Abstract

The γ-glutamyl carboxylase converts Glu to carboxylated Glu (Gla) to activate a large number of vitamin K-dependent proteins with diverse functions, and this broad physiological impact makes it critical to understand the mechanism of carboxylation. Gla formation is thought to occur in two independent steps (i.e. Glu deprotonation to form a carbanion that then reacts with CO2), based on previous studies showing unresponsiveness of Glu deprotonation to CO2. However, our recent studies on the kinetic properties of a variant enzyme (H160A) showing impaired Glu deprotonation prompted a reevaluation of this model. Glu deprotonation monitored by tritium release from the glutamyl γ-carbon was dependent upon CO2, and a proportional increase in both tritium release and Gla formation occurred over a range of CO2 concentrations. This discrepancy with the earlier studies using microsomes is probably due to the known accessibility of microsomal carboxylase to water, which reprotonates the carbanion. In contrast, tritium incorporation experiments with purified carboxylase showed very little carbanion reprotonation and consequently revealed the dependence of Glu deprotonation on CO2. Cyanide stimulated Glu deprotonation and carbanion reprotonation to the same extent in wild type enzyme but not in the H160A variant. Glu deprotonation that depends upon CO2 but that also occurs when water or cyanide are present strongly suggests a concerted mechanism facilitated by His-160 in which an electrophile accepts the negative charge on the developing carbanion. This revised mechanism provides important insight into how the carboxylase catalyzes the reaction by avoiding the formation of a high energy discrete carbanion.

Keywords: Carboxylation, Enzyme Catalysis, Enzyme Mechanisms, Enzyme Mutation, Isotope Effects, Membrane Enzymes, Post-translational Modification, Vitamin K, Vitamins and Cofactors

Introduction

Activation of vitamin K-dependent (VKD)2 proteins is mediated by the γ-glutamyl carboxylase, an integral membrane enzyme that resides in the endoplasmic reticulum and modifies VKD proteins during their secretion (1). A recognition signal in the VKD proteins, which is usually a propeptide, confers tight association with the carboxylase and the processive modification of clusters of Glu residues to carboxylated Glu (Gla) residues in their Gla domains (2, 3). The propeptide is removed in the Golgi, and the Gla domain is transformed into a calcium-binding module that targets the VKD proteins to cell surfaces where negatively charged phospholipids are exposed or to hydroxyapatite in the extracellular matrix. Carboxylation was originally discovered in association with hemostasis, and severe bleeding is observed in some patients with naturally occurring carboxylase mutations and in carboxylase null mice that die mid-gestation (4–8). However, Glu carboxylation is now known to have broader physiological impact because VKD proteins have also been shown to have functions that include calcium homeostasis, growth control, apoptosis, and signal transduction (9). Recently, a new class of naturally occurring carboxylase mutations was identified that causes a pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like phenotype associated with calcification of soft tissue and only mild bleeding defects (10, 11). The discovery that carboxylase mutations result in two distinctly different diseases underscores the importance of this enzyme to human health. The carboxylase was first identified in mammals; however, orthologs have also been revealed in other multicellular organisms, such as marine snails, Drosophila, fish, and tunicates (12–19). In addition, genomic sequencing has uncovered proteins with striking homology to the carboxylase in a large number of bacteria, which are thought to have acquired the carboxylase from metazoans by horizontal gene transfer (20, 21). The only bacterial ortholog to have been characterized to date is from Leptospira borgpetersenii, which appears to have adapted the enzyme for a purpose other than Glu carboxylation (22).

The carboxylase drives Glu carboxylation by harnessing the energy obtained from oxygenation of the reduced form of vitamin K (i.e. vitamin K hydroquinone (KH2)). Chemical modeling studies have led to a “base amplification” model in which a weak base in the carboxylase active site deprotonates KH2 for reaction with O2 to form a much stronger vitamin K base (23). This strong base, which is thought to be an alkoxide or dialkoxide species, then deprotonates Glu to react with CO2 and form the Gla product (Fig. 1). Protonation of the vitamin K base results in the ultimate production of vitamin K epoxide, which is subsequently recycled back to KH2 by the vitamin K oxidoreductase (24). How the carboxylase facilitates catalysis is largely unknown because it is a large, integral membrane protein without structural information that reveals functional residues (9). A critical breakthrough in understanding the mechanism and in beginning to define the active site was the identification of Lys-218 as the weak base that initiates the reaction by deprotonating KH2 to generate the vitamin K base (25).

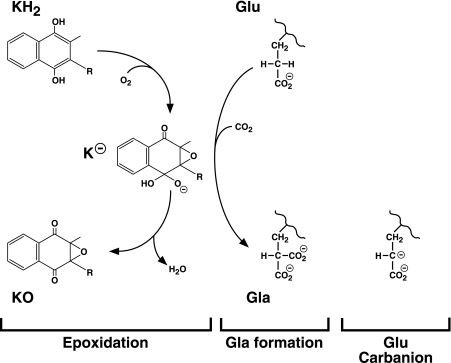

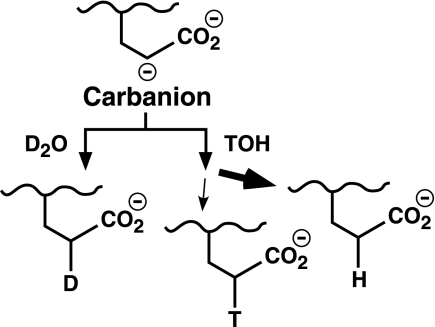

FIGURE 1.

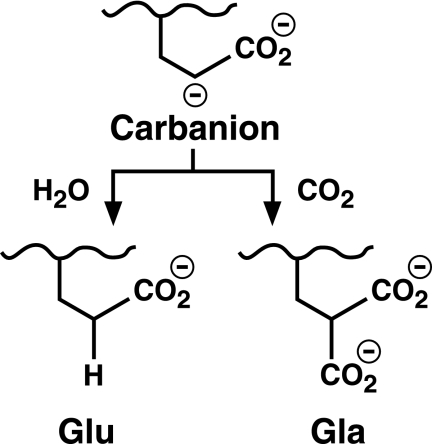

The carboxylase reaction. The carboxylase is a bifunctional enzyme that converts KH2 to vitamin K epoxide (KO) and Glu residues to Gla. A highly basic vitamin K intermediate (K−) (e.g. the alkoxide that is shown) is proposed to abstract a hydrogen from the glutamyl γ-carbon to form a carbanion that reacts with CO2 to generate Gla. Previous studies (26) led to a model in which the formation of a discrete Glu carbanion (shown on the right) and the reaction of the carbanion with CO2 to form Gla are two independent steps. However, the results presented here show that Glu deprotonation depends upon CO2 and suggest that Gla formation occurs in a single step.

Currently, Glu carboxylation is thought to occur in two independent steps that can be uncoupled if CO2 is not available. Thus, Glu deprotonation is believed to result in the formation of a discrete carbanion (i.e. the Glu carbanion shown in Fig. 1), which subsequently reacts with CO2 to generate Gla. This stepwise mechanism is based on studies showing that Glu deprotonation is unaffected by the level of CO2 (26). However, recent results prompted us to reevaluate the question of whether Glu carboxylation does in fact occur in a stepwise mechanism. We found that carboxylase residue His-160 is required for Glu deprotonation (27); however, the H160A mutant that revealed the function of His-160 had a puzzling property, which was a 5-fold increase in Km for CO2 and which suggested that Glu deprotonation mediated by His-160 depends upon the presence of CO2. The original studies that led to the conclusion that carbanion formation and CO2 addition are two independent steps used crude microsomes as the source of carboxylase (26), and we therefore performed similar experiments using purified enzyme. As described below, the results show that Glu deprotonation clearly depends upon CO2, and they suggest a concerted mechanism of Gla formation in which Glu deprotonation and CO2 addition occur simultaneously. Importantly, these findings provide insight into how the carboxylase catalyzes the reaction by avoiding the formation of a fully negatively charged carbanion intermediate.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Isolation of Carboxylase

Baculoviruses containing wild type carboxylase or a variant with His-160 substituted by Ala were generated and expressed in SF21 insect cells as previously described (27). Both enzymes contain a C-terminal addition of an alanine linker followed by the FLAG epitope (i.e. AAADYKDDDDK). Microsomes from SF21 cells infected with baculoviruses at a multiplicity of infection of 5 were prepared in 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 500 mm NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol. The microsomes were adjusted to a final concentration of 4 mg/ml protein, as determined by a BCA assay (Pierce), followed by solubilization with a 0.5%/0.1% (w/v) mixture of CHAPS and phosphatidylcholine. After centrifugation (100,000 × g, 4 °C, 1 h), carboxylase was affinity-purified from the solubilized microsomes using agarose-coupled anti-FLAG antibody resin (Sigma). Sample (1 ml) was nutated overnight with anti-FLAG resin (100 μl, 0.6 mg/ml), which was then washed by five successive rounds of centrifugation (10,000 × g, 1 min) and incubation in 1 ml of 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.3% (w/v) CHAPS, 0.2% (w/v) phosphatidylcholine, and 500 mm NaCl, all at 4 °C. Carboxylase was eluted for 1 h at 4 °C with 200 μl of the same buffer but containing FLAG peptide (100 μg/ml; Sigma), followed by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 1 min) to recover the carboxylase in the supernatant. The carboxylase levels were quantitated using combined LI-COR and Western analysis and a BAP-FLAG standard (Sigma). Wild type carboxylase was also tested in an activity assay and had a specific activity indistinguishable from enzyme isolated from tissue (28), indicating that the recombinant form was fully functional. Purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (Fig. 2), and all experiments described below used purified carboxylase.

