Abstract

The primary objective of this study was to identify and describe individual- and environmental-level factors that Peruvian adolescents perceive to be related to adolescent sexuality. A series of concept mapping sessions were carried out from January-March 2006 with 63 15–17 year olds from a low-income community near Lima in order for adolescents to (1) brainstorm items that they thought were related to sexuality (2) sort, group and rate items to score their importance for sexuality-related outcomes, and (3) create pathways from the groups of items to engaging in sex. Brainstorming resulted in 61 items, which participants grouped into 11 clusters. The highest rated clusters were personal values, respect and confidence in relationships, future achievements and parent-child communication. The pathway of decision-making about having sex primarily contained items rated as only moderately important. This study identified important understudied factors, new perspectives on previously-recognized factors, and possible pathways to sexual behavior. These interesting, provocative findings underscore the importance of directly integrating adolescent voices into future sexual and reproductive health research, policies and programs that target this population.

Introduction

Peru’s 5.8 million 10 to 19 year olds are the largest proportion of adolescents on record in the country’s history (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, 2005) and the most recent Peruvian census found that 10–14 and 15–19 year olds now represent the largest population age groups for both males and females (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, 2008). These adolescents need the tools and support to confront the hurdles and embrace the opportunities that they face during their development. Sexual and reproductive health is an arena where young people’s needs are particularly strong.

There is a vast literature on adolescent sexual and reproductive health, some of which assess the prevalence of different sexual behaviors while others examine associated factors (Anteghini, Fonseca, Ireland, & Blum, 2001; Brown, Jejeebhoy, Shah, & Yount, 2001; Gupta & Mahy, 2003; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 1999; Lloyd, Behrman, Stromquist, & Cohen, 2005; Podhisita, Xenos, & Varangrat, 2001). A recent review for the World Health Organization (WHO) summarized the risk and protective factors affecting the sexual and reproductive health of the diverse groups of adolescents that live in the highly diverse contexts of developing countries around the globe (Blum & Mmari, 2006). This review found that most studies focused on individual-level factors, including age, sex, age at puberty, family structure, socio-economic status and educational attainment, many of which are not easily changed through policies or interventions. This review underscores the need to examine additional individual-level factors that are more amenable to change, such as self-esteem, personal values, academic performance and future goals, as well as a broader range of family, household, peer, partner, and community-level factors. Inclusion of a range of factors is essential, considering that adolescent development is not an “inevitable unfolding of predetermined characteristics” (Blum, McNeely, & Nonnemaker, 2002), but instead represents the construction of self through interaction with the broader social environment (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998).

Further examination of these factors in the Peruvian context is critical given the changing context of adolescent sexuality and current trends in adolescent sexual and reproductive health. In Peru, as in other developing countries, there is now a greater likelihood of sexual initiation taking place prior to marriage (Lloyd et al., 2005). A large study with secondary school students aged 13–18 from nine cities found that 32 percent of males and 7 percent of females had ever had sex (Magnani, Seiber, Gutierrez, & Vereau, 2001). Studies in Lima demonstrated that between 37 and 43 percent of male adolescents and 6 and 13 percent of female adolescents are sexually experienced (Cáceres, 1999; Chirinos, Salazar, & Brindis, 2000;A.S. Quintana, 2002; Saravia, Apolinario, Morales, Reynoso, & Salinas, 1999).

This sexual activity is accompanied, however, by low sexuality-related knowledge (despite high perceived knowledge) and low contraceptive and condom use. The nine-city study found an index mean for sexual and reproductive health knowledge of 1.8 on a 5-point scale (Magnani et al., 2001) and a community-based study about the “sexual universe” of adolescents1 in Lima showed an average score of 6.3 for males and 6.6 for females on a 16-point scale about pregnancy, contraception and HIV/AIDS prevention (Cáceres, 1999).

Protective behaviors are also not being used. The “sexual universe” study found condom use at first intercourse to be 26 percent among sexually-active heterosexual males and 33 percent among sexually-active heterosexual females (Cáceres, 1999). In the nine-city study, 38 percent of sexually-active adolescent males and 26 percent of sexually-active adolescent females reported using a condom at first intercourse (Magnani et al., 2001). Findings from the 2004–2006 interim Peru Demographic and Health Survey (DHS/ENDES) showed much lower condom use among 15–19 year old females, at only 9 percent for ever use and 3 percent for current use (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Agencia de los Estados Unidos para el Desarrollo Internacional, & Programa Measure DHS+/ORC Macro, 2007). The Peruvian Ministry of Health found that in the last decade, the median age for AIDS cases declined to 31 years of age, with a median probable age of infection of 20 years of age. Additionally, people between 25 and 29 years of age constitute 21.9 percent of known AIDS cases (Ministerio de Salud, 2006). These trends suggest an increase in HIV infection during adolescence. Use of any type of modern contraceptive method was also low in this age group: 14 percent for ever use and 7 percent for current use (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática et al., 2007).

This context of sexual activity accompanied by low knowledge and low condom and contraceptive use contributes to current trend in adolescent health in Peru. Although the general fertility rate has declined markedly, the fertility rate for 15–19 year olds is persistently high, at 57.5 births per 1,000 women in 1995–2000 and down only slightly to 53.0 per 1,000 in 2000–2005 (Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas & Centro de Estudios de Población, 2005). This translates into 10.7 percent of adolescents at the national level who became mothers as of the year 2000, a minimal decrease from 10.9 percent in 1996 (Raguz, 2002). The adolescent abortion rate is approximately 23 abortions per 1,000 adolescent females (Singh, 1998) and a recent report estimated that 14 percent of the women who have abortions in Peru are under 20 years of age (Ferrando, 2002).

Although existing studies on adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Peru provide important information on adolescents’ sexuality-related attitudes and experiences, they also reveal significant gaps in knowledge of adolescents’ own perspectives (Arias & Aramburu, 1999; Cáceres, 1999; Chirinos et al., 2000; Magnani et al., 2001;A.S. Quintana, 2002; Sebastiani & Segil, 1999; Yon Leau, 1998). First, existing qualitative studies do not allow adolescents to describe the full context of their own sexuality, including the individual and non-individual level factors that adolescents think influence their behaviors. Second, and most relevant to the current study, quantitative studies have been constrained to a subset of factors with limited ability to assess additional antecedents (Kirby, 1999). Specifically, most studies do not include adolescent perspectives on which factors might affect their attitudes and behaviors, or new ways of conceptualizing existing factors, in order to allow a complete exploration of the entire universe of adolescent sexuality.

These limitations highlight the importance of engaging adolescents about the components and pathways of their sexual universes. Exploration of this universe requires taking a step back from “known” theoretical frameworks, factors and associations to open a space for adolescents to articulate their perspectives and contribute to theory building on the construction of adolescent sexuality. This involves going directly to adolescents, establishing rapport and building relationships with them, and providing a comfortable space and encouragement about the value of their beliefs and knowledge.

