Abstract

We studied postural adjustments associated with a quick voluntary postural sway under two conditions, self-paced and simple reaction-time. Standing subjects were required to produce quick discrete shifts of the center of pressure (COP) forward. About 400–500 ms prior to the instructed COP shift, there were deviations of the COP in the opposite direction (backwards) accompanied by changes in the activation levels of several postural muscles. Under the reaction-time conditions, the timing of those early postural adjustments did not change (repeated measures MANOVA: p>0.05) while its magnitude increased significantly (confirmed by repeated measures MANOVA: p<0.05). These observations are opposite to those reported for anticipatory postural adjustments under simple reaction time conditions (a significant change in the timing without major changes in the magnitude). We conclude that there are two types of feed-forward postural adjustments. Early postural adjustments prepare the body for the planned action and/or expected perturbation. Some of these preparatory actions may be mechanically necessary. Later, anticipatory postural adjustments generate net forces and moments of force acting against those associated with the expected perturbation. Both types of adjustments fit well the referent configuration hypothesis, which offers a unified view on movement-posture control.

Keywords: posture, sway, feed-forward control, EMG

Introduction

When a standing person performs a voluntary action, changes in the activation levels of postural muscles may be seen 100 ms or so prior to the action initiation. These changes have been addressed as anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs; Belen'kii et al., 1967; reviewed in Massion, 1992). It has been commonly assumed that the purpose of APAs is to generate forces and moments of force directed against those expected from the perturbation (Bouisset and Zattara, 1987; Ramos and Stark, 1990; Aruin and Latash, 1995).

Later studies, however, have shown that characteristics of APAs depend not only on the magnitude and direction of an expected perturbation but also on a variety of other factors. In particular, even when parameters of the perturbation were kept unchanged, APAs showed modulation with characteristics of the action that triggered the perturbation (Aruin and Latash, 1995), stability of the postural task (Friedli et al., 1984; Nouillot et al., 1992; Aruin et al., 1998), and the time changes in the postural task (Hirschfeld and Forssberg, 1991; Stapley et al., 1998; Krishnamoorthy and Latash, 2005). Several studies reported changes in the APA timing under time pressure: During self-paced actions, APAs typically start 100±50 ms prior to the activation of the prime mover with respect to the instructed action, while under reaction time conditions, APAs start nearly simultaneously with the prime mover activation and their pattern shows consistent modifications such as speeding-up the alternating activation bursts in the agonist-antagonist muscle pairs acting at postural joints (Lee et al., 1987; Zattara and Bouisset, 1988; Benvenuti et al., 1997; De Wolf et al., 1998; Slijper et al., 2002).

When a person prepares to make a whole-body action, for example to take a step, postural adjustments are seen several hundred ms prior to the stepping foot take-off (Crenna and Frigo, 1991; Elble et al., 1991; Lepers and Breniere, 1995; Halliday et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2005), which is much earlier than typical APAs. The purpose of such early postural adjustments is to ensure adequate mechanical conditions for the planned action. In particular, prior to step initiation, such adjustments include shifting the center of pressure (COP) backwards and towards the supporting foot (after a transient deviation towards the stepping foot). In most of the mentioned studies, these adjustments have also been addressed as APAs. The main purpose of the current study has been to show that such adjustments (we are going to address them as “early postural adjustments”, EPAs) differ from APAs not only quantitatively, that is in their relative timing with respect to the action initiation, but also qualitatively suggesting that EPAs and APAs are produced by different neural mechanisms.

The idea of feed-forward postural control fits naturally the referent configuration hypothesis (RC-hypothesis) on the control of human movements (Feldman and Levin, 1995; Feldman, 2009). This hypothesis is a natural extension of the equilibrium-point hypothesis (EP-hypothesis; Feldman, 1966; 1986). According to the RC-hypothesis, movements are produced by physiological signals (depolarization of neuronal pools) that lead to changes in a referent body configuration, which represents a set of referent values for salient variables expressed in task relevant referent coordinates. When a body reaches a RC, muscle activation levels are expected to be at zero while any deviation from the RC leads to non-zero muscle activations trying to move the body towards the RC. Changing a RC at the upper (task related) level of the control hierarchy leads to a sequence of few-to-many mappings (Latash 2010a,b) resulting in signals to motoneuronal pools and in shifts of the threshold of the tonic stretch reflex, as in the classical description within the EP-hypothesis. An important feature of the RC-hypothesis is that it unites the control of posture and movement into a single scheme based on a solid foundation from classical physics and matching well the known neuromuscular physiology. EPAs and APAs represent changes in muscle activation patterns that are produced by the central nervous system in anticipation of a perturbation (and/or an action). As such, they may be viewed as associated with a shift of the pre-existent RC.

