Abstract

Although improvements in materials engineering have greatly reduced fracture rates in ceramic femoral heads, concerns still exist for liners. Ceramics are vulnerable fracture due to impact, and from stress concentrations (point and line loading) such as those associated with impingement-subluxation. Thus, ceramic cup fracture propensity is presumably very sensitive to surgical cup positioning. A novel fracture mechanics finite element formulation was developed to identify cup orientations most susceptible to liner fracture propagation, for several impingement-prone patient maneuvers. Other factors being equal, increased cup inclination and increased anteversion were found to elevate fracture risk. Squatting, stooping and leaning shoe-tie maneuvers were associated with highest fracture risk. These results suggest that fracture risk can be reduced by surgeons’ decreasing cup abduction and by patients’ avoiding of specific activities.

Keywords: fracture mechanics, total hip arthroplasty, ceramic-on-ceramic, impingement, finite element analysis

INTRODUCTION

Alumina ceramics for total hip arthroplasty (THA) were introduced nearly four decades ago, to address concerns over polyethylene-particle-induced osteolysis and to improve long-term results in younger and more active THA patients [1, 2]. Ceramic-on-ceramic (CoC) bearings offer several advantages over contemporary metal-on-polyethylene or metal-on-metal constructs. However, due to the brittle nature of ceramic materials, concerns persist regarding implant failure due to catastrophic fracture.

Microscopic-level imperfections in a brittle material act as stress risers when load is applied. The Stress Intensity Factor (K) is a measure of the severity to which otherwise-present mechanical stress is amplified by the presence of a flaw. The magnitude of K depends on several factors, such as macroscopic geometry of the part, the geometry of the flaw, and the magnitude of the applied stress (Eqn 1, see [3]). Commonly, the flaw is a (propagating) brittle crack, for which the flaw-magnified stress tensor, σij, takes the form:

| (Eqn. 1) |

Here, σ∞ is the far-field stress (distant from the crack tip), a is the crack length, r is the distance from the crack tip, KI is the mode-I (tensile) stress intensity factor and f is a function of crack orientation angle θ. Subscripts i and j define the directional components of the stress tensor. Similar stress-magnification relationships exist for shearing mode fracture (KII) and for out-of-plane shearing (tearing) mode fracture (KIII). For complex loading situations, all three modes can contribute to material failure, a circumstance known as mixed-mode fracture.

Fracture of brittle materials can be described as encompassing two phases: subcritical crack growth, and catastrophic fracture [4]. Small material flaws and imperfections, which are ubiquitous in sintered materials [4, 5], propagate subcritically if K exceeds a limiting threshold factor, K0. When the value of K exceeds a critical stress intensity KIC (for tensile mode failure), uncontrolled crack growth (catastrophic fracture) occurs.

Fracture of the femoral head is a well recognized problem historically [4, 6]. Impact seating of the ceramic head onto the metal trunnion (“Morse” taper) of the femoral neck creates regions of high circumferential hoop stress, which sometimes tended to cause crack propagation and ultimately critical fracture. However, extensive investigation into the design of this ceramic-metal interface, by experimental [6–8], analytical [9] and finite element (FE) [10, 11] techniques, identified critical design factors which increased fracture propensity. This led to optimization of parameters such as component size, shape, taper angle, surface roughness and neck length. These design modifications, along with improvements in material engineering and in proof testing, decreased femoral head fracture rates from 13% for first-generation alumina heads [12], to rates in the range of 0.004% [13] for contemporary heads. In contrast, for ceramic liners systematic analysis regarding fracture risk mitigation has been much more limited. Recently reported fracture rates for contemporary liners are in the range of a few percent to a few tenths of a percent (3.5% [14], 1.12% [15], 0.22% [16]), values which greatly exceed the few thousandths of a percent for (alumina) head fracture. Furthermore, it has been suggested that due to diagnostic difficulties, ceramic liner fracture is likely an “underestimated” occurrence. [16].

