Most plant cell wall polysaccharides are O-acetylated. However, the acetyltransferases were elusive. Using a forward genetic approach, a putative xyloglucan O-acetyltransferase has now been identified in an unexpected gene family. This opens up future research into the identification of other O-acetyltransferases and the elucidation of the molecular mechanism of polysaccharide O-acetylation.

Abstract

In an Arabidopsis thaliana forward genetic screen aimed at identifying mutants with altered structures of their hemicellulose xyloglucan (axy mutants) using oligosaccharide mass profiling, two nonallelic mutants (axy4-1 and axy4-2) that have a 20 to 35% reduction in xyloglucan O-acetylation were identified. Mapping of the mutation in axy4-1 identified AXY4, a type II transmembrane protein with a Trichome Birefringence-Like domain and a domain of unknown function (DUF231). Loss of AXY4 transcript results in a complete lack of O-acetyl substituents on xyloglucan in several tissues, except seeds. Seed xyloglucan is instead O-acetylated by the paralog AXY4like, as demonstrated by the analysis of the corresponding T-DNA insertional lines. Wall fractionation analysis of axy4 knockout mutants indicated that only a fraction containing xyloglucan is non-O-acetylated. Hence, AXY4/AXY4L is required for the O-acetylation of xyloglucan, and we propose that these proteins represent xyloglucan-specific O-acetyltransferases, although their donor and acceptor substrates have yet to be identified. An Arabidopsis ecotype, Ty-0, has reduced xyloglucan O-acetylation due to mutations in AXY4, demonstrating that O-acetylation of xyloglucan does not impact the plant’s fitness in its natural environment. The relationship of AXY4 with another previously identified group of Arabidopsis proteins involved in general wall O-acetylation, reduced wall acetylation, is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The cells of higher plants are encased in a composite material, the cell wall, consisting of structurally complex polymers, including numerous polysaccharides, the polyphenol lignin, and glycoproteins. Many of the wall polymers contain O-acetyl substituents, including the hemicelluloses xyloglucan (XyG) (Kiefer et al., 1989), (glucurono-)arabinoxylans (Carpita, 1996; Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010), and (galacto-)glucomannans, which occur in the secondary walls of gymnosperms (Lundqvist et al., 2002) and function as storage polymers (Gille et al., 2011), as well as various pectic polysaccharides (Caffall and Mohnen, 2009) and the polyphenol lignin (Del Río et al., 2007).

The biological function of the O-acetyl substituents in the wall is not known and might vary from polymer to polymer. Analysis of O-acetyl substituents indicates that the degree of O-acetylation changes in various plant tissues and during plant development (Liners et al., 1994; Obel et al., 2009), suggesting an important functional role in the plant. In vitro polymer experiments demonstrate that the O-acetyl groups increase the solubility of polymers such as mannans and pectins in aqueous solutions (Rombouts and Thibault, 1986; Nishinari et al., 1992), thus changing the rheological properties of the polymer. Furthermore, O-acetyl substituents hinder enzymatic breakdown of the polymer, as has been demonstrated for XyG (Pauly, 1999) and xylans (Biely et al., 1986).

Plant cell wall polymer O-acetylation has recently received increased attention, as plant cell walls are considered a renewable resource that could be exploited for the production of biofuels (Pauly and Keegstra, 2008; Carroll and Somerville, 2009). O-acetyl groups can reduce saccharification yields of biomass if not removed by pretreatments (Selig et al., 2009). More importantly, the acetate released during pretreatment of plant biomass has adverse effects on downstream processes in biofuel production, as it is an inhibitor of some sugar-to-ethanol fermenting organisms, such as yeast (Helle et al., 2003). Hence, a current goal of plant biofuel research is to reduce the O-acetate content of cell wall polymers in potential biofuel feedstocks. Techno-economic models predict that a 20% reduction in biomass O-acetylation could lead to a 10% reduction in ethanol price (Klein-Marcuschamer et al., 2010), a significant saving in production costs.

Unfortunately, little is known about the molecular mechanism that leads to plant wall polysaccharide O-acetylation. Biochemically, it has been shown that when intact plant microsomes are fed acetyl-CoA, the acetyl group is transferred to the various polysaccharides (Pauly and Scheller, 2000), indicating that acetyl-CoA is a donor substrate and that the endomembrane system, most likely the Golgi apparatus, where the various noncellulosic cell wall polymers are synthesized, is the place of polymer O-acetylation (Moore et al., 1986; Scheible and Pauly, 2004). Recently, an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant has been identified with reduced wall acetylation (rwa; Manabe et al., 2011). Only one of the single knockout mutants (rwa2) shows a reduction in overall wall O-acetylation of 17% in leaf tissue (Manabe et al., 2011), while the quadruple RWA knockout mutant has a reduction in overall wall O-acetylation of up to 42% in its inflorescence stem (Lee et al., 2011). A more detailed analysis of the acetylation status in the rwa2 single mutant indicated that several polysaccharides are affected, including pectins, xylans, and XyG (Manabe et al., 2011). Hence, RWA proteins are not considered to be polymer-specific O-acetyltransferases but accessory proteins that might act on O-acetyl intermediaries. However, the precise role and activity of RWAs in plant polysaccharide O-acetylation has yet to be shown; therefore, the mechanism of polysaccharide O-acetylation remains enigmatic.

In this study, we show that a protein family other than the RWA family is involved in polysaccharide O-acetylation. We demonstrate the role of this class of proteins on XyG, the major hemicellulose in dicotelydons such as Arabidopsis (Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010). XyG consists of a β-4-linked glucan backbone, which is substituted in a regular pattern with xylosyl residues. A one-letter code nomenclature system abbreviates unsubstituted glucosyl residues with a “G,” while Xyl-substituted glucosyl residues are termed “X” (Fry et al., 1993). In Arabidopsis, the xylosyl residues can be further substituted with galactosyl residues (“L”), which in turn can carry additional fucosyl residues (“F”). In Arabidopsis, the O-acetyl substituent is exclusively attached to the galactosyl residue (i.e., it occurs only in the “L” or “F” side chains, mainly on the O-6 position) (Kiefer et al., 1989). Here, an Arabidopsis mutant with reduced XyG O-acetylation levels (axy4), identified through a forward genetic screen that was facilitated by XyG oligosaccharide mass profiling (OLIMP) (Lerouxel et al., 2002; Neumetzler, 2010; Günl et al., 2011; http://paulylab.berkeley.edu/axy-mutants.html), was characterized. The mapping of the underlying mutation led to the identification of AXY4, which is a member of the plant-specific Trichome Birefringence-Like (TBL) protein family (Bischoff et al., 2010a). We propose that AXY4 represents a XyG-specific O-acetyltransferase, as lack of AXY4 transcript leads to a complete lack of O-acetyl-substituents only on XyG.

RESULTS

Characterization of an Arabidopsis Mutant with Reduced XyG O-Acetylation (axy4)

