Abstract

Excessive demands on the protein folding capacity of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) cause irremediable ER stress and contribute to cell loss in a number of cell degenerative diseases, including type 2 diabetes and neurodegeneration1,2. The signals communicating catastrophic ER damage to the mitochondrial apoptotic machinery remain poorly understood3-6. We used a biochemical approach to purify a cytosolic activity induced by ER stress that causes release of cytochrome c from isolated mitochondria. We discovered that the principal component of the purified pro-apoptotic activity is proto-oncogene CT10-regulated kinase (CRK), an adaptor protein with no known catalytic activity7. Crk-/- cells are strongly resistant to ER stress-induced apoptosis. Moreover, CRK is cleaved in response to ER stress to generate an N-terminal ~14kD fragment with greatly enhanced cytotoxic potential. We identified a putative BCL2 homology-3 (BH3) domain within this N-terminal CRK fragment, which sensitizes isolated mitochondria to cytochrome c release and when mutated significantly reduces CRK's apoptotic activity in vivo. Together these results identify CRK as a pro-apoptotic protein that signals irremediable ER stress to the mitochondrial execution machinery.

Irremediable ER stress represents a form of intrinsic cell damage that culminates in activation of the BAX/BAK-dependent mitochondrial apoptotic pathway3,4. Homo-oligomerization of BAX and/or BAK consequently results in outer mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and release of pro-death mitochondrial proteins (e.g., cytochrome c) into the cytosol, causing activation of effector caspases8-10. For many forms of cell injury, including ER stress, we have a limited understanding of the cellular transducers that relay the information of upstream damage to BAX/BAK oligomerization at mitochondria. To date, the only known BAX and/or BAK activators are members of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only family, a diverse class of polypeptides containing a loosely conserved ~9-12 amino acid BH3 death domain11,12,13. The BH3-only proteins BID, BIM, NOXA and PUMA have been previously implicated in ER stress-induced death14,15; however, cells deficient in one or more of these proteins are not completely resistant to this form of apoptosis16-18. Therefore, it is highly probable that additional proteins that communicate ER stress to the mitochondrial apoptotic machinery remain to be discovered. To pursue this possibility, we took an unbiased biochemical approach to purify the major ER stress-induced cytosolic pro-apoptotic activity.

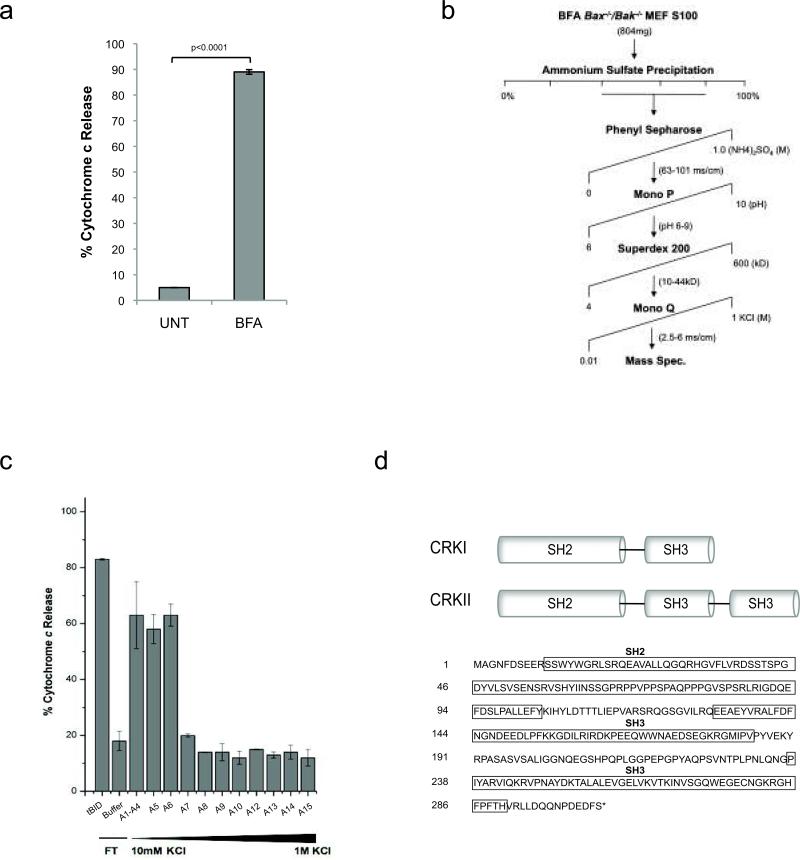

Given their strong resistance to ER stress-induced apoptosis 16,17, we reasoned the Bax-/-Bak-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) present a unique and powerful tool to trap and identify pre-mitochondrial apoptotic signals activated by ER stress. Therefore, we challenged SV40-transformed Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs with the pharmacological agent Brefeldin A (BFA), which blocks ER-golgi protein transport, to induce irremediable ER stress and initiate the pre-mitochondrial apoptotic program. We prepared cytosolic extracts (S100) from untreated or BFA-treated Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs, then incubated isolated Jurkat mitochondria with these extracts, and measured the amount of mitochondrial cytochrome c released as a readout for pro-apoptotic activity. The S100 of BFA-treated Bax-/-Bak-/- cells triggers the release of ~90% of total intra-mitochondrial cytochrome c in a BAX/BAK-dependent manner15, while the S100 fraction from untreated Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs induces negligible (<5%) cytochrome c release (Fig. 1a). Thus, ER stress induces a cytosolic activity capable of releasing mitochondrial cytochrome c, which we have termed Cytochrome c Releasing Activity (CcRA). We previously found that proteolytically active BID (tBID) is responsible for a portion of this CcRA (~30%), but that the majority of CcRA remains intact in BFA-treated Bid-/- S10015. Therefore, we designed and performed a biochemical purification strategy to isolate additional CcRA factors in the BFA-treated Bax-/-Bak-/- S100 (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Biochemical purification of ER stress apoptotic activity identifies proto-oncogene CT-10-regulated kinase (CRK).

