Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The aim of this study was to provide evidence that the anterior chamber of the eye serves as a novel clinical islet implantation site.

Methods

In a preclinical model, allogeneic pancreatic islets were transplanted into the anterior chamber of the eye of a baboon model for diabetes, and metabolic and ophthalmological outcomes were assessed.

Results

Islets readily engrafted on the iris and there was a decrease in exogenous insulin requirements due to insulin secretion from the intraocular grafts. No major adverse effects on eye structure and function could be observed during the transplantation period.

Conclusions/interpretation

Our study demonstrates the long-term survival and function of allogeneic islets after transplantation into the anterior chamber of the eye. The safety and simplicity of this procedure provides support for further studies aimed at translating this technology into the clinic.

Keywords: Allogeneic, Anterior chamber of the eye, Baboon, Diabetes, Immune privilege, Islet transplantation, Streptozotocin

Introduction

Significant progress has been made in the field of beta cell replacement therapies by pancreatic islet transplantation in patients with unstable type 1 diabetes [1–3]. The current site for therapeutic islet transplantation is the intrahepatic portal system. However, a disadvantage of this site is the massive loss of islets post-transplantation due to inflammation after blood contact, the activation of the hepatic microenvironment, and poor vascularisation [3, 4]. Additional hurdles are the difficulties in monitoring islet grafts and the relatively high intrahepatic levels of immunosuppressive drugs potentially toxic to islets. The islet transplant community is therefore actively working on the development of alternative implantation sites [5–7].

Using a rodent model, we showed that the anterior chamber of the eye is an optimal islet implantation site allowing pancreatic islets to engraft and function indefinitely and be monitored non-invasively [8, 9]. Advances in ophthalmic microsurgery and the use of intraocular devices and medications to treat ocular diseases have made manipulations of the eye a routine and safe approach in the practice of ophthalmology. Here we have evaluated the anterior chamber of the eye as a safe site for therapeutic implantation of islets in a relevant preclinical animal model.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Miami. As a transplant recipient we used a baboon (The Mannheimer Foundation, Inc., Homestead, FL, USA) that was rendered diabetic with streptozotocin (1,250 mg/m2) [7, 10]. Allogeneic donor baboon islets, recovered and isolated as previously described [10, 11], were transplanted into the anterior chamber of the right eye by cornea and ocular immunology specialists (V. L. Perez and E. Arrieta) under general anaesthesia (isoflurane; 3–4% induction; 1–2% maintenance) within 40 min. The baboon was placed on a restraining board under an operation microscope and the head was held in place with tape facing upwards. A topical anaesthetic (tetracaine 1gtt q5min × 3) and a topical antibiotic (fourth generation cephalosporin, 1gtt q5min × 3) were applied to the eye. To constrict the pupil we applied miotic eye drops (pilocarpine 1% [wt/vol.], 3 days prior to transplantation). The ocular surface was prepared for sterility with iodine. The eye was draped for surgery and a lid speculum was placed to retract the eyelids. We performed a paracentesis/corneal self sealing incision at superior temporal and nasal quadrants alternatively with a 15 superblade. Great care was taken to not damage the iris and to avoid bleeding.

Twenty thousand islet equivalents were aspirated into a blunt, thin walled 25-gauge custom made cannula connected to polyethylene tubing. The islets were aspirated in a minimal volume (200 µl) to facilitate injection into the anterior chamber. We injected 20,000 islet equivalents with the 25-gauge cannula, making sure islets were distributed throughout the iris to allow better engraftment. We left the anaesthetised baboon in the head holder for an additional 30 min. After transplantation, the baboon was treated with topical steroids and topical antibiotics two times a day for 7 days. A second islet transplantation in the same eye was performed on postoperative day (POD) 292. We did not observe any potential complications in the procedure, such as intraocular infection or inflammation, retinal detachment, and/or proliferative vitreo-retinopathy, in the transplanted eye of the baboon. Immunosuppression consisted of monotherapy with anti-CD154 (5C8) at 20 mg/kg i.v. on PODs −1, 0, 3, 10, 18, 28 and every 28 days thereafter. Insulin was administered as needed to maintain fasting blood glucose in the 5–9 mmol/l range and postprandial glucose in the 5–11 mmol/l range. Fasting C-peptide levels were monitored weekly, HbA1c was monitored monthly (DCA 2000+ Analyzer, Bayer, Elkhart, IN, USA) and IVGTTs and glucagon challenges were undertaken to assess graft function [12]. Clinical signs, fluid balance, blood glucose, body weight and nutritional intake were monitored regularly, and weekly blood tests were carried out to monitor overall health.

