Abstract

Background

Erythropoietin (EPO), originally identified as a hematopoietic growth factor produced in the kidney and fetal liver, is also endogenously expressed in the central nervous system (CNS). EPO in the CNS, mainly produced in astrocytes, is induced under hypoxic conditions in a hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-dependent manner and plays a dominant role in neuroprotection and neurogenesis. We investigated the effect of general anesthetics on EPO expression in the mouse brain and primary cultured astrocytes.

Methodology/Principal Findings

BALB/c mice were exposed to 10% oxygen with isoflurane at various concentrations (0.10–1.0%). Expression of EPO mRNA in the brain was studied, and the effects of sevoflurane, halothane, nitrous oxide, pentobarbital, ketamine, and propofol were investigated. In addition, expression of HIF-2α protein was studied by immunoblotting. Hypoxia-induced EPO mRNA expression in the brain was significantly suppressed by isoflurane in a concentration-dependent manner. A similar effect was confirmed for all other general anesthetics. Hypoxia-inducible expression of HIF-2α protein was also significantly suppressed with isoflurane. In the experiments using primary cultured astrocytes, isoflurane, pentobarbital, and ketamine suppressed hypoxia-inducible expression of HIF-2α protein and EPO mRNA.

Conclusions/Significance

Taken together, our results indicate that general anesthetics suppress activation of HIF-2 and inhibit hypoxia-induced EPO upregulation in the mouse brain through a direct effect on astrocytes.

Introduction

Ischemic and hypoxic insults to the brain during surgery and anesthesia result in life-threatening complications including stroke. These complications occur at the rate of 0.08–0.7% in general surgery and 1.4–3.8% in cardiac surgery [1]. Pharmacologic interventions, including calcium channel blockers, free radical scavengers, and glutamate antagonists, have been introduced to prevent and/or ameliorate stroke [2]. Erythropoietin (EPO) is also recognized as a promising molecule to introduce neuroprotection, and encouraging results have been obtained from clinical trials involving stroke patients [3], [4], [5]. Originally, EPO was widely known as a hematopoietic growth factor produced in the kidney and fetal liver [5]. Further investigations expanded this review by showing that EPO and EPO receptor (EPOR) are present in the human brain and synthesized locally by astrocytes and neurons [6], [7], [8], [9]. It is well documented in both experimental and clinical studies that EPO produced in the brain acts in a paracrine or autocrine manner to provide neuroprotection [10], [11]. Endogenous EPO in the brain is produced in an oxygen tension-dependent manner [12] and reduces brain damage by inhibiting apoptosis [13], suppressing glutamate release [14], and reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines [15].

Hypoxia-induced EPO upregulation in the brain is regulated mainly by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 and HIF-2 [16]. HIF is a transcriptional factor that acts as a key regulator in cells exposed to low oxygen [17], [18]. In fact, HIF-1 was originally cloned as a transcription factor responsible for hypoxia-induced EPO expression [17]. HIF is a heterodimeric DNA-binding complex composed of two basic helix-loop-helix proteins of the PER-ARNT-SIM (PAS) family: the constitutive non-oxygen-responsive subunit HIF-1β (also termed as the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator: ARNT) and one of either of the hypoxia-inducible α-subunits HIF-1α or HIF-2α [19], [20]. HIF-α proteins are rapidly degraded in normoxia but highly induced by hypoxia [19], [20], [21]. HIF-1α and HIF-2α share significant sequence homology and both are regulated post-translationally by protein degradation [19], [20]. HIF-2α, originally termed endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1) because of its expression in endothelial cells, exhibits a more restricted expression pattern than HIF-1α [17], [22]. Although both HIF-α subunits are able to bind the consensus hypoxia-responsive element (HRE) in promoters that contain the sequence NCGTG, they seem to regulate a different set of target genes depending on the cellular context and oxygen concentration [23], [24]. The factors and molecular mechanisms that potentially determine this isoform-specific target gene selectivity remain poorly defined. Interestingly, although HIF-1α was originally identified to bind to HRE in the 3′-enhancer of the EPO gene, there is now considerable evidence that HIF-2α is the main HIF-α-subunit controlling EPO gene expression both in vitro and in vivo [25].

We previously reported that the volatile anesthetic halothane inhibits hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1 by distinct molecular mechanisms [26]. Recently, however, another volatile anesthetic, isoflurane, has been reported to upregulate HIF-1 activity in Hep3B cells [27], cultured rat hippocampal neurons [28], and rat myocardium [29]. Isoflurane-induced activation of HIF is now considered a possible mechanism of anesthetic preconditioning [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. However, in vivo experiments of the brain have not been reported, and while HIF-2 rather than HIF-1 mainly regulates EPO in the brain [32], the effect of general anesthetics on HIF-2 has not been well investigated. Considering the pivotal role of EPO in inducing neuroprotection, the influence of general anesthetics on EPO, especially in the brain, may have a major impact on perioperative clinical management. In the present study, we investigated the effect of general anesthetics, including isoflurane, on hypoxia-induced upregulation of EPO in the mouse brain and primary cultured astrocytes.

Results

Isoflurane inhibits the induction of EPO expression under hypoxic conditions in the brain, but does not affect EPO induction in the kidney

