Abstract

We examined how the perceived age of adult faces is affected by adaptation to younger or older adult faces. Observers viewed images of a synthetic male face simulating ageing over a modelled range from 15 to 65 years. Age was varied by changing shape cues or textural cues. Age level was varied in a staircase to find the observer’s subjective category boundary between “old” and “young”. These boundaries were strongly biased by adaptation to the young or old face, with significant aftereffects induced by either shape or textural cues. A further experiment demonstrated comparable aftereffects for photorealistic images of average older or younger adult faces, and found that aftereffects showed some selectivity for a change in gender but also strongly transferred across gender. This transfer shows that adaptation can adjust to the attribute of age somewhat independently of other facial attributes. These findings suggest that perceived age, like many other natural facial dimensions, is highly susceptible to adaptation, and that this adaptation can be carried by both the structural and textural changes that normally accompany facial ageing.

Keywords: Adaptation, Age, Face perception, Shape perception, Texture perception

The human face changes systematically throughout the lifespan, providing potent clues to an individual’s age. The attribute of age is in turn a fundamental characteristic of the face that drives many important perceptual and social judgements, from recognition to mate selection to classifying an individual as a minor or elder (Berry & McArthur, 1986; George & Hole, 2000; Rhodes, 2009). The cosmetic industry provides testament to the importance individuals also place on the age revealed by their own face. Individuals can accurately judge age even in unfamiliar faces, and thus are highly sensitive to the facial variations that are diagnostic of age (Burt & Perrett, 1995; George & Hole, 2000). Thus, the perception of age is arguably an important if not central aspect of the process of face perception.

In this study, we asked how the perception of age from a face can be altered by visual adaptation to faces. Adaptation can strongly affect the perception of many facial attributes (Rhodes et al., 2005; Webster & MacLeod, in press). These include the perceived configuration or shape of the face (Webster & MacLin, 1999), its identity (Leopold, O’Toole, Vetter, & Blanz, 2001), and such characteristics as the perceived gender or ethnicity of the individual (Webster, Kaping, Mizokami, & Duhamel, 2004). Adaptation also biases the perception of many changeable aspects of the face such as expressions (Fox & Barton, 2007; Hsu & Young, 2004; Webster et al., 2004) or gaze direction (Calder, Jenkins, Cassel, & Clifford, 2008) or viewpoint (Fang & He, 2005). These aftereffects are thought to at least partly reflect sensitivity changes at high and possibly face-specific levels of visual coding because they show substantial transfer across image differences such as size, orientation, or position changes that alter the retinal image but preserve the perceived object (Afraz & Cavanagh, 2008; Leopold et al., 2001; Watson & Clifford, 2003; Zhao & Chubb, 2001); and can show selectivity for high-level perceptual categories rather than physical image similarity (Bestelmeyer et al., 2008; Rotshtein, Henson, Treves, Driver, & Dolan, 2005). Thus, the adaptation may reveal how processes underlying face perception may be calibrated, and in particular how the norms central to face perception are established and updated by experience (Rhodes et al., 2005; Webster & MacLeod, in press). Given the many characteristics of faces that have been shown to be adaptable, it is likely that perceived age would also show similar aftereffects. Studies have explored how adaptation to properties such as gender or eye-spacing transfer across changes in face age (Barrett & O’Toole, 2009; Little, DeBruine, Jones, & Waitt, 2008). Yet little work has been done to directly address how the attribute of age itself is affected by adaptation.

The effects of adaptation on age are also of interest because the age of a face is carried by many different potential cues, which could in principle differ in how adaptable they are. During development there are pronounced structural changes in the shape of the head, facial features, and their configuration as different elements of the face mature at different rates (Berry & McArthur, 1986; Enlow, 1982). This general growth ends by roughly 20 years, yet throughout adulthood the configuration of the face continues to change and is accompanied by numerous textural and colour changes in skin and hair and in the prominence and shape of local features such as the eyes and lips (Burt & Perrett, 1995; Rhodes, 2009). Both shape cues and texture and colour information have been shown to be important for age judgements (Burt & Perrett, 1995; George & Hole, 2000; O’Toole, Vetter, Volz, & Salter, 1997). Yet the roles of shape and surface information have rarely been parcelled out in studies of face adaptation (Jiang, Blanz, & O’Toole, 2006). We asked to what extent adaptation might adjust to both types of properties in faces spanning a wide range of adult ages. To examine this we used a software program designed to simulate natural characteristics of faces that allowed parameters controlling shape and textural cues to be manipulated independently. Our results suggest that both types of cues strongly affected adaptation. This suggests that like other facial attributes, adaptation may play an important role in calibrating the perception of age, and that this calibration is probably driven by both the configural and surface characteristics of the face. A preliminary account of this work was given in O’Neil, Webster, and Webster (2008).

