Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To describe a case of azathioprine-induced warfarin resistance, present a literature review on warfarin–azathioprine interactions, and provide recommendations on appropriate management of this clinically significant interaction.

CASE SUMMARY

A 29-year-old female with Cogan’s syndrome experienced thrombosis of the left internal carotid artery. She was treated with an average weekly warfarin dose of 39 mg (5.5 mg daily) prior to beginning azathioprine therapy. Three weeks following initiation of azathioprine 150 mg daily, the international normalized ratio (INR) decreased from 1.9 (prior to the medication change) to 1.0 without any change in the warfarin dose or other relevant factors. Over several weeks, the patient’s warfarin dose was titrated up to 112 mg weekly (16 mg daily) to achieve an INR of 2.5 (a 188%, or 2.9-fold dose increase). Because of elevated liver enzyme levels, the azathioprine dosage was decreased to 100 mg daily. Within 2 weeks following that decrease, warfarin requirements decreased to 105 mg weekly (15 mg daily).

DISCUSSION

Azathioprine was the probable causative agent of warfarin resistance according to the Naranjo probability scale, and a possible causative agent according to the Drug Interaction Probability Scale. A literature search (PubMed, 1966–December 2007) revealed 8 case reports of this drug interaction and 2 cases involving a similar effect with 6-mercaptopurine, the active metabolite of azathioprine. The exact mechanism of the interaction remains unknown. Previously published case reports point to a rapid onset and offset of the warfarin–azathioprine interaction and a dose-dependent increase of at least 2.5-fold in warfarin dose requirement with the initiation of azathioprine 75–200 mg daily.

CONCLUSIONS

This case report and several others point toward azathioprine as a clinically significant inducer of warfarin resistance. Providers should anticipate the need for higher warfarin doses, warfarin dose adjustment, and close INR monitoring in patients receiving azathioprine or its active metabolite, 6-mercaptopurine.

Keywords: anticoagulation, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, warfarin

Patients requiring azathioprine for immunosuppression may also be treated with the oral vitamin K antagonist warfarin for the prevention or treatment of thromboembolic disorders. Warfarin therapy requires careful monitoring and adjustment to prevent both recurrent thrombosis and bleeding. Drug interactions with warfarin are numerous and well documented.1,2 Specifically, there is a growing number of case reports in the literature documenting azathioprine’s inhibition of the anticoagulant effect of warfarin.3-9 We present a case and literature review and provide recommendations on management of this clinically significant drug interaction.

Case Report

A 29-year-old female with Cogan’s syndrome, a rare immune-mediated systemic disorder that affects primarily the eyes and inner ear and may be accompanied by small- or large-vessel vasculitis,10 was referred to the pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic following thrombosis of the left internal carotid artery. She was treated with subcutaneous enoxaparin 1 mg/kg every 12 hours and warfarin until a therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR; goal 2.5, range 2–3) was achieved and then was continued on warfarin alone. A hypercoagulability workup, including antiphospholipid antibody test, was negative. Other medications at the time of anticoagulation initiation included methylprednisolone, lansoprazole, alprazolam, and cyclophosphamide. Five months later, the patient began taking trazodone and alendronate and tapering the methylprednisolone dose by 2 mg every 2 weeks, all without a change in her INR stability. Throughout this time the patient was maintained on an average weekly warfarin dose of 39 mg (5.5 mg average daily dose).

