Abstract

While numerous studies have explored adolescent sexual behavior in Peru, to date, none have explored how adolescents situate sexuality within the context of their broader lives. This information is needed to inform policies and programs. Life history interviews were conducted with 20 12–17 year-old females and males from a low-income settlement near Lima, Peru. Data were analyzed using holistic content analysis and grounded theory. Sexuality had a strong presence in adolescents’ lives. However, adolescents viewed the complete expression of their sexuality as a constrained choice. Constraints are due to the belief that sexual intercourse always results in pregnancy; the nature of sex education; the provision of proscriptive advice; and the family tensions, economic problems, racism and violence present in adolescents’ lives. Social and cultural factors seem to surpass and often suppress the physical and psychological dimensions of adolescents’ sexuality. The results of this study can inform policies and programs to support adolescents as they construct their sexuality and make sexuality-related decisions.

Keywords: Adolescents, Sexuality, Qualitative, Life History, Peru

Introduction

There is a vast literature on adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries and a sizeable literature on Peruvian adolescents. Existing studies in Peru analyze adolescents’ perspectives on sexuality-related terminologies and messages (Cáceres 1999) and their attitudes toward sexual intercourse (Arias and Aramburú 1999; Cáceres 1999; Sebastiani and Segil 1999), sexual and reproductive health “itineraries” (Quintana 2002; Quintana, Hidalgo, and Dourojeanni 2003), and contraceptive and condom use (Arias and Aramburú 1999; García, Cotrina, and Cárcamo 2008). They also examine adolescents’ experiences learning about sexual and reproductive health information (Arias and Aramburú 1999; Cáceres 1999; García, Cotrina, and Cárcamo 2008) and utilizing contraceptive distribution points (Saravia et al. 1999), their real and perceived knowledge about sexual and reproductive health (Cáceres 1999; Sebastiani and Segil 1999; Yon Leau 1998; García, Cotrina, and Cárcamo 2008), and the factors they perceive to impact their sexuality (Bayer, Cabrera et al. 2010). Although these studies provide important information on adolescents’ attitudes, experiences and knowledge, they share one commonality: from the outset, they establish sexuality as the primary issue of interest for the study, and as a result assert that sexuality is an issue of great interest to Peruvian adolescents.

The integration of adolescent perspectives into the determination of where sexuality fits into their broader lives is critical. A number of changes have occurred globally for adolescents. First, healthier entry into puberty, increased amount of time in school, postponed entry into the labor force, and the rising age of first marriage and childbearing have expanded the transition from childhood to adulthood. Second, globalization and urbanization have led to a greater likelihood of living in urban areas and smaller households, higher levels of education and increased connectivity, through roads, transport, media and the Internet (Lloyd et al. 2005). Finally, numerous changes have taken place to influence adolescent sexuality, including declining age of puberty, increased likelihood of premarital sexual activity, an increase in sexually transmitted infections and HIV and AIDS, and near universal knowledge of and access to some form of contraception (Blanc and Way 1998; Lloyd et al. 2005). These global transitions confirm the unique nature of the current adolescent experience, both in general and in the realm of sexuality, and underscore the importance of determining where present-day adolescents believe that sexuality fits in their general life universes before engaging with them programatically. This study uses life history interviews, an adolescent-driven, researcher-facilitated methodology to uncover the role of this broader context for the sexual lives of Peruvian adolescents.

Methods

Theoretical approach

This study employed the interactionist approach to sexuality and gender developed by Tolman and Diamond (2001), which emphasizes that biological, social, cultural and historical factors do not operate independently, but instead exert a shared influence on individuals’ sexuality (Tolman and Diamond 2001). Recent research on adolescent sexuality in Peru reflects global trends, as outlined by Tolman and Diamond (2001): studies that provide little information on the subjective quality of adolescents’ sexual feelings and experiences, instead focusing on analysis of sexual experiences and associated factors. The authors propose a modified approach to adolescent sexuality, which explores “not just whether factors such as gender, race, ethnicity and social class are statistically related to specific sexual behaviors, but how and why these factors bear a meaningful relationship to adolescents’ experiences of their sexuality” (Tolman and Diamond 2001) (p. 52). This is possible to achieve only when adolescents’ perspectives are included through participant-directed qualitative work.

