Abstract

Ethnopharmacological relevance

Traditional knowledge of medicinal plant use in many regions of Papua New Guinea and the Autonomous Region of Bougainville is poorly described and rapidly disappearing. A program initiated by the University of Papua New Guinea to systematically document and preserve traditional knowledge of medicinal plant use was initiated with WHO help in 2001.

Aim of the study

To document and compare medicinal plant use in the Siwai and Buin Districts of the Island of Bougainville. Siwai and Buin districts represent two adjacent geographic regions of differing language traditions.

Materials and methods

This report is a combination of two University of Papua New Guinea reports generated using a University of Papua New Guinea and Papua New Guinea Department of Health approved survey questionnaire “Information sheet on traditional herbal reparations and medicinal plants of Papua New Guinea”.

Results

Although Siwai and Buin Districts are adjacent in Southern Bougainville, there is considerable variation in the specific plants used medicinally and the specific uses of those plants that are used commonly in the two regions. In addition, many of the plants used in the region are widely distributed species that are used medicinally in other settings. Nevertheless, the high endemicity of plants and the extraordinary cultural diversity in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville has yielded description of the medicinal use of many plants that have not previously been reported in the wider scientific literature.

Conclusions

Efforts to document and preserve traditional knowledge of plant use in Papua New Guinea have yielded important new records of plants with potential application in the provision of health care for a developing nation with an under developed Western style rural health care system. This report documents substantial commonality in the general modes of medicinal plant preparation and in the health care applications of plant use in the Siwai and Buin traditions, however, there was considerable difference noted in the particular uses of the specific plants used in one or another of the districts.

Keywords: Papua New Guinea, Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Siwai, Buin Medicinal plant survey

1. Introduction

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is extraordinarily rich in plant and cultural diversity. PNG is a geographically segregated mountainous nation of at least 800 ethnic traditions and languages (Asher, 1994; Grimes, 2000). This geology has also resulted in isolated ecosystems and extraordinary biological diversity. PNG is home to an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 vascular plants with approximately 60% endemicity (Beehler, 1993; Mittermeier et al., 1997). Initially settled around 40,000 years ago, extended habitation in diverse environs has rendered most ethnic groups in PNG rich in medicinal plant knowledge (National Department of Health, 2007). The traditional use of medicinal plants constitutes an important and threatened information reservoir that has been empirically tested and adopted through millennia of trial and error, but that is threatened by on-going development and change of lifestyle. Prior to the current University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG) Traditional Medicines Database Surveys, two of which are reported here, PNG medicinal plant use and corresponding pharmacological assessment was not systematically studied. The documentation of medicinal plants in PNG has been haphazard and the accrued knowledge not widely disseminated internationally. We estimate that historically some 800 PNG plants have been described in the literature for treatment of various ailments, but this represents only a fraction of the total number of plants actually utilized.

The fact that a sizable majority of the PNG population relies on medicinal plants and traditional practitioners for health care has been formally recognized by the national government (National Department of Health, 2007). The PNG National Health Plan, 2001–2010, promoted collaboration between the World Health Organization (WHO) and UPNG to assist in the development of traditional medicines in the country. A traditional medicines survey questionnaire was developed using WHO guidelines. In 2001 the surveys initiated with approvals and endorsements from the UPNG School of Medicine and Health Sciences Research and Ethics Committee and the Medical Research and Advisory Committee of the PNG Department of Health. Also established at this time was a proprietary database for traditional medicines, maintained at UPNG (Rai, 2004), that now serves as a national resource as the government seeks to move validated and safe herbal remedies into the national health care formulary (National Department of Health, PNG, 2007).

Before the Bougainville crisis in 1989, Siwai and Buin Local Level Governments (LLG) of Southern Bougainville Island provided healthcare services commensurate with many other parts of Papua New Guinea. However, during the conflict, even those modest services were interrupted and the people of the region relied heavily upon medicinal plants to ameliorate illness. Now that Bougainville has gained autonomy, services are returning to the Districts of Siwai and Buin, even though the remaining separatist Mekamuui (Bougainville Resistance Army) forces intermittently interrupt travel within Southern Bougainville. With the return of services has come a perceptible loss of traditional knowledge concerning plant use as some of the elder herbalists pass away without transferring their knowledge or social role to heirs.

Bougainvillian languages include Austronesian, Papuan and Polynesian languages, and none of them are spoken by more than 20% of the total population (Bougainville, 2011). Siwai and Buin are adjacent costal districts of Southern Bougainville Island characterized by a coastal lowland that extends inland to elevations of approximately 1,000 m. Most recent available data (National Research Institute, 2010) indicates the Siwai District is populated by approximately 14,000 Siwai language (also called Motuna; Summer Institute of Linguistics, 2010) speaking people. Buin District is populated by approximately 26,000 people, those interviewed for this work spoke North or South Mokeruui dialects of the Telei language (also called Terei, Buin, Rugara; Summer Institute of Linguistics, 2010). According to Regan (1998) only a rough estimate can be given for the total number of mutually unintelligible tongues spoken in the Solomon Islands and Bougainville, all the dialects described there would total “several times” more than 100 (Terrell, 1977). The Siwai and Telei languages are among those that are divided into dialects that are not necessarily mutually understandable (Bougainville, 2011).

Siwai and Telei are both considered Papuan in origin. The linguistic relationships of the Papuan languages are not easily established (Max Planck Research Group on Comparative Population Linguistics, 2009). The Papuan languages are thought to have descended from the first human habitation of the Bismarck Archipelago, about 35,000 BP. Recent assessment of structural phylogeny indicates common ancestry or ancient contact for the Papuan languages, while traditional linguistics indicates several different Papuan language families in the region. In any case, Siwai and Telei are considered to be in a related germinal family (Max Planck Research Group on Comparative Population Linguistics, 2009). Recently, Tok Pisin has become the principal language of trade for many in Siwai and Buin (Bougainville, 2011). The adoption of this common tongue will serve to increase relations amongst the two neighbors.

This work provides an opportunity to compare medicinal plant use in two poorly studied traditionally distinct populations that occupy closely located geographic regions.

2. Material and Methods

The UPNG initiated program to preserve traditional knowledge on plant use in PNG has become an effective training exercise for selected bachelor of pharmacy, and other, senior students. In addition to training in subjects relevant to herbal medicine use, students are trained to record new data concerning the specific uses of plants and specific cultural traditions within Papua New Guinea. The traditional medicines database now contains cultural plant use data from over 30 LLGs in PNG.

The medicinal plant survey questionnaire is titled “Information sheet on traditional herbal preparations and medicinal plants of Papua New Guinea”. To conduct the survey, students are trained in questionnaire administration, traditional medicines use, taxonomic nomenclature, herbarium specimen preparation, and instructed in the preservation and documentation of traditional knowledge and culture. The students are supported for a one year elective that includes travel to their home districts to conduct the surveys.

The survey in the Siwai LLG area was conducted in 2002, the survey in the Buin LLG area was conducted in 2006. Data were collected by two specially trained fourth year pharmacy students, working in their home communities and are presented in Table 1. Face to face interviews were conducted with locally acknowledged experts in medicinal plant use. These experts included herbalists (a patrilineal position in some villages in Southern Bougainville, which is noteworthy, because many aspects of society in Bougainville is matriarchal), general practitioners (both genders), birth attendants (females), bone setters and regular users of medicinal plants. In the Siwai region, 21 experts were interviewed in the Panakei, Konga, Motirui, Mamagota and Morohai villages; it was noted that in this region the majority of those interviewed self-diagnosed and self-treated. In the Buin area, 17 experts were interviewed in the Turutai and Mongai villages, where there appeared to be a more formal hierarchy of recognized experts than was noted for the Siwai villages visited.

Table 1.

