Abstract

The chlorinated natural product salinosporamide A is a potent 20S proteasome inhibitor currently in clinical trials as an anticancer agent. To deepen our understanding of salinosporamide biosynthesis, we investigated the function of a LuxR-type pathway-specific regulatory gene, salR2, and observed a selective effect on the production of salinosporamide A over its less active aliphatic analogs. SalR2 was shown to specifically activate genes involved in the biosynthesis of the halogenated precursor chloroethylmalonyl-CoA, which is a dedicated precursor of salinosporamide A. Specifically, SalR2 activates transcription of two divergent operons – one of which contains the unique S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent chlorinase encoding gene salL. By applying this knowledge towards rational engineering, we were able to selectively double salinosporamide A production. This study exemplifies the specialized regulation of a polyketide precursor pathway and its application to the selective overproduction of a specific natural product congener.

Introduction

The marine bacterium Salinispora tropica produces a series of potent natural product proteasome inhibitors, the salinosporamides, which are assembled by a hybrid polyketide synthase–nonribosomal peptide synthetase (PKS–NRPS) pathway from three distinct fragments (Gulder and Moore, 2010). Two of the biosynthetic building blocks, namely acetate and the nonproteinogenic amino acid cyclohexenylalanine, are common to the natural salinosporamides. The third substrate, however, is derived from a mixture of branched malonate units that ultimately distinguishes the different salinosporamide molecules. This difference in the chemical nature of the salinosporamide C-2 side chain has been shown to have a profound effect on their biological activity. The chlorinated salinosporamide A is not only the major family member produced in S. tropica, it is also its most potent. Structure-activity relationship studies (Macherla et al., 2005) together with high-resolution X-ray analysis of the inhibitor-proteasome complex (Groll et al., 2006) revealed that salinosporamide A’s halogen acts as a leaving group upon proteasome β-subunit binding to heighten its potency as an irreversible inhibitor. Natural analogs without reactive C-2 residues are consequently reversible inhibitors of the 20S proteasome and are substantially less potent. Hence, salinosporamide A was selected and advanced to clinical trials as an anticancer agent where it was produced for Phase I studies by large-scale microbial fermentation (Fenical et al., 2009; Potts et al., 2011).

Biosynthetic studies illuminated the convergent pathways to the salinosporamides in which α-substituted malonyl-coenzyme A (-CoA) derivatives are individually synthesized and processed by the salinosporamide assembly line synthetase (Beer and Moore, 2007). An elaborate eight-step pathway converts S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) to the dedicated salinosporamide A precursor chloroethylmalonyl-CoA (Eustáquio et al., 2009; Kale et al., 2010), and its encoding genes reside within the 41-kb sal gene cluster. The non-halogenated salinosporamides B, D and E are conversely synthesized from ethyl-, methyl- and propylmalonyl-CoA (Liu et al., 2009), respectively, that with the exception of the latter are common primary metabolic precursors. Herein we show that the biosynthesis of chloroethylmalonyl-CoA is differentially regulated by the pathway specific regulator SalR2 and that its overexpression results in the selective overproduction of the clinically important salinosporamide A over its less active aliphatic analogs. This mechanism of regulation dedicated to precursor supply that influences the production of a specific natural product over structurally related analogs has to the best of our knowledge not before been described.

Results

Identification of the salinosporamide A-specific pathway regulator SalR2

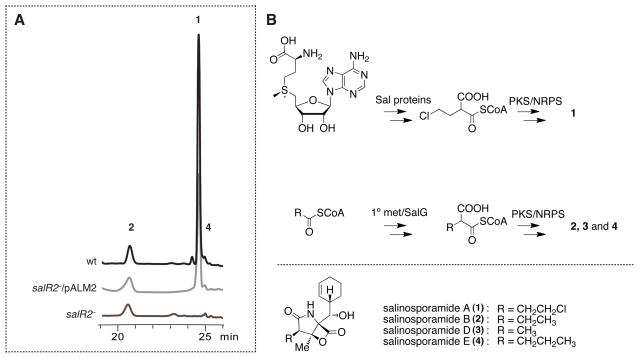

The sal biosynthetic gene locus contains three regulatory genes amongst its 31 open reading frames. Bioinformatics analyses suggested that SalR1 is a MerR-type regulator commonly involved in antibiotic resistance (Brown et al., 2003), SalR2 is an unusual member of the LuxR-type subfamily of response regulators lacking a cognate histidine kinase (see SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (Gao et al., 2007; Hutchings, 2007), and SalR3 is a putative LysR-type transcriptional regulator (Maddocks and Oyston, 2008). We interrogated the function of each regulatory gene by gene inactivation in which we replaced each gene by an apramycin-resistance cassette as previously described (Eustáquio et al., 2008; Gust et al., 2003). Metabolic profiling of the salR1− and salR3− deletion mutants did not show any significant effect on salinosporamide production. A duplicate salR3 locus (strop_1049) also resides outside the sal biosynthetic gene cluster where it may complement the function of salR3 (strop_1032). Chemical analysis of the salR2− mutant, on the other hand, revealed a striking difference compared to the parental strain. Production of the chlorinated major compound salinosporamide A was nearly abolished to trace wild-type levels, while no effect was observed on the production of the deschloro analogs, salinosporamides B and E (Fig. 1A). To further verify that gene inactivation of salR2 alone was responsible for the observed phenotype, we applied genetic in trans complementation. The pSET152-based integration vector pALM2 was designed to express salR2 under native promoter control. After vector integration, the new mutant salR2−/pALM2 restored salinosporamide A biosynthesis (Fig. 1A). The selective attenuation of salinosporamide A production strongly suggested that the SalR2 regulatory function is dedicated to chloroethylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, gene inactivation of salR2 did not cause any difference in growth compared to the parental strain (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

Gene inactivation and complementation of salR2 in S. tropica CNB-440. (A) HPLC traces of S. tropica wild-type (wt) in black, salR2− mutant in grey, and in trans complemented mutant (salR2−/pALM2) in light grey. Gene inactivation of salR2 leads to selective reduction of salinosporamide A (1) production, without effect on the deschloro analogs salinosporamide B (2) and E (4). Production of salinosporamide D was not detectable in these studies. (B) Conversion of S-adenosyl-L-methionine to the salinosporamide A-specific precursor chloroethylmalonyl-CoA requires eight proteins encoded within the sal gene cluster (top panel). Additionally the Sal PKS/NRPS machinery also incorporates common extender units, which are derived from primary metabolism (middle panel). This leads to a suite of analogs (bottom panel). See also Figure S1.

