Abstract

Toward the goal of reproducible live neuronal networks, we investigated the influence of substrate patterns on neuron compliance and network activity. We optimized process parameters of micro-contact printing for reproducible geometric patterns of 10 µm wide lines of polylysine with 4, 6, or 8 connections at a constant square array of nodes overlying the recording electrodes of a multielectrode array (MEA). We hypothesized that an increase in node connections would give the network more inputs resulting in higher neuronal outputs as network spike rates. We also chronically stimulated these networks during development and added astroglia to enhance network activity. Our results show that despite frequent localization of neuron somata over the electrodes, the number of spontaneously active electrodes was reduced 3-fold compared to random networks, independent of pattern complexity. Of the electrodes active, the overall spike rate was independent of pattern complexity, consistent with homeostasis of activity. Lower mean burst rates were seen with higher levels of pattern complexity; however, burst durations increased 1.6-fold with pattern complexity (n=6027 bursts, p<0.001). Inter-burst interval and percentage of active electrodes displaying bursts also increased with pattern complexity. The extra-burst (non-burst or isolated) spike rate increased 4-fold with pattern complexity, but this relationship was reversed with either chronic stimulation or astroglia addition. These studies suggest for the first time that patterns which limit the distribution of branches and inputs are deleterious to activity in a hippocampal network, but that higher levels of pattern complexity promote non-burst activity and favor longer lasting, but fewer bursts.

Keywords: MEA, electrode array, microstamp, patterned substrate, neural network

1. Introduction

The study of coding in neural networks depends on the availability of reproducible and reliable live neuronal networks. Toward the goal of creating these networks, we and others have confined the growth of neurons to reproducible geometric patterns (Branch et al., 1998; Chang et al., 2003; Singhvi et al., 1994; St.John et al., 1997; Vogt et al., 2005). This reductionist approach is predicated on simplifying the complexity of the intact brain and even the hippocampal slice. The problem is exemplified by the enormous success of studies of synaptic function and plasticity both in the slice and in cultured neurons, with relatively scant information on how these neurons compute in the network in which they are embedded. Since each rat hippocampal neuron averages 10,000 connections (Braitenberg & Schuz, 2004), we wanted to determine how important this number was to overall viability and function. Our reductionist approach rigorously constrained connections between separated neurons to 4, 6 or 8 other neurons, compared to the random or uncontrolled connections in a typical 2-dimensional culture.

Our long-term goal has been to create patterned substrates at 1) cellular resolution (≤10 µm) with 2) viability sufficient to proceed through development of synapses with robust network activity (3 weeks), and 3) localize neuron somata over substrate electrodes to be able to monitor the network. The first goal to manufacture patterned substrates at cellular resolution was achieved in previous research by either ultraviolet photoresist chemistries (Kleinfeld et al., 1988; Corey et al., 1996), laser ablation of uniform substrates (Dulcey et al., 1991; Corey et al., 1991; Ravenscroft et al., 1998) or PDMS rubber stamps (Singhvi et al., 1994; Branch et al., 1998; Wheeler et al., 1999). PDMS stamps that we and others have employed to create geometric patterns of neuron substrate adhesion material are easily mass produced and have the ability to transfer adhesion promoters to any surface, including electrodes.

Our second goal of viability beyond one or two weeks was achieved with the development of covalent bonding of adhesion promoters to glassy substrates by silane chemistries. An essential attachment of functional amino groups such as poly-lysine or trimethoxy-silyl-propyl-diethylene-triamine (DETA) selectively promotes neuron viability on patterned substrates (Kleinfeld al., 1988; Hickman et al. 1994). Additionally, background materials of neuron-repulsive silanes with terminal fluorines (Ravenscroft et al., 1998) or poly-ethylene glycol (Branch et al., 2001) improve long-term compliance at cellular resolution of <20 µm wide patterns. These techniques permit high compliance patterned growth of neurons beyond the 3 week minimum for which network activity is robust in random cultures over electrode arrays. Despite these advances, robust network activity has not been reported at pattern resolutions below 20 µm.

The third goal of robust activity of patterned networks requires positioning the higher current-source density of the neuron somata in close proximity to the electrode. We achieved this localization by creating cell-sized areas of larger adhesion (20–30 µm diameter). As a result, the somata migrated to these areas from narrower paths occupied by axons and dendrites (Corey et al., 1991). Our unpublished observations of little or no activity for patterned networks prompted us to determine whether silane adhesion or neuron proximity to the electrode was at fault. With silanized substrates and 40 µm wide patterns, activity was observed on only 25% of the electrodes with somata on or within 20 µm (Nam et al., 2004). Better electrode coupling of the patterned amine to the electrode with an epoxy-silane (Nam et al., 2006) enabled high levels of activity to be recorded on 40 µm wide patterns, but again failed to enable sparser networks on 10 µm wide patterns (unpublished observations).

One possibility for poor long-term performance of networks at cellular resolution evaluated here was the frequent observation of uneven densities of pattern material. Commonly, the stamp is immersed in a neuron-adhesive ink such as a solution of the common polypeptide, poly-D-lysine, followed by removal of excess ink without drying. Potential processing problems that we addressed were: 1) the uniformity of inking, both as clustering of ink pools and amount of ink carried by the stamp, 2) the uniformity and concentration of ink transfer after stamping, 3) retention of the ink on the substrate and 4) ink density that best supported neuron viability and growth. By optimizing these parameters, we reliably created geometric patterns with square nodes connected by 4, 6 or 8 lines of 10 µm width for correlating pattern complexity with network spiking characteristics relative to the more common random cultures without stamped patterns.

A further goal of this line of investigation was to plate neurons at a density low enough to enable the association of neuron function with microscopically visible pathways. At densities below 500 cells/mm2, currents from most neuronal somata would not be close enough to our electrodes (30 µm electrodes at 200 µm spacing) to detect activity above noise. However, we expected to mitigate this problem by virtue of the tendency of somata to migrate to the nodes of square patterns (Corey et al., 1991), where the substrate area was larger than available on a 5–10 µm wide line. This approach also requires alignment of pattern nodes to substrate electrodes.

Because low density cultures were expected to produce low levels of spiking activity, we used three approaches that increase spontaneous and/or evoked activity in random cultures with densities of 500 cells/mm2. First, we used NbActiv4 culture medium containing creatine, estrogen and cholesterol to enhance synaptogenesis (Brewer et al., 2008). In random, non-patterned cultures, these ingredients increase synapse density 2-fold and result in 4-fold higher spike rates. Second, cultures were stimulated daily during development as we had shown previously that chronic stimulation improved activity (Brewer et al., 2009; Ide et al., 2010). Stimulation of 1–3 hr/day for 2 weeks increases spontaneous spike rates 2-fold after 3 weeks in culture and recruits up to 50% more active electrodes as well as doubling the spike frequency within bursts. Evoked responses also increase 50%/stimulus. Third, we added astroglia which we had shown was particularly beneficial to the non-patterned culture (Boehler et al., 2007). Separate cultures of astroglia, harvested and applied in numbers equal to the neurons not only increased neuron survival in non-patterned cultures, but doubled spontaneous spike rates, with even higher instantaneous rates evoked in response to glutamate. Therefore, we evaluated the ability of each of these enhancements of unpatterned networks to increase the activity of patterned networks.

Our results show important process improvements for increased reliability and functionality of geometric patterns from micro-stamping. These methods enabled neurons to maintain viability for the weeks needed to develop synapses and spiking activity. The work presented here is to our knowledge the first to systematically evaluate the effect of the number of connections within a patterned substrate on network activity. Characterization of the nature of the activity with pattern complexity indicated longer burst durations but no change in average channel spike rate. Without stimulation, non-burst spike rates increased with pattern complexity.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Mold and stamp fabrication

Silicon wafers coated with a 10 µm layer of SU-8 2010 photoresist (Microchem, Inc., Newton, MA) were micro-fabricated into molds to match the structural patterns of arrays (Chang et al., 2003). Multiple replicates of each pattern were created on one mold. Square geometric patterns of 10 µm depth were created on 200 µm centers as 20 µm diameter nodes connected with 10 µm lines making either 4, 6 or 8 connections. Wafers were cleaned with an oxygen plasma for 20 sec at 55 W, followed by baking for 1 min at 110 °C. A spin-coated 10 µm layer of SU-8 2010 was deposited by rotation at 500 rpm for 5 sec followed by 3500 rpm for 40 sec.