The primary goal of the research presented here was to use participant-oriented methods to gather adolescent perspectives. Specifically, adolescents were asked to 1) identify and describe individual- and environmental-level items and clusters of items that they perceive to be related to adolescent sexuality, 2) explore the relative importance of the items for different sexuality-related outcomes (having sex, having a boyfriend or girlfriend, using a condom), and 3) develop possible pathways from the clusters to the outcome of having sex.

Methods

Conceptual framework

Since the study aimed to allow concepts and constructs to emerge from participants, the theoretical framework was an initial one, to be modified and refined with the adolescents (Rossman & Rallis, 2003). In this framework, based on Bronfenbrenner’s social ecological perspective (1979), individuals are nested in interdependent and interactive environments or systems, each of which is contained in the other, from more proximate to more distal determinants (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1993). This framework is appropriate for understanding adolescent life experiences and sexuality since influences on adolescents come from multiple levels. The flexible definitions of the systems are also appropriate since they allowed for re-conceptualization of the different components of each system throughout the study.

Study setting

This study was conducted in Pampas de San Juan de Miraflores, one of the seven zones in the district of San Juan de Miraflores, which is one of Lima’s 43 districts. “Pampas,” established in the early 1980s, is made up of 46 human settlements (pueblos jóvenes) built around a cluster of sand hills located 25 kilometers south of metropolitan Lima. The majority of Pampas’ 57,000 residents live in poverty and, in many cases, extreme poverty (Municipalidad de San Juan de Miraflores, 2003). This site was selected given that 27.4 percent of the country’s adolescents reside in Lima and that the highest proportions of Limeño youth live in human settlements like Pampas (Ministerio de Salud, 2005). These settlements were first created by low-income populations migrating from the provinces of Peru to the capital during the 1950s and are now home to primarily low-income families born in the settlements themselves or in other parts of Lima and to a small number of new migrants from the Peruvian provinces. While the largest age group in Lima’s human settlements was previously children, it is now youth aged 15 to 24 (Riofrío, 2003). This site was also chosen because it provided a heterogeneous group of adolescents from different socio-economic levels whose family have different migration and life experiences. It was also possible to carry out community-based sampling, which was critical to ensuring the inclusion of in-school and out-of-school youth.

Study participants

A total of 63 15–17 year olds (32 females and 31 males) who reside in the low-income community of Pampas de San Juan de Miraflores participated in the study. Given the availability of a recent census of the community, random sampling was used to achieve a random community-based sample with in- and out-of-school youth. Participants were selected from household rosters and a random numbers table was used to generate three independent listings of female and male 15, 16 and 17 year olds. A total of 33 males and 33 females were selected, allowing for a non-response rate of 10 percent.

All participants provided their written assent and their parents/guardians provided their written permission after reviewing the consent form and having the opportunity to voice any questions or concerns to field workers. The research protocol and instruments were reviewed and approved by ethical review committees at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Asociación Benéfica PRISMA in September 2005 and November 2005, respectively.

Data collection activities

Concept mapping was the main methodology employed in this study. Concept mapping uses structured qualitative data collection steps to gather participant ideas and quantitative analytical tools to produce a pictorial representation that synthesizes the group’s ideas about the given topic, how these ideas are interrelated and which ideas are more relevant or important (Trochim, 1989). This method has been underutilized in the public health arena (J. G. Burke, O’Campo, Peak, Gielen, McDonnell, & Trochim, 2005) and its use with adolescents has been minimal.

The first strength of concept mapping, when compared to other qualitative group methods such as focus groups, is that participants are involved in and participate directly in all steps of the process, from identification of key issues and analysis of ideas to the determination of conclusions. This integration of participants throughout the process is possible since concept mapping draws on methodologies that are part of the participatory learning and action tradition, which enable participants to share, analyze and enhance their knowledge of their own lives and prioritize and act on this knowledge (Chambers, 1997). Second, concept mapping balances group consensus and individual- level contributions, since some steps (brainstorming, sorting) require group participation and others (rating) are done individually. Final strengths of concept mapping are that it is entirely in the language of the participants and provides visual products that are easy to interpret (J. G. Burke et al., 2005; O’Campo, Burke, Peak, McDonnell, & Gielen, 2005). All of these strengths – participant-driven, individual and group contributions, visual representations, and contributions to theory – made concept mapping appropriate for this population and set of research questions.

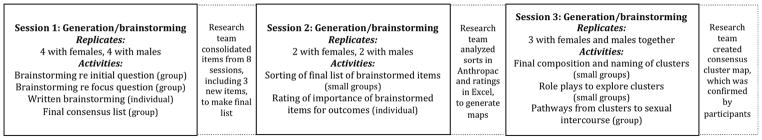

The five concept mapping steps employed in this study were as follows: preparation, generation, structuring, representation and interpretation (Trochim, 1989). During preparation, the research team held a pilot of the concept mapping sessions with participants from a previous study phase. During the pilot, participants formulated age- and language-appropriate questions for catalyzing brainstorming and offered suggestions to improve the different sessions. The remaining steps took place in replicates of three main sessions, described below and shown in Figure 1. Certain modifications that were made to the concept mapping methodology to make it more youth-friendly are specified in this description.

Fig. 1. Diagram of Concept Mapping Sessions and Data Analysis.

Concept mapping activities were carried out between January and March, 2006. The research team consisted of the first author, and one female and two male research assistants, all of whom have extensive experience working with adolescents in Lima. The first author and female assistant led the sessions with adolescent females and the male assistants led the sessions with adolescent males.

Session 1. Generation (brainstorming)

The goal of this session was to obtain a list of items that adolescents thought were related to adolescent sexuality. There were eight brainstorming sessions, four with females and four with males, with 6–10 participants in each group, for a total of 63 participants. Sessions were held separately for females and males in order to provide as comfortable a setting as possible for participants to talk about the sensitive issue of sexuality. Each session lasted approximately 1.5 hours.

The leader presented an initial question to ensure that participants had a solid understanding of the issue.

The initial question was:

What does sexuality mean to you?

(¿Qué significa sexualidad para ti?)

Since pilot participants frequently equated sexuality with having sexual intercourse, the objective of this question was to make sure that participants understood that sexuality encompasses how one thinks, acts and feels as a sexual being and includes attraction, flirting, kissing, hugging, hand holding, petting, having sex, and having a partner. It was important to reach agreement about a definition of sexuality so that, when asked the focus question, participants would think about factors that impact their sexuality, versus factors that influence only sexual intercourse.

The second, and focus question, centered in on the first study objective:

What are the factors or things that influence how you – and other people your age – live their sexuality?

(¿Qué son los factores o las cosas que influyen en como tú – y personas de tu edad – viven su sexualidad?)

The session leader recorded all participant responses to the initial and focus questions on paper that was visible to the entire group. Following the group activity, all participants received sheets of paper containing the focus question and two additional questions:

-

Why do some girls/boys your age have a boyfriend/girlfriend – and others don’t?

(¿Por qué unos chicos y chicas tienen enamorada o enamorado – y otros chicos y chicas no tienen?)

-

Why do some girls/boys your age have sex – and others don’t?

(¿Por qué unos chicos y chicas tienen relaciones sexuales – y otros chicos y chicas no tienen?)