In one of the earlier studies (Wang et al., 2006), a qualitative observation was made that, when the same action (step initiation) was produced at a natural rate, “very quickly”, and “as quickly as possible” following an imperative auditory signal, postural adjustments showed significant modulation of their amplitude without a comparable modulation in their timing. This finding contrasts the mentioned studies of APAs that reported major changes in the APA timing under reaction time instructions.

In the current study, we used a different task, quick voluntary body sway, to explore how EPAs change between conditions when the same task is performed in a self-paced manned (SP) and under a typical simple reaction time instruction (RT). We hypothesized that there would be changes in the EPA magnitude but not in its timing with a change in the instruction. If the hypothesis is supported, this would mean that two mechanisms are available for the central nervous system to generate feed-forward postural adjustments, not a single mechanism with variable relative timing.

Methods

Subjects

Nine healthy subjects (5 males and 4 females; mean ± SD: age 24 ± 6 years, body mass 67 ± 9 kg, height 169 ± 9 cm), without any known neurological or muscular disorder participated in the experiment. All the subjects gave informed consent based on the procedures approved by the Office for Research Protection of The Pennsylvania State University.

Apparatus

A force platform (AMTI, OR-6) was used to record the horizontal component of the reaction force in the anterior-posterior direction (Fx), the vertical component of the reaction force (Fz), and the moment of force around the frontal axis (My). Following skin preparation with alcohol wipes to reduce skin impedance, disposable self-adhesive electrodes (3M corporation) were used to record the surface muscle activity (EMG) of the following muscles from the right side of the body: tibialis anterior (TA), soleus (S), gastrocnemius - medial head (GM), gastrocnemius – lateral head (GL), biceps femoris (BF), semitendinosus (ST), vastus lateralis (VL), rectus femoris (RF), vastus medialis (VM), lumbar erector spinae (ES), latissimus dorsi (LD) and rectus abdominis (RA). The pairs of electrodes were placed within the central part of the muscles bellies, with inter-electrode distance of 3 cm. The signals from the electrodes were pre-amplified (×3000) and band-pass filtered (60 – 500 Hz). All signals were sampled at 1000 Hz frequency with a 12-bit resolution. A desktop computer (Dell 2.4 GHz) was used to control the experiment and to collect the data using customized LabView-based software (Labview 8.2 – National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). A schematic representation of the experimental setup is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental setup. The electromyographic activity of the following postural muscles was monitored: tibialis anterior (TA), soleus (S), gastrocnemius - medial head (GM), gastrocnemius – lateral head (GL), biceps femoris (BF), semitendinosus (ST), vastus lateralis (VL), rectus femoris (RF), vastus medialis (VM), lumbar erector spinae (ES), latissimus dorsi (LD) and rectus abdominis (RA).

Procedures

In the initial position, subjects were standing barefoot on the force platform with their feet in parallel, the insides of the feet 15 cm apart (hip width). This foot position was marked on the top of the platform and reproduced across trials.

The experiment consisted of: (1) control trials, and (2) quick body sway trials. First, three control trials were conducted. These were later used for normalization of the EMG signals and setting the targets for the main trials. A detailed description of the procedure is given in Danna-Dos-Santos et al. (2007). Briefly, in two trials, the subjects were standing quietly and holding a standard load (5 kg) in front of the body with the arms fully extended in horizontal position for 10 s. The subjects held the load by pressing on the two circular panels attached at each side of the bar. The load was either suspended from the middle of the bar producing a downward force (control trial 1), or it was attached through a pulley system such that it produced an upward acting force on the bar (control trial 2). The time interval between the two trials was 30 s. The third control trial required the subjects to perform continuous voluntary body sway in the anterior-posterior direction. The arms were crossed on the chest with the fingertips placed on the shoulders, and the subjects were asked to sway with maximal amplitude at 0.5 Hz paced by a metronome for 30 s while keeping the feet on the force plate. The target amplitude for the main quick body-sway task was set at 60% of the maximum deviation of the center of pressure when swaying backwards.

The main quick body-sway task was performed under simple reaction time (RT) and self-paced (SP) conditions (24 trials per condition). The order of these two conditions was randomized across subjects. During these trials, continuous visual feedback was provided on the center of pressure trajectory in the anterior-posterior direction (COPAP) by the monitor placed 2.0 m in front of the subject at the eye level. Zero COPAP level for feedback was determined as the average COPAP coordinate over 10 s of quiet standing. In the initial position, subjects were leaning backwards such that their COPAP matched a target set at 60% of maximal backward sway amplitude (as determined in the third control trial). The arms were crossed on the chest with the fingertips placed on the shoulders. The subjects were required to make a quick body sway movement forward; rotating the body about the ankle joins such that the COPAP signal moved to the target position (set at the same distance forward from the zero COPAP coordinate). After performing the motion, the subjects were required to keep the COPAP at the target position for about 5 s, and then to perform a body sway movement backward such that the COPAP ended up matching the initial position.

