Abstract

Anopheles punctulatus sibling species (An. punctulatus s.s., Anopheles koliensis, and Anopheles farauti species complex [eight cryptic species]) are principal vectors of malaria and filariasis in the Southwest Pacific. Given significant effort to reduce malaria and filariasis transmission through insecticide-treated net distribution in the region, effective strategies to monitor evolution of insecticide resistance among An. punctulatus sibling species is essential. Mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) gene have been associated with knock-down resistance (kdr) to pyrethroids and DDT in malarious regions. By examining VGSC sequence polymorphism we developed a multiplex assay to differentiate wild-type versus kdr alleles and query intron-based polymorphisms that enable simultaneous species identification. A survey including mosquitoes from seven Papua New Guinea Provinces detected no kdr alleles in any An. punctulatus species. Absence of VGSC sequence introgression between species and evidence of geographic separation within species suggests that kdr must be monitored in each An. punctulatus species independently.

Introduction

Malaria vectors in the Southwest Pacific region belong to the Anopheles punctulatus group. The species group range extends from Moluccas to Vanuatu, including New Guinea and islands of the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, and northern Australia.1 Thirteen sibling species (An. punctulatus sensu stricto [s.s.], An. species near punctulatus, morphologically indistinguishable Anopheles farauti 1–8 [Farauti complex; former An. farauti 1, 2, 3, and 7 now An. farauti s.s., Anopheles hinesorum, Anopheles torresiensis, and Anopheles irenicus, respectively], Anopheles koliensis, Anopheles clowi, and Anopheles renellensis)1–5 are known to comprise the species group. Blood feeding behaviors and breeding habitats of the Punctulatus group members have been characterized as unspecialized.6 Distribution of individual sibling species is heterogeneous, displaying unique and occasional overlapping patterns of dispersal.6 In Papua New Guinea (PNG), studies have specifically implicated An. farauti s.s., An. hinesorum, An. farauti 4, An. koliensis, and An. punctulatus s.s. as the primary vectors of malaria and filariasis.7–12 As evidence accumulates to verify the reproductive independence of these sibling species, it becomes increasingly important to collect evidence regarding their species-specific susceptibility to vector control strategies and competence as malaria vectors.

The importance of malaria transmission by An. punctulatus group mosquitoes was first recognized by Heydon and others in the 1920s.13,14 Despite establishing this connection over 90 years ago, mosquito and therefore malaria control in New Guinea has been inconsistently supported and pursued. As malaria casualties during WWII consistently outnumbered those from combat, military activities in New Guinea prompted intense United States and Australian interest in malaria control from 1942 to 1945.15–17 During this time troop protection included military discipline, efforts of malaria control and survey units beginning in 1943, atabrine prophylaxis and treatment of closed environments with “bug bomb” (pyrethrum).15–17 Perhaps the most effective means for controlling mosquito populations, DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane), was not available to troops in the Southwest Pacific area until late 1944, when military operations in New Guinea were drawing to a close.

DDT has been of greatest relevance to mosquito population management in New Guinea because it changed World Health Organization (WHO) strategies from malaria control to eradication.18,19 During the 1940–50s DDT mixed in oil-based solvents and sprayed on larval breeding sites showed short-term effectiveness against malaria transmission.20–22 However, DDT indoor residual spraying (IRS) was associated with reduced exposure to An. punctulatus group mosquitoes in New Guinea23–26 and remained active for 6 months after application. These combined features suggested that DDT IRS would enable deployment of time-efficient “attack” phase strategies by limited numbers of disease control specialists and unskilled workers.19,25,27 These findings encouraged DDT IRS activities from the late 1950s to 1970s,27–30 to cover ~50% of the population in 1972.29 Limited WHO insecticide susceptibility tests performed in the early 1970s showed high levels of DDT susceptibility among An. punctulatus group species in surveyed parts of PNG and the Solomon Islands.28,31 In 1972 the WHO Malaria Eradication Program in PNG ceased because of operational failure,32 however DDT IRS remained an important control strategy through provincial government activities.33,34 Further attempts at National Program IRS coverage in the late 1970s appeared to reduce anopheline mosquito and Plasmodium falciparum prevalence, but by 1983 insufficient resources and strained community relations brought this effort to a close.35–37

In the 1980s, the PNG Institute of Medical Research and Ministry of Health began to assess the effect of low-cost bednets. Although the studies were conducted in two different endemic sites north of the PNG Central ranges, results showed that both untreated and permethrin-treated nets (Wosera38,39 and Madang,40 respectively) were associated with protection from malaria exposure and prevalence. Additionally, studies showed that untreated bednets were associated with reduced transmission of lymphatic filariasis on Bagabag Island north of Madang.41

Presently, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) has provided support for the distribution of over 2.5 million long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLIN; deltamethrin) at no cost to individual families.42 Introduction of LLINs to all of PNG's 20 Provinces represents the first attempt at a comprehensive plan for mosquito-based malaria control. Of importance, our recently published study observed no phenotypic evidence of resistance to the synthetic pyrethroid insecticides among Anopheles mosquitoes collected at five different PNG malaria-endemic sites.43

In response to intensive insecticide exposure, malaria vectors in other regions of the world have developed resistance to a number of different classes of insecticide compounds. Because several insect species have shown evidence for development of specific polymorphisms in the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) after prolonged exposure to DDT and pyrethroid insecticides,44,45 a number of studies have focused on sequence encoding the S4–S6 region of VGSC domain II.46,47 In Anopheles mosquitoes, knockdown resistance (kdr) has been associated with an A → T mutation (L1014F)46 or a T → C mutation (L1014S)48 in VGSC. These single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been found in African, Indian, and Asian malaria vectors,49–54 and most recently in neighboring Indonesia,55 showing the capacity of these mutations to develop independently in different Anopheles species. Another point mutation in VGSC associated with very high levels of DDT resistance, super-kdr (M918T), has been described in many insects, however this point mutation has not yet been detected in Anopheles.44,45,56

To date, Southwest Pacific malaria vectors have not been surveyed for any mutations associated with insecticide resistance. Assuming validity of An. punctulatus sibling species definitions, and the heterogenous history of insecticide application in PNG, we hypothesize that development, prevalence, and distribution of these mutations would occur independently among members of the An. punctulatus group. Here, we have developed a multiplex DNA-based assay to detect knockdown resistance (kdr) polymorphisms and simultaneously identify individual species in the An. punctulatus group by analysis of sequence polymorphisms in the VGSC gene. Results from our study make it possible to evaluate kdr mutations in a species-specific context by a single assay and provide insight into the evolution of VGSC sequence in the An. punctulatus group. Although additional factors can contribute to insecticide resistance and avoidance, population-based studies from other malaria-endemic regions and results presented here may provide important background data on VGSC polymorphism preceding significant selective pressure of insecticides in PNG.

Materials and Methods

Mosquito collections.

The Entomology Unit of Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research (PNGIMR) collected mosquitoes throughout PNG as part of surveillance studies associated with distribution of LLINs and insecticide susceptibility trials.43 Mosquitoes were collected through landing catch methods, larva collections, and Center for Disease Control light traps as previously described.8,57 Collection sites span 24 villages from seven provinces in PNG and all locations were defined by the global positioning system (Table 1). A subset of these mosquitoes (n = 62) were collected as larvae, and then females reared to adulthood were evaluated by WHO insecticide susceptibility assays by Keven and others.43

Table 1.

Mosquito collection sites

| Site | Province | Altitude** | Latitude | Longitude | Distance to coast** | Species evaluated* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | F1 | H | F4 | K | ||||||

| Albulum† | EAST SEPIK | 354 | −3.5608 | 142.67565 | 20 | 8 | ||||

| Dreikikir† | EAST SEPIK | 375 | −3.5445 | 142.77123 | 20 | 7 | ||||

| Nale | EAST SEPIK | 104 | −3.7725 | 143.07056 | 30 | 11 | 3 | |||

| Nanaha† | EAST SEPIK | 407 | −3.5720 | 142.72650 | 20 | 14 | 2 | |||

| Nghambule | EAST SEPIK | 367 | −3.5950 | 142.75000 | 20 | 4 | ||||

| Peneng†§ | EAST SEPIK | 254 | −3.5435 | 142.65018 | 20 | 16 | ||||

| Yawatong† | EAST SEPIK | 204 | −3.5713 | 142.68988 | 20 | 7 | ||||

| Bilbil† | MADANG | 4 | −5.2885 | 145.76371 | < 0.5 | 5 | 1 | |||

| Dimer†§ | MADANG | 327 | −4.8007 | 145.62395 | 7 | 12 | 4 | |||

| Hudini† | MADANG | 27 | −5.2890 | 145.74413 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Maraga† | MADANG | 13 | −5.3548 | 145.75521 | < 0.5 | 1 | ||||