Fig. 2.

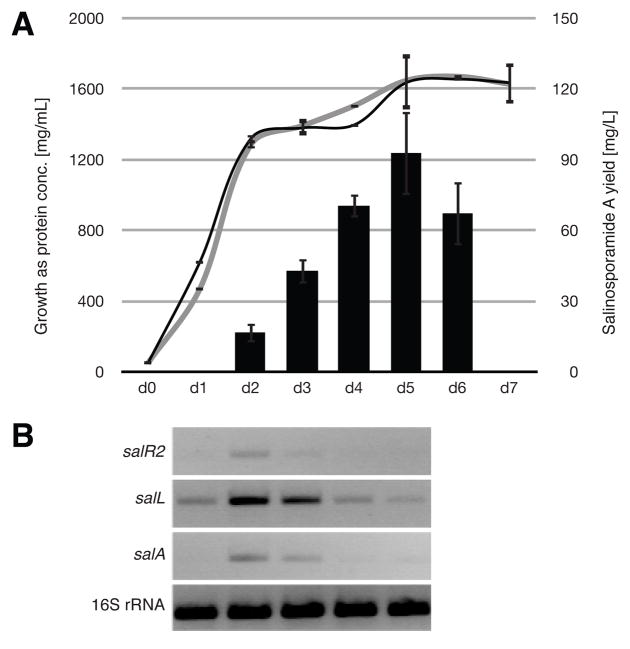

Growth-dependent salinosporamide A biosynthesis. (A) Growth curve of S. tropica CNB-440 in black and salR2− mutant in grey on the primary axis (lines) in relation to salinosporamide A production on the secondary axis (columns). Each analysis was carried out in duplicate. (B) Reverse transcription time course over five consecutive days of the regulatory gene salR2, the chlorinase gene salL and the PKS gene salA as well as 16S rRNA control. Starting at day 1, samples were taken on five consecutive days from a S. tropica CNB-440 culture.

SalR2 activates early steps in chloroethylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis

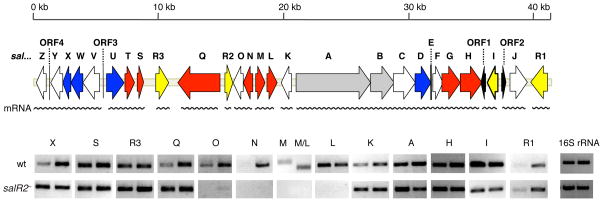

Transcription of representative sal genes was investigated in the wild-type as well as the salR2− strain. To gain insight about timing of sal gene expression, we examined the relationship between growth and salinosporamide A production as well as transcription of representative genes in S. tropica CNB-440. Salinosporamide A production exhibited a growth-dependent pattern, initiated in the late exponential phase and reaching maximum yields during the transition phase around day five (Fig. 2). Based on these data, two time points at which salinosporamides were being actively produced and sal genes actively transcribed (corresponding to days 2 and 3) were chosen as sample points for further transcriptional analysis. The comparative transcription profiles of S. tropica wild-type and the salR2− mutant at late exponential and early stationary phase are shown in Fig. 3. All analyzed sal genes are transcribed in both strains except for the two operons salNO and salML, which are transcribed from oppositely oriented promoters. Three of these gene products are known to be involved in chloroethylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis (Eustáquio et al., 2009; Kale et al., 2010). The function of the fourth, the putative cyclase gene salO (27% identity to DpsY from Streptomyces peucetius), on the other hand, is unknown and may participate in the cyclization of the γ-lactam-β-lactone bicycle (Lomovskaya et al., 1998). To assess its involvement in salinosporamide biosynthesis, we inactivated it by PCR-targeted mutagenesis. The resulting mutant maintained wild-type production levels of all salinosporamides, thereby suggesting that SalO is not directly involved in salinosporamide biosynthesis as originally considered.

Fig. 3.

Semi-quantitative reverse transcription analysis of sal genes comparing S. tropica CNB-440 (wt) and salR2− mutant. Total RNA was extracted from days 2 and 3, which were established as suitable data points (see Fig. 2B). Putative transcription units (wavy lines) were predicted based on open reading frame organization and intergenic regions. In the salM panel we added the RT-PCR results of the salM/L intergenic region to prove co-transcription of salM and salL. Genes are color-coded based on confirmed/predicted function: assembly of core γ-lactam-β-lactone ring (grey), biosynthesis of chloroethylmalonyl-CoA (red) and of the nonproteinogenic amino acid L-3-cyclohex-2-enylalanine (blue), regulation and resistance (yellow), unknown (white) and two partial transposases (black).

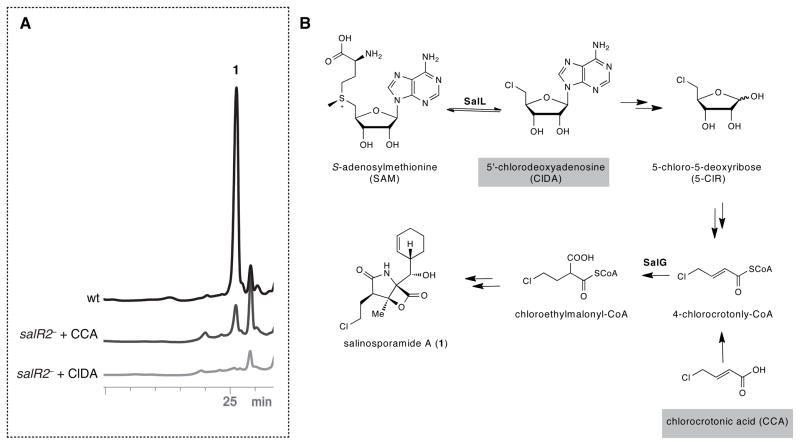

Combined with the inactivation experiments, the transcriptional analysis results described above clearly suggest that SalR2 regulates the early steps in the biosynthesis of chloroethylmalonyl-CoA through transcriptional activation of salL, salM, and salN but not of salQ, salH, salG, salS and salT. To provide a third line of evidence, we carried out a chemical complementation experiment in which the salR2− mutant was supplemented with the late intermediate analog 4-chlorocrotonic acid to restore salinosporamide A biosynthesis through action of the crotonyl-CoA reductase/carboxylase SalG (Eustáquio et al., 2009). Supplementation of the first pathway intermediate generated by chlorinase SalL, 5′-chloro-5′-deoxyadenosine (ClDA), was used as a negative control. Indeed, 4-chlorocrotonic acid restored salinosporamide A production in the salR2− mutant while ClDA did not (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Chemical complementation of the salR2− mutant. (A) HPLC traces of S. tropica wild-type (wt) in black, salR2− mutant complemented with 4-chlorocrotonic acid (CCA) in grey and with 5′-chlorodeoxyadenosine (ClDA) in light grey. (B) Biosynthetic scheme of the chloroethylmalonyl-CoA pathway showing two substrates used for chemical complementation (boxed).

