Abstract

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CA9), a specific molecular marker for renal cell carcinoma (RCC), serves as a potential target for RCC-specific immunotherapy using dendritic cells (DCs). However, pulsing of DCs with CA9 alone is not sufficient for generation of a therapeutic anti-tumour immune response against RCC. In this study, in order to generate a potent anti-tumour immune response against RCC, we produced recombinant CA9-Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A (AbOmpA) fusion proteins, designated CA9-AbOmpA, and investigated the ability of DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins in a murine renal cell carcinoma (RENCA) model. A recombinant CA9-AbOmpA fusion protein was composed of a unique proteoglycan-related region of CA9 (1–120 amino acids) fused at the C-terminus with transmembrane domain of AbOmpA (1–200 amino acids). This fusion protein was capable of inducing DC maturation and interleukin (IL)-12 production in DCs. Interaction of DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins with naive T cells stimulated secretion of IL-2, interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α in T cells. Lymphocytes harvested from mice immunized with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins secreted IFN-γ and showed a specific cytotoxic activity against CA9-expressing RENCA (RENCA-CA9) cells. Administration of CA9-AbOmpA-pulsed DC vaccine suppressed growth of RENCA-CA9 cells in mice with an established tumour burden. These results suggest that DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins generate a specific anti-tumour immune response against RCC, which can be utilized in immunotherapy of RCC.

Keywords: AbOmpA, carbonic anhydrase IX, dendritic cells, immunotherapy, renal cell carcinoma

Introduction

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CA9), a member of the carbonic anhydrase family, is a membrane protein that regulates cell proliferation in response to hypoxia [1,2]. Expression of CA9 has been reported in tissues of many types of cancer, including kidney, uterine cervix, bladder, breast, oesophagus and colon [3–7]. CA9 is detected in >80% of primary and metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and >95% of clear cell RCC, whereas normal renal tissues do not express CA9 [8,9]. Therefore, CA9 is a specific biomarker of RCC and serves as a potential target for RCC-specific immunotherapy. CA9 contains major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I- and II-restricted epitopes recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and CD4+ T cells, respectively, and a CA9-specific immune response shows anti-tumour activity against RCC in vitro[10,11]. In addition, high expression of CA9 is associated with favourable prognostic factors in patients with metastatic clear cell RCC [12–14]. However, patients with advanced or metastatic RCC have a poor prognosis, suggesting that immune response against CA9 is not sufficient for generation of an anti-tumour response in vivo.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are primary antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that play a key role in regulation of immune responses to a variety of antigens [15,16], representing an attractive tool for therapeutic immunization of cancer [17]. Collective results of DC vaccines have demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of this approach against RCC [18–20]. However, vaccination of DCs pulsed with CA9-derived peptides did not induce a strong CA9-specific anti-tumour immune response in patients with RCC [18] and a potent immunostimulator for target-specific immunotherapy against RCC is needed. In order to enhance immunogenic potential of CA9-based immunotherapy for RCC, a combination of CA9 with potent cytokines, including interferon (IFN)-γ[21], tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α[21] and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [22,23], has been introduced. In addition, pathogen-associated molecular patterns, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), peptidoglycans, unmethylated cytosine-phosphorothionateguanine-rich oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG-ODN) and bacterial cell wall proteins, have a capacity for activation of non-specific immune responses [24]. Among them, CpG-ODN was shown to potentiate DC vaccines against murine renal cell carcinoma (RENCA) [25]. We have demonstrated previously that Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A (AbOmpA) induced DC maturation and drove T helper type 1 (Th1) polarization of immune responses in vitro[26]. DCs pulsed with AbOmpA combined with tumour cell lysates showed strong anti-tumour activity against murine melanoma [27], suggesting that AbOmpA may enhance the immunogenic potential of tumour-associated antigens (TAAs). In this study, in an attempt to induce a potent anti-tumour immune response against RCC we produced a recombinant CA9-AbOmpA fusion protein and evaluated DCs pulsed with a recombinant CA9-AbOmpA fusion protein as a RCC-specific tumour vaccine in a RENCA model.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Recombinant mouse GM-CSF and IL-4 were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies were used to detect expression of CD11c (HL3), CD40 (1C10), CD80 (16-10A1), CD86 (GL1), MHC class I (H-2Kb) and MHC class II (I-Ab) (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). An isotype-matched control monoclonal antibody, biotinylated anti-CD11c (N418) (BD Pharmingen), was used for flow cytometry.

Animals and cell lines

Male BALB/c mice, 6–8 weeks old, were purchased from Bio Korea (Gyunggi-do, Korea) and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. All experiments involving animals were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Kyungpook National University. A RENCA cell line, RCC syngeneic to the BALB/c mouse [28], was kindly provided by Dr S.-J. Hong (Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea). Parental RENCA cells and RENCA cells stably transducing the human CA9 gene (RENCA-CA9) were cultured and maintained in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 2 m l-glutamine, 1000 U/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Generation of RENCA-CA9 cells

A human CA9 cDNA was purchased from Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB, Daejeon, Korea). The full length of the CA9 gene was amplified using the primer pair 5′-TGT CTA GAC CAT GGC TCC CCT GTG CCC-3′ and 5′-CGC AAT TGG GCT CCA GTC TCG GCT AC-3′. A retrovirus encoding the human CA9 gene under a cytomegalovirus promoter-originated lentivirus human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) puro [H1·4] (Macrogen Inc., Seoul, Korea) was used for generation of the RENCA-CA9 tumour cell line. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product was cloned into the viral vector using XbaI and XhoI restriction enzymes, generating pLentiH1·4-CA9, with a size of 8·466 Kb. Recombinant lentivirus was produced as described previously [29,30]. Briefly, three plasmids, a transfer vector, an envelope glycoprotein expression vector and a packaging vector, were co-transfected into 293T cells at a 1:1:1 molar ratio using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen). The culture supernatant containing viral particles was harvested 48 h after transfection, and clarified using a 0·45 µm membrane filter (Nalgene, Rochester, NY, USA). The supernatant was used in transduction of RENCA cells. Both reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) using primers 5′-GAC TAC ACC GCC CTG TGC-3′ and 5′-CGC TCG AGC TAG GCT CCA GTC TCG GCT AC-3′ and Western blot using a monoclonal anti-mouse CA9 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were performed in order to verify successful transduction of the CA9 gene.