METHODS

Stimuli

We used two sets of face stimuli. The first set was composed of synthetic face images created with Singular Inversions FaceGen Modeller 3.2. This software incorporates a 3-D morphable model of faces (Blanz & Vetter, 1999) to allow face images to be created and varied along a number of natural dimensions including identity, gender, ethnicity, and expression. Such models have been widely used in studies of face adaptation since their introduction by Leopold et al. (2001), and faces derived specifically from FaceGen have been employed in a number of other recent studies of face perception (e.g., Oosterhof & Todorov, 2008; Russell, Sinha, Biederman, & Nederhouser, 2006). The model was based on 3-D imaging (Venus 3D from 3D Metrics) of 272 individual male and female faces that included a range of ethnicities and spanned ages ranging from 12 to 67 years, with all faces captured under identical lighting conditions, and with age controls defined by a linear regression on the entire dataset (Andrew Beatty, Singular Inversions, personal communication). Separate regressions on the image shape and colour subspaces provided separate controls for the shape and textural properties of the face. For ageing, shape manipulations mainly affected the structure of the jaws, nose, and mouth while preserving texture and pigmentation cues. Texture manipulations affected skin colour and texture and the shape of local features but did not change the spatial configuration. (Shape and texture are thus varied independently in the model, but we note that texture is not in general independent of shape in image capture since the local luminance depends on the lighting and viewing geometry.) For experiments, the face had a constant identity defined by an “average” male (set by selecting the “set average” option for the “all races” sliders), with characteristics defining ages ranging from 15 to 65 years. The faces were rendered using the same angle and default settings for lighting, and were created without hair or other distinguishing external features.

The second set of face images was taken from the face research website www.faceresearch.org (L. M. DeBruine and B. C. Jones, Department of Psychology, University of Aberdeen), and corresponded to morphs of frontal view face photographs combined to represent the average characteristics of younger or older adult Caucasian faces. (The age range of the contributing faces was unspecified). An example of their morphing procedure is given in DeBruine, Jones, Unger, Little, and Feinberg (2007). These stimuli had the advantage of providing photorealistic images of faces while still representing prototypical characteristics, thus reducing the possibility that individuals might be adapting to idiosyncratic features of an individual face. Separate prototypes were tested for male and female faces. The images were cropped with an oval mask to remove hair and other external features.

For both stimulus sets we created a finely graded series of images by morphing between a single old and young face image. The resulting images thus did not correspond directly to a specific age, but varied systematically in perceived age. They thus allowed us to test whether this perception was biased by prior adaptation to a young or old face.

Procedure

Stimuli were displayed on a NANAO FlexScan T2-20 CRT and were shown against a neutral grey background with a luminance of 8 cd/m2. Observers binocularly viewed the display in an otherwise dark room from 130 cm. At this distance the faces subtended roughly 4.4° in height and 3° in width. In the first experiment observers used the keypad to indicate the perceived age of the face. In the second and third experiments they instead made a forced choice response to indicate whether the face appeared “old” or “young”. Procedures specific to each experiment are noted later.

Participants

Observers included author SO and 19 students at the University of Nevada who participated for course credit and who were unaware of the aims of the experiment. Different observers participated in different subsets of the experiments (with author SO tested in Experiments 1 and 2 and represented as Subject S1 in Figure 4). All participants were younger adults ranging in age from 20 to 32. Participation was with informed consent and all procedures followed protocols approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

