Background: ATP, PI3K, and p38 MAPK signaling is implicated in the recruitment of immune cells.

Results: Macrophages did not migrate toward ATPγS (ATP analog) but migrated to C5a independent of PI3K and p38 MAPK.

Conclusion: ATP does not recruit macrophages but locally induces lamellipodial membrane extensions.

Significance: ATP can promote chemotaxis and phagocytosis via autocrine/paracrine signaling but itself is not a chemoattractant.

Keywords: Akt, ATP, Cell Migration, Chemotaxis, p38 MAPK, Purinergic Agonists, Purinergic Receptor, Signal Transduction

Abstract

Adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) has been implicated in the recruitment of professional phagocytes (neutrophils and macrophages) to sites of infection and tissue injury in two distinct ways. First, ATP itself is thought to be a chemotactic “find me” signal released by dying cells, and second, autocrine ATP signaling is implicated as an amplifier mechanism for chemotactic navigation to end-target chemoattractants, such as complement C5a. Here we show using real-time chemotaxis assays that mouse peritoneal macrophages do not directionally migrate to stable analogs of ATP (adenosine-5′-(γ-thio)-triphosphate (ATPγS)) or its hydrolysis product ADP (adenosine-5′-(β-thio)-diphosphate (ADPβS)). HPLC revealed that these synthetic P2Y2 (ATPγS) and P2Y12 (ADPβS) receptor ligands were in fact slowly degraded. We also found that ATPγS, but not ADPβS, promoted chemokinesis (increased random migration). Furthermore, we found that photorelease of ATP or ADP induced lamellipodial membrane extensions. At the cell signaling level, C5a, but not ATPγS, activated Akt, whereas both ligands induced p38 MAPK activation. p38 MAPK and Akt activation are strongly implicated in neutrophil chemotaxis. However, we found that inhibitors of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K; upstream of Akt) and p38 MAPK (or conditional deletion of p38α MAPK) did not impair macrophage chemotactic efficiency or migration velocity. Our results suggest that PI3K and p38 MAPK are redundant for macrophage chemotaxis and that purinergic P2Y2 and P2Y12 receptor ligands are not chemotactic. We propose that ATP signaling is strictly autocrine or paracrine and that ATP and ADP may act as short-range “touch me” (rather than long-range find me) signals to promote phagocytic clearance via cell spreading.

Introduction

Both inside and outside of cells, ATP is a highly multifunctional molecule (1, 2). For example, inside innate immune cells, ATP is indispensable for the signal transduction cascades, myosin-dependent contractions, and F-actin polymerizations driving phagocytosis and cell motility. Outside of cells, ATP is an important extracellular signal molecule. How ATP gets out of cells is not well understood, and the various mechanisms of ATP release have recently been reviewed (1, 3). Most, if not all, cells express surface purinergic receptors, which are divided into G protein-coupled P2Y receptors and ATP-gated P2X ion channels (P2X1–7). In mouse, members of the P2Y receptor family are selectively activated by ATP and UTP (P2Y2 and P2Y4), ADP (P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13), UDP (P2Y6), or UDP-glucose (P2Y14). In addition to P2 receptors, there is a P1 family of G protein-coupled adenosine (A1, A2a, A2b and A3) receptors.

ATP released from damaged and dying cells is thought to act as a “tissue damage” (4), “danger” (5, 6), or “find me” (7) signal. As a find me signal, ATP released from apoptotic cells has been proposed to create an ATP gradient that attracts phagocytes (neutrophils and macrophages) via the P2Y2 receptor (7). However, outside of cells, ATP is rapidly degraded by a family of ectonucleotidases (8, 9), which catalyze the following hydrolysis steps: ATP → ADP → AMP → adenosine. This would limit the reach of ATP as a potential chemoattractant. Indeed, the half-life of extracellularly released ATP is measured in seconds (10, 11). Aside from its putative find me role (7), the P2Y2 receptor has also been implicated in autocrine purinergic signaling and gradient sensing by neutrophils and macrophages. Specifically, ATP release induced by chemoattractants and autocrine feedback via P2Y2 or other P2 receptor subtypes were shown to be involved in chemotactic navigation (12, 13).

Although ATP itself is thought to be a chemoattractant, the picture is not clear if one takes a closer look at the literature. Local tissue injury or high concentrations of ATP (or ATPγS)2 in a patch pipette have been clearly shown in vivo to induce the convergence of processes from microglia (brain-resident macrophages), although without translocation of the cell body (14, 15). Cultured microglia were also found to migrate toward ATP in a 0–50 μm gradient in a Dunn chamber (16). The effect was absent in P2Y12−/− microglia, which is unexpected because P2Y12 is an ADP-selective receptor. Degradation of ATP to ADP could explain the apparent P2Y12 dependence of ATP-induced chemotaxis. In any case, it is difficult to draw definite conclusions on gradient sensing and directed migration because the cells only moved 1–2 cell widths during the short (30-min) analysis period and P2Y12−/− microglia did not move at all. In Transwell assays, THP-1 monocytes and mast cells were found to migrate toward ATP and other nucleotides (17). However, classical Boyden-like Transwell assays do not allow clear distinction between chemokinesis and chemotaxis (18). For example, Chen et al. (12) found that ATPγS promoted transwell migration of HL-60 cells regardless of whether it added to the upper or lower well, implying that it induces chemokinesis but not chemotaxis. Similarly, using the same approach, ATP was deduced to induce human monocyte chemokinesis rather than chemotaxis (4). In both examples, it was assumed that the nucleotide increased random migration, but cell velocity could not be quantified because the readout of such assays is limited to the quantification of the number of cells that have crawled across the pores in a thin membrane during a defined time period.

