Abstract

The AAA-ATPase VCP/p97 cooperates with distinct cofactors to process ubiquitinated proteins in different cellular pathways 1–3. VCP missense mutations cause a systemic degenerative disease in humans, but the molecular pathogenesis is unclear 4, 5. We used an unbiased mass spectrometry approach and identified a VCP complex with the UBXD1 cofactor, which binds the plasma membrane protein caveolin-1 (Cav1) and whose formation is specifically disrupted by disease-associated mutations. We show that VCP-UBXD1 targets mono-ubiquitinated Cav1 in SDS-resistant high molecular weight complexes on endosomes, which are en route to degradation in endolysosomes 6. Expression of VCP mutant proteins, chemical inhibition of VCP, or siRNA-mediated depletion of UBXD1 leads to a block of Cav1 transport at the limiting membrane of enlarged endosomes in cultured cells. In patient muscle, muscle-specific Caveolin-3 (Cav3) accumulates in sarcoplasmic pools and specifically delocalises from the sarcolemma. These results extend the cellular functions of VCP to mediating sorting of ubiquitinated cargo in the endocytic pathway and suggest that impaired trafficking of caveolin may contribute to the pathogenesis in individuals with VCP mutations.

Valosin-containing protein (VCP)/p97 is a hexameric AAA+-type ATPase best known for targeting and segregating ubiquitin-conjugated protein complexes for subsequent degradation by the proteasome in as diverse cellular processes as ER-associated degradation (ERAD) or cell cycle signalling 1–3, 7. VCP cooperates with alternative sets of cofactors, including a group of UBX domain-containing proteins, which provide functional and spatial specificity 8, 9. Based on the large number of uncharacterized cofactors, VCP is thought to have many yet unidentified cellular functions 9, 10. VCP missense mutations in humans cause a dominant late-onset systemic degenerative disorder, IBMPFD for Inclusion Body Myopathy (IBM) associated with Paget’s Disease of bone (PDB) and Fronto-Temporal Dementia (FTD), also called VCP disease 4, 5. Although cellular defects associated with IBMPFD mutations have been proposed 11–15, the molecular pathogenesis has still remained unclear given that VCP is essential and patients develop normally until their fourth or fifth decade. Because mutant VCP still binds to the major cofactors p47 or Ufd1-Npl4 and its ATP hydrolysis activity is only mildly affected at most 15, 16, we hypothesized that an as yet unidentified function may be specifically affected by the mutations in VCP.

To identify such a function, we used an unbiased mass spectrometry approach (Fig. 1a) to search for a distinct VCP cofactor or substrate, whose interaction may specifically be compromised by the most common disease-associated mutation, R155H (RH) 4. We induced mild overexpression of myc/strep-tagged VCP-RH in stable HEK293 cells. For comparison, we expressed wild-type (WT) or the ATPase-deficient substrate-trapping mutant E578Q (EQ) 17, 18. Tandem isolation revealed that tagged VCP integrated with endogenous VCP hexamers in a roughly 1:1 ratio (Fig. 1b). We analysed associated proteins using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and compared interaction partners identified with high probability of ≥99% 19 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table S1). Eight common cofactors including components of the ERAD system were consistently identified in all samples independent of the VCP variant, suggesting that the major processes are not affected by the disease-associated VCP-RH mutation in the HEK293 cells, and consistent with a previous report 11. This was supported by analysis with the XBP1ΔDBD-venus reporter assay 20 showing that the ER unfolded protein response was not induced by VCP-RH overexpression in contrast to VCP-EQ (Supplementary Fig. S1a).

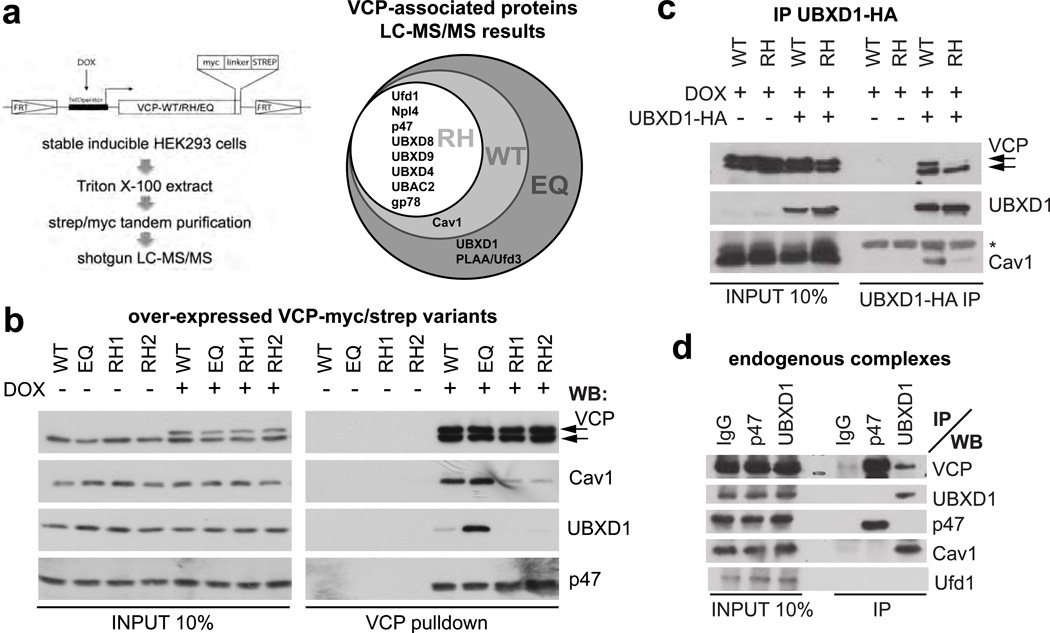

Fig. 1. The VCP/p97UBXD1 chaperone complex binds caveolin, and this interaction is specifically disrupted by IBMPFD-associated mutations in VCP.

(a) Mass spectrometry-based strategy to identify differences in the interaction pattern of VCP wild-type (WT), the disease-associated mutant R155H (RH) or the ATPase-deficient E578Q (EQ). Myc/strep-tagged VCP variants were doxycycline (DOX)-induced and tandem isolated from stable HEK293 cell lines. Associated proteins were detected in a shotgun approach and high probability (≥99%) candidates represented in a Venn diagramm. For full details, see Supplementary Table S1.

(b) Western blot confirming differential interaction of caveolin-1 (Cav1) and UBXD1 with VCP variants. The p47 cofactor served as control. RH1 and RH2 represent two independent cell lines. Arrows indicate endogenous and overexpressed VCP. Consistent results for the R93G and A232E disease mutants are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1c.

(c) Immunoprecipitation of HA-tagged UBXD1 from cells expressing VCP-WT or VCP-RH. Note reduced binding of VCP-RH (upper arrow) and Cav1 in the VCP-RH background. (*), antibody light chain.

