Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among North Korean defectors and their level of suicidal ideation and the correlation between these and heart-rate variability (HRV) to explore the possibility of using HRV as an objective neurobiological index of signs of autonomic nervous system disorder.

Methods

A total of 32 North Korean defectors (nine men, 23 women) were selected as subjects, and their HRV was measured after they completed the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-PTSD (MMPI-PTSD) scale and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

Results

1) Low-frequency (LF)/high-frequency (HF) ratios in the HRV index and MMPI-PTSD scores were correlated (r=0.419, p<0.05), as were BDI item 9 (suicidal ideation) and MMPI-PTSD scores (r=0.600, p<0.01). 2) A regression analysis of LF/HF ratios and MMPI-PTSD scores revealed an R-value of 13.8% (Adj. R2=0.138, F=4.695, p=0.041), and a regression analysis of BDI item 9 and MMPI-PTSD scores showed an R-value of 32.8% (Adj. R2=0.328, F=11.234, p=0.003). In other words, the LF/HF ratio (β=0.419) and BDI item 9 (β=0.600) appear to be risk factors in predicting MMPI-PTSD scores.

Conclusion

The LF/HF ratio, a standard index of autonomic nervous system activity, can be used as an objective neurobiological index to analyze PTSD among North Korean defectors presenting with various mental and physical symptoms, and the approximate level of suicide -ideation can act as a predicting factor for PTSD.

Keywords: North Korean defectors, Post-traumatic stress disorder, Suicide, Heart rate variability, Depression

INTRODUCTION

As of December 2010, more than 20,000 people had defected from North Korea, many suffering from hunger and diseases almost to the point to death.1 The need for medical attention among North Korean defectors is expected to increase in the future, especially for mental health care, which plays a key role in successful adaptation.2 However, despite their different cultural background and the hardships they have experienced, few systematic studies have focused on mental health issues among defectors. The studies that have been done tend to simply investigate the present conditions in North Korea and the experiences of North Korean defectors instead of attempting to understand and solve the issues related to various mental difficulties. Many North Korean defectors experience various traumatic incidents: direct and indirect suppression of human rights, the escape process, hardships related to living in a third country, separation from family, death of family and friends, various physical diseases, and fear of being caught, captured, or being refused refugee status.3 These experiences are not isolated; they are generally very complicated and ongoing issues. Many defectors suffer from major mental diseases such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression.4 Defectors understandably find it difficult to go through the processes of settling in a new society, including dealing with economic hardship, severance of social relationships, and culture shock, especially when they have been living in a society that differs politically, economically, and socioculturally.5 Among North Korean defectors, secondary stress factors and a lack of emotional and social support can act as causal and aggravating factors of PTSD, which is related to the loss of constancy of psychological, biological, and social balance.

Many mental disorders, such as mood disorders and anxiety disorders, are closely related to physical symptoms.6 Historically, PTSD has been defined by focusing on physical symptoms such as 'soldier's heart' and 'railway spine.' This kind of definition implies that PTSD commonly involves various atypical physical symptoms. Traumatic experiences are related to stress reactions, which can cause various physical symptoms due to imbalances in the autonomic neuron system caused by overreaction of the sympathetic and suppression of the parasympathetic nervous system. Physical symptoms can also be the result of the direct and indirect physical traumas that caused PTSD. Finally, physical symptoms can be related to mentally coexisting diseases such as depression. One study reported that physical symptoms can be predictors of depression, and physical symptoms can similarly be linked to other coexisting diseases.7 Chronic physical symptoms lead to increased use of medical services and increased cost.8 Lange et al.9 reported that patients are frequently not diagnosed with PTSD because they do not voluntarily seek medical attention for their PTSD symptoms. On the other hand, many patients seek medical attention for physical symptoms even though these are actually rooted in PTSD. Nakell et al.10 reported that many patients are unaware of the association between their symptoms and the trauma they had experienced, even though they frequently seek help for physical symptoms after undergoing a severe trauma. These authors stressed the need for a specific medical interview to assess the possibility of PTSD among patients who have experienced a severe trauma and seek help for atypical physical symptoms. Depression is often linked with PTSD, and it increases the risk for suicide, so medical practitioners need to pursue this kind of evaluation more actively.11

