Abstract

Surface endothelialization is an attractive means to improve the performance of small diameter vascular grafts. While endothelial outgrowth cells (EOCs) are considered a promising source of autologous endothelium, the ability of EOCs to modulate coagulation-related blood activities is not well understood. The goal of this study was to assess the role of arterial flow conditions on the thrombogenic phenotype of EOCs. EOCs derived from baboon peripheral blood, as well as mature arterial endothelial cells from baboons, were seeded onto adsorbed collagen, then exposed to physiologic levels of fluid shear stress. For important hemostatic pathways, cellular responses to shear stress were characterized at the gene and protein level and confirmed with a functional assay for activated protein C (APC) activity. For EOCs, fluid shear stress upregulated gene and protein expression of anticoagulant and platelet inhibitory factors, including thrombomodulin, tissue factor pathway inhibitor, and nitric oxide synthase 3 (eNOS). Fluid shear stress significantly altered the functional activity of EOCs by increasing APC levels. This study demonstrates that fluid shear stress is an important determinant of EOC hemostatic properties. Accordingly, manipulation of EOC phenotype by mechanical forces may be important for the development of thrombo-resistant surfaces on engineered vascular implants.

Introduction

Endothelialization of synthetic vascular grafts has been shown to inhibit thrombosis and reduce intimal hyperplasia, thereby increasing graft patency rates.1,2 Unfortunately, the difficulty of obtaining autologous endothelial cells (ECs) has severely limited the clinical usefulness of this approach. Current methods for autologous EC sourcing require surgical harvesting of ECs from veins or microvascular tissue beds, with the potential for patient morbidity. Moreover, ECs for vascular tissue engineering applications must be available in sufficient numbers to ultimately provide confluent, durable coatings that must also function biochemically to limit graft failure due to either thrombosis or stenotic tissue ingrowth.

Endothelial progenitor cells, specifically endothelial outgrowth cells (EOCs), are a promising autologous cell source for vascular tissue engineering. While endothelial progenitor cells have been studied for their role in in vivo vasculogenesis, an in vitro derived cell population, EOCs, has been characterized by its isolation from peripheral blood, rapid expansion in vitro, phenotypic similarity to mature ECs, and ability to form a vascular network within implanted Matrigel plugs.3–9 Human EOCs have been isolated from adult blood and umbilical cord blood, which has larger populations of EOCs.5–7,10 While initial isolation procedures for EOCs required separation of the mononuclear cell population and treatment with animal proteins, Reinisch et al. developed a completely humanized system using unmanipulated peripheral blood.10 Consequently, there have been several studies describing the use of EOCs for tissue engineering applications,11–15 including observations that EOCs exhibit many of the same cellular markers and functions as vascular ECs.16,17 However, very little is known about the capacity of EOCs to modulate the activities of coagulation-related proteins and other hemostatic factors, or the effects of a variable fluid shear stress environment on EOC hemostatic properties.

The goal of this study was therefore to assess the role of fluid shear stress on the EOCs' regulation of important hemostatic molecular pathways. The model employed EOCs and mature ECs that were seeded onto absorbed type I collagen, and then exposed to physiologic levels of fluid shear stress. The findings document an important regulatory role of fluid shear stress, and therefore provide a rationale for enhancing the functional antithrombogenic potential of EOCs for tissue engineering applications.

Methods

Cell isolation and culture

Cells were obtained by primary isolation from juvenile male baboons (Papio anubis) weighing approximately 10–20 kg. Baboon carotid artery ECs were isolated from freshly harvested carotid arteries. Baboon EOCs were isolated from fresh anticoagulated blood using a modification of the method described by Lin et al. (for cells cultured on fibronectin rather than Type I collagen).4 All experiments were performed on EOCs and ECs between passages 5 and 7. Baboon EOCs and ECs were used in this report since baboons are hemostatically similar to humans, and because important findings and hypotheses generated in vitro regarding the therapeutic utility of EOC versus EC can subsequently be evaluated in vivo using endothelialized vascular implant models.18

Cellular characterization

Cellular characterization was performed using immunofluorescent staining and flow cytometry. Antibodies against von Willebrand Factor (vWF; DakoCytomation), ve-cadherin/CD144 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology clone C-19), ulex europaeus lectin (Sigma fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] conjugated), thrombomodulin/CD141 (DakoCytomation clone 1009), pecam-1/CD31 (BD Phamingen FITC conjugated clone WM59), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) (Research Diagnostics), nitric oxide synthase 3 (eNOS) (Santa Cruz clone N-20), endoglin/CD105 (Research Diagnostics clone 8E11), and CD14 (Beckman Coulter clone RM052) were used (1:100) in combination with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:40) where appropriate (Jackson Immuno Research and DakoCytomation). Unstained cell samples and cells stained with secondary antibodies only served as negative controls.

Application of shear stress

The effects of steady laminar shear stress on cellular phenotype were studied using a parallel plate flow chamber with a rectangular channel geometry.19 Cells were seeded (40,000 cells/cm2) on glass slides coated with 1.75 μg/cm2 type I collagen (bovine dermal, MP Biomedical). After 48 h of static incubation, the cells were exposed to a steady laminar shear stress of 15 dynes/cm2 for 24 h and results were compared to those obtained under static conditions.

Rhodamine phalloidin was used to visualize F-actin distribution within the cells. Shape index (SI) and angle of orientation were quantified following 24 h of shear stress exposure, where the SI is defined as 4(π)(area/perimeter2). Thus for a circular shape, SI=1.0, and for a straight line, SI=0.0. Angle of orientation or the degree of alignment of the cells was characterized by measuring the absolute value of the deviation of the primary cell axis from the direction of flow.