In the reaction time (RT) conditions, the subjects were asked to perform the described motion as quickly as possible after an auditory signal. The auditory signal was turned on unexpectedly by the experimenter within a 2–8 s time window after the subject occupied the initial position and reported that he/she was ready. In the self-paced (SP) trials, the subjects were asked to perform the required motions in a self-paced manner at any time within a 20-s time window. The rest intervals between trials within a condition were 10 s. There were 5-min rest intervals between conditions. None of the subjects complained of fatigue. Before each condition, subjects were given 3 practice trials.

The first practice trials showed that the subjects typically initiated COPAP shift in the direction opposite to the instructed one. For example, the task of forward body sway started with a transient COPAP shift backwards (see Figure 2) evident for the subject because of the visual feedback on the COPAP trajectory. The subjects were explicitly instructed to try to avoid such transient COPAP deviations during practice trials, but none of them could do this consistently.

Figure 2.

Time profiles for ΔCOPAP (dashed line) and EMG of M. Tibialis Anterior (solid line) averaged across trials for RT condition of a typical subject as well as the visual representation of the definitions for dEPA_ΔCOP as the difference in ΔCOPAP between steady-state and t0, tEPA_ΔCOP as the time of initiation of ΔCOPAP shift calculated from the ΔCOPAP averaged across trials and subjects, tEPA_EMG as the time of initiation of the change in EMG, and AEPA_EMG as the area under the graph from tEPA_EMG to t0. Vertical solid line corresponds to time zero, t0.

Although data were collected for both forward and backward movements, as described above, we will present only data pertaining to forward movement to keep the text focused and concise. Further, this forward movement will be referred to as the “quick body-sway task”.

Data processing

All signals were processed off-line using customized Matlab 7.6 software. The horizontal component of the ground reaction force in the anterior-posterior direction (FX), the vertical component of the ground reaction force (FZ), and the moment of force around the frontal plane (MY) were filtered with 20 Hz low-pass, 2nd order, zero-lag Butterworth filter before calculating the COPAP trajectory:

| (1) |

where dz represents the distance from the surface to the platform origin (0.043 m). The displacement of COPAP (ΔCOPAP) was calculated by subtracting the average COPAP coordinate during quiet stance from COPAP coordinate during continuous voluntary body sway and during the quick body-sway task under the SP and RT conditions. The movement initiation of the quick body-sway task under SP condition (t0_SP) and RT condition (t0_RT) was defined as the point in time when the derivative of ΔCOPAP reached 5% of its maximum value (cf. Olafsdottir et al., 2005; 2007). These values were confirmed by visual inspection and will be referred to as ‘time zero’ (t0) (Fig. 2). Transient COPAP shifts in the direction opposite to the instructed one were defined as early postural adjustments (EPAs). An average ΔCOPAP across trials was calculated for each subject. EPAs in ΔCOPAP time profiles (EPAΔCOP) were characterized by the difference in ΔCOPAP between steady-state and t0 (dEPA_ΔCOP) and by the time of ΔCOPAP shift initiation (tEPA_ΔCOP). The ΔCOPAP at steady-state was the average value within the time interval {-850 ms; −650 ms} prior to t0 defined for each subject across trials. Several subjects showed a graduate drift of ΔCOPAP during the SP condition prior to t0. Due to this drift it was not possible to clearly determine tEPA_ΔCOP for each subject separately. Therefore a ΔCOPAP time pattern across trials and across subjects was calculated. The tEPA_ΔCOP was calculated from the average time profile of ΔCOPAP across subjects for the SP (tEPA_ΔCOP_SP) and RT conditions (tEPA_ΔCOP_RT) separately as the instant in time when ΔCOPAP shifted by more than one standard error from the average value calculated at steady-state. In Figure 2 a time pattern for ΔCOPAP under the RT conditions is shown for a subject that showed similar time profiles to the average ones, to visualize the definitions for tEPA_ΔCOP and dEPA_ΔCOP.

EMG data were rectified and filtered with a 50 Hz low-pass, second order, zero-lag Butterworth filter. Average EMG pattern over trials for the time interval {−900 ms prior to t0; 400 ms after t0} were calculated for each muscle. Early postural adjustments in muscle activity time profiles (EPAEMG) were characterized by the time of initiation (tEPA_EMG) and the area under the graph (AEPA_EMG). The data for each muscle were smoothened with a 50-point moving average. All subjects, in both SP and RT conditions, showed EPAs in TA, GL, and VL. Therefore, quantitative EPA analysis was performed only for those three muscles. We defined tEPA_EMG as the point in time when the average muscle activation level across trials differed for more than 100 ms by more than ± 2 standard deviations from the average value within steady-state (De Wolf et al., 1998; Santos et al., 2010); the values of tEPA_EMG were confirmed by visual inspection. AEPA_EMG was calculated as the EMG integral averaged across trials from tEPA_EMG until t0 in each condition separately. EMG time profiles under the SP and RT condition were demeaned by subtracting the average EMG during steady-state. Figure 2 shows an example of TA EMG averaged across trials for the RT condition for a typical subject including the definitions for tEPA_EMG and AEPA_EMG.