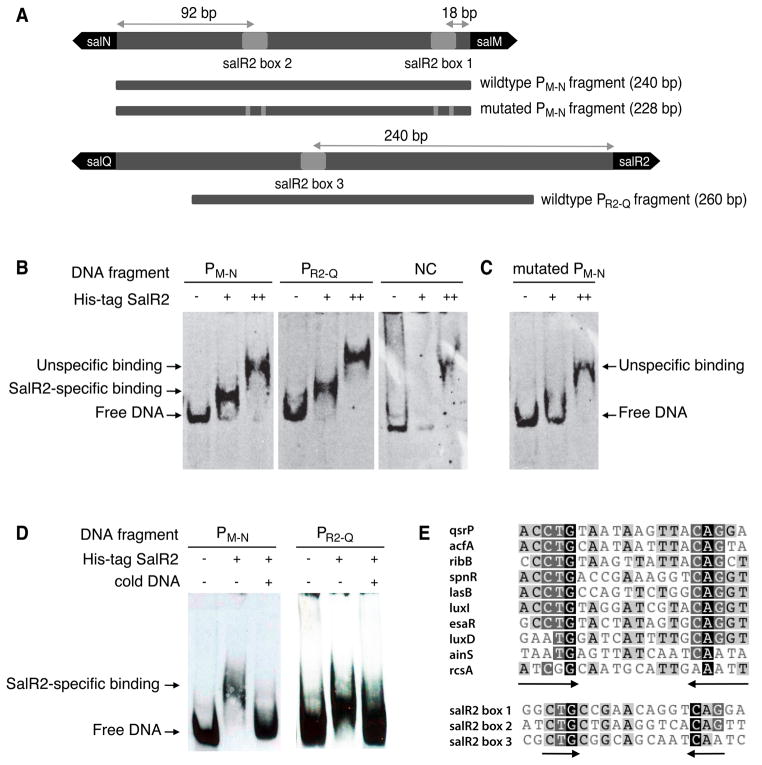

SalR2 binds specifically to the salM-salN and salR2-salQ intergenic regions

The gene product of salR2 is a 24.3 kDa protein displaying two distinctive domains as identified by a Pfam search (Fig. S1)(Finn et al., 2010). The N-terminus contains an atypical receiver domain of response regulators (O’Connor and Nodwell, 2005; Ruiz et al., 2008; Schar et al., 2005; Tian et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009), which is paired with a C-terminal LuxR-type DNA binding domain (Fuqua et al., 2001). Since transcription of the divergent operons salNO (phosphatase; conserved hypothetical) and salML (dehydrogenase; SAM-dependent chlorinase) was shown to directly depend on SalR2 activity, we hypothesized that SalR2 binds to the bidirectional salM-salN promoter region. Furthermore LuxR-type proteins are known to bind to their own promoter to repress or stimulate transcription (Fuqua et al., 1994). To address the proposed functions, we carried out DNA binding studies (Fig. 5) using electromobility shift assays (EMSA) with recombinant SalR2, which was produced as a N-terminal His8-fusion protein from Escherichia coli. As DNA probes, we chose the full intergenic region between salN and salM (PM-N) as well as a fragment located 60 to 320 nt upstream of the salR2 translational start codon (PR2-Q). As a negative control, we used a fragment isolated from the multiple cloning site of the vector pSET152 (NC). The recombinant SalR2 protein showed clear and specific binding to fragments PM-N and PR2-Q (Fig. 5B and D).

Fig. 5.

SalR2 DNA binding studies. (A) Schematic representation of sal DNA fragments used in the EMSA. Distances shown are relative to translational start codons and center of the putative SalR2 binding site. (B) EMSA using 65 nM DNA (2 ng) and (−) no SalR2 protein or (+) and (++) increasing concentrations of purified, His8-tagged SalR2, i.e. 0.8 μM (0.4 μg) and 1.2 μM (0.6 μg), respectively. A fragment containing the multiple cloning site of pSET152 vector was used as negative control (NC). Note that high concentrations of SalR2 (++) lead to unspecific binding under the EMSA conditions tested as evidenced by binding to NC. (C) EMSA using 65 nM of the mutated PM-N DNA fragment and no protein (−) or 0.8 μM (+) and 1.2 μM (++) SalR2 protein. Deletion of the LuxR-type DNA binding motif present in the salM-N intergenic region abolishes SalR2 binding. (D) Competition assay using 65 nM DNA and 0.8 μM His8-tagged SalR2. An additional 125-fold molar excess of specific competitor, non-labeled DNA (cold DNA) was added when indicated (+). (E) Alignment of known and putative LuxR-type binding motifs. Top panel represents alignment of verified lux boxes (Eustáquio et al., 2009) located upstream of genes coding for QsrP (YP_207016), AcfA (YP_205361), RibB (YP_204085), LuxI (YP_206882), LuxD (YP_206880) and AinS (YP_204420) from Vibrio fischeri ES114, SpnR (AAN52499) from Serratia marcescens, LasB (AAZ81561) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, EsaR (L32184) from Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii DC283 and RcsA (AY819768) from Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii. Bottom panel shows three putative SalR2 binding sites within the sal gene cluster, identified upstream of salM, salN and salR2 respectively. See also Figure S2.