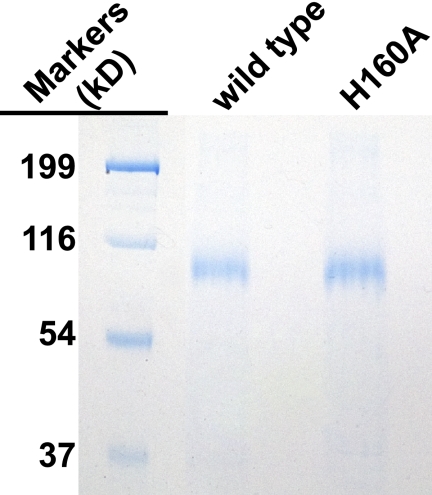

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of purified carboxylase. Wild type carboxylase and an H160A mutant with C-terminal FLAG tags were affinity-purified using immobilized anti-FLAG antibody, and 1 μg of each protein was then subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

Carboxylase complexed with factor IX was also generated by coinfecting SF21 cells with baculoviruses containing the carboxylase and factor IX (28, 29) at multiplicities of infection of 2 and 10, respectively. Microsomes were solubilized as with free carboxylase, except that the NaCl concentration was 200 mm and phosphatidylcholine was omitted. To monitor the extent of complex formation between factor IX and the carboxylase, immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using anti-FLAG-agarose and an immobilized polyclonal anti-factor IX antibody (2.5 mg/ml) (30). Aliquots (450 μl) were incubated overnight with antibody-containing resin (100 μl). The resins were washed, and the anti-FLAG resin was incubated with FLAG peptide as described above. Factor IX and the carboxylase were then monitored by assaying starting sample (i.e. the solubilized microsomes), unbound material, and eluant (in the anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation) or washed resin (in the anti-factor IX immunoprecipitation). The factor IX was quantitated using LI-COR/Western analysis and a pure factor IX standard (Enzyme Research Laboratory), and carboxylase was measured by an activity assay (28). Large amounts of complex were then generated by immunopurification on the anti-FLAG resin. An aliquot of the anti-FLAG eluant was tested for the stability of the carboxylase-factor IX complex by immunopurification on anti-factor IX resin as described above.

Preparation of Reduced Vitamin K

Chemical reduction of vitamin K quinone under nitrogen was used to prepare CO2-free KH2 cofactor. All steps were performed with minimal lighting. Phylloquinone (0.2 mmol; Sigma) in 40 ml of ether was shaken vigorously for 5 min with 250 ml of 170 mm sodium hydrosulfite, and the ether layer was then evaporated to dryness with a stream of dry nitrogen. The residual KH2 was taken up in 10 ml of ethanol under nitrogen, and aliquots were transferred to sealed vials pregassed with nitrogen. The KH2 concentration was determined by absorbance at 248 nm (ϵ = 19 mm−1 cm−1).

Synthesis of FL-[14C]EEL and KFL-[14C]EEL

Radioactive peptides were generated to monitor the recovery of reaction products. The peptides Phe-Leu-Glu-Glu-Leu (FLEEL (5 mm), AnaSpec) and Lys-Phe-Leu-Glu-Glu-Leu (KFLEEL (5 mm), AnaSpec) were individually carboxylated in 1-ml reactions containing 5.5 mm [14C]bicarbonate (55 mCi/mmol; Amersham Biosciences), 50 mm BES, pH 6.9, 2 mm KH2, carboxylase (∼150 nm), and a core reaction mixture used in almost all reactions described in this work. The core reaction mixture was composed of 0.8 m ammonium sulfate, 0.16% (w/v) CHAPS, 0.16% (w/v) phosphatidylcholine, 10 μm factor X propeptide, and 2.5 mm DTT. After incubation at 21 °C for 2 days, water (1 ml) was added, and the samples were boiled (to ∼200 μl) to eliminate unreacted [14C]CO2. The samples were placed on ice, and 800 μl of ice-cold acetone was added to precipitate detergent and proteins. After 1 h at 4 °C, the samples were centrifuged (10,000 × g, 4 °C, 15 min), and the supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes and evaporated to 200 μl with a stream of dry nitrogen, followed by chromatography on P-2 columns (Bio-Rad) using 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8. Fractions containing radioactivity were pooled and lyophilized to dryness. Carboxylated and uncarboxylated peptides were then separated by HPLC using a Hypersil C18 column (Thermo Scientific) and isocratic elution with 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5, 15% (v/v) acetonitrile. The carboxylated peptides were located by absorbance at 258 nm and scintillation counting. The peptides are preferentially carboxylated at the first Glu (31, 32), yielding the products Phe-Leu-[14C]Gla-Glu-Leu and Lys-Phe-Leu-[14C]Gla-Glu-Leu. These peptides were used to generate FL-[14C]EEL and KFL-[14C]EEL by heating under acidic conditions, which results in non-stereospecific elimination of only one carboxyl group from Gla (33). After three rounds of incubation in 50 mm HCl (100 μl) and lyophilization, the peptides were heated to 110 °C for 9 h under nitrogen, followed by neutralization with 100 mm ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8 (100 μl) and lyophilization to dryness. The samples were subjected to four cycles of resuspension in 50 mm HCl (100 μl) and lyophilization, and the decarboxylated peptides were purified by HPLC as above and quantitated by absorbance and scintillation counting.

Removal of Endogenous CO2 from Carboxylase Reactions

Initial experiments revealed that the reaction mixture and enzyme preparation contained appreciable levels of endogenous CO2, which was measured as described previously (27), and steps were therefore taken to remove CO2. Reactions (170 μl) containing 5 mm FLEEL, 50 mm BES, pH 6.9, carboxylase (∼150 nm), and core reaction mixture were incubated without further manipulation or were placed in vials with rubber septums that allowed gassing either over the headspace or directly in the sample. A fourth set of reactions containing 25 mm MES, pH 5.5, instead of BES was also gassed directly in solution in the sealed vial, followed by neutralization with 80 mm BES, pH 7.25, which adjusted the final pH to 6.9. All of the reactions were then initiated by the addition of CO2-free KH2 (2 mm final concentration), prepared as described above. The reactions were incubated for 4 h at 21 °C, and Gla formation was then monitored by peptide isolation, followed by amino acid analysis. Peptide was isolated by acetone precipitation and P-2 chromatography as described above. The peptide was hydrolyzed with base, and amino acids were derivatized with o-phthalaldehyde, followed by HPLC and fluorescence to quantitate the amount of derivatized Gla and Glu, as before (34). All of the assays were performed in duplicate.

These experiments indicated a substantial decrease in the amount of Gla formation from endogenous CO2 in samples that underwent low pH gassing, so the following manipulations were implemented in subsequent experiments. All reagents (except bicarbonate, KH2, and carboxylase) were bubbled for 2 h with nitrogen in a glove bag (Captair Pyramid, Erlab Group) flushed twice with nitrogen and filled with a final 1:1 mixture of nitrogen/oxygen. Reaction mixtures containing carboxylase were then bubbled at pH 5.5 for 10 min with a nitrogen/oxygen mixture prehumidified so as not to reduce the volume of the sample by evaporation. Pilot experiments revealed that bubbling for 10 min did not result in significant loss of enzyme activity; however, longer times attenuated activity. The reaction mixture was divided into aliquots and then titrated to pH 6.9 by the addition of 80 mm BES, pH 7.25. Bicarbonate was then added to supply CO2, if used, and the reactions were initiated with CO2-free KH2.