Heart-rate variability (HRV) is an index that quantitatively demonstrates minute changes in heart rate during normal physiological processes of the autonomic nervous system.12 HRV is a simple and non-invasive method used to confirm a present health condition and psychophysiologically stable state.13 In a normal individual, the heart rate maintains a constant body environment by irregularly, minutely, and constantly changing according to interactions between the sympathetic nervous system, which is the basis of the autonomic nervous system, and the parasympathetic nervous system.12 Healthy individuals exhibit constant HRV, allowing them to be very sensitive to the environment inside and outside their body, including blood oxygen concentration, body temperature, and blood pressure, and to reach a physiological heart-rate balance in a short period of time.14 Decreased HRV can be an independent index related to the incidence of fatal heart attacks, such as is seen in ventricular fibrillation.15 Therefore, HRV may reveal signs of disorder in the autonomic nervous system and serve as an indicator of the level of reaction to stress.

This study evaluated PTSD symptoms among North Korean defectors along with their level of suicidal ideation and the correlation of both with HRV to assess the possibility of using HRV as an objective neurobiological index of signs of autonomic nervous system disorder and reactions to stress.

METHODS

Subjects

We assessed HRV and administered questionnaires to a sample of North Korean defectors who attended a free lecture about defectors and their mental health, which was hosted by our institution. We analyzed the results without any particular standard of exclusion. Prior to the study, we explained the purpose and methodology and received consent from all participants. We selected a total of 32 North Korean defectors (nine men, 23 women) and measured their HRV after they completed the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-PSTD (MMPI-PTSD) scale and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

Assessment measures

BDI

Depression levels were measured using the Korean version of the BDI, which was adapted by Lee and Song.16 This measurement is a self-reported questionnaire to evaluate the existence and level of depression, including cognitive, emotional, motivational, and physiological symptoms. To simply investigate the suicidal ideation of North Korean defectors, we selected and analyzed item number 9 from the BDI Test, which includes various types of depression symptoms. Responses on the BDI use a four-point scale, from mild (0) to severe (3), according to the level of symptoms reported for each question. On the BDI, scores lower than nine are classified as non-depression, 10-15 as mild depression, 16-23 as moderate depression, and 24-63 as severe depression. The internal inconsistency of this measure is α=0.91.16

MMPI-PTSD

The MMPI-PTSD was administered to help clarify PTSD symptoms. This measurement is a subordinate measurement of MMPI constructed by selecting 45 questions about PTSD symptoms from the MMPI questionnaire. Individuals who score higher than 17 points are more likely to be diagnosed with PTSD,17 so we used 17 points as the cutoff for PTSD.

HRV

The HRV examination was conducted by a medical worker in a quiet and calm environment. Before the examination, participants were asked to remove jewelry and cell phones. Sensors were attached, the procedure was explained, and participants were given at least 5 minutes to adjust to the environment so as to minimize any effects from short-term activity. Participants were asked to breathe evenly and lean back in a comfortable chair, to focus on a certain point on the wall without closing their eyes, and not to phonate in any way. After the medical worker checked the limb-lead conduction and confirmed that the graph was clear and had no interfering wavelength, HRV measurements were carried out for 5 minutes using an SA-2000E (Medicore, Seoul, Korea). Next, HRV results were assessed based on the widely used time-domain analysis and frequency-domain analysis. The standard deviation of the NN intervals is a comprehensive and universal index of HRV and is easily applied for experiments;18 it is widely used as an independent predicting factor of heart ischemia because it is highly sensitive, especially with regard to important heart diseases.19

Frequency-domain analysis can reveal how the frequency function is distributed.20 Frequency can be divided into three period components through power-spectrum analysis.21 The first component is the high-frequency component (HF component), which is an index of parasympathetic system functioning; it is associated with the breathing cycle, which is between 0.15 Hz and 0.4 Hz. The second component is the low-frequency component (LF component), between 0.05 Hz and 0.15 Hz. The LF component is associated with changes related to the pressure receptor and body temperature control; it is affected by both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, but mainly reflects the activity of the sympathetic nervous system.22 The third component is the very-low-frequency component (VLF component), between 0.005 Hz and 0.05 Hz. It can act as an additional index of parasympathetic nervous system activity, but it is widely known that to provide accurate results, this component must be measured for a minimum of 5 minutes.23 The LF/HF ratio is a general balance index used to assess the sympathetic activity of the heart or the sympathetic/parasympathetic nervous system balance. High ratios indicate heightened activity of the sympathetic or suppression of the parasympathetic nervous system.24 For the 5-minute measurement, normalized LF and normalized HF, the ratio of LF and HF excluding VLF, was used to compensate for the time limit, and the log value was applied to ensure a normal distribution because the distributions of LF and HF values were dispersed and non-normal.12

