Background: The A580V human pIgR polymorphism is associated with IgA nephropathy and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Results: A580V mutation reduces pIgR/pIgA transcytosis and seemingly pIgR cleavage and release from the apical surface.

Conclusion: The A580V polymorphism regulates pIgR and IgA-pIgR complex transcytosis across cells.

Significance: Defects in pIgR trafficking and processing may underlie the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Keywords: Cancer, Cell Surface Receptor, Kidney, Membrane Transport, Mutagenesis Site-specific, Transcytosis, IgA Nephropathy, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, pIgA, pIgR Mutation

Abstract

Polymeric IgA (pIgA) is transcytosed by the pIgA receptor (pIgR) across mucosal epithelial cells. After transcytosis to the apical surface, the extracellular, ligand-binding portion of the pIgR is proteolytically cleaved. A missense mutation in human pIgR, A580V, is associated with IgA nephropathy and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. We report that this mutation reduces the rate of transcytosis of pIgR and pIgA, and seemingly the rate of pIgR cleavage. We propose that the defects in pIgR trafficking caused by the A580V mutation may underlie the pathogenesis of both diseases.

Introduction

The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR)5 is a single-spanning transmembrane protein expressed on many epithelial cells lining mucosal surfaces (1–3). At the basolateral (BL) cell surface, the pIgR binds its ligand, polymeric IgA (pIgA). The pIgA can in turn be bound to its antigen. The pIgR-pIgA complex is endocytosed and transcytosed through a series of endocytic vesicles to the apical (AP) surface. There, the extracellular, ligand binding domain of pIgR is proteolytically cleaved and released together with the pIgA into external secretions. This cleaved fragment of pIgR is termed secretory component (SC).

A missense mutation (pIgR-A580V) in the extracellular region of human pIgR is associated with increased risk of IgA nephropathy (IgAN) in Japan (4). IgAN is the main cause of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide, especially in east Asia; 20–40% of patients progress to end stage renal failure (5). The pIgR-A580V mutation has also been associated in two studies with increased risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) in Thai and southern Chinese populations, where NPC is a leading form of cancer (6–8). This result is intriguing, because Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the causative agent of NPC, can enter epithelial cells via binding to the pIgR of pIgA antibodies directed against EBV (9, 10).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids, Viral Production and Transduction, and Cell Culture

Human pIgR in pcDNA3.1 was kindly provided by C. Kaetzel (University of Kentucky). The A580V point mutation was made by QuikChange mutagenesis (Stratagene). pIgR (WT and A580V) coding sequence was transferred to pLZRS-MS/IRES-GFP retroviral vector (A. Reynolds, Vanderbilt University), giving expression of hpIgR and GFP under IRES control. Viral production and transduction were performed as described (11), with some modifications. pLZRS vectors were transfected into 293-GPG packaging cells (O. Weiner, University of California San Francisco). The following day, fresh medium was added, and viral supernatants collected 3 days after transfection. For retrovirus transduction, subconfluent Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells 16–24 h after plating were incubated with virus-containing supernatants for 48 h at 37 °C. Stable lines were made using two complementary procedures: (i) direct transfection of pcDNA3.1-pIgR followed by antibiotic-mediated selection (0.5 mg/ml G418 for 2–3 weeks) and screening for hpIgR-positive clones, or (ii) viral transduction (see below) using pLZRS-MS/IRES-GFP-pIgR (WT and A580V) followed by FACS to enrich for pools of GFP-expressing cells. All assays were verified using cell lines made by both methods, ensuring differences noted were due to the A580V pIgR mutation and not clonal variation. pIgR-expressing MDCK cells were grown as described (11, 12), on 12 or 24 mm polycarbonate Transwell filters (Corning) for 3–4 days for all experiments.