(a) Induction of cytochrome c release from isolated Jurkat mitochondria by cytosolic extracts (S100) from untreated (UNT) and 24h Brefeldin A (BFA) 2.5 μg/ml treated Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs. (b) FPLC purification scheme of cytochrome c releasing activity (CcRA) present in BFA Bax-/-Bak-/- S100. Active fractions from each purification step are indicated. (c) CcRA assay of the fractions from the final step of the purification (MonoQ ion exchange gradient). (d) Diagram of CRK isoforms, domains, and amino acid sequence.

The CcRA-containing fractions from the final step (MonoQ gradient) (Fig. 1c) of the purification scheme did not contain detectable amounts of any known BH3-only protein by immunoblotting (data not shown), and so were analyzed by MALDI mass spectrometry (Fig. 1c). Proto-oncogene CT10-regulated kinase (CRK) was the highest confidence protein identified by mass spectrometry in the active fractions, with approximately 25% of the total sequence represented in 6 tryptic peptides (Supplementary Table 1). C-crk encodes two splice isoforms, CRKI (28kD) and CRKII (38kD)7, which have been previously recognized as adaptor components in multi-protein complexes involved in cell morphology, movement, proliferation, and differentiation19. CRKI and CRKII share a common Src homology 2 (SH2) domain and SH3 domain, while CRKII contains an additional C-terminal SH3 domain (Fig. 1d)19. As the peptides detected by mass spectrometry are common to both CRKI and CRKII, this information did not differentiate which isoform is present in the analyzed fractions (Supplementary Table 1).

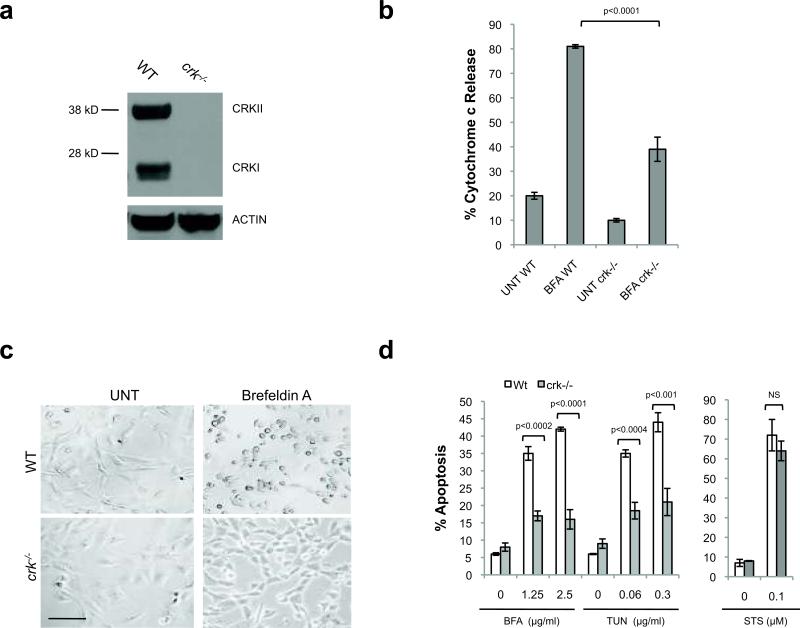

To test if CRK plays a role in ER stress-induced apoptosis in cells, we challenged crk-/- and wild-type (WT) matched MEFs with BFA or tunicamycin (TUN), an ER stress agent that specifically inhibits N-linked glycosylation. As previously reported, these crk-/- MEFs are derived from genetically engineered embryos that fail to express either CRKI or CRKII20 (Fig. 2a). Notably, S100 from BFA-treated crk-/- MEFs has significantly decreased CcRA compared to that from BFA-treated WT MEFs (Fig. 2b), indicating that CRK is required for the majority of the ER stress-induced apoptotic signal. In addition, crk-/- MEFs are strikingly resistant to ER stress-induced apoptosis, but as sensitive as WT MEFs to staurosporine (STS), a pan-kinase inhibitor known to activate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway independently of ER stress, thereby confirming the pro-apoptotic role of CRK specifically in the ER stress-induced apoptotic pathway, rather than generally from other intrinsic stresses (Fig. 2c, d).

Figure 2. Crk-/- MEFs are significantly resistant to ER stress-induced apoptosis.

(a, b) 18h BFA (2.5 μg/ml)-treated crk-/- MEF S100 contains significantly less CcRA in comparison to 18h BFA-treated (2.5 μg/ml) wild-type MEF S100. n=3, error bars = sd. (c) crk-/- MEFs are visually resistant (phase contrast) to ER stress-induced apoptosis (BFA 2.5μg/ml). Scale bar, 100μm. (d) crk-/- MEFs are strongly resistant to BFA and TUN-induced apoptosis, but equally sensitive to staurosporine (STS), in comparison to wild-type MEFs. n=3, error bars = sd.