Microarray analyses

ECs and EOCs were removed with 2 mL of 600 U/mL collagenase (0.2 μm filtered, CLS-2, Worthington Biochemical) for 5 min to detach the cells. The cells were lysed and the RNA isolated with the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacture's recommendations. Samples were lysed in 350 μL lysis buffer and stored at −70°C. Total RNA extraction was performed along with analysis of quantity and quality immediately before cDNA synthesis to minimize the number of freeze–thaw cycles and preserve the RNA quality. The quality of extracted RNA was assessed using the RNA 6000 Nano LabChip (Agilent) on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 by evaluating degradation of ribosomal RNA peaks. The quantity of high-quality RNA that was obtained was assessed by measuring absorbance at 260 nm. Total RNA was pooled from two identical and independent experiments. Each experiment was run six times to provide three samples for analysis. Competitive microarray hybridization was performed between experimental samples and Universal Human Reference RNA (Stratagene) labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 fluorophores. For each of the four conditions (ECs and EOCs with or without fluid shear stress), three replicate microarrays were analyzed. The microarray was scanned using the Agilent Microarray Scanner System and image extraction was performed using Agilent Feature Extraction Image Analysis software. GeneSpring software was used to perform statistical analysis of gene expression from the 12 microarrays. Four comparisons were performed to determine the effect of shear on each cell type (EC: Shear vs. Static and EOC: Shear vs. Static), and to compare the results with each cell type under static and shear environments (Static: EOC vs. EC and Shear: EOC vs. EC). Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software was used to query significantly expressed genes against the Ingenuity Knowledge Base, a comprehensive database of published biological information. This software allowed investigation of relevant networks and biological functions for each of the comparisons.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

ECs and EOCs were removed using a 5 min collagenase digestion followed by gentle scraping. Cells were lysed and total RNA extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Samples were lysed in 350 μL lysis buffer and stored at −70°C. Total RNA extraction was performed along with analysis of quantity and quality immediately before cDNA synthesis as described for the microarray analysis. For important coagulation-related genes, quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed as previously described20 using SYBR green with an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The forward and reverse primers used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide Primers for Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction

| Target | Sense primer | Antisense primer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| THBD | Thrombomodulin | 5′-GCATTCGGGCTTGCTCATAG-3′ | 5′-CAAAAGCGCCACCACCA-3′ |

| TFPI | Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor) | 5′-GACTCCGCAATCAACCAAGGT-3′ | 5′-TGCTGGAGTGAGACACCATGA-3′ |

| eNOS | Nitric oxide synthase 3 (endothelial cell) | 5′-ATCTCCGCCTCGCTCATG-3′ | 5′-AGCCATACAGGATTGTCGCCT-3′ |

| F3 | Coagulation factor III (thromboplastin, tissue factor) | 5′-CACCGACGAGATTGTGAAGGAT-3′ | 5′-TTCCCTGCCGGGTAGGAG-3′ |

| VWF | von Willebrand factor | 5′-CCTATTGGAATTGGAGATCGCTA-3′ | 5′-CTTCGATTCGCTGGAGCTTC-3′ |

Protein expression

To perform flow cytometry analysis on cell samples following shear or static exposure, each slide was incubated with 2 mL of 600 U/mL collagenase for 5 min with gentle scraping. Primary antibodies to thrombomodulin/CD141 (DakoCytomation clone 1009) and tissue factor/CD142 (American Diagnostica clone VD8) were used (1:100) in combination with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:40; Jackson Immuno Research and DakoCytomation). Unstained cell samples and cells stained with secondary antibodies only served as negative controls. Cell suspensions were analyzed using a BD LSR digital flow cytometer to determine mean fluorescence intensity of control and experimental samples. During each sample run, standard beads (Bangs Labs) were analyzed to create a standard curve for conversion of fluorescence intensity measurements to units of molecules of equivalent soluble fluorescence.

Functional assessment

To quantify the effect of shear stress on the anticoagulation potential of EOCs, an activated protein C (APC) assay was performed. Immediately after flow, EOCs were rinsed and incubated for 1 h with a 5 nM Thrombin (Haematologic Technologies, Inc.) and 100 nM Protein C (Haematologic Technologies, Inc.) solution in phosphate-buffered saline with calcium and magnesium (Mediatech, Inc.). Refludan (Berlex Laboratories) was added to the samples after incubation to inhibit the thrombin. Samples were compared against an APC standard (Haematologic Technologies, Inc.) and visualized with 1 mM S-2366 (Chromogenix). Absorbance was measured at 37°C every 20 s for 20 min and the concentration of APC was determined from the slope of the data. The APC data were normalized by the total DNA in the sample as measured with the picogreen assay, according to the manufacturer's procedures (Invitrogen).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed on n≥3 samples from at least three independent experiments. Data are reported as mean±standard error of the mean. Statistical comparisons were based on analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's post hoc testing with a p-value < 0.05 considered significant. For the microarray analyses, ANOVA was performed using a Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test and the Benjamini and Hochberg False Discovery Rate multiple testing correction. The p-values<0.05 were considered significant. Pairwise comparisons were performed using a Student's t-test. To ensure that the variance values for real-time qRT-PCR data were independent of mean values, statistical analysis was performed following logarithmic transformation of the raw data.