We recently described a robust microscope-based real-time chemotaxis assay for mouse-resident peritoneal macrophages that allows quantification of migration velocity and chemotaxis (19). Using this chemotaxis assay, we investigated whether the hydrolysis-resistant ATP (ATPγS) and ADP (ADPβS) analogs were chemotactic ligands. We have previously shown which purinergic receptor subtypes are functionally expressed in these cells (20), and we confirmed P2Y12 receptor expression by Western blot. Chemotactic assays were supported by confocal fluorescence imaging of gradient kinetics and real-time HPLC measurements. We also used ultraviolet (UV) light-induced photolysis of caged ATP and caged ADP to explore the effects of ATP and ADP on cytoskeletal dynamics independent of flow effects. In addition, we compared the effects of ATPγS and a potent end-target chemoattractant (complement C5a) on Akt and p38 MAPK signaling, both pathways of which have been strongly implicated in chemotaxis signaling (21–24).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Hydrolysis-resistant ATP (ATPγS, lithium salt; > 90% purity) and ADP (ADPβS, lithium salt; > 85% purity) were obtained from Jena Bioscience (Jena, Germany). The lyophilized solids were dissolved in Dulbecco's phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4), and aliquots (10 mm) were stored at −20 °C. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated cadaverine (sodium salt) and fluo-3/AM were obtained from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen). Recombinant mouse complement C5a (R&D Systems; endotoxin level <0.1 ng/1 μg of protein) was dissolved in Dulbecco's phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% fatty acid free bovine albumin (Sigma), and aliquots were stored at −80 °C. Patent Blue V (Chroma Gesellschaft) was dissolved in water at 10 mg/ml, and aliquots were stored at −20 °C. Stock solutions of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) inhibitors LY294002 (50 mm in DMSO) and wortmannin (1 mm in DMSO) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology via New England Biolabs (Frankfurt am Main, Germany) and stored at −20 °C. The p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (Tocris Bioscience) was dissolved in DMSO to 10 mm.

Stock solutions (10 mm, pH 7.5) of P3-(1-(2-nitrophenyl)-ethyl)-ester (NPE)-caged ATP and NPE-caged ADP, both >95% purity, were obtained from Jena Bioscience. Rabbit anti-mouse P2Y12 receptor antibodies (55043A) were obtained from AnaSpec (San Jose, CA). Rabbit monoclonal anti-mouse phospho-Akt (Ser-473) antibodies (193H12) and pan Akt antibodies (C67E7), as well as rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr-180/Tyr-182) antibodies (12F8) and polyclonal anti-p38 MAPK (pan p38 MAPK) antibodies (9212), were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. d-Luciferin, recombinant firefly luciferase, and myokinase were obtained from Sigma. N-(2-Mercaptopropionyl)glycine (Sigma) was dissolved in water, and 1 m aliquots were stored at −20 °C.

Knock-out Mice

P2Y2−/− mice (C57BL/6 strain) were supplied by Jens Leipziger (Aarhus, Denmark). Conditional p38α MAPK knock-out mice were generated by crossing mice with loxP-flanked (floxed) p38α alleles with LysMCre mice (25, 26), which express Cre recombinase (Cre) under the control of the myeloid-specific M lysozyme promotor. Transgenic Lifeact-EGFP mice, recently described by Riedl et al. (27), were supplied by Michael Sixt (Klosterneuburg, Austria).

Resident Peritoneal Macrophages

Mice were killed by an overdose of isoflurane in air, and the peritoneal cavity was lavaged via a 24-gauge plastic catheter (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) using 2 × 4 ml of ice-cold Hanks' balanced salt solution without Ca2+ or Mg2+ (PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria). After centrifugation (360 × g for 5 min), cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2 g/liter bicarbonate (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany) and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (pH 7.4). The cells were seeded into fibronectin-coated μ-slide I chambers or μ-slide chemotaxis chambers (Ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) and placed in a humidified incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). Experiments were performed on the stage of an inverted microscope (AxioVision) equipped with a temperature-controlled incubator (incubator XL S, Zeiss) using the same complete medium as above, except that bicarbonate buffer was replaced by 20 mm Hepes (pH 7.4). Using the limulus amebocyte lysate test, endotoxin could not be detected in the bicarbonate- or Hepes-buffered RPMI 1640 media containing FCS and antibiotics. All procedures and protocols met the guidelines for animal care and experiments in accordance with national and European (86/609/EEC) legislation.

Two-dimensional Chemotaxis Assays

Cells obtained by peritoneal lavage of a single mouse were resuspended in 200–250 μl of medium, and 8 μl of the suspension was seeded into the narrow (1000 × 2000 × 70-μm) channel of an uncoated (IbiTreat) μ-slide chemotaxis chamber (Ibidi). The narrow channel (observation area) connects two 40-μl reservoirs. After 3 h, the chemotaxis chamber was filled with RPMI 1640 (bicarbonate) medium containing 10% FCS and antibiotics.

Prior to performing assays, the chemotaxis chamber was slowly washed with bicarbonate-free medium. Next, 15 μl of medium containing 0.003% Patent Blue V (blue dye) was drawn into one of the reservoirs either without (control) or with a test substance (C5a, ATPγS, or ADPβS). The final concentration of C5a was 20 nm, whereas various concentrations of ATPγS or ADPβS were tested (0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μm). The observation area was imaged by phase-contrast microscopy via a 10×/0.3 objective. The blue dye served as a visual indicator of gradient formation, and we have previously confirmed that it does not affect cell migration (13). Images were captured every 2 min for 14 h, and cell migration tracks between 4 and 12 h (C5a) or between 1 and 9 h (ATPγS and ADPβS) were analyzed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) using a manual tracking plugin and the chemotaxis and migration tool from Ibidi. Twenty-five randomly selected cells were manually tracked in each chemotaxis experiment.

Gradient Kinetics

To simulate the kinetics of ATPγS (Mr 523, free acid) and ADPβS (Mr 443, free acid) gradient formation in the chemotaxis chamber, the nucleotides were replaced by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated cadaverine (Mr 640), and fluorescence gradients were detected by time-lapse confocal imaging using an inverted Olympus FluoView 300 confocal microscope.

Three-dimensional Chemotaxis Assays

The following steps were performed at ∼4 °C. Hanks' balanced salt solution (concentrated 10×) was diluted with H2O to a 2× concentrated solution, to which 50 mm Hepes and ∼0.02 m NaOH were added. This “pH-neutralizing” solution was mixed 1:1 with rat tail collagen (type I) solution (354249; BD Biosciences) containing 9.33 mg/ml collagen in 0.02 m acetic acid. This mixture was then added 1:2 to a cell (macrophage) suspension in RPMI 1640 (Hepes) medium and mixed by once strongly flicking the bottom of the 0.5-ml Eppendorf tube in which the mixture was contained. The final collagen concentration was 1.2 mg/ml (pH was 7.2–7.4). A small volume (10 μl) of the collagen-cell mixture was drawn into the narrow channel of a prefilled μ-slide chemotaxis chamber within minutes of adding C5a or ATPγS (together with Patent Blue V) to one of the reservoirs.