To further identify specific SalR2 DNA binding sites, we carried out a bioinformatics analysis based on the knowledge that LuxR-like regulators usually bind to a 20-bp inverted repeat similar to the lux box (Fuqua et al., 2001). We identified multiple 20-bp long, imperfect inverted repeats in the salM-salN and the salR2-salQ intergenic regions (Fig. 5A and E). The consensus sequence from the two sites of salM-salN contains six strictly conserved nucleotides separated by a 10-nt spacer: CTG-(N10)-CAG while the sequence for the salR2-salQ site contains one mismatch, i.e. CTG-(N10)-CAA. The consensus sequences are in agreement with the lux box of Vibrio fischeri, in which at least 5 of the 6 bases are essential for LuxR binding (Antunes et al., 2008). To establish that this motif is essential for SalR2 binding, we altered the sequence of fragment PM-N by deleting the conserved residues CTG and CAG from both motifs. Indeed SalR2 was not able to bind to the mutated PM-N fragment as shown in Fig. 5C.

To locate SalR2 binding sites relative to transcription start sites (tss), we employed the RACE ligation-mediated PCR approach (Tillett et al., 2000). Total RNA was extracted from mid-exponentially grown wild-type S. tropica and subjected to 5′-RACE as described in Methods. The detected RACE products for salR2 and salM are shown in Figure S2A. The two salR2 RACE products differ only 16 bp in size. Since the shorter cDNA fragment does not contain conserved motifs for sigma factor binding, it is thought to derive from a partially degraded mRNA product. Under the tested conditions, we therefore identified one transcription start site for salR2 (tss-1), which is located 143-nt upstream of the translation start codon and preceded by conserved sequences in the −35 (GCAGGC) and −10 (TAAAGT) regions (Fig. S2B and C). Preliminary results from Roche 454 transcriptome sequencing revealed a second salR2 transcription start site (tss-2) located 207-nt upstream of the salR2 start codon and preceded by conserved sequences in the −35 (GCAGCA) and −10 (TAAGTT) regions (Fig. S2B and C). The putative SalR2 binding site, identified as salR2-box3 in the salR2-Q intergenic region, is therefore centered at −33 relative to tss-2. To confidently assign the salM tss, we compared the initial 454 sequencing results with those obtained by RACE. The largest of three salM RACE fragments contained conserved −10 and −35 motifs (Fig. S2A and B), which was similarly found by 454 transcriptome sequencing. Based on these findings the transcription start site was assigned at −81 relative to the translational start codon and to be preceded by sequences in the −35 (GCGGCG) and −10 (TAGCGT) regions (Fig. S2D). The motif salR2-box2 is therefore centered at −64 relative to the salM tss. We were able to successfully identify transcription start sites for salR2 and salM, but identification of a salN transcription start site remained unsuccessful using RACE. Neither was the sequencing coverage sufficient for salN to confidently identify a tss using the 454 transcriptome results. Therefore the function of the putative binding motif salR2-box1 remains unassigned at this point.

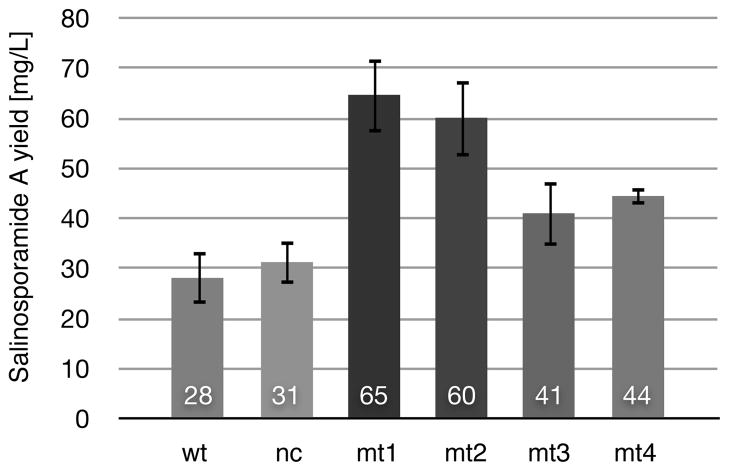

Overexpression of salR2 leads to enhanced salinosporamide A production

Overexpression of pathway-specific activators has been reported to lead to increased production of various secondary metabolites, indicating a limiting role of the transcriptional activator in compound production (Liu et al., 2005; Lombo et al., 1999). We therefore intended to introduce additional salR2 gene copies in trans in order to specifically increase salinosporamide A production. Earlier attempts in our laboratory to use the high copy vector pWHM3 (Vara et al., 1989) engineered to contain oriT for conjugative transfer in Salinispora remained unsuccessful. However we knew from the complementation studies above that the integrative vector pALM2 was suitable for genetic manipulations in Salinispora. The pSET152-based construct contains a φC31 Streptomyces phage-derived integrase gene and the phage attachment site attP (Thorpe et al., 2000). φC31 phage-based vectors have been widely used and shown to integrate in pseudo attB sites (Thorpe et al., 2000). We were able to identify three pseudo integration sites in 10 independent S. tropica mutant strains. pSET152-derived plasmids integrated in three open reading frames (strop_0305, strop_0483 and strop_3569, see SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Since pSET152 integration did not seem to have a negative effect on salinosporamide A production, we used pALM2 to introduce salR2 into the wild-type strain. We also tested activity of two candidate, vegetative promoters in the S. tropica salR2 deletion mutant, since no constitutive promoters were known for this genus. The first heterologous promoter tested was ermE*p from Saccharopolyspora erythraea (Bibb et al., 1994). The construct pALM201 containing salR2 under transcriptional control of ermE*p was, however, not able to restore salinosporamide A production in the salR2− mutant. Although this vegetative promoter is frequently used for genetic complementation studies in Streptomyces, ermE*p has been shown to exhibit low activity in non-streptomycete actinobacteria such as Actinoplanes and Amycolatopsis (Wagner et al., 2009). We next tested the promoter of the apramycin resistance gene aac(3)IV, since previous studies indicated high activity in the related Actinoplanes friuliensis (Wagner et al., 2009). The aac(3)IV promoter region, including its ribosome binding site, was isolated from pSET152 and cloned upstream of the salR2 translation start codon to give pALMapra. This construct was able to restore salinosporamide A production in the salR2− mutant. We next introduced pALMapra into the wild-type strain and cultured two independent mutants in 24 deep-well plates (Siebenberg et al., 2009), allowing for more accurate salinosporamide quantification. Under these conditions, we observed a 2-fold selective increase of salinosporamide A for two independent wild-type/pALMapra mutants, while only a modest 1.3-fold increase for two wild-type/pALM2 mutants relative to the parental strain and a negative control was achieved (Fig. 6). We also compared the elevated salinosporamide A levels to production yields of salinosporamide B and E in the parental strain and two wild-type/pALMapra mutants. We found that while salinosporamide A levels are increased 2-fold, yields of the deschloro analogs remained at wild-type levels.