| Naru†§ | MADANG | 154 | −5.4330 | 145.55000 | 15 | 10 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Sausi†¶ | MADANG | 160 | −5.6999 | 145.53802 | 35 | 12 | 24 | 17 | ||

| Yagaum† | MADANG | 180 | −5.2904 | 145.79873 | 2 | 11 | 3 | |||

| Lorengau†§ | MANUS | 68 | −2.0348 | 147.26136 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| Gingala¶ | MOROBE | 4 | −6.6304 | 147.86111 | < 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Godowa†¶ | MOROBE | 2 | −6.5899 | 147.82233 | < 0.5 | 2 | 21 | 11 | ||

| Mumeng† | MOROBE | 1119 | −6.9314 | 146.60930 | 40 | 36 | 1 | |||

| Ramu†§ | MOROBE | 444 | −6.0900 | 145.98100 | 65 | 1 | 17 | |||

| Pitapena† | WEST SEPIK | 183 | −4.6297 | 141.10485 | 125 | 6 | 1 | 20 | ||

| Yapsie†¶ | WEST SEPIK | 186 | −4.6277 | 141.09645 | 125 | 10 | ||||

| Kuru† | WESTERN | 43 | −8.8718 | 143.06471 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 19 | ||

| Brimba | WHP‡ | 1484 | −5.5883 | 144.68255 | 120 | 1 | ||||

| Singoropa | WHP‡ | 1357 | −5.5420 | 144.65368 | 120 | 1 | ||||

Number of individual mosquitoes included in this study; P = Anopheles punctulatus; F1 = Anopheles farauti s.s.; H = Anopheles hinesorum; F4 = An. farauti 4; K = Anopheles koliensis.

Villages represented by voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) sequence data.

Locations of insecticide susceptibility trials.

altitude and distance to coast measured in meters

An. longirostris collected in these locations for genetic comparison purposes.

WHP = Western Highlands Province.

Morphological species identification.

Morphological identification of mosquitoes was completed using methods previously described where members of the An. punctulatus group were classified as An. koliensis, An. farauti s.l. (sensu lato) or An. punctulatus s.l. by morphologically distinguishing characteristics.10,58 Collected larvae were allowed to mature in the laboratory to facilitate adult morphological identification.43 Mosquitoes morphologically identified as members of the An. punctulatus species group (n = 357) were kept in coded vials containing silica gel until DNA extraction could be completed.

DNA extraction and ITS2 molecular species identification.

Genomic DNA was extracted from single whole mosquitoes and molecular species identification was determined by analyzing polymorphisms within the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) unit of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) using a high-throughput molecular probe method previously described.59

Amplification and sequencing of VGSC.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the IIS4-IIS6 region of the VGSC including introns preceding and following the coding region containing the kdr allele (referred to as intron 1 and intron 2, respectively) was modified from Martinez-Torres and others60 molecular characterization of VGSC in An. gambiae. The PCR amplification reactions (25 μL) were preformed (67 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 6.7 mM MgSO4, 16.6 mM (NH4)2SO4, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 μM dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP, and 2.5 units of thermostable DNA polymerase) using upstream and downstream primers (aDip1 5′-TGGCCSACRCTGAATTTACTC-3′212133 and cDip2 5′-TTKGACAAAAGCAAGGCTAAGAA-3′). The thermocycling program included: 95°C 2 min (1×), 95°C 30 sec, 60°C 30 sec, 72°C 1 min 45 sec (40×), 72°C 4 min (1×) performed using a BioRad DNA Engine Tetrad 2 Peltier Thermal Cycler (Hercules, CA). To evaluate overall amplification efficiency, PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels (1× TBE), stained with SYBR Gold (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and visualized on a Storm 860 using ImageQuant, 5.2 software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). The VGSC PCR yielded a product ranging 1,304–1,380 bp.

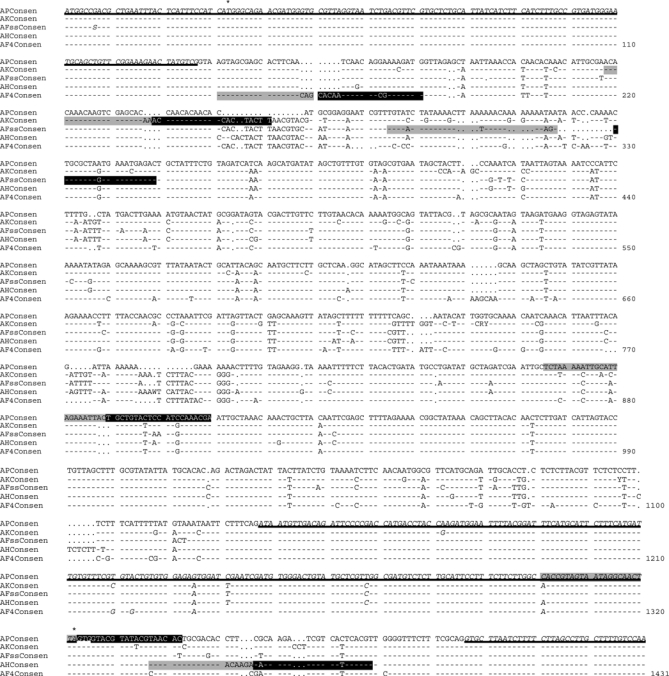

TOPO TA cloning (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) of the amplified VGSC region was preformed for 91 individual mosquitoes (An. punctulatus s.s. n = 31, An. koliensis n = 20, An. farauti s.s. n = 14, An. hinesorum n = 13, An. farauti 4 n = 12, and Anopheles longirostris, a non-An. punctulatus group member, n = 1) followed by single-pass bidirectional plasmid sequencing (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Danvers, MA) (GenBank accession nos.: HQ173903–HQ173993). DNA sequence data were analyzed using Geneious 5.0.3.61 ClustalW262 (default settings: gap open penalty = 10, gap extend penalty = 6.66) was used to generate the VGSC species consensus sequence alignment as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) partial sequence consensus alignment for Anopheles punctulatus, An. farauti s.s., An. hinesorum, An. farauti 4, and An. koliensis. Consensus sequence for each member was created using VGSC sequence from multiple representatives of each species: An. punctulatus s.s. (AP) (GenBank accession nos. HQ173943–HQ173973), An. koliensis (AK) (HQ173974–HQ173993), An. farauti s.s. (AFss) (HQ173904–HQ173917), An. hinesorum (AH) (HQ173918–HQ173930), An. farauti 4 (An. farauti 4) (HQ173931–HQ173942). Consensus sequences were compared with An. longirostris (HQ173903). Coding region sequence is underlined. Asterisks denote positions of the super-kdr (M918T) and kdr (L1014F, L1014S) mutation sites. Ligase detection reaction (LDR) probe locations for species determination and kdr detection are denoted by gray (classification probe) and black (reporter probe) coloration.

Creation of kdr allele controls.

A point mutation was introduced in a VGSC PCR representative creating a positive control possessing the kdr mutation (TTT), using the Stratagene QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA) in accordance with the manufacture's protocol. These samples were then sequenced confirming that the introduction of the kdr point mutation (TTT) had occurred. Additionally, 100 bp oligonucleotides were synthesized to serve as controls, harboring the TTT, TCA, or TTA genotype (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA).

Post-PCR multiplex assay development.

A post-PCR ligase detection reaction-fluorescent microsphere assay (LDR-FMA) was designed based upon VGSC sequence analysis. The LDR probes were designed to detect the presence (TTT or TCA) or absence (TTA) of the L1014F/S mutations associated with knockdown resistance (Table 2). The LDR probes were also designed to detect polymorphic sequence motifs within the VGSC amplified region that appeared to segregate in patterns consistent with An. punctulatus species group designations (Table 2, Figure 1). These LDR probes were predicted to enable the differentiation of An. punctulatus s.s., An. koliensis, An. farauti s.s., An. hinesorum, and An. farauti 4.

