Summary

The mitis group streptococci (MGS) are widespread in the oral cavity and are traditionally associated with oral health. However, these organisms have many attributes that contribute to the development of pathogenic oral communities. MGS adhere rapidly to saliva-coated tooth surfaces, thereby providing an attachment substratum for more overtly pathogenic organisms such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, and the two species assemble into heterotypic communities. Close physical association facilitates physiologic support, and pathogens such as Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans display resource partitioning to favour carbon sources generated by streptococcal metabolism. MGS exchange information with community members through a number of interspecies signaling systems including AI-2 and contact dependent mechanisms. Signal transduction systems induced in P. gingivalis are based on protein dephosphorylation mediated by the tyrosine phosphatase Ltp1, and converge on a LuxR-family transcriptional regulator, CdhR. Phenotypic responses in P. gingivalis include regulation of hemin uptake systems and gingipain activity, processes that are intimately linked to the virulence of the organism. Furthermore, communities of S. gordonii with P. gingivalis or with A. actinomycetemcomitans are more pathogenic in animal models than the constituent species alone. We propose that MGS should be considered accessory pathogens, organisms whose pathogenic potential only becomes evident in the context of a heterotypic microbial community.

Introduction

It is axiomatic that bacteria in the natural environment show a strong propensity to exist in biofilm communities. The ability of bacterial cells to communicate and co-ordinate their behavior provides the basis for community living, and confers advantages to the entire bacterial population. The mechanisms of biofilm initiation and development have been dissected in some molecular detail and reviewed extensively (Davey and O'Toole, 2000; Monds and O'Toole, 2009; Stanley and Lazazzera, 2004). However, such studies often focus on single species biofilms, whereas communities of bacteria on solid surfaces typically contain multiple, physiologically diverse bacterial taxa (Hansen et al., 2007a). Mixed microbial communities provide opportunities for competitive and co-operative interspecies interactions on a molecular and cellular level, and such interactions are predicted to shape the nature and function of the entire assemblage (Hansen et al., 2007b). Furthermore, an interconnected multispecies community comprises a multivariate web of trans-species signaling networks, imparting on constituents the ability to collectively regulate activities including gene expression, nutrient acquisition, and DNA exchange to list but a few. The physiology, and moreover, the potential pathogenicity, of a mixed species community is thus contingent on the flow of information throughout the polymicrobial consortia, which will invariably manifest properties greater than the sum of its component parts.

The oral biofilm that develops on tooth surfaces, colloquially known as dental plaque, is an exemplar of a mixed microbial community. Oral biofilms can contain over 700 bacterial phyla, although the number in an individual is closer to 200, and around 50 may be present at any one site (Aas et al., 2005). For the majority of individuals, most of the time, the presence of the oral biofilm is without pathogenic consequence. However, a populational shift toward, or more accurately the undue influence of, a group of gram-negative anaerobes can lead to periodontal disease (Jenkinson and Lamont, 2005). Similarly, over-representation of acidogenic organisms within the community increases the risk of dental caries (Takahashi and Nyvad, 2011). Early initiating organisms in the development of these assemblages are the mitis group streptococci (MGS), that includes S. gordonii, S. oralis, S. sanguinis and related species (Nobbs et al., 2009). These organisms have traditionally been considered commensals or even beneficial species, and certainly many aspects of their behaviour conform to this categorization. For example, MGS can foster the colonization and growth of other commensals, such as oral Actinomyces and Veillonella species (Jakubovics and Kolenbrander, 2010), and they can compete with and antagonize the cariogenic organism S. mutans (Kuramitsu et al., 2007). However, emerging evidence indicates that the MGS have a darker side and can play an active role in directing the development of a pathogenic oral biofilm community.

Coadhesion

The early events of streptococcal colonization offer little indication of future pathogenic consequences. The surfaces of MGS are decorated with a number of adhesins with specificity for the salivary proteins and glycoproteins that comprise the pellicle on tooth surfaces. Within minutes, teeth that are newly erupted into the oral cavity or professionally cleaned, become coated with a bacterial layer that can be up to 80% MGS (Nyvad and Kilian, 1987). This MGS-rich biofilm, known as early plaque, does not directly contribute to oral diseases. Nevertheless, the transition from a host tooth surface to what is essentially a bacterial surface allows the constituent streptococcal species to control and direct the subsequent colonization of other organisms (Slots and Gibbons, 1978; Kuboniwa and Lamont, 2010). The specificity of interspecies co-adhesive proteins is one mechanism by which streptococci can choreograph community development, and the selective recruitment of later colonizers has implications for caries, Candida infections and periodontal disease.

