Abstract

The control of dNTP concentrations is critical to the fidelity of DNA synthesis and repair. One level of regulation is through subcellular localization of ribonucleotide reductase. In S. cerevisiae, the small subunit, Rnr2-Rnr4, is nuclear while the large subunit, Rnr1, is cytoplasmic. In response to S-phase or DNA-damage, Rnr2-Rnr4 enters the cytoplasm to bind Rnr1, forming an active complex. We previously reported that Wtm1 anchors Rnr2-Rnr4 in the nucleus. Here, we identify DIF1 which regulates localization of Rnr2-Rnr4. Dif1 binds directly to the Rnr2-Rnr4 complex through a conserved Hug domain to drive nuclear import. Dif1 is both cell cycle- and DNA-damage regulated, the latter through the Mec1-Dun1 pathway. In response to DNA damage, Dun1 directly phosphorylates Dif1 to both inactivate and degrade Dif1, allowing Rnr2-Rnr4 to become cytoplasmic. We propose that Rnr2-Rnr4 nuclear localization is achieved by a dynamic combination of Wtm1-mediated nuclear retention to limit export, coupled with regulated nuclear import through Dif1.

Introduction

In response to DNA replication blocks, cells activate the DNA damage and replication stress response pathway, the DDR, which includes the MEC1-RAD53-DUN1-CHK1 kinase cascade in budding yeast and the rad3-cds1-chk1 pathway in fission yeast. The downstream effects include cell cycle arrest, stabilization of replication forks, inhibition of late origin firing, and the initiation of DNA repair (Harper and Elledge, 2007). Part of this process involves activation of the ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) pathway – the rate-limiting step in the conversion of rNTPs to dNTPs. S. cerevisiae has a Class Ia RNR and is composed of homodimers of Rnr1 (α2) and heterodimers of structurally homologous Rnr2 and Rnr4 (ββ′) (Voegtli et al., 2001). The intimate relationship between the DDR pathway and RNR function is demonstrated by the fact that the lethality of the mec1Δ or rad53Δ mutants can be rescued by the activation of RNR pathway (Desany et al., 1998; Vallen and Cross, 1999; Huang et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 1998).

Adjusting the intracellular concentration of dNTPs to meet demands under different conditions is critical as both elevated or insufficient levels of dNTP can lead to increased mutagenesis rates (Chabes et al., 2003; Holmberg et al., 2005). Thus, cells have devised multiple strategies to regulate Rnr (Nordlund and Reichard, 2006). For example, transcriptional induction of the RNR genes in S. cerevisiae involves Dun1 phosphorylation and inactivation of the Crt1-Ssn6-Tup1 repressor complex (Huang et al., 1998; Zhou and Elledge, 1992). In addition, effectors binding the large subunit can alter the rate of catalysis or change the specificity of the enzyme toward particular ribonucleotide substrates (Reichard, 2002). Post-translational regulation in S. cerevisiae involves the Sml1 inhibitor, which can bind to the large subunit Rnr1 through its C-terminal tail (Chabes et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2000) and interfere with the regeneration of the catalytic site on Rnr1 (Zhang et al., 2007). Dun1 is required for Sml1 degradation in response to DNA damage. Dun1 can phosphorylate Sml1 in vitro but the consequences of this phosphorylation have not been examined in vivo (Zhao and Rothstein, 2002).

Rnr subcellular localization is an additional layer of control (Lincker et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2003; Xue et al., 2003; Yao et al., 2003). The Rnr small subunits of both S. pombe and S. cerevisiae are sequestered in the nucleus. S-phase and DNA damage can independently control the translocation of nuclear Rnr small subunits out to the cytoplasm, presumably to form active complexes with cytoplasmic Rnr1. We previously identified WTM1 as a regulator of Rnr2-Rnr4 localization (Lee and Elledge, 2006; Zhang et al., 2006). Wtm1 is a nuclear protein that binds to Rnr2-Rnr4. Their physical association is reduced after DNA damage and replication stress, coincident with the release of Rnr2-Rnr4 from the nucleus. Deletion of WTM1 causes a significant nuclear-to-cytoplasmic shift of Rnr2-Rnr4. Forced localization of Wtm1 to the nucleolus recruits Rnr2-Rnr4 to the nucleolus suggesting that Wtm1 functions as a nuclear anchor. How DNA damage regulates this association is unknown. In S. pombe, deletion of the spd1 gene causes mis-localization of the nuclear RNR small subunit Suc22 (SpRnr2). In vitro experiments have demonstrated that Spd1 binds to the RNR large subunit Cdc22 (SpRnr1) but not to the small subunit SpRnr2 (Hakansson et al., 2006). Whether and how this binding between Spd1 and the large RNR subunit results in nuclear localization of the small subunit is unknown.

Here, we describe the discovery of the S. cerevisiae DIF1 (Damage-regulated Import Facilitator 1) that mediates the localization of Rnr small subunits in response to DNA damage. Dif1 shares elements of different Rnr regulators and provides a unified view of Rnr localization regulation.

Results

Dif1 has a conserved domain present among Rnr-inhibitor homologs in yeasts

Wtm1 binding to Rnr2-Rnr4 is disrupted in response to DNA damage, resulting in their cytoplasmic localization. We sought to understand how this regulation was accomplished. As the upstream regulators are protein kinases, we identified three phosphorylation sites on Rnr2: S15, S22, and S41. However, mutation of these sites did not alter the nuclear localization. Therefore, we initiated a search for additional regulators.