Various predisposing factors for ceramic liner fracture have been cited, including microseparation [17], trauma [18] and obesity [19]. But, fractures apparently due to component impingement far outnumber those from all other causes [14–16, 20, 21]. Given the brittle nature of ceramic materials, the high stresses which occur during impingement presumably give rise to elevated fracture risk. Optimal component positioning is thus arguably even more important for CoC than for other bearing alternatives [22]. At present, however, the strength of influence of the various surgical positioning factors as regards ceramic liner fracture propensity is purely conjectural. To address the need for objective information about the relationship between ceramic fracture risk and surgical cup positioning for different impingement challenges, a purpose-formatted linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM) FE model has been developed. This model was used to investigate which cup orientations and which impingement-prone patient motion patterns have highest propensity for brittle fracture propagation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To compute the stress intensity factor of a cracked body, accurate determination of the stresses near the crack tip is required. However, because of the / factor in Eqn. 1, the stress field becomes singular (i.e., approaches infinity) near the crack tip. Specialty elements and meshes are required to capture this singularity.

Geometric data for THA ceramic liner representation were extracted from manufacturer-provided surface geometry (IGES) files, and were imported into an FE mesh pre-processor (TrueGrid v. 3.2, XYZ Scientific Applications, Inc., Livermore, CA). Small cracks arising from material flaws were then posited to exist at systematically varied locations. Crack modeling began by first meshing the liner with 20-node hexahedral elements (Fig. 1). Zoning of the crack consisted of 10 rows through the thickness of the liner of 32 elements each, forming the crack tip. One face of each of the 32 elements forming each row of the crack tip was condensed to a single line, in effect collapsing a single edge of each crack element, allowing these particular elements to take on the shape of a wedge, while maintaining the nodal and element connectivities of hexahedral elements. Based on mesh sensitivity studies, five concentric rings of regular (i.e., non-collapsed) hexahedral elements served as rosettes, from which K values could be calculated using the J-integral [23] method (Fig. 2). Sliding interfaces were defined for the entire crack tip region, as well as for the crack faces per se. These sliding interfaces precluded merger (i.e., computational equivalencing) of nodes, thus retaining the “wedge” form of 20-node collapsed hexahedral elements at the crack tip. The remaining geometry of the ceramic liner was meshed conventionally, and was interfaced with the crack-containing sector. The variables used in the meshing of the crack were entirely parameterized, allowing for complete control and rapid remeshing, to vary crack properties such as crack shape and crack location (e.g. proximity to the liner’s articular surface). All elements of the specified crack tip were then converted into collapsed 20-noded quarter-point elements [24] using purpose-written code (Mathcad v 14.1, Parametric Technology Corporation, Needham, MA), which enabled analysis of the (singular) local stress field.

Fig. 1.

Meshing of a cracked ceramic liner. (a) Demonstrating the cracked sector of the liner. Crack tip (b) is zoned with specialty wedged-shaped fracture elements.

Fig 2.

(a) Undeformed and (b) deformed (scaled by 2000x) local mesh (shown for the inner four layers of element rosettes), demonstrating crack opening during fracture simulation.

Otherwise-present stresses associated with THA impingement were determined from a previously reported dynamic FE model of THA impingement [25], which had been cadaverically validated. That FE model (Fig. 3) consisted of THA hardware (28-mm femoral head, 28mm/46mm liner and 52mm shell outer diameter), bony anatomy and hip capsule. Appropriate mesh resolutions for the THA components had been ascertained from prior convergence studies of contact pressure during impingement. For the bearing, the components were modeled as linearly elastic third-generation alumina (elastic modulus = 380 GPa, Poisson’s ratio = 0.23, density = 3.98gm/cm3), with radial clearance of 0.034 mm and friction coefficient of 0.04 [26]. The hip capsule was represented with a fiber-dominated anisotropic hyperelastic material constitutive model, also as described [25]. Frictional interactions maintained the liner within the acetabular backing. For the present crack analyses, 54 separate FE models were generated to study effects of surgical cup positioning, by varying cup inclination (15° to 65°, in 2.5° increments) and/or cup anteversion (10° retroversion to 40° anteversion, in 10° increments). In addition, seven distinct impingement-prone challenge maneuvers were considered [27]: sit-to-stand from a normal chair height (SSN), sit-to-stand from a low chair (SSL), stooping, squatting, leaning shoe-tie, rolling over in bed, and seated leg-crossing (SXLG).

