Background: Antifolates have been effective antimalarial drugs.

Results: Two proteins of P. falciparum facilitate membrane transport of folates but also of pABA, a precursor of folates.

Conclusion: At the concentration that pABA is in the human plasma it would have a higher impact on the parasite's fitness.

Significance: pABA metabolism could be a valuable target in the effort to further antimalarial chemotherapy.

Keywords: Folate Metabolism, Malaria, Membrane Transport, Plasmodium, Transporters, p-Amino Benzoic Acid (pABA), Folate Membrane Transporters

Abstract

Tetrahydrofolates are essential cofactors for DNA synthesis and methionine metabolism. Malaria parasites are capable both of synthesizing tetrahydrofolates and precursors de novo and of salvaging them from the environment. The biosynthetic route has been studied in some detail over decades, whereas the molecular mechanisms that underpin the salvage pathway lag behind. Here we identify two functional folate transporters (named PfFT1 and PfFT2) and delineate unexpected substrate preferences of the folate salvage pathway in Plasmodium falciparum. Both proteins are localized in the plasma membrane and internal membranes of the parasite intra-erythrocytic stages. Transport substrates include folic acid, folinic acid, the folate precursor p-amino benzoic acid (pABA), and the human folate catabolite pABAGn. Intriguingly, the major circulating plasma folate, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, was a poor substrate for transport via PfFT2 and was not transported by PfFT1. Transport of all folates studied was inhibited by probenecid and methotrexate. Growth rescue in Escherichia coli and antifolate antagonism experiments in P. falciparum indicate that functional salvage of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate is detectable but trivial. In fact pABA was the only effective salvage substrate at normal physiological levels. Because pABA is neither synthesized nor required by the human host, pABA metabolism may offer opportunities for chemotherapeutic intervention.

Introduction

Tetrahydrofolate (THF) derivatives are essential cofactors for single carbon transfer reactions in the synthesis of nucleic acids and methionine (1). Whereas humans rely on the dietary intake of preformed folates, many pathogenic microorganisms, including Plasmodium falciparum, are capable of de novo folate biosynthesis from the condensation of pteridines, p-amino benzoic acid (pABA)3 and glutamate. Consequently, antifolate drugs that target the biosynthesis and processing of folate cofactors have been effectively used in the treatment of infectious diseases, including P. falciparum malaria (2, 3).

P. falciparum parasites are also able to salvage preformed folates and related metabolites from the surrounding culture medium in vitro (4–6). The relationship between the biosynthetic and salvage pathways and their relative importance to parasite viability and antifolate drug susceptibility is poorly understood. The consensus view is that both processes are necessary for the parasite to thrive (2, 3, 6–13). Many studies have demonstrated that the salvage of folates and related metabolites added to the surrounding medium reduces the sensitivity of the parasite to antifolate drugs (5, 6, 14, 15). Presumably the salvage of folates will bypass steps in the de novo synthesis pathway, thus antagonizing the activity of these antifolate drugs (3).

Folates are di-anionic at physiological pH (pKa 2.3 and 8.3), and the efficient passage of these highly polar molecules through biological membranes generally requires specific membrane transporters. Indeed, a recent study has demonstrated that folate uptake by P. falciparum parasites is a specific energy-dependent, saturable process that can be inhibited by the classical anion transport inhibitors probenecid and furosemide (13). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that folate salvage is mediated by specific transporters.

Other studies have shown that probenecid (an inhibitor of anion membrane transport) markedly increases the sensitivity of P. falciparum to antifolate drugs both in vitro and in vivo (16, 17). The most logical explanation for the increased sensitivity to antifolates is due to probenecid inhibiting the transport of folates into the parasite (13, 16). These exciting findings illustrate the potential of blocking folate salvage transporters as a therapeutic strategy and give clues to the molecular basis of folate transport.

Here we report the identification and characterization of two folate transporters expressed in Xenopus oocytes and Escherichia coli. Confirmation of substrate preference and inhibitor specificity in cultured parasites supports a role for these plasma membrane transporters in folate salvage in P. falciparum. An apparent reliance of P. falciparum on the salvage of the folate precursor pABA, rather than 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, the principal circulating folate, offers new possibilities for potential antimalarial drug development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Reagents

Radiolabeled compounds [3′,5′,7,9-3H]folic acid (10 Ci/mmol), 5-[14C]methyltetrahydrofolate (52 mCi/mmol), and [3′,5′,7,9-3H(N)]folinic acid (10 Ci/mmol) were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO) or Moraveck (Brea, CA). Non-radiolabeled folates and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma or Schircks Laboratories (Jona, Switzerland). Restriction endonucleases were obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Oligonucleotides and molecular biology reagents were purchased from Invitrogen.

Parasite Culture and Drug Sensitivity Assays

Parasites of P. falciparum strains 3D7, HB3, K1, and Dd2 were maintained in continuous culture using standard methods (18, 19). Parasites were grown in folate and pABA free medium (see below) using O+ erythrocytes that had been exhaustively washed in folate and pABA free RPMI 1640. Drug sensitivity assays were performed as published (18) with parasite growth monitored by either [3H]hypoxanthine incorporation or SYBR Green fluorescence (20). Each sensitivity assay was performed in triplicate with a minimum of four experimental replicates. Folate and pABA-free culture media were 0.5% AlbumaxII (Invitrogen), folate and pABA-free RPMI 1640 (custom made by HyClone, ThermoScientific, UK), and 40 μm hypoxanthine, 2 μm glutamine, 20 μg/ml gentamycin, 0.2% sodium bicarbonate, and 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.4). Sulfadoxine (SDX), dapsone, cycloguanil, and pyrimethamine (PYR) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. pABA, pABA monoglutamate (pABAG1), pABA diglutamate (pABAG2), pteroic acid, dipteroic acid, folic acid (FA), folic acid diglutamate, folinic acid (FoA), methotrexate (MTX), and probenecid (PBN) were dissolved in 0.1 n sodium hydroxide. 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF) was dissolved in 0.5 m potassium phosphate, pH 7, and 1% v/v (128.2 mm) of 2-mercaptoethanol. Stock solutions were filtered through a 0.2 μm Millipore filter.

Sequence Analyses

MAL8P1.13 (referred to subsequently as PfFT1), PF11_0172 (referred to subsequently as PfFT2), and PF10_0215 open reading frames are reported in PlasmoDB5.3 (21). Others sequences were downloaded from GenBankTM (22). DNA sequences were analyzed with Staden package software. Multiple global alignments were performed with ClustalW 1.81 (23) and plotted with TeXshade (24). Protein transmembrane fragments were predicted with HMMTOP 2.0 (25) and plotted with TeXtopo (26).

Constructs Cloning

Gene cDNAs were synthesized with Thermoscript (Invitrogen) from total RNA of P. falciparum 3D7 and Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Gene-specific primers were as follows: E63 (5′-AGATCTCCACCATGGAAGATGACGACTTC) and E64 (5′-GGTAACCTTATTCCAAGGTTATGTC) for PfFT1 and E79 (5′-AGATCTCCACCATGATAGAAAAGTCTAA) and E66 (5′-GGTAACCTTATCCCTTGGATGTTTC) for PfFT2. Bases introduced to make a Kozak consensus sequence are underlined. Start and stop codons are presented in bold. Gene products were A-tailed with Taq polymerase and cloned into pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). All constructs were sequence-verified. For Xenopus laevis expression, genes were subcloned into the pKSM vector derived from pBluescript (Stratagene) (28). Directional cloning was carried out using the compatible restriction sites XhoI and SpeI. To make possible a direct subcloning (HindIII-EcoRI) of the human reduced folate carrier hRFC1 into pKSM, a carboxyl-terminal truncated version (537 amino acids) was used. Shorter, carboxyl-terminal truncated versions of hRFC1 (530 amino acids) are known to be functionally expressed in X. laevis oocytes (29).

