Abstract

Ribosomal DNA sequence data abounds from numerous studies on the dinoflagellate endosymbionts of corals, and yet the multi-copy nature and intragenomic variability of rRNA genes and spacers confound interpretations of symbiont diversity and ecology. Making consistent sense of extensive sequence variation in a meaningful ecological and evolutionary context would benefit from the application of additional genetic markers. Sequences of the non-coding region of the plastid psbA minicircle (psbAncr) were used to independently examine symbiont genotypic and species diversity found within and between colonies of Hawaiian reef corals in the genus Montipora. A single psbAncr haplotype was recovered in most samples through direct sequencing (∼80–90%) and members of the same internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2) type were phylogenetically differentiated from other ITS2 types by substantial psbAncr sequence divergence. The repeated sequencing of bacterially-cloned fragments of psbAncr from samples and clonal cultures often recovered a single numerically common haplotype accompanied by rare, highly-similar, sequence variants. When sequence artifacts of cloning and intragenomic variation are factored out, these data indicate that most colonies harbored one dominant Symbiodinium genotype. The cloning and sequencing of ITS2 DNA amplified from these same samples recovered numerically abundant variants (that are diagnostic of distinct Symbiodinium lineages), but also generated a large amount of sequences comprising PCR/cloning artifacts combined with ancestral and/or rare variants that, if incorporated into phylogenetic reconstructions, confound how small sequence differences are interpreted. Finally, psbAncr sequence data from a broad sampling of Symbiodinium diversity obtained from various corals throughout the Indo-Pacific were concordant with ITS lineage membership (defined by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis screening), yet exhibited substantially greater sequence divergence and revealed strong phylogeographic structure corresponding to major biogeographic provinces. The detailed genetic resolution provided by psbAncr data brings further clarity to the ecology, evolution, and systematics of symbiotic dinoflagellates.

Introduction

The acquisition of genetic evidence continues to further our understanding of the ecology and evolution of dinoflagellates in symbioses with reef-building corals and many other invertebrates [1]–[4]. Sequences of ribosomal and single-copy nuclear, chloroplast, and mitochondrial DNA indicate that the ancient symbiont genus Symbiodinium comprises highly divergent groups (i.e., Clades) each containing a diversity of genetically distinct lineages (reviewed in [4]). The habitat and biogeographic distributions of particular host-symbiont combinations allude to underlying ecological and evolutionary processes shaping the fidelity and flexibility of these associations [5], [6]. However, many Symbiodinium that exhibit ecological differences in host specificity are closely related and differentiated by only small, albeit fixed, numbers of nucleotide changes in conventional nuclear and plastid DNA sequences.

Despite the availability of informative genetic markers, there is presently little consensus on how to classify Symbiodinium species diversity without relying on traditional morphological traits (cf. [7]). While internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2) data are commonly used to define the diversity of these symbionts [6]–[12], the finding of extensive intra-specific sequence variation among ITS regions reported in free-living dinoflagellates [13] challenges assertions that even a fixed single-base substitution or insertion-deletion (indel) is sufficient to characterize a species of Symbiodinium [7]–[9], [11], [12]. Despite this, it was recently demonstrated that a lineage-based approach [14], [15] combining sequences of mitochondrial (Cyt b), chloroplast (cp23S) and ribosomal genes (LSU) and spacer regions (ITS) could identify and classify Symbiodinium into fundamental biological units (i.e., species) [7]. Whereas the sequence analysis of a single gene barely resolves distinct lineages, additional sequence information improves phylogenetic resolution by increasing branch length separation and branch support among actual species lineages. Alternatively, sequences from microsatellite flanker regions and the non-coding regions of the dinoflagellate plastid minicircles, may have greater resolving power that unambiguously delimit closely-related taxa without relying on the assembly of numerous independent sequences.

The chloroplast genes of peridinin-containing dinoflagellates occur on separate plasmid-like minicircles of 2–5 kbp. Each contains a non-coding region that may function in gene replication and transcription [16]–[19]. Preliminary analysis of psbA minicircles among Symbiodinium observed extensive variation in the non-coding regions (psbAncr) among isolates of Clade C [20] and were non-alignable with sequences from other Clades (e.g., A and B). Moreover isolates with similar or identical large sub-unit (LSU) rDNA sequences also shared similar psbAncr sequences suggesting a concordance with nuclear gene evolution [20]. Indeed, this plastid maker shows great promise for investigations of Symbiodinium ecology, evolution, and systematics. In a recent application, psbAncr sequence phylogenies unequivocally resolved three host-specific Clade C Symbiodinium lineages corresponding to each of three Pocillopora spp. in the eastern tropical Pacific [21]. These lineages were identified as closely-related, yet separate, ITS2 types using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) [8]. Therefore, the psbAncr may definitively resolve independently evolving Symbiodinium spp. that are initially diagnosed, but are not well resolved, by ITS genotyping.

In order to more thoroughly assess the utility of the psbAncr, we examined this marker in the context of Symbiodinium diversity among common Hawaiian reef corals in the genus Montipora. Symbiont diversity in M. capitata from the island of O'ahu was examined in two previous studies with conflicting results. Based on PCR-DGGE analysis of the ITS2 region, LaJeunesse et al. [22] reported symbioses between Hawaiian M. capitata and two Symbiodinium ITS2 lineages: type D1a (in orange colony morphs at depths of 1–2 m; now more precisely referred to as D1-4-6; sensu [12]) and type C31 (involving various colony morphologies distributed across a depth range of 1–5 m). In contrast, a recent study employing bacterial cloning of the Symbiodinium ITS2 in M. capitata from shallow (1–2 m) habitats in O'ahu reported 17 different ITS2 variants, including sequences representing D1/D1a, C31, C21, C3, C17 and 11 additional, closely-related sequences at lower frequency [23]. There are thus two competing hypotheses for symbiotic associations in M. capitata based on the application of two different methodologies (i.e., PCR-DGGE vs. PCR and bacterial cloning) analyzing ITS2. The first paradigm indicates that coral colonies are often dominated by a single symbiont ITS2 type with symbiont species diversity partitioned primarily among different host species, habitats, and/or depths [22]. The alternative paradigm suggests that communities comprising many different symbiont ITS2 types occur within each colony with overall endosymbiont diversity greater within than between host individuals [23].

Resolution of these alternate possibilities is paramount to understanding the ecology and evolution of coral-algal symbioses. The opposing interpretations of Symbiodinium diversity between LaJeunesse et al. [22] and Stat et al. [23] may result from the multi-copy and heterogeneous nature of eukaryotic ribosomal genes and spacer regions and the different methodologies used to analyze this maker for ecological studies [7], [24]. When applied to a multi-copy gene array, the more-conservative approach of PCR-DGGE screening targets the dominant copies of the ribosomal array [24], [25], whereas cloning generates large amounts of sequence data that include mixtures of both dominant and rare, functional and non-functional, intra-genomic and inter-genomic sequence variants combined with PCR and cloning artifacts [7], [24]. By comparison, plastid DNA markers, such as the psbAncr, are more akin to single-copy loci in that they exhibit relatively low intragenomic variation and their use may reduce uncertainty when evaluating genetic diversity. We therefore used the psbAncr to test the competing hypotheses of LaJeunesse et al. [22] and Stat et al. [23]. The psbAncr and ITS2 were PCR-amplified, bacterially cloned, and sequenced in a subset of samples. Cloned ITS2 sequences were compared with results from parallel analyses using DGGE screening and direct sequencing of numerically abundant ITS2 variants observed as bright bands in the gel profiles (i.e., fingerprints) of symbionts associated with three Montipora spp. from Hawaii. Furthermore, the psbAncr was cloned and sequenced from several isoclonal cultures of Clade C to assess intragenomic variation. Single copies of cloned psbAncr were then re-amplified, re-cloned, and sequenced to determine the relative contribution of mutation artifacts generated by the PCR and cloning process. Finally psbAncr sequences from the Symbiodinium in Montipora and other common reef coral genera at selected locations throughout the Indo-Pacific were evaluated phylogenetically for concordance with DGGE-ITS2 genotyping.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection, processing and preservation

