Abstract

Retroviruses can cause diseases such as AIDS, leukemia, and tumors, but are also used as vectors for human gene therapy. All retroviruses, except foamy viruses, package two copies of unspliced genomic RNA into their progeny viruses. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of retroviral genome packaging will aid the design of new anti-retroviral drugs targeting the packaging process and improve the efficacy of retroviral vectors. Retroviral genomes have to be specifically recognized by the cognate nucleocapsid domain of the Gag polyprotein from among an excess of cellular and spliced viral mRNA. Extensive virological and structural studies have revealed how retroviral genomic RNA is selectively packaged into the viral particles. The genomic area responsible for the packaging is generally located in the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR), and contains dimerization site(s). Recent studies have shown that retroviral genome packaging is modulated by structural changes of RNA at the 5′ UTR accompanied by the dimerization. In this review, we focus on three representative retroviruses, Moloney murine leukemia virus, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and 2, and describe the molecular mechanism of retroviral genome packaging.

Keywords: retrovirus, genome, RNA, NC, structure, dimerization, packaging

Introduction

Retroviruses belong to a diverse family of RNA viruses causing various diseases, such as leukemia, tumors, demyelinization disease, and AIDS. One unique feature of retroviruses is their integration of reverse transcribed genome into the host chromosome as a provirus. Some retroviruses have been engineered to function as vectors for the delivery of corrective human genes, and vectors derived from the Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) have been used for the treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency (Nelson et al., 2003). An understanding of the molecular mechanism of retroviral replication is needed for the development of anti-retroviral therapies as well as retroviral vectors.

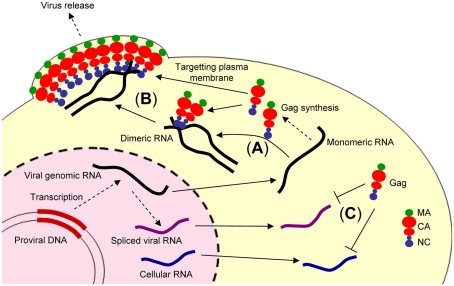

All retroviruses, except foamy viruses, package two copies of full-length genomic RNA into progeny viruses, the genomic RNA having to be specifically selected from among a large amount of spliced viral and cellular RNA (Figure 1; Berkowitz et al., 1996). Virological and genetic studies have shown that the specific packaging of retroviral genomic RNA is mediated via interaction with the nucleocapsid (NC) domain of the Gag polyprotein (Rein, 1994; Berkowitz et al., 1996; Jewell and Mansky, 2000; Greatorex, 2004; Paillart et al., 2004b; Russell et al., 2004). Retroviral NC domains are generally highly basic and contain one or two zinc knuckle motifs composed of C–C–H–C arrays (Henderson et al., 1981; Summers et al., 1990; Kodera et al., 1998; D’Souza and Summers, 2004; Matsui et al., 2007). The zinc knuckles form a metal-coordinating “reverse turn” stabilized by NH–S hydrogen bonds. Most retroviral zinc knuckles contain a hydrophobic cleft on the surface of the mini globular domain, recognizing specific structures of RNA or DNA. The basic N- and C-terminal tails of NC domains are conformationally labile (Summers et al., 1992).

Figure 1.

Illustration showing retroviral genome packaging events. The retroviral genomic RNA is exported from the nucleus to cytoplasm and used as the mRNA for ribosomal synthesis of the Gag and Gag–Pol polyproteins. (A) The retroviral genomic RNA promotes conversion of the dimeric form of genomic RNA via the NC domain of Gag. (B) The Gag and retroviral genomic RNA complex is transported to the plasma membrane, where further assembly and budding occur, mediated by the myristoylated MA domain of Gag. (C) In contrast, spliced viral RNA or cellular RNA is not bound to the NC domain of Gag or may be bound to a small number of Gag polyproteins insufficient for trafficking to the plasma membrane.

Retroviral genomes are known to be non-covalently dimerized in progeny virions (Rizvi and Panganiban, 1993). The region responsible for retroviral genome packaging is generally located between the splice donor (SD) site and the gag start codon in the 5′ leader region (Watanabe and Temin, 1982; Mann and Baltimore, 1985; Lever et al., 1989; Mansky et al., 1995; Kaye and Lever, 1999; Browning et al., 2003; Mustafa et al., 2004). Interestingly, the packaging signal generally overlaps with the site of dimerization (Paillart et al., 1996, 2004a; Greatorex, 2004; Hibbert et al., 2004), implying that the packaging event is coupled with genome dimerization (Russell et al., 2004). Inhibition of genome dimerization by deletion or insertion mutations at dimer initiation sites (DIS) causes a drastic reduction in genome packaging (Berkhout, 1996; Paillart et al., 1996; Laughrea et al., 1997; McBride and Panganiban, 1997). Moreover, studies with mutant viruses containing two 5′ untranslated region (UTR) packaged monomeric genome, indicate that genome packaging is achieved by the interaction of two 5′ UTRs (Sakuragi et al., 2001, 2002). Experiments with MoMLV have indicated that the conformational change induced by genome dimerization causes the exposure of NC-binding sites (D’Souza and Summers, 2004). A recent study also indicated that human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) employs a similar strategy for genome packaging (Lu et al., 2011a). In addition, several structures have been determined among complexes of NC and RNA fragments functioning in genome packaging, which provide the molecular mechanism for retroviral genome recognition of NC at the atomic level. In this review, we describe the molecular mechanisms of retroviral genome packaging.

Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus

Moloney murine leukemia virus is a simple prototypical retrovirus, with a single splicing event producing a spliced RNA for synthesizing Env during its life cycle. MoMLV is one of the most extensively studied retroviruses. Nucleotides 215–565 of the 5′ UTR have been identified as a responsible site for genome packaging (Ψ-site; Mann et al., 1983). The secondary structure of the 5′ UTR was determined by RNase protection assays using cross-linking reagents combined with computational analyses such as phylogenetic and free-energy calculations (Tounekti et al., 1992; Mougel et al., 1993). The monomeric Ψ-site is composed of a series of RNA stem-loops. Differences in RNase protection patterns were observed for the dimeric Ψ-site (Tounekti et al., 1992; Mougel et al., 1993; D’Souza and Summers, 2005). It was reported that a dimerized RNA fragment containing the entire Ψ-site was bound to a significant number of NCs (Miyazaki et al., 2010a). Meanwhile, a mutant RNA fragment that inhibited dimerization was bound to a few NCs. Thus, dimerization-dependent genome packaging is strongly indicated in MoMLV.