E. coli Expression and Growth Assays

Strain BN1163 is an E. coli double gene replacement knock-out lacking both PabA and AbgT genes, a pABA synthesis enzyme, and the pABAG1 transporter (30, 31), and as such (E. coli ΔpabA/ΔabgT) this was used in the present study for the expression of the P. falciparum PfFT1 and PfFT2 synthetic genes with the codon optimized for E. coli expression (GenScript Corp., Piscataway, NJ). PfFT1 and PfFT2 were cloned into the tetracycline-resistant plasmid pLOI707HE between NotI and SacI sites (replacing the bla gene) (32). We added a Shine-Dalgarno sequence upstream of the transporter genes and replaced the first 49 amino acids in the case of PfFT1 and the first 35 amino acids in the case of PfFT2 with codons 1–37 of the Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 gene slr0642 as reported in Klaus et al. (31). E. coli BN1163 strain harboring the pLOI707HE recombinant constructs was cultured in 96-well microtiter plates in minimal medium (M9 salts, 0.1 mm CaCl2, 0.5 mm MgSO4, 0.4% glucose, 10 μg/ml tetracycline, 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol) (33) with 1 mm isopropyl-β-d-thio-galactoside. Culture absorbance at A600 was measured after overnight incubation at 37 °C.

X. laevis Oocytes Expression

Capped complementary RNA (cRNA) was transcribed in vitro using the Message Machine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Oocyte isolation was performed according to established procedures (34, 35). Stage V-VI oocytes were then selected and the following day injected with ∼50 nl of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water or cRNA solutions at 1 μg/μl using a semi-automatic injector (Drummond, Nanoject, Broomall, PA).

Solute Uptake Assays in Oocytes

After 3–5 days from cRNA injection, radiotracer uptake studies were carried out at 2 or 0.2 μCi/ml for 3H or 14C radiochemicals, respectively. At least 12 oocytes per group were incubated in 1 ml of Oocytes Ringer's solution, pH 7.4 (85 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm Na2HPO4, 1 mm CaCl2, 5 mm HEPES) at room temperature and then washed 12 times with Ringer's solution at 4 °C. Individual oocytes were collected and immersed in 1 ml of scintillation liquid. After overnight incubation, radioactivity was counted on a Wallac 1450 Microbeta scintillation counter.

Indirect Immunofluorescence Assays

Human erythrocytes infected with P. falciparum 3D7 were fixed with 10 pellet volumes of 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.01% glutaraldehyde (30 min) (36) and permeabilized with 10 pellet volumes of 0.1% Triton X-100 in 4% BSA followed by a PBS wash. Polyclonal antibodies from rabbit antisera were purified by protein G affinity binding. Antibodies against PfFT1 and PfFT2 were produced by immunizing rabbits with keyhole limpet hemocyanin-conjugated PfFT1 peptide QLIEKDINDDNHEN (amino acid residues 34–47) and PfFT2 peptide DPIVERTKSNGEGL (amino acid residues 13–26). Both peptides and antibodies were produced by GenScript. Anti-PfFT1 (0.811 mg/ml) and anti-PfFT2 (0.79 mg/ml) were used at 1:200 dilutions. The FITC-conjugated secondary antibody was purchased from Sigma (F0382) and used at 1:1000 dilutions. Cells mounted with VectaShield® HardSetTM mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) were observed using a confocal microscope Zeiss Axiovert 200 m (L5M 5Pascal laser modules).

Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Recombinant Constructs and Parasite Transfection

Recombinant PfFT1 and PfFT2 with GFP tags (cloned between AvrII and BsiWI sites in the pLN-ENR-GFP plasmid) were generated to transfect P. falciparum 3D7 as previously reported (37).

Data Analysis

Data are presented as the mean values and their S.E. Statistical analyses were performed as implemented in GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and detailed in the tables and figures.

RESULTS

Putative Folate Transporter Genes in P. falciparum Encode Transporters of the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) and the BT1 Family

MFS is the largest secondary transporter family with a diverse substrate range of small hydrophilic solutes that are transported in response to chemi-osmotic ion gradients (38). Two probable folate transporters were identified from the P. falciparum genomic data base: MAL8P1.13 (PfFT1) and PF11_0172 (PfFT2) (39). These are proteins of 505 and 455 amino acids, respectively, with 31% identity and 53% similarity to each other and with significant similarities (43.6% average) to members of the high affinity BT1 folate transporters family, part of the MFS (40) (TC 2.A.71 Transporter Classification Database).

The topology and sequence signatures of MFS proteins (38, 40) are present in PfFT1 and PfFT2. Both P. falciparum proteins contain a DX5GXRR sequence that is part of a larger MFS signature in the loop L2–3 (40) and one of the two arginines (PfFT1 R325; PfFT2 R311) usually present in the loop L8–9 of MFS proteins (supplemental Figs. S1–S3). The arginines are equivalent to the Leishmania FT1 R497, which has recently been identified as a substrate binding residue (41). The R113C/S mutation in L2–3 of the human proton-coupled folate transporter hPCFT (42) has been demonstrated to be a loss-of-function mutation in patients with hereditary folate malabsorption (43, 44). Transmembrane segments (H1-H12) mainly along H1 and H7 are much less conserved but known to contribute to the substrate binding domains (45).

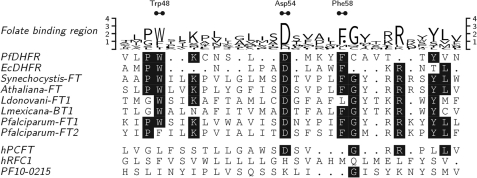

When PfFT1 and PfFT2 and functionally characterized members of the BT1 family were aligned to the folate synthesis enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), remarkable similarities were identified between the α-helix segment αB of P. falciparum DHFR that is known to interact with folates and antifolates (46) and residues of BT1 proteins preceding the DX5GXRR motif described above (Fig. 1). In particular Asp-54 of P. falciparum DHFR, which is crucial for inhibitor (pyrimethamine and WR99210 (Walter Reed Institute anti-DHFR antifolate 99210)) and substrate binding, corresponds to the well conserved first residue of DX5GXRR. Together with Asp-54, other residues (Trp-48 and Phe-58) of the active site of DHFR are also conserved in BT1 transporters (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Folate binding region. Residues 45–66 of P. falciparum DHFR aligned to E. coli DHFR (residues 19–36) as in (46) are shown. Other sequences are as in supplemental Figs. S1 and S3. Initial alignment was performed and prepared as in supplemental Fig. S3. Local alignment was optimized manually. Residues that interact with folate substrates and antifolates are marked at the top as Trp-48, Asp-54, and Phe-58 (46). Trp-48 is equivalent to the W100 in PfFT1, which is absent in PfFT2.

