Abstract

Cancers of the colon are most common in the Western world. In majority of these cases, there is no familial history and sporadic gene damage seems to play an important role in the development of tumors in the colon. Studies have shown that environmental factors, especially diet, play an important role in susceptibility to GI tract cancers. Consequently, environmental chemicals that contaminate food or diet during its preparation becomes important in the development of GI cancers. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are one such family of ubiquitous environmental toxicants. These pollutants enter the human body through consumption of contaminated food, drinking water, inhalation of cigarette smoke, automobile exhausts, and contaminated air from occupational settings. Among these pathways, dietary intake of PAHs constitutes a major source of exposure in humans. Although many reviews and books on PAHs and their ability to cause toxicity and breast or lung cancer have been published, aspects on contribution of diet, smoking and other factors towards development of digestive tract cancers and strategies to assess risk from exposure to PAHs have received much less attention. This review, therefore, focuses on dietary intake of PAHs in humans, animal models, and cell cultures used for GI cancer studies along with epidemiological findings. Bioavailability and biotransformation processes, which influence the disposition of PAHs in body and the underlying causative mechanisms of GI cancers, are also discussed. The existing data gaps and scope for future studies is also emphasized. This information is expected to stimulate research on mechanisms of sporadic GI cancers caused by exposure to environmental carcinogens.

Keywords: benzo(a)pyrene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, colon cancer, adenomas, polyps, tumors, dietary fat, metabolism

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers in the Western world. In the United States alone, nearly 108,070 new cases of CRC have been diagnosed and 49,960 deaths were attributed to this cancer (1). Occurance of colon cancer can be either hereditary (familial) or sporadic. Of the familial forms of CRC, (a) familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP; associated with germ line mutations in genes such as Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) and, (b) hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC; associated with DNA mismatch repair enzymes) are the most common. FAP cancer is inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder. Individuals with FAP develop large numbers of adenomas in their colon and rectum during their late teens or early twenties. The adenomas are capable of progressing to carcinomas, becoming invasive and producing liver metastases. The gene responsible for FAP has been identified and designated as APC gene (2,3). Sporadic CRC has the same genetic etiology as FAP but the mutations in the APC gene are somatically acquired during the life of an individual. Sporadic gene damage seems to play an important role in the development of tumors in colon as in 90% of the colon cancer cases (4); there is no familial history of colon cancer. Dietary factors and environmental agents have been suspected of causing sporadic gene mutations and therefore involved in the induction of sporadic colon carcinomas (4).

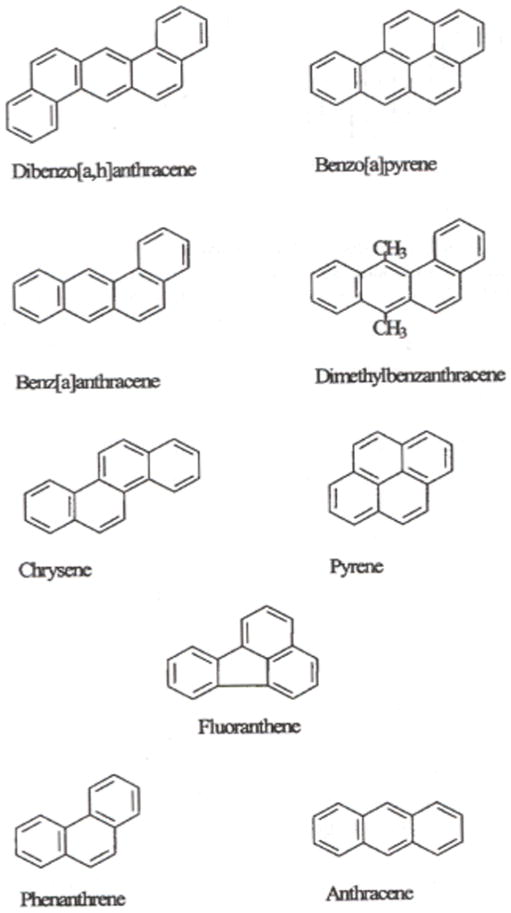

Epidemiological studies have shown that environmental factors, particularly diet, play an important role in colon cancer susceptibility (5,6). It is estimated that diet contributes to 80% of the known colorectal cancer cases (7). In this context, understanding the role of environmental chemicals that contaminate food or diet during its preparation, towards the development of gastrointestinal tract cancers, is important. Though several environmental chemicals have been implicated as the contributing factors to CRC in humans, one group of chemicals, the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs; Fig. 1) have generated the most interest as they are formed in red meat cooked at high temperatures (8-10). Not only are these chemicals formed during cooking at high temperatures (11), but also contaminated from several environmental sources (12), thus making PAHs a single large family of compounds that have the potential to contribute significantly to dietary contamination, human intake and development of CRC (5,13).

Figure 1.

Some representative PAH compounds

2. Dietary intake

Humans are exposed to PAHs through several routes including air, water, food, skin contact and occupational settings. With the exception of occupational exposures, food ingestion is the major route of exposure compared to inhalation (14). Studies conducted on human exposure to benzo(a)pyrene [B(a)P], revealed that the range and magnitude of dietary exposures (2-500 ng/day) for this toxicant were larger than for inhalation (10-50 ng/day; 15-17).

PAH contamination of food arises from a number of sources, including environment; and food processing techniques; and methods used for analysis. Unprocessed food consists of vegetables, fruits, grains, vegetable oils, dairy products, and seafood. For plants (leafy vegetables and tubers), uptake through atmosphere and soil are prime sources of PAH contamination. The accumulation of PAHs in foods of animal origin, especially livestock, is due to consumption of contaminated pasture and vegetation (18). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in fish and shellfish are a result of contamination of fresh and coastal waters. Processed food (through smoking; 19) and cooked food (charcoal cooked; 20) also contribute substantially to the intake of PAHs. The type of cooking, cooking temperature, time, amounts of fat, and oil influence the formation of PAHs (21-22). Grilled vegetables contain high PAH concentrations due to pyrolysis of organic matter at high temperatures (23).

The concentrations of PAHs found in products of plant and animal origin have extensively been reviewed in Ramesh et al (24). Global dietary intake of PAHs is shown in Table 1. The intake ranged from 0.02 to 3.6 μg/person/day. The variety of food items considered for intake estimation, analytical methods and the PAHs used for computing dietary intake varied. Among the variety of foods that contributed to high PAH intake are red meat, fats, oils, cereals and vegetables.

Table 1. Estimated dietary intakes of PAH for various countries (12; with permission).

| Country | Estimated intake (μg/person/day) |

|---|---|

| Australia* | 0.03 |

| Austria | 0.39 |

| Brazil | 2.90 |

| China | 3.56 |

| Czech Republic | 0.19 |

| Denmark | 0.02 |

| Finland | 2.34 |

| France | 0.09 |

| Germany | 0.19 |

| Greece | 0.005 |

| India+ | 11.0 |

| Italy* | 0.2 |

| Japan* | 0.09 |

| Netherlands | 0.52 |

| Newzealand* | 0.16 |

| Nigeria*# | 6.0 |

| Norway | 0.02 |

| South Korea# | 1.10 |

| Spain | 0.11 |

| Sweden | 0.08 |

| U.K. | 0.06 |

| U.S.A. | 0.05 |

Data pertain to benzo(a)pyrene intake only.

Data was collected from intake of cooking oils.

Data was collected from consumption of fish & other seafood items only.

3. Epidemiological studies

Epidemiological studies also have shown that environmental factors play an important role in GI cancer susceptibility. An association between ingestion of PAHs and esophageal cancer (esophageal squamous cell carcinoma) has been reported from Iran (25) and China (26). The Iranian study detected 1 hydroxypyrene glucuronide (a stable metabolite of PAHs) in 83% of the subjects. The Chinese studies detected greater concentrations of PAH-DNA adducts (26), and elevated aryl hydrocarbon receptor gene expression (27) in esophageal cell samples from patients compared to healthy control subjects. While increase in environmental pollution by PAHs has been attributed to esophageal cancer in Iran, high levels of carcinogenic PAHs in food (28), and indoor air pollution (domestic heating with coal) have been implicated as the causative factors for esophageal cancer in China.

Though laboratory studies pointed towards the likelihood of PAHs causing gastric cancer, epidemiological studies present contrary evidence. A large prospective study tried to examine the relationships between red meat intake and the risk of esophageal and gastric cancer (29). This study used 215 esophageal squamous cell carcinomas, 603 esophageal adenocarcinomas, 454 gastric adenocarcinomas, and 501 gastric non-cardia adenocarcinomas. The food intake, meat cooking methods and intake of B(a)P was assessed using a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ; 30-32). While a positive association was noted between red meat intake and esophageal and gastric carcinomas, interestingly B(a)P intake through meat was not found to be associated with esophageal or gastric cancer.