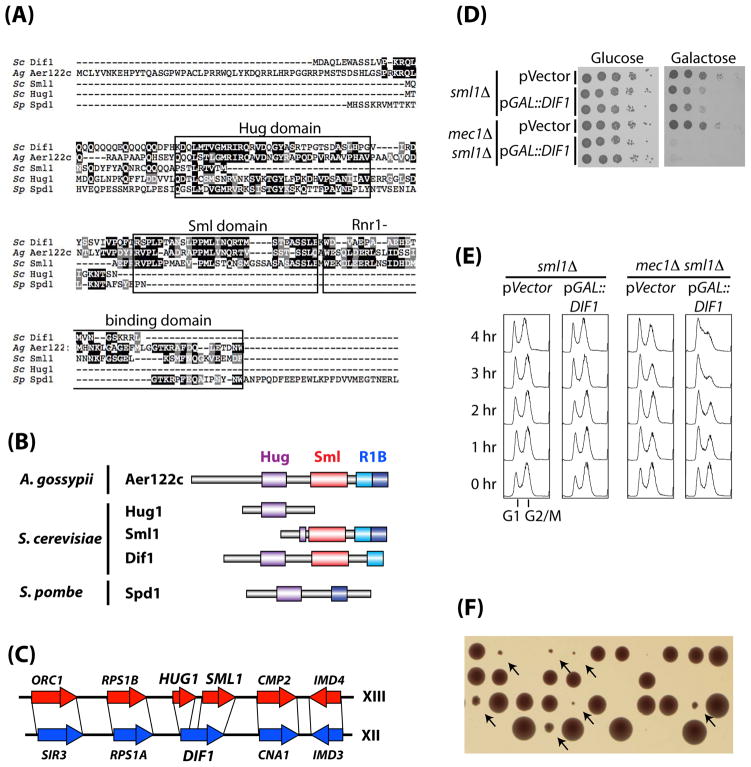

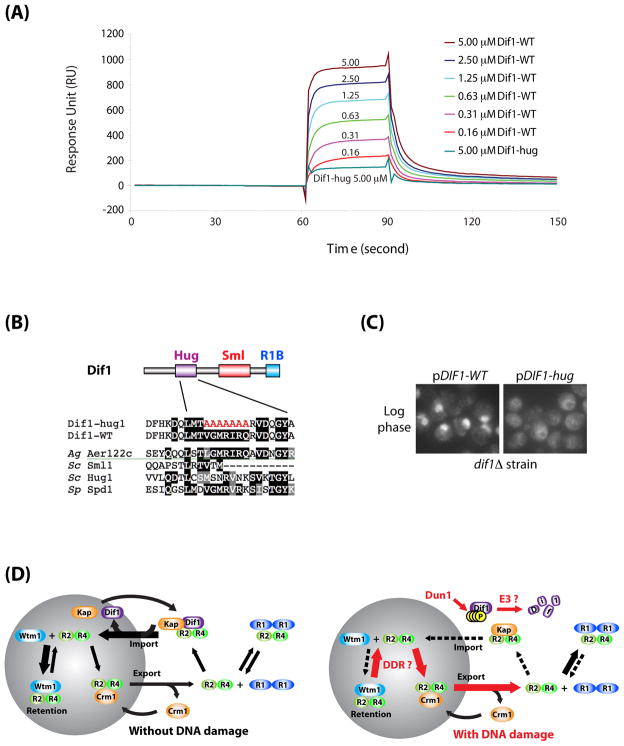

S. cerevisiae Sml1 and S. pombe Spd1 proteins are small inhibitors of the RNR pathway that both bind the Rnr large subunit (Hakansson et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 1998). However, Spd1 and Sml1 appear unrelated. Furthermore, while Spd1 is essential for the nuclear localization of the Rnr small subunit Suc22 (Liu et al., 2003), Sml1 plays no such role in S. cerevisiae (Yao et al., 2003). It was thought that there was no Spd1 ortholog in budding yeast. However, using the N-terminal half of the Spd1 sequence as a query, we identified two proteins with sequence similarity. One was Hug1, a 7.5 kD protein that is highly induced after DNA damage and is thought to play a role in feedback inhibition of the RNR pathway through an unknown mechanism (Basrai et al., 1999). Its genomic sequence is located immediately 5′ of SML1. The second candidate is a novel uncharacterized protein YLR437c (hereafter referred to as DIF1, for Damage-regulated Import Facilitator). BLAST analysis using Dif1 identified similarity to Sml1. Alignment of Dif1, Spd1, Sml1, Hug1, and Aer122c (a Dif1/Sml1 ortholog in Ashbya gossypii) revealed a conserved domain we named the Hug domain, which is present in all homologs except for Sml1 (Figure 1A, 1B). We also observed a second domain conserved in Dif1, Aer122c, and Sml1, which we call the Sml domain. Aer122c, Sml1, and to a lesser extent, Spd1 share yet a third domain in their C-termini which we call the Rnr1-binding (R1B) domain because it contains residues required for Sml1 binding to Rnr1 (Zhao et al., 2000).

Figure 1. Dif1 is an inhibitor of S-phase cell cycle progression and a paralog of Sml1.

(A) Sequence alignment between S. cerevisiae (Sc) Dif1, Sml1, Hug1, and S. pombe (Sp) Spd1, and A. gossypii (Ag) Aer122c. The three conserved domains: the Hug domain, the Sml domain, and the Rnr1-binding domain, are boxed. (B) Simplified diagrams showing the three different domains of the orthologs of Dif1. The Rnr1-binding domain (R1B) domain, which has been characterized through mutational analysis, was further divided into an N-terminal (cyan) and a C-terminal (blue) sub-domains. (C) Synteny in the proximity of the HUG1/SML1 loci on chromosome XIII and the DIF1 (YLR437c) locus on chromosome XII in S. cerevisiae. (D) sml1Δ and mec1Δ sml1Δ strains containing vector alone or a galactose-inducible DIF1 plasmid (pGAL1::DIF1) were serially diluted and spotted on glucose and galactose media. (E) Cell cycle profiles of sml1Δ and mec1Δ sml1Δ strains over-expressing DIF1. Cells were grown to log phase in glucose before being switched to galactose. Samples were taken from 0 to 4 hours after the galactose switch for FACS analysis of DNA content. (F) Tetrad dissection of MEC1/mec1Δ::his5+ DIF1/dif1Δ::TRP1 diploid. Arrows mark small colonies, which are HU-sensitive and tryptophan- and histidine-prototrophic (data not shown).

The relationship between Dif1 and Sml1 suggests evolution from a common ancestral gene. As S. cerevisiae underwent a genome duplication during its evolution, we searched for synteny surrounding HUG1, SML1, and DIF1. As shown in Figure 1C, Dif1 and Hug1-Sml1 are paralogs derived from an ancestral gene duplication event that included multiple adjacent genes (Dietrich et al., 2004; Kellis et al., 2004). We assume the ancestral gene is most similar to the ortholog from A. gossypii as it contains only one gene that shares homology to Dif1, Hug1 and Sml1. Duplication and divergence would allow the splitting of the ancestral gene into three genes – DIF1 on chromosome XII, and HUG1 and SML1 on chromosome XIII.

DIF1 dosage regulates the viability of mec1Δ mutants

To test whether Dif1 is a negative regulator of the RNR pathway, we over-expressed DIF1 under GAL1 control in mec1Δ sml1Δ and sml1Δ strains. Dif1 over-expression slowed growth in sml1Δ cells but was lethal to the mec1Δ sml1Δ cells (Figure 1D). Dif1 over-expression also rendered dun1Δ mutants more HU-sensitive (data not shown). Strains were switched from glucose to galactose to induce Dif1 expression and analyzed for DNA content by FACS. mec1Δ sml1Δ cells over-expressing Dif1 arrested in S-phase (Figure 1E), consistent with a role in negative regulation of RNR.

Up-regulation of RNR activity can suppress the lethality of the MEC1 deletion (Desany et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 1998) Whereas tetrad dissection of a MEC1/mec1Δ diploid always resulted in only two viable spores, dissection of the MEC1/mec1Δ::his5+ DIF1/dif1Δ::TRP1 tetrads yielded many viable 3 or 4 spore tetrads. In these, one or two colonies were significantly smaller and were mec1Δ::his5+ dif1Δ::TRP1 (data not shown) (Fig. 1F).

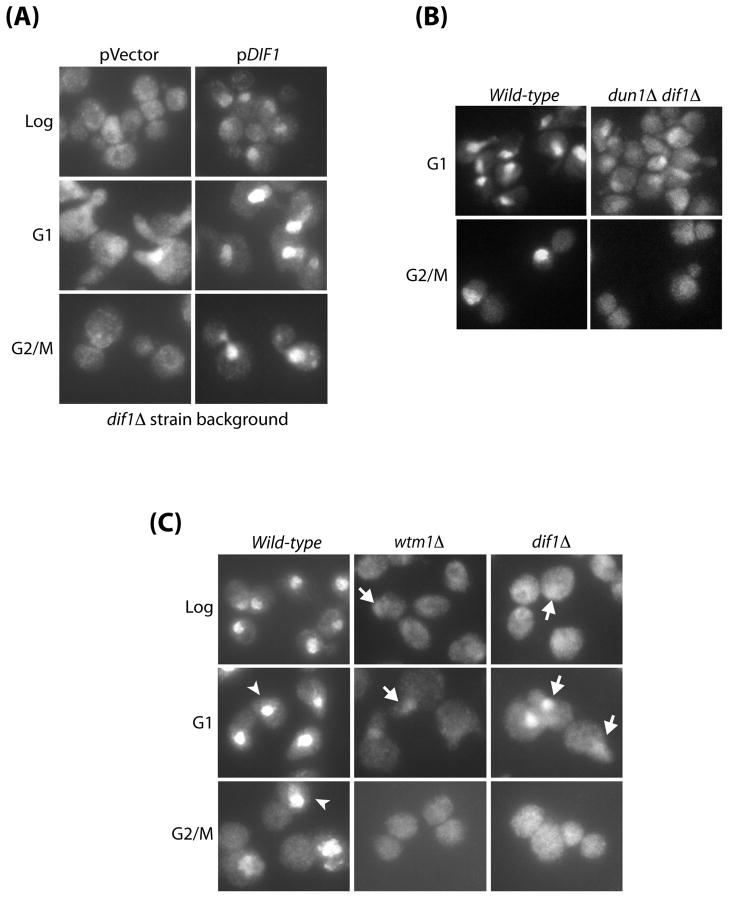

Dif1 is required for Rnr2-Rnr4 nuclear localization

DIF1 is non-essential and its deletion has no effect on Rnr protein levels (data not shown). However, dif1Δ mutants show cytoplasmic localization of Rnr2 independent of cell cycle stage (Figure 2A). Since Rnr2-Rnr4 is released from the nucleus in response to DNA damage or replication stress, the cytoplasmic localization in dif1Δ mutants could be indirect. To examine this, we generated dun1Δ dif1Δ mutants which still showed cytoplasmic Rnr2 (Figure 2B), indicating that Dif1 does not mis-localize Rnr2 by mimicking DNA damage.

Figure 2. Dif1 is required for the nuclear localization of Rnr small subunits.

(A) dif1Δ strains complemented with either vector alone or with a plasmid containing the wild-type DIF1 gene were grown to log-phase, or arrested in G1 with α-factor, or arrested in G2/M with nocodazole. Cells were processed for Rnr2 visualization by indirect immunofluorescence. (B) G1- or G2/M-arrested wild-type and dun1Δ dif1Δ strains were processed for Rnr2 visualization by indirect immunofluorescence. (C) Comparison of Rnr2 localization in wild-type, wtm1Δ, and dif1Δ mutants. Cells were either grown to log phase, arrested in G1 or arrested in G2/M. Samples were processed for Rnr2 visualization by indirect immunofluorescence. Examples of cells with strong nuclear Rnr2 staining are marked with white arrowheads, and cells with partially nuclear Rnr2 staining are marked with white arrows.