One of the best characterized interspecies coadhesion systems consists of the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis and MGS such as S. gordonii and S. oralis. Binding is effectuated by two sets of interacting adhesins involving streptococcal surface proteins and the major and minor fimbriae of P. gingivalis. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), while primarily a cytoplasmic enzyme, is also expressed on the surface of MGS where it binds the FimA-subunit fimbriae of P. gingivalis (Maeda et al., 2004). The minor Mfa-subunit fimbriae engage the SspA/B streptococcal surface proteins (Kuboniwa and Lamont, 2010) (Fig. 1). As the FimA fimbriae are longer than the Mfa fimbriae, attachment mediated by FimA is likely the initial contact event, and concordantly FimA deficient mutants do not localize streptococcal surfaces in open flow systems (Lamont et al., 2002). The binding domains of FimA that mediate attachment to streptococci are localized to a C-terminal region spanning amino acid (aa) residues 266–337 (Amano et al., 1997). GAPDH was first characterized as a component of the glycolytic pathway in which it is responsible for the phosphorylation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to generate 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate. However, GAPDH is also a major surface protein of streptococci and it exhibits multiple binding activities for a number of mammalian proteins (Pancholi and Fischetti, 1992). The FimA-interacting region of GAPDH spans aa residues 166 to 183, a domain with a predicted β-sheet structure. Substitution of the hydrophobic amino acids in this region with Ala abrogates activity, indicating that hydrophobic interactions are important for GAPDH-FimA binding (Nagata et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Structures required for the maintenance and stabilization of P. gingivalis-S. gordonii coadhesion. Center panel depicts the FimA-GAPDH and Mfa-Ssp adhesion-receptor pairs on the surfaces of P. gingivalis and S. gordonii. The left panel shows the interacting domains (lighter colour) of the FimA and GAPDH proteins with the amino acid (aa) residues indicated. The upper right panel shows the domain structure of the SspB protein and the aa residues involved in recognition of Mfa. LP: leader peptide; A: Ala-rich repeats; V: variable region; P: Pro-rich repeats; BAR: Mfa interacting domain; CWA: cell-wall anchor. BAR spans aa residues 1167-1193, and the EAAP, KKVQDLLKK, and NITVK sequences are involved in Mfa recognition. The lower right panel shows the structure of the SspB C-terminal region with the BAR handle region BAR handle stabilized by a calcium ion, and coordinated by three main chain and two side chain oxygen atoms and a water molecule. Crystal structure reproduced with permission from Forsgren et al. (2010).

Interaction of the Ssp and Mfa proteins is required for the subsequent accumulation of S. gordonii and P. gingivalis into heterotypic communities (Lamont et al., 2002). The Ssp proteins are members of the AgI/II family that is widely distributed in oral streptococci (Jenkinson and Demuth, 1997). AgI/II proteins are comprised of 6 structural domains: a leader peptide; alanine-rich repeats; a variable or divergent region; proline-rich repeats; a C-terminal region; and a cell-wall anchor (Jenkinson and Demuth, 1997). S. gordonii possesses two Ssp proteins, SspA and B, that are structurally and functionally conserved (Demuth et al., 1996). Molecular dissection of the Ssp-Mfa interaction identified an adherence-mediating region of SspB, designated BAR (SspB Adherence Region), that spans aa residues 1167–1193, and is fully conserved between SspA and SspB (Brooks et al., 1997). While the overall structure of the BAR region is important for binding activity, BAR contains three distinct domains that are required for Mfa interactions: aa residues 1182–1186 (NITVK); 1174–1178 (VQDLL); and 1168–1171 (EAAP). Within the NITVK domain the N1182 and V1185 residues are essential for Mfa recognition (Demuth et al., 2001); however, the activity of BAR does not strictly depend on the specific amino acid occupying the 1182 and 1185 positions, but rather on the physical properties and characteristics of the amino acid residues. Substitution of basic amino acids for N1182, and substitution of hydrophobic residues for V1185 enhances binding, suggesting that both electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions contribute to the BAR-Mfa interaction (Daep et al., 2006). The VQDLL motif of BAR constitutes an α-helix that resembles the eukaryotic nuclear receptor box domain which establishes protein-protein interactions through a hydrophobic or amphipathic α-helical motif (Daep et al., 2008). The VQDLL domain is flanked on either side by two lysine residues that are thought to stabilize the initial binding through a charge clamp mechanism. EXXP, which is a Ca2+ binding motif, is represented in BAR by EAAP (Daep et al., 2011), and crystallography data show that Pro1171 constrains the amphipathic VQDLL α-helix such that hydrophobic residues V1174, L1177 and L1178 face a hydrophobic contact surface (Forsgren et al., 2010). Hence, the function of EAAP may be to maintain the structural integrity of the VQDLL domain. Indeed, the crystal structure shows that the NITVK and VQDLL motifs protrude from the polypeptide in a configuration that resembles an attachment ‘handle’ for P. gingivalis, and this structure is stabilized by Ca2+ (Forsgren et al., 2010). An understanding of the structural characteristics of the Ssp-Mfa interface will facilitate the rational design of compounds that can block this interaction and impede the accumulation of P. gingivalis on streptococcal substrates.

In addition to binding to P. gingivalis, MGS can coadhere with the cariogenic mutans group streptococci (Lamont and Rosan, 1990), and with the opportunistic fungal pathogen C. albicans (Nobbs et al., 2010). The SspB protein also serves as an attachment site for the hyphal-wall specific protein Als3 of Candida, and this interaction stimulates the development of a mixed bacterial-fungal community with potential increased risk for candidiasis (Silverman et al., 2010). However, in the case of mutans streptococci, the beneficial coadhesive interaction provided by MGS may be superseded by numerous antagonistic interactions between these organisms based the production of hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins (Kuramitsu et al., 2007). Indeed, despite the interspecies binding interactions, these organisms are considered to be mutually exclusive and establishment of either MGS or mutans streptococci in a niche may preclude colonization by the antagonistic species (Kreth et al., 2005).

Interspecies coadhesion underlies, to a large extent, the temporal and spatial development of oral biofilm communities (Jakubovics and Kolenbrander, 2010; Rosan and Lamont, 2000; Kolenbrander et al., 2002). Thus, the composition and pathogenic potential of the community will reflect the availability and specificity of adhesins. For example, the mutans group streptococci do not support P. gingivalis community accretion (Kuboniwa and Lamont, 2010; Lamont et al., 1992), and examination of existing genome sequences reveals that these organisms lack a functional BAR domain in their Ag I/II family proteins. Within the NITVK region, mutans group species possess a substitution in one or both of the N1182 and V1185 residues. While several members of the group (S. sobrinus. S. downei, and S. criceti) do possess a related NR box, the consensus sequence of VXXML differs from the MGS consensus sequence, and in addition, S. mutans lacks a NR box consensus sequence in this region altogether (Daep et al., 2008). In vivo, P. gingivalis can be isolated in areas rich in MGS that possess functional coadhesins, but rarely in association with mutans streptococci (Slots and Gibbons, 1978; Aas et al., 2008).