HPLC and Mass Spectrometry

Samples were analyzed using an Agilent 1200 series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies), which included an autosampler coupled to a quaternary pump and a photodiode array detector. HPLC analysis was performed on a 2.0 × 125-mm C18 analytical column (NUCLEODUR C18, 3 μm, MACHEREY-NAGEL). After equilibration of the column with 3% acetonitrile in 10 mm potassium phosphate (pH 5.0) and injection of the sample, nucleotides were eluted in a 50-min gradient to 50% acetonitrile in 10 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.5). Detection was carried out at 259.8 nm. Additionally, UV spectra (200–400 nm) were obtained.

Fourier transform mass spectrometry (FT-MS) analyses were carried out using a Thermo LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) in negative electrospray ionization mode. Adjustments of FT-MS parameters were as follows: capillary temperature, 225 °C; capillary voltage, −21.95 V; tube lens voltage, −103.85 V; multipole 00 offset, 4.6 V; lens 0 voltage, 4.08 V; multipole 0 offset, 4.99 V; lens 1 voltage, 9.06 V; gate lens voltage, 40.16 V; multipole 1 offset, 6.04 V; front lens, 5.01 V. Product ion spectra with higher energy collision-induced dissociation were recorded at an energy level of 30 or 40%. Data analysis was performed using Xcalibur 2.0.7 SP1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Time-lapse Video Microscopy and Photorelease of Caged Nucleotides

Macrophages (seeded into a fibronectin-coated μ-slide I chamber) were incubated in RPMI 1640 (Hepes) medium containing a reactive oxygen species scavenger (1 mm N-(2-mercaptopropionyl)glycine) and either 300 μm NPE-caged ATP or 300 μm NPE-caged ADP. Photolysis was induced by a UV light pulse via a shutter-controlled 100-watt mercury short-arc lamp (HBO 103 W/2, Osram). Differential interference contrast images were obtained via a 63×/1.40 oil immersion objective lens and charge-coupled device camera (AxioCam MRm, Zeiss) controlled by AxioVision software (Zeiss). Images were captured every 15 s.

Detection of Photoreleased ATP and ADP

The reaction mixture was pipetted into a μ-slide I chamber (Ibidi) and contained 500 μm d-luciferin, 2 mg/ml recombinant firefly luciferase, and either 300 μm NPE-caged ATP or 300 μm NPE-caged ADP (together with 500 units/ml myokinase, which catalyzes the reaction: ADP + ADP → ATP + AMP). Photolysis was induced by a UV light pulse, and chemiluminescence was detected by a D104 microscope photometer coupled to the microscope and interfaced with FeliX32 software (Photon Technology International, Seefeld, Germany). Using this system at a high sampling rate (500 Hz), we found that the UV light pulse had a duration of 299.8 ± 0.5 ms (n = 7).

Western Blot

Macrophages were lysed in buffer containing 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 5 mm NaF, 1 mm Na3VO4 (sodium orthovanadate), the protease inhibitors leupeptin, aprotinin, and Pefabloc (each at 10 μg/ml), and 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Proteins were separated by 6–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in TBS containing 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.05% Tween 20 followed by overnight incubation (4 °C) with primary antibodies, diluted 1:250 (Akt and p38 MAPK signaling) or 1:1000 (P2Y12). For detection, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) were used in combination with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate (Perbio, Bonn, Germany).

Single-cell Cytosolic [Ca2+] Measurements

Macrophages were seeded onto a Perspex bath (volume, 100 μl), the bottom of which was a glass coverslip. Cells were imaged via a 40×/1.40 oil objective lens and superfused at 1 ml/min. To monitor intracellular [Ca2+], the cells were incubated for 15–20 min with 10 μm fluo-3/AM. To minimize fluo-3 loss, the medium contained 1 mm probenecid, and recordings were made at room temperature (20–23 °C). In each experiment, a single macrophage (selected with a bilateral iris) was excited at 488 nm, whereas fluorescence was detected at 530 ± 15 nm using a microscope-based spectrofluorometer system (Photon Technology International). Fluorescence signals were normalized with respect to the resting fluorescence intensity (F0) and expressed as F/F0. Solutions were rapidly changed using miniature three-way valves (The Lee Company, Westbrook, CT).

Statistical Analysis

Normality and homoscedasticity were tested using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. A one-way analysis of variance was used to test for statistical differences at the 0.05 level of significance. When the assumed conditions of normality and homogeneity of variance were not fulfilled, we used the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks (at the 0.05 level of significance). Post hoc multiple comparisons were made using Dunn's method. In the case of paired experiments, a t test was used to test for statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat software (Systat Software, Erkrath, Germany), and data are presented as means ± S.E.

RESULTS

Roles of Purinergic Receptors in Chemotaxis

We have recently shown that autocrine purinergic signaling provides feedback loops, which are critical for the chemotactic navigation of macrophages in a C5a gradient (Fig. 1A) (13). In addition to autocrine signaling, ATP and ADP themselves have been implicated as chemotactic ligands (see Introduction and Fig. 1B). However, it is difficult to test the chemotactic activity of ATP and ADP because these adenine nucleotides are rapidly degraded (2, 8, 10, 11). Therefore, we substituted ATP and ADP for the stable analogs ATPγS and ADPβS, respectively. ADPβS has been reported to stimulate Gi-coupled P2Y12 receptors (28, 29), as well as P2Y13 receptors (30). Using single-cell Ca2+ imaging, we could show that ATPγS is a potent agonist of mouse Gq/11-coupled P2Y2 receptors (Fig. 1C). ATPγS was applied in Ca2+-free medium to circumvent Ca2+ influx via P2X ion channels (20). In macrophages lacking P2Y2 receptors (P2Y2−/−), the application of the P2Y2 (and P2Y4) receptor agonist uridine 5′-triphosphate did not increase intracellular [Ca2+], whereas ATP induced a small transient Ca2+ signal (Fig. 1D), consistent with P2X receptor activation (20). Under Ca2+-free conditions, ATPγS did not induce internal Ca2+ release in P2Y2−/− macrophages (Fig. 1, E and F).

FIGURE 1.