For the RT condition, all the trials with reaction time below 100 ms and over 300 ms were excluded from further analysis. An average of 18 (±2) trials per subject was analyzed, leading to the analysis of 163 trials.

Statistics

Data are presented in the text and figures as means and standard errors. The normality of distribution was verified by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The time of initiation of the change in muscle activity prior to t0 (tEPA_EMG) for the three muscles TA, GL, and VL was compared between the SP and RT conditions using a one-way repeated measures MANOVA with the factor Condition (RT and SP). Note that prior to MANOVA analyses, and to ensure the compliance with the assumption of normality, data were log-transformed using a XLOG = ln(X) formula. Further, one-way repeated measures MANOVA were also applied to examine the differences between SP and RT trials for TA, GL, and VL with regard to the area under the graph for the interval {tEPA_EMG; t0}. The difference in ΔCOPAP between steady state and t0 (dEPA_ΔCOP) was compared for SP and RT trials by a paired samples t-test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Reaction time

All subjects were able to perform the quick body sway movement under both self-paced (SP) and reaction time (RT) conditions without losing balance. Overall, 53 out of 216 RT trials (~25%) were excluded from further analysis based on the introduced selection criteria for RT condition (RT<100 ms and RT>300 ms, see Methods). Across the accepted trials, the average RT ranged from 122 ms to 164 ms with an average of 142 ms (±4 ms).

Patterns of general EMG, and center of pressure

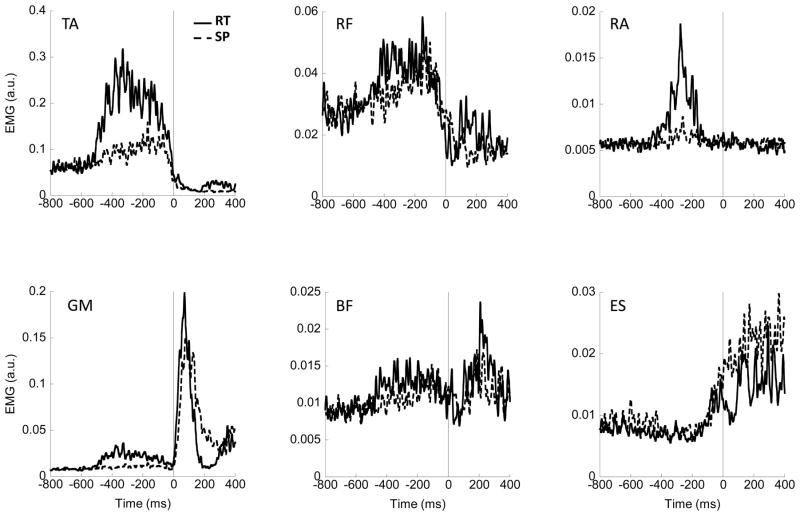

Figure 3 shows the rectified EMGs averaged across trials for a typical subject for selected muscles during the SP and RT conditions. In this particular subject, EPAs are evident in the EMG activity for TA and RF in both SP and RT conditions. In RA and GM, the EPAs are clearly evident under RT condition, but not as pronounced in SP condition. Changes in the activation of ES are not evident until just prior to the initiation of the focal movement. For each subject, EPAs were observed in TA, GL, and VL in both SP and RT conditions.

Figure 3.

EMG data averaged across trials for a typical subject, for reaction-time (RT) condition trials (solid line) and self-paced (SP) condition trials (dashed line). Vertical solid line corresponds to time zero, t0. TA – tibialis anterior; RF – rectus femoris; RA – rectus abdominis; GM – gastrocnemius medialis; BF – biceps femoris; ES – erector spinae