Gene cloning and purification of recombinant proteins

Recombinant AbOmpA and CA9 proteins were produced as described previously [26,27]. Briefly, the full length of AbOmpA and CA9 genes was amplified and cloned into the pET28a expression vector. Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3)/pET28a harbouring the AbOmpA and CA9 genes was grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C and both recombinant proteins were over-expressed by treatment with 1 mm of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) at 25°C for 4 h. Recombinant proteins were purified using a nickel-column (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and LPS was removed by polymyxin B-coated beads (Sigma). The N-terminal region of CA9 (1–120 amino acids) was amplified using the primers 5′-GGC CCA TAT GAT GGC TCC CCT GTG CCC CAG CCC C-3′ and 5′-GGC CGA ATT CTC CAG GAG CCT CAA CAG TAG GTA G-3′ and the N-terminal transmembrane region of AbOmpA (1–200 amino acids) was amplified using the primers 5′-GGC CGA ATT CAT GAA ATT GAG TCG TAT TGC ACT T-3′ and 5′-GGC CAA GCT TAG GCT TCA AGT GAC CAC CAA GAA C-3′. PCR products were digested with NdeI and EcoRI for CA9 (1–120) and EcoRI and HindIII for AbOmpA (1–200) and the resulting PCR products were ligated. Purified DNA was cloned into the NdeI/ HindIII-digested pMAL-C2X (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA, USA). E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pMAL-C2X harbouring the CA9-AbOmpA fusion gene was grown in LB medium at 37°C and recombinant CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins were over-expressed with 0·5 mm of IPTG at 30°C for 4 h. The fusion protein was purified by one-step affinity purification specific for maltose-binding proteins and factor Xa cleavage. After purification of recombinant proteins, LPS was removed by polymyxin B-coated beads (Sigma). Concentrations of LPS were determined using a Limulus amoebocyte lysate test kit (Sigma), respectively. The quantity of endotoxin in the recombinant proteins was ≤0·01 ng/mg.

Generation of bone marrow-derived DCs and antigen pulsing

DCs were generated from murine bone marrow-derived cells as described previously, with some modifications [26,31]. Bone marrow was flushed from the tibia and femur of BALB/c mice and ammonium chloride was used for depletion of erythrocytes. Cells were cultured in OptiMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 ng/ml recombinant mouse GM-CSF and 20 ng/ml IL-4 at 37°C in 5% CO2. To obtain a high purity of DC populations, DCs were labelled with a bead-conjugated anti-CD11c monoclonal antibody (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), followed by positive selection through paramagnetic columns (LS columns; Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For antigen pulsing, DCs (1 × 106 cells/ml) were treated with either LPS (200 ng/ml), CA9 (200 ng/ml), a combination of CA9 (200 ng/ml) and AbOmpA (200 ng/ml), CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins (400 ng/ml) or RENCA-CA9 cell lysates (10 µg/ml) at 37°C for 24 h.

Preparation of splenic lymphocytes

BALB/c mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation for preparation of splenic lymphocytes. Spleens were mechanically disrupted and passed through a sterile nylon mesh filter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The resulting cells were centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min and erythrocytes were removed. Cells were suspended and incubated in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7·4), 0·1 mm non-essential amino acids, 1 mm sodium pyruvate and 50 µm 2-mercaptoethanol. Splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated via a magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) column (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany). Staining with fluorescein PE-labelled anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (BD PharMingen) revealed that they consisted mainly of CD4+ T cells (>95%).

Flow cytometric analysis

Single-cell suspensions of DCs were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7·2) and blocked with 10% (v/v) normal goat serum (Invitrogen) for 15 min at 4°C. DCs were stained with appropriate fluorescence-conjugated antibodies for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were analysed using a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)Calibur flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA) with gating on CD11c+ cells.

Cytotoxicity assay

RENCA-CA9 cells (5 × 105) suspended in 100 µl of PBS were administered by subcutaneous injection into the right lower back of mice on day 0. DCs (1 × 106) pulsed with antigens or unstimulated immature DCs were administered subcutaneously on the opposite side of the back on days 3, 10 and 17. Splenocytes were isolated from three mice 3 days after the final immunization and were stimulated by co-culture with DCs pulsed with immunizing antigens for 4 days. These stimulated cells were used as effector cells. Cytotoxic responses of effector cells were assessed using a cell counting kit-8 (CCK8) test, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dojindo Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan). RENCA-CA9 cells (5 × 103 cells) were co-cultured with effector cells at various effector : target ratios. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h and the absorbance of the solution was determined at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer. Cytotoxicity was calculated according to the following formula: cellular cytotoxicity (%) = [1-A450 (sample)/A450 (control)] × 100.

Confocal laser microscopy

RENCA-CA9 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 on glass coverslips the day before the assay. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature for 10 min. Non-specific binding was blocked with 10% normal goat serum for 1 h. CA9 expressed on the cell surface was labelled with a monoclonal anti-mouse CA9 antibody, followed by Alexa-568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Nuclei of cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (Molecular Probes). Samples were analysed using a Carl-Zeiss fluorescence microscope.

