cecum, ROI 3 – to distal small bowel, ROI 4 - to mid small bowel, ROI 5 - to proximal small bowel, and ROI 6 - to stomach.

Experimental Protocol

To determine if intestinal P. aeruginosa potentiates the lethal effect of intestinal IR, mice were randomly assigned to four groups: Group I underwent 15 min IR + direct intestinal inoculation with 106 CFU P. aeruginosa, Group II was subjected to 15 min IIR + direct intestinal inoculation with vehicle (10% glycerol), Group III underwent sham surgery + direct intestinal inoculation with 106 CFU P. aeruginosa and finally group IV underwent sham surgery + direct intestinal inoculation with vehicle (10% glycerol). To determine if the PA-IL lectin is in vivo expressed in the intestine during intestinal IR, groups of mice were subjected to either intestinal IR or sham surgery and intestinally inoculated with the PA-IL lectin bioluminescent reporter strain via direct ileal injection. Finally to define the role of the PA-IL on the mortality of P. aeruginosa during in intestinal IR, reiterative studies were performed on groups of mice using the PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE strain that is deficient in PA-IL production and its wild type parent strain PAO1.

Statistical Analysis

Sum rank analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for all non- parametric data using a standard software package. Kaplan- Meier statistical analysis was used for continuous survival data. In selected cases Chi Square analysis with Yates correction for continuity was used where indicated.

Results

Pseudomonas aeruginosa in distal intestine potentiates the lethal effect of intestinal ischemia reperfusion (IIR) injury in mice

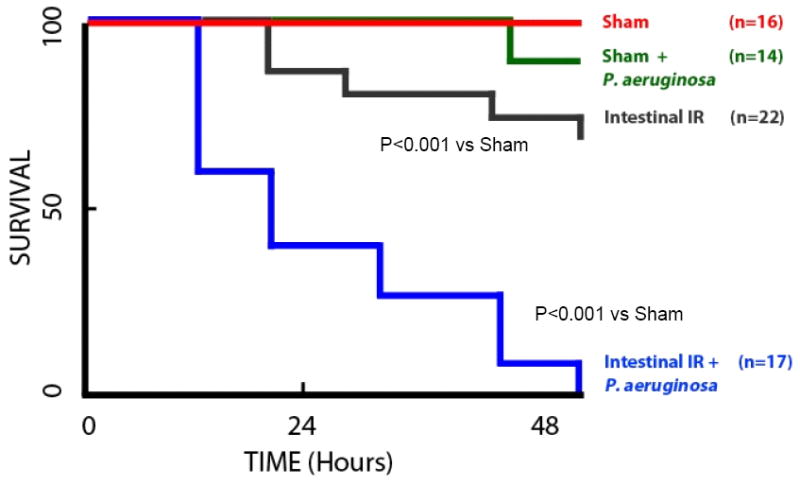

Results from the survival studies demonstrate that although intestinal IIR resulted in significant mortality (37%), this which was potentiated by the intestinal inoculation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa resulting in 100% mortality rate at 48 hours. Sham surgery, with or without intestinal inoculation with P. aeruginosa, resulted in negligible mortality (7%) at 48 hours. Mice that died appeared septic (chromodactyrrhea, ruffled fur, lethargy), whereas surviving mice appeared healthy. Mice in both groups did not develop gross signs of ileus as both groups expelled significant stool during the study period that could be visualized below the wire bottom cages that were placed to avoid coprophagia. Data are summarized in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Kaplan- Meier survival curves for mice undergoing intestinal IR in the presence and absence of P. aeruginosa.

Sham indicates mice undergoing sham laparotomy without IR; Intestinal IR indicates 15 minutes of superior mesenteric artery occlusion followed by a reperfusion period. In all cases 1 × 106 cfu of P. aeruginosa was directly inoculated into the ileum just proximal to the cecum. There was no statistical difference between Sham and Sham + P. aeruginosa (p>0.05). Intestinal IR was statistically significantly different compared to sham (p<0.001); and intestinal IR + P. aeruginosa was statistically significantly different from sham and intestinal IR (p<0.001).