To investigate which CRK isoform is necessary for ER stress-induced apoptosis, we reconstituted crk-/- MEFs by transient transfection with expression constructs encoding either crkI or crkII and evaluated their sensitivity to ER stress-induced apoptosis. Surprisingly, crkI and crkII are both able to independently rescue the sensitivity of crk-/- MEFs to ER stress-induced apoptosis, arguing that a sequence common to CRKI and CRKII is required for CRK's apoptotic activity (Fig. 3a,b). We next attempted to use retroviral vectors to establish stable cells lines of crk-/- MEFs expressing either crkI or crkII. While we had no difficulty recovering cells reconstituted with crkII, all attempts to establish stable crkI expression in crk-/- MEFs were unsuccessful, indicating that CRKI may be inherently cytotoxic. Stable reconstitution of crkII in crk-/- MEFs restores sensitivity to ER stress agents, but does not affect the response to STS (Fig. 3c-e), recapitulating the transient expression results (Fig. 3a). Moreover, stable overexpression of crkII and transient overexpression of crkI further sensitizes WT MEFs to ER stress (Fig. 3f-i). Together, these data strongly argue that CRK is a critical component of the ER stress-induced apoptotic pathway.

Figure 3. CRKI or CRKII restores sensitivity of crk-/- MEFs to ER stress-induced apoptosis.

(a, b) Transient expression of CRKI or CRKII sensitizes crk-/- MEFs to BFA-induced apoptosis. n=3, error bars = sd. (c-e) Stable CRKII expression in crk-/- MEFs rescues sensitivity to 24h BFA- and 18h TUN-induced apoptosis, but does not change sensitivity to STS-induced apoptosis. n=3, error bars = sd. Scale bar, 100μm. (f, g) Stable overexpression of CRKII in wild-type MEFs further increases sensitivity to 18h BFA-induced apoptosis. n=3, error bars = sd. (h, i) Transient overexpression of CRKI sensitizes WT MEFs to 18h BFA (1.25 μg/ml)-induced apoptosis. n=3, error bars = sd.

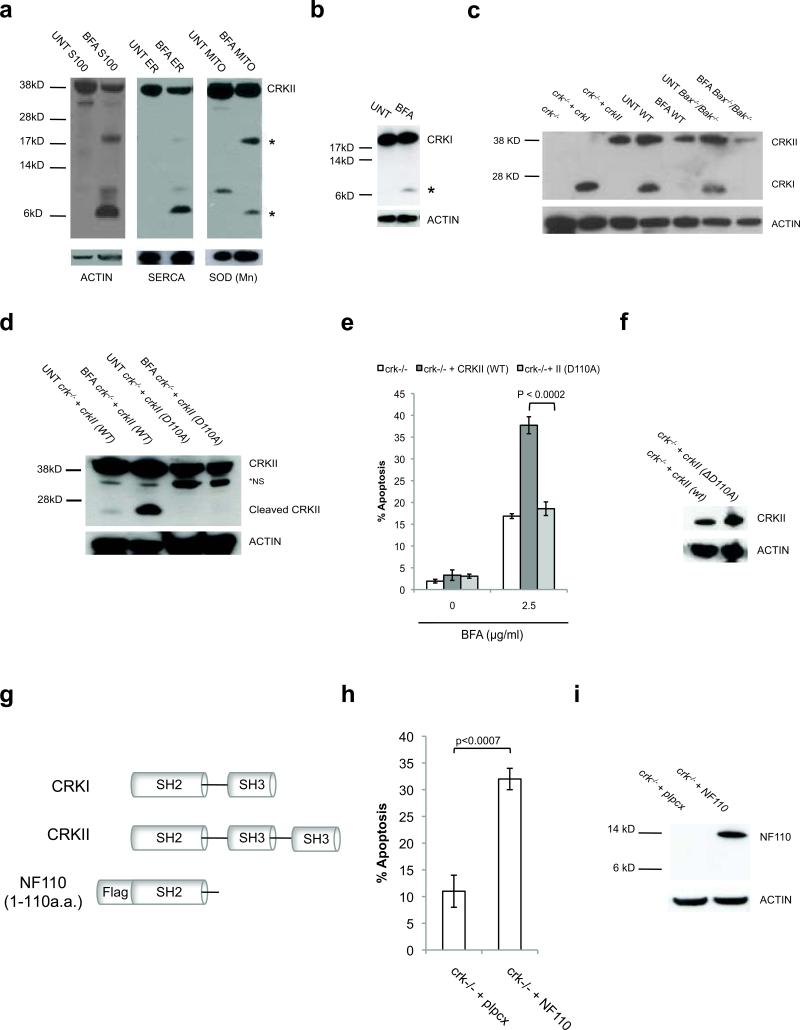

To explore its potential role in ER stress, we monitored CRK mRNA and protein following BFA treatment (Supplementary Fig. S1). We detected no changes in CRKI or CRKII mRNA transcript levels upon ER stress (Supplementary Fig. S1). However, we found that ER stress causes depletion of full-length CRKII (Supplementary Fig. S2). To determine if CRKII is reduced in a specific subcellular compartment, we probed subcellular fractions from Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs and found that CRKII is partially localized to the ER, mitochondria, and cytosol (Fig. 4a). Moreover, upon ER stress, 38kD ER- and cytosol- localized CRKII is reduced, while levels of the mitochondrion-localized full-length CRKII change very little (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, we found that upon ER stress, CRKII appears to be sequentially cleaved at least twice, resulting in several distinct fragments (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. S3). Proteolytic cleavage is a post-translational modification recognized to activate other known pro-apoptotic proteins, such as BID, but had not been described previously for CRK21-24.

Figure 4. CRK is proteolytically cleaved into an apoptotic signal upon irremediable ER stress.