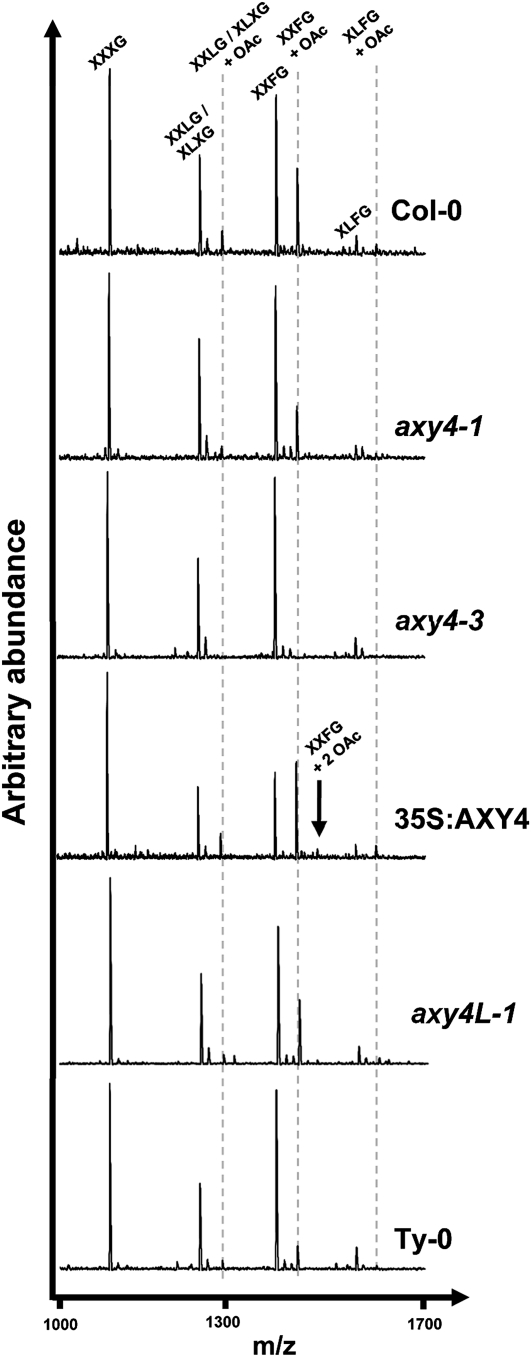

When XyG is solubilized from Arabidopsis walls with a xyloglucanase and assessed by OLIMP, only the ions representing XLXG (or its structural isomer XXLG), XXFG, and XLFG are observed to have the +42 D mass adduct representing their corresponding O-acetylated oligosaccharides (Figure 1, Columbia-0 [Col-0]). Taking into account that only these galactosylated oligosaccharides harbor O-acetylation sites, the percentage of O-acetylated XyG oligosaccharides in Arabidopsis etiolated seedlings is 26% (see Supplemental Table 1 online; Col-0). One hundred percent would mean that all galactosylated XyG oligosaccharides would be completely O-acetylated; in other words, only ions representing XXLG/XLXG + OAc (mass-to-charge ratio [m/z] = 1289), XXFG + OAc (m/z = 1435), and XLFG + OAc (m/z = 1597) would be present and not their nonacetylated counterparts (m/z = 1247, 1393, and 1555).

Figure 1.

XyG OLIMP Spectra Derived from Cell Walls of Etiolated Seedlings.

XyG oligosaccharides were released from AIRs of wild-type Col-0, axy4-1, axy4-3 (SALK_044972), and 35S:AXY4 in Col-0, axy4like-1 (SALK_039548), and the ecotype Ty-0 seedlings. XyG oligosaccharides were identified based on their mass and annotated according to the one letter code described by Fry et al. (1993). O-acetylated XyG oligosaccharides are marked by a dashed line.

When an ethyl methanesulfonate–mutagenized Arabidopsis etiolated seedling population was screened by OLIMP for mutants with altered XyG profiles (axy mutants), axy4-1 and axy4-2 were identified, showing a XyG O-acetylation reduction of 24 and 35%, respectively, compared with the Col-0 wild type (Figures 1 and 2A; see Supplemental Table 1 online). However, genetic and phenotypic characterization of an axy4-1/axy4-2 cross indicated that those mutants were not allelic (see Supplemental Table 1 online); thus, the causative mutations are in different genes, both affecting XyG acetylation. In this study, axy4-1 was analyzed and characterized in detail.

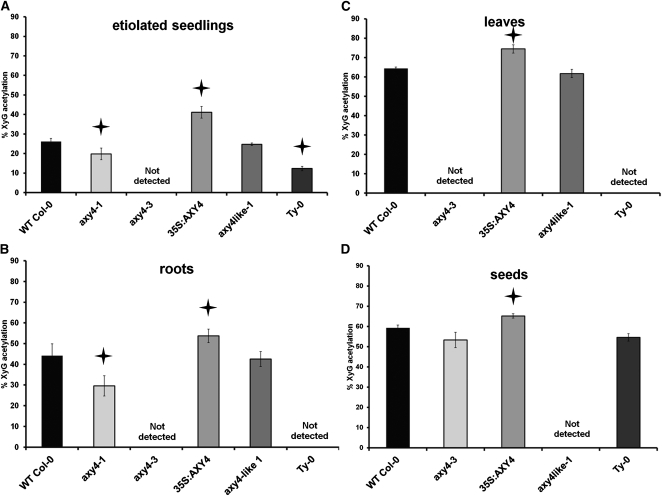

Figure 2.

Percentage of XyG O-Acetylation.

XyG oligosaccharides were released from AIR of selected wild-type Col-0, mutant, and Ty-0 plant tissues and analyzed by OLIMP (see Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 5 online). The percentage of XyG O-acetylation is calculated based on the highest possible degree of XyG O-acetylation, taking only XyG oligosaccharides into account with O-acetylation sites (i.e., oligosaccharides that contain galactosyl residues; see Supplemental Table 1 online). The error bars represent the sd, n = 5; stars indicate a significant difference to the wild type (P ≤ 0.01).

(A) Seven-day-old etiolated seedlings.

(B) Three-week-old roots. WT, wild type.

(C) Five-week-old rosette leaves.

(D) Dry seeds.

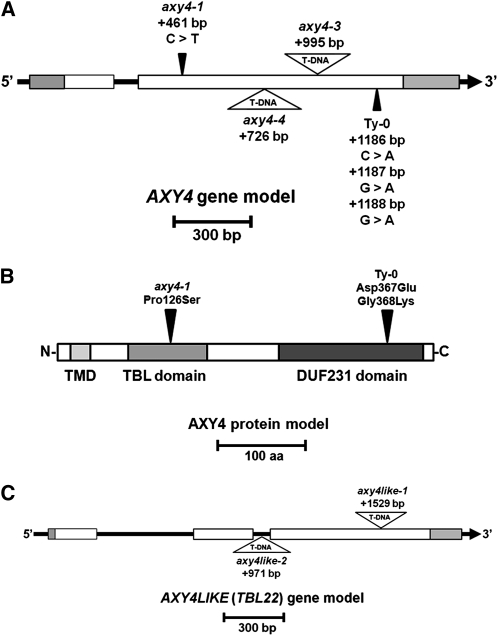

Root tissue of axy4-1 has an even more pronounced reduction in XyG O-acetylation (30% versus 44% for the wild type; Figure 2B; see Supplemental Table 1 online). Hence, the XyG phenotype in root tissue was used to identify the location of the underlying mutation in axy4-1. For mapping purposes, an F2 mapping population of axy4-1 (Col-0 background) crossed with the Arabidopsis ecotype Landsberg erecta (Ler) was established. Rough mapping was performed by microarray-based bulk segregant analysis, narrowing the location of the mutation to a 3-Mb section on the distal arm of chromosome 1 (see Supplemental Figure 1A online). The entire genome of axy4-1 was sequenced using Illumina Solexa deep sequencing, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were called in the 3-Mb rough mapping region that lead to amino acid changes in the encoded proteins of that region. Only 15 genes were affected in axy4-1 (see Supplemental Table 2 online). Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion lines of these 15 genes were obtained from stock centers and their etiolated seedlings analyzed by XyG OLIMP. Only the line carrying a T-DNA inserted in At1g70230 (SALK_044972, termed axy4-3) (Figure 3A) exhibited an alteration in XyG O-acetylation; namely, no O-acetylated XyG oligosaccharides were detectable in the OLIMP spectra (Figures 1 and 2A; see Supplemental Table 1 online). Another allele with a T-DNA inserted in a different position of At1g70230 (SALK_070873; axy4-4) (Figure 3A) confirmed the absence of XyG O-acetylation (see Supplemental Table 1 online). Both axy4 alleles can be described as knockout lines, as RT-PCR demonstrated a lack of the AXY4 transcript (see Supplemental Figure 1B). Together with the Solexa-determined SNP in axy4-1, which leads to a Pro126Ser amino acid exchange in At1g70230 (see Supplemental Table 2 online; Figure 3B), unambiguous evidence is provided that this locus is responsible for the observed effect on XyG O-acetylation; hence, the encoded protein was termed AXY4. Further genetic evidence is provided by transforming Arabidopsis Col-0 lines with a vector construct that overexpresses AXY4 under the control of a 35S promotor. In this plant line (35S:AXY4), XyG acetylation exceeds wild-type levels by 10 to 57%, depending on the tissue (Figures 1 and 2; see Supplemental Table 1 online). In etiolated seedlings, an ion could be observed in the OLIMP spectra that is consistent with XXFG containing two O-acetyl groups (Figure 1); this phenomenon has not been reported in wild-type Arabidopsis XyG. Thus, it seems that a single protein (AXY4) is sufficient to acetylate the galactosyl residue on multiple positions. None of the various axy4 alleles (i.e., the weak axy4-1 allele, the axy4-3 and axy4-4 knockout alleles, and the AXY4 overexpression line) displayed any significant change in other XyG side-chain substitutions, such as galactosylation or fucosylation (see Supplemental Table 1 online; all L and all F).