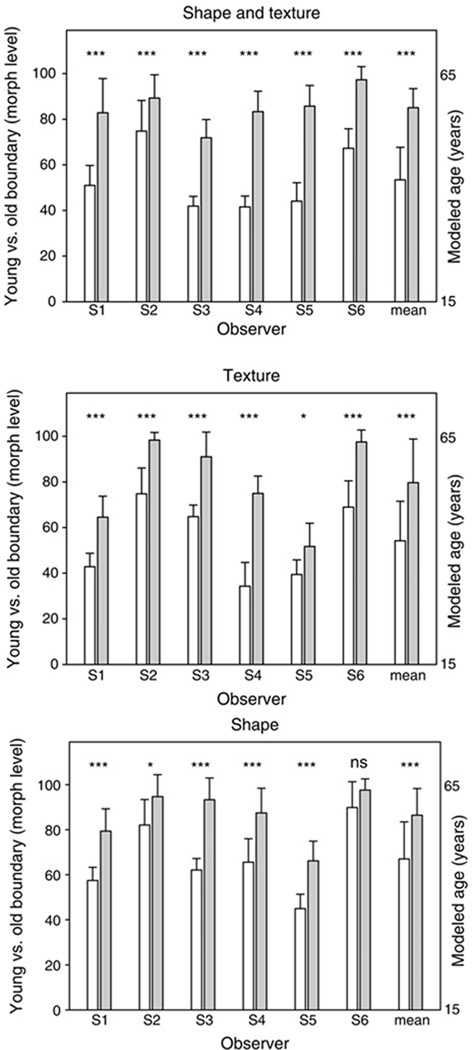

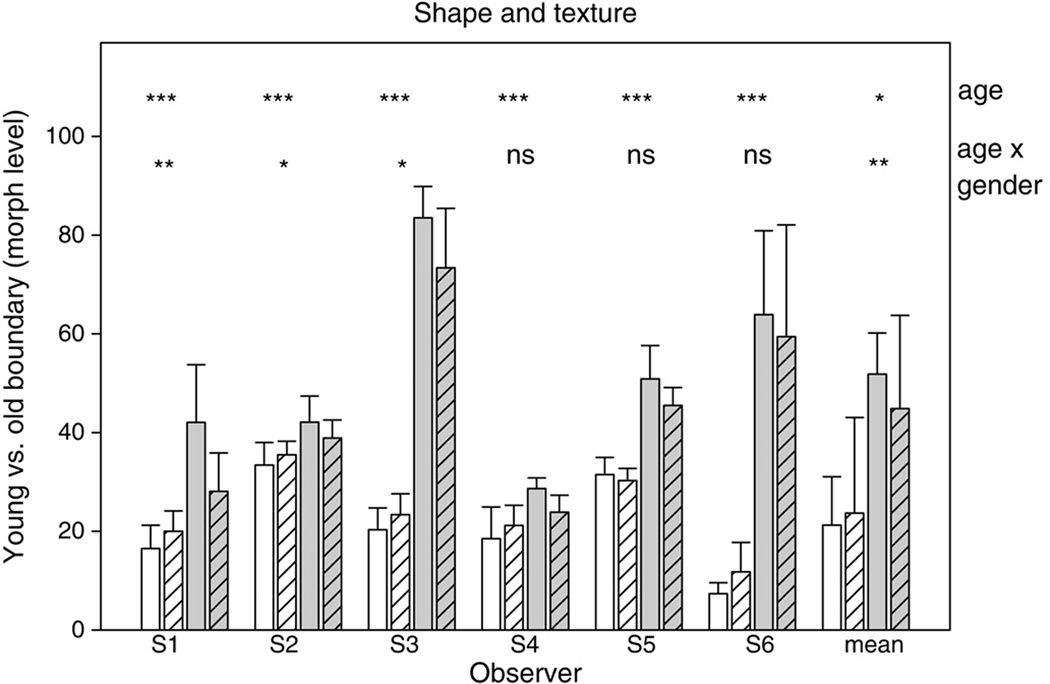

Figure 4.

Morph level chosen as the category boundary for “old” vs. “young” faces after adapting to the young or old face. The three panels plot the settings when adapt and test stimuli varied in both texture and shape (top), texture only (middle), or shape only (bottom). In each, bars show the mean and standard deviation of the settings for each individual observer or for the mean of all observers (right-hand bars), after adaptation to the young (white bars) or old (grey bars) face. Significant differences between the settings for young vs. old adaptation are indicated by the corresponding asterisks (* p < .05, ***p < .001, ns = not significant).

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Perceived age variations in the faces

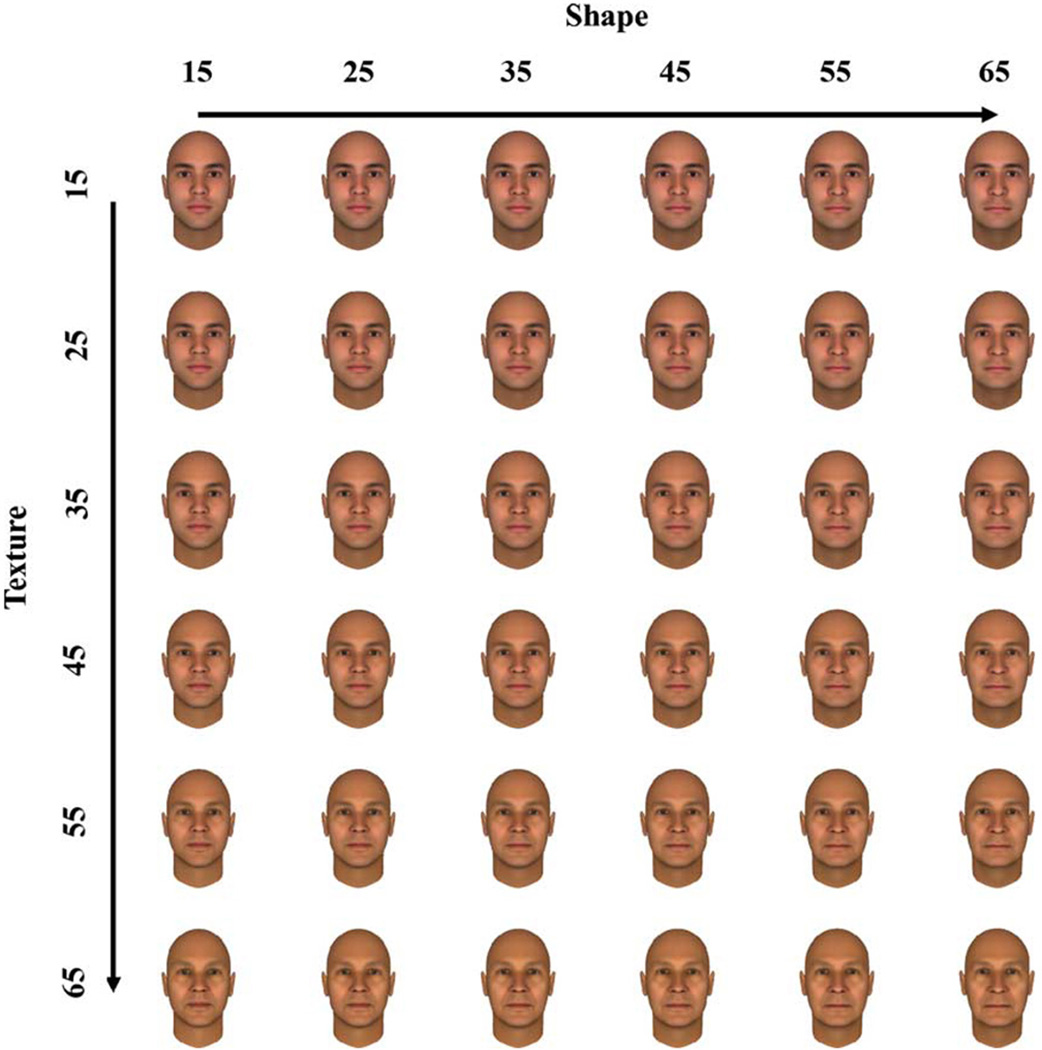

Before testing for adaptation effects with the stimuli, we carried out an initial experiment to verify that the artificial face images did reliably vary in perceived age and that observers were sensitive to these variations. Images of the male face were set within the FaceGen program to ages between 15 and 65 years in steps of 5 years. The age was varied separately along the dimensions of shape and texture, forming an 11×11 matrix of stimuli (Figure 1). Each face was shown until the observer estimated its age. Different images from the matrix were displayed in random order until each face was shown four times.

