Abstract

AIDS-related Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (AIDS-NHL) constitutes an aggressive variety of lymphomas characterized by increased extranodal involvement, relapse rate and resistance to chemotherapy. PKCβ targeting showed promising results in preclinical and clinical studies involving a wide variety of cancers, but studies describing the role of PKCβ in AIDS-NHL are primitive if not lacking. In the present study, three AIDS-NHL cell lines were examined: 2F7 (AIDS-Burkitt Lymphoma), BCBL-1 (AIDS-Primary Effusion Lymphoma) and UMCL01-101 (AIDS-Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated expression of PKCβ1 and PKCβ2 in 2F7 and UMCL01-101 cells, and PKCβ1 alone in BCBL-1 cells. The viability of 2F7 and BCBL-1 cells decreased significantly in the presence of PKCβ-selective inhibitor at IC50 of 14 μM and 15 μM, respectively, as measured by MTS assay. In contrast, UMCL01-101 cells were relatively resistant. As determined using flow cytometric TUNEL assay with propidium iodide staining, the responsiveness of sensitive cells was associated with apoptotic induction and cell cycle inhibition. PKCβ-selective inhibition was observed not to affect AKT phosphorylation, but to induce a rapid and sustained reduction in the phosphorylation of GSK3β, ribosomal protein S6, and mTOR in sensitive cell lines. The results indicate that PKCβ plays an important role in AIDS-related NHL survival, and suggest that PKCβ targeting should be considered in a broader spectrum of NHL. The observations in BCBL-1 were unexpected in the absence of PKCβ2 expression and implicate PKCβ1 as a regulator in those cells.

Keywords: AIDS-related lymphoma, protein kinase C-beta, Apoptosis, Cell cycle inhibition, Targeted therapy

Background

The armamentarium of traditional anticancer pharmacotherapy includes alkylating agents, antimetabolites, and certain natural products that work by disrupting cell division, thereby causing cell death. Selectivity for cancer cells is limited, generally based on their relatively rapid growth rate, and toxicity is high for nonmalignant healthy cells that are also rapidly growing. By contrast, molecularly targeted therapies have been introduced in recent years for the treatment of cancers including breast cancer, lung cancer and chronic myeloid leukemia, among others. Targeted therapeutics are typically small molecules or monoclonal antibodies designed to interact specifically with cell proteins that play a key role in tumor cell growth, proliferation, invasion or angiogenesis. This novel therapeutic approach is designed to achieve high specificity for tumor cells with relative sparing of normal cells, thereby offering the promise of efficacy with low toxicity [1-3]. AIDS-related Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (AIDS-NHL) is a cancer for which an efficacious targeted therapy is sorely needed. AIDS-NHL is the second most frequent cancer associated with AIDS and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in long-term survivors of HIV infection. The impairment of cellular immunity associated with AIDS is thought to confer a predisposition for cancer development [4]; indeed, malignancy occurs in 25% to 40% of HIV-1 seropositive patients, approximately 10% of which are AIDS-NHL [5, 6].

AIDS-NHL is generally a disease of B-cell origin and is histologically and biologically heterogeneous, reflective of multiple pathogenic mechanisms. The most frequently occurring types, classified according to the 2001 World Health Organization Classification, are AIDS-associated Burkitt lymphoma (AIDS-BL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (AIDS-DLBCL) of centroblastic (AIDS-CB) and immunoblastic (AIDS-IBL) types. Among other less commonly occurring forms, AIDS-NHL may also present as primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) or primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL). As distinct from their counterparts in the general population, AIDS-NHL is often diagnosed at an advanced stage with a high incidence of extranodal involvement at unusual anatomic sites [7]. While AIDS-NHL cells do not demonstrate HIV infection, they are commonly infected with gamma-herpesviruses that likely play important roles in lymphoma pathogenesis. AIDS-BL, AIDS-IBL and PCNSL are commonly infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) at frequencies between 60% to 100%. AIDS-PEL is uniformly infected with Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) and may be co-infected with EBV [8, 9]. Despite advances in understanding pathogenic mechanism, AIDS-NHL remains difficult to treat and often refractory to conventional chemotherapy. AIDS-NHL are generally characterized by a lower response rate to therapy and a higher rate of recurrence as compared with lymphomas of similar histology in the general population [4, 8-10].

The present study was undertaken to examine the possibility that protein kinase C beta (PKCβ), a member of a closely related family of enzymes with serine/threonine kinase activity, might represent an effective therapeutic target for the treatment of AIDS-NHL. PKCβ is known to participate in signaling pathways that regulate cell survival, proliferation, apoptosis and angiogenesis [11, 12]. It is the major PKC isoform expressed in normal and malignant B-cells [13] and is required for B-cell receptor-mediated survival signals in normal lymphocytes. The PKCβ gene expresses two products, designated PKCβ1 and PKCβ2, that are generated by alternative splicing and differ at the C-terminus [11]. PKCβ2 is required for normal B-cell receptor-dependent survival signaling, which it effects by activating NF-κB [14, 15]. Other known targets of PKCβ2 include the prosurvival kinase, AKT, and its downstream effectors glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK3β), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and ribosomal protein S6 kinase (P70S6K) [1, 11, 12, 16]. The role of the PKCβ1 isoform is less clear, and it has been reported to act in various cellular environments as proapoptotic [12, 17] and suppressive of the transformed phenotype [18], or alternatively, as proliferative and prosurvival [12, 19].

By virtue of its central signalling role, PKCβ is currently under consideration as a molecular target for the therapy of several solid tumors [16, 19-27] and in hematological malignancies including multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [11, 12, 28-35]. A gene expression profiling model for outcome prediction in DLBCL identified PKCβ as a marker that distinguishes fatal/refractory cases from those likely to be curable, and associated elevated PKCβ expression with negative clinical outcome [34]. Since that report, others have demonstrated the prognostic significance of PKCβ in DLBCL, and have linked its expression to lower complete remission rate, lower 5-year event-free survival and shortened overall survival [11, 16, 36-39]. Clinical trials currently underway to examine PKCβ inhibition as a targeted therapy for the treatment of DLBCL and other hematological malignancies have shown promise, linking PKCβ inhibition with prolonged freedom from disease progression in some patients [2, 16, 37, 40, 41]. Recent studies from our laboratory demonstrate the sensitivity of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) cells to PKCβ inhibition, an indication that PKCβ targeting should be considered as a potential treatment option in that disease as well [42]. The results of these and other studies indicate that PKCβ plays a major role in the growth and survival of malignant B-cells, and suggest that the pharmacological inhibition of PKCβ may be useful in the treatment of AIDS-NHL.