Study setting

This study was conducted in Pampas de San Juan de Miraflores, one of the seven zones in the district of San Juan de Miraflores, which is one of Lima’s 43 districts. “Pampas,” established in the early 1980s, is made up of 46 young settlements (pueblos jóvenes) built around a cluster of sand hills located 25 kilometers south of metropolitan Lima. The majority of Pampas’ 57,000 residents live in poverty and overcrowded households and a significant number lack basic services such as water, electricity and sewage (Municipalidad de San Juan de Miraflores 2003). This site was selected since it is representative of urban adolescents in Peru. Peru’s 5.8 million 10 to 19 year olds represent the largest percentage of adolescents in the country’s history (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática 2005). Approximately 70 percent of Peruvian adolescents live in urban areas and over one-quarter (27.4%) of the country’s adolescents reside in Lima, with the highest proportions of youth living in peripheral areas and settlements like Pampas (Ministerio de Salud 2005).

Study participants

Twenty 12–17 year olds (5 12–14 year old females, 5 12–14 year old males, 5 15–17 year old females and 5 15–17 year old males) participated in the study. The sampling procedure was non-probabilistic since the aim was to seek out participants that symbolized features relevant to the study and that the sample was as diverse as possible within the boundaries of the defined population (Ritchie, Lewis, and Elam 2003). Participants were recruited through community-based organizations, which publicized the opportunity to adolescents in their respective catchment areas (not only to adolescents who participated in the organizations). Organizations were selected from different zones of Pampas, which represent different socio-economic levels. For example, zones located higher up the sand hills of Pampas tend to be home to people with very low to low socio-economic levels while low-lying zones house people with low to lower middle socio-economic levels. Organization leaders asked potential participants to provide their gender, age and school status. These criteria were considered due to gender differences and age-related developmental differences across the span of adolescence, particularly in the realm of sexuality. Sampling continued until there was a large enough sample size for each gender/age sub-group, with participants from different zones of Pampas in each sub-group. An effort was also made to include both in-school and out-of-school adolescents given differences between these two groups’ life experiences both overall and related to sexuality in past research on adolescents.

All participants provided their assent and their parents/guardians provided their permission prior to commencing data collection. Field workers read the consent form aloud with participants and their parents/guardians and encouraged them to voice any questions or concerns before asking for their respective signatures. The research protocol and instruments were reviewed and approved by ethical review committees at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Asociación Benéfica PRISMA in September 2005 and November 2005, respectively.

Data collection activities

Adolescent participants narrated their life histories (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber 1998). Two facilitators, the first author (a female) and a male research assistant, assisted the young females and males, respectively, in their narrations. At the start of the interview, adolescent narrators created a “life history map” and the direction of each interview followed the stages depicted on the map, providing narrators greater control over the direction of their stories. The facilitators’ contributions to the life story was based on a very open-ended guide that asked about individual identity, and significant events, people and activities during each life stage. Facilitators allowed space and time to see if the issues from the probes emerged from the participants themselves, in order to not bias the future direction of the interviews. This was particularly true of sexuality-related questions. If narrators mentioned this issue, the facilitators engaged them about their perspectives and experiences. If the issue did not emerge on its own, the facilitators asked brief questions if relevant, but waited to ask the main questions about sexuality at the end of the second interview. The sexuality-related questions engaged narrators about their personal definition of sexuality, their first thoughts about or memories of sexuality, and their sexuality-related discussions and experiences, including partners and behaviors.

A total of 40 interviews were carried out, two interviews with each of the 20 participants, during December 2005 and January 2006.

Data analysis

The interview data was initially analyzed using a holistic content analysis to draw major life themes and patterns (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber 1998). The interviews were then analyzed using a grounded-theory approach to identify categories and relationships, which were transformed into an initial set of codes (Glaser 1998; Strauss and Corbin 1998). Coding was carried out using the Atlas-ti software program (Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2005). The current analysis examines the presence of sexuality in the data. The authors broadly defined sexuality as events ranging from teasing members of the opposite sex and interest in peers and others as more than friends to having a partner or engaging in sexual behaviors.