Figure 1.

Examples of the face images aged by independently varying the shape cues or textural cues in the images. The faces depicted show modelled age characteristics ranging from 15 to 65 years in steps of 10 years.

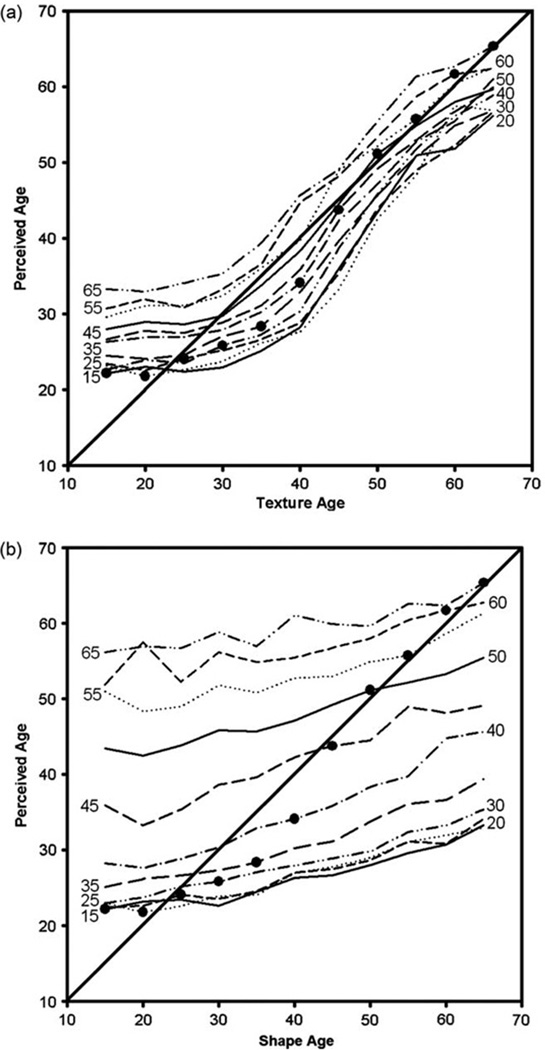

Figure 2 plots the age estimates based on the mean settings for 10 observers. The first panel plots the perceived age as a function of the modelled age based on textural variations, and the second panel plots the ratings as a function of the shape manipulation. For both, perceived age increased systematically with the stimulus cues, and the separate dimensions of texture and shape were largely additive.

Figure 2.

Estimated ages of the faces in the image array based on mean estimates from 10 observers. (A) Age estimates as a function of the model age based on texture variations. Individual lines plot the estimates when shape cues were fixed at different ages indicated by the adjacent labels. (B) Corresponding estimates shown as shape cues varied while texture cues remained fixed. Solid circles plot the settings when shape and texture were both set to the same model age and were thus consistent.

Subjects’ age ratings were very highly correlated with the stimulus levels in the images, r=.963, p < .001, averaged across subjects. Textural variations accounted for most of the variance in perceived age, r =.915, p < .001, whereas shape cues exerted a comparatively weak influence, r =.301, p < .001. Observers tended to underestimate the variation in the age of the nominally youngest images, so that the stimuli may not support the same level of high accuracy found with real face images (e.g., Burt & Perrett, 1995; George & Hole, 2000). Nevertheless, the results show that the synthetic images do strongly capture stimulus variations that observers associate with ageing, and suggest that these cues are more strongly carried by the textural variations in the images.

Experiment 2: Adaptation to shape and textural cues to age

In the second experiment we asked whether the perceived age of a face could be biased by adaptation to a young or old face. As noted in Methods, to test this we created finer variations in age by morphing between the images of the youngest (15 years) and oldest (65 years) faces in the stimulus set to generate a series of 100 images that varied in age based on modelled textural cues alone, shape cues alone, or both (Figure 3). In images where texture or shape was not varied the value was fixed at the level of the mean age (45 years). Observers first adapted by viewing either the young or old face for 90 s. A test face from the morph sequence was then shown for 1 s, interleaved with 3 s of readaptation. The test and adapting images were separated by 150 ms intervals during which the field remained grey. After each test presentation the observer judged whether the image appeared “young” or “old”, and subsequent images were varied in a staircase until the responses reversed 10 times. Observers made 10 repeated settings for each of the 6 (2 face ages × 3 stimulus cues) adapting conditions.