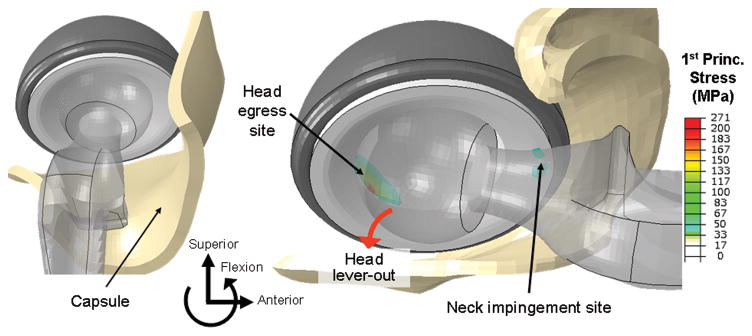

Fig. 3.

THA impingement global FE model. Challenge motions began in full extension (left), and progressed through the prescribed hip angulation sequence, resulting in impingement (right).

The computational solutions for each of these impingement-prone maneuvers were driven by an input sequence of prescribed incremental rotations of the femoral head, along with corresponding modulation of the hip joint contact forces. Dynamic analyses for the global impingement-subluxation models were executed using Abaqus/Explicit (v. 6.9, Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp., Providence, RI). Impingement during the challenge maneuvers involved two separate sites of stress concentration (Fig. 3): one at the contact site between the femoral neck and liner, and the other on the posterior region of the cup rim, associated with (edge loading) line contact during femoral head subluxation (egress) from the cup. These impingement-induced stresses, which corresponded to the σ∞ parameter in Eqn. 1, were stored for later usage to drive the quasi-static ceramic fracture submodel analyses.

Following the global models of dynamic impingement-subluxation, two separate quasi-static FE series were used to assess fracture propensity. These simulations were run using Abaqus’ submodel abstraction capability, which allowed for nodal displacements output from the Abaqus/Explicit global solution (i.e., the non-cracked whole-joint impingement model) to be used as boundary conditions to drive the (crack-zoned) submodel, which was run using Abaqus/Standard. The first series, used to investigate vulnerability to subcritical crack growth, involved situations where respective regions of the ceramic liner were challenged by the presence of a small (rosette-length-scale) surface crack, as a result of which the local stresses approached or in some instances exceeded KIO. For that series, the sit-to-stand dislocation sequence was utilized, with a neutrally-oriented cup (35° inclination, 20° anteversion). Twelve separate fracture FE submodels for this cup orientation were created, with an otherwise similar surface crack alternatively postulated to exist at one of twelve different near-equatorial stations, varied circumferentially around the cup at 30° increments. A second (larger) crack computation series focused on surgical cup orientation and on differing challenge maneuvers as influences upon catastrophic fracture risk. For that purpose, a fractured liner in which a larger crack (presumably previously stably propagated) was posited to exist at the egress region, was zoned for each permutation of cup orientation and of challenge maneuver (115 submodels total). Again following an LEFM paradigm [23], mixed-mode stress intensity factors (KI, KII, KIII) were determined for each submodel by J-integral calculation, using a weighted average of the innermost five element rosette rings. Temporal-spatial maximum values of K were determined for each fracture submodel during each challenge maneuver. Each global impingement-subluxation model required approximately 120 processor-hours to compute on a dual quad-core Intel® Xeon platform configured with 24 GB of RAM, running under a 64-bit Linux operating system. The subsequent LEFM submodels (for both the subcritical crack growth series and the catastrophic fracture series) each required approximately one hour of processor time.

RESULTS

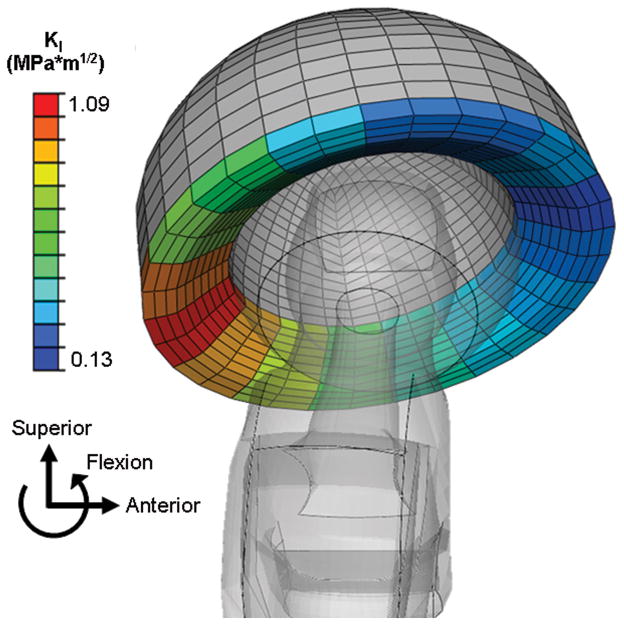

In the first series (alternative subcritical crack locations), computed maximum stress intensity values corresponding to an otherwise-similar small surface crack demonstrated a strong dependency on posited crack location (Fig. 4). The posterior region, associated with head egress during subluxation, had the highest values of KI. The peak KI value (1.09 MPa m1/2) exceeded KI0 for alumina (1.0 MPa m1/2, [4]), indicating a high propensity for subcritical crack propagation at this site.

