Abstract

American Indians are at greater risk for Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) than the general U.S. population. The epidemiology of RMSF among American Indians was examined by using Indian Health Service inpatient and outpatient records with an RMSF International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis. For 2001–2008, 958 American Indian patients with clinical diagnoses of RMSF were reported. The average annual RMSF incidence was 94.6 per 1,000,000 persons, with a significant increasing incidence trend from 24.2 in 2001 to 139.4 in 2008 (P = 0.006). Most (89%) RMSF hospital visits occurred in the Southern Plains and Southwest regions, where the average annual incidence rates were 277.2 and 49.4, respectively. Only the Southwest region had a significant increasing incidence trend (P = 0.005), likely linked to the emergence of brown dog ticks as an RMSF vector in eastern Arizona. It is important to continue monitoring RMSF infection to inform public health interventions that target RMSF reduction in high-risk populations.

Introduction

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a tick-borne rickettsial disease caused by infection with Rickettsia rickettsii that affects humans throughout much of the United States.1–3 Patients with RMSF can have a number of potentially severe outcomes including respiratory distress, renal failure, neurologic manifestations and death.1,2,4–6 National surveillance in the United States indicates that the average annual incidence of RMSF increased from 1.7 cases per million in 2001 to 7.0 in 2007; the highest incidence occurred in the West North Central, South Atlantic, East and West South Central census regions.7

The American Indian population has a greater risk for RMSF compared with other race groups, both in terms of incidence and case-fatality rates.8–13 Although national incidence of RMSF has increased since 2000, the rate increase observed among American Indians appears higher than that observed for other race groups.9 In some cases, this finding is linked to emergence of disease in new areas, such as that which occurred in 2003 when a new vector for RMSF, the brown dog tick, was identified as the source of an emerging focus of RMSF among American Indians in eastern Arizona.14 However, disparities in RMSF incidence also appear to be present in American Indian populations outside the Southwest.8,10 Past studies examining clinical diagnoses based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes among hospitalized patients have suggested most RMSF-associated hospital visits among American Indians occurred in the Oklahoma or Southern Plains region, and that American Indian children 1–4 years of age had the highest rate of hospitalization.8,10

The present study describes current epidemiology of RMSF among American Indians treated as inpatients and/or outpatients. Earlier studies examining RMSF among American Indians used Indian Health Service (IHS) inpatient data, which does not capture the large number of RMSF cases treated on an outpatient basis, or data from passive surveillance in the National Notifiable Disease System and individual RMSF case report form surveillance data, which is presumed to underestimate incidence and may be biased toward cases with more severe case outcomes and aggressive pursuit of diagnostic testing.7,9–12

In contrast to previous studies, the present study uses IHS inpatient and outpatient visit records for patients with an RMSF ICD-9-CM diagnosis to describe RMSF among American Indians. Although there are limitations to using clinical diagnoses for RMSF surveillance because of possible diagnostic miscoding and lack of laboratory verification, it is important to describe the epidemiology of RMSF among American Indians, a population known to be at increased risk for tick-borne infection.8,9 The IHS is the only source of data that has collected direct and contract health service visits for American Indians by using the IHS health care system; national morbidity data do not include visits at IHS health care facilities15,16 and the IHS data is often the only source of health care data for many rural American Indians.17,18 The IHS inpatient and outpatient data are also particularly useful for analysis of the trends of RMSF-diagnosed hospitalizations and outpatient visits reported among American Indians. Furthermore, race for American Indians is highly misclassified in national mortality and morbidity data, and studies have shown that rates for several public health outcomes have been underestimated in American Indian populations because of racial misclassification on medical records, in documents, and in data registering systems.19–22 In the present study, the incidence and trend of RMSF among American Indians during 2001–2008 are analyzed and described.

Methods

Retrospective analysis was performed on inpatient (hospitalization) and outpatient visit records for American Indian patients obtained from the IHS National Patient Information Reporting System for the calendar years 2001 through 2008.23,24 The National Patient Information Reporting System data includes approximately 100% of American Indian/Alaska Native inpatient and outpatient visits reported from IHS- and tribally-operated facilities and from community hospitals and clinics, which are contracted with IHS or tribes to provide health care services to federally-recognized eligible American Indian/Alaska Natives in the United States.23,24 Approximately 1.6 million American Indian/Alaska Natives are eligible for IHS-funded medical health care.25