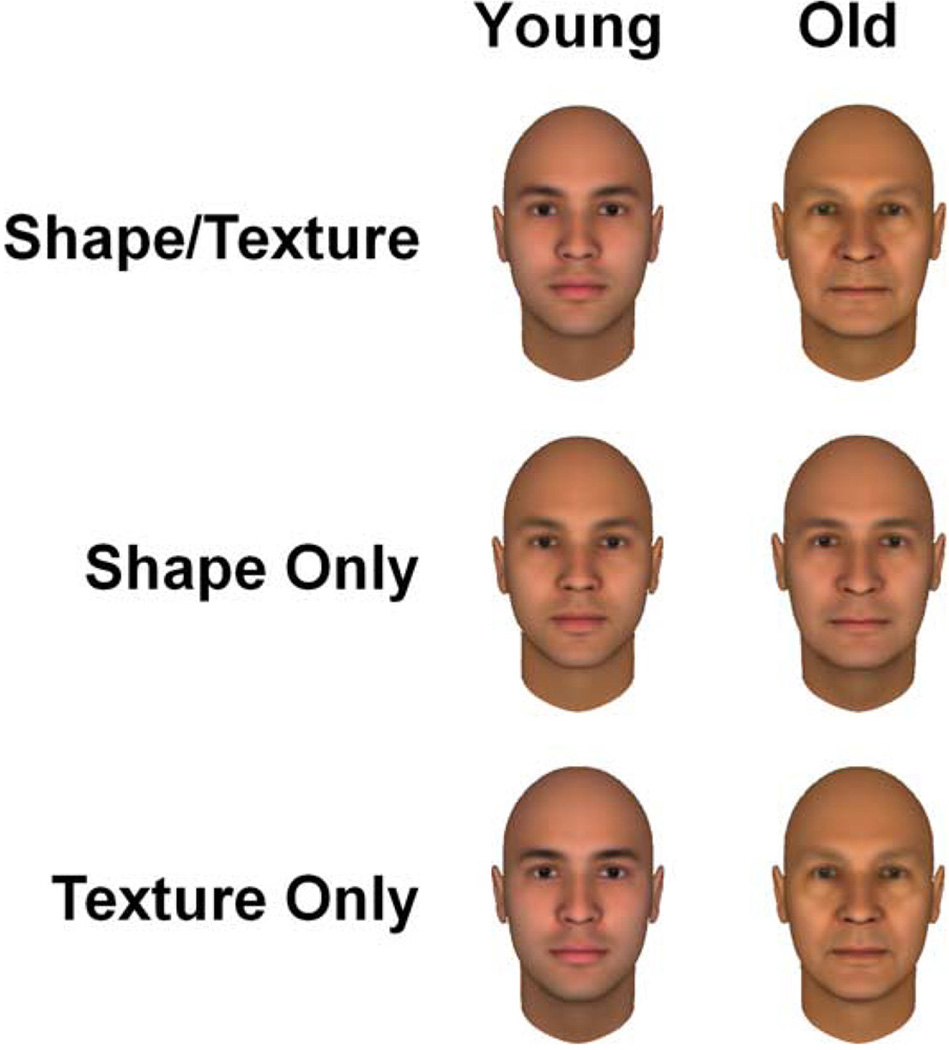

Figure 3.

Old and young adapting images based on combined shape and texture cues or on texture or shape only.

Figure 4 plots the average settings for each of the six individual observers tested, along with the mean settings averaged across the observers (rightmost bars). In these plots the individual bars show the average morph level corresponding to the perceived category boundary between the “young” and “old” faces, after adapting to a young or old face defined by the texture and/ or shape cues. Note that these morph levels correspond to the relative mixture of the two stimuli and not directly to the perceived age category. That is, a 50% morph represents an equal mixture of the two stimuli, but whether this level is perceived as “old” or “young” depends on the criterion and sensitivity of the observer as well as on the specific faces used to generate the morphs.

The three panels in Figure 4 show the settings when the adapt and test varied in both shape and texture (top), only in texture (middle), or only in shape (bottom). In each case adapting to faces of different ages induced different aftereffects in perceived age consistent with the aftereffects found for other facial categories (Webster et al., 2004), and thus strongly affected the old versus young category boundary. Specifically, adapting to a young or old face caused faces of an intermediate age to appear older or younger respectively. The category boundary for perceived age is thus shifted towards the adapting age. The observed shifts probably underestimate the size of the aftereffect because some observers’ settings reached a ceiling at the maximum age in the stimulus set after adapting to the old face (so that all face levels appeared “young”). That is, after adapting to the old face, the category boundary fell outside the range of stimuli used to measure the effect.

Adaptation effects were assessed in two-way (Adapt age × Age cue) ANOVAs for each individual observer, as well as in a repeated measures ANOVA of the mean settings across observers. All observers showed a significant main effect of age. As indicated in Figure 4, paired comparisons further showed that for all observers the effect of adapting age was significant when age was defined by texture and shape or by texture alone, and five of the six observers also showed significant differences in the settings when the adapt and test stimuli varied only in shape. Moreover, only three of the six observers showed a significant interaction between adapt age and the cue to age. Thus aftereffects for age were robust across both observers and the different stimulus cues. For the mean settings across observers, a significant repeated measures main effect was again found for adapting age, F(1, 5) = 170.09, MSE = 8.94, p < .001, , while the interaction between adapt age and cue was also significant, F(2, 10) = 4.60, MSE = 8.87, p =.038, . The main effect of age cue type (shape, texture, or both) was not significant but exhibited a possible trend, F(2, 10) = 3.64, MSE = 35.76, p = .065, . Note that this does not reflect the strength of age adaptation in each cue type, but instead the average perceived age within the cue type. Post hoc Holm-Sidak tests again showed that for the group data there were significant age effects for many cues. For age comparisons within the different types of ageing cues (all ps < .001); within young faces, shape was different from both texture (p = .031) and shape and texture cues combined (p = .013), but texture and both cue types were not significantly different from each other (p = .904). No significant differences were found for cue type comparisons in old faces. Thus again, the results suggest that both shape and textural cues can lead to robust adaptation effects for perception of facial age.