Fig. 6.

Overexpression of salR2 under control of a constitutive promoter (wt/pALMapra) and the native upstream region (wt/pALM2). Two independent wt/pALMapra mutants (mt1 and mt2) show 2-fold increase in salinosporamide A production compared to the wild-type (wt) and control strain wt/pALM0 (nc). In contrast only a modest increase was observed in two independent wt/pALM2 mutants (mt3 and mt4). Average production levels are shown inside each graph bar. See also Figure S6.

Discussion

This study provides new insight in the regulated biosynthesis of chloroethylmalonyl-CoA, which is a specific precursor of the promising anticancer agent salinosporamide A. SalR2 chiefly controls the divergently transcribed salNO and salML gene pairs that include the unique biosynthetic enzyme SalL, which initiates the diversion of the important cofactor SAM from primary metabolism to this dedicated secondary metabolic pathway (Eustáquio et al., 2008).

Many of the secondary metabolic pathways explored to date involve regulators that control the expression of biosynthetic enzymes crucial for the synthesis of the core natural product skeleton (Martín and Liras, 2010), and therefore result in the general flux of pathway mixtures versus individual analogs. Secondary metabolic pathways naturally lead to compound mixtures and originate from a multitude of metabolic scenarios that include partial intermediate processing by tailoring enzymes, the inherent chemical reactivity of natural product intermediates, or in the case of the salinosporamides, the assembly of different precursor mixtures. Not only does building block supply contribute to product mixtures that result from substrate tolerant enzymatic processing, but supply is also a key contributor to metabolic flux and therefore production throughput. In the case of PKS-derived molecules, the supply of acyl-CoA starter and extender unit precursors has been shown to be one of the key rate-limiting steps in biosynthesis (Liu and Reynolds, 1999; Pulsawat et al., 2007). Increasing precursor supply, in other examples, has led to increased production yields, such as for the anti-tumor agent ansamitocin P-3 (Lin et al., 2011) and the antibiotic daptomycin (Huber et al., 1988). Orthogonal to these chemical complementation examples, the expression of precursor biosynthetic enzymes has been shown to be even more powerful in influencing production yields (Wang et al., 2011). The example described here with SalR2 represents another approach involving the overexpression of a transcriptional activator of precursor biosynthesis genes.

LuxR-like proteins, such as SalR2, usually activate gene transcription by binding to lux-type boxes centered near position −42.5 (Devine et al., 1989), and less likely to promoter elements that are located further upstream. One example of the latter includes the activator binding site for UhpA from E. coli located at −64 from the uhpT tss (Merkel et al., 1992). This independent study is in agreement with SalR2’s binding site at −64 from salM’s tss. Additionally, SalR2 was also shown to bind to a site (box3, Fig. 5) at the −35 region of its own tss (tss-2). A likely conclusion is that SalR2 negatively autoregulates its own transcription, which is in agreement with previous reports on LuxR-type regulators (Cramer and Eikmanns, 2007).

The signal receiving domain of SalR2 holds an unusual response regulator sequence, which lacks a phosphorylation site (Fig. S1). Other examples of atypical response regulators include JadR1 from Streptomyces venezuelae (Wang et al., 2009), NblR from Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 (Ruiz et al., 2008), HP1021 and HP1043 from Helicobacter pylori (Schar et al., 2005), and RamR (O’Connor and Nodwell, 2005) and WhiI (Tian et al., 2007) from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). These examples, including SalR2, lack a cognate histidine kinase, and, therefore, a phosphorylation-independent mode of activation is likely necessary for SalR2 function.

Curiously, a SalR2 homolog (FlG, 34% identity) resides in the fluorometabolite biosynthesis cluster in Streptomyces cattleya (Huang et al., 2006). The fl locus shares homology with two structural genes of the sal gene locus – the fluorinase flA and the purine nucleotide phosphorylase flB are closely related to salL and salT, respectively. On the other hand, comparison of the related salinosporamide K and cinnabaramide biosynthetic loci in “S. pacifica” strain CNT-133 (Eustáquio et al., 2011) and Streptomyces sp. JS360 (Rachid et al., 2011), respectively, revealed that salR2 and all eight chloroethylmalonyl-CoA pathway genes are absent. These observations suggest that the chloroethylmalonyl-CoA specific regulator salR2 was transferred to the S. tropica sal locus together with the genes encoding the chlorinated PKS building block, thereby resulting in its regulated assembly separate from that of the main salinosporamide molecule.

Significance

Salinosporamide A is a clinically promising anticancer agent produced by Salinispora tropica. As salinosporamide A is presently being manufactured by saline fermentation for clinical trials (Potts et al., 2011), methods to increase yields are important in lowering the cost of production as this drug candidate moves beyond phase I clinical evaluation. A prerequisite to manipulate production of salinosporamdie A is an extensive set of genetic tools. However many expression plasmids and promoters (constitutive or inducible) developed for Streptomyces are not applicable for other actinomycetes. Therefore this study allowed us to expand the genetic tool box for a very prolific but non-streptomycete, marine-obligate genus. Using a multidisciplinary approach we showed that SalR2 is a pathway-specific regulator of chloroethylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis that is a dedicated PKS substrate of salinosporamide A. This mode of regulation of a biosynthetic precursor in polyketide assembly is to the best of our knowledge unique. Furthermore the ectopic overexpression of SalR2 under constitutive promoter control was key to our ability to selectively double the production yield of salinosporamide A without increasing the production levels of its minor analogs.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1. Salinispora tropica CNB-440 and its derivatives were routinely cultured in Erlenmeyer flasks containing a stainless steel spring and A1 sea water-based medium at 28°C (Beer and Moore, 2007). The REDIRECT© technology kit for PCR targeting (Gust et al., 2003) was obtained from Plant Bioscience Limited (Norwich, UK). pCC1FOS-based (Epicentre) fosmid BHXS1782, which contains the sal gene cluster except salR1 and salJ, was used for gene replacement of salR2 and salR3. Fosmid BHXS3930 was used instead for gene replacement of salR1. For selection of recombinant strains, the following antibiotics were used in indicated concentrations: apramycin (200 μg/mL for S. tropica; 50 μg/mL for E. coli), chloramphenicol (5 μg/mL for S. tropica; 12–25 μg/mL for E. coli), carbenicillin (100 μg/mL), kanamycin (50 μg/mL for E. coli), streptomycin (10 μg/mL for S. tropica; 50 μg/mL for E. coli), spectinomycin (50–100 μg/mL for S. tropica; 50 μg/mL for E. coli) and nalidixic acid (100 μg/mL). DNA isolation and manipulation were performed according to standard procedures (Kieser et al., 2000; Sambrook and Russell, 2001). Derivatives of the E. coli/Streptomyces shuttle vector pSET152 (Bierman et al., 1992; Kuhstoss and Rao, 1991) were generated during this work (Table S1) and used to introduce salR2 gene copies in trans into the S. tropica chromosome.