A third P. falciparum protein PF10_0215 has also been reported as a potential folate transporter (39). However, we observed no significant similarity between PF10_0215 and either PfFT1 or PfFT2. When aligned against other MFS/BT1 proteins, the absence of the BT1 signatures in PF10_0215 becomes clear (Fig. 1 and supplemental Figs. S1 and S3).

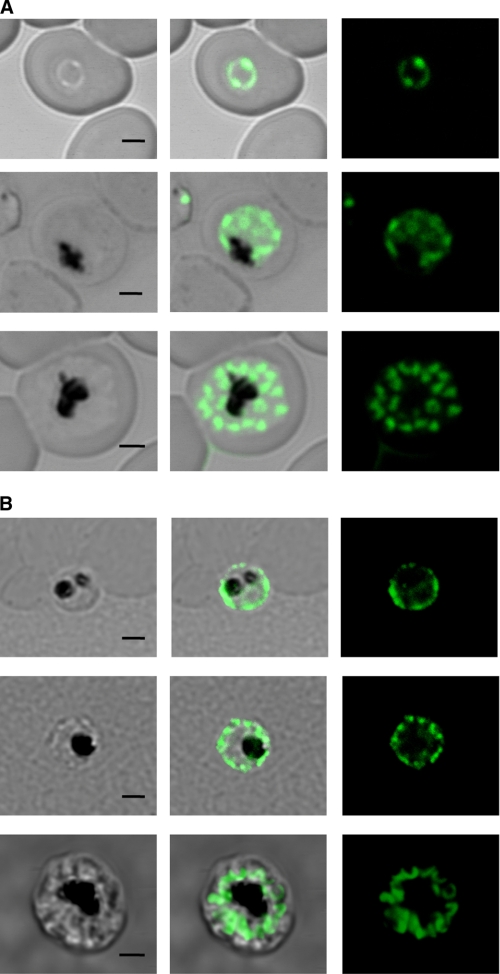

PfFT1 and PfFT2 Localize to the P. falciparum Plasma Membrane

We adopted two independent strategies for localization studies, transfection with GFP-tagged gene constructs and immunofluorescence. PfFT1 or PfFT2 were carboxyl-terminal-tagged with GFP by cloning in the GFP plasmid pLN-ENR-GFP (37) for subsequent transfection into P. falciparum erythrocytic stages. PfFT1 localized to the parasite plasma membrane of intraerythrocytic stages. In later trophozoite stages, some intracellular vesicular structures appear to be labeled (Fig. 2A). Transfection with the PfFT2-GFP fusion construct was unsuccessful, and so this protein was localized by indirect immunofluorescence. Subcellular localization of PfFT2 resembles that of PfFT1, with prominent labeling of the parasite plasma membrane and intracellular vesicles, with the strongest signal observed in trophozoites and schizonts (Fig. 2B). Immunofluorescence with the anti-PfFT1 antibody showed similar results (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Cytolocalization of P. falciparum folate transporters PfFT1 and PfFT2. A, fluorescence signals given by P. falciparum transformed with a PfFT1-GFP C-terminal fusion construct are shown. A trophozoite (top panels) shows a signal that coincides with the parasites plasma membrane. Dividing stages of early and late schizonts are in the two lower panels. In the schizonts the labeling of merozoite plasma membranes is apparent. B, indirect immunofluorescence of PfFT2 is shown. Permeabilized cells were labeled with an anti-PfFT2 antibody as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Again trophozoites (upper and middle panels) as well as merozoites in the schizont in the lower panel presented strong plasma membrane signal. Bars represent 2 μm.

PfFT1 and PfFT2 Expressed in Xenopus Oocytes Transport Folates and Folate Precursors

The X. laevis system has been successfully employed in the functional characterization of a number of mammalian folate transporters (47). As expected, we observed endogenous folate uptake, although we measured a greater level of folate uptake than was reported previously in Xenopus oocytes (48). More importantly, both PfFT1 and PfFT2 mediate the uptake of folates to levels significantly greater than the water-injected controls. Preliminary experiments using both fully oxidized and fully reduced folate substrates showed that uptake is linear for at least 1 h (data not shown). Later experiments were conducted over 40 min, which is within the linear phase of uptake.

Table 1 shows the uptake levels of folic acid by Xenopus oocytes expressing PfFT1 or PfFT2 versus water-injected controls. Both transporters are capable of transporting fully oxidized FA to significantly greater levels than the water-injected controls (p < 0.001). Furthermore, transport of folic acid was inhibited by an excess of unlabeled folic acid and by the folate precursor pABA (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Uptake of folic acid by Xenopus oocytes expressing PfFT1 or PfFT2

Shown is [3H]folic acid uptake over 40 min by oocytes injected with water or with cRNA for either of the PfFTs. Data are the means and S.D. Experimental groups contained 27–48 oocytes per group. Data were obtained from at least three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical analysis was carried out with Mann-Whitney U tests between groups of oocytes injected with PfFT1 or PfFT2 (rows) and between groups of oocytes incubated with different radiolabeled substrates (columns). NS (not significant) denotes p > 0.05.

| Substrate | Uptake of folic acid |

p values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water control | PfFT1 | PfFT2 | ||

| pmol/oocyte/h | ||||

| 30 nm [3H]folic acid | 1.07±0.27 | 2.92±0.48 | 3.45±0.71 | <0.001 |

| 30 nm [3H]folic acid + 200 μm folic acid | 0.42±0.16 | 1.21±0.39 | 1.07±0.27 | <0.01 |