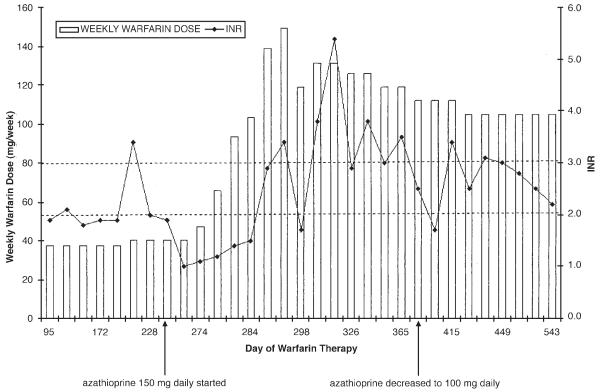

After 8 months of anticoagulation therapy, treatment was switched from cyclophosphamide to azathioprine 150 mg daily. Two months prior to initiation of azathioprine, the weekly warfarin dose was increased slightly to 40.25 mg (5.75 mg daily). Her INR immediately prior to azathioprine therapy was 1.9. Three weeks following initiation of azathioprine, the patient was seen in the anticoagulation clinic and her INR was 1.0, without any change in warfarin dose, diet, medications, or other relevant factors. It is unknown at what point during those 3 weeks that the INR began to decline. On follow-up 4 days later, the INR remained at 1.1, despite a 30% warfarin dosage increase. Impaired warfarin absorption due to concomitant azathioprine use was considered as a possible cause of the sudden increased warfarin dose requirement, as suggested in Micromedex.11 The patient separated her warfarin and azathioprine dosages by at least one hour; however, the INR 5 days later remained at 1.2. Over the next several weeks the warfarin dose was titrated up to 112 mg weekly (16 mg daily) to achieve an INR of 2.5 (a 188%, or 2.9-fold dose increase; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Warfarin dosage requirements and international normalized ratio (INR) values.

Due to elevation of liver enzyme (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase) levels greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal, the azathioprine dosage was decreased to 100 mg daily. Two weeks after that decrease, and without any change in the warfarin dose, the INR increased to 3.4 (liver enzyme levels were within normal limits). The warfarin dosage was adjusted to 105 mg weekly (15 mg/day), and the INR has remained at a therapeutic level (Figure 1). Her liver enzyme levels have remained within normal limits following the azathioprine dosage decrease.

Discussion

Azathioprine is an immunosuppressive oral prodrug of 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) that is indicated as adjunctive treatment for the prevention of rejection in renal hemo-transplantation and for the management of active rheumatoid arthritis.12 Due to its efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis, azathioprine is often used as a steroid-sparing agent for a variety of immune-mediated diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and systemic lupus erythematosus, and to treat the audiovestibular component of Cogan’s syndrome.10 Its mechanism of immunosuppression for these disorders is unknown.12

Warfarin is used extensively for the treatment and prevention of thromboembolism.13 One of the difficulties in warfarin management is its numerous drug interactions. These interactions occur through various mechanisms, including impaired absorption, cytochrome P450 enzyme induction or inhibition, alteration in plasma protein binding, and antagonism with vitamin K.2

We performed a PubMed search (1966–December 2007) using the search terms warfarin, anticoagulant, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and interaction to identify English-language publications documenting an interaction between these medications (Tables 1 and 2). Six case reports involved patients who were on stable doses of warfarin but then required larger warfarin maintenance doses to maintain a therapeutic INR following initiation of azathioprine.3-7 In several patients taking azathioprine and warfarin, an alteration in warfarin dose was required when the azathioprine dosage was altered or the drug was discontinued.3,4,6-9

Table 1.

Warfarin–Azathioprine Interactions

| Reference | Patients | Warfarin Resistance Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addition of Azathioprine to Warfarin |

Warfarin Dose

Prior to Azathioprine (mg/wk) |

Warfarin

Dose on Azathioprine (mg/wk) |

Necessary

Warfarin Dose Change |

Azathioprine

Dose (mg/day) |

|

| Amato (2007)3 | 47-y-old female with autoimmune hepatitis, APAS, renal infarct |

NR | 165 | unable to calculate | 200 |

| 44-y-old male with lupus nephritis, APAS, DVT |

75 | 190 | 2.5-fold (153%) | 200 | |

| Ng (2006)4,a | 67-y-old female with SLE, recurrent DVT | 24 | 60–75 | 2.8-fold (181%) | 150 |

| Walker (2002)5,b | 41-y-old female with SLE, APAS, PE | 35 | 84 | 2.4-fold (140%) | 150 |

| Havrda (2001)6,c | 32-y-old female with ulcerative colitis, recurrent DVT |

35 | 90 | 2.5-fold (157%) | 75 |

| Rotenberg (2000)7 | 50-y-old female with unclassified auto- immune disease, recurrent PE |

40 | 100 | 2.5-fold (150%) | 100 |

| Azathioprine Dose Adjustment |

Warfarin

Dose on Azathioprine (mg/wk) |

Warfarin

Dose After Azathioprine Dosage Adjustment (mg/wk) |

Necessary

Warfarin Dose Change |

Azathioprine

Initial, Adjusted Dose (mg/day) |

|

| Rivier (1993)8 | 30-y-old female with SLE, APAS, recurrent DVT/PE |

140 | 105 | 1.3-fold (25%) | 150, 100 |

| Singleton (1992)9 | 52-y-old female with APAS, multiple cerebral infarcts |

98–119 | 35 | 3.1-fold (210%) | 200, 75 |

APAS = antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; DVT = deep-vein thrombosis; NR = not reported; PE = pulmonary embolism; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

When azathioprine dose was increased to 200 mg daily, weekly warfarin requirement increased to 130 mg, an additional 1.9-fold (93%) increase.