Coral tissue samples used in this investigation were collected using scuba equipment from deep and shallow reef habitats from O'ahu, Hawaii [24], the Great Barrier Reef, Australia [26], [27], Zamami Island, Japan [27], Zanzibar, Tanzania [12], and the Andaman Sea, Thailand [12]. Montipora spp. samples examined in detail from O'ahu, Hawaii were collected in July of 2002 from the shallow lagoon (1–5 m) and deep fore-reef environments (20 m) of Kanehoe Bay, and from intermediate depths from a site on the north shore of O'ahu. DNA samples used in this study were from previously published archived samples. Hawaiian samples were acquired under collecting permits issued from the State of Hawaii to the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology during the Edwin W. Pauley summer course “Molecular Biology of Corals” in 2002. The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority provided permits to collect under the auspices of the Australian Institute of Marine Science and University of Queensland. Collections from the Andaman Sea were permitted by the National Research Council of Thailand (no. 0002.3/5154).

Samples were processed by stripping animal tissue from their skeletons using high-pressure bursts of air and then separating the dense symbiont cells using centrifugation [see 26 for details]. The resulting pellet was preserved in a sodium salt-DMSO buffer [28]. Alternatively, whole skeletal fragments with live tissue were preserved. A supplementary table is provided that details the coral species sampled, collection dates, locations, specific sites surveyed at each location, colony depth, the host genus and species, as well as GenBank accession numbers for each psbAncr haplotype sequence (Table S1).

Three iso-clonal Symbiodinium cultures, rt113, rt152, and rt203 (“rt” is used here to indicate original cultures from the Robert K. Trench collection, [2]), were chosen to assess the degree of intragenomic varation for psbAncr. All are representatives of Clade C; culture rt113 is the holotype of Symbiodinium goreaui (Trench and Blank 1987) isolated from the corallimorpharian Rhodactis lucida in the Caribbean; culture rt152 shares the same ITS2 type (C1) with S. goreaui and was isolated from the corallimorph Discosoma sanctithomae; whereas culture rt203 was isolated from the giant clam Hippopus hippopus from Palau and represents a different ITS2 lineages (type C2 sensu [2]). Symbiodinium cells from each of these cultures were concentrated by centrifugation and preserved in sodium salt-DMSO buffer [28].

Molecular-genetic analysis

Preserved Symbiodinium pellets or skeletal fragments comprising approximately 5–10 mm2 of preserved tissue were mechanically disrupted using a Biospec Beadbeater (Bartlesville, OK, USA) for 1 min at maximum speed. Nucleic acids were then extracted using a modified Wizard DNA extraction protocol developed by Promega (Madison, WI, USA; see LaJeunesse et al. [12], [26] for protocol modifications). All samples were initially analyzed using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis fingerprinting (i.e., genotyping) and sequencing of the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) as described by LaJeunesse [8]. This technique is employed to target the numerically dominant sequence variant(s) in a sample [24]. The host mitochondrial control region was amplified and directly sequenced for two suspect samples using the ms_FP2 and MON_RP2 primers and PCR conditions described by van Oppen et al. [29]

Samples were further analyzed by amplifying and directly sequencing the non-coding region of the plastid psbA minicircle using the primers (7.4-Forw, 5′ - GCA TGA AAG AAA TGC ACA CAA CTT CCC - 3′, and 7.8-Rev, 5′ - GGT TCT CTT ATT CCA TCA ATA TCT ACT G - 3′ [17]). These primers preferentially amplify Clade C psbA ncr haplotypes over those from Clade D. As an alternative, the universal primers psbAFor_1 (5′- GCA GCT CAT GGT TAT TTT GGT AGA C - 3′) and psbARev_1 (5′- AAT TCC CAT TCT CTA CCC ATC C - 3′) were used to amplify psbA ncr haplotypes of clade D. The PCR conditions for all amplifications were: 94°C for 2 min; then 40 cycles of 94°C 10 s, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 2 min; followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Samples appearing homogenous for D1-4-6 based on ITS2-DGGE profiles from M. capitata and M. patula were used [22]. Finally, amplifications of ITS2 and psbAncr sequences from genomic extracts of five Montipora capitata samples collected in Hawaii were cloned using a pGEM-T cloning kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. For each genetic marker 9–15 clones were sequenced.

PCR products were usually sequenced in one direction using Big Dye 3.1 reagents (Applied Biosystems, USA) at the DNA Core Facility (Penn State University) using the reverse primer from the ITS2 (ITSrev) and forward primer for the psbA (7.4-Forw). Chromatograms were visually inspected for accuracy in base calling (Sequence Navigator) and the edited sequences aligned initially using the online application of ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) and additional adjustments to the alignment made during visual inspection of the output file using MacClade version 4.06 (Sinauer & Associates).

To examine the amount of psbAncr variation within a Symbiodinium genome (i.e., intragenomic variation), the psbAncr was amplified from isoclonal cultures rt113, rt152, and rt203 using the 7.4-Forw and 7.8-Rev primers, the product cloned, and then bi-directionally sequenced (see above). A total of 16 clones were originally sequenced from each culture. Based on these data a second round of cloning was conducted where one representative clone from each culture was selected, re-cloned, and then sequenced repeatedly (n = 16) to determine what proportion of sequence variation can be attributed to artifacts generated by PCR and/or the process of cloning.

Data analyses

Phylogenetic reconstructions based on ITS2 and partial sequences of the psbA were conducted using Maximum parsimony (MP) and Distance under the default settings in PAUP* 4.0b10 [30]. For calculating phylogenies based on MP, insertions and deletions (indels) were analyzed as a 5th character state. In analysis of Distance the SYM+I+G model for molecular evolution, a symmetrical nucleotide substitution model incorporating a gamma distribution of rate variation and a proportion of invariant sites was chosen based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) in MrModelTest version 2 [31]. To assess statistical significance of internal branching, 1,000 Bootstrap replicates were performed as well as Bayesian posterior probabilities calculated using MrBayes version 3.12 [32]. Two million generations were analyzed under the SYM+I+G model of sequence evolution, beginning with an unspecified tree topology and no defined prior probabilities. Two sets of four chains (three hot, one cold) were run for 2×107 generations and sampled every 100 generations. In all cases, the chains converged within 2.5×106 generations. Therefore, the first 2,500 trees (2.5×106 generations) were discarded as burn-in and a 50% majority-rule consensus tree was calculated from the remaining 17,500 trees. Nodal support was reported as posterior probabilities.

Results and Discussion

ITS sequence variation in recognizing Symbiodinium diversity

Ribosomal spacer regions are frequently targeted in molecular systematics to delimit species of animals, plants, fungi, macro-algae, and eukaryotic microbes [33], [34]. The current understanding of Symbiodinium species diversity, ecology, and evolution is based primarily on analysis of ITS2 and to some extent ITS1 sequence data acquired from a broad range of host species from tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world (e.g. [6], [10], [35]–[37]). As with almost all eukaryotes, the multi-copy ribosomal arrays of Symbiodinium genomes evolve in concert and are usually dominated by one or two numerically common and very similar sequence variants [24], [38], [39]. For this reason, denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of the ITS2 is often used to isolate and identify (1) the dominant intragenomic ITS2 sequence(s) diagnostic of a particular symbiont lineage (e.g. [7], [8], [24]) and (2) to detect the presence of two or more symbionts co-occurring within a sample (e.g., [8], [40], [41]).