Figure 3.

Gene and Protein Model of AXY4/TBL27 and AXY4L/TBL22.

(A) Gene model of AXY4 (TBL27). Gray boxes mark the untranslated regions, and white boxes indicate coding exons. Black triangles mark the position of the axy4-1 SNP and the SNPs in the Ty-0 ecotype. Open triangles mark the position of the T-DNA insertion sites of axy4-3 (SALK_044972) and axy4-4 (SALK_070873) mutants. The positions of the mutations are counted from the ATG start codon.

(B) Protein model of AXY4/TBL27. The light-gray box indicates the position of the predicted transmembrane domain (TMD). The medium-gray and dark-gray boxes mark the TBL and DUF231 domains according to Bischoff et al. (2010a), respectively. Black triangles mark the position of the axy4-1 and Ty-0 amino acid changes.

(C) Gene model of AXY4L (TBL22; Bischoff et al., 2010a). Gray boxes mark the untranslated regions, and white boxes indicate coding exons. Open triangles mark the position of the T-DNA insertion sites of the axy4like-1 (SALK_039548) and axy4like-2 (SALK_083841) mutants. The positions of the mutations are counted from the ATG start codon.

To elucidate if the O-acetylation level of wall polymers other than XyG is affected, cell walls (alcohol-insoluble residue [AIR]) from the rosette leaves of the wild type and the two axy4 knockout alleles were sequentially extracted with an aqueous buffer to yield buffer-soluble proteins and polysaccharides. The residue was then digested first with a combination of an endopolygalacturonase and pectin methylesterase, which solubilize pectins, followed by xyloglucanase, to release XyG. The remaining pellet should mainly contain (O-acetylated) xylan and mannan besides nonacetylated cellulose. The acetate content of each of these fractions was determined after alkali release and demonstrated that only the O-acetylation of XyG was affected in the mutants, which was accompanied by a near complete absence of acetate in this xyloglucanase released fraction (Table 1). The residual 5 to 10% acetate in the axy4 mutants compared with the wild type in the xyloglucanase released fraction is not derived from XyG as previously shown by OLIMP (Figure 1) but is likely contamination of other cosolubilized polymers. To address if the O-acetylation status of xylan and/or mannan is affected in the axy4 mutant, the walls of 5-week-old Arabidopsis stems, which are rich in these two hemicelluloses, were characterized. OLIMP analysis demonstrated again that XyG lacks O-acetate in both axy4 knockout lines (see Supplemental Table 1 online). The stem wall was dissolved in an organic solvent and subjected to two-dimensional heteronuclear single quantum coherence (2D HSQC) NMR spectroscopy. The polysaccharide regions of the acquired NMR spectra from the wild type and the two axy4 knockout mutants showed signals originating from acetylated mannan and xylan (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). Quantification of the specific signals indicated that the acetylation status of xylan and mannan in the stem tissues of the axy4 knockout mutants is not altered compared with the wild type, either in terms of degree of O-acetylation or in terms of O-acetyl position (see Supplemental Figure 2 online).

Table 1.

Acetic Acid Content of Total Cell Wall and Sequentially Extracted Cell Wall Fractions from 5-Week-Old Rosette Leaves of the Wild Type and Two Knockout Mutants

| Polymer-Bound Acetic Acid Content (ng/mg Dry Weight Used in Extraction) | |||||

| Lines | Total AIR | Buffer Wash | PME/ePG Digest | Xyloglucanase Digest | Pellet |

| Wild-type Col-0 | 7762.03 ± 244.26 | 859.76 ± 84.92 | 2956.49 ± 56.12 | 209.57 ± 5.19 | 3306.95 ± 102.91 |

| axy4-3 | 7390.05 ± 229.06 | 774.28 ± 36.66 | 2875.23 ± 226.34 | 12.56 ± 42.07 | 3357.29 ± 238.87 |

| axy4-4 | 7322.94 ± 201.35 | 851.33 ± 21.68 | 2988.52 ± 102.96 | 23.93 ± 42.61 | 3291.11 ± 187.22 |

ePG, endopolygalacturonase; PME, pectin methylesterase. Data are ± sd, and significant differences (P ≤ 0.01) are displayed in bold (n = 3).

The subcellular localization of AXY4 was investigated by fusing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the C terminus of AXY4, placing the chimera gene under the control of a 35S promoter, transiently expressing it in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) epidermal cells, and monitoring its location by fluorescence microscopy (see Supplemental Figure 3 online). The AXY4:GFP fusion protein colocalized with a mannosidase fused to a cyan fluorescent protein (CFP), which was previously shown to localize to the Golgi (Nelson et al., 2007), indicating that, under these experimental conditions, AXY4 localizes to the Golgi. AXY4 is a typical type II transmembrane protein with a predicted transmembrane domain at its N terminus (Figure 3B). Further analyses using membrane topology prediction algorithms suggest that the short N-terminal part of the protein faces the cytoplasm, while the larger C-terminal part containing conserved domains (Figure 3B) resides inside the Golgi lumen (TMHMM server 2.0, http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/; Krogh et al. 2001).

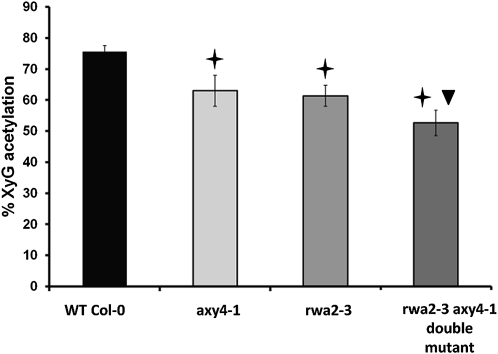

One other protein, RWA2, has been shown to affect XyG acetylation (Lee et al., 2011; Manabe et al., 2011). The XyG O-acetylation level in the leaf of its prominent mutant, rwa2, was 61.3% versus 75.6% in the wild type, a similar level of O-acetylation reduction as in axy4-1 in the same tissue (Figure 4). The relationship between AXY4 and RWA2 was tested genetically. Potential crosses with the knockout lines of AXY4 (either axy4-3 or axy4-4) were considered noninsightful as both mutants completely lack XyG acetylation. Hence, rwa2 was crossed with the weak allele axy4-1. OLIMP analysis of 4-week-old leaves from the resulting double mutant indicated a slight but significant further reduction of XyG O-acetylation to the 52.6% level. However, this reduction is neither additive nor synergistic, suggesting that RWA2 partially acts in the same XyG O-acetylation pathway but that its function might be compensated for by one of the other redundant RWA proteins (Manabe et al., 2011).

Figure 4.

Percentage of XyG O-Acetylation in the rwa2-3 axy4-1 Double Mutant.

XyG oligosaccharides were released from AIR of 4-week-old leaves from wild-type Col-0, rwa2-3, and axy4-1 single mutants and the rwa2-3 axy4-1 double mutant and analyzed by OLIMP. The percentage of XyG O-acetylation was calculated based on the highest possible degree of XyG O-acetylation, taking only XyG oligosaccharides into account with O-acetylation sites (i.e., oligosaccharides that contain galactosyl residues). A star indicates a significant difference from the Col-0 wild type (WT); a triangle indicates significant difference of the double mutant to both single mutants (P ≤ 0.01). The error bars represent the sd, n = 5.