Data analysis

Technical and statistical analyses were conducted to assess demographic variables and experimental characteristics of patients. Mann-Whitney U- and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare BDI and MMPI results according to the characteristics of subjects. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare HRV results based on the presence of PTSD symptoms. Pearson's correlation was used to assess the associations among HRV, BDI, BDI item 9, and MMPI-PTSD. A regression analysis was conducted to examine how extracted variables were related to MMPI-PTSD in the correlation analysis of PTSD results. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

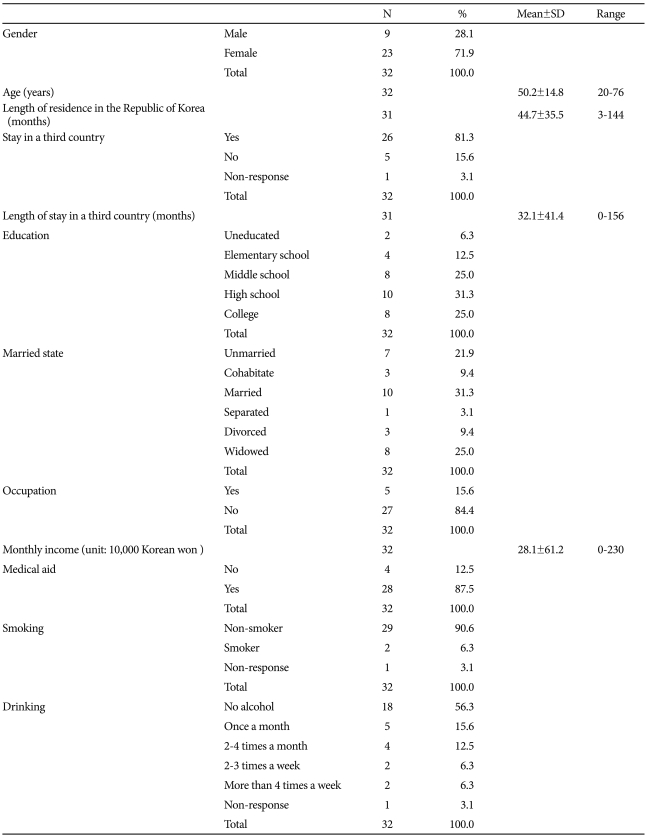

Table 1 lists the demographic and sociological characteristics of study subjects. A total of nine men and 23 women participated; the average age was 50.2 years (SD=14.8), and the age range was 20-76 years. Of the 32 respondents, 26 had stayed in a third county after defecting from North Korea and before entering South Korea; their average length of stay in that country was 32.1 months (SD=41.4), and the longest was 156 months. Overall, 56.3% of respondents had more than a high-school education, and 37.5% participants had lost a partner: one was separated (3.1%), three were divorced (9.4%), and eight were widowed (25%). Of the 32 respondents, 27 (87.5%) were unemployed. With regard to health care benefits, 28 respondents (87.5%) had medical aid, and four (12.5%) had health insurance. Of the 32 respondents, 29 (90.6%) were non-smokers, and 18 (56.3%) never comsumed alcohol.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