P2Y receptor signaling in mouse macrophages. A, recently proposed model of autocrine purinergic signaling involved in the chemotaxis of macrophages to the chemoattractant C5a. B, simple controversial model implicating endogenous (ATP and ADP) and hydrolysis-resistant synthetic (ATPγS and ADPβS) purinergic receptor agonists as chemoattractants. C, Ca2+ oscillations in a single macrophage induced by the application of ATPγS in Ca2+-free medium. D, lack of Ca2+ response in a single P2Y2-deficient (P2Y2−/−) macrophage challenged with the P2Y2 receptor agonist UTP (250 μm). Application of ATP (250 μm) induced a small transient Ca2+ signal (attributable to P2X receptor activation). E, lack of Ca2+ response in a single P2Y2−/− macrophage challenged with 100 μm ATPγS in Ca2+-free medium. F, [ATPγS]-peak Ca2+ response relations for wild-type (WT) and P2Y2−/− macrophages. To establish the concentration-response relation, ATPγS was applied in Ca2+-free medium to obviate Ca2+ influx via P2X receptors or Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels.

Gradient Kinetics

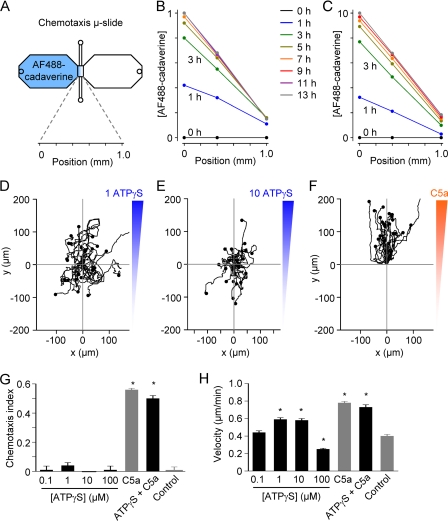

To measure gradient formation in the μ-slide chemotaxis chamber, we substituted ATPγS (Mr 523) and ADPβS (Mr 443) for Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated cadaverine (Mr 640) (Fig. 2A). Confocal fluorescence images of the observation area connecting the two reservoirs of the chemotaxis chamber were captured every 1 h over 13 h. An increasingly steep gradient could be detected (Fig. 2, B and C).

FIGURE 2.

The P2Y2 receptor agonist ATPγS is not a chemoattractant. A, chemotaxis assays were performed using the Ibidi chemotaxis μ-slide, which consists of two 40-μl reservoirs connected by a narrow (1000 × 2000 × 70-μm) channel. To measure gradient kinetics, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated cadaverine (AF488-cadaverine) was added to one of the reservoirs, and serial confocal images of the narrow channel were obtained. B, gradient kinetics measured using an end-target Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated cadaverine concentration of 1 μm. C, gradient kinetics measured using an end-target Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated cadaverine concentration of 10 μm. D–F, migration plots of macrophages in ATPγS or C5a gradients. G and H, summary plots of chemotactic efficiency (chemotaxis index) and mean velocity (n = 4–5 independent experiments for the ATPγS groups; 125–225 cells). The control group (n = 5 independent experiments; 175 cells) represents experiments performed in the absence of a chemical gradient, and C5a was used as a positive control (n = 12 independent experiments; 350 cells). *, p < 0.05 (Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparison test).

ATPγS Is Not a Chemotactic Ligand

Migration plots of macrophages in ATPγS gradients are shown in Fig. 2, D and E. There is no clear preferential direction of migration in ATPγS gradients when compared with cells in a chemotactic C5a gradient (Fig. 2F and supplemental Videos 1 and 2). The mean chemotaxis (y-forward migration) index was ∼0.5 for macrophages in a C5a gradient, whereas no chemotaxis to ATPγS was detected using a range of end-target concentrations (0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μm) (Fig. 2G). When compared with control conditions (absence of chemical gradients), the mean velocity of migration was increased in the 1 and 10 μm ATPγS groups and decreased in the 100 μm ATPγS group. Thus, the P2Y2 receptor agonist ATPγS can induce chemokinesis (increased random migration), but high concentrations are inhibitory. The combination of 10 μm ATPγS and C5a did not augment either chemotactic efficiency or cell velocity (Fig. 2, G and H).

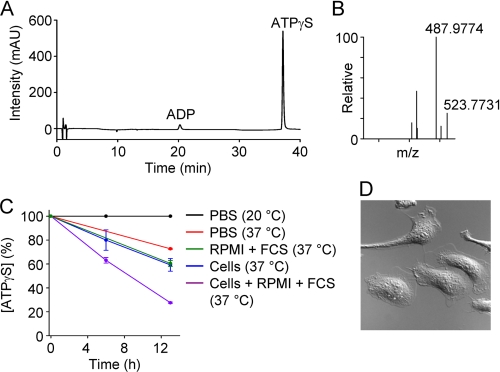

Stability of ATPγS

Although ATPγS is much more resistant to hydrolysis than ATP, degradation could, in principle, explain its lack of chemotactic activity during in vitro chemotaxis assays. Using HPLC, we could detect a dominant peak corresponding to ATPγS (Fig. 3A), which was confirmed by mass spectrometry (Fig. 3B). When stored in Dulbecco's phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at room temperature for 13 h, ATPγS was remarkably stable (Fig. 3C). However, spontaneous hydrolysis was evident during incubation at 37 °C. Furthermore, the presence of FCS or cells, plated at a high density in a μ-slide I chamber (height, 400 μm), increased the rate of hydrolysis (Fig. 3, C and D). The combination of both cells and medium containing FCS had additive effects (Fig. 3C). Chemotaxis was analyzed between 1 and 9 h, and thus, we would expect that about 50% of the high-end concentration is still present during the analysis period (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

HPLC and FT-MS analyses. A, detection of ATPγS by HPLC. mAU, milliabsorbance units. B, identification of ATPγS by mass spectrometry (ionized parent molecule has an m/z (mass-to-charge) ratio of 523.7731). C, degradation of ATPγS (measured by HPLC over 13 h) under five different conditions: (i) PBS at 20 °C, (ii) PBS at 37 °C, (iii) RPMI 1640 medium plus FCS, (iv) mouse peritoneal cells in RPMI 1640 medium (without FCS), or (v) cells in RPMI 1640 medium plus FCS. D, image (100 × 100 μm) of cell density in a μ-slide I chamber, to which 100 μm ATPγS was added.