A Naturally Occurring Ecotype of Arabidopsis Lacks AXY4-Mediated XyG O-Acetylation

A collection of 125 Arabidopsis ecotypes was acquired, and the degree of XyG O-acetylation in etiolated seedlings of each ecotype was determined by OLIMP (see Supplemental Table 3 online). The percentage of XyG O-acetylation ranged from 12% (ecotype Ty-0; Figure 1) to 43% (ecotype Da-0). Interestingly, while the ecotypes could be sorted to display a gradual increase in O-acetylation, with a maximum increase of 1%, Ty-0 was an exception, with an O-acetylation level that was 10% below that of the next ecotype. The low degree of XyG O-acetylation was reminiscent of the axy4 mutants; hence, different tissues of Ty-0 were subjected to OLIMP. As in the axy4 knockout lines, the XyG present in the rosette leaves and roots of Ty-0 was nonacetylated (Figure 2; see Supplemental Table 1 online). It was hypothesized that this phenotype could be caused by a deleterious mutation in AXY4. Sequence analysis of the AXY4 locus in Ty-0 indeed revealed three SNPs in the coding sequence, two of which resulted in two amino acid changes in AXY4 (Figures 3A and 3B). Of the 125 Arabidopsis ecotypes tested here, the full genomes of 88 are available (www.arabidopsis.org). With the exception of Ty-0, none of these ecotypes carries a nonsynonymous mutation in AXY4. To address if the observed XyG acetylation phenotype in Ty-0 is indeed due to the SNPs in AXY4, an allelism test was performed. Indeed, XyG OLIMP analysis of the F1 generation of a cross between Ty-0 and the axy4-3 knockout indicated a lack of XyG O-acetylation in leaves, confirming that Ty-0 contains a naturally occurring allele of AXY4 (see Supplemental Table 1 online).

Identification of axy4like, a Mutant Affected in Seed XyG O-Acetylation

Analysis of OLIMP profiles derived from various tissues of the knockout lines axy4-3 and axy4-4 and Ty-0 indicated the absence of O-acetyl substituents on XyG in roots and rosette leaves (Figures 2A to 2C; see Supplemental Table 1 online), whereas in seeds, the percentage of XyG O-acetylation remained at wild-type (Col-0) levels (Figure 2D; see Supplemental Table 1 online). We hypothesized that a paralog of AXY4 is responsible for O-acetylation of XyG in this tissue. AXY4 is a member of the TBL gene family, previously named TBL27 (The Arabidopsis Information Resource [TAIR], www.arabidopsis.org). T-DNA insertion lines for 10 additional TBL members (TBL17-26, according to TAIR, www.arabidopsis.org) were acquired, and after confirming their T-DNA homozygocity, the seeds of these lines were subjected to XyG OLIMP. For only two of those lines, representing two different alleles of T-DNA insertions in TBL22, a difference in the XyG OLIMP spectra was observed (see Supplemental Figures 4 and 5 online), in that they complete lacked O-acetylated XyG oligosaccharides. The two knockout mutants (see Supplemental Figure 1C online) were termed axy4like-1 (axy4L-1) and axy4like-2 (axy4L-2), respectively, due to their similar effect on XyG O-acetylation as axy4 but their lack of activity in seeds (Figure 2D). Other tissues, such as etiolated seedlings, roots, and rosette leaves of the axy4like mutants, were subjected to XyG OLIMP analysis, indicating that the O-acetylation level in these tissues is not altered (Figures 2A to 2C; see Supplemental Table 1 online). Hence, AXY4 and AXY4L represent two nonredundant proteins that likely have similar roles in XyG O-acetylation in non-seed and seed tissues, respectively.

DISCUSSION

AXY4 and AXY4L Represent XyG O-Acetyltransferases

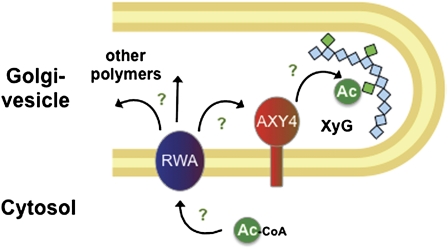

Evidence is presented that AXY4 and its paralog, AXY4L, represent putative XyG O-acetyltransferases. First, eliminating their transcript in the Arabidopsis axy4 and axy4L mutant lines leads to a complete lack of O-acetyl substituents on XyG in non-seed and seed tissues, respectively (Figure 2). Second, based on a cell wall fractionation study on leaves and 2D NMR analysis of stems in axy4 knockout mutants (Table 1; see Supplemental Figure 2 online), only XyG shows a lack in O-acetyl groups, indicating that AXY4 acts XyG specific. Third, overexpressing AXY4 in the Arabidopsis wild type leads to a significant increase in XyG O-acetylation (Figures 1 and 2; see Supplemental Table 1 online). Fourth, a subcellular localization study using a GFP-protein chimera located AXY4 to the Golgi apparatus (see Supplemental Figure 3 online), the site of XyG biosynthesis and polysaccharide O-acetylation mediated by acetyl-CoA (Pauly and Scheller, 2000). Fifth, both enzymes are part of the TBL family (more detailed discussion on this topic below), which contains motifs such as a GDSL motif that is present in esterases or lipases (Akoh et al., 2004; Bischoff et al., 2010a). Hence, AXY4 seems to confer some sort of catalytic activity but probably not an esterase activity (Bischoff et al., 2010b). While these results demonstrate the specificity of the AXY4/AXY4L enzymes toward XyG and their requirement for XyG O-acetylation, the identity of their donor substrate, such as acetyl-CoA or a hitherto unidentified intermediate, and their acceptor substrate, such as XyG directly or an intermediate molecule prior to the acetylation of XyG, remains to be determined (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Model of XyG O-Acetylation.

Acetyl-CoA acts as an acetyl-donor molecule. The acetate is transferred via an unknown mechanism into the Golgi. This could be potentially accomplished by RWA. The acetyl group is then distributed for O-acetylation of various polymers. AXY4/AXY4L, Golgi-anchored proteins, are involved in transfer of the acetyl group specifically to XyG. RWA and AXY4 might form a complex. Note that the form of the acetyl-carrier molecule or potentially additional proteinaceous factors that function between these stages are unknown (green question marks).

The molecular pathway of the acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to polysaccharides has not been elucidated (Pauly and Scheller, 2000). The possibility that acetyl intermediates other than CoA, such as those reported in bacterial systems (Dupont and Clarke, 1991) or in human cells (Diaz et al., 1989; Higa et al., 1989), may play a role in the transacetylation reactions cannot be ruled out. At least one protein other than AXY4 is involved in the acetylation of XyG (i.e., RWA) (Lee et al., 2011; Manabe et al., 2011). This protein was identified based on sequence homology to Cas1p, a protein required for O-acetylation of the capsular polysaccharide glucuronoxylomannan in the microbe Cryptococcus neoformans (Janbon et al., 2001). Localization studies place RWA, like AXY4, in the endomembrane system, although it is debatable whether RWA occurs in the endoplasmatic reticulum (Manabe et al., 2011) or the Golgi apparatus (Lee et al., 2011). Unlike AXY4 and AXY4L, RWA impacts the acetylation of a plethora of polysaccharides besides XyG, including pectins and xylan. This broadband acetylation effect places RWA upstream of AXY4, and both proteins are likely part of the same pathway (Figure 5). Additional hitherto unidentified protein components might play a part in XyG O-acetylation. One example could be encoded by the gene locus responsible for reduced XyG acetylation in axy4-2.

The overexpression of AXY4 gave additional insight into the mechanism of AXY4 activity. AXY4 does not seem to be hindered in its action by other XyG sidechain substitutions, as an increase in O-acetylation was observed in all XyG oligosaccharides, including XXLG and/or XLXG, XXFG, and XLFG, when AXY4 is overexpressed in the wild-type background. However, overexpression of AXY4 does not lead to complete O-acetylation of XyG. One possibility is that a hitherto unknown XyG acetylesterase is responsible for the partial removal of O-acetyl groups (e.g., during a polymer maturation process in the apoplast).