Physiological Interactions

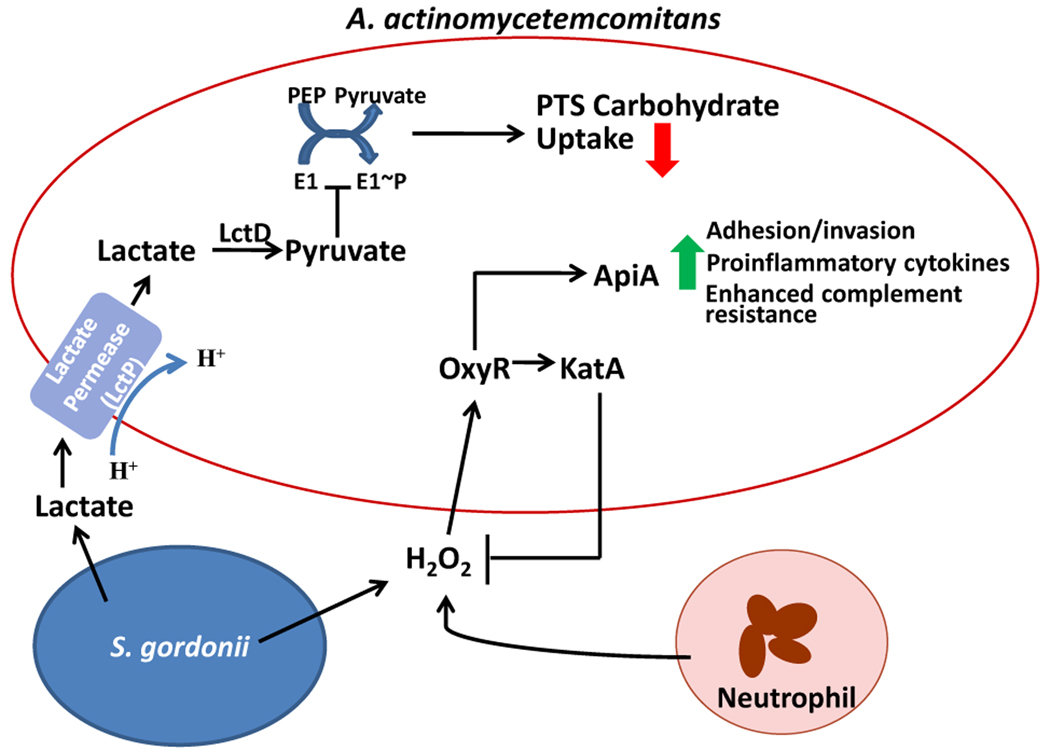

Organisms that assemble into communities tend to forge metabolically compatible groupings, and the community can compile a communal suite of enzymes for the progressive degradation of substrates that would be unavailable to individual species. This provides a framework for otherwise commensal species to enhance the pathogenicity of the community through physiological support of more destructive species. For example, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, the predominant pathogen in localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP), is slow growing and unlikely to compete effectively with other oral bacteria for carbon sources such as glucose (Brown and Whiteley, 2007). However, A. actinomycetemcomitans can also metabolize lactate, which is an end product of the fermentation of low molecular weight carbohydrates, such as glucose, by MGS. Moreover, in the presence of glucose A. actinomycetemcomitans will preferentially metabolize lactate, despite the slower growth rate of A. actinomycetemcomitans with lactate as a carbohydrate source as compared to glucose. In addition, A. actinomycetemcomitans will utilize lactate produced by S. gordonii in co-culture. Brown and Whiteley (2007) have proposed an exclusion model for this resource partitioning whereby lactate is first transported into A. actinomycetemcomitans by lactate permease (LctP) and converted to pyruvate by lactate dehydrogenase (LctD) (Fig. 2). Increased pyruvate levels inhibit autophosphorylation of the E1 transport protein which, in turn, reduces activity of the phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)-dependent phosphotransferase system (PTS). Glucose, fructose, mannose, and maltose are transported through the PTS system, whereas LctP is a proton-driven transporter. This lactate preference may afford some benefit to A. actinomycetemcomitans by allowing the organism to compete effectively with species that grow more rapidly in the presence of glucose. In areas that are rich in MGS, the presence of lactate may, therefore, favour the accumulation of A. actinomycetemcomitans, thereby increasing the potential for LAP to develop in a susceptible host.

Figure 2.

Schematic depiction of metabolite sensing by A. actinomycetemcomitans during growth with S. gordonii. Lactate produced by S. gordonii is transported into A. actinomycetemcomitans by the proton-driven lactate permease (LctP). Lactate dehydrogenase (LctD) converts lactate into pyruvate which inhibits autophosphorylation of E1, and thus decreases uptake of PTS carbohydrates such as glucose. Preferential utilization of lactate increases the competitive fitness of A. actinomycetemcomitans in the presence of organisms that can metabolize glucose more efficiently. S. gordonii derived hydrogen peroxide stimulates activation of the A. actinomycetemcomitans OxyR regulator, thereby increasing transcription of both apiA and katA. Elevated expression of ApiA leads to enhanced complement resistance and potentially higher levels of intracellular invasion and proinflammatory cytokine induction. Increased levels of KatA (catalase) will consume excess hydrogen peroxide, produced by both S. gordonii and neutrophils, thereby protecting A. actinomycetemcomitans from oxidative damage. Model compiled from Brown and Whiteley (2007), and Ramsey and Whiteley (2009).