While Rnr2 mis-localization in dif1Δ mutants is cell cycle independent, α-factor arrested dif1Δ mutants showed significant residual nuclear Rnr2. We have previously shown that the protein Wtm1 is required for the nuclear localization of Rnr2-Rnr4 through an anchoring mechanism (Lee and Elledge, 2006; Zhang et al., 2006). We examined the localization phenotype of wtm1Δ and dif1Δ mutants. Both mutants showed very similar defects in Rnr2 nuclear localization with some residual nuclear Rnr2, especially in G1 (Figure 2C), suggesting they may work in the same pathway.

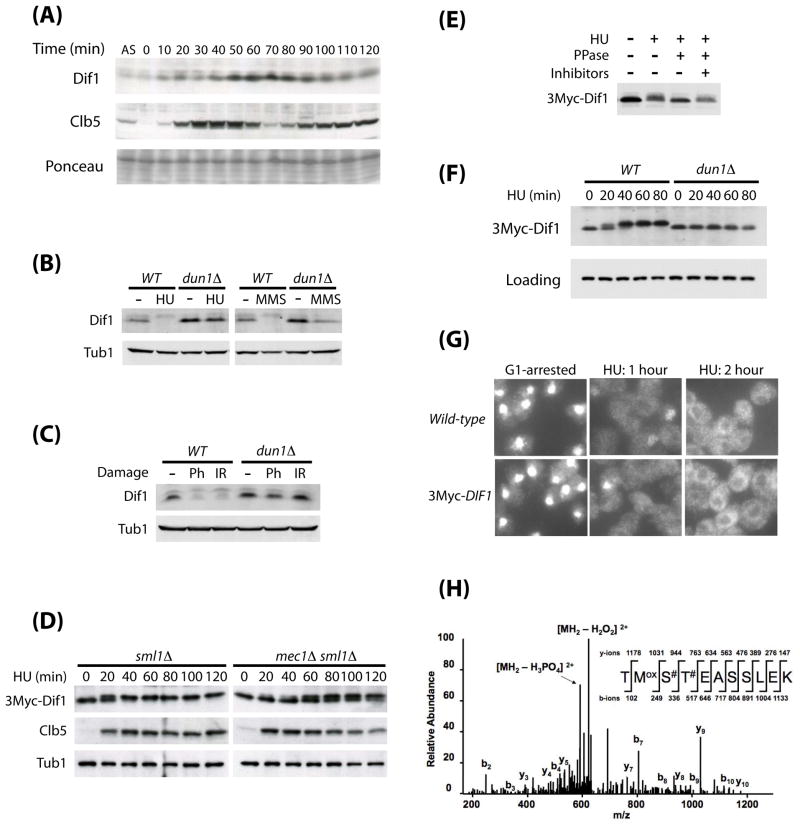

Dif1 is the regulated component of the Rnr2-Rnr4 localization switch

A key question with respect to control of Rnr subcellular localization has been the identity of the molecule that imparts cell cycle and DNA damage regulation on the switch. To examine whether Dif1 might be that molecule, we generated Dif1 antibodies. Western blot analysis showed that Dif1 levels peaked at approximately 70 minutes after the release from α-factor arrest with an inverse relationship to the levels of Clb5, a S-phase marker (Figure 3A). The low levels of Dif1 during S-phase coincided with Rnr2-Rnr4 release from the nucleus. A significant decrease in Dif1 abundance was also observed when log-phase cells were treated with HU or MMS, also coinciding with Rnr2-Rnr4 release. This damage-induced reduction in Dif1 levels is dun1Δ-dependent (Figure 3B). To separate the cell-cycle-induced reduction of Dif1 from the DNA damage-induced reduction of Dif1, cells were first arrested in G2/M-phase by nocodazole and then treated with phleomycin or ionizing radiation (IR) while maintaining G2/M-arrest. Under these conditions, phleomycin and IR also reduced the abundance of Dif1 in a Dun1-dependent manner (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Dif1 is regulated during cell cycle and DNA damage response.

(A) Cell cycle analysis of Dif1 abundance. Cells arrested in G1 by alpha factor were released into the cell cycle. Samples were collected at 10-minute intervals for western blotting of Dif1. Clb5 was used to monitor cell cycle progression. Ponceau staining served as a loading control. A log-phase sample from an asynchronous (AS) population of cells was loaded in the first lane for comparison. (B) Western blot analysis of Dif1 from log-phase wild-type (WT) and dun1Δ cells treated with HU (150 mM, 1.5 hours) or MMS (0.1%, 1.5 hours). Tubulin (Tub1) serves as a loading control. (C) Western blot analysis of Dif1 from wild-type (WT) and dun1Δ cells treated with phleomycin (Ph, 50 ng/mL, 1 hour) or ionizing radiation (IR, 20 kRad, 1-hour irradiation) while maintained in G2/M-arrest. (D) Cell cycle-dependent post-translational modification of 3Myc-Dif1 in sml1Δ and mec1Δ sml1Δ cells. Cells with a single copy of 3Myc-DIF1 integrated at the endogenous locus were arrested in G1 by α-factor, and then released into the cell cycle in the presence of HU (150 mM). Samples were collected at 20-minute intervals for western analysis of 3Myc-Dif1 mobility and abundance. Clb5 was used to monitor cell cycle progression. (E) Phosphatase (PPase) treatment of 3Myc-Dif1. Log-phase yeast cells carrying an integrated 3Myc-DIF1 were treated with HU (150 mM, 1.5 hours). 3Myc-Dif1 was immunoprecipitated from the lysate, and subjected to phosphatase treatment (PPase), with or without phosphatase inhibitors. (F) Dun1-dependent Dif1 phosphorylation after HU-treatment. Wild-type and dun1Δ strains with an integrated 3Myc-DIF1 were arrested in G1 by α-factor, and then released into HU media (150 mM). Samples were collected at 20-minute intervals for western analysis of 3Myc-Dif1 mobility and abundance. (G) Rnr2 visualization by indirect immunofluorescence of wild-type or a 3Myc-DIF1 integrated strain arrested in G1-phase with α-factor, and then released into HU media (150 mM) for 1 and 2 hours. (H) Phospho-mapping of 3Myc-Dif1. Log phase cells with an integrated 3Myc-DIF1 were treated with HU (150 mM, 1.5 hours). 3Myc-Dif1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibodies, resolved and silver stained on SDS-PAGE, and excised for phospho-mapping by mass spectrometry. The “#” signs indicate two potential sites for phosphorylation.

Dif1 is phosphorylated after hydroxyurea treatment

We observed that N-terminal tagging of endogenous Dif1 with 3Myc led to an increase of the Dif1 protein abundance. As early as 20 minutes after the release of the sml1Δ strain from G1 into HU, 3Myc-Dif1 was observed to migrate as a doublet (Figure 3D). However, in the mec1Δ sml1Δ mutant, the shift of 3Myc-Dif1 from lower to higher mobility was delayed by as much as 40–60 minutes and never reached completion even after 2 hours, compared with 40 minutes for WT. HU treatment does not reduce the 3Myc-Dif1 levels indicating that WT Dif1 is destroyed in response to HU but 3Myc-Dif1 is stabilized.

The mobility shift of 3Myc-Dif1 in response to DNA damage suggested possible phosphorylation. Phosphatase (PPase) treatment of 3Myc-Dif1 from HU-treated cells confirmed that the mobility shift was due to phosphorylation (Figure 3E).

The delayed phosphorylation of 3Myc-Dif1 in the mec1Δ sml1Δ mutant is most likely due to the redundant function of the Tel1 kinase, as the phosphorylation of Rad53 still occurs, although with a slower kinetics (data not shown). This Dif1 phosphorylation is not observed in dun1Δ mutants (Figure 3F), suggesting that Dun1 may directly phosphorylate Dif1.

To assess if 3Myc-Dif1 is inactivated after phosphorylation independent of degradation, G1-arrested 3Myc-DIF1 cells were released into 150 mM HU and examined for Rnr2 localization. The 3Myc-DIF1 strain showed a comparable degree of nuclear Rnr2 release as wild-type (Figure 3G), although the phosphorylated 3Myc-Dif1 protein is not efficiently degraded even after two hours of HU treatment (Figure 3D, 3F). Thus, degradation is not absolutely required for Rnr2 regulation and suggests that phosphorylation may be sufficient to inhibit Dif1 function.