Epidemiological studies showed that the evidence for an interaction between fatty diet or red meat and PAH intake, and CRC development is inconsistent. Findings from a clinic-based case-control study bolster the hypothesis that dietary intake of PAHs is associated with CRC risk (30). This study created a B(a)P (as a surrogate for PAHs) database using a wide range of food items and linked it to a FFQ. Increased risk of colorectal adenomas with high intake of B(a)P was found from total diet and from meat intake only. Using the same study design and a sample size of about 4,000 adenoma cases, this research group (31) also showed that consumption of well-done red meat was associated with increased risks for adenoma of the descending colon and sigmoid colon for B(a)P. Hence it is conceivable that CRC are promoted by the increased intake of PAHs through dietary fat. Similar to the above mentioned studies, another sigmoidoscopy based study (275 CRC cases and 312 controls) reported an association among high intake of barbecued red meat, B(a)P, and colorectal adenomas (33).

On the other hand, findings from a population-based case control study do not support the hypothesis that dietary B(a)P consumption is a risk factor for CRC (34) This study used 567 CRC cases and 713 controls. The meat consumption data was linked to the Computerized Heterocyclic Amines Resource for Research in Epidemiology of Disease (CHARRED) data base carcinogen data base (35). The shortcoming in this approach was that despite high meat intake by the Australians compared to the American subjects, B(a)P values for fish and lamb was not available in CHARRED data base. Hence B(a)P values for skinless chicken was used in this study in lieu of fish and lamb because of a similar fat content. Therefore, proper estimations of dietary and non-dietary exposure help accurately assess the risk of exposure to PAHs through diet. In another large prospective cohort study that included around 2,000 colon cancer cases, no positive association between B(a)P exposure through meat consumption and CRC was noted (36). Also, in asymptomatic women undergoing colonoscopy, even though colorectal adenomas were associated with high intake of red-and pan-fried meat, there was no evidence of adenomas being associated with intake of B(a)P (37). In one colonoscopy-based case control study (1,028 polyp cases and 1,544 polyp-free controls) intake of PAHs and heterocyclic amines (HCA) through red meat was associated with colorectal adenomas, but the association was significant more so with HCAs than PAHs (38). Additionally, in a study that involved 772 subjects, consumption of charred meat was found to have an association with hyperplastic polyps, but not adenomas in the colon (39). These paradoxical findings call the need for more epidemiological studies in different regions of the world recruiting subjects with varied dietary habits to test the strength of association between PAHs and colorectal cancer development.

Some of the aforementioned studies have demonstrated an association between intake of red meat and the development of colorectal adenomas. Therefore, interest has been directed at using PAH-DNA adducts as biomarkers of CRC risk. Monitoring of PAH-DNA adducts have advantages in that a) these adducts provide a measure of the biologically effective dose of B(a)P; b) they serve as a biomarker for molecular epidemiology studies geared towards determining the cancer risk (40,41). Aside from the food consumption and colonoscopy-based case control studies, a consistent association between recent consumption of barbecued or grilled meats and increased PAH-DNA adduct concentrations in human peripheral white blood cells (WBC) of humans was noted (42,43). Dietary PAHs from charbroiled meats were found to elevate the concentrations of PAH-DNA adducts in WBC and excretion of 1-hydroxypyrene in urine in a dose-dependent manner.

To test the concept whether the presence of DNA adducts could serve as biomarkers of the etiology of colon cancer, Al-Saleh et al. (44) conducted a small scale case control study (24 cancerous and 20 noncancerous tissues) in colon cancer diagnosed patients. Even though DNA adducts were presumed to have arisen from PAHs and/or HCAs, the identity of adducts could not be established. Nevertheless, this study brought into light that adduct identity is an important factor for the early detection of colon cancer in susceptible individuals necessitating the need for conducting surveillance strategies such as dietary modifications and therapeutic interventions (45).

4. Mechanism of action

Metabolism plays an important role in the conversion of chemical carcinogens into reactive species that damage cellular macromolecules, interfere with signaling pathways and cause cancer (46). Human colon cells were known to metabolize PAHs. Different types of colon tumor cell lines such as Caco-2; HT29; HT-116, and SW 486 (human cell lines), rat small intestinal epithelial cells and rat colonocytes were used to study PAH metabolism in colon. The PAH concentration used in these studies ranged from 10nM to 200μM (47-54). In addition to cell cultures, organ cultures of esophagus, duodeneum, and colon from patients have been reported to metabolize PAHs (55,56). Microsomes from human gastric mucosa with metaplasia were also reported to metabolize B(a)P (57).

Aspects pertaining to bioavailability and biotransformation of PAHs; genomic and oxidative DNA damage caused by PAHs to target tissues have been the subject of numerous review articles, book chapters and monographs. Interested readers may refer to the reviews in Penning (58), ATSDR (59), Ramesh et al. (24), Luch (60), Shimada (61), Shimada and Guengerich (62), and WHO (63).

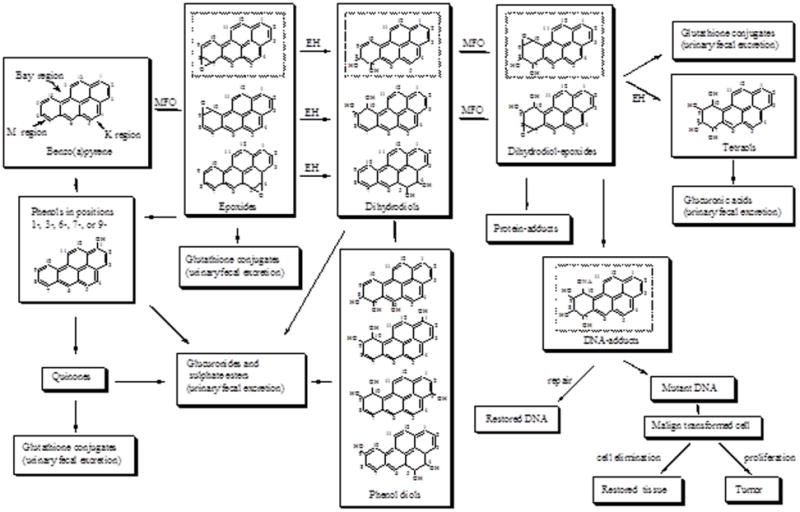

The arylhydrocarbon receptor (Ahr), a transcription factor activated by ligands such as PAH whose signaling plays an important role in regulation and induction of several drug metabolizing enzymes such as CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP1B1, glutathione S-transferase, UDP-glucoronyltransferase, quinone oxidoreductase, etc. (64-67). These enzymes process toxicants to reactive metabolites that interact with cellular macromolecules contributing to toxicity or carcinogenesis. This process is schematically illustrated in Fig. 2. Using Ahr (+/+) and Ahr (−/−) mice, Shimada et al. (68) showed induction of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1 in Ahr (+/+) mice.

Figure 2.

Schematic of B(a)P metabolism. From Ramesh et al (24); with permission.

Liver is the major organ for metabolism of PAHs. However, extrahepatic organs such as GI tract, spleen, lung, heart etc may play a greater role. Several cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of PAH compounds are given below.

CYP1A1: this enzyme is capable of metabolizing a wide spectrum of PAHs. The constitutive expression of this enzyme is low in tissues (69). The induction of CYP1A1 is controlled by the Ahr (arylhydrocarbon). This indicates that individual PAH compounds or mixtures can regulate their own metabolism by inducing CYP1A1. After induction, the level of CYP1A1 expression reaches high in extrahepatic tissues (70, 71), but in liver, the level of expression is low.

CYP1A2: the capacity of this enzyme to metabolize PAHs is less than that of CYP1A1. Nevertheless, this enzyme has been reported to metabolize BaP to 3-hydroxy BaP and 7,8-dihydrodiol to its epoxides in rodents (72) and humans (73).

CYP1B1: this enzyme has been reported to act on a number of PAHs (74) and expressed in rodents (75-78), goat (79) and human (80-82) tissues.

The intestinal epithelium contains all the enzymes involved in PAH activation and detoxification, although these activities are generally much lower than in the liver (83). The low levels of inducible CYP isozymes in the intestinal tract could influence the occasional development of tumors in the small and large intestines as a consequence of the ingestion of PAH-containing food (84). Colon tissues have been reported to express CYP enzymes though at a low level (85). Additionally, colon tissues have been shown to express prostaglandin H synthase (COX; 86). Of relevance to this context is the report that B[a]P and its metabolites not only induce the expression of COX-2, but also function as substrates for COX-2 (87). Human COX-1 and COX-2 have been reported to activate B[a]P 7,8-diol to intracellular electrophiles (88). Thus, the activation of B[a]P/its metabolites by COX isozymes is relevant to colorectal carcinogenesis as this region of the digestive tract receive exposure to PAHs through diet.

In vitro studies were conducted by Lampen et al. (89) to investigate the mechanism of interplay between PAH drug metabolizing enzymes and ATP-binding transport (ABC)-proteins in human Caco-2 cells. Treatment of these cells with B(a)P, chryene, phenanthrene, benzo(a)fluoranthene, dibenzo(a,b)pyrene, and pyrene induced mRNA expression of CYP1A1, CYP1B1, epoxide hydrolase and UDP-gluceronyl transferase, and also the ABC-transport protein MBR1. These results suggest that intestinal cells were capable of generating PAH metabolites, which are transported by ABC-transport proteins.

Benzo(a)pyrene induces the expression of bioactivation enzymes in liver to a greater extent than detoxifying enzymes (90). Our earlier observations in F-344 rat model revealed that dietary exposure to B(a)P resulted in higher induction of aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase activities in liver (66). Additionally, studies conducted earlier by Sattar et al. (91) also revealed no change in GST levels and activities in adenomas and normal tissues of the small intestine of ApcMin mouse treated with 100 mg/kg B(a)P through corn oil.