Table 2.

| Species-specific | Primer/probe sequence‡¶ | FlexMAP microsphere§ |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Primers | ||

| aDip1 | 5′-TGGCCSACRCTGAATTTACTC-3′ | |

| cDip2 | 5′-TTKGACAAAAGCAAGGCTAAGAA-3′ | |

| LDR Probes | ||

| AF1 TAG | 5′-ttacctttatacctttctttttacTGTAACTATAAAACTAAACAAAAGA-3′ | 30 |

| AF1 Biotin | /5Phos/CTGCGCTAGTGAAATGAGAC/3Bio/ | |

| AH TAG | 5′-ctatctttaaactacaaatctaacTAACACTGCGACACACAAGA-3′ | 100 |

| AH Biotin | /5Phos/CACAAGATCGTCATTCACGT/3Bio/ | |

| AF4 TAG | 5′-tcataatctcaacaatctttctttAGTAGCGAGCACTTCAACAG-3′ | 68 |

| AF4 Biotin | /5Phos/CACAATCAACAGCGAAAGATG/3Bio/ | |

| AK TAG | 5′-ctatctatctaactatctatatcaACACAAACAAGTCGAGCACAA-3′ | 78 |

| AK Biotin | /5Phos/ACCAACACAACACCACTACTT/3Bio/ | |

| AP TAG | 5′-tacactttctttctttctttctttTCTAAAAATTGCATTAGAAATTAC-3′ | 12 |

| AP Biotin | /5Phos/TGCTGTACTCCATCCAAACG/3Bio/ | |

| KDR + TAG | 5′-ctactatacatcttactatactttACCGTAGTAATRGGCAACTTT-3′ | 14 |

| KDR − TAG | 5′-ctacaaacaaacaaacattatcaaACCGTAGTAATRGGCAACTTA-3′ | 28 |

| KDR Biotin | 5/Phos/GTGGTACGTATWCGYAACAY/3Bio/ |

AF1 = An. farauti s.s.; AH = Anopheles hinesorum; AP = Anopheles punctulatus; AF4 = Anopheles farauti 4; and AK = Anopheles koliensis.

VGSC = voltage-gated sodium channel; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; LDR = ligase detection reaction.

Nucleotides in lower case (24 bases) represent TAG sequences added to the 5′ end of each species-specific LDR primer.

Luminex microsphere sets are synthesized to exhibit unique fluorescence and each microsphere set is coupled to different anti-TAG sequences, which are complementary to the species-specific TAG sequence primers.

Single letter nucleotide codes: R = G or A, W = A or T, Y = T or C.

Following amplification of the VGSC target site, PCR products were added to a multiplex LDR where sequence-specific upstream classification probes, specific to the three different kdr locus genotypes (TTT, TCA, or TTA), and species-specific differentiation probes (containing anti-TAG sequences specific to Luminex microsphere sets) ligate to downstream sequence reporter probes (3′-biotinylated) when appropriate target template sequences are available (Table 2). The LDRs (15 μL) were conducted in a solution containing 20 mM Tris-HCL buffer, pH 7.6, 25 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM NAD+, 10 mM dithiothrietol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 nM (200 pmol) of each LDR probe, 1 μL of each PCR product and 2 units of Taq DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). The LDR reactions were initially heated at 95°C for 1 min, followed by 32 thermal cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 58°C for 2 min. The labeling and detection of LDR products was completed as previously described63 using Bio-Plex array reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Results

Previous analysis of a small number of mitochondrial and nuclear genes has demonstrated that significant genetic polymorphism exists within and between members of the An. punctulatus species group species considered to be the most significant vectors of malaria in PNG.59,64–67 Additionally, some polymorphisms within species, namely An. farauti s.s. and An. koliensis, have been shown to be geographically localized.10,64,68 Given these previous findings, and because the VGSC for the An. punctulatus group has not yet been described, we preformed DNA sequence analysis across a segment of this gene (~1,365 bp) observed to include insecticide resistance polymorphisms in a number of insect species.47,69

kdr-associated mutations.

The analysis was based on comparative alignment of 90 An. punctulatus group individual's VGSC sequences where mutations associated with knockdown (kdr) and super knockdown resistance (super-kdr) have previously been identified. This includes sequence encoding the fourth to sixth transmembrane regions of domain II; codons 908 to 1026, including two introns. The occurrence of kdr mutations was evaluated following alignment of 31 alleles of An. punctulatus s.s. (98.5% similar), 14 of An. farauti s.s. (99.4% similar), 13 of An. hinesorum (98.1% similar), 12 of An. farauti 4 (99.0% similar), and 20 of An. koliensis (98.4% similar), kdr (L1014F/S), and super-kdr (M918T). Among the surveyed sequences there was no evidence of mutations associated with insecticide resistance. Additional VGSC sequence comparisons were made between An. punctulatus species group members and similar sequence fragments from An. longirostris (GenBank accession no. HQ173903) co-endemic to PNG, An. dirus (DQ026439) Southeast Asia/Malaysia, and An. gambiae (Y13592) Africa.

VGSC coding sequence analysis.

Further examination of the coding region (358 bp) revealed 53 variable sites where 56 unique mutations were found. Among these, 20 SNPs were observed repeatedly within and between the An. punctulatus sibling species; 36 SNPs were observed only once. Although this error rate (1.08 × 10−3; 35 of 32,310 nucleotides) is higher than standard amplitaq error rates [2.0 × 10−5 to 2.1 × 10−4/bp]70,71), it was not possible to validate these latter SNPs through repeated observation in this study.

Repeated synonymous SNPs.

Within the VGSC coding region sequence, 10 SNPs occurred in multiple An. punctulatus sibling species (codons 909, 910, 924, 956, 973, 987, 996, 999, 1007, 1026; all occupying the third position of each codon [Table 3]). Codons 909 (G>C) and 910 (G>A) were found to harbor mutations that occurred together and separately in each species with the exception of An. farauti s.s. where the mutations were not observed together. The predominant 909-910 haplotype was GG occurring in 41 of 90 sequenced alleles (An. punctulatus s.s., n = 17; An. koliensis, n = 12; An. farauti 4, n = 6). In An. farauti s.s. CG was the predominant 909-910 haplotype (n = 7) and for An. hinesorum, the GA and CG SNP combinations were observed most often and equally (n = 4 for each). At codon 1026 a C>A SNP was observed in 31 of 90 sequenced alleles (An. punctulatus s.s. = 10, An. koliensis = 8, An. farauti s.s. = 5, An. Hinesorum = 5, An. farauti 4 = 2). Six of these repeatedly observed synonymous mutations were shared between two species. At codon 924 a G>A SNP was observed once in both An. farauti s.s. and An. hinesorum; at 956 a C>T transition was observed in An. hinesorum (n = 2) and An. punctulatus s.s. (n = 2); at 973 a T>C transition was observed in An. farauti s.s. (n = 1) and An. koliensis (n = 1); at 987 a T>C transition was observed at fixation in both An. farauti 4 (n = 12) and An. punctulatus s.s. (n = 31); at 996 C>T was observed at fixation in both An. farauti 4 (n = 12) and An. punctulatus s.s. (n = 31); 999 C>T was observed in An. farauti 4 (n = 1) and An. koliensis (n = 9), and A>C at 1007 was observed in An. farauti s.s. (n = 11) and An. punctulatus s.s. (n = 30). The remaining six repeatedly observed synonymous mutations observed in five codons (codons 962, 964, 980, 981, and 985) were species specific. At codon 962 a C>T SNP was observed in two An. farauti 4 alleles; at 964 an A>G SNP was observed at fixation in An. koliensis (n = 20); at 980 a T>G transversion was observed at fixation in An. farauti 4 (n = 12) while a T>C transition was observed at fixation in An. koliensis (n = 20); at 981 A>G was observed at fixation in An. farauti 4 (n = 12), and 985 A>G was observed at fixation in An. punctulatus s.s. (n = 31).

Table 3.

VGSC exon single nucleotide polymorphims* found in Anopheles punctulatus species complex members

| Codon | 909, 910 | 924 | 947 | 956 | 962 | 964§ | 967 | 973 | 980§ | 980, 981§ | 985§ | 987 | 995 | 996 | 999 | 999 | 1007 | 1017 | 1026 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/N† | S | S | S | S | N | S | S | S | N | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | N | S | S | N | S |

| AP (n = 31) | 5 | 7 | 2 | – | 1 | 2 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | 31 | 31 | 1 | 31 | – | – | 30 | 1 | 10 |

| AK (n = 20) | 2 | 4 | 2 | – | – | – | – | 20 | – | 1 | 20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9 | – | 1 | 8 |

| AF1 (n = 14) | 7 | 3 | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | 11 | – | 6 |

| AH (n = 13) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 5 |

| AF4 (n = 12) | 1 | 3 | 2 | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | – | 12 | – | 12 | – | 12 | 2 | 1 | – | – | 2 |

| AL (n = 1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

Specific SNPs in codons: 909,910: G>CG,GG>A,G>C G>A, 924G>A, 947 T>C, 956C>T, 962C>T, 964A>G, 967A>G, 973T>C, 980T>C, 980,981 T>G A>G, 985A>G, 987T>C, 995T>C, 996C>T, 999C>T, 999T>C, 1007A>C, 1017T>C, 1026C>A.

S = synonymous mutation; N = nonsynonymous mutation: all synonymous mutations occur at the third position of identified codon, nonsynonymous mutations occur at the second position of the codon.

Species-specific fixed mutations.

Repeated nonsynonymous SNPs.