The SU-8 was baked on a 65 °C hotplate for 1 min followed by 3 min at 95 °C and 1 min at 65 °C. The mold was exposed to UV light for 26 sec at 5.8 mW/cm2 and baked as before. The pattern was developed in SU-8 developer for 2 min with mild agitation every 10–15 sec. The pattern was cleared with a rinse of fresh SU-8 developer followed by a thorough rinse with 2-propanol and blown dry with nitrogen. To promote release of the stamps, the mold was silanized with 100 µL tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl-1-trichlorsilane (United Chemical Technologies, Bristol, PA) under vacuum. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184, Dow Corning, Midland, MI) stamps were created by mixing the elastomer with curing agent at a 10:1 ratio, degassed and poured onto the mold, bounded by 1.2 mm diameter glass tubes to set the thickness, then cured overnight at an optimal temperature of 37 °C. In previous protocols elastomer mix was cured overnight at 60°C which caused shrinkage of patterns. Cured PDMS slabs were removed from the mold and cut into 1 × 1 cm squares. A blank 12 × 12 mm coverslip (Fisher) was cleaned for 3 min with an O2 plasma. The patterned stamp was attached to the cleaned slip as a backing substrate within 10 min of curing. Unused stamps were stored at room temperature.

2.2. Stamp surface modification and alignment

Fresh cut stamps were used for each experiment. All drying steps began with a stream of filtered nitrogen. All water was deionized to 18 Mohm. The stamp was first soaked stamp side up in 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, Fisher) solution for 20 min (Chang et al., 2003) to bind hydrophobic sites on the PDMS and create a thin anionic film to electrostatically bind the cationic polylysine. Stamps were blown dry, rinsed in water, then blown dry again for 3 sec at 1 psi. This order was important to produce a uniform coating of the cationic poly-D-lysine (PDL) on the SDS residue (see results 3.1).

Poly-L-lysine conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (PLL-FITC, Sigma # P3069) was used as a fluorescent tag to observe the transfer of PDL (Sigma # P6407). To the 5 mg of sterile PDL was added 2.5 mg PLL-FITC. Water was added to make 100 µg/ml PDL, 50 µg/ml PLL and mixed vigorously by hand at room temperature. Single use aliquots were frozen at −20 °C. Solutions to be used as ink for the stamps were thawed for at least 60 min in a 37 °C water bath with mixing by hand shaking every 15 min (see results). Stamps attached to slips were submerged for 1 hr at about 22 °C in the polylysine ink solution. Excess ink was removed by suction taking care to leave the surface of the stamp wet with at least 50 µL ink. The stamp was next mounted on the mechanical aligner face up with the stamp backing substrate held in place by a vacuum chuck. Each stamp was blown dry through a 6 inch Pasteur pipet at 6 psi on the microscope aligner until the stamp was seen as visibly dry (no more than 3 sec) through a 5× objective and a Spot 3.2.0 camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Next the MEA array was mounted on the vacuum chuck face down. The position of the MEA was manipulated to be coplanar and aligned with the stamp so that the pattern nodes were coincident with the electrodes of the electrodes of the array. The stamp was then raised to the MEA substrate surface until visible contact was verified through the aligner microscope. Stamps contacted arrays for 3 min before being removed. Immediately after stamping, MEA substrates were dried to open air for 1 min then rinsed in water to remove any excess ink. Arrays were imaged under fluorescent microscopy with a FITC dicroic through an Olympus 10×/0.30 objective for evidence of polylysine transfer. Images were recorded at 12 bit depth with a RetigaExi CCD camera (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada). Arrays were sterilized with 70% ethanol then rinsed once in sterile water and aspirated before culturing.

2.3. Electrode array substrate silanization and preparation

Glass pipettes were used for all organic chemicals to avoid transfer of plasticizers from plastic pipette tips which can lead to neuron toxicity in cultures. Microelectrode arrays on glass carriers (MEA60, Multichannel Systems, Reutlingen, Germany) consisted of 59 TiN3 electrodes and one ground electrode with diameters of 30 µm and spacing of 200 µm. Array substrates were rinsed for 5 s in each of the following: acetone, isopropanol and 18mohm deionized water. Arrays were blown dry with filtered nitrogen then treated for 3 min with an O2 plasma at 25 mA (3.9 cm electrode spacing, Electron Microscopy Sciences). Within 10 min of receiving plasma treatment, arrays were silanized with the crosslinking agent 1% 3-glycidoxypropyl-trimethoxysilane solution (3-GPS, (Nam et al., 2004); Gelest, Arlington, VA) mixed in toluene and allowed to react for 20 min. The 3-GPS was stored at room temperature under a layer of nitrogen gas to exclude water. After silane treatment, arrays were rinsed 3 times in fresh toluene, blown dry with nitrogen and placed in an oven at 110°C for one hour. Arrays were allowed to cool to room temperature before immediate application of stamped patterns. Patterns of stamps were aligned to array electrodes using a home-made micrometer resolution mechanical aligner for polylysine stamp pattern transfer.

2.4. Hippocampal neuron cultures on electrode arrays

E18 rat hippocampal neurons were plated on patterned MEAs in NbActiv4® medium (Brewer et al., 2008) (BrainBits, Springfield, IL) at 50 cells/mm2. For random, unpatterned networks, plating was increased to 500 cells/mm2 on uniform polylysine. This disparity was established to produce approximately the same number of cells per area of substrate, assuming all the cells migrated onto the pattern (Corey et al., 1991) (see Fig. 5). The pattern areas varied with connections: 4-connect (0.256 mm2), 6-connect (0.437 mm2), and 8-connect (0.618 mm2) over an array area of 1.96 mm2. Theoretically, if all plated neurons landed exclusively on the polylysine patterned substrate covering the 60 array electrodes, cell density would be 50 cells/mm2 × 1.96 mm2 / 0.256 mm2 for the 4-connect pattern = 383 cells/mm2, or 224 cells/mm2 for the 6-connect, or 159 cells/mm2 for the 8-connect pattern. Patterned cultures were not plated at higher densities because densities higher than 50 cells/mm2 resulted in clustering of neurons and poor pattern compliance. Cultures were incubated in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2, 9% O2 at 37° C. Every 4–5 days, half of the culture medium was removed and replaced with the same volume of fresh medium. Medium changes were avoided the day of and the day prior to recording. Neuron somata were counted through a 20× phase contrast objective lens as phase-bright objects 10–20 µm diameter objects with visible neurites.

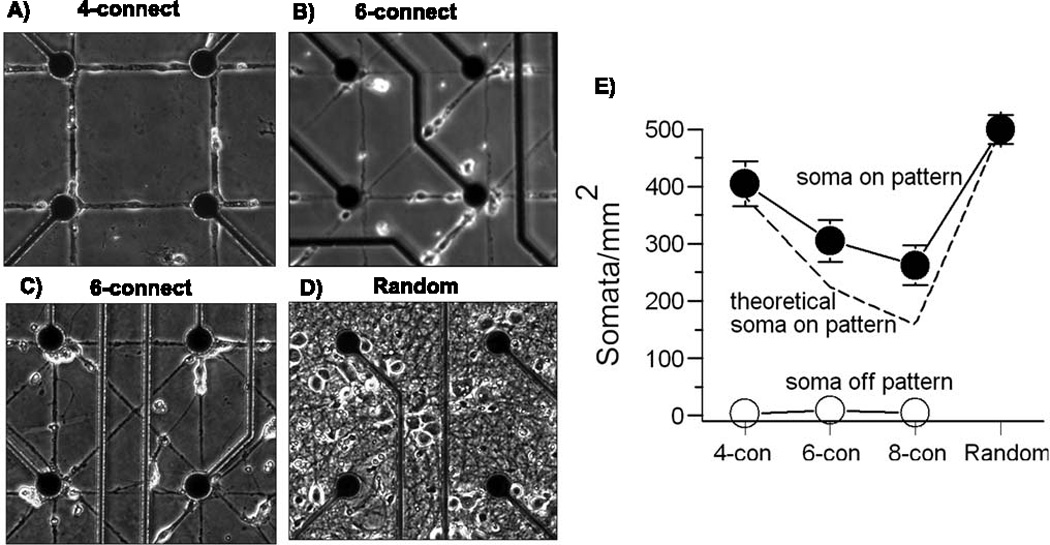

Fig. 5.

Substrate patterns of increasing complexity grow neurons equally well to 22 days in vitro. Acceptable neuron growth and compliance to patterns. A) 4-connect, B) 6-connect, C) 8-connect, D) Random, E) Average soma per pattern area follow trend of theoretical soma on pattern based on original plating density of 50 cells/mm2 on patterned arrays and 500 cells/mm2 on random arrays over the area of random MEA plating substrate available. No patterned MEA had more than 3% total soma grow off of the pattern (n = 2 arrays for each condition with each array analyzed in 10 fields of 0.4 mm2 area).