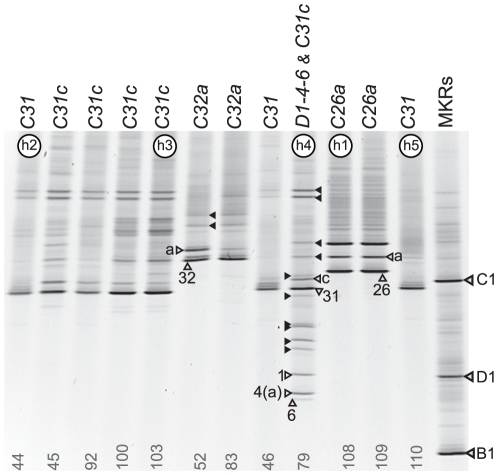

Montipora spp. samples from O'ahu, Hawaii were screened using ITS2-DGGE to examine the genetic diversity of Symbiodinium (Fig. 1). Four distinctive symbiont types were identified, including C32a from a shallow (4 m) and deep (10 m) colony of M. flabellata, C26a from deep (>20 m) encrusting colonies of M. incrassata (which were originally misidentified as M. capitata in LaJeunesse et al. [22], but were re-identified by mitochondrial control region sequences [29]; JQ043552), and C31 and D1-4-6 (originally D1a and later changed to D1a-f by Smith et al. [42]) from shallow (1–4 m) colonies of M. capitata. Many of the C31 profiles contained a second band designated as “c” (Fig. 1) and may represent a co-dominant intragenomic ITS2 variant (see [24]), or possibly the presence of a second close-related symbiont. A mixed symbiont population comprising C31c and D1-4-6 was detected in only one sample (sample 79, lane 9 of Fig. 1).

Figure 1. ITS2-DGGE fingerprints of Symbiodinium from Montipora spp. sampled in Oahu, Hawaii.

Each diagnostic fingerprint comprises high-melting-lower-migrating homoduplexes (open arrowheads) and low-melting-higher-migrating heteroduplexes (solid arrowheads). Homoduplexes apparently correspond to the numerically dominant sequence variant in the ribosomal array of each ITS type [i.e.], [ 7,24]. Sample 79 contains two symbiont profiles, C31 and D1-4-6. Samples used in bacterial cloning/sequencing of the ITS2 and psbA ncr are labeled on the gel by their psbAncr haplotypes (h1, h2, h3 etc…; see Figs. 2a and 3).

The approach of using DGGE to screen the ITS2 sequence variation assumes that (1) most samples contain a single dominant symbiont genotype and (2) that the resulting DGGE fingerprint, sometimes comprising multiple bright bands in a profile, generates a visualization of the evolutionary state (i.e., the degree of homogenization through concerted evolution) of the resident symbiont's ribosomal array. If these underlying assumptions were generally wrong, interpretations of DGGE profiles would under assess the diversity of Symbiodinium in hospite. Indeed, DGGE screening does not detect background symbiont populations comprising less than 10–15% of the total population [40], [43], [44], including populations that are of potential ecological importance [45]. Extensive ITS sequence diversity was reported for Symbiodinium in a recent analysis of M. capitata colonies from Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii, using bacterial cloning and sequencing [23]. Stat et al. acknowledged that the significance of this sequence diversity was open to several interpretations; however, the authors favored the idea that it represented a combination of several coexisting symbiont lineages within a colony and intragenomic variation from those various symbiont types [23]. To further explore this possibility, we reexamined five of the Montipora spp. samples analyzed by DGGE (above) via cloning and extensive sequencing of ITS2 amplicons. The selected samples included M. captiata colonies identified with C31 (n = 2), C31c (n = 1), a mixed community of C31c/D1-4-6 (n = 1), and one M. incrassata colony identified with C26a (selected samples are designated as h1–h5 in Fig. 1).

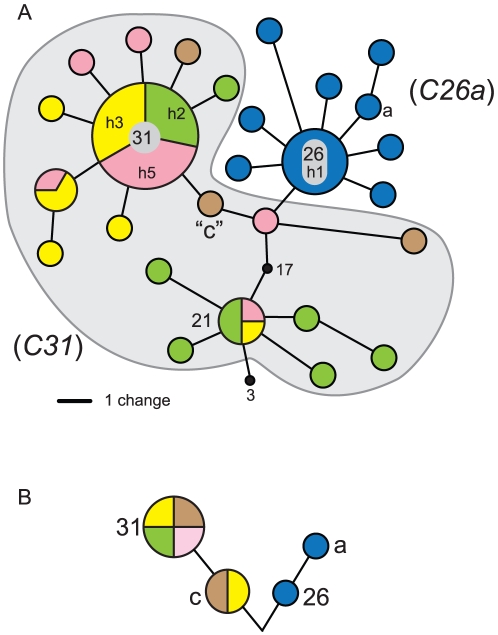

Of the 70 cloned ITS2 fragments sequenced from 5 coral colonies, a total of 33 distinct variants were identified (Figs. 2, 3; GenBank accession numbers JQ003824-JQ003850). This included 27 sequence variants from Clade C and 6 sequence variants from Clade D. Maximum Parsimony analyses showed that within each Montipora sample, genetically distinct sequences (color coordinated to identify the sample of origin in Figs. 2, 3) differed by 1–8 base substitutions. All cloned sequences of C26a from M. incrassata (blue sequences, Fig. 2) clustered together with no phylogenetic overlap with sequences derived from the M. capitata C31/C31c samples (yellow, green, pink, and brown sequences, Fig. 2). The most commonly recovered sequence from each sample usually occupied a central “ancestral” position from which mostly rare singletons radiated. Furthermore, the most commonly cloned sequences typically corresponded with sequences of the bands from the diagnostic DGGE profiles of each sample (Fig. 1). One exception was the finding of the sequence diagnostic of Symbiodinium type C21 in three of the four samples (n = 4 out of 55 clones), whereas previously only clade C types, C31 or C31c, were detected by DGGE analysis (Fig. 1). Most (12 of 15; 80%) of the cloned sequences recovered from sample 79 were from Clade D and analysis of them is discussed below.

Figure 2. Sequence variation recovered by cloning vs. DGGE screening.

(a) Unrooted maximum parsimony of sequence variants recovered from the process of bacterial cloning/sequencing of ITS2 rDNA from four samples of C31/C31c (h2–h5) and one sample of type C26a (h1) from a subset of samples presented in Figure 1 (b) A corresponding and highly simplified phylogeny based on screening the numerically dominant sequence variants using DGGE fingerprinting. Clones from each sample were color coordinated for comparison and apply to other figures throughout the text.

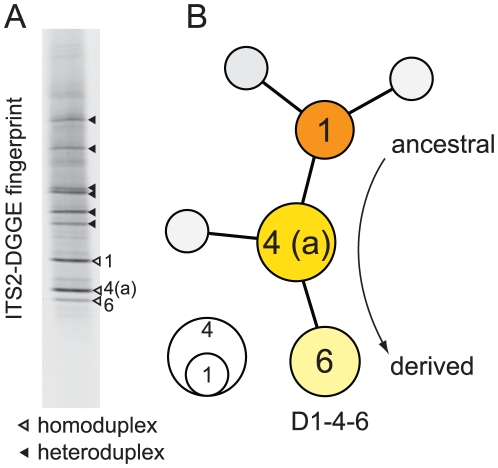

Figure 3. The clade D Symbiodinium sp. harbored by Hawaiian Montipora (a) ITS2-DGGE fingerprinting produced three diagnostic homoduplex bands from each sample containing this Symbiodinium.