Coding sequence mutations were observed in separate codons in multiple species (codons 947, 967, 999, 1017). At codon 947 a T>C SNP was observed in one An. hinesorum allele and one An. punctulatus s.s. allele (codon position 1) and resulted in a phenylalanine to leucine amino acid substitution; at 967 an A>G SNP was observed in one An. farauti s.s. allele (codon position 2) and one An. punctulatus s.s. allele and resulted in an asparagine to serine substitution; at 999 a T>C SNP was observed in two An. farauti 4 alleles and one An. farauti s.s. allele (codon position 2) and resulted in a valine to alanine substitution; at 1017 a T>C SNP observed in one An. hinesorum, one An. koliensis, and one An. punctulatus s.s. allele (codon position 2) resulted in a leucine to proline substitution.

VGSC sequence comparisons outside the An. punctulatus species group.

To augment the analysis of sequence variation among the An. punctulatus complex sibling species evaluated here, we performed additional VGSC sequence comparisons with similar coding region sequence fragments for An. longirostris (358 bp), An. dirus (213 bp), and An. gambiae (348 bp). Between An. longirostris and the 90 An. punctulatus sibling species alleles we observed five synonymous mutations unique to An. longirostris (954 T>C, 979 C>T, 981 A>C, 989 G>C, and 1012 C>A). Two synonymous mutations in An. longirostris were shared with at least one An. punctulatus species group allele (995 C>T An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 1]; 996 C>T An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 31], An. farauti 4 [n = 14]). One synonymous An. longirostris mutation occurred at the An. punctulatus s.s. SNP site 981 with a unique sequence change A>C compared with A>G. Between a partial An. dirus sequence and the An. punctulatus sibling species alleles we identified eight synonymous mutations unique to An. dirus (978 G>A, 989 G>C [also observed in An. longirostris], 993 T>C, 999 C>G, 1004 T>C, 1012 C>A [also observed in AL], 1013 C>T and 1014 T>C). Six synonymous mutations were observed to be shared among one or more An. punctulatus group members (956 C>T An. hinesorum [n = 2], An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 2]; 973 T>C An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 1], An. koliensis [n = 1]; 980 T>G An. farauti 4 [n = 12]; 981 A>G An. farauti 4 [n = 12], 996 C>T An. farauti 4 [n = 12], An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 31]; and 1026 C>A An. farauti 4 [n = 2], An. hinesorum [n = 5], An. farauti s.s. [n = 6], An. koliensis [n = 8], An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 10]). Finally, between a partial An. gambiae sequence and the An. punctulatus sibling species alleles we identified 19 unique synonymous mutations in An. gambiae (940 G>A, 955 T>G, 963 A>G, 969 G>A, 974 T>C, 979 T>C [also observed in An. longirostris], 982 G>A, 989 G>A, 992 C>T, 999 C>A, 1002 T>A, 1003 T>A, 1004 C>T, 1008 C>T, 1010 A>G, 1012 C>A [also observed in An. longirostris and An. dirus], 1013 C>T [also observed in An. dirus], 1015 G>C, and 1018 T>C). Nine synonymous SNPs were observed to be shared among one or more An. punctulatus group members (956 C>T [also observed in An. dirus] An. hinesorum [n = 2], An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 2]; 962 C>T An. farauti 4 [n = 2]; 981 A>G [also observed in An. dirus] An. farauti 4 [n = 12]; 983 T>C An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 1]; 995 C>T [also observed in An. longirostris] An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 1]; 997 C>T An. farauti 4 [n = 1]; 1000 T>C An. koliensis [n = 1]; 1007 A>C An. farauti s.s. [n = 11], An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 30]; and 1026 C>A [also observed in An. dirus] An. farauti 4 [n = 2], An. hinesorum [n = 5], An. farauti s.s. [n = 6], An. koliensis [n = 8], An. punctulatus s.s. [n = 10]).

Test for evidence of selection.

Because the potential exists for this gene to be under selection and since there has been a history of insecticide exposure among these species it becomes necessary to look at the nature of the mutations in the coding regions of the VGSC. Previously, we described 20 SNPs (16 synonymous and 4 nonsynonymous) occurring in the coding region analyzed, which were found in more than one sequence. Seven synonymous mutations (964 A>G An. koliensis n = 20, 980 T>C An. koliensis n = 20, 980 T>G An. farauti 4 n = 12, 981 A>G An. farauti 4 n = 12, 985 A>G An. punctulatus s.s. n = 31, 987 T>C An. punctulatus s.s. n = 31, and An. farauti 4 n = 12) were fixed within at least one An. punctulatus sibling species. The remaining 9 synonymous mutations were found to be polymorphic in one or more of the sibling species (909 G>C An. farauti 4 n = 3, An. farauti s.s. n = 7, An. hinesorum n = 13, An. koliensis n = 4, An. punctulatus s.s. n = 31, 910 G>A An. farauti 4 n = 5, An. farauti s.s. n = 3, An. hinesorum n = 6, An. koliensis n = 6, An. punctulatus s.s. n = 8, 924 G>A An. farauti s.s. n = 1, An. hinesorum n = 1, 956C>T An. punctulatus s.s. n = 2, An. hinesorum n = 2, 962 C>T An. farauti 4 n = 2, 973 T>C An. farauti s.s. n = 1, An. farauti 4 n = 1, 999 C>T An. koliensis n = 9, An. farauti 4 n = 1, 1007 A>C An. punctulatus s.s. n = 30, An. farauti s.s. n = 11, 1026 C>A An. punctulatus s.s. n = 10, An. koliensis n = 8, An. farauti s.s. n = 6, An. hinesorum n = 5, An. farauti 4 n = 5). All 4 nonsynonymous mutations were found to be polymorphic in one or multiple sibling species (947 T>C An. punctulatus s.s. n = 1, An. hinesorum n = 1, 967 An. punctulatus s.s. n = 1, An. farauti s.s. n = 1, 999 T>C An. farauti s.s. n = 1, An. farauti 4 n = 2, 1017 T>C An. punctulatus s.s. n = 1, An. koliensis n = 1, An. hinesorum n = 1). The assumption of neutrality was tested by the McDonald-Kreitman test72 using this coding region data. The results were non-significant suggesting that there is no evidence for selection in this region of the gene among the species in this sample. Given that the focus of this analysis was only on a portion of the VGSC gene, it is possible that selection could be occurring elsewhere.

VGSC intron sequence analysis.

Intron 1 was of variable length within (exception An. farauti s.s.) and between species; An. punctulatus s.s. ranged from 880 to 923 bp, An. farauti s.s. 928 bp, An. hinesorum 939 to 950 bp, An. farauti 4 925 to 938 bp, and An. koliensis 940 to 953 bp. Intron 2 varied in size between species; An. punctulatus s.s. 65 bp, An. farauti s.s. 65 bp, An. hinesorum 68 bp, An. farauti 4 66 bp, and An. koliensis 68 bp. Further unique species-specific insertions and deletions were also observed within introns 1 and 2. These differences are shown in Figure 1 where consensus sequences from each An. punctulatus sibling species of interest were aligned using ClustalW. When the An. punctulatus sibling species consensus sequences were compared with An. longirostris, they were found to be 77–79% similar.

We then analyzed the intronic regions for each species independently (Table 4). For intron 1 (ranging 880–953 bp) all An. farauti s.s. sequences had the greatest pairwise percent identity, 99.5%. High percentage identity is not surprising as all 14 sequences were the same length, leaving differences to be SNPs alone. Pairwise percent identity for the remaining within species comparisons were as follows: An. punctulatus s.s. (98.1%), An. hinesorum (97.8%), An. farauti 4 (97.8%), and An. koliensis (98.1%). Pairwise percent identity was 88.5% when comparing all An. punctulatus complex members. When comparing all An. punctulatus sibling species with An. longirostris the pairwise percent identity dropped slightly to 87.8%, however when comparing An. longirostris individually to a representative of each species, pairwise percent identities were < 69%. Intra- and inter-species complex relationships are further defined by considering the percent of identical sites within each comparison. Intra-species comparisons observed nucleotide identity over the analyzed gene fragment of 84.2% for An. punctulatus s.s., 97.2% for An. farauti s.s., 91.3% for An. hinesorum, 95.5% for An. farauti 4, and 91.3% for An. koliensis. With inter-species comparisons among An. punctulatus sibling species allelic percent identity dropped to 51.7%; 40% when An. longirostris was added to this sequence comparison. This further demonstrates that intronic sequences appear to have been conserved within each species and among members of the An. punctulatus species group. Given that this gene is possibly under selective pressure and natural selection reduces the genetic variation of organisms we would expect to see little to no variation within this gene within species.

Table 4.