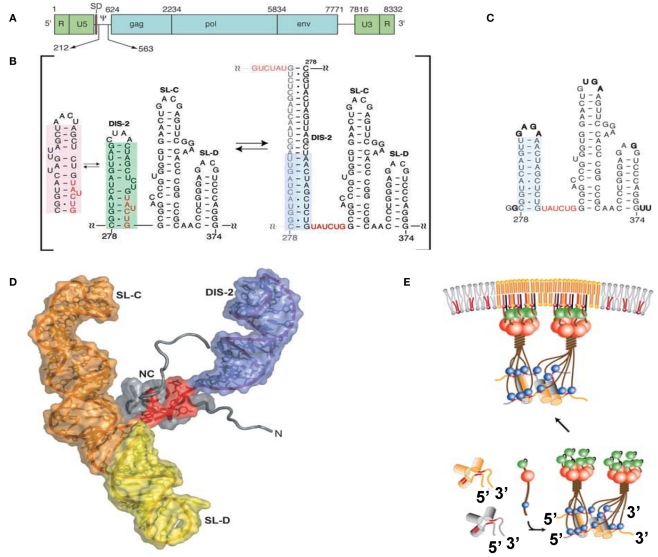

The minimum region sufficient for genome packaging is referred to as the core encapsidation signal (ΨCES), though a virus containing only ΨCES exhibits less efficient packaging than a virus containing the entire Ψ-site (Bender et al., 1987; Adam and Miller, 1988; Murphy and Goff, 1989; Mougel and Barklis, 1997; Yu et al., 2000). ΨCES consists of three RNA stem-loops (DIS-2, SL-C, and SL-D, see Figures 2A,B). DIS-2 harbors a palindromic sequence and is able to convert heterologous extended dimers. The structure of NC in a complex with a mutant RNA of ΨCES mimicking the dimer-like conformation was determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Figures 2C,D; D’Souza and Summers, 2004). UAUCUG residues sequestered by base-pairing in the monomeric conformation are exposed as a linker by dimerization. NC recognizes the UCUG sequence. NC is a highly basic protein, consisting of a zinc knuckle motif and labile tails in both the N- and C-terminus. Biophysical study indicated that NC specifically recognizes RNA fragments including a Py (C or U) – Py-Py-G sequence (Dey et al., 2005). The interface of NC–UCUG is complementary in both shape and charge (D’Souza and Summers, 2004; Dey et al., 2005). The guanosine base attaches to the deep hydrophobic pocket of the zinc knuckle via hydrophobic and hydrogen bonds. The three upstream nucleotides make contact with hydrophobic residues on the surface of the zinc knuckle.

Figure 2.

(A) Genomic organization of MoMLV. (B) Secondary structure of the core encapsidation signal (ΨCES). Dimerization of DIS-2 induces a frame shift, exposing a UCUG element as a linker. (C) Secondary structure of mutant ΨCES that mimics the dimer-like conformation. (D) The complex of NC and mutant ΨCES. (E) Hypothetical mechanism for the genome packaging of MoMuLV. Upon dimerization, SL–CD exhibits a cross-kissing interaction, promoting the proximity of NC-binding sites. The SL–CD dimer functions as a scaffold that facilitates the Gag–Gag interaction. The ribonucleoprotein complex is transported to the plasma membrane. Reprinted with permission from [(A–D): D’Souza and Summers, 2004; (E): Miyazaki et al., 2010b].

SL-C and SL-D, which are part of ΨCES, promote genome packaging (Mougel et al., 1996; Mougel and Barklis, 1997; Fisher and Goff, 1998). Both are highly conserved among gamma-retroviruses and contain GACG loops (Konings et al., 1992; Kim and Tinoco, 2000; D’Souza et al., 2001). A stem loop RNA fragment containing the GACG tetra-loop has a unique property (Kim and Tinoco, 2000). The C and G (3′) residues of the loop undergo intermolecular base-pairing (kissing interactions). This property of the stem loop containing GACG has led to speculation that SL-C and SL-D function in genome dimerization (Kim and Tinoco, 2000; D’Souza et al., 2001; Hibbert et al., 2004). Interestingly, the RNA fragment of SL-C forms two alternative conformations (one containing the GACG tetra-loop and the other, a CGAGU loop; Miyazaki et al., 2010b). NMR data showed that SL–CD was in a state of equilibrium between kissing and non-kissing interactions even at a high sample concentration and physiological ion-strength. The two alternative conformations of SL-C may regulate genome dimerization though the biological meaning of this is not yet clear.

The tertiary structure of a RNA fragment of a SL–CD mutant locking to form a single conformation containing the GACG terra-loop was determined by NMR spectroscopy and confirmed by Cryo-electron tomography (Miyazaki et al., 2010b). The structure revealed that SL–CD is dimerized by intermolecular cross-kissing (SL-C to SL-D′ and SL-D to SL-C′). These intermolecular cross-kissing interactions were also proposed based on selective 2′-Hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE; Gherghe and Weeks, 2006; Gherghe et al., 2010). In addition, SL-C and SL-D stack end to end. Consequently, the two residues at the 5′-end of the SL–CD dimer are separated by ∼20 Å. There are two UCUG sequences just upstream of SL-C. The intermolecular kissing interactions of SL-C and SL-D induce the proximity of four of the NC-binding sites. The genomic RNA has been suggested to promote the retroviral Gag/Gag interaction (Dawson and Yu, 1998; Burniston et al., 1999; Campbell and Rein, 1999; Cimarelli et al., 2000; Sandefur et al., 2000; Khorchid et al., 2002; Huseby et al., 2005). Both the DIS DIS-1 and DIS-2 are followed by two UCUG elements. The abundance and proximity of exposed UCUG and related elements within the dimeric 5′ UTR may facilitate Gag–Gag interactions (Figure 2E).