S. gordonii can also provide metabolic support to P. gingivalis, and P. gingivalis exhibits mutalistic growth with S. gordonii in biofilm communities (Periasamy and Kolenbrander, 2009). Whole cell proteomic analyses have been performed on P. gingivalis in a community with S. gordonii and F. nucleatum, an organism that can reduce the oxygen concentration to levels preferred by P. gingivalis (Kuboniwa et al., 2009). Changes in abundance occurred in around 40% of the P. gingivalis proteome, implying extensive interactions among the organisms in the community. Differential regulation was consistent with increased protein synthesis and decreased stress, indicating a favourable environment for P. gingivalis. Interestingly, many of the proteins involved in thiamine diphosphate (vitamin B1) biosynthesis were downregulated, without a corresponding decrease in the proteins that utilize this cofactor, indicating that demand for vitamin B1 was unchanged (Kuboniwa et al., 2009). A likely explanation for the reduced cofactor pathways is nutrient transfer, such that organisms in the community provide P. gingivalis with vitamin B1 and thus contribute to the metabolic fitness of P. gingivalis.

Interspecies signaling

The interaction between MGS and the more overt pathogens extends beyond the somewhat passive activities of adhesive and physiologic support. While the full nature of the interspecies cross talk remains to be established, mutation of a large number of S. gordonii genes abolishes the ability of the organism to support a heterotypic community with P. gingivalis (Kuboniwa et al., 2006). The encoded proteins are involved in a wide range of activities including: cell wall integrity and maintenance of adhesive proteins (MsrA and MurE); extracellular capsule biosynthesis (PgsA, Atf); and physiology and gene regulation within S. gordonii (GdhA, NtpB, CcmA, and SpxB). In addition, one gene essential for S. gordonii-P. gingivalis community formation is cbe, which potentially participates in interspecies signaling. Chorismate binding enzyme (Cbe) is involved in the shikimate pathway, and chorismate is a branch point for biosynthetic pathways leading to the formation of aromatic metabolites including indole, anthranilate, and the aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan (He et al., 2004). Indole has been shown to function as an interspecies signal that controls E. coli-Pseudomonas fluorescens mixed communities (Lee et al., 2007), and anthranilate is a precursor of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) which is involved in biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Dong et al., 2008). The S. gordonii chromosome possesses homologues of the enzymes necessary for the production of indole and anthranilate from chorismate, thus Cbe has the potential to contribute to community development through the production of intercellular signaling molecules. Interestingly, several of the S. gordonii genes necessary for community formation, atf, gdhA, msrA, pgsA, spxB, ccmA, and cbe cluster in an ~40kb region on the S. gordonii chromosome. This cluster also contains bfrA/B, a two-component system, and bglB, a beta glucoside, both of which are involved in monospecies S. gordonii biofilm formation (Zhang et al., 2009; Kilic et al., 2004). Thus, the establishment of a mixed species community may be an integral developmental stage of the biofilm mode of existence of S. gordonii.

A common means of interspecies communication is through the LuxS/AI-2 system. MGS can produce AI-2 (Jakubovics and Kolenbrander, 2010), and AI-2 is necessary for S. gordonii-P. gingivalis community formation (McNab et al., 2003). Moreover, a LuxS deficient mutant of P. gingivalis remains capable of community formation with wild type S. gordonii, indicating that P. gingivalis will respond to the streptococcal derived AI-2 signal, and indeed, AI-2 from S. gordonii regulates gene expression in P. gingivalis (McNab et al., 2003; Chung et al., 2001). Although the molecular basis of AI-2 recognition and uptake in P. gingivalis is yet to be determined, LuxS/AI-2 signaling is integrated into the signal transduction that ensues from contact between P. gingivalis and S. gordonii (Maeda et al., 2008).