Experiment 3: Adaptation to age and gender

As a further test of the adaptation, we turned to the images of age and gender prototypes as adapt and test stimuli (Figure 5). This experiment was undertaken with several aims. First, the photorealistic stimuli were used to confirm that the adaptation aftereffects we found for the modelled faces would generalize to plausible images of real faces. Second, in the preceding experiment the test and adapt faces had the same size and position, and thus could not readily exclude adaptation resulting from local or low-level properties of the images. As a partial control for this, in the current experiment the adapt image was displayed at twice the size of the test face (3° × 4.2° adapt vs. 6° × 8.4° test). This reduced the possibility that the perceived age changes could be accounted for by local figural aftereffects. (Note, however, that this did not control for some low-level properties such as the average colour differences between the images, which vary with age in both image sets.) Finally, in the preceding experiment the face image was restricted to a single “identity” in order to focus on shape and textural cues to ageing; in the current case we instead tested how adaptation to age in one gender affected the perceived age of the same or different gender, in order to test whether the perception of age could be adapted independently of other natural attributes of faces.

Figure 5.

Face adapt images used to test for age aftereffects for prototypes of female and male Caucasian faces at young or old adult ages. Test images were approximately half the size of the adapt image and varied along the age continuum.

Aftereffects were again assessed with the same staircase procedure for six new observers, whose individual results are plotted in Figure 6, along with the mean settings averaged across observers. As in Figure 4, each bar plots the mean morph level chosen by each participant for the young versus old boundary, but now shown when the adapt and test faces had the same (solid) or different (hatched) genders. The absolute morph levels for these boundaries were substantially lower (i.e., shifted towards the young exemplars) for the photorealistic faces compared to the synthetic faces, and did not show a ceiling effect. This difference is not surprising given that the level corresponding to the boundary depends on the specific image pair used to generate the morph, but suggests that the photorealistic faces may better capture or better span the cues to ageing in the face.

Figure 6.

Morph level chosen as the category boundary for “old” vs. “young” faces before or after adapting to a young or old face with the same or different gender. Bars show the mean and standard deviation of the settings for each individual observer or for the mean of all observers (right-hand bars), after adaptation to the young (white bars) or old (grey bars) face. Uniform bars indicate the settings when the adapt and test face had the same gender (both female or both male), whereas hatched bars show settings when the adapt and test genders differed. Significant differences between the settings for young vs. old adaptation are indicated by the upper row of asterisks (age), and the significance of the interaction between age and gender congruency is indicated by the lower row (Age × Gender) (*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, ns = not significant).

Again, it is the relative difference between the settings after exposure to the “young” or “old” face that is important for assessing the adaptation effect. Two-way (Adapt age × Same vs. different gender) ANOVAs of each individual’s settings again revealed significant differences between the age boundaries after adaptation to a young or old face (as indicated by the significance levels for “age” in Figure 6). Thus robust age aftereffects were again found for the different set of faces and observers. A main effect of adapt age was also found for the mean settings pooled across observers, F(1, 5) = 7.85, MSE = 4.18, p =.038, . In contrast, the selectivity for gender was less pronounced. Interactions between congruency for gender and age reached significance in the individual settings for only three of the six observers. On the other hand, this interaction was significant in analysis of the group means, F(1, 5) = 20.86, MSE = 6.37, p = .006, . The results thus suggest that the adaptation to age can show some selectivity for gender, but also reveal that the adaptation can show substantial transfer across gender. The latter thus suggests that adaptation may at least partly adjust to the attribute of age even when the adapt and test faces differ in other characteristics.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the perceived age of an adult face can be significantly biased by prior exposure to a younger or older face. A similar finding has recently been reported by a parallel study of adaptation aftereffects in the perception of facial age (Schweinberger et al., 2010). These results add to a growing number of studies that have demonstrated that face adaptation can adjust to many of the dimensions that faces naturally vary along (Webster & MacLeod, in press). Given these previous reports, the finding of an aftereffect for age is not itself surprising. However, this adaptation effect remains important because age is a highly salient aspect of face perception and, as we noted, one that is central to many critical social judgements (Berry & McArthur, 1986; George & Hole, 2000; Rhodes, 2009). Judgements of age are also relatively unique in face perception insofar as observers can accurately estimate and assign values to the ages of faces across the full range of variation (as opposed, for example, to estimating how male or female, or happy or sad, the face appears). That is, whereas most face characteristics can only be verbally described coarsely, for age observers appear to have access to a very finely graded and conveniently numeric internal reference. This offers a potential advantage in future studies of face adaptation to explore how adaptation affects the full range of levels in the stimulus continuum, rather than a single level like the category boundary. For example, such measurements could address whether adaptation to a young or old face is renormalizing the perceived age of all faces and whether this shift is uniform across the range of ages, questions that are important for characterizing the actual pattern of face aftereffects.

The present results are also important in highlighting the salience of textural or surface cues in face adaptation. Most studies of face aftereffects have tended to focus on configural shape cues or leave shape and textural cues confounded. A notable exception is the work by Jiang et al. (2006), who showed that aftereffects for face identity could be driven by shape or reflectance properties of the image. Similarly, we found that both shape cues and textural cues to ageing could strongly drive the adaptation of apparent age. Pigmentation and surface reflectance properties of the face are emerging as increasingly important dimensions for face recognition (O’Toole, Vetter, & Blanz, 1999; Russell & Sinha, 2007; Russell et al., 2006; Tascereau-Dumouchel, Rossion, Schyns, & Gosselin, 2010) and have also been emphasized specifically for the perception of facial age (Burt & Perrett, 1995; George & Hole, 2000). It is likely that the perception of these surface cues are calibrated by adaptation in the same way that adaptation is important for normalizing the perception of shape information in face coding.