P. aeruginosa virulence is “in vivo expressed”, as judged by an increase in the PA-IL lectin following intestinal IR

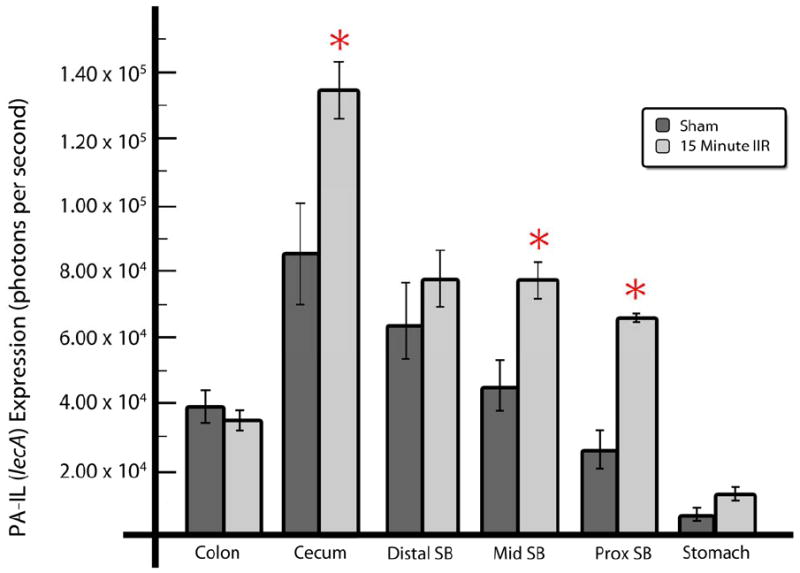

Previous work by our lab has identified a virulence related protein in P. aeruginosa, the PA-IL lectin encoded by the lecA gene, plays a major role in adherence to, and disruption of, the intestinal epithelial barrier. To quantify lecA expression, we used a bioluminescent reporter strain of P. aeruginosa PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE that luminesces when the lecA gene is expressed. Animals were subjected to either sham laparotomy or 15 minutes of intestinal IR with direct intestinal inoculation of either 106 CFU P. aeruginosa PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE or vehicle into the cecal lumen via direct ileal puncture as previously described. Animals were sacrificed 6 hours post surgery and the entire gastrointestinal tract harvested and directly imaged to measure photon emission intensity as described in the “methods” section. Results demonstrated that lecA expression was highest in the cecum, the initial injection site, as might be expected (Fig.3). Compared to sham operated mice, intestinal IR resulted in a statistically significant increase in lecA expression in the cecum, suggesting that intestinal IR signaled P. aeruginosa to express a more virulent phenotype. Although no statistical difference in lecA expression in the distal small bowel near the site of injection was observed between intestinal IR and sham, in the mid small bowel and proximal small bowel, intestinal IR induced a statistically significant increase in PAIL expression. When analyzed as the intensity ratio of intestinal IR /sham, the greatest increase in P. aeruginosa virulence expression occurred in the proximal small bowel, presumably as the result of its exposure to greatest degree of ischemia due to the SMA occlusion. These data, in combination with the distribution studies using XEN-41 (see below), suggest that SMA occlusion can result in proximal migration of P. aeruginosa to sites of ischemia and/or injury which then in turn become activated by local microenvironmental cues to express enhanced virulence.

Figure 3. Inducible expression of the virulence related protein PA-IL in P. aeruginosa following intestinal IR.

PA-IL lectin expression was measured using bioluminescent reporter strain PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE within various regions of interest of intestinal segments. Intestinal regions of interest conform to those outlined in figure 1. Data are expressed as mean ±SEM, n=5-6 per group, *p<0.05.