Summary of medicinal plant use data for Siwai (BS voucher numbers) and Buin (JW voucher numbers) areas of the Bougainville Autonomous Region

| Voucher | Family | Genus & Species | Condition or Disease | Part | Preparation | Application | village | local name | Habitat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS01 | Polypodiaceae | Christella arida (D. Don) Holttum | Coagulant, wounds | yL | Mashed | Topical | P | Hahara | Grassland with few trees |

| BS02 | Acanthaceae | Graptophyllum pictum (L.) Griff. | Pre-leprosy (rash called hisahisa) | L | Heated | Topical | P | Singarata | Cultivated |

| BS03 | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia sp. | Blood clots after child birth | yL | Decoction | Oral | P | Irihih | Higher elevations, cultivated |

| BS04 | Zingiberaceae | Costus speciosus Sm. | Sores; toothache | yL; Root | Heated and mashed; fresh | Topical | P | Mangmang | Abandoned gardens and grassland |

| BS05 | Moraceae | Ficus nodosa Teijsm. & Binn. | Scabies | Bark | Infusion in coconut oil | ND | P | Nuung | Grassland and rainforest |

| BS06 | Verbenaceae | Premna serratifolia L. | Dysentery | Bark | Infusion | Oral | P | Karuwana | Secondary forest |

| BS07 | Dryopteridaceae | Nephrolepis hirsutula (Forst.) C. Presl | Angina pectoris | yL | Leaves heated and used to massage chest | Topical | ND | Kara-inho | Alongside rivers |

| BS08 | Rubiaceae | Uncaria sp. | Severe to moderate cough | Vine (Sap) | Fresh | Oral | P | Rungkihi | Lowland and highland rainforest |

| BS09 | Fabaceae | Cassia alata (L.)Roxb. | Skin fungus, herpes, eczema, ringworm, insect bites | L | Mashed, mixed with lime | Topical | P | A’aku-peero | Cultivated |

| BS10 | Cyperaceae | Cyperus cf. rotundus | Toothache | Root | Infusion | Oral rinse | P | Pihrototoka honna | Reforested areas |

| BS11 | Barringtoniaceae | Barringtonia novae-hiberniae Lauterb. | Angina pectoris | Bark | Infusion | Oral | P | Moriwo | Cultivated |

| BS12 | Rosaceae | Prunus gazelle-peninsulae (Kaneh. & Hatus.) Kalkman | Headache | Bark | Infusion; fresh | Oral, topical on forehead | P | Lauru | Reforested areas and gardens |

| BS13 | Malvaceae | Hibiscus rosa-chinensis L. | Eye infection | F | Flowers heated in coconut shells | Fumes into affected eye | P | Kukupih | Cultivated |

| BS14 | Piperaceae | Piper anisopleurum C.DC. | Productive cough | yL | Infusion | Oral | P | Punpupuri’i | Secondary and primary forest |

| BS15 | Urticaceae | Elatostema sp. | Productive cough | yL | Infusion | Oral | P | Simma’a | On stones in creeks |

| BS16 | Asteraceae | Wedelia biflora (L.) DC. | Productive cough | yL | Infusion | Oral | P | Hunpo | Sandy riverbanks |

| BS17 | Caesalpiniaceae | Pterocarpus indicus Willd. | Dysentery; haematouria; centipede bite; growth in the eye | Bark; Root; yL; Latex | Infusion; infusion; infusion; fresh | Oral; oral; oral; topical | P | Hondo | Secondary forest |

| BS18 | Apocynaceae | Alstonia scholaris (L.) R. Br. | Dysentery, diarrhea | Bark | infusion | Oral | P | Kingiri | Primary and secondary forest |

| BS19 | Lamiaceae | Plectranthus scutellarioides (L.) R. Br. | Headache and cough | yL | Infusion | Oral | P | Kapaatohi’i | Grass and shrubs |

| BS20 | Urticaceae | Leucosyke capitellata Wedd. | Productive cough | L | Infusion | Oral | P | Isoiso | Secondary forest |

| BS21 | Moraceae | Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg | Dysentery | Latex | Mixed with water | Oral | P | Kurako | Bushes, cultivated |

| BS22 | Convolvulaceae | Merremia peltata (L.) Merr. | Eye inflammation; bullet wounds | y Shoot; Vine | Juice from new shoots applied; heated and blown into bullet wounds | Topical; topical | P | Hogouna | Widely distributed |

| BS23 | Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica L. | Severe itchiness of legs | Bark | Scraped and mixed with lime | Topical | P | Kongsi’i | Bushes |

| BS24 | Moraceae | Ficus semicordata Buch.-Ham. ex Sm. | Headache and fever | yL | ND | Bath | P | Hituru | Reforested areas and rainforests |

| BS25 | Malvaceae | Hibiscus tiliaceus L. | Productive cough | L | Mashed to release succus | Oral | P | Paruparu | Coastal thickets and stream banks, secondary forests |

| BS26 | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia sp. | Diarrhea | Root | Fresh | Chewed | P | Pooraka | Fertile soil on high ground |

| BS27 | Solanaceae | Solanum torvum Swartz, Prodr. 47. 1788. | Dry cough | yL | Mashed to release succus | Oral | P | Koroh | Abandoned garden sites |

| BS28 | Zingiberaceae | Hornstedtia scottiana K. Schum. | Labor pains | Fruit | Fruit juice | Oral, topical on abdomen | P | I’isaru | Abandoned garden site and secondary forest |

| BS29 | Lauraceae | Cryptocarya sp. | Ear infection | Bark | Macerated and resultant aroma blown into ear | Topical | P | Mukeni | Rainforests and mountainous places |

| BS30 | Rubiaceae | Morinda citrifolia L. | Headache, body ache, painful ankles | Seed | Decoction | Oral | P | Ningto | Primary forest |

| BS31 | Fabaceae | Archidendron glabrum (K. Schum.)Lauter b. & K. Schum. | Severe headache | yL | Pounded and resulting succus strained | Oral | P | Piimoki | Rainforest |

| BS32 | Myrtaceae | Psidium guajava L. | Measles | yL | Decoction | Bath | P | ND | Cultivated |

| BS34 | Gesneriaceae | Aeschynanthus leptocladus C.B. Clarke | Labour pains | yL | Mashed | ND | P | Runowai | Small shrub that grows on trees |

| BS35 | Sterculiaceae | Melochia odorata L.f. | Dysuria | Root | Chewed with betel nut and lime | Chewed | P | Tamma | Secondary forest |

| BS37 | Urticaceae | Nothocnide melastomatifolia (K. Schum.) Chew | Dysuria | yL | Infusion | Oral | P | Kamaarininano | On trees in the jungle |

| BS38 | Euphorbiaceae | Homalanthus Novoguineensis (Warb.) K. Schum. | Body ache | ND | Succus | Oral | P | Tung | Abandoned gardens |

| BS39 | Melastomataceae | Melastoma malabathricum L. | Baby when sick for the first time | yL | ND | Bath | P | Tupaainaraku | Abandoned garden sites with few trees |

| BS40 | Fabaceae | Derris grandifolia | Constipation | ND | ND | ND | P | Kahani-ima | Rainforests |

| BS41 | Asteraceae | Mikania micrantha Kunth | Wounds | yL | Squeezed in hands | Topical | P | Matapa | Secondary forest |

| BS43 | Ranunculaceae | Clematis sp. | Headache | L | Mashed | Inhaled | ND | Humokung | Reforested areas and gardens |

| BS44 | Thelypteridaceae | Sphaerostephanos alatellus (Christ) Holttum | Fever | ND | ND | ND | P | Uwahaku | Fern in moist areas |

| BS45 | Urticaceae | Pipturus argenteus (G. Forst.) Wedd. | Leprosy | Seed | ND | ND | Mor | Ti’itipini-moi | Secondary forest |

| BS46 | Rosaceae | Rubus molucanus | Pre-leprosy (rash called hisahisa) | Thorns | Thorns are used to poke red spots | Topical | P | Si’imu | Shrubs in reforested areas |

| BS47 | Acanthaceae | Hemigraphis sp. | Scabies | L | ND | ND | P | Neeso | Rainforests |

| BS49 | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia unilateralis B.L. Burtt & R.M.Sm. | Constipation | Stem (core) | Fresh | Chewed | M | Moge’e | Secondary forest |

| BS50 | Fabaceae | Mucuna gigantean (Willd.)DC. | Cough and asthma | Stem | ND | ND | P | Aiya, Aiwa | Rainforest |

| BS51 | Solanaceae | Cyphomandra betacea Sendt. | Burns | L | ND | ND | P | Hitukong or Iha-si’i | Gardens |

| BS52 | Arecaceae/Palmae | Areca novo-hibernica Becc. | Boils | Bark | Chewed with lime | Massage on boil | P | Mu’usehu | Primary and secondary forest |

| BS54 | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia oceanica Burkill | Constipation | Stem (core) | Macerated | Oral | P | Hara | Rainforest |

| BS55 | Smilaceae | Geitonoplesium cymosum (R. Br.) A. Cunn. ex R.Br. | Scabies | L | Poultice | Topical | P | Pirigini | Rainforest |