PNG Anopheles* voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) intron sequence comparisons

| Aligned length† | Range | Identical sites | % | Pairwise % identity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intron 1 | |||||

| AP | 926 | 880–923 | 780 | 84.2 | 98.1 |

| AF1 | 928 | 928 | 902 | 97.2 | 99.5 |

| AH | 951 | 939–950 | 868 | 91.3 | 97.8 |

| AF4 | 941 | 925–938 | 899 | 95.5 | 98.8 |

| AK | 955 | 940–953 | 872 | 91.3 | 98.1 |

| AP Complex | 1007 | 880–953 | 521 | 51.7 | 88.5 |

| APC + AL‡ | 1000 | 880–953 | 409 | 40.9 | 87.8 |

| Intron 2 | |||||

| AP | 65 | – | 63 | 96.9 | 99.8 |

| AF1 | 65 | – | 63 | 96.9 | 99.6 |

| AH | 68 | – | 61 | 89.7 | 97.7 |

| AF4 | 66 | – | 64 | 97 | 99.5 |

| AK | 68 | – | 66 | 97.1 | 99.1 |

| AP Complex | 71 | 65–68 | 43 | 60.6 | 90.8 |

| APC† + AL | 71 | 64–68 | 31 | 43.7 | 90.2 |

AP = Anopheles punctulatus; AF1 = Anopheles farauti s.s.; AH = Anopheles hinesorum; AF4 = An. farauti 4; AK = Anopheles koliensis.

Base pairs.

APC = An. punctulatus species complex; AL = Anopheles longirostris.

Unlike intron 1, intron 2 was not observed to vary in size within species and is much smaller (65–68 bp). Pairwise percent identity of all the species was found to be greater than 97.7% (An. hinesorum) with four species (An. punctulatus s.s., An. farauti s.s., An. farauti 4, and An. koliensis) above 99%. Comparison of all An. punctulatus species group members showed 90.8% pairwise percent identity and when An. longirostris was added to the comparison this percentage dropped slightly to 90.2%. Conserved intron 2 sequences further demonstrated species similarities through analysis of sequence identity. An. punctulatus s.s., An. farauti s.s., An. farauti 4, and An. koliensis all have greater than 96.9% identical sites, and An. hinesorum has 89.7% identical sites. When comparing all An. punctulatus s.s. group members together, there were only 60.6% identical sites; overall sequence identity dropped to 43.7% when An. longirostris was added to these comparisons.

Phylogenetic comparison of An. punctulatus sibling species using VGSC sequence.

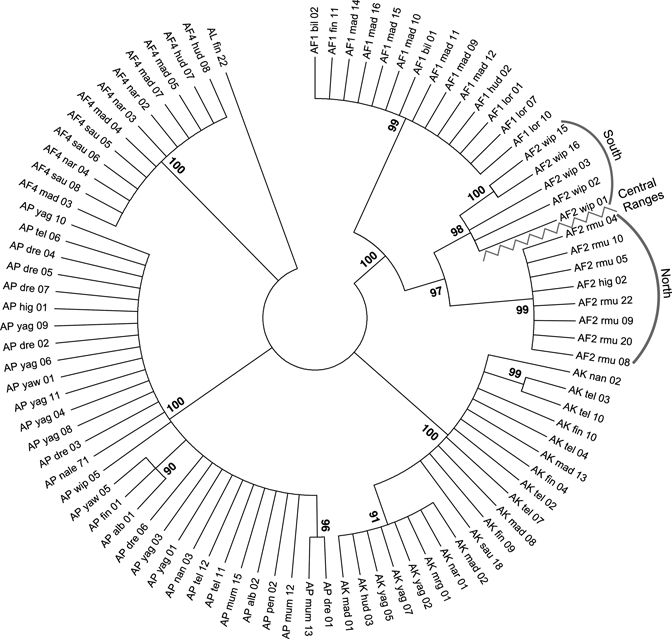

Given that species-specific polymorphism in both the coding and intronic regions were observed in the multiple species alignment (Figure 1) in addition to the multiple SNPs shared among more than one species (Table 3), we preformed a phylogenetic comparison of the entire sequenced portion of VGSC (1,303–1,379 bp) of the 90 An. punctulatus species group members. Anopheles longirostris was used as an out-group. Using ClustalW (at default parameters), sequences were aligned and phylogenetic relationships were inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method in MEGA573 with 1,000 bootstrap replicates (Figure 2). Branches with bootstrap values < 80 were collapsed.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of 90 Anopheles punctulatus species complex members. Individual mosquitoes have been described, including GenBank accession numbers for all VGSC sequences. Designations for each mosquito included in this analysis are represented by an abbreviated identifier for each species (e.g., AP), collection site, and unique mosquito number. For example, “AF1_bil_02” is a unique An. farauti s.s. representative collected from Bilbil village. Anopheles longirostris (AL), a non-An. punctulatus species group member, was used as the out-group. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.85 The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 0.58406478 is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches.86 Branches with bootstrap values < 80 were condensed. All positions containing alignment gaps and missing data were eliminated only in pairwise sequence comparisons (Pairwise deletion option). There were a total of 1,430 positions in the final dataset. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA5.73

We observed that each of the An. punctulatus sibling species formed its own clade with bootstrap support greater than 97, and that no individual mosquito was found in a clade that was different from its initial species identification based on detailed comparisons of ITS2 rDNA sequence polymorphisms. Phylogenetic analyses also observed significant stratification between An. hinesorum mosquitoes collected north and south of the PNG Central Ranges. Overall, our sequence comparisons suggested that the VGSC gene sequence would be a reliable candidate for molecular species identification that could be coupled with probes investigating the kdr-associated SNPs.

Post-PCR LDR-FMA design and validation.

Conserved regions of the amplified VGSC sequence surrounding both the location of the M918T and L1014F/S mutations afforded the opportunity to build ligase-detection (LDR) probes to monitor for the presence (heterozygous or homozygous) or absence of these mutations in a post-PCR-based LDR-FMA. Given the high bootstrap support for the ability of VGSC to differentiate members of the An. punctulatus group, we targeted species-specific regions of the amplified VGSC region in development of LDR probes to differentiate members of the An. punctulatus group. These probes, coupled with the kdr detection probes, could simultaneously monitor the presence or absence of the kdr mutations and differentiate members of the An. punctulatus species group. Locations where kdr mutation detection and species-specific classification LDR reporter probes hybridized with VGSC template PCR products are shown in the VGSC consensus alignment for An. punctulatus s.s., An. farauti s.s., An. hinesorum, An. farauti 4, and An. koliensis (Figure 1).

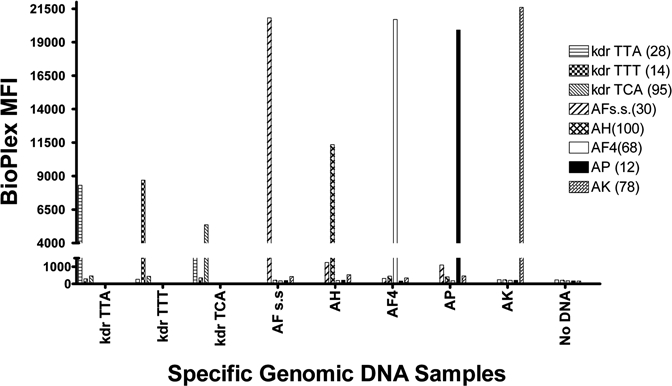

The specificity of the assay was demonstrated using probes identified in Table 2 to differentiate PCR products amplified from previously sequenced species-specific controls including two controls, known to harbor the sensitive (TTA) or resistant (TTT or TCA) kdr mutation at amino acid position 1014. As members of the An. punctulatus species group are known to carry Plasmodium9,11,12 and Wuchereria parasites10 as well as human blood meals,3,12 six additional controls were included containing P. falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale, Wuchereria bancrofti, and human genomic DNA.

Results of control LDR-FMA tests (Figure 3) showed high specificity for kdr allele differentiation (kdr-sensitive [TTA] mean fluorescence intensity [MFI] > 23,000; kdr-resistant [TTT or TCA] > 15,000 MFI; background signals < 3,000 MFI) as each LDR-FMA probe set detected only the kdr allele present in the genomic controls and displayed. Simultaneously, each species-specific LDR-FMA probe set (An. punctulatus s.s. MFI > 21,000; An. koliensis > 23,000; An. farauti s.s. > 23,000; An. hinesorum > 10,500; An. farauti 4 > 22,000), detected only the species expected; all species probe background signals were below MFIs of 2,000. Results showed that the LDR probes designed to target the species-specific polymorphisms described here detected only the species present and no others. Fluorescent signals from the parasite and human samples were below a background of 160 MFI (data not shown), showing that the presence of parasites and human blood meal would not obscure Anopheles species identification or kdr mutation detection.

Figure 3.