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates or recombinant proteins were separated in 12% sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and then transferred onto nylon membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk and then incubated with anti-mouse CA9 antibody, anti-rabbit AbOmpA antibody and anti-β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The membrane was incubated with a secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase and developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL plus; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Culture supernatants from DCs or T cells were collected and stored at −70°C for ELISA of TNF-α, IL-2, IL-10, IL-12p40 and IFN-γ according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Pharmingen). Concentrations of cytokines were calculated using standard curves generated from recombinant cytokines.

Tumour growth

RENCA-CA9 cells (5 × 105) suspended in 100 µl of PBS were administered by subcutaneous injection into the right lower back of mice on day 0. DCs (1 × 106) pulsed with antigens or unstimulated DCs were administered by subcutaneous injection into the opposite side of the back on days 3, 10 and 17. Tumours were measured at intervals of 7 days and tumour volume (mm3) was calculated as follows: V = (A2 X B)/2, where A is the length of the short axis and B is the length of the long axis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using a Student's t-test. Data are presented as mean ± standard error and the values of P < 0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Production of CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins

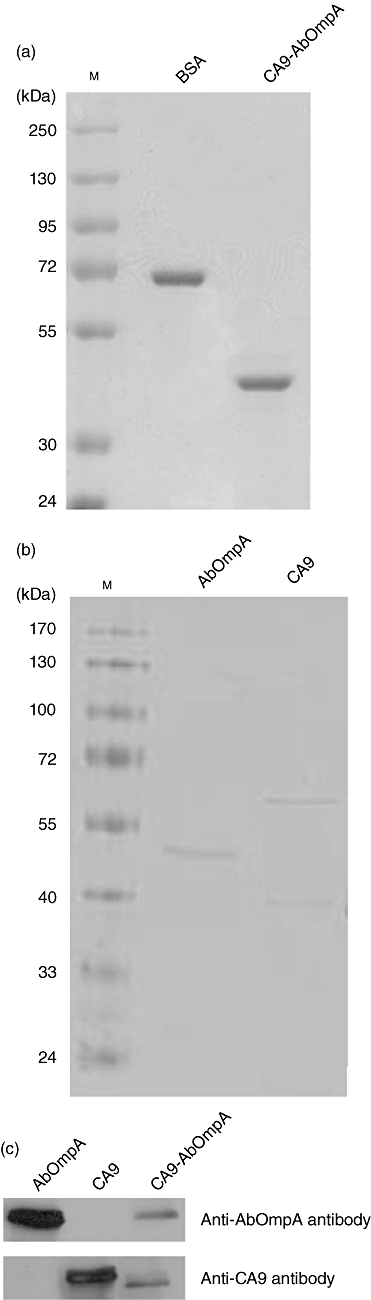

In order to produce a recombinant CA9-AbOmpA fusion protein, 360 base pairs (bp) of the CA9 gene encoding the N-terminal proteoglycan-like domain and 600 bp of the AbOmpA gene encoding the extracellular and transmembrane region were amplified using full-length CA9 cDNA and the AbOmpA gene as templates, respectively. PCR products were digested with NdeI and EcoRI for CA9 and EcoRI and HindIII for AbOmpA and the resulting PCR products were ligated to produce CA9 fused at the C-terminus with AbOmpA. Purified DNA was cloned in-frame for generation of pMAL-C2X-CA9-AbOmpA. Expression of recombinant fusion proteins in E. coli BL21 (DE3) transformed with pMAL-C2X-CA9-AbOmpA was induced by IPTG. After purification of recombinant proteins and removal of maltose-binding proteins, recombinant CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins with the expected molecular size of 37 kDa were generated (Fig. 1a). We also produced His-tagged recombinant AbOmpA and CA9 proteins (Fig. 1b). Recombinant CA9-AbOmpA proteins were verified by Western blot using anti-CA9 and anti-AbOmpA antibodies, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1c, CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins were reacted with anti-CA9 and anti-AbOmpA antibodies.

Fig. 1.

Production of recombinant proteins. (a) Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of purified carbonic anhydrase IX-Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A (CA9-AbOmpA) fusion proteins. CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins wherein AbOmpA (1–200) was fused to the C-terminus of CA9 (1–120) were generated. M: molecular marker; BSA: bovine serum albumin. (b) SDS-PAGE of recombinant His-tagged AbOmpA and CA9 proteins. M: molecular marker. (c) Immunoblots of CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins using anti-AbOmpA and anti-CA9 antibodies.

Maturation and cytokine production in DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins

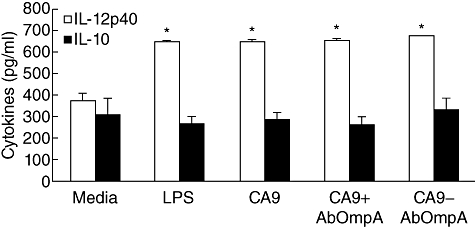

To determine maturation of DCs pulsed with recombinant proteins, immature DCs were treated with CA9 alone, a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA and CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins, and expression of cell surface molecules involved in T cell activation, including CD40, CD80, CD86 and MHC class I and class II, was analysed by flow cytometry. E. coli LPS was used as a positive control. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules in DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins was higher than that of DCs pulsed with CA9 alone (Table 1). Expression of CD80, CD86 and MHC class II in DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins was slightly higher than that of a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA-pulsed DCs. Next, using ELISA, we measured cytokine production in DCs pulsed with recombinant proteins. IL-12 is a potent driving factor for development of Th1 cells and enhances the cytolytic functions of CD8+ CTLs, whereas IL-10 has inhibitory effects on the accessory functions of DCs [17]. IL-12p40 showed a significant increase in antigen-pulsed DCs, compared with untreated control DCs; however, no significant difference in IL-12p40 production was observed between recombinant proteins tested (Fig. 2). Production of IL-10 was similar between antigen-pulsed DCs and untreated DCs. These results suggest that CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins enhance immunostimulatory ability of DCs.