(a) Upon 24h BFA (2.5 μg/ml) treatment of Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs, full-length CRKII is depleted in the cytosol and at the ER. CRKII-specific fragments (*) appear in the cytosol, ER, and mitochondria. (b) Transiently expressed CRKI is also cleaved upon 24h BFA (2.5 μg/ml) treatment in crk-/- MEFs. * = CRKI-specific fragment. (c) Loss of full-length, endogenous CRKI and CRKII observed upon 18h BFA treatment of WT and Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs. (d) Upon ER stress, CRK is cleaved at D110. Mutation of this site (D110A) in CRKII prevents cleavage following 24h 2.5 μg/ml BFA treatment in stably reconstituted in crk-/- MEFs. (e, f) CrkII (D110A) is not able to rescue crk-/- MEF sensitivity to ER stress-induced apoptosis induced by 24h 2.5 μg/ml BFA, in contrast to crk-/- MEFs stably expressing wild-type (WT) CRKII. n=3, error bars = sd. (g) Diagram of CRK (1-110a.a.) cleavage fragment (NF110) produced upon ER stress. (h, i) Transient expression of NF110 induces apoptosis independent of ER stress. n=3, error bars = sd.

We tested if CRKI also undergoes cleavage events upon ER stress. Following ER stress, at least one CRKI-specific cleavage product is readily observed (Fig. 4b). In addition, we observe depletion of full-length endogenous CRKI and CRKII in both WT and Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs upon BFA treatment (Fig. 4c), indicating that their cleavage occurs upstream of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Furthermore, the loss of full-length CRKI and CRKII occurs only when the level of ER stress rises to cytotoxic levels, and correlates with the initiation of ER stress-induced apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S4)25-28.

In an attempt to determine the role of CRK cleavage for its apoptotic activity, we tested a small panel of protease inhibitors for their ability to block this event (data not shown). We found that the pan-cysteine protease inhibitor ZVAD-FMK prevents ER stress-induced loss of full-length CRKI and CRKII and protects Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs from the cytopathic effects of ER stress (Supplementary Fig. S5). We previously identified caspase-2 as a pre-mitochondrial cysteine protease activated by ER stress10. However, caspase-2 is poorly inhibited by ZVAD-FMK and in vitro experiments with recombinant caspase-2 do not result in CRK cleavage (data not shown). These data suggest that a previously unidentified ER stress-activated cysteine protease is responsible for CRK cleavage.

To determine if the observed ER stress-induced cleavage of CRK is critical for its apoptotic activity, we individually mutated each potential cysteine protease cleavage site (aspartic acid) in the CRK sequence. When stably reconstituted into crk-/- MEFs, CRKII ΔD110A (crk-/- +crkII (ΔD110A)) was the only aspartic acid mutant unable to be cleaved in response to ER stress (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, non-cleavable CRKII ΔD110A is defective in restoring crk-/- MEF sensitivity to ER stress-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4e, f), arguing that this cleavage event is critical for its apoptotic activity. Cleavage at D110 is predicted to produce one fragment of approximately 25kD, which can be detected by a C-terminal-specific antibody (Fig 4d), and a second N-terminal fragment of ~14kD, which is undetectable using available antibodies. As both CRKI and CRKII restore crk-/- sensitivity to ER stress, it is likely the shared N-terminal fragment (~14kd) contains the critical domain for its apoptotic function. To test this prediction, we transiently expressed the N-terminally FLAG-tagged fragment (NF110) in the absence of ER stress (Fig. 4g) and measured apoptosis. As predicted, NF110 is able to potently induce cell death independently of ER stress (Fig. 4h, i). From these data, we conclude that CRK is cleaved upon ER stress at D110, to produce a pro-apoptotic fragment. Further studies will be necessary to identify the upstream protease and its connection to the unfolded protein response pathway.