2.5. Chronic stimulation during development

Chronic stimulation was administered by a stimulus generator (MCS STG2004) to arrays inside an incubator for 3h/d, starting at day 7 up to and including the day of recording at 3 weeks. Stimulation trains consisted of two pairs of 30 µA pulses (biphasic, 100 µs/phase, positive first) with a 50 ms interval between each pulse in the pair and a 5 s interval between pairs (Ide et al., 2010). An automatic stimulation program was created using Microsoft Visual C++ 2008 that applied the stimulation train to all 59 electrodes on the MEA in a sequence consisting of two phases: 1) single electrodes were stimulated in a pseudorandom sequence such that consecutive electrodes were not adjacent to each other, and 2) diagonally adjacent pairs of electrodes were simultaneously stimulated in a pseudorandom sequence such that consecutive pairs of electrodes were not adjacent to each other. This two-part protocol was repeated for 3h/day (the same for every array, every time). Electrodes were not pre-selected for activity. When switching between stimulated electrodes, a 1 second pause was inserted for a trigger signal to notify the program to switch electrodes. The net result was that each electrode was stimulated 104 times by biphasic pulses.

2.6. Addition of astroglia

We previously reported increased activity of random cultures in Neurobasal/B27 at day 21 following addition of astroglia at 8 day in culture (Boehler et al., 2007). Briefly, astroglia were cultured from E18 rat hippocampi at 200 cells/mm2 in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen), 2 mM glutamine, 10% horse serum for 2 weeks with 50% medium changes every 3–4 days. One day before harvest, a 50% medium volume transition was made to NbActiv4 (changed from the original Neurobasal/B27). Astroglia were harvested using 0.25% trypsin. Arrays to receive astroglia at 8 days were first stamped or flooded with polylysine as above. Before addition of neurons, arrays were treated with 500 µg/ml astroglial protein (AGP; NH2-KHIFSDDSSE-acid, Piproteomics) (Kam et al., 2002) to enhance the attachment of astroglia to non-stamped areas (areas without polylysine/PLL-FITC). First, arrays were flooded for 10 min with 200 mM ethylenediamine (Acros) in imidazole, pH 6 (Sigma). Arrays were rinsed with water three times then flooded for 20 min with 500 µg/ml AGP in cross-linker 1-ethyl-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide, 10 mg/mL (Thermo Scientific), 0.1 M MES, pH 4.7 (Fisher). After rinsing, neurons were plated and cultured as usual. The AGP coating did not affect neuron viability. Harvested astroglia were added to neuron cultures at 8 days at the same density as the original neurons.

2.7 Data Acquisition and signal processing

Spontaneous activity on MEAs was recorded using with an MCS 1100X amplifier at 40kHz sampling rate and a hardware filter of 8-3000 Hz at 37° C. During recording, the cultures were exposed to continuous flow of a sterile filtered, hydrated gas mixture custom made to match the incubator gases of 5% CO2, 9% O2, balance N2 (AGA, Springfield, IL). A Zebra Strip (Fujipoly America, Carteret, NJ) was used on array contact pads to lessen amplifier contact noise. A 13 µm thick Teflon membrane (ALA Scientific, Westbury, NY) covered array cultures to reduce evaporation and contamination during stimulation. After 21–26 days in culture, raw electrode signals were recorded for 3 min.

Offline signal processing was performed to detect and classify spikes using a custom modification of the Spycode v2.0 software (Bologna et al., 2010). Signals were digitally filtered through a 400-tap Hamming high pass filter at 300 Hz cutoff. Background noise levels were computed as the minimum standard deviation of 1-second windows over the entire recording. Spikes were detected as peak-to-peak deviations of 11× the noise (Ide et al., 2010) in 2 ms sliding windows with a post spike dead time of 1 ms (Maccione et al., 2009). To automatically reject shorted or open electrodes, active channels were selected with a minimum background noise of 1 µV and a maximum of 10 µV, respectively. Detected spikes were subjected to an artifact removal stage before being accepted as action potentials. Based on histograms of all electrodes, real spikes were identified as having peak-to-peak heights of 30–400 µV and widths at half height of 200–900 µs (Leondopulos & Brewer, in preparation). Electrodes were considered active if the corresponding spike rate was between 0.01 Hz and 100 Hz. Bursts of activity were selected as having a minimum of 5 spikes per burst with a maximum inter-spike interval of 100 ms (Bologna et al., 2010).

Spike correlograms were computed between separate channels as histograms of spike pairs (Chiappalone et al., 2006) occurring with time lags binned at 5 ms and centered at 0 ms over a window of +/− 20 ms with autocorrelations on each electrode excluded.

2.8 Statistics

All data are displayed as mean ± SEM. Single pairs of conditions (Fig. 2) were evaluated by student’s t-test. Effects of the number of connections, stimulation, or added astroglia were determined by ANOVA from Spycode using the statistical tool of Matlab. A probability less than 0.05 was considered significant.

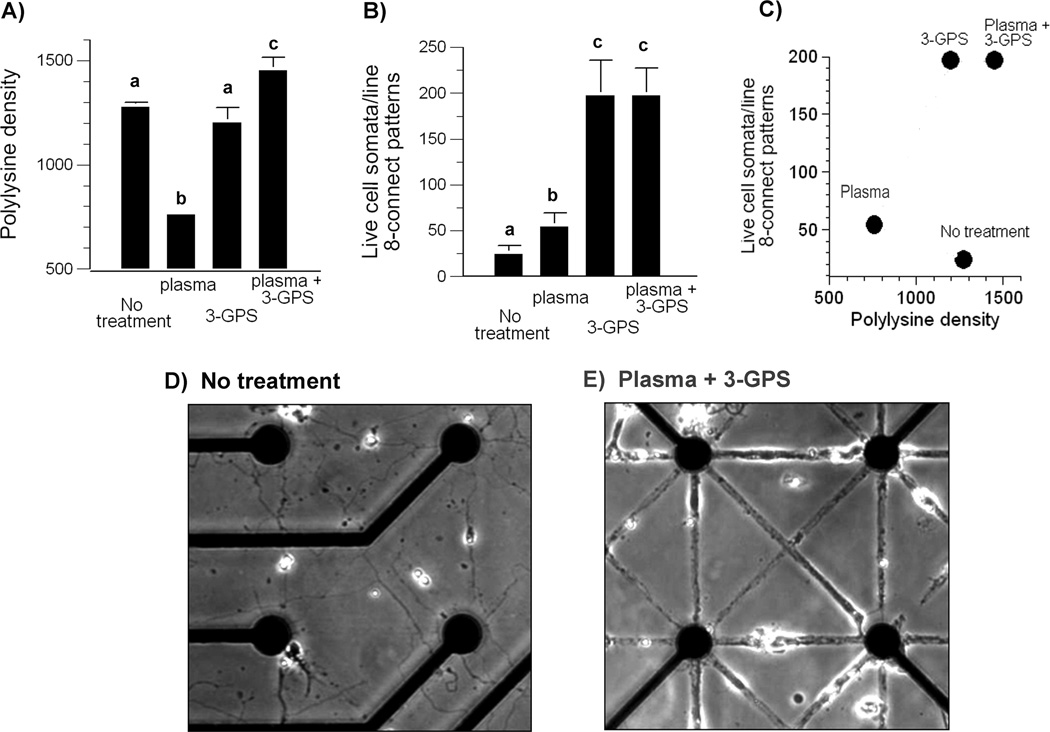

Fig. 2.

Treatment of MEA with oxygen plasma treatment and 3-GPS silane improves patterned polylysine transfer and cell survival. A) Fluorescent intensities of patterned lines of polylysine/PLL-FITC transfer by stamping onto electrode arrays prepared as indicated. Significance between bars with different letters p<0.01; bars with same letters are not significantly different (n = 4 arrays for each condition). B) Cell somata survival on patterned substrates after 22 days (n = 4 arrays for each condition, 18 pattern segments for each array). C) Cell somata survival on patterned substrates in relation to intensity of polylysine/PLL-FITC transfer. Note that survival is not a simple function of polylysine density (data combined from A and B). D) Untreated MEA substrate with poor cell survival at 22 days in vitro. E) Oxygen plasma and 3-GPS silane treated MEA substrate with good cell survival at 22 days in vitro. Phase bright objects are cell somata. Electrode spacing is 200 µm.

