Abstract

Mental health stigma operates in society, is internalized by individuals, and is attributed by health professionals. This ethics-laden issue acts as a barrier to individuals who may seek or engage in treatment services. The dimensions, theory, and epistemology of mental health stigma have several implications for the social work profession.

Key Terms: Mental Health, Psychiatric Conditions, Stigma, Treatment Engagement, Social Work Ethics

1. Introduction

In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that an estimated 25 percent of the worldwide population is affected by a mental or behavioral disorder at some time during their lives. This mental and behavioral health issue is believed to contribute to 12 percent of the worldwide burden of disease and is projected to increase to 15 percent by the year 2020 (Hugo, Boshoff, Traut, Zungu-Dirwayi, & Stein, 2003). Within the United States, mental and behavioral health conditions affect approximately 57 million adults (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2006). Despite the high prevalence of these conditions, recognized treatments have shown effectiveness in mitigating the problem and improving individual functioning in society. Nonetheless, research suggests that (1) individuals who are in need of care often do not seek services, and (2) those that begin receiving care frequently do not complete the recommended treatment plan (Corrigan, 2004). For example, it has been estimated that less than 40 percent of individuals with severe mental illnesses receive consistent mental health treatment throughout the year (Kessler, Berglund, Bruce, Koch, Laska, Leaf, et al, 2001).

There are several potential reasons for why, given a high prevalence of mental health and drug use conditions, there is much less participation in treatment. Plausible explanations may include (1) that those with mental health or drug use conditions are disabled enough by their condition that they are not able to seek treatment, or (2) that they are not able to identify their own condition and therefore do not seek needed services. Despite these viable options, there is another particular explanation that is evident throughout the literature. The U.S. Surgeon General (1999) and the WHO (2001) cite stigma as a key barrier to successful treatment engagement, including seeking and sustaining participation in services. The problem of stigma is widespread, but it often manifests in several different forms. There are also varying ways in which it develops in society, which all have implications for social work – both macro and micro-focused practice.

In order to understand how stigma interferes in the lives of individuals with mental health and drug use conditions, it is essential to examine current definitions, theory, and research in this area. The definitions and dimensions of stigma are a basis for understanding the theory and epistemology of the three main ‘levels’ of stigma (social stigma, self-stigma, and health professional stigma).

2. Stigma Definitions & Dimensions

The most established definition regarding stigma is written by Erving Goffman (1963) in his seminal work: Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Goffman (1963) states that stigma is “an attribute that is deeply discrediting” that reduces someone “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (p. 3). The stigmatized, thus, are perceived as having a “spoiled identity” (Goffman, 1963, p. 3). In the social work literature, Dudley (2000), working from Goffman’s initial conceptualization, defined stigma as stereotypes or negative views attributed to a person or groups of people when their characteristics or behaviors are viewed as different from or inferior to societal norms. Due to its use in social work literature, Dudley’s (2000) definition provides an excellent stance from which to develop an understanding of stigma.

It is important to recognize that most conceptualizations of stigma do not focus specifically on mental health or drug use disorders (e.g., Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998; Goffman, 1963). Stigma is relevant in other contexts such as towards individuals of varied backgrounds including race, gender, and sexual orientation. Thus, it is important to provide a definition of mental disorders, which also include drug use disorders, so that it can be understood in relationship to stigma. While each mental health and drug use disorder has a precise definition, the often cited and widely used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Ed., Text Revision [DSM-IV-TR]; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000) offers a specific definition of mental disorder which will be used to provide meaning to the concept. In this text, a mental disorder is a “clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in an individual and that is associated with present distress or disability or with a significantly increased risk of suffering death, pain, disability, or an important loss of freedom,” which results from “a manifestation of a behavioral, psychological, or biological dysfunction in the individual” (APA, 2000, p. xxxi). While this definition provides a consistent base from which to begin understanding how stigma impacts individuals with mental health and drug use disorders, it is important to recognize the inherent danger in relying too heavily on specific mental health diagnoses as precise definitions (Corrigan, 2007), which is why the term is being used just as a basis for understanding in this context.