Of note, a totally different monomeric structure for a portion of the Ψ-site (nucleotides 205–374) was proposed based on SHAPE (Gherghe and Weeks, 2006), where the RNA region spanning nucleotides 231–315 forms a large stem-loop structure, which contains residues corresponding to DIS-2. SL-C also differed from the structure previously reported, where the bottom of the stem is unstructured. It is suggested that the intermolecular kissing interactions of SL-C and SL-D induce the conformational change of SL-C and promote the dimerization of DIS-2. The difference in RNA structures may be due to the difference of RNA fragments used in those studies.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1

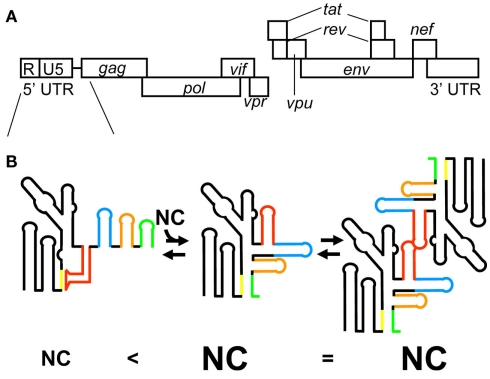

Virological studies have indicated the HIV-1 5′ leader region including the entire 5′ UTR and a portion of the gag coding region to be involved in genome packaging (Lever et al., 1989; Aldovini and Young, 1990; Clavel and Orenstein, 1990; Poznansky et al., 1991; Buchschacher and Panganiban, 1992; Kim et al., 1994; Luban and Goff, 1994; Parolin et al., 1994; Berkowitz et al., 1995; McBride and Panganiban, 1996, 1997; McBride et al., 1997; Harrison et al., 1998; Helga-Maria et al., 1999; Clever et al., 2002; Russell et al., 2002; Sakuragi et al., 2003, 2007). The 5′ leader RNA consists of a series of RNA stem-loops referred to as the transacting responsive element (TAR), primer-binding site (PBS), polyadenylation signal [poly(A)], DIS, SD, and residues spanning the gag start codon (AUG; Figure 3; Hayashi et al., 1992, 1993; Baudin et al., 1993; Skripkin et al., 1994; Clever et al., 1995; McBride and Panganiban, 1996, 1997; Clever and Parslow, 1997; Harrison et al., 1998; Damgaard et al., 2004; Wilkinson et al., 2008; Watts et al., 2009). It has been suggested that an RNA fragment of the 5′ leader RNA has two alternative conformations, whose secondary structure has been determined by chemical probing assays (Berkhout and van Wamel, 2000). One conformation is referred to as the long distance interaction (LDI) structure, in which the residues of DIS are base-paired with those of poly(A) and SD. The other conformation is referred to as the branched multiple hairpin structure (BMH), in which the residues of DIS, SD, and Ψ form a stem-loop structure as indicated before (Huthoff and Berkhout, 2001). In addition, the residues of AUG form base-pairs with the residues of the unique 5′ region (U5). Of note, it has been proposed a lot of secondary structural models for the 5′ leader (Lu et al., 2011b). NC catalyzes LDI to BMH. DIS is exposed as a stem-loop in BMH, which promotes the kissing dimer conformation and following the genome packaging event. However, the BMH structure is mostly observed in HIV-1-infected cells, but the LDI structure fails to be detected (Paillart et al., 2004a). Thus, the biological significance of the BMH/LDI riboswitch model remains to be elucidated.

Figure 3.

(A) Genomic organization of HIV-1. (B) The latest model for HIV-1 genome packaging. Conformational change of RNA in the 5′ leader region regulates genome dimerization and genome packaging. The stem-loop structure of AUG causes sequestering of DIS via long range interaction with the residues of U5, resulting in the inhibition of HIV-1 genome dimerization (left). In this conformation of the 5′ leader RNA, a small number of NCs are capable of binding the 5′ leader RNA. In contrast, the interaction of AUG with U5 residues promotes genome dimerization via exposure of DIS (center). In this conformation of the 5′ leader RNA, a greater number of NCs are capable of binding the 5′ leader RNA. The different RNA elements in the 5′ leader region are color coded: DIS (red), SD (blue), Ψ (orange), and AUG (green).

RNA fragments of DIS, SD, Ψ, and AUG have been studied extensively since the region from DIS to AUG was initially identified as a Ψ-site (Lever et al., 1989; Aldovini and Young, 1990; Clavel and Orenstein, 1990; Poznansky et al., 1991; Harrison and Lever, 1992; Kim et al., 1994; McBride and Panganiban, 1996, 1997; Harrison et al., 1998). The RNA fragments of SD and Ψ are bound to NC with high affinity (Clever et al., 1995; Amarasinghe et al., 2000a,b), whereas the RNA fragments of DIS and AUG are bound to NC with relatively low affinity (Darlix et al., 1990; Amarasinghe et al., 2001; Lawrence et al., 2003). The RNA fragment of Ψ is bound to NC with the highest affinity (Kd = 100 nM) among these four RNA fragments (Amarasinghe et al., 2000b). Deletion or destabilization of the stem of Ψ results in a significant reduction in genome packaging efficiency (Clever and Parslow, 1997; McBride and Panganiban, 1997). This indicates that the stem-loop structure of Ψ is important for genome packaging. Ψ consists of a GGAG tetra-loop and a stem. The structure of the ribonucleoprotein complex NC–Ψ has been determined by NMR spectroscopy. Guanosine residues of the GGAG tetra-loop are inserted into the hydrophobic clefts of both the N- and C-terminal zinc knuckles (De Guzman et al., 1998). The adenosine residue of the loop packs against the N-terminal zinc knuckle and an N-terminal alpha-helix domain binds to the major groove of the RNA stem. Thus, overall, NC residues are involved in binding with Ψ RNA, by which the tight binding of NC–Ψ is achieved. In addition, the intra-molecular interaction of two zinc knuckles may help to stabilize the complex of NC and Ψ RNA.

The RNA fragment of SD is also bound to NC with high affinity though the binding is slightly weaker than that of Ψ (Amarasinghe et al., 2000a). SD RNA contains a GGUG tetra-loop and a stem containing a characteristic AUA triple base-pairing structure. All guanosine residues of the loop inserted into the hydrophobic clefts of zinc knuckles as observed in the complex of NC and Ψ RNA. A major structural difference between the NC and SD RNA complex and the NC and Ψ RNA complex is the orientation of the N-terminal alpha-helix domain of NC. The domain does not stick into SD RNA and is exposed outside of SD RNA. The N-terminal zinc knuckle interacts with an AUA triple base-pairing motif in the minor groove of the SD RNA stem. A mutant virus with a disrupted lower stem structure of SD exhibited a 20% reduction in genome packaging compared with the wild-type virus, despite the robust binding of Ψ RNA and NC (McBride and Panganiban, 1997). Further study will be needed to clarify the link between the tight binding of SD RNA with NC and its biological relevance.