3. Results

3.1. Reproducible quality patterns and network growth at 3 weeks

3.1.a. Substrate preparation

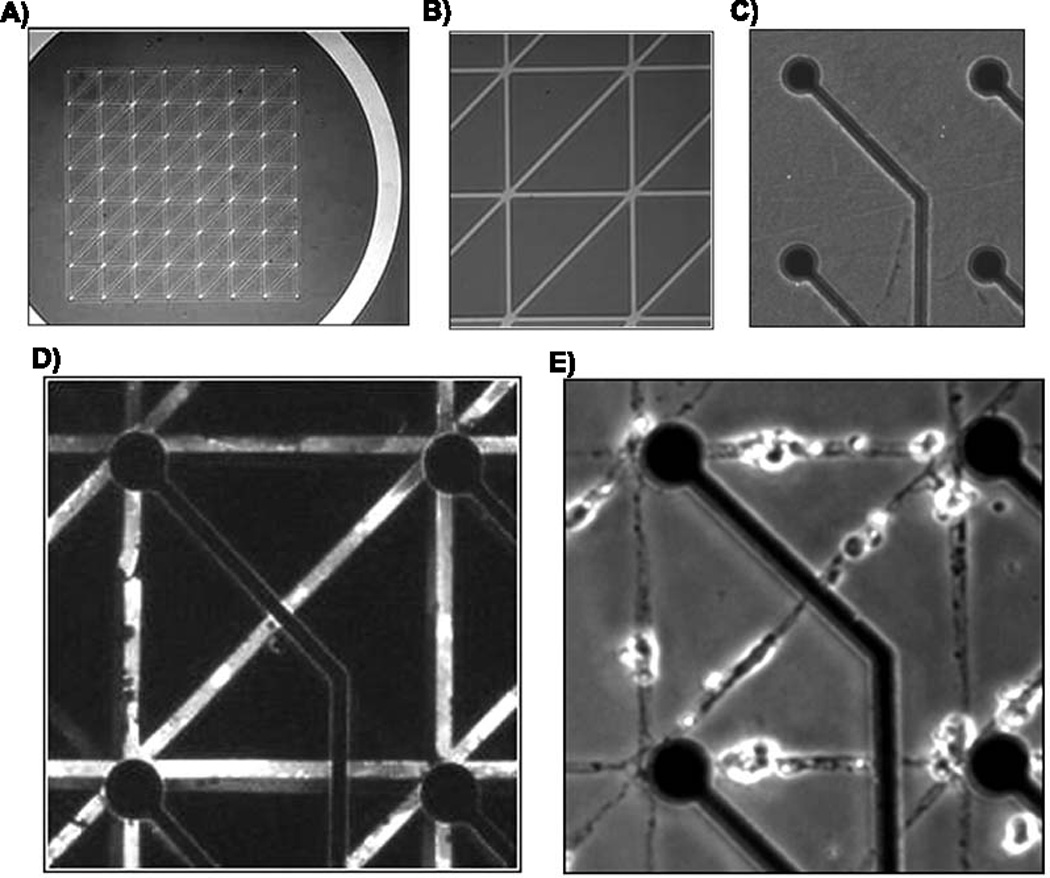

Figure 1A, B shows the mask used to create the patterned substrates on 200 µm centers over electrodes on an MEA. A 170 µm wide moat surrounded the patterned area to minimize pattern compression. The electrode array (1C) was stamped with fluorescent poly-lysine ink (1D) to assess the quality of the pattern before seeding. Neurons that were plated on these patterns and cultured for 3 weeks show that our process optimization led to high pattern compliance and high viability (1E). These results were preceded by years of inconsistent stamping, which led us to determine how various process steps affected the quality of the patterns. We examined first the substrate preparation that resulted in permanence of the polylysine pattern for neuron attachment, growth and compliance to the pattern. To make quantitative measurements of stamp ink concentration, we measured fluorescence intensities of the polylysine “ink” on the resultant stamped patterns. We reasoned that treating the SiN3 passivation layer on the array with an oxygen plasma would add negative charges to the surface that would electrostaticly bind the cationic polylysine. However, Figure 2A shows a loss of ink on the pattern, compared to untreated arrays. To counter the ability of water to wash away the pattern, we applied a silanizing linker, 3-GPS, to covalently bind the lysine amino groups of the polylysine ink to the MEA (Nam et al., 2004). Silane coating did not significantly improve the amount of polylysine retained on the pattern compared to untreated arrays. However, the combination of plasma treatment and silanizing agent produced a significantly higher density of polylysine on the patterns. Ultimately, regardless of density, our goal was to optimize the growth of neurons on the patterns. Substrates treated with plasma only allowed more cells to live off pattern, but in general, neurons that failed to migrate onto the pattern died within a week in their off-pattern location. Figure 2B shows that plasma treatment increased the number of neuron somata on the stamped lines 2-fold, compared to no substrate treatment, but MEAs with silane treatment alone or combined with plasma treatment produced an 8-fold increase in the number of viable neurons on pattern lines. Fig. 2C shows that the dependence of neuron density is not a simple function of polylysine ink density. However, arrays with both plasma and silane treatment displayed the highest amount of polylysine transfer that also correlated with good neuron viability on the pattern. In contrast, MEAs with no treatment showed a high amount of polylysine fluorescence transfer but poor cell viability (Fig 2C,D). Viability was improved greatly by the combination of substrate plasma pretreatment followed by 3-GPS silane linker (Fig. 2C,E).

Fig. 1.

Steps in creating patterned growth of neuronal networks. A) entire stamp mask for a 6-connect pattern including moat region, B) higher magnification of A, C) MEA before stamping showing circular electrodes and leads for connection to the amplifier, D) fluorescence of PLL-FITC on stamped MEA substrate, E) neuron growth on stamped MEA substrate after 22 days in culture. Each square is 200 µm on a side.

3.1.b. Polylysine preparation

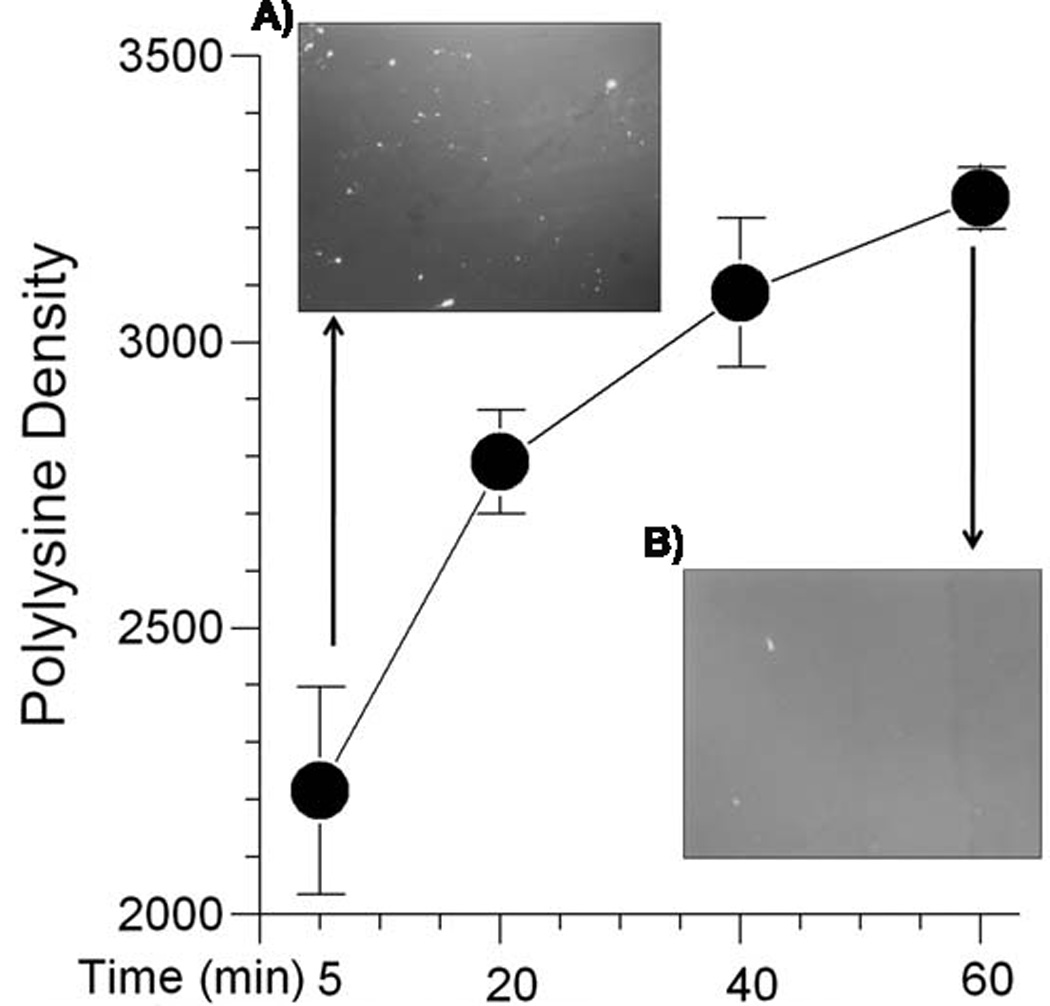

The preparation of the ink affected the qualitative distribution of the polylysine substrate pattern. Aggregation of polylysine on stamp patterns was an obstacle in reproducible patterns as well as neuron survival within a week of plating. We began by thawing polylysine mixtures for 5 min in preparation for inking the stamps. Fig. 3A shows a common result of aggregates of high density polylysine in the ink associated with insufficient dissolution of frozen polylysine. By dissolving the polylysine polymer for longer periods at 37 °C, we obtained more uniform dissolution and observed an overall higher fluorescent intensity of polylysine (3B). The smallest standard errors after 60 min. of dissolution also reflect greater uniformity in the ink compared to the large deviations at shorter times.