Table 1.

Cell surface phenotype of DCs pulsed with recombinant proteins†

| Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI)‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigens | CD40 | CD80 | CD86 | MHC class I | MHC class II |

| Control§ | 853 | 6660 | 17 210 | 48 066 | 17 726 |

| Lipopolysaccharides | 2289 | 14 207 | 31 685 | 81 372 | 35 632 |

| CA9 | 2345 | 11 332 | 24 087 | 65 249 | 24 580 |

| Combination of CA9 and AbOmpA | 2515 | 12 603 | 27 180 | 69 037 | 29 494 |

| CA9-AbOmpA | 2245 | 13 495 | 29 603 | 68 844 | 32 395 |

Cells were stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry with isotype controls.

The result is representative of three independent experiments that showed similar results.

Control consisted of immature DCs cultured in media alone.

CA9-AbOmpA: carbonic anhydrase IX-Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A; MHC: major histocompatibility complex.

Fig. 2.

Cytokine production of dendritic cells (DCs) pulsed with recombinant proteins. DCs were pulsed with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and recombinant proteins for 24 h. The culture supernatant was collected and production of interleukin (IL)-12p40 and IL-10 was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Data are presented as mean ± standard error in three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 when compared with untreated control DCs (media).

T cell response interacting with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins

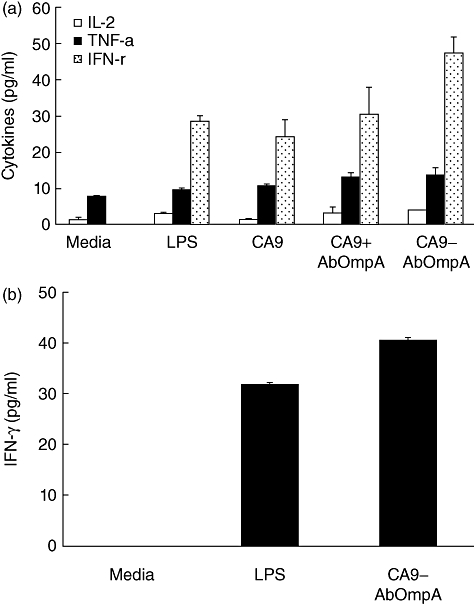

Interaction of APCs with naive T cells is essential to initiation of an adaptive immune response. In order to determine whether DCs pulsed with recombinant proteins could interact with T cells, DCs were pulsed with CA9 alone, a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA and CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins and co-cultured with syngeneic splenic T cells. Phase contrast microscopy showed cluster formation in T cells interacting with DCs pulsed with recombinant proteins tested. Cluster formation was the most prominent in DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins (data not shown). For determination of cytokine production in T cells interacting with DCs pulsed with recombinant proteins, splenic T cells were co-cultured with DCs pulsed with recombinant proteins at a 10:1 T cell : DC ratio for 72 h. IL-2 is an important growth and activation factor for T lymphocytes and a large amount of IFN-γ is produced by Th1 cells [16,17]. Secretion of IL-2, TNF-α and IFN-γ in T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with recombinant proteins tested showed a significant increase compared with that of T cells co-cultured with untreated DCs (Fig. 3a). Production of IL-2 and IFN-γ in T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins was significantly higher than that of T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with CA9 alone. To determine whether DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins could polarize Th1 cells, splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated and co-cultured with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins. Secretion of IFN-γ showed a significant increase in DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins, compared with untreated DCs (Fig. 3b). These results suggest that CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins are more potent immunostimulators of DCs in initiation of an adaptive immune response and polarization of Th1 immune response than CA9 alone.

Fig. 3.

Cytokine production of T cells co-cultured with dendritic cells (DCs) pulsed with recombinant proteins. (a) Splenic T cells were co-cultured with DCs pulsed with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and recombinant proteins for 72 h. Cytokines, interleukin (IL)-2, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon (IFN)-γ, in the culture supernatant were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (b) Splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated and co-cultured with DCs pulsed with LPS and carbonic anhydrase IX-Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A (CA9-AbOmpA) fusion proteins for 72 h. IFN-γ in the culture supernatant were measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± standard error in three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 when compared with DCs pulsed with CA9 alone (a) or untreated control DCs (b).

