Abstract

Skeletal diseases have a major impact on the worldwide population and economy. Although several therapeutic agents and treatments are available for addressing bone diseases, they are not being fully utilized because of their uptake in non-targeted sites and related side effects. Active targeting with controlled delivery is an ideal approach for treatment of such diseases. Because bisphosphonates are known to have high affinity to bone and are being widely used in treatment of osteoporosis, they are well-suited for drug targeting to bone. In this study, a targeted delivery of therapeutic agent to resorption sites and wound healing sites of bone was explored. Towards this goal, bifunctional hydrazine-bisphosphonates (HBPs), with spacers of various lengths, were synthesized and studied for their enhanced affinity to bone. Crystal growth inhibition studies showed that these HBPs have high affinity to hydroxyapatite, and HBPs with shorter spacers bind stronger than alendronate to hydroxyapatite. The HBPs did not affect proliferation of MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts, did not induce apoptosis, and were not cytotoxic at the concentration range tested (10−6 - 10−4 M). Furthermore, drugs can be linked to the HBPs through a hydrazone linkage that is cleavable at the low pH of bone resorption and wound healing sites, leading to release of the drug. This was demonstrated using hydroxyapatite as a model material of bone and 4-nitrobenzaldehyde as a model drug. This study suggests that these HBPs could be used for targeted delivery of therapeutic agents to bone.

INTRODUCTION

Active targeting of therapeutic agents to bone reduces drug toxicity and improves drug bioavailability at the desired site.1 Bone tissue is characterized by constant remodeling, whereby it continuously undergoes formation and resorption; perturbations in bone remodeling are associated with several metabolic bone diseases, such as osteoporosis.2–4 Therefore, molecules that inhibit bone resorption or stimulate bone formation show drug activity against various skeletal disorders.5 Although a range of therapeutic agents is available to treat skeletal disorders,6 their clinical application is hampered by their uptake in non-targeted sites and the consequent undesired side effects.7

Several bisphosphonates (BPs) show anti-resorptive properties and are being prescribed in the treatment of skeletal diseases.6,8,9 BPs are stable analogues of naturally occurring pyrophosphate and have high affinity to bone and hydroxyapatite (HA).10 Besides the two phosphonate groups, BPs have two other substituents (R1 and R2) on their geminal carbon. BPs with a hydroxyl or an amine group at R1 facilitate tridentate binding to bone and HA, and show an increased affinity to these materials.11,12 The overall nature of the R2 substituent also contributes toward enhancing the bone-seeking ability and pharmacological properties of BPs.10,13

Recently, a number of drug targeting and drug delivery strategies have been reported using a range of delivery vehicles, such as polymer scaffolds, liposomes, dendrimers, micelles, hydrogels, peptides, and antibodies.14–21 However, drug targeting to bone sites requires molecules that have high affinity to bone. Besides BPs, other molecules, such as D-aspartic acid octapeptide,20,21 polymalonic acid,22 and tetracycline23,24 show affinity to bone. BPs have advantage over other molecules because their affinity can be tuned by changing their R1 and R2 substituents. Moreover, in addition to being prescribed as drugs, BPs are also being studied for drug targeting, and drug delivery to bone,25–30 including the administration of radiopharmaceuticals and imaging agents to bone for diagnostic applications.31–35 For the purpose of drug targeting to bone, various strategies of BP-drug conjugation have been investigated by us and others.29,35–38 Ideally, for targeted drug delivery to bone, BP-drug conjugates should have a stable linkage between the BP and drug molecule that can survive during systemic circulation of the conjugate following parenteral administration, and at the same time be labile at the bone surface to release the drug locally. Most of the strategies mentioned above employ agents that are conjugated to BPs through stable, non-cleavable linkages resulting in the administration of the complete conjugate to the treatment site.25,29,31–33,35 Current approaches that employ cleavable linkages are either too labile to ensure delivery of the drug to the desired site,26,27 or show limited release providing inadequate availability of drug for action.26 A strategy that involves labile conjugation to one of the phosphonate groups of BP could compromise the affinity of the corresponding BP-drug conjugate toward bone, because it is through the phosphonate groups that BPs bind to the mineral matrix.27

Herein, we report a novel strategy for targeted delivery of therapeutic agents to sites of low pH, such as bone resorption lacunae and areas of wound healing, through their conjugation to enhanced affinity bifunctional BPs with a pH-triggered cleavable linkage. In particular, we have synthesized seven novel hydrazine-bisphosphonates (HBPs) (2–8), which have a hydroxyl group as R1, while R2 contains a hydrazine functionality attached through spacers of various length and hydrophobicity (Table 1). Furthermore, experiments were performed to explore the binding affinity, cytotoxicity, drug conjugation, and pH triggered drug release of HBPs.

Table 1.

Structure of alendronate (1) and hydrazine-bisphosphonates (HBPs) (2–8)

| Cpd | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | OH |

|

| 2 | OH |

|

| 3 | OH |

|

| 4 | OH |

|

| 5 | OH |

|

| 6 | OH |

|

| 7 | OH |

|

| 8 | OH |

|

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1 was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (CRL-2593; ATCC, Rockville, MD). Alpha minimum essential medium (αMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from GIBCO-Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The BCA protein assay kit was obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific (Rockford, IL). The cell proliferation reagent WST-1 was purchased from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). Ac-DEVD-AFC was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA). 4-Aminobutanoic acid, 6-aminohexanoic acid, 8-aminooctanoic acid, glycine, glycylglycine, glycylglycylglycine, methanesulfonic acid, phosphorous acid, phosphorous trichloride, and 2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenol (TFP) were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). N,N′-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), triethylamine (TEA), tri-BOC-hydrazinoacetic acid (TBHA), reagent grade hydroxyapatite powder, potassium hydroxide, sodium acetate, sodium chloride, sodium hydroxide, etoposide, tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris-HCl), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylamino]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate (EDTA), sodium fluoride (NaF), sodium orthovanadate, leupeptin hemisulfate salt, aprotinin bovine, phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, DL-dithiothreitol (DTT), glycerol, and Triton X-100 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Calcium chloride, hydrochloric acid, and potassium dihydrogen phosphate were obtained from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ). Acetonitrile, chloroform, dichloromethane, diethyl ether, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), hexane, and phosphoric acid were purchased from Mallinckrodt (Hazelwood, MO). The NMR solvents deuterium oxide and deuterated chloroform were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA).

Apparatus

1H NMR, 31P NMR, and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian INOVA 400 MHz spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA). Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry was performed on a ThermoFinnigan LCQ mass spectrometer (Waltham, MA). HA crystal growth experiments were performed using an Isotemp Refrigerated Circulator and pH meter (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). UV-vis spectra were obtained with an Agilent 8453 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Deionized water was produced using a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

Synthesis of (4-Amino-1-hydroxybutylidene)bisphosphonic Acid Monosodium Salt (1)

(4-Amino-1-hydroxybutylidene)bisphosphonic acid monosodium salt or monosodium alendronate (1) was synthesized in an inert atmosphere according to a previously reported procedure from 4-aminobutanoic acid (9)39,40 as outlined in Scheme 1. A 25-mL flask was fitted with an addition funnel and a reflux condenser. Ice-cold water was circulated through the condenser. The system was flushed with nitrogen and 4-aminobutyric acid (9) (4.0 g, 38.7 mmol), phosphorous acid (3.18 g, 38.7 mmol), and methanesulfonic acid (16 mL) were added to the flask. The mixture was heated for 5 min at 65 °C. PCl3 (9.0 mL, 85.3 mmol) was added over 20 min, and the mixture was stirred for 18 h at 65 °C. The solution was cooled to 25 °C and quenched into 0–5 °C water (40 mL) with vigorous stirring. The reaction flask was rinsed with an additional 16 mL of water, and the combined solution was refluxed for 5 h at 110 °C. The solution was cooled to 23 °C, and the pH was adjusted to 4–4.5 with 50% (v/v) NaOH. The resulting mixture was allowed to react for 10–12 h at 0–5 °C. The white solid obtained was filtered and washed with cold water (20 mL) and 95% ethanol (20 mL). The solid was dried under vacuum at room temperature (RT) to obtain compound 1 as a white solid in 87.1% (9.22 g) yield. 1H NMR (D2O): δ 3.02 (t, 2H), δ2.00 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (MeCN/D2O): δ 72.9 (t), δ 39.33 (s), δ 29.94 (s), δ 21.48 (t). 31P NMR (H3PO4/D2O): δ 18.53. MS (MALDI-TOFMS): 272 [M+H+Na]+.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of alendronate 1 and HBP 2.