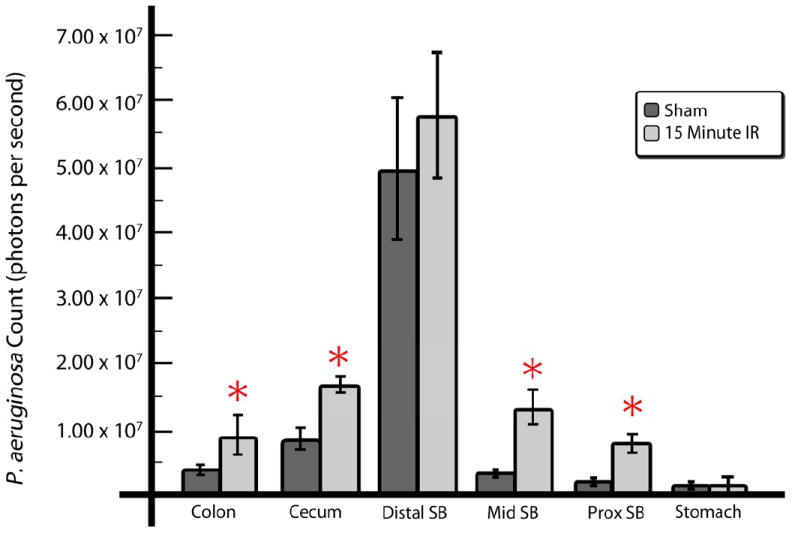

Intestinal IR alters the spatial distribution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa within the GI tract

In order to track the progression and distribution of intestinal P. aeruginosa following IR, we used XEN41, a constitutively luminescent strain of P. aeruginosa. Groups of mice were sacrificed at early (6h) and late (18h, Fig. 4) time points following 15 minutes of SMA occlusion and intestinal inoculation of 1×106 CFU of bacteria via direct ileal puncture. The entire gastrointestinal tract was harvested and directly imaged to measure photon emission intensity as previously described. Data demonstrate that intestinal IR had a significant effect on the relative and absolute distribution of intestinal P. aeruginosa following its inoculation into the cecum. This effect appeared to be time dependent appearing at 18 hours post-ischemia (Fig. 4) but not at 6 hours (data not shown). Although in many cases, migration occurred all the way into the stomach following ischemia, due to the high variance in the means between groups, this was not statistically significant.

Figure 4. Spatial distribution of constitutive bioluminescent P. aeruginosa XEN41 following direct ileal inoculation by intestinal region at varying time points.

Photon counts of constitutive bioluminescent P. aeruginosa following direct ileal inoculation by intestinal region at (A) 6 hours and (B) 18 hours following intestinal IR compared to sham operated animals. At 18 hours, a statistically significant difference was observed whereby bioluminescent strains were seen to migrate proximally in mice exposed to intestinal IR as far as the stomach. Data are expressed as mean ±SEM, n=5-6 per group, *p<0.05.

Intestinal IR promotes Pseudomonas aeruginosa translocation to extraintestinal sites

