Abstract

Severe vitamin E deficiency results in lethal myopathy in animal models. Membrane repair is an important myocyte response to plasma membrane disruption injury as when repair fails, myocytes die and muscular dystrophy ensues. Here we show that supplementation of cultured cells with α-tocopherol, the most common form of vitamin E, promotes plasma membrane repair. Conversely, in the absence of α-tocopherol supplementation, exposure of cultured cells to an oxidant challenge strikingly inhibits repair. Comparative measurements reveal that, to promote repair, an anti-oxidant must associate with membranes, as α-tocopherol does, or be capable of α-tocopherol regeneration. Finally, we show that myocytes in intact muscle cannot repair membranes when exposed to an oxidant challenge, but show enhanced repair when supplemented with vitamin E. Our work suggests a novel biological function for vitamin E in promoting myocyte plasma membrane repair. We propose that this function is essential for maintenance of skeletal muscle homeostasis.

Membrane repair of myocytes is important to prevent such disease as muscular dystrophy but the properties of this repair are not well characterised. In this study, vitamin E is shown to be important in the repair of myocyte cell membranes in cultured cells and in intact muscle.

Membrane repair of myocytes is important to prevent such disease as muscular dystrophy but the properties of this repair are not well characterised. In this study, vitamin E is shown to be important in the repair of myocyte cell membranes in cultured cells and in intact muscle.

Physical disruption of plasma membrane integrity, for example, tearing of the cell boundary, is a common, but not necessarily lethal, cell injury in vivo1. Cells that suffer disruption injury under physiological conditions include cardiomyocytes2, skeletal muscle myocytes3, gastrointestinal tract epithelial cells4, epidermal cells of the skin5 and endothelial cells of large arteries6. The causative agent is hypothesized to be physiologically generated mechanical stress7. Disruption events are especially prominent in skeletal muscle, reaching the highest measured levels during exercise-induced eccentric (high force generating) contractions3. Successful repair permits cell survival, whereas failure rapidly results in cell death via necrosis8.

Disease involving skeletal muscle is thought to be an important pathological consequence of repair failure. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2B, for example, is characterized by progressive weakness and wasting of the pelvic and shoulder girdle muscles9. The responsible mutation is in the gene coding for dysferlin. Dysferlin, in normal mouse muscle, localizes to disruption repair sites in response to membrane injuries10. In dysferlin null mice, myocyte membrane repair fails10. More recently, diabetic myopathy has also been linked to a membrane repair defect11.

Considerable evidence, dating from early studies, shows that muscle health is dependent on an adequate supply of dietary vitamin E. Diets severely deficient in α-tocopherol result in profuse myocyte necrosis and an ultimately lethal muscular dystrophy in various animal models including rats12,13,14,15 guinea pigs16,17, rabbits18 and ducklings19,20. Vitamin E deficient mice and rats are more prone to muscle damage after contractile activity21. The human diet, in its various forms, is rich in vitamin E. Thus, vitamin E deficiency in humans, measured as decreased levels in blood, is primarily a secondary event caused by diseases that prevent absorption: it is rarely if ever as severe as the diet-induced deprivation that can be imposed on laboratory animals. However, vitamin E deficiency secondary to disease in humans is associated with muscle weakness, elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels and myopathy22,23,24, and low blood levels of vitamin E are associated with a loss of muscle strength in the elderly25. Why vitamin E, at the cellular and molecular level, is crucial to muscle health has remained an unanswered question.

Despite uncertainty about how exactly vitamin E promotes muscle health, two general mechanisms by which it could interact with cells/molecules in vivo have been investigated. The first is as a membrane 'stabilizer'. Due to its lipid solubility, vitamin E partitions into the hydrophobic core of the plasma membrane bilayer, with resultant changes in bilayer physical properties, such as fluidity, which increased at the bilayer surface of liposomes and decreased in the interior26. Moreover, the chromanol-head group of vitamin E binds to the head group of phospholipids, limiting their mobility within the membrane26. The major biological evidence for a 'stabilizing' role is that erythrocyte lysis, induced by oxidative stress27,28,29 and other stressors30,31,32 is prevented by vitamin E supplementation and exacerbated by vitamin E depletion. Moreover, haemolytic anaemia has been reported in human vitamin E deficiency33.

The second generalized mechanism of action proposed for vitamin E is as a potent antioxidant. Vitamin E's chromanol-head group, located within the hydrophilic portion of the bilayer, scavenges active oxygen radicals and singlet oxygen and thereby potently prevents potentially harmful phospholipid oxidation events34,35. Importantly, in the context of this work, skeletal muscle accumulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) during strenuous exercise. Consequent lipid peroxidation is demonstrable as, for example, increases in malondialdehyde and F(2α)-isoprostanes36,37. It has therefore been proposed that exercised skeletal might benefit from antioxidant activity38. Not surprisingly, accumulation of ROS in exercised skeletal muscle is significantly decreased by vitamin E supplementation39.

Why vitamin E, at the cellular and molecular level, is crucial to muscle health has remained an unanswered question. Here we test the hypothesis that vitamin E, acting as a membrane associated antioxidant, promotes membrane repair by skeletal muscle myocytes. Several key predictions of this hypothesis are tested: first, that introduction of exogenous vitamin E into cell membranes will promote repair; second, that other antioxidants introduced exogenously will promote membrane repair but only if capable of associating with the membrane or regenerating endogenous vitamin E antioxidant capacity; third, that imposition of an oxidant challenge will inhibit repair; fourth, that vitamin E will prevent this oxidant-induced inhibition; and fifth, that myocytes in intact muscle will similarly display an oxidation-sensitive phenotype that vitamin E supplementation can eliminate. The results of these tests strongly confirm that vitamin E promotes plasma membrane repair, as a membrane-based anti-oxidant, and provide a working hypothesis for explaining how vitamin E is crucial to muscle homeostasis.