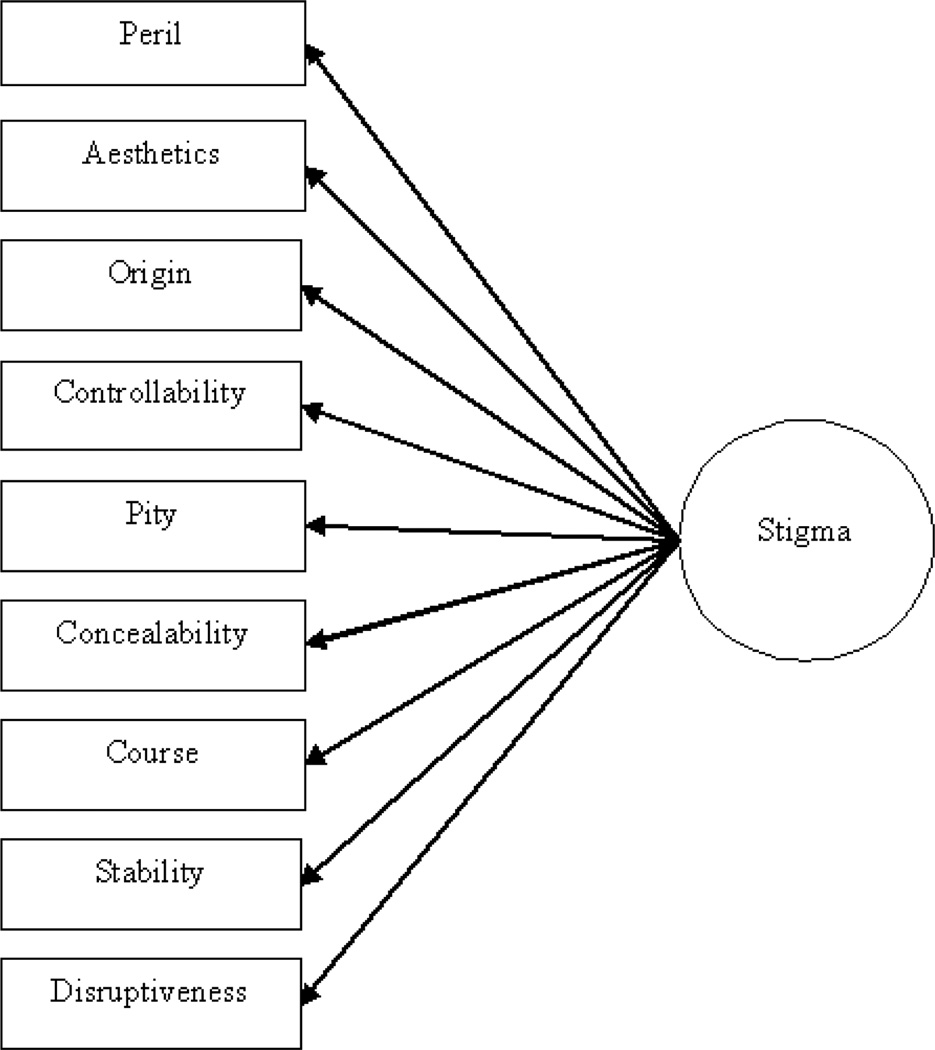

The next important step is to understand the constructs underlying the concept of stigma. These constructs detail the multiple pathways through which stigma can develop. Building from Goffman’s initial conceptualization, Jones and colleagues (1984) identified six dimensions of stigma. These include concealability, course, disruptiveness, peril, origin, and aesthetics (Feldman & Crandall, 2007; Jones et al, 1984). In addition, Corrigan and colleagues (2001; 2000) identified dimensions of stability, controllability, and pity. It is important to understand that these dimensions can either present independently or simultaneously to create stigma. Further, stigma is more than a combination of these elements impacting each person as an individual, since stigma is believed to be common in the structural framework of society (Feldman & Crandall, 2007).

The first dimension of stigma is peril – otherwise known as dangerousness. Peril is often considered an important aspect in stigma development, and it is frequently cited in the research literature (Corrigan, et al, 2001; Feldman & Crandall, 2007; Angermeyer & Matschinger, 1996). In this instance, the general public perceives those with mental disorders as frightening, unpredictable, and strange (Lundberg, Hansson, Wentz, & Bjorkman, 2007). Corrigan (2004) also suggests that fear and discomfort arise as a result of the social cues attributed to individuals. Social cues can be evidenced by psychiatric symptoms, awkward physical appearance or social-skills, and through labels (Corrigan, 2004; Link, Cullen, Frank, & Wozniak, 1987; Corrigan, 2007). This particular issue highlights the dimension of aesthetics or the displeasing nature of mental disorders (Jones, et al, 1984). When society attributes, upon a person or group of people, perceived behaviors that do not adhere to the expected social norms, discomfort can be created. This often leads to the generalization of the connection between abnormal behavior and mental illness, which may result in labeling and avoidance. This also may be why society continues to avoid those with mental and behavioral disorders whenever possible (Corrigan, Markowitz, Watson, Rowan, & Kubiak, 2003).

Another dimension of stigma that is often discussed in the research on stigma is origin. As in the definition provided earlier, mental and behavioral disorders are often believed to, at least in-part; develop from biological and genetic factors – i.e., origin (APA, 2000). This has direct implications for the dimension of controllability (Corrigan, et al, 2001). Within this dimension, it is often believed in society that mental and behavioral disorders are personally controllable and if individuals cannot get better on their own, they are seen to lack personal effort (Crocker, 1996), are blamed for their condition, and seen as personally responsible (Corrigan, et al, 2001).