Fig. 4.

Spatial distribution of subcritical-flaw propagation propensity was quantified by assessing regions of the liner where the computed KI value approached or exceeded KI0.

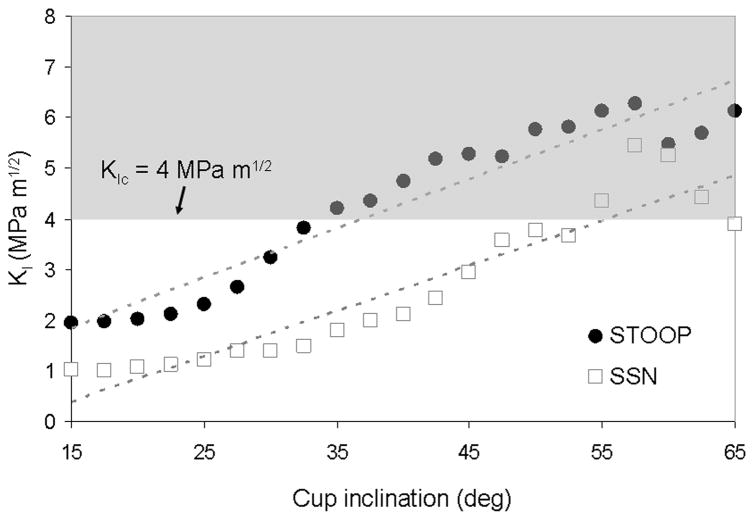

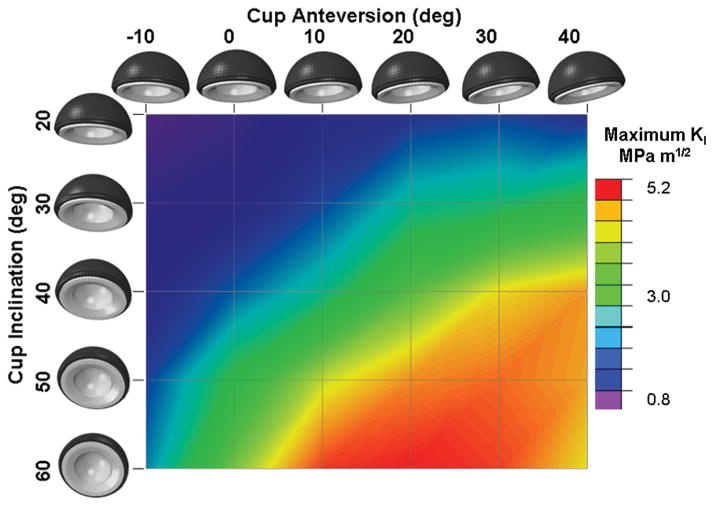

For the catastrophic crack propagation series, computed values of K were strongly influenced by surgical cup orientation. For both the sit-to-stand and stoop challenges, K increased monotonically with increased cup inclination (Fig. 5). For the sit-to-stand motion, except for the most extreme cup orientations (those where impingement either did not occur or was only marginal), KIc for alumina (4.0 MPa m1/2) was not exceeded. However, the stress intensity values that developed during the stoop maneuver were consistently higher than those for the sit-to-stand maneuver, for all cup orientations. The computed values of KI exceeded KIc for more than half of orientations for the stoop challenge maneuver. In addition to increased cup tilt, increased cup anteversion also caused elevated values of K (Fig. 6). There was no clearly higher preferential sensitivity to cup inclination versus to cup anteversion, or vice versa. That is, a given incremental increase in cup inclination increased computed values of KI approximately comparably to what occurred for the same incremental increase in cup anteversion.

Fig. 5.

Dependency of KI on cup inclination angle for both sit-to-stand from a normal chair height (SSN) and for stooping, for a 10° anteverted cup.

Fig. 6.