Results

The authors considered sexuality in a broad sense: how one thinks, acts and feels as a sexual being and includes attraction, “bothering” members of the opposite sex (a common phenomena in the life history narratives), flirting, kissing, hugging, hand holding, petting, having sex, and having a partner. The authors sought out any participant quotes that entered into this broad definition. The participants, however, expressed changing perspectives on sexuality over the course of their interviews. Sometimes their mentions of sexuality did not equate sexuality with sexual intercourse (however, these were categorized as sexuality by the authors; when asked specifically, participants might not have categorized these stories as sexuality-related). Other times, participants’ mentions of sexuality did equate sexuality with sexual intercourse. The latter was more common for adolescent participants.

Presence of sexuality

Adolescent narrators mentioned the presence of sexuality in their lives as early as age five. Sexuality during childhood centered primarily around teasing members of the opposite sex and hearing about sexuality, by chance or from friends in the case of males and in the context of school in the case of females. Sexuality during early and middle adolescence included conversations about interest, attraction and sexual experiences with friends, siblings and relatives, usually but not always of the same sex, as well as sexuality-related experiences. These experiences range from playing games in mixed-sex environments and having a partner to the physical dimension of sexual experiences, including “play-acting” relationships and partner interactions. These experiences are described in detail in another manuscript (Bayer 2008).

Sexuality as a constrained choice

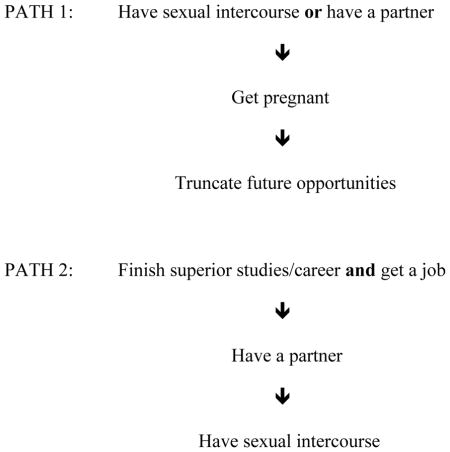

Despite the presence of sexuality in narrators’ lives starting in childhood and through the time when the interviews were conducted, a key dichotomy is present in many their stories: they view the complete expression of their sexuality as a constrained choice. Adolescents see only two possible life paths:a

While female narrators described this dichotomy in the context of their personal experiences and that of their peers, male narrators confirmed its existence solely based on their peers’ experiences. One 17 year old female narrator affirmed the dichotomy through messages from her parents. Her father discouraged her partner relationship because he thinks that studies should come first, while her mother always warned her about the negative consequences of unwanted pregnancy:

My dad talks about my boyfriend… ‘I don’t want to see him because I hate him’… Since he’s seen me in the house [with him], sitting like friends… he looks at him badly… In this sense, my dad doesn’t understand me… My dad doesn’t want [me to stay with my boyfriend]… because he says that studies come first.

My mom supports me… Well, she doesn’t support me… She tells me that it depends on me… She always advises me… that when I go out with him [my boyfriend] that I have to be careful… not get knocked up (meter la pata)… since later I would be the person who suffers…

Another 17 year old female narrator confirmed how this dichotomy disallows her from even spending time with a person she’s interested in:

Once I met a guy at a party… We danced and he started touching me… He wanted me to give him a kiss and I didn’t… because I didn’t know him well… I gave him my email… and we chatted by Internet several times… He told me he wanted to be with me… I told him no… that we could talk by Internet, but not meet in person… because I want to finish my studies.

This narrator preferred to finish her studies before getting involved in any type of relationship. Here, she further explained that she does have an interest in trying sexuality-related things and in relationships, but that she dissuades herself from thinking about the issue and pursues other things:

I have a friend who when someone declares his interest, she accepts… She says that it’s what young people do… that it’s not real… it’s only to try things out… sometimes I want to do the same things… but I think, better not to… I prefer to do other things, to not be thinking about those things.

Two other female narrators also felt that they should finish their studies before fully expressing their sexuality:

A guy declared his interest in me… We were together for a week, that’s it… I told him no… that I needed to finish my studies.