The opportunity for participants to write responses individually was added after observing the non-participation of multiple participants in the first brainstorming session. It was integrated into the subsequent seven sessions as a method to make the brainstorming activities more youth-friendly since youth, especially in this context, often prefer to anonymously write versus publicly speak their ideas. This modification catalyzed the generation of additional items, including those that might be considered controversial or embarrassing, which were subsequently added to the original list of items together with participants. The final activity was to work with participants to eliminate duplicate or irrelevant items and ensure that nothing was missing.

Following the brainstorming sessions, the research team consolidated the items generated into a final list. Each session provided 25 to 30 items. After eliminating duplicate items, 76 items remained. The team added three items not mentioned by the participants but noted in previous studies in Peru and other settings as influential for adolescent sexuality: being a good student, showing that you are an adult, and fear of losing the relationship. Then, the team grouped together similar items under one item to create a final list of items.

Session 2: Structuring (sorting and rating)

The goal of this session was to sort and rate the items generated in the brainstorming sessions. Four sorting and rating sessions were held, two with females and two with males, with 12–15 participants in each session. All session one participants were invited, and 54 of the 63 returned. Each session lasted approximately 2.5 hours.

The first activity was a small-group sorting activity to capture how participants sorted the individual items generated in the brainstorms (Coxon, 1999; Rosenberg & Kim, 1975). Each item from the final list of brainstormed items was printed on a separate index card and a complete set of cards was given to participants, who worked in groups of 2–3. In concept mapping, sorting is usually carried out individually. For this study, given the large quantity of items (61), participants worked in small groups to make this activity more manageable and youth-friendly. Teams were asked to sort the cards in piles that made sense to them and, once the sorts were completed, create a name or label for each pile. The second activity was to rate each item. Each participant received a sheet that listed the 61 items and was asked to rate each item in terms of its importance to the outcome listed, having sexual intercourse, having a boyfriend/girlfriend, or using a condom. One example is, “how important do you think that curiosity (item 11) is for whether or not you and the adolescents you know have a partner (outcome 3)?” Ratings ranged from 1, not at all important/of little importance, to 5, very important. Each participant worked individually to rate one or two outcomes. Originally, it was anticipated that each participant would rate two outcomes. Given the distance from participants’ homes to the study location, there were often delays in the sessions. In these cases, participants rated one outcome.

Intermediate Step: Representation (initial data analysis)

During this analysis, the sorting data was used to determine the composition of the clusters and the rating data was used to determine the importance of each item and cluster versus other items and clusters. Anthropac (Analytic Technologies, 2004) was used to analyze the sorting data. The first analysis applied non-metric multidimensional scaling (Davison, 1983) to the sorts done by the small groups and generated a point map depicting the relationship between the items. The second analysis used hierarchical cluster analysis (Everitt, 1980) to partition the point map into clusters of items, where each cluster represents a separate domain and where all of the clusters together form a cluster map. Excel (Microsoft, 2003) was used to analyze the ratings done by each participant. The analysis was done by outcome. First, the individual ratings for the 61 items were entered into a spreadsheet and summed. Then, averages were calculated for the importance of each item relative to the given outcome. One example is the sum and average of all of the individual ratings for the importance of self-esteem (item 1) in whether or not adolescents have sexual intercourse (outcome 1). The distributions of the ratings were used to divide them into categories of high (items rated 4.1 or higher), moderate (items rated between 3.2 and 4.0) and low (items rated 3.1 or lower). Finally, cluster scores were calculated by adding up the average ratings of the items in each cluster and then calculating the average for the cluster. For example, for cluster 1, the averages of the individual ratings for self-esteem (item 1), feeling good about your body (item 20), maturity (item 24), personal values (item 39) and self-respect (item 61) for the outcome of have sexual intercourse were summed and then averaged in order to produce the cluster score for outcome 1.

Session 3: Additional Representation (initial data analysis) and Interpretation (role plays and pathway construction)

The goal of this session was to review session two results and discuss possible pathways from the items identified to sexual behaviors. Three sessions were held, mixed male-female, to make the activities as realistic as possible and allow dialogue that may not have emerged in the single-sex groups in the first two sessions. Each of the three 2.5-hour sessions included 17 participants, for a total of 51 participants.

The first activity was representation, or initial data analysis, during which the results from the sorting/rating data were shared with participants. The research team presented participants with the original solution of 12 clusters on brightly-colored poster board circles (to represent the clusters), each of which contained the corresponding items (on moveable pieces of paper). The use of poster board and moveable pieces of paper allowed the activities to be more youth-friendly (they are usually presented using a computer) and for participants to make modifications themselves, taking greater ownership over the results. Participants worked in groups of 4–5, accompanied by one of the session facilitators, to discuss the composition and arrangement of the clusters. Each small group was given three clusters that could be related to one another (for example, close environment, parent-child communication and negative household influences). First, they moved items from one cluster to another and combined clusters when they thought it was necessary in order to make the items in each cluster as similar to one another as possible. Then, they developed a name for each cluster based on the concept best represented by the final composition of items.

The second activity was interpretation. In past concept mapping research, this step has consisted of group discussion to confirm cluster groupings and labels (Baldwin, Kroesen, Trochim, & Bell, 2004; Trochim, 1989). Recent work by Burke et al (2005; 2009) extended the analysis to explore the mechanistic pathways between the factors identified and the outcome of interest through the creation of stories by participants (J. Burke, O’Campo, Salmon, & Walker, 2009;J. G. Burke et al., 2005). This study expanded on the precedent set by Burke et al by exploring the pathway from the clusters of items to sexual behaviors using a youth-friendly methodology, role plays. The goal of the role plays was to provide participants with the opportunity to present their perspectives on real life experiences by acting out concrete examples of the items they’d explored as abstract concepts during the other sessions. The participants received introductory scenarios and characters, as well as key questions, which were created by the research team and professionals from non-governmental organizations that work with adolescents in Lima. Each role play presented a situation that addressed one of the clusters from the cluster map. An example of what participants received follows. The characters are: Maria (an adolescent), her mother and her father. The introductory storyline is: Maria has had a boyfriend, Camilo, for four months. They’ve been seeing each other secretly and she hasn’t told her parents. Now she’s thinking about telling them. The key questions are: With whom does Maria talk – her mother, her father, or both? What does Maria say? How does her mother/father respond? What does Maria decide to do following the conversation? Participants worked in groups of 2–4 to discuss, prepare and present role plays that demonstrated how the scenario would be likely to play out among adolescents in their community. After each role play, all session participants discussed whether the content and outcome presented was a realistic representation of what would actually happen to adolescents they know and how they might modify what was presented, when relevant.

Following the role plays, the entire group reviewed the clusters created by the small groups to decide whether any further changes, such as moving additional items or changing cluster names, were necessary. All of the final clusters were then hung in view of all participants and they were asked to work together as a large group to discuss which clusters would enter into an adolescent’s decision to have sexual intercourse, and in what order. One participant held a posterboard with a drawing of an adolescent and at a certain distance, a second participant held a posterboard showing the outcome of sexual intercourse. Participants then selected and arranged the clusters to physically create a step-by-step decision-making pathway for the relationship between the adolescent and the outcome of having sex. This was carried out by additional participants holding one cluster each and other participants holding arrows to show the progression from one cluster to another and then to the outcome. Following the sessions, the research team synthesized the results from this final session to create a consensus cluster map of items that influence adolescent sexuality. This map was presented to ten adolescents for final confirmation.