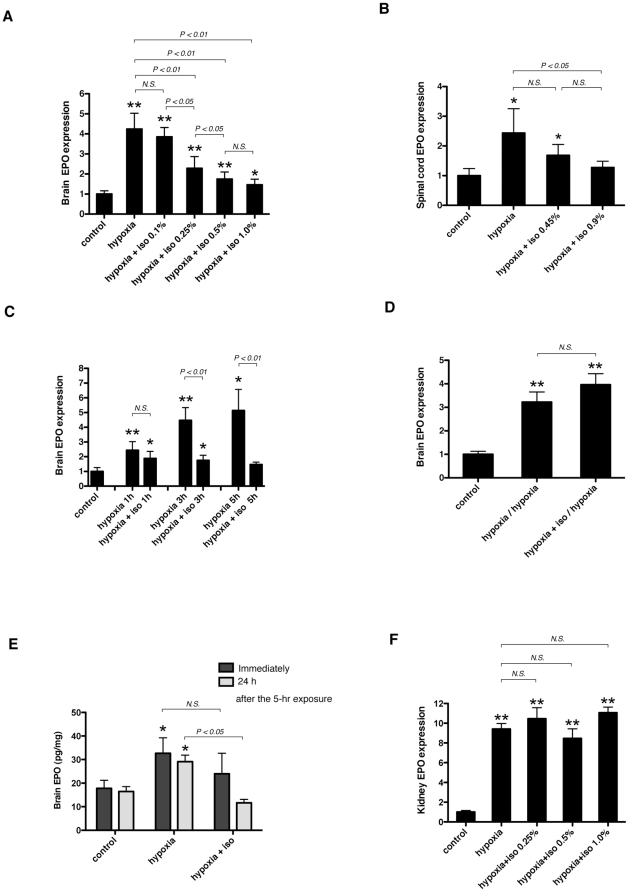

To examine the effect of general anesthetics on EPO expression under hypoxic conditions, we exposed 6-week-old BALB/c mice to 10% O2 (hypoxia) for 3 h with isoflurane. Hypoxic exposure significantly increased EPO mRNA expression and isoflurane suppressed hypoxia-induced EPO mRNA expression in a concentration-dependent manner in the mouse brain (Figure 1A) and spinal cord (Figure 1B). In the brain, a decrease was observed at 0.25% and maximal suppression was achieved at 0.5% (Figure 1A). Next, we performed a time course study with 0.5% isoflurane. Hypoxic exposure increased EPO mRNA time-dependently (Figure 1C). Isoflurane inhalation for more than 1 h significantly suppressed induction (Figure 1C). We re-exposed mice to hypoxia 24 h after hypoxic treatment with (hypoxia+iso/hypoxia) or without (hypoxia/hypoxia) 0.5% isoflurane to determine the reversibility of the suppressive effect of isoflurane on EPO mRNA in the brain. As shown in Figure 1D, hypoxia-induced upregulation of EPO mRNA was almost of a similar extent between the two groups (hypoxia/hypoxia and hypoxia+iso/hypoxia); therefore, the suppressive effect of isoflurane was not identified 24 h later. Next, in order to confirm the effect of isoflurane at the protein level, we measured EPO protein concentration in mouse brains using ELISA. We exposed mice to 10% O2 (hypoxia) for 5 h with or without 0.5% isoflurane. Hypoxic exposure induced a significant increase in EPO protein immediately after the treatment, and the effect of isoflurane was not apparent (Figure 1E). However, 24 h after the hypoxic exposure, EPO protein concentration decreased in the mice exposed to hypoxia with isoflurane, although still elevated in the mice without isoflurane (Figure 1E). Hypoxia has been reported to induce EPO mRNA upregulation in the kidney and brain [30]. Therefore, we measured EPO mRNA levels in the kidney. Hypoxic exposure significantly increased EPO mRNA in the kidney, but isoflurane did not affect the induction of EPO mRNA levels (Figure 1F).

Figure 1. Effect of isoflurane on EPO expression in mouse CNS and kidney.

(A, B, and F) Six-week-old BALB/c mice were exposed to 10% O2 (hypoxia) in the presence of various concentrations of isoflurane for 3 hours (n = 6–15), or (C) exposed to 10% O2 (hypoxia) with 0.5% isoflurane for the indicated periods of time. (D) 24 hours after the hypoxic exposure with or without 0.5% isoflurane, 6-week-old BALB/c mice were re-exposed to hypoxia (10% O2) for 3 hours. EPO mRNA in the brain (A, C, and D), spinal cord (B) and kidney (F) was assayed with real-time RT-PCR analysis. (E) Immediately or 24 hours after the 5-hour hypoxic (10% O2) exposure with or without 0.5% isoflurane, EPO protein concentration (pg/ml) in the brain was quantified with ELISA and divided by the total protein concentration (mg/ml) of each mouse brain. Number of animals per treatment conditions is 6 (C–E). Data are presented as mean ± SD. The expression levels of EPO were normalized to that of 18S and expressed relative to the mean of control mice (A, B, C, D and F). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus control, N.S.; not significant (Mann-Whitney U-test).

Sevoflurane, halothane, nitrous oxide (N2O), pentobarbital, ketamine,and propofol suppress hypoxia-induced up-regulation of EPO mRNA in mouse brains

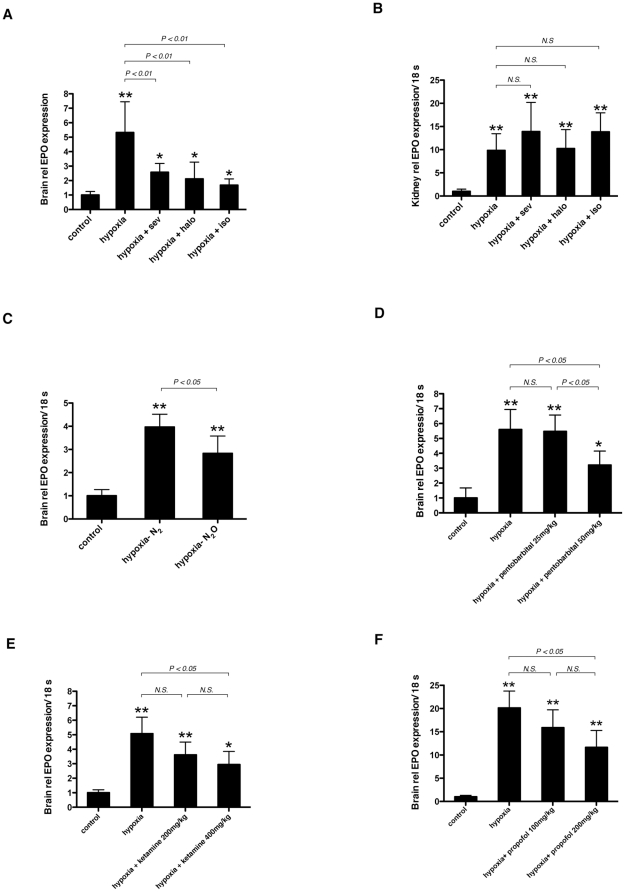

To examine whether the effect of isoflurane could be observed with other general anesthetics, we exposed 6-week-old BALB/c mice to 10% O2 with 0.5% sevoflurane or halothane. As in the case of isoflurane, both anesthetics also suppressed hypoxia-induced EPO upregulation in the brain (Figure 2A) but did not affect the expression of EPO in the kidney (Figure 2B). Next, we investigated the effect of nitrous oxide (N2O). We exposed mice to 10% O2 and 90% N2O (hypoxia-N2O group), compared with 10% O2 and 90% N2 (hypoxia-N2 group). EPO mRNA in the brains of the hypoxia-N2O group was significantly suppressed compared with that in the hypoxia-N2 group (Figure 2C). Finally, we tested the non-inhalational anesthetics pentobarbital, ketamine, and propofol. Fifty mg/kg pentobarbital (Figure 2D), 400 mg/kg ketamine (Figure 2E), and 200 mg/kg propofol (Figure 2F) also suppressed hypoxia-induced EPO mRNA upregulation in the brain.

Figure 2. Effect of various anesthetics on hypoxia-induced EPO upregulation in the brain.

(A, B) 6-week-old BALB/c mice were exposed to 10% O2 (hypoxia) in the presence of 0.5% sevoflurane, halothane or isoflurane for 3 hours. (C) 6-week-old mice were exposed to 10% O2, 90% N2O (hypoxia- N2O) for 3 hours and compared with 10% O2, 90% N2 (hypoxia- N2). (D–F) 6-week-old mice were exposed to 10% O2 with pentobarbital (D), ketamine (E) or propofol (F). In the all experiments, control mice were exposed to air without anesthetics (normoxia). EPO mRNA in the brain (A, C–F) and kidney (B) was assayed with real-time RT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). The expression levels of EPO were normalized to that of 18S and expressed relative to the mean of control mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus control, N.S.; not significant (Mann-Whitney U-test).