(14 year old female)

I don’t want a boyfriend… I think that I wouldn’t like to destroy my life… I’d like to finish high school and study something else before getting knocked up, as my friends say… then study nursing… and then think about that [having a partner]…

(15 year old female)

While the female narrators discussed their personal uncertainties about being involved in relationships due to fear of negative outcomes, both male and female narrators talked at length about their friends’ experiences with pregnancy and abortion:

Girls should wait until they turn 18 to get pregnant… because I’ve seen the case of a girl who hadn’t finished high school and got pregnant… Now she can’t study because she has to take care of her child… If she’d thought about things before acting… she should have finished her studies first and then thought about having a child…

(14 year old male)

I have a friend… He had a child with his girlfriend… He was 16, she was 15… They live together… Now he’s always working… to pay for the room, the baby… I never see him… He never has any fun… They’re going to have another baby… He’s 18…

(16 year old male)

My friend had a boyfriend and they’d been together for… four years I think… She had [sex] and got pregnant… She wanted [to have] the baby but she had an abortion because her dad made her have an abortion… She was crying and crying… It was since she was studying computer sciences… and the year that she got pregnant she was going to finish… When she got pregnant she wouldn’t have finished her career… She would have studied three years for no reason… so she had to have an abortion.

(17 year old female)

These anecdotes confirm the influence, both perceived and real, of an unintended pregnancy during adolescence.

Factors contributing to constrained sexuality

Multiple factors may contribute to the prevalence of the dichotomy of sexuality as a constrained choice in narrators’ lives: adolescents’ perception that sexual intercourse always results in pregnancy; the nature of the sex education that the narrators and other adolescents receive; the provision of proscriptive advice by adults to the narrators and other adolescents; and the broader context of adolescents’ lives. Most narrators perceive sexual intercourse, and in many cases even having a partner, as directly correlated to pregnancy. Although the use of protection could modify the sequence of having a partner, having sex, getting pregnant and truncating future opportunities, adolescents did not recognize this possibility. This lack of recognition exists even though the majority of narrators, and particularly older narrators, openly discussed learning about contraceptive methods, especially condoms. This may be due to the perception that contraceptive methods have high failure rates, as seen in one 14 year old female’s statement, which was repeated by others:

… there are many times when people use protection and it fails and the girl gets pregnant.

Another factor that may influence this dichotomy is the type of sex education that adolescents receive. Most narrators recalled learning about the physical, psychological and social changes during adolescence and the human reproductive system in the first three years of secondary school and sexually transmitted infections and contraceptive methods in the last two years. They did not report, however, learning about other dimensions of sexuality, such as healthy exploration and expression of their sexuality, both on their own and with a partner. As a few narrators recalled:

They started to teach [about sexuality] at school… because there were a lot of adolescent mothers… They talked about how to protect yourself, sexually transmitted diseases and all of that… They only talked about practical things.

(17 year old male)

My mom sometimes used to read a book… that said something about the man and the woman… She started saying, ‘the man has a penis, the woman has a vagina’… ‘Here are the eggs, sperm’… That’s what she would tell us…

(14 year old male)

A third factor is the proscriptive advice provided to adolescent narrators by teachers, parents and other adults. As the following quote shows, teachers confirm – or perhaps initiate – adolescents’ perceptions that sexual intercourse always results in pregnancy and can sometimes result in HIV and AIDS and that having sex could put future opportunities at risk and should therefore take place once a person has a stable job:

The teacher talked about… that we have to be careful with what we do… that we can get AIDS… that sex is for someone at his age, not at our age… when you have a stable job… You have to think about it 1,000 times before you do it… because sometimes you’re in a crisis, plus the kid you’re going to have… and you don’t have a job…

(15 year old male)

A final set of factors that contributes to adolescents’ perceptions of only two life paths in terms of expression of their sexuality is the broader context of adolescents’ lives. Factors such as family problems, poverty, race and violence at home, among peers and in the community represent the larger part of narrators’ life stories, as described in the quotes below and in much greater detail elsewhere (Bayer, Gilman et al. 2010).