Generation of stable RENCA-CA9 cells

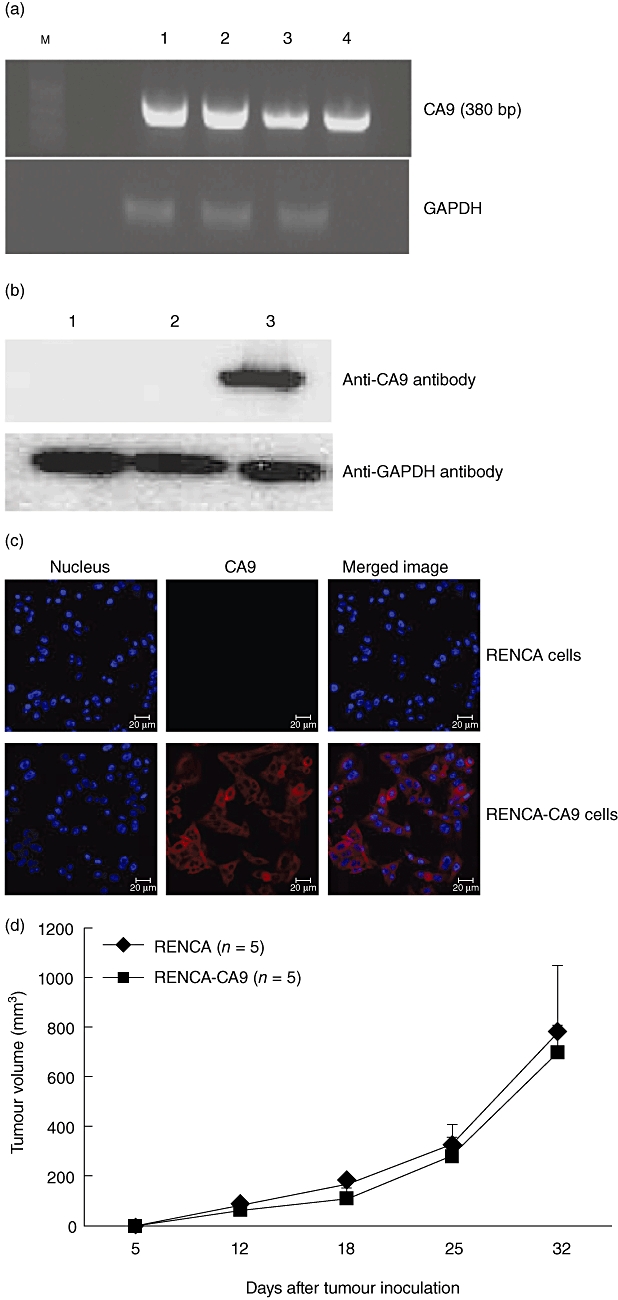

For determination of anti-tumour immune response of DC vaccines against RCC, we established stable CA9-expressing RENCA cells. The viral vector harbouring the full-length of the CA9 gene was transduced into wild-type RENCA cells. After one passage of cells, a single cell was selected and subcultured for 13 passages. Stable integration of the CA9 gene in RENCA cells was verified by RT–PCR (Fig. 4a) and production of CA9 proteins was verified by Western blot using an anti-mouse CA9 antibody (Fig. 4b). Confocal laser microscopy showed stable expression of CA9 proteins on the cell surface of RENCA-CA9 cells (Fig. 4c). For comparison of tumour growth between wild-type RENCA cells and RENCA-CA9 cells in vivo, tumour cells (5 × 105) were administered by subcutaneous injection into the lower back of BALB/c mice and tumour growth was measured. Tumour growth was similar between wild-type RENCA cells and RENCA-CA9 cells until 30 days (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Establishment of stable renal cell carcinoma (RENCA)-carbonic anhydrase IX (CA9) cell lines. (a) Wild-type RENCA cells were transduced with the CA9 gene and single cell was subcultured to 13 passages. Cells were harvested and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) was performed to determine expression of the CA9 gene. Lane M, size marker of a 100 base pairs (bp) ladder; lane 1, RENCA-CA9 cells in passage 5; lane 2, RENCA-CA9 cells in passage 10; lane 3, RENCA-CA9 cells in passage 13; lane 4, plasmid DNA of lentivirus human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) puro [H1·4] cloned with the CA9 gene. GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (b) Expression of CA9 proteins in RENCA-CA9 cells. Lane 1, wild-type RENCA cells; lane 2, RENCA cells transduced with the plasmid vector; lane 3, RENCA cells transduced with the CA9 gene. Cells were harvested and Western blot was performed using a monoclonal anti-mouse CA9 antibody. (c) RENCA-CA9 cells were cultured on glass coverslips for 24 h and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were not permeabilized with Triton X-100 for staining of CA9 proteins on the cell surface. CA9 was labelled with anti-mouse CA9 antibody, followed by Alexa-568-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibody. Nuclei of cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). CA9 proteins were expressed on the cell surface. (d) Growth kinetics of RENCA and RENCA-CA9 cells. A group of five mice were injected with tumour cells (5 × 105) on day 0. Tumours were measured at intervals of 6 or 7 days and tumour volume was calculated. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of five mice.

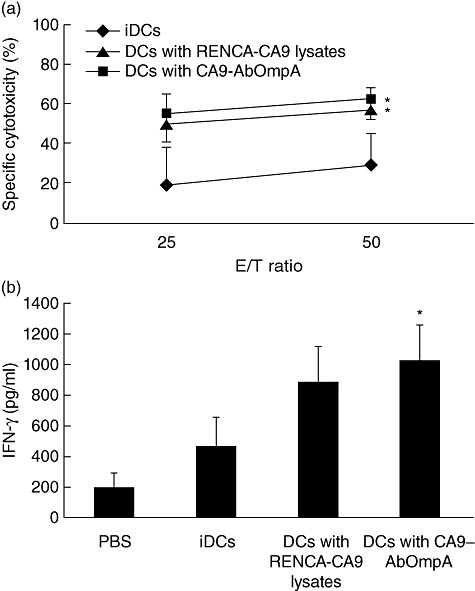

CTL response specific for RENCA-CA9 cells by DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins

To determine the ability of DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins for generation of CA9-specific CTLs, RENCA-CA9 cells were co-cultured with effector cells and cytotoxicity was determined. Splenocytes from mice immunized with PBS, immature DCs and DCs pulsed with RENCA-CA9 cell lysates and DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins were used as effector cells. We used RENCA-CA9 cell lysates to pulse DCs instead of CA9 proteins, because RENCA-CA9 cells over-expressed CA9 proteins on their surface (Fig. 4c) and could express a broad repertoire of TAAs. Splenocytes from mice immunized with DCs pulsed with RENCA-CA9 cell lysates and CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins showed more efficient induction of cytotoxicity of target cells than those obtained from mice immunized with immature DCs (Fig. 5a); however, there was no significant difference in cytotoxicity of effector cells between RENCA-CA9 cell lysates and CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins. Because CTL was known to secrete IFN-γ in an antigen-specific manner, we analysed IFN-γ secretion in culture supernatant of effector cells with RENCA-CA9 cells. As shown in Fig. 5b, IFN-γ production in effector cells from mice immunized with DC pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins was significantly higher than that of effector cells from mice immunized with immature DCs. These results suggest that immunization of mice with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins induces a potent CTL response specific for RENCA-CA9 tumours in vitro.