Results

Promotion of cultured cell repair in vitro

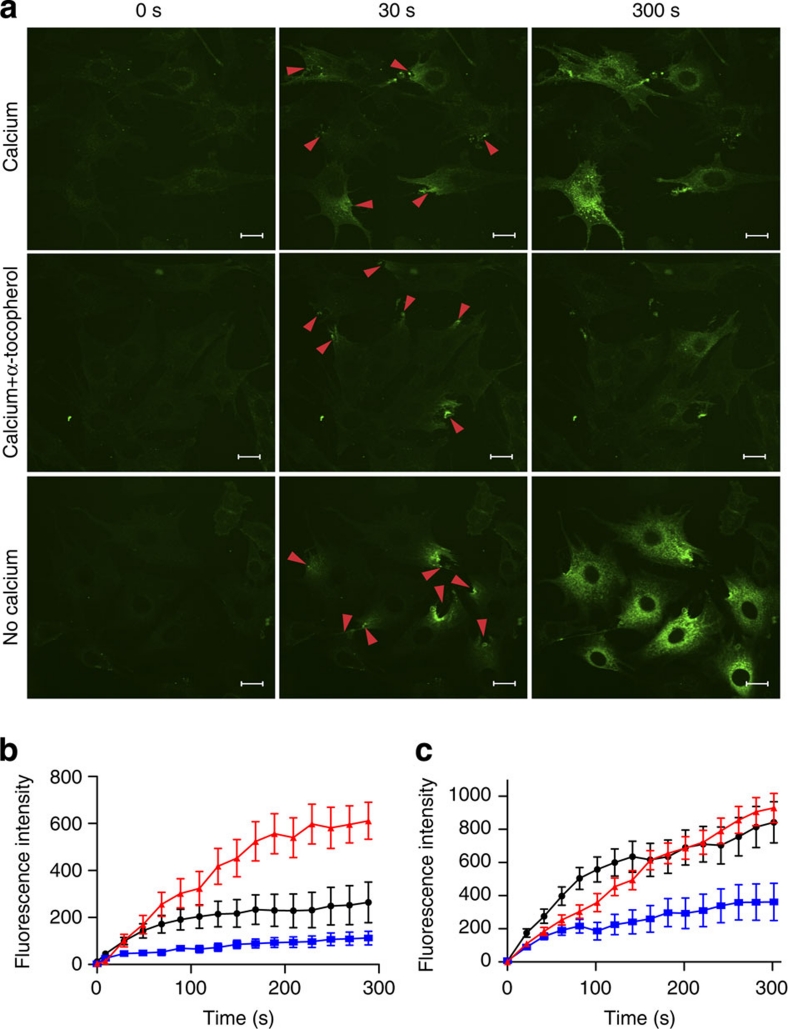

C2C12 myoblasts were incubated overnight in a medium containing α-tocopherol and serum, whose protein constituents are required for delivery of this water insoluble compound to cells40. 'Loaded' cells were washed to remove unincorporated vitamin, and repair was monitored using a laser-based assay as previously described41. Briefly, entry of FM 1-43 dye into cell cytoplasm through a laser-induced disruption, and consequent staining of intracellular membrane, is observed and quantified over time in the living, wounded cell. When repair fails, as it does in the absence of the addition of Ca2+ to saline, global staining of internal membrane compartments develops (Fig. 1a). In the presence of repair-permissive Ca2+ (1.5 mM), membrane repair is activated42, and only a minority of repair competent C2C12 cells filled with dye after injury (Fig. 1a). When C2C12 cells were loaded with α-tocopherol before injury, less dye entry was observed than in untreated controls (Fig. 1a). Quantification confirmed that α-tocopherol-treated C2C12 cells accumulate, on average, significantly less dye after injury than untreated cells (Fig. 1b). However initial dye uptake for all conditions, 10 and 20 s after injury, is comparable: thus the size of the disruption is not affected by α-tocopherol (Fig. 1b). Hence, vitamin E loading enhances membrane repair, and does not provide protection from damage.

Figure 1. Vitamin E promotes membrane repair in vitro.

(a) C2C12 cells were cultured for 18 h in a medium with or without 200 μM α-tocopherol, washed free of exogenous vitamin and immediately subjected to laser wounding in the presence or absence of calcium (added at 1.2 mM to PBS). Micrographs were taken before injury in FM 1-43 dye (time=0 s; the red arrowheads mark laser disruption sites) and imaged at 30 and 300 s after injury. (b) Quantitation of FM 1-43 dye influx over time after laser injury. C2C12 cells loaded with α-tocopherol (blue squares) before wounding displayed a significant (P<0.01; n=16) reduction in dye uptake after injury compared with non-treated controls (black dots); data for cells injured in the absence of added calcium is also presented (red triangles). (c) HeLa cells were loaded with 200 μM α-tocopherol for 24 h before laser analysis. Cells treated with α-tocopherol (blue squares) displayed a significant (P<0.001; n=15) reduction in dye uptake compared with control, untreated cells (black dots); data is also shown for cells treated with α-tocopherol and injured in the absence of added calcium (red triangles). Data are presented as the mean±s.e.m. Scale bars 20 μm.

We next asked if repair could be promoted in the HeLa cell, which, for unknown reasons, is not repair competent in the laser assay: it routinely fails to repair under the laser conditions employed above for the C2C12 cell. HeLa cells treated with α-tocopherol and injured in the presence of Ca2+ took up significantly less dye than did control untreated cells (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Movies 1 and 2). Importantly, in the absence of Ca2+, the kinetics of dye uptake were unaffected by vitamin treatment (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Movie 3). Thus, again, vitamin E does not protect cells from injury; rather, it facilitates Ca2+-dependent membrane repair in an otherwise repair incompetent cell.

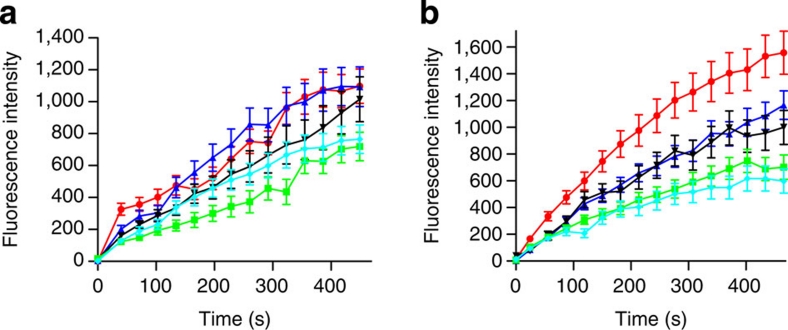

α-tocopherol is present in human blood plasma (solublized there by binding to serum proteins) at a concentration of 20–30 μM43. Previous work showed that cells loaded by a protocol similar to ours, for example incubation in medium containing 25 μM α-tocopherol and serum for 18 h, accumulated ~1.5 μmol of α-tocopherol per μmol of cell cholesterol, and that a 48 h loading incubation increased this value by ~3-fold40. We utilized HeLa cells, which became repair competent upon α-tocopherol loading, to evaluate dosage requirements in the range 2.5–2,500 μM, employed in either a 24 or 48 h pretreatment ('loading'). After 24 h of loading, only the highest concentrations (250 and 2500 μM) were effective at promoting repair (Fig. 2a), but after 48 h all concentrations tested had a significant effect (Fig. 2b). Thus, not only dosage but, as expected based on its requirement for solubilization by carrier proteins, the duration of exposure to α-tocopherol is crucial.

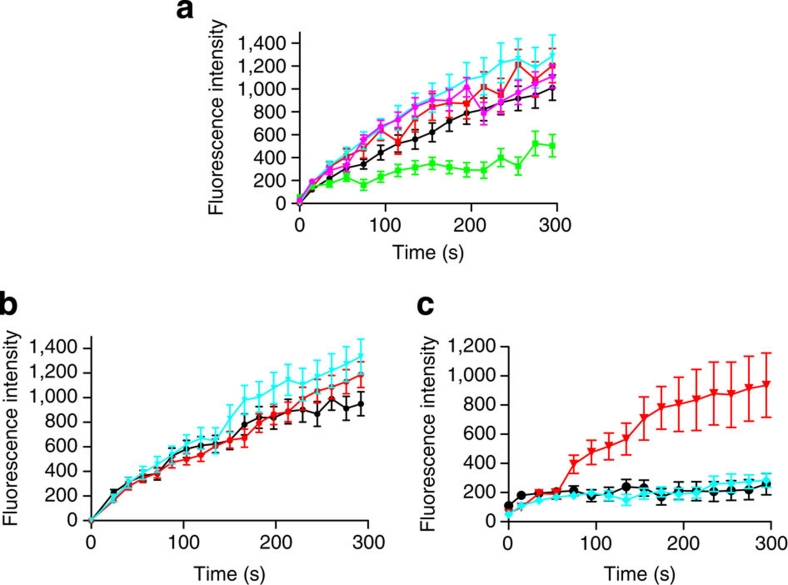

Figure 2. Vitamin E loading interval and dosage.