The Sml domain of Dif1 is a phospho-degron

To identify potential phosphorylation sites on Dif1, a large-scale immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry analysis was carried out with lysates from HU-treated 3Myc-DIF1 cells. Phospho-mapping detected phosphorylation on S103 or T104 of the Sml domain (Figure 3H).

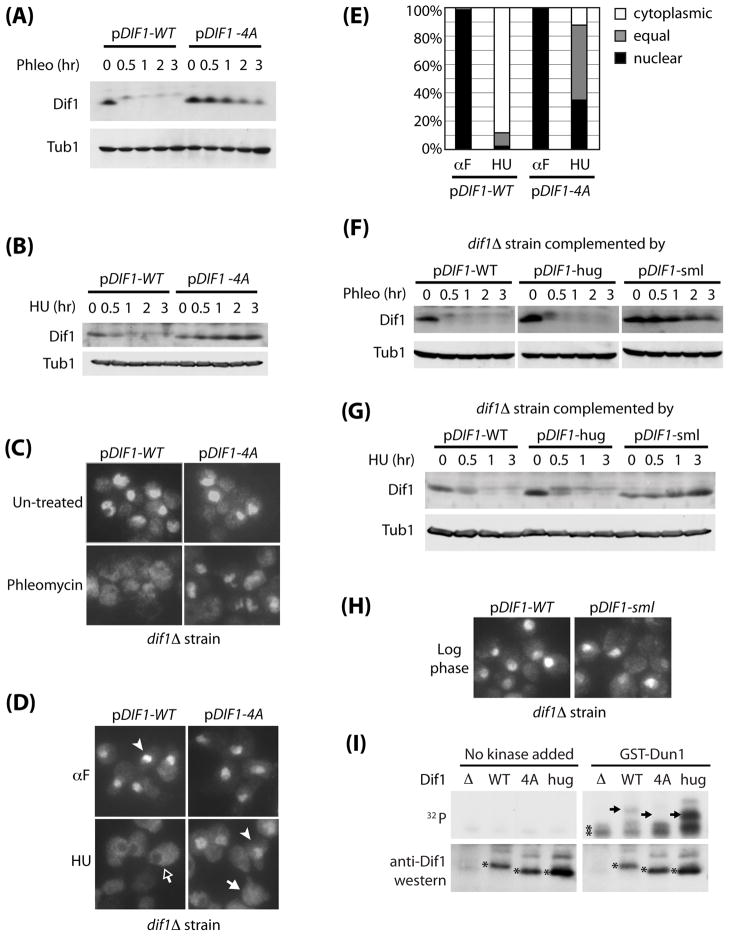

Sml1 can be phosphorylated by the Dun1 kinase in vitro and its degradation during S-phase and after DNA damage requires Dun1 (Uchiki et al., 2004; Zhao and Rothstein, 2002). To link Dif1 phosphorylation to its degradation, we mutated several of the mapped and conserved serine and threonine residues in the Sml domain to alanine. Dif1 carrying these single mutations showed no increase in protein stability after DNA damage or replication stress (data not shown). Therefore, we made a mutant Dif1 (DIF1-4A) consisting of the two residues mapped by mass spectrometry (S103 and T104) along with two highly conserved serine residues (S107 and S108) that are conserved in Sml1 and were shown to be phosphorylated by Dun1 in vitro (Uchiki et al., 2004). Dif1-4A was not degraded when G2/M arrested cells were treated with phleomycin (Figure 4A) or when G1 cells were released into the cell cycle in the presence of HU (Figure 4B) and Dif1-4A mutants were significantly impaired for the release of Rnr2-Rnr4 in both circumstances (Figure 4C, 4D, 4E).

Figure 4. The Sml and Hug domains have distinct roles in Dif1 regulation.

(A) Western blot analysis of wild-type and phospho-mutant Dif1 after phleomycin treatment. dif1Δ strains containing a wild-type DIF1 plasmid (pDIF1-WT), or the phospho-mutant plasmid (pDIF1-4A) were treated with phleomycin (50 ng/mL) for the indicated times during G2/M arrest by nocodazole. Tubulin (Tub1) serves as a loading control. (B) Western blot analysis of wild-type and phospho-mutant Dif1 from cells arrested in G1 by α-factor, and then released into HU-media (150 mM) for the indicated times. (C) G2/M-arrested wild-type and phospho-mutant Dif1 strains were treated with phleomycin for 2 hours and processed for Rnr2 visualization by indirect immunofluorescence. (D) Wild-type or phospho-mutant Dif1 cells were arrested in G1 by alpha-factor (αF) or released from G1 into HU (150 mM) for 1 hour and processed for Rnr2 visualization by indirect immunofluorescence. Examples of cells with Rnr2 staining that is predominately nuclear (white arrowhead), predominately cytoplasmic (black arrow), or equal in distributions (white arrow) are indicted. (E) Quantification of part D. For each treatment, more than 160 cells were counted (range: 161–200 cells). (F) Western blot analysis of wild-type, hug-domain mutant, or sml-domain mutant Dif1 after phleomycin treatment. dif1Δ strains complemented by plasmids containing wild-type (pDIF1-WT), hug-domain mutated (pDIF1-hug), or sml-domain mutated (pDIF1-sml) versions of DIF1 were treated with phleomycin (50 ng/mL) for the indicated times while maintained in G2/M. Tubulin (Tub1) serves as the loading control. (G) Western blot analysis of Dif1, Dif1-hug, Dif1-sml mutants after HU treatment. dif1Δ strains complemented by plasmids containing wild-type (pDIF1-WT), hug-domain mutant (pDIF1-hug), or sml-domain mutant (pDIF1-sml) versions of DIF1 were arrested in G1 by alpha-factor, and then released into HU media (150 mM) for the indicated times. (H) Rnr2 visualization by indirect immunofluorescence from log phase cultures of dif1Δ strains carrying pDIF1-WT or pDIF1-sml plasmids. (I). Dun1 in vitro kinase assay. Polyclonal anti-Dif1 antibodies were used to immuno-precipitate Dif1 from dif1Δ yeast strain complemented by plasmid alone (Δ), wild-type (WT), phospho-mutant (4A), and hug-domain mutant (hug) Dif1, and then incubated with or without recombinant GST-Dun1 purified from insect cells in the presence of [γ32-P] ATP. Bottom panel shows a western blot with anti-Dif1 antibodies. The predominant Dif1 bands are marked with single asterisks. The difference in their size is due to site-directed mutagenesis. Top panel shows autoradiograph, with the expected position of each Dif1 from the western blot marked by arrows. The non-specific bands present even in the dif1Δ sample was marked by double asterisks.

Since the degree of conservation is high throughout the Sml domain in addition to the serines and threonines mutated in Dif1-4A, we reasoned that a larger part of this domain may be required for the degron function. Therefore, we changed the most conserved residues PPMLINQRT in this domain to alanines while preserving the four phospho-serines/threonine residues and tested this mutant protein (Dif1-sml) for its stability during DNA damage response. As shown in Figures 4F and 4G, the Dif1-sml mutant protein failed to display a comparable mobility shift or reduction in protein level after HU or phleomycin treatment compared to wild-type Dif1 but maintained the ability to localize Rnr2-Rnr4 inside the nucleus (Figure 4H). Therefore, the Sml domain is required for the phosphorylation and degradation of Dif1 after DNA damage or replication stress.

Dif1 is directly phosphorylated by the Dun1 kinase

To determine whether Dun1 can directly phosphorylate Dif1, we purified GST-Dun1 from Baculovirus infected SF9 insect cells, and incubated it with different mutant Dif1 proteins in the presence of [γ-32P] ATP. As shown in Figure 4I, incubation of GST-Dun1 with wild-type Dif1 (Dif1-WT) and a Dif1 mutant altered in the HUG domain (Dif1-hug, see Figure 7 for details), but not phospho-mutant Dif1 (Dif1-4A), results in incorporation of 32P. This, together with the phospho-mapping data by mass spectrometry (Figure 3H), indicates that the Dun1 kinase can directly phosphorylate Dif1 on residues which leads to its inactivation and degradation.

Figure 7. Dif1 directly interacts with Rnr2-Rnr4.