The drug candidate most frequently used to inhibit PKCβ in clinical and preclinical studies to date is Enzastaurin (LY317615.HCl), an acyclic bisindolylmaleimide that is orally administered and selectively inhibits PKCβ by competing with ATP at the enzyme's nucleotide triphosphate binding site, thereby blocking its activation. Preclinical studies have shown that Enzastaurin induces apoptosis and suppresses proliferation in many cancer cell lines in the micromolar range, comparable to the concentration range that can be achieved in the plasma of clinical trial subjects [37]. Among B-cell malignancies, for example, Enzastaurin inhibited the growth of CLL cells with an IC50 between 10 μM and 25 μM [29], and inhibited multiple myeloma cells with an IC50 between 1.3 μM and 12 μM (IC50 = half-maximal inhibitory concentration) [43]. Other molecules with similar activity and selectivity are available for use in preclinical studies, including the PKCβ inhibitor used in our recent study of B-ALL [42] and in the present work. While PKCβ inhibition is under active study as a targeted therapeutic for several leukemias and lymphomas, its utility in the treatment of AIDS-NHL has not been examined, and HIV infection has been considered an exclusion criterion in clinical studies involving PKCβ inhibition in NHL patients [40, 41]. Thus, the present study was undertaken to examine the effect of a PKCβ-selective inhibitor on the growth and survival of AIDS-NHL cell lines representing several morphologic types across the spectrum of disease. The results reveal both sensitivity and resistance to PKCβ inhibition among the cell lines examined, and implicate apoptotic induction and cell cycle inhibition as the operative mechanisms in sensitive cells.

Methods

Cell lines and reagents

The protein kinase C beta (PKCβ)-selective inhibitor, 3-(1-(3-Imidazol-1-ylpropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-anilino-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione (EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA) was suspended in DMSO at 6 mM concentration and stored in volumes of 10μl at -20°C. The 2F7, BCBL-1 and UMCL01-101 cell lines were obtained from the AIDS and Cancer Specimen Resource at the University of California, San Francisco. 2F7 and BCBL-1 were characterized by the AIDS and Cancer Specimen Resource, but have not been further authenticated in our laboratory. UMCL01-101 was obtained as early passage material and is thus not subject to authentication. 2F7 was cultured in suspension in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM GlutaMAX-I, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 10 μg/ml gentamicin. UMCL01-101 and BCBL-1 were maintained similarly but without sodium pyruvate. All cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37° C and were subcultured twice weekly.

Cell Viability Assay

To quantify cell viability using the MTS tetrazolium dye reduction assay, cells were deposited in triplicate wells of a 96-well flat bottom plate at 20,000 cells per well in a volume of 100μl. The PKCβ-selective inhibitor was added to a concentration of 5, 10, 20 or 30 μM, and incubated for 24, 48 or 72 hours. At each interval, 20 μl of the CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) was added directly to the wells and incubated for 1 to 4 hours at room temperature. The absorbance at 490 nm (A490) of each sample well was measured using an automated 96-well plate reader. The entire experiment was repeated at least four times. The results were analyzed statistically using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. Statistical significance was considered as p < 0.05.

Western Blot analysis

Protein was isolated from cells using RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% IGEPAL® CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) (Pierce Biotechnology; Rockford, Illinois) with protease inhibitor S8820 SIGMAFAST™ Protease Inhibitor Tablets (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Lysates were subjected to a freeze/thaw cycle at –80°C then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 minutes to sediment the particulate material. Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford Assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Total cellular protein was separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrotransferred onto Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membrane. After protein transfer, membranes were blocked with 5% non fat dry milk in TBS-T (TBS with 0.1% Tween 20) for at least 1 hour, then washed with TBS-T and subsequently incubated with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies included anti-PKCβ1 (C-16; sc-209; 1:200 dilution), PKCβ2 (F-7; sc-13149; 1:200 dilution), β-Actin (C4; sc-47778; 1:10,000 dilution) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-PKCβ1&2(threonine500) (1:1000 dilution; Millipore, Billerica, MA), AKT (C67E7; 1:1000 dilution), phospho-AKT(serine 473)(587F11, 1:1000 dilution), phospho-AKT(threonine 308) (244F9; 1:1000 dilution), GSK3β (27C1; 1:1000 dilution), phospho- GSK3β(serine9)(1:1000 dilution), S6 (54D2; 1:1000 dilution), phospho-S6(serine240/244) (2215; 1:1000 dilution), mTOR (7C10; 1:1000 dilution), and phospho-mTOR(serine2448) (D9C2; 1:1000 dilution) (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). Blots were washed with TBS-T and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with goat anti-mouse IgG or goat anti-rabbit IgG tagged with horseradish peroxidase (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The signal was visualized using Super Signal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate for PKCβ1 and PKCβ2, phospho-PKCβ1&2(threonine500), AKT, phospho-AKT(serine 473), phospho-AKT(threonine 308), GSK3β, phospho- GSK3β(serine9), S6, phospho-S6(serine240/244), mTOR, and phospho-mTOR(serine2448), and Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate for β-Actin (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

Flow cytometry

Cells were deposited in 60-mm dishes at a concentration of 3 × 105 cells/dish in 2 ml volume and were incubated with the correspondent IC50 of PKCβ-selective inhibitor for 2, 4, 8, 16, 24 and 48 hours. The APO-DIRECT™ assay kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was used to detect apoptotic activity and cell cycle using the deoxynucleotidyltransferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) method and propidium iodide (PI) staining, respectively. Cells were suspended in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml, placed on ice for 60 minutes, centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C, washed twice in PBS, then resuspended in 70% ice cold ethanol and maintained at -20°C for 12 – 72 hours. Cells were then washed twice with 1 ml of Wash Buffer, resuspended in 50 μL of DNA Labeling Solution, and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. At the end of the incubation time, cells were rinsed twice with 1 ml of Rinse Buffer, resuspended in 0.5 ml of the PI/RNase Staining Buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature, and then analyzed by flow cytometry within 3 hours of staining. Flow cytometry was performed using a BD FACSCaliburTM system (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) with BD CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) for data analysis. The results were analyzed statistically using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. Statistical significance was considered as p < 0.05.