Detection of species-specific DNAs by the Anopheles species/kdr detection multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-ligase detection reaction (LDR)-florescent microsphere assay (FMA). Data represents a summary of 14 individual control experiments detecting AP, AK, AFs.s., AH, and AF4 as well as Plasmodium falciparum (Pf), P. vivax (Pv), P. malariae (Pm), P. ovale (Po), Wuchereria bancrofti (Wb) and human (HBS) genomic DNAs. DNAs known to contain the kdr mutations (TTT and TCA) and a sample that did not contain the kdr mutation (TTA) were also included to test kdr sensitive (kdr TTA) and kdr resistant (kdr TTT and kdr TCA) probes. Whereas genomic DNAs were added individually into the control reaction, LDR and FMA reactions included oligonucleotide probes representing all five Anopheles species as well as KDR- and both KDR+ probes. Numbers in parentheses next to species designations in the legend (30), (100), (68), (78), (12), (14), (28), (95) identify Luminex FlexMap microspheres (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX). “No DNAs” identifies a blank sample to which no genomic DNAs were added.

Application of VGSC multiplex assay: analysis of mosquito collections for kdr mutation and species determination.

The VGSC multiplex assay was then used to evaluate a sample collection of 312 mosquitoes for the kdr mutation and species identification. All 312 mosquitoes assayed were determined to be homozygous for the sensitive kdr allele (TTA/TTA). Results in Table 5 summarize the comparison of species identification using the VGSC multiplex assay to a similar molecular classification method that probes differences in An. punctulatus sibling species ITS2 rDNA sequences.59 One discordant sample was detected among the 312 mosquitoes assayed; by VGSC LDR-FMA this mosquito was identified as An. punctulatus s.s., where ITS2 LDR-FMA species were identified as An. farauti s.s.. These results show 99.7% concordance between the two species identification methods while simultaneously identifying the kdr mutation status in a large sample set of field-collected mosquitoes.

Table 5.

Concordance assessment of molecular ITS2 and VGSC classification* methods for Anopheles punctulatus sibling species

| ITS2 | VGSC LDR-FMA species ID | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | AK | AF1 | AF2 | AF4 | |

| AP | 134 | – | – | – | |

| AK | – | 68 | – | – | – |

| AF1 | 1 | – | 38 | – | – |

| AF2 | – | – | – | 47 | – |

| AF4 | – | – | – | – | 24 |

AP = Anopheles punctulatus s.s.; AF = Anopheles farauti s.s./An. farauti 1; AH = Anopheles hinesorum AF4 = An. farauti 4; AK = Anopheles koliensis.

VGSC = voltage-gated sodium channel; LDR = ligase detection reaction; FMA = fluorescent microsphere assay.

Mosquitoes that were evaluated for insecticide susceptibility using WHO insecticide bioassays (as described previously in Keven and others43) were also analyzed in this assay. Sixty-two mosquitoes, collected from five geographically distinct areas (Table 1) were previously tested and reported to be susceptible to either 0.05% lambda-cyhalothrin-treated filter paper (n = 26, locations: Dimer, Peneng, and Lorengau) or new 55 mg/m2 deltamethrin-treated LLIN (n = 36, locations: Ramu [Madang, Naru, and Dimer). These mosquitoes were evaluated using the VGSC LDR-FMA. All 62 samples gave a strong signal for the presences of the susceptible genotype (TTA; average MFI 8,182; signals for TTT and TCA probes fell within expected background [< 3,000 MFI]) showing that these samples were both phenotypically susceptible and lacked the L1014F/S mutations associated with kdr.

Discussion

Here, we have characterized DNA sequence polymorphism in a segment of the VGSC gene (~1,350 bp) among sibling species of the An. punctulatus group known to be significant vectors of human malaria and filariasis in Papua New Guinea.7–12 This region of the VGSC gene encodes the fourth to sixth transmembrane regions (domain II) of the VGSC protein,60 and is known to harbor mutations associated with knockdown resistance to pyrethroids and DDT in many insect species (Anopheles,48,52,53,55,60,74–79 Culex,80,81 Musca domestica [House fly],82,83 Blattella germanica [German cockroach]).83,84

In this characterization of VGSC genetic variation we were able to determine that the well-known kdr-associated mutations (L1014F/S; M918T82) were not observed among the extant mosquitoes of the An. punctulatus species group. Although our collections were not comprehensive across PNG, individual mosquitoes were available at multiple locations along the PNG north coast where transmission of malaria and filariasis is intense. Because many of these collection sites occurred in regions that have historically been the focus of DDT larviciding applications22,27 and IRS programs,25,29 it is possible that ancestral An. punctulatus species group populations have been exposed to positive selection that would favor the kdr-associated mutations. This included mosquito collection sites (Table 1) in six mainland Provinces and Manus Island Province. The greatest distance between sample collection sites within each species ranged from 85 km for An. farauti 4 to 883 km for An. farauti s.s., with all species (except for An. farauti 4) having collections spanning at least 580 km in distance. For this study An. farauti 4 collections were limited to pockets north of the Central Ranges. Significant geographical barriers also separated collection sites for An. farauti s.s. (island locations) and An. hinesorum (locations north and south of the Central Ranges). Interestingly, although our phylogenetic analysis provided evidence for significant population stratification within An. hinesorum collected north and south of the PNG Central Ranges, significant VGSC sequence variation was not observe between An. farauti s.s. mosquitoes collected between the PNG mainland and Manus Island.

Furthermore, the overall sequence analysis revealed a wide range of synonymous and nonsynonymous SNP and insertion/deletion polymorphisms, the latter exclusively within “so-called” introns 1 and 2. The additional coding region SNPs enabled us to perform population genetic comparisons to evaluate evidence for selective pressure on this gene sequence and sequence-based relationships within and between sibling species. McDonald-Kreitman testing,72 based on the observation of 16 synonymous versus 4 non-synonymous SNPs in the VGSC coding region analyzed here indicated that there was no evidence for selection in this gene segment. However, it may be important to note that these observations have been based on mosquitoes collected over the past 5–10 years during a time when no concerted insecticide dispersal program has been under implementation in PNG. Therefore, it is not possible to rule out the potential that the kdr-associated mutations arose in the past and have now drifted out of current An. punctulatus sibling species populations.

Given results of the McDonald-Kreitman test, reservations about using VGSC sequences to perform phylogenetic analyses may be reduced. The Neighbor-Joining analysis reported in Figure 2,73,85,86 shows very strong conservation of sequence within each species cluster and no evidence for gene flow between species. Because many of the polymorphisms characterizing the different species included consistently observed insertions and deletions, our results suggested that it might be possible to develop highly specific DNA probes for species identification. Consistent with these phylogenetic results (apart from one sample), DNA probes based on VGSC sequence polymorphisms produced species identification results consistent with earlier ITS2 analyses for over 300 mosquitoes collected across our widely distributed sampling sites; expanded surveys will be necessary to verify that these results can be consistently reproduced throughout the Southwest Pacific region where the An. punctulatus sibling species are endemic. Although our resulting LDR-FMA multiplex assay did not detect any evidence of kdr-associated mutations from any of the PNG study sites surveyed, our analyses revealed an important feature of VGSC sequence evolution and an important potential challenge for mosquito control. Because our results provide evidence for independent acquisition and maintenance of VGSC sequence variation, kdr-associated mutations in this gene sequence would also be expected to emerge independently within each species. Therefore, whether VGSC kdr-associated mutations or mutations in other genes lead to insecticide resistance, assays must be developed to monitor each of the An. punctulatus sibling species with equal efficiency, specificity, and sensitivity. Therefore, molecular diagnostic assay developed here, offers advantages over other PCR-based species identification strategies by querying insecticide resistance associated and species-specific polymorphisms in a single multiplex test. Currently, countrywide planning and distribution of LLINs is underway in the Solomon Islands34,87 and Papua New Guinea,42,43 respectively. A recent report describing the discovery of the VGSC L1014F kdr mutation in populations of Anopheles from neighboring Indonesia suggests that An. punctulatus sibling species in this same region55 may be experiencing insecticide exposure that will select for kdr-associated mutations.

Integrated vector management strategies require a means to continuously monitor and assess the vector species composition in an endemic region and elements of the vector's biology. Although kdr is a concern, it is important to understand this phenotype within the context of additional gene sequence and gene expression polymorphism, physiological and behavioral heterogeneity. Because insecticide resistance can develop through many different routes88 it is becoming necessary to broaden evaluation of insecticide resistance beyond candidate gene-based investigations as demonstrated by recent genomic comparison studies of An. gambiae.89,90

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to PNGIMR Entomology Unit for aid in mosquito collections and morphological identification. We thank Wallace Peters, David Serre, and Scott Small for helpful discussions and constructive criticism leading to completion of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (AI065717) and Fogarty International Center (TW007872, TW007377, and TW007735). Mosquito collection was also supported by the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria Round 3 malaria grant to PNG.