| 30 nm [3H]folic acid + 200 μmpABA | 0.91±0.31 | 1.32±0.41 | 0.85±0.25 | NS |

| p values | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

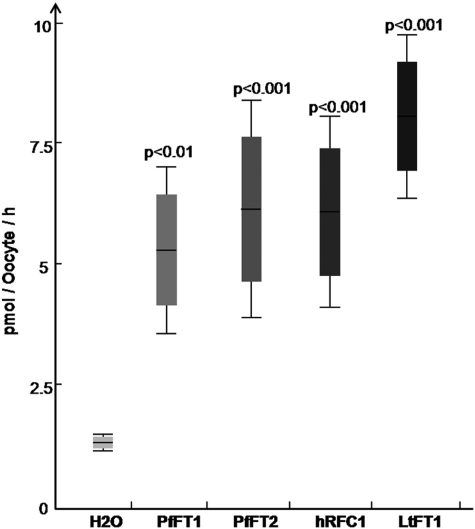

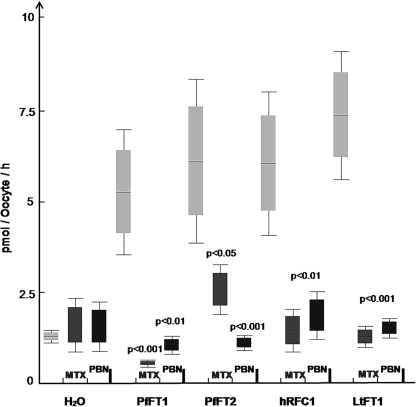

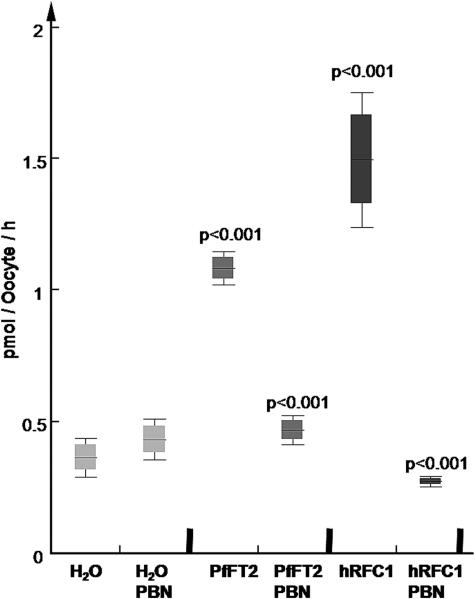

We have also investigated the transport of the fully reduced folate derivative folinic acid. Aside from its possible presence from clinical use, folinic acid would not normally be available to the parasite in vivo from host serum. However, folinic acid shares structural similarities to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate and offers the advantage of being considerably more stable (13). Fig. 3 shows a comparison of folinic acid uptake by Xenopus oocytes expressing either PfFT1, PfFT2, or (as positive controls) the human reduced folate carrier hRFC1 (49) or LtFT1 from Leishmania tarentolae (41). Oocytes expressing both the malarial transporters and the positive controls take up significantly more folinic acid than the water-injected controls (p < 0.001). In the case of PfFT1, PfFT2, and hRFC1, the differences are about 5-fold and about 7-fold for LtFT1 (Fig. 3). In all cases uptake of folinic acid is inhibited by 200 μm PBN (an organic anion transport inhibitor) and by 200 μm methotrexate, an antifolate transported by well characterized folate transporters such as hRFC1 (49) and LtFT1 (41) (Fig. 4). Both PBN and methotrexate have been shown to inhibit the uptake of folinic acid into P. falciparum parasites (13, 16). PBN has been shown to increase the sensitivity of parasites to antifolates both in vitro and in vivo (16, 17).

FIGURE 3.

Uptake of [3H]folinic acid in Xenopus-expressing PfFT1 and PfFT2. Oocytes injected with cRNA from PfFT1 and PfFT2 showed significantly higher uptake of [3H]folinic acid in comparison to the water-injected controls. Data are the mean and S.D. from at least 10 individual oocytes. Uptake was assessed over 40 min. The folate transporters hRFC1 (44) and LtFT1 (70) were used as positive controls. Although LtFT1 expression in Xenopus oocytes has not been reported, it consistently presented the highest levels of folate uptake. Significance values between groups of injected oocytes was calculated with non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test using data for at least three different experiments (n = 3).

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of PfFT1 and PfFT2 dependent [3H]folinic acid uptake in Xenopus by methotrexate and the organic anion inhibitor probenecid. Both methotrexate (MTX) and PBN at 200 μm significantly inhibited folinic acid uptake (dark rectangles) via PfFT1 and PfFT2. Significance values between groups of injected oocytes was calculated with non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test using data for at least three different experiments (n = 3).

We also looked at transport of the most abundant plasma folate, 5-MTHF. Unexpectedly we found that uptake of 5-MTHF by oocytes expressing PfFT1 was not significantly different from the water control (data not shown). Significant uptake of 5-MTHF was detected in oocytes expressing PfFT2 (Fig. 5). However, uptake of 5-MTHF by oocytes expressing this transporter was a third less than that seen with the positive control (hRFC1) and was much reduced compared with the uptake of folinic acid (Figs. 3 and 4).

FIGURE 5.

Uptake of 5-[14C]methyltetrahydrofolate in Xenopus-expressing PfFT2. Oocytes injected with PfFT2 accumulated 5-[14C]MTHF at values significantly above the water-control. hRFC1 is known to have high affinity for reduced folates (Km 2–4 μm), and used as positive control here it validates the expression system for uptake of this reduced folate. Data are the mean and S.D. of groups with 24–36 oocytes. PBN used at 200 μm significantly reduced 5-[14C]MTHF uptake in both groups. Significance values between groups of injected oocytes was calculated with non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test using data for at least three different experiments (n = 3).

Malaria parasites are thought to be capable of synthesizing the folate precursor pABA via the shikimate pathway (50). However, there are numerous reports of antagonism of antifolate drugs by external pABA, suggesting that pABA might also be salvaged (5, 6, 12, 14, 51, 52). For this reason and given the results above (Table 1) we were interested to see if pABA was transported by these malarial folate transporters. However, we found substantial uptake of pABA into water-injected oocyte controls and obtained a poor signal-to-noise ratio for measurement of uptake of radiolabeled pABA after expressing PfFT1 or PfFT2 in Xenopus oocytes. The presence of endogenous pABA transport in Xenopus oocytes and the potential for passive diffusion of substrate prompted us to seek an alternative expression system.

Expression of PfFT1 and PfFT2 in E. coli Facilitates the Usage of pABA

Folates cannot easily cross the inner membrane of E. coli, an organism that relies on biosynthesis rather than salvage of preformed folates (53). An E. coli mutant with impaired growth in the absence of exogenous pABA has been generated by gene replacements of both the pABA synthesis enzyme PabA and the pABAG1 transporter AbgT (ΔpabA/ΔabgT), thus impairing both the synthesis and the salvage of pABA (30, 31). Folate transporters of the BT1 family have been successfully characterized in this double mutant (30, 31, 54), and we have made use of this approach for the bacterial expression of PfFT1 and PfFT2 constructs in the E. coli ΔpabA/ΔabgT mutant.

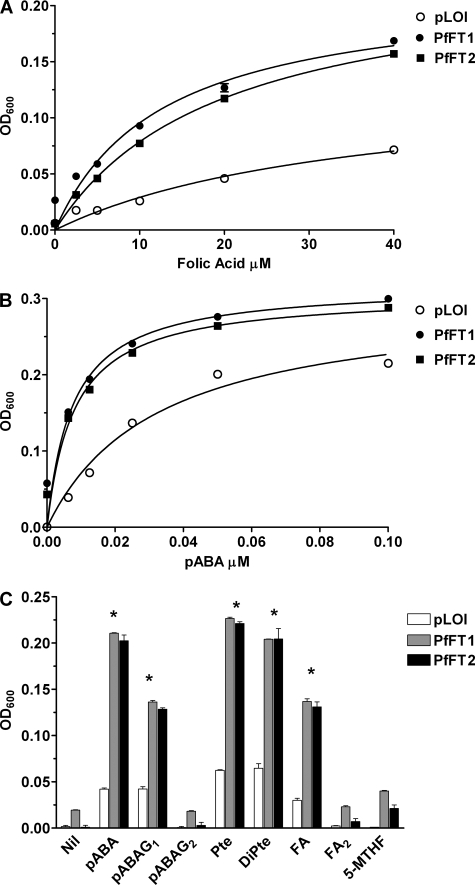

Fig. 6A shows the effect of increasing concentrations of exogenous FA on the growth of E. coli ΔpabA/ΔabgT expressing either PfFT1 or PfFT2 compared with the plasmid-only control pLOI707HE (abbreviated pLOI). The pLOI plasmid used as control had the bla locus (ampicillin-resistant) removed from the cloning site due to indications that it is detrimental and may cause a poor growth phenotype (30).

FIGURE 6.