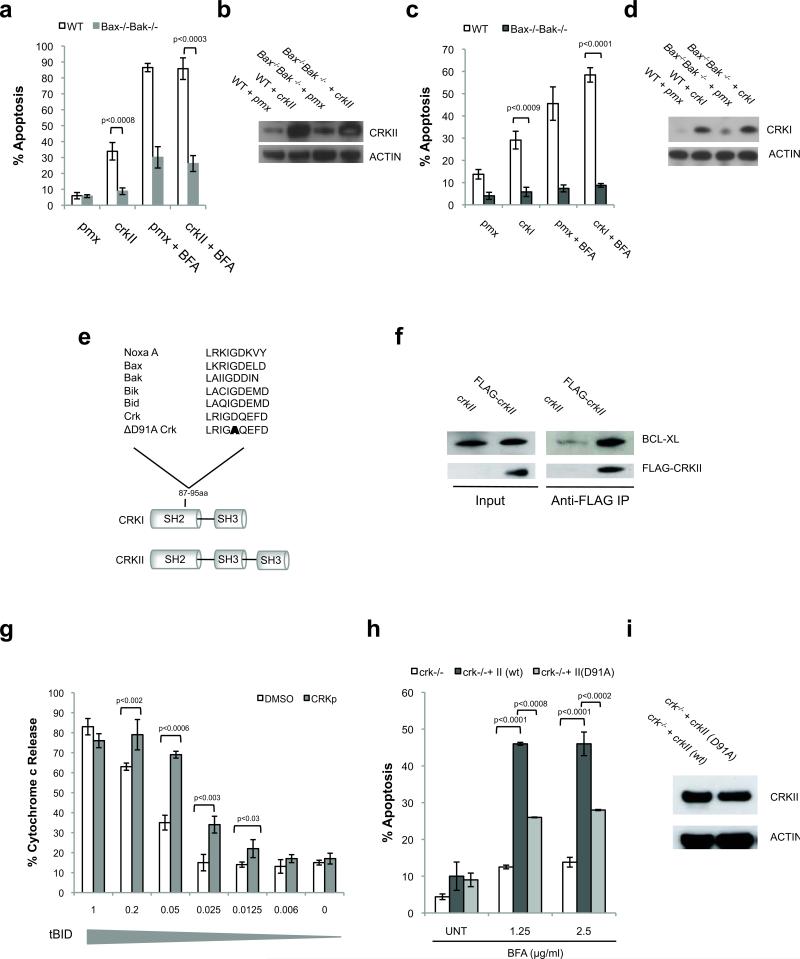

To further investigate the mechanism by which CRK triggers cell death, we tested if CRK-induced apoptosis is a BAX/BAK-dependent process. Transient overexpression of CRKI or CRKII triggers apoptosis in WT MEFs, but not Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs, confirming that both isoforms signal upstream of the BAX/BAK-dependent mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (Fig. 5a-d). Pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins are the only known molecules capable of activating BAX and/or BAK either directly or by inhibiting anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins4,13. Through sequence analysis, we identified a putative BH3-like domain within CRK that contains a number of conserved amino acids present in several recognized BH3-only proteins (Fig. 5e). This sequence is present in both crk splice forms and located within the common N-terminal 110 a.a. pro-apoptotic fragment (Fig. 1d, 5e). In support of our hypothesis that CRK contains a BH3-like domain, we determined that CRK is capable of binding a prototypical anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family protein (BCL-XL), a common feature of most BH3-only proteins. Following ER stress induction, transiently expressed FLAG-CRKII co-immunoprecipitates with BCL-XL on FLAG-specific agarose beads (Fig. 5f).

Figure 5. CRKII contains a putative BH3 domain and triggers BAX/BAK-dependent apoptosis.

(a, b) CRKII and empty vector (pmx) were transiently overexpressed in WT and Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs using retroviral infection. 24h post retroviral infection cells were treated with BFA (2.5 μg/ml) for an additional 24h and analyzed for Annexin-V expression by flow cytometry. n=3, error bars = sd. (c, d) CRKI and empty vector (pmx) were transiently overexpressed in WT and Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs. 24h post transfection cells were treated an additional 18h with BFA (2.5 μg/ml) and analyzed for Annexin-V expression by flow cytometry. n=3, error bars = sd. (e) The sequences of the putative BH3-only domain of CRK and the “BH3 domain” point mutation D91A are aligned against BH3 domains of several known BH3-only proteins. (f) 293 cells were transiently transfected 24h with Flag-crkII or untagged crkII, then treated 14h BFA (1.25μg/ml). Lysates were incubated with FLAG-specific agarose beads. Beads were immunoblotted for endogenous BCL-XL. (g) Cytochrome c release from isolated Jurkat mitochondria incubated with decreasing doses of tBID and CRK BH3 domain peptide. n=3, error bars = sd. (h, i) Stable reconstitution of D91A crkII into crk-/- MEFs is significantly less effective at restoring ER stress-induced apoptosis (24h BFA treatment) in comparison to expression of wild-type crkII. n=3, error bars = sd.

To determine if this sequence has BH3-like pro-apoptotic activity, we treated isolated Jurkat mitochondria with a synthetic CRK BH3 domain (77-96 a.a.) and measured cytochrome c release. There are two classes of BH3-only domains, those that sensitize or activate BAX/BAK-dependent mitochondrial apoptosis29. BH3 domains that directly “activate” BAX and/or BAK at mitochondria, such as the BH3 domain of BID, are able to cause cytochrome c release from isolated mitochondria. In contrast, “sensitizing” BH3 domains, such as the BH3 domains of BAD and BIK, sensitize isolated mitochondria to release cytochrome c in the presence of a second “activating” BH3 domain. In vivo, sensitizer BH3-only proteins are thought to competitively bind anti-apoptotic proteins, releasing bound “activating” BH3-only proteins to induce mitochondrial permeability. While the CRK BH3 domain is unable to induce cytochrome c release alone, it significantly potentiates with low concentrations of truncated BID (tBID) to cause cytochrome c release (Fig. 5g).

To further examine if this putative BH3 domain is required for CRK's pro-apoptotic activity in cells, we mutated the highly conserved aspartic acid (D91A) in crkII and evaluated the ability of this mutant to rescue the crk-/- MEF phenotype. In comparison to wild-type crk, the BH3 mutant crk (D91A) has significantly decreased apoptotic activity, arguing that this region is critical for its pro-death signaling (Fig. 5h, i).

Together, these results identify CRK as a major pro-apoptotic signal required for the execution of ER stress-induced cell death. During ER stress, CRKI and CRKII are cleaved by a yet to be identified cysteine protease to generate an N-terminal fragment with potent apoptotic activity. Furthermore, CRK interacts with anti-apoptotic BCL-XL and its apoptotic activity is upstream of the BAX/BAK-dependent mitochondrial pathway. Both CRK isoforms contain a putative BH3 domain, which sensitizes isolated mitochondria to tBID-induced cytochrome c release and when mutated diminishes apoptotic activity in cells. These data argue that CRK is a previously unidentified BH3-only-like protein, which upon ER stress is proteolytically processed into a pro-death signal. Our findings suggest that CRK may be a valuable therapeutic target in diseases where ER stress-induced cell loss is implicated, including some forms of neurodegeneration and diabetes1,2.

We have identified a previously unknown pro-apoptotic function common to both CRK isoforms. CRK was initially identified through its homology with transforming v-crk7,30,31. However, only CRKI has been shown to have transforming activity in some cell culture models, and it is upregulated in a number of human cancers32,33. Clues that CRK mediates apoptosis are present in other species. For example, the C. elegans Crk-homologue CED-2 regulates apoptotic engulfment34,35. Mammalian CRKII has been reported to induce death in some transformed cell types upon overexpression36,37 and is required for apoptotic activity that can be detected in Xenopus egg extracts38-40. Our work is the first to connect CRK to apoptosis, specifically under ER stress, in mammalian cells.