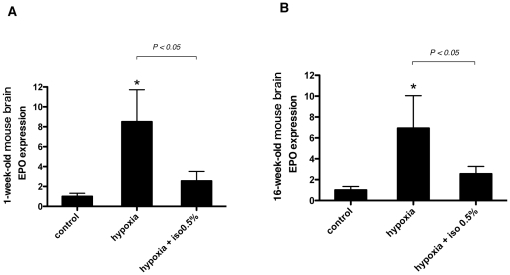

Isoflurane inhibits the induction of EPO expression under hypoxic conditions in the brain of one-week and sixteen-week old C57BL/6N CrSlc mice

Age is an important factor that influences the response to hypoxia-ischemia in the brain [33]. After our first experiment, we performed the same experiment in mice of other ages and species. One-week and sixteen-week-old C57BL/6N CrSlc mice were exposed to 10% O2 (hypoxia) for 3 h with 0.5% isoflurane. As with 6-week-old BALB/c mice, EPO mRNA induction was significantly suppressed with isoflurane in one-week (Figure 3A) and sixteen-week (Figure 3B) old mice.

Figure 3. Effect of age and species on hypoxic EPO induction in mice brains.

(A) 1-week and (B) 16-week-old C57BL/6N CrSlc mice were exposed to 10% O2 (hypoxia) in the presence of 0.5% isoflurane for 3 hours. Control mice were exposed to air without anesthetics (normoxia). EPO mRNA in the brain was assayed with real-time RT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3–5). The expression levels of EPO were normalized to that of 18S and expressed relative to the mean of control mice. *P<0.05 versus control (Mann-Whitney U-test).

Systemic hemodynamics

To exclude the possibility of secondary effects, including hypotension, influencing the brain's hypoxic responses, we examined the systemic hemodynamics of mice. Hemodynamic parameters including heart rate (HR), systolic (SAP), diastolic (DAP), and mean (MAP) arterial pressures were measured in 6-week-old BALB/c mice exposed to 10% O2 (hypoxia), 10% O2 with 0.5% isoflurane (hypoxia+iso), or 10% O2 with 0.5% sevoflurane (hypoxia+sev) for 3 h, compared with controls (Table 1). Control mice were exposed to air without anesthetics. SAP and MAP decreased in the hypoxia, hypoxia+iso, and hypoxia+sev groups compared to the control group. However, there were no significant differences in all hemodynamic parameters among the hypoxia, hypoxia+iso, and hypoxia+sev groups.

Table 1. Systemic hemodynamics.

| Mice | n | HR, beats/min | SAP, mmHg | DAP, mmHg | MAP, mmHg |

| Control | 7 | 450±70 | 115±13 | 62±15 | 80±12 |

| Hypoxia | 7 | 513±49 | 100±5.8* | 50±17 | 67±12* |

| Hypoxia+Iso | 6 | 463±77 | 93±8.8* | 42±7.3 | 58±5.6* |

| Hypoxia+Sev | 6 | 448±34 | 89±8.7* | 54±12 | 65±10* |

Six-week-old BALB/c mice were divided into 4 groups; control (exposed to air), hypoxia (exposed to 10% O2 for 3 hours), hypoxia+iso (exposed to 10% O2 with 0.5% isoflurane for 3 hours) and hypoxia+sev (exposed to 10% O2 with 0.5% sevoglurane for 3 hours). Immediately after the hypoxic exposure, heart rate and blood pressure were measured.

There were no significant differences in any of the parameters among hypoxia, hypoxia+iso and hypoxia+sev group mice. Values are shown as mean ± SD. * P<0.05 versus control.

HR = heart rate; SAP = systolic arterial pressure; DAP = diastolic arterial pressure; MAP = mean arterial pressur.

Isoflurane inhibits the induction of HIF-2α protein expression under hypoxic conditions in the brain of mice

EPO is induced under hypoxic conditions, mainly through activation of HIF-1 and HIF-2 [16], [34]. Therefore, we investigated the effect of isoflurane on the expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α proteins. We exposed 6-week-old BALB/c mice to 10% O2 (hypoxia) for 3 h with or without 0.5% isoflurane. Control mice were exposed to air without isoflurane (normoxia). The protein expression of HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and ARNT (HIF-1β) was investigated with an immunoblot assay. As shown in Figure 4A, HIF-1α protein was expressed under normoxic conditions and this expression was not significantly altered in response to either hypoxic exposure or isoflurane. In contrast, hypoxic exposure induced a marked accumulation of HIF-2α protein, which was clearly suppressed by isoflurane (Figure 4A). ARNT protein expression was almost stable under all conditions (Figure 4A). Next we assayed the expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α immunohistochemically, and found positive immunostaining of HIF-1α was observed globally in the frontal cortex under all conditions (Figure 4B). HIF-2α was also admitted to a certain degree under hypoxic condition, but barely observed under normoxia or hypoxia with isoflurane exposure (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Mechanism of suppression by isoflurane against EPO upregulation under hypoxic conditions.

(A) Expression analysis of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α, HIF-2α, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT, also termed as HIF-1β) in the whole brain by immunoblotting. 6-week-old BALB/c mice were exposed to air (control), 10% O2 (hypoxia) or 10% O2 with 0.5% isoflurane (hypoxia+iso) for 3 hours. Figures are representative of at least three independent experiments. (B) Immunohistochemical staining for HIF-1α and HIF-2α in the frontal cortex of 6-week-old BALB/c mice. Mice were exposed to air (control), 10% O2 (hypoxia) or 10% O2 with 0.5% isoflurane (hypoxia+iso) for 3 hours. Figures are representative of 6 slices of 3 mice. Scale bars: 100 µm.

Effect of isoflurane on the expression of HIF target genes

Despite significant similarities in their DNA binding and dimerization domains, it has been demonstrated that HIF-1 and HIF-2 have unique, as well as common, target genes [35]. As shown in Figure 5A, HIF-1 specifically regulates glycolytic genes, including lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), whereas HIF-2 exclusively regulates POU transcription factor Oct-4, cyclin D1, and transforming growth factor α (TGF-α) [35], [36]. Other hypoxia-inducible genes, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), and EPO, are regulated by both HIF-1 and HIF-2 in a cell-type-specific manner [35]. Therefore, we investigated the influence of hypoxia or isoflurane on HIF target genes in the mouse brain. VEGF mRNA, as well as EPO, was significantly induced by hypoxic exposure (10% O2, 3 h) and was significantly suppressed with isoflurane (0.5%) (Figure 5B). In contrast, the expression of LDHA did not change significantly with hypoxic exposure and isoflurane inhalation (Figure 5B). Next, we studied the change of HIF target genes in the kidney. Although hypoxic exposure significantly induced EPO mRNA in the kidney (Figure 1F), other HIF target genes, VEGF and LDHA, were not elevated but rather suppressed (Figure 5C). The effect of isoflurane on VEGF and LDHA was not significant (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Effect of isoflurne on mRNA expression of HIF target genes.