We performed longitudinal, complete ophthalmologic evaluations of the transplanted eye and compared the pattern to that of the contralateral, untreated eye. The baboon was examined at PODs 3, 7, 24, 44, 78, 236, 306 and 357 under ketamine sedation (20 mg/kg). At each session, we conducted a complete examination of the transplanted and non-transplanted eyes using slit-lamp examination. At selected time points we further conducted anterior segment angiography of islet grafts. Aqueous humour was collected by puncture. We assessed ophthalmic complications of the anterior segment, such as cataract formation, endophthalmitis, increased intraocular pressure, poor visualisation of islets through the cornea, severe inflammation in the operated or sympathetic eye and neovascularisation, using serial slit-lamp biomicrosocopy and intraocular pressure measurements by standard tonometry. We further assessed ophthalmic complications of the posterior segment, such as retinal detachment, neovascularisation and sympathetic ophthalmia, using serial funduscopic examination.

Results

Functional engraftment of islets in the anterior chamber

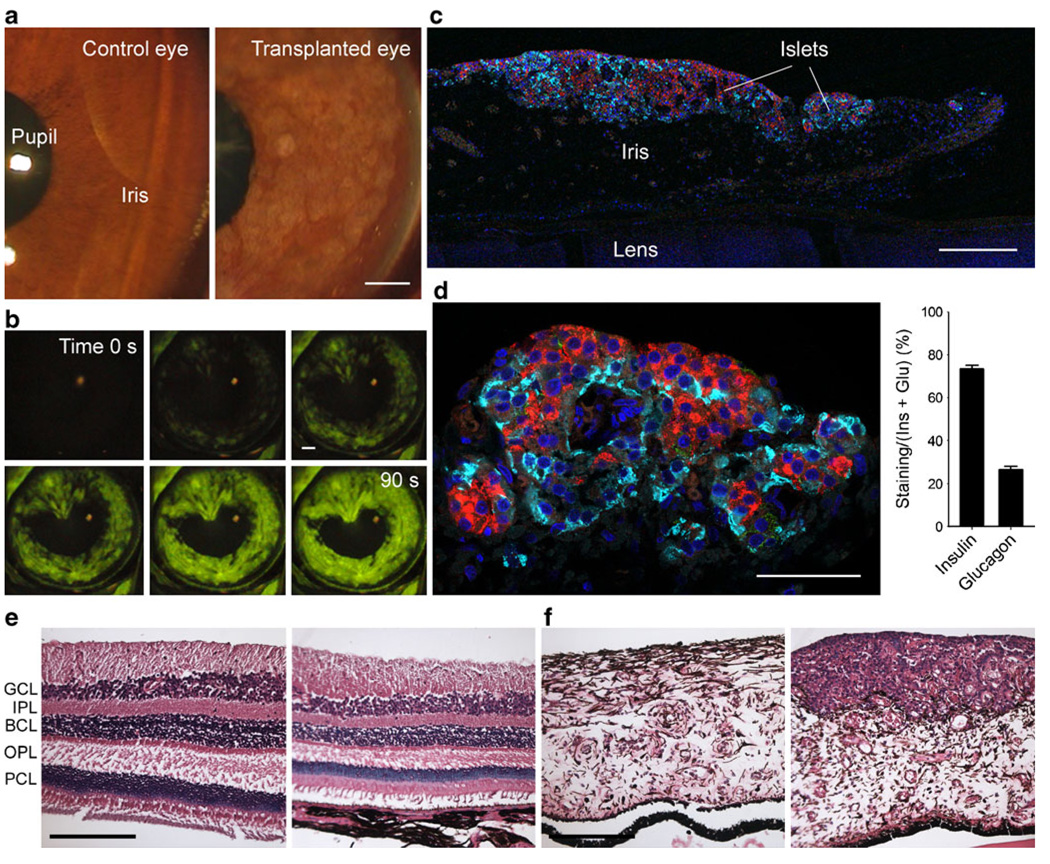

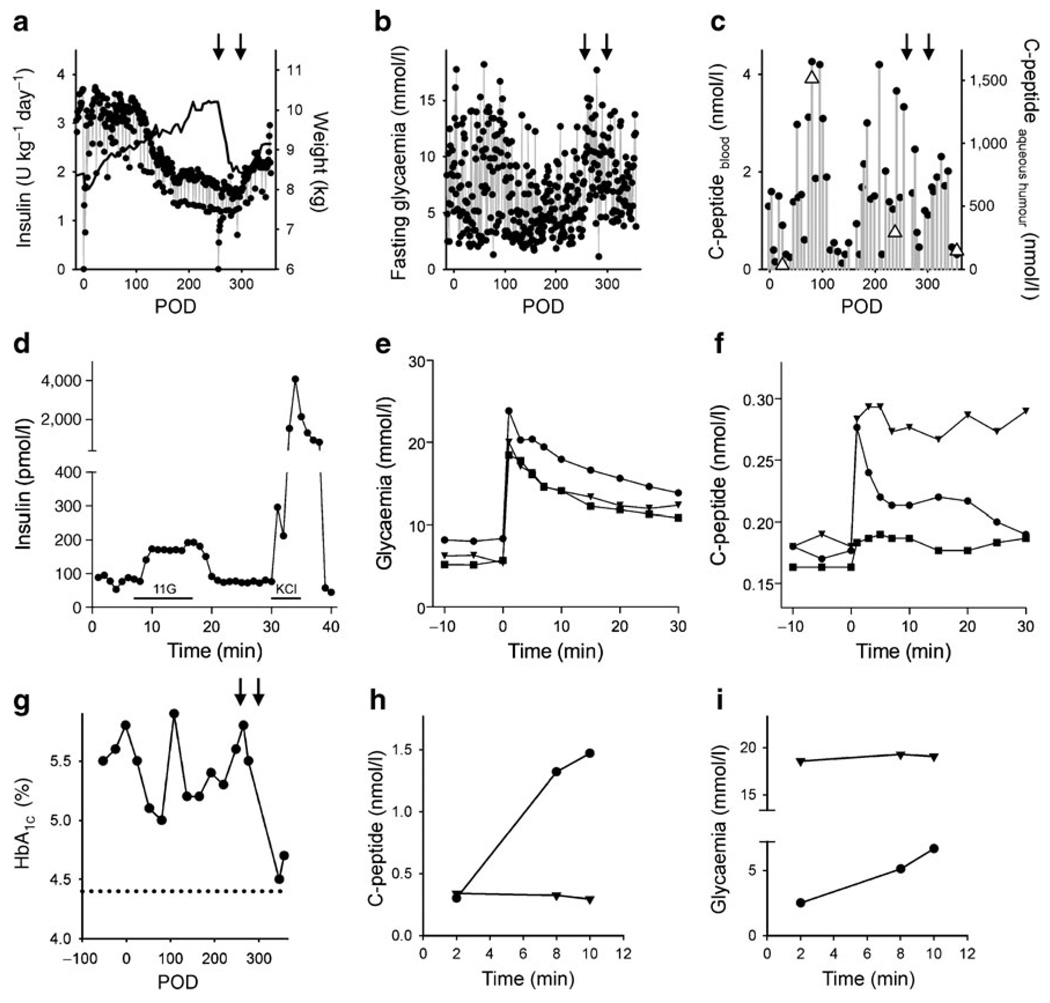

Islets were engrafted onto the iris, covering ~80% of the iris surface (Fig. 1a). Over the next 357 days there was little loss of islet mass (<15%). Angiographic studies of the anterior chamber showed that islet grafts were strongly vascularised as early as POD 24 (Fig. 1b). The cytoarchitecture of transplanted islets was preserved, and the cellular composition was similar to that of