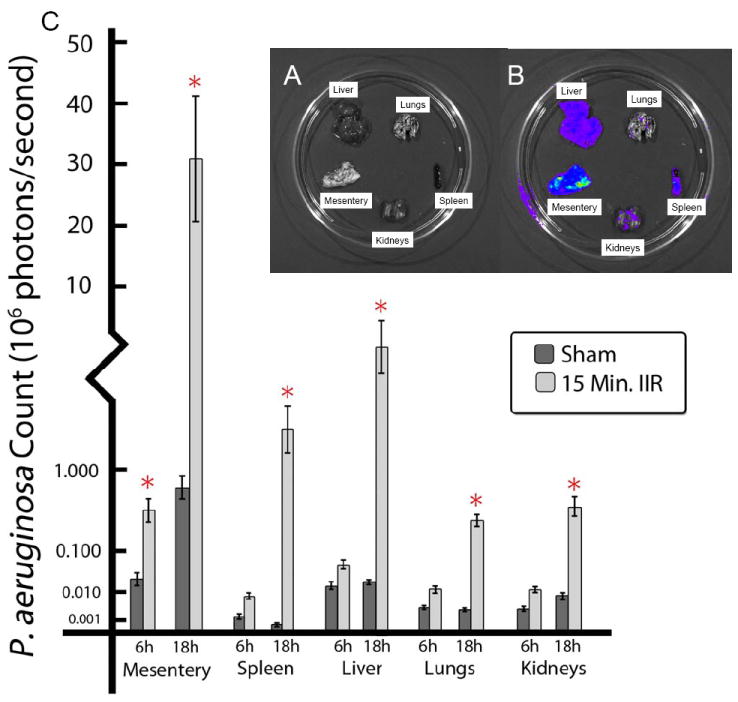

To track the extraintestinal migration of P. aeruginosa following intestinal IR, we used the XEN41 constitutively luminescent strain of P. aeruginosa and determined its present in the mesentery, spleen, liver, lungs, and kidneys following 15 minutes of SMA occlusion and its direct inoculation into the cecum via ileal puncture. Significant translocation to various organs was observed in mice subjected to intestinal IR. This effect appeared to be most prominent in the liver and spleen (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Translocation of constitutive bioluminescent P. aeruginosa XEN41 to internal organs following direct ileal inoculation.

A. Organs were harvested and placed on dishes for live photon imaging of constitutive bioluminescent P. aeruginosa. B. Photon imaging of organs. C. Bioluminescence counts. Mesenteric lymph node aggregates displayed the highest levels of bioluminescence. Data are expressed as mean ±SEM, n=5-6 per group, *p<0.05.

The adherence and epithelial barrier disrupting protein PA-IL (encoded by lecA) plays a major role in the lethal effect of intestinal P. aeruginosa following intestinal IR

We have previously shown that the PA-IL lectin adhesin of P. aeruginosa plays a major role in adherence to and disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier following major surgical injury15. Previous studies using null mutants of P. aeruginosa lacking PA-IL showed attenuated mortality in mice subjected to 30% surgical hepatectomy16. Whether the PA-IL lectin plays a similar role in ischemia reperfusion injury however is unknown. Therefore, re-iterative survival experiments were performed comparing the mortality of mice subjected to mild (15 minutes) IIR and injection of either the laboratory strain of P. aeruginosa PA01 compared to a derivative PA-IL deficient mutant. Mice subjected to 15 minutes of intestinal IR and intestinally inoculated with PA01, as previously demonstrated had 100% mortality (6 of 6 dead at 48 hours), however mice undergoing 15 min of intestinal IR with intestinal inoculation of the PA-IL null mutant (PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE) had significantly attenuated mortality (2/6) at 48 hours (p<0.05 Chi Square), a rate similar to those undergoing intestinal IR alone (see Fig. 2).

Discussion

That intestinal P. aeruginosa may play a predominant role in lethal gut derived sepsis during ischemia compared to other commonly colonizing pathogens was demonstrated over 30 years ago in a rat model in which devascularized and ligated loops of small intestine were luminally injected with various test pathogens including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Bacteroides fragilis, Enterococcus faecalis, Candida albicans, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa resulted in 100% mortality, the highest of the group with Enterococcus resulting in only 8% mortality and Candida albicans 22%17. Yet despite this and other similar studies, P. aeruginosa is often not considered to be a classical cause of lethal gut-derived sepsis compared to Candida and Enterococcus, primarily as a result of it not being recovered from the blood with the same frequency as other pathogens. Yet among the injured and immunocompromised, it remains one of the most common organisms isolated from stool and one of the most common organisms associated with gut- origin sepsis.

Recent advances from our laboratory describing how colonizing microbes sense local cues released into the gut during physiologic stress and injury have elucidated the molecular details by which opportunistic pathogens “sense” host stress and “respond” with enhanced virulence18. Although environmental information processing by bacteria is not unique to P. aeruginosa, the degree of virulence expressed by this particular pathogen in response to host products released during extreme physiologic stress may shed insight into why its mere presence in the gut can pose a significant threat to an injured host. The finding in the present study suggest that not only does intestinal IR potentiate the virulence and lethality of P. aeruginosa, but its antegrade migration into the proximal GI tract could develop as a result of a yet- to- be defined chemical trail composed of host factors locally released from ischemia and reperfusion end-products.