(A) HIF-1 and HIF-2 have unique, as well as common, target genes. HIF-1 specifically regulates glycolytic genes, including lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK), as well as carbonic hydrase-9 (CA IX) whereas HIF-2 exclusively regulates POU transcription factor Oct-4, cyclin D1, and transforming growth factor α (TGF-α). Other hypoxia-inducible genes, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), and EPO are regulated by both HIF-1 and HIF-2. (B, C) 6-week-old BALB/c mice were exposed to 10% O2 (hypoxia) for 3 hours with or without 0.5% isoflurane and compared with controls. Control mice were exposed to air without isoflurane (normoxia). (D) 6-week-old BALB/c mice were exposed to 0.5% or 1.0% isoflurane in air for 3 hours. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). The expression levels of EPO, VEGF, LDHA and GLUT1 were assayed using real-time RT-PCR and normalized to that of 18S and expressed relative to the mean of mice exposed to air without isoflurane (normoxia).

Recently, several reports have shown that isoflurane activates HIF-1 and upregulates HIF target genes [27], [28], [29], [31]. Most of these studies were performed under normoxic conditions. Therefore, we investigated the influence of isoflurane on the expression of HIF target genes in mouse brains under normoxic conditions. We exposed mice to air with 0.5% or 1.0% isoflurane for 3 h and measured the mRNA levels of the HIF target genes, including EPO, VEGF, LDHA, and GLUT1 (Figure 5D). Isoflurane inhalation did not significantly change the expression of the mRNA for any of these HIF target genes.

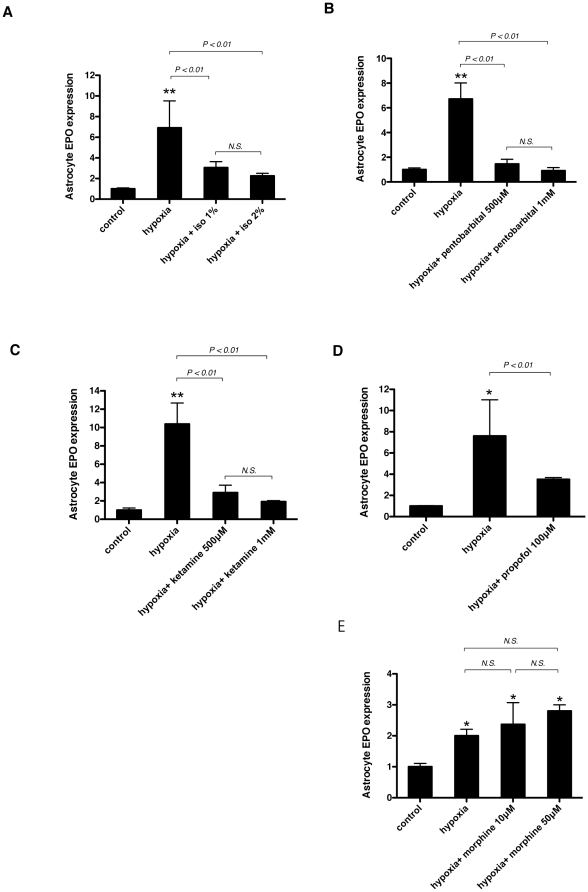

Isoflurane, pentobarbital, ketamine, and propofol suppress, but morphine does not suppress hypoxia-induced up-regulation of EPO mRNA in primary cultured astrocytes

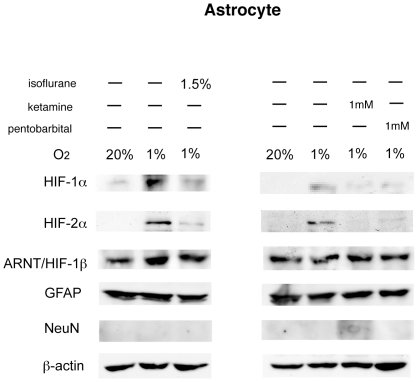

Astrocytes are now supposed to be the major source of EPO in the CNS [6], [7]. To investigate the direct effect of general anesthetics on astrocytes, we performed in vitro experiments. Primary cultured astrocytes were exposed to hypoxia (1% O2) with or without various anesthetics for 4 h. Hypoxic exposure significantly induced EPO mRNA, and isoflurane suppressed its induction (Figure 6A). Not only isoflurane but also other anesthetics, including pentobarbital, ketamine, and propofol, suppressed the induction of EPO mRNA (Figures 6B–D). However, morphine, a commonly used drug during the preoperative period, did not inhibit the upregulation of EPO mRNA in astrocytes (Figure 6E). Next, HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and ARNT protein accumulation were analyzed in whole cell lysates from astrocytes. An immunoblot assay showed distinct HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein accumulation under hypoxic conditions, and the expression was significantly suppressed with isoflurane, ketamine, and pentobarbital (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Effect of various anesthetics on EPO expression in primary cultured astrocytes.

Primary cultured astrocytes were exposed to 1% O2 (hypoxia) in the presence of indicated concentrations of isoflurane (A), pentobarbital (B), ketamine (C), propofol (D) or morphine (E) for 4 hours. In the all experiments, control was exposed to 20% O2. EPO mRNA was assayed with real-time RT-PCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4). The expression levels of EPO were normalized to that of 18S and expressed relative to the mean of control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus control, N.S.; not significant (Mann-Whitney U-test).

Figure 7. Expression analysis of HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and ARNT protein in primary cultured astrocytes by immunoblotting.

Primary cultured astrocytes were incubated under hypoxic (1% O2) conditions with or without 1.5% isoflurane, 1 mM pentobarbital, or 1 mM ketamine for 4 hours. Whole cell lysates were analyzed for HIF-1α, HIF-2α, ARNT, GFAP, NeuN and β-actin protein expression by immunoblot assay. Figures are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Effect of various anesthetics on oxygen consumption in primary cultured astrocytes

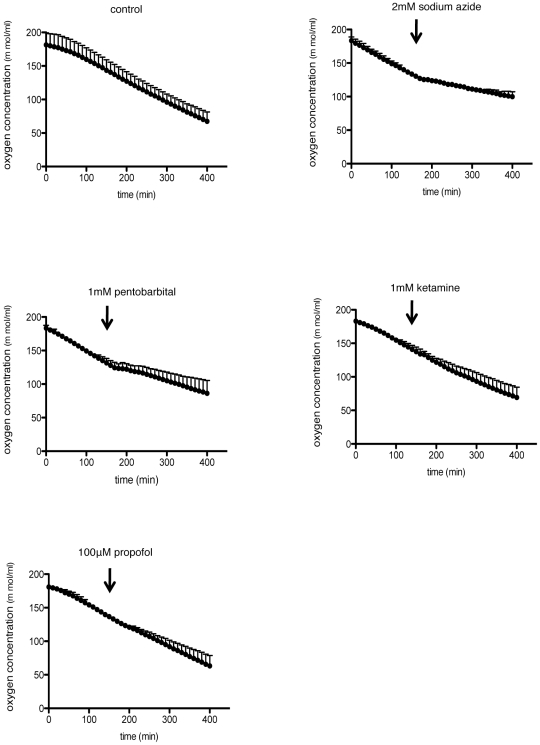

To investigate the precise mechanism of how general anesthetics suppress the induction of EPO under hypoxic conditions, we finally examined the influence of general anesthetics on oxygen consumption in astrocytes. General anesthetics, especially thiopental, are known to decrease metabolism and oxygen consumption of the brain [37]. Therefore, the suppression of oxygen consumption induced by general anesthetics may reduce the level of hypoxia and consequently decrease HIF-α protein accumulation and EPO induction. As indicated in Figure 8, 1 mM pentobarbital as well as sodium azide, a cytochrome oxidase inhibitor, reduced the oxygen consumption; however, 1 mM ketamine and 100 µM propofol did not alter the oxygen consumption significantly. These results suggest that, at least as to ketamine and propofol, the decrease in oxygen consumption was not the cause of the suppression of EPO induction.