Measuring Glu Deprotonation

Tritium release from the glutamyl γ-carbon was used as a direct measure of Glu deprotonation. Reaction mixtures were prepared (170 μl) that contained 5 mm Phe-Leu-[R,S-3H]Glu-Glu-Leu (FL-[R,S-3H]EEL, specific activity 98 cpm/nmol), 25 mm MES, pH 5.5, carboxylase (∼150 nm), and core reaction mixture. FL-[R,S-3H]EEL was prepared as described previously (27) except that peptide purification by HPLC used a different mobile phase (i.e. 15% (v/v) acetonitrile with 50 mm ammonium acetate, pH 8.5, instead of bicarbonate). The reaction mixture was bubbled and neutralized with BES as described above, and bicarbonate (final 8 mm concentration) was then added to one set of samples, followed by reaction initiation with CO2-free KH2 (2.5 mm final concentration). After a 4-h incubation at 21 °C, the samples were removed from the glove bag, and 10-μl aliquots were withdrawn for measuring vitamin K epoxidation. These aliquots were added to tubes containing 140 μl water, 500 μl of 1:1 ethanol/hexane, and 15 μl of a K25 standard (2 nmol; GL Synthesis) that monitored recovery. The samples were vortexed, the organic phase was removed under nitrogen, and the vitamin K epoxide product was quantitated by HPLC and absorbance, as before (22). To assay the release of tritium from FL-[R,S-3H]EEL, the remaining samples underwent Thunberg distillation, as before (27). All samples were assayed in duplicate.

A separate set of reactions was also performed over a range of CO2 concentrations (0–8 mm), and in this experiment, parallel reactions were performed to determine Gla formation. In the parallel reactions, FLEEL replaced FL-[R,S-3H]EEL in the mixture, and trace (<5 μm) levels of FL-[14C]EEL were included to monitor recovery. Acetone precipitation and P-2 chromatography were performed as described above to isolate the peptide mixture (i.e. FLEEL, FLγEL, and FL-[14C]EEL), which was located by scintillation counting. After lyophilization, peptides were base-hydrolyzed and derivatized with o-phthalaldehyde, and Gla was quantitated by HPLC and fluorescence, as before (34). The values were adjusted for recovery determined by quantitating both aliquots of the starting reaction mixture and [14C]Glu fractions eluting from the column during HPLC. All assays were performed in duplicate.

Measuring Glu Reprotonation

Incorporation of tritium from solvent into Glu was measured by performing duplicate reactions (170 μl) in a mixture containing tritiated water (final specific activity ∼0.4 mCi/ml; Moravec Biochemicals, Inc.), 2.5 mm FLEEL, buffer (25 mm MES, pH 5.5, followed by neutralization to pH 6.9 with 80 mm BES, pH 7.25 after degassing), 2 mm KH2, carboxylase (∼150 nm), trace amounts (<5 μm) of KFL-[14C]EEL, and core reaction mixture. After 4 h at 21 °C, aliquots (10 μl) were removed to measure vitamin K epoxidation as described above. The remainder of the sample was added to a vial with 2 ml of water and then boiled to 200 μl to eliminate most of the tritiated water. After the addition of 800 μl of acetone and incubation on ice for 1 h, the samples were centrifuged (10,000 × g, 4 °C, 15 min) and then chromatographed on P-2 columns, which separated any remaining tritiated water from peptide. Fractions containing peptide (i.e. KFL-[14C]EEL, FLEEL, and FLγEL) were detected by scintillation counting and lyophilized to dryness. The samples were analyzed by HLPC on a C18 Hypersil column with 25 mm ammonium acetate, pH 8.5, and 15% (v/v) acetonitrile as the mobile phase, and the FLEEL fractions were collected and counted for the presence of tritium. The KFL-[14C]EEL fraction was well resolved from FLEEL and was also collected, and scintillation counting was performed to correct the tritium counts for recovery loss during peptide isolation. FLγEL peptide was also quantitated by absorbance in some experiments to determine the extent of Gla formation.

Glu reprotonation by deuterium was also monitored. Carboxylase was purified as described above but using reagents prepared in deuterium oxide, and a control carboxylation assay was performed that showed that the enzyme had a normal specific activity. The reaction to measure Glu reprotonation was then performed as described above, except that tritiated water was replaced by D2O, which was used to prepare all of the reaction components. The FLEEL peptide was isolated by HPLC and then quantitated for deuterium incorporation using liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy on a Finnigan LTQ linear ion trap system. The amount of deuterated FLEEL was compared with a standard curve containing increasing amounts of FL-[R,S-2H]EEL mixed with FLEEL, giving a final concentration of 1 μm peptide for each sample. The FL-[R,S-2H]EEL was synthesized as described previously (27), except that D2O replaced T2O. When FLEEL alone was analyzed, the theoretical value predicted for natural isotopic abundance was within 1% of the observed value, validating the instrumentation used in this approach.

Inhibition of Carboxylase Reactions by Cyanide

Carboxylation reactions containing [14C]bicarbonate, 2.5 mm FLEEL, 50 mm BES, pH 6.9, carboxylase (25 nm), KH2 (2 mm), and core reaction mixture were performed over a range of cyanide concentrations (0–10 mm). After 1 h at 21 °C, the reactions were quenched by the addition of 1 ml of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid, followed by boiling to remove [14C]CO2, and [14C]CO2 incorporation into peptide substrate was then quantitated by scintillation counting. The effects of cyanide on Glu deprotonation and reprotonation were also determined. The assays were performed exactly as described above except for the inclusion of cyanide. A cyanide stock (340 mm) was sparged with nitrogen in the glove bag for 2 h prior to addition to the reaction mixture.

RESULTS

Elimination of Endogenous CO2 from Carboxylase Reactions

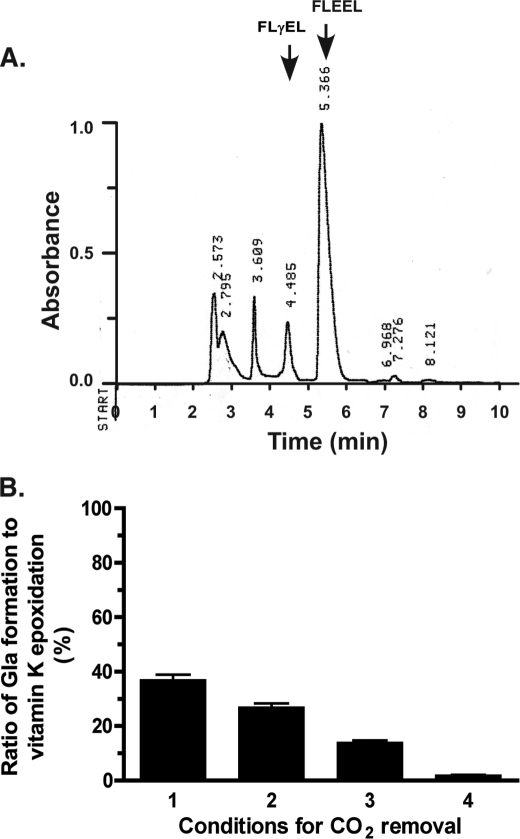

Initial experiments revealed a complication by endogenous CO2 because high levels of carboxylation were observed in the absence of exogenously added CO2 (i.e. 37% Gla formation compared with vitamin K epoxidation; Fig. 3). Previously, lyophilization of microsomes was used to reduce the endogenous CO2 concentration to trace levels (∼0.1 mm) (35, 36). Lyophilization resulted in inactivation of purified carboxylase (not shown), so we sought an alternative method for removing endogenous CO2. When reaction mixtures that contained carboxylase were either gassed with a mixture of nitrogen/oxygen over the headspace or bubbled directly in solution, significant carboxylation was still observed (27 and 14% compared with vitamin K epoxidation; Fig. 3B). However, when the reaction mixture was first bubbled at pH 5.5 to eliminate bicarbonate and carbonate by conversion to CO2 and then reacted at the normal pH (i.e. pH 6.9), all in a glove bag under a nitrogen/oxygen atmosphere, carboxylation was almost undetectable (Fig. 3B). These conditions were therefore used in the subsequent studies.