Growth measurement in Salinispora tropica

Cell growth of S. tropica is difficult to measure by standard spectrometric methods such as optical density (OD), since this actinomycete forms cell aggregates. We therefore turned to a simple protein extraction protocol to measure cell growth over time. Cells were sampled and processed as described before (Meyers et al., 1998). UV absorptions at 230 nm and 260 nm were measured using a Nanodrop 1000 and total protein concentration was calculated using the equation:

Purification of recombinant SalR2

The gene salR2 was amplified by PCR from fosmid BHXS1782 using the primer pair FP/RP-pAL4, cut with HindIII and XhoI and ligated into the same sites of pHIS8 (Jez et al., 2000) yielding plasmid pHIS8-salR2, which was used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS. The resulting transformant was inoculated in 3 L of auto-induction medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL of kanamycin (Studier, 2005) and grown at 28 °C for 16–18 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and frozen at −20 °C. All purification steps were carried out at 4 °C. Buffer B contained 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol as well as varying imidazole concentrations in mM range as indicated by the number of the buffer name. Frozen cells were thawed in 30 mL buffer B5 and 1% Tween. After the cell pellet was completely resuspended, lysozyme (1 mg/mL) was added and the mixture was incubated for 30 min with stirring. The suspension was sonicated for 3 min in 10 s on/off cycles. Cell debris were removed by centrifugation for 30 min at 20000 rpm. The cleared supernatant was mixed with 1 mL pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) and incubated for 60 min under gentle stirring. The protein-Ni-NTA slurry was collected by centrifugation (6000 rpm for 10 min), washed with 50 mL buffer B5 to separate from unbound protein, and resuspended in buffer B20. His8-SalR2 was further purified on column by extensive washing with 20 mL buffer B20, 10 mL buffer B40 and 10 mL buffer B60 followed by an elution step with 2.5 mL buffer B250. In the final desalting and concentration steps, the protein was applied on a PD-10 column (GE healthcare), eluted in 3.5 mL storage buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.9), 2 mM DTT), and concentrated 7-fold using a VIVASPIN 6 column (Sartorius) at 6000 rpm and 10 °C. Aliquots of recombinant SalR2 protein were stored at −70 °C until use in DNA-binding assays.

Gel mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Gel shift assays were performed using the DIG Gel Shift Kit, 2nd Generation (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The reaction was carried out at 25 °C in 20 μL final volume containing 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 ng/μL poly [d (A-T)], 5 ng/uL poly L-lysine, 5% (w/v) glycerol and approximately 0.4–0.6 μg of partially purified His8-tagged SalR2. To identify specific binding, we added cold probe in 125-fold excess to the sample. After pre-incubation for approximately 5 min to establish an equilibrium, 2 ng DIG-labeled DNA fragment was added to each reaction and after an additional 15 min the mix was applied to a pre-run 5% (w/v) native polyacrylamide gel (BioRad) with 0.5x TBE as running buffer. The gel was run on ice at 55 V for 3–4 h, transferred by electroblot to a positively charged Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Biosciences), and cross-linked under UV light for 3 min. Detection was carried out following the manufacturer’s instructions and using the chemiluminescent substrate CSPD.

Inactivation of sal genes and genetic complementation of salR2

Genes were inactivated using the PCR targeting system with some modifications as previously described (Eustáquio et al., 2008b; Gust et al., 2003). For genetic complementation of the S. tropica salR2− mutant strain, we used a pSET152-based expression plasmid. Please refer to the Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Construction of salR2 overexpression plasmids under control of diverse promoters

We constructed several pSET-derived integration vectors placing salR2 under control of i) its native promoter, ii) the constitutive ermE* promoter from Saccharopolyspora erythraea (Bibb et al., 1985), and iii) the aac(3)IV promoter (Wagner et al., 2009) generating pALM2, pALM201, and pALMapra respectively. Please refer to the Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Isolation of total RNA, cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR

S. tropica strains were grown in same liquid medium as used for salinosporamide A production (see below). Aliquots (0.5–1 mL) were collected from a second-generation culture grown until late exponential and early stationary phase. Total RNA was extracted using the RiboPure™ -Bacteria kit (Ambion), and DNase I treatment was carried out for 5 h following the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated RNA (50 ng) was tested by PCR for residual genomic DNA contamination using 16S rRNA as marker, then reverse transcribed using the SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). The resulting cDNA (50 ng/25 μl reaction), Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs), and RT-primers were used for RT-PCR under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 25–30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension step for 2 min. PCR primers for semi-quantitative RT-PCR were designed for 13 putative transcription units based on their predicted operon structure, as well as the 16SrRNA gene as an interal control (Table S2). Oligonucleotides were designed using Primer3 software to generate fragments of about 250 bp in size.

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE)

To identify transcription start sites for salR2, salM and salN, we slightly modified the RACE protocol by Tillet et al (Tillett et al., 2000). Please refer to the Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Transcriptome sequencing by 454

Total RNA from a second generation culture in late exponential phase was extracted using the RiboPure Bacteria kit (Ambion) and enriched for mRNA using MICROBExpress (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After quality control (please refer to the Supplemental Experimental Procedures), the mRNA-enriched sample was subjected to the GS FLX Titanium cDNA Rapid Library Preparation Method (Roche) and sequenced (1/2 plate) using 454 technology. Mapper was run against the reference S. tropica genome (accession no. NC_009380) – number of reads (557,992), number of bases (1.65 × 108), average depth (0.7).