Designated D1-4-6, band “1” is ancestral while bands “4” and “6” represent derived sequence variants abundant in the genome. (b) All three dominant sequences were recovered multiple times from the bacterial cloning/sequencing from the sample 79, Figure 1. A profile matching Symbiodinium D1-4-6 was found in a few Pocillopora from the Andaman Sea, northeastern Indian Ocean and was also recovered from Pocillopora colonies in the aquarium trade.

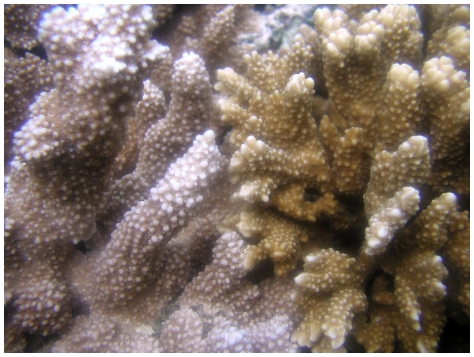

Montipora capitata in Hawaii occasionally harbor Clade D Symbiodinium [5], [22]. Preliminarily designated D1a by LaJeunesse et al. [22], further examination of the DGGE profile identified a third co-dominant sequence as diagnostic of this Symbiodinium type from other members of Clade D (Fig. 3a; designated D1a-f by Smith et al. [42]; and renamed D1-4-6 by LaJeunesse et al. [12]. Colonies of M. capitata dominated by D1-4-6 have an orange hue while those associated primarily with C31 or C31c are red-brownish in coloration (Fig. 4). Sample 79 harbored a mixture of both symbionts (Fig. 1) and when the ITS2 amplification from this sample was cloned, the majority of sequences were representative of D1-4-6 (Fig. 3b; JQ003816-JQ003823). Specifically, the three most commonly cloned sequences corresponded to the three bands diagnostic of this symbiont's DGGE profile (i.e., D- “1”, “4” and “6”), with three additional sequences detected as singletons. Stat et al. [23] also detected the same three diagnostic sequences of D1-4-6, but interpreted these sequences as potentially representative of three distinct symbionts.

Figure 4. Color morphs of Montipora capitata are dominated by different species of Symbiodinium.

The reddish brown colony on the left harbors the Montipora-specific symbiont C31/C31c, while the orangish-brown colony on the right harbors the Clade D symbiont, D1-4-6.

The ITS2 sequence diversity derived from bacterial cloning (n = 33) was considerably greater than results from DGGE fingerprinting/screening (n = 7, representing only 4 entities; see also [24]). This incongruence between methods mirrors the findings of Stat et al. [23] compared to LaJeunesse et al. [22]. Furthermore, this discrepancy raises fundamental questions about the biology of coral-algal symbioses and the accuracy of the existing genetic taxonomy of Symbiodinium (sensu [8]). Are the additional sequences recovered by bacterial cloning important to understanding the ecology of these symbioses? Or, do they mostly comprise intra-genomic variants as well as PCR and cloning artifacts, as indicated by Thornhill et al. [24] and Sampayo et al. [7]? Alternatively, is the cloned sequence diversity indicative of diverse Symbiodinium species populations found within individual coral colonies (sensu [46])? Resolving these questions is critical for the proper interpretation of endosymbiont sequence diversity and for understanding the basic biological processes underpinning the ecology and evolution of coral-algal symbioses. The rapidly evolving non-coding region of the plastid psbA minicircle (psbAncr) is a candidate marker with low intragenomic variation that may provide independent data to examine symbiont diversity and assess the degree to which colonies host multiple genotypes.

Resolving Symbiodinium diversity with a chloroplast minicircle non-coding region

The plastid genomes of dinoflagellates are highly unusual in that individual genes typically occur independently on small (2–5 kb) plasmid-like minicircles [19]. The total number of genes retained in the chloroplast is small and includes those encoding proteins important in the reaction center of photosystem II, photosystem I, the b6f complex, ATP synthase, as well as rRNA genes [47], [48]. Each minicircle contains a non-coding region of differing length and nucleotide composition that is speculated to function in gene duplication and/or transcription [49]. Recently, sequence comparison of psbA minicircle non-coding region (psbA ncr) observed substantial divergence among samples of Clade C Symbiodinium originating from different hosts [17], [20], [21]. Sequences of the non-coding region are not comparable between members of different Clades and therefore, the use of this genetic marker must be restricted to intra-cladal comparisons [20].

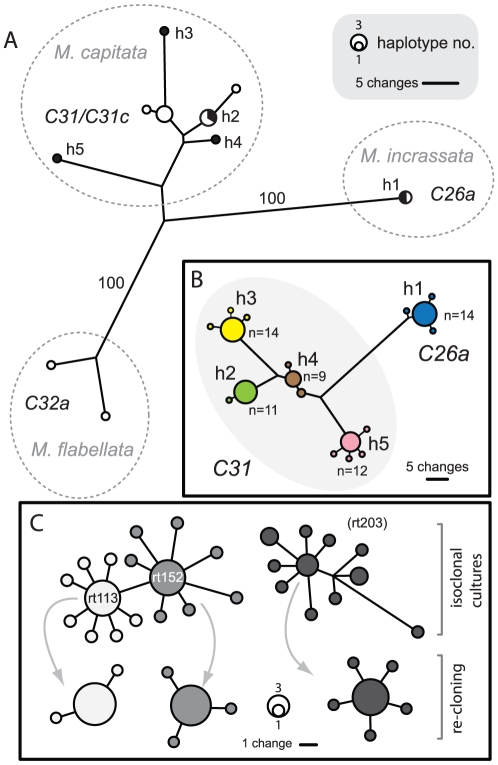

Direct sequencing of psbA ncr from 16 samples of Hawaiian Montipora spp. produced a single unambiguous sequence per sample. No secondary peaks were detected in the chromatograms, suggesting that (1) the psbA ncr exhibits low intragenomic variability (i.e., equivalent to a single-copy marker) in these Symbiodinium and (2) each sample contained a single Symbiodinium haplotype. The phylogenetic analysis of partial psbA ncr sequences (ranging between 536 and 601 bp in length) produced three divergent groupings. Haplotypes from each phylogenetic grouping shared the same ITS-DGGE fingerprint (i.e., ITS2 type C31/C31c, C26a, or C32a) indicating a correspondence between nuclear and plastid makers (Fig. 5a). Finally, each symbiont lineage associated with a particular species of Montipora indicating marked differences in their host specificity and ecological distribution (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5. The analysis of Symbiodinium psbAncr acquired from field samples and isoclonal cultures.

(a) Unrooted phylogenetic analysis of partial (∼500 bases) psbA ncr sequences recovered from direct sequencing of Symbiodinium from Hawaiian Montipora. The symbiont's ITS2 designation and host species identity are labeled and correspond with phylogenetic groupings based on psbAncr sequences. Samples subjected to bacterial cloning and intensive sequencing are shaded in black. Bootstrap values based on 1000 replicates are labeled for branches separating each lineage group. (b) The phylogenetic analysis of bacterially cloned psbAncr shows minimal sequence variation within a particular sample, but considerable variation between samples. The number of clones sequenced is indicated for each sample analyzed. (c) The extent of intragenomic variation was examined by the cloning and sequencing of psbA ncr amplicons from the isoclonal clade C cultures, rt113, rt152, and rt203 (n = 16 sequences per culture). Sequence divergence among variants was small among strains of Symbiodinium goreaui (type C1; rt113 and rt152), however these were nonalignable with sequence variants recovered from rt203. The re-cloning and sequencing (n = 16) of a single cloned amplicon from each cultured isolate (grey arrows) assessed the frequency of artifacts created by the PCR/cloning process.