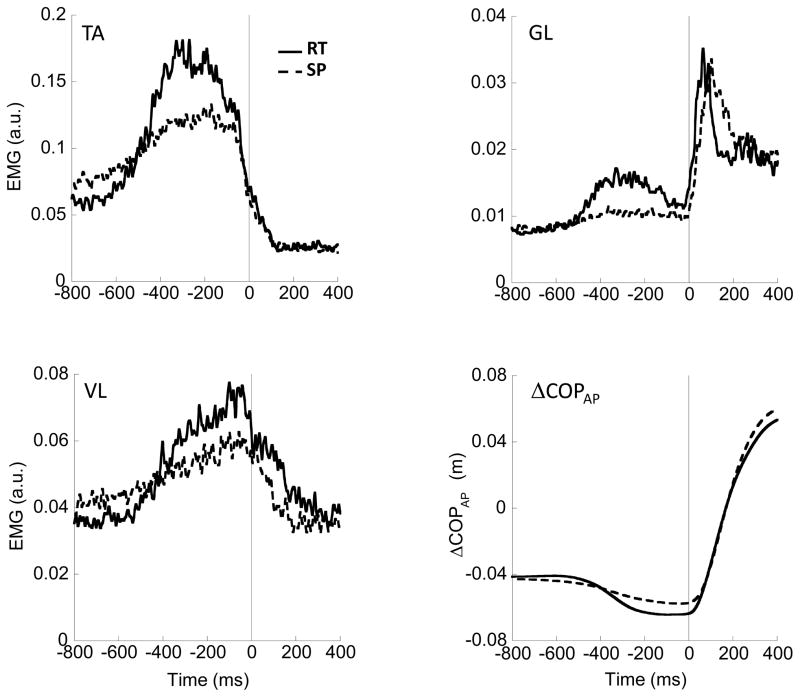

The EMG time profiles of TA, GL, and VL averaged across trials and subjects are shown in Figure 4. There are greater EMG changes in the RT condition than in the SP condition resulting in larger areas under the rectified EMG curves in the RT condition. The time of EPA initiation (tEPA_EMG) was, on average, between 500 and 600 ms prior to the initiation of the focal movement (t0) and was similar under the two conditions (see further text).

Figure 4.

Time profiles of TA – tibialis anterior; GL – gastrocnemius lateralis; VL – vastus lateralis, and the change in COPAP (ΔCOPAP) averaged across trials and subjects in both reaction-time (RT) condition trials (solid line) and self-paced (SP) condition trials (dashed line). EPAs were observed in each of these three muscles for each subject. Vertical solid line corresponds to time zero, t0.

Figure 4 also shows ΔCOPAP indices averaged across subjects (right, bottom) for the SP and RT conditions. The center of pressure shift (ΔCOPAP) was characterized by a transient shift backwards (EPA) prior to the instructed shift forward. The EPA started more abruptly and was of a greater magnitude under the RT condition as compared to the SP condition. The time of ΔCOP shift initiation, tEPA_ΔCOP, was similar for the two conditions, about 465 ms and 469 ms prior to t0 for the SP and RT conditions, respectively.

The time of initiation of the change in EMG activity, tEPA_EMG, was between 550 and 600 ms prior to t0 for both conditions and for each of the three muscles with tEPA_TA_SP = −605 ms (±20 ms) and tEPA_TA_RT = −585 ms (±18 ms), the tEPA_GL_SP was −583 ms (±23 ms) and tEPA_GL_RT was −570 ms (±18 ms) and tEPA_VL was −556 ms (±19 ms) and −548 ms (±23 ms) for SP and RT condition, respectively (Fig. 4). One-way repeated measures MANOVA showed no significant multivariate effects between the conditions.

The magnitude of change in muscle activity (AEPA_EMG) for TA, GL, and RF was, on average, greater for the RT condition (Fig. 5). A one-way repeated measures MANOVA on log-transformed values of AEPA_EMG (following Shapiro-Wilk test) indicated a significant multivariate effect for Condition [F(3,6) = 7.394; p < 0.05]. A subsequent series of one-way repeated measures ANOVAs indicated significant main effects of Condition for TA [F(1,8) = 26.294; p < 0.001], GL [F(1,8) = 13.597; p < 0.01], and VL [F(1,8) = 13.145; p < 0.01]. These results are in line with the greater magnitude of change in ΔCOPAP (dEPA_ΔCOP) in the RT condition (22.4±2.0 mm) than in the SP condition (14.2±1.8 mm) (Fig. 5). this difference was confirmed by a paired-samples t-test [t = −10.745; p < 0.001].

Figure 5.

Magnitude of the change in muscle activity (AEPA_EMG) of TA – tibialis anterior; GL – gastrocnemius lateralis; VL – vastus lateralis and the magnitude of the change in ΔCOPAP (dEPA_ΔCOP) for reaction-time (RT) condition (grey) and self-paced (SP) condition (white).

Discussion

The main hypothesis formulated in the Introduction – that there would be changes in the EPA magnitude but not in its timing with a change in the instruction – has been supported by our findings. Specifically, in contrast to earlier reports on the strong modulation of the APA timing under simple reaction time instructions (Lee et al., 1987; Benvenuti et al., 1997; De Wolf et al., 1998), we found no significant changes in the timing of the EPAs while their magnitude increased significantly under the RT instruction as compared to the SP instruction. The increase in the EPA magnitude is comparable to that described earlier (Wang et al., 2006) and is in contrast to ambiguous reports on the differences in the magnitude of APAs under the SP and RT conditions. Further in this section we address the likely role of the two types of postural adjustments (EPAs and APAs) and re-visit the issue of feed-forward postural adjustments within the referent configuration hypothesis (Feldman and Levin, 1995; Feldman, 2009), which was briefly described in the Introduction.