the islets before transplantation (Fig. 1c, d). Graft function was monitored using the following clinical variables: pre- and post-transplant exogenous insulin requirements, HbA1c (a measure of the average plasma glucose concentration over prolonged periods of time), fasting blood glucose levels, the ratio of C-peptide to fasting blood glucose levels, and C-peptide secretion after intravenous glucose or glucagon challenges. Exogenous insulin requirements started decreasing at 3 months after transplantation and stayed lower (~60% of pre-transplant requirements) for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 2a). In parallel with the reduction of insulin requirements, fasting glycaemia became less erratic, indicating improved and more stable metabolic control (Fig. 2b). C-peptide levels (a measure of endogenous insulin production) exceeding 2 nmol/l were measured in the circulation at 3 months after transplantation. Very high levels of C-peptide (>1,000 nmol/l) were detected in the aqueous humour of the transplanted eye, and these values co-varied with blood C-peptide values (Fig. 2c). Increases in C-peptide levels could be induced in response to intravenous glucose challenges, and the magnitude of the response increased progressively with time after transplantation (Fig. 2f). The glucose excursions in these tests further indicated that glycaemia was actively controlled (Fig. 2e). HbA1c decreased gradually after transplantation to reach a nadir at 3 months (Fig. 2g). Intraocular islet grafts thus manifestly contributed to glucose homeostasis and improved glycaemia control.