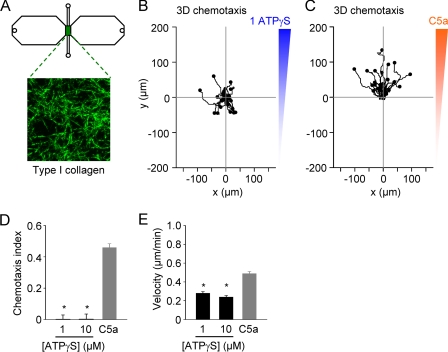

Three-dimensional Chemotaxis

We found that it was possible to do three-dimensional chemotaxis experiments with the μ-slide (two-dimensional) chemotaxis chamber from Ibidi. However, it was necessary to prefill the chamber with medium and add C5a (or ATPγS) before introducing the cell-collagen mixture. Confocal reflection microscopy was used to image the collagen fiber network formed in the μ-slide chemotaxis chamber (Fig. 4A). As in the case of two-dimensional chemotaxis assays, macrophages did not migrate toward ATPγS (Fig. 4B), whereas chemotaxis to C5a was observed (Fig. 4C). Data are summarized in Fig. 4, D and E.

FIGURE 4.

Three-dimensional chemotaxis assays. A, in the case of three-dimensional chemotaxis assays, the cells (in collagen type I) were added after the Ibidi chemotaxis μ-slide had already been filled with medium and ATPγS or C5a had been added to one of the reservoirs. Confocal reflection microscopy was used to obtain images of the type I collagen matrix. Image is 100 × 100 μm. B and C, migration plots of collagen matrix-embedded macrophages in an ATPγS gradient or a C5a gradient. D and E, summary plots of three-dimensional chemotactic efficiency (chemotaxis index) and mean velocity (n = 2–3 independent experiments; total of 75 cells/group). *, p < 0.05 (Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparison test).

ADPβS Is Not a Chemotactic Ligand

P2Y12 receptors have previously been reported to be selectively expressed in microglia (brain macrophages) and not in peripheral macrophages (16, 31). However, we have previously shown that mouse peritoneal macrophages express mRNA for the ADP (and ADPβS)-activated P2Y12 receptor (13). We confirmed that peritoneal F4/80+ cells (macrophages), purified by cell sorting, express P2Y12 at the mRNA level (not shown), and we could detect P2Y12 via Western blot (Fig. 5A); the higher of the two bands is the glycosylated form (32). ADPβS, detected by HPLC and confirmed by MS, was remarkably stable, even in the presence of fetal calf serum and cells (Fig. 5, B–D). As in the case of ATPγS, there was no chemotaxis of cells to ADPβS, tested at a range of end-target concentrations (0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μm) (Fig. 5, E–G). However, in contrast to ATPγS, ADPβS did not induce chemokinesis (Fig. 5H).

FIGURE 5.

ADPβS is not a chemoattractant for P2Y12 receptor expressing macrophages. A, P2Y12 receptors could be detected in human (h) platelets and mouse peritoneal macrophages by Western blot. The upper bands correspond to the glycosylated form of the protein. B, detection of ADPβS by HPLC. mAU, milliabsorbance units. C, identification of ADPβS by mass spectrometry (ionized parent molecule has an m/z (mass-to-charge) ratio of 441.9988). D, degradation of ADPβS (measured by HPLC over 13 h) under five different conditions: (i) PBS at 20 °C, (ii) PBS at 37 °C, (iii) RPMI 1640 medium plus FCS, (iv) mouse peritoneal cells in RPMI 1640 medium (without FCS), or (v) cells in RPMI 1640 medium plus FCS. E and F, migration plots of macrophages in ADPβS gradients. G and H, summary plots of chemotactic efficiency (chemotaxis index) and mean velocity (n = 3–7 independent experiments; 75–350 cells/group). The pooled C5a and control groups are the same as in Fig. 2. *, p < 0.05 (Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparison test).

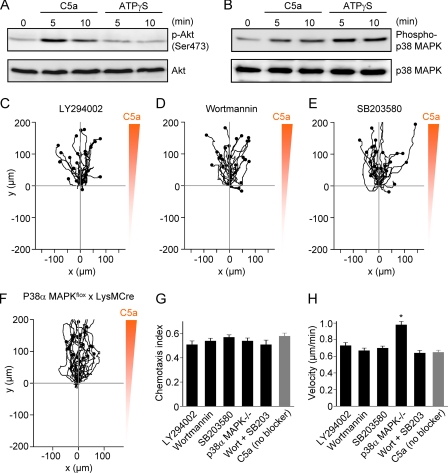

Signal Transduction

We began to address the question of why C5a, but not ATPγS or ADPβS, are chemotactic. PI3K and p38 MAPK signaling have been strongly implicated in chemotactic navigation (21–24). We found that the agonist C5a induced phosphorylation (activation) of both Akt (downstream of PI3K) and p38 MAPK, whereas ATPγS only activated p38 MAPK (Fig. 6, A and B). Next, we tested whether PI3K and p38 MAPK are actually required for macrophage chemotaxis. Macrophage chemotaxis to C5a was not impaired by inhibitors of PI3K (LY294002 and wortmannin) (Fig. 6, C and D). Similarly, chemotaxis to C5a was not impaired by the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (Fig. 6E) or by conditional knock-out of p38α MAPK in macrophages (Fig. 6F); p38α and p38β MAPK are the two dominant isoforms of p38 MAPK, and we could not detect p38β MAPK in p38α-deficient macrophages. Furthermore, macrophage chemotaxis to C5a was also not impaired by a combination of PI3K and p38 MAPK inhibitors, as shown in the summary data (Fig. 6, G and H). Interestingly, we observed that macrophages migrating directionally in the presence of LY294002 or wortmannin frequently had a spindle-shaped morphology, suggestive of impaired cell polarization.

FIGURE 6.

Signal transduction and redundancy of PI3K and p38 MAPK pathways in macrophage chemotaxis. A, Western blot analysis of Akt signaling in mouse peritoneal macrophages. C5a, but not ATPγS, induced phosphorylation of Akt (p-Akt) at Ser-473 (blots are representative of 3 independent experiments). Akt is activated by phosphorylation. B, Western blot analysis of p38 MAPK signaling in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Both C5a and ATPγS induced dual phosphorylation of p38 MAPK at Thr-180 and Tyr-182 (blots are representative of 3 independent experiments). p38 MAPK is activated by phosphorylation at Thr-180 and Tyr-182. C and D, the PI3K inhibitors LY294002 (10 μm) and wortmannin (100 nm) did not impair macrophage chemotaxis to C5a. E, the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10 μm) did not impair macrophage chemotaxis to C5a. F, conditional deletion of p38α MAPK in macrophages did not impair macrophage chemotaxis to C5a. G and H, summary plots of chemotactic efficiency (chemotaxis index) and mean velocity (n = 3–6 independent experiments; 75–150 cells/group). Note that the pooled C5a group is not the same as in Fig. 2 (and Fig. 5). *, p < 0.05 (Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparison test). Wort, wortmannin.