pIgR Transcytosis Assay by BL Biotinylation

Biotinylation was performed at 17 °C (11, 12). Cells (on 12-mm filters) were washed three times with Hanks' balanced saline solution (HBSS) containing 20 mm HEPES and biotinylated basolaterally with 0.5 mg/ml LC-NHS-biotin (Pierce) in HBSS for 30 min; 500 μl of MEM with 0.6% BSA (w/v), 20 mm HEPES, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (MEM/BSA/HEPES) was added to the AP side. Cells were washed with MEM/BSA/HEPES buffer three times for 20 min at 17 °C to remove excess biotin. Transwells were transferred to 150-μl drops of MEM/BSA/HEPES ± pIgA (0.3 mg/ml) in a humid box for 10 min at 17 °C (with 250 μl of MEM/BSA/HEPES on the AP side). Cells were then transferred to a 37 °C water bath. Another 250 μl of 37 °C MEM/BSA/HEPES buffer was added to the AP chamber of filters to change the temperature to 37 °C. After the chase, 350 μl of cold MEM was added to the BL side, and filters were placed onto an ice-cold metal plate. AP medium was collected, and cells were lysed in 500 μl of 0.5% SDS (w/v) lysis buffer containing 100 mm NaCl, 50 mm triethanolamine HCl, pH 8.6, 5 mm EDTA HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2% Trasylol (v/v), 0.02% NaN3 (w/v). Samples were boiled for 10 min and vortexed for 15 min at room temperature. Samples were then precleared with Sepharose CL2B beads, and 500 μl 2.5% (v/v) Triton dilution buffer containing 100 mm NaCl, 100 mm triethanolamine HCl, pH 8.6, 5 mm EDTA HCl, pH 8.0, 1.0% Trasylol (v/v), 0.02% NaN3 (w/v) was added before immunoprecipitation with 30 μl of protein G beads (and 1 μg/sample of rabbit anti-human SC antibody (Dako and Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitated samples were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and Western blotting using IRD800-streptavidin. Protein bands (Pierce) were visualized by LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey NIR Imager scanner.

pIgA Transcytosis by ELISA Analysis

Cells on a 12-mm filter were treated with 100 μg/ml biotinylated pIgA (biotinylation procedure was based on the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce) from the BL surface at 37 °C for 20, 40, and 80 min (11). AP media were collected, and cells were lysed in 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (v/v) lysis buffer containing 125 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES, 4 mm MgCl2, and protease inhibitors mixture. The amount of biotinylated pIgA, collected from either the AP medium after transcytosis or remaining in cells, was measured by ELISA. In brief, streptavidin-coated 96-well plates were blocked with 2% BSA in PBS. Samples collected at indicated time points were diluted in 2% BSA/PBS/T (0.5% Tween 20 v/v) and preincubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Wells were first treated with mouse anti-biotin antibody (1:5,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 2 h at 37 °C and then with HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at 37 °C. 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramentylbenzidine substrate (Pierce) was used for detection. Plates were scanned by EMax precision microplate reader (Molecular Devices), and data were analyzed by Softmax software and exported to Excel for statistical analysis.

pIgA-pIgR AP Endocytosis by pIgA Binding

Cells grown on 12-mm Transwells were washed twice with cold MEM and incubated with biotinylated pIgA at 4 °C on ice for 2 h. Cells were washed six times with cold MEM/BSA/HEPES buffer for 5 min each cycle. Filters were placed in a prewarmed dish with medium, and 150 μl/filter prewarmed MEM/BSA/HEPES buffer was added to the AP chamber of filters at 37 °C for 2, 5, 10, and 30 min. Media samples were collected. Monolayers were treated with trypsin- tosylphenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (100 μg/ml) (Worthington Biochemical) apically and with soybean trypsin inhibitor at the BL side at 4 °C for 1 h. Trypsin was then quenched with 10% horse serum in MEM, and cells were lysed in 0.5% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer. Control cells remained on ice without protease before lysis. All samples were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting for pIgR and biotinylated pIgA.

pIgR AP Cleavage by AP Biotinylation

Cells grown on 24-mm Transwells were washed with ice-cold HBSS and biotinylated with 0.5 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin in HBSS twice for 15 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed with ice-cold MEM/BSA/HEPES buffer five times for 30 min. To start cleavage, prewarmed MEM/BSA/HEPES buffer was added to the AP chamber, and cells were incubated for 5 min in a water bath at 37 °C. At the completion of each time point, corresponding filters were transferred to a dish with medium at 4 °C on ice, and media samples were collected from the AP chamber. Monolayers were washed and lysed in 0.5% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer at 4 °C on ice. Cleaved SC and uncleaved endocytosed pIgRs were detected by immunoprecipitation of pIgR using rabbit anti-human pIgR, then immunoblotted for biotinylated SC and pIgR with mouse anti-biotin antibodies (LI-COR Odyssey). Cleavage levels of pIgR were calculated as the fraction of AP media SC, expressed as a percentage of the total pIgR levels (AP SC + intracellular pIgR).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. Student's t test was utilized to compare differences between wild-type and mutant cells. p and n values are presented in the figure legends.