(d) Immunoprecipitations of indicated endogenous VCP cofactors with specific antibodies. Note that UBXD1 specifically binds VCP and Cav1, and is devoid of the p47 or Ufd1 cofactors.

Importantly however, we identified a new VCP binding factor Caveolin-1 (Cav1) as a high-probability hit both in WT and EQ, but not in RH isolates (Fig. 1a). Western blot analysis confirmed that Cav1 bound VCP and that this interaction was specifically compromised by the RH mutation (Fig. 1b). In addition, we detected the UBXD1 cofactor 9, 21 in EQ isolates (Fig. 1a, b), and found that it also coisolated with WT at lower levels, but not with RH (Fig. 1b). Binding of UBXD1 and Cav1 to two other IBMPFD-associated VCP mutants, R93G and A232E was also affected (Supplementary Fig. S1c), suggesting that compromised binding of VCP to UBXD1 and Cav1 is a general defect underlying the disease. In all cases, the interaction of the VCP mutant proteins with the major cofactors p47 and Ufd1-Npl4 was slightly increased (Fig. 1b and S1c) as recently reported 15.

Next, we asked whether VCP, UBXD1 and Cav1 form a single complex. Sequential isolation of VCP by virtue of its strep-tag from cells overexpressing all three factors, followed by native elution and immunoprecipitation of UBXD1 coisolated Cav1, indicating that they form a ternary complex (Supplementary Fig. S1d). Direct isolation of UBXD1 from WT and RH expressing cells further supported this notion and confirmed that Cav1 binding to UBXD1 was reduced in the RH background (Fig. 1c). Immunoprecipitation of endogenous UBXD1 or p47 with specific antibodies showed that the interaction with Cav1 was specific for the VCPUBXD1 complex, which did not contain any of the other major cofactors, p47 or Ufd1-Npl4 (Fig. 1d). These results demonstrate that UBXD1 defines an alternative VCP complex, which binds Cav1 and whose formation is specifically compromised by disease-associated mutation of VCP.

Cav1, and its isoforms caveolin-2 and the muscle-specific caveolin-3 (Cav3) are membrane proteins that form the major constituent of caveolae 22. Caveolae are invaginations of the plasma membrane that define cholesterol-rich microdomains, which are important for signalling, endocytosis and maintenance of the plasma membrane 22. Cav1 is synthesized in the ER and assembles along the biosynthetic pathway to large caveolar domains 23–25 that subsequently travel between the plasma membrane and endosomes 26, 27. For degradation, Cav1 is modified with monoubiquitin, a signal important for endosomal sorting 28, and transported to intraluminal vesicles in endolysosomes 6. In other cellular processes, VCP targets ubiquitin-modified substrate proteins 1–3. We therefore initially confirmed that Cav1 is conjugated predominantly with mono-ubiquitin in HEK293 cells (Fig. 2a). We then showed in sequential immunoprecipitations that Cav1 associated with VCP in the ubiquitinated form in addition to the unmodified form (Fig. 2b). To ask whether ubiquitination may be essential for the interaction with VCP, we analysed a Cav1-K*R variant, in which all 12 lysines were mutated to arginines. Cav1-K*R still travels to early endosomes, but cannot be ubiquitinated and transported to endolysosomes (ref 6, and Supplementary Fig. 2). Indeed, coimmunoprecipitations revealed that binding to VCP was abolished (Fig. 2c), suggesting that Cav1 ubiquitination is important for targeting by VCP.

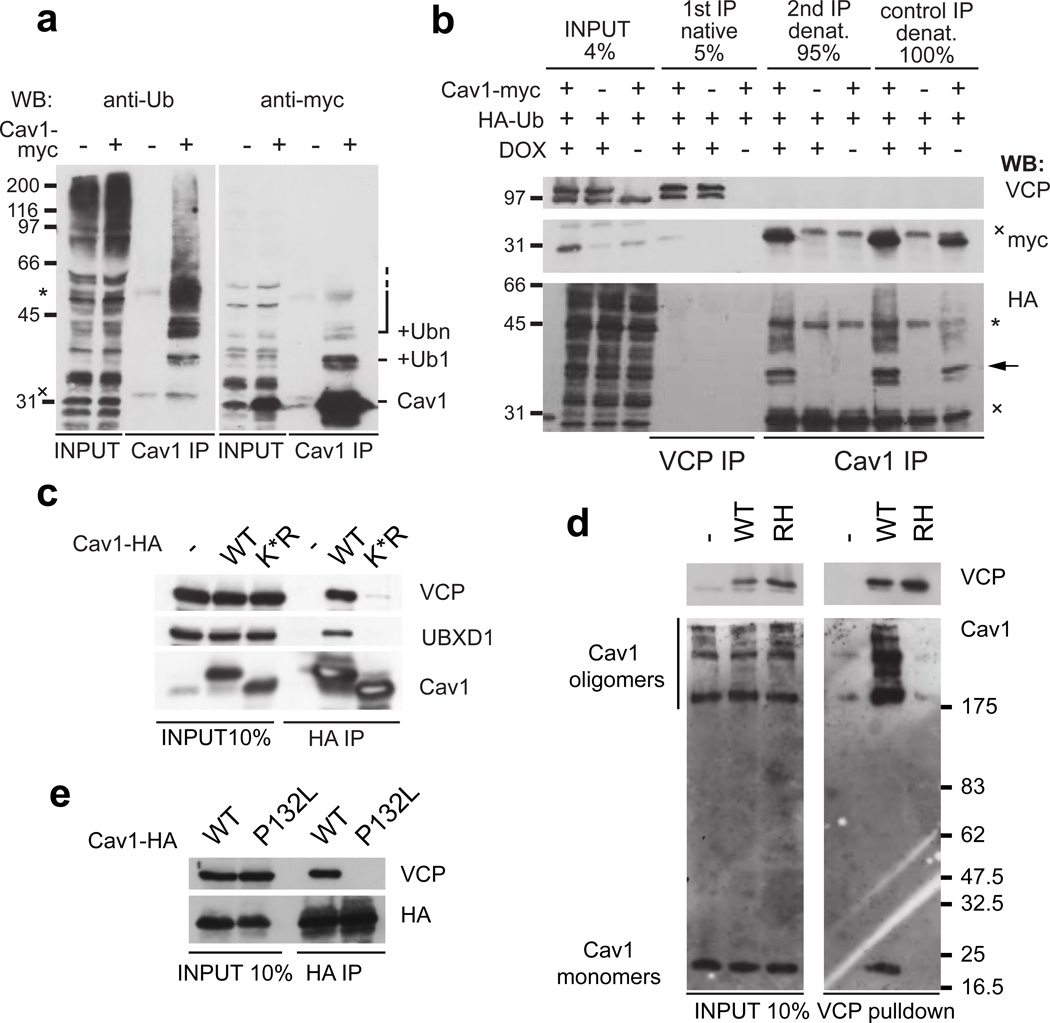

Fig. 2. VCP targets mono-ubiquitinated Cav1 in SDS-resistant oligomers.