The induction of CYP1A1 via the AhR is important to the carcinogenic effects of B(a)P. In vivo exposure of AhR deficient mice to B(a)P resulted in the inability to induce CYP1A1 mRNA or CYP1A1 protein (92). These findings emphasize the necessity of an active AhR to sustain the transcriptional activation of CYP1A1. Exposure to B(a)P induced expression of CYP1A1 mRNA in liver of AhR (+/+) and (+/-) mice, but not in AhR (-/-) mice (93). In these studies exposure to B(a)P resulted in tumor formation only in AhR (+/+) and (+/-) mice. These studies provide evidence of the involvement of AhR in the carcinogenesis of B(a)P.

Expression of CYP1B1 cannot be overlooked as it an important drug metabolizing enzyme (DME) in extrahepatic tissues (reviewed in 24) and hence is assumed to contribute significantly to the B(a)P metabolite load in the body. Its role in metabolic activation of B(a)P-7,8-diol to the ultimate carcinogen benzo(a)pyrene-diol epoxide (BPDE; (94) may play a key role in the neoplastic transformation of adenomas in the ApcMin mouse colon.

Studies of Uno et al., (95-98) have ascribed the role of CYP1A1 to detoxication than metabolic activation. When CYP1A1 (-/-) global knockout mice were exposed to 1.25 mg/kg/day of B(a)P, they survived for 4 to 5 months, while the CYP1A1 (+/+) wild type mice survived for a year (97). On the other hand, when these groups of mice received 125 mg/kg/day of B(a)P, the knockout mice lived for 18 days, while their counterparts survived for one year (98). Additionally, the studies of Uno et al. (95) and Shi et al. (97) have shown that small intestinal CYP1A1 processes much of the B(a)P, before it reaches the liver for the CYP1A1 in liver tissues to be induced. These studies revealed that while CYP1A1 is required for detoxication, CYP1B1 is needed for metabolic activation. Immunohistochemistry studies conducted by Uno et al. (99) also were in favor of this proposition. These studies informed that CYP1A1 is localized throughout the mice small intestine, and being in close proximity to lumen than CYP1B1, could effectively process B(a)P during its residence in intestine. A similar localization of CYP1B1 in the large intestine cannot be ruled out. Ultimately, the balance between CYP1A1 and 1B1 determine the long-term consequences of metabolic activation versus detoxication processes in the initiation of carcinogenesis.

The toxicities caused by PAHs are due to interference with cellular signal transduction pathways within the cell (100). Several signaling pathways are related to CYP1A1 induction by various chemicals (101). Benzo(a)pyrene also has been reported to influence the nitrogen activated protein (MAP)-kinase in HT29 colon adenocarcinoma cells (102) This signaling pathway controls cell proliferation and apoptosis. Low concentrations of B(a)P (10nM) was also found to activate extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), which in turn contributes to an increased activity of the detoxification enzyme NAD(P)H: Quinone reductase (102).

Protein kinase C (PKC) activity is required for Ahr-mediated signal transduction. Benzo[a]pyrene was reported to inhibit PKC activity in vascular smooth muscle cells in a concentration-dependent manner. A comparable response was seen with 3-OH B[a]P, indicating that oxidative metabolites of the parent PAH compounds are capable of modulating the PKC activity (103). Similarly, tyrosine kinase activation may influence CYP1A1 induction (116). PAHs were reported to activate src family-associated protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) Lck and Fyn in T cells that initiate phospholipase Cγ 1 activation, the production of 1,4,5-inositol triphosphate, and the release of Ca2+ from intracellular storage pools in the endoplasmic reticulum (104). PAHs also inhibit the reuptake of Ca2+ into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPases (105). These findings indicate that alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis may be responsible for the immunotoxic effects of PAHs. Recent studies (120) have shown that DMBA-induced bone marrow toxicity is dependent on tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor (TNFR) and double-stranded RNA–dependent protein kinase (PKR). Further, Page et al. (106) have demonstrated that PKR is activated by TNFR-mediated signaling. The changes in intracellular calcium flux due to PAH exposure may have partly contributed to the upregulation of PKR (107).

Epigenetic processes may cause changes in gene expression without altering gene sequences (108). In other words, a cell phenotype is determined by not only the genotype, but also the epigenotype that is molded by environmental exposures (109). These processes therefore determine the susceptibility to disease. Spontaneous or environmentally-induced epigenetic changes become the centerpiece in the early molecular events in carcinogenesis (110). Alterations in DNA methylation is one of the epigenetic changes that has been implicated in the malignant transformation and progression of several tumor types including colon tumors (111).

Many PAHs were reported to cause epigenetic toxicity (112). Epigenetic chemicals alter the genetic phenotype of a cell is by interacting with a finite number of intracellular biochemical pathways that turn genes on and off. These intracellular pathways involve intercellular communication through Gap junctions (channels formed by connexin proteins that permit regulatory molecules and ions such as glutathione, cAMP, Ca+2, inositol triphosphate, etc. to pass directly between adjacent cells). Gap-junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) has been linked to the regulation of development, cellular proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (112). GJIC function is regulated by the extracellular receptor kinases (ERK), a class of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK; 113). While low-molecular weight PAHs (fluorene, phenanthrene, fluoranthene, and their methylated derivatives) were strong inhibitors of GJIC, high molecular weight PAHs (B[a]P, dibenzo[a,e]pyrene, and dibenzo[a,h]pyrene) were found to be weak inhibitors (113,114).

5. Pathology

Epidemiological studies have already established an association between consumption of diet rich in fat and incidence of CRC in human populations. However, studies in animal models are necessary a) to support or contradict the epidemiological data, b) to replicate phenotypic manifestation of the disease most similar to that of humans, and c) to identify the mechanistic underpinnings of environmentally-induced colon cancers. Eventually, the model developed must be reliable, robust, and be able to yield consistent data over a specified period of time (115,116).

Because of the prevalence of B(a)P in the environment and the great potential for human exposure, studies have been conducted to see the pathological changes that ensued following oral B(a)P treatment using several rodent models. Some of the models used were B6C3F1 mouse (117), big blue mouse (118), ApcMin mouse (119-124) and Wistar rat (125). Chemically-induced rodent models help in unraveling the influence of dietary and environmental factors on carcinogenesis, individually and in combination (126). The high incidence of tumors formed in the distal colon of mice and the sequential development of adenomas to adenocarcinomas make the murine models ideal to recapitulate colon carcinogenesis in humans (127). Of all the murine models, ApcMin is widely used in recent years to study the onset and progression of gastrointestinal cancers. This is a mutant mouse with multiple intestinal neoplasias (Min; 128). It has a mutated adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc), a tumor suppressor gene, similar to that in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. In this mouse, the loss of a single copy of Apc gene predisposes the mice to the development of a large number of polyps, both in the small and large intestine (129). The ApcMin mouse mimics the rapid development of adenomatous polyps that affect humans. and these mice are used extensively as animal models for FAP and sporadic colorectal cancers (129,130). This model is ideal for evaluating the effects of diets and chemopreventive compounds on intestinal cancer initiation and progression (131-133). Second, the mice have a reduced life span (120 days) and thus age-equivalencies for human beings are achieved over a shorter period of time (134).

Most of the studies using rodents as animal models to investigate the gastrointestinal tract cancers of GI tract have placed emphasis on the number of tumors present in the small intestine as primary endpoint (135) and tumor incidences in colon have been overlooked as evident from the following studies. Oral administration of B(a)P through gavage and diet in doses ranging from 0.1 mg to 30 mg/kg body weight in mice and rats (transgenic and lab-bred species) over varied periods of time (few weeks to two years) revealed tumor development on tongue, oesophagus and forestomach. The tumors were characterized as cell papillomas and adenomas with sporadic incidence of carcinomas as well (125,136-138). Intracolonic administration of 1 mg B(a)P/kg body weight in mice over 14 weeks of exposure period produced only papillomas in the forestomach (139). The A/J mice, which ingested 6 or 98 ppm of B(a)P through diet developed forestomach tumors (137). Intraperitoneal dose of 100 mg/kg B(a)P has been reported to cause adenomas in the small intestine of ApcMin mice (106). The ICR mice orally gavaged with 3 mg B(a)P twice weekly for 4 weeks showed an increased number of papillomas and carcinomas in forestomach (140). Perhaps, these variations are largely due to differences in choice of animal model, dose, and route of administration and duration of exposure.