(A) Binding between Dif1 and Rnr2-Rnr4 was detected using BIAcore. Purified Rnr2-Rnr4 was immobilized on the sensor surface. Recombinant wild-type Dif1 protein (Dif1-WT) flowed over the immobilized Rnr2-Rnr4 at the indicated concentrations. Recombinant Dif1-hug (Dif1-hug) protein flowed over the same sensor surface at a concentration of 5.0 μM (turquoise line). Binding between Rnr2-Rnr4 and Dif1 was measured in response units (RU). (B) Diagram of the amino acid changes in the Dif1-hug mutant. (C) Rnr2 visualization by indirect immunofluorescence from log phase cultures of dif1Δ strains carrying pDIF1-WT or pDIF1-hug plasmids. (D) Model demonstrating nuclear import and retention of Rnr2-Rnr4 in response to DNA damage. (Left) Dif1 facilitates the nuclear import of Rnr2-Rnr4, while Wtm1 functions as a nuclear anchor for Rnr2-Rnr4. In the absence of DNA damage, the net contribution of these two pathways leads to a net accumulation of Rnr2-Rnr4 inside the nucleus. (Right) Activation of the DNA damage response (DDR) leads to the phosphorylation, inactivation, and degradation of Dif1, reducing the nuclear import of Rnr2-Rnr4. DNA damage also releases the pool of nuclear Rnr2-Rnr4, either by decreasing the affinity between the Wtm1-Rnr2-Rnr4 interactions, or through an increased rate of Crm1-mediated Rnr2-Rnr4 nuclear export.

Dif1 is much less abundant than Rnr2

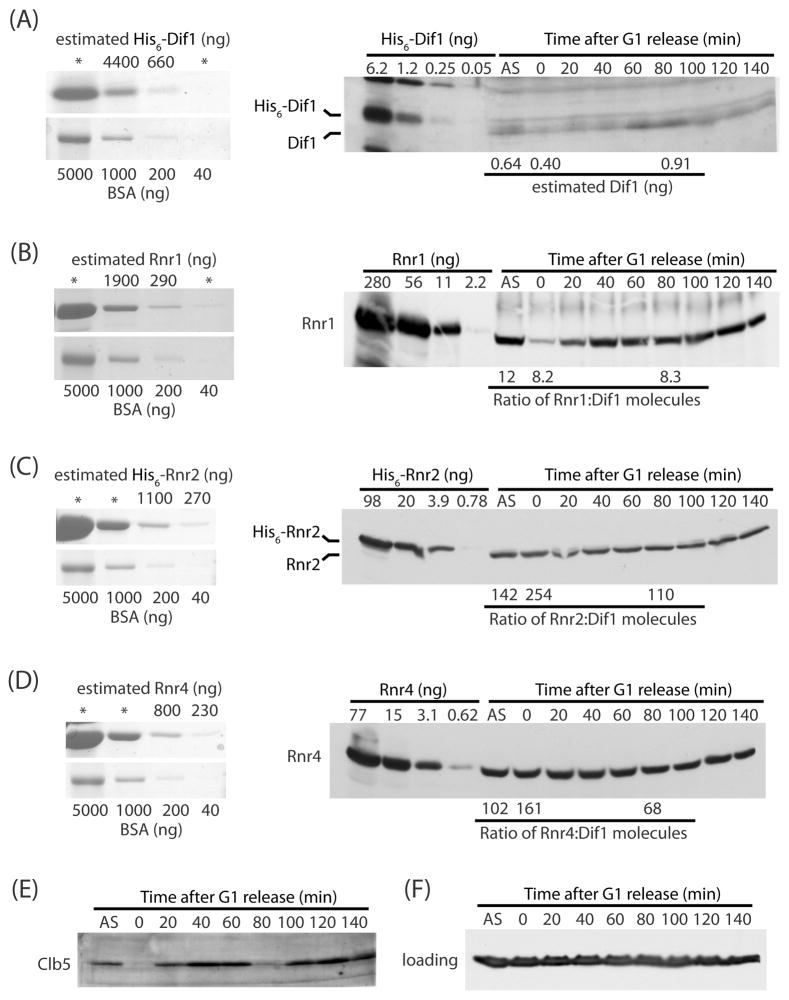

One model for the role of Dif1 in Rnr2-Rnr4 localization is as an adaptor that enhances the association of Rnr2-Rnr4 with Wtm1. If this model is correct, Dif1 and Rnr2-Rnr4 should be present in roughly equal amounts. Thus, we carefully determined the absolute abundance of Rnr1, Rnr2, Rnr4 and Dif1. Rnr1 and Rnr2-Rnr4 were purified as previously described (Ge et al., 2001; Nguyen et al., 1999) and Dif1 was purified from E. coli as a His6-tagged protein. We estimated the concentration of purified Rnr1, Rnr2, Rnr4 and Dif1 proteins with Coomassie staining using known BSA standards (Figure 5A–D, left panels). Serial dilutions of these protein samples alongside cell lysates from asynchronous cultures of wild-type cells in log-phase or cell lysates from samples after release from a G1 block (Figure 5A–D, right panels), using Clb5 as a marker of cell cycle progression (Figure 5E). We estimate that during log phase, the number of molecules per cell for Dif1, Rnr1, Rnr2 and Rnr4 are 1,300, 16,000, 190,000 and 130,000, respectively. The molecular ratio of Dif1-to-Rnr1 is approximately 1:12, and that of Dif1-to-Rnr2 is approximately 1:150. At 80 minutes after G1-release, when cells are in G2 and the abundance of Dif1 is maximal, the ratio of Dif1-to-Rnr1 is 1:8.3, while that of Dif1-to-Rnr2 is 1:110. Thus, the number of Rnr2 molecules greatly exceeds that of the Dif1 molecules. This indicates that Dif1 cannot act as a stoichiometric adaptor that facilitates binding to Wtm1 and instead suggests that Dif1 functions catalytically to maintain nuclear Rnr2-Rnr4.

Figure 5. Dif1 is much less abundant than the Rnr2-Rnr4 heterodimer.

(A) Left panel: known standards of bovine serum albumin (BSA) were resolved on SDS-PAGE alongside of five-fold serial dilutions of purified recombinant His6-Dif1 to estimate the concentration of the original Dif1 sample in nanogram. Dif1 serial dilutions that are beyond the range of the BSA standard were not used for estimation of protein concentration and were marked by asterisks (*). Right panel: known quantities of His6-Dif1 were resolved on SDS-PAGE alongside of lysates from asynchronous (AS) and synchronized wild-type cells released from a G1-block and taken at 20-minute intervals. The membrane was probed with anti-Dif1 antibodies. (B) As in part A except measuring Rnr1. Right panel: estimated Rnr1:Dif1 ratios are indicated below the western blot for the asynchronous, 0-minute, and 80-minutes time points. (C) As in part A except measuring Rnr2. (D) As in part A except measuring Rnr4. (E) Clb5 western blot to show progression of S-phase in the synchronized culture. (F) Tubulin western blot serves as loading control.

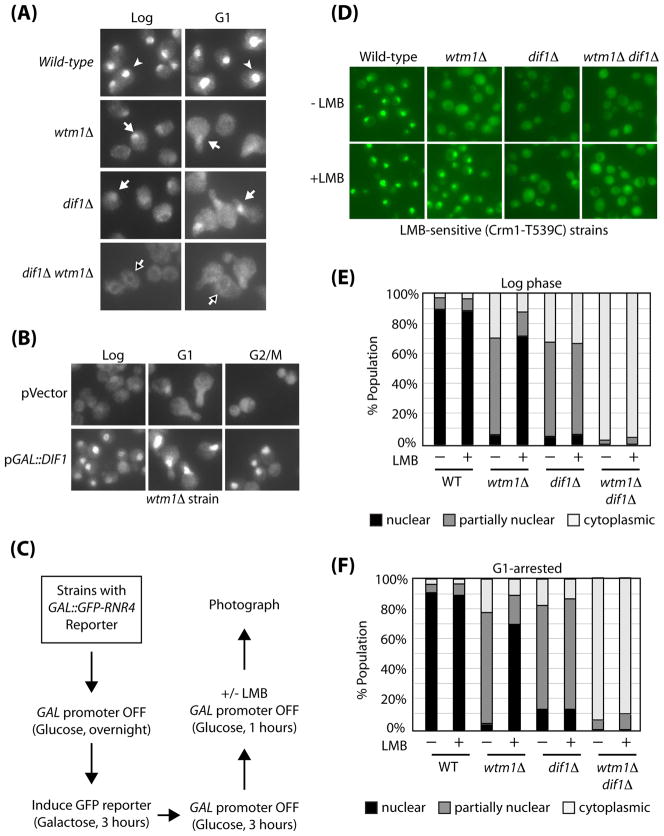

DIF1 and WTM1 regulate Rnr2-Rnr4 localization through mechanistically distinct pathways

The elimination of the Wtm1 adaptor role for Dif1 opened up the possibility that it might work in a separate pathway to Wtm1 even though their null phenotypes are very similar (Fig. 2C). Thus, we examined Rnr2 localization in the dif1Δ wtm1Δ mutants compared to the single mutants. While each mutant displayed residual nuclear accumulation, dif1Δ wtm1Δ double mutants lost this residual nuclear Rnr2 staining and often displayed significant Rnr2 nuclear exclusion (Figure 6A, black arrows). The above observation suggests Wtm1 and Dif1 can function through separate mechanisms and may be involved in different pathways.