N: number of subjects, SD: standard deviation

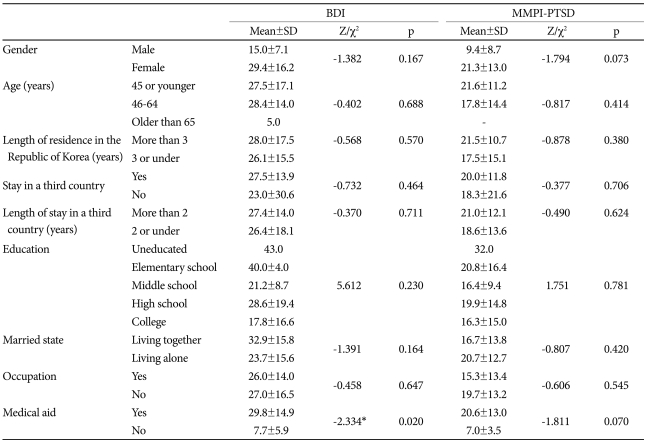

Table 2 compares average and standard deviations of BDI and MMPI-PTSD according to the characteristics of subjects. Women were more likely to be depressed, but the level of depression as measured by BDI did not differ significantly between men (average score=15, SD=7.1) and women (average=29.4, SD=16.2). When we assessed depression based on health care benefits, we found that medical aid group had an average BDI score of 29.8 (SD=14.9), and the health care insurance group had an average BDI score of 7.7 (SD=5.9); this difference was statistically significant. MMPI-PTSD results did not differ significantly between women 21.3 (SD=13.0) and men 9.4 (SD=8.7). With regard to health care benefits and MMPI-PTSD results, the medical aid group averaged 20.6 points (SD=13.0) and the health insurance averaged 7.0 points (SD=3.5); this difference was not significant.

Table 2.

Comparison of average and standard deviation of BDI and MMPI-PTSD according to the characteristics of subjects

*p<0.05. BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, MMPI-PTSD: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-PTSD scale, SD: standard deviation

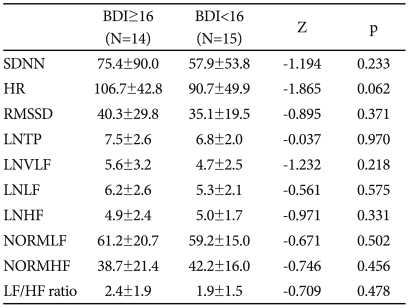

Table 3 compares the groups with and without symptoms of depression for each HRV index. The group with depression symptoms had an average heart rate of 106.7 beats/min (SD=42.8), whereas those without depression averaged 90.7 beats/min (SD=49.9); this difference was not statistically significant. The group with depression symptoms had a higher LF/HF ratio at 2.4 (SD=1.9) than did the group without symptoms 1.9, (SD=1.5), but difference was also not statistically significant.

Table 3.

HRV comparison between depression group and non-depression group, measured by BDI

HRV: heart-rate variability, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, SDNN: standard deviation of the NN intervals, HR: heart rate, RMSSD: root of the mean squared differences of successive NN intervals, LNTP: log total power, LNVLF: log very-low-frequency components, LNLF: log low-frequency components, LNHF: log high-frequency components, NORMLF: normalized low-frequency components, NORMHF: normalized high-frequency components, LF/HF ratio: low-frequency/high-frequency ratio. N: number of subjects

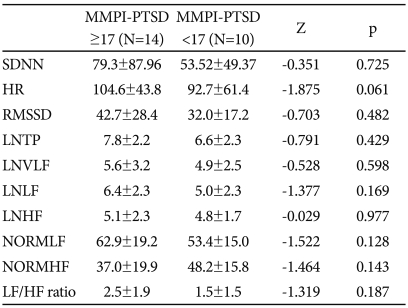

Table 4 compares the groups with and without PTSD symptoms by each HRV index. The average heart rate was 104.6 beats/min (SD=43.8) among the group with PTSD symptoms and 92.7 beats/min (SD=61.4) among the group without symptoms; this difference was not statistically significant. The group with PTSD symptoms had a higher LF/HF ratio (2.5, SD=1.9) than the group without PTSD symptoms (1.5, SD=1.5), but this difference was also not statistically significant.

Table 4.

HRV comparison between PTSD and non-PTSD groups as defined by MMPI-PTSD scores

HRV: heart-rate variability, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, SDNN: standard deviation of the NN intervals, HR: heart rate, RMSSD: root of the mean squared differences of successive NN interval, LNTP: log total power, LNVLF: log very-low-frequency components, LNLF: log low-frequency components, LNHF: log high-frequency components, NORMLF: normalized low-frequency components, NORMHF: normalized high-frequency components, LF/HF ratio: low-frequency/high-frequency ratio. N: number of subjects

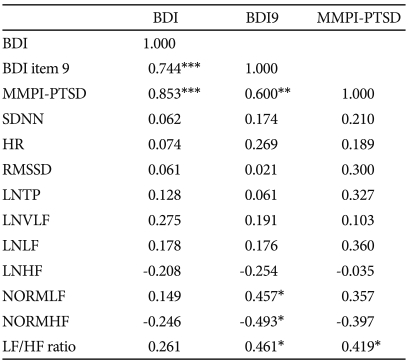

Table 5 lists the variables related to autonomic nervous system functioning in HRV and the correlations between BDI, BDI item 9, and MMPI-PTSD. A statistically significant correlation appeared between MMPI-PTSD results and the LF/HF ratio (r=0.419, p<0.05), a comprehensive index for sympathetic/parasympathetic nervous system balance or activity of the sympathetic nervous system in the heart. BDI item 9 was correlated with the LF/HF ratio (r=0.461, p<0.05), as was the normalized LF (r=0.457, p<0.05), but the latter was negatively correlated with normalized HF (r=-0.493, p<0.05), which is known to be an index of parasympathetic nervous system functioning.