Chemical complementation of biosynthetic intermediates

The two compounds 5′-chlorodeoxy-adenosine (5′-ClDA, Sigma Aldrich) and 4-chlorocrotonic acid (CCA (Eustáquio et al., 2009)) were administered to the S. tropica salR2− mutant strain at a concentration of 0.33 mM after the first day of cultivation. Extraction and detection of salinosporamide A followed previous protocols (Eustáquio et al., 2009) as described below.

Analysis of secondary metabolites

For salinosporamide A production, S. tropica wild-type and mutant strains were cultivated using two different methods. The production medium for both cultivation methods was A1 sea water-based medium supplemented with 1% KBr, 0.4% Fe2SO4 and 0.1% CaCO3. The standard fermentation was conducted in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks as described in SI. The production culture (50 mL) was started with 4% of a 3–4 day old (late exponential phase) pre-culture, and 2 g (dry weight) of XAD7 resin was added after one day of fermentation. The resin was extracted on day 5 with 25 mL acetone and processed as described below. For overexpression studies, we used 24-square deepwell plates (EnzyScreen BV, Holland). Cultures were initially inoculated and grown in a Erlenmeyer flask for 24 h as described previously (Siebenberg et al., 2009). After one day, 0.6% (w/v, final concentration) siloxylated ethylene oxide/propylene oxide copolymer Q2-5247 (Dow Corning, USA) was added to the cultures, and 3 mL aliquots were transferred to the 24-square deepwell plate containing 0.1 g sterile XAD7 resin. The resin was extracted with 3 mL acetone on day 6. All shakers used for Erlenmeyer flasks and deepwell plate cultivations were orbital shakers with 25 mm shaking diameter. The crude extract was dried and redissolved in 1 mL MeCN, then analyzed by HPLC with a Phenomenex C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm; 5 μm particle size) at flow rate of 1 mL/min, using isocratic 35% MeCN in water as the mobile phase with detection at 210 nm.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Gene deletion mutants were constructed to identify SalR2 as a transcriptional activator

SalR2 acts selectively on the chloroethylmalonyl-CoA pathway

Overexpression of salR2 results in the selective increased production of the chlorinated anticancer agent salinosporamide A