Fig. 1.

Pancreatic islets engrafted on the iris in the anterior chamber of the eye of a baboon model for type 1 diabetes. a Digital images of the anterior chamber of the eye of a baboon showing islet grafts on the iris (right). The anterior chamber and the cornea were as clear as those of the control, non-transplanted eye (left). In the transplanted eye, the angle was not obstructed by islets. b Fluorescein angiography performed at POD 24 revealed islet vascularisation. c Confocal image of a section of the anterior segment of the eye explanted at necropsy shows engraftment of islets on the iris. Insulin-labelled beta cells (red) and glucagon-labelled alpha cells (cyan) formed a distinct layer fully fused with the iris tissue. d The cytoarchitecture of intraocular islet grafts was preserved as seen by a typical ratio of beta cells to alpha cells (quantified on right panel as area of cell specific staining/[area of insulin staining+area of glucagon staining]×100, [n=47 sections]). e Vertical sections of the control, non-transplanted (left) and the transplanted eye (right) showing that the retina in the experimental eye is pristine (haematoxylin and eosin staining). BCL, bipolar cell layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; PCL, photoreceptor cell layer. f Sections of the iris in the transplanted eye (right) showing islets engrafted on the iris, whose morphology is very similar to that of the iris of the control, nontransplanted eye (left) (haematoxylin and eosin staining). Scale bars, 200 µm (a–c, e, f) and 50 µm (d)

Fig. 2.

Pancreatic islet transplantation into the anterior chamber of the eye improved glycaemic control in a baboon model for diabetes. a Daily insulin requirements before and after islet transplantation. The baboon gained weight after transplantation (black line) until it was pancreatectomised (left-hand arrow in a–c, and g). Weight gain was seen again after a second islet transplantation (right-hand arrow in a–c, and g). b Fluctuations in fasting blood glucose decreased after transplantation, increased after pancreatectomy, and stabilised again after a second islet transplantation. c Plasma C-peptide levels increased after islet transplantation. C-peptide levels were much higher in the aqueous humour of the eye (triangles), but co-varied with plasma C-peptide levels. d Perifusion studies performed on isolated islets before transplantation showed insulin responses to high glucose (11 mmol/l; 11G) and KCl depolarisation (25 mmol/l). Bars under trace indicate stimulus applications. e, f Glucose excursions (e) and C-peptide blood levels (f) during IVGTTs performed at POD 54 (squares), POD 175 (triangles), and POD 271 (circles). g HbA1c levels decreased after islet transplantation and, after the second islet transplantation, almost reached levels measured in the same baboon before diabetes was induced (dotted line). h, i An injection of glucagon to stimulate insulin secretion (glucagon challenge) showed that the insulin secretory response was abolished after removal of the intraocular islet grafts. h Plasma C-peptide levels increased during a glucagon challenge before (circles) but not after removal of the transplanted eye (triangles) and glycaemia did not change with the glucagon challenge after removal of the transplanted eye, indicating that the baboon had lost responsiveness to glucagon (i)

To eliminate a putative contribution of residual insulin secretion by endogenous islets surviving the streptozotocin treatment, we pancreatectomised the baboon on POD 256. While transient changes in glycaemia and weight loss were associated with the procedure, C-peptide was still detectable in the circulation (>2 nmol/l; Fig. 2c) and its secretion could be stimulated with glucose (Fig. 2f), confirming that intraocular islet grafts were fully functional and had indeed contributed most of the detectable blood C-peptide. To further improve glycaemic control, we performed a second allogeneic islet transplantation into the same eye on POD 292. Of the ~18,000 islet equivalents (2,100 islet equivalents/kg) newly infused into the eye, only a few could be seen engrafting on the first layer of previously engrafted islets. Nevertheless, compared with post-pancreatectomy values, C-peptide levels increased after the second islet transplantation (Fig. 2c). Importantly, HbA1c levels continued to decrease, reaching the lowest values at POD 347 (Fig. 2g).