Figure 6. Dif1 controls the nuclear import of Rnr2-Rnr4.

(A) The nuclear localization of Rnr2 in the dif1Δ wtm1Δ double mutant was compared to wild-type, wtm1Δ and dif1Δ single mutants. Log-phase and G1-arrested cells were processed for visualization of Rnr2 by indirect immunofluorescence. Cells with strong nuclear Rnr2 staining (white arrowhead), residual nuclear Rnr2 staining (white arrow), and Rnr2 nuclear exclusion staining (black arrow) are indicated. (B) wtm1Δ strains containing vector alone or a galactose-inducible DIF1 plasmid (pGAL::DIF1) were grown to log phase in glucose media. Cells were then switched to galactose media for 3 hours, while either being kept in log phase or arrested in G1 or G2/M. Samples were processed for Rnr2 visualization by indirect immunofluorescence. (C) A schematic of the experiment used to examine nuclear import of Rnr2-Rnr4. Cells were grown to log-phase in raffinose-glucose media, then switched to raffinose-galactose media for 3 hours to turn on the transcription of the GAL1-GFP-RNR4 reporter. The promoter was shut off by switching back to glucose media for 3 hours, before leptomycin B was added for an additional hour (LMB, 200 ng/mL). For the analysis of G1-arrested cells, the last 2 steps (4 hours) were carried out in the presence of α-factor. Cells were photographed for GFP-Rnr4 localization. (D) GFP-Rnr4 localization in wild-type, wtm1Δ, dif1Δ, and wtm1Δ dif1Δ mutants in the LMB-sensitive (Crm1-T539C) background were treated with or without LMB during log-phase. (E) Quantification of GFP-Rnr4 localization in part D. (F) Quantification of GFP-Rnr4 localization in G1-arrested cells, treated with or without LMB.

If Dif1 functions through a mechanism independent of Wtm1, hyper-activation of either the Dif1 or Wtm1 pathways might suppress the defective Rnr2-Rnr4 anchoring phenotype of the other mutants. Thus, we over-produced Dif11 in the wtm1Δ background, or Wtm1 in the dif1Δ background. Dif1 overproduction significantly rescued the Rnr2 localization defect in wtm1Δ mutants (Fig. 6B), while overproduction of Wtm1 in dif1Δ mutants had no effect (data not shown). Together, the enhanced defect of the double mutants and the suppression of wtm1 mutants by DIF1 overproduction suggests that Wtm1 and Dif1 operate in two independent branches of the Rnr2 localization pathway.

DIF1 is required for the nuclear import of Rnr2-Rnr4

The inability of dif1Δ mutants to localize Rnr2-Rnr4 could be due either to a defective import or to a problem in retaining Rnr2-Rnr4 inside the nucleus once imported (i.e. enhanced export or failed anchoring). If this is a nuclear retention defect, blocking nuclear export should accumulate Rnr2-Rnr4 inside the nucleus. Alternatively, if the defect occurs prior to nuclear import, blocking the nuclear export would have a minimal effect on nuclear accumulation. Therefore, we used leptomycin B (LMB) to inhibit the Crm1 exportin pathway (Kudo et al., 1998), which is essential for the release of nuclear Rnr after DNA damage in S. pombe (Liu et al., 2003). We confirmed that release of Rnr2 from the nucleus after HU treatment is inhibited by LMB, using a strain carrying the LMB-sensitive CRM1-T439C allele (Neville and Rosbash, 1999) (data not shown).

We first examined the effects of blocking nuclear export in the wtm1Δ mutant. A GAL1::GFP-RNR4 reporter plasmid was introduced into different strains and induced for 3 hours then repressed by addition of glucose to prevent further synthesis of the reporter during the analysis (Figure 6C). LMB was then added for one additional hour prior to visualization. LMB treatment led to the nuclear accumulation of GFP-Rnr4 in the wtm1Δ, LMB-sensitive background (Figure 6D, 6E), consistent with a role for Wtm1 in nuclear retention rather than import. In contrast, LMB treatment of the dif1Δ or dif1Δ wtm1Δ double mutants did not cause nuclear accumulation of the GFP-Rnr4 reporter (Figure 6D, 6E), indicating that the defect of the dif1Δ mutant occurs prior to nuclear import. To rule out potential cell-cycle artifacts, α-factor was used to arrest cells in G1 before LMB treatment, and provided similar results (Figure 6F). These results indicate that Dif1 is a regulator of nuclear import of Rnr2-Rnr4.

Dif1 directly binds to Rnr2-Rnr4 complexes

Dif1 may affect nuclear import of Rnr2-Rnr4 directly or indirectly. However, a strong prediction of the direct importer model is that Dif1 will directly bind Rnr2-Rnr4 complexes. Consistent with that possibility, during the course of our investigation we found that purified recombinant Dif1 had a mild but reproducible inhibitory effect on RNR enzymatic activity in vitro (data not shown). We therefore examined binding between purified Dif1 and RNR subunits using surface plasmon resonance. Rnr2-Rnr4 immobilized on the surface of the sensor chip could bind to Dif1 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 7A). We calculated the Kd of this binding to be 0.6 μM. Conversely, Dif1 immobilized on the surface of the sensor chip also bound to Rnr2-Rnr4 heterodimers (data not shown). No detectable binding to the Rnr1 homodimer was observed (data not shown). To examine what portion of Dif1 might mediate this interaction, we generated mutations in the conserved Hug domain (Dif1-hug) (Figure 7B). The binding of Dif1 to Rnr2-Rnr4 required an intact Hug domain (Figure 7A). Importantly, the Dif1-hug mutant was also defective for the proper nuclear localization of Rnr2-Rnr4 (Figure 7C), even though it maintained similar kinetics of phosphorylation and degradation as Dif1-WT (Figure 4F, 4G). We have consistently observed higher levels of endogenous Dif1-hug compare to WT Dif1 for unknown reasons. These data suggest that Dif1 facilitates the nuclear import of Rnr2-Rnr4 via direct binding through its Hug domain.

Discussion

The precise control of intracellular dNTP pools is critical to the maintenance of genomic integrity. Therefore, organisms have evolved multilayered controls to regulate the RNR pathway. In yeast, RNR is regulated by the cell cycle and DNA damage response pathways through gene expression, inhibitor destruction, and subcellular localization – the focus of this study. Our previous studies demonstrated that the nuclear protein Wtm1 secures Rnr2-Rnr4 inside the nucleus through an anchoring mechanism. However, how localization responded to DNA damage was not understood. Our current study identifies a DNA damage-regulated protein, Dif1, that controls the nuclear localization of Rnr2-Rnr4 by regulated nuclear import.

Dif1 and Wtm1 form distinct branches of the RNR nuclear localization pathway

Initially the similarities in the phenotypes of dif1Δ and wtm1Δ mutants suggested they might function in the same pathway, possibly by forming a complex with Wtm1 and Rnr2-Rnr4. However, careful analysis of the relative abundance of Dif1 and the Rnr proteins showed that Dif1 was much less abundant than Rnr2 and Rnr4, eliminating the co-tether model. Instead we find that DIF1 and WTM1 function in different branches of the Rnr localization pathway based on several pieces of data. First, dif1Δ wtm1Δ double mutants display enhanced cytoplasmic localization of Rnr2-Rnr4 relative to the single mutants. Second, over-expression of Dif1 suppresses the defect in Rnr2-Rnr4 nuclear localization in wtm1Δ mutants. Finally, blocking nuclear export using LMB in wtm1Δ mutants caused accumulation of nuclear Rnr2-Rnr4, and this accumulation was prevented in the wtm1Δ dif1Δ double mutants. This observation is consistent with the role of Wtm1 as a nuclear anchor to limit nuclear export, while Dif1 facilitates the nuclear import of Rnr2-Rnr4 and leads to the model shown in Figure 7D. In this model Wtm1 acts to limit the nucleoplasmic levels of Rnr2-Rnr4 complexes that are available for nuclear export. This reduces the rate of flux out of the nucleus and makes the system more responsive to the rate of nuclear import.