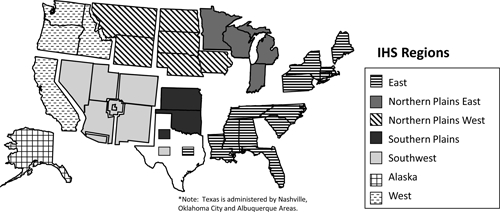

The IHS is comprised of 12 regional administrative units (area offices), which are further grouped into seven geographic regions: Alaska, East (Nashville area), Northern Plains East (Bemidji area), Northern Plains West (Aberdeen and Billings areas), Southern Plains (Oklahoma area), Southwest (Albuquerque, Navajo, Phoenix, and Tucson areas), and West (California and Portland areas; Figure 1).25 For this study, the IHS California and Portland administrative areas were excluded from the inpatient analysis because neither had IHS- or tribally-operated hospitals. In addition, the California area does not report contract health service inpatient data by diagnosis, and the Portland area has limited contract health service funds for inpatient care.25,26 The Alaska region was also excluded from the analysis because no cases of RMSF have been reported in Alaska by national surveillance.7 For this reason, American Indian/Alaska Natives will be referred to as American Indians unless otherwise noted. Furthermore, because of the small number of RMSF patients observed in the East, Northern Plains, and West regions, these regions were combined into an Other region category.

Figure 1.

Indian Health Service regions map, United States.

Hospitalization and outpatient visit records associated with RMSF were selected using the ICD-9-CM27 code of 082.0 (tick-borne rickettsioses: RMSF) listed as any one of the 15 diagnoses on the IHS inpatient or outpatient visit record. An RMSF patient was defined as an individual indicated by a healthcare provider as having RMSF based on the inclusion of the RMSF code listed as a diagnosis. However, patients could not be further evaluated to determine if they met the criteria for a confirmed or probable RMSF case based on national notifiable disease case definitions for RMSF.28

Records for inpatient and outpatient visits were linked by patient using IHS-encrypted unique identifiers (no personal identifiers were provided), enabling estimation of patient-based RMSF annual incidence. A patient's first inpatient or outpatient visit with RMSF as a diagnosis for each year during the study period was used to examine the annual incidence of RMSF to exclude the potential bias of repeat provider visits for the same episode and to enable comparison to national surveillance reports of annual incidence. The primary unit of analysis in the present study is a patient, unless otherwise indicated. The population denominator used for RMSF incidence rates was determined using the annual IHS 2001–2008 fiscal year user populations (excluding the user population for Alaska); the user population represents all registered American Indian/Alaska Natives who received IHS-funded health care services at least once within the preceding 3 years.29

All incidence rates were expressed as the number of RMSF cases per 1,000,000 American Indians from the corresponding group using the IHS/tribal system. Patients' records were examined by age group, sex, month of visit (inpatient discharge date or outpatient service date), and IHS region. Average annual incidences for a second time period (2001–2007) were also calculated to enable direct comparison to previously published national surveillance incidence reports.7 Incidence rates by sex were compared using Poisson regression to determine rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals.30 Tests for trend were performed using linear regression.30 Age was compared by sex using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.31 Statistical significance was considered at P = 0.05.

Results

Overall IHS.

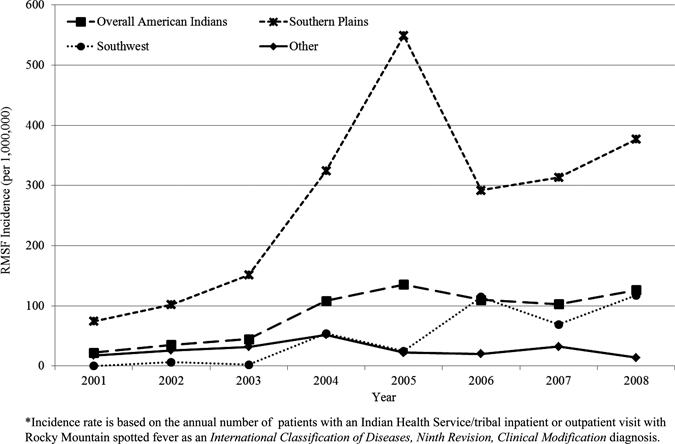

During 2001–2008, 958 American Indian patients were reported with RMSF listed as a diagnosis on their hospital or outpatient records (Table 1). Of these patients, 856 (89.4%) had only outpatient visits, 50 (5.2%) had only inpatient hospitalizations, and 52 (5.4%) had inpatient and outpatient visits. The proportion of these patients who were hospitalized decreased significantly during 2001–2008 (24.1% to 7.6%; P = 0.005). Overall, the RMSF average annual incidence rate for the study period was 94.6 per 1,000,000 persons (Table 1); the average annual incidence was 87.9 for 2001–2007. There was a significant increasing trend of overall RMSF annual incidence from 24.2 in 2001 to 139.4 in 2008 (P = 0.006; Figure 2). Annual incidence of RMSF was highest in the Southern Plains (277.2), East (104.6), and Southwest regions (49.4; Table 1). The Southwest and Southern Plains regions accounted for the most (89%) RMSF patients; the number of patients in the other regions was small (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Rocky Mountain spotted fever patients and average annual incidence rates among American Indians, 2001–2008, United States*