We ended the experiment at the first signs of islet dysfunction (i.e. a sharp increase in insulin requirements and fasting blood glucose). On POD 357, the day of necropsy, we performed glucagon challenges before and after removal of the transplanted eye. In this definitive test for islet graft function, C-peptide secretion could be elicited and detected before but not after removing the eye with islet grafts (Fig. 2h). The baboon returned to hyperglycaemia immediately after removal of the eye (Fig. 2i).

Ophthalmological examination

Over the course of the experiment, we conducted eight complete examinations of both the transplanted eye and the contralateral, non-transplanted, eye using slit-lamp examinations and intraocular pressure measurements by standard tonometry (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1). Although direct visual functional measurements of the transplanted eye were not possible, the baboon never showed behavioural signs suggestive of blindness. Moreover, no abnormal afferent pupillary defects associated with optic nerve damage were observed. There was no difference in the intraocular pressure between both eyes at any time point (7.6±1.3 mmHg in transplanted eye vs 9.7±1 in non-transplanted eye; mean±SEM), consistent with the observation that the angle was always clear and unobstructed. The cornea of the transplanted eye was always clear and the conjunctiva and aqueous humour were quiet, that is, there were no signs of endophthalmitis. At POD 7, a small portion of the iris started adhering to the lens (posterior synechia), but the synechia stabilised thereafter. It was only after the second islet transplantation, at POD 306 (ESM Table 1), that we observed a non-clinically significant anterior capsule cataract. There was no pathological neovascularisation in either the anterior or the posterior segments of the eye, and the optic nerve and the retina appeared normal, based on pathological examination after necropsy (Fig. 1e, f).

Discussion

Given the difficulties with current implantation sites in connection with clinical islet transplantation to treat patients with type 1 diabetes, we explored the anterior chamber of the eye as a therapeutic transplantation site. Here we show that pancreatic islets engraft and function in the eye of a baboon model for diabetes, contributing to glycaemic control. Importantly, there were no major ophthalmic complications and no evidence of sympathetic ophthalmia in the contralateral non-transplanted eye. Although we recognise that a limitation of this study is our ability to directly test if visual function was affected by the transplantation of islet cells into the eye, there are three points of indirect evidence that suggest otherwise. First, the baboon never showed behavioural evidence suggestive of poor vision or blindness during the time of the experiment. Second, no abnormal afferent pupillary defect or reflex was observed. Third, the histological analysis of the eyes was completely normal with no signs of tissue damage that would prevent the eye from functioning normally. In fact, these histological data also prove that the presence of functioning pancreatic islets in the anterior chamber is not detrimental to the eye. The only ophthalmic pathology observed was the formation of a non-clinically significant cataract in the transplanted eye, which is a problem that can be treated effectively. Cataract is the most common cause of poor vision in the world, and cataract extraction with new microsurgical techniques and intraocular lens implantation is the standard of care for cure. Moreover, patients with diabetes can successfully be operated for cataract formation when these become clinically significant, with excellent outcomes even if patients have diabetic ocular involvement. Therefore, if a cataract develops in the transplanted eye, it can be surgically removed and treated.

Major advantages of the anterior chamber of the eye as a clinical transplantation site include the simple implantation procedure, the potential for non-invasive monitoring of the grafts, the lack of major islet loss, and the potential for reducing systemic immune suppression by using direct and efficient local delivery. Although not explored here, we envisage that this procedure will accomplish two goals in the care of patients with type 1 diabetes. First, it can substantially improve patient quality of life by improving glycaemic control with reduced daily insulin requirements and avoiding hypoglycaemic episodes. Second, islet graft survival in other transplantation sites can be enhanced by the induction of systemic tolerance to alloantigens through the purported immune privilege properties of the anterior chamber of the eye [13–15]. We strongly believe that the success in achieving glycaemic control in the absence of ophthalmological complications provides support for further studies aimed at translating this approach into the clinical realm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank W. Diaz, J. Geary and M. Carcamo for animal care, and A. Rabassa and E. Poumian-Ruiz for islet isolation. This work was supported by the Diabetes Research Institute Foundation (DRIF), Henri and Flore Lesieur Foundation (to J. M. Parel) and grants NIH/NEI P30 EY014801 (centre grant, BPEI), NIH/NIDDK R03 DK075487 and NIH/NIDDK R56 DK084321 (to A. Caicedo), NIH R01 EB008009 (to C. Ricordi), the Swedish Research Council, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Swedish Diabetes Association and the Family Erling-Persson Foundation (to P. O. Berggren). The anti-CD154 antibody used was provided by the Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource (RR016001, NIAID contract HHSN272200900037C).