Fig. 3.

Effect of polylysine dissolution time on dispersion and uniformity. A) Image of polylysine stock thawed 5 min. shows bright specs of aggregated polylysine and uneven brightness. B) Image after thawing for 60 min. shows uniformly bright field. Main graph shows the highest fluorescence intensity with the lowest variability in solution (as measured by the standard error) for 60 min. dissolution compared to shorter times (n = 5 glass coverslips for each condition, 4 fields of 0.145 mm2 for each slip).

3.1.c. Stamp preparation prior to inking

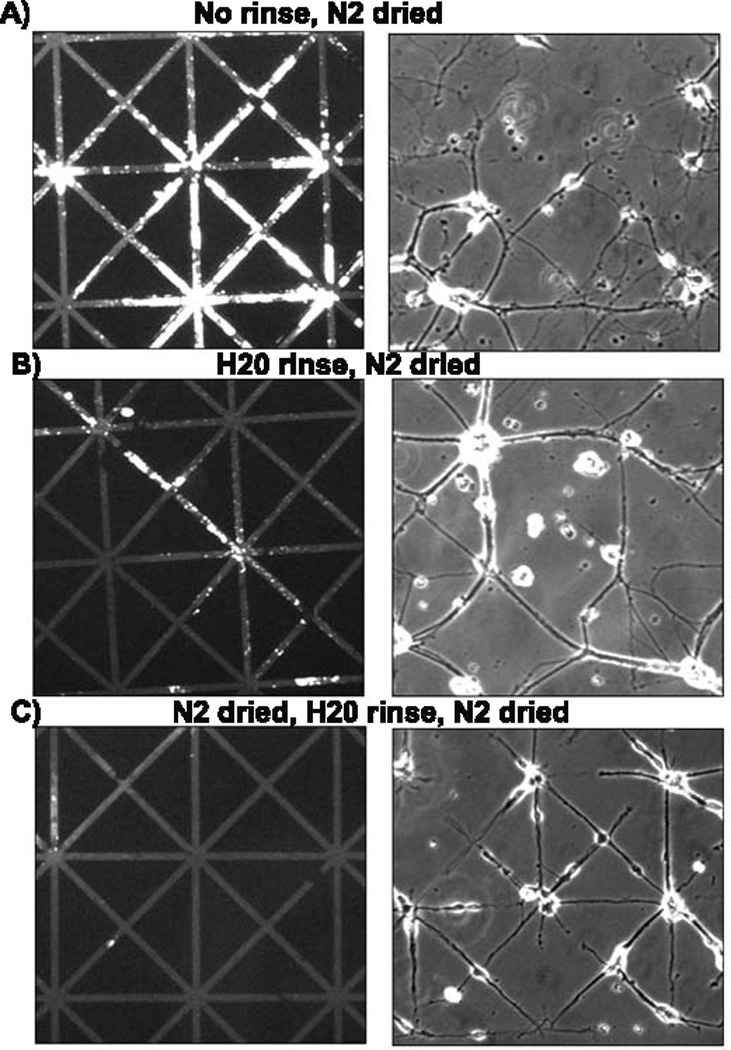

The stamp preparation after soaking in SDS (Chang et al., 2003), prior to inking also affected the quality of the polylysine transfer to the patterns and neuron growth on the patterns. When SDS was cleared by simply blow drying with a stream of nitrogen before soaking in polylysine ink, aggregates of polylysine transferred onto glass coverslip substrates resulting in clustered, non-compliant growth of neurons and cell death (Fig. 4A). Stamps that were rinsed with water first and then dried also produced non-uniform patterns as well as poor compliance and neuron clusters (Fig. 4B). However, if the SDS-coated stamps were blown dry, rinsed in water then blown dry again, the polylysine ink was distributed much more evenly over the pattern and neurons grew with good pattern compliance and survival beyond 3 weeks (4C). These investigations of processing steps suggest that an efficient transfer of polylysine by stamping results in uniform transfer with less clumping and subsequently better neuron survival on the patterns.

Fig. 4.

Methods for removal of excess polylysine from stamps affect impression and subsequent cell growth on glass coverslips. PDMS stamps were submerged in 10% SDS for 20 min then, A) drying in a stream of nitrogen without any rinse. B) Water rinse and drying, C) Brief drying followed by water rinse and drying again. Only the last procedure resulted in acceptable growth of neurons (right panels).

3.2 Pattern compliance

With the improved stamp and substrate processing steps, Fig. 5 shows high compliance of neurons to polylysine patterned substrates of increasing complexity with 4, 6, or 8 connections per node. Fig. 5E shows that the adjustments of lower plating density for neurons on patterns produced net densities comparable to culture densities on uniform substrates of polylysine. Only 0.9% of neurons survived off of the patterned area of 4-connect patterned substrates. Similarly low off-pattern survival was seen for the 6-connect and 8-connect patterns. Neurons plated on patterned MEAs were attracted almost exclusively to the polylysine patterns. Net densities of somata on patterns paralleled our theoretical soma densities based on pattern areas. A slightly higher percent of soma counts on pattern for the 6 and 8 connect patterns were probably due to closer proximity of a pattern to the randomly applied neurons during the first days of neuron migration onto the pattern (Corey et al., 1991). Neuron densities for the patterns above 50 cells/mm2 were not employed because of neuron cluster formation and poor pattern compliance.

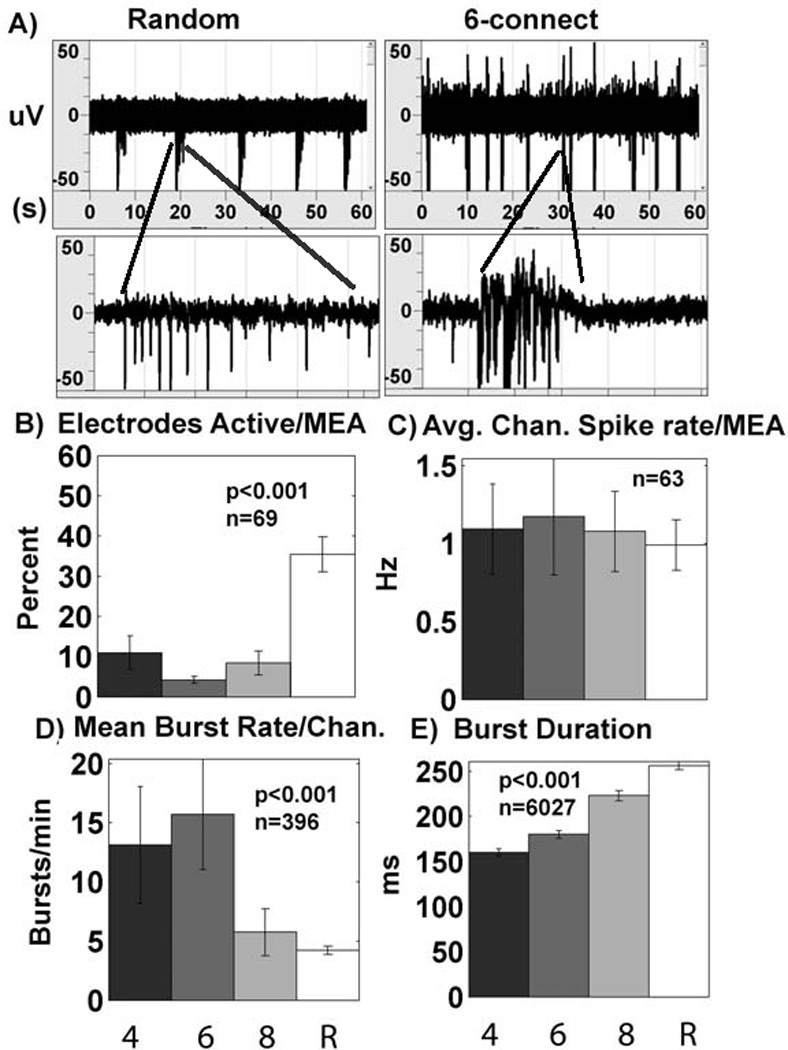

3.3 Spike activity analysis

We were able to record activity from arrays with all types of substrate patterns at 21–26 days in culture. From ten parameters that characterize activity, we statistically evaluated the effect of substrate pattern complexity. Highlights of significant results are presented in Figures 6 and 7. Figure 6 shows results from all conditions combined (with and without stimulation and added astroglia) evaluated by ANOVA for the effect of pattern connections. The burst nature of the spike patterns varied with substrate pattern complexity (Fig. 6A). In contrast to our hypothesis that substrate patterns with nodes over the electrodes would result in greater efficiency of detecting the activity of action potentials, Figure 6B shows a 4-fold lower percentage of active electrodes in patterned cultures compared to conventional random cultures (ANOVA for connections). Despite differences in net cell densities and the number of connections offered to neurons, Figure 6C shows that all cultures had a similar average channel spike rate near 1 Hz. However, several aspects of the nature of the spiking activity were dependent on the substrate pattern complexity. Mean burst rates seen in Figure 6D were near 15 bursts per minute in both 4-connect and 6-connect cultures, but burst rates were 3-fold lower for 8-connect and random networks at five bursts per minute. Figure 6E shows a monotonic increase in spontaneous burst duration with increasing pattern complexity. 4-connect cultures had the shortest burst durations at 160 ms compared to random cultures that had a 1.6-fold higher burst duration of 257 ms.