Authors' addresses: Cara N. Henry-Halldin, Kogulan Nadesakumaran, Allison M. Zimmerman, James W. Kazura, and Peter A. Zimmerman, Center for Global Health and Diseases, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, E-mails: vgx5@cdc.gov, kxn80@case.edu, amz23@case.edu, jxk14@case.edu, and paz@case.edu. John Bosco Keven, Edward Thomsen, and Lisa J. Reimer, Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research-Madang, Madang, Papua New Guinea, E-mails: jbkeven@gmail.com, edward.thomsen@case.edu, and lisa.reimer@case.edu. Peter Siba, Ivo Mueller, and Manuel W. Hetzel, Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research-Goroka, Eastern Highlands, Papua New Guinea, E-mails: peter.siba@pngimr.org.pg, ivomueller@fastmail.fm, and manuel.hetzel@pngimr.org.pg.

References

- 1.Rozeboom LE, Knight KL. The punctulatus complex of Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae) J Parasitol. 1946;32:95–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryan JH. Morphological studies on the Anopheles punctulatus Dönitz complex. Trans R Entomol Soc Lond. 1974;125:413–435. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charlwood JD, Dagoro H, Paru R. Blood-feeding and resting behavior in the Anopheles punctulatus Dönitz complex (Diptera: Culicidae) from coastal Papua New Guinea. Bull Entomol Res. 1985;75:463–476. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper RD, Waterson DG, Frances SP, Beebe NW, Sweeney AW. Speciation and distribution of the members of the Anopheles punctulatus (Diptera: Culicidae) group in Papua New Guinea. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:16–27. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley DH, Paru R, Dagoro H, Bryan JH. Allozyme analysis reveals six species within the Anopheles punctulatus complex of mosquitoes in Papua New Guinea. Med Vet Entomol. 1993;7:37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1993.tb00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beebe NW, Cooper RD. Distribution and evolution of the Anopheles punctulatus group (Diptera: Culicidae) in Australia and Papua New Guinea. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:563–574. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bockarie M, Tavul L, Kastens W, Michael E, Kazura J. Impact of untreated bednets on prevalence of Wuchereria bancrofti transmitted by Anopheles farauti in Papua New Guinea. Med Vet Entomol. 2002;16:116–119. doi: 10.1046/j.0269-283x.2002.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bockarie MJ, Fischer P, Williams SA, Zimmerman PA, Griffin L, Alpers MP, Kazura JW. Application of a polymerase chain reaction-ELISA to detect Wuchereria bancrofti in pools of wild-caught Anopheles punctulatus in a filariasis control area in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:363–367. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burkot TR, Molineaux L, Graves PM, Paru R, Battistutta D, Dagoro H, Barnes A, Wirtz RA, Garner P. The prevalence of naturally acquired multiple infections of Wuchereria bancrofti and human malarias in anophelines. Parasitology. 1990;100:369–375. doi: 10.1017/s003118200007863x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benet A, Mai A, Bockarie F, Lagog M, Zimmerman P, Alpers MP, Reeder JC, Bockarie MJ. Polymerase chain reaction diagnosis and the changing pattern of vector ecology and malaria transmission dynamics in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper RD, Waterson DG, Frances SP, Beebe NW, Pluess B, Sweeney AW. Malaria vectors of Papua New Guinea. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:1495–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burkot TR, Graves PM, Paru R, Wirtz RA, Heywood PF. Human malaria transmission studies in the Anopheles punctulatus complex in Papua New Guinea: sporozoite rates, inoculation rates, and sporozoite densities. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:135–144. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black RH. Malaria in the South-west Pacific. 1955. pp. 1–56. South Pacific Commission Technical Paper 81.

- 14.Heydon GA. Malaria at Rabaul. Med J Aust. 1923;2:625–633. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coates J, Boyd J. Malaria. Preventive Medicine in World War II: Communicable Diseases. Volume 6. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joy RJ. Malaria in American troops in the South and Southwest Pacific in World War II. Med Hist. 1999;43:192–207. doi: 10.1017/s002572730006508x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell PF. Lessons in malariology from World War II. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1946;26:5–13. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1946.s1-26.1.tms1-260010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO . Malaria: Sixth Report of the Expert Committee. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1957. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pampana E. A Textbook of Malaria Eradication. London: Oxford University Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laird M. Observations on Anopheles punctulatus Donitz 1901 and Anopheles farauti Laveran 1902 at Palmalmal and Manginuna, New Britian, during July and August 1945. Trans R Soc NZ. 1946;76:148–157. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laird M. Notes on the mosquitoes of Nissan Island, Territory of New Guinea. Pac Sci. 1952;6:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackerras I, Ratcliffe F, Gilmour D, Mules M. Dispersal of DDT from Aircraft for Mosquito Control. CSIRO Bulletin. Melbourne: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization; 1950. pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bang FB, Hairston NG, Maier J, Roberts FH. DDT spraying inside houses as a means of malaria control in New Guinea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1947;40:809–822. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(47)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metselaar D. A pilot project of residual-insecticide spraying to control malaria transmitted by the Anopheles punctulatus group in Netherlands New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1956;5:977–987. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1956.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters W. Malaria control in Papua and New Guinea. P N G Med J. 1959;3:66–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spencer M. Malaria in the d'Entrecasteaux Islands, with particular reference to Anopheles farauti Laveran. Proc Linn Soc N S W. 1965;90:115–127. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer M. The history of malaria control in the southwest Pacific region, with particular reference to Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. P N G Med J. 1992;35:33–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avery J. A review of the malaria eradication programme in the British Solomon Islands 1970–1972. P N G Med J. 1974;17:50–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parkinson A. Malaria in Papua New Guinea 1973. P N G Med J. 1974;17:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters W. Studies on the epidemiology of malaria in New Guinea Part I. Holoendemic Malaria–The Clinical Picture. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1960;54:242–249. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(60)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spencer T, Spencer M, Venters D. Malaria vectors in Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 1974;7:22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Health PNGDo. Papua New Guinea National Health Plan 1986–1900. Port Moresby: Papua New Guinea Department of Health; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Opeskin B. Malaria in Pacific populations: seen but not heard? J Popul Res. 2009;26:175–199. [Google Scholar]