Bacterial expression of PfFT1 and PfFT2. A, shown is growth in response to folic acid. The effect of folic acid (0–40 μm) on the growth of E. coli ΔpabA/ΔabgT-carrying recombinant constructs of the tac promoter plasmid pLOI707HE (32) with either PfFT1 or PfFT2 or the empty plasmid (pLOI was used as the control) was determined. If we accept a maximum growth effect at 40 μm, the folic acid-effective concentrations (EC50) for PfFT1 and PfFT2 were calculated as 10.95 ± 2.4 and 10 ± 2.0 μm, respectively. In the absence of the transporter, pLOI, folic acid-induced growth stimulation was significantly lower and linear across the concentration range compared with the E. coli-expressing PfFT1 and PfFT2. A600 on the y axis represents growth of the cultures based on the absorbance of the broth measured at 600 nm as under “Experimental Procedures.” Data taken from three different assays (n = 3) performed in triplicate. The differences in growth response to folic acid were significant (p < 0.001, two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post test) between bacteria carrying PfFT1 or PfFT2 and bacteria carrying the control plasmid pLOI at all FA concentrations. B, shown is growth in response to pABA. pABA (0–0.1 μm) stimulated the growth of the E. coli mutants with saturation occurring at around 0.1 μm. The maximum growth effect seen with pABA was achieved at 0.18 μm, and the EC50 values were 3.7 ± 0.4 and 3.1 ± 0.6 nm for PfFT1 and PfFT2, respectively. In the case of the empty plasmid (pLOI), the EC50was18 ± 2.4 nm. Differences between bacteria carrying PfFT1 or PfFT2 and the control plasmid pLOI were significant (p < 0.001, n = 3, data analysis as in A). C, growth response to folate precursors and derivatives is shown. pABA glutamated with one or two residues (pABAG1; pABAG2) was present at 20 nm final concentration. Pteroic acid-equivalent to folic acid without a glutamate (Pte), dihydropteroic acid (DiPte), and diglutamated folic acid (FA2) were present at 20 μm. Data are from triplicate observations with at least two experimental replicate assays (n = 2). Statistical analysis was performed with two-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni post-tests. The differences in growth between bacteria carrying PfFT1 or PfFT2 and bacteria carrying the control plasmid pLOI were significant for pABA, pABAG1, pteroic acid, dihydropteroic acid, and folic acid (p < 0.001) are denoted with an asterisk (*).

In each case growth of the E. coli knockouts expressing PfFT1 or PfFT2 was significantly increased relative to control across the range of FA concentrations. In this system FA is an effective rescue substrate in the low micromolar concentration range (Fig. 6A). These results confirm the observations with Xenopus oocytes that both PfFT1 and PfFT2 are capable of transporting FA (Table 1). Fig. 6B shows the effect of exogenous pABA on the growth of the same cell lines. Adding pABA to the medium significantly increased growth in the cell lines, including the control pLOI. Increased growth of the control could be due to a low level pABA transport activity of the E. coli ΔpabA/ΔabgT knock-out and/or a degree of passive diffusion of this weak acid. In any case, it is clear that growth is significantly increased relative to the control in the lines expressing PfFT1 or PfFT2. These results demonstrate that both PfFT1 and PfFT2 are capable of mediating the salvage of pABA, leading to growth rescue in the bacterial expression system at low nanomolar external concentrations.

Western blot analysis for PfFT2 to further corroborate its expression in E. coli ΔpabA/ΔabgT was performed on membrane-enriched fractions. However, these membrane preparations showed at best only very weak signals, and further immunoprecipitation using anti-PfFT2 was required. The immunoprecipitate generated with anti-PfFT2 shows a band of the expected size for PfFT2 (51.35 kDa) (supplemental Fig. S4) that is absent in the E. coli ΔpabA/ΔabgT mutant expressing the empty plasmid pLOI.

Fig. 6C summarizes the results of rescue experiments for a variety of folates and related compounds illustrating two major points; that is, the slower growth in the presence of polyglutamated forms (highly charged) of folate substrates or products and the lack of rescue by the naturally circulating folate in human plasma, 5-MTHF. Together with the dose-dependent rescue at nanomolar levels by pABA shown in Fig. 6B, these results confirm earlier observations with some cultured lines of P. falciparum that pABA is an efficient salvage substrate at low nanomolar external concentrations (11, 12). The monoglutamate derivative pABAG1 is also effective, although less efficient than pABA itself. An additional glutamate, as in pABAG2 completely ablates the growth rescue seen with pABA and pABAG1, suggesting that further glutamation reduces transport efficiency, as expected for a specific carrier-mediated membrane transporter. Importantly, our results suggest that both PfFT1 and PfFT2 may play a greater role in the salvage of the folate precursor pABA compared with preformed folates based on available circulating concentrations of the substrates expected in vivo.

Turning to the E. coli rescue with folate derivatives, the most effective folate derivative is pteroic acid (corresponds to folic acid without glutamate) both in its fully oxidized and dihydro forms (Fig. 6C) followed by FA (carries one glutamate). Again, the addition of more than one glutamate residue to the folate molecule completely ablates the rescue (Fig. 6C).

Most surprisingly, 5-MTHF is a very poor substrate in this system (Fig. 6C). As 5-MTHF is prone to oxidation, the levels of 5-MTHF in the bacterial culture media were measured by mass spectroscopy at the end of the growth assays (24 h) and compared with the initial 5-MTHF levels when the cultures were set up. After 24 h ∼90% of the initial 20 μm 5-MTHF remained intact (supplemental Fig. S5). Thus, at 18 μm this folate product was present in comparable concentrations to the other folate products tested. Thus, the modest effect by 5-MTHF in the bacterial assays was not due to its extracellular oxidation. E. coli is very capable of catalyzing the transfer of a methyl group from methyltetrahydrofolate to homocysteine to form methionine, a reaction that regenerates the tetrahydrofolate cofactor (55). The failure of external 5-MTHF to rescue these lines probably reflects inefficient transport of this substrate by the malarial transporters. These results mirror our findings with the transporters expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Fig. 3) and seem to suggest only a minimal role for the two transporters in the salvage of this, the most abundant preformed folate molecule in human serum.

Antagonism of Antifolate Drug Action in Vitro

The effects of adding micromolar concentrations of pABA, FA, FoA, or 5-MTHF on the antimalarial activity of antifolate drugs was assessed for the dihydropteroate synthase inhibitors dapsone and SDX and the DHFR inhibitors PYR and cycloguanil (supplemental Table S1). Four different P. falciparum isolates (HB3, 3D7, K1, and Dd2) with different dihydropteroate synthase and DHFR genotypes and sensitivities to antifolates were used. The growth inhibition assays were performed in media with low folate prepared using folate-free RPMI and serum extensively dialyzed to lower folate levels as has been common practice (5, 6, 14).