A recent report by Feldman and Crandall (2007), found that individuals with disorders such as pedophilia and cocaine dependence were much more stigmatized than those with disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder. This supports the controllability hypothesis in which pedophilia and cocaine dependence could be viewed as more controllable in society than a disorder believed to be caused by a traumatic experience (PTSD). It also supports the pity dimension, in which disorders that are pitied to a greater degree are often less stigmatized (Corrigan, et al, 2000; Corrigan, et al, 2001). In this case, individuals within a culture or society may have more sympathy for disorders that are perceived as less controllable (Corrigan, et al, 2001).

Concealability, or visibility of the illness, is a dimension of stigma that parallels controllability, but also provides other insight into the stigmatization of mental and behavioral disorders. Crocker (1996) suggests that stigmatized attributes such as race can be easily identified, and are less concealable, allowing society to differentiate and stigmatize based on the visibility of the person. This is supported by research that shows that society attributes more stigmatizing stereotypes towards disorders such as schizophrenia, which generally have more visible symptoms, compared to others such as major depression (Angermeyer & Matschinger, 2005; Lundberg, et al, 2007).

The final three dimensions, course, stability, and disruptiveness, also may have some similarities among each other and compared to the others presented. Course and stability question how likely the person with the disability is to recover and/or benefit from treatment (Corrigan, et al, 2001; Jones, et al, 1984). Further the disruptiveness dimension assesses how much a mental or behavioral disorder may impact relationships or success in society. While disorders are frequently associated with an increased risk for poverty, lower socioeconomic status and lower levels of education (Kohn, Dohrenwend, & Mirotznik, 1998), the stability and disruptiveness of the conditions have implications as to whether an individual will be able to hold down a successful job and engage in healthy relationships, as evidenced by differences in stigma based on social class status. This demonstrates that if disorders are less disruptive, in which case they may be perceived as more stable, they are also less stigmatized (Corrigan, et al, 2001). This also expresses that some flexibility exists within each type of mental or behavioral disorder, as each diagnosed person is not stigmatized to the same extent (Crocker, 1999). Figure 1 depicts stigma as a latent variable constructed from the dimensions discussed above.

Figure 1.

The dimensions of stigma

3. Levels of Stigma: Theory & Epistemology

Illustrating the constructs underlying the formation of stigma helps us understand three specific levels of stigma – social stigma, self-stigma, and professional stigma. In this context, ‘levels’ does not refer to a hierarchy of importance for these varied stigmas, but rather to represent different social fields of stigma that can be differentiated from each other. In addition, further definition and theory behind these three ‘levels’ of stigma must be presented. First, stigmatized attitudes and beliefs towards individuals with mental health and drug use disorders are often in the form of social stigma, which is structural within the general public. Second, social stigma, or even the perception that social stigma exists, can become internalized by a person resulting in what is often called self-stigma. Finally, another, less studied level of stigma is that which is held among health professionals toward their clients. Since health professionals are part of the general public, their attitudes may in part reflect social stigma; however, their unique roles and responsibility to ‘help’ may create a specific barrier. The following theories are presented as an aid to understanding how each ‘level’ of stigma may develop in society.

Social Stigma

The first, and most frequently discussed, ‘level’ is social stigma. Social stigma is structural in society and can create barriers for persons with a mental or behavioral disorder. Structural means that stigma is a belief held by a large faction of society in which persons with the stigmatized condition are less equal or are part of an inferior group. In this context, stigma is embedded in the social framework to create inferiority. This belief system may result in unequal access to treatment services or the creation of policies that disproportionately and differentially affect the population. Social stigma can also cause disparities in access to basic services and needs such as renting an apartment.

Several distinct schools of thought have contributed to the understanding of how social stigma develops and plays out in society. Unfortunately, to this point, social work has offered limited contributions to this literature. Nonetheless, one of the leading disciplines of stigma research has been social psychology. Stigma development in most social psychology research focuses on social identity resulting from cognitive, behavioral, and affective processes (Yang, Kleinman, Link, Phelan, Lee, & Good, 2007). Researchers in social psychology often suggest that there are three specific models of public stigmatization. These include socio-cultural, motivational, and social cognitive models (Crocker & Lutsky, 1986; Corrigan, 1998; Corrigan, et al, 2001). The socio-cultural model suggests that stigma develops to justify social injustices (Crocker & Lutsky, 1986). For instance, this may occur as a way for society to identify and label individuals with mental and behavioral illnesses as unequal. Second, the motivational model focuses on the basic psychological needs of individuals (Crocker & Lutsky, 1986). One example of this model may be that since persons with mental and behavioral disorders are often in lower socio-economic groups, they are inferior. Finally, the social cognitive model attempts to make sense of basic society using a cognitive framework (Corrigan, 1998), such that a person with a mental disorder would be labeled in one category and differentiated from non-ill persons.