Fig. 6.

Spiking activity on patterns of increasing complexity. A) Spike waveforms comparing 6-connect patterned network bursts with random bursts. Random networks have longer lasting bursts (300ms window) but fewer bursts/min (60s window) compared to 6-connect patterned networks. B) Percent electrodes active is low for all patterns (4, 6, 8 connect) compared to random cultures (n= degrees of freedom for 73 arrays; ANOVA for connections). C) Average channel spike rate is unaffected by pattern complexity (n= degrees of freedom from 67 active arrays). D) Mean burst rate declines with pattern complexity (n= degrees of freedom for 400 active electrodes; ANOVA for connections), E) Burst duration increases with pattern complexity (n= degrees of freedom for 6031 bursts; ANOVA for connections). Results collected for all conditions combined: non-stimulated, stimulated, without added astroglia, with added astroglia. 4, 4-connect pattern; 6, 6-connect pattern; 8, 8-connect pattern; R, random network.

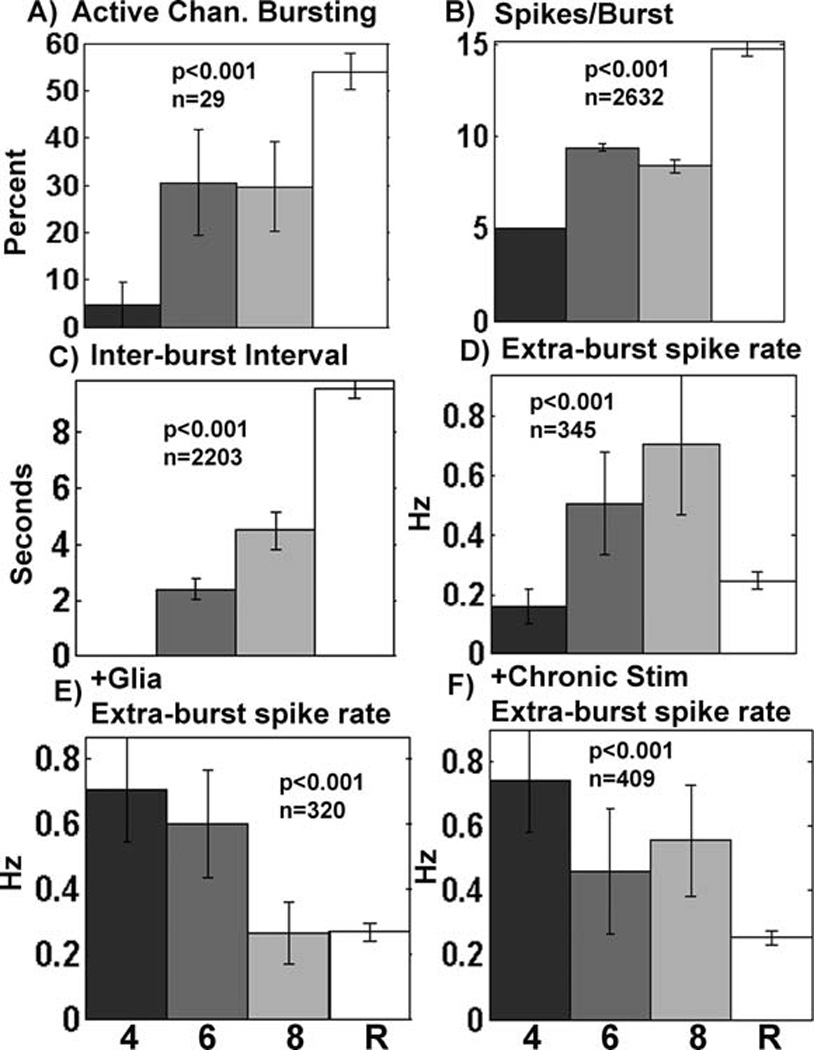

Fig. 7.

Effect of stimulation and astroglia addition on burst characteristics. A–D) Unstimulated data (with and without added astroglia) show increased activity with pattern complexity. A) Percent of active electrodes (n=degrees of freedom for 33 arrays), B) spikes per burst (n=degrees of freedom for 2636 bursts), C) interval between bursts (n=degrees of freedom for 2207 bursts on channels with 2 or more bursts), D) isolated spike rate (n=degrees of freedom for 349 electrodes), E) with addition of astroglia, isolated spike rates declined with pattern complexity (n=degrees of freedom for 324 electrodes), or F) as a result of chronic stimulation during development (n=degrees of freedom for 413 electrodes). 4, 6, 8, R as in Fig. 6.

Figure 7 shows several other burst characteristics affected by pattern complexity and the interaction with chronic stimulation or added astroglia. For networks that received no external stimuli, Figure 7A shows an increase in the percentage of active electrodes bursting with substrate pattern complexity. Spikes/burst increased from 5 for the 4-connect patterns to 15 in the random networks (Figure 7B). Figure 7C shows that the time between bursts increased from 2 to almost 10 s for random networks without external stimulation (4-connect arrays did not have more than 1 burst per electrode).

We defined extra-burst activity as spikes not associated with bursts, i.e., fewer than 5 spikes in a group. For networks without external stimulation, Figure 7D shows a monotonic increase in extra-burst spike rate with pattern complexity up to the sharp drop-off seen with the extra-burst spike rates in random cultures. Interestingly, for networks that either received extra astroglia (Figure 7E) or chronic stimulation (7F), the relationship reversed. Under these conditions, extra-burst spike rate decreased with increasing substrate pattern complexity. The complete data set and statistical accounting is included as supplemental information Figures S1, S2 and Tables S1, S2. Table S3 contrasts differences in experimental parameters of data collection for this work and our prior publications (Brewer et al., 2009; Boehler et al., 2007).

3.4 Chronic stimulation or added astroglia fail to increase active electrodes in NbActiv4

Since the percentage of active electrodes was lower on the patterned substrates than on the unpatterned random substrates (Figure 6B), we attempted to boost activity by chronically stimulating the networks for two weeks during development. Previously reported results in Brewer et al., 2009 showed that chronic stimulation in random networks caused up to a 50% higher number of active electrodes per MEA compared to unstimulated conditions and increased the frequency of spontaneous activity within bursts. Chronic stimulation of networks in the current study did not increase the percentage of active electrodes (F(1,65)=0.3, p=0.6; Supplemental Figure S1A, Table S1A) or other burst parameters other than average channel spike rate. Independent of the number of connections, the spike rate of active channels doubled with chronic stimulation (F(1,59)=5.1, p=0.028; Supplemental Figure S1D, Table S1D), but without an effect of connections (F(2,59)=0.1, p=0.94). Similarly, addition of astroglia to the networks (Boehler et al., 2007) failed to increase the percentage of active electrodes (F(1,65)=0.5, p=0.46; Supplemental Figure S2A, Table S2A). Unlike the effect of chronic stimulation, added astroglia did not cause an increase in average channel spike rate (F(1,59)=0.08, p=0.8; Supplemental Figure S2D, Table S2D).