(a) HeLa cells were loaded for 24 h with 2.5 (blue triangles), 25 (black triangles), 250 (green squares) and 2500 (cyan diamonds) μM α-tocopherol. No significant change in dye uptake compared with untreated controls (red dots) was found in cells treated with the lower concentrations of α-tocopherol. Only cells treated with 250 or 2500 μM α-tocopherol displayed a significant (P<0.001; n=21) decrease in dye uptake. (b) HeLa cells were loaded 48 h in the same concentrations as above. All samples treated with α-tocopherol (same colour scheme as 'b') displayed a significant (P<0.001; n=18) decrease in dye uptake relative to untreated controls (red dots). Data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.

Reversal of a diabetes model repair defect

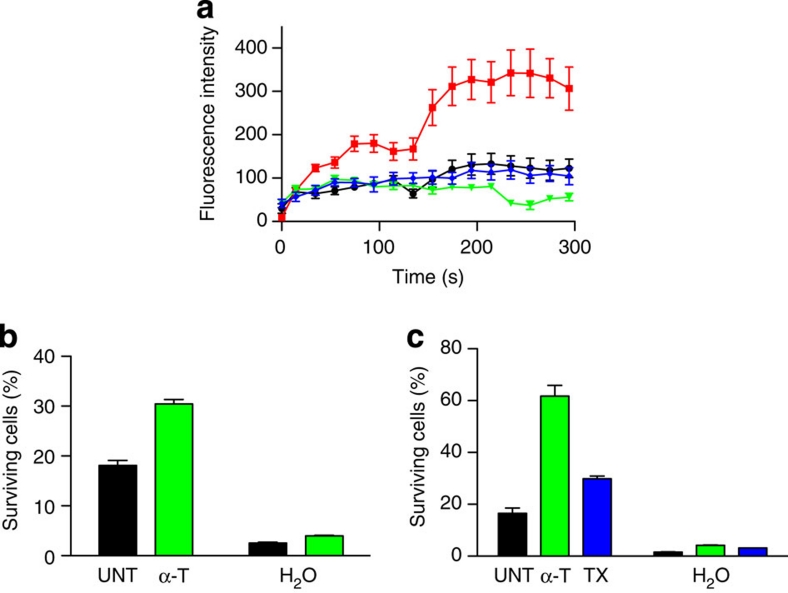

To determine whether vitamin E treatment could reverse a repair defect exhibited in an in vitro cell model of diabetes11, we loaded repair-deficient cells, cultured in elevated glucose for 14 weeks, with α-tocopherol. Following laser injury, cells loaded with α-tocopherol displayed significantly less dye uptake than untreated controls, indicating a partial restoration of repair capacity (Fig. 3a). Thus, a pathologically generated repair defect can be partially eliminated by vitamin treatment in vitro.

Figure 3. Vitamin E reverses a high glucose-induced repair defect and enhances survival of mechanically injured cells.

(a) BS-C-1 cells were cultured in 30 mM glucose (red squares) for 14 weeks, a treatment previously shown to produce deficient membrane repair. Mannitol (30 mM) serves as an iso-osmolar control (black dots). Glucose-treated cells were loaded with 200 μM α-tocopherol (green triangles) or 200 μM Trolox (blue diamonds) for 24 h. Laser assay demonstrates a significant decrease (P<0.001; n=14) in dye uptake in the α-tocopherol (green triangles) and Trolox- (blue diamonds) treated cells compared with the untreated controls (red squares). (b) C2C12 myoblasts in a 96-well plate were loaded with 200 μM α-tocopherol (α-T; green bars) or left untreated (UNT; black bars) for 24 h. A live/dead assay was performed after mechanically scraping the cells off the plate in the presence of PBS containing Ca2+. Survival was calculated by reference to a non-wounded (not scraped) population of cells. Scraping of cells that were first osmotically shocked by immersion in distilled water provides a positive reference for cell death (H2O). A significant (P<0.0001; n=4) increase in survival was observed in the α-tocopherol-treated cells relative to untreated controls. (c) The same procedure, as in b, was followed for HeLa cells, and, in addition, a population of cells was treated with 200 μM water-soluble vitamin E (TX; blue bars). A significant (P<0.001; n=4) increase in survival was observed in the α-tocopherol and Trolox-treated cells relative to untreated controls. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.

Promotion of repair in mechanically injured cells

In vivo, physiologically occurring membrane disruption injuries arise from mechanical forces. To test if repair of mechanical injuries is also promoted by vitamin E, we scraped cells from their culture substratum, mechanically disrupting the majority of cell plasma membranes in the population44. Cell survival, dependent on successful repair, was then monitored. Both C2C12 (Fig. 3b) and HeLa cells (Fig. 3c), which were loaded with α-tocopherol had significantly higher survival rates following scrape-injury than untreated controls. Thus, vitamin E was capable of not only facilitating membrane repair in cells via a laser-induced injury but also promoted long-term survival after mechanically induced disruption.

Anti-oxidant requirement for repair promotion

To test which aspect of α-tocopherol structure is required for repair promotion, we employed a biologically active analogue, Trolox, which possesses the same chromanol-head group (with antioxidant activity) as α-tocopherol but lacks the hydrophobic tail. Trolox is therefore more water soluble than α-tocopherol. However, though it does not intercalate into the hydrophobic domains of lipid bilayers, Trolox does associate with the plasma membrane, perhaps via electrostatic interaction with phospholipid-head groups and where it acts as a potent lipid-targeted antioxidant45. Trolox significantly reversed the membrane repair defect caused by elevated glucose treatment (Fig. 3a). Trolox also significantly increased cell survival after scraping (Fig. 3c). Thus, both lipid and water-soluble vitamin E promote membrane repair, suggesting that the antioxidant function is essential.