RESULTS

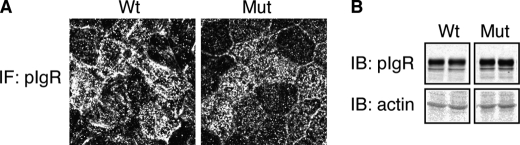

To investigate how the pIgR-A580V mutation can underlie both IgAN and NPC, we expressed wild-type human pIgR (pIgR-WT) and pIgR-A580V in polarized MDCK cells, which have been used extensively for studies of pIgR trafficking (13). Both pIgR-WT and pIgR-A580V were uniformly expressed at similar levels (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

pIgR-WT and pIgR-A580V expression in MDCK cells. A, similar expression level of pIgR is shown in pIgR-WT and pIgR-A580V cells by immunofluorescent (IF) staining. B, immunoblot (IB) shows duplicate pIgR-WT- and pIgR-A580V-expressing MDCK samples, with actin as a loading control, showing equivalent WT and A580V expression. Cropped boxes represent different bands from the same gel and exposure.

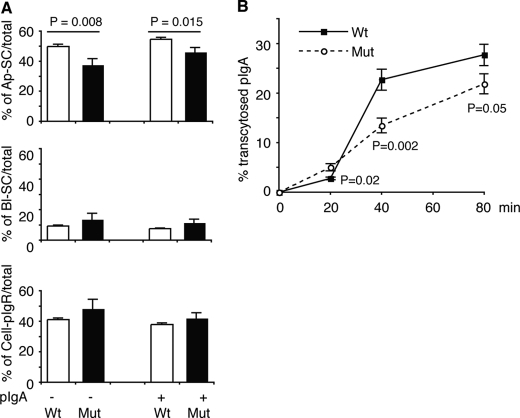

We measured transcytosis of pIgR by biotinylating it at the BL surface and quantitating the subsequent release of biotin-SC into the AP medium in the absence or presence of pIgA. AP SC release was reduced from 49.81 ± 1.47% (pIgR-WT) to 37.84 ± 3.79% (pIgR-A580V), p = 0.008 in the absence of pIgA (Fig. 2A, top).

FIGURE 2.

A580V mutation in human pIgR decreases pIgR/pIgA transcytosis in pIgR-expressing MDCK cells. A, pIgR/pIgA transcytosis was significantly decreased in pIgR-A580V-expressing cells, compared with pIgR-WT. Cells were basolaterally labeled with biotin at 17 °C for 30 min and washed at 17 °C for 30 min. Cells were then chased with MEM/BSA at 37 °C for 60 min. Top, apically released SC (Ap-SC) is expressed as a percentage of total labeled pIgR in all fractions (i.e. SC in AP and BL media, and pIgR). Middle, basolaterally released SC (BL-SC) is expressed as a percentage of total labeled pIgR in all fractions. Bottom, pIgR remaining in the cells is expressed as a percentage of total pIgR in all fractions. More AP-SC is seen in the pIgR-WT-expressing cells than for pIgR-A580V (n = 12). B, transcytosis of biotinylated pIgA was also significantly decreased in pIgR-A580V-expressing cells compared with pIgR-WT after 40 and 80 min of transcytosis (n = 14).

Binding of pIgA to the pIgR is known to increase the rate of transcytosis of the pIgR. We therefore determined the effect of the mutation on AP SC release in the presence of pIgA added to the BL medium. Under this condition, AP SC release was also decreased by the mutation, i.e. 54.6 ± 1.29% (pIgR-WT) and 46.32 ± 2.79% (pIgR-A580V), p = 0.015 (Fig. 2A, top). The small amount of SC released into the BL medium was not significantly changed (Fig. 2A, middle), and similarly the amount of pIgR remaining associated with the cells was not significantly altered (Fig. 2A, bottom).