(a) Ubiquitin-modification of Cav1 was detected with the anti-ubiquitin FK2 or the anti-myc antibodies after Cav1-myc expression and isolation with the Cav1-specific N20 antibody. Note a prominent monoubiquitination and minor multi- and/or polyubiquitination.

(b) Sequential immunoprecipitations show that VCP binds monoubiquitinated Cav1 (arrow). First, DOX-induced VCP was isolated from HA-ubiquitin and Cav1-myc expressing cells. 5% of it was loaded (1st IP), the remaining 95% was denatured to remove associated proteins and Cav1 re-isolated with the specific N20 antibody (2nd IP). Direct IP from denatured lysates served as reference. (*) and (x) mark antibody heavy and light chains, respectively.

(c) Cav1-HA wild-type (WT) or the K*R mutant, whose ubiquitination is abolished due to mutation of all 12 lysine residues to arginine, was expressed and association with VCP and UBXD1 analysed by Cav1-HA immunoprecipitation.

(d) VCP preferentially targets SDS-resistant Cav1 oligomers. VCP-WT and -RH complexes were isolated from CV-1 cells and separated in SDS-gels for Western blotting without prior boiling. Cav1 monomers and SDS-resistant oligomers were detected in inputs. Note specific enrichment of oligomers in VCP complexes.

(e) The disease-associated and oligomerization-deficient Cav1-P132L mutant was overexpressed with HA-tag and immunoprecipitated. Note reduced VCP binding.

During maturation, Cav1 first forms SDS-resistant oligomers that associate to larger assemblies in a cholesterol-dependent manner during exit from the Golgi apparatus 23, 24, 29, 30. Like other AAA+-type ATPases, VCP uses the energy of ATP hydrolysis to segregate proteins from stable complexes for further processing 17, 18, 31. We therefore asked whether VCP targets SDS-resistant Cav1 oligomers. Lysates of control, VCP-WT or -RH expressing CV-1 cells were separated on SDS-gels without prior boiling and displayed a typical pattern of SDS-resistant Cav1 complexes above the apparent molecular weight of 200 kDa in Western blots (Fig. 2d) 29. Isolation of VCP revealed that the associated Cav1 was enriched in such complexes over the monomeric form in the case of WT, but not RH, showing that indeed VCP targets Cav1 oligomers.

To confirm the observed selectivity of VCP for these oligomers, we used two ways to disrupt oligomerization. First, we expressed a Cav1 variant with the P132L mutation that is defective in oligomerization 32. Second, we depleted plasma membrane pools of cholesterol with the inhibitor U18666A 23. In both cases, VCP binding in pulldown experiments was reduced or abolished (Fig. 2 e and Supplementary Fig. S1e). The large assemblies separate from the individual SDS-resistant complexes in velocity centrifugation gradients with sedimentation coefficients of 70S and 8S, respectively 23. Both peaks sedimented normally in lysates from VCP-WT or -RH expressing cells, while the 70S selectively shifted to the bottom of the gradient in VCP-EQ lysates (Supplementary Fig. S1f). Together, these data provide biochemical evidence suggesting that VCPUBXD1 complex binds the caveolin oligomers that occur post-Golgi at or near the plasma membrane.

To confirm this notion morphologically, we assessed colocalisation of Cav1-GFP with UBXD1-mCherry overexpressed in live U2OS cells. Cav1 localised to caveolae at the plasma membrane in addition to larger intracellular structures (Fig. 3a). UBXD1 specifically colocalised with Cav1 to these structures, in addition to its diffuse cytosolic distribution (Fig. 3a). The intracellular structures were the previously described endocytic compartments6, because they colocalised with GFP fusions of markers for early and late endosomes, Rab5, Rab7 and LAMP1 (Supplementary Fig. S2a,b). Consistent with the biochemical analysis, recruitment of UBXD1 to endosomes required ubiquitination of Cav1, because UBXD1 did not associate to endosomes in cells transfected with the Cav1-K*R variant that failed to be ubiquitinated (Supplementary Fig. 2c–f).

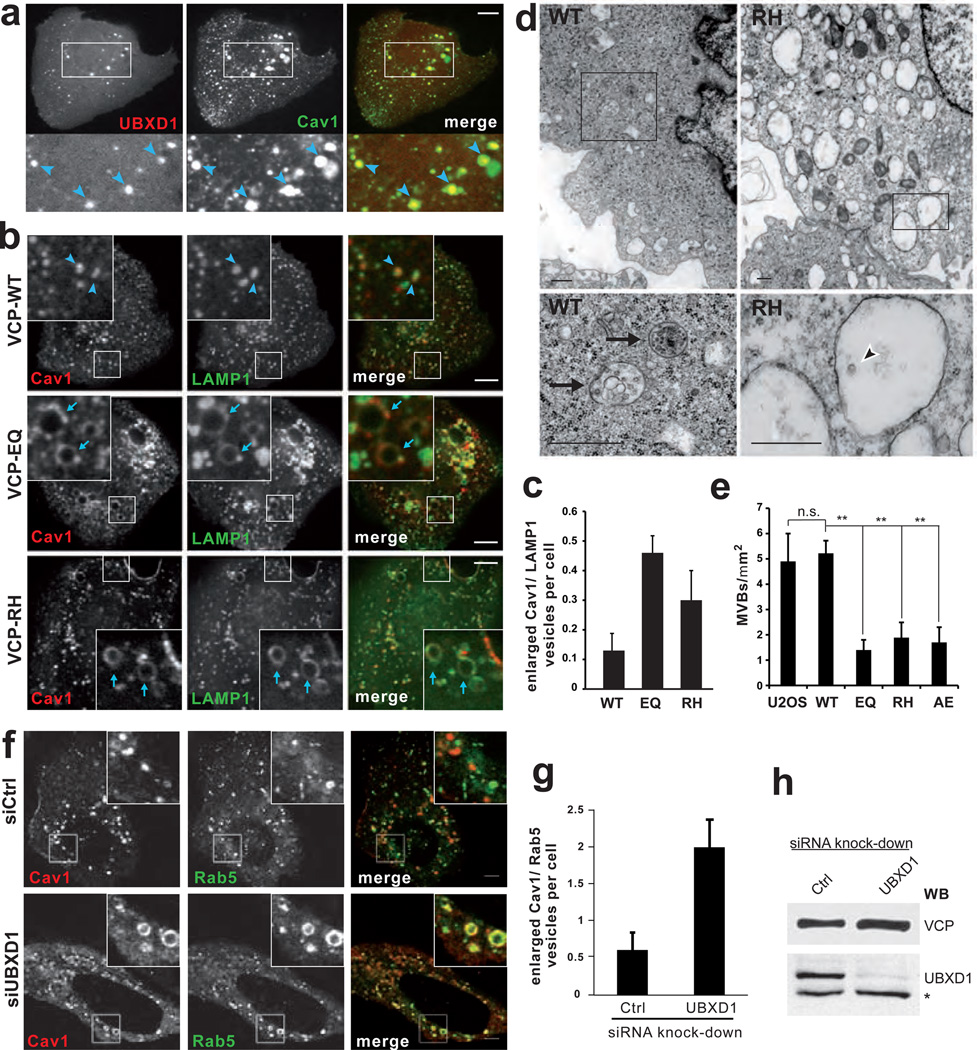

Fig. 3. Overexpression of VCP mutants or depletion of UBXD1 affect Cav1 transport to endolysosomes.