Table 5.

Analysis of correlations among HRV, BDI, BDI item 9, and MMPI-PTSD

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. HRV: heart-rate variability, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, SDNN: standard deviation of the NN intervals, HR: heart-rate, RMSSD: root of the mean squared differences of successive NN interval, LNTP: log total power, LNVLF: log very-low-frequency components, LNLF: log low-frequency components, LNHF: log high-frequency components, NORMLF: normalized low-frequency components, NORMHF: normalized high-frequency components, LF/HF ratio: low-frequency/high-frequency ratio

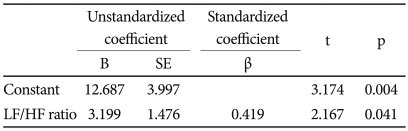

Table 6 lists the results of the regression analysis between LF/HF ratios and MMPI-PTSD results; the R-value was 13.8% (Adj. R2=0.138, F=4.695, p=0.041). The regression model revealed that the LF/HF ratio (β=0.419) was a strong factor in predicting MMPI-PTSD scores.

Table 6.

Regression analysis of LF/HF ratio and MMPI-PTSD

Adj. R2=0.138, F=4.695, p=0.041. LF/HF ratio: low-frequency/high-frequency ratio, MMPI-PTSD: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-PTSD scale

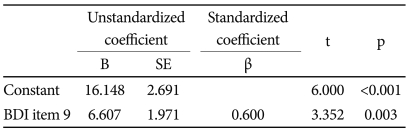

Table 7 lists the result of the regression analysis between BDI item 9 and MMPI-PTSD results; the R-value was 32.8 (Adj. R2=0.0328, F=11.234, p=0.003). The regression model revealed that BDI item 9 (β=0.600) was a strong factor in predicting MMPI-PTSD scores.

Table 7.

Regression analysis of BDI item 9 and MMPI-PTSD

Adj. R2=0.328, F=11.234, p=0.003. MMPI-PTSD: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-PTSD scale

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among North Korean defectors along with their level of depression and the correlation of both with heart-rate variability to explore the possibility of using HRV as an objective neurobiological index of signs of autonomic nervous system disorder and level of reaction to stress.

Our regression model revealed that the LF/HF ratio (β=0.419) was a statistically significant explanatory variable for MMPI-PTSD scores. In other words, the LF/HF ratio may be used as an objective neurophysiological index to predict PTSD. Mellman et al.24 suggested that people with active noradrenalin, which causes a high LF/HF ratio during REM sleep, may be more prone to stress disorders after experiencing trauma.. Patients with a stress disorder after experiencing trauma have low HF values and high LF values, and the balance of the autonomic nervous system is known show increased sympathetic nervous system activity. The HF component is known to be especially closely related to the electrical stability of the heart, and factors such as stress, fear, and anxiety can reduce HF values.22 Therefore, patients with PTSD frequently exhibit imbalanced autonomic nervous systems compared with healthy individuals. Cohen et al.25 conducted a preliminary experiment with nine PTSD patients and found that they had a significantly higher pulse and significantly reduced HRV. Because measurement of HRV is unlikely to involve the subjectivity of an examiner, the results can be used immediately to objectively measure the neurological balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems and can be useful in explaining the relationship to patients. For this reason, this technique may be widely experimentally used in psychiatry in the future.