Next, we followed the transcytosis of the ligand, biotinylated pIgA, which was exposed to the cells via the BL medium. AP medium was collected at several time points and transcytosed pIgA quantitated. Transcytosis was significantly decreased in pIgR-A580V cells at 40 min (22.69 ± 2.14% (WT) versus 13.45 ± 1.47% (A580V), p = 0.002) and 80 min (27.71 ± 2.15% (WT) versus 21.85 ± 2.01% (A580V), p = 0.05) (Fig. 2B). A small increase in transcytosed pIgA occurred in pIgR-A580V cells at 20 min, although the total amount of transcytosis at this earliest time point was very small. Taken together, these data reveal decreased overall IgA-transcytosis in cells expressing pIgR-A580V.

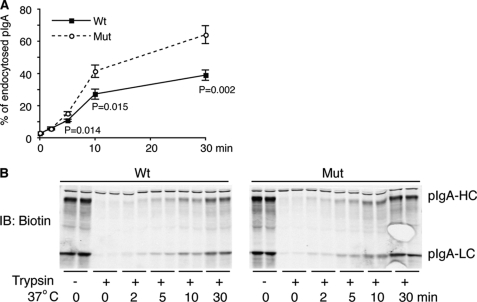

When the pIgR reaches the AP surface, it is not instantaneously cleaved to SC. Some uncleaved pIgR can bind pIgA at the AP surface, and the complex can then be endocytosed. To measure AP endocytosis, we bound pIgA to pIgR at the AP surface at 4 °C and then warmed cells to 37 °C for various times before cooling back to 4 °C. Internalized pIgA was then measured by acquisition of protease resistance. pIgA internalization was significantly increased in pIgR-A580V-expressing MDCK cells compared with pIgR-WT-expressing cells (Fig. 3). The endocytosis of WT versus mutant, respectively, was 10.84 ± 0.72% versus 15.2 ± 1.05% at 5 min, p = 0.014; 27.13 ± 3.13% versus 41.78 ± 3.82% at 10 min, p = 0.015; and 38.93 ± 3.18% versus 64.13 ± 5.61% at 30 min, p = 0.002.

FIGURE 3.

A580V mutation in human pIgR increases pIgA endocytosis in pIgR-expressing MDCK cells. A, filter-grown pIgR-WT- and pIgR-A580V-expressing cells were treated apically with biotinylated pIgA at 4 °C. Cells were warmed to 37 °C for the indicated period to allow pIgR-pIgA internalization. Finally, cells were cooled to 4 °C, and internalized pIgA levels were determined by resistance to exogenous protease addition. AP endocytosis is expressed as a percentage of total labeled pIgA. AP pIgA endocytosis rates were increased significantly in plgR-A580V-expressing cells compared with plgR-WT from 5 to 30 min (n = 4 at 5 min, n = 6 at 10 and 30 min). B, representative Western blotting (IB) image from A. Samples with equal amount of protein were blotted for biotinylated pIgA shown as pIgA-HC (heavy chain) and pIgA-LC (light chain). Cropped boxes represent different bands from the same gel and exposure.

The N-terminal, extracellular region of pIgR consists of five immunoglobulin-like domains, which become SC after proteolytic cleavage. This is connected by a stalk region to the single membrane-spanning segment of pIgR. The exact site(s) of the cleavage that converts pIgR to SC has not been definitively determined (14, 15). The Ala-580 mutation is in the stalk region of pIgR and close to the likely cleavage site(s). It is possible that the pIgR-580V mutation decreases the rate of cleavage of pIgR at the AP surface. Our measurement of pIgR transcytosis scores release of SC into the AP medium, and so a decrease in cleavage would decrease the apparent rate of transcytosis. The same holds true for measurement of transcytosis of pIgA bound to the pIgR. Furthermore, decreased cleavage could increase the amount of pIgR that enters the AP endocytic pathway rather than undergoing cleavage and thereby increase the apparent rate of endocytosis.

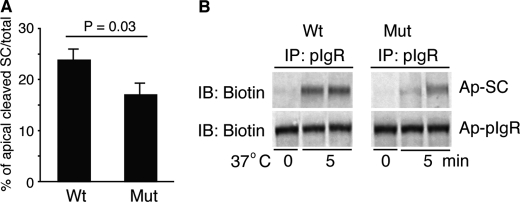

To measure pIgR cleavage directly, we biotinylated pIgR at the AP surface at 4 °C and then warmed the cells to 37 °C for 5 min and quantitated the release of biotinylated SC. Indeed, the rate of cleavage of pIgR to SC was decreased by the pIgR-A580V mutation. Cleavage of WT versus A580V, respectively, was 24.03 ± 0.94% versus 17.26 ± 0.61%, p = 0.03 (Fig. 4). This suggests that the reduction in pIgR-A580V transcytosis is likely due to reduced cleavage (13, 16, 17).