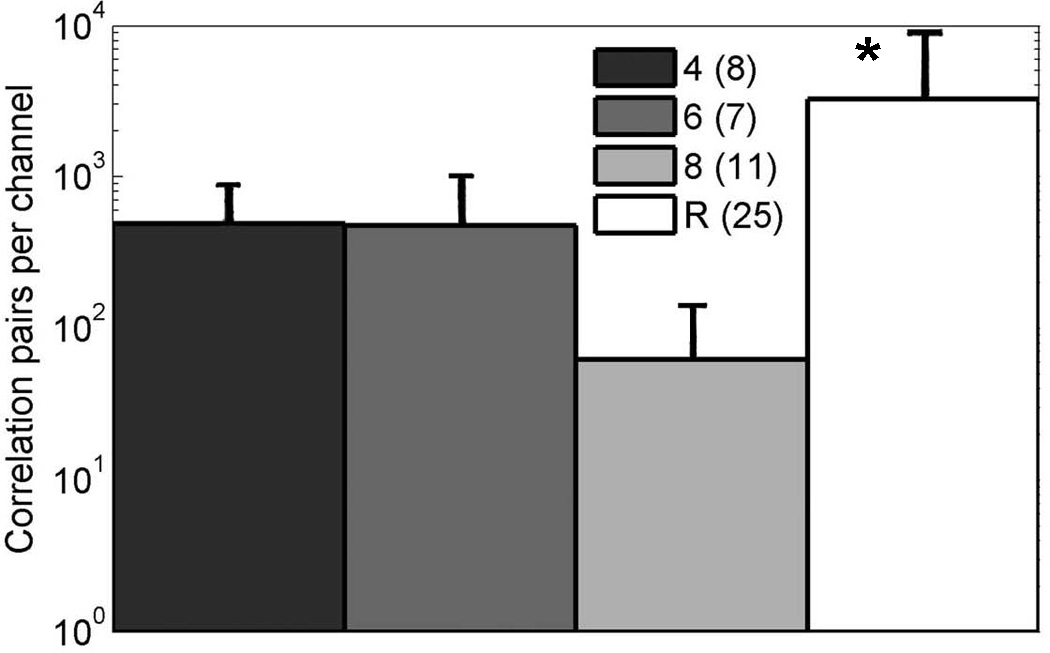

3.5 Substrate patterns fail to influence network cross-correlations of activity

Chiappolone et al. (2006) computed cross-correlations of activity on different channels and their coincidence indices to evaluate the connectedness of the network. Because random networks under our conditions display an average synaptic delay time of 4–5 ms and total time for a stimulus to cross the network of 20 ms (Ide et al., 2010), we computed the cross-correlations of spontaneous spikes between electrodes within these narrow limits for the patterned networks and divided by the number of active electrodes for each array. Fig. 8 shows the frequencies of correlated spikes per active electrode, averaged over arrays for each level of pattern complexity. Clearly, substrate pattern complexity fails to significantly influence the ability of the networks to communicate in a correlated manner, and correlations were 6-fold lower on the patterned substrates compared to the random networks (ANOVA F(1,49)=6.3, p=0.015).

Fig. 8.

Compared to random networks, patterned substrates produce low numbers of spike pairs cross-correlated within a 20 ms window on separate electrodes, averaged over number of arrays (n indicated). Asterisk, ANOVA F (1,49)=6.3, p=0.015. The correlated pairs were divided by the number of active electrodes for each array.

4. Discussion/Conclusion

These studies document significant improvements in process steps for micro-stamping a variety of substrate patterns to produce reliable and reproducible neuronal patterns. Three critical processing parameters were identified. First, thorough dissolution of the large polylysine polymer produced more uniform patterns. Second, the manner of stamp rinsing to retain enough anionic SDS and attract the cationic polylysine was beneficial. Third, we prepared the surface of the electrode array with oxygen plasma and employed the 3-GPS covalent linker to receive the stamped pattern with durability for quality neuron compliance over a period of weeks. Together, these process improvements allowed us create a series of reproducible geometric patterns of systematically increasing complexity to test how the number of connections influenced properties of the network. Counts of somata on and off pattern suggest compliance and viability above 90% (Fig. 5E).

Although the systematically designed increases in pattern complexity resulted in high reproducibility of viable neuron compliance to the pattern in close proximity to electrodes, over periods of 3 weeks, the methods failed to increase the percentage of active electrodes, spike rates or correlated activity across the network. Several factors were considered to explain the low activity on the patterns. 1) A low neuron density could account for lower activity, but Figure 5E shows that the neuron densities on the patterned substrates were within 50% of those of random networks. Although the neuron density for the 4-connect pattern was 80% of that on random substrates, active electrodes were only 25% of that on random substrates. Plating at two-fold higher densities on the patterns results in large clusters of neurons, especially over the electrodes that frequently get swept off the substrate during medium changes. 2) We considered whether astroglia grew better on random substrates than patterned substrates. If so, then addition of extra astroglia to the patterned networks (Boehler et al., 2007) might increase activity, but we did not observe a significant increase in the NbActiv4 medium which already provides the cholesterol known to be provided by astroglia (Brewer et al., 2008). 3) We also considered whether chronic external stimulation would increase activity on the patterned substrates (Brewer et al., 2009; Ide et al., 2010). However, stimulation did not enhance activity of the networks on patterned substrates. 4) If the limited connections on patterns impaired development (Wagenaar et al., 2006), then spike rates on active electrodes would not be constant as in Fig. 6C, burst rate would not be high as in 6D and burst duration would not be low as in 6E. All of these measures are in the direction of maturation of activity (Wagenaar et al., 2006). These arguments also suggest that local trophic factor concentrations did not limit individual neuron viability or activity.

Finally, 5) A likely remaining explanation is that the limited connections between neurons on the 10 µm patterned substrates (as few as 4–8 one-to-one connections/neuron) limited network wiring. Individual neuron activity was not affected by the patterns (Fig. 6C), but synapse density was probably low on the 10 µm wide lines of these patterns. Previous work with 40 µm lines produced 300–600 synaptophysin tagged synapses/neuron and 31% active electrodes (Chang et al., 2006), similar to the random cultures here. This synapse density remains less than the 6,000 synapses/neuron in the random networks on higher density two-dimensional substrates (Brewer et al., 2009) and 10,000 connections in the 3-dimensional rat brain (Braitenberg & Schuz, 2004). Further, the range of neuron phenotypes (e.g. CA1, CA3 and interneurons and even subtypes within these) that appear to self-select for connection with certain specificities in the brain (Moser, 2011) may preclude wiring of necessary network connections in our restrictive patterns even in the presence of physical proximity. The cell density in the patterned networks was controlled to produce the same local neuron density, but does result in a 10-fold lower total number of neurons in the patterns than in random networks. In order to maximally communicate, hippocampal networks may require higher connectivity by: a) a larger number of neurons in the network or b) a higher density of neurons to supply sufficient trophic factors.

Two important observations about network dynamics emerged from our study of patterned substrates. First, spike rates were constant on electrodes that were active, regardless of pattern complexity. This suggests that neurons are designed for spike rate homeostasis. Others have observed spike rate homeostasis in vivo (Smith et al., 2000; Buzsaki et al., 2002; Maffei and Turrigiano, 2008), in ex vivo slices (Stewart and Plenz, 2008) and in modeling (Clopath et al., 2010). The unique design of our network patterns extends the range of conditions over which the principle of homeostasis applies to small networks and possibly individual neurons. Second, burst duration increased monotonically with pattern complexity. Since a burst of activity at rates up to 90 Hz requires numerous energy-dependent ion pumps to prevent loss of ionic homeostasis and feedback controls to limit runaway or run-down of activity, we hypothesize that the increase in connectivity enables more opportunities for inhibitory control to limit runaway activity, but allow for longer bursts. This interpretation is supported by slice studies in the amygdala (Samson and Pare, 2006), barrel cortex (Sun et al., 2006) and hippocampus (Ellender et al., 2010). Alternatively, longer durations of bursts could result from a richer network that provides multiple re-entrant pathways for both inhibitory (local) and excitatory influences through the extended network. These network excitatory and inhibitory inputs could be influenced dramatically by the addition of astroglia (Fig. 7E) or chronic stimulation (7F). For a 4 connect pattern with reduced local feedback, the inhibition is down, making for a shorter duration burst of spikes that gives out metabolically and little re-entrant excitation to keep it stimulated.

Others have documented activity on patterned substrates at cellular resolution of 20 µm or less (Hickman et al., 1994; Ravenscroft et al., 1998), but failed to report a benefit of the patterns to increase electrical activity. Hippocampal neurons of various patterns of resolution to follow single neurons had similar passive membrane properties to those of random cultures, but network properties were not analyzed (Matsuzawa et al., 2000; Wyart et al., 2002). Elaborate micro-cages were built to promote neuron-electrode proximity with connectivity developing to the level of 20–60% of all connections (Erickson et al., 2008). However, connection paths were not controlled by patterns in this work. Thus, the caged neuron approach is superior for neuron-electrode coupling, but like random networks, has not evaluated a defined set of connections. Vogt et al. (2004; 2005a,b) used PDMS stamps inked with ECM-gel and poly-D-lysine to create rectangular features of cell resolution (4 µm wide lines with 12 µm nodes) to meticulously record pairs of neurons by patch clamp, but did not have access to the network on an electrode array. Cultured cortical networks of sizes 50, 104 and 106 neurons on electrode arrays all developed similar burst rates of 6/min, but the smallest feature size of the patterns was 40 µm, still allowing for thousands of synapses (Segev et al., 2002). Thermo ablation of agarose was used to pattern linear hippocampal networks of cellular resolution with demonstrated network activity, but variations in network size or geometry were not reported (Suzuki et al., 2005). Elegant patterns of triangles were used to directionally connect reliable networks of 100 µm lines, but cell resolution and variation of pattern dimensions was not evaluated (Feinerman et al., 2008). Overall, to the best of our knowledge, the work presented here is the first to systematically evaluate the effect of a patterned substrate on network activity.