(a) Cav1 and UBXD1 colocalise on early and late endosomes. UBXD1-mCherry and Cav1-GFP were transiently expressed and visualised in live U2OS cells by spinning disk confocal microscopy. Arrowheads indicate compartments showing colocalisation. Manders' colocalisation coefficient was 0.955 compared to 0.079 for mCherry alone (not shown), n=16 cells per condition. See Supplementary Fig. S2a for colocalisation with endosome markers. Scale bar, 10 µm.

(b) Expression of VCP WT, EQ or RH variants was induced by doxycycline for 24 h in stable U2OS cells transiently expressing Cav1-RFP and LAMP1-GFP. Live cells were visualised by spinning disk confocal microscopy. Arrowheads indicate Cav1 localising to late endosome/lysosomes. Arrows indicated Cav1 on enlarged late endosomes. Scale bars, 10 µm.

(c) The number of enlarged LAMP1-positive vesicles (>0.8 µm diameter) with Cav1 at the limiting membrane was determined (s.d., 3 independent experiments, >140 cells per condition).

(d) Electron micrographs of VCP-WT or -RH expressing stable U2OS cells. Arrows indicate multivesicular bodies (MVBs). The arrowhead indicates a single intraluminal vesicle. Scale bars, 500 nm.

(e) Quantification, number of MVBs per square micron cytoplasm. S.d., n=10 cells per condition.

(f) Cellular depletion of UBXD1 affects endosomal sorting of Cav1. U2OS cells were transfected with control or UBXD1 siRNA oligos. Cav1-RFP and Rab5-GFP were visualized in live cells by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 5 µm.

(g) Number of enlarged Cav1/Rab5-positive vesicles (>1 µm diameter) was determined (s.d., 4 independent experiments, >130 cells per condition).

(h) After imaging, cells were lysed and depletion efficiency confirmed by Western blot analysis. (*) indicates non-specific band.

Next, we asked whether VCP and UBXD1 were essential for trafficking of Cav1 to endolysosomes and whether disease-associated mutants were defective in the process. In the first approach, we induced expression of VCP mutants in stable U2OS cells transiently expressing Cav1-RFP along with LAMP1-GFP as a marker for late endosomes and lysosomes. Cav1 colocalised with LAMP1 in control cells (Fig. 3b) confirming that part of it was transported to endolysosomes 6. Strikingly however, Cav1 in VCP-RH and more so in VCP-EQ expressing cells localised to enlarged LAMP1-positive vesicles that appeared as early as 24 h after induction of mutant VCP (Fig. 3b,c). Importantly, Cav1 was restricted to the limiting membrane of these vesicles, which points to a defect in processing and transport of Cav1 to intraluminal vesicles. Ultrastructural analysis revealed that the number of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) was indeed reduced in cells expressing VCP-EQ, -RH or another disease-associated mutant, VCP-A232E (Fig. 3 d,e and Supplementary Fig. S3a). Instead, we observed an increased number of vacuoles that were empty or contained only few intraluminal vesicles. Further fluorescence microscopy analysis using the pH-sensitive lysotracker probe revealed that the aberrant Cav1/LAMP1-rimmed vesicles failed to acidify (Supplementary Fig. S3b). They were not autophagosomes, because they did not contain the autophagy marker LC3 (Supplementary Fig. S3c). Cellular depletion of UBXD1 by siRNA also specifically affected transport of Cav1 as apparent by an increase of enlarged Cav1/Rab5-positive endosomes (Fig. 3 f–h). These data show that binding and activity of VCP and its cofactor UBXD1 are required for proper sorting of Cav1 to endolysosomes.

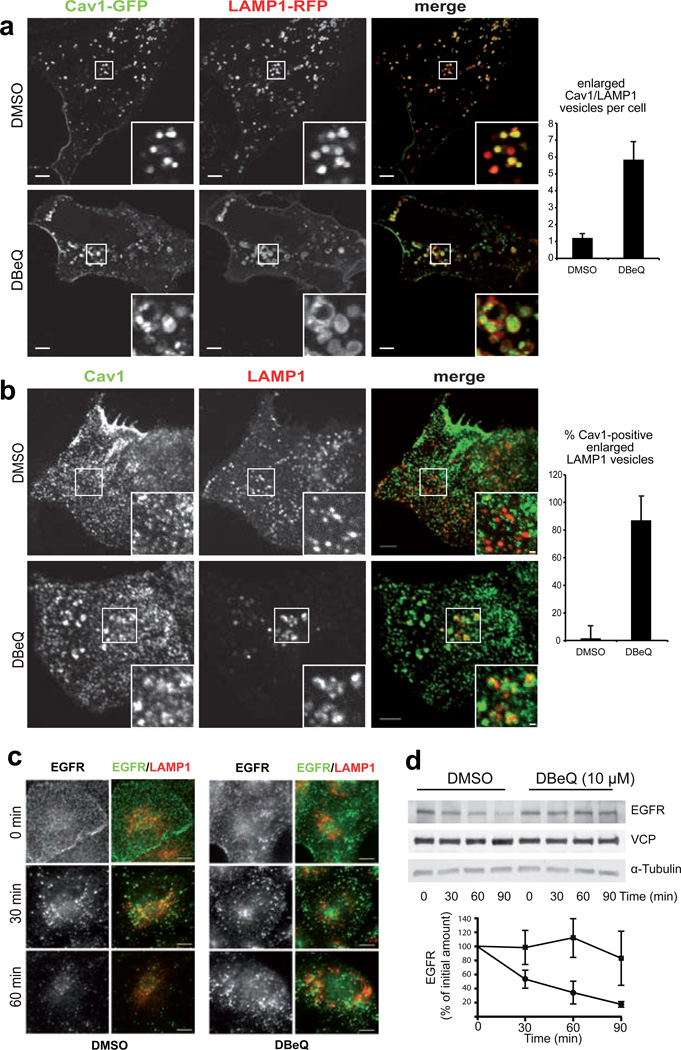

In an additional approach, we applied the VCP small molecule inhibitor DBeQ 33. Treatment for 6 hours induced accumulation of overexpressed Cav1-GFP at enlarged LAMP1-rimmed vesicles, exceeding the effect of VCP-EQ expression dramatically (Fig 4a). Even without overexpression of Cav1, DBeQ caused an enlargement of LAMP1-positive late endosomes/lysosomes and an accumulation of Cav1 in more than 80% of these structures (Fig. 4b), arguing that acute and penetrant inhibition of VCP affects trafficking also of endogenous Cav1. Next, we tested whether inhibition of VCP had a more general impact on cargo of the endocytic pathway and assessed degradation of EGF receptor (EGFR). After EGF stimulation, EGFR was endocytosed normally in control and DBeQ-treated cells as visualized by immunohistochemistry, but then persisted longer in intracellular pools in DBeQ-treated compared to control-treated cells (Fig. 4c). The delayed degradation of EGFR as also confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4d). Chemical inhibition thus confirmed the role of VCP in Cav1 trafficking and revealed a more general involvement in endosomal sorting.