Dimer initiation site contains a GC-rich palindromic sequence and an inner bulge (G-AGG) in the middle of the stem. This inner bulge is recognized by NC. As described above, guanosine residues not in base-pairs possibly play an important role in the binding to NC (Mihailescu and Marino, 2004). However, the binding affinity of NC–DIS is relatively weak (approximately five times weaker than that of NC–SD/ Ψ; Lawrence et al., 2003). NC catalyzes the conversion of DIS from a kissing dimer to a more stable extended duplex conformation (Darlix et al., 1990; Feng et al., 1996). Virological studies have suggested that interaction between the two 5′ UTR is required for genome packaging (Sakuragi et al., 2001, 2002). A very recent study indicated that genome dimerization is controlled by a unique strategy (Figure 3B). RNA containing the entire 5′ UTR and the first 21 residues of the gag coding region forms two alternative conformations (Lu et al., 2011a). In one conformation, DIS is sequestered via a long range interaction with U5, which inhibits genome dimerization. In the other conformation, DIS is exposed by release from the interaction with U5, which promotes genome dimerization.

AUG was believed to form a stem-loop structure, consisting of a GAGA tetra-loop and an unstable short stem containing two wobble G–U base-pairs (Amarasinghe et al., 2001). The GAGA tetra-loop is a type of GNRA (N is A, C, G, or U; R is A or G) tetra-loop, which is frequently observed in ribosomal RNA. GNRA tetra-loop helps fold stem-loops, and one Watson–Crick base-pair is enough to close off the RNA fragment. However, it has been suggested that AUG does not form a stem-loop structure and a portion of the residues of AUG may have a long range interaction with the residues of U5 as indicated in the BMH structure (Abbink and Berkhout, 2003; Damgaard et al., 2004; Spriggs et al., 2008; Wilkinson et al., 2008; Watts et al., 2009). Studies using deletion mutants indicate that the entire 5′ UTR and gag coding regions are important for genome packaging (Buchschacher and Panganiban, 1992; Luban and Goff, 1994; Parolin et al., 1994; Clever et al., 2002; Russell et al., 2002). Evidence of the importance of long range interactions for genome packaging was reported recently (Figure 3B; Lu et al., 2011a). It shows that AUG regulates genome dimerization. AUG forms two alternative conformations. One is a stem-loop conformation as initially suggested. The other is a complex with the residues of U5. The interaction of AUG with U5 leads to the exposure of DIS, promoting genome dimerization. Of note, when the residues of AUG form a stem-loop structure, in which the dimerization of the 5′ leader RNA is inhibited, a small number of NCs can bind the 5′ leader RNA (Figure 3B). On the other hand, when the residues of AUG interact with the residues of U5, a greater number of NCs can bind the 5′ leader RNA. Thus, AUG has a critical role in genome dimerization and genome packaging. In addition, it is suggested that the residues ranging from the end of Ψ to the start of AUG form base-pairing with the residues of the 3′ terminus of PBS. That is also proposed by earlier work Lu et al. (2011b). In fact, Sakuragi et al. (2003, 2007) indicate these residues are indispensable both for genome dimerization and genome packaging in vivo.

It is suggested that the HIV-1 genome’s dimerization and packaging are controlled by dynamic changes of the 5′ leader’s conformation as indicated in MoMLV (D’Souza and Summers, 2004; Miyazaki et al., 2010a; Lu et al., 2011a). Ψ is indicated to be important for genome packaging, however, it is not clear how Ψ works in the model suggested by Lu et al. (2011a). This will be the next question to answer for a better understanding of the molecular mechanism of HIV-1 genome packaging.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 2

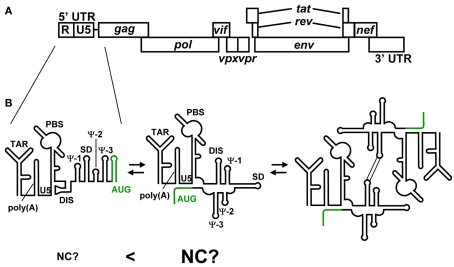

Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) is one of two human lentiviruses that can cause AIDS. HIV-1 and HIV-2 exhibit approximately 55% nucleotide sequence identity. However, they differ significantly in their 5′ UTR. For example, the 5′ UTR of HIV-2 (HIV-2ROD) consists of 535 nucleotides, whereas that of HIV-1 (HIV-1NL432) consists of 335 nucleotides. The 5′ leader RNA of HIV-2 contains three unique RNA elements referred to as Ψ-1, Ψ-2, and Ψ-3 in addition to a series of RNA stem-loops, TAR, poly(A), PBS, DIS, SD, and AUG, those are commonly observed in the 5′ leader of HIV-1 (Figure 4; Berkhout, 1996). The structure of HIV-2 NC also exhibits some different features. A major difference in NC between HIV-2 and HIV-1 is the structure of the N-terminal flanking domain (Berkhout, 1996; Jewell and Mansky, 2000; Matsui et al., 2009). The N-terminal domain of HIV-1 NC forms an alpha-helix, whereas that of HIV-2 NC is too short to do so. Another difference is the intra-molecular interaction of two zinc knuckles of HIV-2 NC, by which HIV-2 NC forms a more globular structure than HIV-1 NC. These structural differences of NCs between HIV-1 and HIV-2 may affect RNA recognition.

Figure 4.

(A) Genomic organization of HIV-2. (B) Representative secondary structures predicted for the 5′ UTR of HIV-2. Variations among recent predictions for AUG (green) are shown. The residues of AUG have been suggested to form a stem-loop structure and show long range interaction with the residues of U5. It has been suggested that HIV-2 genome’s dimerization is employed the same mechanism as HIV-1. However, it remains to be clear whether NC preferentially binds the 5′ leader RNA containing the U5–AUG interaction.

It has been suggested that Ψ-3 can be bound to NC (Tsukahara et al., 1996; Damgaard et al., 1998). A study using RNase protection assays suggested that the NC–Ψ-3 ribonucleoprotein exhibited strong protection at the loop of Ψ-3. This was supported by NMR experiments. The guanosine residue of the UUAGAC loop is inserted into the hydrophobic cleft of the C-terminal zinc knuckle (Matsui et al., 2009). The N-terminal zinc knuckle does not bind the RNA fragment of Ψ-3. However, virological study has suggested that Ψ-3 is not essential for either genome dimerization or genome packaging (McCann and Lever, 1997). In agreement with that, a recent study showed that NC binds the RNA fragment of Ψ-3 with 100 times lower affinity than HIV-1 NC binds the RNA fragment of HIV-1 Ψ (Purzycka et al., 2011).