Results

Participants’ socio-demographic characteristics, including age, birthplace (Lima or province), school status (on grade level, not on grade level, dropped out), current work status (working, not working), socioeconomic status (through proxy of floor material), and parental structure (both parents, mother only, father only), are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ Socio-demographic Characteristics, by sex

| Characteristics | Females (n=32) % (n) | Males (n=31) % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 15 years | 34.4 (11) | 38.7 (12) |

| 16 years | 31.2 (10) | 35.5 (11) |

| 17 years | 34.4 (11) | 25.8 (8) |

| Birthplace | ||

| Lima | 90.6 (29) | 80.7 (25) |

| Province | 9.4 [3] | 19.3 (6) |

| School status | ||

| Dropped out | 3.1 [1] | 9.7 [3] |

| Not on grade level | 25.0 (8) | 16.1 [5] |

| On grade level | 71.9 (23) | 74.2 (23) |

| Work status | ||

| Currently working | 90.6 (29) | 80.7 (25) |

| Does not work | 9.4 [3] | 19.3 (6) |

| Household wealth (floor) | ||

| Low (dirt, wood) | 9.7 [3] | 22.6 (7) |

| Medium (cement) | 77.4 (24) | 74.2 (23) |

| High (parquet, vinyl) | 12.9 [4] | 3.2 [1] |

| Parental structure | ||

| Both parents/figures | 71.9 (23) | 71.0 (22) |

| Mother/figure only | 25.0 (8) | 29.0 (9) |

| Father/figure only | 3.1 [1] | 0.0 [0] |

Sample sizes in [ ] are less than 5.

What affects adolescent sexuality?

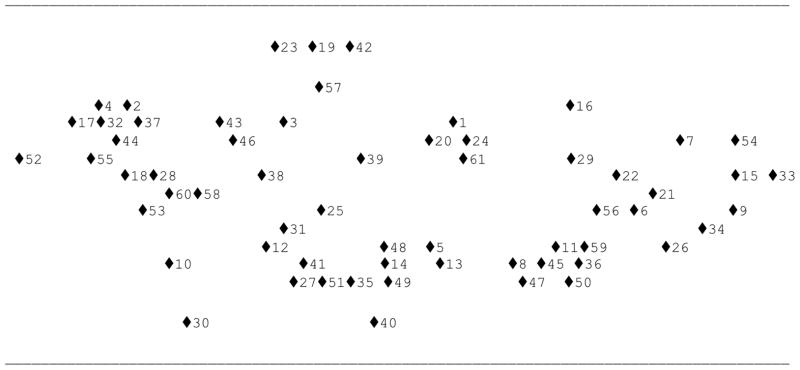

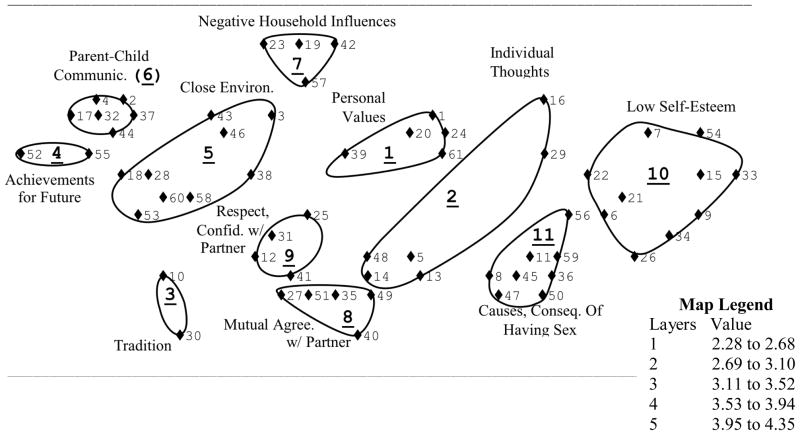

The final list of 61 items that participants named as impacting adolescent sexuality is shown in Table 2. The overall point map from the small groups’ sorting data is shown in Figure 2. Each number represents an item, and corresponds to the item number presented in Table 2. The distance between the items demonstrates the degree of similarity between those items. A higher degree of similarity means that the two items were sorted together by more groups of participants, and are therefore closer together on the map. For example, in Figure 2, items 1 and 24 were sorted together more times and by more groups than items 1 and 4. The cluster map divides the point map (Figure 2) into groups of items (clusters) that represent different conceptual spheres. Participants from the three sessions decided that the cluster map should contain 11, instead of the original 12, clusters, The consensus cluster map is shown in Figure 3.

Table 2.

| Ratings for each outcome (mean) 1 = no importance 5 = very high importance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Item name | Having sex | Having a partner | Using a condom |

| Item number | Cluster score | Cluster score | Cluster score | |

| Cluster 1. Personal Values / Valores Personales | 4.35 | 4.32 | 3.92 | |

| 1 | Self-esteem / Autoestima (saber valorarte) | High | High | High |

| 20 | Feeling good about your body / Sentirte bien con tu cuerpo | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| 24 | Maturity / Madurez | High | High | Moderate |

| 39 | Personal values / Valores personales | High | High | High |

| 61 | Self-respect / Respeto a ti mismo | High | High | Moderate |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 2. Individual Thoughts / Pensamientos Individuales | 3.36 | 3.44 | 3.45 | |

| 5 | Fear of losing the relationship / Miedo a perder la relación * | Low | Low | Low |

| 13 | Personal will/decision / Propia voluntad (querer hacerlo) | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| 14 | Feeling that it’s the right time / Sentir que es el momento adecuado | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 16 | Personality / Personalidad | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| 29 | Showing that you are an adult / Mostrar que eres adulto * | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| 48 | Feeling ready to do so / Sentirte preparado para hacerlo | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 3. Tradition / Tradición | 3.99 | 3.04 | 3.88 | |

| 10 | Religion/God / La religión/Dios | High | Moderate | High |

| 30 | Waiting for marriage / Esperar al matrimonio | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 4. Future Achievements / Logros para el Futuro | 4.18 | 3.88 | 3.58 | |

| 52 | Being a good student / Ser buen estudiante * | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 55 | Meeting your goals/objectives / Realizar tus metas/objetivos | High | Moderate | Moderate |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 5. Close Environment / Entorno Cercano | 3.67 | 3.42 | 3.4 | |

| 3 | Conversations/advice from friends / Conversaciones con / consejos de los amigos | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| 18 | Classes about sexuality in school / Clases sobre sexualidad en el colegio | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| 28 | Support/advice from teachers / Apoyo/consejos de profesores | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| 38 | Media influence / Influencia de los medios de comunicación | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 43 | The place where you live / El lugar en donde vives (tu barrio) | Low | Moderate | Low |