Synthesis of tri-tert-butyl 2-(2-oxo-2-(2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenoxy)ethyl)hydrazine-1,1,2-tricarboxylate (11)

Tri-BOC-hydrazinoacetate (10) (90.0 mg, 0.231 mmol) and TFP (42.1 mg, 0.254 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL chloroform. DCC (52.3 mg, 0.254 mmol) in 5 mL chloroform was added dropwise to the reaction mixture and stirred at RT. The progress of the reaction was followed by thin layer chromatography (TLC). After complete consumption of 10 (3 h), the 1,3-dicyclohexyl urea formed in the reaction mixture was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was then suspended in an adequate amount of hexane, the remaining 1,3-dicyclohexyl urea was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to obtain crude compound 11. The crude material was purified by column chromatography (hexane/acetone 85/15 v/v) to obtain pure compound 11 as a pale yellow liquid in 97% (120.5 mg) yield. 1H NMR (CD3CN): δ 7.25 (m, 1H), δ 3.20 (s, 2H) δ 1.45 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 168.01 (s), δ 154.35 (s), δ 153.75 (s), δ 150.54 (s), δ 148.70 (s), δ 147.10 (s), δ 146.40 (s), δ 102.10 (s), δ 84.22 (s), δ 83.27 (s), δ 82.21 (s), δ 54.33 (m), δ 28.20 (s).

Synthesis of (4-(2-hydrazinylacetamido)-1-hydroxybutane-1,1-diyl)bisphosphonic acid (2)

Compound 1 (50.0 mg, 0.154 mmol) was suspended in 1 mL of deionized water, and TEA (93.2 mg, 0.923 mmol) was added to the suspension. After a few seconds of stirring at RT, the suspension became clear. The reaction was stirred at RT for 5 min. Compound 11 (124 mg, 0.231 mmol) was dissolved in 1.5 mL of acetonitrile and added to the reaction mixture. TEA (15.5 mg, 0.154 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 12 h. The reaction mixture was washed with diethyl ether (10 mL) and evaporated in vacuo. The obtained solid was treated with 2 mL of 2.5 M HCl, and the solution was stirred at RT for 24 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the crude product was sonicated twice in ethanol at RT for 2 h and filtered to obtain a white solid of pure compound 2 in 62% (31 mg) yield. 1H NMR (D2O): δ 3.78 (s, 2H), δ 3.28 (t, 2H), δ 1.99 (m, 2H), δ 1.84 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (MeCN/D2O): δ 170.41 (s), δ 74.17 (t), δ 51.58 (s), δ 40.50 (s), δ 31.75 (s), δ 24.17 (s). 31P NMR (H3PO4/D2O): δ 19.08. MS (+ ESI) : 322 [M+H]+.

General Procedure for Synthesis of Compounds 13a–13f

Compound 12a–12f (0.401 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) was suspended in 1 mL of deionized water, and TEA (0.668 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) was added to the suspension. After a few seconds of stirring at RT, the suspension became clear. The reaction was stirred at RT for 5 min. Compound 11 (0.334 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was dissolved in 1.5 mL of acetonitrile, and the solution was added to the reaction mixture. TEA (0.167 mmol, 0.5 equiv.) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 12 h. The reaction mixture was washed with diethyl ether, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo to obtain crude compound 13a–13f. The crude product 13a–13f was used in the next reaction without further purification.

Compound 13a

Following the procedure shown for 13a–13f, compound 13a was obtained by amide coupling of compound 11 and glycine (12a) as a paste in 95% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.10 (s, 2H), δ 3.98 (s, 2H), δ 1.45 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 174.56 (s), δ 168.46 (s), δ 154.46 (s), δ 153.86 (s), δ 150.65 (s) δ 84.52 (s), δ 83.16 (s), δ 82.45 (s), δ 54.93 (m), δ 45.91 (m), δ 28.22 (s).

Compound 13b

Following the procedure shown for 13a–13f, compound 13b was obtained by amide coupling of compound 11 and 4-aminobutenoic acid (12b) as a paste in 97% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.10 (s, 2H), δ 3.60 (d, 2H), δ 2.35 (m, 2H), δ 1.30 (m, 2H), δ 1.45 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 182.70 (s), δ 170.70 (s), δ 154.30 (s), δ 153.40 (s), δ 150.56 (s) δ 84.24 (s), δ 83.56 (s), δ 82.10 (s), δ 54.30 (m), δ 39.41 (m), δ 35.60 (m), δ 28.41 (s), δ 23.42 (m).

Compound 13c

Following the procedure shown for 13a–13f, compound 13c was obtained by amide coupling of compound 11 and glycylglycine (12c) as a paste in 94% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.02 (s, 2H), δ 3.99 (s, 2H), δ 3.80 (s, 2H), δ 1.45 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 174.44 (s), δ 169.24 (s), δ 168.43 (s), δ 154.34 (s), δ 153.55 (s), δ 151.20 (s), δ 85.12 (s), δ 83.66 (s), δ 83.05 (s), δ 55.15 (m), δ 45.24 (m), δ 43.31 (m), δ 28.15 (s).

Compound 13d

Following the procedure shown for 13a–13f, compound 13d was obtained by amide coupling of compound 11 and 6-aminohexanoic acid (12d) as a paste in 96% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.03 (s, 2H), δ 3.33 (d, 2H), δ 2.21 (t, 2H), δ 1.61 (m, 2H), δ 1.45 (m, 27H), δ 1.28 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 178.04 (s), δ 170.20 (s), δ 154.44 (s), δ 153.34 (s), δ 151.84 (s), δ 85.11 (s), δ 83.24 (s), δ 83.48 (s), δ 54.35 (m), δ 38.92 (m), δ 34.32 (m), δ 29.15 (s), δ 28.40 (s), δ 26.37 (s), δ 24.75 (s).

Compound 13e

Following the procedure shown for 13a–13f, compound 13e was obtained by amide coupling of compound 11 and glycylglycylglycine (12e) as a paste in 93% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.01 (s, 2H), δ 3.98 (d, 2H), δ 3.91 (d, 2H), δ 3.80 (d, 2H), δ 1.42 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 174.45 (s), δ 169.75 (s), δ 169.51 (s), δ 168.01 (s), δ 154.55 (s), 151.40 (s), 151.14 (s), δ 85.40 (s), δ 85.29 (s), δ 83.51 (s), δ 55.49 (m), δ 45.30 (m), δ 43.77 (m), δ 43.34 (s), δ 28.19 (s).

Compound 13f

Following the procedure shown for 13a–13f, compound 13f was obtained by amide coupling of compound 11 and 8-aminooctanoic acid (12f) as a paste in 95% yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.02 (s, 2H), δ 3.23 (m, 2H), δ 2.22 (t, 2H), δ 1.59 (m, 4H), δ 1.45 (m, 27H), δ 1.25 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 178.40 (s), δ 170.05 (s), δ 154.14 (s), 151.25 (s), 151.19 (s), δ 85.17 (s), δ 85.39 (s), δ 83.89 (s), δ 38.90 (m), δ 34.00 (t), δ 30.10 (m), δ 29.12 (s), δ 29.65 (s), δ 26.58 (s), δ 24.54 (s).