The Role of Feed-Forward Postural Adjustments

There is no argument that animals and humans frequently act in a predictive fashion (for review see Latash, 2010a; Johansson and Cole, 1992; Davidson and Wolpert, 2003). APAs were arguably one of the first examples of predictive control (Belen'kii et al. 1967) when a voluntary action is performed on the background of a postural task. Further, similar adjustments have been reported for tasks involving postural components limited to a limb in tasks that did not involve standing (Dufosse et al., 1985; Struppler et al., 1993).

Can any postural adjustment to action be considered an APA? The results of our study suggest that this may not be the case. They point at two qualitatively different types of adjustments with different functions and different sensitivity to time pressure, as in the RT conditions. One type of the adjustments occurs a few hundred ms prior to the instructed action initiation. One of the most common examples in the literature is postural adjustments observed prior to step initiation (Crenna and Frigo, 1991; Elble et al., 1991; Lepers and Breniere, 1995). In several studies, those adjustments have been referred to as APAs. We believe that this is imprecise and may be misleading; the two types of adjustments differ in a few important aspects.

First, given typical electromechanical delays (reviewed in Corcos et al., 1992), early postural adjustments (EPAs) occur too early to produce forces and moments of force that would act against potentially destabilizing forces expected from the planned action (or perturbation). Some of these adjustments cannot be separated from the main task because they are mechanically necessary to produce the planned action. In particular, to make a step one has to unload the stepping foot and shift the weight towards the supporting foot. One also has to shift the COP backwards to produce a moment of force tilting the body forward. Along similar lines, in our task, to initiate a quick body sway forward, one had to move the COP backwards initially.

One can define the purpose of EPAs as optimizing posture to facilitate a planned action or reaction. The mentioned adjustments to stepping may be viewed as mechanically necessary. However, this is not always the case. For example, in recent studies (Krishnan et al., 2011a,b), changes in the activation of postural muscles were observed in conditions when the subject was not instructed to perform an action but rather to keep standing while a pendulum approached the subject from the front and hit the subject’s shoulders. The early adjustments were seen about 400–500 ms prior to the impact, which is similar to the timing of EPAs in our experiment. The mentioned adjustments in the study of Krishnan and her colleagues led to only small, delayed COP shifts suggesting that the subjects prepared their posture to the anticipated impact without producing a major net mechanical effect. In contrast, APAs (which were seen later, about 100 ms prior to the impact) were followed by a quick COP shift compatible with the generally accepted hypothesis that the function of APAs is to generate forces and moments against those predicted from the action (Bouisset and Zattara, 1987; Ramos and Stark, 1990; Aruin and Latash, 1995).

Second, a change in the instruction from self-paced to reaction-time leads to qualitatively different adjustments in EPAs and APAs. The APAs show a major shift in their timing (moving closer to the time of action initiation) with only minor changes in their magnitude (Lee et al., 1987; Zattara and Bouisset, 1988; Benvenuti et al., 1997; De Wolf et al., 1998; Slijper et al., 2002). In contrast, in our study, the EPAs showed no significant changes in the timing and major changes in the magnitude (an increase under the RT instruction, cf. Wang et al. 2006).

Postural Adjustments within the Referent Configuration Hypothesis

In the Introduction, we suggested that feed-forward postural control can be naturally discussed within the referent configuration hypothesis (RC-hypothesis) on the control of human movements (Feldman and Levin, 1995; Feldman, 2009). We assume that changing a RC at the upper (task related) level of the control hierarchy leads to a sequence of few-to-many mappings organized in a synergic way, that is, the “many” outputs co-vary to stabilize their combined signal related to the relatively low-dimensional input (Latash, 2010a,b). This scheme unites both voluntary and involuntary muscle activations: The former are observed when a RC is modified by the central nervous system; the latter are seen when an external perturbation is applied to the body without changes in the RC.

EPAs and APAs represent changes in muscle activation patterns that are produced by the central nervous system in anticipation of a perturbation (and/or an action). As such, they may be viewed as associated with a shift of the pre-existent RC. RC shifts may or may not result in changes in the net forces exerted on the environment. For example, one can activate muscles acting at a joint without a net effect (co-contracting the muscles, cf. the co-activation command in Feldman, 1980) or with a net effect (the reciprocal command). The very early timing of the EPAs and the relatively small associated shifts in the mechanical variables reported by Krishnan et al. (2011a,b) suggest that, in certain situations, these adjustments primarily lead to changes in a high-level command analogous to the co-activation command. In contrast, the quick changes in the mechanics during the APAs suggest changes in the reciprocal command.