FIGURE 4.

A580V mutation in human pIgR decreases pIgR AP cleavage in pIgR-expressing MDCK cells. A, filter-grown pIgR cells were apically biotinylated at 4 °C. Samples were precipitated by rabbit anti-human pIgR antibodies and then blotted for biotinylated SC and pIgR. AP pIgR cleavage (presented as a percentage of total AP-labeled pIgR) was measured at 5 min at 37 °C. A decrease in pIgR-A580V cleavage over pIgR-WT occurred (n = 8). B, representative Western blotting (IB) image from A is shown. Cropped boxes represent different bands from the same gel and exposure.

DISCUSSION

The pIgR has been studied extensively as a model for membrane trafficking and transcytosis in polarized epithelial cells. Its 103-residue cytoplasmic domain contains sorting signals for BL delivery, endocytosis, avoidance of degradation, and transcytosis (13, 16). The pIgR is also a signaling receptor in that binding of the pIgA ligand to the pIgR leads to activation of a signaling network involving the Src family kinase Yes, EGFR, ERK, FIP5, rab3b, retromer, phospholipase Cγ1, and increased intracellular free calcium (2, 11). All of these processes involve the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the pIgR. In contrast, the pIgR-A580V mutation is located in the extracellular region of the pIgR. In particular, this mutation is in the membrane proximal “stalk” region of the pIgR where proteolytic cleavage of SC occurs. Indeed, the mutation likely reduces this cleavage, which probably accounts for the observed decreased rates of transcytosis of pIgR and pIgA, as well as the increased AP endocytosis of pIgA.

Our data do not exclude the possibility that the mutation might instead alter the conformation of the pIgR in a way that increases AP endocytosis. As cleavage probably occurs at the AP surface, this increased endocytosis could cause a decrease in the apparent rate of cleavage of the pIgR, thereby accounting for all of our data. However, given the proximity of the mutation to the cleavage site on the pIgR, we tend to favor the explanation that the mutation directly reduces the rate of cleavage.

IgAN and NPC are both complex, poorly understood diseases. Many genetic and environmental risk factors are likely to be involved and may account for the different outcomes (IgAN versus NPC) in different populations. IgAN is characterized by mesangial deposits of IgA (mainly polymeric), often complexed with antigen. Several loci have been identified with IgAN in a genome-wide association study (18). Another factor is altered galactosylation of IgA1 (5). IgAN is likely a heterogeneous group of diseases, and pIgR-A580V may play a role only in select populations, such as in Japan. We have shown that the pIgR A580V mutation results in a decrease in AP SC release and suggest that this is an additional factor contributing to both diseases. IgAN often follows mucosal infections, which cause increased production of pIgA and pIgA-antigen complexes. Ordinarily, such pIgA-antigen complexes are efficiently excreted into mucosal secretions by pIgR (1). The reduced efficiency of transcytosis by pIgR-A580V could lead to buildup of pIgA-antigen complexes, which would then be filtered out in the kidney, resulting in IgAN (20). Although the effect of pIgR-A580V on transcytosis is modest (but statistically significant), this could be sufficient to account for a slow accumulation of pIgA-antigen complexes, consistent with the multiyear time course of IgAN.

EBV is associated with infection and cancer in lymphocytes, e.g. Burkitt lymphoma, as well as NPC, an epithelial carcinoma (19). Complexes of pIgA bound to a surface protein of EBV are efficiently transcytosed across pIgR-expressing hepatocytes and polarized MDCK cells without causing EBV infection (9). However, nonpolarized pIgR-expressing HT29 human colon carcinoma cells are infected by EBV, which enters the cells via pIgA-EBV complexes bound to pIgR. We suggest that the reduced efficiency of transcytosis of EBV by pIgR-A580V could lead to infection, even in otherwise well polarized epithelial cells. Oncogenic transformation of one cell by EBV may be sufficient to result in NPC. It is thus possible that even a slight increase in the rate of infection of epithelial cells expressing the mutant pIgR could lead to clinical NPC. Therefore, the modest decrease in transcytosis caused by pIgR-A580V could be sufficient to account for the association of this mutation with NPC.