The RNA fragment of DIS is bound to NC with high affinity (Kd = 100 nM), equivalent to the affinity of HIV-1 Ψ RNA and the cognate NC (Purzycka et al., 2011). HIV-2 NC recognizes the inner bulge of DIS, and does not bind to the loop. HIV-1 DIS is weakly bound to the cognate NC (Lawrence et al., 2003; Andersen et al., 2004). Interestingly, HIV-2 TAR and poly(A) is bound to the NCs with relatively high affinity (TAR–NC Kd = 450 nM, poly(A) – NC Kd = 550 nM). All the tight NC-binding sites [DIS, TAR, and poly(A)] are located upstream of SD. The regions responsible for the genome packaging of retroviruses are generally located downstream of SD, by which the genomic RNA is selectively packaged from an excess amount of spliced viral RNA. It is suggested that HIV-2 genome packaging is primarily mediated by cis packaging mechanism (Kaye and Lever, 1999; Griffin et al., 2001; L’Hernault et al., 2007). The Gag packages genomic RNA from which it is translated. Therefore, the HIV-2 Gag is not required to distinguish the genomic RNA from viral spliced RNAs. Recent studies, however, indicated that HIV-2 genome packaging is primarily mediated by trans packaging mechanism (Ni et al., 2011). TAR contains a palindromic sequence and has been suggested to form a dimer (Berkhout et al., 1993; Andersen et al., 2004). The dimerization of TAR may also function for efficient genome packaging. Further study will be needed to determine how the RNA elements located upstream of SD are involved in genome packaging.

Despite significant differences in the recognition of NC by the 5′ leader RNA, HIV-1, and HIV-2 may employ similar mechanisms for genome packaging. Dirac et al. (2002) observed that the RNA fragment of the 5′ leader region forms two alternative conformations as observed for the HIV-1 RNA fragments of the 5′ leader region. The long range interaction of U5–AUG is observed for the BMH conformation though it is not clear whether the LDI/BMH riboswitch mechanism is utilized for genome packaging in vivo. Recent study also indicated the U5–AUG interaction by SHAPE analysis (Purzycka et al., 2011). Of note, it is suggested that the U5–AUG interaction regulates the HIV-2 genome dimerization as indicated in HIV-1 (Baig et al., 2008). Lu et al. (2011a) suggest that the 5′ leader RNA containing the U5–AUG interaction of HIV-1 is preferentially bound to the cognate NC. A major question is whether the U5–AUG interaction of HIV-2 also promotes the NC-binding to the 5′ leader RNA (Figure 4B). Phylogenetic and computational analyses suggested that the U5–AUG long range interaction is widely conserved among retroviruses (Damgaard et al., 2004). The long range interaction of U5–AUG may be important for retroviral genome dimerization and genome packaging.

Perspectives

It has been indicated that the MoMLV NC domain of Gag binds predominantly to dimeric genomes (D’Souza and Summers, 2004; Miyazaki et al., 2010a). HIV-1 was indicated to have a similar system (Lu et al., 2011a). MoMLV showed proximal NC-binding motifs in ΨCES, implying that Gag–Gag multimerization is initiated by genomic RNA (Miyazaki et al., 2010b). A major question is whether the proximity of NC-binding motifs is observed for other retroviruses such as HIV-1 and HIV-2. In addition, is the proximity of NC-binding motifs essential for retroviral genome packaging? Further study for these questions will lead to a better understanding for the molecular mechanism underlying retroviral genome packaging.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (ID no. 21390141).