Fig. 4. Chemical inhibition of VCP with DBeQ impairs Cav1 trafficking and delays degradation of EGFR.

(a) Laser scanning confocal sections of live U2OS cells transiently expressing Cav1-GFP and LAMP1-RFP after treatment with 10 µM DBeQ or solvent alone for 6 h. Scale bar, 5 µM. The number of enlarged LAMP1-positive vesicles with Cav1 at the limiting membrane was determined (s.d., 3 independent experiments, >100 cells per condition)

(b) Spinning disk confocal sections of endogenous Cav1 and LAMP1 immunolocalisation after treatment as in (a). Scale bars, 3 µM and 0.5 µM. Fraction of enlarged LAMP1-positive vesicles (>0.5 µM diameter) with Cav1 accumulation was quantified (s.d., n=30 cells per condition).

(c) EGF receptor (EGFR) and LAMP1 were immunolocalised in CV-1 cells at indicated times after EGF stimulation. DBeQ treatment, 10 µM for 5 h.

(d) Western blot analysis of EGFR in HEK393 cells at indicated times after EGF stimulation with or without DBeQ treatment as in (a). Quantification of ECL signals on film. S.d., n=5.

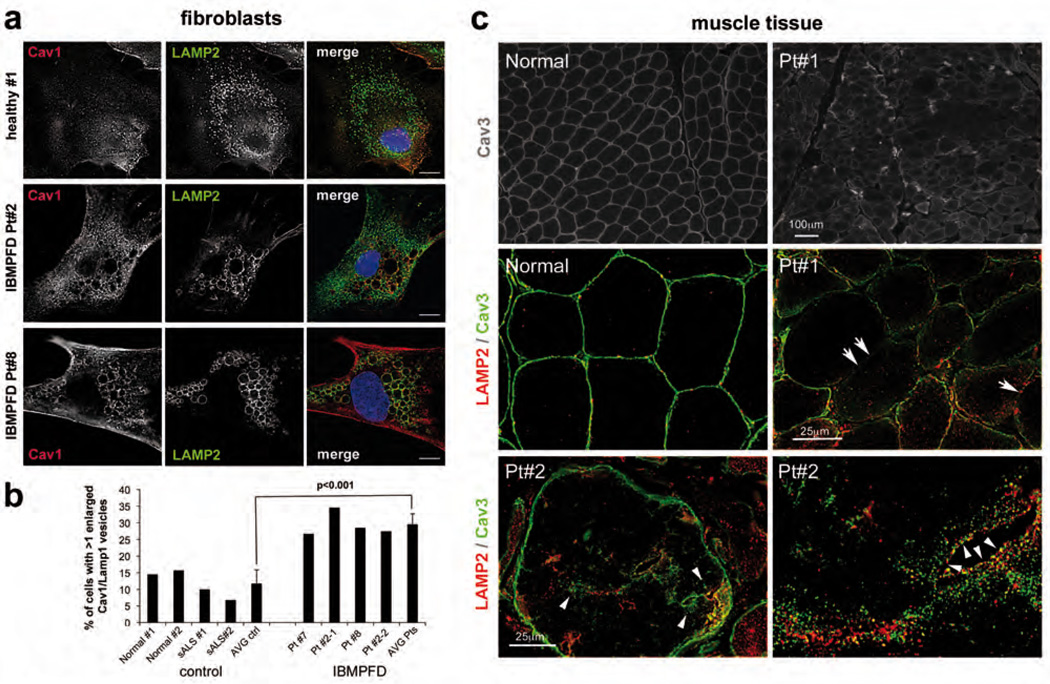

To assess whether the role of VCP in caveolin trafficking is relevant to IBMPFD patients, we first analysed cultured fibroblasts from 3 different patients harbouring two different VCP mutations (see Supplementary Table S2 for patient demographics). We compared distribution of endogenous Cav1 and LAMP2 by immunofluorescence microscopy with cells from healthy individuals or patients with another degenerative disorder, sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (sALS). Again, Cav1 displayed increased localisation to the limiting membrane of enlarged vesicles that were positive for LAMP2 in IBMPFD patient cells compared to control cells (Fig. 5a and b). Consistently, the vesicles were not acidified and did not contain LC3 (data not shown). Next, we analysed Cav3 localisation in muscle tissue from 6 different IBMPFD patients. While Cav3 in healthy individuals displayed the typical sarcolemmal localisation, it accumulated in sacroplasmic pools that associated and partially overlapped with late endosomes in patient tissue (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. S4a). Strikingly, Cav3 also specifically delocalised from the sacrolemma. This entailed delocalisation of its partner protein cavin-1, but not of other plasma membrane proteins dysferlin, dystrophin and dystrophin associated glycoproteins (Supplementary Fig. S4b,c). These data provide evidence that disease-associated mutations of VCP specifically interfere with caveolin trafficking in cultured cells and patient tissue.

Fig. 5. Mislocalisation of caveolin in fibroblasts and muscle tissue of IBMPFD patients.

(a) Cultured skin fibroblasts from two healthy donors, two patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (sALS) and three IBMPFD patients were fixed, immunostained with antibodies to Cav1 and LAMP2 and imaged by epifluorescence microscopy. Only cells of one healthy control, and of IBMPFD patient #2 (Pt#2, harbouring the VCP R155H mutation) and #8 (L198W mutation) are shown. See Table S2 for patient demographs. Scale bars, 10 µM.

(b) Quantification of cells in (a). Percentage of cells with more then one Cav1/LAMP2-positive vesicle was determined. Average (AVG) and STDEV were of 4 control, and 4 IBMPFD cell isolates (two of Pt#2, one of #7 and #8 each), respectively, with >100 cells each. Significance (t-test) is indicated.

(c) Muscle tissue sections of a healthy individual and IBMPFD patients. Immunohistochemistry as indicated. Note the accumulation of Cav3 along LAMP2 in the sarcoplasm (arrowheads) and specific delocalisation of Cav3 from the sarcolemma (arrows). See Supplementary Fig. 4 for localisation of unaffected control sacrolemmal proteins and additional patient samples.