Abbreviation

- POD

Postoperative day

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2091-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Duality of interest The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contributor Information

V. L. Perez, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA

A. Caicedo, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA Diabetes Research Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136, USA.

D. M. Berman, Diabetes Research Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136, USA

E. Arrieta, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA

M. H. Abdulreda, Diabetes Research Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136, USA

R. Rodriguez-Diaz, Diabetes Research Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136, USA

A. Pileggi, Diabetes Research Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136, USA

E. Hernandez, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA

S. R. Dubovy, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA

J. M. Parel, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA

C. Ricordi, Diabetes Research Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136, USA The Rolf Luft Research Center for Diabetes and Endocrinology, Karolinska Institutet, 17177, Stockholm, Sweden.

N. M. Kenyon, Diabetes Research Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136, USA

N. S. Kenyon, Email: NKenyon@med.miami.edu, Diabetes Research Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136, USA.

P. O. Berggren, Email: per-olof.berggren@ki.se, Diabetes Research Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33136, USA; The Rolf Luft Research Center for Diabetes and Endocrinology, Karolinska Institutet, 17177, Stockholm, Sweden; Division of Integrative Biosciences and Biotechnology, WCU Program, Pohang University of Science and Technology, Pohang, South Korea.

References

- 1.Shapiro A, Lakey J, Ryan E, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:230–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro A, Ricordi C, Hering B, et al. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1318–1330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harlan D, Kenyon N, Korsgren O, Roep B, Society IoD. Current advances and travails in islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2009;58:2175–2184. doi: 10.2337/db09-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korsgren O, Lundgren T, Felldin M, et al. Optimising islet engraftment is critical for successful clinical islet transplantation. Diabetologia. 2008;51:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0868-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pileggi A, Molano R, Ricordi C, et al. Reversal of diabetes by pancreatic islet transplantation into a subcutaneous, neovascularized device. Transplantation. 2006;81:1318–1324. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000203858.41105.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaffanjon P, Kenyon N, Ricordi C, Kenyon N. Omental anatomy of non-human primates. Surg Radiol Anat. 2005;27:287–291. doi: 10.1007/s00276-005-0329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berman D, O’Neil J, Coffey L, et al. Long-term survival of nonhuman primate islets implanted in an omental pouch on a biodegradable scaffold. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:91–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Speier S, Nyqvist D, Köhler M, Caicedo A, Leibiger I, Berggren P. Noninvasive high-resolution in vivo imaging of cell biology in the anterior chamber of the mouse eye. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1278–1286. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speier S, Nyqvist D, Cabrera O, et al. Noninvasive in vivo imaging of pancreatic islet cell biology. Nat Med. 2008;14:574–578. doi: 10.1038/nm1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berman D, Cabrera O, Kenyon N, et al. Interference with tissue factor prolongs intrahepatic islet allograft survival in a nonhuman primate marginal mass model. Transplantation. 2007;84:308–315. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000275401.80187.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenyon N, Fernandez L, Lehmann R, et al. Long-term survival and function of intrahepatic islet allografts in baboons treated with humanized anti-CD154. Diabetes. 1999;48:1473–1481. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.7.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenyon NS, Chatzipetrou M, Masetti M, et al. Long-term survival and function of intrahepatic islet allografts in rhesus monkeys treated with humanized anti-CD154. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8132–8137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez V, Biuckians A, Streilein J. In-vivo impaired T helper 1cell development in submandibular lymph nodes due to IL-12 deficiency following antigen injection into the anterior chamber of the eye. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2000;8:9–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niederkorn J. See no evil, hear no evil, do no evil: the lessons of immune privilege. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:354–359. doi: 10.1038/ni1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niederkorn J. The induction of anterior chamber-associated immune deviation. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2007;92:27–35. doi: 10.1159/000099251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.