| BS56 | Moraceae | Antiaris toxicara Lesch. | Small growths | Seed | Heated | Oral | P | Kokui | Low and Highland forest |

| BS57 | Moraceae | Ficus adenosperma Miq. | Fever | L | ND | ND | Mot | Turuwii | Highland rainforest |

| BS58 | Sterculiaceae | Melochia odorata L.f. | Enlarged spleen | ND | ND | ND | K | Kiiro/Takara | Lowland rainforest |

| BS59 | Poaceae | Setaria palmifolia (J. Koenig) Stapf, J. Linn. Soc., Bot. 42: 186. 1914. | Toothache | Root | ND | ND | P | Siruh | Grassland |

| BS60 | NA | Cytandra sp. | Dysentery | ND | ND | ND | P | Toputopu | Muddy places |

| BS61 | Euphorbiaceae | Homalanthus novoguineensis (Warb.) K. Schum. | Heartburn | Bark | Infusion | Oral | P | Hikumutu | Garden sites and secondary forest |

| BS62 | Araceae | Epipremnum pinnatum (L.) Engl. | Bone fractures, dislocated joints, and sprains | Stem | Heated over fire, mashed | ND | P | Pongkiriri | Primary and secondary forest |

| BS63 | Asteraceae | Ageratum conyzoides L. | Diarrhea and headache | L | Infusion | Oral | P | Mekosana or Rumahing | Garden weed |

| BS64 | Euphorbiaceae | Codiaeum variegatum (L.) Blume | Dislocated joints | Root | Macerated | Massage | P | Nunotong | Cultivated |

| BS65 | Apocynaceae | Alstonia sp. | Pain | L (Sap) | Fresh | Oral | P | Ponu | Secondary forest |

| BS66 | Apocynaceae | Alstonia spectabilis R. Br. | Chest pain | Bark | ND | ND | P | Miru | Abandoned garden sites |

| BS67 | Thelypteridaceae | Sphaerostephanos sp. | Labour | ND | ND | ND | Mot | Korokoro | Mountainside on riverside |

| BS68 | Araceae | Colocasia esculenta (Linnaeus) Schott | Swollen breasts | L | Heated | Massage | P | Ki’ikata | Regrowth after grass is cut in cocoa plantations |

| BS69 | Marattiaceae | Marattia melanesica Kuhn | Fever | ND | ND | ND | P | Tuiresi | Lowland and highland rainforest |

| BS70 | Arecaceae | Metroxylom sagu Rottb. | Prevention of enlarged spleen in newborns | ND | ND | ND | P | Piia | Muddy places and cultivated |

| BS71 | Moraceae | Ficus copiosa Steud. | Boils | Bark | Chewed with lime | Topical | P | Surosai | Reforested areas and bushes |

| BS72 | Palmae | Unidentified | Boils | Bark | Chewed with lime | ND | P | Kingkirisu | Unfertile soil |

| BS73 | Moraceae | Ficus hispidioides L.f. | Bone fractures, dislocated joints, and sprains | Seed | ND | ND | P | Su’usu’u | Secondary forest |

| BS74 | Euphorbiaceae | Macaranga aleuritoides F. Muell. | Cuts | yL | Mashed to release succus | Topical | P | Maasiko | Secondary forest |

| BS75 | Moraceae | Ficus sp. | Tongue cancer | Vine (Sap) | Fresh | Oral rinse | P | Kung | Grows on trees |

| BS76 | Lauraceae | Litsea calophyllantha K. Schum. | Painful urination | ND | ND | ND | P | Kungko’ | Lowland and highland rainforest |

| BS77 | Lauraceae | Cryptocarya sp. | Painful urination | Bark | Bark scraped with water and strained | Oral | P | Rugeria or Tiwito | Lowland and highland rainforest |

| BS78 | Smilacaceae | Smilax latifolia R. Br. | Fractures | Vine | Heated over fire and tied around fractures | Topical | P | Kowa’a | Rainforests |

| BS79 | Marattiaceae | Marattia fraxinea Raddi | Centipede bite | ND | ND | ND | P | Kuhiiwa | Secondary and primary forest |

| BS80 | Arecaceae | Cocos nucifera L. | Blood clots | y nut | Heated | Oral | P | Moo | Tropical climates |

| BS81 | Poaceae | Bambusa sp. | Swollen testes | ND | ND | ND | P | Kutapaku | Moist areas of forest |

| BS82 | Athyriaceae | Diplazium proliferum (Lam.) Thouars. | Painful urination | yL | Eaten fresh | Oral | P | Diriiko | Riverbanks |

| BS83 | Rutaceae | Evodia elleryana F. Muell. | Fever | L | Mashed | Wash | P | Kurih | Rainforests |

| BS84 | Marattiaceae | Angiopteris evecta (Forst.) Hoffm. | Cold | yL | Infusion | ND | M | Uwahaku | Fern in moist areas near village |

| BS85 | Malvaceae | Commersonia bartramia (L.) Merr. | Pregnancy | L | ND (“extract”) | ND | P | Panoru | Secondary forest |

| BS87 | Rubiaceae | Myrmecodia echinata | Labour | ND | ND | ND | P | Kuhro | Treetops |

| BS89 | Lamiaceae | Plectranthus scutellarioides (L.) R. Br. | Leprosy | L | ND (“extract”) | ND | P | Mongko | Cultivated |

| BS90 | Musaceae | Musa paradisica L. | Pre-leprosy rash | ND | ND | ND | P | Kouhrai-murih | Rainforest |

| BS91 | Poaceae | Bambusa sp. | Pre-leprosy rash | ND | ND | ND | P | Pihi | Rainforest, cultivated |

| BS92 | Aristolochiaceae | Aristolochia tagala Cham. | Headache | L | Pounded | Massage | P | Ku’ukuing paupau | Primary and secondary forest |

| BS93 | Verbenaceae | Vitex cofassus Reinw. ex Blume | Centipede bite | ND | ND | ND | P | Muniing | Primary forest and undisturbed places |

| BS95 | Euphorbiaceae | Codiaeum variegatum (L.) Blume | Leprosy | ND | ND | ND | P | Honno-Mung | Cultivated |

| BS96 | Cyperaceae | Cyperus rotundus L. | Toothache | Stem | Pounded | Mouth wash | P | Pihirototoka-pehhita | Rainforested land |

| BS97 | Verbenaceae | Vitex trifolia L. | Severe productive cough | L | Infusion | Oral | P | Tari-raapito | Rare |

| BS98 | Leeaceae | Leea indica Merr. | Leprosy | S | ND | Topical | P | Kosi-Kasi | Thick rainforest |

| BS99 | Vitaceae | Cayratia sp. | Centipede bite | Sap | Fresh | Topical | P | Pimuai | Abandoned garden sites |

| BS100 | Moraceae | Ficus wassa Roxb. | Labour pains | ND | ND | ND | Moo | Masi | Weed grows in cocoa plantations |

| BS101 | Myrtaceae | Syzygium sp. | Headache and fever | L | ND | ND | P | Turoro | Muddy places |

| BS106 | Piperaceae | Piper sp. | Leprosy | B | ND | ND | P | Urugoto, Minawatong | On trees |

| BS107 | Araliaceae | Polycias sp. | Pain | L | Heated | Massage | P | Kuhausi | Cultivated |

| BS108 | Myrtaceae | Syzygium sp. | Tongue cancer | L | Decoction | ND | P | Nuuwaari | Rainforest |

| BS109 | Fabaceae | Mucuna novo-guineensis Scheff. | Productive cough | ND | ND | ND | ND | Aiya, Aiwa | Rainforests |

| BSX3 | Moraceae | Ficus sp. | Painful sore which swells up & exposes flesh | ND | ND | ND | P | Tupare | Grows on trees |

| BSX4 | Fragraceae | N.A. | Fresh wound | yL | Mashed | Topical | P | Kipo | Secondary forest |

| BSX6 | Asclepiadaceae | Hoya sp. | Problems with milk production in new mothers | Vine, L | Succus | Oral | P | Nunororu | Rainforest |

| JW01 | Asteraceae | Mikania micrantha Kunth | Wounds and ulcers | L; Vine | Infusion; succus | Topical | PA | Kominis1 | Abundant in secondary forest |

| JW02 | Verbenaceae | Premna serratifolia L. | Headache; malaria | L; Bark | Decoction; fresh | Oral; massage | PA | Kaaru1 | Widely distributed near village |