Computed values of temporal-spatial maximum KI for the stoop challenge, demonstrating fracture propensity sensitivity to both cup inclination and anteversion.

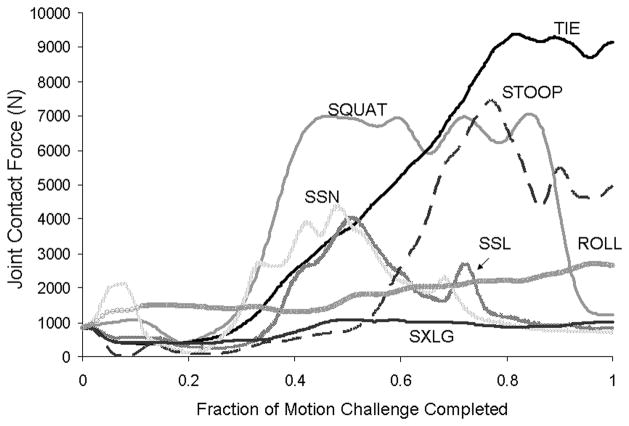

Mixed-mode stress intensity factors for a neutrally oriented (40° inclination, 10° anteversion) cup varied dramatically across the different challenge maneuvers (Fig. 7). The computed values of KI for three of the maneuvers – stooping, squatting and shoe-tying – exceeded KIC. Trends for shear (KII) and tearing (KIII) modes generally followed those for KI, except for shoe-tie.

Fig. 7.

Stress intensity factors for seven impingement-prone motion challenge maneuvers. Three of these maneuvers developed KIvalues in excess of alumina’s KIC (4 MPa m1/2)

DISCUSSION

While liner fracture is a well-recognized risk for ceramic THA bearing couples, the causative factors clinically are still largely speculative. In contrast to the situation for femoral head fracture (where a specific mechanism of fracture stimulated extensive engineering investigation led to major improvements in design and in turn to substantial reduction of fracture rates), the situation for liner fracture is more complicated. Much remains to be discerned. The rationale for the present investigation – to the authors’ knowledge the first formal LEFM analysis of ceramic liner fractures – was to lay groundwork to understand which specific factors (patient and surgical) influence fracture propensity during impingement-subluxation. Parametric model variations addressed (1) the extent to which ceramic liners demonstrate sensitivity to component malpositioning, and (2) which specific challenge maneuvers present the greatest fracture risk, other factors being equal.

Fracture risk during impingement-subluxation was found to be highly site-specific. Owing to the greatly higher tensile stress at the (edge-loading) egress site compared to that from neck-on-liner impingement (Fig. 3), fracture propensity from sub-critical flaw propagation was substantially greater at the egress site (Fig. 4). This sudden catastrophic fracture paradigm [4, 18] differs from that of repetitive impingement leading to progressive chipping of the ceramic liner. Modeling impingement-site chipping is an inviting topic for further analysis.

Risk of catastrophic fracture was computed to be very sensitive to cup orientation. Higher cup inclination and core cup anteversion angles gave rise to the higher values of K if/when subluxation-associated edge loading occurred, similar to the reported dependency of edge-loading bearing surface contact stress on implant orientation [25]. While to the authors’ knowledge a formal association between cup inclination and liner fracture incidence has not (yet) been identified clinically, the present work corroborates the association which has been identified between cup anteversion and fracture risk [14].

Interestingly, even for cup orientations where impingement did not occur (e.g. 65° inclination, 10° anteversion), the egress site fracture risk was significantly higher than for some cup orientations (e.g. 30° inclination, 10° anteversion) where impingement initiated early in the motion sequence. While impingement clearly can play a role in ceramic liner fractures [14–16, 20, 21], this suggests that it is not an absolute requisite. Toward reducing the incidence of impingement-associated liner chipping or fracture, many contemporary designs use a recessed ceramic liner, to ensure that any neck impingement that might occur involves the backing rather than the liner. The present data suggest, however, that this strategy may do little to avoid brittle fractures originating at the opposite (egress) side of the cup.