In our previous in vitro modeling of ischemia, we exposed cultured intestinal epithelial monolayers (Caco-2) to hypoxia and re-oxygenation and tested the apical media for its ability to induce P. aeruginosa to express the PA-IL protein19. Compared to normoxic cells, the apical media from hypoxia/re-oxygenated Caco-2 cells had a profound inducing effect on PA-IL expression that resulted in adherence to and disruption of the cell monolayers. We identified the soluble inducing product to be adenosine, which we discovered is taken up by P. aeruginosa and converted to inosine via bacterial adenosine deaminase, leading to inosine activation of the quorum sensing signaling system and enhanced virulence. When we generated Caco-2 cells with forced expression of the hypoxia inducible transcriptional regulator HIF1-α, we observed that adenosine was also released in sufficient quantities to activate P. aeruginosa quorum sensing19. As adenosine is an important epithelial cytoprotectant that is released apically and binds to receptors that promote epithelial barrier integrity and function, the ability of P. aeruginosa to take up and metabolize adenosine while and at the same time activate its virulence is an intriguing subversive tactic of this highly aggressive pathogen underscoring its unique ability to alter barrier function and cause lethality.

Results from the present study suggest similar in vivo behavior of P. aeruginosa whereby it can activate its quorum sensing signaling system as judged by in vivo expression of the PA-IL lectin. Previous work from our lab has shown that expression of the PA-IL lectin is dependent on an intact quorum sensing signaling system and facilitates binding of P. aeruginosa to the intestinal epithelium and alters tight junctional permeability via its effect on occludin and ZO-120. In the present study, we specifically designed experiments where P. aeruginosa was injected into the distal intestinal tract and ischemia induced at the level of the superior mesenteric artery to mimic the clinical condition. It is well established that P. aeruginosa is highly prevalent in the stool of critically ill patients many of whom can be exposed to episodes of intestinal ischemia via hemorrhage, vasopressor use, and direct vascular occlusion during surgery. The primary colonization site of P. aeruginosa is in the distal intestinal tract. Interestingly, results from the present study demonstrated that there was antegrade migration of the distally injected P. aeruginosa toward the proximal small bowel and stomach, suggesting that P. aeruginosa may be able to remotely sense the presence of products of ischemia and migrate along a chemical trail. We were careful in this study not to allow coprophagia in mice to confound our findings by using a series of wire bottom cages and frequent mouse isolation from stool via cage changes. Although results from the present study could still represent oral fecal contamination rather than antegrade migration, we attempted to test this by feeding mice the bioluminescent strain. Oral tracking of bioluminescent strains demonstrated complete passage of the microbe through the intestinal tract of normal coprophagic mice without evidence of retention of the luminescent probe in the small bowel (unpublished observations). Therefore it is quite likely that distal inoculation of P. aeruginosa in the presence of superior mesenteric artery occlusion with intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury resulted in a luminal chemical gradient that promoted the observed antegrade migration pattern. In a few cases we observed migration as far proximally as the esophagus, raising the possibility, as others have suggested, that intestinal P. aeruginosa is a source of airway contamination.

The pattern of translocation of bioluminescent bacteria to extraintestinal tissues was not unexpected. P. aeruginosa is one of the most common intestinal pathogens to translocate to remote organs and was one of the first organisms described as a cause of gut-derived sepsis in humans21. In the present study, the mesenteric lymph nodes appeared to take a large microbial burden following intestinal IR based on mean bioluminescence values. Other typical sites of translocation such as the spleen and liver were significantly higher following intestinal IR. It would have been interesting to determine if strains of P. aeruginosa had become differentially activated in vivo to express enhanced virulence following IR once they translocated. However because PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE is deficient in PA-IL lectin production, its translocation/ dissemination rate is dramatically reduced as is its lethality22, 23. In addition, translocation to organs such as the mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, spleen, etc, invariably develops at colony counts well below the quorum sensing activation threshold (i.e <107-8 cfu/ml) for P. aeruginosa. Although in pure culture, P. aeruginosa cannot be induced to express the PA-IL lectin and other quorum sensing dependent virulence determinants below the cell density of its quorum (i.e <107-8 cfu/ml), it is possible in vivo that the quorum could be induced at lower bacterial cell densities owing to the presence of unique host factors released during stress. Furthermore, under conditions of spatial confinement, certain bacteria may express enhanced virulence as quorum sensing molecules become highly concentrated in microscopic spaces 24.