AXY4 and AXY4L Are Members of a Large Protein Family That Is Likely to Include Other Polymer-Specific O-Acetyltransferases

AXY4 and AXY4L both encode proteins that belong to the large plant-specific family of TBL proteins, in which they are annotated as TBL27 and TBL22 (TAIR, www.arabidopsis.org), respectively. In Arabidopsis, there are 46 members of this family (Trichome Birefringence [TBR]; TBL1-45) (Bischoff et al., 2010a). In addition to the putative transmembrane domain that renders this protein a type II membrane protein, all TBL proteins, including AXY4 and AXY4L, contain two highly conserved domains: a plant-specific TBL domain with 13 fully conserved amino acids, including a Gly-Asp-Ser (GDS) peptide, and the plant-specific C-terminal DUF231 domain (Bischoff et al., 2010a) (Figure 3B). The aforementioned GDS motif in the TBL domain has also previously been described as being a conserved motif in esterases and lipases (Akoh et al., 2004). This raises the question of whether the TBL domain also encodes esterase activity, which might be essential for the activity of AXY4, due to the fact that the described axy4-1 allele features an amino acid change in the TBL domain (Figure 3B) that leads to a reduction in XyG acetylation levels (Figures 1 and 2). Similar to the TBL domain, the DUF231 domain also harbors a conserved motif, DxxH, which is also found in some esterases, including a fungal rhamnoglacturonan acetylesterase (Mølgaard and Larsen, 2004; Bischoff et al., 2010a, 2010b). The DUF231 domain seems to be essential for the function of AXY4, since an amino acid change in this domain also leads to a reduction/complete lack of XyG O-acetylation in the Arabidopsis ecotype Ty-0 (Figures 1 and 3B). Further studies of the exact functions of the two domains are needed through, for example, domain swap complementation experiments to elucidate their involvement in the acetylation of XyG.

Several members of the TBL family have been shown to be involved in cell wall biosynthesis. The protein family is named after the phenotype of trichome birefringence (reflection of polarized light on crystalline cellulose), a phenomenon that is absent in mutants of the first described protein (Arabidopsis TBR) from this family. Mutants of TBR exhibit a reduction in cellulose content in secondary cell walls, which is accompanied by an increase in the amount of pectic polymers, a lower degree of pectin methylesterification, and an increase in pectin methylesterase activity. Similar cell wall phenotypes were observed in mutants of TBL3 (Bischoff et al., 2010a). TBL3 and TBR hypocotyls show a reduction in pectinaceous ester content based on Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. While the authors hypothesized that these data indicate a reduction in methylesters, it is more likely in light of the AXY4/TBL27 and AXY4L/TBL22 data presented here that a reduction in acetyl esters occurs in those walls. A more detailed analysis of the walls of these mutants should clarify this question. Another well-studied member of the TBL family is TBL29, which is also annotated as ESKIMO1 (ESK1). A study by Lefebvre et al. (2011) showed that esk1 mutants are affected in cell wall biosynthesis, specifically in developing xylem. Similar to the tbr and tbl3 mutants (Bischoff et al., 2010a), esk1 mutants display a reduction in crystalline cellulose. It was concluded that ESK1 is likely involved in cell wall deposition, maturation, and/or regulation, resulting in the observed cell wall defects. An additional member of the TBL family, PMR5 (TBL44), was shown to exhibit a strong resistance to the pathogen powdery mildew (Vogel and Somerville, 2000). Although overall changes in cell wall composition of pmr5 mutants were modest, if present at all, Fourier transform infrared analysis suggested that pmr5 cell walls might have a lower degree of pectin methyl-esterification or O-acetylation (Vogel et al., 2004). However, a function of PMR5 (TBL44) has not been shown to date. None of the aforementioned studies of TBL family members analyzed the acetylation levels of the various cell wall polymers in detail. However, in light of the finding that AXY4 and AXY4L are involved in XyG-specific O-acetylation, other members of the TBL protein family are likely to be involved in the specific acetylation of other cell wall polymers.

Focusing on the impact of cell wall polymer acetylation on the generation of lignocellulosic biofuels, we selected the closest AXY4 homologs, TBL17 through TBL26, to identify putative homologous proteins in grasses and woody species, which are likely to be used as feedstocks for future biofuel production. This approach led to the identification of putative homologs for all 11 selected TBLs in poplar (Populus trichocarpa), rice (Oryza sativa), maize (Zea mays), and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) (Figure 6; see Supplemental Data Set 1 online). The cell walls of grasses contain only minor amounts of XyG but large amounts of highly O-acetylated (glucorono-)arabinoxylans (Carpita, 1996). The assembled phylogenetic tree (Figure 6) infers a large clade of TBLs in grasses, which seem to be similar to AXY4. However, in grasses, the glucan backbone of XyG is O-acetylated, and not the side chains as in Arabidopsis. Hence, these proteins in grasses might be involved in the acetylation of polymers other than XyG (e.g., xylan). In any case, the identified proteins in grass species can be used as a starting point for analyzing putative acetyltransferases in grasses, which could potentially lead to biofuel feedstocks with reduced lignocellulosic acetate levels.

Figure 6.

Unrooted, Bootstrapped Tree of TBL Proteins (see Methods).

Putative orthologs from Arabidopsis, P. trichocarpa, O. sativa, Z. mays, and S. bicolor were identified, including AXY4, AXY4like, and a putative mannan O-acetyltransferase based on sequence homology to an A. konjac homolog (see discussion and Gille et al., 2011). Bootstrap values are shown. Arabidopsis TBL family genes were numbered according to TAIR (www.Arabidopsis.org).

Recently, deep sequencing of a developing Amorphophallus konjac corm was undertaken in an attempt to identify genes involved in the biosynthesis of the hemicellulose glucomannan, which can be highly O-acetylated (Gille et al., 2011). Indeed, a contig with the greatest similarity to TBL25 was identified among the top 10 most abundant EST reads in the database (Gille et al., 2011; see Supplemental Table 1 online). Hence, we hypothesize that TBL25 and possibly TBL26, a close paralog in Arabidopsis, might be involved in the O-acetylation of mannan (Figure 6), which is currently being investigated.

The Function of O-Acetylation of XyG in Plants

The biological function of wall polymer O-acetylation is unclear due to the lack of mutants affected in O-acetylation. In the case of XyG acetylation, mutants in AXY4 and AXY4L have now been identified. However, all mutants display wild-type-like growth and development when grown in the growth chambers, despite a complete lack of XyG O-acetylation. In fact, an Arabidopsis accession originating from Taynuilt, Scotland (Ty-0) exhibits a near lack of XyG O-acetylation in a number of tissues. Apparently, an aberration of XyG O-acetylation does not impact the fitness of the plant under the environmental conditions found in this region and thus does not seem to represent a selective disadvantage.

This absence of a visible phenotype is in line with other mutants with altered XyG structures (Madson et al., 2003; Perrin et al., 2003). Indeed, a double mutant (xxt1 xxt2) with nondetectable levels of XyG also displays a normal-looking Arabidopsis plant with the exception of deformed root hairs (Cavalier et al. 2008). Furthermore, the O-acetylation mutant rwa2, which exhibits reduced acetylation levels in various polymers, showed no visible morphological changes (Manabe et al., 2011).

Thus, the biological function of wall polymer O-acetylation remains unclear at this point. Potential hypotheses that remain to be tested include: (1) that O-acetylation results in an in planta change in rheological properties of the polysaccharide and, thus, potentially affects wall architecture, (2) that the O-acetyl substituent is a more energetically favorable substituent (C2 compound) than a C5/C6 compound (monosaccharide), and (3) that an increased recalcitrance to enzymatic degradation and/or increased polymer heterogeneity might affect plant pathogenicity.

However, the finding that AXY4/AXY4L is involved in XyG-specific O-acetylation opens the door to identifying other O-acetyltransferases (most likely TBLs) that modify other cell wall polymers. This should enable us to investigate how polymer O-acetylation contributes to plant growth, development, and pathogen resistance.

METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The axy4-1 mutant had been identified in an ethyl methanesulfonate–induced mutant population of the Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 ecotype (Berger and Altmann, 2000). The mutant was backcrossed three times into the Col-0 background. The T-DNA insertion lines and the 125 Arabidopsis ecotypes were obtained from the ABRC stock center at Ohio State University (Alonso et al., 2003), the Institut Jean-Pierre Bourgin at the Versailles Center of the National Institute for Agronomical Research (Samson et al., 2002), and Bjoern Usadel’s lab at the Technical University Aachen.