In conclusion, there appear to be two distinct types of feed-forward postural adjustments: Early postural adjustments (EPAs) with the purpose is to minimize mechanical effects of the planned action and/or expected perturbation on balance, and anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs) that generate net forces and moments of force acting against those associated with the expected perturbation. Both types of adjustments fit well the referent configuration hypothesis, which offers a unified view on movement-posture control. We have to admit a number of limitations of the study. In particular, we observed consistent across subjects and conditions postural adjustments in only a subset of muscles. There is always a possibility that some muscles (whose activity was not recorded in the study) could show a different pattern of activation and different changes in the pattern with a change in the instruction from self-paced to reaction-time. It is practically impossible to record activation levels of all body muscles. Hence, the idea of referent configuration, at which ALL the muscle are at their thresholds for activation, may be hard to confirm experimentally with confidence since always there will be a possibility that an unrecorded muscle behaves differently.

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of Health grants NS-035032 and AG-018751 in part supported this study. Pavle Mikulic is grateful to The National Foundation for Science, Higher Education and Technological Development of the Republic of Croatia for supporting his postdoctoral training at The Pennsylvania State University. We appreciate the helpful discussions with Dr. Alexander Aruin.

Biographies

Miriam Klous graduated in 2001 from the Faculty of Human Movement Science at VU University in Amsterdam (the Netherlands). She received her Ph.D. in sports biomechanics from the University of Salzburg (Austria) in 2007. From 2008–2011 she was a postdoctoral fellow at the Motor Control Lab, Department of Kinesiology at the Pennsylvania State University. Currently she is working as an assistant professor at the College of Charleston and is affiliated with the Medical University of South Carolina. Her research interest is interlimb-coordination between upper and lower extremities in people with stroke and incomplete spinal cord injury.

Pavle Mikulic is a research associate within the Laboratory for Motor Control and Human Performance at the University of Zagreb School of Kinesiology, where he also obtained his Ph.D. degree in 2006. He completed his post-doctoral training in 2009/2010 at the Department of Kinesiology of the Pennsylvania State University. His research interests include (i) modeling and optimizing sport performance, (ii) neuromuscular and mechanical aspects of human movement and performance, and (iii) pediatric exercise physiology. Within these general areas he has (co)-authored 20 papers published in peer-reviewed journals.

Mark L. Latash, Ph.D. is a professor of kinesiology at Penn State University. He is interested in the control and coordination of multi-element systems participating in the production of voluntary movements, the control of posture, multi-joint reaching, finger coordination and the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying normal and disordered motor control. He is the author of about 300 papers in peer-reviewed journals, three single-authored books, and eight edited books. He served as the Founding Editor of Motor Control (1996–2007) and as the first President of the International Society of Motor Control (2001–2005). Dr. Latash is a Fellow in the National Academy of Kinesiology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aruin AS, Forrest WR, Latash ML. Anticipatory postural adjustments in conditions of postural instability. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;109(4):350–9. doi: 10.1016/s0924-980x(98)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruin AS, Latash ML. Directional specificity of postural muscles in feed-forward postural reactions during fast voluntary arm movements. Exp Brain Res. 1995;103(2):323–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00231718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belen'kii VE, Gurfinkel VS, Pal'tsev EI. Control elements of voluntary movements. Biofizika. 1967;12(1):135–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuti F, Stanhope SJ, Thomas SL, Panzer VP, Hallett M. Flexibility of anticipatory postural adjustments revealed by self-paced and reaction-time arm movements. Brain Res. 1997;761(1):59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouisset S, Zattara M. Biomechanical study of the programming of anticipatory postural adjustments associated with voluntary movement. J Biomech. 1987;20(8):735–42. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcos DM, Gottlieb GL, Latash ML, Almeida GL, Agarwal GC. Electromechanical delay: An experimental artifact. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 1992;2(2):59–68. doi: 10.1016/1050-6411(92)90017-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenna P, Frigo C. A motor programme for the initiation of forward-oriented movements in humans. J Physiol. 1991;437:635–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danna-Dos-Santos A, Slomka K, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Muscle modes and synergies during voluntary body sway. Exp Brain Res. 2007;179(4):533–50. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PR, Wolpert DM. Motor learning and prediction in a variable environment. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13(2):232–7. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wolf S, Slijper H, Latash ML. Anticipatory postural adjustments during self-paced and reaction-time movements. Exp Brain Res. 1998;121(1):7–19. doi: 10.1007/s002210050431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufosse M, Hugon M, Massion J. Postural forearm changes induced by predictable in time or voluntary triggered unloading in man. Exp Brain Res. 1985;60(2):330–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00235928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elble RJ, Thomas SS, Higgins C, Colliver J. Stride-dependent changes in gait of older people. J Neurol. 1991;238(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00319700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AG. Functional tuning of the nervous system with control of movement or maintenance of a steady posture. Biophysics. 1966;11:565–78. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AG. Superposition of motor programs--II. Rapid forearm flexion in man. Neuroscience. 1980;5(1):91–5. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AG. Once more on the equilibrium-point hypothesis (lambda model) for motor control. J Mot Behav. 1986;18(1):17–54. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1986.10735369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AG. Origin and advances of the equilibrium-point hypothesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;629:637–43. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77064-2_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AG, Levin MF. The origin and use of positional frames of reference in motor control. Behav Brain Sci. 1995;18:723–806. [Google Scholar]