Besides simply whether or not impingement occurs, the present results show that the “quality” of impingement-subluxation also greatly influences ceramic failure propensity. Hip joint contact forces from inverse dynamics optimization [27] (Fig. 8) involve highest joint loads for the same three challenge maneuvers as those here computed to pose the highest fracture risk. Stooping and leaning (as occur when tying shoes) involve a large offset of the upper-body center of gravity relative to the hip joint center, thus leading to high hip joint reaction forces. Stooping and leaning, along with Asian-style squatting, also result in those peak joint loads being experienced at high flexion (i.e., when impingement and therefore edge loading is most likely to occur), suggesting that the greatest risk of ceramic fracture occurs when high joint contact forces exist under conditions of impingement. Flexion-dominated maneuvers and postures, again especially Asian-style squatting, have been clinically linked to liner fracture [14, 21]. While the effect(s) of loading variations on ceramic fracture have not been experimentally investigated, Maher et al. [28] identified a threshold joint load of 12 kN as being sufficient to cause liner fracture for simulated impingement impact conditions. While not quite exceeding that threshold, the presently computed contact forces for the three highest-risk maneuvers certainly approached that level. A condition of excess body weight would plausibly push joint contact forces even higher, perhaps explaining the increased incidence of ceramic liner fracture in the obese [19].

Fig. 8.

Joint contact force for the seven motion challenges. The three maneuvers at highest risk of fracture (shoe-tie, squat and stoop) were those involving highest joint contact forces.

Although the present LEFM computational formulation represents a substantial step forward in quantitative analysis of fracture in ceramic hip bearings, this study has several simplifications and limitations. First, while the spatial location of the initial “flaw” in the subcritical fracture series was posited at various positions circumferentially around the liner, the flaw in all instances was assumed to be located on the bearing surface of the liner. Whether sub-surface flaws and/or deep flaws would exhibit similar location-sensitivity circumferentially as do surface flaws is an open question. However, high local stress concentrations at the bearing surface [25] are associated with repetitive microtrauma (i.e. microseparation) [15], so surface cracks are especially of interest. Second, while seven distinct impingement-prone challenge maneuvers were investigated, in the interest of computational economy, the vast majority of computational analysis assessing the role of cup orientation on fracture focused on only two of these: sit-to-stand and stooping. The effect of cup orientation upon fracture propensity for other challenges (such as seated leg-crossing) is also an open question, and an inviting topic for additional investigation. Third, the particular shape of the crack used in this analysis undoubtedly would have affected the K magnitudes computed. Analysis of crack propagation in FE models, while well grounded theoretically and while being relatively straightforward to implement in 2D, poses major challenges in 3D. Recent advances in computational analysis, such as the eXtended Finite Element Method (XFEM), hold promise to further facilitate the investigation of ceramic crack propagation in THA bearings. Finally, given the normally highly comminuted nature of ceramic liner fracture, accurate post-facto identification of the initial fracture location is probably impossible, and therefore direct clinical correlation with the fractures modeled in the present study are not available. Clinical collaboration, ideally, would strengthen the utility of the present study, but we note that the fracture paradigm modeled here – impingement leading to subluxation, edge loading and eventually to fracture at the liner egress-site – has been proposed by multiple authors [14–16] following examination of explanted fractured ceramic liners. One very inviting topic for further study is to directly replicate such cracks in a bench physical model, which would provide direct physical corroboration not feasible post facto clinically.

While fracture rates for ceramic components have dramatically improved, such fractures as do occur are devastating to the patient. Ceramic failures always require revision surgery, which is often complicated by the need to revise all components of the primary construct. When revision is delayed, or if debridement of fragment particulates is incomplete, severe third body wear and/or destruction to bone and surrounding soft tissue often occurs, leading to early failure of the revision [18, 22, 29, 30]. The work reported here introduces a novel computational framework within which systematic analysis of ceramic liner fracture can be conducted. Specifically, egress site (edge or near-edge) loading arising from neck-on-cup impingement to was identified as leading to elevated fracture propensity, a mechanism which is well-corroborated clinically [14–16]. The flexibility of the current formulation allows for other potential fracture mechanisms to be similarly systematically explored. Fracture risk was found to be highly site-specific, highly sensitive to component positioning, and highly sensitive to specific challenge maneuvers.