The antagonistic effects of pABA, FA, and FoA on the antimalarial activity of the antifolates are presented in supplemental Table S1. The degree of antagonism was dependent on the parasite isolate, the particular antifolate drug, and the specific folate supplement, as has been well documented elsewhere (e.g. Refs. 4–6, 14, 15, and 56). However, two critical observations substantiate the evidence compiled in the present study. First, pABA provides higher antagonism across the spectrum of antifolates and parasite strains studied. Second and in contrast, 5-MTHF tends to be the poorest antagonist.

pABA and folate antagonism were next more accurately assessed in P. falciparum 3D7 adapted to grow continuously in pABA and folate free medium. The concentrations of the folate derivatives used this time were within the reported concentration range for human serum (57): 150 nm pABA, 25 nm 5-MTHF, and 0.5 nm FA. The levels of 5-MTHF in culture media were confirmed by mass spectroscopy after 48 and 72 h, at points when the parasite growth was assessed. Because 5-MTHF was reduced to ∼88% of the initial levels by 48h (supplemental Fig. S5), the initial concentrations were adjusted to ensure that we would have 25 nm 5-MTHF present by the end of the parasite growth assays. Under these conditions the IC50 values for SDX and PYR in the absence of any folate supplementation were 26.15 ± 12.13 nm and 0.5 ± 0.05 pm, respectively. These values are 4 and 5 orders of magnitude lower than the sensitivity of the same parasites in the medium with low folate (Table 2). At their physiological concentrations neither 5-MTHF nor FA had any detectable effects on the sensitivity of the 3D7 strain to SDX or PYR (Tables 2 and 3). It is clear that 5-MTHF does not antagonize antifolates under physiological conditions, a finding that is all the more surprising because 5-MTHF is the most prevalent preformed folate in human serum (58). Crucially, these drug antagonism experiments closely parallel the findings of the transport and rescue experiments described above, which indicate that 5-MTHF is transported and salvaged only very poorly. This lack of antagonism by 5-MTHF has also been documented for the DHFR inhibitors pyrimethamine and chlorcycloguanil (59).

TABLE 2.

Effect of exogenous folate supplementation on the in vitro inhibitory activity of antifolates against P. falciparum 3D7 adapted to continuous culture in folate and pABA free media

IC50 values obtained from 3D7 parasites were cultured in either dialyzed media (folate-free RPMI-1640 and dialyzed serum) or “free” media (folate- and pABA-free RPMI-1640 and Albumax II). Folate supplements were present at the following concentrations: for dialyzed media, 7.3 μm pABA and 2.3 μm for both 5-MTHF and FA; for free media, 150 nm pABA, 25 nm 5-MTHF, and 0.5 nM FA. Values represent the mean ± S.D. and n = 4–7. In all comparisons between free and dialyzed media there was a statistical difference (p < 0.0001, t test), with the values observed with dialyzed media always higher than the folate-free media. pABA significantly antagonized antifolate activity under both sets of culture conditions for both SDX and PYR (p < 0.05), whereas 5-MTHF had no effect, and FA was only significant with SDX in dialyzed media (p < 0.05).

| Supplements | IC50 values |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDX |

PYR |

|||

| Dialyzed | Free | Dialyzed | Free | |

| μm | nm | nm | pm | |

| Control | 426.13±85.46 | 26.15±12.13 | 50.10±11 | 0.5±0.05 |

| pABA | 1952.33±189.98 | 572.43±145.36 | 90.2±12 | 41.86±3.11 |

| 5-MTHF | 472.25±42.11 | 23.28±15.29 | 70.3±09 | 0.39±0.06 |

| FA | 1572.06±413.66 | 33.15±22.23 | 100.4±30 | 0.36±0.06 |

TABLE 3.

The impact of probenecid on pABA or folate-induced antagonism of antifolate activity in P. falciparum in vitro

Values are shown for assays carried out in folate and pABA-free RPMI-1640 media containing Albumax II. Supplements were present at 150 nm pABA, 25 nm 5-MTHF, and 0.5 nm FA. PBN was present at 150 μm. Values are presented as the mean ± S.D. n = 5–6. Probenecid significantly reduced the impact of supplementation on antimalarial drug activity (p < 0.01).

| Supplements | IC50 values |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDX | SDX + PBN | PYR | PYR + PBN | |

| nm | pm | |||

| Control | 27.3±12.13 | 1.3±0.61 | 0.5±0.05 | 0.3±0.02 |

| pABA | 545±145 | 141±34 | 41.7±3.11 | 27.6±2.55 |

| 5-MTHF | 22.3±15.29 | 1.1±0.42 | 0.4±0.06 | 0.24±0.10 |

| FA | 31.7±22.23 | 1.5±0.35 | 0.35±0.06 | 0.22±0.03 |

| pABA + 5-MTHF + FA | 594±102 | 150±22 | 44.9±3.11 | 26.45±1.32 |

In contrast, the addition of pABA at physiological levels resulted in a significant antagonism of SDX (22-fold higher IC50) and PYR (83-fold higher IC50) activities (p ≤ 0.001, Tables 2 and 3). We also found that the effect of pABA was reduced by PBN; IC50 values for SDX and PYR supplemented with pABA were 4-fold and 2-fold lower, respectively, in the presence of concentrations of PBN used in previous chemosensitization studies (16) (Table 3). This is in agreement with the ability of this anion transport inhibitor to inhibit PfFT1- and PfFT2-driven folate uptake in oocytes. The data generated in these studies are internally consistent with pABA being a substrate with pharmacological impact at physiologically relevant concentrations for both transporters.

DISCUSSION

Malaria parasites are able to synthesize folate de novo, but there is no doubt that they are also capable of taking up and utilizing exogenous folate derivatives. Cultures of P. falciparum can take up exogenous folic acid, folinic acid, and pABA and convert it to polyglutamated folate end products (9, 12). Salvage and catabolism of exogenous 5-MTHF (using a concentration of 37 mm, 6 orders of magnitude higher than its physiological levels) has also been shown with its methyl group being incorporated into methionine and the remaining co-factor joining the folate pool in P. falciparum (7). Of the primary human folate catabolites, pABAG1 was shown to be an alternative substrate for malarial dihydropteroate synthetase, raising the possibility of salvage and direct utilization of pABAG1 in the parasite folate pathway (60). One critically important aspect of folate salvage is the mechanism by which folate derivatives are taken into the intracellular parasite. Exogenous folates and precursors must pass through the host erythrocyte membrane, the parasitophorous vacuole membrane, and the parasite plasma membrane en route to the parasite cytoplasm. The findings of a recent study suggest that it is unlikely that either the host erythrocyte membrane or the parasitophorous vacuole membrane provides a rate-limiting barrier to folate salvage in P. falciparum (13). In this study it was also shown that the uptake of folates across the parasite plasma membrane was regulated, saturable, inhibitable, and energy-dependent, thus exhibiting the properties of a carrier-mediated membrane transport process (13).

Here we have identified PfFT1 and PfFT2 and generated data to support their role as P. falciparum folate transporters. The predicted proteins display significant similarities to members of the high affinity BT1 folate transporter group (TC 2.A.71). Both PfFT1 and PfFT2 appear to be localized predominantly to the plasma membrane in intraerythrocytic P. falciparum (Fig. 2). Both the identified malarial transporters exhibit broad substrate specificity capable of transporting FA, FoA, 5-MTHF, pteroic acid, dihydropteroic acid, pABA, and pABAG1 (Table 1, Figs. 3–6). In this respect they are similar to plant members of the BT1 family that are assumed to be able to transport monoglutamyl forms of any naturally occurring folate (31). Here, both PfFT1 and PfFT2 are also capable of transporting the human folate catabolite pABAG1 (Fig. 6C), whereas other BT1 family members apparently do not transport this substrate (31). As pABAG1 is a product of folate catabolism in humans (61), circulating in plasma at estimated concentrations of 160 nm (62), the results presented here open the possibility of malaria parasites also being able to salvage products of host folate catabolism.