Azathioprine was initiated at 25 mg daily and gradually titrated to 150 mg daily; the interaction became apparent with azathioprine 100 mg daily.

Table 2.

Warfarin–6-Mercaptopurine Interactions

| Reference | Patients | Warfarin Dose Prior to 6-MP (mg/wk) |

Warfarin Dose on 6- MP (mg/wk) |

Necessary Warfarin Dose Change |

6-MP Dose (mg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martin (2003)14 | 81-y-old male with acute promyelocytic leukemia, history of DVT/PE | 38.5 | 77 | 2-fold (100%) | 100 |

| Spiers (1974)15 | 62-y-old male with chronic granulocytic leukemia, recurrent DVT | 33.6 | 70 | 2-fold (108%) | 100 |

DVT = deep-vein thrombosis; 6-MP = 6-mercaptopurine; PE = pulmonary embolism.

This interaction is also evident with 6-MP. Two cases reported increased warfarin requirements following initiation of 6-MP and a return to previous dosing requirements when 6-MP was discontinued.14,15 Azathioprine and 6-MP also affect other oral anticoagulants. We identified 2 case reports involving increased phenprocoumon requirements with the addition of azathioprine16 and 1 involving acenocoumarol and 6-MP.17

In our patient, the average warfarin dose requirement tripled, from 37.5 mg weekly during her azathioprine-free period to 112 mg weekly after azathioprine was initiated. The magnitude of this increased warfarin requirement (2.5–3 times higher) is consistent with other reports in the literature.3-7 Throughout this time the patient maintained consistency with vitamin K–containing foods in her diet, specifically by consuming a fixed amount of spinach every day. She also refrained from alcoholic beverages and took all warfarin doses as instructed. Additionally, her disease remained stable, allowing her to steadily taper methylprednisolone.

Wells et al.18 published a comprehensive review of warfarin interactions and ranked them using an interaction assessment tool evaluating causation criteria, subject outcome, and proposed mechanisms. The authors ranked the azathioprine–warfarin interaction as Level 3 evidence (possible). Since publication of the above case reports, those authors upgraded the probability for azathioprine inhibition of anticoagulant effect to Level 2 evidence (probable) in their most recent update of this review.1 When applying other available assessment tools to our case, azathioprine was the probable causative agent according to the Naranjo probability scale,19 and a possible causative agent according to the Drug Interaction Probability Scale (DIPS).20 The reason for difference in the probability ranking between these 2 assessment tools involves the questions used to evaluate the interaction. The Naranjo algorithm is a well-established method designed to assess the causality of adverse drug reactions from a single drug, whereas DIPS has recently been developed as a modified version of the Naranjo algorithm to assess causality of a potential drug–drug interaction. In contrast to the Naranjo algorithm, whose questions are more general, the DIPS relies heavily on mechanism and time course of the interaction, known interactive properties of both medications, drug concentrations, and results of dechallenge and rechallenge. Many of these questions are targeted toward hepatic enzyme inhibitors and inducers, and azathioprine has not been proven to be either of these. Since the mechanism of the warfarin–azathioprine interaction is unknown and rechallenge was not applicable to our case, we were required to answer these questions with unknown or not applicable, resulting in the lower score of possible.

The mechanism by which azathioprine or 6-MP inhibits warfarin’s effect is unknown. Prompted by the first published case report of a warfarin and 6-MP interaction, Martini and Jähnchen21 conducted a pharmacokinetic study in rats evaluating the mechanism by which 6-MP inhibits the anticoagulant effect of warfarin. To evaluate impaired warfarin absorption as a possible mechanism, the rats were given intravenous warfarin, and the interaction was still observed. Also, induction of warfarin metabolism by 6-MP was evaluated as a possible mechanism; however, the warfarin elimination half-life was significantly longer in the rats given 6-MP. When the rate of synthesis and degradation of each of the vitamin K–dependent clotting factors affected by warfarin was tested, there was an increase in prothrombin complex activity in the rats given warfarin and 6-MP.

Rotenberg et al.7 also sought to elucidate the mechanism of this interaction by measuring warfarin plasma concentrations. The patient had lower warfarin plasma concentrations at higher warfarin doses in the presence of azathioprine. Similarly, when azathioprine was discontinued and warfarin doses were reduced, warfarin plasma concentrations increased. These data support the presence of a pharmacokinetic interaction; however, increased prothrombin and Factor X activity may also play a role. Another potential mechanism that has yet to be established is the possibility of genetic polymorphism.3 To date, the mechanism by which this interaction occurs remains unknown.