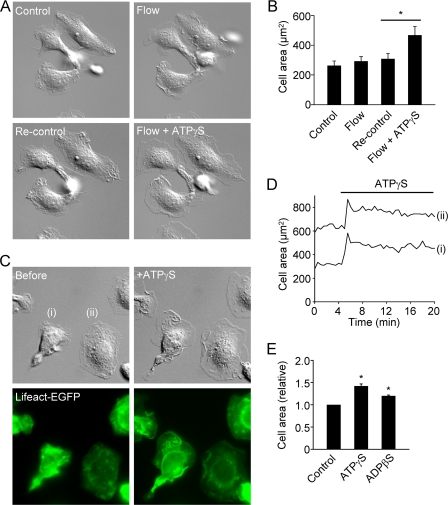

Flow- and ATPγS-induced Membrane Protrusive Activity

Our data obtained with the synthetic P2Y2 receptor agonist ATPγS indicate that ATP is not a chemotactic ligand. Thus, ATP released from dying cells does not act as a long-range find me signal to attract professional phagocytes (macrophages). However, we speculate that ATP released from dying cells may act as local touch me signals by inducing macrophage spreading. We have previously reported that macrophages superfused with P2Y2 and P2Y12 receptor agonists generate lamellipodial membrane protrusions (13). However, superfusion (flow) itself can induce robust membrane ruffling and some lamellipodial membrane extensions (Fig. 7A). The subsequent application of ATPγS produces much more prominent membrane protrusions (Fig. 7, A and B). Membrane protrusions are driven by actin polymerization. To visualize F-actin, we isolated macrophages from Lifeact-EGFP mice, which ubiquitously express the F-actin-binding protein Lifeact fused to EGFP (27). Application of 50 μm ATPγS to macrophages (which had not been acutely subjected to superfusion) generated robust F-actin-driven lamellipodial extensions. The kinetics of spreading is shown in Fig. 7D. Typically, cells rapidly spread and reach a peak two-dimensional cell area within 45–60 s and then gradually retract the lamellipodia. Summary data of the peak area after application of 50 μm ATPγS or ADPβS are shown in Fig. 7E. We speculated that the actin dynamics of resting macrophages may be stimulated by autocrine ATP signaling. However, we found that the presence of apyrase (40 units/ml) did not inhibit the membrane dynamics of resting cells (supplemental Videos 3 and 4).

FIGURE 7.

Flow- versus ATPγS-induced lamellipodial membrane protrusions. A, superfusion of macrophages induces ruffling and weak membrane protrusive activity. Subsequent superfusion of the same cells with medium containing 100 μm ATPγS induces more pronounced membrane protrusions. The differential interference contrast images are 80 × 80 μm. B, summary of effects of flow and flow plus ATPγS on cell two-dimensional area. Area was measured before and 1 min after superfusion with either medium alone or medium plus ATPγS (n = 3 independent experiments; 15 cells). C, application of 50 μm ATPγS to Lifeact-EGFP macrophages (lower green fluorescent images show F-actin labeling). Images are 70 × 70 μm. The upper right image (labeled +ATPγS) was taken 45 s after application of ATPγS. D, kinetics of cell spreading (the traces correspond to the two complete cells shown in C). E, summary of relative cell area before (Control) and 45 s after application of ATPγS or ADPβS. *, p < 0.05 (paired t tests).

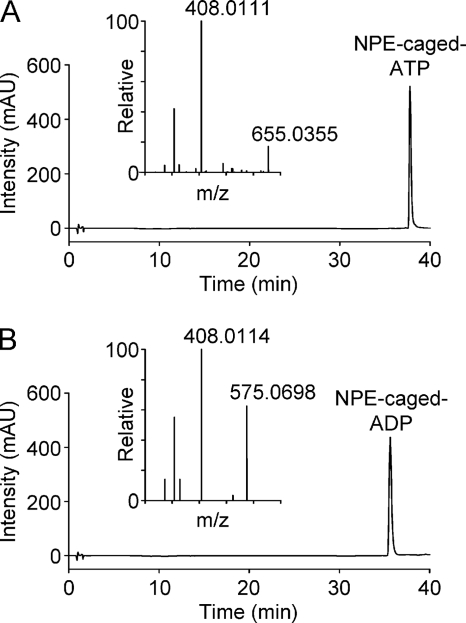

Lamellipodial Membrane Protrusions Induced by Photorelease of ATP and ADP

To confirm that ATP and ADP induce membrane protrusive activity independent of flow, we increased extracellular nucleotide concentrations by photolysis of NPE-caged ATP or NPE-caged ADP. Using HPLC, we confirmed that the NPE-caged nucleotides contained no detectable free nucleotides (Fig. 8, A and B), which could potentially desensitize P2Y receptors; the composition and mass of the molecules were confirmed by FT-MS (Fig. 8, A and B). In the presence of d-luciferin and firefly luciferase, a flash of UV light induced light emission, confirming that ATP was released from its NPE-caged form (Fig. 9A). Initially, photorelease of ATP caused macrophages to “freeze,” characterized by a lack of spontaneous membrane dynamics followed by cell death. This effect was not due to the UV flash. Instead, we deduced that it was caused by the generation of reactive oxygen species because it could be abrogated by a reactive oxygen species scavenger (N-(2-mercaptopropionyl)glycine). When experiments were repeated using medium containing N-(2-mercaptopropionyl)glycine, photorelease of ATP induced lamellipodial membrane protrusions (Fig. 9B).

FIGURE 8.

HPLC and mass spectrometry analysis of NPE-caged compounds. A, detection of NPE-caged ATP by HPLC and molecular identity by mass spectrometry (ionized parent molecule has an m/z (mass-to-charge) ratio of 655.0355). The preparation was not contaminated by ATP or ADP. mAU, milliabsorbance units. B, detection of NPE-caged ADP by HPLC and molecular identity by mass spectrometry (ionized parent molecule has an m/z (mass-to-charge) ratio of 575.0698). The preparation was not contaminated by ATP or ADP.

FIGURE 9.