References

- Abbink T. E. M., Berkhout B. (2003). A novel long distance base-pairing interaction in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA occludes the Gag start codon. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11601–11611 10.1074/jbc.M210291200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam M. A., Miller A. D. (1988). Identification of a signal in a murine retrovirus that is sufficient for packaging of nonretroviral RNA into virions. J. Virol. 62, 3802–3806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldovini A., Young R. A. (1990). Mutations of RNA and protein sequences involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging result in production of noninfectious virus. J. Virol. 64, 1920–1926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarasinghe G. K., De Guzman R. N., Turner R. B., Chancellor K. J., Wu Z. R., Summers M. F. (2000a). NMR structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to stem-loop SL2 of the psi-RNA packaging signal. Implications for genome recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 301, 491–511 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarasinghe G. K., De Guzman R. N., Turner R. B., Summers M. F. (2000b). NMR structure of stem-loop SL2 of the HIV-1 psi RNA packaging signal reveals a novel A-U-A base-triple platform. J. Mol. Biol. 299, 145–156 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarasinghe G. K., Zhou J., Miskimon M., Chancellor K. J., McDonald J. A., Matthews A. G., Miller R. R., Rouse M. D., Summers M. F. (2001). Stem-loop SL4 of the HIV-1 psi RNA packaging signal exhibits weak affinity for the nucleocapsid protein. Structural studies and implications for genome recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 314, 961–970 10.1006/jmbi.2000.5182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen E. S., Contera S. A., Knudsen B., Damgaard C. K., Besenbacher F., Kjems J. (2004). Role of the trans-activation response element in dimerization of HIV-1 RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22243–22249 10.1074/jbc.M314326200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig T. T., Strong C. L., Lodmell J. S., Lanchy J. M. (2008). Regulation of primate lentiviral RNA dimerization by structural entrapment. Retrovirology 5, 65. 10.1186/1742-4690-5-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin F., Marquet R., Isel C., Darlix J. L., Ehresmann B., Ehresmann C. (1993). Functional sites in the 5′ region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA form defined structural domains. J. Mol. Biol. 229, 382–397 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender M. A., Palmer T. D., Gelinas R. E., Miller A. D. (1987). Evidence that the packaging signal of Moloney murine leukemia virus extends into the gag region. J. Virol. 61, 1639–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout B. (1996). Structure and function of the human immunodeficiency virus leader RNA. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 54, 1–34 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60359-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout B., Essink B. B., Schoneveld I. (1993). In vitro dimerization of HIV-2 leader RNA in the absence of PuGGAPuA motifs. FASEB J. 7, 181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout B., van Wamel J. L. (2000). The leader of the HIV-1 RNA genome forms a compactly folded tertiary structure. RNA 6, 282–295 10.1017/S1355838200991684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz R., Fisher J., Goff S. P. (1996). RNA packaging. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 214, 177–218 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz R. D., Hammarskjöld M. L., Helga-Maria C., Rekosh D., Goff S. P. (1995). 5′ Regions of HIV-1 RNAs are not sufficient for encapsidation: implications for the HIV-1 packaging signal. Virology 212, 718–723 10.1006/viro.1995.1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning M. T., Mustafa F., Schmidt R. D., Lew K. A., Rizvi T. A. (2003). Delineation of sequences important for efficient packaging of feline immunodeficiency virus RNA. J. Gen. Virol. 84, 621–627 10.1099/vir.0.18886-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchschacher G. L., Panganiban A. T. (1992). Human immunodeficiency virus vectors for inducible expression of foreign genes. J. Virol. 66, 2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burniston M. T., Cimarelli A., Colgan J., Curtis S. P., Luban J. (1999). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein multimerization requires the nucleocapsid domain and RNA and is promoted by the capsid-dimer interface and the basic region of matrix protein. J. Virol. 73, 8527–8540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S., Rein A. (1999). In vitro assembly properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein lacking the p6 domain. J. Virol. 73, 2270–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimarelli A., Sandin S., Höglund S., Luban J. (2000). Basic residues in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid promote virion assembly via interaction with RNA. J. Virol. 74, 3046–3057 10.1128/JVI.74.15.6734-6740.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavel F., Orenstein J. M. (1990). A mutant of human immunodeficiency virus with reduced RNA packaging and abnormal particle morphology. J. Virol. 64, 5230–5234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clever J., Sassetti C., Parslow T. G. (1995). RNA secondary structure and binding sites for gag gene products in the 5′ packaging signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 69, 2101–2109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clever J. L., Miranda D., Parslow T. G. (2002). RNA structure and packaging signals in the 5′ leader region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genome. J. Virol. 76, 12381–12387 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12381-12387.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clever J. L., Parslow T. G. (1997). Mutant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes with defects in RNA dimerization or encapsidation. J. Virol. 71, 3407–3414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damgaard C. K., Andersen E. S., Knudsen B., Gorodkin J., Kjems J. (2004). RNA interactions in the 5′ region of the HIV-1 genome. J. Mol. Biol. 336, 369–379 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damgaard C. K., Dyhr-Mikkelsen H., Kjems J. (1998). Mapping the RNA binding sites for human immunodeficiency virus type-1 gag and NC proteins within the complete HIV-1 and -2 untranslated leader regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 3667–3676 10.1093/nar/26.16.3667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlix J. L., Gabus C., Nugeyre M. T., Clavel F., Barré-Sinoussi F. (1990). Cis elements and trans-acting factors involved in the RNA dimerization of the human immunodeficiency virus HIV-1. J. Mol. Biol. 216, 689–699 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90392-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson L., Yu X. F. (1998). The role of nucleocapsid of HIV-1 in virus assembly. Virology 251, 141–157 10.1006/viro.1998.9374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Guzman R. N., Wu Z. R., Stalling C. C., Pappalardo L., Borer P. N., Summers M. F. (1998). Structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to the SL3 psi-RNA recognition element. Science 279, 384–388 10.1126/science.279.5349.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey A., York D., Smalls-Mantey A., Summers M. F. (2005). Composition and sequence-dependent binding of RNA to the nucleocapsid protein of Moloney murine leukemia virus. Biochemistry 44, 3735–3744 10.1021/bi047639q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirac A. M. G., Huthoff H., Kjems J., Berkhout B. (2002). Regulated HIV-2 RNA dimerization by means of alternative RNA conformations. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 2647–2655 10.1093/nar/gkf381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza V., Melamed J., Habib D., Pullen K., Wallace K., Summers M. F. (2001). Identification of a high affinity nucleocapsid protein binding element within the Moloney murine leukemia virus Psi-RNA packaging signal: implications for genome recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 314, 217–232 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza V., Summers M. F. (2004). Structural basis for packaging the dimeric genome of Moloney murine leukaemia virus. Nature 431, 586–590 10.1038/nature02944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza V., Summers M. F. (2005). How retroviruses select their genomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 643–655 10.1038/nrmicro1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. X., Copeland T. D., Henderson L. E., Gorelick R. J., Bosche W. J., Levin J. G., Rein A. (1996). HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein induces “maturation” of dimeric retroviral RNA in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 7577–7581 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J., Goff S. P. (1998). Mutational analysis of stem-loops in the RNA packaging signal of the Moloney murine leukemia virus. Virology 244, 133–145 10.1006/viro.1998.9090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherghe C., Leonard C. W., Gorelick R. J., Weeks K. M. (2010). Secondary structure of the mature ex virio Moloney murine leukemia virus genomic RNA dimerization domain. J. Virol. 