Many studies have examined whether adaptation to one facial attribute can transfer to faces that differ along other attributes (Webster & MacLeod, in press). For example, contingent aftereffects have been demonstrated for natural facial categories such as identity, gender, and ethnicity (Bestelmeyer, Jones, DeBruine, Little, & Welling, 2009; Jaquet & Rhodes, 2008; Jaquet, Rhodes, & Hayward, 2008; Little, DeBruine, & Jones, 2005; Little et al., 2008; Ng, Ciaramitaro, Anstis, Boynton, & Fine, 2006). We observed some selectivity of age adaptation for gender, a finding that is also consistent with the study of (Schweinberger et al., 2010). Little et al. (2008) also found contingent adaptation between age and eye spacing when tested on adult versus infant faces, which include larger age-related variations because of structural transformations in face shape during development (Enlow, 1982). Alternatively, Barrett and O’Toole (2009), using a noncontingent adaptation paradigm, found that gender aftereffects showed essentially complete transfer from adult to child faces, though weaker transfer in the opposite direction. The strong transfer we found between age and gender implies that an observer may adapt to the attribute of age at least partially independently of the specific identity carrying that attribute, which in turn suggests that the attributes of identity and age (at least over adulthood) might be represented somewhat independently. This is further consistent with results showing that age judgements are largely unaffected by the orientation or contrast inversion effects that disrupt identity recognition (George & Hole, 2000).

Age represents an interesting example of possible natural variation in the states of adaptation, for different individuals are exposed to different social environments that may often tend to be of similar age. As a result we might expect that, on average, observers at different ages and who interact with different ages would be adapted differently to facial age. Our present results do not address this because the observers were all young adult students with a potentially similar social cohort, yet it would be of interest in future studies to assess age judgements and adaptation effects across a larger range of observer ages. Studies have reported an “other-age” effect similar to the “other-race” effect, in which observers are better at discriminating ages within their own age group compared to a group with very different ages, though evidence for or against this effect varies (Anastasi & Rhodes, 2005; Burt & Perrett, 1995). Experience-dependent effects on face perception have also been found in observers who become more accurate in estimating age with training (Sorqvist & Eriksson, 2007), or who may become “naturally” trained to judge particular ages, such as sales clerks who routinely need to decide whether their customers are of legal age to purchase alcohol (Vestlund, Langeborg, Sorqvist, & Eriksson, 2009). Previous studies have noted that the other-race effect could in part arise through adaptation, if the adaptation tends to optimize face coding for the specific average face that an individual is exposed to (though evidence that adaptation can affect face discrimination is also mixed) (Ng, Boynton, & Fine, 2008; Rhodes, Maloney, Turner, & Ewing, 2007; Rhodes, Watson, Jeffery, & Clifford, 2010). Similarly, the other-age effect could be one manifestation of how different observers are naturally adapted to their specific environment. Another and perhaps more important consequence of adaptation is to maintain perceptual constancy by discounting irrelevant variations in the stimulus. In the case of ageing this could include adapting out the attribute of age to allow a more stable representation of identity among one’s cohorts. The processes of adaptation probably play a profound role in recalibrating perception as the visual system changes with ageing (Elliott, Hardy, Webster, & Werner, 2007; Werner & Schefrin, 1993). Our results suggest that the perception of age itself may also be continuously recalibrated.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Lisa DeBruine and Ben Jones for allowing the use of their face prototype images as stimuli. Supported by EY-10834.

REFERENCES

- Afraz SR, Cavanagh P. Retinotopy of the face aftereffect. Vision Research. 2008;48(1):42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasi JS, Rhodes MG. An own-age bias in face recognition for children and older adults. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2005;12(6):1043–1047. doi: 10.3758/bf03206441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SE, O’Toole AJ. Face adaptation to gender: Does adaptation transfer across age categories? Visual Cognition. 2009;17(5):700–715. [Google Scholar]

- Berry DS, McArthur LZ. Perceiving character in faces: The impact of age-related craniofacial changes on social perception. Psychology Bulletin. 1986;100(1):3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestelmeyer PE, Jones BC, Debruine LM, Little AC, Perrett DI, Schneider A, et al. Sex-contingent face aftereffects depend on perceptual category rather than structural encoding. Cognition. 2008;107(1):353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestelmeyer PEG, Jones BC, DeBruine LM, Little AC, Welling LLM. Face aftereffects suggest interdependent processing of expression and sex and of expression and race. Visual Cognition. 2009;18(2):255–274. [Google Scholar]