Arabidopsis seedlings were grown as described (Gille et al., 2009). In brief, seeds were surface sterilized and grown on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog media plates containing 1% agar (Murashige and Skoog, 1962). For etiolated seedlings, the seeds were sown on the plates, wrapped in aluminum foil, stratified for 1 to 2 days at 4°C, and grown for 7 d in an environmentally controlled growth chamber at 22°C. For root tissues, the seeds were sown on the plates, stratified for 1 to 2 days at 4°C, and grown for 3 weeks in the growth chamber under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) with 130 to 140 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity at 22°C.

For crosses, phenotypic evaluation, and tissue collection, seeds were sown on soil, grown in environmentally controlled growth chambers under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) with a 170 to 190 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity at 22°C, and watered twice a week. Rosette leaves were harvested for OLIMP after 5 weeks of growth, except for the material used for the analyses of the axy4-1 rwa2-3 double mutant, which was harvested after 4 weeks.

OLIMP of XyG

Mass profiling of XyG oligosaccharides derived from various tissues was essentially performed as described by Lerouxel et al. (2002) and shown by Günl et al. (2010) by digesting AIR with a XyG-specific endoglucanase (Pauly et al., 1999). The spectra of the solubilized XyG oligosaccharides were obtained using an Axima matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (Shimadzu) set to linear positive mode with an acceleration voltage of 20,000 V.

Mapping of the axy4-1 Mutation

An F2 mapping population was created by crossing an axy4-1 mutant (background Col-0) with Arabidopsis ecotype Ler. Roots from 3-week-old seedlings of the F2 population were analyzed by OLIMP and assigned a wild-type or axy4 XyG OLIMP phenotype. Genomic DNA was extracted from the leaf tissue of these F2 plants using the DNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal amounts of gDNA from 50 wild-type and 50 axy4 XyG OLIMP-phenotyped F2 plants were pooled and used for a microarray-based bulk segregant analysis to determine Col-0 and Ler allele frequencies as previously described (Borevitz, 2006).

Genomic DNA from axy4-1 leaf tissue was extracted using the DNeasy plant mini kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and a total of 5 μg DNA was subjected to Illumina deep sequencing. The Illumina sequencing was performed by the Michigan State University Research Technology Support Facility Genomics Core using an Illumina Genome Analyzer II. The obtained short sequence reads were assembled using CLC Genomics Workbench version v3.7 (CLC Bio). The assembled sequence was aligned to the Arabidopsis genome (version TAIR9) to identify SNPs.

The mutation in the genetic locus At1g70230 was confirmed by gene sequencing using the primers TBL27seq-fw (5′-ACGCAAGGGAACTGGGTCAGAGACGA-3′) and TBL27seq-rev (5′-AGTAAACCGAGACAGTGACGTTGTGTG-3′).

Genomic DNA from leaves of the Ty-0 ecotype was extracted as described for the axy4-1 mutant above, and the genomic sequence of At1g70230 was PCR amplified using the primers AS-166 (5′-ATTATTGGAAGCTGGTGAGC-3′) and AS-172 (5′-AACGAATGCGATATACCGAG-3′). The PCR product was sequenced, and the resulting sequence was aligned to the Col-0 reference sequence to identify SNPs.

Identification of Homozygous Insertional T-DNA Lines

Homozygous T-DNA lines were identified by PCR using gene- and T-DNA–specific primers (Siebert et al., 1995). Specific primer sequences were obtained using the T-DNA Primer Design tool provided by the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory (http://signal.salk.edu/tdnaprimers.2.html). All primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 4 online.

RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA from 3-week-old seedlings was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and bromchlorpropane as described previously (Chomczynski and Mackey, 1995). The extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT)12–18 primers (both from Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s manual. The presence of the AXY4 transcript was analyzed by PCR using the primers axy4cDNA-fw (5′-ACCGTCTCTAGCCCTGATCTCGTCT-3′) and axy4cDNA-rev (5′-CGCATGTCCAAGTCCAGACCTTCT-3′). The reaction mix contained 2 μL template cDNA, 0.2 μM of the primers, and JumpStart REDTaq ReadyMix (Sigma-Aldrich) in a total volume of 20 μL. The PCR program entailed 95°C, 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C, 30 s; 56°C, 1 min and 30 s; 72°C, 2 min; and a final elongation for 5 min at 72°C. As a control, a second reaction was set up to amplify a fragment of the PTB transcript (Czechowski et al., 2005) using the primers PTB-fw (5′-GCGAATGTCTTATTCAGCTCATACTGATC-3′) and PTB-rev (5′-CATTGCTGCTGTTGGTATATCAGAGT-3′) under the same conditions. The PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel stained with 0.005% ethidium bromide.

Cloning, Overexpression, and Subcellular Localization of AXY4

The coding sequence of AXY4 was identified and synthesized with a 5′ BamHI and 3′ HindIII restriction recognition sites (DNA2.0). The sequence was cloned by restriction and ligation into the binary plant transformation vector pBinAR, which contains a 35S promoter (Hofgen and Willmitzer, 1990). The resulting 35S:AXY4 construct was amplified in Escherichia coli, transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, and subsequently transformed by floral dip (Clough and Bent, 1998) into Arabidopsis Col-0 and axy4-3 mutant plants. Positive transformants were identified by selection on kanamycin (60 μg/mL) in the T1 generation, and homozygous transformants were selected by kanamycin resistance segregation in the T2 generation.

For the analysis of the subcellular localization of AXY4, the coding sequence was PCR amplified from the synthesized product without the stop codon using the primers axy4GFP-fw (5′-ATGGGATTAAACGAGCAACAAAATGT-3′) and axy4GFP-rev (5′-AACCTTCCATCGCCGCAACATCT-3′). The resulting PCR product was cloned by TOPO-TA cloning into the vector pCR8/GW using the Invitrogen TOPO-TA pCR8/GW cloning kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The AXY4 coding sequence without stop codon was subcloned via the Gateway LR reaction into the vector pMDC83 (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003) using the LR clonase II enzyme (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The resulting 35S:AXY4:GFP construct was amplified in E. coli and transformed into Agrobacterium strain GV3101. For transient expression of the fusion protein, 4- to 5-week-old Nicotiana benthamiana plant leaves were transformed by Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer as described by Sparkes et al. (2006). The leaves were cotransformed with pG-ck construct containing a 35S:Mannosidase:CFP sequence as a Golgi apparatus marker (Nelson et al., 2007). The transformed leaf sections were excised 2 d after infiltration and analyzed by confocal microscopy using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss). The CFP and GFP fluorophors were excited using an argon laser at 405 and 488 nm, respectively. Fluorescence was detected using a 454- to 481-nm band-pass filter for CFP and a 504- to 598-nm band-pass filter for GFP.

Cell Wall Fractionation and Determination of Wall-Bound Acetate Content

Total cell wall material was extracted as described previously (Gille et al., 2009). Freeze-dried 5-week-old rosette leaves were ground to a fine powder using a ball mill (Retsch). Buffer-soluble components were extracted by overnight incubation of the ground material in 50 mM ammonium formate buffer, pH 4.5, at 37°C while shaking at 250 rpm. The extract was separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 20,817 rcf. The remaining pellet was washed three times with 1 mL of water. The water washes were pooled with the ammonium formate extract. The remaining pellet was digested with a mixture of 0.02 units of pectin methylesterase (EC3.1.1.11; Novozymes) and 1 unit of endopolygalacturonanase M2 (EC3.2.1.15; Megazyme) in 1 mL of 50 mM ammonium formate buffer, pH 4.5, for 18 h at 37°C. After incubation, the enzymes were heat inactivated for 10 min at 100°C. The supernatant containing solubilized pectic components was separated by centrifugation and combined with subsequent water washes as described above. The remaining pellet was digested with 8 units of a XyG-specific endoglucananse (Pauly et al., 1999) in 1 mL of 50 mM ammonium formate buffer, pH 4.5, for 18 h at 37°C. After incubation, the enzyme was heat inactivated for 10 min at 100°C. The supernatant containing solubilized XyG oligosaccharides was separated by centrifugation and combined with subsequent water washes as described above. The extracted fractions and the remaining pellet were freeze-dried.

The wall-bound acetate content of total cell wall, sequentially extracted fractions, and remaining final pellet was determined using the Megazyme Acetic Acid Kit. The assay was downscaled and adapted to a 96-well format as previously described (Gille et al., 2011).