Almost every conversation [with my mom] was about my dad and nothing else, ‘Your dad hasn’t come home, where could he be’… and we’d even go to look for him… Sometimes he wouldn’t be there and he’d come back 3 or 4 days later… [My parents] would fight… [about how] he didn’t bring her the check… My dad would hit her… He’d be hitting her. You could hear everything.

(17 year old male)

They insult me… and I don’t like them to insult me… It makes me feel, I don’t know… It makes me want to hit them… At school, I’ve grabbed them… I mean, I’ve fought with them… We’ve pulled each other’s hair… I don’t know. For no reason I just hit them…

(13 year old female)

One 16 year old female narrator clearly explained how her mother’s abandonment of her family affects her life:

I’ve taken greater responsibility for my siblings… I have to take care of them, bathe them, do everything for them… I can’t show them my sadness because they could catch it and feel bad… Sometimes I have to pretend that I’m happy so that they’ll be okay… Sometimes I cry all night… What hurts me most is that when my mom left, I was just starting my adolescence… I had the right to go out with my friends, to meet people… Now I don’t… A lot of girls my age have their boyfriends… but I don’t…

This narrator’s significant household responsibilities and traumatic family issues, as well as the perceived need to suppress her emotions, represent an immense burden for this adolescent and a hurdle to fully living her adolescence and her sexuality.

All of these factors contribute to the negative perception of sexuality expressed by a 12 year old female participant and other narrators, which affirms once again the constrained nature of sexuality according to adolescents in this setting.

Interviewer: Do you think there’s anything good about sexuality?

Participant: No!… You can get pregnant and you’re not even ready. You don’t even have a career and how are you going to raise your child? Think. He’ll suffer.

DISCUSSION

The life histories retold here confirm that sexuality is present in the adolescent narrators’ lives. Adolescents’ full, healthy expression of their sexuality, however, is limited by the high degree of constrained choice related to sexuality. Healthy sexuality refers to “a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence,” as defined by the World Health Organization. The amount of constraint surrounding adolescent sexuality in this setting often disallows adolescents from experiencing decisions that they make freely and perceive positively.

The presence of diverse contextual issues in the narrators’ lives starting in childhood and particularly in adolescence warrants revisiting. Quantitative studies in Peru have carried out regression analyses to determine whether researcher-selected contextual factors are positively correlated with different sexual behaviors (Chirinos, Salazar, and Brindis 2000; Magnani et al. 2001). A study about the correlates of sexual activity among secondary school students in urban Peru found that females with lower socioeconomic status were more likely to have had sexual intercourse and that females and males were more likely to have had sexual intercourse if they perceived that their friends had done so. Additionally, males whose friends had impregnated girls or whose female friends had had abortions were also more likely to have had sex (Magnani et al. 2001). A second study about the correlates of sexual activity among male secondary school students in Lima found that males living in a single-parent or mixed-family household were more likely to be sexually active (Chirinos, Salazar, and Brindis 2000).

The adolescent narrators in this study described how the factors found to be significant in these quantitative studies often work in the opposite direction in their lives. They perceive that if they decide to express their sexuality by either having a partner or having sexual intercourse, they inevitably truncate future opportunities due to unwanted pregnancy. This perception was repeated by most of the female adolescents, who are all of lower socioeconomic status, as a significant factor in their individual decisions to not have sexual intercourse and, in many cases, to not have a partner. Although this population was not compared to females of higher socioeconomic status, the degree to which this perception dominated females’ life stories suggests the need for further exploration of the relationship between socioeconomics and sexual activity. Both male and female adolescents defended this limited life path, in most cases based on their peers’ sexual experiences, again suggesting the need to further analyze the impact of perceived peer behaviors.

The majority of narrators also discussed the instability of their household structures throughout their lives. Economic struggles and disagreements and infidelities between parents contribute to oscillating family arrangements, where one parent (usually the father) may be absent for shorter or longer periods of time, making household structure very difficult to categorize in this setting. Additionally, the narrators described how family instability contributes to their personal instability and often disallows them from exploring their adolescence and expressing their sexuality. This suggests the importance of analyzing in greater depth the relationship between family structure and having sexual intercourse.