While little insight in terms of the degree of microbial burden that translocated was gained from the present study, the potential utility of using photon camera imaging of this phenomenon to capture the time correlates may be useful in future studies. It is technically now possible to use photon imaging to simultaneously examine host proteins at localized sites of bacterial translocation and correlate spatial and temporal host- pathogen dynamics to the clinical course of experimental sepsis. Data from the present study seem to suggest that even as far as the lung, intestinal bacteria have the potential to influence the inflammatory response. Photon imaging of live replicating in situ bacteria can identify microbes that may be uncultivable and may shed light on the process by which migrating microbes can affect of variety of inflammatory responses remote from their site of origin. However as many studies show, identifying microbial burden only from the standpoint of quantitative ex vivo culture is insufficient to explain the complex interactions that occur between expressed microbial virulence proteins and the immune system25.

That the PA-IL lectin is in vivo expressed in the gut of mice subjected to intestinal IR, confirms our in vitro findings that cultured intestinal epithelial cells exposed to hypoxia secrete compounds that activate P. aeruginosa virulence. Furthermore, that the PA-IL lectin plays a major role in lethal sepsis in this model, confirms our previous work that this protein is a key factor in the mechanism of lethality in this model. Our laboratory has focused our efforts on understanding lethal gut-derived sepsis from a very microbe centered view, recognizing that there are important immune elements participating in this process. The unifying hypothesis of our lab is that extreme physiologic stress results in the release of various host factors that become concentrated at sites of dense microbial colonization such as the gut and lung. Certain of these host factors are then intercepted by a select group of microbes, i.e. accidental pathogens, which then activate several systems of virulence gene expression resulting in a toxic offensive against the host. In the case of gut bacteria, this process begins at the intestinal epithelial barrier. The PA-IL lectin appears to play an important initiating role in this response by allowing lethal cytotoxins, such as exotoxin A and elastase, to permeate across the mucosa and cause lethal sepsis15. Therefore the findings that mutant strains devoid of PA-IL lectin are attenuated in lethality in this model, and that parental strains increase PA-IL expression when present in the intestinal tract exposed to IR, lends confidence to the notion that at least in part, the response of certain microbes to intestinal IR may play a role in lethal gut- derived sepsis. Importantly, this observation does not appear to be specific to any particular strain of P. aeruginosa as most strains harbor the PA-I lectin and require quorum sensing for virulence 15. As such it is not so much the strain of bacteria acquired, but the context dependent virulence expression that develops as a result of the release of environmental and host derived cues. Obviously there are important barrier related and immune activating events that also participate in this process.

The mortality of intestinal IR in the presence of intestinal P. aeruginosa is not surprising, given the highly aggressive nature of this pathogen in general and the stress of IR itself. The mortality rate of mice who received simultaneous intestinal ischemia/ reperfusion injury and injection of P. aeruginosa into the GI lumen was 100%, far in excess of the sum of the individual insults alone: ischemia/ reperfusion alone 37% mortality, P. aeruginosa alone 7% mortality. While the small intestinal tract in general carries a low microbial burden, under conditions where there is obstruction, ileus, use of antacids, and artificial feeding, hospital pathogens may predominate in various sites along the small bowel. Yet data from our study suggest that under certain circumstances, the small bowel can become colonized by distal pathogens that migrate proximally. The local “cues” and conditions responsible for this effect require further investigation and could lead a better understanding of the consequences of intestinal IR during various stress conditions and during surgery that imposes a period of intestinal ischemia.