General Procedure for Synthesis of Compounds 14a–14f

Compound 13a–13f (0.386 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and TFP (0.425 mmol, 1.1 equiv.) were dissolved in 15 mL chloroform. DCC (0.425 mmol, 1.1 equiv.) in 10 mL chloroform was added dropwise to the reaction mixture and stirred at RT. The progress of the reaction was followed by TLC. After complete consumption of 13a–13f (3 h), the 1,3-dicyclohexyl urea formed in the reaction mixture was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was then suspended in an adequate amount of hexane, the remaining 1,3-dicyclohexyl urea was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to obtain crude compound 14a–14f. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH 90/10 v/v) to obtain the pure compound as a pale yellow liquid.

Compound 14a

Following the procedure shown for 14a–14f, compound 14a was obtained from 13a by treatment of TFP and DCC as a sticky liquid. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.60 (s, 1H), δ 4.25 (s, 2H), δ 4.10 (s, 2H), δ 1.42 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 174.02 (s), δ 168.32 (s), δ 154.21 (s), δ 153.14 (s), δ 150.78 (s), δ 148.72 (d), δ 146.89 (d), δ 146.10 (s), δ 101.80 (s), δ 84.12 (s), δ 83.85 (s), δ 82.64 (s), δ 54.41 (m), δ 45.00 (m), δ 28.44 (s).

Compound 14b

Following the procedure shown for 14a–14f, compound 14b was obtained from 13b by treatment of TFP and DCC as a sticky liquid. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.60 (s, 1H), δ 4.05 (s, 2H), δ 3.20 (d, 2H), δ 2.67 (m, 2H), δ 1.97 (m, 2H), δ 1.42 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 182.47 (s), δ 170.12 (s), δ 154.10 (s), δ 153.45 (s), δ 151.10 (s), δ 148.69 (d), δ 147.23 (d), δ 146.80 (s), δ 102.10 (s), δ 84.58 (s), δ 83.74 (s), δ 82.36 (s), δ 54.33 (m), δ 39.45 (m), δ 33.56 (m), δ 23.47 (s), δ 28.56 (s).

Compound 14c

Following the procedure shown for 14a–14f, compound 14c was obtained from 13c by treatment of TFP and DCC as a sticky liquid. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.98 (s, 1H), δ 4.38 (s, 2H), δ 4.11 (s, 2H), δ 3.41 (s, 2H), δ 1.45 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 170.28 (s), δ 169.52 (s), δ 167.00 (s), δ 156.00 (s), δ 151.12 (s), δ 150.02 (s), 148.23 (d), δ 147.45 (d), δ 146.69 (s), δ 102.47 (s), δ 85.67 (s), δ 85.00 (s), δ 83.90 (s), δ 55.87 (s), δ 45.65 (s), δ 43.06 (m), δ 28.14 (s).

Compound 14d

Following the procedure shown for 14a–14f, compound 14d was obtained from 13d by treatment of TFP and DCC as a sticky liquid. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.97 (s, 1H), δ 4.05 (s, 2H), δ 3.95 (s, 2H), δ 2.31 (m, 2H), δ 2.62 (m, 4H), δ 1.80 (m, 2H), δ 1.45 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 177.12 (s), δ 170.89 (s), δ 154.69 (s), δ 153.78 (s), δ 151.11 (s), 148.60 (d), δ 147.05 (d), δ 146.44 (s), δ 102.10 (s), δ 85.25 (s), δ 3.73 (s), δ 83.92 (s), δ 54.33 (m), δ 38.96 (m), δ 33.56 (m), δ 29.78 (s), δ 28.40 (s), δ 26.58 (s), δ 24.45 (s).

Compound 14e

Following the procedure shown for 14a–14f, compound 14e was obtained from 13e by treatment of TFP and DCC as a sticky liquid. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.75 (s, 1H), δ 4.42 (d, 2H), δ 4.10 (m, 4H), δ 3.85 (d, 2H), δ 1.50 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 170.81 (s), δ 170.10 (s), δ 170.05 (s), δ 165.87 (s), δ 156.00 (s), 154.80 (s), 151.20 (s), 148.48 (d), δ 147.23 (d), δ 146.10 (s), δ 103.76 (s), δ 85.79 (s), δ 85.51 (s), δ 84.07 (s), δ 55.96 (m), δ 49.46 (s), δ 43.61 (s), δ 40.82 (s), δ 28.11 (s).

Compound 14f

Following the procedure shown for 14a–14f, compound 14f was obtained from 13f by treatment of TFP and DCC as a sticky liquid. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.98 (s, 1H), δ 4.05 (s, 2H), δ 3.95 (s, 2H), δ 2.40 (s, 2H), δ 1.65 (m, 4H), δ 1.38 (m, 6H), δ 1.45 (m, 27H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 178.58 (s), δ 170.89 (s), δ 154.45 (s), 151.69 (s), 151.51 (s), 148.72 (d), δ 147.20 (d), δ 146.40 (s), δ 102.10 (s), δ 85.93 (s), δ 85.54 (s), δ 83.12 (s), δ 38.95 (m), δ 33.50 (t), δ 30.32 (m), δ 29.45 (s), δ 29.10 (s), δ 26.70 (s), δ 25.73 (s).

General Procedure for Synthesis of Compounds 3–8

Compound 1 (0.154 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was suspended in 1 mL of deionized water, and TEA (1.077 mmol, 7.0 equiv.) was added to the suspension. After a few seconds of stirring at RT, the suspension became clear. The reaction was stirred at RT for 5 min. Crude compound 14a–14f (0.231 mmol, 1.5 equiv.) was dissolved in 1.5 mL of acetonitrile and added to the reaction mixture. TEA (0.154 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 12 h. The reaction mixture was washed with diethyl ether (10 mL) and evaporated in vacuo. The obtained solid was treated with 2 mL of 2.5 M HCl, and the solution was stirred at RT for 24 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo, the crude product was sonicated twice in ethanol at RT for 2 h, and filtered to obtain pure compounds 3–8.

Compound 3

Following the procedure shown for 3–8, compound 1 was coupled to compound 14a by amide linkage, followed by an acid treatment to obtain pure compound 3 as a white solid in 55% yield. 1H NMR (D2O): δ 3.95 (s, 2H), δ 3.84 (s, 2H), δ 3.26 (t, 2H), δ 1.98 (m, 2H), δ 1.84 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (MeCN/D2O): δ 172.10 (s), δ 171.74 (s), δ 74.15 (t), δ 51.40 (s), δ 47.62 (s) δ 40.60 (s), δ 31.70 (s), δ 24.09 (s). 31P NMR (H3PO4/D2O): δ 19.16. MS (+ ESI) : 379 [M+H]+.

Compound 4

Following the procedure shown for 3–8, compound 1 was coupled to compound 14b by amide linkage, followed by an acid treatment to obtain pure compound 4 as a white solid in 63% yield. 1H NMR (D2O): δ 3.73 (s, 2H), δ 3.22 (t, 4H), δ 2.25 (t, 2H), δ 1.95 (m, 2H), δ 1.80 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (MeCN/D2O): δ 176.87 (s), δ 170.46 (s), δ 74.16 (t), δ 51.54 (s), δ 40.66 (s), δ 39.52 (s), δ 34.04 (s), δ 31.84 (s), δ 25.66 (t), δ 24.16 (s). 31P NMR (H3PO4/D2O): δ 19.32. MS (+ ESI) : 407 [M+H]+.