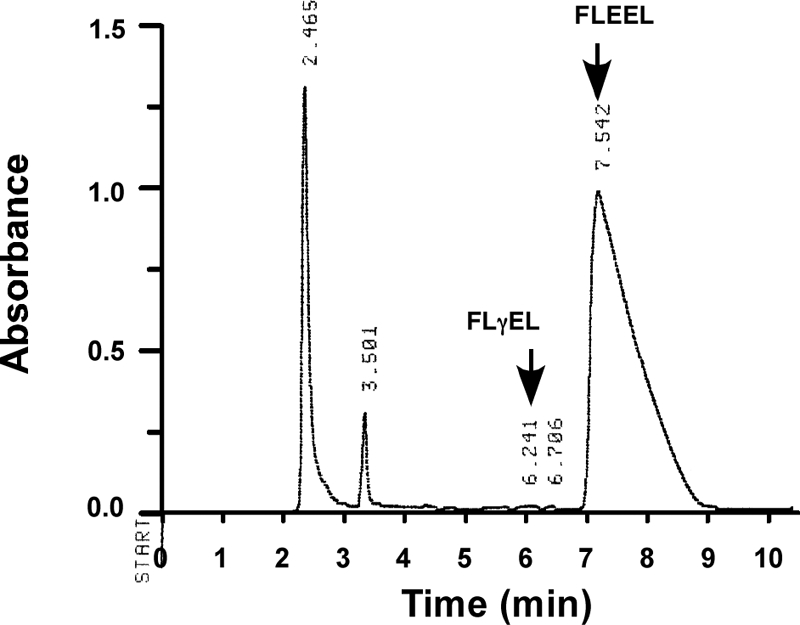

FIGURE 3.

Removal of endogenous CO2 from carboxylase reaction mixtures. A, Gla formation is usually quantitated by a radioactivity assay that measures [14C]CO2 incorporation into Glu-containing substrate; however, this assay can be confounded by the presence of endogenous CO2, and we therefore developed an alternative method for quantitating Gla. Reactions were performed and then chromatographed on P-2 columns to isolate peptide and remove interfering substances. HPLC was then used to separate the carboxylated product (FLγEL) from FLEEL substrate. The FLγEL peptide was hydrolyzed with base, and Gla was derivatized with o-phthalaldehyde and quantitated using HPLC and fluorescence detection. An example of the resolution of FLγEL and FLEEL by HPLC is shown. B, analysis of reaction mixtures without exogenously added CO2 revealed significant levels of carboxylation due to endogenous CO2 (lane 1). Gassing the samples with a 1:1 mixture of nitrogen and oxygen, either over the headspace in a sealed vial (lane 2) or directly in the sample (lane 3) reduced but did not eliminate Gla formation. When the samples were gassed in the sample at pH 5.5 and then adjusted to pH 6.9 and reacted, carboxylation was barely detectable (lane 4). Error bars, S.E.

Glu Deprotonation Is Dependent upon the Presence of CO2

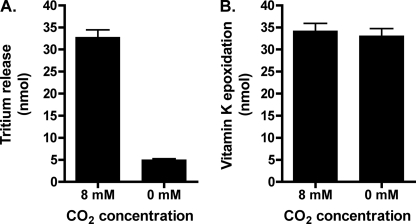

The effect of CO2 on Glu deprotonation was assessed using purified carboxylase (Fig. 2) and a direct method that measures the release of tritium from the γ-carbon position of Glu into water. A peptide substrate containing the tritiated Glu was generated by performing heat decarboxylation on a Gla-containing peptide (FLγEL) in the presence of T2O, which results in specific incorporation of tritium at the γ-carbon of Glu (33). When this FL-[R,S-3H]EEL substrate was reacted with carboxylase in the presence or absence of CO2, a substantial decrease in the amount of tritium release was observed in the absence of CO2 (Fig. 4A). This result is markedly different from that reported with crude microsomes, where the extent of tritium release was identical in the presence or absence of CO2 (26). Vitamin K epoxidation was unaffected by CO2 (Fig. 4B), consistent with previous results of others (37).

FIGURE 4.

CO2 impacts the level of Glu deprotonation. Wild type carboxylase was incubated in reaction mixtures containing a peptide substrate with Glu tritiated at the γ-carbon position (FL-[R,S-3H]EEL), either in the presence or absence of CO2, and the release of tritium to solvent was measured (A). Aliquots of each reaction were also withdrawn to determine the level of vitamin K epoxidation (B). Error bars, S.E.

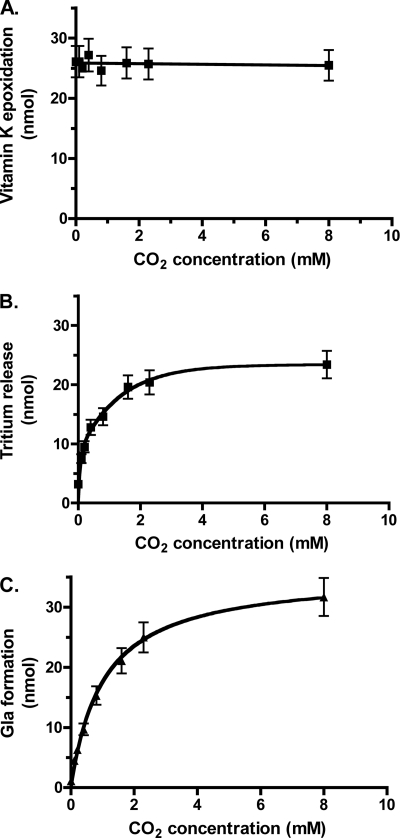

To further define the dependence of carboxylase activity on the presence of CO2, we measured tritium release in parallel with Gla formation over a range of CO2 concentrations. The results were striking in showing that not only does tritium release depend strongly upon CO2, but tritium release parallels the generation of Gla (Fig. 5, B and C). In the absence of CO2, a small amount of tritium release was observed (12% compared with the level of vitamin K epoxidation; Fig. 5, A and B), even though Gla formation was almost undetectable (Fig. 5C). Vitamin K epoxidation was unaffected by the concentration of CO2 (Fig. 5A), consistent with the results in Fig. 4B.

FIGURE 5.

Glu deprotonation and Gla formation show proportional increases over a range of CO2 concentrations. Reactions were performed using carboxylase, FL-[R,S-3H]EEL, KH2, and the indicated concentrations of CO2. At the end of the reaction, aliquots were withdrawn to determine the level of vitamin K epoxidation (A), and the remainder of the reaction mixtures was used to measure the release of tritium from peptide into solvent (B). To monitor Gla formation (C), a separate set of reactions was also performed in which FL-[R,S-3H]EEL was replaced by FLEEL. Vitamin K epoxidation was measured as above and gave values that were essentially the same as those shown in A. Peptide product (FLγEL) isolated from the remaining reaction mixture was base-hydrolyzed, and Gla was quantitated using HPLC and fluorescence detection. The lines in B and C were fit using GraphPad Prism (version 4.0), and the details for the assays are described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars, S.E.

Glu Reprotonation with Purified Carboxylase Is Almost Undetectable

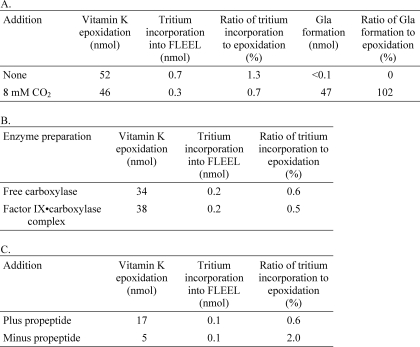

To more fully understand the dependence of Glu deprotonation on CO2, Glu reprotonation was also investigated. This study was carried out because previous studies using crude microsomes as the source of carboxylase showed that when CO2 concentrations are low (0.1–0.2 mm), the Glu substrate incorporates substantial amounts of tritium from solvent (35, 36), which indicates two alternative fates of the carbanion (i.e. carboxylation or reprotonation) (Scheme 1). Reactions with purified carboxylase were performed in the presence or absence of added CO2, and the FLEEL peptide was then isolated and quantitated for the incorporation of tritium. When CO2 was present, very little tritium incorporation into peptide was observed (i.e. 0.7% of the level of vitamin K epoxidation) (Table 1A). This result was as expected because at this saturating concentration of CO2, all of the Glu should be carboxylated, consistent with the 1:1 stoichiometry of Gla formation and vitamin K epoxidation that was observed (Table 1A). Interestingly, very little tritium incorporation occurred even when CO2 was absent and carboxylation of the FLEEL peptide was undetectable (Table 1A and Fig. 6). The ratio of tritium incorporation to vitamin K epoxidation (1.3%) was much lower (15-fold) than that previously reported using microsomal preparations of carboxylase (36).

SCHEME 1.

Alternative consequences of Glu deprotonation.