In addition to the shared pro-apoptotic function we have discovered for CRKI and CRKII, there are notable and possibly functionally significant differences between the isoforms. Our inability to establish a cell line stably overexpressing CRKI, in contrast to multiple cell lines stably overexpressing CRKII, suggests that CRKI may be the more cytotoxic isoform. Indeed, the expression of endogenous CRKI is restricted to approximately 10% that of CRKII (Supplementary Fig. S1), perhaps to limit its toxicity. In support of this notion, we observe that CRKI is cleaved more efficiently and at earlier kinetics than CRKII in response to ER stress (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. S4). These observations and our discovery that CRKI can be converted into a pro-apoptotic protein in response to ER stress raise the possibility that pharmacologic inducers of ER stress may have therapeutic efficacy in cancers where crkI is upregulated.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Don Ganem, Feroz Papa, and Warner Greene for scientific advice and encouragement throughout this project. We thank Christine Lin for help in preparing figures for the manuscript. We thank Courtney Crane for qPCR assistance. We thank Dick Winant at the Stanford PAN facility and Nevan Krogan and Gerard Cagney, UCSF, for mass spectrometry analysis of purified samples. This work was supported by NIH grants K08 AI054650 and RO1 CA136577 (S.A.O.); an HHMI Physician-Scientist Early Career Award (S.A.O.); the Steward Trust Foundation (S.A.O.); and the Sandler Program in Basic Sciences (S.A.O.). This work was also supported by a Pennsylvania Department of Health Cure Formulary grant (SAP#4100047628 to T.C.).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cellular Fractionation and Cytochrome c Release Assay

MEFS were resuspended in mitochondria isolation buffer (200mM sucrose, 10mM Tris/MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) [pH 7.4], 1mM EGTA) plus 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC, Sigma) and manually disrupted by shearing the suspension 10x through a 27-gauge and then 10x through a 30-gauge needle. Mitochondria (heavy membrane) were isolated from the suspension with an initial 700×g 4°C centrifugation to remove nuclei, followed by a 7000×g 4°C centrifugation to isolate heavy membrane (mitochondrial) fraction. The endoplasmic reticulum (light membrane) was isolated from the cytosolic fraction (S100) by a 100,000×g 4°C centrifugation. Mitochondrial and ER fractions were resuspended in RIPA (150mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% DOC, 0.1% SDS, 50mM Tris [pH 8.0]). S100 was dialyzed for 2 hours into 10% glycerol-containing mitochondria experimental buffer (MEB; 125mM KCl, 10mM Tris/MOPS [pH 7.4], 5mM glutamate, 1.25mM malate, 2μM EGTA, 1μM KPhos). Jurkat mitochondria for the cytochrome c releasing assay were isolated as described above, minus the second shearing through the 30-gauge needle. For the cytochrome c releasing assay reaction, 100-200μg (sample dependent) of S100 extract was incubated with 50μg of isolated Jurkat mitochondria for 45 minutes at room temperature. Following the incubation, the supernatant and pellet were separated by a 4°C 16,000×g centrifugation. The remaining cytochrome c was released from mitochondria by resuspending the pellet in PBS plus 0.05% Triton-X. The amount of cytochrome c present in the supernatant and lysed pellets was quantified using a human cytochrome c linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)(R&D systems) per the manufacturer's instructions. The percentage of cytochrome c release was calculated by dividing the amount of cytochrome c present in the supernatant by the sum of cytochrome c present in both the supernatant and pellet fractions.

Purification of Cytochrome c Releasing Activity

The ER stress apoptotic factor was purified using the CcRA assay described above utilizing an AKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare). Briefly, 804mg of S100 protein isolated from 24h BFA (2.5 μg/ml) treated Bax-/-Bak-/- MEFs was initially precipitated with 40-80% saturated ammonium sulfate. This active fraction was then further purified on a Phenyl Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) by loading in 1M Ammonium Sulfate and eluting with a 100mM Na2HPO4 – 100mM Na2HPO4 gradient. The CcRA eluted in the 100.925-62.875ms/cm range and was further purified on a MonoP column (GE Healthcare) gradient pH 6-10. The CcRA eluted between pH 9-6. This fraction was then purified further on the Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) and eluted in the 10-44kD range. This CcRA containing-fraction was run over a MonoQ column (GE Healthcare) 10mM KCl-1M KCl gradient. The purified CcRA fraction was analyzed in-gel and in-solution by MS-MS mass spectrometry by the UCSF Biomolecule Core Facility and the Stanford University of Medicine, Protein and Nucleic Acid Facility (PAN).

Cell culture and biological reagents

SV40 transformed Bax-/-Bak-/- and WT control MEFs were passaged as previously described17. Crk-/- and WT control MEFs were 3T3 immortalized. All MEFs were maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100U/ml penicillin, 100ug/ml streptomycin, 2mM glutamine, and nonessential amino acids (UCSF cell culture facility). Human Jurkat cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100U/ml penicillin, 100ug/ml streptomycin, 2mM glutamine, 100mM HEPES, and nonessential amino acids (UCSF cell culture facility). Annexin-V FITC was purchased from BioVision. Protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC), IPTG (isopropyl-4-D-thiogalactopyranoside), thapsigargin (TG), brefeldin A (BFA), staurosporine (STS), tunicamycin (TUN), and ZVAD-FMK were purchased from Sigma.