- Friedli WG, Hallett M, Simon SR. Postural adjustments associated with rapid voluntary arm movements 1. Electromyographic data. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47(6):611–22. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.47.6.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday SE, Winter DA, Frank JS, Patla AE, Prince F. The initiation of gait in young, elderly, and Parkinson's disease subjects. Gait Posture. 1998;8(1):8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(98)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld H, Forssberg H. Phase-dependent modulations of anticipatory postural activity during human locomotion. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66(1):12–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson RS, Cole KJ. Sensory-motor coordination during grasping and manipulative actions. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1992;2(6):815–23. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90139-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klous M, Mikulic P, Latash ML. Two aspects of feed-forward postural control: anticipatory postural adjustments and anticipatory synergy adjustments. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105(5):2275–88. doi: 10.1152/jn.00665.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy V, Latash ML. Reversals of anticipatory postural adjustments during voluntary sway in humans. J Physiol. 2005;565(Pt 2):675–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Aruin SA, Latash ML. Two stages and three components of the postural preparation to action. Exp Brain Res. 2011a;212:47–63. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2694-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Latash ML, Aruin AS. Early and late components of feed-forward postural adjustments to predictable perturbations. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011b doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.09.014. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML. Motor synergies and the equilibrium-point hypothesis. Motor Control. 2010a;14(3):294–322. doi: 10.1123/mcj.14.3.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML. Stages in learning motor synergies: a view based on the equilibrium-point hypothesis. Hum Mov Sci. 2010b;29(5):642–54. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Scholz JP, Schoner G. Motor control strategies revealed in the structure of motor variability. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2002;30(1):26–31. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Scholz JP, Schoner G. Toward a new theory of motor synergies. Motor Control. 2007;11(3):276–308. doi: 10.1123/mcj.11.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WA, Buchanan TS, Rogers MW. Effects of arm acceleration and behavioral conditions on the organization of postural adjustments during arm flexion. Exp Brain Res. 1987;66(2):257–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00243303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepers R, Breniere Y. The role of anticipatory postural adjustments and gravity in gait initiation. Exp Brain Res. 1995;107(1):118–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00228023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massion J. Movement, posture and equilibrium: interaction and coordination. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38(1):35–56. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90034-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouillot P, Bouisset S, Do MC. Do fast voluntary movements necessitate anticipatory postural adjustments even if equilibrium is unstable? Neurosci Lett. 1992;147(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90760-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir H, Yoshida N, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Anticipatory covariation of finger forces during self-paced and reaction time force production. Neurosci Lett. 2005;381(1–2):92–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir H, Zhang W, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Age-related changes in multifinger synergies in accurate moment of force production tasks. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(4):1490–501. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00966.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos CF, Stark LW. Postural maintenance during movement: simulations of a two joint model. Biol Cybern. 1990;63(5):363–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00202753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Schoner G. The uncontrolled manifold concept: identifying control variables for a functional task. Exp Brain Res. 1999;126(3):289–306. doi: 10.1007/s002210050738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JK, Olafsdottir H, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. The emergence and disappearance of multi-digit synergies during force-production tasks. Exp Brain Res. 2005;164(2):260–70. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2248-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slijper H, Latash ML, Mordkoff JT. Anticipatory postural adjustments under simple and choice reaction time conditions. Brain Res. 2002;924(2):184–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapley P, Pozzo T, Grishin A. The role of anticipatory postural adjustments during whole body forward reaching movements. Neuroreport. 1998;9(3):395–401. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struppler A, Gerilovsky L, Jakob C. Self-generated rapid taps directed to the opposite forearm in man: anticipatory reduction in the muscle activity of the target arm. Neurosci Lett. 1993;159(1–2):115–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90812-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Muscle synergies involved in shifting the center of pressure while making a first step. Exp Brain Res. 2005;167(2):196–210. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Muscle synergies involved in preparation to a step made under the self-paced and reaction time instructions. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(1):41–56. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zattara M, Bouisset S. Posturo-kinetic organisation during the early phase of voluntary upper limb movement. 1. Normal subjects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51(7):956–65. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.7.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]