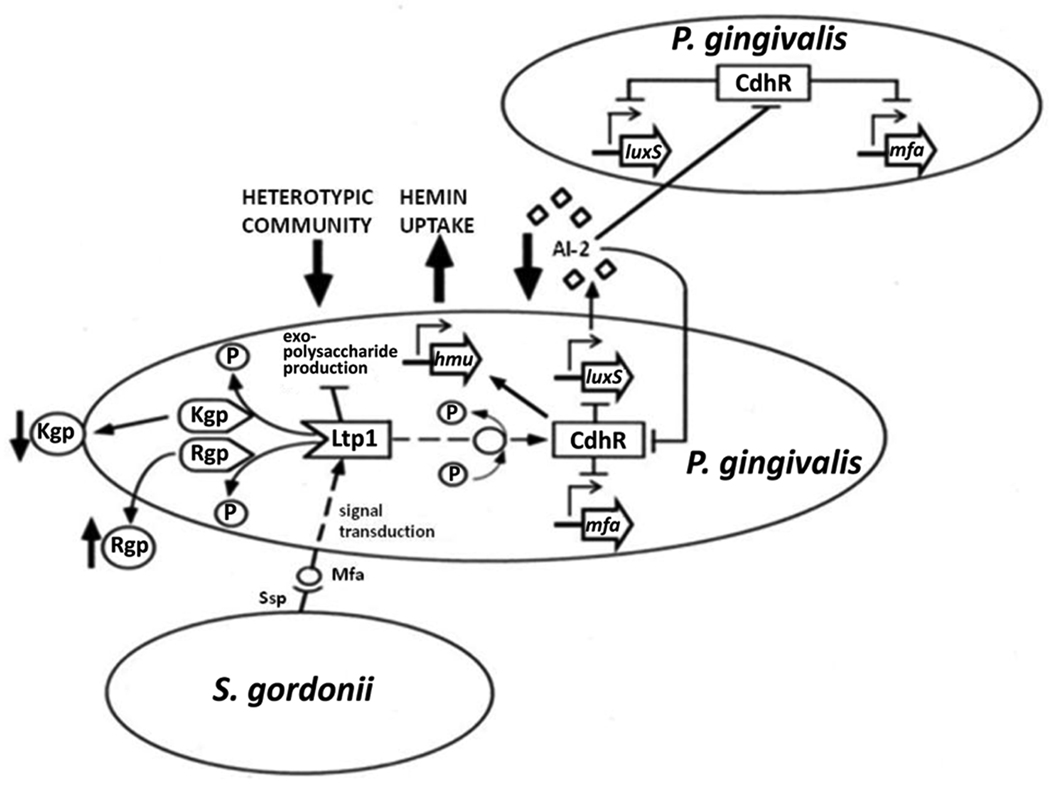

In addition to communication through the extracellular diffusible AI-2 molecule, contact between S. gordonii and P. gingivalis initiates a signaling cascade, which in turn can control AI-2 activity. In community-associated P. gingivalis, there is upregulation of ltp1, a gene encoding a cytoplasmic eukaryotic-type Low Molecular Weight Tyrosine Phosphatase (Simionato et al., 2006) (Fig. 3). Although expression of Ltp1 is increased in P. gingivalis–S. gordonii communities, deletion of the ltp1 gene, or loss of tyrosine phosphatase activity through expression of a catalytically inactive mutant, increases the level of P. gingivalis accumulation with S. gordonii (Maeda et al., 2008). Hence, the role of Ltp1 phosphatase activity is to constrain community development, a process that may serve to maintain an optimal area:volume ratio (Rainey and Rainey, 2003), or to prevent the community expanding into microenvironments that are more oxygenated and damaging to the obligately anaerobic P. gingivalis. Ltp1 signaling culminates in the downregulation of luxS transcription, which serves to limit community development through reduced AI-2 signaling. An additional mechanism by which Ltp1 functions to control community development is through downregulation of exopolysaccharide production. Ltp1 activity impacts transcription across several exopolysaccharide production loci, including those involved in K-antigen and anionic polysaccharide production (Paramonov et al., 2005). While exopolysaccharide physically protects bacterial cells (Xavier and Foster, 2007), it is energetically costly and some organisms terminate polymer secretion at high cell density (Nadell et al., 2008). Moreover, the polymer bulk can extrude individual cells from the confines of the community and into a more oxygenated environment (Xavier and Foster, 2007). Hence, P. gingivalis may fine tune exopolysaccharide production to maintain levels that allow retention, without propelling the organisms into the environment.

Figure 3.

Model of the interconnected networks of regulatory circuitry governing the heterotypic community development between P. gingivalis and S. gordonii. Convergence of the Ltp1 signaling system on CdhR results in the cumulative effect of constraining P. gingivalis-S. gordonii community formation. Interaction of Mfa fimbriae with S. gordonii initiates a signaling event that is transduced through Ltp1 and propagated throughout the community via a cascade of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation events. Ltp1 activity results in downregulation of exopolysaccharide production and dephosphorylation of the gingipain proteases Kgp and Rgp. Ltp1 activity indirectly upregulates CdhR expression, and CdhR represses transcription of luxS and mfa operons in P. gingivalis. Lower AI-2 levels sensed by additional P. gingivalis cells cause upregulation of CdhR and facilitate propagation of the original streptococcal-derived signal throughout the P. gingivalis-S. gordonii community.

The identities of proteins that are tyrosine phosphorylated/dephosphorylated in the Ltp1 signaling cascade are currently unknown; however, signaling converges on CdhR, an orphan LuxR family transcriptional regulator (Chawla et al., 2010). CdhR can bind to the upstream regulatory regions of both mfa and luxS, causing transcriptional repression and thereby restricting S. gordonii-P. gingivalis community development (Fig. 3). The Mfa-SspB binding event is necessary for initiation of the Ltp1–CdhR pathway as neither ltp1 nor cdhR are induced in a Mfa deficient mutant of P. gingivalis (Chawla et al., 2010) CdhR levels are also controlled by a feedback loop involving LuxS/AI-2 as exogenous synthetic AI-2 reduces expression of CdhR. Lower levels of AI-2 resulting from CdhR activity will allow the signal originally induced by S. gordonii to propagate through the developing heterotypic community, and regulate CdhR in P. gingivalis cells that are not in contact with S. gordonii (Chawla et al., 2010).

Numerous signaling systems are thus involved in communication between streptococci and P. gingivalis, and the full extent of these is likely yet to be appreciated. In some cases the importance of interspecies signaling has been demonstrated in vivo. Extracellular arginine deiminase of S. cristatus or S. intermedius functions as a signal that causes the downregulation of the FimA fimbrial adhesin in P. gingivalis, and consequently P. gingivalis does not accumulate into communities with these organisms (Xie et al., 2007; Christopher et al., 2010). Consistent with this, examination of subgingival plaque samples shows a negative correlation between the presence of S. cristatus and P. gingivalis (Wang et al., 2009). Hence antagonistic interspecies signaling in vitro is reflected in the failure of the organisms to associate in vivo.