Figure 8. Effect of anesthetics on oxygen consumption of primary cultured astrocytes.

Oxygen consumption curves generated using a Clark electrode for primary cultured astrocytes suspensions. Arrows indicate addition of 2 mM sodium azide, 1 mM pentobarbital, 1 mM ketamine or 100 µM propofol. The slope of the curve is a measure of the rate of O2 consumption. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Discussion

EPO is a major hematopoietic growth factor that is mainly produced in the kidney and fetal liver [5]. It is also known to express in CNS tissue [5]. EPO mRNA is constitutively expressed in the cortex and hippocampus of the brain [38]. Various studies have focused on the function of EPO in CNS; for example, mice lacking EPO or EPOR exhibited increased apoptosis in the brain before they died from severe anemia in utero [39], [40], and mice lacking EPOR in the brain suffered from reduced neurogenesis or impaired migration of neurons in a brain stroke model [41]. Thus, EPO is considered to be a neuroprotective factor against hypoxic-ischemic and traumatic injuries and essential for neuronal development [5], [12].

In the present study, we showed that the induction of EPO expression under hypoxic conditions was suppressed by the general anesthetic isoflurane in a concentration- and time-dependent manner in the mouse brain. Other anesthetics, including sevoflurane, halothane, N2O, pentobarbital, ketamine, and propofol, showed a similar effect. As for the mechanism of this suppression, we found that the accumulation of HIF-2α, but not HIF-1α, protein under hypoxic conditions was suppressed with isoflurane in the mouse brain. This finding is consistent with a previous report indicating that EPO is a target gene for HIF-2α, rather than HIF-1α, in CNS [32]. HIF-1α is expressed ubiquitously, but the expression of HIF-2α is tissue-specific [32]. HIF-2α is expressed in astrocytes and endothelial cells in the CNS [32]. Astrocytes are the major source of EPO in the CNS [6], [7], and hypoxia-induced EPO upregulation is dramatically reduced in the astrocyte-specific HIF-2α knockout mouse [38]. In the present study, various anesthetics, including isoflurane, pentobarbital, and ketamine, suppressed the accumulation of HIF-2α protein under hypoxic conditions in cultured astrocytes. Therefore, our results indicated that the hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-2 in astrocytes was inhibited by general anesthetics, which resulted in a significant suppression of EPO production.

Recently, various studies on astrocytes have been performed, and these cells are considered responsible for a wide variety of functions in the CNS, including synaptic transmission and information processing by neural circuit functions [42]. In the present study, we showed that various anesthetics suppressed the accumulation of HIF-2α protein and EPO upregulation under hypoxic conditions in the mouse brain and cultured astrocytes. Considering the fact that the accumulation of HIFα proteins is induced by hypoxia, the suppression of oxygen consumption induced by general anesthetics may reduce the level of hypoxia and consequently decrease HIF-2α protein accumulation. Actually, most of all general anesthetics excluding ketamine and N2O are known to decrease cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen [43]. But the effect of anesthetics on metabolism of astrocytes is not well investigated. In the current study, pentobarbital, well known for suppressing the metabolism of the CNS [37], decreased oxygen consumption of astrocytes. On the other hand, ketamine and propofol did not change oxygen consumption. In addition, we previously reported that hypoxic brain EPO induction was preserved in hypothermic mice, although hypothermia is well known to reduce cerebral oxygen consumption [44]. Therefore, these findings suggest that the suppressive effect of various anesthetics against HIF-2α protein accumulation and EPO induction cannot be explained only by the decrease in oxygen consumption.

The main target of general anesthetics differs with various anesthetics; for example, ketamine and N2O act via N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors [45], [46], whereas the volatile anesthetics, propofol and barbiturates act via γ-aminobenzoic acid-A (GABA-A) receptors [47], [48]. On the other hand, the effect of general anesthetics on glial cells is not well understood, except for the fact that volatile anesthetics inhibit the glutamate uptake of astrocytes [49]. Our finding that various general anesthetics have an EPO-suppressive effect in in vitro experiments suggests that general anesthetics have some common direct effects on astrocytes. This finding is quite surprising considering the diverse action mechanism of general anesthetics. Anesthetics modulate functions of macromolecules, which play an essential role in cellular signal transduction. For example, protein kinase C (PKC) [50], mitogen-activating protein kinases (MAPKs) [51], and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [52] are modulated by anesthetics. PKC, MAPK, and ROS are also identified to affect HIF activity by modulating HIF-α protein translation rate, hydroxylation, and phosphorylation of HIF-α protein [53], [54], [55]. Therefore, general anesthetics may affect astrocytes through modulation of such enzymes and mediators. But most of the studies considering the effect of anesthetics on HIF have focused on HIF-1 under normoxic conditions, and the effect on HIF-2 under hypoxic conditions is not well understood.

Another important finding of the present study is the difference of behavior between HIF-1α and HIF-2α. Namely, HIF-1α was expressed even under normoxic conditions and 3-h hypoxic exposure did not affect HIF-1 protein accumulation distinctively in mice brains. In contrast, HIF-2α was barely expressed under normoxic conditions and clearly increased in response to hypoxic exposure. In in vitro experiments, however, both HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein accumulation were observed under a 1% O2 condition, and various anesthetics significantly suppressed their induction. Although both HIF-1α and HIF-2α are considered to accumulate significantly under hypoxic conditions in in vivo experiments using the mouse brain [56], some reports have shown that HIF-1α was expressed even under normoxic conditions [57], [58]. In most of these previous reports, HIF-1α protein increased in response to hypoxic exposure in the brain, but the extent varied [57], [58], [59]. A possible explanation for the discrepancy is the difference of oxygen concentration. Previous report showed that HIF-1α protein accumulation was observed under 1% O2 condition but not 5% O2 condition in the neuronal cell line SK-N-BE cells [23]. We exposed mice to 10% O2 in our studies, but 10% O2 might not be low enough to induce HIF-1α protein accumulation.

EPO has now been considered to be one of the promising agents for neuroprotection [3], [4], [5]. Actually, in the clinical trials, erythropoietin showed neuroprotective effect against acute stroke [60], hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in newborns [61] and delayed ischemic deficits following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage [62]. In the current study, we showed the induction of EPO mRNA expression under hypoxic conditions was suppressed with isoflurane in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. Other anesthetics including sevoflurane, halothane, N2O, pentobarbital, propofol and ketamine showed the same effect. Most of all anesthetics suppressed EPO mRNA induction with concentrations no more than clinically used, for example, isoflurane, sevoflurane and halothane showed this effect with 0.5%. Therefore, considering the neuroprotective effect of EPO, exposure to anesthetics beyond necessity should be avoided especially in cases hypoxia in brain may happen at greater risk like cardiovascular surgery.