A major limitation of the study is that, in an effort to circumvent the multiple clearance mechanisms that exist in the foregut and proximal bowel (acid, bile, epithelial defensins, etc), we directly injected bacteria into the distal bowel to ensure their colonization and survival. Although this experimental approach is clearly unphysiologic from the standpoint of microbial acquisition and colonization, it did prove useful in these experiments. A more physiologic approach (use of anti-acids, antibiotics, morphine to induce ileus, etc) may be warranted in future studies to more closely recapitulate clinical colonization patterns.

In summary, the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the distal intestinal tract potentiates the lethal effect of intestinal ischemia/ reperfusion by mechanisms that may involve in vivo virulence activation of the known epithelial barrier dysregulating protein the PA-IL lectin and microbial migration. Further elucidation of this effect will require a more comprehensive understanding of how dynamic activation of microbial virulence factors intersects with epithelial and systemic immune elements to cause lethal gut-derived sepsis.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH RO1 GM062344-11 and by the University of Chicago BSD Imagine Research Institute for Pilot Research Projects Using Animal Imaging. We thank Steve Diggle, Nottingham University, UK for the kind gift of PAO1/lecA∷luxCDABE strain.

This work was supported by NIH grant 5R01GM062344-11 (JCA) and by the University of Chicago BSD Imagine Research Institute for Pilot Research Projects (JCA).