| JW03 | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia racemigera F. Muell. | Cough, dysuria (UTI) | Stem | Succus (small amount of water added) | Oral | PA | Kokoru1 | Forest, near village |

| JW04 | Malvaceae | Kleinhovia hospital L. | Cough, dyspnea, asthma | yL | Infusion | Oral | PA | Paragi1 | Forest |

| JW05 | Musaceae | Musa schizocarpa Simmonds | Asthma | Latex | Fresh | Oral | PA | Nutai1 | Forest |

| JW06 | Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica L. | Diarrhea; abdominal pain, constipation and loss of appetite (typhoid) | L; Bark | Decoction; infusion | Oral; Massage | PA | Paisi1 | Forest |

| JW07 | Arecaceae | Areca catechu L. | Cough | Bark | Infusion | Oral | PA | Kogi1 | Cultivated, forest |

| JW08 | Urticaceae | Poikilospermum sp. | Labor induction; boils | Sap | Succus; infusion | Oral; bath | PA | Kamairengke nano1 | Crawling plant in forest |

| JW09 | Marantaceae | Donax cannaeformis Rolfe | Filariasis | L; Stem | Heated; oncoction | Massage; oral | PA | Marita1 | Widely distributed shrub |

| JW10 | Costaceae | Costus speciosus Sm. | Filariasis; bullet wounds; pigs w/dog bite; tooth decay/gingivitis | Stem; Stem; Stem; Root | Concoction; succus; succus after heating and crushing; fresh | Oral; topical; topical; chewed | PA | Memeto1, Maiangata2 | Forest |

| JW11 | Convolvulaceae | Merremia peltata (L.) Merr. | Filariasis, elephantitis of scrotum; cut wounds, boils and centipede bites; Flu and cold; fever | Sap | Concoction; fresh; succus; infusion | Oral; topical; oral; bath | PA | Turaru1 | Crawling vine |

| JW12 | Convolvulaceae | Merremia sp. | Filariasis, elephantitis of scrotum and breast | Sap | Concoction | Oral | PA | Kakatanobi1, Kogurotorogu2 | Crawling vine |

| JW13 | Myristicaceae | Horsfieldia irya Warb. | Watery diarrhea and stomach ache | Stem or Shoot | Fresh | Chewed | PA | Kamukamu1 | Forest |

| JW14 | Dioscoriaceae | Dioscorea alata L. | Hypertension, obesity, migraines, and consistent transient paralysis; pain & difficulty in urinating | Root | Decoction | Oral | PA | Husisi1 | Crawling and climbing vine |

| JW15 | Verbenaceae | Faradaya splendida F. Muell. | Pneumonia | Sap | Succus | Oral | PA | Kotomekai1 | Crawling and climbing plant in forest |

| JW16 | Piperaceae | Piper sp. | Centipede bite; cough; migraine | Stem; L; Stem | Succus; infusion; crushed | Topical; oral; inhaled | PA | Torunoki1, Tururoki2 | Crawling plant in cleared places, sides of tracks |

| JW17 | Poaceae | Bambusa sp. | Permanent contraceptive | Root | Concoction | Oral | PA | Kutabagu1 | Clearings |

| JW18 | Moraceae | Ficus adenosperma Miq. | Phobic disorder and fever | yL | Concoction | Bath | PA | Turore1 | Along riversides |

| JW19 | Urticaceae | Elatostema parasiticum (Blume) Blume ex H. Schroet. | Phobic disorder and fever | L | Concoction | Bath | PA | Simaya1 | Stones and riverbanks of Argura river |

| JW20 | Fabaceae | Cassia fistula L. | Fungal skin infections (Grille) | L | Crushed to release succus | Topical | PA | Ombuu1 | Near village |

| JW21 | Gnetaceae | Gnetum costatum K. Schum. | Otitis media | Sap | Fresh | Topical | PA | Akamu1 | A climbing vine in forest |

| JW22 | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia peekelii Valeton | Migraines; cough | Stem/Shoot | Infusion; infusion (w/little water) | Bath; oral | PA | Kangkuruu1, Rauraunu2 | Forest |

| JW23 | Marattiaceae | Angiopteris evecta (Forst.) Hoffm. | Dysentery | Root | Concoction | Chewed | PA | Morosi1 | Forest fern |

| JW24 | Commelinaceae | Commelina paleata Hassk. | Conjunctivitis | L | Succus | Topical | PA | Utamoitai2 | Moist areas along Argura river |

| JW25 | Davalliaceae | Davallia solida (G. Forst.) Sw. | Scurvy (gingivitis) | Stem | Infusion | Gargle | PA | Raaka1 | Creeping plant grows on shady trees |

| JW26 | Aspleniaceae | Asplenium nidus L. | Fire leaf burns | yL | Crushed | Massage | PA | Rokobo1 | Forest on trees with rough bark |

| JW27 | Sapindaceae | Harpullia sp. | Paralysis, migraine, asthma | yL; Bark | Decoction; infusion | Oral | PA | Korukopuu1 | Forest |

| JW28 | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia sp. | Hemetemesis | Rhz | Fresh | Chewed | PA | Pagana1 | Cultivates |

| JW29 | Blechnaceae | Stenochlaena palustris (Burm.) Bedd. | Sore and red eyes with discharge | L | Decoction | Topical, bath | PA | Nabata1 | Creeping plant on forest trees |

| JW30 | Poaceae | Paspalum sp. | Toothache | Root | Fresh | Chewed | PA | Kaino1 | Wild in cocoa plantations |

| JW31 | Palmae | Ptychosperma kasesa Lauertb. | For permanent contraceptive | Shoot; Root | Chewed with betelnut; concoction | Chewed; oral | PA | Mikituku4 | Forest |

| JW32 | Anacardiaceae | Semecarpus sp. | Permanent contraceptive/Abortion | Bark; Root | Infusion; concoction | Oral | PA | Nannai potuoramiu1 | Forest |

| JW33 | Poaceae | Paspalum conjugatum Bergius | Centipede bite | L | Concoction | Topical | PA | Masi1 | Forest |

| JW34 | Verbenaceae | Clerodendrum fragrans | Centipede bite; dysuria (UTI) | Sap | Concoction; succus | Topical; oral | PA | Kurumu3 | Crawling and climbing plant in clearings and along roadsides |

| JW35 | Piperaceae | Piper peekelii C.CD. | Malaria | L | Fresh | Massage | PA | Urugu1 | Crawling plant in forest |

| JW36 | Annonaceae | Cananga odorata (Lam.) Hook. f. and Thomson | Malaria | L | Fresh | Massage | PA | Rauro1 | Rainforest Orukuu |

| JW37 | Euphorbiaceae | Macaranga sp | Induction of labor | Bark (sap) | Sap added to water | Oral | PA | Pauru1 | Forest |

| JW38 | Moraceae | Ficus copiosa Steud. | Backache (arthritis) and malaria | Bark; Bark & L | Infusion; concoction | Oral, bath | PA | Tunanai1, Tuarai1 | Forest, clearings |

| JW39 | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia modesta K. Schum. | Dysentery; planar wart | Root | Concoction; concoction | Chewed; topical | PA | Kumugu3 | Widely distributed in light forest |

| JW40 | Agariaceae | Agaricus sp | Plantar wart | Whole | Heated | Topical | PA | Kantoki1 | Dry coconut fronds, moist dead wood |

| JW41 | Zingiberaceae | Hornstedtia scottiana K. Schum. | Boils, sores and ulcers, vomiting and arthritis (backache) | Seed; L | Fresh; heated | Topical, massage | PA | Asiaru1, GorgorP | Common shrub near villages |

| JW42 | Orchidaceae | Grammatophyllum scriptum (L.) Blume | For mothers who delivered but not lactating | Stem | Crushed and squeezed to release succus | Oral | PA | Paarai1 | On trees, wild and cultivated |

| JW43 | Lauraceae | Cryptocarya apamaefolia Gamble | Headache | Bark | Fresh | Massage | PA | Kabakuu1 | Korukoguoto bau forest |

| JW44 | Selaginellaceae | Selaginella cirnum | Centipede bite | L | Infusion | Oral | PA | Kamago1 | Korukoguoto bao forest |

| JW45 | Verbenaceae | Geunsia sp. | Hemetemesis | Bark | Succus | Oral | PA | Tomarai1 | Light, bushy areas of forest |

| JW46 | Flacourticaceae | Homalium foetidum Benth. | Malaria and Jaundice | Bark, L | Concoction | Bath | PA | Misiagiro1 | Forest |