TABLE 1.

Very low levels of Glu reprotonation are observed in the absence of CO2

A, as described in detail under “Experimental Procedures,” carboxylase reactions containing T2O were performed in the presence or absence of CO2. At the end of the reaction, an aliquot was removed to determine vitamin K epoxidation, and the remaining samples were chromatographed over P-2 columns, followed by HPLC to separate FLγEL from FLEEL (as in Fig. 3A). FLγEL was quantitated by absorbance to determine Gla formation, and FLEEL was collected and quantitated for tritium incorporation by scintillation counting. Trace amounts of KFL-[14C]EEL were used to monitor peptide recovery. The reactions were performed in duplicate, and the averages are shown. B, carboxylase that was either free or bound to factor IX was reacted in the absence of CO2, and the samples were then processed as in A, except that propeptide was not included in the reaction. Gla formation was undetectable in both reactions (not shown). C, carboxylase reactions were performed in the absence of CO2, and the products were analyzed as described in A, except that propeptide was omitted in one set of reactions.

FIGURE 6.

FLEEL carboxylation is undetectable in the absence of CO2. Reactions containing T2O but no added CO2 were performed, and peptide was isolated using P-2 chromatography followed by HPLC, which showed that very little carboxylation and generation of FLγEL product occurred (e.g. compare with Fig. 3A). The FLEEL peptide was collected and subjected to scintillation counting to determine the amount of tritium incorporation due to Glu reprotonation. The elution time for the FLEEL peptide is different from that shown in Fig. 3A due to the use of different mobile phases.

One possible explanation for the difference in Glu reprotonation in these studies versus the previous ones could be the use of different enzyme forms. Thus, in the liver microsomal preparations, the carboxylase is bound to VKD proteins (38), and more recent studies indicate that release of VKD proteins is extremely slow in vitro even when the VKD proteins are fully carboxylated (39). Consequently, tritium incorporation into Glu substrate was mediated by a carboxylase-VKD protein complex in the previous study versus free carboxylase in the current experiments. The access of solvent into the active site may not be the same for both preparations, and we therefore tested tritium incorporation into Glu-containing substrate using a carboxylase-VKD protein complex.

To generate complex, insect cells were coinfected with baculoviruses containing the carboxylase and VKD protein factor IX, and complex formation was assessed by immunoprecipitation with antibodies against either factor IX or the FLAG epitope on the carboxylase. Quantitation of carboxylase and factor IX showed that the amount of factor IX (127 nm) was about 3-fold higher than that of the carboxylase (44 nm). Only a portion of the factor IX (21%) was adsorbed to the anti-FLAG resin that bound the carboxylase (Table 2A), consistent with the factor IX being in excess. In contrast, most of the carboxylase (86%) was retained on the anti-factor IX resin. This adsorption was dependent upon factor IX, because incubation of anti-factor IX resin with solubilized microsomes from insect cells expressing the carboxylase but not factor IX did not result in carboxylase binding (data not shown). These data show that most of the carboxylase in the coinfected cells is in a complex with factor IX. Large amounts of complex were subsequently isolated by immunopurification on anti-FLAG resin. The eluant contained similar levels of factor IX and carboxylase (9 and 7 pmol, respectively), and complex was shown to be stable to isolation, as assessed by immunoadsorption of an aliquot of the eluant on anti-factor IX antibody resin (Table 2B).

TABLE 2.

Carboxylase in insect cells co-expressing factor IX exists largely as a factor IX-carboxylase complex

A, immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments were performed to determine factor IX-carboxylase complex formation in insect cells expressing both proteins. Solubilized microsomes (the “start” samples) were incubated with immobilized antibody against factor IX or the FLAG epitope appended to the carboxylase C terminus. Adsorbed protein was then determined using either washed resin (in the anti-factor IX immunoprecipitation) or material eluted from the resin (in the anti-carboxylase-FLAG immunoprecipitation). Carboxylase was quantitated by an activity assay, and factor IX was quantitated by combined Western/LI-COR analysis. Factor IX bound to anti-factor IX resin was not observable because antibody leaching obscured the factor IX in Western analysis. B, eluant from an anti-carboxylase-FLAG IP was also tested for the stability of the carboxylase-factor IX complex by subjecting an aliquot of the eluant to an anti-factor IX immunoprecipitation. All assays were performed in duplicate, and the average values are shown, where the range of values was within 10% of the mean.

The ability of tritium from solvent to access the active site of carboxylase in a complex and result in Glu reprotonation was then tested. Complex and free carboxylase were assayed in parallel and, as shown in Table 1B, the results were similar for the two different enzyme preparations, which both gave low levels of tritium incorporation into the FLEEL peptide. Thus, the discrepancy in results with purified versus microsomal carboxylase is not due to the use of different forms of enzyme.

Tritium incorporation was also measured using carboxylase that was only partially active. Full activity requires the presence of the propeptide in VKD proteins that mediates their tight association with the carboxylase. To determine whether higher levels of Glu reprotonation occurred with partially active carboxylase, tritium incorporation was monitored in reactions that contained or lacked propeptide. As can be seen in Table 1C, Glu reprotonation was still low, at a level about 10-fold less than that observed with microsomal carboxylase (36). The combined results indicate that the alternative fate of reprotonation (Scheme 1) previously proposed for microsomal carboxylase (35) is used far less frequently by purified enzyme.

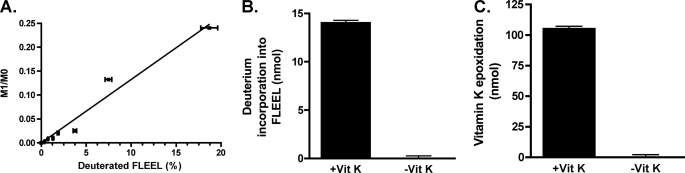

Differences in Tritium Release and Tritium Incorporation Are Due to an Isotope Effect

Deuterium incorporation into Glu was measured in order to assess why tritium release was much higher than the amount of tritium incorporation. Thus, Glu deprotonation results in either carboxylation to form Gla or reprotonation to regenerate Glu (Scheme 1), so the amount of tritium release should equal the sum of the observed Gla formation and tritium incorporation into Glu. However, in the absence of added CO2 and detectable Gla formation, tritium release was 12% (Fig. 5), whereas tritium incorporation was only 1.3% (Table 1). This discrepancy could be due to isotope effects, which should be different for tritium release and tritium incorporation. Tritium release occurs stereospecifically (40, 41), so only one possible position reacts on a given molecule. In contrast, tritium incorporation can come from one of two sites on a water molecule, and because most of the tritiated water existed as TOH rather than T2O, carbanion reprotonation could discriminate against tritium in favor of protium by the rotation of water in the active site (Scheme 2). We therefore measured Glu reprotonation in a reaction where virtually all of the water existed as D2O, so that the carbanion could only be reprotonated by deuterium (Scheme 2). The carboxylase purification and reaction were performed using reagents prepared in D2O, and the amount of deuterium incorporation into the FLEEL substrate was monitored by mass spectroscopy. Comparison with a standard curve composed of different amounts of FLEEL and FL-[R,S-2H]EEL indicated a level of deuterium incorporation that was 13% that of vitamin K epoxidation (Fig. 7). This level was substantially higher than the amount of tritium incorporation (Table 1) and was essentially the same as that of tritium release (Fig. 5). The results indicate that the difference in amounts of tritium release and tritium incorporation is due to an isotope effect.

SCHEME 2.

Glu reprotonation in deuterium oxide or tritiated water.

FIGURE 7.

Measuring Glu reprotonation in a deuterium-containing reaction. A, to establish a standard curve for quantitating the amount of deuterium incorporation into FLEEL, increasing amounts of FL-[R,S-2H]EEL were mixed with FLEEL to give final concentrations of 1 μm peptide, and the samples were then analyzed by mass spectroscopy. M0, area under the curve measured for the most abundant isotopic forms (e.g. 1H and 12C); M1, those that are one mass unit higher (e.g. 2H and 13C). The M1/M0 ratio has been adjusted to account for the natural abundance of isotopes in FLEEL. B, FLEEL was carboxylated in the presence or absence of vitamin K hydroquinone (vit K) in reaction mixtures where all of the components were prepared in D2O. The amount of deuterium incorporation into FLEEL was quantitated by mass spectroscopy and a comparison with the standard curve shown in A. C, an aliquot of the reaction was also quantitated for vitamin K epoxidation. Error bars, S.E.