| 46 | Friends’ behaviors/experiences / Comportamientos/experiencias de los amigos | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 53 | Talking with friends about sexuality / Hablar con amigos y amigas sobre sexualidad | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 58 | Sharing things (emotions, problems) / Compartir cosas (emociones, problemas) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 60 | Level of knowledge about sexuality / Nivel de conocimientos sobre sexualidad | Moderate | Moderate | High |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 6. Parent-Child Communication / Comunicación entre Padres e Hijos | 4.11 | 3.94 | 3.78 | |

| 2 | Age / La edad que tengas | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| 4 | Talking with parents about sexuality / Hablar con los padres sobre sexualidad | High | Moderate | High |

| 17 | Love/warmth from parents / Amor/cariño de los padres | High | High | Moderate |

| 32 | How your parents raised you / Cómo te han formado tus padres | High | High | Moderate |

| 37 | Parental rules/control / Reglas/control de los padres | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 44 | Trust/communication with parents / Confianza/comunicación con los padres | High | Moderate | High |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 7. Negative Household Influences / Malas Influencias en el Hogar | 3.12 | 3.46 | 2.75 | |

| 19 | Fear of parents / Temor/miedo de los padres | Low | Low | Low |

| 23 | Obtaining greater freedom / Obtener mayor libertad | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| 42 | Absence of a parent / Ausencia de uno de los padres | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| 57 | Problems at home / Problemas en casa | Low | Moderate | Low |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 8. Mutual Agreements between Partners / Acuerdos Mutuos entre Parejas | 3.54 | 3.48 | 3.60 | |

| 27 | Partner’s characteristics (age, education) / Características de la pareja (edad, educación) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 35 | Amount of time with partner / Tiempo de relación con la pareja | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 40 | Wanting to have a child / Querer tener un hijo | Low | Low | Low |

| 49 | Having ideas that are similar to your partner’s / Tener ideas similares a la pareja | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 51 | Decision by both people / Decisión de las dos personas | High | High | Moderate |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 9. Respect and Confidence in a Partner Relationship / Respeto y Confianza en una Relación de Pareja | 4.32 | 4.33 | 4.25 | |

| 12 | How much you trust and know your partner / Cuánto confías y conoces a la pareja | High | High | High |

| 25 | Feeling affection/love / Sentir afecto/amor | High | High | High |

| 31 | Respect for your partner / Respeto a la pareja | High | High | High |

| 41 | Showing you love your partner / Mostrar que quieres a la pareja | Moderate | High | High |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 10. Low Self-Esteem / Baja Autoestima | 2.32 | 2.48 | 2.47 | |

| 6 | Machismo / Machismo | Low | Low | Low |

| 7 | Having fun/games / Diversión/juego/vacilón | Low | Low | Low |

| 9 | Consuming drugs or alcohol / Consumir drogas o alcohol | Low | Low | Low |

| 15 | Being popular / Ser popular | Low | Low | Low |

| 21 | Pornography use / Ver pornografía | Low | Low | Low |

| 22 | Not feeling alone / No sentirte solo/a | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| 26 | Rape / Violación | Low | Low | Low |

| 33 | Amount of money you have / Cuanta plata tengas | Low | Low | Low |

| 34 | Going to parties or nightclubs / Ir a fiestas o discotecas | Low | Low | Low |

| 54 | Not having an escape to feel better / No tener otra salida para sentirte mejor | Low | Low | Moderate |

|

| ||||

| Cluster 11. Causes and Consequences of Having Sexual Intercourse / Causas y Consecuencias de Tener Relaciones Sexuales | 3.03 | 3.30 | 3.13 | |

| 8 | Unintended pregnancy / Embarazo inesperado | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 11 | Curiosity / Curiosidad (para experimentar) | Low | Moderate | Low |

| 36 | Sexual urges / Deseo sexual (el cuerpo te lo pide) | Low | Low | Moderate |

| 45 | Pressure by partner / Presión de la pareja (prueba del amor) | Low | Low | Low |

| 47 | Sexually transmitted infections / Infecciones de transmisión sexual | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 50 | HIV / VIH | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 56 | Feeling more manly/masculine / Sentirte más varonil/más hombre | Low | Moderate | Low |

| 59 | Going with the moment / Dejarte llevar por el momento | Low | Low | Low |

Grouping of items into clusters was carried out in groups: initial sorting in groups of 2–3 during session 2, followed by confirmation of cluster arrangements in groups of 4–5 and then 17 during session 3.

Rating of items was carried out individually during session 2. Each participant rated all items for 1 or 2 outcomes.

These three items were added by the authors to the original list generated by participants, based on the literature.

Fig. 2. Point Map of Items that Influence Adolescent Sexualityc.

c/ Item numbers to right of diamond shapes.

Fig. 3. Cluster Map of Items that Influence Whether Adolescents Have Sexual Intercoursed.

d/ Cluster numbers in center of each cluster, underlined. Item numbers to right of diamond shapes.

The items and clusters demonstrate the broad range of factors that participants felt impact their sexuality and that of other adolescents. Clusters 1–4 contain 15 individual-level items that include current personal values, beliefs and thoughts, as well as goals for the future: cluster 1 has concepts such as general and body-related self-esteem, personal values, self-respect and maturity; cluster 2 includes items like personal will/decision and showing that you are an adult; cluster 3 holds beliefs in religion/God; and cluster 4 contains achievements and aspirations. Cluster 5 represents what adolescents perceived to be a very diverse close environment: friends, teachers, community and the media. Clusters 6 and 7, which relate to the parent-child relationship, contain parenting approaches such as communication, rules and warmth in cluster 6 and negative household influences like problems at home and absence of a parent in cluster 7. The 9 items in clusters 8 and 9 focus on the partner, with mutual agreements such as sharing similar ideas and making joint decisions in cluster 8 and items that represent confidence and affection in cluster 9. Cluster 10 contains items that participants identified as resulting from low self-esteem, including consuming drugs, being popular and machismo. The final cluster, cluster 11, shows the causes (curiosity, going with the moment, feeling more manly, sexual urges and pressure by partner) and consequences (STIs, HIV, unintended pregnancy) of having sex (see Table 2 and Figure 3).

Which items matter more for adolescent sexuality-related outcomes?

Participants’ ratings of the different items for the outcomes of having sexual intercourse, having a boyfriend/girlfriend and using a condom are presented in the right-hand side of Table 2. Feeling affection/love was the top-rated item for all outcomes except having a boyfriend or girlfriend, where self-respect rated highest. Other important items were self-esteem, personal values and talking with parents about sexuality, although the latter was not as influential for having a partner. Respect for your partner was of high importance for all outcomes and showing you love your partner was very important for having a boyfriend or girlfriend and for condom use. These findings underscore a certain prioritization of factors related to adolescent sexual behaviors: the need for affection is crucial above all else and individual values also play a critical role. Discussions with parents about sexuality are important, as is respecting and showing feelings for one’s partner.