Compound 5

Following the procedure shown for 3–8, compound 1 was coupled to compound 14c by amide linkage, followed by an acid treatment to obtain pure compound 5 as a white solid in 56% yield. 1H NMR (D2O): δ 4.04 (s, 2H), δ 3.92 (s, 2H), δ 3.86 (s, 2H), δ 3.25 (t, 2H), δ 1.96 (m, 2H), δ 1.84 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (MeCN/D2O): δ 171.55 (s), δ 170.79 (s), δ 170.62 (s), δ 72.82 (t), δ 50.04 (s), δ 42.15 (s) δ 41.88 (s), δ 39.26 (s), δ 30.06 (s), δ 22.71 (s). 31P NMR (H3PO4/D2O): δ 19.08. MS (+ ESI) : 436 [M+H]+.

Compound 6

Following the procedure shown for 3–8, compound 1 was coupled to compound 14d by amide linkage, followed by an acid treatment to obtain pure compound 6 as a white solid in 59% yield. 1H NMR (D2O): δ 3.73 (s, 2H), δ 3.22 (q, 4H), δ 2.25 (t, 2H), δ 1.98 (m, 2H), δ 1.82 (m, 2H), δ 1.59 (t, 2H), δ 1.52 (t, 2H), δ 1.30 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (MeCN/D2O): δ 177.70 (s), δ 169.94 (s), δ 73.95 (t), δ 51.36 (s), δ 40.43 (s) δ 39.86 (s), δ 36.37 (s), δ 31.64 (s), δ 28.62 (s), δ 26.15 (s), δ 25.68 (s), δ 23.99 (s). 31P NMR (H3PO4/D2O): δ 19.14. MS (+ ESI) : 435 [M+H]+.

Compound 7

Following the procedure shown for 3–8, compound 1 was coupled to compound 14e by amide linkage, followed by an acid treatment to obtain pure compound 7 as a white solid in 54% yield. 1H NMR (D2O): δ 3.73 (s, 2H), δ 3.22 (q, 4H), δ 2.25 (t, 2H), δ 2.00 (m, 2H), δ 1.82 (m, 2H), δ 1.55 (t, 2H), δ 1.45 (t, 2H), δ 1.30 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (MeCN/D2O): δ 178.82 (s), δ 170.70 (s), δ 74.58 (t), δ 52.25 (s), δ 49.01 (s), δ 41.25 (s), δ 40.95 (s), δ 37.36 (s), δ 32.54 (s), δ 29.73 (s), δ 29.57 (s), δ 27.41 (s), δ 26.88 (s), δ 24.81 (s). 31P NMR (H3PO4/D2O): δ 19.38. MS (+ ESI) : 493 [M+H]+.

Compound 8

Following the procedure shown for 3–8, compound 1 was coupled to compound 14f by amide linkage, followed by an acid treatment to obtain pure compound 8 as a white solid in 57% yield. 1H NMR (D2O): δ 4.06 (s, 2H), δ 4.0 (s, 2H), δ 3.92 (s, 2H), δ 3.86 (s, 2H), δ 3.25 (t, 2H), δ 1.98 (m, 2H), δ 1.84 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (MeCN/D2O): δ 173.19 (s), δ 172.01 (s), δ 172.17 (s), δ 171.92 (s), δ 74.15 (t), δ 51.45 (s) δ 43.73 (s), δ 43.49 (s), δ 43.15 (s), δ 40.60 (s), δ 31.67 (s), δ 24.15 (s). 31P NMR (H3PO4/D2O): δ 19.15. MS (+ ESI) : 463 [M+H]+.

Crystal Growth Inhibition Assay for Binding Affinity Study

As BPs target bone surfaces under active formation and resorption of HA,41 a crystal growth inhibition assay was performed to measure the affinities of HBPs to HA. This method has commonly been used to examine BP binding affinity.42,43 Kinetic experiments of HA crystal growth were performed in a nitrogen atmosphere in magnetically stirred (400 rpm) double-jacketed vessels at pH 7.4 and 37.0 ± 0.1 °C, as described in a previously reported procedure.42,43 In brief, the reaction solution with final ionic strength of 0.15 M was prepared by mixing calcium chloride (2.0 mmol), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (2.0 mmol) and sodium chloride (132.0 mmol) followed by degassing and filtration. The titrant with final ionic strength of 0.15 M was prepared by mixing calcium chloride (2.0 mmol), potassium hydroxide (10.0 mmol) and sodium chloride (134.0 mmol) followed by degassing and filtration. The reaction was initiated by adding 5 mg seed mass of HA crystallites into 100 mL of reaction solution. The constant thermodynamic driving force for growth of HA crystals was maintained by keeping the pH constant at 7.4 with addition of titrant. The volume of titrant added was recorded as a measure of HA crystal growth. Crystal growth inhibition experiments were performed in presence of at least six different concentration of each of HBPs (2–8). For positive control, experiments were performed in presence of six different concentrations of alendronate (1), whereas for negative control, experiments were performed in absence of any BP.

Cell Culture

The MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in pre-warmed αMEM medium that was supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere composed of 5% CO2. The cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well for in vitro quantification of intracellular protein and caspase activity. One day after seeding, the cultures were treated with various concentrations (1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−5, and 1 × 10−4 M) of HBPs. Cells without HBPs were used as a negative control, while cells treated with 10−6, 10−5, or 10−4 M of etoposide were used as positive controls. The plates were incubated again for 24, 48, 72 h before use for further analysis. The experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated at least three times to ascertain the reproducibility of the results.

Intracellular Protein Quantification

Intracellular protein was measured using a commercially available BCA assay kit. Briefly, the medium was removed, and the adherent cells were washed with PBS. The cultures were lysed by 10-min incubation in 50 μL of lysate buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10mM NaF, 1mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.14 U/ml aprotinin, 1mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100), followed by 2 s of sonication. Volumes of 10 μL of the cell lysate samples and standards (solutions of known concentrations of bovine serum albumin) were added to the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate followed by addition of 200 μL of the working reagent; the well contents were mixed thoroughly by shaking the plate for 2 min. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and then cooled to RT. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 562 nm on a plate reader. The amount of protein in the sample was calculated using a standard plot.

Cell Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of the HBPs was determined using a colorimetric WST-1 assay. The assay was conducted after 72 h of HBP treatment in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, cultures in 96-well plates were incubated with 10 μL/well of cell proliferation reagent WST-1 at 37 °C for 60 min in a humidified atmosphere composed of 5% CO2. The plate was cooled to RT, and the absorbance of the samples was measured at 450 nm on a plate reader.

Apoptosis Assay

Apoptosis was determined by measuring the intracellular caspase-3 activity. The cultures were lysed by 10 min of incubation in 50 μL of lysate buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10mM NaF, 1mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.14 U/ml aprotinin, 1mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, and 1% (v/v)Triton X-100), followed by 2 s of sonication. The cell lysate was treated with 50 μM Ac-DEVD-AFC in 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% CHAPS, 10 mM DTT, 1mM EDTA, and 10% (v/v) glycerol) at RT for 60 min in the dark. The caspase-3 activity was determined by measuring the fluorescence at λem=510 nm (λex=485).

Synthesis of Compound 16

Compound 2 (10.0 mg, 0.028 mmol) was suspended in 10 mL of deionized water. The reaction mixture was acidified with 10 μL of acetic acid. 4-Nitro benzaldehyde (15) (8.4 mg, 0.056 mmol) was dissolved in DMSO and added to the above suspension. The reaction was stirred at RT for 48 h. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to obtain crude product 16. Compound 16 was dissolved in water and washed with ethyl acetate to remove excess reactant 15. The water layer containing 16 was used in the next reaction without further purification.