Results

AIDS-NHL cell lines express at least one PKCβ isoform

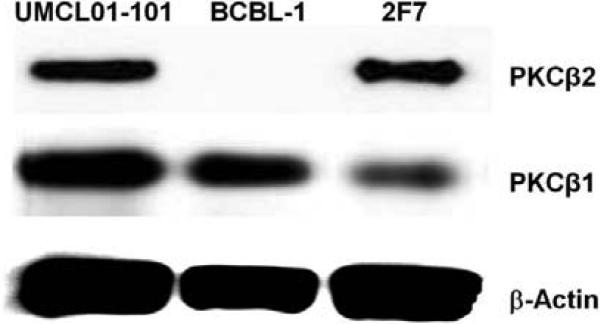

The expression of PKCβ isoforms was examined in three AIDS-NHL-derived cell lines representing distinct morphologic types of lymphoma: (1) 2F7, an EBV-positive B-cell line established by single cell cloning from biopsy material of an AIDS-related Burkitt lymphoma (AIDS-BL) [44], (2) BCBL-1, a KSHV-positive, EBV-negative B-cell line derived from an AIDS-related primary effusion lymphoma (AIDS-PEL) [45], and (3) UMCL01-101, recently derived from an uncharacterized AIDS-NHL and obtained as early passage material. We recently characterized UMCL01-101 as immunoblastic AIDS-DLBCL (AIDS-IBL) based on expression of the EBV-encoded oncogenes LMP-1 and EBNA2 and the absence of detectable BCL-6 [46]. Immunoblot analysis of total cellular protein demonstrated that 2F7 and UMCL01-101 cells express both PKCβ1 and PKCβ2. In contrast, BCBL–1 cells lack PKCβ2 expression and express only PKCβ1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Immunoblot analysis of PKCβ1 and PKCβ2 expression in UMCL01-101, BCBL-1 and 2F7 cell lines.

Total cellular protein (100 μg) from each cell line was examined first using monoclonal antibody for PKCβ2. The signal was then stripped, followed by analysis with monoclonal antibody for PKCβ1. The expression of β-Actin was examined as a loading control.

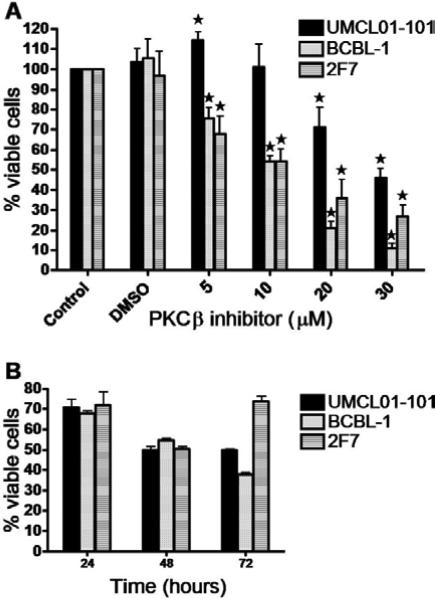

PKCβ-selective inhibition suppresses tumor cell proliferation in a time- and dose- dependent manner

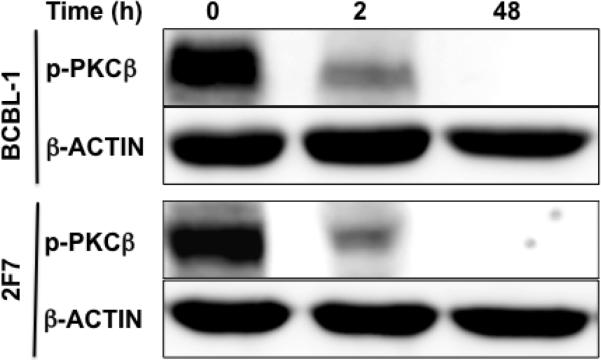

To examine the effect of PKCβ inhibition on the growth and viability of AIDS-NHL cells, the cell lines of interest were treated with the PKCβ-selective inhibitor, 3-(1-(3-Imidazol-1-ylpropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-anilino-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione. This compound is an anilino-monoindolylmaleimide that acts as a selective and potent inhibitor of PKCβ (IC50 = 5 nM and 21 nM when tested on purified human PKCβ2 and PKCβ1, respectively). The compound selectively inhibits PKCβ among PKC isoforms (IC50 for purified PKCα, γ, and ε = 331 nM, > 1 μM, and 2.8 μM, respectively). The reported mechanism of action of the compound is by competitive inhibition of PKCβ at the ATP binding site [47]. The response of 2F7, BCBL-1 and UMCL01-101 cells to the PKCβ-selective inhibitor was measured after 48 hours of treatment at inhibitor concentrations of 0, 5, 10, 20 and 30 μM. A tetrazolium dye reduction assay was then performed to quantify cell viability. The results demonstrated a dose-dependent reduction in viability of 2F7 and BCBL-1 cells starting at 5 μM and increasing with elevated inhibitor concentration. At 5 μM inhibitor, 2F7 and BCBL-1 cells demonstrated 38% and 28% reduction in viability, respectively. In contrast, UMCL01-101 cells demonstrated relative resistance, and indeed, were apparently stimulated by PKCβ inhibitor at 5 μM. Significant inhibition was evident only at 20 μM inhibitor concentration and higher (Figure 2A). To determine the respective IC50 values, each cell line was cultured in the presence of inhibitor increasing in 1 μM increments for 48 hours. The results demonstrated IC50 values of 14 μM, 15 μM and 28 μM for 2F7, BCBL-1 and UMCL01-101, respectively (data not shown). While the IC50 when tested on purified PKCβ is in the nanomolar range as described above, the IC50 for PKCβ inhibitors tested on intact cells has been routinely measured in the micromolar range, for example, in head and neck squamous carcinoma cells (IC50 = 3 – 10 μM), in CLL cells (IC50 = 10 – 25 μM) and in multiple myeloma cells (IC50 = 1.3 – 12 μM) [27, 29, 43]. To examine the time-dependence of inhibition, cells were treated at the correspondent IC50 for 24, 48 and 72 hours. The results demonstrated optimal inhibition of UMCL01-101 at 48 hours of treatment at the IC50. Of note, 2F7 cells were observed to be recovering, but inhibition of BCBL-1 continued through 72 hours of treatment (Figure 2B). Analysis of expression of phospho-PKCβ in BCBL-1 and 2F7 cells after treatment with inhibitor at the IC50 demonstrated a rapid and sustained reduction, indicating that the inhibitor acts as predicted [47] by direct action on the target through the inhibition of PKCβ phosphorylation (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Reduction in viability of AIDS-NHL cell lines following PKCβ-selective inhibition.

(A) UMCL01-101, BCBL-1 and 2F7 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of PKCβ-selective inhibitor (0 – 30 μM) for 48 hours, or were treated with the concentration of DMSO vehicle corresponding to the amount present in each dilution of inhibitor stock. Cell viability was quantified using a tetrazolium dye reduction assay. Data are expressed as percentage of the corresponding DMSO-treated control. Shown are data from untreated cells (Control), from cells treated with DMSO concentration equivalent to 30 μM inhibitor (DMSO), and from treatment with inhibitor at 5 – 30 μM. Error bars represent standard deviation. The asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) as compared to the respective DMSO-treated control. (B) UMCL01-101, BCBL-1 and 2F7 cells were incubated with correspondent IC50 of PKCβ-selective inhibitor for 24, 48 or 72 hours. Cell viability was quantified using a tetrazolium dye reduction assay, and data are expressed as percentage of control cells treated with DMSO only.