Antibodies and Western Blot analysis

Antibodies used for Western Blot analysis include anti-CRKII (Sigma)(1:1000), anti-CRK (BD Biosciences)(1:1000), anti-Mn SOD (assay designs)(1:500), anti-SERCA (affinity bioreagents)(1:1000), anti-BCL-XL (santa cruz technologies)(1:500), anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma)(1:1000) and anti-ACTIN (Sigma)(1:1000). Secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (anti mouse, anti-rat, and anti-rabbit antibodies) and Bio-Rad (anti-goat antibody)(1:2000).

Transient transfection and stable cell line selection

MEFs were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's instructions. 293 cells were transfected using Fugene6 (Promega) per the manufacturer's instructions. The crkI and crkII stable cell lines were made by transfecting a retroviral packaging line (293GPG or Phoenix) with pmx-crkI, pmx-crkII, and plpcx-crkII plasmids. Virus was harvested and titered from the supernatants of these packaging cell lines. Following infection with the virus, stable lines were isolated using 1.25μg/ml puromycin selection.

Plasmid Construction

C-terminal FLAG-crkII was cloned using the following primers: 5’-TTTGGATCCCGCCACCATGGCGGGCAACTTCGACTCGGAGGAG, 3’-AAAGCGGCCGCTCACTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTCGCTGAAGTCCTCATCGG G. Crk aspartic acid mutants were generated using Stratagene Quickchange Lightning Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit and the following primers; D39A (5’-GGTGTTCCTGGTGCGGGCCTCGAGCACCAGCCCCG, 3’-CGGGGCTGGTGCTCGAGGCCCGCACCAGGAACACC), D46A (5’-GAGCACCAGCCCCGGGGCCTATGTGCTTAGCG, 3’-CGCTAAGCACATAGGCCCCGGGGCTGGTGCTC), D110A (5’-CACTATTTGGCCACTACAACATTGATAGAACCAGTGGCC, 3’-GGCCACTGGTTCTATCAATGTTGTAGTGGCCAAATAGTG), D142A (5’-TGTCGGGCCCTCTTTGCCTTTATAGGGAATGATG, 3’-TCATTCCCATTAAAGGCAAAGAGGGCCCGCACA), D150A (5’-GGGAATGATGAAGAAGCTCTTCCCTTTAAGAAAGGAGAC, 3’-GTCTCCTTTCTTAAAGGGAAGAGCTTCTTCATCATTCCC), D157A (5’-CCCTTTAAGAAAGGAGCCATCCTGAGAATCCGGG, 3’-CCCGGATTCTCAGGATGGCTCCTTTCTTAAAGGG), D163A (5’-CCTGAGAATCCGGGCTAAGCCTGAAGAGCAGTGGTGG, 3‘-CCACCACTGCTCTTCAGGCTTAGCCCGGATTCTCAGG), D174A (5’-GTGGTGGAATGCAGAGGCCAGCGAAGGAAAGAGGG, 3’-CCCTCTTTCCTTCGCTGGCCTCTGCATTCCACCAC), D252A (5’-GCGAGTCCCTAATGCCTACGCCAAGACAGCCTTGGC, 3’-GCCAAGGCTGTCTTGGCGTAGGCATTAGGGACTCGC). N-terminal FLAG-tagged crk (110 a.a.) was cloned using 5’-CGGCCAAGCTTCGCCACCATGGACTACAAGGACGA and 3’-GGCCGGCGGCCGCTCAGTCCAAATAGTGTATTTTGTAG. Crk BH3 mutant was generated using Stratagene Quickchange Lightning Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit and these primers; 5’-CCCTCCAGGCTCCGAATAGCAGATCAAGAATTTGA, 3’-TCAAATTCTTGATCTGCTATTCGGAGCCTGGAGGG.

qPCR

Crk isoform mRNA levels were quantitated using qpCR. Sybrgreen (applied biosystems) was used to measure crk isoforms with primers designed to recognize only crkII (primer sequence: 5’-ATGGCGGGCAACTTCGACT, 3’-CATCGGGATTCTGTTGATCC). The amount of crkII mRNA was subtracted from total crk mRNA (primer sequence: 3’-CCCTCCTGGTTACCTCCAAT) in order to quantitate the amount of crkI mRNA present.

Annexin V staining and FACS analysis

Cells were harvested with 0.25% trypsin, washed once with 1x PBS, and incubated with Annexin V binding buffer (2 mM CaCl2, 80 mM NaCl, 1% HEPES plus 1μg/ml fluorescein isothiocyanate-annexin V) for 5 min. The cells were subsequently passed through a FACSCalibur machine (Becton Dickinson) and detected with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Statistical analyses were completed using Student's t test.

Immunoprecipitation

Approximately 2.5 × 104 293 cells were transiently transfected using Fugene (Roche) per manufacturer's protocol for 24h with 2μg of plasmid encoding crkII wild-type or N-terminal Flag-tagged crkII. These cells were then treated with 1.25μg/ml BFA for 12h. Cells were then trypsinized, lysed in RIPA (50mM Tris, 150mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Sodium Deoxycholate, 1% Triton X 100), and 200μg of whole cell lysate was incubated for 2h with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel beads (SIGMA). The FLAG affinity beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 1200rpm for 5 minutes. The reaction supernatant was removed and concentrated using microcon centrifugal filter devices (3,000 MWCO)(amicon). The beads were washed four times in 1x phosphate buffered saline. SDS-containing loading dye was added to both the concentrated supernatant and the beads. Samples were boiled for 8 minutes and run on a 10% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen). The transferred gel was immunoblotted for endogenous BCL-XL using anti-BCL-XL (santa cruz technologies)(1:500) and anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma)(1:1000).

CRK synthetic peptide

The CRK BH3 domain peptide was synthesized by ELIM biopharm. Sequence synthesized: QPPPGVSPSRLRIGAQEFDS.