Results

EOC isolation and characterization

Figure 1A shows representative phase contrast microscopy images of the mononuclear cell cultures following plating. The adherent cells exhibited a heterogeneous morphology. Many round, monocyte-like cells were seen as well as a number of spread flattened cells that were mixed with spindle-like cells. Media were changed every other day and the number of rounded cells diminished over the course of approximately 5 weeks. Cultures were monitored daily. At between 9 and 23 days of culture small outgrowth colonies of approximately 30–100 cells were observed. The colonies had a cobblestone morphology (see Fig. 1B, C) and rapidly proliferated. Colonies were trypsinized and replated in separate culture dishes for expansion.

FIG. 1.

(A) The mononuclear fraction of blood plated onto fibronectin-coated tissue culture polystyrene following 3 days in culture is shown using phase contrast microscopy. (B, C) Endothelial progenitor outgrowth colonies formed after 9–23 days in culture and grew to confluence showing a cobblestone-like morphology. Scale bar=50 μm. (D) Representative flow cytometry histograms (EOC, passage 3) show analysis of cultured EOC protein expression. Black outlines the unstained negative control. Solid histograms are the specific antibody labeled cell samples. (E) Quantification of flow cytometry analysis. Cells with fluorescence values >90% of the negative control were considered positive. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation, n=3. EOC, endothelial outgrowth cell; vWF, von Willebrand factor; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2; eNOS, nitric oxide synthase 3. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

Flow cytometry was used as a semi-quantitative method to investigate EOC protein expression. Figure 1D shows representative histograms of EOCs labeled for expression of common endothelial and monocyte markers. Flow cytometry data from three independent experiments are compiled in Figure 1E. Cells with fluorescence values >90% of the negative control value were considered positive. EOCs were strongly positive for vWF, ve-cadherin, ulex lectin, CD31, VEGFR1, eNOS, and CD105 with >90% of the cells positive for each of these markers. EOCs were weakly positive for thrombomodulin and VEGR2 (23% and 36%, respectively) and showed minimal expression of the monocytic marker, CD14 (9%).

Cell morphology

At confluence, ECs and EOCs displayed very similar polygonal or “cobblestone” morphologies, distinct nuclear regions, and clearly visible cell borders. As shown in Figure 2A, when both cell types were grown on collagen slides and subjected to 15 dynes/cm2, their cellular morphologies became altered in response to flow. Static ECs and EOCs had dense peripheral bands of F-actin, which reorganized into elongated fibers oriented parallel to the flow axis following 24 h of shear exposure.

FIG. 2.

(A) Rhodamine phalloidin staining of F-actin in cells exposed to steady laminar shear stress (15 dynes/cm2, 24 h) compared with static controls. Hoechst 33258 was used as a nuclear counterstain. Scale bar=50 μm. (B) Shape index and (C) angle of orientation were quantified (mean±SEM, n≥40). * indicates p<0.05 (ANOVA, Tukey post hoc). SEM, standard error of the mean; ANOVA, analysis of variance; EC, endothelial cell. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

Both cells types showed a significant (p<0.05) decrease in SI when exposed to shear stress for 24 h, (see Fig. 2B), but ECs elongated to a greater extent than EOCs (p<0.05). ECs and EOCs each had a statistically significant decrease (p<0.05) in the angle of orientation (indicating alignment in the direction of flow) following 24 h in a steady, laminar shear stress environment. There was no significant (p>0.05) difference between the two cell types (Fig. 2C).

Quantification of gene expression

Microarrays were used to compare gene expression by EOCs and ECs under both static and shear stress conditions. Table 2 lists 15 genes from the microarray results that are related to procoagulant (lower seven genes in Table 2) and anticoagulant (upper eight genes in Table 2) cell functions. Fold changes >1.5 or <0.667 were considered more dramatic and are therefore highlighted in Table 2. For these dramatic changes, the light gray values indicate a relative anticoagulant phenotype (upregulation of anticoagulant gene or downregulation of procoagulant gene), while dark gray values indicate a relative procoagulant phenotype (upregulation of procoagulant gene or downregulation of anticoagulant gene). Two genes (prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2, PTGS2, and the thrombospondin type I domain, containing 2, THSD2) are listed twice due to duplicate spots on the Agilent array. These genes serve as technical replicates on the same array slide. The data for the two replicates were consistent across six of eight comparisons. In two cases (PTGS2–Static: EOC vs. EC and THSD2–EOC: Shear vs. Static), one data point indicated upregulation and the second data point was not significantly changed. The majority of coagulation-associated genes (with either procoagulant or anticoagulant functions) were shear stress-responsive in ECs (12 of 15) while less than one-half of those genes were altered by shear in EOCs (7 of 15). Compared to ECs, EOCs showed a similar response to shear stress in four of the genes. For plasminogen activator, urokinase, ECs showed an increase in gene expression, while EOCs displayed a shear-dependent decrease in gene expression. Shear stress produced an overall increase in anticoagulant gene expression (seven of nine genes) in ECs, a finding that was not consistent with the EOC response to shear. In EOCs, only thrombomodulin expression was significantly upregulated (1.4-fold) by shear stress. In contrast, ECs showed no significant alteration in thrombomodulin expression with shear stress. Under static conditions, EOCs expressed five anticoagulant genes to a greater extent than ECs, and four procoagulant genes to a lesser extent than ECs. When both cell types were exposed to shear stress, the expression of procoagulant and anticoagulant genes in EOCs versus ECs was more heterogeneous, with the relative expression by EOCs of six genes indicative of a procoagulant phenotype and six genes indicative of an anticoagulant phenotype.

Table 2.