Fig. 5.

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response of lymphocytes stimulated with immature dendritic cells (DCs), DCs pulsed with renal cell carcinoma (RENCA)-CA9 cell lysates and DCs pulsed with carbonic anhydrase IX-Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A (CA9-AbOmpA) fusion proteins. (a) Cytotoxicity of RENCA-CA9 target cells by lymphocytes stimulated with DCs pulsed with immunizing antigens. Three days after the final vaccination, mice were killed and effector cells were generated, as described previously. CTLs were tested for their ability to induce cytotoxicity of RENCA-CA9 cells. Data are mean ± standard error in three independent experiments. *Statistically significant at P < 0·05 using a Student's t-test. (b) Production of interferon (IFN)-γ in CTLs. Effector cells were co-cultured with RENCA-CA9 cells and IFN-γ levels in the culture supernatant were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). *P < 0·05 when compared with immature DCs (iDCs).

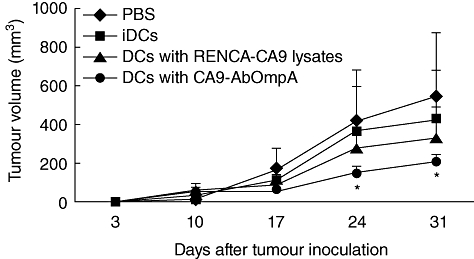

Suppression of tumour growth by DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins

To determine whether immunization of DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins could suppress tumour growth in mice with an established tumour burden, groups of 10 mice were inoculated with RENCA-CA9 cells and tumour-bearing mice were then treated three times with DC vaccines. Tumour growth showed significantly greater suppression in mice immunized with DC pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins than in mice immunized with PBS, immature DCs and DCs pulsed with RENCA-CA9 cell lysates (Fig. 6). These results suggest that DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins induce a potent therapeutic anti-tumour immune response against RENCA-CA9 cells in vivo.

Fig. 6.

Tumour growth of mice immunized with dendritic cell (DC) vaccines. A group of 10 mice were injected with renal cell carcinoma (RENCA)-CA9 cells (5 × 105) on day 0. Mice were immunized with a DC vaccine (1 × 106) with RENCA-CA9 cell lysates and carbonic anhydrase IX-Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A (CA9-AbOmpA) fusion proteins or immature DCs on days 3, 10 and 17. Tumours were measured at intervals of 7 days. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of 10 mice. *Statistically significant at P < 0·05 using a Student's t-test.

Discussion

Therapeutic DC vaccines are a promising approach to treatment of RCC and a number of studies have evaluated their anti-tumour efficacy in murine models and in human clinical trials [18–20,32,33]. CA9 has been identified as a potential target for immunotherapy specific for RCC. Monoclonal antibodies directed against CA9 in patients with advanced RCC have shown promising results in Phases I and II clinical trials [34,35]. However, no clinical responses were observed in RCC patients treated with DCs pulsed with two CA9-derived peptides, although DCs pulsed with CA9-derived peptides were able to induce a CTL response against CA9-expressing tumour cells in vitro[18]. Use of the fusion proteins, GM-CSF-CA9 and CA9-TNF, induced CA9-specific CTLs and enhanced the anti-tumour response against RCC in vivo[21,36]. These results suggest that immune response against CA9 alone is not sufficient for generation of a therapeutic anti-tumour response in vivo. In an attempt to enhance the anti-tumour activity of CA9 for potential use as a DC vaccine, we generated CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins using AbOmpA as an immunoadjuvant and analysed the anti-tumour immune response of DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins in vitro and in vivo.

We have demonstrated strongly induced DC maturation and Th1 polarization by AbOmpA, a major outer membrane protein of A. baumannii[26]. Follow-up experiments using AbOmpA found that DCs pulsed with AbOmpA alone or in combination with autologous tumour cell lysates suppressed tumour growth in mice with a murine B16 melanoma [27]. More recently, we examined the immunostimulatory activity of DCs pulsed with a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA in vitro in order to determine the potential of AbOmpA in DC-based immunotherapy against RCC [37]. Use of a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA proteins resulted in more efficient induction of DC maturation and T cell response than CA9 alone, suggesting a potential of AbOmpA for enhancement of anti-tumour immune response against RCC. However, full-length AbOmpA induced DC death in a dose-dependent manner [26]. The periplasmic C-terminal OmpA-like domain of AbOmpA carried a nuclear localization signal, which translocated AbOmpA to nuclei of host cells and induced cell death [38]. In addition, the N-terminal transmembrane region of AbOmpA (1–200 amino acids) was highly immunogenic by prediction of antigenic index [39], whereas the C-terminal OmpA-like domain (230–356 amino acids) showed a low immunogenicity. The N-terminal proteoglycan-like domain of CA9 was highly immunogenic and showed low cross-recognition with other isozymes [40]. Monoclonal antibody that recognized the N-terminal proteoglycan-like domain of CA9 proved to be highly specific for targeting of tumour cells in animal models [41]. Therefore, we carefully selected the N-terminal proteoglycan-like domain of CA9 (1–120 amino acids) and the N-terminal transmembrane region of AbOmpA (1–200 amino acids), and generated CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins having a proteoglycan-like domain of CA9 was fused at the C-terminus with a transmembrane region of AbOmpA. A recombinant CA9-AbOmpA fusion protein was generated in a prokaryotic system. Tumour antigens generated from prokaryotes have been used widely in DC-based vaccines and have induced tumour-specific CTL responses [42,43]. In the present study, CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins augmented DC maturation and cytokine secretion.