BH3 mitochondria sensitization assay

Jurkat mitochondria were isolated as described above and resuspended in MEB. The indicated dilutions of recombinant truncated BID (tBID) and 100μM CRK BH3 domain peptide were incubated with 50μg of isolated Jurkat mitochondria for 45 minutes at room temperature. Following the incubation, the supernatant and pellet were separated by a 4°C 16,000×g centrifugation. The remaining cytochrome c was released from mitochondria by resuspending the pellet in PBS plus 0.05% Triton-X. The amount of cytochrome c present in the supernatant and lysed pellets was quantified using a human cytochrome c linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)(R&D systems) per the manufacturer's instructions. The percentage of cytochrome c release was calculated by dividing the amount of cytochrome c present in the supernatant by the sum of cytochrome c present in both the supernatant and pellet fractions.

Statistical Analysis

Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used to analyze flow cytometric and ELISA sample data.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.A. and E.T.J. designed and performed experiments and contributed to the manuscript. T-J.P and T.C. contributed reagents and data interpretation. S.A.O. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

None to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marciniak SJ, Ron D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in disease. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1133–1149. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin JH, Walter P, Yen TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:399–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shore GC, Papa FR, Oakes SA. Signaling cell death from the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oakes SA, Lin SS, Bassik MC. The control of endoplasmic reticulum-initiated apoptosis by the BCL-2 family of proteins. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:99–109. doi: 10.2174/156652406775574587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han D, et al. IRE1alpha kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell. 2009;138:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuda M, et al. Two species of human CRK cDNA encode proteins with distinct biological activities. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3482–3489. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du C, Fang M, Li Y, Li L, Wang X. Smac, a mitochondrial protein that promotes cytochrome c-dependent caspase activation by eliminating IAP inhibition. Cell. 2000;102:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Susin SA, et al. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell. 1996;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chipuk JE, Green DR. PUMA cooperates with direct activator proteins to promote mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2692–2696. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.17.9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strasser A. The role of BH3-only proteins in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:189–200. doi: 10.1038/nri1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lomonosova E, Chinnadurai G. BH3-only proteins in apoptosis and beyond: an overview. Oncogene. 2008;27(Suppl 1):S2–19. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Lee B, Lee AS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis: multiple pathways and activation of p53-up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) and NOXA by p53. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7260–7270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upton J-P, et al. Caspase 2 Cleavage of BID is a critical apoptotic signal downstream of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28:3943–3951. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00013-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsten T, et al. The combined functions of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members bak and bax are essential for normal development of multiple tissues. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00136-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei MC, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puthalakath H, et al. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 2007;129:1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feller SM. Crk family adaptors-signalling complex formation and biological roles. Oncogene. 2001;20:6348–6371. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park TJ, Boyd K, Curran T. Cardiovascular and craniofacial defects in Crk-null mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6272–6282. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00472-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94:491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo X, Budihardjo I, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Bid, a Bcl2 interacting protein, mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors. Cell. 1998;94:481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang K, Yin XM, Chao DT, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. BID: a novel BH3 domain-only death agonist. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2859–2869. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei MC, et al. tBID, a membrane-targeted death ligand, oligomerizes BAK to release cytochrome c. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2060–2071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee K, et al. IRE1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 2002;16:452–466. doi: 10.1101/gad.964702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7448–7459. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7448-7459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glimcher LH. XBP1: the last two decades. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(Suppl 1):i67–71. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.119388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee AH, Chu GC, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 is required for biogenesis of cellular secretory machinery of exocrine glands. EMBO J. 2005;24:4368–4380. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letai A, et al. Distinct BH3 domains either sensitize or activate mitochondrial apoptosis, serving as prototype cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayer BJ, Hamaguchi M, Hanafusa H. A novel viral oncogene with structural similarity to phospholipase C. Nature. 1988;332:272–275. doi: 10.1038/332272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayer BJ, Hamaguchi M, Hanafusa H. Characterization of p47gag-crk, a novel oncogene product with sequence similarity to a putative modulatory domain of protein-tyrosine kinases and phospholipase C. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1988;53(Pt 2):907–914. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1988.053.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller CT, et al. Increased C-CRK proto-oncogene expression is associated with an aggressive phenotype in lung adenocarcinomas. Oncogene. 2003;22:7950–7957. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sriram G, Birge RB. Emerging roles for crk in human cancer. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:1132–1139. doi: 10.1177/1947601910397188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tosello-Trampont AC, et al. Identification of two signaling submodules within the CrkII/ELMO/Dock180 pathway regulating engulfment of apoptotic cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:963–972. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tosello-Trampont AC, Brugnera E, Ravichandran KS. Evidence for a conserved role for CRKII and Rac in engulfment of apoptotic cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13797–13802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parrizas M, Blakesley VA, Beitner-Johnson D, Le Roith D. The proto-oncogene Crk-II enhances apoptosis by a Ras-dependent, Raf-1/MAP kinase-independent pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:616–620. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kar B, Reichman CT, Singh S, O'Connor JP, Birge RB. Proapoptotic function of the nuclear Crk II adaptor protein. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10828–10840. doi: 10.1021/bi700537e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith JJ, et al. Apoptotic regulation by the Crk adapter protein mediated by interactions with Wee1 and Crm1/exportin. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1412–1423. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.5.1412-1423.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith JJ, et al. Wee1-regulated apoptosis mediated by the crk adaptor protein in Xenopus egg extracts. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1391–1400. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans EK, Lu W, Strum SL, Mayer BJ, Kornbluth S. Crk is required for apoptosis in Xenopus egg extracts. EMBO J. 1997;16:230–241. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.