Because direct sequencing may not detect the presence of background co-occurring psbAncr haplotypes, amplifications were cloned and sequenced from the same five samples whose ITS2 diversity was analyzed using this same approach (see above). Totals of 9 to 14 clones were sequenced from each sample and of these, two to five distinct sequences were recovered. The combined analyses of all these data produced five distinct, non-overlapping sequence clusters (Fig. 5b; JQ043553- JQ043585). The numerically dominant psbA ncr sequence detected in each sample was identical to the sequence obtained by direct sequencing. The remaining cloned sequence variants were singletons that differed from the dominant haplotype by 1 or 2 nucleotide substitutions. In comparison to the cloning of ITS2 rDNA, the psbAncr exhibits less within-sample heterogeneity (i.e., 2–5 sequences were detected per sample for the psbA ncr vs. 6–9 sequences detected per sample for the ITS2), while providing unambiguous phylogenetic resolution. The minimal sequence divergence of rare psbA ncr variants suggests that some were created by mutations introduced through polymerase error during PCR or the cloning process (i.e., methodological artifact/error [24]), but alternatively, they could represent low levels of intragenomic variation and/or the existence of closely-related background haplotypes.

The copy number of each minicircle gene is unknown and may vary depending on the growth phase of a dinoflagellate cell [50]. As a result, intragenomic psbAncr variation may exist and confound interpretations about diversity (sensu [24]). To address this possibility, we PCR amplified, cloned, and sequenced the psbAncr from three iso-clonal cultures of Clade C Symbiodinium including the holotype of S. goureai (rt113 designated ITS2 type C1) and type C2 (sensu [2]), an unnamed species. Results from these analyses show that, when PCR and cloning artifacts are factored out (see below), intragenomic variation does exist in the psbAncr and that the extent of this variation may differ between clonal lineages and species of Symbiodinium (Fig. 5c; JQ043677- JQ043719). The dominant psbAncr sequence of culture rt152 (ITS2 type C1) differed from culture rt113 (ITS2 type C1) by one base substitution and four insertion-deletions over the entire non-coding region (922 aligned bases). Culture rt152 therefore represents a distinct haplotype variant of S. goreaui. The psbAncr sequences obtained for rt203 (ITS2 type C2) were not alignable with the haplotypes of S. goreaui indicating that this marker has limited phylogenetic utility when comparing Symbiodinium spp. whose ITS-5.8S regions differ by approximately 2% or more (Fig. S1). Although variation was minimal in the genomes of each S. goreaui haplotype, the culture of type C2 (rt203) contained numerous variants with large indels (Fig. 5c). The high internal variability in rt203 explains why attempts to directly sequence the psbAncr from this isolate ultimately failed. The presence of intragenomic variation may explain why the psbAncr amplifies and/or sequences poorly for certain ITS2 lineages (unpubl. data). While the psbAncr of many Symbiodinium spp. exhibits relatively minor intragenomic variability and allows for unambiguous direct sequencing (see below), further investigations are needed to evaluate the range of genome contained variation across all the taxonomic ranks of this dinoflagellate group [20].

Some of the psbAncr sequence variants recovered by cloning resulted from errors introduced during the PCR and cloning process (i.e., Taq polymerase error and/or mutations during cloning). The re-amplification, re-cloning, and sequencing of single amplicons produced variants that differed by a single base change (out of approx. 500 bp) from the original cloned sequence (Fig. 5c; JQ043720- JQ043745). Based on these examples, approximately 10 to 30% of cloned variants from original samples are probably artifacts of the method used to obtain these data (Fig. 5b), a finding which cautions against the over interpretation of small sequence differences present in data generated by bacterial cloning.

Intragenomic variation and methodological artifacts recovered by the PCR amplification and cloning of the psbAncr appear minor when compared to the sequence divergence observed among haplotypes from different Symbiodinium ITS2 lineages (Fig. 5a), and thus minimally interfere with phylogenetic signal provided by this marker. For both psbAncr and ITS2, PCR/cloning retrieves rare intragenomic variants and generates sequence artifacts. However, psbAncr exhibits much higher intergenomic variation between Symbiodinium types and species than does ITS2, and as a result, the confounding effects of intragenomic variation and methodological error are substantially reduced when analyzing psbAncr data (see below).

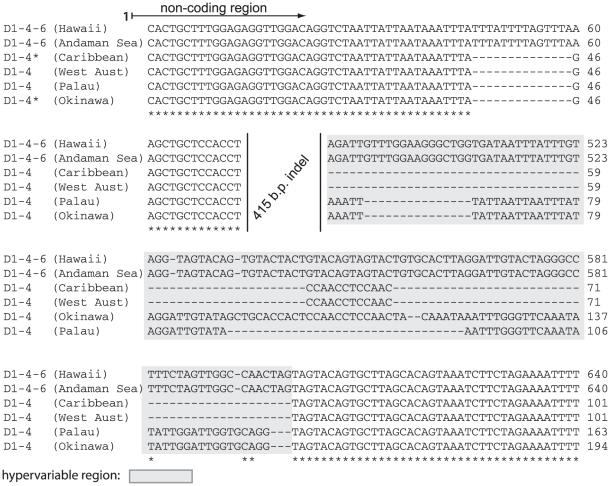

Analysis of the psbA ncr was also applied to resolve contradictory interpretations pertaining to the identity of the Clade D Symbiodinium found in some colonies of Montipora spp. from Hawaii (see earlier discussion [22], [23]; Fig. 3). The chromatograms of psbA ncr directly sequenced from several samples were unambiguous (e.g., JQ043586), indicating that the ITS2 variation observed in Figure 3 was representative of one entity (sensu [24]) and not a mixed community of Clade D symbionts as proposed by Stat et al. [23]. (A single Clade D multi-locus genotype was also detected in each sample based on the analysis of microsatellite markers [51], [52] [data not shown].) These sequences were nearly identical to the psbA ncr from samples of Pocillopora sp. collected in the Andaman Sea with the same D1-4-6 ITS2-DGGE profile (Fig. 6). These aligned poorly to partial psbA ncr sequences of S. trenchi (a.k.a. D1a or D1-4) found in samples collected from the western Pacific (Lobophyllia hemprichii from Palau) and eastern Indian Ocean (Pocillopora damicornis from Dampier, Western Australia; JQ043747), and cultured isolates from Okinawa, Japan and the Florida Keys, USA (A001, JQ003851, and 10.8b JQ043746, respectively) and therefore suggests that divergence time is much longer between these lineages than is indicated by the similarity in genomic composition of their dominant ITS2 sequences.

Figure 6. Alignment of partial psbA ncr sequences comparing D1-4-6 with that of Symbiodinium trenchi (synonymous with D1a or D1-4) obtained from different hosts in geographically separate regions.

Sequences marked by the asterisk are from isolates in culture.