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Average annual incidence rate (per 1,000,000) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 958 (100) | 94.6 |

| Sex | ||

| M | 531 (55) | 110.1 |

| F | 427 (45) | 80.5 |

| Age groups (years) | ||

| 0–4 | 88 (9) | 91.5 |

| 5–9 | 120 (13) | 119.5 |

| 10–19 | 115 (12) | 55.5 |

| 20–29 | 128 (13) | 73.7 |

| 30–39 | 132 (14) | 99.4 |

| 40–49 | 141 (15) | 114.1 |

| 50–59 | 120 (13) | 142.0 |

| 60–69 | 74 (8) | 145.2 |

| ≥ 70 | 40 (4) | 93.8 |

| Region | ||

| East | 33 (3) | 104.6 |

| Northern Plains† | 60 (6) | 27.1 |

| Southern Plains | 663 (69) | 277.2 |

| Southwest | 191 (20) | 49.4 |

| West | 11 (1) | 8.3 |

Incidence rate is based on the annual number of patients with an Indian Health Service/tribal inpatient or outpatient visit with Rocky Mountain spotted fever as an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis.

Average annual incidence was 4.1 per 1,000,000 for Northern Plains East and 38.3 per 1,000,000 for Northern Plains West (number of cases could not be reported because of small numbers).

Figure 2.

Annual incidence rates for Rocky Mountain spotted fever among American Indians by region, 2001–2008, United States.

Southern Plains Region.

Regionally, the highest average annual incidence rate for 2001–2008 occurred in the Southern Plains region, which represents the IHS Oklahoma Area (Table 1 and Figure 1) and includes American Indians residing in the states of Oklahoma, Kansas, and part of Texas. This region also had the most RMSF patients (69.2%; Table 1). During the study period, the lowest incidence rate occurred in 2001 (74.6) and the highest occurred in 2005 (549.2; Figure 2). Of the 663 RMSF patients, 3.5% had inpatient visits only, 92.5% had outpatient visits only, and 4.2% had inpatient and outpatient RMSF-associated visits. The RMSF average annual incidence for males was higher than that for females (rate ratio = 1.5, 95% confidence interval = 1.3–1.8). The highest age-specific average annual incidence rates occurred in persons 50–59 years of age, followed by persons 60–69 years of age (453.4 and 389.1, respectively; Table 2). Only persons 50–59 years of age had a significant increasing annual rate trend (P = 0.01). The median age of RMSF patients was 36 years (37 and 35 years for males and females, respectively).

Table 2.

Number of Rocky Mountain spotted fever patients and average annual incidence rates among American Indians by region, 2001–2008, United States*

| Characteristic | Southern Plains region | Southwest region | Other regions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Average annual incidence rate (per 1,000,000) | No. (%) | Average annual incidence rate (per 1,000,000) | No. (%) | Average annual incidence rate (per 1,000,000) | |

| Total | 663 (100) | 277.2 | 191 (100) | 49.4 | 104 (100) | 26.9 |

| Sex | ||||||

| M | 384 (58) | 341.2 | 99 (52) | 54.2 | 48 (46) | 25.7 |

| F | 279 (42) | 220.3 | 92 (48) | 45.1 | 56 (54) | 28.1 |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||

| 0–4 | 29 (4) | 140.5 | 48 (25) | 124.0 | 11 (11) | 29.8 |

| 5–9 | 76 (11) | 327.5 | 36 (19) | 93.5 | 8 (8) | 20.7 |

| 10–19 | 77 (12) | 168.2 | 25 (13) | 30.9 | 13 (13) | 16.1 |

| 20–29 | 90 (14) | 211.5 | 21 (11) | 31.6 | 17 (16) | 26.3 |

| 30–39 | 98 (15) | 315.8 | 16 (8) | 30.9 | 18 (17) | 36.0 |

| 40–49 | 109 (16) | 377.3 | 18 (9) | 38.7 | 14 (13) | 29.1 |

| 50–59 | 96 (15) | 453.4 | 15 (8) | 49.5 | 9 (9) | 27.3 |

| 60–69 | 54 (8) | 389.1 | 10 (5) | 56.3 | 10 (10) | 51.7 |

| ≥ 70 | 34 (5) | 282.3 | 2 (1) | 12.7 | 4 (4) | 26.8 |

Incidence rate is based on the annual number of patients with an Indian Health Service/tribal inpatient or outpatient visit with Rocky Mountain spotted fever as an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis.