The scores for each cluster relative to each outcome are presented in Table 2, to the right of the cluster name. In terms of the clusters, personal values (cluster 1), future achievements (cluster 4), parent-child communication (cluster 6) and respect and confidence in a partner relationship (cluster 9) had a strong to very strong relationship with all of the outcomes. The clusters related to individual thoughts (cluster 2), negative household influences (cluster 7), low self-esteem (cluster 10), and causes and consequences of having sex (cluster 11) had a moderate to weak relationship with the outcomes of interest. The cluster scores for the outcome of having sexual intercourse are presented visually and in three dimensions in Figure 3, where a higher number of layers is equivalent to a higher cluster score.

How do the items and clusters work in reality?

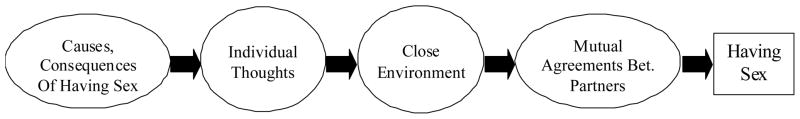

The role plays proved to be very useful in enabling participants to visualize and vocalize how the items and clusters work in day-to-day life before discussing possible pathways from the clusters to the outcome of having sexual intercourse. Participants from two sessions independently provided the same pathway (Figure 4, groups 1–2) while participants from the third session formulated a different, but similar, pathway (Figure 5, group 3). All groups stated that they would first consider the causes and consequences of having sex. Groups 1–2 said that the next cluster they would take into account was their individual thoughts, such as personal will/decision and feeling ready to do so. Group 3 felt that during this second step, they would be influenced by both negative household influences (absence of a parent, fear of parents) and their close environment (friends, teachers, the media). The first two groups also considered the close environment, but at the third step. All groups decided that their partners would enter in only at the final step of their decisions to have sex.

Fig. 4. Pathway from Clusters of Items to Having Sexual Intercourse, option 1.

Fig. 5. Pathway from Clusters of Items to Having Sexual Intercourse, option 2.

A comparison of the rating and pathway results shows contrasts between the importance of the clusters during the individual rating activities versus during the group pathway construction activities. The clusters that rated most highly in the individual ratings for all four outcomes of interest were those related to personal values (cluster 1), achievements for the future (cluster 4), parent-child communication (cluster 6), and respect and confidence in a partner relationship (cluster 9). In the group-generated pathways from the clusters to having sexual intercourse, however, only the last cluster (partner relationship, 9) was included, and in only one of the three pathway sessions. Additionally, this cluster was the one that adolescents would consider only in the last step of their decisions about whether to have sex. The most important cluster in the pathways according to all groups was the causes and consequences of having sex, which had only low to moderate importance during the individual rating activities. Other important factors within the pathway were individual thoughts, negative household influences, the close environment and mutual agreements between partners, which were also considered to be of only low to moderate importance in the individual ratings.

Discussion

Concept mapping can provide insights into adolescents’ perspectives about sexuality. The group brainstorming activities generated numerous items that were not considered in previous studies on adolescent sexuality in Peru and the highly diverse contexts of other developing country settings and that should be considered and measured in future studies. The sorting of these items by small groups of participants and rating of these items by each individual participant provided critical insights into how the items relate to one another and how important they are to different outcomes. The role play activities and related discussions and the pathways constructed by participants gave important information about how these items play out in the reality of adolescents’ lives.

This study has some limitations. Given the sensitive nature and societal norms around this topic, there may be social desirability bias, where adolescents provide responses that they think might please the facilitators or other participants (Gregson, Zhuwau, Ndlovu, & Nyamukapa, 2002). This bias emerged and was resolved to some degree during the role play activities, where participants openly questioned the validity of other participants’ role plays when they felt that they portrayed an inaccurate view of adolescent behaviors. Additionally, all of the information provided in the concept mapping activities was validated through a subsequent survey (data not shown), which was applied individually and therefore removed the tendency toward group norms that can exist in all group-based methodologies. Second, the study activities were carried out for adolescents as a group. It would be important to carry out similar activities to see whether adolescents create different clusters or rate different items as being important for females versus males and whether additional or different pathways emerge for females versus males. This is important considering that past studies in Peru have found that gender norms play a significant role among Peruvian youth, resulting in different standards for male and female sexuality (Arias & Aramburú, 1999, 2002; Cáceres, 1999;A.S. Quintana, 1999;A.S. Quintana & Vásquez, 1997). Differences by age (younger versus older adolescents) or other characteristics (socioeconomic status, for example) would also be important to examine. Further research should also explore possible reasons for the differences found in the importance of items and clusters in the individual (rating) versus group (pathway construction) activities. An additional consideration is that this study may not be generalizable to other populations. However, we have tried to provide inferential generalizability as proposed by Lewis and Ritchie (Lewis & Ritchie, 2003). By providing “thick description” of the overall study context, the specific study settings (low-income urban community of human settlements) and the participants (random, community-based sample with in- and out-of-school youth), as well as the methodology and the results, readers and researchers in other contexts will be able to decide to what degree they can infer or transfer these results to their setting. Finally, there were no references to non-heterosexual sexual experiences and identities in the concept mapping sessions, as might be expected in a study that focused on how adolescents themselves perceive the overall sexuality-related experiences of low-income adolescents, and moreso given that the activities were carried out in a group setting.

Despite these limitations, a series of important findings resulted from this study. At the individual level, study participants proposed the importance of exploring the different dimensions of self-esteem and personal values, concepts that have not been examined in sufficient detail in past developing country studies with adolescents. For example, a range of dimensions, including general, body-, peer- and family-related self-esteem, and the inclusion of various culturally-adapted items to represent each dimension, is important to creating a comprehensive construct to adequately measure self-esteem in a specific context. While other studies have measured self-esteem among adolescents in developing countries (e.g. (Anteghini et al., 2001; Magnani et al., 2001; Podhisita et al., 2001; Wyatt, Durvasula, Guthrie, LeFranc, & Forge, 1999), self-esteem has not been examined comprehensively in the Peruvian context, and this is the first study to suggest the importance of including body-related self-esteem in future studies on adolescents in developing countries. In addition, factors rated as very important by participants in this study, such as self-respect, honesty, personal responsibility and maturity, should be explored within and beyond the Peruvian context. The current study also revealed new items related to adolescent thought processes, including the importance they place on personal will and decisions and on personal opinions such as feeling ready to take certain actions and showing that you are an adult, all of which were of high to very high importance and are understudied.

Adolescent participants provided significant insights about academic performance and goals and objectives, issues that have been examined to a limited extent in and outside of Peru. The study of male adolescents in Lima, described in the introduction, found that participants who had repeated a grade were more likely to be sexually active than those who had not repeated a grade (Chirinos et al., 2000). Two other studies in Latin America, one with female adolescents in Mexico City and one with female and male adolescents in Ecuador, showed that respondents with higher educational aspirations were less likely to have had sex (Park, Sneed, Morisky, Alvear, & Hearst, 2002; Pick de Weiss, Atkin, Gribble, & Andrade-Palos, 1991). Adolescent participants in this study individually rated being a good student and meeting future goals and objectives as highly important to their sexuality, but during the role plays and related discussions, they highlighted the complexities related to future aspirations in the current context.