| JW47 | Loganiaceae | Fagraea obovata Griff. | Malaria | L | Concoction | Bath | PA | Ketupore1 | Forest |

| JW48 | Anacardiaceae | Semecarpus abenscens | Anemia (jaundice) ; (gun) wound healing | L; Sap | Concoction; concoction | Oral | PA | Uramiu1 | Lowland forest and cleared areas |

| JW49 | Fabaceae | Pterocarpus indicus Willd. | Anemia; wounds/bleeding; induce labor; eye infections | yL; yL; yL; Shoot & yL | Concoction; concoction; infusion; squeezed gently | Oral; oral; oral; topical | PA | Okino1 | Forest |

| JW50 | Arecaceae/Palmae | Cocos nucifera L. | Injury wounds | unripe nut juice | Boiled | Oral | PA | Muuo1, KokonasP | Cultvated |

| JW51 | Chrysobalanaceae | Cyclandrophora laurina (A. Gray) Kosterm. | Bone fractures | Bark | Concoction | Chewed, massage | Mon | Osito5, Sito1 | Forest |

| JW52 | Sapindaceae | Pometia pinnata J.R. Forst. and G. Forst. | Bone fractures; heat rashes | Bark, L | Concoction; infusion | Chewed, massage; bath | Mon | Mougoru1 | Forest |

| JW53 | Gnetaceae | Gnetum gnemon L. | Bone fractures | Bark | Concoction | Massage | Mon | Aara5 | Forest |

| JW54 | Araceae | Colocasia esculenta (Linnaeus) Schott | Used after delivery to shrink fundus | L | Decoction | Oral | Mon | Utukau1 | Forest in moist cleared areas |

| JW55 | Myrtaceae | Psidium guajava L. | Chicken pox and measles; alcohol intoxication; rhinitis | yL | Decoction; fresh; fresh | Bath; oral; chewed | PA | Kuopa1 | Cultivated |

| JW56 | Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. | Malaria; cough; hypertension | L; Seed; F & yL | Decoction; infusion; decoction | Oral | Mon | Kaioke5, Porpor1 | Cultivated |

| JW57 | Lecythidaceae | Barringtonia novae-hiberniae Lauterb. | Arthritis | Bark | Concoction | Chewed | Mon | Aiai kuii5, PauP | Cultivated |

| JW58 | Arecaceae | Gronophyllum chaunostachys (Burret) H.E. Moore | Backache (arthritis) | Bark | Concoction | Chewed | Mon | Kiritu5 | Forest and cultivated |

| JW59 | Myrtaceae | Syzygium malaccense (Linnaeus) Merrill and L. M. Perry | Productive cough | yL | Succus | Oral | PA | Karikau1, Raurau5, LaulauP | Cultivated |

| JW60 | Leeaceae | Leea sp. | Conjunctivitis | L | Heated | Massage | PA | Marakakas1 | Abandoned gardens |

| JW61 | Fabaceae | Mucuna novo-guineensis Scheff. | Abdominal pain, constipation and loss of appetite (typhoid) and arthritis | Sap | Concoction | Massage, oral | PA | Mosimosi1 | A crawling vine in rainforest and moist areas |

| JW62 | Anacardiaceae | Semecarpus sp. | Malaria | Bark | Concoction | Bath | Mon | Innepuu5 | Rainforest |

| JW63 | Fabaceae | Vigra sp. | Malaria | Sap | Concoction | Bath | Mon | Pirigiamoro1, Pirigianomu5 | Forest vine on trees |

| JW64 | Lamiaceae | Coleus scutellarioides (L.) Benth. | Malaria | L | Concoction | Bath | Mon | Meme5 | Newly cleared areas |

| JW65 | Solanaceae | Solanum torvum Swartz | Malaria | L | Concoction | Bath | Mon | Kabatokopau5 | New clearings and gardens |

| JW66 | Rubiaceae | Uncaria sp. | Abdominal pain, constipation and loss of appetite (typhoid) and arthritis | Bark | Concoction | Massage, oral | PA | Morokengke Kata1 | Forest along rivers |

| JW67 | Zingiberaceae | Alpinia sp. | Malaria | L | Concoction | Bath | Mon | Nokio5 | Forest near village |

| JW68 | Euphorbiaceae | Macaranga aleuritoides F. Muell. | Breast abscess | L | Heated | Massage | PA | Apapai1 | Newly cleared areas or lowland forest |

| JW69 | Araceae | Alocasia sp. | Centipede bite, fire leaf burn, jellyfish sting | Stem | Scraped, mixed with lime | Topical | PA | Orukuu5 | Abundant in forest along riverbanks |

| JW70 | Araliaceae | Osmoxylon micranthum (Harms) Philipson | Abortion | Bark | Decoction | Oral | Mon | Potumai5 | Forest |

| JW71 | Apocynaceae | Alstonia scholaris (L.) R. Br. | Infertility (female); cough | Root; Sap | Succus; water added to sap | Oral | Mon | Kenumau5 | Forest |

| JW72 | Moraceae | Ficus botryocarpa Miq. | Menorrhagia | L | Infusion | Oral | PA | Innina1 | Forest, clearings |

| JW73 | Myrtaceae | Syzygium sp. | Diarrhea, cough, alopecia, malnutrition and anemia | Bark | Decoction | Oral | Mon | Paguau5, Karapurinio5, Kukuinu1 | Forest, and cultivated |

| JW74 | Flagellariaceae | Flagellaria indica L. | Conjunctivitis | Sap, L | Fresh; heated | Topical, massage | Mon | Kere1, Kereku5 | A vine in Forest |

| JW75 | Malvaceae | Hibiscus manihot L. | To facilitate quick delivery for an expecting mother | L | Infusion | Oral | Mon | Markuii5, AibikaP | Cultivated |

| JW76 | Malvaceae | Hibiscus tiliaceus | Watery diarrhea | L | Infusion | Oral | Mon | Bambaruu5, Wild mangasP | Cultivated |

| JW77 | Passifloraceae | Passiflora foetida L. | Cough | yL | Infusion | Oral | PA | Ropu1 | Creeping vine in low cleared or grassy areas, along roads and rivers |

| JW78 | Fabaceae | Mimosa pudica L. | Injury swelling | L | Fresh | Massage | Mon | Pamparagansi 5 | Along roads |

| JW79 | Malvaceae | Sida rhombifolia L. | Toothache; helps baby learn to walk quickly; erectile dysfunction | Stem; Root; Root | Fresh, concoction; concoction | Chewed; massage; massage | Mon | Tugia2, BroomstickP | Along roads and highways |

| JW80 | Poaceae | Eleusine indica L. | Erectile dysfunction | Root | Concoction | Massage | Mon | Unsigu5 | Margin or cleared areas, roads |

| JW81 | Urticaceae | Pipturus sp. | Diabetes | yL | Infusion | Oral | Mon | Kutope1 | Forest |

| JW82 | Leguminosae | Albizia falcataria (L.) Fosberg. | Chicken pox | Bark | Concoction | Bath | Mon | Kugupina2 | Clearings |

| JW83 | Mimosoideae | Albizia sp. | Chicken pox | Bark | Concoction | Bath | Mon | Tugurugu2 | Clearings |

| JW84 | Asteraceae | Ageratum conyzoides L. | Very painful earache (otalgia) | L | Heated and crushed to release succus | Topical | Mon | Aurai5 | A weed in clearings/gardens |

| JW85 | Amaryllidaceae | Crinum asiaticum L. | Heart burn | L | Decoction | Oral | PA | Poga1 | Cultivated |

| JW86 | Zingiberaceae | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Centipede bite; abdominal pain, constipation and loss of appetite (typhoid) | Rhz | Crushed; concoction | Topical; oral, massage | PA | Piriani1, Iaa2 | Cultivated |

| JW87 | Fabaceae | Derris sp. | Abdominal pain, constipation and loss of appetite (typhoid) and arthritis | Sap | Concoction | Massage, oral | PA | Ubaipokaruka u1 | Rainforest climbing vine |

| JW88 | Palmae | Calamus hollrungii Becc. | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, constipation and loss of appetite (typhoid) | Sap | Concoction | Massage, oral | PA | Kanta1 | Cane plant grows well in forest |

| JW89 | Saurauiaceae | Saurauia sp. | Abdominal pain, constipation and loss of appetite (typhoid) and arthritis | F | Concoction | Massage, oral | PA | Ararum1 | Forest |

| JW90 | Rutaceae | Euodia hortensis J. R. & G. Forst | Deeps cuts and wounds | L | Heated | Topical | PA | Siusiu1, Temo1 | Cultivated |

The following shorthand notations were used:

Plant part : F =Flower; L = Leaves; Rhz = Rhizome; y = young/new, S = Seeds.