The onset of the warfarin–azathioprine interaction is difficult to determine, but one report provided information on the time course.7 Fifteen days prior to initiation of azathioprine, the patient had an INR of 3.4, and 8 days after azathioprine was started, the INR had decreased to 1.1. Conversely, 10 days after discontinuation of azathioprine, the patient’s INR increased from 1.95 to 8.3. It is unknown when during this 8- to 10-day period these changes began to occur. Based on this, close monitoring of the INR (~3 days after initiation or discontinuation of azathioprine) is recommended, and providers should anticipate the need for warfarin dose adjustment in patients started on either azathioprine or 6-MP.

In the reports cited here, most patients required at least a 2.5-fold warfarin dose increase (range 2.4- to 5.4-fold) with the initiation of azathioprine 75–200 mg daily.3,4,6,7 Additionally, the warfarin–azathioprine interaction appears to be dose-dependent. In all cases where there was an azathioprine dose adjustment, a warfarin dose adjustment was also required.4,6,8,9 The minimum azathioprine dosing threshold for the interaction appears to be 75 mg daily.6 In a similar case, the patient was started on azathioprine 25 mg daily and the dose was subsequently titrated up to 150 mg daily.5 The authors noted that the interaction did not appear until the azathioprine dose reached 100 mg daily.

One serious complication of the warfarin–azathioprine interaction is the risk for a supratherapeutic INR and subsequent bleeding events when the azathioprine dosage is reduced or the drug is discontinued. Several reports described significant elevations of the prothrombin time/INR and several clinically significant bleeding events when azathioprine or 6-MP was discontinued and the oral anticoagulant dosage was unchanged.4,5,9,17,22 In these cases, there were other potential risk factors for bleeding in addition to the drug interaction, and specific details of these cases were not discussed. Equally important is the potential risk for subtherapeutic INR and venous thromboembolism when azathioprine is added to warfarin therapy without close INR monitoring and warfarin dose adjustment. To date, no cases of thromboembolic events occurring as the result of the drug interaction have been published.

There are 2 potentially confounding factors in our case report: the tapering of methylprednisolone and the addition of trazodone to the medication regimen. There are conflicting reports of corticosteroids’ effects on the INR response. The prescribing information for warfarin reports both increased and decreased INR responses with adrenocortical steroids.2 An overview on warfarin drug and food interactions reported it to be highly improbable for methylprednisolone to potentiate the effect of warfarin.1 Conversely, other reports described a significant increase in INR following corticosteroid therapy.23 In the 8 warfarin–azathioprine interaction case reports cited here, at least 6 involved concomitant oral corticosteroids,4-9 yet the interaction between warfarin and azathioprine was still observed. In our case, the patient began tapering the methylprednisolone dose 4 months prior to initiation of azathioprine and continued the same tapering schedule throughout the use of azathioprine. This fact, combined with the lack of substantive data in favor of a corticosteroid effect on the INR, suggests that methylprednisolone therapy was not a confounding factor in this drug interaction.

Trazodone was also initiated in our patient; the prescribing information for warfarin does report decreased INR response with trazodone.2 Holbrook et al.1 reported the interaction to be highly probable, and the interaction is supported by several case reports.24,25 Our patient’s INR was 1.9 when she started taking trazodone (4 mo prior to starting azathioprine) and, 3 weeks later, was again 1.9. Therefore, trazodone does not appear to be the cause of warfarin resistance in this case.

Regarding our patient’s transient elevated liver enzyme levels, we do not believe that this is reflective of synthetic liver dysfunction due to lack of correlation with elevated INR. Had liver dysfunction been a cause of the elevated INR, one would expect liver enzymes to be elevated as well. However, 2 weeks following the azathioprine dosage decrease, the patient’s liver enzyme levels had returned to within normal limits and the INR was 3.4. The elevation in liver enzyme levels was asymptomatic, mild, and did not affect the patient’s INR or warfarin requirements.

Conclusions

We hope that this report will bring more attention to the clinical significance of this drug interaction and assist in prevention of patients being mistakenly labeled as having idiopathic warfarin resistance. Based on the case reports cited here, we make the following recommendations.

If a patient is already taking azathioprine or 6-MP and warfarin is initiated, anticipate that some patients may likely require increased warfarin maintenance doses.

If azathioprine (minimum daily dose 75 mg) is added to existing warfarin therapy, expect the patient to require at least a 2.5-fold warfarin dosage increase to maintain a therapeutic INR.

Monitor the INR within 3 days of initiation or withdrawal of azathioprine or 6-MP and continue to monitor closely throughout the titration period.