Most psychologists including Corrigan and colleagues (2001) prefer the social cognitive model to explain and understand the concept of stigma. One such understanding of this perspective – Attribution Theory – is related to three specific dimensions of stigma including stability, controllability, and pity (Corrigan, et al, 2001) that were discussed earlier. Using this framework, a recent study by these researchers found that the public often stigmatizes mental and behavioral disorders to a greater degree than physical disorders. In addition, this research found stigma variability based on the public’s “attributions.” For example, cocaine dependence was perceived as the most controllable whereas ‘mental retardation’ was seen as least stable and both therefore received the most severe ratings in their corresponding stigma category (Corrigan, et al, 2001). These findings suggest that combinations of attributions may signify varying levels of stigmatized beliefs.

Sociologists have also heavily contributed to the stigma literature. These theories have generally been seen through the lens of social interaction and social regard. The first of these theorists was Goffman (1963) who believed that individuals move between more or less ‘stigmatized’ categories depending on their knowledge and disclosure of their stigmatizing condition. These socially constructed categories parallel Lemert’s (2000) discussion on social reaction theory. In this theory, two social categories of deviance are created including primary deviance, believing that people with mental and behavioral disorders are not acting within the norms of society, and secondary deviance, deviance that develops after society stigmatizes a person or group. Similarly, research demonstrating that higher levels of stigmatization are attributed towards individuals with more “severe” disorders (Angermeyer & Matschinger, 2005) also resembles these hierarchical categories and the disruptiveness and stability dimensions of stigma.

Furthermore, Link and Phelan clearly illustrated the view of sociology towards stigma in their article titled Conceptualizing Stigma (2001). Link and Phelan (2001) argue that stigma is the co-occurrence of several components including labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination. First, labeling develops as a result of a social selection process to determine which differences matter in society. Differences such as race are easily identifiable and allow society to categorize people into groups. The same scenario may occur when society reacts to the untreated outward symptoms of several severe mental illnesses; i.e., Schizophrenia. Labels connect a person, or group of people, to a set of undesirable characteristics, which can then be stereotyped. This labeling and stereotyping process gives rise to separation. Society does not want to be associated with unattractive characteristics and thus hierarchical categories are created. Once these categories develop, the groups who have the most undesirable characteristics may become victims of status loss and discrimination. The entire process is accompanied by significant embarrassment by the individuals themselves and by those associated with them (Link & Phelan, 2001).

While social psychology and sociology are the primary contributors to the stigma literature, other disciplines have provided insight as well. Communications, Anthropology, and Ethnography all favor theories that revolve around threat. In Communications literature, stigma is the result of an “us versus them” approach (Brashers, 2008). For example, the use of specific in-group language can reinforce in-group belongingness as well as promote out-group differentiation (Brashers, 2008). This is referenced in research on peer group relationships such that youth often rate interactions with their same-age peers more positively than with older adults (whether family members or not) (Giles, Noels, Williams, Ota, Lim, Ng, et. al., 2003). This can also be applied to those with mental disorders in that individuals in the out-group (mental disorders) are perceived less favorably than the non-ill in-group.

Anthropology and Ethnography also prefer the identity model. From this perspective, the focus is on the impact of stigma within the lived experience of each person. Stigma may impact persons with mental illnesses through their social network, including how it exists in the structures of lived experiences such as employment, relationships, and status. Further, the impact of stigma is a response to threat, which may be a natural or tactical self-preservation strategy. However, it only worsens the suffering of the stigmatized person (Yang, et al, 2007). It is important to note again that while many disciplines have been leaders in social stigma theory, social work-specific literature has been mostly void of discussion on this topic. This is particularly unusual, since stigma is an obvious factor that impacts the lives of social work clients on a daily basis.

Self-Stigma

Crocker (1999) demonstrates that stigma is not only held among others in society but can also be internalized by the person with the condition. Thus, the continued impact of social/public stigma can influence an individual to feel guilty and inadequate about his or her condition (Corrigan, 2004). In addition, the collective representations of meaning in society – including shared values, beliefs, and ideologies – can act in place of direct public/social stigma in these situations (Crocker & Quinn, 2002). These collective representations include historical, political, and economic factors (Corrigan, Markowitz, and Watson, 2004). Thus, in self-stigma, the knowledge that stigma is present within society, can have an impact on an individual even if that person has not been directly stigmatized. This impact can have a deleterious effect on a person’s self-esteem and self-efficacy, which may lead to altered behavioral presentation (Corrigan, 2007). Nonetheless, Crocker (1999) highlights that individuals are able to internalize stigma differently based on their given situations. This suggests that personal self-esteem may or may not be as affected by stigma depending on individual coping mechanisms (Crocker & Major, 1989).

Similarly, other theories have provided insight into the idea of self-stigma. In modified labeling theory, the expectations of becoming stigmatized, in addition to actually being stigmatized, are factors that influence psychosocial well-being (Link, Cullen, Struening, Shrout, & Dohrenwend, 1989). In this context, it is primarily the fear of being labeled that causes the individual to feel stigmatized. Similarly, Weiner (1995) proposed that stigmatized beliefs provoke an emotional response. This can be interpreted from the standpoint of the afflicted individual, such that he or she may feel stigmatized and respond emotionally with embarrassment, isolation, or anger.