Synthesis of Compound 19

4-Nitro benzoic acid (18) (100.0 mg, 0.598 mmol) and TFP (109.3 mg, 0.658 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL acetone. DCC (135.8 mg, 0.658 mmol) in 5 mL acetone was added dropwise to the reaction mixture and stirred at RT. The progress of the reaction was followed by TLC. After complete consumption of 18 (3 h), the 1,3-dicyclohexyl urea formed in the reaction mixture was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was then suspended in an adequate amount of acetonitrile, the remaining 1,3-dicyclohexyl urea was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to obtain crude compound 19. Compound 19 was used in the next reaction without further purification.

Synthesis of Compound 20

Compound 1 (60.0 mg, 0.185 mmol) was suspended in 1 mL of deionized water and TEA (111.9 mg, 1.108 mmol) was added to the suspension. After a few seconds of stirring at RT, the suspension became clear. The reaction was stirred at RT for 5 min. Crude compound 19 (92.2 mg, 0.277 mmol) was dissolved in 1.5 mL of acetonitrile and added to the reaction mixture. TEA (18.7 mg, 0.185 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 12 h. The reaction mixture was washed with 10 mL diethyl ether several times, and the water layer was lyophilized to obtain a sticky solid. The reaction product was then sonicated twice in ethanol for 2 h at RT and filtered to obtain pure compound 20. 1H NMR (D 2O): δ 8.33 (d, 2H), δ 7.95 (d, 2H), δ 3.45 (t, 2H), δ 1.98 (m, 4H). 31P NMR (H3PO4/D2O): δ 18.23. MS (- ESI) : 397 [M-H]-.

In vitro Studies of Drug Targeting and Drug Release

Compound 16 is a HBP-drug conjugate, where a model drug (4-NBA) is conjugated to HBP 2 via hydrazone linkage. The conjugate was immobilized on HA surface and studied for its release at various pH solutions. In brief, compound 16 (1 mg) in water was equally distributed into three Eppendorf tubes and diluted to get 1.0 mL of total volume each. Excess of HA (50.0 mg) was added to each Eppendorf tube, and the tubes were stirred at RT for 0.5 h. After centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded. The HA was washed twice with 1.0 mL water, followed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was discarded. A volume of 1.0 mL acetate solution (0.1 M sodium acetate, 0.05 M sodium chloride) of pH 5.0, 6.0, and 7.4 was added in three Eppendorf tubes, respectively. The Eppendorf tubes were incubated at 37 °C with continuous shaking. The suspensions were centrifuged at particular time points, and the absorbance of the supernatants was measured (λ = 265 nm, 1-cm cuvette) to calculate the amount of 4-NBA released from the immobilized conjugate.

For the control studies, the above experiment was repeated with compound 20. Compound 20 is a BP-drug conjugate, where the model drug (4-NBA) is conjugated to alendronate via amide linkage. The conjugate was immobilized on the HA surface and studied for its release at various pH solutions. In brief, compound 20 (1 mg) in water was equally distributed into three Eppendorf tubes and diluted to get 1.0 mL of total volume each. Excess of HA (50.0 mg) was added to each Eppendorf tube, and the tubes were stirred at RT for 0.5 h. After centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded. The HA was washed twice with 1 mL water, followed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was discarded. A volume of 1.0 mL acetate solution (0.1 M sodium acetate, 0.05 M sodium chloride) of pH 5.0, 6.0, and 7.4 was added in three Eppendorf tubes, respectively. The Eppendorf tubes were incubated at 37 °C with continuous shaking. The suspensions were centrifuged at particular time points, and the absorbance of the supernatants was measured (λ = 265 nm, 1-cm cuvette) to calculate the amount of 4-NBA released from the immobilized conjugate.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

BPs have high affinity toward bone and HA. After administration, BPs bind to bone surfaces where they can be internalized into osteoclasts and cause their apoptosis.44–46 In other words, BPs control bone resorption through apoptosis of osteoclasts. However, this could be a drawback of the BP treatment because it disturbs the bone remodeling cycle. In general, bone remodeling is the life-long process, whereby osteoblasts and osteoclasts work simultaneously for bone formation and bone resorption, respectively. Bone formation and bone resorption are interdependent processes and, therefore, osteoblastic function of bone formation also gets affected by controlling osteoclastic bone resorption. Along with controlling bone resorption, subsequent bone formation at resorption sites is crucial; this can be achieved by delivering therapeutic agents to bone resorption sites using bisphosphonates. Active drug targeting at sites of bone metastases and calcified neoplasms using polymeric carrier was reported previously. Alendronate and an anti-angiogenic agent, TNP-470, were conjugated to N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) through a cathepsin K sensitive tetrapeptide (Gly-Gly-Pro-Nle).47,48 Because of alendronate conjugation, HPMA was found to be distributed to bone tumors and the endothelial compartments of bone metastases with a good antitumor efficacy. However, one could eliminate the polymeric carrier and make a simpler and smaller conjugate by coupling drugs directly to high affinity BPs via hydrolyzable bonds. Therefore, our overall goal is to make BPs capable of delivering drug molecules, including bone growth factors, at bone resorption sites. The first goal was to design novel BPs that demonstrate high binding affinity to HA and contain a functional group that could be used to conjugate therapeutic agents to BPs through an acid-labile linkage. Substituents (R1 and R2) at the germinal carbon of the BP contribute toward bone affinity; in particular, the presence of a hydroxyl at R1 enhances bone affinity by enabling tridentate binding to HA.10–12 In that regard, we chose 1-hydroxy-1,1-bisphosphonic acid as the basic backbone of bifunctional BPs.

The designed 1-hydroxy-1,1-bisphosphonic acid backbone has a hydroxyl at R1, while the R2 substituent was used to introduce a different functional group that could be subsequently used for attachment of therapeutic agents. The attachment of a therapeutic agent to BP is possible through several reversible and irreversible linkages such as amide, ester, imine, hydrazone, ether, and thioether coupling. However for drug delivery at wound healing sites and resorption sites, where the pH is acidic,49,50 acid-labile linkages such as those provided by hydrazones and imines are more appropriate. Imine hydrolyses rapidly at pH ≤ 7.0,51 while hydrazone is stable at physiological pH. Further, the rate of hydrolysis of the hydrazone linkage increases gradually with decrease in pH from 7.4.52,53 Therefore, the hydrazone linkage presents advantages over the imine linkage when sustained drug release is desired at the bone surface. Hence, the hydrazine functionality was introduced in 1-hydroxy-1,1-bisphosphonic acid at R2 to obtain bifunctional HBPs.

It is important that the HBP-drug conjugate should not only be stable during systemic circulation, but should also bind to the bone surface before releasing the drug at the desired site. The attached drug may sterically affect this interaction between the BP and the bone surface. Consequently, a spacer was introduced in the synthesized HBPs between the BPs and the terminal hydrazine. HBPs with several spacers of varying length and hydrophobicity were synthesized.

A straightforward synthesis was used to create the desired HBPs (2–8). Compound 2 has the shortest spacer attaching hydrazine to 1-hydroxy-1,1-bisphosphonic acid. To synthesize HBP 2, monosodium alendronate was prepared first in an inert atmosphere according to a previously reported procedure from 4-aminobutanoic acid by reaction with phosphorous acid and phosphorous trichloride in methanesulfonic acid and subsequent hydrolysis.39,40 The reactive ester of TBHA (10) was prepared by drop-wise addition of DCC in chloroform to a mixture of TBHA and TFP in chloroform at RT. This reactive ester was then coupled with monosodium alendronate in basic condition at RT to obtain BOC-protected HBP 2. The BOC-protection of the hydrazine group was removed with treatment of 2.5 M HCl to obtain HBP 2. The crude product was sonicated twice in ethanol at RT for 2 h and filtered to obtain pure HBP 2 (Scheme 1).