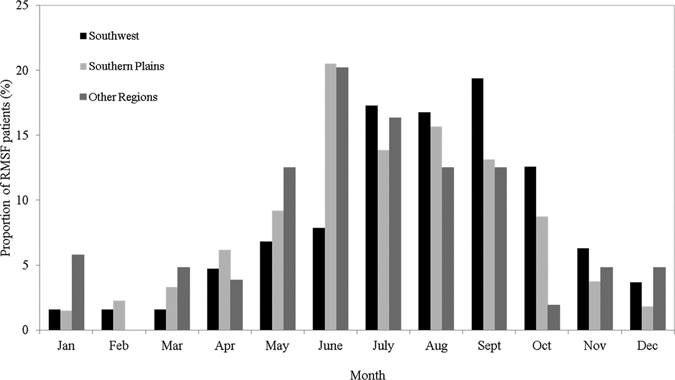

Seasonally, the largest proportion of RMSF inpatient or outpatient visits in this region occurred in the months of June through September (63%; Figure 3). The most frequently listed accompanying diagnoses with the RMSF diagnosis included unspecified essential hypertension (4.6%), Lyme disease (2.5%), and headache (1.9%). The median number of health care facility visits per patient during the study period (including all inpatient and outpatient visits) was one (quartiles 1 and 2). The annual average proportion of RMSF patients that were hospitalized in this region was 11.8%; the proportion was highest in persons 1–4 years of age (21%). The proportion of patients hospitalized significantly decreased from 2001 (23.8%) to 2008 (2.5%; P = 0.002).

Figure 3.

Seasonality of Rocky Mountain spotted fever hospital visits among American Indians by region, 2001–2008, United States.

Southwest Region.

The Southwest region, which includes American Indians seeking health care in the states of Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico (Figure 1), contributed the second highest proportion and number of RMSF patients (19.9% and 191 patients; Table 1) among the IHS regions. This region was the only region with a significant increasing trend of incidence, from no patients reported in 2001 to an average annual incidence of 117.8 in 2008 (P = 0.005; Figure 2). A significant increasing trend of incidence was seen in all age groups except for persons 40–49 and ≥ 60 years of age. The highest incidence rates occurred in persons 1–4 years of age, followed by persons 5–9 years of age (Table 2). The median age of RMSF patients in this region was 12 years; the median ages of males and females were significantly different from each other (11 and 22 years, respectively; P = 0.002).

Seasonality in the Southwest varied slightly from other regions; most RMSF patient visits occurred in July though October (65.9%; Figure 3). The most frequently listed accompanying diagnoses with the RMSF diagnosis included gangrene (3.4%), fever (2.9%), and rash or other non-specific skin eruption (2.9%). The median number of RMSF-associated hospital visits per patient in this region including all inpatient and outpatient visits was one (quartiles 1 and 2). The average proportion of patients hospitalized for RMSF in the Southwest was 26%, and high proportions of hospitalizations occurred in persons 1–4 (31%), 20–29 (29%), 60–69 (30%) and ≥ 70 (50%) years of age. During the study period, there was no significant increase or decrease in the proportion of patients hospitalized.

Other Regions.

In the other IHS regions (East, Northern Plains, and West regions; Figure 1), there were 104 RMSF American Indian patients with an average annual incidence of 26.9. Of these regions, the East had the highest incidence (104.6) but because of the small number of cases in this region (n = 33), the data could not be analyzed in depth (Table 1). In these regions combined, the RMSF annual incidence for females (28.1) was slightly higher than for males (25.7), but these rates were not significantly different from each other. The highest annual average incidence rate occurred in persons 60–69 years of age, followed by persons 30–39 years of age (Table 2). The median age among RMSF patients was 31 years (31.5 and 31.0 years among males and females, respectively).

Most RMSF visits among American Indians in these other regions combined occurred in June through September (61.5%; Figure 3). The most frequently listed accompanying diagnoses included essential hypertension (7.2%), depressive disorder (2.8%), myalgia and myositis, unspecified (2.8%), and headache (2.8%). The median number of inpatient and outpatient visits per person during the study period was one (quartiles 1 and 2). Of patients with an RMSF-associated visit, 12.5% were hospitalized. The proportion that was hospitalized was highest in persons 60–69 years of age (23.1%). Over the study period, there was no significant increase or decrease in the proportion of patients hospitalized.