In summary, we have developed techniques for producing reliable, durable and reproducible patterns on which neurons will grow and produce spontaneous activity after 3–4 weeks. There is some influence of pattern complexity on burst characteristics such as burst duration, but in general spontaneous activity is low on the constrained patterns despite localization of neuron somata over electrodes. Low activity on patterns is proposed to result from physical restraints on opportunities for synaptic connections that limits formation of convergent circuits.

Highlights.

Reliable reproducible 10um stamp patterns for neuron growth.

Compared to random networks, patterns with 4, 6, or 8 connections per node exhibit low network connectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by NIH R01 NS052233 (BCW P.I.). NIH had no control over the content of this work. We thank Nathan Wetter-Taylor for assistance with programming the stimulation protocol.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Brewer owns BrainBits LLC, the supplier and manufacturer of NbActiv4 culture medium.

Contributor Information

Michael D. Boehler, Email: mboehler2@siumed.edu.

Stathis S. Leondopulos, Email: stathisleon@gmail.com.

Bruce C. Wheeler, Email: bwheeler@ufl.edu.

References

- Boehler MD, Wheeler BC, Brewer GJ. Added astroglia promote greater synapse density and higher activity in neuronal networks. Neuron Glia Biol. 2007;3:127–140. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X07000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologna LL, Pasquale V, Garofalo M, Gandolfo M, Baljon PL, Maccione A, Martinoia S, Chiappalone M. Investigating neuronal activity by SPYCODE multi-channel data analyzer. Neural Netw. 2010;23:685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch DW, Corey JM, Weyhenmeyer JA, Brewer GJ, Wheeler BC. Microstamp patterns of biomolecules for high-resolution neuronal networks. Med Biol. Eng Comput. 1998;36:135–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02522871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch DW, Wheeler BC, Brewer GJ, Leckband DE. Long-term stability of grafted polyethylene glycol surfaces for use with microstamped substrates in neuronal cell culture. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1035–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Boehler MD, Ide AN, Wheeler BC. Chronic electrical stimulation of cultured hippocampal networks increases spontaneous spike rates. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2009;184:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ, Boehler MD, Jones TT, Wheeler BC. NbActiv4 medium improvement to Neurobasal/B27 increases neuron synapse densities and network spike rates on multielectrode arrays. J Neurosci. Methods. 2008;170:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Csicsvari J, Dragoi G, Harris K, Henze D, Hirase H. Homeostatic maintenance of neuronal excitability by burst discharges in vivo. Cereb. Cortex. 2002;12:893–899. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.9.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JC, Brewer GJ, Wheeler BC. A modified microstamping technique enhances polylysine transfer and neuronal cell patterning. Biomaterials. 2003;24:2863–2870. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappalone M, Bove M, Vato A, Tedesco M, Martinoia S. Dissociated cortical networks show spontaneously correlated activity patterns during in vitro development. Brain Res. 2006;1093:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clopath C, Busing L, Vasilaki E, Gerstner W. Connectivity reflects coding: a model of voltage-based STDP with homeostasis. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:344–352. doi: 10.1038/nn.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey JM, Wheeler BC, Brewer GJ. Compliance of hippocampal neurons to patterned substrate networks. J Neurosci Res. 1991;30:300–307. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490300204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey JM, Wheeler BC, Brewer GJ. Micrometer resolution silane-based patterning of hippocampal neurons: critical variables in photoresist and laser ablation processes for substrate fabrication. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1996;43:944–955. doi: 10.1109/10.532129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulcey CS, Georger JH, Jr, Krauthamer V, Stenger DA, Fare TL, Calvert JM. Deep UV photochemistry of chemisorbed monolayers: patterned coplanar molecular assemblies. Science. 1991;252:551–554. doi: 10.1126/science.2020853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellender TJ, Nissen W, Colgin LL, Mann EO, Paulsen O. Priming of hippocampal population bursts by individual perisomatic-targeting interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:5979–5991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3962-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson J, Tooker A, Tai YC, Pine J. Caged neuron MEA: a system for long-term investigation of cultured neural network connectivity. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2008;175:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinerman O, Rotem A, Moses E. Reliable neuronal logic devices from patterned hippocampal cultures. Nature Physics. 2008;4:967–973. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman JJ, Bhatia SK, Pike CJ, Cotman CW. Rational pattern design for in vitro cellular networks using surface photochemistry. 1994:607–616. [Google Scholar]

- Ide AN, Andruska A, Boehler M, Wheeler BC, Brewer GJ. Chronic network stimulation enhances evoked action potentials. J. Neural Eng. 2010;7:16008. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/7/1/016008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam L, Shain W, Turner JN, Bizios R. Selective adhesion of astrocytes to surfaces modified with immobilized peptides. Biomaterials. 2002;23:511–515. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinfeld D, Kahler KH, Hockberger PE. Controlled outgrowth of dissociated neurons on patterned substrates. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:4098–4120. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04098.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccione A, Gandolfo M, Massobrio P, Novellino A, Martinoia S, Chiappalone M. A novel algorithm for precise identification of spikes in extracellularly recorded neuronal signals. J Neurosci. Methods. 2009;177:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei A, Turrigiano GG. Multiple modes of network homeostasis in visual cortical layer 2/3. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4377–4384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5298-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa M, Tabata T, Knoll W, Kano M. Formation of hippocampal synapses on patterned substrates of a laminin-derived synthetic peptide. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:903–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser EI. The multi-laned hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:407–408. doi: 10.1038/nn.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y, Chang JC, Wheeler BC, Brewer GJ. Gold-coated microelectrode array with thiol linked self-assembled monolayers for engineering neuronal cultures. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2004;51:158–165. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.820336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft MS, Bateman KE, Shaffer KM, Schessler HM, Jung DR, Schneider TW, Montgomery CB, Custer TL, Schaffner AE, Liu QY, Li YX, Barker JL, Hickman JJ. Developmental neurobiology implications from fabrication and analysis of hippocampal neuronal networks on patterned silane-modified surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Samson RD, Pare D. A spatially structured network of inhibitory and excitatory connections directs impulse traffic within the lateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1599–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev R, Benveniste M, Hulata E, Cohen N, Palevski A, Kapon E, Shapira Y, Ben-Jacob E. Long term behavior of lithographically prepared in vitro neuronal networks. Physical Review Letters. 2002;88:118102-1–118102-4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.118102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhvi R, Kumar A, Lopez GP, Stephanopoulos GN, Wang DI, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Engineering cell shape and function. Science. 1994;264:696–698. doi: 10.1126/science.8171320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AC, Gerrard JL, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Effect of age on burst firing characteristics of rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. NeuroReport. 2000;11:3865–3871. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200011270-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. John PM, Kam L, Turner SW, Craighead HG, Issacson M, Turner JN, Shain W. Preferential glial cell attachment to microcontact printed surfaces. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1997;75:171–177. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CV, Plenz D. Homeostasis of neuronal avalanches during postnatal cortex development in vitro. J Neurosci. Methods. 2008;169:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun QQ, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Barrel cortex microcircuits: thalamocortical feedforward inhibition in spiny stellate cells is mediated by a small number of fast-spiking interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1219–1230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4727-04.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki I, Sugio Y, Jimbo Y, Yasuda K. Stepwise pattern modification of neuronal network in photo-thermally-etched agarose architecture on multi-electrode array chip for individual-cell-based electrophysiological measurement. Lab Chip. 2005;5:241–247. doi: 10.1039/b406885h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt AK, Brewer GJ, Decker T, Bocker-Meffert S, Jacobsen V, Kreiter M, Knoll W, Offenhausser A. Independence of synaptic specificity from neuritic guidance. Neuroscience. 2005b;134:783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt AK, Brewer GJ, Offenhausser A. Connectivity patterns in neuronal networks of experimentally defined geometry. Tissue Eng. 2005a;11:1757–1767. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt AK, Stefani FD, Best A, Nelles G, Yasuda A, Knoll W, Offenhausser A. Impact of micropatterned surfaces on neuronal polarity. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;134:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt AK, Wrobel G, Meyer W, Knoll W, Offenhausser A. Synaptic plasticity in micropatterned neuronal networks. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2549–2557. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar DA, Pine J, Potter SM. An extremely rich repertoire of bursting patterns during the development of cortical cultures. BMC. Neurosci. 2006;7:11–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler BC, Corey JM, Brewer GJ, Branch DW. Microcontact printing for precise control of nerve cell growth in culture. J Biomech. Eng. 1999;121:73–78. doi: 10.1115/1.2798045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyart C, Ybert C, Bourdieu L, Herr C, Prinz C, Chatenay D. Constrained synaptic connectivity in functional mammalian neuronal networks grown on patterned surfaces. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;117:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.