Using a similar strategy, six other analogues of HBP 2, (3–8) with spacers of different length and hydrophobicity were synthesized by introducing various amino acids, such as glycine (12a), 4-aminobutanoic acid (9), glycylglycine (12c), 6-aminohexanoic acid (12d), glycylglycylglycine (12e), and 8-aminooctanoic acid (12f), respectively (Scheme 2). All seven HBPs were obtained and were characterized with 1H NMR, 31P NMR, 13C NMR, and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of HBPs 3–8.

The binding affinities of the HBPs were measured and compared with alendronate, which is a commercially available BP having high affinity to HA. BPs are known to inhibit the crystal growth of HA and target bone surfaces under active formation and resorption of HA.41 Therefore, a crystal growth inhibition assay, which is a widely used method for determination of binding affinity of BP,42,43 was performed to measure the affinities of HBPs to HA. During the experiments, a favorable environment for crystal growth of HA was maintained. The crystal growth of HA was measured in presence of various concentration HBPs. The pH was maintained at 7.4 by addition of titrant, and the volume of titrant added was recorded as a measure of HA crystal growth. A range of experiments were performed in presence of various concentrations (0, 1.0 × 10−7, 2.5 × 10−7, 5.0 × 10−7, 7.5 × 10−7, and 1.0 × 10−6 M) of HBPs and alendronate. For every experiment of HA crystal growth, a plot of the volume of titrant added vs time was generated. A typical set of plots is depicted in Figure 1. The growth rate (R) at any instant can be described by

Figure 1.

(A) Plot of HA crystal growth in presence of varying concentrations of HBP 2 at pH 7.4 and 37 °C (seed mass = 5 mg);

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

represent 0, 1.0 × 10−7, 2.5 × 10−7, 5.0 × 10−7, 7.5 × 10−7, and 1.0 × 10−6 M HBP 2, respectively. (B) Relative adsorption affinity constants (KL) of alendronate (1) and HBPs 2–8 measured at varying concentrations of BPs (C=1.0 × 10−7, 2.5 × 10−7, 5.0 × 10−7, and 7.5 × 10−7 M) at pH 7.4 and 37 °C. Data are the average ± one standard deviation (n = 4).

represent 0, 1.0 × 10−7, 2.5 × 10−7, 5.0 × 10−7, 7.5 × 10−7, and 1.0 × 10−6 M HBP 2, respectively. (B) Relative adsorption affinity constants (KL) of alendronate (1) and HBPs 2–8 measured at varying concentrations of BPs (C=1.0 × 10−7, 2.5 × 10−7, 5.0 × 10−7, and 7.5 × 10−7 M) at pH 7.4 and 37 °C. Data are the average ± one standard deviation (n = 4).

| (S1) |

where dV/dt is the rate of titrant addition, and β is a constant whose value reflects the titrant concentration with respect to the surface area of HA during crystal formation; β was considered as constant for all experiments.

It can be noted from Figure 1 that the HA crystals appear to grow non-linearly during the early stage of the experiment due to initial seeding of the HA crystals. The flat line parallel to the X-axis indicates the complete prevention of crystal growth. A pseudo-Langmuir adsorption isotherm can be used to describe the rates of HA crystal growth and can be expressed by

| (S2) |

where C is the concentration of BP added, and R0 and Ri are the rates of HA crystal growth in the absence and presence of BP, respectively.

By rearranging equations S1 and S2, the relative adsorption affinity constants (KL) can be described by

| (S3) |

where dV0/dt and dVi/dt are the rates of titrant addition at early stage of the experiment in the absence and presence of BP, respectively.

The relative trend of binding affinities of alendronate (1) and HBPs (2–8) at various concentrations of BPs is shown in Figure 1. The shorter length HBPs (2 and 3) showed significantly higher binding affinities than alendronate (p<0.05). Overall, all seven HBPs showed high binding affinities to HA, which makes them suitable for drug targeting.

Apart from its targeting ability, the ideal drug-carrier should not induce unnecessary toxic effects, especially against bone-forming cells (osteoblasts). HBPs could also have toxic affects toward other cells and tissues or affect cell differentiation, which could cause substantial morbidity.54 The primary purpose of this study was to demonstrate the potential of HBPs for targeted delivery of the attached drugs at bone-resorption sites through in vitro experiments. Therefore, HBPs at various concentrations (10−6 - 10−4 M) were evaluated for their possible cytotoxicity and apoptotic effect against pre-osteoblasts. The intracellular protein measured after 24, 48, and 72 h treatment of HBPs, showed no abnormal changes in cell proliferation (Figure 2). The amount of protein in the HBP-treated cells was similar to the control over a period of 72 h. Cell viability studies were performed and metabolic activity was quantified using the commercially available WST-1 kit. MC3T3-E1 cells exposed to HBPs for 72 h showed activity similar to that of control (Figure 3). Although, the metabolic activity of cells exposed to 10−4 M HBPs for 72 h showed 10% decrease in cell viability, the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Intracellular protein contents showing MC3T3-E1 cell growth for 72 h after HBP treatment. Plots A, B, and C show results for exposure to HBPs at 1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−5, and 1 × 10−4 M, respectively.

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

represent addition of no HBP (control), HBP 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, respectively. Error bars denotes standard deviations.

represent addition of no HBP (control), HBP 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, respectively. Error bars denotes standard deviations.

Figure 3.

MC3T3-E1 cell viability measured after 72 h of incubation with no HBP (CON), HBP 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 at different concentrations (1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−5, and 1 × 10−4 M). The data are expressed as percentage of the control. ▭,

,

,

, and

, and

represent treatment of no HBP (control), 1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−5, and 1 × 10−4 M HBPs, respectively. Error bars denotes standard deviations.

represent treatment of no HBP (control), 1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−5, and 1 × 10−4 M HBPs, respectively. Error bars denotes standard deviations.

Because caspases are required for cell apoptosis, the possibility of HBP-induced cell apoptosis was evaluated by measuring caspase-3 activity. Caspase-3 is a cysteine-aspartic acid protease and cleaves Ac-DEVD-AFC releasing the fluorogenic AFC, which can be quantified by fluorescence spectroscopy.55 Apoptosis of MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts was confirmed by treatment with 10−6, 10−5, or 10−4 M etoposide for 72 h, which resulted in 2–3 fold increase in caspase-3 activity (results not shown). As shown in Figure 4, however, HBPs did not induce apoptosis in MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts after 72 h of exposure; all treatments resulted in statistically similar levels of caspase activity. Because HBPs showed no apoptotic and cytotoxic effects on pre-osteoblasts, HBPs could be utilized as a vehicle for drug delivery applications.

Figure 4.

Apoptosis of MC3T3-E1 cells measured 72 h following addition of no HBP (CON), HBP 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 at three different concentrations (1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−5, and 1 × 10−4 M). The data are expressed as fold increase relative to the control. ▭,

,

,

, and

, and

represent treatment of no HBP (control), 1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−5, and 1 × 10−4 M HBPs, respectively. Error bars denotes standard deviations.

represent treatment of no HBP (control), 1 × 10−6, 1 × 10−5, and 1 × 10−4 M HBPs, respectively. Error bars denotes standard deviations.