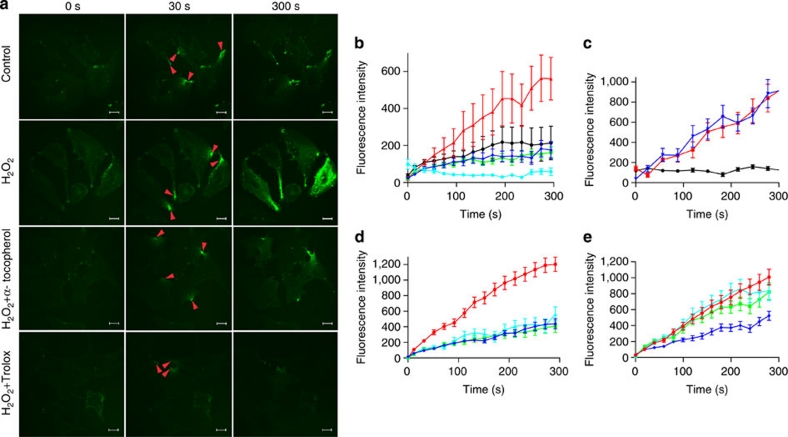

If antioxidant activity is essential for repair promotion, it is further predicted that repair will be inhibited by an oxidant challenge. To test this prediction, we laser injured cells in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). H2O2 treatment alone, in the absence of laser injury, was not sufficient to induce dye uptake, indicating that oxidant challenge by itself did not induce cell 'leakiness'. However, repair after laser injury was strikingly inhibited by H2O2 (Fig. 4a,b). In contrast, repair was unaffected in the presence of H2O2 if cells were pre-loaded with α-tocopherol or Trolox (Fig. 4a,b), for example, dye uptake was indistinguishable from cells injured in buffer-lacking H2O2. The thiol oxidant, thimerosal, similarly inhibited repair (Fig. 4c). Thus, oxidative stress impairs membrane repair, but α-tocopherol loading can prevent this failure from developing. This confirms that it is the antioxidant function of this vitamin that exertions the repair-promoting effect.

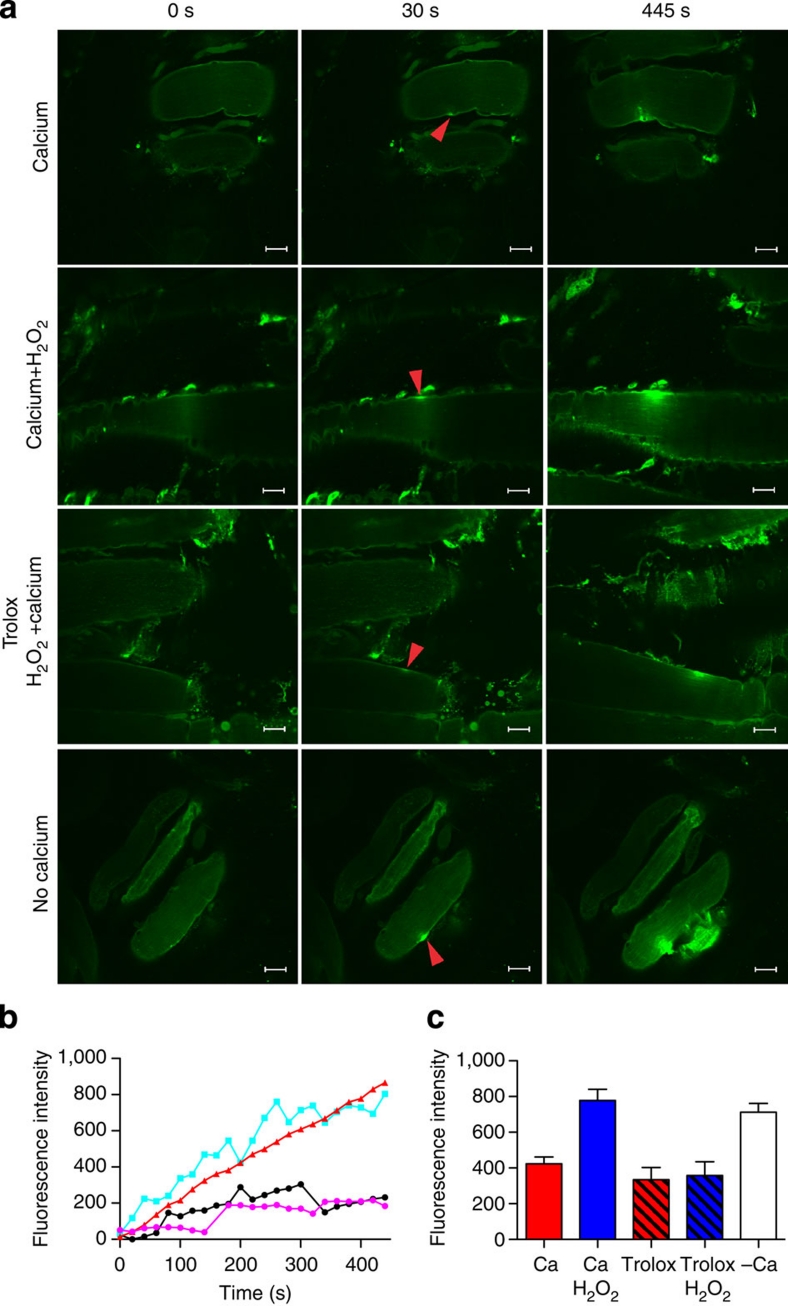

Figure 4. Vitamin E prevents oxidative stress-induced repair failure.

(a) BS-C-1 cells were loaded for 24 h with 200 μM α-tocopherol or Trolox. Cells were laser wounded in PBS-containing calcium, in the presence or absence of 1 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Images of cells were captured before (0 s) and after injury (30 s and 300 s), red arrows indicate injury sites. (b) BS-C-1 cells not wounded but exposed to H2O2 (cyan dots), displayed nominal dye uptake in the laser assay. Cells wounded in the presence of H2O2 (red triangles) showed significantly (P<0.01; n=12) more dye influx than wounded cells not exposed to this oxidant challenge (black dots). Cell treatment with α-tocopherol (green squares) or Trolox (blue diamonds) significantly (P<0.01; n=17) decreased dye entry into oxidant-challenged cells. (c) BS-C-1 cells were laser wounded in the presence of 5 mM thimerosal (blue triangles). This oxidant significantly (P<0.01; n=12) increased dye uptake relative to untreated controls (black dots), to approximately the same level as cells injured in the absence of Ca2+ (red squares). (d) HeLa cells were pretreated 24 h with 200 μM α-tocopherol (green squares) or Trolox (blue diamonds), or 1 mM vitamin C (cyan triangles). Cells pretreated with antioxidants had significantly (P<0.05; n=17) less dye influx after laser injury than control, untreated cells (red dots). (e) HeLa cells were assessed for membrane repair immediately (less than 15 min) after addition of α-tocopherol (green squares), Trolox (blue diamonds), or vitamin C (cyan triangles) to the wounding solution. Only cells injured in Trolox displayed a significant (P<0.001; n=17) decrease in dye influx compared with untreated cells. Scale bars 20 μm.

Membrane association requirement for repair promotion

To determine if antioxidant capacity by itself is sufficient to promote repair, we tested a variety of other antioxidants, namely vitamin C, dithiothreitol (DTT) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP), none of which bind to biological membranes. Overnight incubation of vitamin C was found to enhance repair (Fig. 4d). DTT was toxic to cells in an overnight incubation (see below for short-term incubation). HRP in an overnight incubation failed to enhance repair (Fig. 5a). This data suggested that an antioxidant capacity by itself is not sufficient.

Figure 5. Effect of antioxidants incapable of membrane association.