Village - Buin, South Bougainville: PA – Pariai, Mon=Mongai; Siwai District, Bougainville: M= Motirui; Moo = Mo’o kupu, P- Panakei, K – Kapana, Mor – Morohai.

Local name - Siwai Language: no superscript; Telei Dialect: 1=North Mokeruui, 2=Central Mokeruui, 3=Kungara, 4=Mokeruui, 5=South Mokeruui. Common Language: P=Pidgin.

Multiple uses for Condition or Disease; When separated by semicolons Part, Preparations and Applications are respectively matched (sequentially mapped).

Concoction=a combination of herbs, decoction=extraction by boiling, succus=expressed juice, infusion=steeping of plants in water.

Photographs of the plants used medicinally by the herbal practitioners were taken at the time of interview and descriptions of plant morphology and habitat were recorded. Samples of the plants useful for identification (flowers, fruits or nuts, twigs with leaves) in addition to the parts used medicinally were harvested, dried and compressed in newspapers. Newspapers were changed daily until they remained dry after compression. Plants, photographs, and descriptions relevant to a specific plant were assigned a voucher number and returned to UPNG for identification by the Herbarium Staff. Mounted herbarium specimens were later deposited at the UPNG Herbarium for record and reference purposes.

Before the end of the scholastic year individual student authored reports were completed under supervision, as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Pharmacy. The data concerning plant use were also entered into the proprietary UPNG Traditional Medicines Database that records, in addition to plant medicinal use, information concerning source individuals and communities in order to recognize and trace the traditional knowledge intellectual property. Guidelines regulating benefit sharing for intellectual property and accession of the database have been developed at UPNG, operating under the current UPNG benefit sharing model, which is generic and applicable to many areas of natural products research. It includes guidelines concerning intellectual property rights and benefits sharing, and has been approved by the PNG government. The published student reports were the principal data sources for this report.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Diversity of plant use in Siwai and Buin

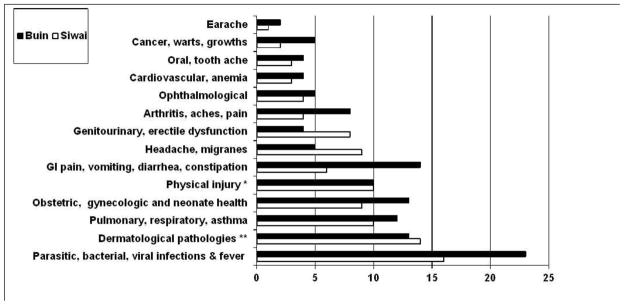

Diseases in southern Bougainville are often characterized as “normal” (common) illnesses, illnesses caused by spirits or illnesses caused by sorcery. The latter two categories of illnesses are often treated by spiritualists. No spiritualists were interviewed for this report; consequently the plant use described here focuses on common illnesses. Figure 1 shows the different disease conditions and the number of medicinal preparations used to combat them. The explicit use of various plants reflects, to some extent, the commonness of maladies. In Papua New Guinea respiratory problems, malaria and other infections, physical injury, diarrhea and obstetrical and gynecological difficulties are extremely common and many plants are used to treat these health problems.

Figure 1.

Summary of common therapeutic indications for medicinal plants in the Siwai and Buin areas of Bougainville, grouped by organ system. Total number of plants: Siwai 100; Buin 90. In both areas many plants had multiple uses reported. * Includes: broken bones, sprains, dislocations, bruises, cuts. ** Includes: insect bites, stings, burns, itching, fungal infections, scabies, boils, sores, rashes, alopecia

Survey data presented in Table 1 include: voucher ID, plant family, genus and species, medical indication, plant part, mode of preparation, mode of application, village, local name/s and dialects, and habitat. Scientific data concerning cultural practices in Bougainville has been particularly hard to obtain because of the social disruption in the area for the last couple decades. This article illustrates several interesting points concerning medicinal plant use in Southern Bougainville. In the geographically neighboring areas of the Siwai and Buin language groups one would expect considerable overlap of plant use because of the presumed presence of common indigenous plants and because of the presumed historical dissemination of plant use knowledge. It is true that 18 of the 77 [23%] plants identified to species level from Siwai were also reported as medicinal in Buin. However, even with the apparent commonality in health conditions treated with plants (Figure 1), there was much less consistency in the specific uses of the plants than one might expect. Only Psidium guajava leaves and Mikania micrantha leaves were prepared the same way and used for the same indications in both Siwai and Buin. Additionally, only Ficus adenosperma was used in both areas for the same specific indication, and Pterocarpus indicus was the only other plant prepared in similar fashion in both areas. Although these surveys were not intended to render exhaustive or complete lists of all plants used medicinally in the regions, the fact that the large majority of specific plant uses were not shared in common amongst the two regions was surprising.

3.2 Common practices in Siwai and Buin in plant preparation and application

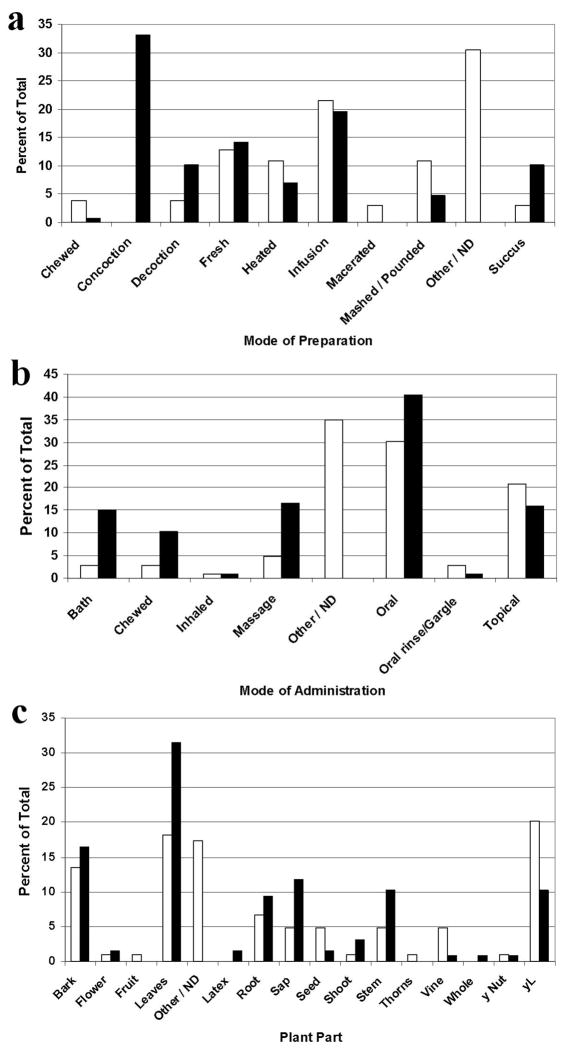

Overall, similarities exist between the two communities in the reported methods of plant preparation, administration and plant parts used most frequently. Figure 2a shows that the percentage of plants prepared by various traditional methods is roughly similar in the Siwai and Buin. The notable exception to this observation is that concoction was reported as the most common method of preparation in Buin, while this category of preparation was not included in the Siwai report in which the methods of preparation were not consistently documented. Other methods of preparation including fresh plant leeching in water, direct application, heating, decoction and succus are frequently used in both locales. In both communities, oral consumption was reported to be the most common method of administration [Figure 2b]. In both communities, leaves were the most frequently used plant part, although the frequent use of other parts, particularly bark, was reported (Figure 2c). The majority of medicinal preparations reported used in these communities consist of one plant, the use of concoctions being less common.

Figure 2.

Comparison of a) Mode of Preparation, b) Mode of Administration and c) Plant Part utilized between [□] Siwai and [■] Buin regions of the Bougainville Autonomous Region. ND: not determined.