Discussion

The present study of American Indians with RMSF-associated hospital and outpatient visits adds current and important information to our knowledge of the occurrence of RMSF among American Indian populations, which to date has been based exclusively on inpatient records or national surveillance data, both of which substantially underestimate RMSF disease incidence among American Indians.9,10 The present study demonstrates that there is a significant increasing trend of RMSF incidence during 2001–2008, which supports findings from other studies that have demonstrated that RMSF has increased among American Indians during this decade.7,9 A similar increasing pattern of RMSF was also observed for the overall U.S. population by using national surveillance; these trends have been attributed in part to a heightened physician awareness of RMSF after recent publications on the topic, and by a changing RMSF case definition and new diagnostic tests of varying sensitivity and specificity.7,9

In this study, the evaluation of IHS outpatient records in addition to inpatient records permitted insight into RMSF treatment trends among the American Indian population that past studies have not provided. During 2001–2008, approximately 90% of all patients with a clinical diagnosis of RMSF were treated as outpatients, which is a higher percentage than is suggested by current national surveillance systems for the general U.S. population. This finding suggests that IHS providers are considering suspected RMSF diagnoses more frequently than national surveillance data. In fact, national surveillance systems may be biased toward the capture of more severe outcomes for RMSF because persons with mild illness or who respond quickly to outpatient treatment may not return for laboratory testing necessary to meet the RMSF confirmed or probable case definition for capture under national reporting guidelines. The inclusion of outpatient data also enables improved assessment of RMSF incidence among American Indians.

The use of inpatient and outpatient records with an ICD-9-CM code of RMSF showed that the estimated average annual incidence for American Indian patients with RMSF in 2001–2007 (87.9 per 1,000,000) is approximately five times the incidence for American Indians reported to the passive national surveillance system (16.8 per 1,000,000) for the same time period.7 Although these patients may not all have had appropriate diagnostic tests conducted to meet the required RMSF case definition for reporting under national notifiable disease guidelines, and this report may include some suspected RMSF cases for which infection is eventually ruled out, it seems clear that the incidence of disease among American Indians is likely underestimated by national surveillance systems.

The findings from the present study also support past studies that have suggested that American Indians have a higher average annual incidence of RMSF compared with the overall U.S. population.7–9 Possible reasons for this include the fact that RMSF is common in rural locations and American Indians within the IHS system typically live in rural areas and may participate in different recreational, social, or community activities that more frequently expose them to ticks compared with other race groups.8,32 Additionally, American Indians may be at overall higher risk for infectious diseases than other populations because of increased exposure, susceptibility, or underlying co-morbidities that increase risk for infection after exposure.33,34

This analysis also highlights several important epidemiologic differences in cases of RMSF among IHS regions. The Southern Plains had a higher annual average incidence rate than the Southwest region. However, the average annual rate in the Southwest could be the result of the fact that RMSF did not emerge as an important public health problem in Arizona (which is located in the Southwest region) until 2003, two years into our study period.14 Cases of RMSF in the Southern Plains and other regions tended to occur in older age groups, with the highest age-specific incidence among persons 50–59 and 60–69 years of age. In contrast, RMSF cases from the Southwest region were found more often in younger persons (median age = 12 years), and persons 1–4 and 5–9 years of age showed the highest incidence rates. In the Southwest region RMSF patients were also more likely to be hospitalized compared with the patients in the Southern Plains and other regions. The Southern Plains region also was the only region to show a trend toward decreasing hospitalization rates during the study period. In the Southern Plains and other regions, most RMSF health care facility visits occurred during June–September. In the Southwest region, there was a later seasonal shift; most visits occurred during July–October.

The high numbers of American Indian patients reported with RMSF in the Southern Plains region correspond with previous national surveillance reports stating that Oklahoma has one of the highest numbers of RMSF cases in the United States.7 In addition, American Indians in Oklahoma have historically had a higher rate of RMSF than the overall Oklahoma population. This finding could be caused by differences in frequency of exposure to ticks; ticks infected with R. rickettsii may be highly concentrated in certain geographic areas and thus contribute to high rates of transmission in these areas.8 National surveillance for RMSF also suggests high numbers and rates of RMSF cases in North Carolina and Tennessee.7 Although our analysis did not show a corresponding high number of RMSF cases from the East region, even these few cases resulted in a fairly high incidence. The small number of American Indians living in this large and geographically diverse region makes it difficult to assess this finding more closely.