(a) HeLa cells were incubated for 24 h with 200 μM HRP (cyan triangles) or 200 μM α-tocopherol (green squares) or left untreated (black dots). Cells were washed free of exogenous antioxidants and laser wounded in the presence of calcium. One population of untreated cells was injured in PBS-containing HRP (magenta dots) or injured in the absence of calcium (red dots). Only cells that were loaded before wounding with α-tocopherol displayed a significant (P<0.05; n=17) decrease in dye uptake. (b) HeLa cells were injured in the presence or absence of 10 mM DTT (cyan triangles). Cells injured in the presence of DTT did not display a significant difference in dye uptake kinetics when compared with controls injured plus (black dots) or minus (red triangles) calcium. (c) BS-C-1 cells were injured in the presence of 10 mM DTT (cyan diamonds). Cells injured in the presence of DTT displayed no significant difference in dye uptake kinetics when compared with control untreated cells (black dots). The data representing wounding in the absence of Ca2+ is also shown (red triangles). Data are presented as the mean±s.e.m.

To test if membrane association of the antioxidant is a requisite property for repair promotion, we measured repair immediately after addition of various antioxidants to the wounding saline. We, reasoned that of the antioxidants only Trolox, which can rapidly associate with bilayers46, would be effective in this short-term exposure. In fact, neither α-Tocopherol, vitamin C (Fig. 4e), HRP (Fig. 5a) nor DTT (Fig. 5b,c) enhanced repair assayed immediately (5–15 min) after the addition of these agents. As expected, only Trolox significantly enhanced repair in this short-term incubation (Fig. 4e). Thus, based on several lines of experimentation, we conclude that membrane association of a phospholipid-based antioxidant is essential for repair promotion, or else the anti-oxidant must, as in the case of vitamin C, be capable of regenerating endogenous vitamin E.

Repair promotion in intact skeletal muscle

All experiments described to this point have utilized in vitro models. To determine whether membrane repair is similarly impacted in intact skeletal muscle by an oxidant challenge, and, if so, whether vitamin E can promote repair in the face of such challenge, we assessed the membrane repair response in freshly excised mouse solei. As with cultured cells, myocytes in intact muscle injured in the presence of H2O2 failed to restrict dye influx through the injury site, resembling cells that failed to repair due to the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Figure 6a and Supplementary Movie 4). By contrast, H2O2-challenged myocytes in muscles treated with Trolox for 1 h before laser injury did not fill rapidly with dye: staining predominantly consisted of a hot spot at the injury site (Figure 6a and Supplementary Movie 5). Quantitation confirmed that muscle myocytes injured in the presence of H2O2 failed to repair but that, in contrast, repair by muscle myocytes pretreated with Trolox and injured in H2O2 was indistinguishable from myocytes not exposed to H2O2 (Fig. 6b,c). Thus, an oxidant challenge compromises myocyte repair in situ, and this failure is preventable by the vitamin E analogue, Trolox.

Figure 6. Vitamin E promotes membrane repair in intact skeletal muscle.

(a) Soleus muscle was excised and then with minimal delay laser injured (red arrow indicates the site of injury) in the presence of 5 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Wounding plus (calcium) and minus (no calcium) in the absence of H2O2 is also shown. One group of solei was treated with Trolox for 1 h before laser injury (Trolox). The confocal images depict myocyte staining before (0 s) and at two intervals (30 s and 445 s) after injury with FM 1-43 dye. (b) Measured FM dye influx (20 s intervals) for the four myocytes imaged above, injured in the absence of extracellular calcium (red triangles), in the presence of H2O2 (cyan squares), in the absence of H2O2 (black dots) and in the presence of H2O2 after Trolox pretreatment (magenta dots). Dips and rises in the fluorescence are observed due to muscle contractions that caused temporary lapses in focus. (c) Total dye uptake by myocytes in intact solei 445 s after laser injury under the conditions defined above. A significant (P<0.05; n=8) increase in dye uptake occurred in fibres exposed to H2O2 (blue bar) relative to unchallenged controls (red bar). Trolox pretreatment of H2O2 challenged cells (blue bar with diagonal stripes) significantly (P<0.05; n=10) decreased dye uptake compared with untreated H2O2 challenged cells (blue bar). Scale bars 20 μm.

Discussion

We here provide direct, functional evidence that one biological role of vitamin E is to promote plasma membrane repair. Thus, in cultured cell models, we tested whether provision of additional vitamin E promotes repair: we found enhancement of repair in myoblasts that, under normal culture conditions, display repair without this supplement; acquisition of repair in HeLa cells that normally do not repair; and amelioration of a high glucose-induced repair defect.

We also, using cultured cell models, explored what attributes of vitamin E were required for repair promotion. Clearly, the antioxidant capacity of vitamin E is crucial as two additional antioxidants, namely Trolox and vitamin C, could duplicate α-tocopherol's repair promoting capacity in vitro. Furthermore, imposed oxidative stress strongly inhibited repair, and both anti-oxidant analogues of vitamin E could prevent failed repair in the face of this oxidative challenge.

How might vitamin E promote membrane repair? Membrane phospholipids are a prominent target of oxidants, and vitamin E efficiently prevents lipid peroxidation. Membrane repair involves Ca2+-activated membrane fusion events42,47. Vitamin E may therefore promote repair by preventing the formation of oxidized phospholipids that theoretically might interfere with the membrane fusion events. However, to our knowledge, no studies on any membrane fusion model system, have directly demonstrated this inhibitory mechanism. We also show that the thiol oxidant, thimerosal, inhibited repair. Thus, protection of the protein machinery mediating repair from oxidative damage may also be important. In fact, thiol-reducing agents, such as DTT, are common additives to systems that reconstitute bilayer fusion events in vitro48. However, we found DTT was without effect on repair in living cells suggesting that in the absence of an imposed and perhaps extreme oxidative challenge, such as thimerosal creates, protein oxidation events are not consequential.

Another, and not mutually exclusive, explanation for how vitamin E promotes repair is suggested by the two following observations. First, that compounds that induce negative curvature in bilayers promote Ca2+-triggered fusion events49. Second, that α-tocopherol can induce negative spontaneous curvature in membranes50. Thus vitamin E may directly enhance membrane repair by virtue of the biophysical alterations it induces in membranes. This might explain why α-tocopherol was often found to be more potent than Trolox in promoting repair.

What our present studies do suggest is that, for repair promotion, the antioxidant must be capable of associating with biological membranes. Although α-tocopherol clearly partitions into the hydrophobic domain of phospholipid bilayers, the behaviour of Trolox is less clear in this regard: 'partitioning' into bilayers by Trolox has been observed46, as has an aqueous phase interaction with the phospholipid-head groups45. Hence, we use throughout the 'term' associate as a descriptor for Trolox's interaction with membranes. In any case, we found that, with the exception of vitamin C, only α-tocopherol and Trolox among the antioxidants tested, both of which associate with membranes, promoted repair. Moreover, only Trolox, which can rapidly associate with membranes, promoted repair after a brief (<15 min) incubation: α-tocopherol, which must be carried by serum proteins with hydrophobic domains to its membrane destinations was ineffective in short-term pre-incubations.

How then does vitamin C, an antioxidant that does not associate with membranes, promote repair? The simplest explanation is that it does so by regenerating an antioxidant already located in cell membranes, namely, vitamin E51. Consistent with this possibility, repair promotion by vitamin C required a prolonged (24 h) pre-incubation period.