References

- 1.Kola A, Schwab F, Barwolff S, Eckmanns T, Weist K, Dinger E, Klare I, Witte W, Ruden H, Gastmeier P. Is there an association between nosocomial infection rates and bacterial cross transmissions? Crit Care Med. 2010 Jan;38(1):46–50. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b42a9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Accidental virulence, cryptic pathogenesis, martians, lost hosts, and the pathogenicity of environmental microbes. Eukaryot Cell. 2007 Dec;6(12):2169–74. doi: 10.1128/EC.00308-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamme K, Liigant A, Tapfer H, Talvik R. Bacterial dissemination and the value of blood cultures in patients who die of septic shock. J Int Med Res. 2000 Sep-Oct;28(5):199–206. doi: 10.1177/147323000002800501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall JC, Christou NV, Meakins The gastrointestinal tract. The “undrained abscess” of multiple organ failure. JL Ann Surg. 1993 Aug;218(2):111–118. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199308000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimizu K, Ogura H, Goto M, Asahara T, Nomoto K, Morotomi M, Yoshiya K, Matsushima A, Sumi Y, Kuwagata Y, Tanaka H, Shimazu T, Sugimoto H. Altered gut flora and environment in patients with severe SIRS. J Trauma. 2006 Jan;60(1):126–33. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197374.99755.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez R, Murray CK, Hospenthal DR, Cancio LC, Renz EM, Holcomb JB, Wade CE, Wolf SE. Causes of mortality by autopsy findings of combat casualties and civilian patients admitted to a burn unit. J Am Coll Surg. 2009 Mar;208(3):348–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma BR, Harish D, Singh VP, Bangar S. Septicemia as a cause of death in burns: an autopsy study. Burns. 2006 Aug;32(5):545–9. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murono K, Hirano Y, Koyano S, Ito K, Fujieda K. Molecular comparison of bacterial isolates from blood with strains colonizing pharynx and intestine in immunocompromised patients with sepsis. J Med Microbiol. 2003 Jun;52(Pt 6):527–30. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mencacci A, Cenci E, Repetto A, Mazzolla R, Bistoni F, Aversa F, Aloisi T, Vecchiarelli A. A multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate from a lethal case of sepsis induces necrosis of human neutrophils. J Infect. 2006 Dec;53(6):e259–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alverdy JC, Chang EB. The re-emerging role of the intestinal microflora in critical illness and inflammation: why the gut hypothesis of sepsis syndrome will not go away. J Leukoc Biol. 2008 Mar;83(3):461–6. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaborina O, Lepine F, Xiao G, Valuckaite V, Chen Y, Li T, Ciancio M, Zaborin A, Petrof EO, Turner JR, Rahme LG, Chang E, Alverdy JC. Dynorphin activates quorum sensing quinolone signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 2007 Mar;3(3):e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel NJ, Zaborina O, Wu L, Wang Y, Wolfgeher DJ, Valuckaite V, Ciancio MJ, Kohler JE, Shevchenko O, Colgan SP, Chang EB, Turner JR, Alverdy JC. Recognition of intestinal epithelial HIF-1alpha activation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007 Jan;292(1):G134–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00276.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winzer K, et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lectins PA-IL and PA-IIL Are Controlled by Quorum Sensing and by RpoS. J Bacteriology J Bacteriol. 2000 November;182(22):6401–6411. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.22.6401-6411.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiles S, Pickard KM, Peng K, MacDonald TT, Frankel G. In vivo bioluminescence imaging of the murine pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Infect Immun. 2006 Sep;74(9):5391–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00848-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu L, Holbrook C, Zaborina O, Ploplys E, Rocha F, Pelham D, Chang E, Musch M, Alverdy J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa expresses a lethal virulence determinant, the PA-IL lectin/adhesin, in the intestinal tract of a stressed host: the role of epithelia cell contact and molecules of the Quorum Sensing Signaling System. Ann Surg. 2003 Nov;238(5):754–64. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094551.88143.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alverdy J, Holbrook C, Rocha F, Seiden L, Wu RL, Musch M, Chang E, Ohman D, Suh S. Gut-derived sepsis occurs when the right pathogen with the right virulence genes meets the right host: evidence for in vivo virulence expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann Surg. 2000 Oct;232(4):480–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yale CE, Balish E. Intestinal strangulation in germfree and monocontaminated dogs. Arch Surg. 1979 Apr;114(4):445–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1979.01370280099014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seal JB, Morowitz M, Zaborina O, An G, Alverdy JC. The molecular Koch’s postulates and surgical infection: a view forward. Surgery. 2010 Jun;147(6):757–65. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel NJ, Zaborina O, Wu L, Wang Y, Wolfgeher DJ, Valuckaite V, Ciancio MJ, Kohler JE, Shevchenko O, Colgan SP, Chang EB, Turner JR, Alverdy JC. Recognition of intestinal epithelial HIF-1alpha activation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007 Jan;292(1):G134–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00276.2006. Epub 2006 Aug 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laughlin RS, Musch MW, Hollbrook CJ, Rocha FM, Chang EB, Alverdy JC. The key role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA-IL lectin on experimental gut-derived sepsis. Ann Surg. 2000 Jul;232(1):133–42. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200007000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tancrède CH, Andremont AO. Bacterial translocation and gram-negative bacteremia in patients with hematological malignancies. J Infect Dis. 1985 Jul;152(1):99–103. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alverdy J, Holbrook C, Rocha F, Seiden L, Wu RL, Musch M, Chang E, Ohman D, Suh S. Gut-derived sepsis occurs when the right pathogen with the right virulence genes meets the right host: evidence for in vivo virulence expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann Surg. 2000 Oct;232(4):480–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chemani C, Imberty A, de Bentzmann S, Pierre M, Wimmerova M, Guery BP, Faure K. Role of LecA and LecB lectins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced lung injury and effect of carbohydrate ligands. Infect Immun. 2009 May;77(5):2065–75. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01204-08. Epub 2009 Feb 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HJ, Boedicker JQ, Choi JW, Ismagilov RF. Defined spatial structure stabilizes a synthetic multispecies bacterial community. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Nov 25;105(47):18188–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807935105. Epub 2008 Nov 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye X, Ding J, Zhou X, Chen G, Liu SF. Divergent roles of endothelial NF-kappaB in multiple organ injury and bacterial clearance in mouse models of sepsis. J Exp Med. 2008 Jun;205(9)(6):1303–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071393. Epub 2008 May 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]