The high RMSF incidence rate and significant increasing trend in incidence in the Southwest region during the study period is likely caused by emergence of the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus), which was shown to be a new vector for RMSF in eastern Arizona and for which cases began to be recognized as early as 2003.14 Despite the higher numbers of RMSF cases in the Southwest, RMSF incidence in this region is possibly diluted because the outbreak is focal (i.e., affecting only a few tribes), while the Southwest IHS service region covers a large geographic area and includes a large American Indian population.14,25 The seasonal variation in RMSF cases from this region may be caused by a different disease ecology in the Southwest.14,35,36 Specifically, Rh. sanguineus, the tick responsible for transmission in this region, may have a different cycle of peak tick activity. Recent studies have shown that transmission of rickettsioses by Rh. sanguineus is influenced by changes in climate; it has been shown that warmer weather increases the aggressiveness of Rh. sanguineus, thus leading to more human attacks.37,38 These findings have raised the concern that changing climates could result in more emerging pathogens transmitted by the Rh. sanguineus in the future.38 Furthermore, the unique predilection for pediatric cases in the Southwest region may reflect the close interaction of dogs and children in the peridomestic environment, and appears different from the epidemiology observed in the Southern Plains and other regions, and in the general U.S. population, in which older age groups have higher rates of RMSF.7

There are some important limitations to the use of hospital discharge and outpatient visit data based on ICD-9-CM-coded diagnoses. Many studies have illustrated the inaccuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for surveillance because of coding errors, physician errors, absence of laboratory verification, artificially abbreviated diagnosis code lists, and codes that do not correspond directly to clinical syndromes.39–41 However, studies have also been conducted to validate the use of ICD-9-CM diagnoses in the IHS health care system and have showed sensitivity and specificity for disease identification greater than 90%.42,43 In general, all current surveillance systems for RMSF are limited because complicated serologic testing is required to meet the confirmed RMSF case definition; interpretation of laboratory findings for cases in which there are antibodies present from previous exposures or cross-reactive antibodies may result in an incorrect designation of RMSF.7,44

Even with the national surveillance system, data for RMSF captured through the National Electronic Telecommunications System for Surveillance, which was designed to capture cases based on a laboratory and clinical diagnosis, cannot be reviewed for accuracy of case designation, and no details on the laboratory diagnosis are available. In 2001–2005, only 12.5% of American Indian cases met the confirmed RMSF case definition.9 Similarly, ICD-9-CM diagnoses for inpatient and outpatient visits are based on clinical diagnosis, and may not represent true RMSF cases. A previous medical chart review on RMSF hospital discharge records of American Indian hospitalizations in Oklahoma showed that nearly 45% of American Indian patients had a reported ICD-9-CM code for RMSF with no serum tested or only a single serum sample submitted for testing.8 Furthermore, other tick-borne diseases including R. parkeri infection and ehrlichiosis/anaplasmosis, have similar presenting symptoms, may occur in the same areas, and are clinically indistinguishable from RMSF. A study in North Carolina, a state that traditionally reports RMSF and ehrlichiosis/anaplasmosis, found that febrile patients with a history of tick bites were as likely to show serologic evidence of exposure to ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis agents as to RMSF.45 In the present study, a small percentage of cases had Lyme disease (1.9%) and ehrlichiosis (0.2%) reported as accompanying diagnoses to the RMSF diagnoses, which suggests the lack of laboratory verification of the RMSF diagnosis. In addition, diagnostic criteria may vary by region and physician. Thus, in areas in which RMSF and ehrlichiosis/anaplasmosis are endemic, without laboratory diagnostics, other rickettsioses may be reported as RMSF. Efforts to identify the etiologic cause of disease with laboratory testing could help to properly classify these cases.

Other limitations of the present study include the fact that the incidence rates by region were calculated on the basis of residence rather than location of occurrence. Location of occurrence cannot be determined from the available data and location of residence was chosen rather than location of hospital or outpatient encounter for the purposes of incidence calculations and comparable user population denominators; this may bias regional results if persons were seen at a facility outside their region of residence and may account for RMSF cases occurring out of season. In addition, the American Indian/Alaska Native user population is an estimate of the number of American Indian/Alaska Natives who are eligible to use the IHS healthcare system and may not include all American Indian/Alaska Natives who are eligible for care at IHS/tribal facilities. Finally, the American Indians in this study may not be representative of all American Indians in the United States.