HSQC-NMR Spectroscopy

The NMR characterization of Arabidopsis stem material (the wild type, axy4-3, and axy4-4) was performed with minor modifications, essentially as described (Yelle et al., 2008; Kim and Ralph, 2010). In brief, ~200 mg AIR of Arabidopsis stems was ground for 6 h (5 min grinding and 5-min break intervals) in a Retsch PM 100 planetary ball mill. The ground residue (25 mg) was dissolved in 0.75 mL deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6, D, 99%; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) supplemented with 1.5% (w/w) 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate (EMIM-Ac, 97%; Sigma-Aldrich). The 2D HSQC-NMR spectra of the prepared solutions were acquired at 318K on a Bruker Avance 600-MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with an inverse (proton coils closest to the sample) gradient 5-mm TXI 1H/13C/15N CryoProbe. The Bruker standard pulse sequence hsqcetgpsisp.2 was used to determine the one-bond 13C-1H correlation in plant cell walls. The following parameters were applied in the experiments: spectra width 16 ppm (o1p = 7.0 ppm) in F2 (1H) dimension with 2048 data points and 240 ppm (o2p = 90 ppm) in F1 (13C) dimension with 256 data points; scan number of 128; dummy scans 2; interscan delay (D1) of 1 s; prescan delay (DW) of 6.0 μs; receiver gain of 46,341. The spectra were calibrated by the DMSO solvent peak (δC 39.9 ppm and δH 2.49 ppm). The NMR data processing and analysis were performed using Bruker’s Topspin 3.1 software.

Phylogenetic Analysis of AXY4/TBL Proteins in Other Species

Based on a previously published phylogenetic analysis (Bischoff et al., 2010a), TBL17 through TBL27 (AXY4) were selected and the respective protein sequences were obtained from TAIR (www.arabidopsis.org). The protein sequences were aligned to the available proteomic sequences of Populus trichocarpa, Oryza sativa, Zea mays, and Sorghum bicolor using BLASTP 2.2.25+ (Altschul et al., 1997) and putative orthologous proteins in these species were identified. The obtained protein sequences were used for a phylogenetic analysis. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1000 replicates (Felsenstein, 1985) is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analyzed. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method (Zuckerkandl and Pauling, 1965) and are in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated from the data set (complete deletion option). There were a total of 83 positions in the final data set. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA4 using default parameters (Tamura et al., 2007).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: AXY4/TBL27, At2g70230; AXY4L/TBL22, At3g28150; TBL25, At1g01430; and PTB, At3g01150.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Microarray Mapping of the axy4-1 Mutation and Transcript Levels of AXY4 and AXY4L.

Supplemental Figure 2. Polysaccharide Regions of the 2D HSQC NMR Spectra of Arabidopsis Stems (the Wild Type, axy4-3, and axy4-4).

Supplemental Figure 3. Subcellular Localization of the 35S:AXY4:GFP Fusion Protein.

Supplemental Figure 4. Percentage of XyG Acetylation in Seeds of Selected TBL Lines.

Supplemental Figure 5. XyG OLIMP Spectra Dervied from Cell Walls of Arabidopsis Seeds.

Supplemental Table 1. Relative Abundance of XEG-Released XyG Oligosaccharides in Different Tissues of Col-0, Mutant, and Ty-0 Plants.

Supplemental Table 2. Detected Nonsynonymous Single Nucleotide Polymorphism in the Genomic Region Mapped by Bulk Segregant Analysis.

Supplemental Table 3. Percentage of XyG Oligosaccharide O-Acetylation in 125 Arabidopsis Ecotypes Based on XyG OLIMP.

Supplemental Table 4. Primer Sequences Used for the Identification of Homozygous T-DNA Insertion Lines.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Sequences Used to Generate the Phylogeny Presented in Figure 6.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kirk Schnorr (Novozymes, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) for the generous gift of the xyloglucanase and the pectin methylesterase and Bjoern Usadel (Technical University Aachen, Germany) for seeds of some of the Arabidopsis ecotypes. We also thank Eddie Lam, Michell Huynh, and Miranda Lyons-Cohen (all of the University of California, Berkeley, CA) for excellent technical support. This work was supported by Award OO0G01 from the Energy Biosciences Institute, the Fred Dickinson Chair of Wood Science and Technology Endowment to M.P., and the Department of Energy Great Lakes Bioenergy Center (DOE BER Office of Science DE-FC02-07ER64494) to I-B.R.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.G. wrote the article, designed and performed research, and analyzed the data (axy-4 and related OLIMP mutant spectra, mapping of AXY4, AXY4 overexpression line, GFP construct and analysis, and cell wall fractionation). A.d.S., G.X., M.B., A.S., K.C., and I.-B.R. performed research and analyzed the data (A.d.S., Ty-0; G.X., AXY4L; M.B., other TBL insertional mutants; K.C., 2D NMR; A.S., axy4-2; Illumina sequence assembly of axy4-1; and I.B.R., array mapping of axy4-1). M.P. wrote the article, designed research, and analyzed the data.

References

- Akoh C.C., Lee G.C., Liaw Y.C., Huang T.H., Shaw J.F. (2004). GDSL family of serine esterases/lipases. Prog. Lipid Res. 43: 534–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J.M., et al. (2003). Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301: 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schäffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger D., Altmann T. (2000). A subtilisin-like serine protease involved in the regulation of stomatal density and distribution in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 14: 1119–1131 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biely P., Mackenzie C.R., Puls J., Schneider H. (1986). Cooperativity of esterases and xylanases in the enzymatic degradation of acetyl xylan. Biotechnology (NY) 4: 731–733 [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff V., Nita S., Neumetzler L., Schindelasch D., Urbain A., Eshed R., Persson S., Delmer D., Scheible W.R. (2010a). TRICHOME BIREFRINGENCE and its homolog AT5G01360 encode plant-specific DUF231 proteins required for cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 153: 590–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff V., Selbig J., Scheible W.R. (2010b). Involvement of TBL/DUF231 proteins into cell wall biology. Plant Signal. Behav. 5: 1057–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borevitz J. (2006). Genotyping and mapping with high-density oligonucleotide arrays. In Arabidopsis Protocols, Salinas J., Sanchez-Serrano J.J., (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; ), pp. 137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffall K.H., Mohnen D. (2009). The structure, function, and biosynthesis of plant cell wall pectic polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 344: 1879–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita N.C. (1996). Structure and biogenesis of the cell walls of grasses. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 47: 445–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A., Somerville C. (2009). Cellulosic biofuels. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60: 165–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier D.M., Lerouxel O., Neumetzler L., Yamauchi K., Reinecke A., Freshour G., Zabotina O.A., Hahn M.G., Burgert I., Pauly M., Raikhel N.V., Keegstra K. (2008). Disrupting two Arabidopsis thaliana xylosyltransferase genes results in plants deficient in xyloglucan, a major primary cell wall component. Plant Cell 20: 1519–1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Mackey K. (1995). Substitution of chloroform by bromo-chloropropane in the single-step method of RNA isolation. Anal. Biochem. 225: 163–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S.J., Bent A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M.D., Grossniklaus U. (2003). A Gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 133: 462–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski T., Stitt M., Altmann T., Udvardi M.K., Scheible W.R. (2005). Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139: 5–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Río J.C., Marques G., Rencoret J., Martínez A.T., Gutiérrez A. (2007). Occurrence of naturally acetylated lignin units. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55: 5461–5468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz S., Higa H.H., Hayes B.K., Varki A. (1989). O-acetylation and de-O-acetylation of sialic acids. 7- and 9-o-acetylation of alpha 2,6-linked sialic acids on endogenous N-linked glycans in rat liver Golgi vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 264: 19416–19426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont C., Clarke A.J. (1991). Evidence for N——O acetyl migration as the mechanism for O acetylation of peptidoglycan in Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 173: 4318–4324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry S.C., et al. (1993). An unambiguous nomenclature for xyloglucan-derived oligosaccharides. Physiol. Plant. 89: 1–3 [Google Scholar]