Photorelease of ATP and ADP from NPE-caged compounds induces macrophage membrane protrusions. A, confirmation that a UV light flash (300 ms) induces release of ATP from NPE-caged ATP. An Ibidi μ-slide I chamber containing 300 μm NPE-caged ATP, as well as d-luciferin and luciferase, was placed on the stage of an inverted microscope, which was coupled to a photomultiplier tube. Following the UV flash, a transient (green) light signal was detected, consistent with photorelease of ATP. B, lamellipodial membrane protrusions induced by photorelease of ATP. Image is 80 × 80 μm. C, confirmation that a UV flash (300 ms) induces release of ADP from NPE-caged ADP. The luciferase-catalyzed reaction was coupled to myokinase to generate ATP from ADP. D, lamellipodial membrane protrusions induced by photorelease of ADP. Image is 80 × 80 μm. E and F, summary of effects of photorelease of ATP and ADP on the cell two-dimensional area. Photorelease of ATP did not increase the cell area in P2Y2-deficient (P2Y2−/−) macrophages.

We could indirectly detect ADP release from NPE-caged ADP by coupling the luciferase-based reaction to myokinase (Fig. 9C). Photorelease of ADP weakly induced lamellipodial membrane protrusions (Fig. 9D). A summary of UV photolysis experiments is shown in Fig. 9, E and F. Note that UV photorelease of ATP did not induce membrane protrusions in P2Y2-deficient macrophages, indicating that ATP-induced spreading is mediated by P2Y2 receptors, rather than P2X receptors.

DISCUSSION

In the past decade, it has become clear that inflammation, especially the recruitment and activity of macrophages, is closely linked to chronic diseases (33). The central question addressed in this study is whether the purinergic receptor agonists ATP and ADP are chemotactic signals for professional mouse phagocytes (macrophages). ATP has been implicated in macrophage recruitment to sites of inflammation or tissue injury; however, there are conflicting reports regarding whether natural and synthetic purinergic receptor agonists (i) induce chemotaxis (7, 16, 17, 34–36) and/or (ii) induce chemokinesis (4, 12, 35) or (iii) even inhibit the migration of immune cells (37). A major limitation of many of these studies is the use of Transwell (Boyden) chambers for chemotaxis assays. These end-point assays do not allow (i) measurement of cell velocity, (ii) determination of chemotaxis efficiency (chemotaxis index), or (iii) reliable discrimination between chemokinetic and chemotactic responses (18). To overcome these problems, we recently established a macrophage chemotaxis assay using the Ibidi μ-slide chemotaxis slide, which enables real-time (microscope-based) imaging of the motility of single cells in a chemotactic gradient (19). Using this system, we found that synthetic agonists of P2Y2 (ATPγS) and P2Y12 (ADPβS) receptors were not chemoattractants, although ATPγS, but not ADPβS, induced chemokinesis at intermediary concentrations.

It could be argued that ATPγS and ADPβS were degraded under our experimental conditions, thereby preventing chemical gradient formation. Indeed, using HPLC, we found that ATPγS, more so than ADPβS, was degraded. However, we used a broad range of end-target concentrations in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional (in the case of ATPγS) assays, which should have revealed chemotaxis if ATPγS or ADPβS were chemotactic ligands. Thus, our data indicate that ATP is not the find me signal studied by the Elliott et al. (7), at least in the case of macrophages. The inhibitory effects of apyrase and P2Y2 receptor deficiency on phagocyte recruitment (7) induced by dying cells could be explained by interference with autocrine ATP signaling, which may act as a signal amplifier for a range of find me chemoattractants (12, 13). Extracellular ATP is probably restricted to autocrine and paracrine signaling, and its short half-life in the extracellular space (2, 8, 12) makes it an unsuitable long-range chemotactic find me signal. However, in line with a role of nucleotides in phagocytosis (7, 34), we found that photorelease of ATP or ADP induced macrophage lamellipodial extensions. Thus, ATP or ADP leaking from a dying cell could act as local (short-range) touch me signals by inducing macrophage spreading.

Stimulation of macrophages with ATPγS or the chemoattractant C5a induces a number of responses in common, such as the release of Ca2+ from internal stores and lamellipodial membrane protrusions (13, 20). However, only C5a acts as a chemoattractant. We found that both C5a and ATPγS activated p38 MAPK, whereas only C5a activated Akt, indexed as phosphorylation at Ser-473. Further work will be required to determine whether the lack of phosphorylation of Akt at Ser-473 accounts in part for the lack of chemotactic activity of ATPγS. Although mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) mediates the phosphorylation of Akt at Ser-473, the phosphorylation at this site is a good readout for PI3K activity (38). In future studies, comparison of the signaling triggered by C5a and ATPγS may provide a means to identify signal components and pathways essential for chemotactic signaling. For example, it would be interesting to test whether ATPγS induces ATP release (inside-out signal amplification) and to screen for differences in protein phosphorylation (kinase target screening).

A hierarchy of chemoattractants and signaling pathways has been implicated in neutrophil chemotaxis, such that in the face of opposing gradients, cells preferentially migrate toward end-target (strong) rather than intermediary (weak) chemoattractants (21–24). The weaker intermediary chemoattractants (namely, chemokines) are thought to be dependent on PI3K signaling, whereas the end-target chemoattractants, such as complement or bacterial components, are largely PI3K-independent but require intact p38 MAPK signaling. Consistent with a redundant role for PI3K in chemotactic signaling induced by end-target chemoattractants, we found that macrophage chemotaxis to C5a was not impaired by inhibitors of PI3K (LY294002 and wortmannin). Surprisingly, however, chemotaxis to C5a was not impaired by the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 or by conditional knock-out of p38α MAPK in macrophages. Furthermore, macrophage chemotaxis to C5a was not impaired by a combination of PI3K and p38 MAPK inhibitors, ruling out potential compensatory effects of the two pathways. Thus, PI3K and p38 MAPK signaling pathways are essentially redundant for macrophage chemotaxis.