According to the recent reports, anesthetic exposure in neonatal animals leads to neuronal death in certain circumstances [63], [64]. Such neurotoxicity has now been demonstrated for many anesthetics, including isoflurane, ketamine, midazolam, pentobarbital, N2O, and propofol, and a positive correlation may exist between increased levels of anesthesia and increased severity of neuroapoptosis [65], [66]. The precise mechanisms by which injury is invoked are not clear, although an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory input in the CNS during synaptogenesis may contribute to such an effect [65]. On the other hand, EPOR is highly expressed in the developing mouse brain [7], and mice lacking EPO or EPOR experienced increased apoptosis in the brain before they died of severe anemia in the uterus [39], [40]. We did not investigate the effect of general anesthetics on brain EPO under normoxic conditions in neonatal animals. However, considering the pivotal role of EPO in brain development, general anesthetics may cause neuroapoptosis by suppressing EPO production in the brain. Further studies using neonatal animals should be performed.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that isoflurane inhibited hypoxia-induced EPO upregulation in the mouse brain and cultured astrocytes, most likely through suppression of HIF-2 activity. Other general anesthetics showed the same effect. Our findings suggest that general anesthetics have some direct effect on astrocytes and a major impact on the hypoxic response of the CNS.

Methods

Animals

This study (ID: Med Kyo 09504) was approved by the Animal Research Committee of Kyoto University (Kyoto, Japan), and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the institutional and NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. All procedures were performed on BALB/c or C57BL/6N CrSlc mice purchased from Japan SLC Inc., Shizuoka, Japan. Food and water were provided ad libitum, and the mice were maintained under controlled environmental conditions (24°C, 12-h light/dark cycles).

Drugs and chemicals

Isoflurane and pentobarbital were obtained from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan; sevoflurane from Maruishi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan; halothane from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan; and propofol from Astra-Zeneca, London, UK. Morphine and ketamine were purchased from Sankyo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. Nitrous oxide (N2O) (Wakayama Sanso, Wakayama, Japan), oxygen (O2) (Taiyo Nippon Sanso, Tokyo, Japan), and nitrogen (N2) (Taiyo Nippon Sanso) were also used.

Hypoxic treatment

Mice were placed in a polypropylene chamber, and O2 and N2 mixed gas with or without volatile anesthetics, including isoflurane, sevoflurane, and halothane, was delivered to the chamber at a flow rate of 3 l/min using an anesthetic machine (Custom50; Aika, Tokyo, Japan). In the experiment using N2O, O2 and N2O-mixed gas was administered at the same flow rate. Concentrations of O2, carbon dioxide (CO2), N2O, and volatile anesthetics, including isoflurane, sevoflurane, and halothane, were monitored continuously using an infrared analyzer (Capnomac Ultima; Datex-Ohmeda, Helsinki, Finland). Mice were allowed to adjust to the hypoxic environment by gradually decreasing the O2 level from 21% to 10% over 1 h, and they were maintained at 10% O2 for the indicated durations. Treatment with the volatile anesthetics was initiated immediately after the adaptation to hypoxia. In the experiments using pentobarbital, ketamine, and propofol, the drugs were administered intraperitoneally immediately after hypoxic adaptation. The rectal temperature was monitored using an ATB-1100 (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan), and a heat lamp was used to maintain the temperature at 36±1°C. Arterial blood pressure was measured non-invasively using the tail-cuff method immediately after completion of the hypoxic exposure using an MK-2000ST (Muromachi Kikai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). At the end of the experiments, the mice were killed by cervical dislocation. The brains, spinal cords, and kidneys were rapidly removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for subsequent determinations.

Reverse transcription and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

RNA was isolated from the frontal lobe of the brain using the FastPure™ RNA Kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan). First-strand synthesis and real-time RT-PCR were performed using the One Step SYBR™ PrimeScript™ RT-PCR Kit II (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was performed using the Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All PCR primers (Catalog numbers: 18S: QT01036875; EPO: QT00170331; VEGF: QT00160769; GLUT1: QT01044953) except lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). The sequences of the LDHA primers (Takara Bio) are 5′-GGATGAGCTTGCCCTTGTTGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GACCAGCTTGGAGTTCGCAGTTA-3′ (reverse). The fold changes in expression of each target mRNA were calculated relative to 18S rRNA.

ELISA of EPO

Samples were prepared according to the method described previously [67]. Briefly, the entire brain was homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), centrifuged for 10 min at 5,000 g at 4°C, and immediately frozen at −20°C. After two freeze–thaw cycles to break the cell membranes, the brain homogenates were assayed by an ELISA kit (R&D Systems Europe, Abingdon, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The results were expressed as the ratio of the quantity of EPO (in pg) to the quantity of total protein (in mg) in the brain. The total protein concentration was determined by the modified Bradford assay (Nakalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard.

Immunoblot assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared from a whole mouse brain using a nuclear extraction kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). The aliquots (100 µg protein) were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS/PAGE) (7.5% gel) and subjected to an immunoblot assay following a protocol described previously [68]. Primary antibodies raised against HIF-1α (AB 1536; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), HIF-2α (NB100-480; Novus Biologicals, Inc., Littleton, CO), ARNT (HIF-1β) (#611078; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (#3670; Cell Signaling, Stockholm, Sweden), neuronal nuclei (NeuN) (MAP377; Millipore, Billerica, MA), and β-actin (A5316; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) were used at a 1∶1000 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) or donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (GE Healthcare) were also used at a 1∶1000 dilution. The signal was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (GE Healthcare).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed according to the procedure described by Toda et al [69]. Mouse brains were kept at 4°C overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. The brains were then rinsed in PBS, transferred to 70% ethanol, and embedded in paraffin. Ten-micrometer coronal sections were cut and mounted on slides using albumin water. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed using autoclaving. Briefly, a Coplin jar containing glass slides in citrate buffer was covered with a loose fitting cap and heated in a stainless steel pressure cooker for 5 min at 121°C. The pressure cooker was removed from the heat source and cooled by running under cold water with the lid on. The glass slides were rinsed in distilled water. The incubation and washing procedures were carried out at room temperature. After deparaffinization and antigen retrieval by the methods noted above, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 0.3% H2O2 in methyl alcohol for 30 min. The glass slides were washed in PBS (6 times, 5 min each) and mounted with 1% goat normal serum in PBS for 30 min. Subsequently, rabbit polyclonal anti-HIF-1α (AB 1536; R&D Systems) diluted 1∶200 and rabbit polyclonal anti-HIF-2α (NB100-480; Novus Biologicals) diluted 1∶400 were applied overnight at 4°C. They were then incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit serum (second antibody) diluted 1∶300 in PBS for 40 min, followed by washes in PBS (6 times, 5 min each). Avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) (ABC-Elite, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at a dilution of 1∶100 in BSA was applied for 50 min. After washing in PBS (6 times, 5 min each), coloring reaction was performed using diaminobenzidine, and the nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Cell culture

Primary cultures of cerebral cortical astrocytes were prepared from 1- or 2-day-old C57BL/6N CrSlc mice according to the method previously described [70]. Brains of mice were removed under sterile conditions, and the meninges were carefully removed. The tissue was dissociated by passing it through a 320-µm nylon mesh with the aid of a rubber policeman. After washing with Hanks' balanced salt solution containing DNaseI, the cells were suspended and passed through a 100-µm nylon mesh. Next, they were plated on a plastic culture flask (density of 2 brains per flask) in 10-ml tissue culture medium. The tissue culture medium consisted of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin. The cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. The medium was changed after 3 days, then twice weekly. At the first medium change, the flasks were vigorously shaken in order to remove oligodendrocytes and their precursors. All experiments were performed in cells at day 14 in vitro.