Health Professional Stigma

It may seem unlikely that social workers and other health professionals would carry stigmatized beliefs towards clients; especially those whom they know are affected by a variety of barriers to treatment engagement. Nonetheless, recent literature is beginning to document the initial impact of health professional stigma (Nordt, Rössler, & Lauber, 2006; Volmer, Mäesalu, & Bell, 2008). While limited evidence exists specifically on social worker attitudes, pharmacy students who desire more social distance towards individuals with Schizophrenia are also less willing to provide them medications counseling (Volmer, et al, 2008). In addition, one Swiss study (psychiatrists, nurses, and psychologists) found that mental health professionals did not differ from the general public on their desired social distance from individuals with mental health conditions (Nordt, et al, 2006). Other studies have also come to similar conclusions (Lauber, et al, 2006; Tsao, Tummala, & Roberts, 2008; Sriram & Jabbarpour, 2005; Ücok, Polat, Sartorius, Erkoc, & Atakli, 2004). Clients have also reported feeling ‘labeled’ and ‘marginalized’ by health professionals (Liggins & Hatcher, 2005). Individuals with mental illnesses may not even receive equivalent care (compared to non-mentally ill patients) in general health settings once health professionals become aware of their mental health conditions (Desai, Rosenheck, Druss, & Perlin, 2002).

Theory on health professional stigma is very limited, but some literature does provide insight into its possible development. In one way, stigma by health professionals may develop very much the same as the social stigma evident in the general public. Social workers may develop their own biases from their upbringing or even from burnout in their own working roles, particularly when working with individuals who have severe and persistent mental illnesses (Acker & Lawrence, 2009). Nonetheless, some indications suggest that health professional stigma may also develop in a unique way. For instance, social workers and other health professionals, similar to persons in the general public, experience their own mental health and drug use problems and often have friends or family members who experience these same issues (Siebert, 2004; Fewell, King, & Weinstein, 1993). Individuals may also self-select into a helping profession due in part to these experiences (Stanley, Manthorpe, & White, 2007). When social workers and other health professionals deal with mental health and drug use problems they may experience burnout and/or become more or less likely to recognize similar problems among their clients (Siebert, 2003). Some research suggests that mental health conditions are more prevalent among helping professionals than in the general public (Schemhammer, 2005). This problem has also been shown to impair professional social work practice behaviors (Siebert, 2004; Sherman, 1996). For example, Siebert (2003) found that social workers who used marijuana were less likely to recognize marijuana use as a problem among their clients.

The counter-transference that can develop as a result of personal experiences or behaviors may impact clients who may be vulnerable when participating in treatment and may not have the appropriate resources to determine when they are not being treated adequately (Siebert, 2004; Hepworth, Rooney, & Larsen, 2002; Rayner, Allen, & Johnson, 2005). Clients may also be disenfranchised by the treatment process and become more likely to end current treatment and less likely to seek treatment in the future. This creates a barrier to the overall well-being of individuals by preventing adequate treatment, but it also may impact the acknowledgement of their disorder. Overall, health professionals may not provide adequate intervention, early detection, or community referral options for individuals with mental or behavioral disorders (Gassman, Demone, & Albilal, 2001; Tam, Schmidt, & Weisner, 1996), because of their own stigmatizing beliefs and personal histories (Siebert, 2004; 2005).

4. Implications for Social Work

While it is apparent that stigma (all three levels) impacts individuals’ lives, there are also several implications for stigma and health professionals. These implications are placed into context within social work practice, education, policy, and research. In practice, social workers make up between 60–70 percent of mental health professionals in the United States (Proctor, 2004). While their roles may vary in different countries, they can nonetheless be important participants in mitigating stigma across the world. Since social workers often provide gatekeeping and triage functions in their roles, they are among the first to be in contact with individuals with psychiatric conditions (Hall, et al, 2000). Their attitudes and treatment preferences in practice settings can thus either promote or disenfranchise treatment seeking among their clients.

Social workers may be able to address issues of stigma within themselves by recognizing and embracing values and personal biases. This may be a difficult transformation that requires significant personal work and/or therapy. They may also be able to work with their clients on issues of stigma through their treatment provisions, triage roles, and outreach efforts. Nonetheless, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics mandates that professionals promote self-determination, client rights, self-realization, empowerment, social justice, and the dignity and worth of every person (National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 1999). These specific professional values pointedly call social workers to work to mitigate their own levels of stigma and work with others to dispel levels of social stigma and self-stigma.