- Blanz V, Vetter T. A morphable model for the synthesis of 3D faces. Los Angeles: Paper presented at the Siggraph’99; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Burt DM, Perrett DI. Perception of age in adult Caucasian male faces: Computer graphic manipulation of shape and colour information. Proceedings in Biological Sciences. 1995;259(1355):137–143. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder AJ, Jenkins R, Cassel A, Clifford CWG. Visual representation of eye gaze is coded by a nonopponent multichannel system. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2008;137(2):244–261. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBruine LM, Jones BC, Unger L, Little AC, Feinberg DR. Dissociating averageness and attractiveness: Attractive faces are not always average. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2007;33(6):1420–1430. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.33.6.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott SL, Hardy JL, Webster MA, Werner JS. Aging and blur adaptation. Journal of Vision. 2007;7(6):8. doi: 10.1167/7.6.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enlow D. The handbook of facial growth. 2nd ed. London, UK: W. B. Saunders; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Fang F, He S. Viewer-centered object representation in the human visual system revealed by viewpoint aftereffects. Neuron. 2005;45(5):793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox CJ, Barton JJ. What is adapted in face adaptation? The neural representations of expression in the human visual system. Brain Research. 2007;1127(1):80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George PA, Hole GJ. The role of spatial and surface cues in the age-processing of unfamiliar faces. Visual Cognition. 2000;7:485–509. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SM, Young AW. Adaptation effects in facial expression recognition. Visual Cognition. 2004;11(7):871–899. [Google Scholar]

- Jaquet E, Rhodes G. Face aftereffects indicate dissociable, but not distinct, coding of male and female faces. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2008;34(1):101–112. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.34.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaquet E, Rhodes G, Hayward WG. Race-contingent aftereffects suggest distinct perceptual norms for different race faces. Visual Cognition. 2008;16(6):734–753. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Blanz V, O’Toole AJ. Probing the visual representation of faces with adaptation�A view from the other side of the mean. Psychological Science. 2006;17(6):493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold DA, O’Toole AJ, Vetter T, Blanz V. Prototype-referenced shape encoding revealed by high-level aftereffects. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4(1):89–94. doi: 10.1038/82947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little AC, DeBruine LM, Jones BC. Sex-contingent face after-effects suggest distinct neural populations code male and female faces. Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences. 2005;272B(1578):2283–2287. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little AC, DeBruine LM, Jones BC, Waitt C. Category contingent aftereffects for faces of different races, ages and species. Cognition. 2008;106(3):1537–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Boynton GM, Fine I. Face adaptation does not improve performance on search or discrimination tasks. Journal of Vision. 2008;8(1):1–20. doi: 10.1167/8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Ciaramitaro VM, Anstis S, Boynton GM, Fine I. Selectivity for the configural cues that identify the gender, ethnicity, and identity of faces in human cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2006;103(51):19552–19557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605358104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil SF, Webster SM, Webster MA. Adapting to age [Abstract] Journal of Vision. 2008;8:1141a. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhof NN, Todorov A. The functional basis of face evaluation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2008;105(32):11087–11092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805664105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole AJ, Vetter T, Blanz V. Three-dimensional shape and two-dimensional surface reflectance contributions to face recognition: An application of three-dimensional morphing. Vision Research. 1999;39(18):3145–3155. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole AJ, Vetter T, Volz H, Salter EM. Three-dimensional caricatures of human heads: Distinctiveness and the perception of facial age. Perception. 1997;26(6):719–732. doi: 10.1068/p260719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G, Maloney LT, Turner J, Ewing L. Adaptive face coding and discrimination around the average face. Vision Research. 2007;47(7):974–989. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G, Robbins R, Jaquet E, McKone E, Jeffery L, Clifford CWG. Adaptation and face perception: How aftereffects implicate norm based coding of faces. In: Clifford CWG, Rhodes G, editors. Fitting the mind to the world: Adaptation and aftereffects in high-level vision. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 213–240. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G, Watson TL, Jeffery L, Clifford CW. Perceptual adaptation helps us identify faces. Vision Research. 2010;50(10):963–968. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes MG. Age estimation of faces: A review. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2009;23:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rotshtein P, Henson RN, Treves A, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Morphing Marilyn into Maggie dissociates physical and identity face representations in the brain. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(1):107–113. doi: 10.1038/nn1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R, Sinha P. Real-world face recognition: The importance of surface reflectance properties. Perception. 2007;36(9):1368–1374. doi: 10.1068/p5779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R, Sinha P, Biederman I, Nederhouser M. Is pigmentation important for face recognition? Evidence from contrast negation. Perception. 2006;35(6):749–759. doi: 10.1068/p5490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinberger SR, Zaske R, Walther C, Golle J, Kovacs G, Wiese H. Young without plastic surgery: Perceptual adaptation to the age of female and male faces. Vision Research. 2010;50:2570–2576. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorqvist P, Eriksson M. Effect of training on age estimation. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2007;21:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Tascereau-Dumouchel V, Rossion B, Schyns PG, Gosselin F. Interattribute distances do not represent the identity of real-world faces. Frontiers in Psychology. 2010;1(159) doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00159. 151-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestlund J, Langeborg L, Sorqvist P, Eriksson M. Experts on age estimation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2009;50(4):301–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson TL, Clifford CWG. Pulling faces: An investigation of the face-distortion aftereffect. Perception. 2003;32(9):1109–1116. doi: 10.1068/p5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, Kaping D, Mizokami Y, Duhamel P. Adaptation to natural facial categories. Nature. 2004;428(6982):557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature02420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, MacLeod DIA. Visual adaptation and face perception. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0360. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, MacLin OH. Figural aftereffects in the perception of faces. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 1999;6(4):647–653. doi: 10.3758/bf03212974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner JS, Schefrin BE. Loci of achromatic points throughout the life span. Journal of the Optical Society of America. 1993;10A(7):1509–1516. doi: 10.1364/josaa.10.001509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Chubb C. The size-tuning of the face-distortion after-effect. Vision Research. 2001;41(23):2979–2994. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]