BDI and MMPI-PTSD results were statistically correlated (r=0.853, p<0.001). Regression analysis revealed that BDI item 9 (β=0.600) was a strong and significant factor in predicting MMPI-PTSD scores. Kinjie26 suggested that a coexisting major depressive disorder is a predicting factor for PTSD. Some studies have reported low HRV results among patients with depression who are suffering from high anxiety27 and increased heart rate as well as among patients with major depression disorder,28 but other studies have found no significant differences in these values compared with healthy individuals.29 These different results may stem from differences in methodology or study population (e.g., age, sex, level of depression). Depression is known to be a major factor in cardiovascular aftereffects or sudden death, which can occur after cardiac infarction. Sandra et al.7 demonstrated that physical symptoms can be predicting factors for depression, and physical symptoms and depression are very closely related. Many studies have demonstrated the relationship between HRV and the effects of cardiac infarction and between changes in heart rate and depression.15

Of our respondents, 37.5% had lost a spouse due to death, divorce, or separation. Breslau et al.30 argued that it is difficult to obtain accurate PTSD results without considering socio-demographic variables and that support from family can alleviate emotional stress. PTSD is generally known to occur more frequently among women.31 When women and men are exposed to the same trauma, women are twice as likely to suffer from PTSD.32 After being exposed to the same trauma, women are more likely than men to lack a social support system during the process of overcoming the trauma. Also women are more likely to exhibit more frequent and severe avoidance, emotional dampening, excessive tension, and physical symptoms compared with men exposed to the same trauma.33 Further study of North Korean women defectors and family support networks is required.

Among our respondents, the average period of stay in a third country was 32.1 months, longer than the period reported by Min et al.,34 which was 21.72 months. North Korean defectors may experience various traumas such as capture, separation from family, being sent back to North Korea, or residence in a third country. Therefore, they are at greater risk for PTSD compared with the general population.35 In general, traumatic experiences are known to have a cumulative effect, so an individual exposed to more trauma is at greater risk for PTSD.36 Improving the mental health of North Korean defectors will require early diagnosis of PTSD and active medical care.

This study had several limitations. First, its sample size was fairly small. Second, the subjects were North Korean defectors who attended a mental health lecture hosted by a hospital in Seoul, rather than a random sample, they cannot represent all North Korean defectors. Third, we were unable to control for all factors that affect HRV, including environmental variables such as noise and temperature, and those that affect the autonomic nervous system, such as smoking, caffeine, etc. Future studies should consider factors including age, heart function, blood pressure, diabetes, plasma norepinephrine level, other physical disease that can affect the autonomic nervous system, short-term stress, etc. Fourth, this study used the MMPI-PTSD inventory instead of interview-based measurement. Therefore, to generalize the results of this study, the findings should be verified through large-scale systematic research including subjective evaluation of patients and evaluation of symptoms through interviews.

We assessed North Korean defectors seeking help for various physical symptoms such as headache and tiredness and measured their autonomic nervous system functioning using objective instruments. The physical symptoms appearing among North Korean defectors who are exposed to trauma have important psychopathological characteristics, generate actual pain and dysfunction in patients, affect the development of disease, and increase unnecessary medical use. Thus, it is very important to clarify the characteristic physical symptoms appearing among PTSD patients. If the PTSD symptoms and physical symptoms of North Korean defectors are not treated and continue for a long period of time, these defectors will have more difficulty adapting to our society; this could cause various social problems nationally. HRV has recently received considerable attention in the field of psychiatry because it can measure the activity of the autonomic nervous system, which is closely related to physical symptoms, in a non-invasive way, in a short period of time, and for a reasonable cost. This study assessed the possibility of using HRV as an objective method of evaluation. Further systematic research is needed to assess changes in the autonomic nervous system after treatment for PTSD.

Our results indicate that the LF/HF ratio can be used as an objective neurophysiological index in predicting PTSD. Moreover, because suicidal ideation and PTSD appear to be somewhat associated among North Korean defectors, PTSD should be diagnosed early to improve these individuals' mental health and prevent suicide. PTSD treatments should be developed that consider the special situation and culture of this population.

References

- 1.North Korean Refugees Immigration Status. North Korean Refugees Foundation. [Accessed September 28, 2011]. Available at http://www.nkr.or.kr/stats.do?cmd=selectAllList&depth1=2&depth2=1.