Phylogenetic utility of psbAncr

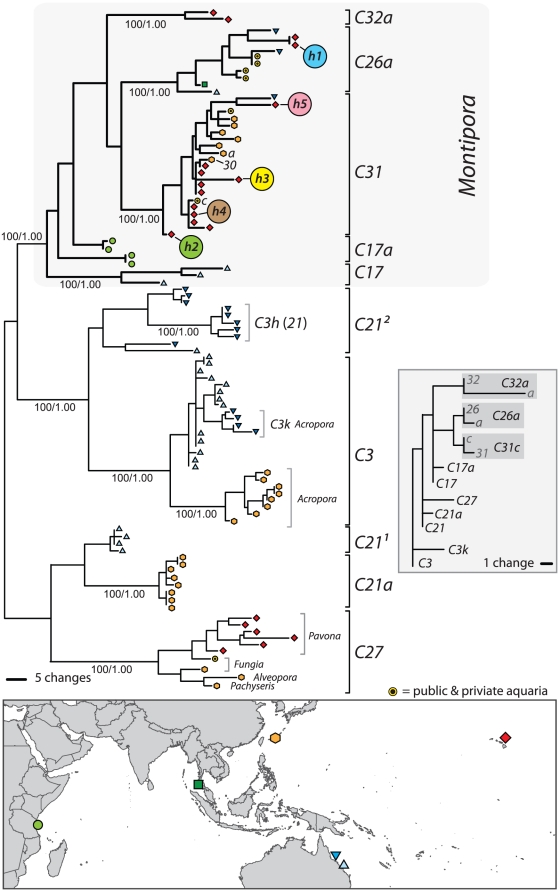

The phylogeny of psbA ncr haplotypes in Figure 2a resolved three divergent lineages that corresponded with their respective ITS2 membership. To assess whether the psbA ncr and ITS2 (based on DGGE screening) data remain congruent over large geographic distances samples obtained from multiple regions throughout the Indo-Pacific were re-analyzed using both markers. These samples included representatives of types C31 and C26a as well as C3, C17, and C21, lineages that allegedly exist within M. capitata from Hawaii [23]. Overall, the psbA ncr phylogeny was concordant with that of the ITS2 phylogeny (Fig. 7 inset) with individual samples exhibiting reciprocal monophyly for each marker (JQ043587- JQ043676). PsbAncr haplotypes of a particular ITS2 type clustered together irrespective of geographic and host origin. For example, Symbiodinium designated as C26a from Montipora in the Indian Ocean, the Pacific Ocean, and the aquarium trade [42] formed a well-defined monophyletic cluster separated by large breaks in sequence similarity from other ITS2 lineages. The one notable exception was that psbA ncr haplotypes designated “C21” formed two independent and divergent lineages not resolved by ITS2 sequences. However these lineages are differentiated by ITS1 sequences (data not shown) indicating that, with additional rDNA data, there is near complete correspondence between nuclear and plastid genomes [7], [53]. This concordance indicates sexual recombination in many cases appears limited to membership within an ITS2 lineage and is grounds for defining biological species [54].

Figure 7. Phylogenetic reconstruction based on partial psbA ncr of common Symbiodinium ITS types characterized from locations throughout the Indo-Pacific (see map).

Despite originating from geographically remote locations, psbA ncr haplotypes of particular ITS types group to form clades separated by considerable sequence divergence from other ITS types. A diverse monophyletic lineage consisting of different ITS2 types associates exclusively with coral species in the genus Montipora. These are divergent from ‘ancestral’ host-generalist lineages C3, C21, and C27. The inset (shaded grey) is a corresponding ITS2 phylogeny showing how, despite minimal sequence divergence, its topology reflects that of the psbA ncr tree.

In comparison to the psbA ncr, the ITS2 is highly conserved and unchanging over broad geographic distances. ITS2 lineages separated by small sequence differences are well differentiated by the numerous base substitutions and insertion-deletions in the psbA ncr. These high amounts of sequence divergence revealed geographic partitioning not resolved by ITS2 data. For example, the haplotypes of several ITS2 lineages, including “C3” and “C27,” were sub-divided phylogenetically into populations originating from different biogeographic regions (Fig. 7). These data also indicate that small differences between ITS lineages mask extensive periods of elapsed time since their original divergence (millions of years in some cases [6]). PsbAncr sequences from various ITS lineages comprising the “C3 radiation” align poorly with sequences from lineages of the “C1 radiation” (sensu [6], Fig. S1]) and suggests that a calibrated evolutionary clock for the rate of change in this plastid DNA would improve estimates of divergence times among the numerous “closely-related” lineages comprising Symbiodinium Clade C [6]. Although the psbAncr is too divergent in certain cases (e.g., C1 vs. C2), when used in conjunction with more conserved DNA regions, the added genetic resolution offered by this marker will be extremely helpful in future investigations that require precise knowledge of Symbiodinium identity [17], [20].

Symbiont homogeneity vs. heterogeneity in coral colonies

The proportion of colonies in a population found to harbor multiple Symbiodinium spp. is dependent on the species of host, reef habitat, and recent stress history [8], [40], [45], [55]–[58]. However, data from the psbA ncr appears consistent with observations that many coral colonies typically harbor a single dominant Symbiodinium genotype [8], [40], [51], [58]–[61]. While other species of symbiont are sometimes detectable at very low population densities, their ecological significance and temporal stability requires further evaluation [8], [43]. The argument that sequence variation in cloned rDNA is indicative of true biological diversity does not address the reality that extensive intragenomic variation and methodological artifacts account for most, if not all, sequence diversity in a sample [24]. If most colonies harbor highly-diverse Symbiodinium assemblages, then why did the cloning process employed here (Fig. 3), or by Stat et al. [23], fail to recover any of the ITS2 and psbA ncr sequences that correspond to the many other Symbiodinium spp. (∼18) harbored by other cnidarians that co-occur with Montipora capitata in habitats around Kaneohe Bay [22]? Instead, Stat et al. [23] recovered most frequently the ITS2 sequences diagnostic for C31 and D1-4-6, and to a lesser extent sequences diagnostic of Symbiodinium C21. In addition, sequences for C3 and C17, as well as 11 closely related novel variants, also were identified, that, with C31 and C21, comprise a monophyletic lineage separate from all other Clade C Symbiodinium common among other corals in Hawaii [22]. If these sequences represent many different symbiont lineages, cloning and sequencing of the psbA ncr from M. capitata presumably would have detected multiple psbA ncr lineages corresponding to each of these different Symbiodinium spp. (e.g. C21) Because no such variation was detected here, the most parsimonious conclusion is that Montipora spp. coral colonies typically harbor one dominant genotype of one symbiont species (see discussion below). Future studies should use the psbA ncr to examine Symbiodinium diversity among the colonies of many species and from different regions to determine the generality of these findings. In this regard, rapidly evolving genetic markers with limited intragenomic variation, such as the psbA ncr and microsatellites, provide a third tier of differentiation (beyond Clades and ITS types) that resolve individual genotypes (or haplotypes) of Symbiodinium and can thus supply independent data on the relative homogeneity of a resident symbiont population.

The ribosomal array abounds with rare variants that are derived from the current numerically dominant copy, and yet may also contain once dominant ancestral sequences reduced in frequency by concerted evolution (Fig. 2a; [24]). The psbAncr and ITS2 phylogenies in Figure 7 offer a likely explanation for why ITS2 sequences matching C3, C17, and C21 (and minor variants of these) were obtained from cloning (Fig. 2a [23]). These three sequences are ancestral to the derived sequence “31” in the adaptive radiation of Symbiodinium Clade C associated with Montipora [6]. An ITS sequence is considered diagnostic of a particular Symbiodinium only if it is numerically dominant in the genome [7], [8], [24]. A rational explanation for the recovery of sequences that designate C3, C21, and C17 during cloning is that these ancestral sequences persist in the genomes of C31 individuals at low abundance and have not undergone complete replacement (i.e., lineage sorting) via concerted evolution (for example, see Fig. 6; [39]).

The sensitivity of bacterial cloning confounds analysis of rDNA because, aside from the sequence artifacts it introduces, low-copy variants are indiscriminately cloned and sequenced. That Stat et al. [23] reported significant sequence variation/variability at the colony level is not surprising and rather expected in the context of cloning's ability to recover rare variants. In theory, individuals in a species population should have essentially the same dominant ITS sequence (Fig. 7; [38]), but are likely to have considerable inter-individual variation involving low-abundance variants found throughout the ribosomal array of an individual's genome (a clonal lineage in the case of Symbiodinium). The findings of Stat et al. are more consistent with the reality that cloning rDNA and spacers mostly characterizes the variability of low-copy variants found among individual genotypes of Symbiodinium C31 and D1-4-6.