Isoflurane exposure

Isoflurane exposure was performed as described previously [71]. Briefly, cell dishes were kept in the airtight chamber housed within a water jacket incubator maintained at 37°C. An in-line calibrated anesthetic agent vaporizer was used to deliver isoflurane to the gas phase of the culture wells. Hypoxic gas (1% O2–5% CO2–94% N2) was administered at a flow rate of 3 l/min, until the appropriate effluent concentration of the anesthetic was achieved. Effluent isoflurane, O2, and CO2 concentrations were continuously monitored via a sampling port connected to an anesthetic agent analyzer (Capnomac Ultima; Datex-Ohmeda, Helsinki, Finland).

Protein extraction

Whole cell lysates were prepared using ice-cold lysis buffer [0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P40 (NP40), 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 2 mM DTT, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and complete protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics)] following a protocol described previously [72]. A total of 100 µg of protein was loaded onto a 7.5% SDS/PAGE gel for immunoblot assay.

Measurement of total cellular O2 consumption

Cells were trypsinized and suspended at 1×107 cells per ml in DMEM with 10% FBS and 25 mM HEPES buffer. For each experiment, equal numbers of cells suspended in 0.4 ml were pipetted into the chamber of an Oxytherm™ electrode unit (Hansatech Instruments, Norfolk, UK), which uses a Clark-type electrode to monitor the dissolved O2 concentration in the sealed chamber over time. The data were exported to a computerized chart recorder (Oxygraph; Hansatech Instruments) that calculated the rate of O2 consumption. The temperature was maintained at 37°C during measurement. The O2 concentration in 0.4 ml of DMEM medium without cells was also measured over time to provide background values. Oxygen consumption experiments were repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed by Mann-Whitney U-test for two group comparisons and by Kruscal Wallis H-test, followed by Mann-Whitney U-test with Bonferroni Correction for multiple group comparisons. Significance was defined as a value of P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Youshi Fujita (Department of Neurology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) for his advice on immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Selim M. Perioperative stroke. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:706–713. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra062668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginsberg MD. Current status of neuroprotection for cerebral ischemia: synoptic overview. Stroke. 2009;40:S111–114. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.528877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrenreich H, Hasselblatt M, Dembowski C, Cepek L, Lewczuk P, et al. Erythropoietin therapy for acute stroke is both safe and beneficial. Mol Med. 2002;8:495–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez PE, Fares RP, Risso JJ, Bonnet C, Bouvard S, et al. Optimal neuroprotection by erythropoietin requires elevated expression of its receptor in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9848–9853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901840106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brines M, Cerami A. Emerging biological roles for erythropoietin in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:484–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masuda S, Okano M, Yamagishi K, Nagao M, Ueda M, et al. A novel site of erythropoietin production. Oxygen-dependent production in cultured rat astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19488–19493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marti HH, Wenger RH, Rivas LA, Straumann U, Digicaylioglu M, et al. Erythropoietin gene expression in human, monkey and murine brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:666–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernaudin M, Marti HH, Roussel S, Divoux D, Nouvelot A, et al. A potential role for erythropoietin in focal permanent cerebral ischemia in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:643–651. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199906000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marti HH. Erythropoietin and the hypoxic brain. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:3233–3242. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruscher K, Freyer D, Karsch M, Isaev N, Megow D, et al. Erythropoietin is a paracrine mediator of ischemic tolerance in the brain: evidence from an in vitro model. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10291–10301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10291.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim I, Kim CH, Yim YS, Ahn YS. Autocrine function of erythropoietin in IGF-1-induced erythropoietin biosynthesis. Neuroreport. 2008;19:1699–1703. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32831743fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noguchi CT, Asavaritikrai P, Teng R, Jia Y. Role of erythropoietin in the brain. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;64:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sirén AL, Knerlich F, Poser W, Gleiter CH, Brück W, et al. Erythropoietin and erythropoietin receptor in human ischemic/hypoxic brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s004010000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamasaki M, Mishima HK, Yamashita H, Kashiwagi K, Murata K, et al. Neuroprotective effects of erythropoietin on glutamate and nitric oxide toxicity in primary cultured retinal ganglion cells. Brain Res. 2005;1050:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen G, Shi J, Hang CH, Xie W, Liu J, et al. Inhibitory effect on cerebral inflammatory agents that accompany traumatic brain injury in a rat model: a potential neuroprotective mechanism of recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO). Neurosci Lett. 2007;425:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockmann C, Fandrey J. Hypoxia-induced erythropoietin production: a paradigm for oxygen-regulated gene expression. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:968–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang GL, Semenza GL. General involvement of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in transcriptional response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4304–4308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirota K. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1, a master transcription factor of cellular hypoxic gene expression. J Anesth. 2002;16:150–159. doi: 10.1007/s005400200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang BH, Rue E, Wang GL, Roe R, Semenza GL. Dimerization, DNA binding, and transactivation properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17771–17778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirota K, Semenza GL. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 by prolyl and asparaginyl hydroxylases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ema M, Taya S, Yokotani N, Sogawa K, Matsuda Y, et al. A novel bHLH-PAS factor with close sequence similarity to hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha regulates the VEGF expression and is potentially involved in lung and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4273–4278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmquist-Mengelbier L, Fredlund E, Löfstedt T, Noguera R, Navarro S, et al. Recruitment of HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha to common target genes is differentially regulated in neuroblastoma: HIF-2alpha promotes an aggressive phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu CJ, Iyer S, Sataur A, Covello KL, Chodosh LA, et al. Differential regulation of the transcriptional activities of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3514–3526. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3514-3526.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rankin EB, Biju MP, Liu Q, Unger TL, Rha J, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 (HIF-2) regulates hepatic erythropoietin in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1068–1077. doi: 10.1172/JCI30117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itoh T, Namba T, Fukuda K, Semenza GL, Hirota K. Reversible inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation by exposure of hypoxic cells to the volatile anesthetic halothane. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:225–229. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li QF, Wang XR, Yang YW, Su DS. Up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha by isoflurane in Hep3B cells. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1211–1219. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li QF, Zhu YS, Jiang H. Isoflurane preconditioning activates HIF-1alpha, iNOS and Erk1/2 and protects against oxygen-glucose deprivation neuronal injury. Brain Res. 2008;1245:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raphael J, Zuo Z, Abedat S, Beeri R, Gozal Y. Isoflurane preconditioning decreases myocardial infarction in rabbits via up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor 1 that is mediated by mammalian target of rapamycin. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:415–425. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318164cab1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arcasoy MO. The non-haematopoietic biological effects of erythropoietin. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:14–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hieber S, Huhn R, Hollmann MW, Weber NC, Preckel B. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and related gene products in anaesthetic-induced preconditioning. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:201–206. doi: 10.1097/eja.0b013e3283212cbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chavez JC, Baranova O, Lin J, Pichiule P. The transcriptional activator hypoxia inducible factor 2 (HIF-2/EPAS-1) regulates the oxygen-dependent expression of erythropoietin in cortical astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9471–9481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2838-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAuliffe JJ, Loepke AW, Miles L, Joseph B, Hughes E, et al. Desflurane, isoflurane, and sevoflurane provide limited neuroprotection against neonatal hypoxia-ischemia in a delayed preconditioning paradigm. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:533–546. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b060d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semenza GL, Nejfelt MK, Chi SM, Antonarakis SE. Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3′ to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5680–5684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu CJ, Sataur A, Wang L, Chen H, Simon MC. The N-terminal transactivation domain confers target gene specificity of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4528–4542. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, et al. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michenfelder JD, Sundt TM., Jr The effect of Pa CO2 on the metabolism of ischemic brain in squirrel monkeys. Anesthesiology. 1973;38:445–453. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weidemann A, Johnson RS. Nonrenal regulation of EPO synthesis. Kidney Int. 2009;75:682–688. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu X, Lin CS, Costantini F, Noguchi CT. The human erythropoietin receptor gene rescues erythropoiesis and developmental defects in the erythropoietin receptor null mouse. Blood. 2001;98:475–477. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu X, Shacka JJ, Eells JB, Suarez-Quian C, Przygodzki RM, et al. Erythropoietin receptor signalling is required for normal brain development. Development. 2002;129:505–516. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsai PT, Ohab JJ, Kertesz N, Groszer M, Matter C, et al. A critical role of erythropoietin receptor in neurogenesis and post-stroke recovery. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1269–1274. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4480-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:7–35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fink BR, Haschke RH. Anesthetic effects on cerebral metabolism. Anesthesiology. 1973;39:199–215. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197308000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka T, Wakamatsu T, Daijo H, Oda S, Kai S, et al. Persisting mild hypothermia suppresses hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha protein synthesis and hypoxia-inducible factor-1-mediated gene expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R661–671. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00732.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kress HG. [Mechanisms of action of ketamine]. Anaesthesist. 1997;46(Suppl 1):S8–19. doi: 10.1007/pl00002469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato Y, Kobayashi E, Murayama T, Mishina M, Seo N. Effect of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor epsilon1 subunit gene disruption of the action of general anesthetic drugs in mice. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:557–561. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200503000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of general anaesthesia. Nature. 1994;367:607–614. doi: 10.1038/367607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davies PA, Hanna MC, Hales TG, Kirkness EF. Insensitivity to anaesthetic agents conferred by a class of GABA(A) receptor subunit. Nature. 1997;385:820–823. doi: 10.1038/385820a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyazaki H, Nakamura Y, Arai T, Kataoka K. Increase of glutamate uptake in astrocytes: a possible mechanism of action of volatile anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:1359–1366; discussion 1358A. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199706000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hemmings HJ. General anesthetic effects on protein kinase C. Toxicol Lett. 1998;100–101:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Itoh T, Hirota K, Hisano T, Namba T, Fukuda K. The volatile anesthetics halothane and isoflurane differentially modulate proinflammatory cytokine-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Anesth. 2004;18:203–209. doi: 10.1007/s00540-004-0237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kevin LG, Novalija E, Stowe DF. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of cardiac injury and protection: the relevance to anesthesia practice. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1275–1287. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180999.81013.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor CT. Mitochondria and cellular oxygen sensing in the HIF pathway. Biochem J. 2008;409:19–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hui AS, Bauer AL, Striet JB, Schnell PO, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. Calcium signaling stimulates translation of HIF-alpha during hypoxia. FASEB J. 2006;20:466–475. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5086com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richard DE, Berra E, Gothié E, Roux D, Pouysségur J. p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases phosphorylate hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and enhance the transcriptional activity of HIF-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32631–32637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ke Q, Costa M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1469–1480. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stroka DM, Burkhardt T, Desbaillets I, Wenger RH, Neil DA, et al. HIF-1 is expressed in normoxic tissue and displays an organ-specific regulation under systemic hypoxia. FASEB J. 2001;15:2445–2453. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0125com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gu GJ, Li YP, Peng ZY, Xu JJ, Kang ZM, et al. Mechanism of ischemic tolerance induced by hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning involves upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and erythropoietin in rats. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1185–1191. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00323.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeo EJ, Cho YS, Kim MS, Park JW. Contribution of HIF-1alpha or HIF-2alpha to erythropoietin expression: in vivo evidence based on chromatin immunoprecipitation. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:11–17. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ntaios G, Savopoulos C, Chatzinikolaou A, Hatzitolios A. The neuroprotective role of erythropoietin in the management of acute ischaemic stroke: from bench to bedside. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118:362–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu C, Kang W, Xu F, Cheng X, Zhang Z, et al. Erythropoietin improved neurologic outcomes in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e218–226. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tseng MY, Hutchinson PJ, Richards HK, Czosnyka M, Pickard JD, et al. Acute systemic erythropoietin therapy to reduce delayed ischemic deficits following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a Phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:171–180. doi: 10.3171/2009.3.JNS081332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rappaport B, Mellon RD, Simone A, Woodcock J. Defining safe use of anesthesia in children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1387–1390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1102155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mellon RD, Simone AF, Rappaport BA. Use of anesthetic agents in neonates and young children. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:509–520. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000255729.96438.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel P, Sun L. Update on neonatal anesthetic neurotoxicity: insight into molecular mechanisms and relevance to humans. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:703–708. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c42a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cattano D, Williamson P, Fukui K, Avidan M, Evers A, et al. Potential of xenon to induce or to protect against neuroapoptosis in the developing mouse brain. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55:429–436. doi: 10.1007/BF03016309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El Hasnaoui-Saadani R, Pichon A, Marchant D, Olivier P, Launay T, et al. Cerebral adaptations to chronic anemia in a model of erythropoietin-deficient mice exposed to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R801–811. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00119.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nishi K, Oda T, Takabuchi S, Oda S, Fukuda K, et al. LPS induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation in macrophage-differentiated cells in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:983–995. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Toda Y, Kono K, Abiru H, Kokuryo K, Endo M, et al. Application of tyramide signal amplification system to immunohistochemistry: a potent method to localize antigens that are not detectable by ordinary method. Pathol Int. 1999;49:479–483. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Asou H, Hirano S, Kohsaka S. Changes in ganglioside composition and morphological features during the development of cultured astrocytes from rat brain. Neurosci Res. 1989;6:369–375. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(89)90030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Calvert JW, Cahill J, Yamaguchi-Okada M, Zhang JH. Oxygen treatment after experimental hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal rats alters the expression of HIF-1alpha and its downstream target genes. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:853–865. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00268.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takabuchi S, Hirota K, Nishi K, Oda S, Oda T, et al. The intravenous anesthetic propofol inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activity in an oxygen tension-dependent manner. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]