3.3 Plants used both in Siwai and Buin

Of the 18 medicinal plants identified to species level that are reported as used medicinally in both Bougainville regions, six [33%] are also harvested or cultivated for food. These are Barringtonia novae-hiberniae, Cocos nucifera, Ficus copiosa, Magnifera indica, Psidium guajava and Solanum torvum. Cocos, (coconut), Magnifera (mango), Psidium (guava) and Solanum (turkey berry) have many reported medicinal uses in the literature. On the other hand, B. novae-hiberniae (cut nut) and F. copiosa (an edible fig) are not represented in widely available scientific literature for their medicinal uses. In Buin B. novae-hiberniae is used for arthritis and for angina in Siwai. In Milne Bay, PNG, an infusion of leaves of members of the Barringtonia genus is used to relieve stomach-ache (Holdsworth, 1977). F. copiosa is used for arthritis and malaria in Buin, in Siwai it is used for boils. Fresh fruit latex of F. copiosa is also used in East New Britain topically to treat boils (WHO, 2009), and its leaves are also crushed and rubbed on stomach to relieve stomachache (Holdsworth, 1977).

Other plants used medicinally in both the Buin and Siwai regional areas include Ageratum conyzoides, Alstonia scholaris, Angiopteris evecta, Ficus adenosperma, Hibiscus tiliaceus, Hornstedtia scottiana, Macaranga aleuritoides, Merremia peltata, Mikania micrantha, Mucuna novoguineensis, Premna serratifolia, and Pterocarpus indicus. Ageratum conyzoides, commonly known as billygoat weed, chick weed or white weed, is an invasive plant from South America; it is used worldwide orally and topically in variety of folk remedies (e.g., Tote et al., 2009 and Nour et al., 2101). In Buin it is taken orally for diarrhea and headache, in the Siwai area it is applied topically for earache. It is used elsewhere in PNG (Holdsworth, 1977) for diarrhoea (Oro Province and East New Britain) and topically on the forehead to treat headache (Manus Island and East New Britain). In addition, juice from moistened leaves is applied directly into sore eyes and it is used to stop vomiting in East New Britain (Holdsworth, 1977). Crushed leaf sap is used to treat head lice in other parts of PNG (WHO, 2009).

Alstonia scholaris is used in Bougainville to counter infertility (Buin) and to treat diarrhea (Siwai). An infusion of crushed boiled leaves is used in Central Province to treat cough, while on Normanby Island the stem sap is used for that same purpose (Holdsworth, 1977). Stem sap is also reported to be used elsewhere on Bougainville against fever and topically for ulcers in Milne Bay. Bark is used in Central Province against malaria (Holdsworth, 1977). It is also used as a contraceptive (fresh leaves or abortifactant (dried bark sap) by women in other regions of PNG (WHO, 2009). Alstonia scholaris is a plant widely used in both India and China for numerous purposes including anti-diarrheal and anti-fertility (Arulmozhi et al., 2007).

Angiopteris evecta root is chewed for dysentery in the Buin area and its leaves are used to treat colds in the Siwai region. Angiopteris evecta extracts have been shown to have hypoglycemic effects in mice (Hoa et al., 2009).

Ficus adenosperma is used for fever in Buin and Siwai areas, it is also used in Buin to treat fear of death. The fresh root chewed for malaria in other parts of PNG; it has been introduced to Eastern Highlands from the Madang coast (Holdsworth, 1977).

Hibiscus tiliaceus is used to treat watery diarrhea in Buin but for productive cough in Siwai. A filtrate from bark scrapings is used against severe cough and tuberculosis in Manus Island (Holdsworth, 1977). Sap or decoction from leaves is drunk to cure sore throat in Sepik and Central Province, respectively (Holdsworth, 1977). Crushed young leaf sap used to facilitate childbirth in PNG (WHO, 2009) and in Vanuatu for menorrhagia (Bourdy and Walter, 1992).

There is little in the literature concerning Hornstedtia scottiana, a member of the ginger family that is found in eastern Papua New Guinea and northern Australia. In Buin it is applied topically for skin sores, backache and vomiting, in Siwai it is used topically and orally for labor pains.

Macaranga aleuritoides is used for breast abscesses in Buin and cuts in Siwai, it is found relatively widely in Papuasia but other specific medicinal uses are not reported in the literature. Bark from Macaranga sp. is used to treat cough and leaves have also been reported to be used for boils, bruises and headache elsewhere in Bougainville and in Milne Bay (Holdsworth, 1977).

Merremia peltata is a climbing vine that is an invasive species in many Pacific Islands (Leu, et, al., 2008, Bourdy and Walter, 1992). On Manus Island sap from stems is used to treat cuts, while young leaves are placed on sores to provide relief (Holdsworth, 1977). In Buin it is used for filariasis, elephantitis of scrotum, cut wounds, cough, fever, rhinitis (flu & cold), boils and centipede bites and in Siwai for eye inflammation and bullet wounds.

Mikania micrantha is another fast growing invasive vine species that is used to treat wounds in both Buin and Siwai, and also for ulcers in Buin. The stem is also used in a concoction against cold, headache and stomach aches in Eastern Highlands (Holdsworth, 1977). It is used for a wide variety of ailments in the Eastern and Western hemispheres. Antibacterial activity has been reported for it (Anupam et al., 2008) and antimicrobial constituents have been isolated from it (Facey et al., 1999).

There is little on Mucuna novoguineensis in the literature relevant to its medicinal use, although other members of the genus are used widely for a number of ailments. In the Buin region it is used variously for abdominal pain, constipation and loss of appetite, typhoid, and arthritis, in the Siwai area it is used to treat productive cough. Mucuna sp. are used to treat stomach ache (vine stem sap) and headache (root sap) in Sepik (Holdsworth, 1977).

Premna serratifolia is a medicinal plant used in many regions of the South Pacific (College of Micronesia, 2011, Desrivot et al., 2007). P. integrafolia is used variously for cough, headaches and fevers in Sepik and on Normanby Island (Holdsworth, 1977). Premna serratifolia is used for headache and malaria in Buin and for dysentery in Siwai.

Pterocarpus indicus is a large tree common in much of Eastern Asia and the Southern Pacific. A cursory literature search of the CAPLUS® database reveals that it is used in a number of Chinese preparations for a variety of indications. Young leaves chewed in New Britain for stomach ache and in the Central Province leaves are boiled and the decoction drunk for malaria. Treatment of headache with flower infusion or with boiled leaf bath has also been documented in the Central Province (Holdsworth, 1977). In Milne Bay the bark is squeezed to release juice for topical administration into sores, and a leaf infusion is used to treat headache elsewhere in Bougainville (Holdsworth, 1977). P. indicus is used in Buin and Siwai for eye problems (including eye infections, blepharitis, stye and chalazion). In Buin it is also used for anemia, wounds, jaundice, and to induce labor. In Siwai it is also used for dysentery, haematouria, and centipede bite.

4. Conclusions

Bougainville’s cultural distinctiveness is often attributed to different ethnic traditions and to matrilineal social structures (particularly concerning hereditary land rights; Connell, 2005). Douglas Oliver (as cited in Connell, 2005) has written that “nothing short of an encyclopedia could fully describe the great variety of social forms and religious practices of all the Solomons.” Indeed, “marked tribal differences … spell despair for anyone seeking a simple formula for understanding the Solomonese as an entity.” Almost universally throughout Southern Bougainville, rural people are subsistence farmers who reside in hamlets consisting of related families. Although “remarkably uniform” in settlement types, dress, diet and implements (Oliver, N.d.) the Bougainvillean cultures are far from uniform, with existing tensions between groups (A. Regan, 1998). According to Ogan (as cited by Regan, 1998) the “key differences are language, kinship and leadership systems”. How the tribes distinguished amongst themselves was addressed by Nash and Ogen (1990): “The Nagovisi and Nasioi in precolonial times undoubtedly knew neighbors whose culture and language differed in some degree from their own.” They “spoke of cultural differences distinguishing them from their neighbors”, for instance “the excesses of rivalry and competition in feasting” among the Siwai. Historically, in Southern Bougainville there was no sense of the range of other ethnic groups, no recognition of other traditions as cultural entities, and no sense of Bougainville as a geographical entity.

Further dividing the ethnic groups in Bougainville was the intertribal warfare that prevailed nearly everywhere on the island until well after colonial contact (Douglas Oliver, N.d.). Intergroup fighting in Siwai continued into the 1920s and such conflict was within living memory of many groups in the 1980s (Regan). These overall perceptions paint a picture of functionally separate cultural traditions represented by the different language groups of Southern Bougainville.