Stimulation of Glu Reprotonation by Cyanide

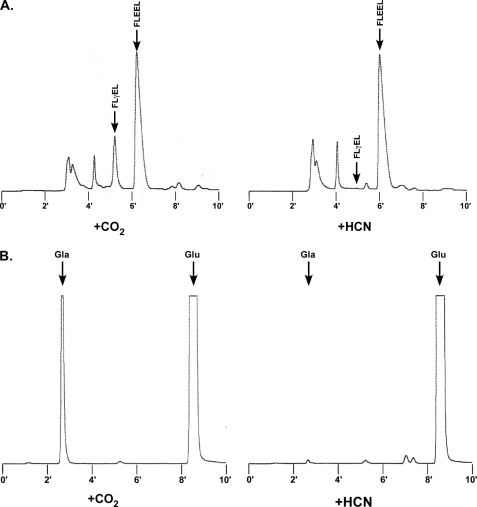

Cyanide competes with CO2 for binding by the carboxylase (42) and therefore can access the active site. The pKa of cyanide is 9.3, so most (∼99%) of the cyanide will exist in a protonated form (i.e. HCN) that could potentially react with the carbanion. We therefore determined whether cyanide had an effect on Glu reprotonation. A dose-response experiment with cyanide was first performed on wild type carboxylase (Fig. 8A), which showed 90% inhibition of activity at the highest concentration tested (10 mm KCN). To monitor the effect of cyanide on Glu reprotonation, wild type carboxylase was incubated in a reaction mixture containing tritiated water and KCN, which generates TCN, and tritium incorporation into Glu-containing peptide was monitored along with vitamin K epoxidation and Gla formation. Control reactions were also performed in which KCN was either omitted or substituted by CO2. The peptide products were isolated using HPLC, which showed that cyanide abolished Gla formation (Fig. 9A). When tritium incorporation into Glu was monitored in the presence or absence of CO2, very little tritium was observed (Table 3), as before (Table 1). Cyanide caused a 9-fold stimulation in the ratio of tritium incorporation to vitamin K epoxidation by wild type carboxylase (Table 3). Tritium incorporation into the FLEEL peptide occurred specifically in a Glu residue, as shown by peptide hydrolysis followed by amino acid separation and quantitation using HPLC and scintillation counting (data not shown). Cyanide also stimulated vitamin K epoxidation, and the response was similar to that previously reported (43).

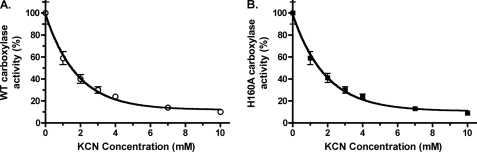

FIGURE 8.

Cyanide inhibition of carboxylase activity. Wild type (WT) carboxylase (A) and an H160A mutant (B) were each incubated in a reaction mixture containing FLEEL, KH2, [14C]bicarbonate, and increasing concentrations of KCN, and Gla formation was determined by measuring the incorporation of [14C]CO2 into FLEEL by scintillation counting. The lines were fit using GraphPad Prism (version 4.0). Error bars, S.E.

FIGURE 9.

Measuring the effects of cyanide on Glu reprotonation and Gla formation. A, to measure Glu reprotonation, reactions were performed with mixtures containing the wild type carboxylase, FLEEL, KH2, tritiated water, and either CO2 or cyanide. The peptides were isolated by P-2 chromatography and then HPLC, which showed that cyanide abolished carboxylation (i.e. generation of the FLγEL product). The FLEEL peptide was collected and quantitated for tritium incorporation by scintillation counting. B, to assess the effect of cyanide on Gla formation, reactions were performed as in A but without T2O. The FLγEL product was isolated as in A and subjected to base hydrolysis and o-phthalaldehyde derivatization, followed by HPLC and fluorescence detection to quantitate Gla, Glu, and Phe/Leu (not shown in the chromatogram). The details of these assays are described under “Experimental Procedures.”

TABLE 3.

Measuring the effect of cyanide on Glu reprotonation

Incorporation of tritium into Glu was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 9A. Aliquots were also quantitated for vitamin K epoxidation. A control reaction lacking KH2 was performed, and the background in the HPLC fractions (∼60 cpm total) was subtracted from the test samples to give the cpm of tritium incorporation that are shown. The wild type and H160A carboxylase reactions were analyzed on separate days, and the TOH-specific activity was 334 cpm/pmol and 256 cpm/pmol in the respective reactions. The average of duplicate samples is shown, and the entire experiment was performed twice, giving similar results.

| Carboxylase variant | Addition | Vitamin K epoxidation | Tritium incorporation | Ratio of tritium incorporation to epoxidation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol | cpm | nmol | % | ||

| Wild type | None | 32 | 128 | 0.4 | 1 |

| 8 mm CO2 | 36 | 35 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| 10 mm HCN | 43 | 1295 | 3.9 | 9 | |

| H160A | None | 27 | 40 | 0.2 | 1 |

| 8 mm CO2 | 28 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| 10 mm HCN | 33 | 72 | 0.3 | 1 | |

A mutant with His-160 substituted by Ala, H160A, shows impaired Glu deprotonation and normal vitamin K epoxidation (27), similar to how wild type carboxylase reacts in the absence of CO2, and we therefore also tested the effect of cyanide on Glu reprotonation in the H160A mutant. Cyanide was tested at the same concentration used for wild type enzyme, because H160A activity responded similarly to that of wild type carboxylase when tested with KCN (Fig. 8). When H160A was incubated with tritiated water in control reactions lacking cyanide, the results with H160A were similar to that of wild type enzyme, with very little tritium incorporation being observed in the presence or absence of CO2 (Table 3). However, H160A responded differently than wild type enzyme to cyanide: the amount of cyanide stimulation was much smaller with H160A, resulting in a ratio of tritium incorporation to vitamin K epoxidation of 1% versus 9% for wild type carboxylase.

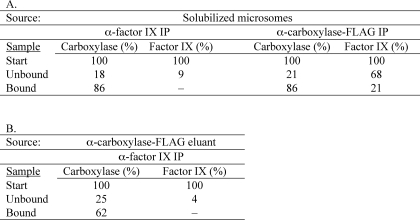

Cyanide Stimulates Glu Deprotonation in Wild Type but not H160A Carboxylase

The effect of cyanide on tritium release was also measured to determine if cyanide, like CO2, can stimulate Glu deprotonation. Wild type carboxylase was incubated with FL-[R,S-3H]EEL in the presence or absence of cyanide and/or CO2, and tritium release to water was measured in parallel with Gla formation and vitamin K epoxidation. In the absence of added CO2 or cyanide, wild type carboxylase showed some Glu deprotonation but only trace levels of Gla formation (Table 4), as before (Fig. 5). Cyanide stimulated Glu deprotonation, resulting in an increase in the ratio of tritium release to epoxidation from 17% (in the absence of CO2) to 26% (in the presence of cyanide) (Table 4). The increase in Glu deprotonation was not accompanied by Gla formation, indicating carbanion protonation rather than carboxylation (Scheme 1). The amount of stimulation by cyanide was similar to the increase in the incorporation of tritium from solvent into Glu-containing substrate caused by cyanide (Table 3). The effect of cyanide on tritium release was less than that of CO2, which caused levels of tritium release that were almost equivalent (95%) to the amount of vitamin K epoxidation (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Cyanide stimulates Glu deprotonation in wild type but not H160A carboxylase

Two sets of reactions were performed that measured either tritium release from FL-[R,S-3H]EEL to water or Gla formation, which was assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 9B. Vitamin K epoxidation was measured in both reactions and was essentially the same for both sets of assays. The values shown are the average of duplicate samples, and the entire experiment was performed twice.

| Carboxylase variant | Addition | Vitamin K epoxidation | Tritium release | Ratio of tritium release to epoxidation | Gla formation | Ratio of Gla formation to epoxidation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol | cpm | nmol | % | nmol | % | ||

| Wild type | None | 52 | 856 | 8.7 | 17 | 0.9 | 2 |

| 8 mm CO2 | 48 | 4467 | 45.6 | 95 | 39.0 | 81 | |

| 10 mm HCN | 55 | 1396 | 14.2 | 26 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| 8 mm CO2 + 10 mm HCN | 54 | 3282 | 33.5 | 62 | 16.1 | 30 | |

| H160A | None | 25 | 30 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 8 mm CO2 | 25 | 158 | 1.6 | 6 | 1.8 | 7 | |

| 10 mm HCN | 31 | 34 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| 8 mm CO2 + 10 mm HCN | 27 | 86 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.8 | 3 | |

The H160A mutant showed a different response to cyanide than wild type enzyme, exhibiting levels of tritium release that were the same (1%) in the absence of CO2 or presence of cyanide (Table 4). H160A also differed from wild type enzyme in showing a significantly lower ratio of tritium release to vitamin K epoxidation (i.e. 17-fold) in the absence of added CO2. Incubation of H160A with CO2 resulted in some stimulation of tritium release and a corresponding increase in Gla formation. The ratio of tritium release in the presence of CO2 was 16-fold less for H160A than wild type enzyme, similar to results reported previously (27) and consistent with the role of His-160 in Glu deprotonation.