The disparity in outcomes of oral B(a)P-induced carcinogenesis in the GI tract notwithstanding, evidence regarding the ability of PAHs to induce colon carcinogenesis also comes from studies where PAHs were administered through varied routes employing different animal models. Reports of Della Porta (141) and Honburger et al. (142) showed that oral and intragastric administration of methylcholanthrene a PAH compound caused an increase in colorectal tumors in hamsters. Intrarectal administration of 1 mg B(a)P/kg body weight caused cytotoxicity in the colon of C57BL/6 mice (143). A single intrarectal administration of 0-200 mg B(a)P/kg body weight caused nuclear damage in colonic epithelium of C57BL/6J mice (144). Similarly, intrarectal administration of 0.8 mg B(a)P or 3-methylcholanthrene/kg body weight for 30 weeks produced adenocarcinomas in the colon (145). El-Bayoumy et al. (146) reported adenoma and adenocarcinoma in colon of Sprague Dawley rats, which received 250 μmol 1-nitropyrene/kg body wt. via oral gavage. Imaida et al. (147) documented adenomas and adenocarcinomas in colon of Crj:CD rats, which received 14.8 μmol 6-nitrochrysene/rat intraperitoneally. Tsubura et al. (148) found adenocarcinomas in the colon of Japanese house musk shrew subsequent to 1-2 times exposure to 10 mg 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) for 4 and 8 weeks respectively, via intraperitoneal route. Tudek et al. (149) reported the dose-dependent development of aberrant crypt foci in CF1 mice 3 weeks after oral B(a)P treatment. A single intragastric application of 50 mg DMBA/kg bw in Sprague Dawley rats produced aberrant crpt foci in colon (150). Male B6C3F1 mice dosed with 0.19 -0.76 mmol /kg B(a)P, DMBA, and benzo(b)fluoranthene showed nuclear anomalies in the colon (151). Intraperitoneal administration of 100 μg/kg B(a)P and DMBA produced polyps in the colon of ApcMin mice (152). The λlacZ transgenic mouse (Muta™ Mouse), which received 125 mg B(a)P/kg body wt. orally for 5 consecutive days (153,154) to 2 weeks (155) also registered high rates of mutation in colon. Hakura et al. (156) reported multiple polyps in a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis model of Crj:CD2F1 mice treated with 125 mg BaP/kg bw/day for 5 days followed by 4% DSS for 2 weeks.

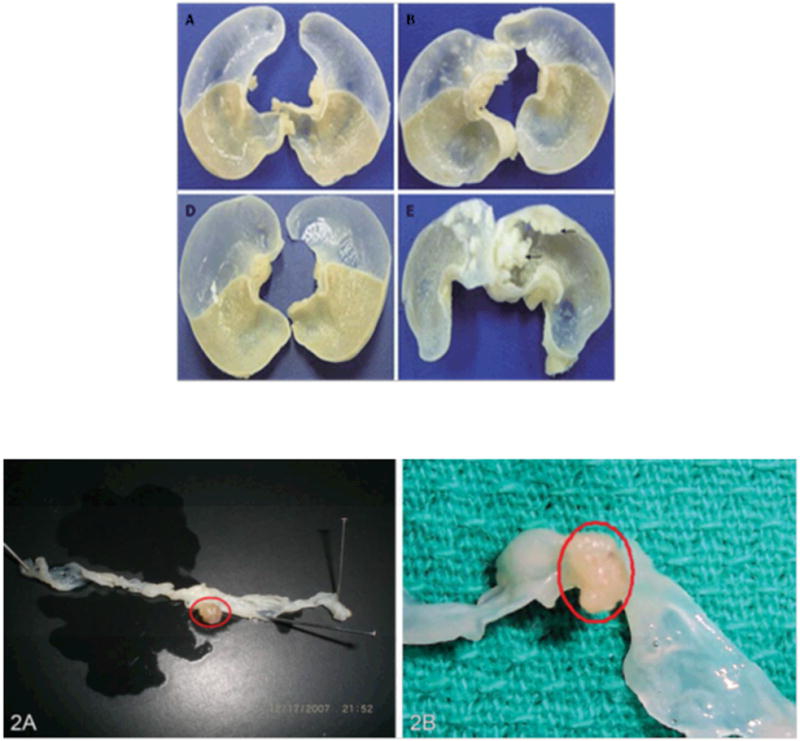

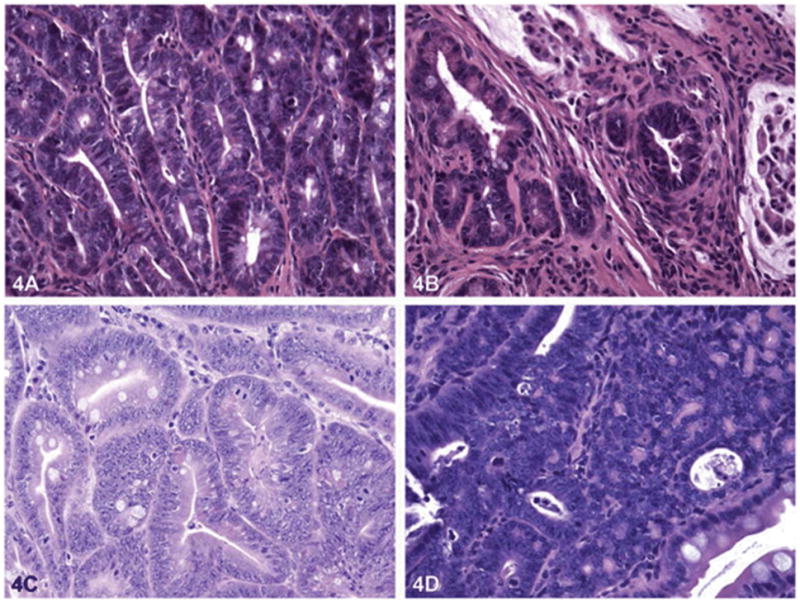

The phenotypical manifestations of pathology in the GI tract of animal models appeared as small nodules or polyps, which are depicted in Figure 3. The tumors in the forestomach of ICR mice treated with BaP initially appeared as small rash-like tumor nodules. However, 16 and 32 weeks after BaP administration (3mg/kg twice weekly for 4 weeks), the nodules showed significant growth (140). The pathological alterations in tumor nodules include papilloma and squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

A. Representative forestomach tumors (arrow) in BaP-treated mice. Mice were sacrificed at wk 16 (A, B) and wk 32 (D, E) after the first administration of benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) in control mice (A and D), BaP + IgG-treated mice (B and E). The size and volume of forestomach carcinoma is more compared to controls. From Chen et al (140); with permission.

B. Representative tumors in the colon of ApcMin mouse treated with (A) 50 mg B(a)P/kg body weight and (B) 100 mg B(a)P/kg bodyweight. Mice were sacrificed 60 days after exposure to B(a)P via oral gavage. The number of polyps increased with B(a)P in saturated fat compared to unsaturated fat. The tumors were located in the distal colon near the rectum and measured >5 mm. From Harris et al (124); with permission.

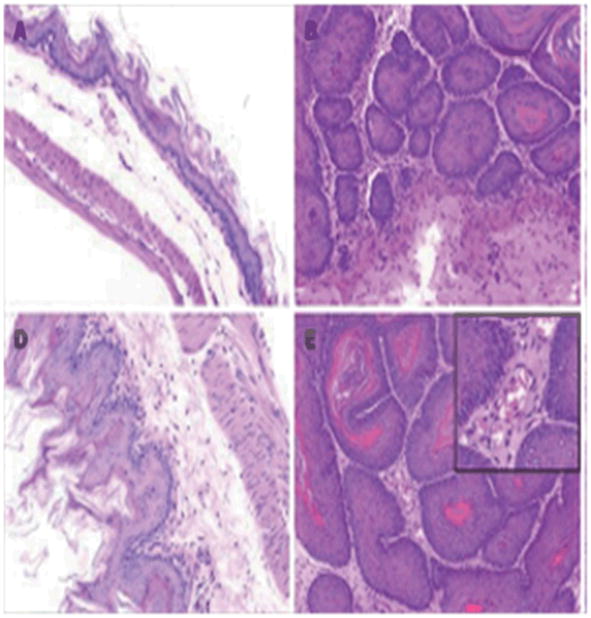

Figure 4.

Histology of forestomach carcinoma in mice. Mice were sacrificed at wk 16 (A, B) and wk 32 (D,E) with their stomachs excised. The number of squamous cell carcinomas was increased in BaP + IgG-treated-mice. A and D: control mice; B and E: BaP + IgG-treated mice. From Chen et al (140); with permission.

In the proximal small intestine of CYP knockout mice treated with BaP (12.5mg/kg/day for 4, 8, 12 and/or 16 weeks through diet), both intraepithelial and invasive neoplasia was seen (113). Progression of lesions from invasive to metastatic carcinoma was also noted.

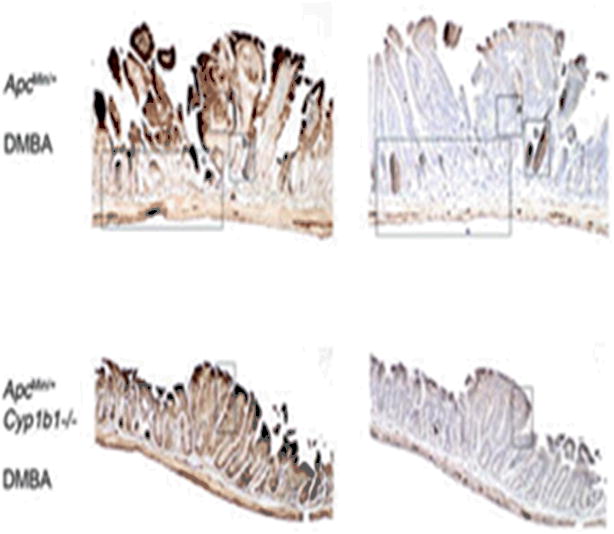

The transgenic Apc Min+ and CYP1b1 deficient Apc Min mice (Apc Min/+, CYP1b1-/-) administered with DMBA and BaP (0.1mg/kg on days 28 and 35 intraperitoneally) presented adenomatous polyps (152). The mice that lacked CYP1b1 presented few tumors compared to the ones that had. The tumors from Apc Min/+, CYP1b1-/- exhibited enlarged tumors with disorganized growth and nuclear atypia (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of Cyp1b1 deletion and DMBA treatment on the histology of Min tumors at days 55 and 130. Mice were sacrificed at either 55 d of age (A and B) or 130 d of age (C). Tumors were isolated from day 55 oil-treated Min and Cyp1b1-deficient Min control mice (A), day 55 DMBA-treated Min and Cyp1b1-deficient Min mice (B) Sections were stained with H&E (column 3 insets) or β-catenin (left), phospho-IKK (p-IKK; middle). From Halberg et al (152); with permission.