Gene Expression by Endothelial Outgrowth Cells and Endothelial Cells Under Static and Shear Stress Conditions

| |

|

|

Shear versus static |

EOC versus EC |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Systematic name | EC | EOC | Static | Shear | |

| Anticoagulant genes | Annexin A5 | NM_001154 | 1.512c | 1.148 | 1.088 | 0.826a |

| Plasminogen activator, tissue | NM_000930 | 0.424c | 0.378c | 1.311b | 1.166a | |

| Plasminogen activator, urokinase | NM_002658 | 1.580a | 0.669a | 1.828b | 0.774 | |

| Plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor | NM_001005377 | 4.409b | 0.837 | 4.676b | 0.888 | |

| Prostaglandin 12 (prostacyclin) synthase | NM_000961 | 0.363c | 0.590b | 0.605b | 0.982 | |

| Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | NM_000963 | 2.854c | 1.197 | 1.272 | 0.534c | |

| Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | NM_000963 | 3.253c | 1.099 | 1.319 | 0.446c | |

| Endothelial protein C receptor | NM_006404 | 1.242c | 0.803 | 4.158c | 2.689c | |

| Tissue factor pathway inhibitor | NM_006287 | 1.357b | 0.924 | 0.798 | 0.543c | |

| Thrombomodulin | NM_000361 | 0.999 | 1.404a | 1.787b | 2.511b | |

| Procoagulant genes | Factor II (thrombin) | NM_000506 | 0.973 | 1.08 | 1.422c | 1.578b |

| Factor III (tissue factor) | NM_001993 | 3.628c | 0.864 | 1.147 | 0.273b | |

| Factor VII | NM_000131 | 0.969 | 1.323a | 1.132 | 1.546b | |

| Factor VIII-associated (intronic transcript) 1 | NM_012151 | 1.014 | 1.097 | 0.743b | 0.803a | |

| Factor XIII, B polypeptide | NM_001994 | 0.335b | 0.578b | 1.053 | 1.819a | |

| Thrombospondin, type I, domain containing 1 | NM_018676 | 1.325b | 1.707c | 0.792a | 1.02 | |

| Thrombospondin, type I, domain containing 2 | NM_032784 | 1.168 | 0.951 | 0.272c | 0.221c | |

| Thrombospondin, type I, domain containing 2 | NM_032784 | 1.929a | 0.896 | 0.642a | 0.298c | |

Fold changes measured using microarray analyses. Light gray values indicate anticoagulant phenotype and dark gray values indicate procoagulant phenotype.

p≤0.05; bp≤0.01; cp≤0.001.

EC, endothelial cell; EOC, endothelial outgrowth cell.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was used to quantify gene expression of selected genes expressed by ECs and EOCs as shown in Figure 3. Under static conditions, ECs and EOCs both showed similar (p>0.05) levels of thrombomodulin expression. When exposed to shear stress, ECs responded with a slight but not significant (p>0.05) increase in thrombomodulin, while EOCs responded with a greater than threefold (p<0.05) increase in thrombomodulin expression. Figure 3 shows the expression level of nitric oxide synthase 3 (eNOS) mRNA under static cell culture conditions, where expression levels were seen to be lower for EOCs than ECs (p<0.05). Following 24 h of shear stress, both EOC and EC eNOS mRNA expression increased (p<0.05). EOCs, message levels nearly doubled in the presence of shear stress, resulting in expression levels that equaled the EC static expression levels, but still were significantly lower than those seen with ECs following shear exposure (p<0.05). Under static conditions, ECs exhibited significantly more tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) mRNA expression (p<0.05) than EOCs. When exposed to shear stress, TFPI expression was upregulated (p<0.05) in both cell types. Despite the increase in TFPI expression seen following shear stress exposure, EOCs still showed significantly less TFPI than ECs (p<0.05). For ECs, shear stress caused a significant upregulation (6.5-fold) of tissue factor mRNA (p<0.05) while shear stress did not augment EOC tissue factor expression over static levels (p>0.05). Under static flow conditions, ECs showed slightly more tissue factor expression than the EOC samples (p<0.05). Figure 3 also shows the vWF gene expression data for both ECs and EOCs under conditions of both static and shear stress exposure. Shear stress caused a significant downregulation of vWF mRNA in ECs compared to static conditions (p<0.05). EOC vWF mRNA levels under static conditions were not different than EC static levels (p<0.05), and following shear stress exposure. Although EOCs mRNA levels of vWF rose slightly, the difference was not significant compared to the results with static control samples (p<0.05).

FIG. 3.

Thrombomodulin, nitric oxide synthase 3 (eNOS), tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), tissue factor (F3), and vWF gene expression in ECs and EOCs was determined by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. mRNA expression was quantified in cells exposed to steady laminar shear stress (15 dynes/cm2, 24 h) and compared with static controls (mean±SEM, n=9). * indicates p<0.05 (ANOVA, Tukey post hoc).