Our results indicate that pABA and pABAG1 are better salvage substrates compared with preformed folates. These findings are in agreement with an earlier study using intact parasite cultures showing that pABA was more efficiently taken up and converted to polyglutamated end products than were preformed folates (12). Furthermore, the conclusion that 5-MTHF is a poor salvage substrate is consistent with the very weak antagonism of antifolate antimalarial activities cause by 5-MTHF reported elsewhere (59).

Although P. falciparum has been shown to require a minimal amount of folate to survive long term in in vitro culture in the absence of pABA (i.e. 226.5 nm FA (51)), we have successfully cultured P. falciparum 3D7 continuously in the absence of pABA or folates. This allowed us to investigate the effects of very low concentrations of folates and pABA, representative of those encountered in the plasma of the human host. Under these physiologically relevant conditions only pABA caused any significant antagonism of antifolate activity (Tables 2 and 3).

It has proven technically difficult to demonstrate direct transport of pABA by PfFT1 and PfFT2. This difficulty has also been encountered with folate transport assays mediated via other BT1 transporters. The Xenopus oocyte system displayed a high background of pABA uptake at neutral pH (10 pmol/oocyte/h) that we have been unable to reduce. We moved to the bacterial system to overcome some of the limitations of the Xenopus model. However, as a vitamin, only very low levels of protein expression and low levels of substrate transport (in our case pABA and folates) are required to salvage the E. coli mutants. The concentrations involved are below the sensitivity of the analytical methods available. Other groups have explicitly reported their inability to express BT1 homologs (e.g. Synechocystis and Arabidopsis BT1 family of folate transporters) to levels suitable for kinetic studies despite considerable effort (30). In the absence of a direct method to measure folate transport activity within an acceptable time scale, we believe that E. coli rescue, as used here, is the most sensitive indirect system available by which PfFT1- and PfFT2-mediated pABA and folate salvage can be characterized.

In assessing the functional significance of our observations it seems relevant to consider the physiological levels of folate derivatives as they occur in human blood and plasma. The latest available data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys in the United States puts the median red cell folate levels of the United States population (4 years of age and older) at 266 ng/ml, whereas the median serum folate levels are 12.2 ng/ml or about 27 nm (57). A recent liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of folate and folate catabolites in human serum shows that in normal individuals about 98% of serum folate is in the form of 5-MTHF (or its primary oxidized derivative 4-α-hydroxy-5-methyltetrahydrofolate monoglutamate), and about 2% is in the form of FA (58). Thus, physiological concentrations of 5-MTHF and FA in human serum are ∼26.5 nm and 540 pm, respectively. When these concentrations of folates were added to folate-free culture media, we found no significant antagonism of antifolate drugs in cultures of P. falciparum 3D7 (Tables 2 and 3).

The physiological concentration of pABA in human serum is known to be highly variable. In a study of 90 serum samples from blood donors, approximately half of the cohort had serum pABA concentrations between 145 nm and 6.1 μm (63). If these figures reflect serum pABA concentrations in the general population, then our results and those of others suggest that the concentrations of serum pABA may be high enough to antagonize antifolate activity in a significant number of patients (4, 6).

Malaria parasites are capable of synthesizing pABA de novo via the shikimate pathway (10, 50). However, pABA synthesis does not seem to be sufficient for parasite survival in vivo; over many years, studies performed in rodents, monkeys, and humans have all shown that a pABA-deficient diet may help to protect the host from a variety of malaria species (8, 64–69). In this respect pABA salvage seems more important than the salvage of preformed folates. Because pABA is neither required nor synthesized by the human host, its salvage is potentially an attractive target for chemotherapy. For instance, the use of pABA-deficient diets or the use of inhibitors to block pABA salvage at the level of PfFT1 or PfFT2 may improve the antimalarial efficacy of several classes of antimalarial drugs including the antifolates and inhibitors of the shikimate pathway (3, 8).

In summary we report the identification and characterization of two transporters, PfFT1 and PfFT2, that mediate the salvage of folate derivatives and precursors in P. falciparum. We propose a new vision of folate salvage by the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite; folate salvage occurs via the import of pABA rather than preformed folates. This could explain why dihydropteroate synthase inhibitors retain their efficacy and synergy with DHFR inhibitors in the presence of physiological folate concentrations as well as presenting potential new opportunities for the development of antimalarial therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Larry H. Matherly (Wayne State University School of Medicine, Karmanos Cancer Institute) kindly provided the hRFC1 clone. LtFT1 was kindly provided by Marc Ouellette (Université Laval), and A. D. Hanson (Department of Horticultural Sciences, University of Florida) provided the E. coli pabAabgT double mutant and pLOI707HE plasmid vectors. We thank Abhishek Srivastava for assistance in the mass spectrometry and Roslaini Abd Majid for assistance with Western blots.

This work was supported by Medical Research Council Grant G0400173 (to P. G. B.), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Wellcome Trust (open access publishing grant).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5 and Table S1.

- pABA

- p-aminobenzoic acid

- pABAG1

- pABA monoglutamate

- pABAG2

- pABA diglutamate

- BT1

- biopterin and folate transporter family

- DHFR

- dihydrofolate reductase

- FA

- folic acid

- FoA

- folinic acid

- 5-MTHF

- 5-methyltetrahydrofolate

- PBN

- probenecid

- PYR

- pyrimethamine

- SDX

- sulfadoxine

- MFS

- major facilitator superfamily

- LtFT1

- L. tarentolae FT1

- pLOI

- pLOI707HE.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fox J. T., Stover P. J. (2008) in Folic Acid and Folates (Litwack G., ed.) pp 1–44, Academic Press, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gregson A., Plowe C. V. (2005) Pharmacol. Rev. 57, 117–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hyde J. E. (2005) Acta Trop. 94, 191–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tan-ariya P., Brockelman C. R. (1983) J. Parasitol. 69, 353–359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tan-ariya P., Brockelman C. R., Menabandhu C. (1987) Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 37, 42–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watkins W. M., Sixsmith D. G., Chulay J. D., Spencer H. C. (1985) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 14, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Asawamahasakda W., Yuthavong Y. (1993) Parasitology 107, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kicska G. A., Ting L. M., Schramm V. L., Kim K. (2003) J. Infect. Dis. 188, 1776–1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krungkrai J., Webster H. K., Yuthavong Y. (1989) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 32, 25–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McConkey G. A., Ittarat I., Meshnick S. R., McCutchan T. F. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 4244–4248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Milhous W. K., Weatherly N. F., Bowdre J. H., Desjardins R. E. (1985) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 27, 525–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang P., Nirmalan N., Wang Q., Sims P. F., Hyde J. E. (2004) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 135, 77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang P., Wang Q., Sims P. F., Hyde J. E. (2007) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 154, 40–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tan-Ariya P., Brockelman C. R. (1983) Exp. Parasitol. 55, 364–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang P., Brobey R. K., Horii T., Sims P. F., Hyde J. E. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 32, 1254–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nzila A., Mberu E., Bray P., Kokwaro G., Winstanley P., Marsh K., Ward S. (2003) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 2108–2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sowunmi A., Fehintola F. A., Adedeji A. A., Gbotosho G. O., Falade C. O., Tambo E., Fateye B. A., Happi T. C., Oduola A. M. J. (2004) Trop. Med. Int. Health 9, 606–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bray P. G., Mungthin M., Hastings I. M., Biagini G. A., Saidu D. K., Lakshmanan V., Johnson D. J., Hughes R. H., Stocks P. A., O'Neill P. M., Fidock D. A., Warhurst D. C., Ward S. A. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 62, 238–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trager W., Jensen J. B. (1976) Science 193, 673–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson J. D., Dennull R. A., Gerena L., Lopez-Sanchez M., Roncal N. E., Waters N. C. (2007) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 1926–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bahl A., Brunk B., Crabtree J., Fraunholz M. J., Gajria B., Grant G. R., Ginsburg H., Gupta D., Kissinger J. C., Labo P., Li L., Mailman M. D., Milgram A. J., Pearson D. S., Roos D. S., Schug J., Stoeckert C. J., Jr., Whetzel P. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 212–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Benson D. A., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Lipman D. J., Ostell J., Wheeler D. L. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D25–D30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beitz E. (2000) Bioinformatics 16, 135–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tusnády G. E., Simon I. (2001) Bioinformatics 17, 849–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beitz E. (2000) Bioinformatics 16, 1050–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deleted in proof [Google Scholar]