Most of the polyps observed in the jejunum, colon of Apc Min mice subsequent to BaP treatment (50 and 100μg/kg BaP daily for 60 days through oral gavage) were adenomas (also termed as adenomatous polyps) with low to high-grade dysplasia (61). Few invasive adenocarcinomas were also seen (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pathology of polyps in the jejunum and colon and in liver tissue of an ApcMin mouse treated with 100 μg B(a)P/kg bw for sixty days via oral gavage in saturated fat. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the jejunum of control (A) mice (40×) show small adenomas with no high grade dysplasia. Jejunum of B(a)P-treated mice (B) [40×] show invasive carcinoma. The colons of control mice (C) [40×] show small adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, whereas colons of B(a)P-treated mice (D) [40×] show large adenoma with high-grade dysplasia. B(a)P, benzo(a)pyrene. From Harris et al (124); with permission.

In a colitis mouse model mentioned above, Hakura et al. (156) reported many modular papillary or polypoid masses in colon. These masses were classified as tubular adenomas or adenocarcinomas. Invasion of adenocarcinomas into lamina propria was seen in some cases but not into submucosa. Also, metastasis was not observed in these studies.

6. Modifying factors

Dietary fat

Both content and type of fat in diet have been reported to promote the development of colon tumors. Rats and mice that received a high-fat diet developed more colon tumors compared to controls that received a low-fat diet. Intake of fatty diet has been associated with colon cancer (157). The Apc∆ 716 knockout mice fed a low fat diet developed 36% fewer polyps in the small intestine and 64% fewer polyps in the colon, compared to mice that were fed a high-fat diet (158). Similar results were obtained with ApcMin mice. Mice that received high (15%) fat in the diet registered more polyps in the small and large intestine compared to mice that received standard (3%) fat (159). Beef meat (24%)- fed rats for 5-6 weeks were reported to show 3.2 adenomas compared to 1.8 in controls (a treatment effect of 178%; 160). In another study, the Apc1638 mice when fed for about 32 weeks, with a Western-style diet that was high in fat, a significantly greater number of mice developed adenomas than mice fed with a standard diet (65% vs 13%; 161). ApcMin mice placed on a high fat Western style diet developed tumors in the large intestine (162). On similar lines, Newmark et al. (163) developed a Western diet using which, the C57BL/6 mice developed hyperproliferative and hyperplastic colonic epithelium 4 months after administration and colon tumors in 18-24 months after administration.

Regardless of the presence of carcinogen, fat itself has been shown to have a tumor promoting effect (164,165). Increased intake of saturated fats has been associated with increased lipid peroxidation (166) and oxidative damage (167) in rat liver and colon. Additionally, lipids have been reported to modify the cell membrane structure and function, cell signaling pathways and gene expression and modulate the immune system function (168). Studies conducted by our research group revealed that fluoranthene, a PAH compound damages DNA in several target tissues when administered through saturated fat in F-344 rats (169). Therefore, the question that arises quite naturally is whether the animal models used for PAH carcinogenesis studies can develop colon tumors when they are given unsaturated and saturated fat via oral gavage in the absence of exogenous PAHs. This aspect has been looked into by Harris et al (124), who have encountered colon tumors, some of them were invasive, in mice that received unsaturated and saturated fats. However, their numbers were statistically insignificant compared to the mice that received B(a)P through saturated dietary fat compared to their counterparts that received B(a)P through unsaturated dietary fat. In this context, the report of Khalil et al (170) is worth mentioning as these studies have demonstrated that PAHs exacerbate the effects of high fat diets on intestinal inflammation. Hence, the recorded tumors in ApcMin mice may be a result of increase in the production of proinflammatory cytokines as a result of interaction between PAHs and fatty diet.

Smoking

Two case-control studies of colon cancer and rectal cancer conducted in California and Utah revealed an association between people who smoked more than 20 pack-years and polymorphisms in the CYP1A1 gene (171). These studies have implicated smoking as a risk factor for colorectal cancer. Also, investigations of Morimoto et al (172), Ji et al (173), Shrubsole et al (174), Botteri et al (175), and Burnett-Hartman et al (176) have shown a strong association between smoking and colorectal cancer. Though PAHs are a component of cigarette smoke, cigarette smoke contains several thousands of toxic chemicals (177), and thus the observed incidences cannot be equivocally attributed to inhaled PAHs. Despite reports suggesting an association of early onset of smoking with adenomatous polyps in the large intestine (178-180), the association was less consistent with colon cancer (178,181). Additionally, in another large cohort study that involved 63,000 people for 18 years, no statistically significant association was seen between cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer (182). Therefore, for non-smokers, and non-occupationally exposed people, food ingestion is the major exposure pathway compared to inhalation (14).

Chemopreventive agents

The ability of orally administered B(a)P to cause forestomach tumors (papilloma and carcinomas) in mice models (117,140) has been used to study the chemopreventive effect of phytochemicals on B(a)P-induced gastric cancers (183-195). The preventive agents that were tested include pure compounds such as retinoids, carotenoids, sulforaphane, linoleic acid, budenoside, N-acetyleysteine, quercetin, kaemferol, extracts of plants such as Ginkgo biloba, Syzygium cumini, Azadirachta indica, Trachyspernum ammi, Phellinae gilvus, Vigna angularis, Alstoma scholaris, and turmeric. No mechanistic aspects were covered in a great majority of these studies except studying the activities of phase I and phase II drug metabolizing enzymes and antioxidant enzymes.

In Caco-2 cells exposed to B(a)P, the flavonoids quercetin and kaemferol have been reported to affect the expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), AhR repressor, glutathione transferases A1, P1, nuclear factor erythroid related factor (Nrf2), and glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (196). Another flavonoid, luteolin has been found to affect AhR-dependent CYP enzymes (54).

7. Data gaps and future directions

This review has briefly described the state of knowledge on GI tract cancer induced by PAHs. However, there remain many issues to be resolved in terms of the mechanisms involved. Judicious use of cell lines and animal models are expected to shed more light on these aspects. Following are some of the recommendations for future research in this area.

While sporadic colon cancers are mostly a result of exposure to environmental/dietary carcinogens, the disparities in genetic susceptibility of some individuals to environmental carcinogens merit investigation. For example, it has also been documented that the incidence of colon cancer is more in African Americans compared to other racial and ethnic groups (197). That African Americans are exposed to PAHs more so than other racial groups (198,199) begs the need for factoring genetic polymorphisms in environmental risk assessment.

Several genetic pathways have been reported to be involved in colon carcinogenesis. Some of these are summarized in the Fearon and Vogelstein (199) model, while other pathways (200) have not been elucidated in detail. Some of these pathways have been addressed in reviews of Ahmed (201,202). Expression of genes relevant to colon cancer include Mucin 2 (MVC2), tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), TNF receptor 2 (TNFR2), protein tyrosine phosphatase gene (PRL-3), WnT 2, C-Met proto-oncogene, Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (B-hCG), receptor for activated c Kinase (RAC 1), type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), ras proto-oncogenes, p53 tumor suppressors gene, differentiation related gene 1 (Drg 1), and cadherin-catenin adhesion system genes etc. How many of these genes play a role in toxicant-induced colon cancer development is not clear. More research is needed in this direction.

Diet plays a pivotal role in the development of colon cancer. In this context, the role of diets with different fat types and varying fat content on promotion of toxicant-induced carcinogenesis requires to be fully deciphered. Obesity is also another modulating factor for development of colon cancer. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are lipophilic pollutants (203). The circulating PAHs partition into adipose tissue, which serves as a reservoir for these chemicals. Relevant to this supposition is a report from Hutcheon et al. (204), which showed a positive correlation between human plasma B(a)P concentrations and body mass index. Studies in a C5FBL/6J mouse model have shown a decreased response to epinephrine-induced lipolysis upon exposure to 400 /kg BaP for 14 days (205) Mouse primary adipocytes exposed to 0-100 M BaP also were found to have inhibition of epinephrine-induced lipolysis (205). These studies advocate a role for BaP to promote obesity. Since BaP contributes to obesity as well as development of colorectal cancer, the inter relationship between obesity and PAH-induced CRC need to be explored further.