Because cyanide is a competitive inhibitor of CO2 (42), mixing experiments were performed to measure Glu deprotonation in the presence of both CO2 and cyanide. In wild type carboxylase, cyanide blocked the effect of CO2, resulting in both impaired tritium release (from 95% to 62% relative to vitamin K epoxidation) and Gla formation (from 81 to 30%) (Table 4). H160A also showed a decrease in both reactions in response to cyanide. This inhibitory effect of cyanide with both wild type and mutant enzymes suggests that cyanide can stimulate Glu deprotonation but causes a decrease when CO2 is present because it is less effective than CO2 for Glu deprotonation.

DISCUSSION

The carboxylation of Glu to Gla involves Glu deprotonation, and the studies here provide important insight into Glu deprotonation that has mechanistic implications for how the carboxylase catalyzes the reaction. A key observation was the dependence of Glu deprotonation on CO2. When tritium release from the glutamyl γ-carbon position was used to measure Glu deprotonation, substantially more release was observed in the presence than in the absence of CO2 (Fig. 4). In addition, analysis over a range of CO2 concentrations showed a proportional increase in both the release of tritium and the formation of Gla (Fig. 5). Thus, Glu deprotonation does not occur unless CO2 is present. Previous studies (35) indicated an alternative fate of deprotonated Glu, which is reprotonation by water (Scheme 1); however, our results indicate that reprotonation is infrequent. When CO2 was absent, the amount of reprotonation by TOH in tritiated water or D2O was only 1% (Tables 1 and 3) or 13% (Fig. 7) that of vitamin K epoxidation, respectively, with the difference being due to an isotope effect because reprotonation can discriminate between tritium and hydrogen in TOH (Scheme 2). The consequence of infrequent Glu reprotonation is a more efficient carboxylation reaction. It should be noted that the carboxylase must have a mechanism to prevent water from accessing the active site. The vitamin K base (K− in Fig. 1) is also vulnerable to quenching by water, but reprotonation does not occur, as evidenced by the 1:1 stoichiometry of vitamin K epoxidation and Glu deprotonation in wild type carboxylase when CO2 is present (Figs. 4 and 5 and Table 4).

The dependence of Glu deprotonation on CO2 contrasts with previously reported results (26), where tritium release was independent of CO2 and occurred in a 1:1 stoichiometry with vitamin K epoxidation even at low concentrations of CO2 (0.2 mm), where very little Gla formation was detected. This discrepancy in results obtained with purified enzyme (in the current study) and crude microsomes (in the previous one) is most likely due to differences in solvent accessibility. Thus, microsomal preparations of carboxylase show an additional difference from purified enzyme, which is a substantially higher ratio of Glu reprotonation by tritium to vitamin K epoxidation (i.e. 20% (36) versus 1% for purified enzyme (Table 1)). The large amount of tritium incorporation with microsomal carboxylase is more than sufficient to account for the observed 100% tritium release in the absence of CO2 (26), because an isotope effect causes ∼10-fold higher levels of tritium release than tritium incorporation (Tables 1 and 4 and Figs. 5 and 7). High solvent accessibility in microsomal carboxylase thus masked the dependence of Glu deprotonation on CO2.

Why purified carboxylase and microsomes show differences in access of water into the active site is not known. As presented under “Results,” the form of the carboxylase in microsomes is probably a complex between the carboxylase and VKD proteins; however, we observed low levels of Glu reprotonation using either free carboxylase or carboxylase-factor IX complex (Table 1), so the use of different forms of the carboxylase cannot explain why solvent accessibility is higher in microsomes. One possible explanation for the difference is the method used to remove CO2 (i.e. lyophilization of microsomes versus bubbling purified carboxylase with nitrogen in an aqueous environment). Dehydration by lyophilization may perturb the structure of the membrane or the topology of the carboxylase, which is an integral membrane protein, allowing water access into the active site.

The occurrence of Glu deprotonation in the presence of water is informative with regard to the role of CO2. The dependence of Glu deprotonation on CO2 (Figs. 4 and 5) could be due to either a regulatory role or catalytic involvement of CO2 in deprotonation. The effect of CO2 in a regulatory role would be indirect, with CO2 binding impacting the structure of the active site to promote Glu deprotonation. Alternatively, CO2 may be directly involved in the chemistry of the reaction. The proton on the glutamyl γ-carbon has a very high pKa (∼26); however, absorption of the developing negative charge on the γ-carbon by CO2 would reduce the pKa, facilitating deprotonation (Fig. 10). Kinetic analysis indicates that CO2 is either the first or last substrate to bind (44), and CO2 must bind last because vitamin K epoxidation occurs in the absence of CO2 (Figs. 4 and 5), which suggests chemical involvement rather than regulation. A regulatory role is unlikely because water has a structure different from that of CO2 and so would not be predicted to engage in the same non-covalent interactions as CO2 to correctly organize the active site. In contrast, a catalytic role is an attractive possibility because both water and CO2 can act as Lewis acids to accept electrons from the γ-carbon, so water could replace the function of CO2. The combined data indicating that Glu deprotonation depends upon CO2 but also occurs when water is present therefore strongly suggest that CO2 is chemically involved in accepting the charge (Fig. 10). This role indicates a concerted mechanism of carboxylation in which Glu deprotonation and CO2 addition occur simultaneously.

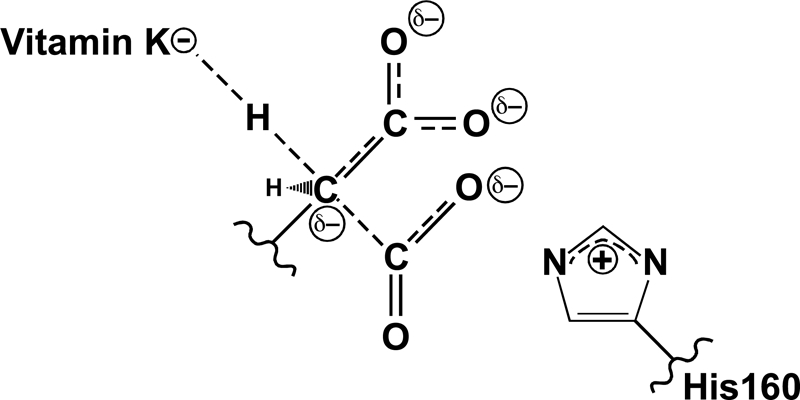

FIGURE 10.

A concerted mechanism for Gla formation. Previous studies showed that His-160 is required for Glu deprotonation (27), and the present studies reveal that CO2 is also required. Water and cyanide can both substitute for CO2 in supporting Glu deprotonation, which, as detailed under “Discussion,” strongly suggests a chemical role for CO2. This function is most likely the dispersal of charge that develops on the glutamyl γ-carbon during deprotonation by the vitamin K base. Thus, Glu deprotonation and CO2 addition occur simultaneously in a concerted mechanism of carboxylation. Reactivity of the mutant H160A carboxylase toward CO2 and cyanide suggests that His-160 facilitates Glu deprotonation through interaction with CO2.

The effect of cyanide on Glu deprotonation and reprotonation is consistent with the proposed mechanism. Cyanide has previously been shown to be a competitive inhibitor of CO2 (42) and blocks carboxylation (Table 4 and Figs. 8 and 9), and cyanide can donate a hydrogen for carbanion protonation. However, in contrast to water, HCN brings only one proton into the active site, so carbanion protonation by cyanide in tritiated water should not show an isotope effect. Consequently, unlike water, where large differences in tritium incorporation and tritium release were observed, the effects of cyanide would be predicted to be the same for both reactions, which is what was observed. Cyanide stimulated tritium incorporation into Glu with wild type carboxylase, resulting in a 9% level compared with vitamin K epoxidation versus 1% in the absence of CO2 (Table 3). Cyanide also caused a 9% increase in the ratio of tritium release to vitamin K epoxidation over that observed in the absence of CO2 (Table 4), which must be due to Glu reprotonation because Gla formation was almost undetectable. The results indicate that cyanide, like water, can substitute for CO2 in allowing Glu deprotonation, supporting the model that CO2 plays a chemical role in a concerted mechanism (Fig. 10).