Although participants discussed in detail their goals of finishing high school, pursuing and completing post-secondary education, establishing a career, and obtaining a job, they reiterated a message provided by participants in a previous study phase: that adolescents from their community have only two possible life paths, 1. meet their goals and objectives and then look for a partner, or 2. have a partner while pursuing further education and/or obtaining work. This second path is often impossible since partner-related situations such as distractions and lack of support or, in the majority of cases, an unintended pregnancy may get in the way (Bayer, 2008). Adolescents’ perceptions regarding future opportunities affirm the value of combining the diverse methodologies that are part of concept mapping, particularly role plays and discussions, to obtain greater detail about adolescents’ perspectives. They also affirm the necessity for further study of these important issues.

Participants in this study grouped peers, teachers, the community and the media in the same cluster, which they termed their close environment. The placement of teachers, the community and the media in the close environment is not as common in past studies (Blum & Mmari, 2006). Additionally, this differs significantly from Bronfenbrenner’s model where family and peers are usually in the micro level (most proximate to the adolescent) and teachers/school, the community and the media are part of the more distal influences in the exo level. The research team talked with participants to ensure that they truly perceived all of these factors as having a close influence on their sexuality. Participants’ affirmation of this range of proximate influences may reflect their need for multiple options to help them affront the significant development- and sexuality-related challenges they face. A broader study by the same authors found that family problems, poverty and violence dominate adolescents’ lives in this community and that the full, healthy expression of their sexuality is constrained (Bayer, 2008). It is important to note that no past studies in Peru and very few past studies in developing countries have examined the relationship between adolescent sexuality and school-related dynamics and support (Anteghini et al., 2001; Mensch, Clark, Lloyd, & Erulkar, 2001; Slap, Lot, Huang, Daniyam, Zink, & Succop, 2003). The proximity of school and community according to adolescents in this study and the lack of previous research about these factors suggest the need for further examination of their influence on adolescent sexuality.

Other non-individual level items proposed by study participants relate to partners, a factor that has not been analyzed in many past developing country settings. The study of male adolescents in Lima analyzed partner communication about sex (Chirinos et al., 2000) and studies outside of Peru examined partner age and number and type of relationships (Wyatt et al., 1999), as well as partner age and the quality of the partner relationship (Gupta & Mahy, 2003). Adolescent participants in this study provided numerous additional factors, such as partners sharing similar ideas, and the value of respect, trust and mutual decisions. Participants decided that partner-related factors warranted two separate clusters and rated these factors as having high to very high importance for their sexuality. This confirms the importance of further consideration of partner-related factors in Peru and other developing countries.

Interesting findings emerge from a review of the pathway results. Although participants developed the pathways in three separate sessions, the similarities across the pathways confirm their reliability: the pathways were the same for participants from two different concept mapping sessions and very similar between those two groups and a third group from a third concept mapping session. The three groups’ consideration of the causes and consequences of having sex prior to any other cluster of items affirms adolescent participants’ recognition of adolescent sexuality (curiosity, sexual urges, going with the moment), but also underscores their association of acting on these sexuality-related feelings with solely negative consequences (STIs, HIV, unintended pregnancy). Fear of these consequences dissuades many adolescents from having sexual intercourse, or even having a partner. All three groups also took into account their close environment, during the third step in the case of two groups and during the second step in the third group. All of the groups decided that they would consider their partners in the last step of their decisions to have sex. The differences between the importance of the items during the individual rating activities versus their importance when discussed in a larger group for the pathway activities needs to be examined in greater depth to determine possible explanations. It is possible that these contrasts may be due to differences in individual ideas, generated in the rating activities, versus group norms, expressed in the pathway activities. Additionally, the rating activities focused on each of the items individually while the pathway activities considered the items after they have been grouped into clusters. Another possible explanation is that the rating activities were more abstract, since the participants were only rating the item, absent of further explanation or context, as compared to the pathway activities, which may have been more realistic since participants discussed and created the pathways immediately following the role play activities that placed the items and clusters of items into context in a concrete manner.

Concept mapping proved to be a highly effective method for engaging adolescents about their perspectives regarding sensitive and often taboo topics such as sexuality. The findings from the brainstorming, sorting/rating, role playing and discussion activities provide important new factors, and new perspectives on previously-recognized factors, as well as possible pathways between these factors and key sexual behaviors. The immediate utilization of these findings was the translation of the items into quantitative survey questions in order to validate the findings in a larger sample of the same population, an activity that was carried out jointly by the authors and select adolescents.

The results reported here are also useful for policy and programs. This study found that researchers have neglected certain areas and factors that are of critical importance in adolescent sexuality. Findings driven directly by the perspectives of adolescents themselves provide researchers, and in turn policymakers and program specialists, with potential pathways for generating culturally appropriate, adolescent-driven interventions in home, school and community settings. Key focus areas should include the development of self-esteem and personal values using a multi-faceted approach, expanded availability of future opportunities for young people, promotion of improved parent-child relationships, strengthening of adolescent relationships with teachers and of communities that are supportive of adolescents, and provision of education about healthy partner relationships.

Acknowledgments

Angela Bayer is currently a Postdoctoral Scholar with Dr. Thomas J. Coates, NIH NIMH grant T32MH080634-03. We are very grateful for the support and assistance of research assistants Danilo Climaco, Francisco Meza and Rosa Vidal and PRISMA field staff, especially Flor Pizarro, Rosalina Amaya, Rosario Jimenez, Marco Varela and Omar Cabrera. We are also grateful to the staff at the Santa Ursula Health Post, especially Dr. Juan Francisco Sanchez, and most of all, to the adolescents who shared their wisdom and experiences for this study.

Footnotes

The authors use the term “sexual universe” as employed by Dr. Carlos Cáceres (1999) to refer to the breadth and diversity of Peruvian adolescents’ sexual cultures and sexual experiences.