Regulation of this localization switch is accomplished largely through modulation of the rate of nuclear import through Dif1. Dif1 is controlled at three levels. First it is cell cycle-regulated with its abundance peaking at the end of S phase, when Rnr2-Rnr4 returns to the nucleus. There are likely to be additional aspects to this regulation induced by α-factor as Dif1 levels are lower in α-factor arrested cells, yet they are sufficient to localize Rnr2-Rnr4 into the nucleus. The rates of nuclear export could be regulated by α-factor. Consistent with this, wtm1Δ mutants show more nuclear localization in α-factor arrested cells. Secondly, Dif1 is regulated by proteolysis through direct phosphorylation by the Dun1 kinase on the Sml domain which constitutes a phosphodegron. The four serine and threonine residues near the end of the Sml domain are essential for the phosphorylation, inhibition and destruction of Dif1 in response to DNA damage. Mutation of the phosphorylation sites results in stabilization of Dif1 and defective release of nuclear Rnr2-Rnr4 in response to DNA damage. Finally, phosphorylation of the Sml domain is sufficient to abolish the function of Dif1 prior to its degradation. This, to our knowledge, is the first example of a phosphorylation event that both inactivates a protein and separately targets it for degradation.

While regulatory information flows through the Dif1 branch of the pathway, there are additional regulatory inputs into the system because the residual nuclear localization seen in dif1 mutants can be relieved by treatment with HU to generate a nuclear halo or empty nucleus phenotype seen in wtm1Δ dif1Δ double mutants. Whether this works through regulation of Wtm1-Rnr2-Rnr4 affinity, the rate of nuclear export via regulation on the exportin Crm1, or the residual DIF1-independent Rnr2-Rnr4 nuclear import pathway remains to be determined.

The key mechanistic insight on Dif1 function comes from the direct binding of Dif1 with Rnr2-Rnr4 through the Hug domain. Dif1-hug mutant retain the ability to be phosphorylated and degraded in response to DNA damage, but fail to properly localize Rnr2-Rnr4. Given the inability of the dif1Δ mutant to import Rnr2-Rnr4, the simplest model is that Dif1 binds the Rnr2-Rnr4 complex through its Hug domain and to activate import by serving as an adaptor or by activating a latent nuclear localization signal on the Rnr2-Rnr4 complex. In unpublished work, we have identified candidate importins/karyopherins with defective Rnr2-Rnr4 nuclear localization. The mechanism of how Dif1 influence the interaction between Rnr2-Rnr4 and its importin(s) remained an important area to be elucidated.

A unifying theory for functions of the Spd1, Dif1 and Sml1 family of Rnr regulators

The DIF1 and the HUG1/SML1 loci are syntenic, and arose from a genome duplication in an ancestor of S. cerevisiae (Dietrich et al., 2004; Kellis et al., 2004) that further diverged into three separate genes. The likely structure of the original protein is best illustrated by their ortholog Aer122c in Ashbya gossypii, a species closely related to S. cerevisiae but which did not undergo the genome duplication. Aer122c is also related to S. pombe Spd1, the first regulator of Rnr small subunit localization. Spd1 has been shown to maintain spRnr2 (Suc22) of S. pombe in the nucleus (Liu et al., 2003). However, recent experiments have suggested that it acts as an inhibitor of RNR activity by binding to S. pombe spRnr1 (Cdc22), the large RNR subunit, casting doubt on the suggested spRnr2 nuclear retention mechanism. Our work proposes an explanation for these seeming discrepancies. We propose that Spd1, Dif1, Sml1 and Hug1 all evolved from a common ancestral gene related to Aer122c that had three basic domains. The first domain, which we call the Hug domain, is required for the physical binding and nuclear import of Rnr2 family members. The second domain, the Sml domain, is a degron/phosphodegron that confers DNA damage and cell cycle regulation on the activities of the proteins. The third domain is the R1B domain that binds the Rnr1 subunit to act as an RNR enzymatic inhibitor. Thus, this ancestral gene employed two different mechanisms through which to negatively regulate RNR function and a regulatory region that allowed those functions to be modulated. We propose that Spd1 is closely related to this ancestral gene and retains all three functions although its degradation is likely regulated at the level of ubiqutin ligase activation rather than through phosphorylation of the degron (Liu et al., 2005). This explains what had on the surface appeared to be an inconsistency with the ability of Spd1 to bind the spRnr1 but at the same time localize the spRnr2. In budding yeast, these functions have been split between Dif1 and Sml1. Both proteins retain a phosphodegron that confers cell cycle and DNA damage regulation through an as yet unknown ubiquitin ligase. However, Dif1 lacks the C-terminal Rnr1 interacting domain while Sml1 lacks the Rnr2-binding Hug domain. The biochemical role of the damage-inducible Hug1 remains to be elucidated although our model would predict that it should be able to bind Rnr2-Rnr4, and possibly competing or negatively regulate Dif1 activity.

Our discovery of Dif1 has illuminated part of the mechanism cells use to regulate localization of RNR small subunits. To our knowledge, the combination of a nuclear anchor limiting nuclear export and a regulated importer to coordinate subcellular localization appears to be unique. This is yet another example of a dynamic switch in which two antagonistic processes, here export and import, are coordinately regulated to produce an outcome, much like Cdk1 phosphorylation and dephosphorylation (Harper and Elledge, 2007) and Cdc20 ubiquitination and deubiquitination (Stegmeier et al., 2007). This is likely to be a strategy that will found to regulate the localization of many other proteins in the future.

Materials and Methods

Media and growth conditions

α-factor and nocodazole arrest were carried out as previously described (Desany et al., 1998). DNA damage agents were used at the following concentrations: phleomycin, 25–100 ng/mL; MMS, 0.1%; HU, 150 mM; and ionizing radiation, 20 kRad. Leptomycin B (LC laboratories) was used at 100–200 ng/mL.

Polyclonal antibody for Dif1

Recombinant full-length GST-Dif1 was purified from E coli and used to generate a rabbit antibodies (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX). For western blot analysis, a 1:1,000 dilution was used.

Protein sample preparation and phosphatase treatment

TCA precipitation was done as previously described (Longhese et al., 1997). Phosphatase treatment of protein sample was carried out as described (Vialard et al., 1998), except that calf intestinal phosphatase (New England Biolab) was used as the phosphatase, and 10 mM Na3VO4 and 50 mM EDTA was used as the phosphatase inhibitors.

Indirect immunofluorescence and visualization of GFP

Indirect immunofluorescence was done as previously described (Lee and Elledge, 2006). Both anti-Rnr2 and anti-Rnr4 antibodies were used at 1:10,000 (Yao et al., 2003).

Phospho-mapping of Dif1 and Rnr2

Strains carrying 3HA-Rnr2 and 3Myc-Dif1 were HU-treated. 3HA-Rnr2 and 3Myc-Dif1 were immuno-precipitated and resolved by SDS-PAGE. The gel with the 3HA-Rnr2 sample was Coomassie stained while that with 3Myc-Dif1 was silver stained by SilverQuest (Invitrogen). The bands were excised for phospho-mapping analysis.

In vitro Dun1 kinase assay

Wild-type, phospho-serine/threonine mutated, or Hug domain mutated Dif1 strains were used for immuno-precipitation by anti-Dif1 polyclonal antibodies. The Dif1 proteins were left on 15 μl of protein A beads and washed twice with kinase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM NaVO4). GST-Dun1 purified from Baculovirus infected SF9 insect cell was incubated with the protein A beads containing Dif1 in 100 μl of kinase buffer, with 2 μM of cold ATP, and 5 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP at 30 °C for 45 minutes.

Protein expression and purification

Rnr1 and Rnr2-Rnr4 were purified from yeast as described (Ge et al., 2001; Nguyen et al., 1999). His6-tagged DIF1 plasmid (based on the pET15b vector) in BL21(DE3) pLysS cells were grown to OD600 of 0.6, and induced with IPTG (0.2 mM) at 18°C overnight. Cells were washed, resuspended in binding buffer (Tris pH 7.5 30mM, NaCl 150mM, DTT 1mM, Triton 0.1%, PMSF 1mM, Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail), sonicated to disrupt the cells. The crude lysate was spun at 10,000g for 15 minutes. Dif1 protein in the supernatant was purified using Ni-NTA beads according to the Qiaexpressionist manual (Qiagen), with 5 mM of imidazole added to the binding and washing steps to increase the stringency of purification. His6-Dif1 was eluted by 200mM of imidazole, and dialyzed into the appropriate buffers.