Inform the patient and his or her other healthcare providers that azathioprine or 6-MP discontinuation or dosage changes will likely affect warfarin dosage requirements and that clear communication regarding potential changes is essential to prevent serious adverse events.

Emphasize to the patient that adherence to both warfarin and azathioprine or 6-MP is important and that nonadherence to either medication can result in a significant change in INR and an increase in the risk of adverse events.

Contributor Information

Sara R Vazquez, University Thrombosis Service, Department of Pharmacy Services, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT.

Matthew T Rondina, Internal Medicine; Co-Director, Anticoagulation Services, University Thrombosis Service, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Utah.

Robert C Pendleton, Clinical Medicine; Co-Director, Hospitalist Program; Director, University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, University Thrombosis Service, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Utah.

References

- 1.Holbrook AM, Pereira JA, Labiris R, et al. Systematic overview of warfarin and its drug and food interactions. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1095–106. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Package insert. Coumadin (warfarin sodium) Bristol-Myers Squibb Co.; Princeton, NJ: Aug, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amato M, Mantha S, Corneau R, Sherry P, Tsapatsaris N. Azathioprine induced warfarin resistance: case reports and potential interaction mechanism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2008;25:111. Epub 7 Nov 2007. DOI 10.1007/s11239-007-0119-4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng HJ, Crowther MA. Azathioprine and inhibition of the anticoagulant effect of warfarin: evidence from a case report and a literature review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:75–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.03.001. DOI 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker J, Mendelson H, McClure A, Smith MD. Warfarin and azathioprine: clinically significant drug interaction (letter) J Rheumatol. 2002;29:398–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havrda DE, Rathbun S, Scheid D. A case report of warfarin resistance due to azathioprine and review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:355–7. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.3.355.34208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rotenberg M, Levy Y, Shoenfeld Y, Almog S, Ezra D. Effect of azathioprine on the anticoagulant activity of warfarin (letter) Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:120–2. doi: 10.1345/aph.19148. DOI 10.1345/aph.19088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivier G, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR. Warfarin and azathioprine: a drug interaction does exist (letter) Am J Med. 1993;95:342. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90292-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singleton JD, Conyers L. Warfarin and azathioprine: an important drug interaction (letter) Am J Med. 1992;92:217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90116-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazlumzadeh M, Matteson EL. Cogan’s syndrome: an audiovestibular, ocular, and systemic autoimmune disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33:855–74. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.07.015. DOI 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klasco RK, editor. DRUG-REAX System. Thomson Micromedex; Greenwood Village, CO: Warfarin and azathioprine. Interaction detail. expired 2007 Dec 31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Package insert. Imuran (azathioprine) Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Newport, KY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansell J, Hirsh J, Poller L, Bussey H, Jacobsen A, Hylek E. The pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists. Chest. 2004;126(suppl):S204–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.204S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin LA, Mehta SD. Diminished anticoagulant effects of warfarin with concomitant mercaptopurine therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:260–4. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.2.260.32080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiers AS, Mibashan RS. Increased warfarin requirement during mercaptopurine therapy: a new drug interaction (letter) Lancet. 1974;27:221–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeppesen U, Rasmussen JM, Brosen K. Clinically important interaction between azathioprine (Imurel) and phenprocoumon (Marcoumar) (letter) Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52:503–4. doi: 10.1007/s002280050326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez MA, Regadera A, Aznar J. Acenocoumarol and 6-mercaptopurine: an important drug interaction (letter) Haematologica. 1999;84:664–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells PS, Holbrook AM, Crowther NR, Hirsh J. Interactions of warfarin with drugs and food. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:676–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-9-199411010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horn JR, Hansten PD, Chan L-N. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:674–80. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H423. Epub 27 Mar 2007. DOI 10.1345/aph.1H423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martini A, Jähnchen E. Studies in rats on the mechanism by which 6-mercaptopurine inhibits the anticoagulant effect of warfarin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;201:547–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castellino G, Cuadrado MJ, Godfrey T, Khamashta MA, Hughes GRV. Characteristics of patients with antiphospholipid syndrome with major bleeding after oral anticoagulant treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:527–30. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.5.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazlewood KA, Fugate SE, Harrison DL. Effect of oral corticosteroids on chronic warfarin therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:2101–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H418. Epub 21 Nov 2006. DOI 10.1345/aph.1H418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy JL, Sirois A. Reduction of prothrombin and partial thromboplastin time with trazodone. CMAJ. 1986;135:1372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Small NL, Giamonna KA. Interaction between warfarin and trazodone. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:734–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.19336. DOI 10.1345/aph.19336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]