In summary, autocrine and paracrine ATP signaling regulates the function of virtually every cell (1, 2), and recently, chemoattractant-induced release of ATP and autocrine feedback have been shown to be important for chemotaxis (12, 13). ATP itself is thought to be a chemoattractant, but it is rapidly degraded in the extracellular space, which would limit its reach. Using real-time chemotaxis assays, we show that hydrolysis-resistant analogs of ATP (ATPγS) and ADP (ADPβS) have no chemotactic activity, whereas intermediary concentrations of ATPγS induce chemokinesis. We also show that both C5a and ATPγS activate p38 MAPK, whereas only C5a activates Akt. However, inhibition of PI3K and p38 MAPK pathways, strongly implicated in neutrophil chemotaxis (21–24), did not impair chemotaxis, indicating that these pathways are redundant for macrophage chemotaxis. Finally, we show that photorelease of ATP or ADP induces lamellipodial membrane protrusive activity. We speculate that this membrane protrusive activity may play a role in autocrine feedback during chemotaxis (12, 13) and phagocytosis, such that ATP and ADP leaking from dying cells may act as local touch me signals.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported in part by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Grants SCHW 407/9-3 and SCHW 903/3-2 (to A. S.) and SCHW 903/4-1 (to T. S.). In addition, this work was supported by a grant from the Graduate School of Chemistry (to J. B.) and Innovative Medizinische Forschung (IMF) Grants HA110710 (to P. J. H.) and IS611005 (to K. I.) from the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Videos 1–4.

- ATPγS

- adenosine-5′-(γ-thio)-triphosphate

- ADPβS

- adenosine-5′-(β-thio)-diphosphate

- NPE

- (P3-(1-(2-nitrophenyl)-ethyl)-ester)

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FT-MS

- Fourier transform mass spectrometry

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Praetorius H. A., Leipziger J. (2009) Purinergic Signal. 5, 433–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Junger W. G. (2011) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 201–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lazarowski E. R., Sesma J. I., Seminario-Vidal L., Kreda S. M. (2011) Adv. Pharmacol. 61, 221–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaufmann A., Musset B., Limberg S. H., Renigunta V., Sus R., Dalpke A. H., Heeg K. M., Robaye B., Hanley P. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32459–32467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trautmann A. (2009) Sci. Signal. 2, pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hanley P. J., Musset B., Renigunta V., Limberg S. H., Dalpke A. H., Sus R., Heeg K. M., Preisig-Müller R., Daut J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9479–9484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elliott M. R., Chekeni F. B., Trampont P. C., Lazarowski E. R., Kadl A., Walk S. F., Park D., Woodson R. I., Ostankovich M., Sharma P., Lysiak J. J., Harden T. K., Leitinger N., Ravichandran K. S. (2009) Nature 461, 282–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yegutkin G. G. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 673–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stefan C., Jansen S., Bollen M. (2006) Purinergic Signal. 2, 361–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fitz J. G. (2007) Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 118, 199–208 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mortensen S. P., Thaning P., Nyberg M., Saltin B., Hellsten Y. (2011) J. Physiol. 589, 1847–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen Y., Corriden R., Inoue Y., Yip L., Hashiguchi N., Zinkernagel A., Nizet V., Insel P. A., Junger W. G. (2006) Science 314, 1792–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kronlage M., Song J., Sorokin L., Isfort K., Schwerdtle T., Leipziger J., Robaye B., Conley P. B., Kim H. C., Sargin S., Schön P., Schwab A., Hanley P. J. (2010) Sci. Signal. 3, ra55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davalos D., Grutzendler J., Yang G., Kim J. V., Zuo Y., Jung S., Littman D. R., Dustin M. L., Gan W. B. (2005) Nat. Neurosci. 8, 752–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nimmerjahn A., Kirchhoff F., Helmchen F. (2005) Science 308, 1314–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haynes S. E., Hollopeter G., Yang G., Kurpius D., Dailey M. E., Gan W. B., Julius D. (2006) Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1512–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCloskey M. A., Fan Y., Luther S. (1999) J. Immunol. 163, 970–977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zantl R., Horn E. (2011) Methods Mol. Biol. 769, 191–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hanley P. J., Xu Y., Kronlage M., Grobe K., Schön P., Song J., Sorokin L., Schwab A., Bähler M. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12145–12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. del Rey A., Renigunta V., Dalpke A. H., Leipziger J., Matos J. E., Robaye B., Zuzarte M., Kavelaars A., Hanley P. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35147–35155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heit B., Tavener S., Raharjo E., Kubes P. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 159, 91–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heit B., Robbins S. M., Downey C. M., Guan Z., Colarusso P., Miller B. J., Jirik F. R., Kubes P. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 743–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Foxman E. F., Campbell J. J., Butcher E. C. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139, 1349–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yen H., Zhang Y., Penfold S., Rollins B. J. (1997) J. Leukoc Biol. 61, 529–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heinrichsdorff J., Luedde T., Perdiguero E., Nebreda A. R., Pasparakis M. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9, 1048–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clausen B. E., Burkhardt C., Reith W., Renkawitz R., Förster I. (1999) Transgenic Res. 8, 265–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Riedl J., Flynn K. C., Raducanu A., Gärtner F., Beck G., Bösl M., Bradke F., Massberg S., Aszodi A., Sixt M., Wedlich-Söldner R. (2010) Nat. Methods 7, 168–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Foster C. J., Prosser D. M., Agans J. M., Zhai Y., Smith M. D., Lachowicz J. E., Zhang F. L., Gustafson E., Monsma F. J., Jr., Wiekowski M. T., Abbondanzo S. J., Cook D. N., Bayne M. L., Lira S. A., Chintala M. S. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 107, 1591–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang F. L., Luo L., Gustafson E., Lachowicz J., Smith M., Qiao X., Liu Y. H., Chen G., Pramanik B., Laz T. M., Palmer K., Bayne M., Monsma F. J., Jr. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 8608–8615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Communi D., Gonzalez N. S., Detheux M., Brézillon S., Lannoy V., Parmentier M., Boeynaems J. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41479–41485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sasaki Y., Hoshi M., Akazawa C., Nakamura Y., Tsuzuki H., Inoue K., Kohsaka S. (2003) Glia 44, 242–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bodor E. T., Waldo G. L., Hooks S. B., Corbitt J., Boyer J. L., Harden T. K. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 64, 1210–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Couzin-Frankel J. (2010) Science 330, 1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koizumi S., Shigemoto-Mogami Y., Nasu-Tada K., Shinozaki Y., Ohsawa K., Tsuda M., Joshi B. V., Jacobson K. A., Kohsaka S., Inoue K. (2007) Nature 446, 1091–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Verghese M. W., Kneisler T. B., Boucheron J. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 15597–15601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Honda S., Sasaki Y., Ohsawa K., Imai Y., Nakamura Y., Inoue K., Kohsaka S. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 1975–1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Elferink J. G., de Koster B. M., Boonen G. J., de Priester W. (1992) Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 317, 93–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang J., Manning B. D. (2009) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 217–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.