These new results are of interest with regard to how His-160 facilitates Glu deprotonation. We had previously proposed that His-160 interacts with the glutamyl carboxylate group to stabilize the aci-carboxylate (27), because at that time Glu deprotonation was thought to be independent of CO2 addition. However, a concerted mechanism raises the possibility that His-160 may instead interact with CO2 to stabilize the negative charge that develops as CO2 reacts with the γ-carbon (Fig. 10). This role would be consistent with the fact that His-160 is not part of the known Glu-binding site (i.e. residues ∼390–400) (45) and with the previous kinetic analysis of the H160A carboxylase mutant, which revealed an increase in Km for CO2 (27). It would also be consistent with the effect of cyanide on the reaction. Cyanide stimulation of Glu reprotonation was much lower with the H160A mutant than that observed with wild type carboxylase (Table 3). H160A also differed from wild type enzyme in not showing any stimulation of Glu deprotonation by cyanide (i.e. over that observed in the absence of CO2) (Table 4). However, in the presence of CO2, cyanide decreased Glu deprotonation and Gla formation in the H160A and wild type enzymes (Table 4 and Fig. 8), which indicates that in both enzymes, cyanide binds in the site normally occupied by CO2. Cyanide binding and inability to stimulate Glu deprotonation in H160A therefore suggest that His-160 interacts with CO2 and, when cyanide is present, can stabilize the HCN species as well. His-160 neutralization of the negatively charged −CN that is formed may facilitate cyanide stimulation of Glu deprotonation. The combined results therefore suggest that His-160 interacts with CO2 and facilitates Glu deprotonation by adsorbing the negative charge that develops on CO2 as it reacts with the glutamyl γ-carbon (Fig. 10).

Our studies implicating a concerted mechanism provide insight into how the carboxylase catalyzes the reaction. The formation of a discrete carbanion intermediate in a stepwise reaction would require a high energy of activation, which is avoided in a concerted mechanism by the dispersal of negative charge using CO2. A concerted mechanism therefore lowers the activation energy needed to reach the transition state, thereby driving catalysis. His-160 facilitates this process, so the results presented here are also significant in further defining the carboxylase active site.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kurt Runge for helpful comments on the manuscript and Belinda Willard and Ling Li for performing the mass spectroscopy analysis on the deuterated peptide.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 HL055666 (to K. L. B.).

- VKD

- vitamin K-dependent

- Gla

- γ-carboxylated Glu

- KH2

- vitamin K hydroquinone

- FLγEL

- Phe-Leu-Gla-Glu-Leu

- BES

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]ethanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berkner K. L. (2005) Annu. Rev. Nutr. 25, 127–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morris D. P., Stevens R. D., Wright D. J., Stafford D. W. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30491–30498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stenina O., Pudota B. N., McNally B. A., Hommema E. L., Berkner K. L. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 10301–10309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brenner B., Sánchez-Vega B., Wu S. M., Lanir N., Stafford D. W., Solera J. (1998) Blood 92, 4554–4559 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Darghouth D., Hallgren K. W., Shtofman R. L., Mrad A., Gharbi Y., Maherzi A., Kastally R., LeRicousse S., Berkner K. L., Rosa J. P. (2006) Blood 108, 1925–1931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rost S., Fregin A., Koch D., Compes M., Muller C. R., Oldenburg J. (2004) Br. J. Haematol. 126, 546–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spronk H. M., Farah R. A., Buchanan G. R., Vermeer C., Soute B. A. (2000) Blood 96, 3650–3652 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhu A., Sun H., Raymond R. M., Jr., Furie B. C., Furie B., Bronstein M., Kaufman R. J., Westrick R., Ginsburg D. (2007) Blood 109, 5270–5275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berkner K. L. (2008) Vitam. Horm. 78, 131–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Q., Grange D. K., Armstrong N. L., Whelan A. J., Hurley M. Y., Rishavy M. A., Hallgren K. W., Berkner K. L., Schurgers L. J., Jiang Q., Uitto J. (2009) J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 553–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vanakker O. M., Martin L., Gheduzzi D., Leroy B. P., Loeys B. L., Guerci V. I., Matthys D., Terry S. F., Coucke P. J., Pasquali-Ronchetti I., De Paepe A. (2007) J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 581–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Czerwiec E., Begley G. S., Bronstein M., Stenflo J., Taylor K., Furie B. C., Furie B. (2002) Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 6162–6172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kulman J. D., Harris J. E., Nakazawa N., Ogasawara M., Satake M., Davie E. W. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15794–15799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olivera B. M., Gray W. R., Zeikus R., McIntosh J. M., Varga J., Rivier J., de Santos V., Cruz L. J. (1985) Science 230, 1338–1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bandyopadhyay P. K., Garrett J. E., Shetty R. P., Keate T., Walker C. S., Olivera B. M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1264–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang Y., Doolittle R. F. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 7527–7532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li T., Yang C. T., Jin D., Stafford D. W. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18291–18296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walker C. S., Shetty R. P., Clark K., Kazuko S. G., Letsou A., Olivera B. M., Bandyopadhyay P. K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7769–7774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang C. P., Yagi K., Lin P. J., Jin D. Y., Makabe K. W., Stafford D. W. (2003) J. Thromb. Haemost. 1, 118–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ren S. X., Fu G., Jiang X. G., Zeng R., Miao Y. G., Xu H., Zhang Y. X., Xiong H., Lu G., Lu L. F., Jiang H. Q., Jia J., Tu Y. F., Jiang J. X., Gu W. Y., Zhang Y. Q., Cai Z., Sheng H. H., Yin H. F., Zhang Y., Zhu G. F., Wan M., Huang H. L., Qian Z., Wang S. Y., Ma W., Yao Z. J., Shen Y., Qiang B. Q., Xia Q. C., Guo X. K., Danchin A., Saint Girons I., Somerville R. L., Wen Y. M., Shi M. H., Chen Z., Xu J. G., Zhao G. P. (2003) Nature 422, 888–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schultz J. (2004) Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 4–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rishavy M. A., Hallgren K. W., Yakubenko A. V., Zuerner R. L., Runge K. W., Berkner K. L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34870–34877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dowd P., Hershline R., Ham S. W., Naganathan S. (1995) Science 269, 1684–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tie J. K., Stafford D. W. (2008) Vitam. Horm. 78, 103–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rishavy M. A., Hallgren K. W., Yakubenko A. V., Shtofman R. L., Runge K. W., Berkner K. L. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 13239–13248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Friedman P. A., Shia M. A., Gallop P. M., Griep A. E. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 3126–3129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rishavy M. A., Berkner K. L. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 9836–9846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berkner K. L., McNally B. A. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 282, 313–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rishavy M. A., Pudota B. N., Hallgren K. W., Qian W., Yakubenko A. V., Song J. H., Runge K. W., Berkner K. L. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13732–13737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lingenfelter S. E., Berkner K. L. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 8234–8243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Finnan J. L., Suttie J. W. (1980) in Vitamin K Metabolism and Vitamin K-dependent Proteins (Suttie J. W., ed) pp. 509–517, University Park Press, Baltimore [Google Scholar]

- 32. Decottignies-Le Maréchal P., Rikong-Aide H., Azerad R., Gaudry M. (1979) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 90, 700–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hauschka P. V. (1979) Biochemistry 18, 4992–4999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berkner K. L. (1993) Methods Enzymol. 222, 450–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Anton D. L., Friedman P. A. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 14084–14087 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McTigue J. J., Suttie J. W. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 12129–12131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Larson A. E., Friedman P. A., Suttie J. W. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256, 11032–11035 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Metz M., Vermeer C., Soute B. A., van Scharrenburg G. J., Slotboom A. J., Hemker H. C. (1981) FEBS Lett. 123, 215–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hallgren K. W., Hommema E. L., McNally B. A., Berkner K. L. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 15045–15055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Decottignies-Le Maréchal P., Ducrocq C., Marquet A., Azerad R. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 15010–15012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dubois J., Gaudry M., Bory S., Azerad R., Marquet A. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 7897–7899 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. De Metz M., Soute B. A., Hemker H. C., Vermeer C. (1982) FEBS Lett. 137, 253–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dowd P., Ham S. W. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 10583–10585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Uotila L. (1988) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 264, 135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mutucumarana V. P., Acher F., Straight D. L., Jin D. Y., Stafford D. W. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46488–46493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]