We examined the efficacy of CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins in inducing maturation and cytokine production in DCs, compared to that of CA9 alone. Our results showed that phenotypic expression of co-stimulatory molecules and secretion of IL-12 in DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins were increased slightly, compared with those of DCs pulsed with CA9 alone. However, IL-2 and IFN-γ production in T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins was significantly higher than that of T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with CA9 alone. In addition, IFN-γ production in CD4+ T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins was higher than that of CD4+ T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with LPS. These results suggest that CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins are a potent immunostimulator of DCs. A strong T cell response against CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins may be due to the highly immunogenic extracellular and transmembrane region of AbOmpA, which can potentiate immunostimulatory activity of DCs. We compared immunostimulatory activity of DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins to that of DCs pulsed with a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA. Immunostimulatory activity of DCs was similar between CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins and a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA, but IFN-γ production in splenic T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins was higher than that of T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA. However, in DC pulsing, CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins have an advantage over a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA. CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins were not cytotoxic in DCs up to protein concentrations of 10 µg/ml (data not shown), whereas 3 µg/ml of AbOmpA were cytotoxic in DCs [26]. Our results suggest more efficient enhancement of anti-tumour immunity against RCC by CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins, compared with CA9 alone or a combination of CA9 and AbOmpA.

We generated RENCA-CA9 cells to establish an optimal animal model that mimics the natural tumour biology observed in patients with CA9-expressing RCC. RENCA-CA9 cells were demonstrated to have reproducible growth kinetics and evenly expressed CA9 on the surface of tumour cells. Bui et al. [44] classified human RCC into two groups based on the expression of CA9 in the cells: RCC specimens in which >85% of cells stained for CA9 were labelled as high-expressing tumours, whereas those in which ≤85% of cells expressed CA9 were labelled as low-expressing tumours. They also showed intense membrane staining of CA9 in high CA9-expressing specimens. Therefore, our animal model might be reflecting high CA9-expressing RCC tumours, as all RENCA-CA9 cells expressed CA9 evenly on their surface. Using a RENCA-CA9 cell line stably transduced with the CA9 gene, we determined cytolytic activity and IFN-γ production of CTLs generated from splenic T cells immunized with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins. RENCA-CA9 cell lysates were used as a control because they could offer a broader repertoire of TAA as well as CA9. Cytotoxic activity and IFN-γ production of T cells from the mice immunized with DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins were higher than those of T cells immunized with immature DCs. Furthermore, DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins also demonstrated more efficient suppression of tumour growth, compared with DCs pulsed with RENCA-CA9 cell lysates. Findings from these in vivo studies suggest that DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins generate an anti-tumour immune response against RCC expressing CA9.

In conclusion, our results showed that that DCs pulsed with CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins induce a preferential Th1 immune response and CTL responses in vitro. In addition, our studies in mice with an established tumour burden suggest the potential use of CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins in development of DC vaccines against RCC. This finding implicates that CA9-AbOmpA fusion proteins can be applied to DC-based immunotherapy against RCC. Furthermore, this fusion protein is an attractive alternative to DC vaccines in CA9-expressing tumours, such as lung carcinoma, cervical carcinoma and oesophageal carcinoma [1,3].

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family affairs, Republic of Korea (0820190).

Disclosure

The authors declare no financial conflict of interests.