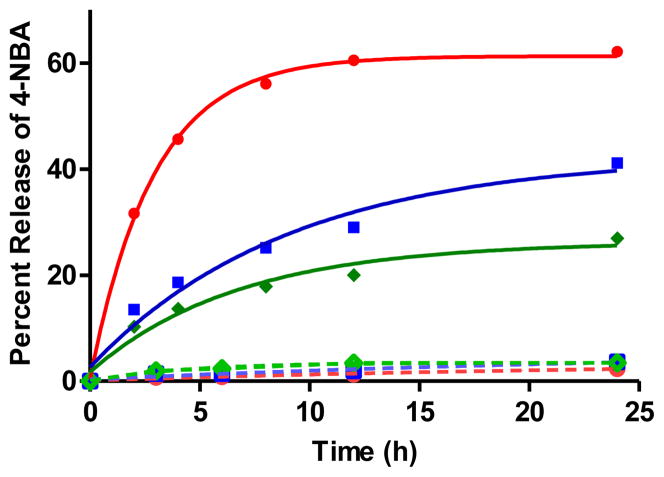

HBP 2 was used to demonstrate the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents to bone. In particular, in vitro drug targeting to HA and drug release from the HA surface was demonstrated using 4-NBA as a model drug. 4-NBA was conjugated with HBP 2 in DMSO/water, and then the conjugate was immobilized on HA by adding excess of HA particles to the reaction mixture at RT. HA with the attached conjugate was separated by centrifugation and washed thoroughly with water to remove unconjugated 4-NBA (Scheme 3). The triggered release of 4-NBA from the immobilized 4-NBA-HBP conjugate on HA was demonstrated at various pH as shown in Figure 5. HA with the attached conjugate was resuspended in 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 5.0, 6.0 or 7.4) and incubated at 37 °C. The suspensions were centrifuged at particular time points, and the absorbance of the supernatants was measured at 265 nm using a UV-vis spectrophotometer to calculate the amount of released 4-NBA. It was observed that in the first 12 h of incubation, there was approximately 60%, 30% and 20% of 4-NBA released from the immobilized conjugate at pH 5.0, 6.0, and 7.4, respectively. Since HBPs have higher affinity for bone than does alendronate, they are expected to carry and deliver the attached drug at bone resorption sites as well as calcified bone tumors. Similar to this study, drug release at resorption sites was previously reported using a polymeric system with a spacer composed of a cathepsin K sensitive tetrapeptide (Gly-Gly-Pro-Nle).56 Cathepsin K, which is expressed at higher level in osteoclasts, could cleave the polymer at the cathepsin K sensitive tetrapeptide and initiate drug release. However, cleavage of the polypeptide by cathepsin K could be affected by steric hindrance, which could change the rate of drug release. On the other hand, HBPs are not crowded molecules, and therefore the rate of hydrolysis of the hydrazone and consequent drug release is expected to be affected less by steric effects.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis, immobilization of model drug-BP conjugate, and incubation at 37 °C in acetate solutions of various pH. Hatched area represents HA particles.

Figure 5.

Percent release of 4-NBA (percentage of cleaved hydrazone bonds) from the immobilized conjugate on HA surface at 37 °C;

,

,

,

,

represent release at pH 5.0, 6.0, and 7.4, respectively. Solid line and dotted line represent 4-NBA release from 17 and 21, respectively.

represent release at pH 5.0, 6.0, and 7.4, respectively. Solid line and dotted line represent 4-NBA release from 17 and 21, respectively.

To confirm that release of 4-NBA occurs via hydrazone cleavage rather than through desorption of the conjugate from the HA surface, 4-NBA was conjugated to alendronate (1) through formation of an amide bond. The conjugate was immobilized on HA surface by adding excess of HA particles, and then the particles were washed thoroughly with water to remove unconjugated 4-NBA and non-specifically adsorbed conjugate molecules. HA with the attached conjugate was treated similarly as described above, and the amount of released 4-NBA was measured by UV-vis spectroscopy (Scheme 3). From the control experiments, it was observed that there was no significant release of 4-NBA through desorption from the immobilized conjugate 21 (Figure 5).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have reported the synthesis of novel, bifunctional HBPs (2–8), which show high binding affinities to HA. Through in vitro experiments, HBPs demonstrated no apoptotic and cytotoxic effects on MC3T3-E1, a pre-osteoblast cell. 4-NBA, a model drug, was bound to HA through a HBP, and its in vitro release at various pH was recorded. It was observed that hydrolysis of hydrazone bonds in the conjugate and subsequent release of 4-NBA was slow at physiological pH, but much faster at pH lower than physiological, such as the pH in bone resorption sites and sites of wound healing.49,50 Consequently, HBP-drug conjugates could be useful in locally delivering attached drugs to the resorptive microenvironment of bone tissue. Overall, this approach should improve the therapeutic index by boosting pharmacological efficacy and diminishing undesirable side effects.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (W81XWH-09-1-0461) and the National Institutes of Health (AR048700). J.Y. thanks the University of Kentucky for a Research Challenge Trust Fund fellowship supporting this research. We thank Drs. M. Watson, A. Cammers, Y. Wei, E. Dikici and E. Zahran for useful discussions.

References

- 1.Langer R. Drug delivery: Drugs on target. Science. 2001;293:58–59. doi: 10.1126/science.1063273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harada S, Rodan GA. Control of osteoblast function and regulation of bone mass. Nature. 2003;423:349–355. doi: 10.1038/nature01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goltzman D. Discoveries, drugs and skeletal disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2002;1:784–796. doi: 10.1038/nrd916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salo J, Lehenkari P, Mulari M, Metsikkö K, Väänänen HK. Removal of osteoclast bone resorption products by transcytosis. Science. 1997;276:270–273. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deal C. Future therapeutic targets in osteoporosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:380–385. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832cbc2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vondracek SF, Linnebur SA. Diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in the older senior. Clin Interventions Aging. 2009;4:121–136. doi: 10.2147/cia.s4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodan GA, Martin TJ. Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science. 2000;289:1508–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polascik TJ. Bisphosphonates in oncology: Evidence for the prevention of skeletal events in patients with bone metastases. Drug Des, Dev Ther. 2009;3:27–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lumachi F, Brunello A, Roma A, Basso U. Medical treatment of malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:415–421. doi: 10.2174/092986708783497346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang S, Gangal G, Uludağ H. ‘Magic bullets’ for bone diseases: Progress in rational design of bone-seeking medicinal agents. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:507–531. doi: 10.1039/b512310k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Beek ER, Lowik C, Que I, Papapoulos S. Dissociation of binding and antiresorptive properties of hydroxy bisphosphonates by substitition of the hydroxyl with an amino group. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:1492–1497. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunberg RJ, Ebetino FH, Mosher CT, Roof CF. Designing drugs for stronger bones. Chemtech. 1991;21:305–309. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapurlat RD, Delmas PD. Drug insight: Bisphosphonates for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:211–219. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peppas NA. Intelligent therapeutics: Biomimetic systems and nanotechnology in drug delivery. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2004;56:1529–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peppas NA. Vecteurs de médicaments innovants et ≪ intelligents Gt; : leurs applications pharmaceutiques. Ann Pharm Fr. 2006;64:260–275. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4509(06)75319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langer R, Peppas NA. Advances in biomaterials, drug delivery, and bionanotechnology. AIChE J. 2003;49:2990–3006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh Y-K, Senter PD, Song S-C. Intelligent drug delivery systems. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:1813–1815. doi: 10.1021/bc900260x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacEwan SR, Chilkoti A. Elastin-like polypeptides: Biomedical applications of tunable biopolymers. Pept Sci. 2010;94:60–77. doi: 10.1002/bip.21327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Betre H, Liu W, Zalutsky MR, Chilkoti A, Kraus VB, Setton LA. A thermally responsive biopolymer for intra-articular drug delivery. J Control Release. 2006;115:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang D, Miller SC, Shlyakhtenko LS, Portillo AM, Liu X-M, Papangkorn K, Kopečková P, Lyu chenko Y, Higuchi WI, Kopeček J. Osteotropic peptide that differentiates functional domains of the skeleton. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1375–1378. doi: 10.1021/bc7002132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D, Sima M, Mosley RL, Davda JP, Tietze N, Miller SC, Gwilt PR, Kopečková P, Kopeček J. Pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies of a bone-targeting drug delivery system based on N-(2-Hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymers, Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2006;3:717–725. doi: 10.1021/mp0600539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson WJ, Thompson DD, Anderson PS, Rodan GA. Polymalonic acids as boneaffinity agents. 0341961 EP. 1989