Community virulence

While fostering the accumulation of pathogenic organisms is one contribution MGS make to oral diseases; for the streptococci to have bona fide pathogenic credentials the communities thus formed should be more virulent than the constituents individually. Evidence for synergistic pathogenicity is emerging. For example, co-culture with S. gordonii elevates the pathogenic potential of A. actinomycetemcomitans (Fig. 2). A. actinomycetemcomitans cells sense hydrogen peroxide, a metabolic byproduct of S. gordonii, and initiate a signal transduction pathway involving the stress response regulator OxyR, which upregulates expression of the katA and apiA genes (Ramsey and Whiteley, 2009). KatA is a cytoplasmic catalase that directly detoxifies H2O2 into O2 and H2O, and may also serve to enhance resistance to neutrophil-derived H2O2. ApiA is a trimeric outer membrane protein that is involved in adhesion and invasion of epithelial cells, and in the induction of proinflammatory cytokines (Asakawa et al., 2003). ApiA also binds the human serum protein factor H (Asakawa et al., 2003) which inhibits the alternative complement pathway and protects A. actinomycetemcomitans from complement mediated killing. Realization of the increased pathogenic potential of A. actinomycetemcomitans-S. gordonii communities has been achieved in vivo (Ramsey et al., 2011). Co-culture of A. actinomycetemcomitans with S. gordonii enhances the pathogenicity of A. actinomycetemcomitans in a mouse abscess model. L-lactate catabolism was necessary for the co-culture synergism, indicating that metabolic cross-feeding between S. gordonii and A. actinomycetemcomitans (discussed above) is an essential component of the community-associated virulence.

Both theoretical and experimental frameworks exist for enhanced pathogenicity of P. gingivalis in the context of a community with S. gordonii. An in silico multivariate machine learning study of sequenced genomes assessed the metabolic complement of each genome by scoring the completeness of all reference metabolic pathways, and the resulting automatically derived metabolic reconstructions were compared among 266 organisms (Kastenmuller et al., 2009). Periodontal pathogens, including P. gingivalis, Treponema denticola, Prevotella intermedia and F. nucleatum, showed an over-representation of pathways related to the metabolism of histidine, inferring that histidine degradation may be important in the virulence of these organisms. There are three predicted pathways in P. gingivalis through which histidine metabolism may occur: histidine2 (degradation of histidine to L-glutamate), fnc1 (glutamate fermentation), and c2 (degradation of 5-formimino-tetrahydrofolate [5-formimino-THF]). In the presence of S. gordonii, P. gingivalis upregulates two enzymes in the 5-formimino-THF pathway, FolD (methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase) and Fhs (formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase) (Simionato et al., 2006). A heterotypic community environment may therefore facilitate degradation of histidine, and push P. gingivalis toward a more virulent phenotype (Kuboniwa and Lamont, 2010).

Another community regulated pathway, the LuxS-CdhR system, has the potential to impact P. gingivalis virulence through reprogramming of hemin uptake systems. P. gingivalis has an obligate requirement for iron in the form of hemin for growth, and possesses several hemin acquisition and storage systems with different activities and affinities (Lewis, 2010). CdhR has been found to upregulate transcription of the hmu hemin binding and transport locus (Wu et al., 2009). LuxS/AI-2 negatively regulates the hemin binding lipoprotein FetB, the inner membrane ion transport protein FeoB1, and the iron storage protein ferritin (James et al., 2006). In contrast, Tlr, a TonB linked outer membrane receptor, is upregulated by LuxS (James et al., 2006). Also upregulated is the cysteine protease Kgp that can degrade host iron- and heme-containing proteins, and is thought to act as a hemophore, shuttling heme back to outer membrane receptors (Olczak et al., 2005). Furthermore, both Kgp and the Rgp A and B gingipains are substrates for dephosphorylation by Ltp1 which affects both their location and activity (Maeda et al., 2008). As hemin levels are known to modulate the biological properties of P. gingivalis LPS (Reife et al., 2006) and virulence in animal models (McKee et al., 1986; Marsh et al., 1994), the community phenotype of P. gingivalis can be predicted to be differentially pathogenic. The proof of the pathogenicity pudding is in the eating, in this case oral infection of mice with S. gordonii, P. gingivalis, or S. gordonii followed by P. gingivalis (Daep et al., 2011). Animals infected with S. gordonii followed by P. gingivalis displayed significantly greater bone loss compared to mice infected with either organism alone. Moreover, the inclusion of the BAR peptide with P. gingivalis infection reduced bone loss to the levels in sham-infected animals. The S. gordonii-P. gingivalis community that depends on Ssp-Mfa based coadhesion for development, therefore, displays enhanced virulence compared to species individually.

Conclusions

MGS have long been considered innocent bystanders in oral disease. However, the true pathogenic personality of these organisms may not be observable in single species culture. Examination of heterotypic communities containing MGS and more conventional pathogens such as P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans, suggests that MGS can make a significant contribution to the pathogenic process. While in many cases the bacterial inhabitants of humans have coevolved with their host to suppress pathogenic outcomes, bacteria in communities have also coevolved with each other, and this can lead to enhanced metabolic vigor, upregulation of virulence factors and more damage to the host. Thus, we propose that organisms such as the MGS be considered accessory pathogens, bacteria that are commensal in monoculture but elevate the pathogenicity of the community in which they reside. The elucidation of communication and physiology at a community level may provide the impetus for novel therapeutic modalities that target community development. However, oral hygiene involving the physical removal of the early streptococcal rich biofilm as practiced at least as early as in ancient Egyptian civilization, has attained a solid scientific foundation.

Acknowledgements

Laboratory research supported by DE12505 from NIH/NIDCR. We thank Don Demuth, Masae Kuboniwa, Howard Jenkinson and Paul Kolenbrander for helpful discussions, and Thomas J. Whitmore for assistance with the figures.