Figure 3. Immunoblot analysis of phospho-PKCβ expression in BCBL-1 and 2F7 cell lines.

BCBL-1 and 2F7 cells were treated with PKCβ-selective inhibitor at the IC50 (15 μM or 14 μM, respectively) for 2 – 48 hours. Total cellular protein (50 μg) collected at regular intervals was examined using affinity-purified polyclonal antibody for phospho-PKCβ1&2(threonine500). The expression of β-Actin was examined as a loading control.

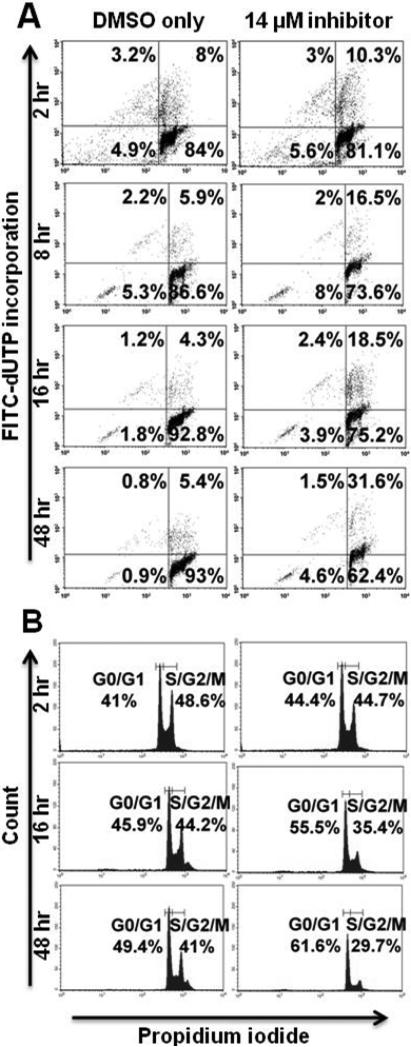

PKCβ-selective inhibition induces apoptosis in AIDS-NHL cell lines

To determine whether treatment with PKCβ inhibition diminishes AIDS-NHL cell viability by inducing apoptosis as it does in other systems examined [16, 21, 31, 33, 37, 48], AIDS-NHL cell lines were treated with inhibitor at the correspondent IC50, or with the correspondent DMSO concentration, for 2, 4, 8, 16, 24 and 48 hours. Apoptotic induction was quantified at each interval using the flow cytometric TdT-mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) assay. The results demonstrated apoptotic induction in 2.1% of 2F7 cells above background after two hours of treatment, increasing through 48 hours of treatment when 26.9% of cells were apoptotic above background (Figure 4A). BCBL-1 cells were more sensitive to apoptotic induction by PKCβ inhibition, showing 9% apoptotic cells above background after two hours of treatment. The effect increased in BCBL-1 cells through 48 hours of treatment when 65.4% of cells were apoptotic above background (Figure 5A). UMCL01-101 cells demonstrated relative resistance to apoptotic induction, showing few or no apoptotic cells even after 48 hours of treatment at a concentration of inhibitor comparable to that used for 2F7 and BCBL-1 cells (14 μM; Figure 6A). When UMCL01-101 cells were treated with 28 μM inhibitor, apoptotic induction was evident after two hours of treatment, increasing through 48 hours when 75.9% of cells were apoptotic above background (Figure 7A).

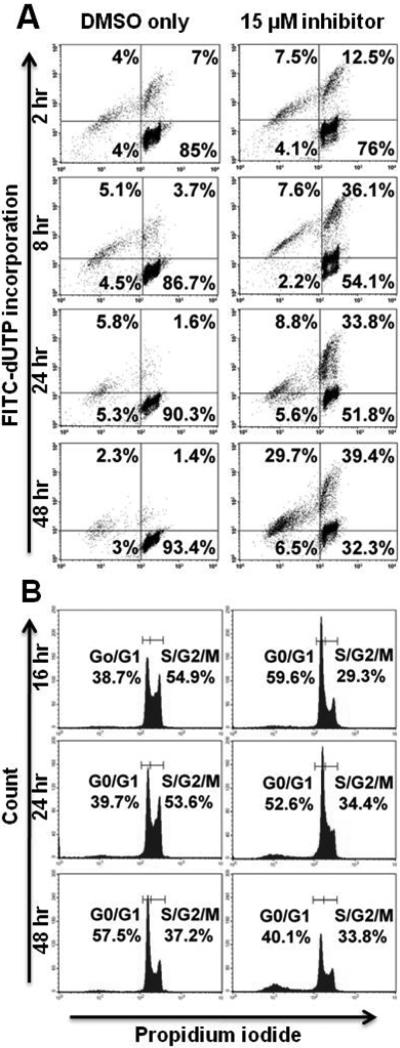

Figure 4. PKCβ-selective inhibition induces apoptosis and inhibits cell cycle progression in 2F7 cells.

2F7 cells were treated with PKCβ-selective inhibitor at the IC50 (14 μM), or with the correspondent concentration of DMSO, for 2 – 48 hours. (A) Cells were examined at regular intervals for apoptosis using a flow cytometric TUNEL assay in which apoptotic cells are demonstrated in the right and left upper quadrants. (B) Cell cycle analysis was performed at regular intervals using propidium iodide staining. Representative histograms are shown.

Figure 5. PKCβ-selective inhibition induces apoptosis and transiently inhibits cell cycle progression in BCBL-1 cells.

BCBL-1 cells were treated with PKCβ-selective inhibitor at the IC50 (15 μM), or with the correspondent concentration of DMSO, for 2 – 48 hours. Analyses of apoptosis (A) and cell cycle progression (B) were performed as described for Figure 4.