VCP has well-established roles in facilitating proteasome-dependent degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins. Our results now link VCP and UBXD1 to ubiquitindependent membrane sorting at endosomes and degradation in lysosomes, and suggest that this pathway is impaired in IBMPFD. VCP binds a mono-ubiquitinated cargo substrate, Cav1, on endosomes and is critical for its transport to endolysosomes. Blocking VCP binding of Cav1 (with IBMPFD-associated mutations) or its protein segregase activity (with the EQ mutation or the DBeQ inhibitor) leads to accumulation of Cav1 at the limiting membrane of late endosomes. Given that VCP targets SDS-resistant Cav1 oligomers (Fig. 2), one possible scenario is that VCP helps to segregate stable, SDS-resistant Cav1 assemblies to facilitate their transport to the lumen of endolysosomes. Cellular depletion of the UBXD1 cofactor also affected Cav1 trafficking (Fig 3f,g), but not VCP-Cav1 interaction (data not shown), suggesting that UBXD1 may help VCP in substrate-processing rather than acting as a substrate adapter. Interestingly, another cofactor, PLAA/Ufd3 that we identified in our screen (Fig. 1a) was shown to function in sorting to late endosomes in yeast 34, suggesting a conserved role of VCP in this process. Chemical inhibition of VCP also affected EGFR sorting, arguing that VCP is more generally involved in trafficking of endocytic cargo. Our results do not exclude that compromised interaction with other cofactors reported during the course of this study may be relevant15. At least in the case of the E4B/Ufd2 cofactor however, the reduction in binding appears minor compared to Cav1 and UBXD1 in our hands (Supplementary Fig. S5). Together, we therefore propose that impaired endosomal trafficking constitutes an important aspect in the cytopathology caused by IBMPFD-associated mutations.

Consistently, we show that VCP mutations are associated with Cav3 mislocalisation in IBMPFD patient muscle, identical to that observed in transgenic mice expressing VCP-RH 35. Importantly, myopathy causing mutations in Cav3 result in a similar mislocalisation 36. These include a P104L missense mutation in Cav3, whose equivalent P132L in Cav1 abolishes VCP binding (Fig. 2e). This supports the notion that Cav3 mislocalisation in IBMPFD patient tissue may contribute to IBM pathogenesis. Impaired Cav1 and receptor sorting may also be relevant to PDB, which is commonly caused by defective ubiquitin-dependent signal transduction from the plasma membrane in osteoclasts37. Moreover, the third phenotypic feature in IBMPFD is FTD. Of note, one pathologically similar form of FTD is associated with mutations in Chmp2b, another factor that is essential for endosomal sorting and MVB biogenesis38. In analogy, impaired VCP-mediated endosomal sorting may therefore even be relevant for the pathogenesis in neurons.

Material and methods

Plasmid constructs

The coding sequence of rat VCP was PCR-cloned with a C-terminal myc/strep-tag (amino acid sequence: EQKLISEEDL-NMHTG-WSHPQFEK) into the NheI/BamHI sites of pcDNA5FRT/TO (Invitrogen). Missense mutations were introduced according to the Quikchange protocol and the total sequence confirmed. Human UBXD1 was cloned with a C-terminal 3xHA-tag or mCherry into pIRESpuro2 (Invitrogen). Constructs for Cav1-HA, Cav1-myc, Cav1-K*R-myc, Cav1-mEGFP and Cav1-RFP were described 6, 23. Lamp1-GFP/-RFP, LC3-GFP and HA-Ubiquitin were kind gifts from Jean Gruenberg, Tamotsu Yoshimori and Pietro DeCamilli, respectively.

Cell culture and transfections

Stable inducible HEK293 cells expressing myc/strep-tagged VCP variants were generated with the Flp-In™ T-REx™ system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol and single clones selected. Stable inducible U2OS cell lines expressing VCP variants were described 14. Cells were maintained in D-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS and in presence of Penicillin/Streptomycin, stable cell lines additionally in 50 µg/ml hygromycin and 100 µg/ml zeocin (for U2OS) or 100 µg/ml hygromycine, 15 µg/ml blasticidine (for HEK293). Expression was induced by 1 µg/ml doxycycline. HEK293 cells were transfected using calcium phosphate, CV1 using electroporation (AMAXA) and U2OS using JetPei or JetPrime reagent (Polyplus). For siRNA experiments, U2OS cells were transfected with UBXD1-targeting (CCAGGUGAGAAAGGAACUUTT) or non-targeting control (UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT) oligomers at 15 nM final concentration with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and cells analysed after 48h.

Patient Fibroblasts and Skeletal Muscle

Patient dermal fibroblasts and muscle were obtained under an approved IRB protocol at Washington University School of Medicine. All experiments were performed with fibroblasts at matched passage number of less than 10. One fibroblast line (GM20926) was obtained from Coriell Cell repositories (Camden, NJ). Fibroblasts were grown for 1–2 days, methanol-fixed, processed for immunodetection. For cell counting, >100 fibroblasts were counted from >10 randomly identified fields with a 40X objective utilizing two sets of coverslips/fibroblast culture. Caveolin-1 immunoreactive vacuoles were identified as full circle with an empty lumen. For statistics, each control or IBMPFD fibroblast line was treated as independent experiment (therefore an N=4 and the average and SE from these four control cell lines was calculated). Frozen tissue was sectioned (10 µM), acetone-fixed and processed for immunodetection. For some antibodies a biotinylated secondary antibody was used and then detected via a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Labs). Specimens were examined using a fluorescent microscope (Nikon 80i upright) and Roper Scientific EZ monochrome CCD camera with deconvolution software analysis (NIS Elements, Nikon) at RT.

Electron microscopy

For thin-section EM, cells were grown to 70% confluence in a 100 mm dish and induced to express VCP variants for 16 hours. For sample preparation, trypsinized cells were collected, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in sodium cacodylate, embedded, sectioned and stained with uranyl acetate according to standard procedures. For quantitation 10 randomly generated 300 × 300 micron images were taken for each condition. An MVB was identified as a vacuole with a diameter of >200 nm containing three or more internal vesicles.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the unpaired two-sided t-test. P < 0.05 (**) was considered statistically significant.