References

- Anteghini M, Fonseca H, Ireland M, Blum RW. Health risk behaviors and associated risk and protective factors among Brazilian adolescents in Santos, Brazil. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28(4):295–302. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias R, Aramburú CE. Uno Empieza a Alucinar … Percepciones de los jóvenes sobre sexualidad, embarazo y acceso a los servicios de salud: Lima, Cusco e Iquitos. Lima, Perú: Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arias R, Aramburú CE. Género, sexualidad y salud: Jóvenes rurales en Ayacucho. In: Cáceres CF, editor. La Salud Sexual Como Derecho en el Perú de Hoy: Ocho estudios sobre salud, género y derechos sexuales entre los jóvenes y otros grupos vulnerables. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin CM, Kroesen K, Trochim WM, Bell IR. Complementary and conventional medicine: a concept map. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer AM. The Context, Factors and Pathways related to Adolescent Sexuality in Lima, Peru. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW, McNeely C, Nonnemaker J. Vulnerability, risk, and protection. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(1 Suppl):28–39. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW, Mmari KN. Risk and Protective Factors Affecting Adolescent Reproductive Health in Developing Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of cognitive development: Research models and fugitive findings. In: Wozinak RH, Fischer K, editors. Development in Context: Acting and thinking in specific environments. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Lerner RM, editor. Handbook of Child Psychology. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 923–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Jejeebhoy SJ, Shah I, Yount KM. Sexual Relations Among Young People in Developing Countries: Evidence from WHO case studies. Occasional Paper WHO / RHR / 01.8. Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Burke J, O’Campo P, Salmon C, Walker R. Pathways connecting neighborhood influences and mental well-being: socioeconomic position and gender differences. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(7):1294–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, Trochim WM. An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research method. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(10):1392–1410. doi: 10.1177/1049732305278876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres CF. La (Re)Configuración del Universo Sexual. Lima, Perú: Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R. Whose Reality Counts? Putting the first last. London: Intermediate Technology Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chirinos JL, Salazar VC, Brindis CD. A profile of sexually active male adolescent high school studentsin Lima, Peru. Caderno de Saude Publica. 2000;16(3):733–746. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2000000300022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxon APM. Sorting Data: Collection and analysis. Sage University Papers on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07–127. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Davison ML. Multidimensional Scaling. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt B. Cluster Analysis. 2. New York: Halsted Press, A Division of John Wiley and Sons; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando D. El Aborto Clandestino en el Perú. Hechos y cifras. Lima, Perú: Centro de la Mujer Peruana Flora Tristán, Pathfinder International; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fondo de Población de las Naciones Unidas, & Centro de Estudios de Población. Salud Sexual y Reproductiva Adolescentes en el Comienzo del Siglo XXI en América Latina y el Caribe. Buenos Aires, Argentina: UNFPA -Equipo de Apoyo Técnico para América Latina y el Caribe, CENEP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Zhuwau T, Ndlovu J, Nyamukapa CA. Methods to reduce social desirability bias in sex surveys in low-development settings: experience in Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(10):568–575. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Mahy M. Sexual initiation among adolescent girls and boys: trends and differentials in sub-Saharan Africa. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32(1):41–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1021841312539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perú en Cifras. Lima, Perú: INEI; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perfil Sociodemográfico del Perú. Lima, Perú: INEI - Dirección Técnica de Demografía y Estudios Sociales y Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo; 2008. [Accessed September 1, 2009]. Available at http://censos.inei.gob.pe/Censos2007/ [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Agencia de los Estados Unidos para el Desarrollo Internacional, & Programa Measure DHS+/ORC Macro. Perú: Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar ENDES Continua 2004–2006. Lima, Perú: INEI, USAID, Measure DHS/ORC Macro; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Sex and Youth: Contextual factors affecting risk for HIV/AIDS. A comparative analysis of multi-site studies in developing countries. Geneva: UNAIDS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Looking for Reasons Why: The antecedents of adolescent sexual risk-taking, pregnancy and childbearing. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Ritchie J. Generalising from qualitative research. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative Research Practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CB, Behrman JR, Stromquist NP, Cohen B, editors. Growing Up Global: The changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Magnani RJ, Seiber EE, Gutierrez EZ, Vereau D. Correlates of sexual activity and condom use among secondary-school students in urban Peru. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32(1):53–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch BS, Clark WH, Lloyd CB, Erulkar AS. Premarital sex, schoolgirl pregnancy, and school quality in rural Kenya. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(4):285–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud. Perfil de la Población. Lima, Perú: MINSA -Oficina General de Estadística e Informática; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud. Análisis de la Situación Epidemiológica del VIH/SIDA en el Perú. Lima, Perú: MINSA -Dirección General de Epidemiología; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Municipalidad de San Juan de Miraflores. Plan de Desarrollo Integral de San Juan de Miraflores 2003–2012. Lima, Perú: Muni SJM -Equipo Técnico PDI; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- O’Campo P, Burke J, Peak GL, McDonnell KA, Gielen AC. Uncovering neighbourhood influences on intimate partner violence using concept mapping. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(7):603–608. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.027227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IU, Sneed CD, Morisky DE, Alvear S, Hearst N. Correlates of HIV risk among Ecuadorian adolescents. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14(1):73–83. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.1.73.24337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick de Weiss S, Atkin LC, Gribble JN, Andrade-Palos P. Sex, contraception, and pregnancy among adolescent in Mexico City. Studies in Family Planning. 1991;22(2):74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podhisita C, Xenos P, Varangrat A. The Risk of Premarital Sex among Thai Youth: Individual and family influences. East-West Center Working Papers, Population Series. No. 108-5. Honolulu, HI: East-West Center; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana AS. Construcción social de la sexualidad adolescente: Género y salud sexual. In: Cáceres CF, editor. Nuevos Retos: Investigaciones recientes sobre salud sexual y reproductiva de los jóvenes en el Perú. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana AS. Itinerarios de salud sexual y reproductiva de los y las adolescentes y jóvenes de dos distritos de Lima. In: Cáceres CF, editor. La Salud Sexual Como Derecho en el Perú de Hoy: Ocho estudios sobre salud, género y derechos sexuales entre los jóvenes y otros grupos vulnerables. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana AS, Vásquez E. Construcción de la Sexualidad Adolescente: Género y salud sexual. Lima, Perú: Instituto de Educación y Salud; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Raguz M. Salud Sexual y Reproductiva Adolescente y Juvenil: Condicionantes sociodemográficos e implicancias para políticas, planes y programas e intervenciones. Lima, Perú: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Riofrío G. The case of Lima, Perú. In: UN-Habitat, editor. Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements, 2003. London: Earthscan; 2003. pp. 195–228. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, Kim MP. The method of sorting as a data gathering procedure in multivariate research. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1975;10(4):489–502. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr1004_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman GB, Rallis SF. Learning in the Field: An introduction to qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; [Google Scholar]

- Saravia C, Apolinario H, Morales R, Reynoso B, Salinas V. Itinerario del acceso al condón en adolescentes de Lima, Cusco e Iquitos. In: Cáceres CF, editor. Nuevos Retos: Investigaciones recientes sobre salud sexual y reproductiva de los jóvenes en el Perú. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani A, Segil E. Qué hacen, qué piensan, qué sienten los y las adolescentes respecto a la salud sexual y reproductiva. In: Cáceres CF, editor. Nuevos Retos: Investigaciones recientes sobre salud sexual y reproductiva de los jóvenes en el Perú. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. Adolescent childbearing in developing countries: a global review. Stud Fam Plann. 1998;29(2):117–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slap GB, Lot L, Huang B, Daniyam CA, Zink TM, Succop PA. Sexual behaviour of adolescents in Nigeria: cross sectional survey of secondary school students. BMJ. 2003;326(7379):15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7379.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trochim WMK. An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1989;12:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt G, Durvasula RS, Guthrie D, LeFranc E, Forge N. Correlates of first intercourse among women in Jamaica. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1999;28(2):139–157. doi: 10.1023/a:1018767805871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yon Leau C. Género y Sexualidad. Una mirada de los y las adolescentes en cinco barrios de la ciudad de Lima. Lima, Perú: Movimiento Manuela Ramos; 1998. [Google Scholar]