From a prevention standpoint, several phytochemicals have been proposed as effective agents against CRC. One of these compounds resveratrol, a phytoestrogen showed promising results in cell culture and animal models (206; unpublished data from our research group) More research is warranted on the pathways targeted by phytochemicals from a chemoprevention standpoint with the ultimate objective of developing less expensive and naturally available therapeutic interventions. Towards this end, we must harness the nutrional genomic and proteomic resources to the fullest possible extent, so that gene-gene and gene-environment interactions could be considered for adopting prevention strategies (207).

Even though genetic mechanisms have been recognized as the driving force behind colon tumorigenesis, epigenetic mechanisms are no less important in the promotion and progression of chemical carcinogenesis in general (208,209). Of importance in the regard are key physiological and biochemical events in cell such as apoptosis, cell proliferation, DME induction, oxidative damage and gene expression. How PAHS influence these events through epigenetic pathways and the relevance of these pathways to intestinal cancers is not clear. As recent studies have shown that epigenetic alterations could be used as biomarkers in assessing the potential of environmental toxicants to contribute to carcinogenesis (210), additional information is warranted on the ability of PAHs to contribute to GI tract carcinogenesis through epigenetic mechanisms.

The contribution of chemical carcinogens including PAHs towards the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) needs to be investigated, given the link between CRC and these diseases. The IBD comprises crohn's disease (a patchy disease that can affect the GI tract anywhere) and ulcerative colitis (a chronic inflammatory disease that extends from the anus to all or parts of the colon) [211,212] Some of the IBD patients have sort of association with CRC as CRC accounts for approximately 10-15% of all mortalities in IBD patients (213). It has also been shown that IBD accounts for only 1-2% of all cases of CRC, IBD colitis patients are 6 times more likely to develop CRC than the general population (214). Given the role gene-environment interactions play in the etiology of IBD (207), it is high time that the contributions of environmental carcinogens towards the development of IBD be investigated using animal models (211).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants 1R01CA142845-01A1 (AR), 1RO3CA130112-01 (AR), from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), 5T32HL007735-12 (ACH, DLD, JNM) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), 5R25GM059994-11 (ACH, DLD, KLH, LDB, JNM) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), 1F31ES017391-01 (DLD), 1F31ES019432-01A1 (ACH), and 5 S11ES014156 02-pilot project (AR) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) all of which are components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. Our thanks are also due to the Southern Regional Education Board, Atlanta, Georgia for a Dissertation Award to Mr. Jeremy Myers and doctoral scholar award to Ms. Kelly Harris.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute-Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (NCI- SEER) Cancer of colon and rectum. 2008 http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html.

- 2.Joslyn G, Carlson M, Thliveris A, Albertsen H, Gelbert L, Samowitz W, Groden J, Stevens J, Spirio L, Robertson M, Sargeant L, Krapcho K, Wolff E, Burt R, Hughes JP, Warrington J, Mc Pherson J, Wasmuth J, Le Paslier D, Abderrahim H, Cohen D, Leppert M, White R. Identification of deletion mutations and three new genes at the familial polyposis locus. Cell. 1991;66:601–613. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Cancer Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. American Institute for Cancer Research; Washington: 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross AJ, Sinha R. Meat-related mutagens/carcinogens in the etiology of colorectal cancer. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44:44–55. doi: 10.1002/em.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez ME. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer: lifestyle, nutrition, exercise. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2005;166:177–211. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26980-0_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bingham SA. Diet and colorectal cancer prevention. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:12–16. doi: 10.1042/bst0280012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murtaugh MA, Ma K, Sweeney C, Caan BJ, Slattery ML. Meat consumption patterns and preparation, genetic variants of metabolic enzymes, and their association with rectal cancer in men and women. J Nutr. 2004;134:776–784. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.4.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler LM, Duguay Y, Millikan RC, Sinha R, Gagne JF, Sandler RS, Guillemette C. Joint effects between UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A7 genotype and dietary carcinogen exposure on risk of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1626–1632. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramesh A, Morrow JD. From coal stacks to colon cancer-are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons the culprits? Polycyclic Aromat Compds. 2008;28:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lijinsky W. The formation and occurrence of polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons associated with food. Mutat Res. 1991;259:252–261. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(91)90121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramesh A, Archibong AE, Hood DB, Guo Z, Loganathan BG. Global Environmental distribution and human health effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In: Loganathan BG, Lam PKS, editors. Global contamination trends of persistent organic chemicals. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Florida: 2011. pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachse C, Smith G, Wilke MJV, Barrett JH, Waxman R, Sullivan F, Forman D, Bishop DT, Wolf CR the colorectal cancer study group. A pharmacogenetic study to investigate the role of dietary carcinogens in the etiology of colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1839–1849. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler JP, Post GB, Lioy PJ, et al. Assessment of carcinogenic risk from personal exposure to benzo(a)pyrene in the total human environmental exposure study (THEES) J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 1993;43:970–977. doi: 10.1080/1073161x.1993.10467179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lioy PL, Waldman JM, Greenberg A. The total Human Environmental Exposure Study (THEES) to benzo(a)pyrene: comparison of the inhalation and food pathways. Arch Environ Hlth. 1988;43:304–312. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1988.10545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beckman Sundh O, Thuvander A, Andersson C. Preview of PAHs in food: potential health effects and contents in food. Swedish National Food Administration; Uppsala, Sweden: 1998. Report 8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips DH. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the diet. Mutat Res. 1999;443:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramesh A, Archibong AE, Huderson AC, Diggs DL, Myers JN, Hood DB, Rekhadevi PV, Niaz MS. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In: Gupta RC, editor. Veterinary Toxicology. 2nd. London, UK: Academic Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yakibu HY, Martins MS, Takahashi MY. Levels of benzo(a)-pyrene and other polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in liquid smoke flavour and some smoked foods. Food Addit Contam. 1993;10:399–405. doi: 10.1080/02652039309374163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knize MG, Salmon CP, Pais P, et al. Food heating and the formation of heterocyclic aromatic amine and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mutagens/carcinogens. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;459:179–193. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4853-9_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vainiotalo S, Matveinen K. Cooking fumes as a hygienic problem in the food and catering industries. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1993;54:376–382. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez C, Lopez de Carain A, Bello J. Modulation of mutagenic activity in meat samples after deep-frying in vegetable oils. Mutagenesis. 2002;17:63–66. doi: 10.1093/mutage/17.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tateno T, Nagumo Y, Suenaga S. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons produced from grilled vegetables. J Food Hyg Soc Jpn. 1990;31:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramesh A, Walker SA, Hood DB, et al. Bioavailability and risk assessment of orally ingested polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Int J Toxicol. 2004;23:301–333. doi: 10.1080/10915810490517063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamangar F, Strickland PT, Pourshams A, Malekzadeh R, Boffetta P, Roth MJ, Abnet CC, Saadatian-Elahi M, Rakhshani N, Brennan P, Etemadi A, Dawsey SM. High exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons may contribute to high risk of esophageal cancer in northeastern Iran. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:425–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Gijssel HE, Schild LJ, Watt DL, Roth MJ, Wang GQ, Dawsey SM, Albert PS, Qiao YL, Taylor PR, Dong ZW, Poirier MC. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts determined by semiquantitative immunohistochemistry in human esophageal biopsies taken in 1985. Mutat Res. 2004;547:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth MJ, Wei WQ, Baer J, Abnet CC, Wang GQ, Sternberg LR, Warner AC, Johnson LL, Lu N, Giffen CA, Dawsey SM, Qiao YL, Cherry J. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor expression is associated with a family history of upper gastrointestinal tract cancer in a high-risk population exposed to aromatic hydrocarbons. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2391–2396. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth MJ, Strickland KL, Wang GQ, Rothman N, Greenberg A, Dawsey SM. High levels of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons present within food from Linxian, China may contribute to that region's high incidence of oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:757–758. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cross AJ, Freedman ND, Ren J, Ward MH, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Sinha R, Abnet CC. Meat consumption and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer in a large prospective study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;106:432–442. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinha R, Kulldorff M, Gunter MJ, Strickland P, Rothman N. Dietary benzo(a)pyrene intake and risk of colorectal adenoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005a;14:2030–2034. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinha R, Peters U, Cross AJ, Kulldorff M, Weissfeld JL, Pinsky PF, Rothman N, Hayes RB. Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Project Team. Meat, meat cooking methods and preservation and risk for colorectal adenoma. Cancer Res. 2005b;65:8034–8041. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinha R, Cross A, Curtin J, Zimmerman T, McNutt S, Risch A, Holden J. Development of a food frequency questionnaire module and databases for compounds in cooked and processed meats. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005c;49:648–655. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunter MJ, Probst-Hensch NM, Cortessis VK, Kulldorff M, Haile RW, Sinha R. Meat intake, cooking-related mutagens and risk of colorectal adenoma in a sigmoidoscopy-based case-control study. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:637–642. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabatabaei SM, Heyworth JS, Knuiman MW, Fritschi L. Dietary Benzo[a]pyrene Intake from Meat and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:3182–3184. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Cancer Institute (NCI) Computerized Heterocyclic Amines Resource for Research in Epidemiology of Diseases (CHARRED) updated database-2007. [Accessed 18th November 2010];2010 Available from: http://charred.cancer.gov/