Authors' contribution

B.-R. Kim, E.-K. Yang and D.-Y. Kim contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Thiry A, Dogné JM, Masereel B, Supuran CT. Targeting tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase IX in cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:566–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wykoff CC, Beasley NJ, Watson PH, et al. Hypoxia-inducible expression of tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases. Cancer Res. 2000;60:7075–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanov S, Liao SY, Ivaova A, et al. Expression of hypoxia-inducible cell-surface transmembrane carbonic anhydrases in human cancer. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:905–19. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chia SK, Wykoff CC, Watson PH, et al. Prognostic significance of a novel hypoxia-regulated marker, carbonic anhydrase IX, in invasive breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3660–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Driessen A, Landuyt W, Pastorekova S, et al. Expression of carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX), a hypoxia-related protein, rather than vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a pro-angiogenic factor, correlates with an extremely poor prognosis in esophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas. Ann Surg. 2006;243:334–40. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000201452.09591.f3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HL, Seligson D, Liu X, et al. Using tumor markers to predict the survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2005;173:1496–501. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154351.37249.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loncaster JA, Harris AL, Davidson SE, et al. Carbonic anhydrase (CA IX) expression, a potential new intrinsic marker of hypoxia: correlations with tumor oxygen measurements and prognosis in locally advanced carcinoma of the cervix. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6394–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uemura H, Nakagawa Y, Yoshida K, et al. MN/CA IX/G250 as a potential target for immunotherapy of renal cell carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:741–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grabmaier K, Vissers JL, De Weijert MC, et al. Molecular cloning and immunogenicity of renal cell carcinoma-associated antigen G250. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:865–70. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000315)85:6<865::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vissers JL, De Vries IJ, Schreurs MW, et al. The renal cell carcinoma-associated antigen G250 encodes a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2.1-restricted epitope recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5554–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vissers JL, De Vries IJ, Engelen LP, et al. Renal cell carcinoma-associated antigen G250 encodes a naturally processed epitope presented by human leukocyte antigen-DR molecules to CD4+ T lymphocytes. Int J Cancer. 2002;100:441–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Martino M, Klatte T, Seligson DB, et al. CA9 gene: single nucleotide polymorphism predicts metastatic renal cell carcinoma prognosis. J Urol. 2009;182:728–34. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudek AZ, Yee RT, Manivel JC, Isaksson R, Yee HO. Carbonic anhydrase IX expression is associated with improved outcome of high-dose interleukin-2 therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:987–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shuch B, Li Z, Belldegrun AS. Carbonic anhydrase IX and renal cell carcinoma: prognosis, response to systemic therapy, and future vaccine strategies. BJU Int. 2008;101(Suppl 4):25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rescigno M, Martino M, Sutherland CL, Gold MR, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Dendritic cell survival and maturation are regulated by different signaling pathways. J Exp Med. 1998;11:2175–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449:419–26. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bleumer I, Tiemessen DM, Oosterwijk-Wakka JC, et al. Preliminary analysis of patients with progressive renal cell carcinoma vaccinated with CA9-peptide-pulsed mature dendritic cells. J Immunother. 2007;30:116–22. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211318.22902.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto A, Haraguchi K, Takahashi T, et al. Immunotherapy against metastatic renal cell carcinoma with mature dendritic cells. Int J Urol. 2007;14:277–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JH, Lee Y, Bae YS, et al. Phase I/II study of immunotherapy using autologous tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Immunol. 2007;125:257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer S, Oosterwijk-Wakka JC, Adrian N, et al. Targeted therapy of renal cell carcinoma: synergistic activity of cG250-TNF and IFNγ. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:115–23. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernández JM, Bui MH, Han KR, et al. Novel kidney cancer immunotherapy based on the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and carbonic anhydrase IX fusion gene. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1906–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue H, Iga M, Nabeta H, et al. Non-transmissible Sendai virus encoding granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor is a novel and potent vector system for producing autologous tumor vaccines. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2315–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsan MF, Baochong G. Pathogen-associated molecular pattern contamination as putative endogenous ligands of Toll-like receptors. J Endotoxin Res. 2007;13:6–14. doi: 10.1177/0968051907078604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chagnon F, Tanguay S, Ozdal OL, et al. Potentiation of a dendritic cell vaccine for murine renal cell carcinoma by CpG oligonucleotides. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1302–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JS, Lee JC, Lee CM, et al. Outer membrane protein A of Acinetobacter baumannii induces differentiation of CD4+ T cells toward a Th1 polarizing phenotype through the activation of dendritic cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JS, Kim JW, Choi CH, Lee WK, Chung HY, Lee JC. Anti-tumor activity of Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A on dendritic cell-based immunotherapy against murine melanoma. J Microbiol. 2008;46:221–7. doi: 10.1007/s12275-008-0052-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiltrout RH, Gregorio TA, Fenton RG, et al. Cellular and molecular studies in the treatment of murine renal cancer. Semin Oncol. 1995;22:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Follenzi A, Ailles LE, Bakovic S, Geuna M, Naldini L. Gene transfer by lentiviral vectors is limited by nuclear translocation and rescued by HIV-1 pol sequences. Nat Genet. 2000;25:217–22. doi: 10.1038/76095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, et al. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. 1998;72:8463–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winzler C, Rovere P, Rescigno M, et al. Maturation stages of mouse dendritic cells in growth factor-dependent long-term cultures. J Exp Med. 1997;185:317–28. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Höltl L, Zelle-Rieser C, Gander H, et al. Immunotherapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with tumor lysate-pulsed autologous dendritic cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Vries IJ, Bernsen MR, Lesterhuis WJ, et al. Immunomonitoring tumor-specific T cells in delayed-type hypersensitivity skin biopsies after dendritic cell vaccination correlates with clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5779–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis ID, Wiseman GA, Lee FT, et al. A phase I multiple dose, dose escalation study of cG250 monoclonal antibody in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bleumer I, Knuth A, Oosterwijk E, et al. A phase II trial of chimeric monoclonal antibody G250 for advanced renal cell carcinoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:985–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tso CL, Zisman A, Pantuck A, et al. Induction of G250-targeted and T-cell-mediated antitumor activity against renal cell carcinoma using a chimeric fusion protein consisting of G250 and granulocyte/monocyte-colony stimulating factor. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7925–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim BR, Yang EK, Kim SH, et al. Immunostimulatory activity of dendritic cells pulsed with carbonic anhydrase IX and Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A. J Microbiol. 2011;49:115–20. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-1037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi CH, Hyun SH, Lee JY, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A targets the nucleus and induces cytotoxicity. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:309–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jameson BA, Wolf H. The antigenic index: a novel algorithm for predicting antigenic determinants. CABIOS. 1988;4:181–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/4.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zat'ovicová M, Tarábková K, Svastová E, et al. Monoclonal antibodies generated in carbonic anhydrase IX-deficient mice recognize different domains of tumour-associated hypoxia-induced carbonic anhydrase IX. J Immunol Methods. 2003;282:117–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chrastina A, Závada J, Parkkila S, et al. Biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of 125I-labeled monoclonal antibody M75 specific for carbonic anhydrase IX, an intrinsic marker of hypoxia, in nude mice xenografted with human colorectal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2003;105:873–81. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho HI, Kim EK, Park SY, Lee SK, Hong YK, Kim TG. Enhanced induction of anti-tumor immunity in human and mouse by dendritic cells pulsed with recombinant TAT fused human surviving protein. Cancer Lett. 2007;258:189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Zan Y, Shan M, et al. Effects of heat shock protein gp96 on human dendritic cell maturation and CTL expansion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:581–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bui MH, Seligson D, Han KR, et al. Carbonic anhydrase IX is an independent predictor of survival in advanced renal clear cell carcinoma: implications for prognosis and therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:802–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]