- 34.PMISG Malaria on isolated Melanesian islands prior to the initiation of malaria elimination activities from The Pacific Malaria Initiative Survey Group on behalf of the Ministries of Health of Vanuatu and Solomon Islands. Malar J. 2010;9:218. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cattani JA, Tulloch JL, Vrbova H, Jolley D, Gibson FD, Moir JS, Heywood PF, Alpers MP, Stevenson A, Clancy R. The epidemiology of malaria in a population surrounding Madang, Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;35:3–15. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genton B, Al-Yaman F, Beck H, Hii J, Mellor S, Narara A, Gibson N, Smith T, Alpers M. The epidemiology of malaria in the Wosera area, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea in preparation for vaccine trials. I: malariometric indices and immunity. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1995;89:359–376. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1995.11812965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller I, Bockarie M, Alpers M, Smith T. The epidemiology of malaria in Papua New Guinea. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:253–259. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Genton B, Hii J, al-Yaman F, Paru R, Beck HP, Ginny M, Dagoro H, Lewis D, Alpers MP. The use of untreated bednets and malaria infection, morbidity and immunity. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;88:263–270. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1994.11812866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hii JL, Smith T, Vounatsou P, Alexander N, Mai A, Ibam E, Alpers MP. Area effects of bednet use in a malaria-endemic area in Papua New Guinea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graves PM, Brabin BJ, Charlwood JD, Burkot TR, Cattani JA, Ginny M, Paino J, Gibson FD, Alpers MP. Reduction in incidence and prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum in under-5-year-old children by permethrin impregnation of mosquito nets. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65:869–877. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Genton B, Hii J, Al-Yaman F, Paru R, Beck H, Ginny M, Dagoro H, Lewis D, Alpers M. The use of untreated bednets and malaria infection, morbidity and immunity. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;88:263–270. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1994.11812866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hetzel MW. An integrated approach to malaria control in Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 2009;52:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keven JB, Henry-Halldin CN, Thomsen EK, Mueller I, Siba PM, Zimmerman PA, Reimer LJ. Pyrethroid susceptibility in natural populations of the Anopheles punctulatus group (Diptera: Culicidae) in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:1259–1261. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vais H, Williamson M, Devonshire A, Usherwood P. The molecular interactions of pyrethroid insecticides with insect and mammalian sodium channels. Pest Manag Sci. 2001;57:877–888. doi: 10.1002/ps.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williamson M, Martinez-Torres D, Hick C, Devonshire A. Identification of mutations in the housefly para-type sodium channel gene associated with knockdown resistance (kdr) to pyrethroid insecticides. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:51–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02173204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martinez-Torres DC, Williamson MS, Darriet F, Berge JB, Devonshire AL, Guillet P, Pasteur N, Pauron D. Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol Biol. 1998;7:179–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1998.72062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soderlund DM. Pyrethroids, knockdown resistance and sodium channels. Pest Manag Sci. 2008;64:610–616. doi: 10.1002/ps.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ranson H, Jensen B, Vulule J, Wang X, Hemingway J, Collins F. Identification of a point mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:491–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nwane P, Etang J, Chouaibou M, Toto JC, Kerah-Hinzoumbe C, Mimpfoundi R, Awono-Ambene HP, Simard F. Trends in DDT and pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.s. populations from urban and agro-industrial settings in southern Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reimer L, Fondjo E, Patchok ÈS, Diallo B, Lee Y, Ng A, Ndjemai H, Atangana J, Traore S, Lanzaro G. Relationship between kdr mutation and resistance to pyrethroid and DDT insecticides in natural populations of Anopheles gambiae. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:260–266. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[260:rbkmar]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santolamazza F, Calzetta M, Etang J, Barrese E, Dia I, Caccone A, Donnelly MJ, Petrarca V, Simard F, Pinto J, della Torre A. Distribution of knock-down resistance mutations in Anopheles gambiae molecular forms in west and west-central Africa. Malar J. 2008;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh O, Dykes C, Das M, Pradhan S, Bhatt R, Agrawal O, Adak T. Presence of two alternative kdr-like mutations, L1014F and L1014S, and a novel mutation, V1010L, in the voltage gated Na+ channel of Anopheles culicifacies from Orissa, India. Malar J. 2010;9:146. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verhaeghen K, Van Bortel W, Trung H, Sochantha T, Keokenchanh K, Coosemans M. Knockdown resistance in Anopheles vagus, An. sinensis, An. paraliae and An. peditaeniatus populations of the Mekong region. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:59–70. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh OP, Dykes CL, Lather M, Agrawal OP, Adak T. Knockdown resistance (kdr)-like mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel of a malaria vector Anopheles stephensi and PCR assays for their detection. Malar J. 2011;10:59. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Syafruddin D, Hidayati A, Asih P, Hawley W, Sukowati S, Lobo N. Detection of 1014 F kdr mutation in four major anopheline malaria vectors in Indonesia. Malar J. 2010;9:315. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guerrero F, Jamroz R, Kammlah D, Kunz S. Toxicological and molecular characterization of pyrethroid-resistant horn flies, Haematobia irritans: identification of kdr and super-kdr point mutations. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;27:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hii J, Smith T, Mai A, Ibam E, Alpers M. Comparison between anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) caught using different methods in a malaria endemic area of Papua New Guinea. Bull Entomol Res. 2000;90:211–219. doi: 10.1017/s000748530000033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Belkin J. The Mosquitoes of the South Pacific (Diptera: Culicidae) Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henry-Halldin CN, Reimer L, Thomsen EK, Koimbu G, Zimmerman AM, Keven JB, Dagoro H, Hetzel M, Mueller I, Siba P, Zimmerman P. High throughput multiplex assay for species identification of Papua New Guinea malaria vectors: members of the Anopheles punctulatus (Diptera: Culicidae) species group. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:166–173. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martinez-Torres D, Chandre F, Williamson MS, Darriet F, Berge JB, Devonshire AL, Guillet P, Pasteur N, Pauron D. Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol Biol. 1998;7:179–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1998.72062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drummond AJ, Ashton B, Cheung M, Heled J, Kearse M, Moir R, Stones-Havas S, Thierer T, Wilson A. Geneious Pro v 5.0. 2009. http://www.geneious.com Available at. Accessed March 15, 2011.

- 62.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McNamara DT, Kasehagen LJ, Grimberg BT, Cole-Tobian J, Collins WE, Zimmerman PA. Diagnosing infection levels of four human malaria parasite species by a polymerase chain reaction/ligase detection reaction fluorescent microsphere-based assay. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:413–421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beebe NW, Cooper RD, Foley DH, Ellis JT. Populations of the south-west Pacific malaria vector Anopheles farauti s.s. revealed by ribosomal DNA transcribed spacer polymorphisms. Heredity. 2000;84:244–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beebe NW, Cooper RD, Morrison DA, Ellis JT. A phylogenetic study of the Anopheles punctulatus group of malaria vectors comparing rDNA sequence alignments derived from the mitochondrial and nuclear small ribosomal subunits. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2000;17:430–436. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2000.0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beebe NW, Ellis JT, Cooper RD, Saul A. DNA sequence analysis of the ribosomal DNA ITS2 region for the Anopheles punctulatus group of mosquitoes. Insect Mol Biol. 1999;8:381–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.83127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bower JE, Cooper RD, Beebe NW. Internal repetition and intraindividual variation in the rDNA ITS1 of the Anopheles punctulatus group (Diptera: Culicidae): multiple units and rates of turnover. J Mol Evol. 2009;68:66–79. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9188-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hasan AU, Suguri S, Fujimoto C, Itaki RL, Harada M, Kawabata M, Bugoro H, Albino B, Tsukahara T, Hombhanje F, Masta A. Phylogeography and dispersion pattern of Anopheles farauti senso stricto mosquitoes in Melanesia. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;46:792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davies TG, Field LM, Usherwood PN, Williamson MS. DDT, pyrethrins, pyrethroids and insect sodium channels. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:151–162. doi: 10.1080/15216540701352042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Keohavong P, Thilly W. Fidelity of DNA polymerases in DNA amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9253–9257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lundberg K, Shoemaker D, Adams M, Short J, Sorge J, Mathur E. High-fidelity amplification using a thermostable DNA polymerase isolated from Pyrococcus furiosus. Gene. 1991;108:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90480-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991;351:652–654. doi: 10.1038/351652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Diabate A, Baldet T, Chandre F, Dabire KR, Simard F, Ouedraogo JB, Guillet P, Hougard JM. First report of a kdr mutation in Anopheles arabiensis from Burkina Faso, West Africa. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2004;20:195–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Enayati AA, Vatandoost H, Ladonni H, Townson H, Hemingway J. Molecular evidence for a kdr-like pyrethroid resistance mechanism in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Med Vet Entomol. 2003;17:138–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2003.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Luleyap HU, Alptekin D, Kasap H, Kasap M. Detection of knockdown resistance mutations in Anopheles sacharovi (Diptera: Culicidae) and genetic distance with Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) using cDNA sequencing of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:870–874. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.6.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pinto J, Lynd A, Elissa N, Donnelly MJ, Costa C, Gentile G, Caccone A, do Rosario VE. Co-occurrence of East and West African kdr mutations suggests high levels of resistance to pyrethroid insecticides in Anopheles gambiae from Libreville, Gabon. Med Vet Entomol. 2006;20:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2006.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Verhaeghen K, Van Bortel W, Roelants P, Backeljau T, Coosemans M. Detection of the East and West African kdr mutation in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis from Uganda using a new assay based on FRET/Melt Curve analysis. Malar J. 2006;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Etang J, Fondjo E, Chandre F, Morlais I, Brengues C, Nwane P, Chouaibou M, Ndjemai H, Simard F. First report of knockdown mutations in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae from Cameroon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:795–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martinez-Torres D, Chevillon C, Brun-Barale A, Bergé JB, Pasteur N, Pauron D. Voltage-dependent Na+ channels in pyrethroid-resistant Culex pipiens L. mosquitoes. Pestic Sci. 1999;55:1012–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu Q, Liu H, Zhang L, Liu N. Resistance in the mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, and possible mechanisms for resistance. Pest Manag Sci. 2005;61:1096–1102. doi: 10.1002/ps.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williamson M, Martinez-Torres D, Hick C, Devonshire A. Identification of mutations in the housefly para-type sodium channel gene associated with knockdown resistance (kdr) to pyrethroid insecticides. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:51–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02173204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miyazaki M, Ohyama K, Dunlap DY, Matsumura F. Cloning and sequencing of the para-type sodium channel gene from susceptible and kdr-resistant German cockroaches (Blattella germanica) and house fly (Musca domestica) Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pridgeon JW, Appel AG, Moar WJ, Liu N. Variability of resistance mechanisms in pyrethroid resistant German cockroaches (Dictyoptera: Blattellidae) Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2002;73:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kelly GC, Hii J, Batarii W, Donald W, Hale E, Nausien J, Pontifex S, Vallely A, Tanner M, Clements A. Modern geographical reconnaissance of target populations in malaria elimination zones. Malar J. 2010;9:289. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hemingway J, Ranson H. Insecticide resistance in insect vectors of human disease. Annu Rev Entomol. 2000;45:371–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lawniczak M, Emrich S, Holloway A, Regier A, Olson M, White B, Redmond S, Fulton L, Appelbaum E, Godfrey J. Widespread divergence between incipient Anopheles gambiae species revealed by whole genome sequences. Science. 2010;330:512. doi: 10.1126/science.1195755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Neafsey D, Lawniczak M, Park D, Redmond S, Coulibaly M, Traore S, Sagnon N, Costantini C, Johnson C, Wiegand R. SNP genotyping defines complex gene-flow boundaries among African malaria vector mosquitoes. Science. 2010;330:514. doi: 10.1126/science.1193036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]