Protein expression and thrombogenic functionality

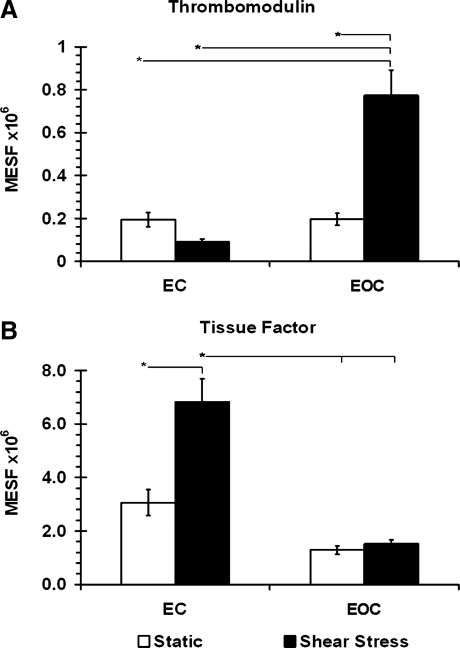

Using flow cytometry, levels of cellular protein expression for two key coagulation-associated molecules were investigated in ECs and EOCs. Antibodies specific for thrombomodulin and tissue factor were used to independently label the proteins expressed on the cell surfaces followed by quantification relative to fluorescent standards. Figure 4A shows the cell surface protein expression of thrombomodulin for both ECs and EOCs under static and shear conditions. There was no significant difference in thrombomodulin protein expression between ECs and EOCs under static conditions (p>0.05). This basal level of expression was unchanged in ECs exposed to shear (p>0.05); however, in EOCs shear caused a significant 3.9-fold increase in thrombomodulin protein (p<0.05). Figure 4B shows the flow cytometric results for tissue factor protein expression. The opposite trend was seen for tissue factor protein expression compared to thrombomodulin expression. Similarly, under static conditions there was no significant difference in basal tissue factor protein expression by ECs and EOCs (p>0.05). Following shear stress exposure, EOC tissue factor protein remained unchanged as compared to static conditions (p<0.05), while EC tissue factor protein levels more than doubled (p<0.05).

FIG. 4.

(A) Thrombomodulin and (B) tissue factor cell surface protein expression in EC and EOC determined by flow cytometry. Cells exposed to steady laminar shear stress (15 dynes/cm2, 24 h) were compared with static controls (mean±SEM, n≥9). * indicates p<0.05 (ANOVA, Tukey post hoc).

Given the significant changes in thrombomodulin gene and protein expression by the shear stress stimulated EOCs compared to static EOCs, an APC functional assay was performed to determine the role of the shear stress stimulation on the ability of EOCs to produce APC. The shear stress stimulated EOCs produced statistically more APC compared to matched static controls (Fig. 5) with an average increase of 80% (p<0.05, paired t-test).

FIG. 5.

Generation of activated protein C (APC) by EOCs under static and steady laminar shear stress (15 dynes/cm2, 24 h) conditions. Significantly more APC was generated per cell under shear stress conditions compared with static controls (mean±SEM, n=8). * indicates p<0.05 (paired t-test).

Discussion

EOCs have been investigated as a source of endothelium for vascular tissue engineering applications. EOCs were readily isolated from whole blood, without the need to harvest other tissues. While their outgrowth time (5 to 22 days) prevents their use in emergency situations, their rapid proliferation rates3–10 provide ample cells numbers. Although there have been several investigations of EOCs as a cell source for vascular tissue engineering,3,8,11,13,21 the coagulant phenotype of EOCs and its relationship to hemodynamic forces, is not well characterized.

As the interface between flowing blood and the vessel wall, the endothelium maintains vascular homeostasis by regulating thrombosis and hemostasis, including the production and inactivation of thrombin, the aggregation of blood platelets, and the control of fibrinolysis. ECs, as a coating for tissue engineered vascular grafts, should specifically maintain a minimally thrombogenic interface. While hemodynamic shear force is a well-recognized modulator of vascular EC phenotype, and has been implicated in both vascular function and dysfunction, relatively little is known about the role of hemodynamics in EOC biology. Since the ability of EOCs to respond to shear stress is critical to their use in vascular tissue engineering, we compared the hemostatic phenotype of EOCs under static and shear conditions to that of mature ECs.

Baboon EOCs showed an endothelial-like phenotype, a finding similar to previously published studies.7,9,11,12,14,22–28 The emergence of EOC outgrowth colonies between 9 and 23 days of culture in growth factor supplemented medium is also consistent with other investigations reporting the appearance of colonies between 5 and 22 days after plating the peripheral blood mononuclear cell fraction onto protein coated culture dishes.7,22–25,29 Based on the microarray data for cells studied under static conditions, the EOCs exhibited a predominantly anticoagulant phenotype as compared to ECs. EOCs had greater expression of five anticoagulant genes and decreased expression of four procoagulant genes. qRT-PCR analysis of EOCs versus ECs under static conditions indicated a significant decrease in expression of tissue factor and TFPI, neither of which was significantly different in the microarray analyses. Interestingly, the qRT-PCR results revealed a decrease in EOC expression of eNOS. eNOS gene expression by EOCs under static conditions has also been reported previously to be lower than that of mature ECs,3,9,14,23,25 even though EOC expression of eNOS and release of nitric oxide is responsive to shear stress.

Mature EC responses to shear stress are well documented. The endothelial cytoskeleton undergoes a reorganization that allows ECs to align in the direction of flow, with aligned cytoskeletal components (actin and microtubules). In this study, EOCs responded to shear stress by elongating and orienting parallel to the direction of flow when exposed to 15 dynes/cm2 steady laminar shear stress for 24 h. Quantitatively, EOCs on absorbed collagen demonstrated a cytoskeletal reorganization and alignment that mimicked the response of baboon carotid artery ECs in the same system. This finding was consistent with previous studies that used bovine aortic ECs and human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) on two-dimensional protein substrates,19,30,31 as well as recent studies with EOCs.3,9