- 2.Blair RG. Risk factors associated with PTSD and major depression among Cambodian refugees in Utah. Health Soc Work. 2000;25:23–30. doi: 10.1093/hsw/25.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeon W, Hong C, Lee C, Kim DK, Han M, Min S. Correlation between traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder among North Korean defectors in South Korea. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:147–154. doi: 10.1002/jts.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee Y, Lee MK, Chun KH, Lee YK, Yoon SJ. Traumatic experience of North Korean refugees in China. Am J Pre Med. 2001;20:225–229. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Min SG. Can We Live along Together after the Unification? Seoul: Yonsei University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon G, Gater R, Kisely S, Piccinelli M. Somatic symptoms of distress: an international primary care study. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:481–488. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hein S, Bonsignore M, Barkow K, Jessen F, Ptok U, Heun R. Lifetime depressive and somatic symptoms as preclinical markers of late onset depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253:16–21. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chae JH. Diagnosis and pathophysiology of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Korean J Psychopharmacol. 2004;15:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lange JT, Lange CL, Cabaltica RB. Primary care treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:1035–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakell L. Adult post-traumatic stress disorder: screening and treating in primary care. Prim Care. 2007;34:593–610. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin J. The Etiology of Combat Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorders. In: Williams, editor. Posttraumatic Stress Disorders of the Vietnam Veteran. Cincinnati, OH: Disabled American Veterans; 1980. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman BH, Thayer JF. Anxiety and autonomic flexibility: a cardiovascular approach. Biol Psychol. 1998;47:243–263. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(97)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appel ML, Berger RD, Saul JP, Smith JM, Cohen RJ. Beat to beat variability in cardiovascular variables: noise or music? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Stein PK, Skala JA, Hoffman P, Jaffe AS. Change in heart rate and heart rate variability during treatment for depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:639–647. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bigger JT, Jr, Fleiss JL, Rolnitzky LM, Steinman RC. Frequency domain measures of heart period variability to assess risk late after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:729–736. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90106-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YH, Song JY. A Study of the reliability and the validity of the BDI, SDS, and MMPI-D scales. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1991;10:98–113. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang YS. A Comparative Study of the Mississippi Scale and MMPI-PTSD Scale to Diagnose PTSD[master] Jeonju: Chonbuk Univ. Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evrengul H, Tanriverdi H, Dursunoglu D, Kaftan A, Kuru O, Unlu U, et al. Time and frequency domain analyses of heart rate variability in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2005;63:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sztajzel J. Heart rate variability: a noninvasive electrocardiographic method to measure the autonomic nervous system. Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134:514–522. doi: 10.4414/smw.2004.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kay SM, Marple SL. Spectrum analysis- A modern perspective. Proc IEEE. 1981;69:1380–1419. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akselrod S, Gordon D, Ubel FA, Shannon DC, Barger AC, Cohen RJ. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: a quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science. 1981;213:220–222. doi: 10.1126/science.6166045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute of HeartMath. Autonomic Assessment Report: A Comprehensive Heart Rate Variability Analysis. Santa Cruz: HeartMath Research Center; 1996. pp. 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pagani M, Lombardi F, Guzzeti S, Rimoldi O, Furlan R, Pizzinelli P, et al. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res. 1986;59:178–193. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellman TA, Knorr BR, Pigeon WR, Leiter JC, Akay M. Heart rate variability during sleep and the early development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:953–956. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen H, Kotler M, Matar MA, Kaplan Z, Miodownik H, Cassuto Y, et al. Power spectral analysis of heart rate variability in post-traumatic stress disorder patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:627–629. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00525-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinjie JD. Severe Posttraumatic Stress Disorder among Cambodian Refugees : Symtoms, Clinical Course, and Treatment Approaches. In: Shore JH, editor. Diaster Stress Studies: New Methods and Findings. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1986. pp. 123–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tulen JH, Bruijn JA, de Man KJ, van der Velden E, Pepplinkhuizen L, Man in't Veld AJ. Anxiety and autonomic regulation in major depressive disorder: an exploratory study. J Affect Disord. 1996;40:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nahshoni E, Aravot D, Aizenberg D, Sigler M, Zalsman G, Strasberg B, et al. Heart rate variability in patients with major depression. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:129–134. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeragani VK, Pohl R, Balon R, Ramesh C, Glitz D, Jung I, et al. Heart rate variability in patients with major depression. Psychiatry Res. 1991;37:35–46. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90104-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P. Risk factors for PTSD-related traumatic event: a prospective analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:529–535. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in a urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:216–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Epstein RS, Crowley B, Vance K, Kao TC, et al. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1486–1491. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Min SK, Jeon WT, Eom JS, Yu SE. Quality of life of North Korean defectors in South Korea : three years follow-up study. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2010;49:104–113. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang SR. Development of Trauma Scale for North Korean Refugee. Seoul: Younsei University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yehuda R, Kahana B, Schmeidler J, Southwick SM, Wilson S, Giller EL. Impact of cumulative lifetime trauma and recent stress on current posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in holocaust survivors. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1815–1818. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.12.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]