The findings from this study raise concerns about the high and increasing rates of RMSF among American Indians, and underreporting in the national RMSF passive surveillance system. Furthermore, the unique RMSF disease patterns in the Southwest region, including the higher number of pediatric cases and the increasing incidence trend in this region, highlight the need for further assessment of RMSF exposure risks caused by the emergent tick vector in this area. The suggestion of seasonal variation on the basis of region may also be an important detail to include in educational messages because RMSF cases were reported in later months, especially in the Southwest region. Physicians in the Southwest region need to be aware that RMSF cases may occur later in the season, and should plan to treat and test suspect patients accordingly. The finding that age-related risks vary by region is also important in terms of planning public health prevention messages. For example, educational messages targeted to school age children and parents regarding risks around their homes and the importance of treating homes and dogs may be important in the Southwest region, while general prevention messages for personal repellent use and behavioral modifications may be more appropriate in the Southern Plains region. It is important to continue to explore and monitor the epidemiology and trends of RMSF cases among American Indians to assess the efforts of public health interventions and to provide informative data for future public health policies and interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Barbara Strzelczyk (IHS) for technical assistance and the staff at the participating IHS/tribal and contract care health care facilities.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Indian Health Service.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Arianne M. Folkema and Robert C. Holman, Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, E-mails: afolkema@cdc.gov and rholman@cdc.gov. Jennifer McQuiston, Division of Vectorborne Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, E-mail: jmcquiston@cdc.gov. James E. Cheek, Division of Epidemiology and Disease Prevention Office of Public Health Support Indian Health Service Headquarters, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Albuquerque, NM, E-mail: james.cheek@ihs.gov

References

- 1.Helmick CG, Bernard KW, D'Angelo LJ. Rocky Mountain spotted fever: clinical, laboratory, and epidemiological features of 262 cases. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:480–488. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dantas-Torres F. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:724–732. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70261-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rucker WC. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Public Health Rep. 1912;27:1465–1482. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohue JF. Lower respiratory tract involvement in Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker DH, Mattern WD. Acute renal failure in Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Arch Intern Med. 1979;139:443–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleck TP. Central nervous system involvement in Rickettsial diseases. Neurol Clin. 1999;17:801–812. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Openshaw JJ, Swerdlow DL, Krebs JW, Holman RC, Mandel E, Harvey A, Haberling D, Massung RF, McQuiston JH. Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States, 2000–2007: interpreting contemporary increases in incidence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:174–182. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McQuiston JH, Holman RC, Groom AV, Kaufman SF, Cheek JE, Childs JE. Incidence of Rocky Mountain spotted fever among American Indians in Oklahoma. Public Health Rep. 2000;115:469–475. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.5.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holman RC, McQuiston JH, Haberling DL, Cheek JE. Increasing incidence of Rocky Mountain spotted fever among the American Indian population in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:601–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demma LJ, Holman RC, Mikosz CA, Curns AT, Swerdlow DL, Paisano EL, Cheek JE. Rocky Mountain spotted fever hospitalizations among American Indians. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalton MJ, Clarke MJ, Holman RC, Krebs JW, Fishbein DB, Olson JG, Childs JE. National surveillance for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, 1981–1992: epidemiologic summary and evaluation of risk factors for fatal outcome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:405–413. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman AS, Bakken JS, Folk SM, Paddock CD, Bloch KC, Krusell A, Sexton DJ, Buckingham SC, Marshall GS, Storch GA, Dasch GA, McQuiston JH, Swerdlow DL, Dumler SJ, Nicholson WL, Walker DH, Eremeeva ME, Ohl CA. Diagnosis and management of tickborne rickettsial diseases: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrlichioses, and anaplasmosis–United States: a practical guide for physicians and other health-care and public health professionals. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treadwell TA, Holman RC, Clarke MJ, Krebs JW, Paddock CD, Childs JE. Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States, 1993–1996. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:21–26. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.63.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demma LJ, Traeger MS, Nicholson WL, Paddock CD, Blau DM, Eremeeva ME, Dasch GA, Levin ML, Singleton J, Jr, Zaki SR, Cheek JE, Swerdlow DL, McQuiston JH. Rocky Mountain spotted fever from an unexpected tick vector in Arizona. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:587–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healthcare Cost and Utlization Project (HCUP) HCUP NIS Database Documentation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdbdocumentation.jsp Available at. Accessed August 18, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics . National Hospital Discharge Survey. Hyattsville, MD: 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhds.htm Available at. Accessed August 18, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldwin LM, Hollow WB, Casey S, Hart LG, Larson EH, Moore K, Lewis E, Andrilla CH, Grossman DC. Access to specialty health care for rural American Indians in two states. J Rural Health. 2008;24:269–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham PJ, Cornelius LJ. Access to ambulatory care for American Indians and Alaska Natives; the relative importance of personal and community resources. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:393–407. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0072-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control Classification of American Indian race on birth and infant death certificates–California and Montana. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;42:220–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein M, Moreno R, Bacchetti P. The underreporting of deaths of American Indian children in California, 1979 through 1993. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1363–1366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.8.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahn RA, Mulinare J, Teutsch SM. Inconsistencies in coding of race and ethnicity between birth and death in US infants. A new look at infant mortality, 1983 through 1985. JAMA. 1992;267:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thoroughman DA, Frederickson D, Cameron HD, Shelby LK, Cheek JE. Racial misclassification of American Indians in Oklahoma State surveillance data for sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:1137–1141. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.12.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Indian Health Service . Direct/CHS Inpatient data: All-diseases, Fiscal years 2001–2009, National Patient Information Reporting System. Albuquerque, NM: Indian Health Service; 2010. http://www.ihs.gov/NDW/ Available at. Accessed February 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Indian Health Service . Outpatient Visit Data: All-diseases, Fiscal years 2001–2009. National Patient Information Reporting System. Rockville, MD: Indian Health Service; 2010. http://www.ihs.gov/NDW/ Available at. Accessed February 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Indian Health Service . Regional Differences in Indian Health, 2002–2003. Rockville, MD: Indian Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman SF. Utilization of IHS and Tribal Direct and Contract General Hospitals, FY 1996 and US Non-Federal Short-Stay Hospitals, 1996. Rockville, MD: Indian Health Service; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Public Health Service and Health Care Financing Administration . International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [CD-ROM] Sixth edition. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) (Rickettsia rickettsii) 2008 Case Definition. 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/ncphi/disss/nndss/casedef/rocky2008.htm Available at. Accessed December 1, 2010.