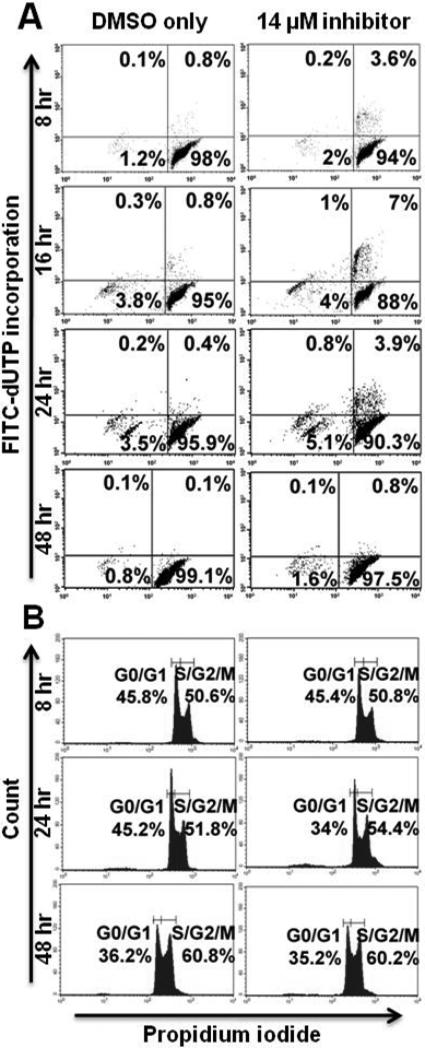

Figure 6. Relative resistance of UMCL01-101 cells to apoptotic induction or cell cycle inhibition by PKCβ-selective inhibition.

UMCL01-101 cells were treated with PKCβ-selective inhibitor at a concentration comparable to the IC50 for 2F7 or BCBL-1 cells (14 μM), or with the correspondent concentration of DMSO, for 2 – 48 hours. Analyses of apoptosis (A) and cell cycle progression (B) were performed as described for Figure 4.

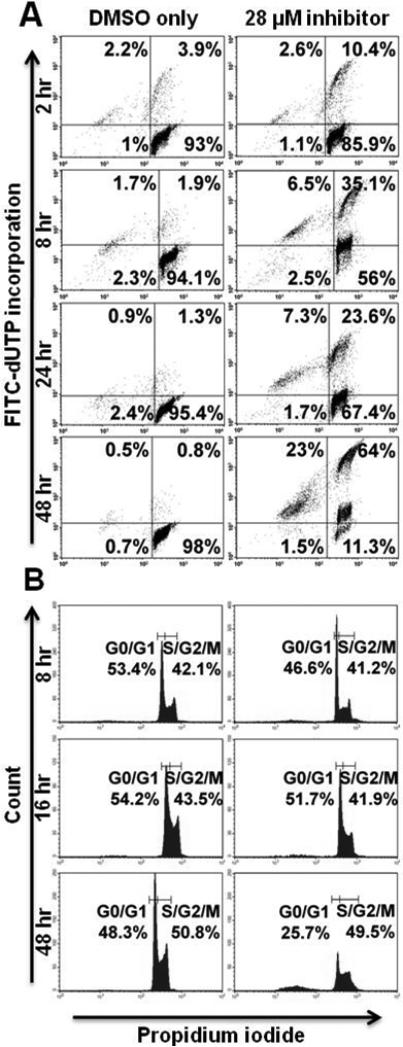

Figure 7. PKCβ-selective inhibition at high concentration induces apoptosis but does not inhibit cell cycle progression in UMCL01-101 cells.

UMCL01-101 cells were treated with PKCβ-selective inhibitor at the IC50 (28 μM), or with the correspondent concentration of DMSO, for 2 – 48 hours. Analyses of apoptosis (A) and cell cycle progression (B) were performed as described for Figure 4.

PKCβ-selective inhibition inhibits cell cycle progression in 2F7 and BCBL-1 cells but not in UMCL01-101 cells

TUNEL analysis of 2F7 cells demonstrated modest apoptotic induction after PKCβ inhibition, but perhaps insufficient to account for the full effect on cell viability. Thus, flow cytometric cell cycle analysis was performed using propidium iodide staining to assess the effect of PKCβ inhibition on cell cycle progression. The results showed that, in 2F7 cells treated for 48 hours with inhibitor at 14 μM, 29.7% of cells were in the S/G2/M fraction as compared to 41% of control cells treated with vehicle alone (Figure 4B). BCBL-1 cells were similarly, although more rapidly affected by PKCβ inhibition. After 16 hours of treatment at 15 μM, 29.3% of cells were in the S/G2/M fraction as compared to 54.9% of control cells treated with vehicle alone. By 48 hours of treatment, cell cycle inhibition was no longer apparent in BCBL-1 cells; rather, the relatively high levels of apoptosis may represent the chief mechanism of inhibition after extended treatment (Figure 5B). In contrast, PKCβ inhibition had no cell cycle inhibitory effect on UMCL01-101 cells treated at 14 μM or 28 μM of inhibitor (Figures 6B and 7B).

Selective PKCβ inhibition does not affect AKT activation but decreases phosphorylation of GSK3β, ribosomal protein S6 and mTOR in AIDS-NHL cells

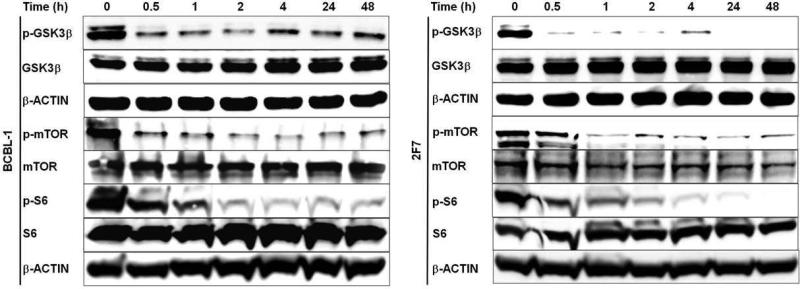

PKCβ is known to activate the pro-survival signalling protein, AKT, by phosphorylation at residues serine 473 and threonine 308 [49, 50]. However, treatment of BCBL-1 and 2F7 cells with PKCβ-selective inhibitor at the correspondent IC50 was observed to have no effect on AKTser473 or AKTthr308 phosphorylation (data not shown). By contrast, PKCβ-selective inhibition dramatically reduced phosphorylation of GSK3β, a serine-threonine kinase originally identified for its role in glycogen metabolism but subsequently implicated in diverse cellular processes including proapoptotic signalling. The proapoptotic activity of GSK3β is inhibited by phosphorylation. GSK3β is a known phosphorylation target of AKT, but may also be phosphorylated directly by PKCβ1 or PKCβ2 [51, 52]. Treatment of BCBL-1 and 2F7 cells with PKCβ-selective inhibitor at the correspondent IC50 resulted in strongly diminished GSK3βser9 phosphorylation, evident after 30 minutes of treatment and continuing through the 48 hour examination period. Total GSK3β levels were not affected (Figure 8). Other known downstream targets of PKCβ2 include mTOR and P70S6K, whose phosphorylation mediated directly or indirectly by PKCβ2 is predicted to lead to tumor cell proliferation and suppression of apoptosis [1, 11, 12]. Treatment of BCBL-1 and 2F7 cells with PKCβ-selective inhibitor at the correspondent IC50 resulted in a sharp decline in mTORser2448 phosphorylation evident between 0.5 – 1 hour of treatment and levels remained low throughout the 48 hour examination period. Phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6(serine240/244), examined as a marker of P70S6K activity, was observed to decline gradually through the first hour of treatment and to remain at low or undetectable levels throughout the 48 hour examination period (Figure 8).