A large number of observations (not all of which are listed here) point to skeletal muscle as one tissue in which vitamin E has a crucial role in homeostasis: all of these are moreover consistent with promotion of membrane repair as the key role being played by this vitamin. We mention above the pioneering studies that identified lethal skeletal muscle pathology following severe, pro-longed deprivation in some species. More recently, it has been found that treadmill exercise dramatically increases muscle damage in vitamin E-deprived rats: serum CK levels and muscle pathology were both dramatically elevated compared with rats fed a normal diet52. Also, as motioned above, in humans one of the problems associated with vitamin E deficiency is skeletal myopathy, and low vitamin E levels in the elderly are correlated with 'frailty' syndrome, characterized primarily by loss of muscle strength. More importantly, vitamin E supplementation protects human muscle from injury by eccentric exercise36,53, a form of muscle contraction known to result in extensive membrane disruption events. Statins, cholesterol-lowering drugs whose main side effect is muscle damage, reduce vitamin E levels in blood, leading to the speculation that this deficiency might explain statin-induced muscle damage54. We also mention above that muscular dystrophy can result from a failure in plasma membrane repair by skeletal muscle myocytes and that plasma membrane disruptions occur not only in disease, such as muscular dystrophy, but also physiologically, in normal muscle, reaching the highest measured levels during exercise-induced eccentric contractions. These eccentric contractions generate high levels of ROS relative to concentric contractions55, and vitamin E supplementation can reduce exercise-induced oxidative damage of phospholipids38. In one case where a positive effect of supplementation was demonstrable in a muscle contraction model, careful analysis showed that the additional vitamin E did not prevent development of a post-contraction force deficit, or reduce the number of injured fibres, but that it did prevent subsequent rises in blood CK levels56, as would be consistent with an action that was reparative, not protective.

However, although supplementation has been shown to reduce exercise-related muscle damage in some protocols, notably those involving eccentric contractions, it has failed to provide any benefit in many others, or for Duchene muscular dystrophy patients39. Thus, it is possible that normal (human and rodent) levels of vitamin E are more than sufficient to promote the repair events elicited by some forms of exercise and disease, or that vitamin E is incapable of promoting repair of these types of disruption.

Most importantly, in evaluating the biological role in vivo of vitamin E, we here directly test whether vitamin E can promote membrane repair in skeletal muscle. Using intact mouse skeletal muscle, we show that oxidative stress severely impairs myocyte membrane repair, and that this impairment is prevented if the muscle is first exposed to Trolox, a water-soluble analogue of vitamin E that rapidly associates with cell membranes.

We have also shown recently that, in diabetic mice, which exhibit myopathy, skeletal muscle cell plasma membrane repair is defective11. ROS are known from many studies to be elevated in diabetic mice, where vitamin E supplementation is demonstrated to decrease this oxidative stress and increase skeletal muscle anabolic synthetic events57. Here we show, in vitro, that vitamin E can reverse the repair defect induced by cell exposure to high glucose. Thus, diabetes may be a disease in which increased ROS generation leads to myopathy via failed membrane repair. Another such disease might be amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), in particular the form arising from superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) deficiency. SOD1 KO mice exhibit ALS symptoms, including myopathy, which is the earliest detectable symptom by magnetic resonance imaging58. Moreover, myopathy is clearly evident even when the SOD1 KO is confined to skeletal muscle cells, for example when the myopathy cannot be explained as an underlying neurological deficit59. As SOD1 is a potent superoxide scavenger, it is conceivable that the myopathy resulting from its absence, is due to the consequent increase in oxidative stress, which we show here potently impairs membrane repair. Interestingly in this context, consumption of high levels of vitamin E correlated inversely with the incidence of ALS in a human population60. Thus, promotion of membrane repair by vitamin E may be important in these human diseases.

We conclude by presenting our working hypothesis for explaining how vitamin E is essential to skeletal muscle homeostasis (Fig. 7). Diets lacking in vitamin E deprive muscle myocyte membranes of a constituent that, we show here, promotes repair as a membrane-based antioxidant. Muscle contraction both generates ROS and causes plasma membrane disruptions. Myocytes in vitamin E-deprived muscle, but not normal muscle, fail to repair these disruptions. Loss of muscle, characteristic of advanced vitamin E deficiency, ultimately occurs as continuing myocyte death overwhelms regenerative capacity.

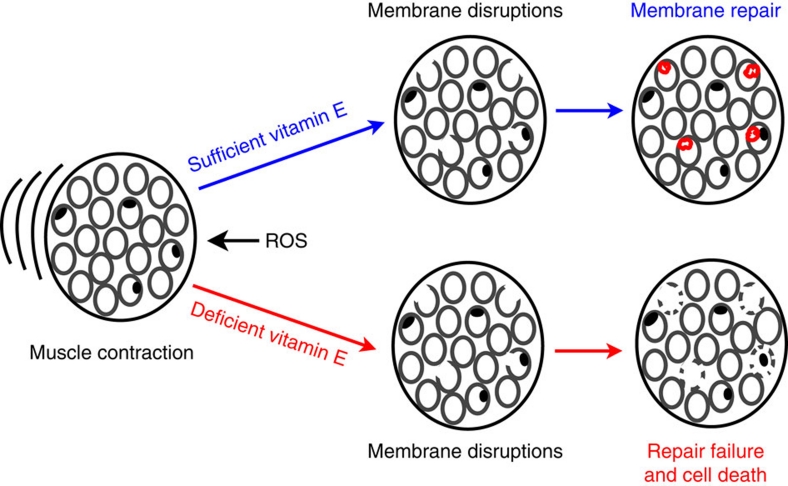

Figure 7. A hypothesis for explaining how vitamin E promotes muscle homeostasis.

Muscle contractions, especially high-force eccentric contractions, disrupt the plasma membranes (grey ovals) of myocytes and generate ROS. If sufficient vitamin E is present in the membranes of these injured myocytes, repair succeeds via a patch mechanism (red circles in myocytes) and they survive this injury. If, on the other hand, the myocyte is deficient in vitamin E, repair fails, injured myocytes die and eventually myopathy develops.

Methods

Laser repair assay

Cultured cells were wounded in PBS, with or without 1.2 mM Ca2+, containing 2.5 μM FM 1–43 (Invitrogen). Laser injury was produced using a 2 photon laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss) coupled to a 10-W Argon/Ti-sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics Lasers Inc.) at 100% power, five laser iterations (C2C12) or one laser iteration (HeLa and BS-C-1), and a 15 pixels diameter circle bleach area placed over the membrane edge. Fluorescence intensity over time was quantified in a measurement window drawn in outline around cells using Zeiss LSM 510 software. Mouse soleus was secured to a 35-mm culture dish by a drop of New-Skin liquid bandage (Medtech) and bathed in Tyrode solution: 128 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.36 mM CaCl2 (not added for –Ca condition), 20 mM NaHCO3, 0.36 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM glucose, pH 7.4. The plasma membrane was targeted for laser injury at 100% power, 100 iterations and using a 5×35 pixels bleach area. Fluorescence, in a 120 μm diameter around the injury site, was monitored. Fibre contractions were often observed in which case refocusing was performed. Initial fluorescence before injury was recorded, and subtracted from the fluorescence of all other time points.