Acknowledgments

We kindly thank B. Gust and Plant Bioscience Limited for providing the REDIRECT© technology kit for PCR-targeting, A. Lapidus from the Joint Genome Institute for sal fosmids, and W. Fenical and P. R. Jensen for the S. tropica strain. Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (CA127622) to B.S.M., the GeneChip Microarray Core (Veterans Medical Research Foundation) for providing preliminary 454 sequencing data, the Albert and Anneliese Konanz Foundation, Mannheim, for a graduate fellowship to A.L., the DAAD for a postdoctoral fellowship to T.A.M.G., and the Life Sciences Research Foundation via a Tularik postdoctoral fellowship to A.S.E.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antunes L, Ferreira R, Lostroh C, Greenberg E. A mutational analysis defines Vibrio fischeri LuxR binding sites. Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190:4392. doi: 10.1128/JB.01443-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer LL, Moore BS. Biosynthetic convergence of salinosporamides A and B in the marine actinomycete Salinispora tropica. Org Lett. 2007;9:845–848. doi: 10.1021/ol063102o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb MJ, Janssen GR, Ward JM. Cloning and analysis of the promoter region of the erythromycin resistance gene (ermE) of Streptomyces erythraeus. Gene. 1985;38:215–226. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb MJ, White J, Ward JM, Janssen GR. The mRNA for the 23S rRNA methylase encoded by the ermE gene of Saccharopolyspora erythraea is translated in the absence of a conventional ribosome-binding site. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:533–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NL, Stoyanov JV, Kidd SP, Hobman JL. The MerR family of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:145–163. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes P, Till R, Bee S, Smith MC. The streptomyces genome contains multiple pseudo-attB sites for the (phi)C31-encoded site-specific recombination system. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5746–5752. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.20.5746-5752.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer A, Eikmanns BJ. RamA, the transcriptional regulator of acetate metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum, is subject to negative autoregulation. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;12:51–59. doi: 10.1159/000096459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine JH, Shadel GS, Baldwin TO. Identification of the operator of the lux regulon from the Vibrio fischeri strain ATCC7744. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5688–5692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustáquio AS, McGlinchey RP, Liu Y, Hazzard C, Beer LL, Florova G, Alhamadsheh MM, Lechner A, Kale AJ, Kobayashi Y, et al. Biosynthesis of the salinosporamide A polyketide synthase substrate chloroethylmalonyl-CoA from S-adenosyl-L-methionine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12295–12300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901237106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustáquio AS, Nam SJ, Penn K, Lechner A, Wilson MC, Fenical W, Moore BS. The discovery of salinosporamide K from the marine bacterium “Salinispora pacifica” by genome mining gives insight into pathway evolution. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:61–64. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustáquio AS, Pojer F, Noel JP, Moore BS. Discovery and characterization of a marine bacterial SAM-dependent chlorinase. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:69–74. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenical W, Jensen PR, Palladino MA, Lam KS, Lloyd GK, Potts BC. Discovery and development of the anticancer agent salinosporamide A (NPI-0052) Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:2175–2180. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Mistry J, Tate J, Coggill P, Heger A, Pollington JE, Gavin OL, Gunasekaran P, Ceric G, Forslund K, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP. Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annual Review of Genetics. 2001;35:439–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua WC, Winans SC, Greenberg EP. Quorum sensing in bacteria: the LuxR-LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:269–275. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.269-275.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, Mack TR, Stock AM. Bacterial response regulators: versatile regulatory strategies from common domains. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groll M, Huber R, Potts BCM. Crystal structures of salinosporamide A (NPI-0052) and B (NPI-0047) in complex with the 20S proteasome reveal important consequences of beta-lactone ring opening and a mechanism for irreversible binding. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5136–5141. doi: 10.1021/ja058320b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulder TAM, Moore BS. Salinosporamide natural products: Potent 20S proteasome inhibitors as promising cancer chemotherapeutics. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:9346–9367. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust B, Challis GL, Fowler K, Kieser T, Chater KF. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1541–1546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337542100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Haydock SF, Spiteller D, Mironenko T, Li TL, O’Hagan D, Leadlay PF, Spencer JB. The gene cluster for fluorometabolite biosynthesis in Streptomyces cattleya: a thioesterase confers resistance to fluoroacetyl-coenzyme A. Chem Biol. 2006;13:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber FM, Pieper RL, Tietz AJ. The formation of daptomycin by supplying decanoic acid to Streptomyces roseosporus cultures producing the antibiotic complex A21978C. Journal of Biotechnology. 1988;7:283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings MI. Advances in Applied Microbiology. Academic Press; 2007. Unusual Two Component Signal Transduction Pathways in the Actinobacteria; pp. 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jez JM, Ferrer JL, Bowman ME, Dixon RA, Noel JP. Dissection of malonyl-coenzyme A decarboxylation from polyketide formation in the reaction mechanism of a plant polyketide synthase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:890–902. doi: 10.1021/bi991489f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale AJ, McGlinchey RP, Moore BS. Characterization of 5-chloro-5-deoxy-D-ribose 1-dehydrogenase in chloroethylmalonyl coenzyme A biosynthesis: substrate and reaction profiling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:33710–33717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.153833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. John Innes Foundation; Norwich, United Kingdom: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Bai L, Deng Z, Zhong JJ. Enhanced production of ansamitocin P-3 by addition of isobutanol in fermentation of Actinosynnema pretiosum. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:1863–1868. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.09.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Tian Y, Yang H, Tan H. A pathway-specific transcriptional regulatory gene for nikkomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces ansochromogenes that also influences colony development. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1855–1866. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Reynolds KA. Role of crotonyl coenzyme A reductase in determining the ratio of polyketides monensin A and monensin B produced by Streptomyces cinnamonensis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6806–6813. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6806-6813.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Hazzard C, Eustáquio AS, Reynolds KA, Moore BS. Biosynthesis of salinosporamides from alpha, beta-unsaturated fatty acids: Implications for extending polyketide synthase diversity. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10376–10377. doi: 10.1021/ja9042824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombo F, Brana AF, Mendez C, Salas JA. The mithramycin gene cluster of Streptomyces argillaceus contains a positive regulatory gene and two repeated DNA sequences that are located at both ends of the cluster. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:642–647. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.642-647.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomovskaya N, Doi-Katayama Y, Filippini S, Nastro C, Fonstein L, Gallo M, Colombo AL, Hutchinson CR. The Streptomyces peucetius dpsY and dnrX genes govern early and late steps of daunorubicin and doxorubicin biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2379–2386. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2379-2386.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macherla VR, Mitchell SS, Manam RR, Reed KA, Chao TH, Nicholson B, Deyanat-Yazdi G, Mai B, Jensen PR, Fenical W, et al. Structure-activity relationship studies of salinosporamide A (NPI-0052), a novel marine derived proteasome inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3684–3687. doi: 10.1021/jm048995+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddocks SE, Oyston PCF. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology. 2008;154:3609–3623. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín JF, Liras P. Engineering of regulatory cascades and networks controlling antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2010;13:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel TJ, Nelson DM, Brauer CL, Kadner RJ. Promoter elements required for positive control of transcription of the Escherichia coli uhpT gene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2763–2770. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2763-2770.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers PR, Bourn WR, Steyn LM, van Helden PD, Beyers AD, Brown GD. Novel method for rapid measurement of growth of mycobacteria in detergent-free media. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2752–2754. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2752-2754.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TJ, Nodwell JR. Pivotal roles for the receiver domain in the mechanism of action of the response regulator RamR of Streptomyces coelicolor. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:1030–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts BC, Albitar MX, Anderson KC, Baritaki S, Berkers C, Bonavida B, Chandra J, Chauhan D, Cusack JCJ, Fenical W, et al. Marizomib, a proteasome inhibitor for all seasons: preclinical profile and a framework for clinical trials. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:254–284. doi: 10.2174/156800911794519716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsawat N, Kitani S, Kinoshita H, Lee C, Nihira T. Identification of the bkdAB gene cluster, a plausible source of the starter-unit for virginiamycin M production in Streptomyces virginiae. Archives of Microbiology. 2007;187:459–466. doi: 10.1007/s00203-007-0212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachid S, Huo L, Herrmann J, Stadler M, Kopcke B, Bitzer J, Muller R. Mining the cinnabaramide biosynthetic pathway to generate novel proteasome inhibitors. Chembiochem. 2011;12:922–931. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz D, Salinas P, Lopez-Redondo ML, Cayuela ML, Marina A, Contreras A. Phosphorylation-independent activation of the atypical response regulator NblR. Microbiology. 2008;154:3002–3015. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell D. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2001. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schar J, Sickmann A, Beier D. Phosphorylation-independent activity of atypical response regulators of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:3100–3109. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.3100-3109.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebenberg S, Bapat PM, Lantz AE, Gust B, Heide L. Reducing the variability of antibiotic production in Streptomyces by cultivation in 24-square deepwell plates. J Biosci Bioeng. 2009;109:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.08.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe HM, Wilson SE, Smith MC. Control of directionality in the site-specific recombination system of the Streptomyces phage phiC31. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:232–241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Fowler K, Findlay K, Tan H, Chater KF. An Unusual Response Regulator Influences Sporulation at Early and Late Stages in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2873–2885. doi: 10.1128/JB.01615-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillett D, Burns BP, Neilan BA. Optimized rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) for mapping bacterial mRNA transcripts. Biotechniques. 2000;28:448, 450, 452–443, 456. doi: 10.2144/00283st01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vara J, Lewandowska-Skarbek M, Wang YG, Donadio S, Hutchinson CR. Cloning of genes governing the deoxysugar portion of the erythromycin biosynthesis pathway in Saccharopolyspora erythraea (Streptomyces erythreus) J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5872–5881. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.5872-5881.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner N, Osswald C, Biener R, Schwartz D. Comparative analysis of transcriptional activities of heterologous promoters in the rare actinomycete Actinoplanes friuliensis. J Biotechnol. 2009;142:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JB, Pan HX, Tang GL. Production of doramectin by rational engineering of the avermectin biosynthetic pathway. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:3320–3323. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Tian X, Wang J, Yang H, Fan K, Xu G, Yang K, Tan H. Autoregulation of antibiotic biosynthesis by binding of the end product to an atypical response regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8617–8622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900592106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.