84, 898–906 10.1128/JVI.01602-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherghe C., Weeks K. M. (2006). The SL1-SL2 (stem-loop) domain is the primary determinant for stability of the gamma retroviral genomic RNA dimer. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37952–37961 10.1074/jbc.M607380200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greatorex J. (2004). The retroviral RNA dimer linkage: different structures may reflect different roles. Retrovirology 1, 22. 10.1186/1742-4690-1-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin S. D., Allen J. F., Lever A. M. (2001). The major human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) packaging signal is present on all HIV-2 RNA species: cotranslational RNA encapsidation and limitation of Gag protein confer specificity. J. Virol. 75, 12058–12069 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12058-12069.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G. P., Lever A. M. (1992). The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging signal and major splice donor region have a conserved stable secondary structure. J. Virol. 66, 4144–4153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G. P., Miele G., Hunter E., Lever A. M. (1998). Functional analysis of the core human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging signal in a permissive cell line. J. Virol. 72, 5886–5896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Shioda T., Iwakura Y., Shibuta H. (1992). RNA packaging signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology 188, 590–599 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90513-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Ueno Y., Okamoto T. (1993). Elucidation of a conserved RNA stem-loop structure in the packaging signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. FEBS Lett. 327, 213–218 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80172-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helga-Maria C., Hammarskjöld M. L., Rekosh D. (1999). An intact TAR element and cytoplasmic localization are necessary for efficient packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA. J. Virol. 73, 4127–4135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L. E., Copeland T. D., Sowder R. C., Smythers G. W., Oroszlan S. (1981). Primary structure of the low molecular weight nucleic acid-binding proteins of murine leukemia viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 8400–8406 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert C. S., Mirro J., Rein A. (2004). mRNA molecules containing murine leukemia virus packaging signals are encapsidated as dimers. J. Virol. 78, 10927–10938 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10927-10938.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huseby D., Barklis R. L., Alfadhli A., Barklis E. (2005). Assembly of human immunodeficiency virus precursor gag proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17664–17670 10.1074/jbc.M412325200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huthoff H., Berkhout B. (2001). Two alternating structures of the HIV-1 leader RNA. RNA 7, 143–157 10.1017/S1355838201001881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell N. A., Mansky L. M. (2000). In the beginning: genome recognition, RNA encapsidation and the initiation of complex retrovirus assembly. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 1889–1899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye J. F., Lever A. M. (1999). Human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 differ in the predominant mechanism used for selection of genomic RNA for encapsidation. J. Virol. 73, 3023–3031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorchid A., Halwani R., Wainberg M. A., Kleiman L. (2002). Role of RNA in facilitating Gag/Gag-Pol interaction. J. Virol. 76, 4131–4137 10.1128/JVI.76.8.4131-4137.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. H., Tinoco I. (2000). A retroviral RNA kissing complex containing only two GC base pairs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9396–9401 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Lee K., O’Rear J. J. (1994). A short sequence upstream of the 5′ major splice site is important for encapsidation of HIV-1 genomic RNA. Virology 198, 336–340 10.1006/viro.1994.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodera Y., Sato K., Tsukahara T., Komatsu H., Maeda T., Kohno T. (1998). High-resolution solution NMR structure of the minimal active domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type-2 nucleocapsid protein. Biochemistry 37, 17704–17713 10.1021/bi981818o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konings D. A., Nash M. A., Maizel J. V., Arlinghaus R. B. (1992). Novel GACG-hairpin pair motif in the 5′ untranslated region of type C retroviruses related to murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 66, 632–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughrea M., Jetté L., Mak J., Kleiman L., Liang C., Wainberg M. A. (1997). Mutations in the kissing-loop hairpin of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reduce viral infectivity as well as genomic RNA packaging and dimerization. J. Virol. 71, 3397–3406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D. C., Stover C. C., Noznitsky J., Wu Z., Summers M. F. (2003). Structure of the intact stem and bulge of HIV-1 Psi-RNA stem-loop SL1. J. Mol. Biol. 326, 529–542 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01305-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever A., Gottlinger H., Haseltine W., Sodroski J. (1989). Identification of a sequence required for efficient packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA into virions. J. Virol. 63, 4085–4087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’Hernault A., Greatorex J. S., Crowther R. A., Lever A. M. L. (2007). Dimerisation of HIV-2 genomic RNA is linked to efficient RNA packaging, normal particle maturation and viral infectivity. Retrovirology 4, 90. 10.1186/1742-4690-4-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K., Heng X., Garyu L., Monti S., Garcia E. L., Kharytonchyk S., Dorjsuren B., Kulandaivel G., Jones S., Hiremath A., Divakaruni S. S., LaCotti C., Barton S., Tummillo D., Hosic A., Edme K., Albrecht S., Telesnitsky A., Summers M. F. (2011a). NMR detection of structures in the HIV-1 5 ′-leader RNA that regulate genome packaging. Science 334, 242–245 10.1126/science.1210460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K., Heng X., Summers M. F. (2011b). Structural determinants and mechanism of HIV-1 genome packaging. J. Mol. Biol. 410, 609–633 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luban J., Goff S. P. (1994). Mutational analysis of cis-acting packaging signals in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA. J. Virol. 68, 3784–3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann R., Baltimore D. (1985). Varying the position of a retrovirus packaging sequence results in the encapsidation of both unspliced and spliced RNAs. J. Virol. 54, 401–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann R., Mulligan R. C., Baltimore D. (1983). Construction of a retrovirus packaging mutant and its use to produce helper-free defective retrovirus. Cell 33, 153–159 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90344-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansky L. M., Krueger A. E., Temin H. M. (1995). The bovine leukemia virus encapsidation signal is discontinuous and extends into the 5′ end of the gag gene. J. Virol. 69, 3282–3289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T., Kodera Y., Miyauchi E., Tanaka H., Endoh H., Komatsu H., Tanaka T., Kohno T., Maeda T. (2007). Structural role of the secondary active domain of HIV-2 NCp8 in multi-functionality. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 358, 673–678 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T., Tanaka T., Endoh H., Sato K., Tanaka H., Miyauchi E., Kawashima Y., Nagai-Makabe M., Komatsu H., Kohno T., Maeda T., Kodera Y. (2009). The RNA recognition mechanism of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 2 NCp8 is different from that of HIV-1 NCp7. Biochemistry 48, 4314–4323 10.1021/bi802364b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride M. S., Panganiban A. T. (1996). The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encapsidation site is a multipartite RNA element composed of functional hairpin structures. J. Virol. 70, 2963–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride M. S., Panganiban A. T. (1997). Position dependence of functional hairpins important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA encapsidation in vivo. J. Virol. 71, 2050–2058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride M. S., Schwartz M. D., Panganiban A. T. (1997). Efficient encapsidation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vectors and further characterization of cis elements required for encapsidation. J. Virol. 71, 4544–5454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann E. M., Lever A. M. (1997). Location of cis-acting signals important for RNA encapsidation in the leader sequence of human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J. Virol. 