Animals

Mice, C57BL/6, were between 6 months and 1 year of age. All protocols for animal use and euthanasia were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care Committee at the Medical College of Georgia and were in accordance with NIH guidelines.

Cells and cell treatments

C2C12 (myoblasts), HeLa or BS-C-1 cells were loaded by addition of α-tocopherol (a 96% pure, based on high-performance liquid chromatography, racemic mixture purchased from Sigma) or Trolox (Sigma) dissolved in ethanol, or HRP, DTT, ascorbic acid (all from Sigma) dissolved in PBS, to DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) for 18–48 h. Cells or whole muscles were washed twice in PBS or Tyrode, respectively, before assessment. Hydrogen peroxide or thimerosal (Sigma) was added directly to PBS or Tyrode before laser analysis. Whole muscle was loaded with 1 mM Trolox in Tyrode buffer for 1 h on ice before laser injury.

In vitro diabetic cell model

BS-C-1 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 30 mM glucose or mannitol11, and passaged twice weekly for 10 weeks. Cells were loaded with vitamin 24 h before laser wounding.

Mechanical injury assay

HeLa cells cultured in a 96-well plate were washed free of exogenous vitamin after 24 h of loading. Scraping was done in PBS containing 1.2 mM Ca2+, or distilled water using a 96-well transfer device consisting of 96 spring-loaded metal pushpins. Survival was assessed using a Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Molecular Probes) according to manufacturer's instructions after transferring scraped cells to a fresh plate. The 'live/dead' fluorescence ratio, Calcein-AM (ex/em 495 nm/515 nm) to ethidium homodimer (ex/em 495 nm/635 nm) ratio, was determined after 1 h of incubation using a fluorescent plate reader (FLx800, BioTek). This ratio was then compared with cells plated at the same concentration, but not wounded, to determine percent cell survival.

Image processing

Images were taken using a ×40 IR-Acroplan lens, 0.8 numerical aperture, using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope, and LSM 510 software for image analysis. Images were rotated, cropped and reduced in size. No false colouring or γ-adjustments was performed for quantifications of fluorescence intensity.

Statistical analysis

Prism 5.0 software was used to compute analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post analyses of the 'live/dead' data, and repeated measures of ANOVA with Tukey's post analyses for all laser data. P<0.05 was considered to be significant, and the n values given represent the minimum number of cells assayed.

Author contributions

A.C.H. designed and performed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. A.K.M. reviewed/edited the manuscript. P.L.M. contributed to the design of experiments and reviewed/edited the manuscript.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Howard, A.C. et al. Promotion of plasma membrane repair by vitamin E. Nat. Commun. 2:597 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1594 (2011).

Supplementary Material

HeLa cells laser wounded in the presence of calcium. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 300 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.

HeLa cells loaded with α-tocopherol prior to laser wounding in the presence of calcium. Cells were incubated with 200 μM α-tocopherol for 24 hours prior to injury. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 300 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.