While social workers have the opportunity to work with individuals, they also work with families. One additional way social workers may seek to mitigate social stigma on a micro-level is via the family. Family therapy may help relatives understand psychiatric conditions and how they can help/support the afflicted individual (Lefley, 1989). Some research suggests that more attention to families of individuals with mental health conditions is needed (Thornicroft, Brohan, Kassam, & Lewis-Holmes, 2008). If social workers are able to support an individual’s support system (family), it may help improve treatment seeking and treatment engagement for that person. Several studies have demonstrated the positive impact between family interventions and treatment engagement by the afflicted individual (Copello, Velleman, & Templeton, 2005; Adeponle, Thombs, Adelekan, & Kirmayer, 2009; Glynn, Cohen, Dixon & Niv, 2006). While this does not replace group work or individual work with a particular client, families may be among the most stigmatizing groups towards the afflicted person (Lee, Lee, Chiu, & Kleinman, 2005), and improved efforts towards the family system may be helpful.

On a macro level, social workers can also be instrumental in leading larger targeted educational efforts aimed at reducing stigma. Targeted programs have shown effectiveness in challenging misconceptions, improving attitudes, and reducing social distance (Thornton &Wahl, 1996; Esters, et al, 1998; Corrigan, et al, 2001). One such program, lead by the network of the World Psychiatric Association, has focused on individuals that impact the larger structural attitudes of stigma such as medical personnel, police officers, and journalists (Thornicroft, et al, 2008s). Large macro-level stigma campaigns that can be facilitated by social workers include public advertisements, targeted educational efforts, and advocacy for agency change. Occasionally, other systematic changes need to accompany these targeted efforts (Pinfold, Huxley, Thornicroft, Farmer, Toulmin, & Graham, 2003), but they have shown effectiveness and are important in mitigating stigma around the world. Nonetheless, more interventions and strategies must be developed to mitigate stigma in society.

Another important way to impact stigma is by educating individuals that have an opportunity to make a difference – i.e., social work education. For instance, when individuals have contact with those with mental illnesses, stigma can be diminished (Corrigan, et al, 2001). This may be the result of stereotypical beliefs about psychiatric conditions that are consistent with dimensions of stigma such as dangerousness or aesthetics (see, Jones, et al, 1984). Exposing social workers to these population groups may increase their willingness to treat the afflicted clients. This can be implemented through the field practicum experience at the undergraduate and graduate level. Education on stigma also fits into the practice sequences (macro- and micro- level), elective courses on substance abuse, and clinical diagnosis and assessment courses. Nonetheless, Bina and colleagues (2008) found that improving the knowledge and education of social workers about clients with drug use conditions will increase their interest in working with that population in practice. Furthermore, social work educational research has demonstrated that training social workers improves the likelihood that they will intervene, assess, and provide treatment for persons in an afflicted population, seek employment in that area, and feel confident and competent about their work (Amodeo, 2000).

Stigma is a global issue, and efforts to mitigate stigma through policy may be another effective strategy. On the macro-level, social workers can be very influential in advocating for policy change. Corrigan and colleagues (2001) suggest that policy change is one of the three strategies to mitigate stigma in society. For instance, stigma may impact lawmakers and permeate throughout government. One of the most important reasons why mental health care is not adequate is due to a lack of resources. In this case, it appears that economic factors may play a role in access to treatment. However, there is also a low priority placed on mental health within government and other funding bodies to support services (Knapp, Funk, Curran, Prince, Grigg, & McDaid, 2006). The WHO (2003) showed that while neuropsychiatric conditions make up 13 percent of the global burden of disease, only a median 2 percent of health care budgets in countries around the world are appropriated for mental illness. The lack of governmental support combined with the lack of support from other funding bodies (insurance companies) can in part be attributed to stigma (Knapp, et al, 2006). The debate about mental health parity in the United States is another example. Insurance companies in the U.S. have traditionally not funded mental health treatment to the same degree as general physical health illnesses (U.S. Surgeon General, 1999), which promotes that devaluation of mental illness in society. These disparate policies also act as a barrier to afflicted individuals and their ability to access social work services. Social workers and other policy makers can advocate for change in society. Social workers can be specifically instrumental in this process as they often serve disadvantaged populations such as those with mental illnesses, and should work to assist with the needs of their clients.

Social workers, as social scientists, are in position to develop research programs that seek to understand and influence stigma. More research is needed to understand the impact of different cultural traditions, attitudes, values, and beliefs on stigma, as it may vary between and within countries. This is also true among health professionals and their attitudes towards treating individuals in their community. As social scientists that practice and conduct research with different client populations, social workers have the ability to measure stigma among not only different race/ethnicity groups, but also in relation to individuals’ sexual orientation, gender, and age. In addition, limited research has specifically addressed the dimensions of stigma as discussed in the theoretical literature (Corrigan, et al, 2000; Jones, et al, 1984). More precise measures are needed to adequately assess stigma, across its varying dimensions and levels. The use of current stigma-related measures such as the Psychiatric Disability Attribution Questionnaire (Corrigan, et al, 2001) and the development of alternative scales to measure health professional stigma are needed to address dimensions of stigma across all three levels simultaneously. Also, larger studies of health professional stigma are needed, to understand how the attitudes of health professionals, and specifically social workers, influence treatment engagement and access.