Conclusions and future considerations

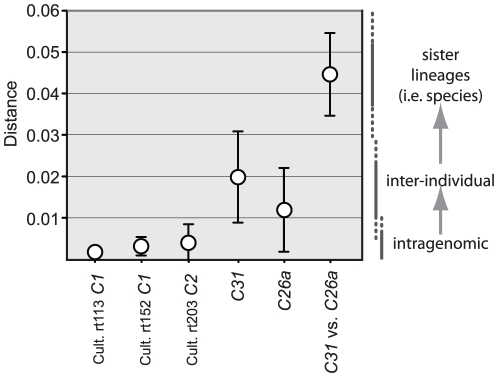

The psbAncr is currently the fastest evolving genetic maker known for Symbiodinium, and provides independent evidence for assessing species diversity and ecology. The application of the psbAncr in future investigations should significantly reduce uncertainty when interpreting the source of sequence variation. Unlike ITS rDNA, there appears to be considerably less overlap between intragenomic, inter-individual and inter-species variation (Fig. 8). Because of its fast evolutionary pace, the phylogenetic utility of the psbAncr is limited to analyzing the relationships of only the most close-related species. Therefore, future studies should incorporate a hierarchical genetic approach to precisely examine the genetic diversity of Symbiodinium within and between colonies and across reef coral assemblages.

Figure 8. Average pairwise genetic distances compared among intragenomic, inter-individual, and inter-species sequence variation of the psbA ncr (error bars represent ± SD).

Note the minimal overlap of nucleotide differences (Distance) between intragenomic (variation within a culture) and inter-individual variation (variation within an ITS2 lineage). This region is sometimes non-alignable among species lineages within a Symbiodinium Clade.

Conventional species descriptions for protists are presently impractical for the majority of Symbiodinium. This study demonstrates the efficacy of combining data from a multi-copy nuclear rDNA spacer and a rapidly evolving plastid marker to accurately discriminate species-level diversity in Symbiodinium. Indeed, the concordant patterns revealed by ITS2 and psbAncr (Fig. 7) show no recombination among sympatric lineages that, together with, well-supported monophyletic groupings with distinct ecological niches satisfy criteria according to the biological, phylogenetic, and ecological species concepts [14], [15]. We recommend that a combination of genetic and ecological data should supersede the conventional use of morphological features for describing species of Symbiodinium. The psbAncr adds to a growing number of genetic tools that when used in combination provides the resolution necessary to thoroughly explore the global diversity, connectivity, and ecology of coral-Symbiodinium associations.

Supporting Information

Alignment of the complete psbAncr sequence from the cultures rt113 ( Symbiodinium goreaui ), rt152 ( Symbiodinium goreaui ), and rt203 ( Symbiodinium sp., type C2 sensu LaJeunesse 2001) aligned using the online application of ClustalW2 ( http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/ ). The cloned sequences chosen represent the numerically dominant sequence variant identified for each cultured strain.

(DOCX)

Symbiodinium samples, their ITS2 designations along with host species, depth of collection, and geographic origin. GenBank accession numbers for psbAncr sequences are provides and were used to reconstruct the phylogeny in Figure 7. Shallow, intermediate and deep refers to collection depths ranging from 1–5, 6–10, and >10 meters, respectively.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank our many collaborators, past and present, who helped with fieldwork and the acquisition and transfer of samples. We also thank Dr. Mary Alice Coffroth for providing cultures of S. trenchi.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by the Edwin W. Pauley foundation, the Pennsylvania State University, and National Science Foundation grants (IOB 544854 and OCE-09287664). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Rowan R. Diversity and ecology of zooxanthellae on coral reefs. J Phycol. 1998;344:7–1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaJeunesse TC. Investigating the biodiversity, ecology, and phylogeny of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates in the genus Symbiodinium using the ITS region: in search of a ‘species’ level marker. J Phycol. 2001;37:866–880. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker AC. Flexibility and specificity in coral-algal symbiosis: diversity, ecology, and biogeography of Symbiodinium. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S. 2003;34:661–689. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffroth MA, Santos SR. Genetic diversity of symbiotic dinoflagellates in the genus Symbiodinium. Protist. 2005;156:19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowan R, Powers DA. A molecular genetic classification of zooxanthellae and the evolution of animal-algal symbiosis. Science. 1991;251:1348–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.251.4999.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaJeunesse TC. Species radiations of symbiotic dinoflagellates in the Atlantic and Indo-Pacific since the Miocene-Pliocene transition. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:570–581. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampayo E, Dove S, LaJeunesse TC. Cohesive molecular genetic data delineate species diversity in the dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:500–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaJeunesse TC. Diversity and community structure of symbiotic dinoflagellates from Caribbean coral reefs. Mar Biol. 2002;141:387–400. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sampayo EM, Franceschinis L, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Dove S. Niche partitioning of symbiotic dinoflagellates. Mol Ecol. 2007;16:3721–3733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampayo EM, Ridgway T, Bongaerts P, Hoegh-Gulberg O. Bleaching susceptibility and mortality of corals are determined by fine-scale differences in symbiont type. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10444–10449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708049105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finney JC, Pettay T, Oxenford H, LaJeunesse TC. The relative significance of host-habitat, depth, and geography on the ecology, endemism and speciation of coral endosymbionts. Microb Ecol. 2010;60:250–263. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9681-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaJeunesse TC, Pettay DT, Sampayo EM, Phongsuwan N, Brown B, et al. Long-standing environmental conditions, geographic isolation and host–symbiont specificity influence the relative ecological dominance and genetic diversification of coral endosymbionts in the genus Symbiodinium. . J Biogeogr. 2010;37:785–800. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litaker RW, Vandersea MW, Kibler SR, Reece KS, Stokes NA, et al. Recognizing dinoflagellates species using ITS rDNA sequences. J Phycol. 2007;43:344–355. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avise JC, Wollenberg K. Phylogenetics and the origin of species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7748–7755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Queiroz K. Species concepts and species delimitation. Syst Biol. 2007;56:879–886. doi: 10.1080/10635150701701083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z, Cavalier-Smith T, Green BR. Evolution of dinoflagellate unigenic minicircles and the partially concerted divergence of their putative replicon origins. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:489–500. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore RB, Ferguson KM, Loh WKW, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Carter DA. Highly organized structure in the non-coding region of the psbA minicircle from clade C Symbiodinium. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2003;53:1725–1734. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson MJ, Green BR. Double hairpin elements and tandem repeats in the non-coding region of Adenoides eludens chloroplast gene minicircles. Gene. 2005;358:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howe CJ, Nisbet RER, Barbrook AC. The remarkable chloroplast genomes of dinoflagellates. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:1035–1045. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbrook AC, Visram S, Douglas AE, Howe CJ. Molecular diversity of dinoflagellate symbionts of Cnidaria: the psbA minicircle of Symbiodinium. Protist. 2006;157:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinzón JH, LaJeunesse TC. Species delimitation of common reef corals in the genus Pocillopora using nucleotide sequence phylogenies, population genetics and symbiosis ecology. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:311–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaJeunesse TC, Thornhill DJ, Cox E, Stanton F, Fitt WK, et al. High diversity and host specificity observed among symbiotic dinoflagellates in reef coral communities from Hawaii. Coral Reefs. 2004;23:596–603. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stat M, Bird CE, Pochon X, Chasqui L, Chauka LJ, et al. Variation in Symbiodinium ITS2 sequence assemblages among coral colonies. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e15854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thornhill DJ, LaJeunesse TC, Santos SR. Measuring rDNA diversity in eukaryotic microbial systems: how intragenomic variation, pseudogenes, and PCR artifacts confound biodiversity estimates. Mol Ecol. 2007;16:5326–5340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaJeunesse TC, Pinzón JH. Screening intragenomic rDNA for dominant variants can provide a consistant retrieval of evolutionarily persistent ITS (rDNA) sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;45:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaJeunesse TC, Loh WKW, van Woesik R, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Schmidt GW, et al. Low Symbiont diversity in southern Great Barrier Reef corals relative to those of the Caribbean. Limnol Oceanogr. 2003;48:2046–2054. [Google Scholar]

- 27.LaJeunesse TC, Bhagooli R, Hidaka M, deVantier L, Done T, et al. Closely related Symbiodinium spp. differ in relative dominance in coral reef host communities across environmental, latitudinal and biogeographic gradients. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004;284:147–161. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seutin G, White BN, Boag PT. Preservation of avian blood and tissue samples for DNA analysis. Can J Zool. 1991;60:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Oppen MJH, Koolmees EM, Veron JEN. Patterns of evolution in the scleractinian coral genus Montipora (Acroporidae). Mar Biol. 2004;144:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swofford DL. 2000. PAUP*, Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 4.0b10, Sinauer, Sunderland, MA.