71, 4133–41337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihailescu M. -R., Marino J. P. (2004). A proton-coupled dynamic conformational switch in the HIV-1 dimerization initiation site kissing complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 1189–1194 10.1073/pnas.0307966100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y., Garcia E. L., King S. R., Iyalla K., Loeliger K., Starck P., Syed S., Telesnitsky A., Summers M. F. (2010a). An RNA structural switch regulates diploid genome packaging by Moloney murine leukemia virus. J. Mol. Biol. 396, 141–152 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y., Irobalieva R. N., Tolbert B. S., Smalls-Mantey A., Iyalla K., Loeliger K., D’Souza V., Khant H., Schmid M. F., Garcia E. L., Telesnitsky A., Chiu W., Summers M. F. (2010b). Structure of a conserved retroviral RNA packaging element by NMR spectroscopy and cryo-electron tomography. J. Mol. Biol. 404, 751–772 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougel M., Barklis E. (1997). A role for two hairpin structures as a core RNA encapsidation signal in murine leukemia virus virions. J. Virol. 71, 8061–8065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougel M., Tounekti N., Darlix J. L., Paoletti J., Ehresmann B., Ehresmann C. (1993). Conformational analysis of the 5′ leader and the gag initiation site of Mo-MuLV RNA and allosteric transitions induced by dimerization. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 4677–4684 10.1093/nar/21.20.4677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougel M., Zhang Y., Barklis E. (1996). cis-active structural motifs involved in specific encapsidation of Moloney murine leukemia virus RNA. J. Virol. 70, 5043–5050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J. E., Goff S. P. (1989). Construction and analysis of deletion mutations in the U5 region of Moloney murine leukemia virus: effects on RNA packaging and reverse transcription. J. Virol. 63, 319–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa F., Lew K. A., Schmidt R. D., Browning M. T., Rizvi T. A. (2004). Mutational analysis of the predicted secondary RNA structure of the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus packaging signal. Virus Res. 99, 35–46 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson P. N., Carnegie P. R., Martin J., Davari Ejtehadi H., Hooley P., Roden D., Rowland-Jones S., Warren P., Astley J., Murray P. G. (2003). Demystified. Human endogenous retroviruses. Mol. Pathol. 56, 11–18 10.1136/mp.56.1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni N., Nikolaitchik O. A., Dilley K. A., Chen J., Galli A., Fu W., Prasad V. V. S. P., Ptak R. G., Pathak V. K., Hu W. S. (2011). Mechanisms of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 RNA packaging: efficient trans packaging and selection of RNA copackaging partners. J. Virol. 85, 7603–7612 10.1128/JVI.01774-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillart J. C., Dettenhofer M., Yu X. -F., Ehresmann C., Ehresmann B., Marquet R. (2004a). First snapshots of the HIV-1 RNA structure in infected cells and in virions. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48397–48403 10.1074/jbc.M408294200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillart J. C., Shehu-Xhilaga M., Marquet R., Mak J. (2004b). Dimerization of retroviral RNA genomes: an inseparable pair. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 461–472 10.1038/nrmicro903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillart J. C., Marquet R., Skripkin E., Ehresmann C., Ehresmann B. (1996). Dimerization of retroviral genomic RNAs: structural and functional implications. Biochimie 78, 639–653 10.1016/S0300-9084(96)80010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolin C., Dorfman T., Palú G., Göttlinger H., Sodroski J. (1994). Analysis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vectors of cis-acting sequences that affect gene transfer into human lymphocytes. J. Virol. 68, 3888–3895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznansky M., Lever A., Bergeron L., Haseltine W., Sodroski J. (1991). Gene transfer into human lymphocytes by a defective human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vector. J. Virol. 65, 532–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purzycka K. J., Pachulska-Wieczorek K., Adamiak R. W. (2011). The in vitro loose dimer structure and rearrangements of the HIV-2 leader RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 7234–7248 10.1093/nar/gkr385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rein A. (1994). Retroviral RNA packaging: a review. Arch. Virol. 9, 513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi T. A., Panganiban A. T. (1993). Simian immunodeficiency virus RNA is efficiently encapsidated by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J. Virol. 67, 2681–2688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R. S., Hu J., Laughrea M., Wainberg M. A., Liang C. (2002). Deficient dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA caused by mutations of the u5 RNA sequences. Virology 303, 152–163 10.1006/viro.2002.1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R. S., Liang C., Wainberg M. A. (2004). Is HIV-1 RNA dimerization a prerequisite for packaging? Yes, no, probably? Retrovirology 1, 23. 10.1186/1742-4690-1-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuragi J., Iwamoto A., Shioda T. (2002). Dissociation of genome dimerization from packaging functions and virion maturation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 76, 959–967 10.1128/JVI.76.3.959-967.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuragi J., Sakuragi S., Shioda T. (2007). Minimal region sufficient for genome dimerization in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion and its potential roles in the early stages of viral replication. J. Virol. 81, 7985–7992 10.1128/JVI.00429-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuragi J., Shioda T., Panganiban A. T. (2001). Duplication of the primary encapsidation and dimer linkage region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA results in the appearance of monomeric RNA in virions. J. Virol. 75, 2557–2565 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2557-2565.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuragi J., Ueda S., Iwamoto A., Shioda T. (2003). Possible role of dimerization in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genome RNA packaging. J. Virol. 77, 4060–4069 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4060-4069.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandefur S., Smith R. M., Varthakavi V., Spearman P. (2000). Mapping and characterization of the N-terminal I domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Pr55(Gag). J. Virol. 74, 7238–7249 10.1128/JVI.74.16.7238-7249.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skripkin E., Paillart J. C., Marquet R., Ehresmann B., Ehresmann C. (1994). Identification of the primary site of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA dimerization in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 4945–4949 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs S., Garyu L., Connor R., Summers M. F. (2008). Potential intra- and intermolecular interactions involving the unique-5′ region of the HIV-1 5′-UTR. Biochemistry 47, 13064–13073 10.1021/bi8014373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers M. F., Henderson L. E., Chance M. R., Bess J. W., South T. L., Blake P. R., Sagi I., Perez-Alvarado G., Sowder R. C., Hare D. R. (1992). Nucleocapsid zinc fingers detected in retroviruses: EXAFS studies of intact viruses and the solution-state structure of the nucleocapsid protein from HIV-1. Protein Sci. 1, 563–574 10.1002/pro.5560010502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers M. F., South T. L., Kim B., Hare D. R. (1990). High-resolution structure of an HIV zinc fingerlike domain via a new NMR-based distance geometry approach. Biochemistry 29, 329–340 10.1021/bi00454a005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tounekti N., Mougel M., Roy C., Marquet R., Darlix J. L., Paoletti J., Ehresmann B., Ehresmann C. (1992). Effect of dimerization on the conformation of the encapsidation Psi domain of Moloney murine leukemia virus RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 223, 205–220 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90726-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara T., Komatsu H., Kubo M., Obata F., Tozawa H. (1996). Binding properties of human immunodeficiency virus type-2 (HIV-2) RNA corresponding to the packaging signal to its nucleocapsid protein. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 40, 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Temin H. M. (1982). Encapsidation sequences for spleen necrosis virus, an avian retrovirus, are between the 5′ long terminal repeat and the start of the gag gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 5986–5990 10.1073/pnas.79.19.5986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts J. M., Dang K. K., Gorelick R. J., Leonard C. W., Bess J. W., Swanstrom R., Burch C. L., Weeks K. M. (2009). Architecture and secondary structure of an entire HIV-1 RNA genome. Nature 460, 711–716 10.1038/nature08237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson K. A., Gorelick R. J., Vasa S. M., Guex N., Rein A., Mathews D. H., Giddings M. C., Weeks K. M. (2008). High-throughput SHAPE analysis reveals structures in HIV-1 genomic RNA strongly conserved across distinct biological states. PLoS Biol. 6, e96. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S. S., Kim J. M., Kim S. (2000). The 17 nucleotides downstream from the env gene stop codon are important for murine leukemia virus packaging. J. Virol. 74, 8775–8780 10.1128/JVI.74.13.5825-5835.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]