References

- Aas JA, Griffen AL, Dardis SR, Lee AM, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE, et al. Bacteria of dental caries in primary and permanent teeth in children and young adults. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1407–1417. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01410-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5721–5732. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano A, Fujiwara T, Nagata H, Kuboniwa M, Sharma A, Sojar HT, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae mediate coaggregation with Streptococcus oralis through specific domains. J Dent Res. 1997;76:852–857. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760040601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa R, Komatsuzawa H, Kawai T, Yamada S, Goncalves RB, Izumi S, et al. Outer membrane protein 100, a versatile virulence factor of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1125–1139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks W, Demuth DR, Gil S, Lamont RJ. Identification of a Streptococcus gordonii SspB domain that mediates adhesion to Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3753–3758. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3753-3758.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Whiteley M. A novel exclusion mechanism for carbon resource partitioning in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6407–6414. doi: 10.1128/JB.00554-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla A, Hirano T, Bainbridge BW, Demuth DR, Xie H, Lamont RJ. Community signalling between Streptococcus gordonii and Porphyromonas gingivalis is controlled by the transcriptional regulator CdhR. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78:1510–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher AB, Arndt A, Cugini C, Davey ME. A streptococcal effector protein that inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilm development. Microbiology. 2010;156:3469–3477. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.042671-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WO, Park Y, Lamont RJ, McNab R, Barbieri B, Demuth DR. Signaling system in Porphyromonas gingivalis based on a LuxS protein. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3903–3909. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.3903-3909.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daep CA, James DM, Lamont RJ, Demuth DR. Structural characterization of peptide-mediated inhibition of Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5756–5762. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00813-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daep CA, Lamont RJ, Demuth DR. Interaction of Porphyromonas gingivalis with oral streptococci requires a motif that resembles the eukaryotic nuclear receptor box protein-protein interaction domain. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3273–3280. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00366-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daep CA, Novak EA, Lamont RJ, Demuth DR. Structural dissection and in vivo effectiveness of a peptide inhibitor of Porphyromonas gingivalis adherence to Streptococcus gordonii. Infect Immun. 2011;79:67–74. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00361-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey ME, O'Toole GA. Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:847–867. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.4.847-867.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth DR, Duan Y, Brooks W, Holmes AR, McNab R, Jenkinson HF. Tandem genes encode cell-surface polypeptides SspA and SspB which mediate adhesion of the oral bacterium Streptococcus gordonii to human and bacterial receptors. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:403–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth DR, Irvine DC, Costerton JW, Cook GS, Lamont RJ. Discrete protein determinant directs the species-specific adherence of Porphyromonas gingivalis to oral streptococci. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5736–5741. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5736-5741.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong YH, Zhang XF, An SW, Xu JL, Zhang LH. A novel two-component system BqsS-BqsR modulates quorum sensing-dependent biofilm decay in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Commun Integr Biol. 2008;1:88–96. doi: 10.4161/cib.1.1.6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsgren N, Lamont RJ, Persson K. Two intramolecular isopeptide bonds are identified in the crystal structure of the Streptococcus gordonii SspB C-terminal domain. J Mol Biol. 2010;397:740–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SK, Haagensen JA, Gjermansen M, Jorgensen TM, Tolker-Nielsen T, Molin S. Characterization of a Pseudomonas putida rough variant evolved in a mixed-species biofilm with Acinetobacter sp. strain C6. J Bacteriol. 2007a;189:4932–4943. doi: 10.1128/JB.00041-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SK, Rainey PB, Haagensen JA, Molin S. Evolution of species interactions in a biofilm community. Nature. 2007b;445:533–536. doi: 10.1038/nature05514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Stigers Lavoie KD, Bartlett PA, Toney MD. Conservation of mechanism in three chorismate-utilizing enzymes. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2378–2385. doi: 10.1021/ja0389927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubovics NS, Kolenbrander PE. The road to ruin: the formation of disease-associated oral biofilms. Oral Dis. 2010;16:729–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James CE, Hasegawa Y, Park Y, Yeung V, Tribble GD, Kuboniwa M, et al. LuxS involvement in the regulation of genes coding for hemin and iron acquisition systems in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3834–3844. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01768-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson HF, Demuth DR. Structure, function and immunogenicity of streptococcal antigen I/II polypeptides. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:183–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2021577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson HF, Lamont RJ. Oral microbial communities in sickness and in health. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:589–595. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastenmuller G, Schenk ME, Gasteiger J, Mewes HW. Uncovering metabolic pathways relevant to phenotypic traits of microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R28. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic AO, Tao L, Zhang Y, Lei Y, Khammanivong A, Herzberg MC. Involvement of Streptococcus gordonii beta-glucoside metabolism systems in adhesion, biofilm formation, and in vivo gene expression. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4246–4253. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4246-4253.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolenbrander PE, Andersen RN, Blehert DS, Egland PG, Foster JS, Palmer RJ., Jr Communication among oral bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:486–505. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.486-505.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreth J, Merritt J, Shi W, Qi F. Competition and coexistence between Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis in the dental biofilm. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7193–7203. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7193-7203.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboniwa M, Hendrickson EL, Xia Q, Wang T, Xie H, Hackett M, Lamont RJ. Proteomics of Porphyromonas gingivalis within a model oral microbial community. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboniwa M, Lamont RJ. Subgingival biofilm formation. Periodontol 2000. 2010;52:38–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00311.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboniwa M, Tribble GD, James CE, Kilic AO, Tao L, Herzberg MC, et al. Streptococcus gordonii utilizes several distinct gene functions to recruit Porphyromonas gingivalis into a mixed community. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:121–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramitsu HK, He X, Lux R, Anderson MH, Shi W. Interspecies interactions within oral microbial communities. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:653–670. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, El-Sabaeny A, Park Y, Cook GS, Costerton JW, Demuth DR. Role of the Streptococcus gordonii SspB protein in the development of Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilms on streptococcal substrates. Microbiology. 2002;148:1627–1636. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, Hersey SG, Rosan B. Characterization of the adherence of Porphyromonas gingivalis to oral streptococci. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1992;7:193–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, Rosan B. Adherence of mutans streptococci to other oral bacteria. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1738–1743. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1738-1743.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Jayaraman A, Wood TK. Indole is an inter-species biofilm signal mediated by SdiA. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JP. Metal uptake in host-pathogen interactions: role of iron in Porphyromonas gingivalis interactions with host organisms. Periodontol 2000. 2010;52:94–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Nagata H, Yamamoto Y, Tanaka M, Tanaka J, Minamino N, Shizukuishi S. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Streptococcus oralis functions as a coadhesin for Porphyromonas gingivalis major fimbriae. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1341–1348. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1341-1348.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Tribble GD, Tucker CM, Anaya C, Shizukuishi S, Lewis JP, et al. A Porphyromonas gingivalis tyrosine phosphatase is a multifunctional regulator of virulence attributes. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:1153–1164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh PD, McDermid AS, McKee AS, Baskerville A. The effect of growth rate and haemin on the virulence and proteolytic activity of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. Microbiology. 1994;140:861–865. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-4-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AS, McDermid AS, Baskerville A, Dowsett AB, Ellwood DC, Marsh PD. Effect of hemin on the physiology and virulence of Bacteroides gingivalis W50. Infect Immun. 1986;52:349–355. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.349-355.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNab R, Ford SK, El-Sabaeny A, Barbieri B, Cook GS, Lamont RJ. LuxS-based signaling in Streptococcus gordonii: autoinducer 2 controls carbohydrate metabolism and biofilm formation with Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:274–284. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.274-284.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monds RD, O'Toole GA. The developmental model of microbial biofilms: ten years of a paradigm up for review. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:73–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadell CD, Xavier JB, Levin SA, Foster KR. The evolution of quorum sensing in bacterial biofilms. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata H, Iwasaki M, Maeda K, Kuboniwa M, Hashino E, Toe M, et al. Identification of the binding domain of Streptococcus oralis glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase for Porphyromonas gingivalis major fimbriae. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5130–5138. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00439-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobbs AH, Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. Streptococcus adherence and colonization. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:407–450. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00014-09. Table of Contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobbs AH, Vickerman MM, Jenkinson HF. Heterologous expression of Candida albicans cell wall-associated adhesins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals differential specificities in adherence and biofilm formation and in binding oral Streptococcus gordonii. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:1622–1634. doi: 10.1128/EC.00103-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyvad B, Kilian M. Microbiology of the early colonization of human enamel and root surfaces in vivo. Scand J Dent Res. 1987;95:369–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1987.tb01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olczak T, Simpson W, Liu X, Genco CA. Iron and heme utilization in Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:119–144. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancholi V, Fischetti VA. A major surface protein on group A streptococci is a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase with multiple binding activity. J Exp Med. 1992;176:415–426. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramonov N, Rangarajan M, Hashim A, Gallagher A, Aduse-Opoku J, Slaney JM, et al. Structural analysis of a novel anionic polysaccharide from Porphyromonas gingivalis strain W50 related to Arg-gingipain glycans. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:847–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy S, Kolenbrander PE. Mutualistic biofilm communities develop with Porphyromonas gingivalis and initial, early, and late colonizers of enamel. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6804–6811. doi: 10.1128/JB.01006-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey PB, Rainey K. Evolution of cooperation and conflict in experimental bacterial populations. Nature. 2003;425:72–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey MM, Rumbaugh KP, Whiteley M. Metabolite cross-feeding enhances virulence in a model polymicrobial infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002012. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey MM, Whiteley M. Polymicrobial interactions stimulate resistance to host innate immunity through metabolite perception. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1578–1583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809533106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reife RA, Coats SR, Al-Qutub M, Dixon DM, Braham PA, Billharz RJ, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide lipid A heterogeneity: differential activities of tetra- and penta-acylated lipid A structures on E-selectin expression and TLR4 recognition. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:857–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosan B, Lamont RJ. Dental plaque formation. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1599–1607. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman RJ, Nobbs AH, Vickerman MM, Barbour ME, Jenkinson HF. Interaction of Candida albicans cell wall Als3 protein with Streptococcus gordonii SspB adhesin promotes development of mixed-species communities. Infect Immun. 2010;78:4644–4652. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00685-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionato MR, Tucker CM, Kuboniwa M, Lamont G, Demuth DR, Tribble GD, Lamont RJ. Porphyromonas gingivalis genes involved in community development with Streptococcus gordonii. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6419–6428. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00639-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slots J, Gibbons RJ. Attachment of Bacteroides melaninogenicus subsp. asaccharolyticus to oral surfaces and its possible role in colonization of the mouth and of periodontal pockets. Infect Immun. 1978;19:254–264. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.1.254-264.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley NR, Lazazzera BA. Environmental signals and regulatory pathways that influence biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:917–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Nyvad B. The role of bacteria in the caries process: ecological perspectives. J Dent Res. 2011;90:294–303. doi: 10.1177/0022034510379602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang BY, Wu J, Lamont RJ, Lin X, Xie H. Negative correlation of distributions of Streptococcus cristatus and Porphyromonas gingivalis in subgingival plaque. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3902–3906. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00072-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Lin X, Xie H. Regulation of hemin binding proteins by a novel transcriptional activator in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:115–122. doi: 10.1128/JB.00841-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier JB, Foster KR. Cooperation and conflict in microbial biofilms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:876–881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607651104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Lin X, Wang BY, Wu J, Lamont RJ. Identification of a signalling molecule involved in bacterial intergeneric communication. Microbiology. 2007;153:3228–3234. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009050-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Whiteley M, Kreth J, Lei Y, Khammanivong A, Evavold JN, et al. The two-component system BfrAB regulates expression of ABC transporters in Streptococcus gordonii and Streptococcus sanguinis. Microbiology. 2009;155:165–173. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.023168-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]