Figure 8. PKCβ-selective inhibition suppresses GSK3β, mTOR and S6 phosphorylation.

BCBL-1 and 2F7 cells were treated with correspondent IC50 of the PKCβ-selective inhibitor, or with DMSO only, for the time periods shown. Immunoblot analyses were performed on total protein (50 μg) from cells collected at each time interval, using antibodies specific for p-GSK3β(serine9), p-mTOR(serine2448), p-S6(serine240/244), and total GSK3β, m-TOR, and S6. The expression of β-Actin was examined as a loading control.

Discussion

PKCβ is considered a potential target for the treatment of many cancers, including leukemia and lymphoma, because of its central role in signaling pathways that affect cell survival, apoptosis and proliferation [1, 3, 11]. In ongoing clinical trials involving PKCβ inhibition in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, HIV infection has generally been considered an exclusion criterion for enrollment [16, 37, 41]; thus, studies describing the possible utility of PKCβ as a therapeutic target in AIDS-NHL are lacking. The present study was undertaken to evaluate the role of PKCβ in AIDS-NHL cells and the therapeutic potential of its inhibition. The several PKCβ inhibitors available for preclinical research differ by their selectivity among the PKC isoenzymes and the correspondent IC50 [47]. The commercially available inhibitor used in the present study is highly selective for PKCβ2 among PKC isoenzymes, with an IC50 for PKCβ2 comparable to that of Enzastaurin, and demonstrates significant selectivity for PKCβ1 as well [37, 47]. Thus, although Enzastaurin was not available to us for use in the present study, the commercially available compound demonstrated comparable properties. The cytotoxic and antiproliferative effects of this PKCβ-selective inhibitor were therefore examined in three AIDS-NHL cell lines: 2F7, an EBV-positive AIDS-BL; BCBL-1, a KSHV-positive, EBV-negative AIDS-PEL; and UMCL01-101, an EBV-positive AIDS-DLBCL of immunoblastic phenotype (AIDS-IBL). We had previously examined the growth regulation of these cell lines, demonstrating variable sensitivity to TGF-β1-mediated growth inhibition, and rescue by IL-6 even in the presence of TGF-β1 [46]. Results of the present study showed that 2F7 and UMCL01-101 cells express both PKCβ1 and PKCβ2 (Figure 1), and thus might be expected to be sensitive to PKCβ inhibition. As predicted, 2F7 cells demonstrated sensitivity to PKCβ-selective inhibition with 38% reduction in viability at 5 μM inhibitor concentration and an IC50 of 14 μM. By comparison, Enzastaurin has been shown to inhibit solid tumors as well as B-cell malignancies in vitro with comparable IC50 in the micromolar range [27, 29, 43]. In contrast, UMCL01-101 cells demonstrated relative resistance to PKCβ-selective inhibition with an IC50 measured at 28 μM. A statistically significant growth stimulation was observed at 5μM inhibitor concentration, and no significant reduction of viability was observed at inhibitor concentrations lower than 20 μM (Figure 2A). The relative resistance of UMCL01-101 was unexpected as PKCβ-expressing DLBCL in the general population is thought to be sensitive to PKCβ inhibition and a rational subject for clinical trials [16, 37]. While the factors that determine sensitivity or resistance to Enzastaurin are poorly understood, others have observed variable sensitivity among tumor cell lines of the same type. In colon cancer, for example, resistance to Enzastaurin has been associated with the presence of the oncogenic K-Ras mutation and expression of mesenchymal cell markers, while sensitive cells typically display wild-type K-Ras and express high levels of epithelial cell markers [53]. In the case of UMCL01-101 cells, relative resistance may be related to expression of the EBV-encoded latent membrane protein-1 (LMP-1) which can activate PKCβ [54]. BCBL-1 cells were observed in the present study to express PKCβ1 alone, in the absence of PKCβ2 (Figure 1). The sensitivity of cells to PKCβ1-selective inhibition has not previously been examined, and was not predictable considering the broad spectrum of opposing influences attributed to PKCβ1 [12, 17-19]. The results reveal the sensitivity of BCBL-1 cells to the inhibitor with 28% reduction in viability at 5 μM inhibitor concentration and an IC50 of 15 μM. The findings implicate PKCβ1 as a key regulator in BCBL-1 cells, and further suggest that improved outcome could be expected by using a PKCβ inhibitor with increased selectivity for PKCβ1.

Flow cytometric TUNEL assay demonstrated significant apoptotic induction in sensitive cells, particularly in BCBL-1 in which the majority of cells were apoptotic after 48 hours of treatment (Figure 5A). 2F7 cells demonstrated a more modest apoptotic response, with 26.9% of cells apoptotic above background after 48 hours of treatment (Figure 4A). By comparison, in a recent study of cell lines from follicular lymphoma and other subsets of indolent lymphoma, apoptosis levels up to 59% were observed at treatment with Enzastaurin at the IC50 for 72 hours [28]. UMCL01-101 cells demonstrated relative resistance, as evidenced by their lack of apoptotic response to a concentration of inhibitor comparable to that used for 2F7 and BCBL-1 cells (14 μM; Figure 6A). Only when UMCL01-101 cells were treated with a high concentration of inhibitor (28 μM) was an apoptotic response evident (Figure 7A). PKCβ inhibition also inhibited cell cycle progression, particularly in 2F7 and BCBL-1 cells. A significant reduction of the S/G2/M fraction was evident in both cell lines after treatment for 48 hours, although BCBL-1 cells were more rapidly affected (Figures 4B and 5B). It was noteworthy cell cycle progression in UMCL01-101 cells was not inhibited at any concentration of inhibitor tested (Figures 6B and 7B). Comparable studies using Enzastaurin as a PKCβ inhibitor in vitro have generally not demonstrated an inhibition of cell cycle progression [48], although recent findings suggest that it may occur under some circumstances, e.g., in renal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, and in multiple myeloma cell lines [26, 32, 55].