Quantification of protein abundance

Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE or exposed films from western blots were scanned digitally and the intensity of protein bands was quantified using the gel analysis function of ImageJ software (NIH). For the western blot quantification of Dif1, Rnr1, Rnr2, and Rnr4, each lane was loaded with 170, 17, 3.4, and 3.4 ng of protein from cell lysate, respectively. Total number of cells used for protein extraction was determined by colony plating and optical density (OD600), and is used for the calculation of molecules per cell.

BIAcore analysis

Purified Rnr2-Rnr4 was immobilized on a CM5 chip by amine coupling at a level of 9,945 response unit (RU). All analytes were dialyzed in PBS buffer, which also serves as the running buffer. The binding assay was carried out at 25 °C with a flow rate of 30 μl/min on a Biacore 3000. Data was analyzed using BIAevalution 3.2 software, reference was subtracted and corrected for the bulk effect. Binding affinity was calculated by steady state fit using a 1:1 binding model.

Strains and plasmids

For a complete list of yeast strains and plasmids used for this work, see Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Rosbash for strains, P. Silver and A. Amon for helpful suggestions, and J. Li for assistance in the preparation of GST-Dun1 kinase. We thank T. Tomaino for assistance with data analysis. We are grateful to Minxia Huang for communicating results prior to publication. This work was supported by NIH grants to S.J.E. and J.S. S.J.E. is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Basrai MA, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Hieter P. NORF5/HUG1 is a component of the MEC1-mediated checkpoint response to DNA damage and replication arrest in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7041–7049. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgne A, Nurse P. The Spd1p S phase inhibitor can activate the DNA replication checkpoint pathway in fission yeast. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 23):4341–4350. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.23.4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabes A, Domkin V, Thelander L. Yeast Sml1, a protein inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36679–36683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabes A, Georgieva B, Domkin V, Zhao X, Rothstein R, Thelander L. Survival of DNA damage in yeast directly depends on increased dNTP levels allowed by relaxed feedback inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase. Cell. 2003;112:391–401. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desany BA, Alcasabas AA, Bachant JB, Elledge SJ. Recovery from DNA replicational stress is the essential function of the S-phase checkpoint pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2956–2970. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich FS, Voegeli S, Brachat S, Lerch A, Gates K, Steiner S, Mohr C, Pohlmann R, Luedi P, Choi S, et al. The Ashbya gossypii genome as a tool for mapping the ancient Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Science. 2004;304:304–307. doi: 10.1126/science.1095781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elledge SJ, Davis RW. Identification and isolation of the gene encoding the small subunit of ribonucleotide reductase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: DNA damage-inducible gene required for mitotic viability. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2783–2793. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elledge SJ, Davis RW. Two genes differentially regulated in the cell cycle and by DNA-damaging agents encode alternative regulatory subunits of ribonucleotide reductase. Genes Dev. 1990;4:740–751. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge J, Perlstein DL, Nguyen HH, Bar G, Griffin RG, Stubbe J. Why multiple small subunits (Y2 and Y4) for yeast ribonucleotide reductase? Toward understanding the role of Y4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10067–10072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181336498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson P, Dahl L, Chilkova O, Domkin V, Thelander L. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe replication inhibitor Spd1 regulates ribonucleotide reductase activity and dNTPs by binding to the large Cdc22 subunit. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1778–1783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol Cell. 2007;28:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg C, Fleck O, Hansen HA, Liu C, Slaaby R, Carr AM, Nielsen O. Ddb1 controls genome stability and meiosis in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 2005;19:853–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.329905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Elledge SJ. Identification of RNR4, encoding a second essential small subunit of ribonucleotide reductase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6105–6113. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Zhou Z, Elledge SJ. The DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways induce transcription by inhibition of the Crt1 repressor. Cell. 1998;94:595–605. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C, Michaelis S, Mitchell A. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kellis M, Birren BW, Lander ES. Proof and evolutionary analysis of ancient genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2004;428:617–624. doi: 10.1038/nature02424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo N, Wolff B, Sekimoto T, Schreiner EP, Yoneda Y, Yanagida M, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M. Leptomycin B inhibition of signal-mediated nuclear export by direct binding to CRM1. Exp Cell Res. 1998;242:540–547. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YD, Elledge SJ. Control of ribonucleotide reductase localization through an anchoring mechanism involving Wtm1. Genes Dev. 2006;20:334–344. doi: 10.1101/gad.1380506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincker F, Philipps G, Chaboute ME. UV-C response of the ribonucleotide reductase large subunit involves both E2F-mediated gene transcriptional regulation and protein subcellular relocalization in tobacco cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1430–1438. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Poitelea M, Watson A, Yoshida SH, Shimoda C, Holmberg C, Nielsen O, Carr AM. Transactivation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdt2+ stimulates a Pcu4-Ddb1-CSN ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 2005;24:3940–3951. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Powell KA, Mundt K, Wu L, Carr AM, Caspari T. Cop9/signalosome subunits and Pcu4 regulate ribonucleotide reductase by both checkpoint-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1130–1140. doi: 10.1101/gad.1090803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhese MP, Paciotti V, Fraschini R, Zaccarini R, Plevani P, Lucchini G. The novel DNA damage checkpoint protein ddc1p is phosphorylated periodically during the cell cycle and in response to DNA damage in budding yeast. Embo J. 1997;16:5216–5226. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville M, Rosbash M. The NES-Crm1p export pathway is not a major mRNA export route in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Embo J. 1999;18:3746–3756. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, Ge J, Perlstein DL, Stubbe J. Purification of ribonucleotide reductase subunits Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4 from yeast: Y4 plays a key role in diiron cluster assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12339–12344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund P, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:681–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases: the evolution of allosteric regulation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;397:149–155. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmeier F, Rape M, Draviam VM, Nalepa G, Sowa ME, Ang XL, McDonald ER, 3rd, Li MZ, Hannon GJ, Sorger PK, et al. Anaphase initiation is regulated by antagonistic ubiquitination and deubiquitination activities. Nature. 2007;446:876–881. doi: 10.1038/nature05694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbe J. Di-iron-tyrosyl radical ribonucleotide reductases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiki T, Dice LT, Hettich RL, Dealwis C. Identification of phosphorylation sites on the yeast ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11293–11303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallen EA, Cross FR. Interaction between the MEC1-dependent DNA synthesis checkpoint and G1 cyclin function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1999;151:459–471. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialard JE, Gilbert CS, Green CM, Lowndes NF. The budding yeast Rad9 checkpoint protein is subjected to Mec1/Tel1-dependent hyperphosphorylation and interacts with Rad53 after DNA damage. Embo J. 1998;17:5679–5688. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voegtli WC, Ge J, Perlstein DL, Stubbe J, Rosenzweig AC. Structure of the yeast ribonucleotide reductase Y2Y4 heterodimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10073–10078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181336398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PJ, Chabes A, Casagrande R, Tian XC, Thelander L, Huffaker TC. Rnr4p, a novel ribonucleotide reductase small-subunit protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6114–6121. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, Zhou B, Liu X, Qiu W, Jin Z, Yen Y. Wild-type p53 regulates human ribonucleotide reductase by protein-protein interaction with p53R2 as well as hRRM2 subunits. Cancer Res. 2003;63:980–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao R, Zhang Z, An X, Bucci B, Perlstein DL, Stubbe J, Huang M. Subcellular localization of yeast ribonucleotide reductase regulated by the DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6628–6633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131932100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, An X, Yang K, Perlstein DL, Hicks L, Kelleher N, Stubbe J, Huang M. Nuclear localization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ribonucleotide reductase small subunit requires a karyopherin and a WD40 repeat protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1422–1427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510516103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Yang K, Chen CC, Feser J, Huang M. Role of the C terminus of the ribonucleotide reductase large subunit in enzyme regeneration and its inhibition by Sml1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2217–2222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611095104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Georgieva B, Chabes A, Domkin V, Ippel JH, Schleucher J, Wijmenga S, Thelander L, Rothstein R. Mutational and structural analyses of the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1 define its Rnr1 interaction domain whose inactivation allows suppression of mec1 and rad53 lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9076–9083. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9076-9083.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Muller EG, Rothstein R. A suppressor of two essential checkpoint genes identifies a novel protein that negatively affects dNTP pools. Mol Cell. 1998;2:329–340. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Rothstein R. The Dun1 checkpoint kinase phosphorylates and regulates the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3746–3751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062502299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Elledge SJ. Isolation of crt mutants constitutive for transcription of the DNA damage inducible gene RNR3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1992;131:851–866. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.4.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.