Acknowledgments

Financial assistance was provided by the NIH (AR46601 and AR53553) and by the Veterans Administration. We appreciate the assistance of Drs. John Yack and Lu Kang in collecting data for the squatting fracture challenge and of Dr. Sharif Rahman for technical assistance regarding LEFM model development.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boutin P. Arthroplastie totale de hanche par prothese en alumine frittee. Rev Chir Orthop. 1972;58:229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sedel L. Evolution of alumina-on-alumina implants: A review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(379):48. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200010000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irwin GR. Analysis of stresses and strains near the end of a crack traversing a plate. J Appl Mech. 1957;24:361. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willmann G. Ceramic femoral heads for total hip arthroplasty. Advanced Engineering Materials. 2000;2:114. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hannouche D, Hamadouche M, Nizard R, Bizot P, Meunier A, Sedel L. Ceramics in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(430):62. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000149996.91974.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heimke G. The safety of ceramic balls on metal stems in hip arthroplasty. Adv Mater. 2004;6:165. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrisano AO, Dragoni E, Strozzi A. Axisymmetric mechanical analysis of ceramic heads for total hip replacement. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 1990;204:157. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1990_204_250_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorre E, Richter HG, Willmann G. Fracture load of ceramic ball heads of hip joint prostheses. Biomed Tech (Berl) 1991;36:305. doi: 10.1515/bmte.1991.36.12.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson I, Bowden M, Wyatt T. Stress analysis of hemispherical ceramic hip prosthesis bearings. Med Eng Phys. 2005;27:115. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisse B, Zahner M, Weber W, Rieger W. Improvement of the reliability of ceramic hip joint implants. J Biomech. 2003;36:1633. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drouin J, Cales B, Chevalier J, Fantozzi G. Fatigue behavior of zirconia hip joint heads: Experimental results and finite element analysis. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 1997;34:149. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199702)34:2<149::aid-jbm2>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knahr K, Böhler M, Frank P, Plenk H, Salzer M. Survival analysis of an uncemented ceramic acetabular component in total hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1987;106:297. doi: 10.1007/BF00454337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willmann G. Ceramic femoral head retrieval data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(379):22. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha YC, Kim SY, Kim HJ, Yoo JJ, Koo KH. Ceramic liner fracture after cementless alumina-on-alumina total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;458:106. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180303e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park YS, Hwang SK, Choy WS, Kim YS, Moon YW, Lim SJ. Ceramic failure after total hip arthroplasty with an alumina-on-alumina bearing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:780. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toni A, Traina F, Stea S, Sudanese A, Visentin M, Bordini B, Squarzoni S. Early diagnosis of ceramic liner fracture. guidelines based on a twelve-year clinical experience. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88 (Suppl 4):55. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sariali E, Stewart T, Mamoudy P, Jin Z, Fisher J. Undetected fracture of an alumina ceramic on ceramic hip prosthesis. J Arthroplasty. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hannouche D, Nich C, Bizot P, Meunier A, Nizard R, Sedel L. Fractures of ceramic bearings: History and present status. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):19. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096806.78689.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poggie RA, Turgeon TR, Coutts RD. Failure analysis of a ceramic bearing acetabular component. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:367. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa M, Sudo A, Hirata H, Uchida A. Ceramic acetabular liner fracture in total hip arthroplasty with a ceramic sandwich cup. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:658. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min BW, Song KS, Kang CH, Bae KC, Won YY, Lee KY. Delayed fracture of a ceramic insert with modern ceramic total hip replacement. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:136. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrack RL, Burak C, Skinner HB. Concerns about ceramics in THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(429):73. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150132.11142.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rice J. A path independent integral and the approximate analysis of strain concentration by notches and cracks. Journal of applied mechanics. 1968;35:379. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barsoum RS. On the use of isoparametric finite elements in linear fracture mechanics. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 1976;10:25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elkins JM, O’Brian MK, Stroud NJ, Pedersen DR, Callaghan JJ, Brown TD. Hard-on-hard total hip impingement causes extreme contact stress concentrations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1632-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brockett C, Williams S, Jin Z, Isaac G, Fisher J. Friction of total hip replacements with different bearings and loading conditions. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2007;81:508. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nadzadi ME, Pedersen DR, Yack HJ, Callaghan JJ, Brown TD. Kinematics, kinetics, and finite element analysis of commonplace maneuvers at risk for total hip dislocation. J Biomech. 2003;36:577. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maher SA, Lipman JD, Curley LJ, Gilchrist M, Wright TM. Mechanical performance of ceramic acetabular liners under impact conditions. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:936. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bierbaum BE, Nairus J, Kuesis D, Morrison JC, Ward D. Ceramic-on-ceramic bearings in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(405):158. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200212000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diwanji SR, Seon JK, Song EK, Yoon TR. Fracture of the ABC ceramic liner: A report of three cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:242. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180dc8c35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]