Currently, the Siwai people remain deeply traditional. They value their customs and want them passed on to next generation. They speak dialects locally called Su’una’a and Pikei. Land is inherited through maternal lineage, as long a woman is living in the immediate family. A traditional gender dichotomy exists with women forbidden to wash upstream of men or to enter the “HausKaramut”- a ceremonial house for men and boys. In contemporary society shell money (shells of different colours and sizes), modern currency (Kina) as well as garden or store food is used to pay bride price. Recently, people are now moving close to roadside, Buka, the provincial capital being about 6 hours drive by road.

Currently the people of Buin District speak Telei, the lowland community speaking a dialect comprehensible to those inland. Although described as matriarchal in the early 1900s (Oliver, N.d.), Buin inhabitants claim to be a purely patrilineal society. Perhaps this transition to a patrilineal society has occurred recently, or perhaps the difference is semantic, as Oliver described for the Siwai (Oliver, 1949) where mechanisms did exist for a son to inherit his father’s matrilineal land. Bride price mainly comprises of pigs, foodstuff and a smaller amount of cash than is common in other parts of PNG. Buin people are still largely rural, residing in villages. Only people in employment live in the towns. Transportation is mainly by passenger motor vehicles and most economic activity is concentrated in Buka about 8 hours drive by road from Buin. Before the crisis education was very important to Buin people, this is picking up again in the current peace.

We hypothesize that the historical cultural separation, in combination with variation in plant endemism, might explain the differences in the plants used and the spectrum of specific plant uses between the Siwai and the Buin regions. In fact, our observations mirror those of early explorers in that we document “remarkably uniform” in the diseases treated, the methods of medicinal plant preparation, mode of administration and plant parts used, while we see “marked tribal differences” in the individual plants used and their particular medical applications.

The medicinal plant surveys reported here are the product of collaboration amongst the faculty at UPNG with support provided by the University of Utah, the Fogarty International Centre of the NIH, USA (Barrows et al., 2009), and the PNG Ministry of Health. The survey reports represent university training exercises that are components of a larger integrated strategy that is under way to meet the health care needs of citizens of PNG. The traditional medicines survey project complements programs instituted by the PNG Ministry of Health to promote the use of efficacious herbal remedies amongst populations in need of health care intervention. The finding that the same plants can have radically different uses in locales separated by language, custom and geography reveals the need for information sharing amongst practitioners. The Department of Health Taskforce on Traditional Medicines has already facilitated traditional healer associations in several provinces and basic manuals on diagnosis and plant use have been drafted. The information gathered and preserved in the survey effort will ultimately contribute to a more integrated medical treatment spectrum, moving toward a combined health care approach that integrates effective and accessible traditional practices with Western protocols.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the traditional healers and villages of Buin District, South Bougainville: Pariai, Mongai, Turutai and Tabago and of Siwai District, Central Bougainville: Motirui, Mo’o Kupu, Panakei, Kapana, Morohai, Konga, Kapana, Romokoo, Ununai, Rabauru, and Noonatu for their invaluable input which made this publication possible. We also acknowledge UPNG and FRI Herbarium staff for assistance in identification of medicinal plant vouchers. This work was funded by US NIH support through the Fogarty International Center, ICBG 5UO1T006671. Dr. Rai, Dr. Matainaho and students were also supported by the following agencies for this work: National Department of Health, Papua New Guinea and University of Papua New Guinea.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare they have no conflict of interest concerning the work reported here.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anupam G, Kanti DB, Arup R, Biplab M, Goutam C. Antibacterial activity of some medicinal plant extracts. Journal of Natural Medicines. 2008;62:259–62. doi: 10.1007/s11418-007-0216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arulmozhi S, Mazumder PM, Ashok P, Narayanan LS. Pharmacological activities of Alstonia scholaris Linn. (Apocynaceae) - a review. Pharmacognosy Reviews. 2007;1:163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Asher RE, editor. The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1994. p. 2924. [Google Scholar]

- Barrows LR, Matainaho TK, Ireland CM, Miller S, Carter GT, Bugni T, Rai P, Gideon O, Manoka B, Piskaut P, Banka R, Kiapranis R, Noro JN, Pond CD, Andjelic CD, Koch M, Harper MK, Powan E, Pole AR, Jensen JB. Making the Most of Papua New Guinea’s Biodiversity: Establishment of an Integrated Set of Programs that Link Botanical Survey with Pharmacological Assessment in “The Land of the Unexpected”. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2009;47:795–808. doi: 10.1080/13880200902991599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beehler BM, editor. Papua New Guinea Department of Environment and Conservation. Vol. 2. Boroko: Papua New Guinea; 1993. Papua New Guinea Conservation Needs Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Bougainville. 2011 http://wikitravel.org/en/Bougainville September 27 2011.

- Bourdy G, Walter A. Maternity and Medicinal Plants in Vanuatu: The Cycle of Reproduction. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1992;37:179–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90033-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- College of Micronesia webpage. [Accessed September 27 2011];2011 http://www.comfsm.fm/~dleeling/angio/premna_obtusifolia.html.

- Connell J. Bougainville, the future of an island microstate. Journal of Pacific Studies. 2005;28:192–217. [Google Scholar]

- Desrivot J, Waikedre J, Cabalion P, Herrenknecht C, Bories C, Hocquemiller R, Fournet A. Antiparasitic activity of some New Caledonian medicinal plants. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;112:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facey PC, Pascoe KO, Porter RB, Jones AD. Investigation of plants used in Jamaican folk medicine for anti-bacterial activity. J Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 1999;51:1455–60. doi: 10.1211/0022357991777119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes B, editor. Summer Institute of Linguistics International. SIL International; Dallas: 2000. Ethnologue, Languages of the World. [Google Scholar]

- Hoa NK, Phan DV, Thuan ND, Ostenson CG. Screening of the hypoglycemic effect of eight Vietnamese herbal drugs. Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 2009;31:165–9. doi: 10.1358/mf.2009.31.3.1362514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth DK. Technical Paper No. 175. South Pacific Commission; Noumea, New Caledonia: 1977. Medicinal Plants of Papua New Guinea. [Google Scholar]

- Leu T, Soulet S, Loquet D, Meijer L, Raharivelomanana P. Medicinal plants from French Polynesia: evaluation of their free radical scavenging activity. ACGC Chemical Research Communications. 2008;22:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Max Planck Research Group on Comparative Population Linguistics. Language contact and history in southern Bougainville. Papua New Guinea; 2009. (available at: http://www.eva.mpg.de/cpl/bougainville.html) [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier RA, Gil PR, Mittermeier CG. Megadiversity: Earth’s Biologically Wealthiest Nations. Cemex; Monterrey, Mexico: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nash J, Ogan E. The red and the black: Bougainvillean perceptions of other Papua New Guineans. Pacific Studies. 1990;13:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health. National Policy on Traditional Medicine. Waigani: NCD, Papua New Guinea; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Institute. [Accessed April 19th 2011];Autonomous Region of Bougainville. 2010 http://www.nri.org.pg/research_divisions/cross_divisional_projects/15%20ARB.pdf.

- Nour AMM, Khalid SA, Kaiser M, Brun R, Abdalla WE, Schmidt TJ. The antiprotozoal activity of methylated flavonoids from Ageratum conyzoides L. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;129:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DL. Somatic variability and human ecology on Bougainville. Solomon Islands: N.p; N.d. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DL. Papers Peabody Mus Amer Archaeol Ethnol. Harvard Univ; 1949. The Peabody Museum expedition to Bougainville, Solomon Islands, 1938–39; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Rai PP, editor. Traditional Medicine in Papua New Guinea. University of Papua New Guinea Printery, National Capital District, PNG; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Regan AJ. Causes and course of the Bougainville conflict. The Journal of Pacific History. 1998;33:269–285. [Google Scholar]

- Arulmozhi S, Mazumder PM, Ashok P, Narayanan SL. Pharmacological activities of Alstonia scholaris linn. (Apocynaceae) – A review. Pharmacognosy Reviews. 2007;1:163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Summer Institute of Linguistics. [Accessed Sept 27th 2011];PNG Language Resource. 2010 http://www.sil.org/pacific/png/show_lang_entry.asp?id=buo.

- Terrell J. Human biogeography in the Solomon Islands. FIELDIANA Anthropology. 1977;68:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tote MV, Mahire NB, Jain AP, Bose S, Undale VR, Bhosale AV. Effect of Ageratum conyzoides linn on clonidine and haloperidol induced catalepsy in mice. Pharmacology online. 2009;2:186–194. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization), Western Pacific Region. Medicinal Plants in Papua New Guinea. Manila, Philippines: 2009. [Google Scholar]