5. Conclusions

Mental health conditions are pervasive around the world. In addition, the burden of these conditions is expected to grow over the next 20 years (Mathers & Loncar, 2006). Unfortunately, few individuals receive the psychiatric treatment they need, as individuals often do not seek services and frequently do not remain in care once they begin. The WHO (2001) has suggested that stigma is one of the largest barriers to treatment engagement, even though treatment has shown to be effective, even in low income countries (Patel, et al, 2007). While stigma remains evident in society, within individuals themselves, and among health professionals, the ethical problem of health professional stigma places an additional barrier on clients who seek needed mental health services.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) Institutional Training Award Grant (T32DA021129). The content in this manuscript is the sole responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA.

Footnotes

This text may be freely shared among individuals, but it may not be republished in any medium without express written consent from the authors and advance notification of White Hat Communications

References

- Acker GM, Lawrence D. Social work and managed care. Journal of Social Work. 2009;9(3):269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Adeponle AB, Thombs BD, Adelekan ML, Kirmayer LJ. Family participation in treatment, post-discharge appointment and medication adherence at a Nigerian psychiatric hospital. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;194:86–87. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.052217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th Ed., Text Revision) Washington, D.C: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amodeo M. The therapeutic attitudes and behavior of social work clinicians with and without substance abuse training. Substance Use Misuse. 2000;35(11):1507–1536. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Have their been any changes in the public’s attitudes towards psychiatric treatment? Results from representative population surveys in Germany in the years 1990 and 2001. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;111(1):68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. The effect of violent attacks by schizophrenic persons on the attitude of the public towards the mentally ill. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;43:1721–1728. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bina R, Harnek-Hall DM, Mollette A, Smith-Osbourne A, Yum J, Sowbel L, et al. Substance abuse training and perceived knowledge: predictors of perceived preparedness to work in substance abuse. Journal of Social Work Education. 2008;44(3):7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brashers D. Marginality, Stigma, and Communication. In: Donsbach W, editor. The International Encyclopedia of Communication. Blackwell Publishing; 2008. Retrieved on November 18, 2008, from Blackwell Reference Online: http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/tocnode?id=g9781405131995_chunk_g978140513199518_ss6-1. [Google Scholar]

- Copello AG, Velleman RDB, Templeton LJ. Family interventions in the treatment of alcohol and drug problems. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2005;24:369–385. doi: 10.1080/09595230500302356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. The impact of stigma on severe mental illness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1998;5:201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist. 2004;50(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. How clinical diagnosis might exacerbate the stigma of mental illness. Social Work. 2007;52(1):31–39. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC. Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30:481–491. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P, Markowitz F, Watson A, Rowan D, Kubiak MA. An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;44(2):162–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, Penn DL, Uphoff-Wasowski K, Campion J, et al. Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27(2):187–195. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, Wasowski KU, Campion J, Mathisen J, et al. Stigmatizing attributions about mental illness. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(1):91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J. Stigma. In: Antony SR, Hewstone M, editors. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. Blackwell Publishing; 1996. Retrieved November 18, 2008 from Blackwell Reference Online: http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/tocnode?id=g9780631202899_chunk_g978063120289921_ss1-54. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J. Social stigma and self-esteem: Situational construction of self-worth. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1999;35:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Lutsky N. Stigma and the dynamics of social cognition. In: Ainlay SC, Becker G, Coleman LM, editors. The dilemma of difference: A multidisciplinary view of stigma. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96:608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Fiske S, Gilbert D, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of social psychology. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Quinn DM. Psychological Consequences of Devalued Identities. In: Brown R, Gaertner S, editors. Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Intergroup Processes. Blackwell Publishing; 2002. Retrieved from Blackwell Reference Online on November 18, 2008 from http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/tocnode?id=g9781405106542_chunk_g978140510654214. [Google Scholar]

- Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB. Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1584. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley JR. Confronting stigma within the services system. Social Work. 2000;45:449–455. doi: 10.1093/sw/45.5.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esters LG, Cooker PG, Ittenbach RF. Effects of a unit of instruction in mental health on rural adolescents’ conceptions of mental illness and attitudes about seeking help. Adolescence. 1998;33:469–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DB, Crandall CS. Dimensions of mental illness stigma: What about mental illness causes social rejection. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26(2):137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fewell CH, King BL, Weinstein DL. Alcohol and other drug use among social work colleagues and their families: Impact on practice. Social Work. 1993;38:565–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassman RA, Demone HW, Albilal R. Alcohol and other drug content in core courses: Encouraging substance abuse assessment. Journal of Social Work Education. 2001;37(1):137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Giles H, Noels KA, Williams A, Ota H, Lim T, Ng SH, et al. Intergenerational communication across cultures: Young people's perceptions of conversations with family elders, non-family elders, and same-age peers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2003;18:32. doi: 10.1023/a:1024854211638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SM, Cohen AN, Dixon LB, Niv N. The potential impact of the recovery movement on family interventions for Schizophrenia: Opportunities and obstacles. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(3):451–463. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hall MN, Amodeo M, Shaffer HJ, Vander Bilt J. Social workers employed in substance abuse treatment agencies: A training needs assessment. Social Work. 2000;45(2):141–155. doi: 10.1093/sw/45.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth DH, Rooney RH, Larsen J. Direct social work practice: Theory and skills. 6th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo CJ, Boshoff DEL, Traut A, Zungu-Dirwayi N, Stein DJ. Community attitudes toward and knowledge of mental illness in South Africa. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38:715–719. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0695-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE, Farina A, Hastorf AH, Markus H, Miller DT, Scott RA. Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. New York: Freeman; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, Koch R, Laska EM, Leaf PJ, et al. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research. 2001;36:987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp M, Funk M, Curran C, Prince M, Grigg M, McDaid D. Economic barriers to better mental health practice and policy. Health Policy and Planning. 2006;21(3):157. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R, Dohrenwend BP, Mirotznik J. Epidemiologic findings on selected psychiatric disorders in the general population. In: Dohrenwend BP, editor. Adversity, Stress, and Psychopathology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 235–284. [Google Scholar]

- Lauber C, Nordt C, Braunschweig C, Rössler W. Do mental health professionals stigmatize their patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113:51–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee MTY, Chiu MYL, Kleinman A. Experience of social stigma by people schizophrenia in Hong Kong. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:153–157. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefley HP. Family burden and family stigma in major mental illness. American Psychologist. 1989;44(3):556–560. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemert E. How we got where we are: An informal history of the study of deviance. In: Lemert C, Winter M, editors. Crime and deviance: Essays and innovations of Edwin. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liggins J, Hatcher S. Stigma toward the mentally ill in the general hospital: a qualitative study. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2005;27(5):359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF. The social rejection of former mental patients: Understanding why labels matter. American Journal of Sociology. 1987;92:1461–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach in the area of mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:100–123. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg B, Hansson L, Wentz E, Bjorkman T. Sociodemographic and clinical factors related to devaluation/discrimination and rejection experiences among users of mental health services. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007;42:295–300. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. DC: Author; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH] The Numbers Count: Mental Disorders in America. 2006 Retrieved on June 18, 2010 from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/numbers.cfm#Intro.

- Nordt C, Rössler W, Lauber C. Attitudes of mental health professionals toward people with Schizophrenia and Major Depression. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(4):709. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2007;370(9591):991–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinfold V, Huxley P, Thornicroft G, Farmer P, Toulmin H, Graham T. Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: Evaluating an educational intervention with the policy force in England. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38:337–344. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK. Research to inform mental health practice: Social work’s contribution. Social Work Research. 2004;28:195–197. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner GC, Allen SL, Johnson M. Countertransference and self-injury: A cognitive-behavioural cycle. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;50(1):12–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemhammer E. Taking their own lives – The high rate of physician suicide. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(24):2473. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman MD. Distress and professional impairment due to mental health problems among psychotherapists. Clinical Psychology Review. 1996;16(4):299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert DC. Denial of AOD use: An issue for social workers and the profession. Health and Social Work. 2003;28(2):89–97. doi: 10.1093/hsw/28.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert DC. Depression in North Carolina social workers: Implications for practice and research. Social Work Research. 2004;28(1):30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert DC. Help seeking for AOD misuse among social workers: Patterns, barriers, and implications. Social Work. 2005;50(1):65–75. doi: 10.1093/sw/50.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram TG, Jabbarpour YM. Are mental health professionals immune to stigmatizing beliefs? Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:610. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley N, Manthorpe J, White M. Depression in the profession: Social workers� experiences and perceptions. British Journal of Social Work. 2007;37:281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Tam TW, Schmidt L, Weisner C. Patterns in the institutional encounters of problem drinkers in a community human services network. Addiction. 1996;91(5):657–670. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9156573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Kassam A, Lewis-Holmes E. Reducing stigma and discrimination: Candidate interventions. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2008;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton JA, Wahl OF. Impact of a newspaper article on attitudes toward mental illness. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tsao CIP, Tummala A, Roberts LW. Stigma in mental health care. Academic Psychiatry. 2008;32(2):70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.2.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ücok A, Polat A, Sartorius N, Erkoc S, Atakli C. Attitudes of psychiatrists towards patients with Schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2004;58:89–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Surgeon General. Rockville, Maryland: Center of Mental Health Services, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999. Mental health: A report of the U.S. Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- Volmer D, Mäesalu M, Bell JS. Pharmacy students’ attitudes toward and professional interactions with people with mental disorders. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2008;54(5):402–413. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. Judgements of Responsibility: A foundation for a theory of social conduct. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO] Investing in mental health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, WHO. World Health Report 2001. Mental health: new understanding, new hope. WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Lee S, Good B. Culture and stigma: Adding moral experience to stigma theory. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]