- 31.Nylander J. MrModelTest v2. 2002. Program distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

- 32.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman A. Is there a molecular key to the level of “biological species” in eukaryotes? A DNA guide. Mol Phyl Evol. 2009;50:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seifert KA. Progress towards DNA barcoding of fungi. Mol Ecol Res. 2009;9:83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Oppen MJH, Palstra FP, Piquet AMT, Miller DJ. Patterns of coral–dinoflagellate associations in Acropora: significance of local availability and physiology of Symbiodinium strains and host-symbiont selectivity. Proc Roy Soc Lond B. 2001;268:1759–1767. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez-Lanetty M, Krupp DA, Weis VM. Distinct ITS types of Symbiodinium in Clade C correlate with cnidarian/dinoflagellate specificity during onset of symbiosis. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004;275:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silverstein RN, Correa AMS, LaJeunesse TC, Baker AC. Novel algal symbiont (Symbiodinium spp.) diversity in reef corals of Western Australia. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2011;422:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dover GA. Molecular drive: A cohesive mode of species evolution. Nature. 1982;299:111–117. doi: 10.1038/299111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hillis DM, Dixon MT. Ribosomal DNA: Molecular evolution and phylogenetic inference. Q Rev Biol. 1991;66:411–453. doi: 10.1086/417338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thornhill DJ, LaJeunesse TC, Kemp DW, Fitt WK, Schmidt GW. Multi-year, seasonal genotypic surveys of coral-algal symbioses reveal prevalent stability or postbleaching reversion. Mar Biol. 2006;148:711–722. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kemp DW, Fitt WK, Schmidt GW. A microsampling method for genotyping coral symbionts. Coral Reefs. 2008;27:289–293. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith R, Pinzón JH, LaJeunesse TC. Symbiodinium (Dinophyta) diversity and stability in aquarium corals. J Phycol. 2009;45:1030–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2009.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mieog JC, van Oppen MJH, Cantin NE, Stam WT, Olsen JL. Real-time PCR reveals a high incidence of Symbiodinium clade D at low levels in four scleractinian corals across the Great Barrier Reef: implications for symbiont shuffling. Coral Reefs. 2007;26:449–457. [Google Scholar]

- 44.LaJeunesse TC, Reyes-Bonilla H, Warner ME, Wills M, Schmidt GW, et al. Specificity and stability in high latitude eastern Pacific coral-algal symbioses. Limnol Oceanog. 2008;53:719–727. [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaJeunesse TC, Finney JC, Smith RT, Oxenford H. Outbreak and persistence of opportunistic symbiotic dinoflagellates during the 2005 Caribbean mass coral ‘bleaching’ event. Proc Roy Soc Lond B. 2009;276:4139–4148. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Apprill AM, Gates RD. Recognizing diversity in coral symbiotic dinoflagellates communities. Mol Ecol. 2007;16:1127–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bachvaroff TR, Concepcion GT, Rogers CR, Herman EM, Delwiche CF. Dinoflagellate expressed sequence tag data indicate massive transfer of chloroplast genes to the nuclear genome. Protist. 2003;155:65–78. doi: 10.1078/1434461000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hackett JD, Yoon HS, Soares MB, Bonaldo MF, Casavant TL, et al. Migration of the plastid genome to the nucleus in a peridinin dinoflagellate. Curr Biol. 2004;14:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dang Y, Green BR. Long transcripts from dinoflagellate chloroplast minicircles suggest “rolling circle” transcription. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5196–5203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.058545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koumandou VL, Howe CJ. The copy number of chloroplast gene minicircles changes dramatically with growth phase in the dinoflagellate Amphidinium operculatum. Protist. 2007;158:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pettay T, LaJeunesse TC. Microsatellite loci for assessing genetic diversity, dispersal and clonality of coral symbionts in the ‘stress-tolerant’ Symbiodinium clade D. Mol Ecol Resources. 2009;9:1022–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wham DC, Pettay DT, LaJeunesse TC. Microsatellite loci for the host-generalist “zooxanthella” Symbiodinium trenchi and other Clade D Symbiodinium. Conserv Genet Resources. 2011;3:541–544. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pochon X, Montoya-Burgos JI, Stadelmann B, Pawlowski J. Molecular phylogeny, evolutionary rates, and divergence timing of the symbiotic dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;38:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mayr E. Species concepts and definitions. In: Mayr E, editor. The Species Problem. Washington DC: Amer Assoc Advance Sci Publ 50; 1957. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rowan R, Knowlton N. Intraspecific diversity and ecological zonation in coral-algal symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2850–2853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ulstrup KE, van Oppen MJH. Geographic and habitat partitioning of genetically distinct zooxanthellae (Symbiodinium) in Acropora corals on the Great Barrier Reef. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:3477–3484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen CA, Wang J-T, Fang L-S, Yang YW. Fluctuating algal symbiont communities in Acropora palifera (Scleractinia:Acroporidae) from Taiwan. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2005;295:113–121. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thornhill DJ, Xiang Y, Fitt WK, Santos SR. Reef endemism, host specificity and temporal stability in populations of symbiotic dinoflagellates from two ecologically dominant Caribbean corals. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Santos SR, Gutiérrez-Rodríguez C, Lasker HR, Coffroth MA. Symbiodinium sp. associations in the gorgonian Pseudopterogorgia elisabethae in the Bahamas: high levels of genetic variability and population structure in symbiotic dinoflagellates. Mar Biol. 2003;143:111–120. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pettay DT, Wham DC, Pinzón JH, LaJeunesse TC. Genotypic diversity and spatial–temporal distribution of Symbiodinium clones in an abundant reef coral. Mol Ecol (online early) 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pinzón JH, Devlin-Durante MK, Weber XM, Baums IB, LaJeunesse TC. Microsatellite loci for Symbiodinium A3 (S. fitti) a common algal symbiont among Caribbean Acropora (stony corals) and Indo-Pacific giant clams (Tridacna). Conserv Gen Res. 2011;3:45–47. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Alignment of the complete psbAncr sequence from the cultures rt113 ( Symbiodinium goreaui ), rt152 ( Symbiodinium goreaui ), and rt203 ( Symbiodinium sp., type C2 sensu LaJeunesse 2001) aligned using the online application of ClustalW2 ( http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/ ). The cloned sequences chosen represent the numerically dominant sequence variant identified for each cultured strain.

(DOCX)

Symbiodinium samples, their ITS2 designations along with host species, depth of collection, and geographic origin. GenBank accession numbers for psbAncr sequences are provides and were used to reconstruct the phylogeny in Figure 7. Shallow, intermediate and deep refers to collection depths ranging from 1–5, 6–10, and >10 meters, respectively.

(DOC)