Adolescents’ detailed narratives confirm that adolescents’ lives are incredibly complex. Factors cannot be examined in isolation and need to be considered in terms of how they interact with other influential factors. Socioeconomic status and household structure may interact with family, peer and community connectedness, which occupied a large space in adolescents’ broader life histories, to influence adolescent sexuality. For example, one of the quantitative studies found that family connectedness, and specifically, being important to those with whom they lived, was associated with a lower likelihood of having sexual intercourse (Magnani et al. 2001). Similarly, perceived peer sexual activity may be mediated by individual characteristics such as self-esteem and self-efficacy, which participants also mentioned in their narrations. The findings from the current study confirm the need to examine how diverse factors interact to influence adolescents (Sebastiani and Segil 1999). A final, and equally important, consideration is that of gender. Past studies in many settings, including Peru, have focused on either males or females or have made significant differentiations between the two. Gender differences were present in the life history narratives. Overall, however, males and females shared commonalities in their life and sexuality experiences. Specifically, the narrators’ constrained choices in terms of healthy exploration and expression of their sexuality was true for both females and males. This may be due to structural influences, and specifically the fact that both females and males in this setting face numerous challenges throughout their lives and particularly during adolescence. The vulnerabilities confronted specifically by males that identify as heterosexual have not been addressed in previous studies in Peru (Arias and Aramburú 1999; Cáceres 1999; Quintana 2002; Saravia et al. 1999; Yon Leau 1998) and warrant further exploration.

Limitations

The study may be subject to selectivity bias, since adolescents who agreed to participate or parents/guardians who allowed their children to participate may be different from those who did not agree. Social desirability bias is also a concern, since adolescents may provide responses that they think might please the interviewer or that reflect acceptable social norms. In the current context, social norms may be gender-related and influence females to base their answers on societal norms that restrict female sexual activity and males to over-report behaviors to demonstrate that they are meeting society’s expectations for males to have sexual experience (Gregson et al. 2002). The research team implemented various measures to minimize this concern and increase the level of honesty in narrators’ stories: one-on-one interviews with a facilitator of the same sex; a two interview structure in order to improve rapport, with specific questions about sexuality only at the end of the second interview; participant selection of the interview location in order to ensure their comfort; and participant determination of the direction and most of the content of the interview through the creation of the life history map. A third limitation of the current study is that of recall bias, when participants are unable to accurately recall memories. A final limitation relates to the difficulty of presenting an accurate representation of the rich information that adolescents provided about this sensitive and intimate dimension of their lives. The authors attempted to synthesize and summarize in a manner that represents these adolescents’ voices and perspectives on the role of sexuality in their lives.

Conclusions

For the adolescent narrators, social and cultural factors such as gender, race, poverty and violence, seem to not only interact with biology to influence adolescent sexuality, but to collide, surpass and often suppress the physical and psychological dimensions of these young people’s lives. Further mixed methods research, including participatory qualitative studies and cross-sectional and longitudinal quantitative studies, needs to analyze how the numerous and diverse social and cultural factors present in adolescents’ lives interact in order to influence adolescent sexuality. Results of this study will also be helpful for informing policies and programs that aim to support adolescents as they construct a positive sexuality and strive to make informed sexuality-related decisions. Examples of programs include sex education and youth friendly health services, which should provide accurate, youth-appropriate information and services while effectively debunking common myths and empowering young people. It is clear that these programs need to integrate strategies to address the complexities of adolescents’ families, peers and communities, as well as their educational and work-related opportunities, in order to have a true positive impact on their sexuality.

Acknowledgments

Angela Bayer is currently a postdoctoral scholar with Thomas J. Coates, NIH NIMH grant T32MH080634-03. The authors would like to thank Danilo Climaco, PRISMA field staff (especially Lilia Cabrera and Flor Pizarro) and Bob Gilman for their support and assistance. Special thanks to the young people who so generously shared their life experiences in this study.

Footnotes

This study is the first phase of a larger study on adolescent sexuality. This dichotomy was further explored with 63 15-17 year olds from the same study community who participated in focus groups. This larger group of adolescents confirmed the existence of this dichotomy for both male and female adolescents from their community, as described in greater detail elsewhere (Bayer, Cabrera et al.).