HeLa cells loaded with α-tocopherol prior to laser wounding in the absence of calcium. Cells were incubated with 200 μM α-tocopherol for 24 hours prior to injury. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 300 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Laser wounding of an intact skeletal muscle myocyte in the presence of an oxidant challenge. A myocyte within a mouse soleus is injured in the presence of 5 mM H2O2. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 445 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Laser wounding of an intact skeletal muscle myocyte loaded with α-tocopherol and injured in the presence of an oxidant challenge. Mouse soleus muscle was loaded with 1 mM Trolox for 1 hour. A myocyte within the muscle was injured in the presence of 5 mM H2O2. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 445 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Sylvia Smith at the Medical College of Georgia for supplying mice. The Jain Foundation Incorporated, the Medical College of Georgia Pilot Study Research Program and the NIH (AR060565) financially supported this work. These financial contributors had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Bement W. M., Yu H. Y., Burkel B. M., Vaughan E. M. & Clark A. G. Rehabilitation and the single cell. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 95–100 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M. S., Caldwell R. W., Chiao H., Miyake K. & McNeil P. L. Contraction-induced cell wounding and release of fibroblast growth factor in heart. Circ. Res. 76, 927–934 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L. & Khakee R. Disruptions of muscle fiber plasma membranes. Role in exercise-induced damage. Am. J. Pathol. 140, 1097–1109 (1992). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L. & Ito S. Gastrointestinal cell plasma membrane wounding and resealing in vivo. Gastroenterology 96, 1238–1248 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L. & Ito S. Molecular traffic through plasma membrane disruptions of cells in vivo. J. Cell Sci. 96, 549–556 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q. C. & McNeil P. L. Transient disruptions of aortic endothelial cell plasma membranes. Am. J. Pathol. 141, 1349–1360 (1992). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L. Cellular and molecular adaptations to injurious mechanical force. Trends Cell Biol. 3, 302–307 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L. & Steinhardt R. A. Plasma membrane disruption: repair, prevention, adaptation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 697–731 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal D. & Campbell K. P. Dysferlin and the plasma membrane repair in muscular dystrophy. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 206–213 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal D. et al. Defective membrane repair in dysferlin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Nature 423, 168–172 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard A. C., McNeil A. K., Xiong F., Xiong W.- C. & McNeil P. L. A novel cellular defect in diabetes: membrane repair failure. Diabetes 60, 3034–3043 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel E., Machlin L. J., Filipski R. & Nelson J. Influence of age on the vitamin E requirement for resolution of necrotizing myopathy. J. Nutr. 110, 1372–1379 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai S. R. et al. Concomitant brainstem axonal dystrophy and necrotizing myopathy in vitamin E-deficient rats. J. Neurol Sci. 123, 64–73 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam E., Thomas P. K., King R. H., Goss-Sampson M. A. & Muller D. P. Experimental vitamin E deficiency in rats. Morphological and functional evidence of abnormal axonal transport secondary to free radical damage. Brain 114, 915–936 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. K. et al. Myopathy in vitamin E deficient rats: muscle fibre necrosis associated with disturbances of mitochondrial function. J. Anat. 183, 451–461 (1993). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K. E., Motley A. K., May J. M. & Burk R. F. Combined selenium and vitamin C deficiency causes cell death in guinea pig skeletal muscle. Nutr. Res. 29, 213–219 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K. E. et al. Combined deficiency of vitamins E and C causes paralysis and death in guinea pigs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 77, 1484–1488 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goettsch M. & Pappenheimer A. M. Nutritional muscular dystrophy in the guinea pig and rabbit. J. Exp. Med. 54, 145–165 (1931). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappenheimer A. M. & Goettsch M. Nutritional myopathy in ducklings. J. Exp. Med. 59, 35–42 (1934). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon R. H. Effect of Vitamin E on spontaneous-occurring necroses in striated muscle of ducks. J. Comp. Pathol. 74, 85–89 (1964). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M. J., Jones D. A. & Edwards R. H. Vitamin E and skeletal muscle. Ciba Found Symp. 101, 224–239 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville H. E., Ringel S. P., Guggenheim M. A., Wehling C. A. & Starcevich J. M. Ultrastructural and histochemical abnormalities of skeletal muscle in patients with chronic vitamin E deficiency. Neurology 33, 483–488 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro R. P., Dentinger M. P., Rodichok L. D., Barron K. D. & Satya-Murti S. Muscle pathology in Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome and vitamin E deficiency. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 86, 378–387 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi L. G. Reversibility of human myopathy caused by vitamin E deficiency. Neurology 29, 1182–1186 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ble A. et al. Lower plasma vitamin E levels are associated with the frailty syndrome: the InCHIANTI study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 278–283 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano S. et al. Mobility and molecular orientation of vitamin E in liposomal membranes as determined by 19F NMR and fluorescence polarization techniques. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 303, 10–14 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy S., Bai N. J. & George T. Mechanism of oxidative lysis and lipid peroxidation of vitamin E-deficient erythrocytes. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 21, 361–364 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaja S. I., Aigbe P. E., Gbenebitse S. & Temiye E. O. Changes in erythrocytes following supplementation with alpha-tocopherol in children suffering from sickle cell anaemia. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 12, 110–114 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesoriere L. et al. Oral supplements of vitamin E improve measures of oxidative stress in plasma and reduce oxidative damage to LDL and erythrocytes in beta-thalassemia intermedia patients. Free Radic. Res. 34, 529–540 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad I. & Suhail M. Protective role of vitamin E on mefenamic acid-induced alterations in erythrocytes. Biochemistry (Mosc) 67, 945–948 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopec-Szlezak J., Grabarczyk M., Szczepanska I. & Furman S. Protective effects of vitamins E and C on erythrocytes in blood preserved in ACD solution and stored at 4 degrees C. Haematologia (Budap) 21, 219–226 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Marques M. L., Lucio Cazana F. J. & Rodriguez Puyol M. In vitro response of erythrocytes to alpha-tocopherol exposure. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 56, 311–315 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oski F. A. & Barness L. A. Hemolytic anemia in vitamin E deficiency. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 21, 45–50 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P. J. Is the distribution of alpha-tocopherol in membranes consistent with its putative functions? Biochemistry (Mosc) 69, 58–66 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton G. W. et al. Biological antioxidants. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 311, 565–578 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacheck J. M., Milbury P. E., Cannon J. G., Roubenoff R. & Blumberg J. B. Effect of vitamin E and eccentric exercise on selected biomarkers of oxidative stress in young and elderly men. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 34, 1575–1588 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacheck J. M. & Blumberg J. B. Role of vitamin E and oxidative stress in exercise. Nutrition 17, 809–814 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meydani M. et al. Protective effect of vitamin E on exercise-induced oxidative damage in young and older adults. Am. J. Physiol. 264, R992–998 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meydani M. et al. Antioxidant response to exercise-induced oxidative stress and protection by vitamin E. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 669, 363–364 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag T. J. & Parker R. S. Influence of major structural features of tocopherols and tocotrienols on their omega-oxidation by tocopherol-omega-hydroxylase. J. Lipid. Res. 48, 1090–1098 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L., Miyake K. & Vogel S. S. The endomembrane requirement for cell surface repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 4592–4597 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt R. A., Bi G. & Alderton J. M. Cell membrane resealing by a vesicular mechanism similar to neurotransmitter release. Science 263, 390–393 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longnecker M. P. et al. Serum alpha-tocopherol concentration in relation to subsequent colorectal cancer: pooled data from five cohorts. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 84, 430–435 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L., Murphy R. F., Lanni F. & Taylor D. L. A method for incorporating macromolecules into adherent cells. J. Cell Biol. 98, 1556–1564 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzio M., Nunes C., Gaspar D., Ferreira H., Lima J.L.F.C. & Reis S. Antioxidant activity of vitamin E and Trolox: understanding the factors that govern lipid peroxidation studies in vitro. Food Biophys. 4, 312–320 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Barclay L. R., Artz J. D. & Mowat J. J. Partitioning and antioxidant action of the water-soluble antioxidant, Trolox, between the aqueous and lipid phases of phosphatidylcholine membranes: 14C tracer and product studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1237, 77–85 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi G.- Q., Alderton J. M. & Steinhardt R. A. Calcium-regulated exocytosis is required for cell membrane resealing. J. Cell Biol. 131, 1747–1758 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T. et al. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell 92, 759–772 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchward M. A. et al. Specific lipids supply critical negative spontaneous curvature--an essential component of native Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion. Biophys. J. 94, 3976–3986 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford A., Atkinson J., Fuller N. & Rand R. P. The effect of vitamin E on the structure of membrane lipid assemblies. J. Lipid Res. 44, 1940–1945 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May J. M., Qu Z. C. & Mendiratta S. Protection and recycling of alpha-tocopherol in human erythrocytes by intracellular ascorbic acid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 349, 281–289 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amelink G. J., van der Wal W. A., Wokke J. H., van Asbeck B. S. & Bar P. R. Exercise-induced muscle damage in the rat: the effect of vitamin E deficiency. Pflugers Arch. 419, 304–309 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomer R. J., Goldfarb A. H., McKenzie M. J., You T. & Nguyen L. Effects of antioxidant therapy in women exposed to eccentric exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 14, 377–388 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli F. & Iuliano L. Do statins cause myopathy by lowering vitamin E levels? Med. Hypotheses 74, 707–709 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon M. et al. Eccentric muscle contractions induce greater oxidative stress than concentric contractions in skeletal muscle. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 32, 273–281 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Meulen J. H., McArdle A., Jackson M. J. & Faulkner J. A. Contraction-induced injury to the extensor digitorum longus muscles of rats: the role of vitamin E. J. Appl. Physiol. 83, 817–823 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragno M. et al. Oxidative stress impairs skeletal muscle repair in diabetic rats. Diabetes 53, 1082–1088 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcuzzo S. et al. Hind limb muscle atrophy precedes cerebral neuronal degeneration in G93A-SOD1 mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a longitudinal MRI study. Exp. Neurol. 231, 30–37 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M. & Martin L. J. Skeletal muscle-restricted expression of human SOD1 causes motor neuron degeneration in transgenic mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2284–2302 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. et al. Vitamin E intake and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a pooled analysis of data from 5 prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 173, 595–602 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

HeLa cells laser wounded in the presence of calcium. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 300 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.

HeLa cells loaded with α-tocopherol prior to laser wounding in the presence of calcium. Cells were incubated with 200 μM α-tocopherol for 24 hours prior to injury. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 300 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.

HeLa cells loaded with α-tocopherol prior to laser wounding in the absence of calcium. Cells were incubated with 200 μM α-tocopherol for 24 hours prior to injury. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 300 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Laser wounding of an intact skeletal muscle myocyte in the presence of an oxidant challenge. A myocyte within a mouse soleus is injured in the presence of 5 mM H2O2. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 445 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Laser wounding of an intact skeletal muscle myocyte loaded with α-tocopherol and injured in the presence of an oxidant challenge. Mouse soleus muscle was loaded with 1 mM Trolox for 1 hour. A myocyte within the muscle was injured in the presence of 5 mM H2O2. Frame rate is 10/second, frame interval 5 seconds, total duration 445 seconds. Scale bar, 50 μm.