Our results provide a unified model of how a slowing in cleavage of pIgR by a missense mutation and the resultant decreased transcytosis of pIgA may contribute to two distinct diseases, IgAN and NPC, in vulnerable populations. This provides potentially important clues in both understanding the pathogenesis of these diseases and perhaps how they might be better diagnosed, prevented, or treated.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratory for discussions. We thank C. Kaetzel for human pIgR cDNA.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01AI25144 (to K. E. M.).

- pIgR

- polymeric immunoglobulin receptor

- AP

- apical

- BL

- basolateral

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced saline solution

- IgAN

- IgA nephropathy

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney

- MEM

- minimum essential medium

- NPC

- nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- pIgA

- polymeric IgA

- SC

- secretory component.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kaetzel C. S. (2005) Immunol. Rev. 206, 83–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rojas R., Apodaca G. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 944–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johansen F. E., Kaetzel C. S. (2011) Mucosal Immunol. 4, 598–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Obara W., Iida A., Suzuki Y., Tanaka T., Akiyama F., Maeda S., Ohnishi Y., Yamada R., Tsunoda T., Takei T., Ito K., Honda K., Uchida K., Tsuchiya K., Yumura W., Ujiie T., Nagane Y., Nitta K., Miyano S., Narita I., Gejyo F., Nihei H., Fujioka T., Nakamura Y. (2003) J. Hum. Genet. 48, 293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiryluk K., Julian B. A., Wyatt R. J., Scolari F., Zhang H., Novak J., Gharavi A. G. (2010) Pediatr. Nephrol. 25, 2257–2268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fan Q., Jia W. H., Zhang R. H., Yu X. J., Chen L. Z., Feng Q. S., Zeng Y. X. (2005) Ai Zheng 24, 915–918 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang E. T., Adami H. O. (2006) Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 1765–1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hirunsatit R., Kongruttanachok N., Shotelersuk K., Supiyaphun P., Voravud N., Sakuntabhai A., Mutirangura A. (2003) BMC Genet. 4, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gan Y. J., Chodosh J., Morgan A., Sixbey J. W. (1997) J. Virol. 71, 519–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sixbey J. W., Yao Q. Y. (1992) Science 255, 1578–1580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Su T., Bryant D. M., Luton F., Verges M., Ulrich S. M., Hansen K. C., Datta A., Eastburn D. J., Burlingame A. L., Shokat K. M., Mostov K. E. (2010) Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 1143–1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Song W., Bomsel M., Casanova J., Vaerman J. P., Mostov K. E. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 163–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mostov K., Su T., ter Beest M. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 287–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eiffert H., Quentin E., Decker J., Hillemeir S., Hufschmidt M., Klingmüller D., Weber M. H., Hilschmann N. (1984) Hoppe-Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 365, 1489–1495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughes G. J., Frutiger S., Savoy L. A., Reason A. J., Morris H. R., Jaton J. C. (1997) FEBS Lett. 410, 443–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luton F., Hexham M. J., Zhang M., Mostov K. E. (2009) Traffic 10, 1128–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weisz O. A., Rodriguez-Boulan E. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 4253–4266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gharavi A. G., Kiryluk K., Choi M., Li Y., Hou P., Xie J., Sanna-Cherchi S., Men C. J., Julian B. A., Wyatt R. J., Novak J., He J. C., Wang H., Lv J., Zhu L., Wang W., Wang Z., Yasuno K., Gunel M., Mane S., Umlauf S., Tikhonova I., Beerman I., Savoldi S., Magistroni R., Ghiggeri G. M., Bodria M., Lugani F., Ravani P., Ponticelli C., Allegri L., Boscutti G., Frasca G., Amore A., Peruzzi L., Coppo R., Izzi C., Viola B. F., Prati E., Salvadori M., Mignani R., Gesualdo L., Bertinetto F., Mesiano P., Amoroso A., Scolari F., Chen N., Zhang H., Lifton R. P. (2011) Nat. Genet. 43, 321–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hutt-Fletcher L. M. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 7825–7832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Emancipator S. N., Lamm M. E. (1989) Lab. Invest. 60, 168–183 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]