References

- Arias R, Aramburú CE. Uno Empieza a Alucinar … Percepciones de los jóvenes sobre sexualidad, embarazo y acceso a los servicios de salud: Lima, Cusco e Iquitos. Lima, Perú: Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer AM, Cabrera LZ, Gilman RH, Hindin MJ, Tsui AO. Adolescents can know best: Using concept mapping to identify factors and pathways driving adolescent sexuality in Lima, Peru. Soc Sci Med. 2010 Jun;70(12):2085–95. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.001. Epub 2010 Mar 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer AM, Gilman RH, Tsui AO, Hindin MJ. What is adolescence?: Adolescents narrate their lives in Lima, Peru. J Adolesc. 2010 Aug;33(4):509–20. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.02.002. Epub 2010 Mar 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer AM. The Context, Factors and Pathways related to Adolescent Sexuality in Lima, Peru. Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health; Baltimore, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc AK, Way AA. Sexual behavior and contraceptive knowledge and use among adolescents in developing countries. Stud Fam Plann. 1998;29(2):106–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres CF. La (Re)Configuración del Universo Sexual. Lima, Perú: Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chirinos JL, V, Salazar C, Brindis CD. A profile of sexually active male adolescent high school students in Lima, Peru. Caderno de Saude Publica. 2000;16(3):733–46. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2000000300022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García PJ, Cotrina A, Cárcamo CP. Sexo, Prevención y Riesgo. Adolescentes y sus madres frente al VIH y las ITS en el Perú. Perú: CARE Perú; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Zhuwau T, Ndlovu J, Nyamukapa CA. Methods to reduce social desirability bias in sex surveys in low-development settings: experience in Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(10):568–75. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Perú en Cifras. Lima, Perú: INEI; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich A, Tuval-Mashiach R, Zilber T. Narrative Research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Applied Social Research Methods Series. Vol. 47. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CB, Behrman JR, Stromquist NP, Cohen B, editors. Growing Up Global: The changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Magnani RJ, Seiber EE, Gutierrez EZ, Vereau D. Correlates of sexual activity and condom use among secondary-school students in urban Peru. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32(1):53–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud. Perfil de la Población. Lima, Perú: MINSA - Oficina General de Estadística e Informática; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Municipalidad de San Juan de Miraflores. Plan de Desarrollo Integral de San Juan de Miraflores 2003–2012. Lima, Perú: Muni SJM - Equipo Técnico PDI; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana AS. Itinerarios de salud sexual y reproductiva de los y las adolescentes y jóvenes de dos distritos de Lima. In: Cáceres CF, editor. La Salud Sexual Como Derecho en el Perú de Hoy: Ocho estudios sobre salud, género y derechos sexuales entre los jóvenes y otros grupos vulnerables. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana AS, Hidalgo C, Dourojeanni D. Escuchen Nuestras Voces… Representaciones sociales e itinerarios de salud sexual y reproductiva de adolescentes y jóvenes. Lima, Perú: Instituto de Educación y Salud; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Lewis J, Elam G. Designing and selecting samples. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative Research Practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Saravia C, Apolinario H, Morales R, Reynoso B, Salinas V. Itinerario del acceso al condón en adolescentes de Lima, Cusco e Iquitos. In: Cáceres CF, editor. Nuevos Retos: Investigaciones recientes sobre salud sexual y reproductiva de los jóvenes en el Perú. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani A, Segil E. Qué hacen, qué piensan, qué sienten los y las adolescentes respecto a la salud sexual y reproductiva. In: Cáceres CF, editor. Nuevos Retos: Investigaciones recientes sobre salud sexual y reproductiva de los jóvenes en el Perú. Lima, Perú: REDESS Jóvenes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, Diamond LM. Desegregating sexuality research: cultural and biological perspectives on gender and desire. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2001;12:33–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yon Leau C. Género y Sexualidad. Una mirada de los y las adolescentes en cinco barrios de la ciudad de Lima. Lima, Perú: Movimiento Manuela Ramos; 1998. [Google Scholar]