- Gille S., Cheng K., Skinner M.E., Liepman A.H., Wilkerson C.G., Pauly M. (2011). Deep sequencing of voodoo lily (Amorphophallus konjac): An approach to identify relevant genes involved in the synthesis of the hemicellulose glucomannan. Planta 234: 515–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gille S., Hänsel U., Ziemann M., Pauly M. (2009). Identification of plant cell wall mutants by means of a forward chemical genetic approach using hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 14699–14704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günl M., Gille S., Pauly M. (2010). OLIgo mass profiling (OLIMP) of extracellular polysaccharides. J. Vis. Exp. 40: 2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günl M., Neumetzler L., Kraemer F., de Souza A., Schultink A., Pena M., York W.S., Pauly M. (2011). AXY8 encodes an a-Fucosidase, underscoring the importance of apoplastic metabolism on the fine structure of Arabidopsis cell wall polysaccharides. Plant Cell (vol.) 23, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helle S., Cameron D., Lam J., White B., Duff S. (2003). Effect of inhibitory compounds found in biomass hydrolysates on growth and xylose fermentation by a genetically engineered strain of S. cerevisiae. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 33: 786–792 [Google Scholar]

- Higa H.H., Butor C., Diaz S., Varki A. (1989). O-acetylation and de-O-acetylation of sialic acids. O-acetylation of sialic acids in the rat liver Golgi apparatus involves an acetyl intermediate and essential histidine and lysine residues—a transmembrane reaction? J. Biol. Chem. 264: 19427–19434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofgen R., Willmitzer L. (1990). Biochemical and genetic analysis of different patatin isoforms expressed in various organs of potato (Solanum tuberosum). Plant Sci. 66: 221–230 [Google Scholar]

- Janbon G., Himmelreich U., Moyrand F., Improvisi L., Dromer F. (2001). Cas1p is a membrane protein necessary for the O-acetylation of the Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Mol. Microbiol. 42: 453–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer L., York W., Darvill A., Albersheim P. (1989). Xyloglucan isolated from suspension-cultured sycamore cell walls is O-acetylated. Phytochemistry 28: 2105–2107 [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Ralph J. (2010). Solution-state 2D NMR of ball-milled plant cell wall gels in DMSO-d(6)/pyridine-d(5). Org. Biomol. Chem. 8: 576–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Marcuschamer D., Oleskowicz-Popiel P., Simmons B.A., Blanch H.W. (2010). Technoeconomic analysis of biofuels, A wiki-based platform for lignocellulosic biorefineries. Biomass Bioenergy 34: 1914–1921 [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., Sonnhammer E.L.L. (2001). Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305: 567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.H., Teng Q., Zhong R.Q., Ye Z.H. (2011). The four Arabidopsis reduced wall acetylation genes are expressed in secondary wall-containing cells and required for the acetylation of xylan. Plant Cell Physiol. 52: 1289–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre V., Fortabat M.N., Ducamp A., North H.M., Maia-Grondard A., Trouverie J., Boursiac Y., Mouille G., Durand-Tardif M. (2011). ESKIMO1 disruption in Arabidopsis alters vascular tissue and impairs water transport. PLoS ONE 6: e16645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerouxel O., Choo T.S., Séveno M., Usadel B., Faye L., Lerouge P., Pauly M. (2002). Rapid structural phenotyping of plant cell wall mutants by enzymatic oligosaccharide fingerprinting. Plant Physiol. 130: 1754–1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liners F., Gaspar T., Vancutsem P. (1994). Acetyl-esterification and methyl-esterification of pectins of friable and compact sugar-beet calli: Consequences for intercellular adhesion. Planta 192: 545–556 [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist J., Teleman A., Junel L., Zacchi G., Dahlman O., Tjerneld F., Stalbrand H. (2002). Isolation and characterization of galactoglucomannan from spruce (Picea abies). Carbohydr. Polym. 48: 29–39 [Google Scholar]

- Madson M., Dunand C., Li X., Verma R., Vanzin G.F., Caplan J., Shoue D.A., Carpita N.C., Reiter W.D. (2003). The MUR3 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a xyloglucan galactosyltransferase that is evolutionarily related to animal exostosins. Plant Cell 15: 1662–1670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe Y., et al. (2011). Loss-of-function mutation of REDUCED WALL ACETYLATION2 in Arabidopsis leads to reduced cell wall acetylation and increased resistance to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 155: 1068–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore P.J., Darvill A.G., Albersheim P., Staehelin L.A. (1986). Immunogold localization of xyloglucan and rhamnogalacturonan I in the cell walls of suspension-cultured sycamore cells. Plant Physiol. 82: 787–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T., Skoog F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15: 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Mølgaard A., Larsen S. (2004). Crystal packing in two pH-dependent crystal forms of rhamnogalacturonan acetylesterase. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60: 472–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B.K., Cai X., Nebenführ A. (2007). A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J. 51: 1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumetzler L. (2010). Identification and Characterization of Arabidopsis Mutants Associated with Xyloglucan Metabolism. (Berlin: Rhombos Publishing; ). [Google Scholar]

- Nishinari K., Williams P.A., Phillips G.O. (1992). Review of the physicochemical characteristics and properties of konjac mannan. Food Hydrocoll. 6: 199–222 [Google Scholar]

- Obel N., Erben V., Schwarz T., Kühnel S., Fodor A., Pauly M. (2009). Microanalysis of plant cell wall polysaccharides. Mol. Plant 2: 922–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M. (1999). Development of Analytical Tools to Study Plant Cell Wall Xyloglucan. (Aachen, Germany: Shaker Verlag; ). [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M., Andersen L.N., Kauppinen S., Kofod L.V., York W.S., Albersheim P., Darvill A. (1999). A xyloglucan-specific endo-beta-1,4-glucanase from Aspergillus aculeatus: Expression cloning in yeast, purification and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Glycobiology 9: 93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M., Keegstra K. (2008). Cell-wall carbohydrates and their modification as a resource for biofuels. Plant J. 54: 559–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M., Scheller H.V. (2000). O-Acetylation of plant cell wall polysaccharides: identification and partial characterization of a rhamnogalacturonan O-acetyl-transferase from potato suspension-cultured cells. Planta 210: 659–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin R.M., Jia Z., Wagner T.A., O’Neill M.A., Sarria R., York W.S., Raikhel N.V., Keegstra K. (2003). Analysis of xyloglucan fucosylation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 132: 768–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombouts F.M., Thibault J.F. (1986). Enzymatic and chemical degradation and the fine-structure of pectins from sugar-beet pulp. Carbohydr. Res. 154: 189–203 [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N., Nei M. (1987). The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4: 406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson F., Brunaud V., Balzergue S., Dubreucq B., Lepiniec L., Pelletier G., Caboche M., Lecharny A. (2002). FLAGdb/FST: A database of mapped flanking insertion sites (FSTs) of Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA transformants. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 94–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheible W.R., Pauly M. (2004). Glycosyltransferases and cell wall biosynthesis: novel players and insights. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7: 285–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller H.V., Ulvskov P. (2010). Hemicelluloses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61: 263–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig M.J., Adney W.S., Himmel M.E., Decker S.R. (2009). The impact of cell wall acetylation on corn stover hydrolysis by cellulolytic and xylanolytic enzymes. Cellulose 16: 711–722 [Google Scholar]

- Siebert P.D., Chenchik A., Kellogg D.E., Lukyanov K.A., Lukyanov S.A. (1995). An improved PCR method for walking in uncloned genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23: 1087–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes I.A., Runions J., Kearns A., Hawes C. (2006). Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat. Protoc. 1: 2019–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007). MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24: 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J., Somerville S. (2000). Isolation and characterization of powdery mildew-resistant Arabidopsis mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 1897–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J.P., Raab T.K., Somerville C.R., Somerville S.C. (2004). Mutations in PMR5 result in powdery mildew resistance and altered cell wall composition. Plant J. 40: 968–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelle D.J., Ralph J., Frihart C.R. (2008). Characterization of nonderivatized plant cell walls using high-resolution solution-state NMR spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Chem. 46: 508–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl E., Pauling L. (1965). Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins. In Evolving Genes and Proteins, Vogel V., Ba H.J., (New York: Academic Press; ), pp. 97–166 [Google Scholar]