Maintenance of hemostasis is a critical function of the endothelium, and hemodynamic forces have been shown to regulate many of the coagulation-associated proteins in these cells. In this study, gene and protein expression of both procoagulant and anticoagulant molecules were investigated. Shear stress upregulated a number of anticoagulant-associated genes in ECs, while EOCs were less responsive to shear exposure in this system. The qRT-PCR analyses confirmed the microarray analysis. One anticoagulant protein, thrombomodulin, stood out as being differentially upregulated by shear stress in EOCs but not in ECs. Thrombomodulin is a cell surface protein that binds thrombin; the thrombin:thrombomodulin complex then serves to dramatically accelerate the activation of protein C. APC in turn downregulates the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin, thereby producing an anticoagulant effect. The interaction between thrombomodulin and shear stress has been demonstrated in saphenous vein grafts.32 In cell culture, thrombomodulin expression has been shown to vary with shear stress magnitude and duration, although results have varied as a function of species and vascular cell type.33,34 EOCs increased thrombomodulin mRNA levels 3.3-fold and protein levels 3.9-fold in response to flow. Additionally, fluid shear stress increased the production of APC by EOCs an average of 80% compared to static controls. Static cultures of EOCs have been shown to express thrombomodulin,35 consistent with their “endothelial-like” phenotype; however, to our knowledge this is the first demonstration that thrombomodulin expression and function in EOCs are upregulated by fluid shear stress. This finding may have important implications for EOC use in blood-contacting applications.

Shear stress differentially regulated tissue factor gene and protein expression in EOCs and ECs. Specifically, tissue factor was upregulated by ECs, but not EOCs, in response to shear stress. Several hemodynamic factors including shear stress have previously been shown to increase tissue factor expression in mature vascular ECs.36–40 Fluid shear stress of 6 dynes/cm2 for 24 h downregulated human EOC gene expression of tissue factor under basal conditions, yet had no effect on tissue factor activity or TNF-α induced gene expression of tissue factor.41 Normally, quiescent vascular endothelium does not support coagulation and thrombosis resulting in undetectable levels of tissue factor in vivo42; however, cultured HUVECs produce low levels of tissue factor mRNA,43,44 consistent with the findings of this study. Under static conditions, TNF-α treatment of EOCs from both adult and cord blood sources induced an increase in tissue factor gene expression similar to HUVECs.45 Under noninflammatory conditions, the shear stress induced high thrombomodulin expression and activity with low tissue factor expression by EOCs indicate that the EOCs may have a more anticoagulant phenotype compared to mature ECs.

The gene expression of vWF, an important prothrombogenic protein, was also investigated. vWF supports thrombosis and hemostasis by binding to collagen at sites of vessel injury. The bound vWF then serves to localize circulating platelets to those sites through processes of platelet adhesion, aggregation, and platelet granular release. Shear stress conditioning did not significantly alter the gene expression of vWF by EOCs. Under static conditions EOCs expressed vWF at a level that was comparable to that seen with ECs. In contrast to EOCs, shear exposure significantly reduced the gene expression of vWF by ECs. The practical consequence of this functional difference would be relevant during injury when vWF bound to collagen in the basement membrane may increase platelet adhesion.

Shear stress stimulation of mature vascular ECs increases eNOS gene expression and causes the release of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator.46 While the basal level of eNOS expression by EOCs is lower than ECs, in agreement with human EOCs,46 our baboon EOCs did respond to shear stress similar to mature ECs by increasing eNOS gene expression. Recently human EOCs from healthy individuals and patients with coronary artery disease were shown to increase both eNOS expression and NO release.9 TFPI, an anticoagulant that inhibits tissue factor, was also significantly upregulated by shear exposure in both ECs and EOCs. These results are consistent with previous reports indicating that shear stress upregulates the synthesis and release of TFPI, resulting in enhanced anticoagulant activity of mature ECs.47,48 The present study showed that EOCs express TFPI in static culture, with elevated expression following exposure to shear stress. This increase in TFPI expression, along with the ability of EOCs to release NO under shear stress, are consistent with observations of increased patency for endothelialized carotid interposition grafts.11 Additionally, in an ovine model, EOC-seeded decellularized arteries remained patent for 130 days compared to nonseeded grafts that occluded in an average of 15 days.11 The EOCs used in that study were hemodynamically preconditioned at 25 dynes/cm2 for 2 days (after 2 days of ramping flow). Functional evaluation of the explanted tissue-engineered grafts indicated NO-mediated relaxation. These studies support the concept that EOC phenotype may be an important determinant of graft outcomes.

The present study demonstrates that EOCs and mature ECs respond differently with respect to hemostatic gene expression under shear stress. A limitation of this study is the lack of interaction between smooth muscle cells and the EOCs. Smooth muscle cells are known to influence the functionality of mature ECs and are likely to affect the thrombogenic phenotype of EOCs. Further studies will be needed to clarify complex relationships between flow-induced gene expression on the overall hemostatic profile of surfaces endothelialized using EOCs as well as effects of coculture with smooth muscle cells.

Conclusions

EOCs derived from peripheral blood are responsive to shear stress, resulting in cytoskeletal reorganization as well as alterations in their transcriptional profile, antigen presentation, and antithrombogenic functionality. In static cultures, EOCs mimic mature vascular ECs with respect to thrombomodulin and vWF mRNA expression, as well as thrombomodulin and tissue factor protein expression, but have lower mRNA levels of TFPI, eNOS, and tissue factor. Fluid shear stress causes EOCs to upregulate anticoagulant factors (thrombomodulin, TFPI) and eNOS gene expression without significantly altering the basal expression of procoagulant factors (tissue factor and vWF). The fluid shear stress-induced upregulation of thrombomodulin gene and protein expression resulted in an increase in production of APC, a potent anticoagulant.