The treatment of sensitive AIDS-NHL cell lines with PKCβ-selective inhibitor had no effect on AKT phosphorylation (data not shown), unlike the response in some other malignant B-cells including follicular lymphoma and B-ALL [28, 42]. In contrast, PKCβ-selective inhibition induced a rapid and dramatic decrease in GSK3β phosphorylation in BCBL-1 and 2F7 cells, starting after 30 minutes of treatment and continuing for at least 48 hours (Figure 8). Although GSK3β is identified as a phosphorylation target of AKT, the diminished GSK3β phosphorylation is unlikely to be attributed to reduced AKT activity in this case, since PKCβ inhibition was observed to have no effect on AKT phosphorylation. Rather, since both PKCβ1 and PKCβ2 are reported to phosphorylate GSK3β directly [51, 52], the observed loss of GSK3β phosphorylation can be explained by a direct effect of the inhibitor on PKCβ. The diminished phosphorylation of GSK3β is known to stimulate its proapoptotic influence [56]; thus the observed reduction in phosphorylation upon PKCβ inhibition may account for the subsequent apoptotic induction. Other reports demonstrate a strong dephosphorylation of GSK3β following treatment with a PKCβ inhibitor in glioma cell lines, squamous cell carcinoma, colon cancer, prostate cancer, follicular lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells, and in our recent study of B-ALL cells [22, 27, 31, 33, 42, 43, 57, 58]. In the latter case, strongly diminished GSK3β phosphorylation was similarly observed after 30 minutes of PKCβ inhibition and persisted for at least 48 hours [42]. Similarly, the phosphorylation of other known targets of PKCβ was observed to decline in a rapid and sustained manner after PKCβ inhibition, including mTOR and ribosomal protein S6, the latter examined as a marker for P70S6K activity (Figure 8). mTOR is thought to function as a master regulator of cellular metabolism, cell growth and proliferation at the level of both gene transcription and protein translation. Similar to the results observed here, treatment with a PKCβ inhibitor was shown to reduce phosphorylation of mTOR in sensitive glioma cells and in follicular lymphoma and other subsets of indolent lymphoma [22, 28]. PKCβ-dependent phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein S6 kinase P70S6K promotes cell survival through phosphorylation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member, Bad, thus blocking its ability to antagonize the provsurvival function of other Bcl-2 family members. In cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and colon cancer cells, PKCβ inhibition decreased the ser240/244 phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 (a marker for the activity of its kinase) within two hours of treatment [31, 58], and after a slightly longer delay in glioma cell lines [22].

Taken together, the results presented here indicate that PKCβ-selective inhibition reduces viability of some AIDS-NHL cell lines through an apparent stimulation of the proapoptotic influence of GSK3β, suppression of the growth and prosurvival influences of mTOR and P70S6K, and by inducing cell cycle arrest. These findings indicate that PKCβ targeting may be useful in the treatment of AIDS-NHL, but that detailed analysis is required to uncover the mechanisms for sensitivity or resistance of particular tumor cell types. The studies indicate that both AIDS-BL and AIDS-PEL are responsive to PKCβ-targeted therapy, neither of which has been previously examined. The mechanisms of responsiveness include both apoptotic induction and cell cycle inhibition, through direct effect on phosphorylation of GSK3β, mTOR and P70S6K. The sensitivity of BCBL-1 was unexpected in the absence of PKCβ2 expression and implicates PKCβ1 as a key regulator in those cells. By contrast, UMCL01–101 cells demonstrated relative resistance to PKCβ inhibition, an unexpected finding since UMCL01-101 cells express both PKCβ1 and PKCβ2, and since PKCβ-expressing DLBCL in the general population is thought to be sensitive to PKCβ inhibition [16, 37]. Future studies to verify and extend these findings will be directed at patient samples, and in exploring the potential role of both PKCβ1 and PKCβ2 isoforms in responding to the inhibitor. It is expected from these studies to expand our understanding of the molecular basis for sensitivity and resistance to PKCβ inhibition in AIDS-NHL cells, and thereby increase the potential for PKCβ inhibition as a therapeutic option for that disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the support and mentorship of Drs. Hana Safah and Roy S. Weiner. The authors acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Adriana Zapata. The AIDS and Cancer Specimen Resource is gratefully acknowledged for the provision of AIDS-NHL-derived cell lines. This work was supported by grants to L.S. L. from the National Cancer Institute, NIH (R01 CA74731), the When Everyone Survives Foundation and the Ladies Leukemia League, Inc., of the Gulf South Region.