Fluorescence imaging and colocalization analysis

For live cell imaging, U2OS cells were seeded into μ-Slides 8 well chambers (Ibidi) one day before transfection or induction. Live cell imaging was performed using Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope equipped with a Yokogawa CSU10 Spinning Disk Confocal unit and a temperature/CO2 controlled incubator. Images were acquired using a Hamamatsu C9100–13 EMCCD camera, an Argon-Krypton laser (Spectra Physics), and a 100x/1.4NA PlanApo oil-immersion objective. Acquisition was driven by Metamorph (Molecular Devices). Alternatively, a Leica TCS SP5 Laser Scanning Microscope, with a 100x/1.49NA oil-immersion objective was used. For quantification of UBXD1-mCherry colocalisation with Cav1-GFP or Cav1-HA, the JACoP plugin in ImageJ software 39 was used and the Manders’ coefficient was calculated for signal overlap: fraction of the UBXD1-mCherry signal overlapping with Cav1-GFP (Fig. 3a) or fraction of the Cav1-HA immuno-signal overlapping with UBXD1-mCherry (Fig. S6). For quantification with endosomal markers, live cells were imaged using a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu camera, 100W HBO lamp and Metamorph software. Automated colocalization analysis was performed using a Matlab routine to detect endosomal structures on epifluorescence images of live cells acquired with an Olympus IX71 system and determine overlap between D1-mCherry and endosomal markers as described 6. Detected D1-mCherry structures overlapping at least 40% with endosomal markers were considered colocalizing. For indirect immunofluorescence, cells were seeded on coverslips and fixed in 4% formaldehyde. Epifluorescence images were taken on a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope with the Andor DR-328G-C01-SIL camera. For confocal images a Yokogawa CSU-X1 unit attached to the same microscope was used and images were acquired with an Andor iXon X3 EMCCD camera.

Flow cytometry

Stable HEK293 cells were transfected with the pCAX-F-XBP1ΔDBD-venus construct 20 and VCP variants induced by doxycycline. After 24 h, cells were fixed and XBP1-venus intensities were measured at 488 nm in an FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer.

Antibodies and other reagents

Anti-p97, anti-p47, anti-Npl4 and anti-Ufd1 5E2 (Abcam) were used as described 18. Anti-UBXD1 (1:1000, E43) was raised in rabbits against full-length human UBXD1 fused to GST. For Western blot after immunoprecipitation, biotinylated anti-p47 and anti-UBXD1 were detected with Steptavidin-HRP. Anti-myc 9E10 (1:1000), anti-Cav1 N20 (1:500, Santa Cruz, sc-894), anti-HA HA11 (1:2000, Covance), anti-Ufd2/E4 (1:1000, BD Biosciences), anti-Ub FK2 (1:500, Millipore), anti-LAMP1 (1:500, H4A3) and anti-LAMP2 (1:1000, Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-PTRF/cavin-1 (1:500, Bethyl Labs), rabbit anti-caveolin-3 (1:1500, Affinity Bioreagents), mouse anti-dysferlin (1:250, Vector Labs), anti-γ-sarcoglycan (1:500, Novocastra) and mouse anti-dystrophin (1:500, Novocastra) were purchased. AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence (1:600) and lysotracker green were purchased from Invitrogen. Lysotracker was incubated at 100 nM for 1h. DBeQ was purchased (Interbioscreen).

Immuno- and affinity-isolation

For protein isolation, cells were lysed in EB (150 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2 , 25 mM Tris-HCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5% Glycerol, 2 mM ß-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.4, and Roche Complete™ EDTA-free protease inhibitors) for 20 min on ice and cleared for 15 min at 16000 g. Immunoprecipitations and pulldown experiments were done in EB using Strep-Tactin sepharose (IBA Biotagnology), anti-c-myc agarose (Sigma), anti-HA agarose (Sigma), or specific antibodies and Protein-G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). For sequential isolation, VCP complexes were isolated with Strep-Tactin and eluted at 95°C in 1% SDS. Samples were diluted with EB to 0.1% SDS and Cav1 was immunoprecipitated using anti-Cav1 (N20).

EGFR degradation assay

Cells were serum-starved in DMEM for 16 h and treated with 10 µM DBeQ or solvent alone for a total of 6h. EGFR internalization was induced by addition of 50 ng/ml EGF (Immunotools) for indicated times before lysis in EB or fixation. Western blots were quantified from scans with Bio-1D software (Vilber Lourmat). Microscopy was performed as stated above.

Analysis of SDS-resistant Cav1 oligomers and sucrose velocity gradients

CV1 cells were transfected with VCP variants and lysed after 24 h in EB. Cleared lysates (212 µg protein) were diluted to 200 µl. VCP was isolated with Strep-Tactin sepharose and eluted in 10 mM biotin in EB. Western blot analysis was done as described 24. Briefly, 5x low-SDS sample buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 0.5% SDS, 1.9% Glycerol, 0.5 M DTT and 0.2% Bromphenolblue) was added to eluates, and samples analysed on a gradient gel without boiling (NuPAGE® Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel, SIGMA) using NuPAGE® MOPS SDS Running Buffer. Proteins were semi-dry blotted onto PVDF membrane and processed for immunodetection. Velocity gradients were run as described 23 with lysates from stable HEK293 cells induced for 24h. Western blot were quantified using a GS-800 Calibrated Densitometer (Biorad) and ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

VCP tandem isolation for MS analysis

Cleared lysates (~20 mg protein) were diluted to 5 ml with EB supplemented with 1 mg/ml BSA and 1 µM Avidin (IBA Biotechnology). Samples were incubated with 400 µl Strep-Tactin sepharose slurry. Bound proteins were eluted with 2.5 mM biotin and incubated with 200 µl anti-myc-c-agarose slurry (SIGMA). Proteins were eluted in 0.2 M glycine pH 2.5 and the pH adjusted to 8.8 with ammonium bicarbonate. For reduction, proteins were incubated in 5 mM TCEP for 1 h at 37C, followed by incubation with 25 mM iodoacetamide. Proteins were trypsin digested and peptides purified on C18 Microspincolumns (Harvard Apparatus) in 5% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, dried and resuspended in 0.1% Formic acid.

LC-MS/MS analysis

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 1100 series pump (Agilent Technologies) and a LTQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron). The setup of the μRPLC system and the capillary column were described previously 40. The electrospray voltage was set to 1.8kV. Mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase B was 100% acetonitrile (Sigma, Buchs, Switzerland). For analysis, a separating gradient from 5% to 45% mobile phase B over 40 min at 0.3 µl/min was applied. The three most abundant precursor ions in each MS scan were selected for CID if the intensity of the precursor ion exceeded 10000 ion counts. Dynamic exclusion window was set to 2 min.