- 36.Cross AJ, Ferrucci LM, Risch A, Graubard BI, Ward MH, Park Y, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Sinha R. A large prospective study of meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: an investigation of potential mechanisms underlying this association. Cancer Res. 2010;15:2406–2414. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrucci LM, Sinha R, Graubard BI, Mayne ST, Ma X, Schatzkin A, Schoenfeld PS, Cash BD, Flood A, Cross AJ. Dietary meat intake in relation to colorectal adenoma in asymptomatic women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1231–1240. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin A, Shrubsole MJ, Ness RM, Wu H, Sinha R, Smalley WE, Shyr Y, Zheng W. Meat and meat-mutagen intake, doneness preference and the risk of colorectal polyps: the Tennessee Colorectal Polyp Study. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:136–142. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burnett-Hartman AN, Newcomb PA, Mandelson MT, Adams SV, Wernli KJ, Shadman M, Wurscher MA, Makar KW. Colorectal polyp type and the association with charred meat consumption, smoking, and microsomal epoxide hydrolase polymorphisms. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:583–592. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.553021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips DH. DNA adducts as markers of exposure and risk. Mutat Res. 2005;577:284–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rundle A. Carcinogen-DNA adducts as a biomarker for cancer risk. Mutat Res. 2006;600:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothman N, Poirier MC, Haas RA, Correa-Villasenor A, Ford P, Hansen JA, O'Toole T, Strickland PT. Association of PAH-DNA adducts in peripheral white blood cells with dietary exposure to polyaromatic hydrocarbons. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;99:265–267. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9399265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Maanen JM, Moonen EJ, Maas LM, Kleinjans JC, van Schooten FJ. Formation of aromatic DNA adducts in white blood cells in relation to urinary excretion of 1-hydroxypyrene during consumption of grilled meat. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:2263–2268. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.10.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Saleh I, Arif J, El-Doush I, Al-Sanea N, Jabbar AA, Billedo G, Shinwari N, Mashhour A, Mohamed G. Carcinogen DNA adducts and the risk of colon cancer: case-control study. Biomarkers. 2008;13:201–216. doi: 10.1080/13547500701775449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcea G, Sharma RA, Dennison A, Steward WP, Gescher A, Berry DP. Molecular biomarkers of colorectal carcinogenesis and their role in surveillance and early intervention. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1041–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guengerich FP. Forging the links between metabolism and carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2001;488:195–209. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(01)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang WF, Strobel HW. Effects of cyclophosphamide and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on cell growth and mixed function oxidase activity in a human colon cell line. Cancer Res. 1982;42:3676–3681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White TB, Hammond DK, Vasquez H, Strobel HW. Expression of two cytochroimes P450 involved in carcinogen activation in a human colon cell line. Mol Cell Biochem. 1991;102:61–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00232158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lampen A, Bader A, Bestmann T, Winklers M, Witte L, Borlak JT. Catalytic activities, protein-and mRNA-expression of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes in intestinal cell lines. Xenobiotica. 1998;28:429–441. doi: 10.1080/004982598239362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iwanari M, Nakajima M, Kizu R, Hayakawa K, Yokoi T. Induction of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1 mRNAs by nitropolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in various human tissue-derived cells: chemical-cytochrome P450 isoform-, and cell-specific differences. Arch Toxicol. 2002;76:287–298. doi: 10.1007/s00204-002-0340-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim JH, Yamaguchi K, Lee SH, Tithof PK, Sayler GS, Yoon JH, Baek SJ. Evaluation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the activation of early growth response-1 and peroxisome proliferatior activated receptors. Toxicol Sci. 2005;85:585–593. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herbst U, Fuchs JI, Teubner W, Steinberg P. Malignant transformation of human colon epithelial cells by benzo(c)phenanthrene dihydrodiol epoxides as well as 2-hydroxyamnio-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo (4,5,-b)pyridine. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;212:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Waard WJ, Aarts JMMJG, Peijnenburg AACM, Baykus H, Talsma E, Punt A, de KoK TMCM, van Schooten FJ, Hoogenboom LAP. Gene expression profiling in Caco-2 human colon cells exposed to TCDD, benzo(a)pyrene, and natural Ah receptor agonists from cruciferous vegetables and citrus fruits. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008;22:396–410. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bothe H, Gotz C, Stobbe-Maicherski N, Fritsche E, Abel J, Haarmann-Stemmann T. Luteolin enhances the bioavailibilty of benzo(a)pyrene in human colon carcinoma cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;498:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Autrup H, Grafstrom RC, Brugh M, Lechner JF, Haugen A, Tramp BF, Harris CC. Comparison of benzo(a)pyrene metabolism in bronchus, esophagus, colon and derodeneum from the same individual. Cancer Res. 1982;42:934–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen GM, Grafstrom RC, Gibby EM, Smith L, Autrup H, Harris CC. Metabolism of benzo(a)pyrene and 1-naphthol in cultured human tumorous and non-tumorous colon. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1312–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tatemichi M, Nomura S, Ogura T, Sone H, Nagata H, Esumi H. Mutagenic activation of environmental carcinogens by microsomes of astric mucosa with intestinal metaplasia. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3893–3898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Penning TM. Dihydrodiol dehydrogenase and its role in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism. Chem-Biol Interact. 1993;89:1–34. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(93)03203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological profile for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service; Atlanta, GA: 1995. p. 271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luch A. The carcinogenic effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. London: Imperial College Press Eds; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shimada T. Xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes involved in activation and detoxification of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2006;21:257–276. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.21.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimada T, Guengerich FP. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 1A1-, 1A2-, and 1B1-mediated activation of procarcinogens to genotoxic metabolites by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:288–294. doi: 10.1021/tx050291v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.WHO. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 92. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. Some non-heterocyclic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and some related exposures. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hankinson O. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;35:307–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rowlands J, Gustaffson J. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated signal transduction. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1997;27:109–134. doi: 10.3109/10408449709021615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramesh A, Inyang F, Hood DB, Knuckles ME. Aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase activity in F344 rats subchronically exposed to benzo[a]pyrene and fluoranthene through diet. J Biochem Molecular Toxicology. 2000;14:155–161. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0461(2000)14:3<155::aid-jbt5>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nebert DW, Dalton TP, Okey AB, Gonzalez FJ. Role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated induction of the CYP1 enzymes in environmental toxicity and cancer. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23847–23850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shimada T, Inoue K, Suzuki Y, Kawai T, Azuma E, Nakajima T, Shindo M, Kurose K, Sugie A, Yamagishi Y, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Hashimoto M. Arylhydrocarbon receptor-dependent induction of liver and lung cytochromes P450 1A1, 1A2, and 1B1 by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polychlorinated biphenyls in genetically engineered C57BL/6J mice. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1199–207. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.7.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guengerich FP, Shimada T. Oxidation of toxic and carcinogenic chemicals by human cytochrome P-450 enzymes. Chem Res Toxicol. 1991;8:391–407. doi: 10.1021/tx00022a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moorthy B. Persistent expression of 3-methylcholanthrene-inducible cytochromes P4501A in rat hepatic and extrahepatic tissues. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:313–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu J, Ramesh A, Nayyar T, Hood DB. Assessment of metabolites and AhR and CYP1A1 mRNA expression subsequent to prenatal exposure to inhaled benzo(a)pyrene. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2003;21:333–346. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(03)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shou M, Wells RL, Elkind MM. Enhanced cytochrome P450 (Cyp1b1) expression, aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase activity, cytotoxicity, and transformation of C3H10T1/2 cells by dimethylbenz(a)anthracene in conditioned medium. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4052–4056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bauer E, Guo Z, Ueng YF, Bell LC, Zeldin D, Guengerich FP. Oxidation of benzo(a)pyrene by recombinant human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:136–142. doi: 10.1021/tx00043a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shen Z, Wells RL, Elkind MM. Enhanced cytochrome P450 (cyp1b1) expression, aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase activity, cytotoxicity, and transformation of C3H10T1/2 cells by dimethylbenz(a)anthracene in conditioned medium. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4052–4056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Savas U, Bhattacharyya KK, Christou M, Alexander DL, Jefcoate CR. Mouse cytochrome P450EF, representative of a new 1B subfamily of cytochrome P450s. Cloning, sequence determination, and tissue expression. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14905–14911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhattacharyya KK, Brake PB, Eltom SE, Otto SA, Jefcoate CR. Identification of a rat adrenal cytochrome P450 active in polycyclic hydrocarbon metabolism in rat CYP1B1. Demonstration of a unique tissue specific pattern of hormonal and aryl hydrocarbon receptor-linked regulation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11595–11602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moorthy B. The atherogen 3-methylcholanthrene induces multiple DNA adducts in mouse aortic smooth muscle cells: role of cytochrome P4501B1. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Galvan N, Teske DE, Zhou G, Moorthy B, MacWilliams PS, Czuprynski CJ, Jefcoate CR. Induction of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 in liver and lung by benao(a)pyrene and 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene do not affect distribution of polycyclic hydrocarbons to target tissue: role of AhR and CYP1B1 in bone marrow cytotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;202:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eltom SE, Schwark WS. CYP 1A1 and CYP 1B1, two hydrocarbon inducible cytochromes P450, are constitutively expressed in neonate and adult goat liver, lung and kidney. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;85:65–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1999.tb00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sutter TR, Tang YM, Hayes CL, Wo YY, Jabs EW, Li X, Yin H, Cody CW, Greenlee WF. Complete CDNA sequence of a human dioxin-inducible mRNA identifies a new gene subfamily of cytochrome P450 that maps to chromosome2. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13092–13099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Larsen MC, Angus WG, Brake PB, Eltom SE, Sukow KA, Jefcoate CR. Characterization of CYP1B1 and CYP1A1 expression in human mammary epithelial cells: Role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2366–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shimada T, Gillam EM, Oda Y, Tsumura F, Sutter TR, Guengerich FP, Inoue K. Metabolism of benzo[a]pyrene to trans-7,8-dihydroxy-7, 8-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene by recombinant human cytochrome P450 1B1 and purified liver epoxide hydrolase. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:623–629. doi: 10.1021/tx990028s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Benford DJ, Bridges JW. Carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in food. In: Gibson GC, Walker R, editors. Food Toxicology-Real or Imaginary Problems? London: Taylor and Francis; 1985. pp. 152–166. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stavric B, Klassen R. Dietary effects on the uptake of benzo(a)pyrene. Food Chem Toxicol. 1994;32:727–734. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(09)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ding X, Kaminsky LS. Human extrahepatic cytochrome P450: function in xenobiotic metabolism and tissue-selective chemical toxicity in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:149–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kargman SL, O'Neil GP, Vickers PJ, Evans JF, Mancini JA, Jothy S. Expression of prostaglandin G/H synthase-1 and -2 protein in human colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2556–2559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kelley DJ, Mestre JR, Subbaramaiah K, Sacks PG, Schantz SP, Tanabe T, Inoue H, Ramonetti JT, Dannenberg AJ. Benzo(a)pyrene up-regulates cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in oral epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:795–799. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wiese FW, Thompson PA, Kadlubar FF. Carcinogenic substrate specificity of human COX-1 and COX-2. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:5–10. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lampen A, Ebert B, Stumkat L, Jacob J, Seidel A. Induction of gene expression of xenobiotic metabolism enzymes and ABC-transport proteins by PAH and a reconstituted PAH mixture in human Caco-2 cells. Biochemica et Biophysica Acta. 2004;1681:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Darwish W, Ikenaka Y, Eldaly E, ishizuka M. Mutagenic activation and detoxification of benzo[a]pyrene invitro by hepatic cytochrome P4501A1 and phase II enzymes in three meat producing animals. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:2526–2531. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sattar A, Hewer A, Phillips DH, Campbell FC. Metabolic proficiency and benzo(a)pyrene DNA adduct formation in ApcMin mouse adenomas and uninvolved mucosa. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1097–1101. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.6.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Foussat J, Costet P, Galtier P, Pineau T, Lesca P. The 4S benzo(a)pyrene-binding protein is not a transcriptional activator of Cyp1A1 gene in Ah receptor-deficient (AHR -/-) transgenic mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;349:349–355. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shimizu Y, Nakatsuru Y, Ichinose M, takahashi Y, Kume H, Mimura J, Fuju-Kuriyama Y, Ishikawa T. Benzo[a]pyrene carcinogenicity is lost in mice lacking the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:779–782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Harrigan JA, McGarrigle BP, Sutter TR, Olson JR. Tissue specific induction of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1 and 1B1 in rat liver and lung following in vitro (tissue slice) and in vivo exposure to benzo(a)pyrene. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20:426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Uno S, Dalton TP, Derkenne S, Curran CP, Miller ML, Shertzer HG, Nebert DW. Oral exposure to benzo[a]pyrene in the mouse: detoxication by inducible cytochrome P450 is more important than metabolic activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1225–1237. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Uno S, Dalton TP, Dragin N, Curran CP, Derkenne S, Miller ML, Shertzer HG, Gonzalez FJ, Nebert DW. Oral benzo[a]pyrene in Cyp1 knowckout mouse lines: CYP1A1 important in detoxication, CYP1B1 metabolism required for immune damage independent of total-body burden and clearance rate. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1103–1114. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shi Z, Dragin N, Galvez-Peralta M, Jorge-Nebert LF, Miller ML, Wang B, Nebert DW. Organ-specific roles of CYP1A1 during detoxication of dietary benzo[a]pyrene. Mol Pharmacol. 2010a;78:46–57. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.063438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shi Z, Dragin N, Miller ML, Stringer KF, Johansson E, Chen J, Uno S, Gonzalez FJ, Rubio C, Nebert DW. Oral benzo[a]pyrene-induced cancer: two distinct types in different target organs dependent on the mouse Cyp1 genotype. Int J Cancer. 2010b;10:2334–2350. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Uno S, Dragin N, Miller ML, Dalton TP, Gonzalez FJ, Nebert DW. Basal and inducible Cyp1 mRNA quantitation and protein localization throughout the mouse gastrointestinal tract. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Romero DL, Mounho BJ, Lauer FT, Born JL, Burchiel SW. Depletion of glutathione by benzo(a)pyrene metabolites, ionomycin, thapsigargin, and phorbol myristate in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;144:62–69. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Delescluse C, Lemaire G, de Sousa G, Rahmani R. Is CYP1A1 induction always related to AHR signaling pathway? Toxicology. 2000;153:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ou X, Weber TJ, Chapkin RS, Ramos KS. Interference with protein kinase C-related signal transduction in vascular smooth muscle cells by benzo[a]pyrene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;318:122–30. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Laupeze B, Amiot L, Sparfel L, Ferrec EL, Fauchet R, Fardel O. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons affect functional differentiation and maturation of human-monocyte derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:2652–2658. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Archuleta MM, Schieven GL, Ledbetter JA, Deanin GG, Burchiel SW. 7,12-Dimethylbenz(a)an-thracene (DMBA) activates protein tyrosine kinases Fyn and Lck in the HPB-ALL human T cell line and increases tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCg1, IP3 formation, and mobilization of intracellular calcium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6105–6109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Krieger JA, Davila DR, Lytton JL, Born JL, Burchiel SW. Inhibition of sarcoplasmic/-endoplasmic reticulum calciumATPases (SERCA) by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in HPB-ALL human T cells and other tissues. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;133:102–108. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Page TJ, O'Brien S, Jefcoate CR, Czuprynski CJ. 7,12-Dimethylbenz[a]anthracene induces apoptosis in murine pre-B cells through a caspase-8-dependent pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:313–319. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Page TJ, MacWilliams PS, Suresh M, Jefcoate CR, Czuprynski CJ. 7-12 Dimethylbenz[a]an-thracene-induced bone marrow hypocellularity is dependent on signaling through both the TNFR and PKR. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;198:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Riddihough G, Pennisi E. The evolution of epigenetics. Science. 2001;293:1063. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5532.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Weidman JR, Dolinoy DC, Murphy SK, Jirtle RL. Cancer susceptibility: epigenetic manifestation of environmental exposures. Cancer J. 2007;13:9–16. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31803c71f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Laird PW. Cancer epigenetics. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14 Spec No 1:R65–76. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Herceg Z. Epigenetics and cancer: towards an evaluation of the impact of environmental and dietary factors. Mutagenesis. 2007;22:91–103. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gel068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Upham BL, Weis LM, Trosko JE. Modulated gap junctional intercellular communication as a biomarker of PAH epigenetic toxicity: Structure-function relationship. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:975–981. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106s4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rummel AM, Trosko JE, Wilson MR, Upham BL. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with bay-like regions inhibited gap junctional intercellular communication and stimulated MAPK activity. Toxicol Sci. 1999;49:232–240. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/49.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bláha L, Kapplová P, Vondrácˇek J, Upham B, Machala M. Inhibition of gap-junctional intercellular communication by environmentally occurring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Toxicol Sci. 2002;65:43–51. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rogers AE, Nauss KM. Rodent models for carcinoma of the colon. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30:87S–102S. doi: 10.1007/BF01296986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Heyer J, Yang K, Lipkin M, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R. Mouse models for colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:5325–5333. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Culp SJ, Warbritton AR, Smith BA, Li EE, Beland FA. DNA adduct measurements, cell proliferation and tumor mutation induction in relation to tumor formation in B6C3F1 mice fed coal tar or benzo[a]pyrene. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1433–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shane BS, de Boer J, Watson DE, Haseman JK, Glickman BW, Tindall KR. LacI mutation spectra following benzo(a)pyrene treatment of Big Blue mice. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:715–725. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sattar A, Hewer A, Phillips DH, Campbell FC. Metabolic proficiency and benzo(a)pyrene DNA adduct formation in ApcMin mouse adenomas and uninvolved mucosa. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1097–1101. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.6.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Paulsen JE, Namrok E, Steffensen IL, Eide TJ, Alexander J. Identification and quantification of aberrant crypt foci in the colon of Min mice-a murine model of familial adenomatous polyposis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:534–539. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sale S, Tunstall RG, Ruparelia KC, Potter GA, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Comparison of the effects of the chemopreventive agent resveratrol and its synthetic analog trans 3,4,5,4′-tetramethoxystilbene (DMU-212) on adenoma development in the ApcMin+ mouse and cyclooxygenase-2 in human derived colon cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:194–201. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]