Sources of support: This work was supported by grants to L.S. L. from the National Cancer Institute, NIH (R01 CA74731), the When Everyone Survives Foundation and the Ladies Leukemia League, Inc., of the Gulf South Region.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Faivre S, Djelloul S, Raymond E. New paradigms in anticancer therapy: targeting multiple signaling pathways with kinase inhibitors. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:407–420. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonard JP, Martin P, Barrientos J, et al. Targeted treatment and new agents in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 2008;45:S11–16. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serova M, Ghoul A, Benhadji KA, et al. Preclinical and clinical development of novel agents that target the protein kinase C family. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:466–478. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood C, Harrington W., Jr AIDS and associated malignancies. Cell Res. 2005;15:947–952. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoki Y, Tosato G. Neoplastic conditions in the context of HIV-1 infection. Curr HIV Res. 2004;2:343–349. doi: 10.2174/1570162043351002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgi A, Brodine S, Wegner S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for the occurrence of non-AIDS-defining cancers among human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Cancer. 2005;104:1505–1511. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krause J. AIDS-related non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Microsc Res Tech. 2005;68:168–175. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carbone A, Cesarman E, Spina M, et al. HIV-associated lymphomas and gamma-herpesviruses. Blood. 2009;113:1213–1224. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-180315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbone A, Gloghini A. AIDS-related lymphomas: from pathogenesis to pathology. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:662–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellan C, Lazzi S, De Falco G, et al. Burkitt's lymphoma: new insights into molecular pathogenesis. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:188–192. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martiny-Baron G, Fabbro D. Classical PKC isoforms in cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reyland ME. Protein Kinase C and Apoptosis. In: Srivastava R, editor. Apoptosis, Cell Signaling and Human Disease. Humana Press, Inc; Totowa, NJ: 2007. pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo B, Su TT, Rawlings DJ. Protein kinase C family functions in B-cell activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shinohara H, Maeda S, Watarai H, et al. IkappaB kinase beta-induced phosphorylation of CARMA1 contributes to CARMA1 Bcl10 MALT1 complex formation in B cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3285–3293. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su TT, Guo B, Kawakami Y, et al. PKC-beta controls I kappa B kinase lipid raft recruitment and activation in response to BCR signaling. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:780–786. doi: 10.1038/ni823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YB, LaCasce AS. Enzastaurin. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:939–944. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.6.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deacon EM, Pongracz J, Griffiths G, et al. Isoenzymes of protein kinase C: differential involvement in apoptosis and pathogenesis. Mol Pathol. 1997;50:124–131. doi: 10.1136/mp.50.3.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi PM, Tchou-Wong KM, Weinstein IB. Overexpression of protein kinase C in HT29 colon cancer cells causes growth inhibition and tumor suppression. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4650–4657. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.9.4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang XH, Tu SP, Cui JT, et al. Antisense targeting protein kinase C alpha and beta1 inhibits gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5787–5794. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butowski N, Chang SM, Lamborn KR, et al. Enzastaurin plus temozolomide with radiation therapy in glioblastoma multiforme: a phase I study. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:608–613. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jian W, Yamashita H, Levitt JM, et al. Enzastaurin shows preclinical antitumor activity against human transitional cell carcinoma and enhances the activity of gemcitabine. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1772–1778. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rieger J, Lemke D, Maurer G, et al. Enzastaurin-induced apoptosis in glioma cells is caspase-dependent and inhibited by BCL-XL. J Neurochem. 2008;106:2436–2448. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spindler KL, Lindebjerg J, Lahn M, et al. Protein kinase C-beta II (PKC-beta II) expression in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:641–645. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanai C, Yamamoto N, Ohe Y, et al. A phase I study of enzastaurin combined with pemetrexed in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1068–1074. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181da3899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tekle C, Giovannetti E, Sigmond J, et al. Molecular pathways involved in the synergistic interaction of the PKC beta inhibitor enzastaurin with the antifolate pemetrexed in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:750–759. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogl UM, Berger W, Micksche M, et al. Synergistic effect of Sorafenib and Sunitinib with Enzastaurin, a selective protein kinase C inhibitor in renal cell carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2009;277:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin X, Hayes DN, Shores CG. Antitumor activity of enzastaurin as radiation sensitizer in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2010 doi: 10.1002/hed.21578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Civallero M, Cosenza M, Grisendi G, et al. Effects of enzastaurin, alone or in combination, on signaling pathway controlling growth and survival of B-cell lymphoma cell lines. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:671–679. doi: 10.3109/10428191003637290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holler C, Pinon JD, Denk U, et al. PKCbeta is essential for the development of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the TCL1 transgenic mouse model: validation of PKCbeta as a therapeutic target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:2791–2794. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-160713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu D, Zhao Y, Tawatao R, et al. Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3118–3123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308648100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Querfeld C, Rizvi MA, Kuzel TM, et al. The selective protein kinase C beta inhibitor enzastaurin induces apoptosis in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cell lines through the AKT pathway. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1641–1647. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raab MS, Breitkreutz I, Tonon G, et al. Targeting PKC: a novel role for beta-catenin in ER stress and apoptotic signaling. Blood. 2009;113:1513–1521. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rizvi MA, Ghias K, Davies KM, et al. Enzastaurin (LY317615), a protein kinase Cbeta inhibitor, inhibits the AKT pathway and induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1783–1789. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shipp MA, Ross KN, Tamayo P, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction by gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2002;8:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verdelli D, Nobili L, Todoerti K, et al. Molecular targeting of the PKC-beta inhibitor enzastaurin (LY317615) in multiple myeloma involves a coordinated downregulation of MYC and IRF4 expression. Hematol Oncol. 2009;27:23–30. doi: 10.1002/hon.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. Expression of PKC-beta or cyclin D2 predicts for inferior survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1377–1384. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma S, Rosen ST. Enzastaurin. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:590–595. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282f10a00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riihijarvi S, Koivula S, Nyman H, et al. Prognostic impact of protein kinase C beta II expression in R-CHOP-treated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:686–693. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaffel R, Morais JC, Biasoli I, et al. PKC-beta II expression has prognostic impact in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:326–330. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morschhauser F, Seymour JF, Kluin-Nelemans HC, et al. A phase II study of enzastaurin, a protein kinase C beta inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:247–253. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robertson MJ, Kahl BS, Vose JM, et al. Phase II study of enzastaurin, a protein kinase C beta inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1741–1746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saba NS, Levy LS. Apoptotic induction in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines treated with a protein kinase C inhibito. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:877–886. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.552136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neri A, Marmiroli S, Tassone P, et al. The oral protein-kinase C beta inhibitor enzastaurin (LY317615) suppresses signalling through the AKT pathway, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cell lines. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:1374–1383. doi: 10.1080/10428190802078289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng VL, Hurt MH, Fein CL, et al. IgMs produced by two acquired immune deficiency syndrome lymphoma cell lines: Ig binding specificity and VH-gene putative somatic mutation analysis. Blood. 1994;83:1067–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B, et al. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat Med. 1996;2:342–346. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruff KR, Puetter A, Levy LS. Growth regulation of simian and human AIDS-related non-Hodgkin's lymphoma cell lines by TGF-beta1 and IL-6. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka M, Sagawa S, Hoshi J, et al. Synthesis of anilino-monoindolylmaleimides as potent and selective PKCbeta inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:5171–5174. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee KW, Kim SG, Kim HP, et al. Enzastaurin, a protein kinase C beta inhibitor, suppresses signaling through the ribosomal S6 kinase and bad pathways and induces apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1916–1926. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alessi DR, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, et al. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephens L, Anderson K, Stokoe D, et al. Protein kinase B kinases that mediate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent activation of protein kinase B. Science. 1998;279:710–714. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fang X, Yu S, Tanyi JL, et al. Convergence of multiple signaling cascades at glycogen synthase kinase 3: Edg receptor-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation by lysophosphatidic acid through a protein kinase C-dependent intracellular pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2099–2110. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2099-2110.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serova M, Astorgues-Xerri L, Bieche I, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and oncogenic Ras expression in resistance to the protein kinase Cbeta inhibitor enzastaurin in colon cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1308–1317. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luo W, Yan G, Li L, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 mediates serine 25 phosphorylation and nuclear entry of annexin A2 via PI-PLC-PKCalpha/PKCbeta pathway. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47:934–946. doi: 10.1002/mc.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuo WL, Liu J, Mauceri H, et al. Efficacy of the multi-kinase inhibitor enzastaurin is dependent on cellular signaling context. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2814–2824. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim SG, Lee SJ. PI3K, RSK, and mTOR signal networks for the GST gene regulation. Toxicol Sci. 2007;96:206–213. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Civallero M, Cosenza M, Neri A, et al. Genomic profiling of enzastaurin-treated B cell lymphoma RL cells. Hematol Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/hon.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graff JR, McNulty AM, Hanna KR, et al. The protein kinase Cbeta-selective inhibitor, Enzastaurin (LY317615.HCl), suppresses signaling through the AKT pathway, induces apoptosis, and suppresses growth of human colon cancer and glioblastoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7462–7469. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]