- 23.Orme MW, Labroo VM. Synthesis of [beta]-estradiol-3-benzoate-17-(succinyl-12A-tetracycline): A potential bone-seeking estrogen. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1994;4:1375–1380. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng H, Weng L. Bone resorption inhibition/osteogenesis promotion pharmaceutical composition. 5,698,542 US. 1997

- 25.Hirabayashi H, Takahashi T, Fujisaki J, Masunaga T, Sato S, Hiroi J, Tokunaga Y, Kimura S, Hata T. Bone-specific delivery and sustained release of diclofenac, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, via bisphosphonic prodrug based on the osteotropic drug delivery system (ODDS) J Control Release. 2001;70:183–191. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gil L, Han Y, Opas EE, Rodan GA, Ruel R, Seedor JG, Tyler PC, Young RN. Prostaglandin E2-bisphosphonate conjugates: Potential agents for treatment of osteoporosis. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:901–919. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ora M, Lönnberg T, Florea-Wang D, Zinnen S, Karpeisky A, Lönnberg H. Bisphosphonate derivatives of nucleoside antimetabolites: Hydrolytic stability and hydroxyapatite adsorption of 5′-β,γ-methylene and 5′-β,γ-(1-hydroxyethylidene) triphosphates of 5-fluorouridine and ara-cytidine. J Org Chem. 2008;73:4123–4130. doi: 10.1021/jo800317e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Mabhouh A, Angelov C, McEwan A, Jia G, Mercer J. Preclinical investigations of drug and radionuclide conjugates of bisphosphonates for the treatment of metastatic bone cancer. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2004;19:627–640. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2004.19.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herczegh P, Buxton TB, McPherson JCI, Kovács-Kulyassa Á, Brewer PD, Sztaricskai F, Stroebel GG, Plowman KM, Farcasiu D, Hartmann JF. Osteoadsorptive bisphosphonate derivatives of fluoroquinolone antibacterials. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2338–2341. doi: 10.1021/jm0105326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang JB, Yang CH, Yan XM, Wu XH, Xie YY. Novel bone-targeted agents for treatment of osteoporosis. Chin Chem Lett. 2005;16:859–862. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blower P. Towards molecular imaging and treatment of disease with radionuclides: The role of inorganic chemistry. Dalton Trans. 2006:1705–1711. doi: 10.1039/b516860k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogawa K, Mukai T, Inoue Y, Ono M, Saji H. Development of a novel 99mTc-chelate-conjugated bisphosphonate with high affinity for bone as a bone scintigraphic agent. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:2042–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torres Martin de Rosales R, Finucane C, Foster J, Mather SJ, Blower PJ. 188Re(CO)3-dipicolylamine-alendronate: A new bisphosphonate conjugate for the radiotherapy of bone metastases. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:811–815. doi: 10.1021/bc100071k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaheer A, Lenkinski RE, Mahmood A, Jones AG, Cantley LC, Frangioni JV. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging of osteoblastic activity. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1148–1154. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Årstad E, Hoff P, Skattebøl L, Skretting A, Breistøl K. Studies on the synthesis and biological properties of non-carrier-added [125I and 131I]-labeled arylalkylidene isphosphonates: Potent one-seekers for diagnosis and therapy of malignant osseous lesions. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3021–3032. doi: 10.1021/jm021107v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ehrick RS, Capaccio M, Puleo DA, Bachas LG. Ligand- modified aminobisphosphonate for linking proteins to hydroxyapatite and bone surface. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;19:315–321. doi: 10.1021/bc700196q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uludağ H. Bisphosphonates as a foundation of drug delivery to bone. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:1929–1944. doi: 10.2174/1381612023393585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doschak MR, Kucharski CM, Wright JEI, Zernicke RF, Uludağ H. Improved bone delivery of osteoprotegerin by bisphosphonate conjugation in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Mol Pharmaceut. 2009;6:634–640. doi: 10.1021/mp8002368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kieczykowski GR, Jobson RB, Melillo DG, Reinhold DF, Grenda VJ, Shinkai I. Preparation of (4-amino-1-hydroxybutylidene)bisphosphonic acid sodium salt, MK-217 (alendronate sodium). An improved procedure for the preparation of 1-hydroxy-1,1-bisphosphonic acids. J Org Chem. 1995;60:8310–8312. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chebbi I, Migianu-Griffoni E, Sainte-Catherine O, Lecouvey M, Seksek O. In vitro assessment of liposomal neridronate on MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Int J Pharm. 2010;383:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodan GA, Fleisch HA. Bisphosphonates: Mechanisms of action. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2692–2696. doi: 10.1172/JCI118722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koutsoukos P, Amjad Z, Tomson MB, Nancollas GH. Crystallization of calcium phosphates. A constant composition study. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:1553–1557. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nancollas GH, Tang R, Phipps RJ, Henneman Z, Gulde S, Wu W, Mangood A, Russell RGG, Ebetino FH. Novel insights into actions of bisphosphonates on bone: Differences in interactions with hydroxyapatite. Bone. 2006;38:617–627. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleisch H. Bisphosphonates: mechanisms of action. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:80–100. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.1.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodan GA. Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:375–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roelofs AJ, Thompson K, Gordon S, Rogers MJ. Molecular mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates: Current status. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6222s–6230s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Segal E, Pan H, Ofek P, Udagawa T, Kopečková P, Kopeček J, Satchi-Fainaro R. Targeting angiogenesis-dependent calcified neoplasms using combined polymer therapeutics. PloS ONE. 2009;4:e5233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segal E, Pan H, Benayoun L, Kopečková P, Shaked Y, Kopeček J, Satchi-Fainaro R. Enhanced anti-tumor activity and safety profile of targeted nano-scaled HPMA copolymer-alendronate-TNP-470 conjugate in the treatment of bone malignances. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4450–4463. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneider L, Korber A, Grabbe S, Dissemond J. Influence of pH on wound-healing: A new perspective for wound-therapy? Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;298:413–420. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teitelbaum SL. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289:1504–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu S, Krämer M, Haag R. pH-Responsive dendritic core-shell architectures as amphiphilic nanocarriers for polar drugs. J Drug Target. 2006;14:367–374. doi: 10.1080/10611860600834011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kale AA, Torchilin VP. Design, synthesis, and characterization of pH-sensitive PEG—PE conjugates for stimuli-sensitive pharmaceutical nanocarriers: The effect of su stitutes at the hydrazone linkage on the pH sta ility of PEG PE conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:363–370. doi: 10.1021/bc060228x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawant RM, Hurley JP, Salmaso S, Kale A, Tolcheva E, Levchenko TS, Torchilin VP. “SMART” drug delivery systems: Dou le-targeted pH-responsive pharmaceutical nanocarriers. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:943–949. doi: 10.1021/bc060080h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prommer EE. Toxicity of bisphosphonates. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:1661–1665. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.9936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lazebnik YA, Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Poirier GG, Earnshaw WC. Cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature. 1994;371:346–347. doi: 10.1038/371346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pan H, Kopečková P, Wang D, Yang J, Miller S, Kopeček J. Water-soluble HPMA copolymer—prostaglandin E1 conjugates containing a cathepsin K sensitive spacer. J Drug Targeting. 2006;14:425–435. doi: 10.1080/10611860600834219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]