- 28. Virkki L. V., Cooper G. J., Boron W. F. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 281, R1994–R2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Subramanian V. S., Marchant J. S., Parker I., Said H. M. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 281, G1477–G1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eudes A., Kunji E. R., Noiriel A., Klaus S. M., Vickers T. J., Beverley S. M., Gregory J. F., 3rd, Hanson A. D. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 2867–2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Klaus S. M., Kunji E. R., Bozzo G. G., Noiriel A., de la Garza R. D., Basset G. J., Ravanel S., Rébeillé F., Gregory J. F., 3rd, Hanson A. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38457–38463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arfman N., Worrell V., Ingram L. O. (1992) J. Bacteriol. 174, 7370–7378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sambrook J., Rusell D. (2001) Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Ed., pp. A2.1–A2.12, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goldin A. L. (1992) Methods Enzymol. 207, 266–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maughan S. C., Pasternak M., Cairns N., Kiddle G., Brach T., Jarvis R., Haas F., Nieuwland J., Lim B., Müller C., Salcedo-Sora E., Kruse C., Orsel M., Hell R., Miller A. J., Bray P., Foyer C. H., Murray J. A., Meyer A. J., Cobbett C. S. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2331–2336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tonkin C. J., van Dooren G. G., Spurck T. P., Struck N. S., Good R. T., Handman E., Cowman A. F., McFadden G. I. (2004) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 137, 13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nkrumah L. J., Muhle R. A., Moura P. A., Ghosh P., Hatfull G. F., Jacobs W. R., Jr., Fidock D. A. (2006) Nat. Methods 3, 615–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pao S. S., Paulsen I. T., Saier M. H., Jr. (1998) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 1–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martin R. E., Henry R. I., Abbey J. L., Clements J. D., Kirk K. (2005) Genome Biol. 6, R26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saier M. H., Jr., Beatty J. T., Goffeau A., Harley K. T., Heijne W. H., Huang S. C., Jack D. L., Jähn P. S., Lew K., Liu J., Pao S. S., Paulsen I. T., Tseng T. T., Virk P. S. (1999) J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1, 257–279 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dridi L., Haimeur A., Ouellette M. (2010) Biochem. Pharmacol. 79, 30–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Qiu A., Jansen M., Sakaris A., Min S. H., Chattopadhyay S., Tsai E., Sandoval C., Zhao R., Akabas M. H., Goldman I. D. (2006) Cell 127, 917–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lasry I., Berman B., Straussberg R., Sofer Y., Bessler H., Sharkia M., Glaser F., Jansen G., Drori S., Assaraf Y. G. (2008) Blood 112, 2055–2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhao R., Min S. H., Qiu A., Sakaris A., Goldberg G. L., Sandoval C., Malatack J. J., Rosenblatt D. S., Goldman I. D. (2007) Blood 110, 1147–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huang Y., Lemieux M. J., Song J., Auer M., Wang D. N. (2003) Science 301, 616–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yuvaniyama J., Chitnumsub P., Kamchonwongpaisan S., Vanichtanankul J., Sirawaraporn W., Taylor P., Walkinshaw M. D., Yuthavong Y. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 357–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Inoue K., Nakai Y., Ueda S., Kamigaso S., Ohta K. Y., Hatakeyama M., Hayashi Y., Otagiri M., Yuasa H. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 294, G660–G668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lo R. S., Said H. M., Unger T. F., Hollander D., Miledi R. (1991) Proc. Biol. Sci. 246, 161–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wong S. C., Proefke S. A., Bhushan A., Matherly L. H. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17468–17475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roberts F., Roberts CW, Johnson JJ, Kyle DE, Krell T, Coggins JR, Coombs GH, Milhous WK, Tzipori S, Ferguson DJ, Chakrabarti D, McLeod R. (1998) Nature 393, 801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang P., Sims P. F., Hyde J. E. (1997) Parasitology 115, 223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Waterkeyn J. G., Crabb B. S., Cowman A. F. (1999) Int. J. Parasitol. 29, 945–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hussein M. J., Green J. M., Nichols B. P. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 6260–6268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Carter E. L., Jager L., Gardner L., Hall C. C., Willis S., Green J. M. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189, 3329–3334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hondorp E. R., Matthews R. G. (2009) J. Bacteriol. 191, 3407–3410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brockelman C. R., Tan-ariya P. (1982) Bull. W.H.O. 60, 423–426 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McDowell M. A., Lacher D. A., Pfeiffer C. M., Mulinare J., Picciano M. F., Rader J. I., Yetley E. A., Kennedy-Stephenson J., Johnson C. L. (2008) NCHS Data Brief 6, 1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hannisdal R., Ueland P. M., Svardal A. (2009) Clin. Chem. 55, 1147–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nduati E., Diriye A., Ommeh S., Mwai L., Kiara S., Masseno V., Kokwaro G., Nzila A. (2008) Parasitol. Res. 102, 1227–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ferone R. (1973) J. Protozool. 20, 459–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suh J. R., Herbig A. K., Stover P. J. (2001) Annu. Rev. Nutr. 21, 255–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lin Y., Dueker S. R., Follett J. R., Fadel J. G., Arjomand A., Schneider P. D., Miller J. W., Green R., Buchholz B. A., Vogel J. S., Phair R. D., Clifford A. J. (2004) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80, 680–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schapira A., Bygbjerg I. C., Jepsen S., Flachs H., Bentzon M. W. (1986) Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 35, 239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bray R. S., Garnham P. C. (1953) Br. Med. J. 1, 1200–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hawking F. (1954) Br. Med. J. 1, 425–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kretschmar W. (1966) Z. Tropenmed. Parasitol. 17, 301–320 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kretschmar W. (1966) Z. Tropenmed. Parasitol. 17, 369–374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kretschmar W. (1966) Z. Tropenmed. Parasitol. 17, 375–390 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Maegraith B. G., Deegan T., Jones E. S. (1952) Br. Med. J. 2, 1382–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Richard D., Leprohon P., Drummelsmith J., Ouellette M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54494–54501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.