- 29.Indian Health Service . Trends in Indian Health 2002–2003. Rockville, MD: Indian Health Service; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller KE, Nizam A. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods. Third edition. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehmann E. Nonparametrics: Statistical Methods Based on Ranks. San Francisco, CA: Holden-Day Inc; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen LF, Sexton DJ. What's new in Rocky Mountain spotted fever? Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22:415–432. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holman RC, Curns AT, Kaufman SF, Cheek JE, Pinner RW, Schonberger LB. Trends in infectious disease hospitalizations among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:425–431. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holman RC, Curns AT, Cheek JE, Singleton RJ, Anderson LJ, Pinner RW. Infectious disease hospitalizations among American Indian and Alaska native infants. Pediatrics. 2003;111:E176–E182. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.e176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demma LJ, Traeger M, Blau D, Gordon R, Johnson B, Dickson J, Ethelbah R, Piontkowski S, Levy C, Nicholson WL, Duncan C, Heath K, Cheek J, Swerdlow DL, McQuiston JH. Serologic evidence for exposure to Rickettsia rickettsii in eastern Arizona and recent emergence of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in this region. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2006;6:423–429. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.6.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McQuiston JH, Guerra MA, Watts MR, Lawaczeck E, Levy C, Nicholson WL, Adjemian J, Swerdlow DL. Evidence of exposure to spotted fever group rickettsiae among Arizona dogs outside a previously documented outbreak area. Zoonoses Public Health. 2011;58:85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beugnet F, Kolasinski M, Michelangeli PA, Vienne J, Loukos H. Mathematical modelling of the impact of climatic conditions in France on Rhipicephalus sanguineus tick activity and density since 1960. Geospat Health. 2011;5:255–263. doi: 10.4081/gh.2011.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parola P, Socolovschi C, Jeanjean L, Bitam I, Fournier PE, Sotto A, Labauge P, Raoult D. Warmer weather linked to tick attack and emergence of severe rickettsioses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jhung MA, Banerjee SN. Administrative coding data and health care-associated infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:949–955. doi: 10.1086/605086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schweizer ML, Eber MR, Laxminarayan R, Furuno JP, Popovich KJ, Hota B, Rubin MA, Perencevich EN. Validity of ICD-9-CM coding for identifying incident methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections: is MRSA infection coded as a chronic disease? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:148–154. doi: 10.1086/657936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White RH, Brickner LA, Scannell KA. ICD-9-CM codes poorly indentified venous thromboembolism during pregnancy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:985–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penman-Aguilar A, Tucker MJ, Groom AV, Reilley BA, Klepacki S, Cullen T, Gebremariam C, Redd JT. Validation of algorithm to identify American Indian/Alaska Native pregnant women at risk from pandemic H1N1 influenza. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:S46–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson C, Susan L, Lynch A, Saria R, Peterson D. Patients with diagnosed diabetes mellitus can be accurately identified in an Indian Health Service patient registration database. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:45–50. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50021-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sickbert-Bennett EE, Weber DJ, Poole C, MacDonald PD, Maillard JM. Utility of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for communicable disease surveillance. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1299–1305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carpenter CF, Gandhi TK, Kong LK, Corey GR, Chen SM, Walker DH, Dumler JS, Breitschwerdt E, Hegarty B, Sexton DJ. The incidence of ehrlichial and rickettsial infection in patients with unexplained fever and recent history of tick bite in central North Carolina. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:900–903. doi: 10.1086/314954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]