We have now shown that application of fluid shear stress can be used to modulate the phenotype of a potentially autologous EC source obtained from minimally invasive peripheral blood samples. This strategy for manipulation of EOC phenotype may be important for the tissue engineering of less thrombogenic cardiovascular implants.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation through ERC Award Number EEC-9731643 and NIH R01-HL095474. The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Gary Gibbons and the team at Morehouse School of Medicine including Dr. Leonard Anderson, Dr. Xing Hu and Dr. Guoshen Wang in conducting microarray analysis. The expert technical assistance Dr. Minhui Ma, Dr. James Costello, and Dr. Tiffany Brown is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Meinhart J.G. Deutsch M. Fischlein T. Howanietz N. Froschl A. Zilla P. Clinical autologous in vitro endothelialization of 153 infrainguinal eptfe grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:S327. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutsch M. Meinhart J. Zilla P. Howanietz N. Gorlitzer M. Froeschl A. Stuempflen A. Bezuidenhout D. Grabenwoeger M. Long-term experience in autologous in vitro endothelialization of infrainguinal eptfe grafts. J Vasc Surg. 49:352. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.101. discussion 362, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinds M.T. Ma M. Tran N. Ensley A.E. Kladakis S.M. Vartanian K.B. Markway B.D. Nerem R.M. Hanson S.R. Potential of baboon endothelial progenitor cells for tissue engineered vascular grafts. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;86:804. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin Y. Weisdorf D.J. Solovey A. Hebbel R.P. Origins of circulating endothelial cells and endothelial outgrowth from blood. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:71. doi: 10.1172/JCI8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melero-Martin J.M. Khan Z.A. Picard A. Wu X. Paruchuri S. Bischoff J. In vivo vasculogenic potential of human blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2007;109:4761. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu X. Rabkin-Aikawa E. Guleserian K.J. Perry T.E. Masuda Y. Sutherland F.W. Schoen F.J. Mayer J.E., Jr. Bischoff J. Tissue-engineered microvessels on three-dimensional biodegradable scaffolds using human endothelial progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H480. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01232.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingram D.A. Mead L.E. Tanaka H. Meade V. Fenoglio A. Mortell K. Pollok K. Ferkowicz M.J. Gilley D. Yoder M.C. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;104:2752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen J. Khan S. Serrano M.C. Ameer G. Characterization of porcine circulating progenitor cells: toward a functional endothelium. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:183. doi: 10.1089/ten.a.2007.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroncek J.D. Grant B.S. Brown M.A. Povsic T.J. Truskey G.A. Reichert W.M. Comparison of endothelial cell phenotypic markers of late-outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells isolated from patients with coronary artery disease and healthy volunteers. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3473. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reinisch A. Hofmann N.A. Obenauf A.C. Kashofer K. Rohde E. Schallmoser K. Flicker K. Lanzer G. Linkesch W. Speicher M.R. Strunk D. Humanized large-scale expanded endothelial colony-forming cells function in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2009;113:6716. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-181362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaushal S. Amiel G.E. Guleserian K.J. Shapira O.M. Perry T. Sutherland F.W. Rabkin E. Moran A.M. Schoen F.J. Atala A. Soker S. Bischoff J. Mayer J.E., Jr Functional small-diameter neovessels created using endothelial progenitor cells expanded ex vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7:1035. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stachelek S.J. Alferiev I. Connolly J.M. Sacks M. Hebbel R.P. Bianco R. Levy R.J. Cholesterol-modified polyurethane valve cusps demonstrate blood outgrowth endothelial cell adhesion post-seeding in vitro and in vivo. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:47. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt D. Breymann C. Weber A. Guenter C.I. Neuenschwander S. Zund G. Turina M. Hoerstrup S.P. Umbilical cord blood derived endothelial progenitor cells for tissue engineering of vascular grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:2094. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirota T. He H. Yasui H. Matsuda T. Human endothelial progenitor cell-seeded hybrid graft: proliferative and antithrombogenic potentials in vitro and fabrication processing. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:127. doi: 10.1089/107632703762687609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sieminski A.L. Hebbel R.P. Gooch K.J. Improved microvascular network in vitro by human blood outgrowth endothelial cells relative to vessel-derived endothelial cells. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1332. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hristov M. Weber C. Endothelial progenitor cells: characterization, pathophysiology, and possible clinical relevance. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:498. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hristov M. Erl W. Weber P.C. Endothelial progenitor cells: isolation and characterization. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2003;13:201. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(03)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin P.H. Chen C. Bush R.L. Yao Q. Lumsden A.B. Hanson S.R. Small-caliber heparin-coated eptfe grafts reduce platelet deposition and neointimal hyperplasia in a baboon model. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:1322. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levesque M.J. Nerem R.M. The elongation and orientation of cultured endothelial cells in response to shear stress. J Biomech Eng. 1985;107:341. doi: 10.1115/1.3138567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byers B.A. Garcia A.J. Exogenous runx2 expression enhances in vitro osteoblastic differentiation and mineralization in primary bone marrow stromal cells. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1623. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He H. Shirota T. Yasui H. Matsuda T. Canine endothelial progenitor cell-lined hybrid vascular graft with nonthrombogenic potential. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:455. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(02)73264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griese D.P. Ehsan A. Melo L.G. Kong D. Zhang L. Mann M.J. Pratt R.E. Mulligan R.C. Dzau V.J. Isolation and transplantation of autologous circulating endothelial cells into denuded vessels and prosthetic grafts: implications for cell-based vascular therapy. Circulation. 2003;108:2710. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096490.16596.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulati R. Jevremovic D. Peterson T.E. Chatterjee S. Shah V. Vile R.G. Simari R.D. Diverse origin and function of cells with endothelial phenotype obtained from adult human blood. Circ Res. 2003;93:1023. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000105569.77539.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He T. Peterson T.E. Holmuhamedov E.L. Terzic A. Caplice N.M. Oberley L.W. Katusic Z.S. Human endothelial progenitor cells tolerate oxidative stress due to intrinsically high expression of manganese superoxide dismutase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2021. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000142810.27849.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hur J. Yoon C.H. Kim H.S. Choi J.H. Kang H.J. Hwang K.K. Oh B.H. Lee M.M. Park Y.B. Characterization of two types of endothelial progenitor cells and their different contributions to neovasculogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:288. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000114236.77009.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon C.H. Hur J. Park K.W. Kim J.H. Lee C.S. Oh I.Y. Kim T.Y. Cho H.J. Kang H.J. Chae I.H. Yang H.K. Oh B.H. Park Y.B. Kim H.S. Synergistic neovascularization by mixed transplantation of early endothelial progenitor cells and late outgrowth endothelial cells: the role of angiogenic cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. Circulation. 2005;112:1618. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.503433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto K. Takahashi T. Asahara T. Ohura N. Sokabe T. Kamiya A. Ando J. Proliferation, differentiation, and tube formation by endothelial progenitor cells in response to shear stress. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:2081. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00232.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eggermann J. Kliche S. Jarmy G. Hoffmann K. Mayr-Beyrle U. Debatin K.M. Waltenberger J. Beltinger C. Endothelial progenitor cell culture and differentiation in vitro: a methodological comparison using human umbilical cord blood. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:478. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossig L. Urbich C. Bruhl T. Dernbach E. Heeschen C. Chavakis E. Sasaki K. Aicher D. Diehl F. Seeger F. Potente M. Aicher A. Zanetta L. Dejana E. Zeiher A.M. Dimmeler S. Histone deacetylase activity is essential for the expression of hoxa9 and for endothelial commitment of progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1825. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dewey C.F., Jr. Bussolari S.R. Gimbrone M.A., Jr. Davies P.F. The dynamic response of vascular endothelial cells to fluid shear stress. J Biomech Eng. 1981;103:177. doi: 10.1115/1.3138276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eskin S.G. Ives C.L. McIntire L.V. Navarro L.T. Response of cultured endothelial cells to steady flow. Microvasc Res. 1984;28:87. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(84)90031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gosling M. Golledge J. Turner R.J. Powell J.T. Arterial flow conditions downregulate thrombomodulin on saphenous vein endothelium. Circulation. 1999;99:1047. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.8.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malek A.M. Jackman R. Rosenberg R.D. Izumo S. Endothelial expression of thrombomodulin is reversibly regulated by fluid shear stress. Circ Res. 1994;74:852. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.5.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takada Y. Shinkai F. Kondo S. Yamamoto S. Tsuboi H. Korenaga R. Ando J. Fluid shear stress increases the expression of thrombomodulin by cultured human endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:1345. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bagley R.G. Walter-Yohrling J. Cao X. Weber W. Simons B. Cook B.P. Chartrand S.D. Wang C. Madden S.L. Teicher B.A. Endothelial precursor cells as a model of tumor endothelium: characterization and comparison with mature endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grabowski E.F. Lam F.P. Endothelial cell function, including tissue factor expression, under flow conditions. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van't Veer C. Hackeng T.M. Delahaye C. Sixma J.J. Bouma B.N. Activated factor x and thrombin formation triggered by tissue factor on endothelial cell matrix in a flow model: effect of the tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Blood. 1994;84:1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grabowski E.F. Zuckerman D.B. Nemerson Y. The functional expression of tissue factor by fibroblasts and endothelial cells under flow conditions. Blood. 1993;81:3265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazzolai L. Silacci P. Bouzourene K. Daniel F. Brunner H. Hayoz D. Tissue factor activity is upregulated in human endothelial cells exposed to oscillatory shear stress. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87:1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsumoto Y. Kawai Y. Watanabe K. Sakai K. Murata M. Handa M. Nakamura S. Ikeda Y. Fluid shear stress attenuates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced tissue factor expression in cultured human endothelial cells. Blood. 1998;91:4164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lund T. Hermansen S.E. Andreasen T.V. Olsen J.O. Osterud B. Myrmel T. Ytrehus K. Shear stress regulates inflammatory and thrombogenic gene transcripts in cultured human endothelial progenitor cells. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:582. doi: 10.1160/TH09-12-0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nemerson Y. Tissue factor and hemostasis. Blood. 1988;71:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crossman D.C. Carr D.P. Tuddenham E.G. Pearson J.D. McVey J.H. The regulation of tissue factor mrna in human endothelial cells in response to endotoxin or phorbol ester. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher K.L. Gorman C.M. Vehar G.A. O'Brien D.P. Lawn R.M. Cloning and expression of human tissue factor cdna. Thromb Res. 1987;48:89. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(87)90349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuccuini W. Poitevin S. Poitevin G. Dignat-George F. Cornillet-Lefebvre P. Sabatier F. Nguyen P. Tissue factor up-regulation in proinflammatory conditions confers thrombin generation capacity to endothelial colony-forming cells without influencing non-coagulant properties in vitro. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2042. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boo Y.C. Jo H. Flow-dependent regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: role of protein kinases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C499. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00122.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westmuckett A.D. Lupu C. Roquefeuil S. Krausz T. Kakkar V.V. Lupu F. Fluid flow induces upregulation of synthesis and release of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2474. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grabowski E.F. Reininger A.J. Petteruti P.G. Tsukurov O. Orkin R.W. Shear stress decreases endothelial cell tissue factor activity by augmenting secretion of tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:157. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]