MS2 peptide assignments and MS1 alignment

Acquired MS2 scans were searched against the human International Protein Index (IPI) protein database (v.3.26) using the XTandem search algorithm with k-score plug-in 40. In silico trypsin digestion was performed after lysine and arginine (unless followed by proline) in fully tryptic peptides. Allowed monoisotopic mass error for the precursor ions was 2 Daltons. A fixed residue modification parameter was set for carboxyamidomethylation (+57 Da) of cysteine residues. Oxidation of methionine (+16 Da) was set as variable residue modification parameter. Model refinement parameters were set to allow phosphorylation (+80 Da) of serine, threonine and tyrosine residues as variable modifications. Search results were evaluated on the Trans Proteomic Pipeline (TPP v3.2) using PeptideProphet and ProteinProphet 19. Background proteins identified in isolates from uninduced cells were subtracted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ari Helenius, Markus Kaiser and Phyllis Hanson for discussions and reagents, Gautam Dey for image analysis software, Catherine Brasseur and Gabor Csucs for technical help, and Raymond Deshaies for sharing results before publication. This work was supported by grants of the ETH (26/05-2 and 25/08-1), the DFG priority program SPP1365/2 and the Fondation Suisse de recherche sur les maladies musculaires (to H.M.). C.C.W. is supported by the NIH (R01 AG031867) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

Footnotes

Authors' contribution:

D.R. generated cells, isolated VCP complexes and performed the biochemical analyses with help from P.K., S.S. and S.B., while M.V. and M.B. performed microscopy. A.L.H. helped design experiments and performed the colocalisation analysis. H. L, T.G., M. G. and R. A. carried out mass spectrometry analysis. C.L., R.H.B. and C.C.W. performed EM and analysis of patient material. H. M. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jentsch S, Rumpf S. Cdc48 p97: a"molecular gearbox" in the ubiquitin pathway? Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer H, Popp O. Roles of Cdc48/p97 in mitosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:126–130. doi: 10.1042/BST0360126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye Y. Diverse functions with a common regulator: Ubiquitin takes command of an AAA ATPase. J Struct Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts GD, et al. Inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia is caused by mutant valosin-containing protein. Nat Genet. 2004 doi: 10.1038/ng1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weihl CC, Pestronk A, Kimonis VE. Valosin-containing protein disease: inclusion body myopathy with Paget's disease of the bone and fronto-temporal dementia. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayer A, et al. Caveolin-1 is ubiquitinated and targeted to intraluminal vesicles in endolysosomes for degradation. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:615–629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarosch E, Geiss-Friedlander R, Meusser B, Walter J, Sommer T. Protein dislocation from the endoplasmic reticulum--pulling out the suspect. Traffic. 2002;3:530–536. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer HH, Shorter JG, Seemann J, Pappin D, Warren G. A complex of mammalian Ufd1 and Npl4 links the AAA-ATPase, p97, to ubiquitin and nuclear transport pathways. Embo J. 2000;19:2181–2192. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuberth C, Buchberger A. UBX domain proteins: major regulators of the AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2360–2371. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8072-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandru G, et al. UBXD7 Binds Multiple Ubiquitin Ligases and Implicates p97 in HIF1alpha Turnover. Cell. 2008;134:804–816. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tresse E, et al. VCP/p97 is essential for maturation of ubiquitin-containing autophagosomes and this function is impaired by mutations that cause IBMPFD. Autophagy. 2010;6 doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.11014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ju JS, et al. Valosin-containing protein VCP is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:875–888. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janiesch PC, et al. The ubiquitin-selective chaperone CDC-48/p97 links myosin assembly to human myopathy. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:379–390. doi: 10.1038/ncb1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ju JS, Miller SE, Hanson PI, Weihl CC. Impaired protein aggregate handling and clearance underlie the pathogenesis of p97/VCP associated disease. J Biol Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805517200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Saiz V, Buchberger A. Imbalances in p97 co-factor interactions in human proteinopathy. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:479–485. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weihl CC, Dalal S, Pestronk A, Hanson PI. Inclusion body myopathy-associated mutations in p97/VCP impair endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:189–199. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye Y, Meyer HH, Rapoport TA. Function of the p97-Ufd1-Npl4 complex in retrotranslocation from the ER to the cytosol: dual recognition of nonubiquitinated polypeptide segments and polyubiquitin chains. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:71–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramadan K, et al. Cdc48/p97 promotes reformation of the nucleus by extracting the kinase Aurora B from chromatin. Nature. 2007;450:1258–1262. doi: 10.1038/nature06388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller A, Eng J, Zhang N, Li XJ, Aebersold R. A uniform proteomics MS/MS analysis platform utilizing open XML file formats. Mol Syst Biol. 2005;1 doi: 10.1038/msb4100024. 2005 0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwawaki T, Akai R, Kohno K, Miura M. A transgenic mouse model for monitoring endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Med. 2004;10:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nm970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madsen L, et al. Ubxd1 is a novel co-factor of the human p97 ATPase. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2927–2942. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parton RG, Simons K. The multiple faces of caveolae. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nrm2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayer A, Stoeber M, Bissig C, Helenius A. Biogenesis of Caveolae: Stepwise Assembly of Large Caveolin and Cavin Complexes. Traffic. 2010;11:361–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheiffele P, et al. Caveolin-1 and-2 in the exocytic pathway of MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:795–806. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monier S, et al. VIP21-caveolin, a membrane protein constituent of the caveolar coat, oligomerizes in vivo and in vitro. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:911–927. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tagawa A, et al. Assembly and trafficking of caveolar domains in the cell: caveolae as stable, cargo-triggered, vesicular transporters. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:769–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mundy DI, Machleidt T, Ying YS, Anderson RG, Bloom GS. Dual control of caveolar membrane traffic by microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4327–4339. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haglund K, Di Fiore PP, Dikic I. Distinct monoubiquitin signals in receptor endocytosis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sargiacomo M, et al. Oligomeric structure of caveolin: implications for caveolae membrane organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9407–9411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pol A, et al. Cholesterol and fatty acids regulate dynamic caveolin trafficking through the Golgi complex and between the cell surface and lipid bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2091–2105. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rape M, et al. Mobilization of processed, membrane-tethered SPT23 transcription factor by CDC48(UFD1/NPL4), a ubiquitin-selective chaperone. Cell. 2001;107:667–677. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H, et al. Caveolin-1 mutations (P132L and null) and the pathogenesis of breast cancer: caveolin-1 (P132L) behaves in a dominant-negative manner and caveolin-1(−/−) null mice show mammary epithelial cell hyperplasia. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1357–1369. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64412-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou TF, et al. Reversible inhibitor of p97, DBeQ, impairs both ubiquitindependent and autophagic protein clearance pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren J, Pashkova N, Winistorfer S, Piper RC. DOA1/UFD3 plays a role in sorting ubiquitinated membrane proteins into multivesicular bodies. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21599–21611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802982200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weihl CC, Miller SE, Hanson PI, Pestronk A. Transgenic expression of inclusion body myopathy associated mutant p97/VCP causes weakness and ubiquitinated protein inclusions in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:919–928. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minetti C, et al. Mutations in the caveolin-3 gene cause autosomal dominant limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1998;18:365–368. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goode A, Layfield R. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of Paget disease of bone. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:199–203. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.064428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skibinski G, et al. Mutations in the endosomal ESCRTIII-complex subunit CHMP2B in frontotemporal dementia. Nat Genet. 2005;37:806–808. doi: 10.1038/ng1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolte S, Cordelieres FP. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J Microsc. 2006;224:213–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacLean B, Eng JK, Beavis RC, McIntosh M. General framework for developing and evaluating database scoring algorithms using the TANDEM search engine. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2830–2832. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.